Cortes Generales

The Cortes Generales (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈkoɾtes xeneˈɾales]; English: Spanish Parliament, lit. 'General Courts') are the bicameral legislative chambers of Spain, consisting of the Congress of Deputies (the lower house), and the Senate (the upper house).

General Courts Cortes Generales | |

|---|---|

| 14th Cortes Generales | |

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Houses | Senate Congress of Deputies |

| Leadership | |

President of the Senate | |

President of the Congress of Deputies | |

| Structure | |

| Seats | 615 265 senators 350 deputies |

| |

Senate political groups | Government (115)

Supported by (34)

Opposition (116)

|

| |

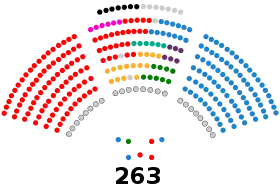

Congress of Deputies political groups | Government (155)

Supported by (34)

Opposition (161)

|

| Elections | |

Senate first election | 15 June 1977 |

Congress of Deputies first election | January–September 1810 |

Senate last election | 10 November 2019 |

Congress of Deputies last election | 10 November 2019 |

Senate next election | No later than 10 December 2023 |

Congress of Deputies next election | No later than 10 December 2023 |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Senate Palacio del Senado Plaza de la Marina Española Centro, Madrid | |

_17.jpg.webp) | |

| Congress of Deputies Palacio de las Cortes Carrera de San Jerónimo Centro, Madrid | |

| Website | |

| cortesgenerales | |

.svg.png.webp) |

|---|

|

The Congress of Deputies meets in the Palacio de las Cortes. The Senate meets in the Palacio del Senado. Both are in Madrid. The Cortes are elected through universal, free, equal, direct and secret suffrage,[2] with the exception of some senatorial seats, which are elected indirectly by the legislatures of the autonomous communities. The Cortes Generales are composed of 615 members: 350 Deputies and 265 Senators.

The members of the Cortes Generales serve four-year terms, and they are representatives of the Spanish people.[3] In both chambers, the seats are divided by constituencies that correspond with the fifty provinces of Spain, plus Ceuta and Melilla. However, the Canary and Balearic islands form different constituencies in the Senate.

As a parliamentary system, the Cortes confirm and dismiss the Prime Minister of Spain and his or her government; specifically, the candidate for Prime Minister has to be invested by the Congress with a majority of affirmative votes. The Congress can also dismiss the Prime Minister through a vote of no confidence. The Cortes also hold the power to enact a constitutional reform.

The modern Cortes Generales were created by the 1978 Constitution of Spain, but the institution has a long history.

History of the Spanish legislature

Feudal Age (8th–12th centuries)

The system of Cortes arose in The Middle Ages as part of feudalism. A "Corte" was an advisory council made up of the most powerful feudal lords closest to the king. The Cortes of León was the first parliamentary body in Western Europe.[4] From 1230, the Cortes of Leon and Castile were merged, though the Cortes' power was decreasing. Prelates, nobles and commoners remained separated in the three estates within the Cortes. The king had the ability to call and dismiss the Cortes, but, as the lords of the Cortes headed the army and controlled the purse, the King usually signed treaties with them to pass bills for war at the cost of concessions to the lords and the Cortes.

Rise of the bourgeoisie (12th–15th centuries)

With the reappearance of the cities near the 12th century, a new social class started to grow: people living in the cities were neither vassals (servants of feudal lords) nor nobles themselves. Furthermore, the nobles were experiencing very hard economic times due to the Reconquista; so now the bourgeoisie (Spanish burguesía, from burgo, city) had the money and thus the power. So the King started admitting representatives from the cities to the Cortes in order to get more money for the Reconquista. The frequent payoffs were the "Fueros", grants of autonomy to the cities and their inhabitants. At this time the Cortes already had the power to oppose the King's decisions, thus effectively vetoing them. In addition, some representatives (elected from the Cortes members by itself) were permanent advisors to the King, even when the Cortes were not.

Catholic Monarchs (15th century)

Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon, the Catholic Monarchs, started a specific policy to diminish the power of the bourgeoisie and nobility. They greatly reduced the powers of the Cortes to the point where they simply rubberstamped the monarch's acts, and brought the nobility to their side. One of the major points of friction between the Cortes and the monarchs was the power of raising and lowering taxes. It was the only matter that the Cortes had under some direct control; when Queen Isabella wanted to fund Voyages of Christopher Columbus, she had a hard time battling with the bourgeoisie to get the Cortes' approval.

Imperial Cortes (16th–17th centuries)

The role of the Cortes during the Spanish Empire was mainly to rubberstamp the decisions of the ruling monarch. However, they had some power over economic and American affairs, especially taxes. The Siglo de oro, the Spanish Golden Age of arts and literature, was a dark age in Spanish politics: the Netherlands declared itself independent and started a war, while some of the last Habsburg monarchs did not rule the country, leaving this task in the hands of prime ministers governing in their name, the most famous being the Count-Duke of Olivares, Philip IV's deputy. This allowed the Cortes to become more influential, even when they did not directly oppose the King's decisions (or prime minister' decisions in the name of the King).

The institutions in charge of enforcing the decisions of the Imperial Cortes was the Diputación General de Cortes, a body of representatives elected by the different estates of the realm. The Diputación dealt with the implementetion of previous agreements and the collection of taxes. This was established after the comunero rebellion to improve the relationship between the king and the local assemblies. There were also Diputaciones in the Kingdoms of Aragon and Navarre.[5]

Cortes in Aragon and in Navarre

Some lands of the Crown of Aragon (Aragon, Catalonia and Valencia) and the Kingdom of Navarre were self-governing entities until the Nueva Planta Decrees of 1716 abolished their autonomy and united Aragon with Castile in a centralised Spanish state. The abolition in the realms of Aragon was completed by 1716, whilst Navarre retained its autonomy until the 1833 territorial division of Spain.[6] It is the only one of the Spanish territories whose current status in the Spanish state is legally linked with the old Fueros: its Statute of Autonomy specifically cites them and recognizes their special status, while also recognizing the supremacy of the Spanish Constitution.

Cortes (or Corts in Catalonia and Valencia) existed in each of Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia and Navarre. It is thought that these legislatures exercised more real power over local affairs than the Castilian Cortes did. Executive councils also existed in each of these realms, which were initially tasked with overseeing the implementation of decisions made by the Cortes.

Cádiz Cortes (1808–14) and three liberal years (1820–23)

Cortes of Cádiz operated as a government in exile. France under Napoleon had taken control of most of Spain during the Peninsular War after 1808. The Cortes found refuge in the fortified, coastal city of Cádiz. General Cortes were assembled in Cádiz, but since many provinces could not send representatives due to the French occupation, substitutes were chosen among the people of the city. Liberal factions dominated the body and pushed through the Spanish Constitution of 1812. Ferdinand VII, however, tossed it aside upon his restoration in 1814 and pursued conservative policies, making the constitution an icon for liberal movements in Spain. Many military coups were attempted, and finally Col. Rafael del Riego's one succeeded and forced the King to accept the liberal constitution, which resulted in the Three Liberal Years (Trienio Liberal). The monarch not only did everything he could to obstruct the Government (vetoing nearly every law, for instance), but also asked many powers, including the Holy Alliance, to invade his own country and restore his absolutist powers. He finally received a French army (The Hundred Thousand Sons of St. Louis) which only met resistance in the liberal cities, but easily crushed the National Militia and forced many liberals to exile to, ironically, France. In his second absolutist period up to his death in 1833, Ferdinand VII was more cautious and did not try a full restoration of the Ancien Régime.

First Spanish Republic (1873–1874)

When the monarchy was overthrown in 1873, the King of Spain was forced into exile. The Senate was abolished because of its royally appointed nature. A republic was proclaimed and the Congress of Deputies members started writing a Constitution, supposedly that of a federal republic, with the power of Parliament being nearly supreme (see parliamentary supremacy, although Spain did not use the Westminster system). However, due to numerous issues Spain was not poised to become a republic; after several crises the republic collapsed, and the monarchy was restored in 1874.

Restoration (1874–1930)

The regime just after the First Republic is called the Bourbon Restoration. It was formally a constitutional monarchy, with the monarch as a rubberstamp to the Cortes' acts but with some reserve powers, such as appointing and dismissing the Prime Minister and appointing senators for the new Senate, remade as an elected House.

Soon after the Soviet revolution (1917), the Spanish political parties started polarizing, and the left-wing Communist Party (PCE) and Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) blamed the Government for supposed election fraud in small towns (caciquismo), which was incorrectly supposed to have been wiped out in the 1900s by the failed regenerationist movement. In the meantime, spiralling violence started with the murders of many leaders by both sides. Deprived of those leaders, the regime entered a general crisis, with extreme police measures which led to a dictatorship (1921–1930) during which the Senate was again abolished.

Second Spanish Republic (1931–1939)

The dictatorship, now ruled by Admiral Aznar-Cabañas, called for local elections. The results were overwhelmingly favorable to the monarchist cause nationally, but most provincial capitals and other sizable cities sided heavily with the republicans. This was interpreted as a victory, as the rural results were under the always-present suspicion of caciquismo and other irregularities while the urban results were harder to influence. The King left Spain, and a Republic was declared on April 14, 1931.

The Second Spanish Republic was established as a presidential republic, with a unicameral Parliament and a President of the Republic as the Head of State. Among his powers were the appointment and dismissal of the Prime Minister, either on the advice of Parliament or just having consulted it before, and a limited power to dissolve the Parliament and call for new elections.

The first term was the constituent term charged with creating the new Constitution, with the ex-monarchist leader Niceto Alcalá Zamora as President of the Republic and the left-wing leader Manuel Azaña as Prime Minister. The election gave a majority in the Cortes and thus, the Government, to a coalition between Azaña's party and the PSOE. A remarkable deed is universal suffrage, allowing women to vote, a provision highly criticized by Socialist leader Indalecio Prieto, who said the Republic had been backstabbed. Also, for the second time in Spanish history, some regions were granted autonomous governments within the unitary state. Many on the extreme right rose up with General José Sanjurjo in 1932 against the Government's social policies, but the coup was quickly defeated.

The elections for the second term were held in 1933 and won by the coalition between the Radical Party (center) and the Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas (CEDA) (right). Initially, only the Radical Party entered the Government, with the parliamentary support of the CEDA. However, in the middle of the term, several corruption scandals (among them the Straperlo affair) sunk the Radical Party and the CEDA entered the Government in 1934. This led to uprisings by some leftist parties that were quickly suffocated. In one of them, the left wing government of Catalonia, which had been granted home rule, formally rebelled against the central government, denying its power. This provoked the dissolution of the Generalitat de Catalunya and the imprisonment of their leaders. The leftist minority in the Cortes then pressed Alcalá Zamora for a dissolution, arguing that the uprising were the consequence of social rejection of the right-wing government. The President, a former monarchist Minister wary of the authoritarism of the right, dissolved Parliament.

The next election was held in 1936. It was hotly contested, with all parties converging into three coalitions: the leftist Popular Front, the right-winged National Front and a Centre coalition. In the end, the Popular Front won with a small edge in votes over the runner-up National Front, but achieved a solid majority due to the new electoral system introduced by the CEDA government hoping that they would get the edge in votes. The new Parliament then dismissed Alcalá-Zamora and installed Manuel Azaña in his place. During the third term, the extreme polarisation of the Spanish society was more evident than ever in Parliament, with confrontation reaching the level of death threats. The already bad political and social climate created by the long term left-right confrontation worsened, and many right-wing rebellions were started. Then, in 1936, the Army's failed coup degenerated into the Spanish Civil War, putting an end to the Second Republic.

From November 1936 to October 1937, the Cortes were held at Valencia City Hall, which was still being used for its local purposes at the same time. The building was a target for the Italian Air Force in service of the Nationalist faction, resulting in a bombing in May 1937.[7]

Franco's dictatorship: the Cortes Españolas (1943–1977)

Francisco Franco did not have the creation of a consultative or legislative type of assembly as priority.[8] In 1942, following the first symptoms of change in the international panorama in favour of the Allied Powers, a law established the Cortes Españolas (Francoist Cortes), a non-democratic chamber made up of more than 400 procuradores (singular procurador). Both the Cortes' founding law and the subsequent regulations were based on the principles of rejection of parliamentarism and political pluralism.[9] Members of the Cortes were not elected and exercised only symbolic power. It had no power over government spending, and the cabinet, appointed and dismissed by Franco alone, retained real legislative authority. In 1967, with the enaction of the Organic Law of the State, the accommodation of "two family representatives per province, elected by those on the electoral roll of family heads and married women" (the so-called tercio familiar) ensued, opening a fraction of the Cortes' composition to some mechanisms of individual participation.[10]

Cortes Generales under the Constitution of 1978

.jpg.webp)

The Cortes are a bicameral parliament composed of a lower house (Congreso de los Diputados, congress of deputies) and an upper house (Senado, senate). Although they share legislative power, the Congress holds the power to ultimately override any decision of the Senate by a sufficient majority (usually an absolute majority or three-fifths majority).

The Congress is composed of 350 deputies (but that figure may change in the future as the constitution establishes a maximum of 400 and a minimum of 300) directly elected by universal suffrage approximately every four years.

The Senate is partly directly elected in that four senators per province are elected as a general rule and partly appointed by the legislative assemblies of the autonomous communities, one for each community and another one for every million inhabitants in their territory. Although the Senate was conceived as a territorial upper house, it has been argued by nationalist parties and the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party that it does not accomplish such a task because 208 out of 265 members of the Senate are elected by popular vote in each province, and only 58 are representatives appointed by the regional legislatures of autonomous communities. Proposals to reform the Senate have been discussed for at least ten years as of November 2007. One of the main themes of reform is to move towards a higher level of federalization and make the Senate a thorough representation of autonomous communities instead of the current system, which tries to incorporate the interests of province and autonomous communities at the same time.

Joint Committees

| Committee | Office | Chair(s) | Term | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relations with the Court of Auditors | deputy | Santos Cerdán León (PSOE) | 2020–present | [11] |

| European Union | deputy | Susana Sumelzo Jordán (PSOE) | 2020–present | [12] |

| Relations with the Ombudsman | deputy | Vicente Tirado Ochoa (PP) | 2020–present | [13] |

| Parliamentary Control of RTVE's Board and its Partnerships | senator | Antonio José Cosculluela Bergua (PSOE) | 2020–present | [14] |

| National Security | deputy | Carlos Aragonés Mendiguchía (PP) | 2020–present | [15] |

| Study of Addictions' Issues | deputy | Francesc Xavier Eritja Ciuró (ERC) | 2020–present | [16] |

| Coordination and Monitoring of the Spanish Strategy to accomplish the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) | deputy | Joan Mena Arca (ECP) | 2020 | [17] |

| deputy | Aina Vidal Saéz (ECP) | 2020–present |

See also

- List of presidents of the Congress of Deputies of Spain

- Solemn Opening of the Parliament of Spain

- Bureaus of the Cortes Generales

Notes

References

- "El PRC y el PSOE cierran su crisis a cambio del apoyo de Revilla a los Presupuestos de Sánchez". El Español (in Spanish). 13 January 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Article 68.1 and 69.1 of the Constitution of Spain (1978)

- Article 66 of the Constitution of Spain (1978)

- John Keane, The Life and Death of Democracy. Simon & Schuster, London, 2009

- García de Cortázar, J. A. (1978). Historia de España. Alfaguara. p. 306. ISBN 8420620408.

- García de Cortázar y Ruiz de Aguirre, José Angel (1976). La época medieval (3 ed.). Madrid: Alfaguara. p. 250. ISBN 84-206-2040-8. OCLC 3315063.

- "Cuando el Ayuntamiento de Valencia fue bombardeado" [When Valencia City Hall was bombed]. El País (in Spanish). 30 May 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2022.

- Giménez Martínez 2015, pp. 71–72.

- Giménez Martínez, Miguel Ángel (2015). "Las Cortes de Franco o el Parlamento imposible" (PDF). Trocadero: Revista de historia moderna y contemporánea (27): 73. ISSN 0214-4212.

- Giménez Martínez 2015, p. 75.

- "Current membership of Comisión Mixta para las Relaciones con el Tribunal de Cuentas". Congreso de los Diputados. Archived from the original on 11 September 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- "Current membership of Comisión Mixta para la Unión Europea". Congreso de los Diputados. Archived from the original on 11 September 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- "Current membership of Comisión Mixta de Relaciones con el Defensor del Pueblo". Congreso de los Diputados. Archived from the original on 11 September 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- "Current membership of Comisión Mixta de Control Parlamentario de la Corporación RTVE y sus Sociedades". Congreso de los Diputados. Archived from the original on 11 September 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- "Current membership of Comisión Mixta de Seguridad Nacional". Congreso de los Diputados. Archived from the original on 11 September 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- "Current membership of Comisión Mixta para el Estudio de los Problemas de las Adicciones". Congreso de los Diputados. Archived from the original on 11 September 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- "Current membership of Comisión Mixta para la Coordinación y Seguimiento de la Estrategia Española para alcanzar los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible (ODS)". Congreso de los Diputados. Archived from the original on 11 September 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2021.