Chord (music)

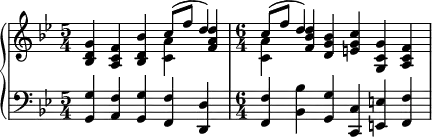

A chord, in music, is any harmonic set of pitches/frequencies consisting of multiple notes (also called "pitches") that are heard as if sounding simultaneously.[lower-alpha 1] For many practical and theoretical purposes, arpeggios and broken chords (in which the notes of the chord are sounded one after the other, rather than simultaneously), or sequences of chord tones, may also be considered as chords in the right musical context.

In tonal Western classical music (music with a tonic key or "home key"), the most frequently encountered chords are triads, so called because they consist of three distinct notes: the root note, and intervals of a third and a fifth above the root note. Chords with more than three notes include added tone chords, extended chords and tone clusters, which are used in contemporary classical music, jazz and almost any other genre.

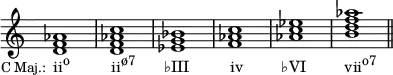

A series of chords is called a chord progression.[1] One example of a widely used chord progression in Western traditional music and blues is the 12 bar blues progression. Although any chord may in principle be followed by any other chord, certain patterns of chords are more common in Western music, and some patterns have been accepted as establishing the key (tonic note) in common-practice harmony—notably the resolution of a dominant chord to a tonic chord. To describe this, Western music theory has developed the practice of numbering chords using Roman numerals[2] to represent the number of diatonic steps up from the tonic note of the scale.

Common ways of notating or representing chords[3] in Western music (other than conventional staff notation) include Roman numerals, the Nashville Number System, figured bass, chord letters (sometimes used in modern musicology), and chord charts.

Definition

The English word chord derives from Middle English cord, a back-formation of accord[4] in the original sense of agreement and later, harmonious sound.[5] A sequence of chords is known as a chord progression or harmonic progression. These are frequently used in Western music.[6] A chord progression "aims for a definite goal" of establishing (or contradicting) a tonality founded on a key, root or tonic chord.[2] The study of harmony involves chords and chord progressions and the principles of connection that govern them.[7]

Ottó Károlyi[9] writes that, "Two or more notes sounded simultaneously are known as a chord," though, since instances of any given note in different octaves may be taken as the same note, it is more precise for the purposes of analysis to speak of distinct pitch classes. Furthermore, as three notes are needed to define any common chord, three is often taken as the minimum number of notes that form a definite chord.[10] Hence, Andrew Surmani, for example, states, "When three or more notes are sounded together, the combination is called a chord."[11] George T. Jones agrees: "Two tones sounding together are usually termed an interval, while three or more tones are called a chord."[12] According to Monath, "a chord is a combination of three or more tones sounded simultaneously", and the distances between the tones are called intervals.[13] However, sonorities of two pitches, or even single-note melodies, are commonly heard as implying chords.[14] A simple example of two notes being interpreted as a chord is when the root and third are played but the fifth is omitted. In the key of C major, if the music stops on the two notes G and B, most listeners hear this as a G major chord.

Since a chord may be understood as such even when all its notes are not simultaneously audible, there has been some academic discussion regarding the point at which a group of notes may be called a chord. Jean-Jacques Nattiez explains that, "We can encounter 'pure chords' in a musical work", such as in the "Promenade" of Modest Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition but, "often, we must go from a textual given to a more abstract representation of the chords being used", as in Claude Debussy's Première arabesque.[8]

History

In the medieval era, early Christian hymns featured organum (which used the simultaneous perfect intervals of a fourth, a fifth, and an octave[15]), with chord progressions and harmony - an incidental result of the emphasis on melodic lines during the medieval and then Renaissance (15th to 17th centuries).[16][17]

The Baroque period, the 17th and 18th centuries, began to feature the major and minor scale based tonal system and harmony, including chord progressions and circle progressions.[3] It was in the Baroque period that the accompaniment of melodies with chords was developed, as in figured bass,[17] and the familiar cadences (perfect authentic, etc.).[18] In the Renaissance, certain dissonant sonorities that suggest the dominant seventh occurred with frequency.[19] In the Baroque period, the dominant seventh proper was introduced and was in constant use in the Classical and Romantic periods.[19] The leading-tone seventh appeared in the Baroque period and remains in use.[20] Composers began to use nondominant seventh chords in the Baroque period. They became frequent in the Classical period, gave way to altered dominants in the Romantic period, and underwent a resurgence in the Post-Romantic and Impressionistic period.[21]

The Romantic period, the 19th century, featured increased chromaticism.[3] Composers began to use secondary dominants in the Baroque, and they became common in the Romantic period.[22] Many contemporary popular Western genres continue to rely on simple diatonic harmony, though far from universally:[23] notable exceptions include the music of film scores, which often use chromatic, atonal or post-tonal harmony, and modern jazz (especially circa 1960), in which chords may include up to seven notes (and occasionally more).[24] When referring to chords that do not function as harmony, such as in atonal music, the term "sonority" is often used specifically to avoid any tonal implications of the word "chord".

Chords are also used for timbre effects. In organ registers, certain chords are activated by a single key so that playing a melody results in parallel voice leading. These voices, losing independence, are fused into one with a new timbre. The same effect is also used in synthesizers and orchestral arrangements; for instance, in Ravel’s Bolero #5 the parallel parts of flutes, horn and celesta, being tuned as a chord, resemble the sound of an electric organ.[25][26]

Notation

Chords can be represented in various ways. The most common notation systems are:[3]

- Plain staff notation, used in classical music

- Roman numerals, commonly used in harmonic analysis to denote the scale step on which the chord is built.[2]

- Figured bass, much used in the Baroque era, uses numbers added to a bass line written on a staff, to enable keyboard players to improvise chords with the right hand while playing the bass with their left.

- Chord letters, sometimes used in modern musicology, to denote chord root and quality.

- Various chord names and symbols used in popular music lead sheets, fake books, and chord charts, to quickly lay out the harmonic ground plan of a piece so that the musician may improvise, jam, or vamp on it.

Roman numerals

While scale degrees are typically represented in musical analysis or musicology articles with Arabic numerals (e.g., 1, 2, 3, ..., sometimes with a circumflex above the numeral: ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , ...), the triads (three-note chords) that have these degrees as their roots are often identified by Roman numerals (e.g., I, IV, V, which in the key of C major would be the triads C major, F major, G major).

, ...), the triads (three-note chords) that have these degrees as their roots are often identified by Roman numerals (e.g., I, IV, V, which in the key of C major would be the triads C major, F major, G major).

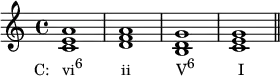

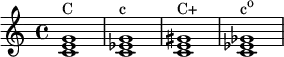

In some conventions (as in this and related articles) upper-case Roman numerals indicate major triads (e.g., I, IV, V) while lower-case Roman numerals indicate minor triads (e.g., I for a major chord and i for a minor chord, or using the major key, ii, iii and vi representing typical diatonic minor triads); other writers (e.g., Schoenberg) use upper case Roman numerals for both major and minor triads. Some writers use upper-case Roman numerals to indicate the chord is diatonic in the major scale, and lower-case Roman numerals to indicate that the chord is diatonic in the minor scale. Diminished triads may be represented by lower-case Roman numerals with a degree symbol (e.g., viio7 indicates a diminished seventh chord built on the seventh scale degree; in the key of C major, this chord would be B diminished seventh, which consists of the notes B, D, F and A♭).

Roman numerals can also be used in stringed instrument notation to indicate the position or string to play. In some string music, the string on which it is suggested that the performer play the note is indicated with a Roman numeral (e.g., on a four-string orchestral string instrument, I indicates the highest-pitched, thinnest string and IV indicates the lowest-pitched, thickest bass string). In some orchestral parts, chamber music and solo works for string instruments, the composer tells the performer which string to use with the Roman numeral. Alternately, the composer starts the note name with the sting to use—e.g., "sul G" means "play on the G string".

Figured bass notation

| Triads | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Inversion | Intervals above bass |

Symbol | Example |

| Root position | 5 3 |

None |  |

| 1st inversion | 6 3 |

6 | |

| 2nd inversion | 6 4 |

6 4 | |

| Seventh chords | |||

| Inversion | Intervals above bass |

Symbol | Example |

| Root position | 7 |  | |

| 1st inversion | 6 5 | ||

| 2nd inversion | 4 3 | ||

| 3rd inversion | 4 2 or 2 | ||

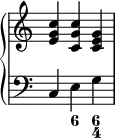

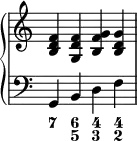

Figured bass or thoroughbass is a kind of musical notation used in almost all Baroque music (c. 1600–1750), though rarely in music from later than 1750, to indicate harmonies in relation to a conventionally written bass line. Figured bass is closely associated with chord-playing basso continuo accompaniment instruments, which include harpsichord, pipe organ and lute. Added numbers, symbols, and accidentals beneath the staff indicate the intervals above the bass note to play; that is, the numbers stand for the number of scale steps above the written note to play the figured notes.

For example, in the figured bass below, the bass note is a C, and the numbers 4 and 6 indicate that notes a fourth and a sixth above (F and A) should be played, giving the second inversion of the F major triad.

If no numbers are written beneath a bass note, the figure is assumed to be 5

3, which calls for a third and a fifth above the bass note (i.e., a root position triad).

In the 2010s, some classical musicians who specialize in music from the Baroque era can still perform chords using figured bass notation; in many cases, however, the chord-playing performers read a fully notated accompaniment that has been prepared for the piece by the music publisher. Such a part, with fully written-out chords, is called a "realization" of the figured bass part.

Chord letters

Chord letters are used by musicologists, music theorists and advanced university music students to analyze songs and pieces. Chord letters use upper-case and lower-case letters to indicate the roots of chords, followed by symbols that specify the chord quality.[28]

Notation in popular music

In most genres of popular music, including jazz, pop, and rock, a chord name and the corresponding symbol are typically composed of one or more parts. In these genres, chord-playing musicians in the rhythm section (e.g., electric guitar, acoustic guitar, piano, Hammond organ, etc.) typically improvise the specific "voicing" of each chord from a song's chord progression by interpreting the written chord symbols appearing in the lead sheet or fake book. Normally, these chord symbols include:

- A (big) letter indicating the root note (e.g., C).

- A symbol or abbreviation indicating the chord quality (e.g., minor, aug or o ). If no chord quality is specified, the chord is assumed to be a major triad by default.

- Number(s) indicating the stacked intervals above the root note (e.g., 7 or 13).

- Additional musical symbols or abbreviations for special alterations (e.g., ♭5, ♯5 or add13).

- An added slash "/" and an upper case letter indicates that a bass note other than the root should be played. These are called slash chords. For instance, C/F indicates that a C major triad should be played with an added F in the bass. In some genres of modern jazz, two chords with a slash between them may indicate an advanced chord type called a polychord, which is the playing of two chords simultaneously. The correct notation of this should be F/C, which sometimes get mixed up with slash chords.

Chord qualities are related with the qualities of the component intervals that define the chord. The main chord qualities are:

- Major and minor (a chord is "Major" by default and altered with added info: "C" = C major, "Cm" = c minor).

- augmented, diminished, and half-diminished,

- dominant seventh.

Symbols

The symbols used for notating chords are:

- m, min, or − indicates a minor chord. The "m" must be lowercase to distinguish it from the "M" for major.

- M, Ma, Maj, Δ, or (no symbol) indicates a major chord. In a jazz context, this typically indicates that the player should use any suitable chord of a major quality, for example a major seventh chord or a 6/9 chord. In a lot of jazz styles, an unembellished major triad is rarely if ever played, but in a lead sheet the choice of which major quality chord to use is left to the performer.

- + or aug indicates an augmented chord (A or a is not used).

- o or dim indicates a diminished chord, either a diminished triad or a diminished seventh chord (d is not used).

- ø indicates a half-diminished seventh chord. In some fake books, the abbreviation m7(♭5) is used as an equivalent symbol.

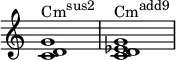

- 2 is mostly used as an extra note in a chord (e.g., add2, sus2).

- 3 is the minor or major quality of the chord and is rarely written as a number.

- 4 is mostly used as an extra note in a chord (e.g., add4, sus4).

- 5 is the (perfect) fifth of the chord and is only written as a number when altered (e.g., F7(♭5)). In guitar music, like rock, a "5" indicates a power chord, which consists of only the root and fifth, possibly with the root doubled an octave higher.

- 6 indicates a sixth chord. There are no rules if the 6 replaces the 5th or not.

- 7 indicates a dominant seventh chord. However, if Maj7, M7 or Δ7 is indicated, this is a major 7th chord (e.g., GM7 or FΔ7). Very rarely, also dom is used for dominant 7th.

- 9 indicates a ninth chord, which in jazz usually includes the dominant seventh as well, if it is a dominant chord.

- 11 indicates an eleventh chord, which in jazz usually includes the dominant seventh and ninth as well, if it is a dominant chord.

- 13 indicates a thirteenth chord, which in jazz usually includes the dominant seventh, ninth and eleventh as well.

- 6/9 indicates a triad with the addition of the sixth and ninth.

- sus4 (or simply 4) indicates a sus chord with the third omitted and the fourth used instead. Other notes may be added to a sus4 chord, indicated with the word "add" and the scale degree (e.g., Asus4(add9) or Asus4(add7)).

- sus2 (or simply 2) indicates a sus chord with the third omitted and the second (which may also be called the ninth) used instead. As with "sus4", a "sus2" chord can have other scale degrees added (e.g., Asus2(add♭7) or Asus2(add4)).

- (♭9) (parenthesis) is used to indicate explicit chord alterations (e.g., A7(♭9)). The parenthesis is probably left from older days when jazz musicians weren't used to "altered chords". Albeit important, the parenthesis can be left unplayed (with no "musical harm").

- add indicates that an additional interval number should be added to the chord. (e.g., C7add13 is a C 7th chord plus an added 13th).

- alt or alt dom indicates an altered dominant seventh chord (e.g., G7♯11).

- omit5 (or simply no5) indicates that the (indicated) note should be omitted.

Examples

The table below lists common chord types, their symbols, and their components.

Chord Components Name Symbol (on C) Interval P1 m2 M2 m3 M3 P4 d5 P5 A5 M6/d7 m7 M7 Short Long Semitones 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Major triad C

CΔP1 M3 P5 Major sixth chord C6

CM6Cmaj6 P1 M3 P5 M6 Dominant seventh chord C7 Cdom7 P1 M3 P5 m7 Major seventh chord CM7

C∆7Cmaj7 P1 M3 P5 M7 Augmented triad C+ Caug P1 M3 A5 Augmented seventh chord C+7 Caug7 P1 M3 A5 m7 Minor triad Cm Cmin P1 m3 P5 Minor sixth chord Cm6 Cmin6 P1 m3 P5 M6 Minor seventh chord Cm7 Cmin7 P1 m3 P5 m7 Minor-major seventh chord CmM7

Cm/M7

Cm(M7)Cminmaj7

Cmin/maj7

Cmin(maj7)P1 m3 P5 M7 Diminished triad Co Cdim P1 m3 d5 Diminished seventh chord Co7 Cdim7 P1 m3 d5 d7 Half-diminished seventh chord Cø

Cø7P1 m3 d5 m7

Use

The basic function of chord symbols is to eliminate the need to write out sheet music. The modern jazz player has extensive knowledge of the chordal functions and can mostly play music by reading the chord symbols only. Advanced chords are common especially in modern jazz. Altered 9ths, 11ths and 5ths are not common in pop music. In jazz, a chord chart is used by comping musicians (jazz guitar, jazz piano, Hammond organ) to improvise a chordal accompaniment and to play improvised solos. Jazz bass players improvise a bassline from a chord chart. Chord charts are used by horn players and other solo instruments to guide their solo improvisations.

Interpretation of chord symbols depends on the genre of music being played. In jazz from the bebop era or later, major and minor chords are typically realized as seventh chords even if only "C" or "Cm" appear in the chart. In jazz charts, seventh chords are often realized with upper extensions, such as the ninth, sharp eleventh, and thirteenth, even if the chart only indicates "A7". In jazz, the root and fifth are often omitted from chord voicings, except when there is a diminished fifth or an augmented fifth.

In a pop or rock context, however, "C" and "Cm" would almost always be played as triads, with no sevenths. In pop and rock, in the relatively less common cases where songwriters wish a dominant seventh, major seventh, or minor seventh chord, they indicate this explicitly with the indications "C7", "Cmaj7" or "Cm7".

Characteristics

Within the diatonic scale, every chord has certain characteristics, which include:

- the number of pitch classes (distinct notes without respect to octave) in the chord,

- the scale degree of the root note,

- the position or inversion of the chord,

- the general type of intervals it is constructed from—for example, seconds, thirds, or fourths, and

- counts of each pitch class as occur between all combinations of notes the chord contains.

Number of notes

| No. | Name | Alternate name |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Monad | Monochord |

| 2 | Dyad | Dichord |

| 3 | Triad | Trichord |

| 4 | Tetrad | Tetrachord |

| 5 | Pentad | Pentachord |

| 6 | Hexad | Hexachord |

| 7 | Heptad | Heptachord |

| 8 | Octad | Octachord |

| 9 | Ennead | Nonachord |

| 10 | Decad | Decachord |

Two-note combinations, whether referred to as chords or intervals, are called dyads. In the context of a specific section in a piece of music, dyads can be heard as chords if they contain the most important notes of a certain chord. For example, in a piece in C Major, after a section of tonic C Major chords, a dyad containing the notes B and D sounds to most listeners as a first inversion G Major chord. Other dyads are more ambiguous, an aspect that composers can use creatively. For example, a dyad with a perfect fifth has no third, so it does not sound major or minor; a composer who ends a section on a perfect fifth could subsequently add the missing third. Another example is a dyad outlining the tritone, such as the notes C and F# in C Major. This dyad could be heard as implying a D7 chord (resolving to G Major) or as implying a C diminished chord (resolving to Db Major). In unaccompanied duos for two instruments, such as flute duos, the only combinations of notes that are possible are dyads, which means that all of the chord progressions must be implied through dyads, as well as with arpeggios.

Chords constructed of three notes of some underlying scale are described as triads. Chords of four notes are known as tetrads, those containing five are called pentads and those using six are hexads. Sometimes the terms trichord, tetrachord, pentachord, and hexachord are used—though these more usually refer to the pitch classes of any scale, not generally played simultaneously. Chords that may contain more than three notes include pedal point chords, dominant seventh chords, extended chords, added tone chords, clusters, and polychords.

Polychords are formed by two or more chords superimposed.[29] Often these may be analysed as extended chords; examples include tertian, altered chord, secundal chord, quartal and quintal harmony and Tristan chord. Another example is when G7(♯11♭9) (G–B–D–F–A♭–C♯) is formed from G major (G–B–D) and D♭ major (D♭–F–A♭).[30] A nonchord tone is a dissonant or unstable tone that lies outside the chord currently heard, though often resolving to a chord tone.[31]

Scale degree

| Roman Numeral |

Scale Degree |

|---|---|

| I | tonic |

| ii | supertonic |

| iii | mediant |

| IV | subdominant |

| V | dominant |

| vi | submediant |

| viio / ♭VII | leading tone / subtonic |

In the key of C major, the first degree of the scale, called the tonic, is the note C itself. A C major chord, the major triad built on the note C (C–E–G), is referred to as the one chord of that key and notated in Roman numerals as I. The same C major chord can be found in other scales: it forms chord III in the key of A minor (A→B→C) and chord IV in the key of G major (G→A→B→C). This numbering indicates the chords's function.

Many analysts use lower-case Roman numerals to indicate minor triads and upper-case numerals for major triads, and degree and plus signs ( o and + ) to indicate diminished and augmented triads respectively. Otherwise, all the numerals may be upper-case and the qualities of the chords inferred from the scale degree. Chords outside the scale can be indicated by placing a flat/sharp sign before the chord—for example, the chord E♭ major in the key of C major is represented by ♭III. The tonic of the scale may be indicated to the left (e.g., "F♯:") or may be understood from a key signature or other contextual clues. Indications of inversions or added tones may be omitted if they are not relevant to the analysis. Roman numeral analysis indicates the root of the chord as a scale degree within a particular major key as follows.

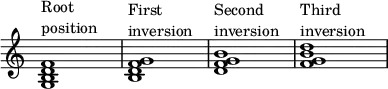

Inversion

In the harmony of Western art music, a chord is in root position when the tonic note is the lowest in the chord (the bass note), and the other notes are above it. When the lowest note is not the tonic, the chord is inverted. Chords that have many constituent notes can have many different inverted positions as shown below for the C major chord:

Bass note Position Order of notes

(starting from the bass)Notation C root position C–E–G or C–G–E 5

3 as G is a fifth above C and E is a third above CE first inversion E–G–C or E–C–G 6

3 as C is a sixth above E and G is a third above EG second inversion G–C–E or G–E–C 6

4 as E is a sixth above G and C is a fourth above G

Further, a four-note chord can be inverted to four different positions by the same method as triadic inversion. For example, a G7 chord can be in root position (G as bass note); first inversion (B as bass note); second inversion (D as bass note); or third inversion (F as bass note).

Where guitar chords are concerned, the term "inversion" is used slightly differently; to refer to stock fingering "shapes".[32]

Secundal, tertian, and quartal chords

| Type | Component intervals |

|---|---|

| Secundal | Seconds: major second, minor second |

| Tertian | Thirds: major third, minor third |

| Quartal | Fourth: perfect fourth, augmented fourth |

| Quintal | Fifths: diminished fifth, perfect fifth |

Many chords are a sequence of notes separated by intervals of roughly the same size. Chords can be classified into different categories by this size:

- Tertian chords can be decomposed into a series of (major or minor) thirds. For example, the C major triad (C–E–G) is defined by a sequence of two intervals, the first (C–E) being a major third and the second (E–G) being a minor third. Most common chords are tertian.

- Secundal chords can be decomposed into a series of (major or minor) seconds. For example, the chord C–D–E♭ is a series of seconds, containing a major second (C–D) and a minor second (D–E♭).

- Quartal chords can be decomposed into a series of (perfect or augmented) fourths. Quartal harmony normally works with a combination of perfect and augmented fourths. Diminished fourths are enharmonically equivalent to major thirds, so they are uncommon.[33] For example, the chord C–F–B is a series of fourths, containing a perfect fourth (C–F) and an augmented fourth/tritone (F–B).

These terms can become ambiguous when dealing with non-diatonic scales, such as the pentatonic or chromatic scales. The use of accidentals can also complicate the terminology. For example, the chord B♯–E–A♭ appears to be quartal, as a series of diminished fourths (B♯–E and E–A♭), but it is enharmonically equivalent to (and sonically indistinguishable from) the tertian chord C–E–G♯, which is a series of major thirds (C–E and E–G♯).

Harmonic content

The notes of a chord form intervals with each of the other notes of the chord in combination. A 3-note chord has 3 of these harmonic intervals, a 4-note chord has 6, a 5-note chord has 10, a 6-note chord has 15.[34] The absence, presence, and placement of certain key intervals plays a large part in the sound of the chord, and sometimes of the selection of the chord that follows.

A chord containing tritones is called tritonic; one without tritones is atritonic. Harmonic tritones are an important part of dominant seventh chords, giving their sound a characteristic tension, and making the tritone interval likely to move in certain stereotypical ways to the following chord.[35] Tritones are also present in diminished seventh and half-diminished chords.

A chord containing semitones, whether appearing as minor seconds or major sevenths, is called hemitonic; one without semitones is anhemitonic. Harmonic semitones are an important part of major seventh chords, giving their sound a characteristic high tension, and making the harmonic semitone likely to move in certain stereotypical ways to the following chord.[36] A chord containing major sevenths but no minor seconds is much less harsh in sound than one containing minor seconds as well.

Other chords of interest might include the

- Diminished triad, which has many minor thirds and no major thirds, many tritones but no perfect fifths

- Augmented triad, which has many major thirds and no minor thirds or perfect fifths

- Dominant seventh flat five chord, which has many major thirds and tritones and no minor thirds or perfect fifths

Common types of chords

Triads

Triads, also called triadic chords, are tertian chords with three notes. The four basic triads are described below.

Seventh chords

Seventh chords are tertian chords, constructed by adding a fourth note to a triad, at the interval of a third above the fifth of the chord. This creates the interval of a seventh above the root of the chord, the next natural step in composing tertian chords. The seventh chord built on the fifth step of the scale (the dominant seventh) is the only dominant seventh chord available in the major scale: it contains all three notes of the diminished triad of the seventh and is frequently used as a stronger substitute for it.

There are various types of seventh chords depending on the quality of both the chord and the seventh added. In chord notation the chord type is sometimes superscripted and sometimes not (e.g., Dm7, Dm7, and Dm7 are all identical).

Type Component intervals Chord symbol Notes Audio Third Fifth Seventh Diminished seventh minor diminished diminished Co7, Cdim7 C E♭ G♭ B

Play

Play Half-diminished seventh minor diminished minor Cø7, Cm7♭5, C−(♭5) C E♭ G♭ B♭  Play

Play Minor seventh minor perfect minor Cm7, Cmin7, C−7, C E♭ G B♭  Play

Play Minor major seventh minor perfect major CmM7, Cmmaj7, C−(j7), C−Δ7, C−M7 C E♭ G B  Play

Play Dominant seventh major perfect minor C7, Cdom7 C E G B♭  Play

Play Major seventh major perfect major CM7, CM7, Cmaj7, CΔ7, Cj7 C E G B  Play

Play Augmented seventh major augmented minor C+7, Caug7, C7+, C7+5, C7♯5 C E G♯ B♭  Play

Play Augmented major seventh major augmented major C+M7, CM7+5, CM7♯5, C+j7, C+Δ7 C E G♯ B  Play

Play

Extended chords

Extended chords are triads with further tertian notes added beyond the seventh: the ninth, eleventh, and thirteenth chords. For example, a dominant thirteenth chord consists of the notes C–E–G–B♭–D–F–A:

The upper structure or extensions, i.e., notes beyond the seventh, are shown in red. This chord is just a theoretical illustration of this chord. In practice, a jazz pianist or jazz guitarist would not normally play the chord all in thirds as illustrated. Jazz voicings typically use the third, seventh, and then the extensions such as the ninth and thirteenth, and in some cases the eleventh. The root is often omitted from chord voicings, as the bass player will play the root. The fifth is often omitted if it is a perfect fifth. Augmented and diminished fifths are normally included in voicings. After the thirteenth, any notes added in thirds duplicate notes elsewhere in the chord; all seven notes of the scale are present in the chord, so adding more notes does not add new pitch classes. Such chords may be constructed only by using notes that lie outside the diatonic seven-note scale.

Type Components Chord

symbolNotes Audio Chord Extensions Dominant ninth dominant seventh major ninth — — C9 C E G B♭ D  Play

Play Dominant eleventh dominant seventh

(the third is usually omitted)major ninth perfect eleventh — C11 C E G B♭ D F  Play

Play Dominant thirteenth dominant seventh major ninth perfect eleventh

(usually omitted)major thirteenth C13 C E G B♭ D F A  Play

Play

Other extended chords follow similar rules, so that for example maj9, maj11, and maj13 contain major seventh chords rather than dominant seventh chords, while m9, m11, and m13 contain minor seventh chords.

Altered chords

The third and seventh of the chord are always determined by the symbols shown above. The root cannot be so altered without changing the name of the chord, while the third cannot be altered without altering the chord's quality. Nevertheless, the fifth, ninth, eleventh and thirteenth may all be chromatically altered by accidentals.

These are noted alongside the altered element. Accidentals are most often used with dominant seventh chords. Altered dominant seventh chords (C7alt) may have a minor ninth, a sharp ninth, a diminished fifth, or an augmented fifth. Some write this as C7+9, which assumes also the minor ninth, diminished fifth and augmented fifth. The augmented ninth is often referred to in blues and jazz as a blue note, being enharmonically equivalent to the minor third or tenth. When superscripted numerals are used the different numbers may be listed horizontally or vertically.

Type Components Chord symbol Notes Audio Chord Alteration Seventh augmented fifth dominant seventh augmented fifth C7+5, C7♯5 C E G♯ B♭  Play

Play Seventh minor ninth dominant seventh minor ninth C7−9, C7♭9 C E G B♭ D♭  Play

Play Seventh sharp ninth dominant seventh augmented ninth C7+9, C7♯9 C E G B♭ D♯  Play

Play Seventh augmented eleventh dominant seventh augmented eleventh C7+11, C7♯11 C E G B♭ D F♯  Play

Play Seventh diminished thirteenth dominant seventh minor thirteenth C7−13, C7♭13 C E G B♭ D F A♭  Play

Play Half-diminished seventh minor seventh diminished fifth Cø, Cø7, Cm7♭5 C E♭ G♭ B♭  Play

Play

Added tone chords

An added tone chord is a triad with an added, non-tertian note, such as an added sixth or a chord with an added second (ninth) or fourth (eleventh) or a combination of the three. These chords do not include "intervening" thirds as in an extended chord. Added chords can also have variations. Thus, madd9, m4 and m6 are minor triads with extended notes.

Sixth chords can belong to either of two groups. One is first inversion chords and added sixth chords that contain a sixth from the root.[38] The other group is inverted chords in which the interval of a sixth appears above a bass note that is not the root.[39]

The major sixth chord (also called, sixth or added sixth with the chord notation 6, e.g., C6) is by far the most common type of sixth chord of the first group. It comprises a major triad with the added major sixth above the root, common in popular music.[3] For example, the chord C6 contains the notes C–E–G–A. The minor sixth chord (min6 or m6, e.g., Cm6) is a minor triad, still with a major 6. For example, the chord Cm6 contains the notes C–E♭–G–A.

The augmented sixth chord usually appears in chord notation as its enharmonic equivalent, the seventh chord. This chord contains two notes separated by the interval of an augmented sixth (or, by inversion, a diminished third, though this inversion is rare). The augmented sixth is generally used as a dissonant interval most commonly used in motion towards a dominant chord in root position (with the root doubled to create the octave the augmented sixth chord resolves to) or to a tonic chord in second inversion (a tonic triad with the fifth doubled for the same purpose). In this case, the tonic note of the key is included in the chord, sometimes along with an optional fourth note, to create one of the following (illustrated here in the key of C major):

- Italian sixth chord: A♭, C, F♯

- French sixth chord: A♭, C, D, F♯

- German sixth chord: A♭, C, E♭, F♯

The augmented sixth family of chords exhibits certain peculiarities. Since they are not based on triads, as are seventh chords and other sixth chords, they are not generally regarded as having roots (nor, therefore, inversions), although one re-voicing of the notes is common (with the namesake interval inverted to create a diminished third).[40]

The second group of sixth chords includes inverted major and minor chords, which may be called sixth chords in that the six-three (6

3) and six-four (6

4) chords contain intervals of a sixth with the bass note, though this is not the root. Nowadays, this is mostly for academic study or analysis (see figured bass) but the Neapolitan sixth chord is an important example; a major triad with a flat supertonic scale degree as its root that is called a "sixth" because it is almost always found in first inversion. Though a technically accurate Roman numeral analysis would be ♭II, it is generally labelled N6. In C major, the chord is notated (from root position) D♭, F, A♭. Because it uses chromatically altered tones, this chord is often grouped with the borrowed chords but the chord is not borrowed from the relative major or minor and it may appear in both major and minor keys.

Type Components Chord

symbolNotes Audio Chord Interval(s) Add nine major triad major ninth — C2, Cadd9 C E G D  Play

Play Add fourth major triad perfect fourth — C4, Cadd11 C E G F  Play

Play Add sixth major triad major sixth — C6 C E G A  Play

Play Six-nine major triad major sixth major ninth C6/9 C E G A D — Seven-six major triad major sixth minor seventh C7/6 C E G A B♭ — Mixed-third major triad minor third — — C E♭ E G  Play

Play

Suspended chords

A suspended chord, or "sus chord", is a chord in which the third is replaced by either the second or the fourth. This produces two main chord types: the suspended second (sus2) and the suspended fourth (sus4). The chords, Csus2 and Csus4, for example, consist of the notes C–D–G and C–F–G, respectively. There is also a third type of suspended chord, in which both the second and fourth are present, for example the chord with the notes C–D–F–G.

The name suspended derives from an early polyphonic technique developed during the common practice period, in which a stepwise melodic progress to a harmonically stable note in any particular part was often momentarily delayed, or suspended, by extending the duration of the previous note. The resulting unexpected dissonance could then be all the more satisfyingly resolved by the eventual appearance of the displaced note. In traditional music theory, the inclusion of the third in either chord would negate the suspension, so such chords would be called added ninth and added eleventh chords instead.

In modern lay usage, the term is restricted to the displacement of the third only, and the dissonant second or fourth no longer must be held over (prepared) from the previous chord. Neither is it now obligatory for the displaced note to make an appearance at all, though in the majority of cases the conventional stepwise resolution to the third is still observed. In post-bop and modal jazz compositions and improvisations, suspended seventh chords are often used in nontraditional ways: these often do not function as V chords and do not resolve from the fourth to the third. The lack of resolution gives the chord an ambiguous, static quality. Indeed, the third is often played on top of a sus4 chord. A good example is the jazz standard, "Maiden Voyage".

Extended versions are also possible, such as the seventh suspended fourth, which, with root C, contains the notes C–F–G–B♭ and is notated as C7sus4. Csus4 is sometimes written Csus since the sus4 is more common than the sus2.

Type Components Chord

symbolNotes Audio Chord Interval(s) Suspended second open fifth major second — — Csus2 C D G  Play

Play Suspended fourth open fifth perfect fourth — — Csus4 C F G  Play

Play Jazz sus open fifth perfect fourth minor seventh major ninth C9sus4 C F G B♭ D  Play

Play

Borrowed chords

A borrowed chord is one from a different key than the home key, the key of the piece it is used in. The most common occurrence of this is where a chord from the parallel major or minor key is used. Particularly good examples can be found throughout the works of composers such as Schubert. For instance, for a composer working in the C major key, a major ♭III chord (e.g., an E♭ major chord) would be borrowed, as this chord appears only in the key of C minor. Although borrowed chords could theoretically include chords taken from any key other than the home key, this is not how the term is used when a chord is described in formal musical analysis.

When a chord is analysed as "borrowed" from another key it may be shown by the Roman numeral corresponding with that key after a slash. For example, V/V (pronounced "five of five") indicates the dominant chord of the dominant key of the present home-key. The dominant key of C major is G major so this secondary dominant is the chord of the fifth degree of the G major scale, which is D major (which can also be described as II relative to the key of C major, not to be confused with the supertonic ii namely D minor.). If used for a significant duration, the use of the D major chord may cause a modulation to a new key (in this case to G major).

Borrowed chords are widely used in Western popular music and rock music. For example, there are a number of songs in E major which use the ♭III chord (e.g., a G major chord used in an E major song), the ♭VII chord (e.g., a D major chord used in an E major song) and the ♭VI chord (e.g., a C major chord used in an E major song). All of these chords are "borrowed" from the key of E minor.

References

Notes

- Benward & Saker 2003, p. 67 note that "A chord is a harmonic unit with at least three different tones sounding simultaneously." And Benward & Saker 2003, p. 359 "A combination of three or more pitches sounding at the same time." Károlyi 1965, p. 63 notes "Two or more notes sounding simultaneously are known as a chord".

Citations

- Moylan 2014, p. 39.

- Schoenberg 1983, pp. 1–2.

- Benward & Saker 2003, p. 77.

- "Chord". Merriam-Webster's dictionary of English usage. Merriam-Webster. 1995. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-87779-132-4.

- "Chord". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on August 28, 2011.

- Malm 1996, p. 15, "Indeed, this harmonic orientation is one of the major differences between Western and much non-Western music."

- Dahlhaus 2001.

- Nattiez 1990, p. 218.

- Károlyi 1965, p. 63.

- Schoenberg 2010, p. 26, "It is required of a chord that it consist of three different tones."

- Surmani 2004, p. 72.

- Jones 1994, p. 43.

- Monath 1984, p. 37.

- Schellenberg et al. 2005, pp. 551–566.

- Duarter 2008, p. 49.

- Benward & Saker 2003, p. 185.

- Benward & Saker 2003, p. 70.

- Benward & Saker 2003, p. 100.

- Benward & Saker 2003, p. 201.

- Benward & Saker 2003, p. 220.

- Benward & Saker 2003, p. 231.

- Benward & Saker 2003, p. 274.

- Harrison 2005, p. 33.

- Pachet 1999, pp. 187–206.

- Tanguiane 1993.

- Tanguiane 1994.

- Andrews & Sclater 2000, p. 227.

- Benward & Saker 2003, pp. 74–75.

- Haerle 1982, p. 30.

- Policastro 1999, p. 168.

- Benward & Saker 2003, p. 92.

- Weedon 2007.

- Mayfield 2012, p. 523.

- Hanson 1960, p. 7.

- Benjamin et al. 2014, pp. 46–47.

- Benjamin et al. 2014, pp. 48–49.

- Hawkins 1992, pp. 325–335.

- Miller 2005, p. 119.

- Piston 1987, p. 66.

- Bartlette & Laitz 2010.

Sources

- Andrews, William G; Sclater, Molly (2000). Materials of Western Music Part 1. ISBN 1-55122-034-2.

- Bartlette, Christopher; Laitz, Steven G. (2010). Graduate Review of Tonal Theory. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537698-2.

- Benjamin, T.; Horvit, M.; Nelson, R.; Koozin, T. (2014). Techniques and Materials of Music: From the Common Practice Period Through the Twentieth Century (Enhanced ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-285-96580-2.

- Benward, Bruce; Saker, Marilyn (2003). Music in Theory and Practice. Vol. I (' (7th ed.). New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 9780072942620. OCLC 61691613.

- Dahlhaus, Carl (2001). "Harmony". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- Duarter, John (2008). Melody & Harmony for Guitarists. ISBN 978-0-7866-7688-0.

- Harrison, Winston (2005). The Rockmaster System: Relating Ongoing Chords to the Keyboard – Rock, Book 1. Dellwin. ISBN 9780976526704.

- Haerle, Dan (1982). The Jazz Language: A Theory Text for Jazz Composition and Improvisation. ISBN 978-0-7604-0014-2.

- Hanson, Howard (1960). Harmonic Materials of Modern Music. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. LOC 58-8138.

- Hawkins, Stan (October 1992). "Prince- Harmonic Analysis of 'Anna Stesia'". Popular Music. 11 (3): 329, 334n7. doi:10.1017/S0261143000005171.

- Jones, George T. (1994). College Outline Music Theory. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-467168-2.

- Károlyi, Otto (1965). Introducing Music. Penguin. ISBN 9780140206593.

- Malm, William P. (1996). Music Cultures of the Pacific, the Near East, and Asia (3rd ed.). ISBN 0-13-182387-6.

- Mayfield, Connie E. (2012). Theory Essentials. ISBN 978-1-133-30818-8.

- Miller, Michael (2005). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Music Theory. ISBN 978-1-59257-437-7.

- Monath, Norman (1984). How to Play Popular Piano in 10 Easy Lessons. Fireside Books. ISBN 0-671-53067-4.

- Moylan, William (2014). Understanding and Crafting the Mix: The Art of Recording. CRC Press. ISBN 9781136117589.

- Nattiez, Jean-Jacques (1990) [1987 as Musicologie générale et sémiologue]. Music and Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music. Translated by Carolyn Abbate. ISBN 0-691-02714-5.

- Pachet, François (1999). "Surprising Harmonies". International Journal on Computing Anticipatory Systems.

- Piston, Walter (1987). Harmony (5th ed.). New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-95480-3.

- Policastro, Michael A. (1999). Understanding How to Build Guitar Chords and Arpeggios. ISBN 978-0-7866-4443-8.

- Schellenberg, E. Glenn; Bigand, Emmanuel; Poulin-Charronnat, Benedicte; Garnier, Cecilia; Stevens, Catherine (Nov 2005). "Children's implicit knowledge of harmony in Western music". Developmental Science. 8 (6): 551–566. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2005.00447.x. PMID 16246247.

- Schoenberg, Arnold (1983). Structural Functions of Harmony. Faber and Faber.

- Schoenberg, Arnold (2010). Theory of harmony. Berkeley, Calif: University of California. ISBN 978-0-520-26608-7. OCLC 669843249.

- Surmani, Andrew (2004). Essentials of Music Theory: A Complete Self-Study Course for All Musicians. ISBN 0-7390-3635-1.

- Tanguiane, Andranick (1993). Artificial Perception and Music Recognition. Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence. Vol. 746. Berlin-Heidelberg: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-57394-4.

- Tanguiane, Andranick (1994). "A principle of correlativity of perception and its application to music recognition". Music Perception. 11 (4): 465–502. doi:10.2307/40285634. JSTOR 40285634.

- Weedon, Bert (2007). Play in a Day. Faber Music. ISBN 978-0-571-52965-0.

Further reading

- Dahlhaus, Carl. Gjerdingen, Robert O. trans. (1990). Studies in the Origin of Harmonic Tonality, p. 67. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-09135-8.

- Grout, Donald Jay (1960). A History Of Western Music. Norton Publishing.

- Persichetti, Vincent (1961). Twentieth-century Harmony: Creative Aspects and Practice. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-09539-8. OCLC 398434.

- Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell, eds. (2001). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. ISBN 1-56159-239-0.

- Schejtman, Rod (2008). Music Fundamentals. The Piano Encyclopedia. ISBN 978-987-25216-2-2. Archived from the original on 2018-08-31. Retrieved 2020-07-20.

External links

Quotations related to Chord (music) at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Chord (music) at Wikiquote Media related to Chords at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Chords at Wikimedia Commons