Creative Commons license

A Creative Commons (CC) license is one of several public copyright licenses that enable the free distribution of an otherwise copyrighted "work".[note 1] A CC license is used when an author wants to give other people the right to share, use, and build upon a work that the author has created. CC provides an author flexibility (for example, they might choose to allow only non-commercial uses of a given work) and protects the people who use or redistribute an author's work from concerns of copyright infringement as long as they abide by the conditions that are specified in the license by which the author distributes the work.[1][2][3][4][5]

There are several types of Creative Commons licenses. Each license differs by several combinations that condition the terms of distribution. They were initially released on December 16, 2002, by Creative Commons, a U.S. non-profit corporation founded in 2001. There have also been five versions of the suite of licenses, numbered 1.0 through 4.0.[6] Released in November 2013, the 4.0 license suite is the most current. While the Creative Commons license was originally grounded in the American legal system, there are now several Creative Commons jurisdiction ports which accommodate international laws.

In October 2014, the Open Knowledge Foundation approved the Creative Commons CC BY, CC BY-SA and CC0 licenses as conformant with the "Open Definition" for content and data.[7][8][9]

History and international use

Lawrence Lessig and Eric Eldred designed the Creative Commons License (CCL) in 2001 because they saw a need for a license between the existing modes of copyright and public domain status. Version 1.0 of the licenses was officially released on 16 December 2002.[10]

Origins

The CCL allows inventors to keep the rights to their innovations while also allowing for some external use of the invention.[11] The CCL emerged as a reaction to the decision in Eldred v. Ashcroft, in which the United States Supreme Court ruled constitutional provisions of the Copyright Term Extension Act that extended the copyright term of works to be the last living author's lifespan plus an additional 70 years.[11]

License porting

The original non-localized Creative Commons licenses were written with the U.S. legal system in mind; therefore, the wording may be incompatible with local legislation in other jurisdictions, rendering the licenses unenforceable there. To address this issue, Creative Commons asked its affiliates to translate the various licenses to reflect local laws in a process called "porting".[12] As of July 2011, Creative Commons licenses have been ported to over 50 jurisdictions worldwide.[13]

Chinese use of the Creative Commons license

Working with Creative Commons, the Chinese government adapted the Creative Commons License to the Chinese context, replacing the individual monetary compensation of U.S. copyright law with incentives to Chinese innovators to innovate as a social contribution.[14] In China, the resources of society are thought to enable an individual's innovations; the continued betterment of society serves as its own reward.[15] Chinese law heavily prioritizes the eventual contributions that an invention will have towards society's growth, resulting in initial laws placing limits on the length of patents and very stringent conditions regarding the use and qualifications of inventions.[15]

"Info-communism"

An idea sometimes called "info-communism" found traction in the Western world after researchers at MIT grew frustrated over having aspects of their code withheld from the public.[16] Modern copyright law roots itself in motivating innovation through rewarding innovators for socially valuable inventions. Western patent law assumes that (1) there is a right to use an invention for commerce and (2) it is up to the patentee's discretion to limit that right.[17] The MIT researchers, led by Richard Stallman, argued for the more open proliferation of their software's use for two primary reasons: the moral obligation of altruism and collaboration, and the unfairness of restricting the freedoms of other users by depriving them of non-scarce resources.[16] As a result, they developed the General Public License (GPL), a precursor to the Creative Commons License based on existing American copyright and patent law.[16] The GPL allowed the economy around a piece of software to remain capitalist by allowing programmers to commercialize products that use the software, but also ensured that no single person had complete and exclusive rights to the usage of an innovation.[16] Since then, info-communism has gained traction, with some scholars arguing in 2014 that Wikipedia itself is a manifestation of the info-communist movement.[18]

Applicable works

Work licensed under a Creative Commons license is governed by applicable copyright law.[19] This allows Creative Commons licenses to be applied to all work falling under copyright, including: books, plays, movies, music, articles, photographs, blogs, and websites.

Software

While software is also governed by copyright law and CC licenses are applicable, the CC recommends against using it in software specifically due to backward-compatibility limitations with existing commonly used software licenses.[20][21] Instead, developers may resort to use more software-friendly free and open-source software (FOSS) software licenses. Outside the FOSS licensing use case for software there are several usage examples to utilize CC licenses to specify a "Freeware" license model; examples are The White Chamber, Mari0 or Assault Cube.[22] Despite the status of CC0 as the most free copyright license, the Free Software Foundation does not recommend releasing software into the public domain using the CC0.[23]

However, application of a Creative Commons license may not modify the rights allowed by fair use or fair dealing or exert restrictions which violate copyright exceptions.[24] Furthermore, Creative Commons licenses are non-exclusive and non-revocable.[25] Any work or copies of the work obtained under a Creative Commons license may continue to be used under that license.[26]

When works are protected by more than one Creative Commons license, the user may choose any of them.[27]

Preconditions

The author, or the licensor in case the author did a contractual transfer of rights, need to have the exclusive rights on the work. If the work has already been published under a public license, it can be uploaded by any third party, once more on another platform, by using a compatible license, and making reference and attribution to the original license (e.g. by referring the URL of the original license).[17]

Consequences

The license is non-exclusive, royalty-free, and unrestricted in terms of territory and duration, so it is irrevocable, unless a new license is granted by the author after the work has been significantly modified. Any use of the work that is not covered by other copyright rules triggers the public license. Upon activation of the license, the licensee must adhere to all conditions of the license, otherwise the license agreement is illegitimate, and the licensee would commit a copyright infringement. The author, or the licensor as a proxy, has the legal rights to act upon any copyright infringement. The licensee has a limited period to correct any non-compliance.[17]

Types of licenses

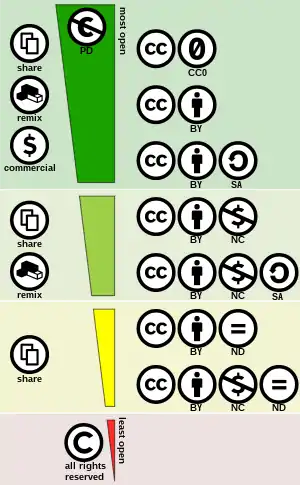

Creative commons license spectrum between public domain (top) and all rights reserved (bottom). Left side indicates the use-cases allowed, right side the license components. The dark green area indicates Free Cultural Works compatible licenses, the two green areas compatibility with the Remix culture. |

CC license usage in 2014 (top and middle), "Free cultural works" compatible license usage 2010 to 2014 (bottom) |

Four rights

The CC licenses all grant "baseline rights", such as the right to distribute the copyrighted work worldwide for non-commercial purposes and without modification.[28] In addition, different versions of license prescribe different rights, as shown in this table:[29]

| Icon | Right | Description |

|---|---|---|

|

Attribution (BY) | Licensees may copy, distribute, display, perform and make derivative works and remixes based on it only if they give the author or licensor the credits (attribution) in the manner specified by these. Since version 2.0, all Creative Commons licenses require attribution to the creator and include the BY element. |

|

Share-alike (SA) | Licensees may distribute derivative works only under a license identical to ("not more restrictive than") the license that governs the original work. (See also copyleft.) Without share-alike, derivative works might be sublicensed with compatible but more restrictive license clauses, e.g. CC BY to CC BY-NC.) |

|

Non-commercial (NC) | Licensees may copy, distribute, display, perform the work and make derivative works and remixes based on it only for non-commercial purposes. |

|

No derivative works (ND) | Licensees may copy, distribute, display and perform only verbatim copies of the work, not derivative works and remixes based on it. Since version 4.0, derivative works are allowed but must not be shared. |

The last two clauses are not free content licenses, according to definitions such as DFSG or the Free Software Foundation's standards, and cannot be used in contexts that require these freedoms, such as Wikipedia. For software, Creative Commons includes three free licenses created by other institutions: the BSD License, the GNU LGPL, and the GNU GPL.[30]

Mixing and matching these conditions produces sixteen possible combinations, of which eleven are valid Creative Commons licenses and five are not. Of the five invalid combinations, four include both the "nd" and "sa" clauses, which are mutually exclusive; and one includes none of the clauses. Of the eleven valid combinations, the five that lack the "by" clause have been retired because 98% of licensors requested attribution, though they do remain available for reference on the website.[31][32][33] This leaves six regularly used licenses plus the CC0 public domain declaration.

Six regularly used licenses

The six licenses in most frequent use are shown in the following table. Among them, those accepted by the Wikimedia Foundation – the public domain dedication and two attribution (BY and BY-SA) licenses – allow the sharing and remixing (creating derivative works), including for commercial use, so long as attribution is given.[33][34][35]

| License name | Abbreviation | Icon | Attribution required | Allows remix culture | Allows commercial use | Allows Free Cultural Works | Meets the OKF 'Open Definition' |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attribution | BY | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Attribution-ShareAlike | BY-SA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Attribution-NonCommercial | BY-NC | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | |

| Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike | BY-NC-SA | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | |

| Attribution-NoDerivatives | BY-ND | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | |

| Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives | BY-NC-ND | Yes | No | No | No | No |

Zero / public domain

| Tool name | Abbreviation | Icon | Attribution required | Allows remix culture | Allows commercial use | Allows Free Cultural Works | Meets the OKF 'Open Definition' |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| "No Rights Reserved" | CC0 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Besides copyright licenses, Creative Commons also offers CC0, a tool for relinquishing copyright and releasing material into the public domain.[35] CC0 is a legal tool for waiving as many rights as legally possible.[37] Or, when not legally possible, CC0 acts as fallback as public domain equivalent license.[37] Development of CC0 began in 2007[38] and it was released in 2009.[39][40] A major target of the license was the scientific data community.[41]

In 2010, Creative Commons announced its Public Domain Mark,[42] a tool for labeling works already in the public domain. Together, CC0 and the Public Domain Mark replace the Public Domain Dedication and Certification,[43] which took a U.S.-centric approach and co-mingled distinct operations.

In 2011, the Free Software Foundation added CC0 to its free software licenses. However, despite CC0 being the most free and open copyright license, the Free Software Foundation currently does not recommend using CC0 to release software into the public domain because it lacks a patent grant.[23]

In February 2012, CC0 was submitted to Open Source Initiative (OSI) for their approval.[44] However, controversy arose over its clause which excluded from the scope of the license any relevant patents held by the copyright holder. This clause was added with scientific data in mind rather than software, but some members of the OSI believed it could weaken users' defenses against software patents. As a result, Creative Commons withdrew their submission, and the license is not currently approved by the OSI.[41][45]

From 2013 to 2017, the stock photography website Unsplash used the CC0 license,[46][47] distributing several million free photos a month.[48] Lawrence Lessig, the founder of Creative Commons, has contributed to the site.[49] Unsplash moved from using the CC0 license to a custom license in June 2017[50] and to an explicitly nonfree license in January 2018.

In October 2014, the Open Knowledge Foundation approved the Creative Commons CC0 as conformant with the Open Definition and recommend the license to dedicate content to the public domain.[8][9]

A popular Linux distribution named Fedora Linux has disallowed software that are licensed under CC0 in July 2022 due to patent rights not being waived under the license.[51]

Retired licenses

Due to either disuse or criticism, a number of previously offered Creative Commons licenses have since been retired,[31][52] and are no longer recommended for new works. The retired licenses include all licenses lacking the Attribution element other than CC0, as well as the following four licenses:

- Developing Nations License: a license which only applies to developing countries deemed to be "non-high-income economies" by the World Bank. Full copyright restrictions apply to people in other countries.[53]

- Sampling: parts of the work can be used for any purpose other than advertising, but the whole work cannot be copied or modified[54]

- Sampling Plus: parts of the work can be copied and modified for any purpose other than advertising, and the entire work can be copied for noncommercial purposes[55]

- NonCommercial Sampling Plus: the whole work or parts of the work can be copied and modified for non-commercial purposes[56]

Version 4.0

The latest version 4.0 of the Creative Commons licenses, released on November 25, 2013, are generic licenses that are applicable to most jurisdictions and do not usually require ports.[57][58][59][60] No new ports have been implemented in version 4.0 of the license.[61] Version 4.0 discourages using ported versions and instead acts as a single global license.[62]

Rights and obligations

Attribution

Since 2004, all current licenses other than the CC0 variant require attribution of the original author, as signified by the BY component (as in the preposition "by").[32] The attribution must be given to "the best of [one's] ability using the information available".[63] Creative Commons suggests the mnemonic "TASL": title -- author -- source [web link] -- [CC] licence.

Generally this implies the following:

- Include any copyright notices (if applicable). If the work itself contains any copyright notices placed there by the copyright holder, those notices must be left intact, or reproduced in a way that is reasonable to the medium in which the work is being re-published.

- Cite the author's name, screen name, or user ID, etc. If the work is being published on the Internet, it is nice to link that name to the person's profile page, if such a page exists.

- Cite the work's title or name (if applicable), if such a thing exists. If the work is being published on the Internet, it is nice to link the name or title directly to the original work.

- Cite the specific CC license the work is under. If the work is being published on the Internet, it is nice if the license citation links to the license on the CC website.

- Mention if the work is a derivative work or adaptation. In addition to the above, one needs to identify that their work is a derivative work, e.g., "This is a Finnish translation of [original work] by [author]." or "Screenplay based on [original work] by [author]."

Non-commercial licenses

The "non-commercial" option included in some Creative Commons licenses is controversial in definition,[64] as it is sometimes unclear what can be considered a non-commercial setting, and application, since its restrictions differ from the principles of open content promoted by other permissive licenses.[65] In 2014 Wikimedia Deutschland published a guide to using Creative Commons licenses as wiki pages for translations and as PDF.[17]

Adaptability

Rights in an adaptation can be expressed by a CC license that is compatible with the status or licensing of the original work or works on which the adaptation is based.[66]

Legal aspects

The legal implications of large numbers of works having Creative Commons licensing are difficult to predict, and there is speculation that media creators often lack insight to be able to choose the license which best meets their intent in applying it.[69]

Some works licensed using Creative Commons licenses have been involved in several court cases.[70] Creative Commons itself was not a party to any of these cases; they only involved licensors or licensees of Creative Commons licenses. When the cases went as far as decisions by judges (that is, they were not dismissed for lack of jurisdiction or were not settled privately out of court), they have all validated the legal robustness of Creative Commons public licenses.

Dutch tabloid

In early 2006, podcaster Adam Curry sued a Dutch tabloid who published photos from Curry's Flickr page without Curry's permission. The photos were licensed under the Creative Commons Non-Commercial license. While the verdict was in favor of Curry, the tabloid avoided having to pay restitution to him as long as they did not repeat the offense. Professor Bernt Hugenholtz, main creator of the Dutch CC license and director of the Institute for Information Law of the University of Amsterdam, commented, "The Dutch Court's decision is especially noteworthy because it confirms that the conditions of a Creative Commons license automatically apply to the content licensed under it, and binds users of such content even without expressly agreeing to, or having knowledge of, the conditions of the license."[71][72][73][74]

Virgin Mobile

In 2007, Virgin Mobile Australia launched an advertising campaign promoting their cellphone text messaging service using the work of amateur photographers who uploaded their work to Flickr using a Creative Commons-BY (Attribution) license. Users licensing their images this way freed their work for use by any other entity, as long as the original creator was attributed credit, without any other compensation required. Virgin upheld this single restriction by printing a URL leading to the photographer's Flickr page on each of their ads. However, one picture, depicting 15-year-old Alison Chang at a fund-raising carwash for her church,[75] caused some controversy when she sued Virgin Mobile. The photo was taken by Alison's church youth counselor, Justin Ho-Wee Wong, who uploaded the image to Flickr under the Creative Commons license.[75] In 2008, the case (concerning personality rights rather than copyright as such) was thrown out of a Texas court for lack of jurisdiction.[76][77]

SGAE vs Fernández

In the fall of 2006, the collecting society Sociedad General de Autores y Editores (SGAE) in Spain sued Ricardo Andrés Utrera Fernández, owner of a disco bar located in Badajoz who played CC-licensed music. SGAE argued that Fernández should pay royalties for public performance of the music between November 2002 and August 2005. The Lower Court rejected the collecting society's claims because the owner of the bar proved that the music he was using was not managed by the society.[78]

In February 2006, the Cultural Association Ladinamo (based in Madrid, and represented by Javier de la Cueva) was granted the use of copyleft music in their public activities. The sentence said:

Admitting the existence of music equipment, a joint evaluation of the evidence practiced, this court is convinced that the defendant prevents communication of works whose management is entrusted to the plaintiff [SGAE], using a repertoire of authors who have not assigned the exploitation of their rights to the SGAE, having at its disposal a database for that purpose and so it is manifested both by the legal representative of the Association and by Manuela Villa Acosta, in charge of the cultural programming of the association, which is compatible with the alternative character of the Association and its integration in the movement called 'copy left'.[79]

GateHouse Media, Inc. v. That's Great News, LLC

On June 30, 2010, GateHouse Media filed a lawsuit against That's Great News. GateHouse Media owns a number of local newspapers, including Rockford Register Star, which is based in Rockford, Illinois. That's Great News makes plaques out of newspaper articles and sells them to the people featured in the articles.[80] GateHouse sued That's Great News for copyright infringement and breach of contract. GateHouse claimed that TGN violated the non-commercial and no-derivative works restrictions on GateHouse Creative Commons licensed work when TGN published the material on its website. The case was settled on August 17, 2010, though the settlement was not made public.[80][81]

Drauglis v. Kappa Map Group, LLC

The plaintiff was photographer Art Drauglis, who uploaded several pictures to the photo-sharing website Flickr using Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License (CC BY-SA), including one entitled "Swain's Lock, Montgomery Co., MD.". The defendant was Kappa Map Group, a map-making company, which downloaded the image and used it in a compilation entitled "Montgomery Co. Maryland Street Atlas". Though there was nothing on the cover that indicated the origin of the picture, the text "Photo: Swain's Lock, Montgomery Co., MD Photographer: Carly Lesser & Art Drauglis, Creative Commoms [sic], CC-BY-SA-2.0" appeared at the bottom of the back cover.

The validity of the CC BY-SA 2.0 as a license was not in dispute. The CC BY-SA 2.0 requires that the licensee to use nothing less restrictive than the CC BY-SA 2.0 terms. The atlas was sold commercially and not for free reuse by others. The dispute was whether Drauglis' license terms that would apply to "derivative works" applied to the entire atlas. Drauglis sued the defendants in June 2014 for copyright infringement and license breach, seeking declaratory and injunctive relief, damages, fees, and costs. Drauglis asserted, among other things, that Kappa Map Group "exceeded the scope of the License because defendant did not publish the Atlas under a license with the same or similar terms as those under which the Photograph was originally licensed."[82] The judge dismissed the case on that count, ruling that the atlas was not a derivative work of the photograph in the sense of the license, but rather a collective work. Since the atlas was not a derivative work of the photograph, Kappa Map Group did not need to license the entire atlas under the CC BY-SA 2.0 license. The judge also determined that the work had been properly attributed.[83]

In particular, the judge determined that it was sufficient to credit the author of the photo as prominently as authors of similar authorship (such as the authors of individual maps contained in the book) and that the name "CC-BY-SA-2.0" is sufficiently precise to locate the correct license on the internet and can be considered a valid URI of the license.[84]

Verband zum Schutz geistigen Eigentums im Internet (VGSE)

In July 2016, German computer magazine LinuxUser reported that a German blogger Christoph Langner used two CC-BY licensed photographs from Berlin photographer Dennis Skley on his private blog Linuxundich. Langner duly mentioned the author and the license and added a link to the original. Langner was later contacted by the Verband zum Schutz geistigen Eigentums im Internet (VGSE) (Association for the Protection of Intellectual Property in the Internet) with a demand for €2300 for failing to provide the full name of the work, the full name of the author, the license text, and a source link, as is required by the fine print in the license. Of this sum, €40 goes to the photographer, and the remainder is retained by VGSE.[85][86] The Higher Regional Court of Köln dismissed the claim in May 2019.[87]

Works with a Creative Commons license

Creative Commons maintains a content directory wiki of organizations and projects using Creative Commons licenses.[88] On its website CC also provides case studies of projects using CC licenses across the world.[89] CC licensed content can also be accessed through a number of content directories and search engines (see Creative Commons-licensed content directories).

Unicode symbols

After being proposed by Creative Commons in 2017,[90] Creative Commons license symbols were added to Unicode with version 13.0 in 2020.[91] The circle with an equal sign (meaning no derivatives) is present in older versions of Unicode, unlike all the other symbols.

| Name | Unicode | Decimal | UTF-8 | Image | Displayed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circled Equals

meaning no derivatives |

U+229C | ⊜ | E2 8A 9C | ⊜ | |

| Circled Zero With Slash

meaning no rights reserved |

U+1F10D | 🄍 | F0 9F 84 8D | 🄍 | |

| Circled Anticlockwise Arrow

meaning share alike |

U+1F10E | 🄎 | F0 9F 84 8E | 🄎 | |

| Circled Dollar Sign With Overlaid Backslash

meaning non commercial |

U+1F10F | 🄏 | F0 9F 84 8F | 🄏 | |

| Circled CC

meaning Creative Commons license |

U+1F16D | 🅭 | F0 9F 85 AD | 🅭 | |

| Circled C With Overlaid Backslash

meaning public domain |

U+1F16E | 🅮 | F0 9F 85 AE | 🅮 | |

| Circled Human Figure

meaning attribution, credit |

U+1F16F | 🅯 | F0 9F 85 AF | 🅯 |

These symbols can be used in succession to indicate a particular Creative Commons license, for example, CC-BY-SA (CC-Attribution-ShareAlike) can be expressed with Unicode symbols CIRCLED CC, CIRCLED HUMAN FIGURE and CIRCLED ANTICLOCKWISE ARROW placed next to each other: 🅭🅯🄎

Case law database

In December 2020, the Creative Commons organization launched an online database covering licensing case law and legal scholarship.[92][93]

See also

- Free-culture movement

- Free music

- Free software

- Non-commercial educational

Notes

- A "work" is any creative material made by a person. A painting, a graphic, a book, a song/lyrics to a song, or a photograph of almost anything are all examples of "works".

References

- Shergill, Sanjeet (May 6, 2017). "The teacher's guide to Creative Commons licenses". Open Education Europa. Archived from the original on June 26, 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- "What are Creative Commons licenses?". Wageningen University & Research. June 16, 2015. Archived from the original on March 15, 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- "Creative Commons licenses". University of Michigan Library. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- "Creative Commons licenses" (PDF). University of Glasgow. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 15, 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- "The Creative Commons licenses". UNESCO. Archived from the original on March 15, 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- "License Versions - Creative Commons". wiki.creativecommons.org. Archived from the original on June 30, 2017. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- Open Definition 2.1 Archived January 27, 2017, at the Wayback Machine on opendefinition.org

- licenses Archived March 1, 2016, at the Wayback Machine on opendefinition.com

- Creative Commons 4.0 BY and BY-SA licenses approved conformant with the Open Definition Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine by Timothy Vollmer on creativecommons.org (December 27th, 2013)

- "Creative Commons Unveils Machine-Readable Copyright Licenses". December 16, 2002. Archived from the original on December 22, 2002.

- "1.1 The Story of Creative Commons | Creative Commons Certificate for Educators, Academic Librarians and GLAM". certificates.creativecommons.org. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- Murray, Laura J. (2014). Putting intellectual property in its place : rights discourses, creative labor, and the everyday. S. Tina Piper, Kirsty Robertson. Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-933626-5. OCLC 844373100.

- "Worldwide". Creative Commons. Archived from the original on October 15, 2008.

- Meng, Bingchun (January 26, 2009). "Articulating a Chinese Commons: An Explorative Study of Creative Commons in China". International Journal of Communication. 3: 16. ISSN 1932-8036.

- Hsia, Tao-tai; Haun, Kathryn (1973). "Laws of the People's Republic of China on Industrial and Intellectual Property". Law and Policy in International Business. 5 (3).

- Mueller, Milton (March 24, 2008). "View of Info-communism? Ownership and freedom in the digital economy | First Monday". First Monday. doi:10.5210/fm.v13i4.2058. hdl:10535/2829. S2CID 40724510. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- Till Kreutzer (2014). Open Content – A Practical Guide to Using Creative Commons Licenses (PDF). Wikimedia Deutschland e.a. ISBN 978-3-940785-57-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 4, 2015. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- Firer-Blaess, Sylvain; Fuchs, Christian (February 1, 2014). "Wikipedia: An Info-Communist Manifesto". Television & New Media. 15 (2): 87–103. doi:10.1177/1527476412450193. ISSN 1527-4764.

- "Creative Commons Legal Code". Creative Commons. January 9, 2008. Archived from the original on February 11, 2010. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- "Creative Commons FAQ: Can I use a Creative Commons license for software?". Wiki.creativecommons.org. July 29, 2013. Archived from the original on November 27, 2010. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- "Non-Software Licenses". Choose a License. Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- "AssaultCube - License". assault.cubers.net. Archived from the original on December 25, 2010. Retrieved January 30, 2011.

AssaultCube is FREEWARE. [...] The content, code and images of the AssaultCube website and all documentation are licensed under "Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported

- "Various Licenses and Comments about Them". GNU Project. Archived from the original on July 24, 2010. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- "Do Creative Commons licenses affect exceptions and limitations to copyright, such as fair dealing and fair use?". Frequently Asked Questions - Creative Commons. Archived from the original on August 8, 2015. Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- "What if I change my mind about using a CC license?". Frequently Asked Questions - Creative Commons. Archived from the original on August 8, 2015. Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- "What happens if the author decides to revoke the CC license to material I am using?". Frequently Asked Questions - Creative Commons. Archived from the original on August 8, 2015. Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- "How do CC licenses operate?". Frequently Asked Questions - Creative Commons. Archived from the original on August 8, 2015. Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- "Baseline Rights". Creative Commons. June 12, 2008. Archived from the original on February 8, 2010. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- "Frequently Asked Questions". Creative Commons. Creative Commons Corporation. August 28, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- "Creative Commons GNU LGPL". Archived from the original on June 22, 2009. Retrieved July 20, 2009.

- "Retired Legal Tools". Creative Commons. Archived from the original on May 3, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2012.

- "Announcing (and explaining) our new 2.0 licenses". Creativecommons.org. May 25, 2004. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- "About The Licenses - Creative Commons". Creative Commons. Archived from the original on July 26, 2015. Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- "Creative Commons — Attribution 3.0 United States". Creative Commons. November 16, 2009. Archived from the original on February 24, 2010. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- "CC0". Creative Commons. Archived from the original on February 26, 2010. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- "Downloads". Creative Commons. December 16, 2015. Archived from the original on December 25, 2015. Retrieved December 24, 2015.

- Dr. Till Kreutzer. "Validity of the Creative Commons Zero 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication and its usability for bibliographic metadata from the perspective of German Copyright Law" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- "Creative Commons Launches CC0 and CC+ Programs" (Press release). Creative Commons. December 17, 2007. Archived from the original on February 23, 2010. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- Baker, Gavin (January 16, 2009). "Report from CC board meeting". Open Access News. Archived from the original on September 19, 2010. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- "Expanding the Public Domain: Part Zero". Creativecommons.org. March 11, 2009. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- Christopher Allan Webber. "CC withdrawl [sic] of CC0 from OSI process". In the Open Source Initiative Licence review mailing list. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved February 24, 2012.

- "Marking and Tagging the Public Domain: An Invitation to Comment". Creativecommons.org. August 10, 2010. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- "Copyright-Only Dedication (based on United States law) or Public Domain Certification". Creative Commons. August 20, 2009. Archived from the original on February 23, 2010. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- Carl Boettiger. "OSI recognition for Creative Commons Zero License?". In the Open Source Initiative Licence review mailing list. opensource.org. Archived from the original on September 26, 2013. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- The Open Source Initiative FAQ. "What about the Creative Commons "CC0" ("CC Zero") public domain dedication? Is that Open Source?". opensource.org. Archived from the original on May 19, 2013. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

- "Unsplash is a site full of free images for your next splash page". The Next Web. August 14, 2013. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- "License | Unsplash". unsplash.com. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- "Why Building Something Useful For Others Is The Best Marketing There Is". Fast Company. February 18, 2015. Archived from the original on November 14, 2015. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- "Lawrence Lessig | Unsplash Book". book.unsplash.com. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- "Community update: Unsplash branded license and ToS changes". June 22, 2017. Archived from the original on January 7, 2018. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- Claburn, Thomas (July 25, 2022). "Fedora sours on CC 'No Rights Reserved' license". The Register. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- Lessig, Lawrence (June 4, 2007). "Retiring standalone DevNations and one Sampling license". Creative Commons. Archived from the original on July 7, 2007. Retrieved July 5, 2007.

- "Developing Nations License". Creative Commons. Archived from the original on April 12, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- "Sampling 1.0". Creative Commons. Archived from the original on March 16, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- "Sampling Plus 1.0". Creative Commons. November 13, 2009. Archived from the original on April 11, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- "NonCommercial Sampling Plus 1.0". Creative Commons. November 13, 2009. Archived from the original on March 25, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- Peters, Diane (November 25, 2013). "CC's Next Generation Licenses — Welcome Version 4.0!". Creative Commons. Archived from the original on November 26, 2013. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- "What's new in 4.0?". Creative Commons. 2013. Archived from the original on November 29, 2013. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- "CC 4.0, an end to porting Creative Commons licences?". TechnoLlama. September 25, 2011. Archived from the original on September 2, 2013. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- Doug Whitfield (August 5, 2013). "Music Manumit Lawcast with Jessica Coates of Creative Commons". YouTube. Archived from the original on August 14, 2013. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- "CC Affiliate Network". Creative Commons. Archived from the original on July 9, 2011. Retrieved July 8, 2011.

- "Frequently Asked Questions: What if CC licenses have not been ported to my jurisdiction?". Creative Commons. Archived from the original on November 27, 2013. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- "Frequently Frequently Asked Questions". Creative Commons. February 2, 2010. Archived from the original on February 26, 2010. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- "Defining Noncommercial report published". Creativecommons.org. September 14, 2009. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- "The Case for Free Use: Reasons Not to Use a Creative Commons -NC License". Freedomdefined.org. August 26, 2013. Archived from the original on June 25, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- "Frequently Asked Questions". CC Wiki. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- "Frequently Asked Questions". Creative Commons. July 14, 2016. Archived from the original on November 27, 2010. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- Creative Commons licenses without a non-commercial or no-derivatives requirement, including public domain/CC0, are all cross-compatible. Non-commercial licenses are compatible with each other and with less restrictive licenses, except for Attribution-ShareAlike. No-derivatives licenses are not compatible with any license, including themselves.

- Katz, Zachary (2005). "Pitfalls of Open Licensing: An Analysis of Creative Commons Licensing". IDEA: The Intellectual Property Law Review. 46 (3): 391.

- "Creative Commons Case Law". Archived from the original on September 1, 2011. Retrieved August 31, 2011.

- "Creative Commons license upheld by court". News.cnet.com. Archived from the original on October 25, 2012. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Rimmer, Matthew (January 2007). Digital Copyright and the Consumer Revolution: Hands Off My Ipod - Matthew Rimmer - Google Böcker. ISBN 9781847207142. Archived from the original on April 14, 2016. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- "Creative Commons License Upheld by Dutch Court". Groklaw. March 16, 2006. Archived from the original on May 5, 2010. Retrieved September 2, 2006.

- "Creative Commons Licenses Enforced in Dutch Court". March 16, 2006. Archived from the original on September 6, 2011. Retrieved August 31, 2011.

- Cohen, Noam. "Use My Photo? Not Without Permission". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 15, 2011. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

One moment, Alison Chang, a 15-year-old student from Dallas, is cheerfully goofing around at a local church-sponsored car wash, posing with a friend for a photo. Weeks later, that photo is posted online and catches the eye of an ad agency in Australia, and the altered image of Alison appears on a billboard in Adelaide as part of a Virgin Mobile advertising campaign.

- Evan Brown (January 22, 2009). "No personal jurisdiction over Australian defendant in Flickr right of publicity case". Internet Cases, a blog about law and technology. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved September 25, 2010.

- "Lawsuit Against Virgin Mobile and Creative Commons – FAQ". September 27, 2007. Archived from the original on September 7, 2011. Retrieved August 31, 2011.

- Mia Garlick (March 23, 2006). "Spanish Court Recognizes CC-Music". Creative Commons. Archived from the original on August 9, 2010. Retrieved September 25, 2010.

- "Sentencia nº 12/2006 Juzgado de lo Mercantil nº 5 de Madrid | Derecho de Internet" (in Spanish). Derecho-internet.org. Archived from the original on November 26, 2015. Retrieved December 24, 2015.

- Evan Brown (July 2, 2010). "New Copyright Lawsuit Involves Creative Commons". Internet Cases: A blog about law and technology. Archived from the original on June 21, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- CMLP Staff (August 5, 2010). "GateHouse Media v. That's Great News". Citizen Media Law Project. Archived from the original on May 2, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- "Memorandum Opinion" (PDF). United States District Court for the District of Columbia. August 18, 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2016. Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- Guadamuz, Andres (October 24, 2015). "US Court interprets copyleft clause in Creative Commons licenses". TechnoLlama. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- Michael W. Carroll. "Carrollogos: U.S. Court Correctly Interprets Creative Commons Licenses". Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- Luther, Jörg (July 2016). "Kleingedrucktes — Editorial" [Fine print — Editorial]. LinuxUser (in German) (7/2016). ISSN 1615-4444. Archived from the original on September 15, 2016. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- See also: "Abmahnung des Verbandes zum Schutz geistigen Eigentums im Internet (VSGE)" [Notice from the Association for the Protection of Intellectual Property in the Internet (VSGE)] (in German). Hannover, Germany: Feil Rechtsanwaltsgesellschaft. January 8, 2014. Archived from the original on September 14, 2016. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- "Creative Commons-Foto-Abmahnung: Rasch Rechtsanwälte setzen erfolgreich Gegenansprüche durch" [Creative Commons photo notice: Rasch attorneys successfully enforce counterclaims]. anwalt.de (in German). May 22, 2019. Archived from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- "Content Directories". creativecommons.org. Archived from the original on April 30, 2009. Retrieved April 24, 2009.

- "Case Studies". Creative Commons. Archived from the original on December 24, 2011. Retrieved December 20, 2011.

- "Proposal to add CC license symbols to UCS" (PDF). Unicode. July 24, 2017. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- Steuer, Eric (March 18, 2020). "The Unicode Standard Now Includes CC License Symbols". Creative Commons. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- Salazar, Krystle (December 3, 2020). "Explore the new CC legal database site!". Creative Commons. Mountain View, California, USA. Retrieved January 3, 2021.

- Creative Commons. "Creative Commons Legal Database". Creative Commons. Mountain View, California, USA. Retrieved January 3, 2021.

External links

- Official website

- Full selection of licenses

- Licenses. Overview of free licenses. freedomdefined.org

- WHAT IS CREATIVE COMMONS LICENSE. – THE COMPLETE DEFINITIVE GUIDE

- Web-friendly formatted summary of CC BY-SA 3.0