Deccan Plateau

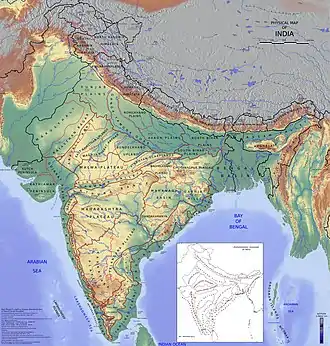

The Deccan Plateau is defined as the entire southern peninsula of India south of the Narmada River. It is a high triangular tableland, bounded on the west and east by the Western Ghats and the Eastern Ghats, respectively, that meet at the plateau’s southern tip and to the north, by the Satpura and Vindhya Ranges.

| Deccan Plateau | |

|---|---|

| Deccan | |

Southernmost part of Deccan plateau near the city of Tiruvannamalai, Tamil Nadu | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Anamudi, Eravikulam National Park |

| Elevation | 2,695 m (8,842 ft)[1] |

| Coordinates | 10°10′N 77°04′E |

| Naming | |

| Native name | Dakkhin (Kannada) |

A rocky terrain marked by boulders, its elevation ranges between 100 and 1,000 metres (330 and 3,280 ft), with an average of about 600 metres (2,000 ft).[2] It is sloping generally eastward. Thus, its principal rivers—the Godavari, Krishna, and Kaveri (Cauvery)—flow eastward from the Western Ghats to the Bay of Bengal. The plateau is drier than the coastal region of India and is arid in places.

It has been a region of conflict since early times. It produced some of the major dynasties in Indian history, including the Pallavas, Satavahana, Vakataka, Chalukya, and Rashtrakuta dynasties, also the Western Chalukya Empire, the Kadambas, the Yadava dynasty, the Kakatiya Empire, the Musunuri Nayakas regime, the Vijayanagara and the Maratha empires, as well as the Muslim Bahmani Sultanate, Deccan Sultanates, and the Nizam of Hyderabad. In attempting to conquer it in the 17th century, Aurangzeb fatally weakened the Moghul dynasty. In the late 18th century, the British defeated the French here.

Etymology

.jpg.webp)

The word Deccan is an anglicized version of the Kannada word dakkhaṇa,[3][4] with etymological roots in Sanskrit dakṣiṇa (दक्षिण), which means the "south".[2]

Extent

Geographers have variously defined the Deccan region using indices such as rainfall, vegetation, soil type, or physical features.[5] According to one geographical definition, it is the peninsular tableland lying to the south of the Tropic of Cancer. Its outer boundary is marked by the 300 m contour line, with Vindhya-Kaimur watersheds in the north. This area can be subdivided into two major geologic-physiographic regions: an igneous rock plateau with fertile black soil, and a gneiss peneplain with infertile red soil, interrupted by several hills.[6]

Historians have defined the term Deccan differently. These definitions range from a narrow one by R. G. Bhandarkar (1920), who defines Deccan as the Marathi speaking area lying between the Godavari and Krishna rivers, to a broad one by K. M. Panikkar (1969), who defines it as the entire Indian peninsula to the south of the Vindhyas.[7] Firishta (16th century) defined Deccan as the territory inhabited by the native speakers of Kannada, Marathi, and Telugu languages. Richard M. Eaton (2005) settles on this linguistic definition for a discussion of the region's geopolitical history.[5]

Stewart N. Gordon (1998) notes that historically, the term "Deccan" and the northern border of Deccan has varied from Tapti River in the north to Godavari River in the south, depending on the southern boundary of the northern empires. Therefore, while discussing the history of the Marathas, Gordon uses Deccan as a "relational term", defining it as "the area beyond the southern border of a northern-based kingdom" of India.[8]

Geography

The Deccan plateau is a topographically variegated region located south of the Gangetic plains -the portion lying between the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal- and includes a substantial area to the north of the Satpura Range, which has popularly been regarded as the divide between northern India and the Deccan. The plateau is bounded on the east and west by the Ghats, while its northern extremity is the Vindhya Range. The Deccan's average elevation is about 600 metres (2,000 ft), sloping generally eastward; its principal rivers, the Godavari, Krishna, and Kaveri, flow from the Western Ghats eastward to the Bay of Bengal. Tiruvannamalai in Tamil Nadu is often regarded as the Southern gateway of the Deccan plateau.

The Western Ghats mountain range is very massive and blocks the moisture from the southwest monsoon from reaching the Deccan Plateau, so the region receives very little rainfall.[9][10] The eastern Deccan Plateau is at a lower elevation spanning the southeastern coast of India. Its forests are also relatively dry but serve to retain the rain to form streams that feed into rivers that flow into basins and then into the Bay of Bengal.[11][12]

Most Deccan plateau rivers flow south. Most of the northern part of the plateau is drained by the Godavari River and its tributaries, including the Indravati River, starting from the Western Ghats and flowing east towards the Bay of Bengal. Most of the central plateau is drained by the Tungabhadra River, Krishna River and its tributaries, including the Bhima River, which also run east. The southernmost part of the plateau is drained by the Kaveri River, which rises in the Western Ghats of Karnataka and bends south to break through the Nilgiri Hills at the island town of Shivanasamudra and then falls into Tamil Nadu at Hogenakal Falls before flowing into the Stanley Reservoir and the Mettur Dam that created the reservoir, and finally emptying into the Bay of Bengal.[13]

On the western edge of the plateau lie the Sahyadri, the Nilgiri, the Anaimalai and the Elamalai Hills, commonly known as Western Ghats. The average height of the Western Ghats, which run along the Arabian Sea, goes on increasing towards the south. Anaimudi Peak in Kerala, with a height of 2,695 m above sea level, is the highest peak of peninsular India. In the Nilgiris lie Ootacamund, the well-known hill station of southern India. The western coastal plain is uneven and swift rivers flow through it that form beautiful lagoons and backwaters, examples of which can be found in the state of Kerala. The east coast is wide with deltas formed by the rivers Godavari, Mahanadi and Kaveri. Flanking the Indian peninsula on the western side are the Lakshadweep Islands in the Arabian Sea and on the eastern side lie the Andaman and Nicobar islands in the Bay of Bengal.

The eastern Deccan plateau, called Telangana and Rayalaseema, is made of vast sheets of massive granite rock, which effectively traps rainwater. Under the thin surface layer of soil is the impervious gray granite bedrock. It rains here only during some months.

Comprising the northeastern part of the Deccan Plateau, the Telangana Plateau has an area of about 148,000 km2, a north–south length of about 770 km, and an east–west width of about 515 km.

The plateau is drained by the Godavari River taking a southeasterly course; by the Krishna River, which divides the peneplain into two regions; and by the Pennai Aaru River flowing in a northerly direction. The plateau's forests are moist deciduous, dry deciduous, and tropical thorn.

Most of the population of the region is engaged in agriculture; cereals, oilseeds, cotton, and pulses (legumes) are the major crops. There are multipurpose irrigation and hydroelectric-power projects, including the Pochampad, Bhaira Vanitippa, and Upper Pennai Aaru. Industries (located in Hyderabad, Warangal, and Kurnool) produce cotton textiles, sugar, foodstuffs, tobacco, paper, machine tools, and pharmaceuticals. Cottage industries are forest-based (timber, firewood, charcoal, bamboo products) and mineral-based (asbestos, coal, chromite, iron ore, mica, and kyanite).

Having once constituted a segment of the ancient continent of Gondwanaland, this land is the oldest and most stable in India. The Deccan plateau consists of dry tropical forests that experience only seasonal rainfall.

The large cities in the Deccan are Bangalore, the capital of Karnataka; Hyderabad, the capital of Telangana; Pune, the cultural hub of Maharashtra; Nagpur, the second capital of Maharashtra and Nashik, the wine capital of Maharashtra. Other major cities include Hubli, Mysore, Gulbarga and Bellary in Karnataka; Aurangabad, Solapur, Amravati, Kolhapur, Akola, Latur, Sangli, Jalgaon, Nanded, Dhule, Chandrapur and Satara in Maharashtra; Hosur, Krishnagiri, Tiruvannamalai, Vellore and Ambur in Tamil Nadu; Amaravati, Visakhapatnam, Kurnool,Vijayawada, Guntur, Anantapur, Rajahmundry, Eluru, in Andhra Pradesh; and Warangal, Karimnagar, Ramagundam, Nizamabad, Suryapet, Siddipet, Nalgonda, Mahbubnagar in present-day Telangana and Jagdalpur, Bhawanipatna in the Northeastern part of the Deccan Plateau.

Climate

The climate of the region varies from semi-arid in the north to tropical in most of the region with distinct wet and dry seasons. Rayalaseema and Vidarbha are the driest regions. Rain falls during the monsoon season from about June to October. March to June can be very dry and hot, with temperatures regularly exceeding 35 °C.

The plateau's climate is drier than that on the coasts and is arid in places. Although sometimes used to mean all of India south of the Narmada River, the word Deccan relates more specifically to that area of rich volcanic soils and lava-covered plateaus in the northern part of the peninsula between the Narmada and Krishna rivers.

Deccan Traps

The northwestern part of the Deccan Plateau, a Precambrian shield, is partially covered by the Deccan Traps, a large igneous province made up of lava flows or igneous rocks known as the Deccan Traps. The rocks are spread over the whole of Maharashtra, thereby making it one of the largest volcanic provinces in the world. It consists of more than 2,000 metres (7,000 ft) of flat-lying basalt lava flows and covers an area of nearly 500,000 km2 (190,000 sq mi) in west-central India. Estimates of the original area covered by the lava flows are as high as 1,500,000 km2 (580,000 sq mi). The volume of basalt is estimated to be 511,000 km3. The thick dark soil (called silt) found here is suitable for cotton cultivation.

Geology

Typically the Deccan Plateau is made up of basalt, an extrusive igneous rock, extending up to Bhor Ghat near Karjat. Also in certain sections of the region we can find granite, which is an intrusive igneous rock.

The difference between these two rock types is that basalt rock forms on eruption of lava, that is, on the surface (either out of a volcano, or through massive fissures—as in the Deccan basalts—in the ground), while granite forms deep within the Earth. Granite is a felsic rock, meaning it is rich in potassium feldspar and quartz. This composition is continental in origin (meaning it is the primary composition of the continental crust). Since it cooled relatively slowly, it has large visible crystals.

Basalt, on the other hand, is mafic in composition—meaning it is rich in pyroxene and, in some cases, olivine, both of which are Mg-Fe rich minerals. Basalt is similar in composition to mantle rocks, indicating that it came from the mantle and did not mix with continental rocks. Basalt forms in areas that are spreading, whereas granite forms mostly in areas that are colliding. Since both rocks are found in the Deccan Plateau, it indicates two different environments of formation.

The volcanic basalt beds of the Deccan were laid down in the massive Deccan Traps eruption, which occurred towards the end of the Cretaceous period between 67 and 66 million years ago. Some paleontologists speculate that this eruption may have been one of the causes of the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event. Layer after layer was formed by the volcanic activity that lasted many thousands of years, and when the volcanoes became extinct, they left a region of highlands with typically vast stretches of flat areas on top like a table. The volcanic hotspot that produced the Deccan traps is hypothesized to lie under the present day island of Réunion in the Indian Ocean.[14]

The Deccan is rich in minerals. Primary mineral ores found in this region are mica and iron ore in the Chhota Nagpur region, and diamonds, gold and other metals in the Golconda region.

Fauna

The large areas of remaining forest on the plateau are still home to a variety of grazing animals from the four-horned antelope (tetracerus quadricornis),[13] chinkara (Gazella bennettii),[13] and blackbuck (Antilope cervicapra) to the gaur (Bos gaurus; /ɡaʊər/) and wild water buffalo (Bubalus arnee).

People

The Deccan is home to many languages and people. Bhil and Gond people live in the hills along the northern and northeastern edges of the plateau and speak various languages that belong to both the Indo-Aryan and Dravidian families of languages. Marathi, an Indo-Aryan language, is the main language of the north-western Deccan in the state of Maharashtra. Speakers of the Dravidian languages Telugu and Kannada, the predominant languages of Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, and Karnataka respectively, occupy those states' portions of the plateau. The city of Hyderabad is an important center of the Urdu language in the Deccan; its surrounding areas also host a notable population of Urdu speakers. The Urdu dialect spoken in this region is also known as Dakhini or as Deccani, named after the region itself. Tamil is spoken in the southernmost parts of the Deccan, in the areas occupied by the state of Tamil Nadu. Northeastern parts of the Deccan are in the state of Odisha. Odia, another Indo-Aryan language, is spoken in this part of Deccan.

The chief crop is cotton; also common are sugarcane, rice, and other crops.

History

The Deccan produced some of the most significant dynasties in Indian history, such as the Vijayanagara Empire, the Rashtrakuta dynasty, the Chola dynasty, the Thagadur dynasty, Adhiyamans Pallavas, the Tondaiman, Satavahana dynasty, Vakataka dynasty, Kadamba dynasty, Chalukya dynasty, Yadava dynasty, Kakatiya Dynasty, Western Chalukya Empire and Maratha Empire.

Of the early history, the main facts established are the growth of the Mauryan empire (300 BCE) and after that the Deccan was ruled by the Satavahana dynasty, which protected the Deccan against the Scythian invaders, the Western Satraps.[15] Prominent dynasties of this time include the Cholas (3rd century BCE to 12th century CE), Chalukyas (6th to 12th centuries), Rashtrakutas (753–982), Yadavas (9th to 14th centuries), Hoysalas (10th to 14th centuries), Kakatiya (1083 to 1323 CE) and Vijayanagara Empire (1336–1646).

Ahir Kings once ruled over the Deccan. A cave inscription at Nasik refers to the reign of an Abhira prince named Ishwarsena, son of Shivadatta.[16] After the collapse of the Satavahana dynasty, the Deccan was ruled by the Vakataka dynasty from the third century to fifth century.

From the sixth to eighth century the Deccan was ruled by the Chalukya dynasty which produced great rulers such as Pulakesi II, who defeated the north India Emperor Harsha, and Vikramaditya II, whose general defeated the Arab invaders in the eighth century.

From the eighth to tenth century the Rashtrakuta dynasty ruled this region. It led successful military campaigns into northern India and was described by Arab scholars as one of the four great empires of the world.[17]

In the tenth century the Western Chalukya Empire, which produced scholars such as the social reformer Basavanna, Vijñāneśvara, the mathematician Bhāskara II, and Someshwara III, who wrote the text Manasollasa, was established.

From the early 11th century to the 12th century the Deccan Plateau was dominated by the Western Chalukya Empire and the Chola dynasty.[18] Several battles were fought between the Western Chalukya Empire and the Chola dynasty in the Deccan Plateau during the reigns of Raja Raja Chola I, Rajendra Chola I, Jayasimha II, Someshvara I and Vikramaditya VI and Kulottunga I.[19]

In 1294, Alauddin Khalji, emperor of Delhi, invaded the Deccan, stormed Devagiri, and reduced the Yadava rajas of Maharashtra to the position of tributary princes (see Daulatabad), then proceeded southward to conquer the Orugallu, Carnatic. In 1307, a fresh series of incursions led by Malik Kafur began in response to unpaid tributes, resulting in the final ruin of the Yadava clan; and in 1338 the conquest of the Deccan was completed by Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq.

The imperial hegemony was brief, as soon the earlier kingdoms reverted to their former masters. These defections by the states were soon followed by a general revolt of the foreign governors, resulting in the establishment in 1347 of the independent Bahmani dynasty.[20] The power of the Delhi sultanate evaporated south of the Narmada River. The southern Deccan came under the rule of the famous Vijayanagara Empire, which reached its zenith during the reign of Emperor Krishnadevaraya.[21]

In the power struggles which ensued, the Hindu kingdom of Karnataka fell bit by bit to the Bahamani dynasty, who advanced their frontier to Golkonda in 1373, to Warangal in 1421, and to the Bay of Bengal in 1472. Krishnadevaraya of the Vijayanagara Empire defeated the last remnant of Bahmani Sultanate power after which the Bahmani Sultanate collapsed.[22] When the Bahmani empire dissolved in 1518, its dominions were distributed into the five Muslim states of Golkonda, Bijapur, Ahmednagar, Bidar and Berar, giving rise to the Deccan sultanates.[20]

South of these, the Hindu state of Carnatic or Vijayanagar still survived; but this, too, was defeated, at the Battle of Talikota (1565) by a league of the Muslim powers. Berar had already been annexed by Ahmednagar in 1572, and Bidar was absorbed by Bijapur in 1619. Mughal interest in the Deccan also rose at this time. Partially incorporated into the Empire in 1598, Ahmadnagar was fully annexed in 1636; Bijapur in 1686, and Golkonda in 1687.

In 1645, Shivaji laid the foundation of the Maratha Empire. The Marathas under Shivaji directly challenged the Bijapur Sultanate and ultimately the mighty Mughal empire. Once the Bijapur Sultanate stopped being a threat to the Maratha Empire, Marathas became much more aggressive and began to frequently raid Mughal territory. These raids, however, angered the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb and by 1680 he moved his capital from Delhi to Aurangabad in Deccan to conquer Maratha-held territories. After Shivaji died, his son Sambhaji defended the Maratha empire from the Mughal onslaught but was captured by the Mughals and executed. By 1698 the last Maratha stronghold at Jinji fell and Mughals then controlled all Maratha held territories.

In 1707, Emperor Aurangzeb died at the age of 89, which allowed the Marathas to reacquire lost territories and establish authority in much of modern Maharashtra. After the death of Chhatrapati Shahu, the Peshwas became the de facto leaders of the Empire from 1749 to 1761, while Shivaji's successors continued as nominal rulers from their base in Satara. The Marathas kept the British at bay during the 18th century.

By 1760, with the defeat of the Nizam in the Deccan, Maratha power had reached its zenith. However, dissension between the Peshwa and their sardars (army commanders) saw a gradual downfall of the empire leading to its eventual annexation by the British East India Company in 1818 after the three Anglo-Maratha wars.

A few years later, Aurangzeb's viceroy in Ahmednagar, Nizam-ul-Mulk, established the seat of an independent government at Hyderabad in 1724. Mysore was ruled by Hyder Ali. During the contests for power which ensued from about the middle of the 18th century between the powers on the plateau, the French and British took opposite sides. After a brief series of victories, the interests of France declined, and a new empire in India was established by the British. Mysore formed one of their earliest conquests in the Deccan. Tanjore and the Carnatic were soon annexed to their dominions, followed by the Peshwa territories in 1818.

In British India, the plateau was largely divided between the presidencies of Bombay and Madras. The two largest native states at that time were Hyderabad and Mysore; many smaller states existed at the time, including Kolhapur, and Sawantwari.

After independence in 1947, almost all native states were incorporated into the Republic of India. The Indian Army annexed Hyderabad in Operation Polo in 1948 when it refused to join.[23] In 1956, the States Reorganisation Act reorganized states along linguistic lines, leading to the states currently found on the plateau.

Economy

The Deccan plateau is very rich in minerals and precious stones.[24] The plateau's mineral wealth led many lowland rulers, including those of the Mauryan (4th–2nd century BCE) and Gupta (4th–6th century CE) dynasties, to fight over it.[25] Major minerals found here include coal, iron ore, asbestos, chromite, mica, and kyanite. Since March 2011, large deposits of uranium have been discovered in the Tummalapalle belt and in the Bhima basin at Gogi in Karnataka. The Tummalapalle belt uranium reserve promises to be one of the top 20 uranium reserve discoveries of the world.[26][27][28]

Low rainfall made farming difficult until the introduction of irrigation. Currently, the area under cultivation is quite low, ranging from 60% in Maharashtra to about 10% in Western Ghats.[29] Except in developed areas of certain river valleys, double-cropping is rare. Rice is the predominant crop in high-rainfall areas and sorghum in low-rainfall areas. Other crops of significance include cotton, tobacco, oilseeds, and sugar cane. Coffee, tea, coconuts, areca, black pepper, rubber, cashew nuts, cassava, and cardamom are widely grown on plantations in the Nilgiri Hills and on the western slopes of the Western Ghats. Cultivation of Jatropha has recently received more attention due to the Jatropha incentives in India.

References

- "The Deccan". Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica (2014), Deccan plateau India, Encyclopaedia Britannica

- Henry Yule, A. C. Burnell (13 June 2013). Hobson-Jobson: The Definitive Glossary of British India. Oxford. ISBN 9780191645839.

- Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary, p. 498 (scanned image at SriPedia Initiative): Sanskrit dakṣiṇa meaning 'southern'.

- Richard M. Eaton 2005, p. 2.

- S. M. Alam 2011, p. 311.

- S. M. Alam 2011, p. 312.

- Stewart Gordon (1993). The Marathas 1600-1818. The New Cambridge History of India. Cambridge University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-521-26883-7.

- World Wildlife Fund, ed. (2001). "South Deccan Plateau dry deciduous forests". WildWorld Ecoregion Profile. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 8 March 2010. Retrieved 5 January 2007.

- "South Deccan Plateau dry deciduous forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 5 January 2007.

- "The Deccan Peninsula". sanctuaryasia. Archived from the original on 17 October 2006. Retrieved 5 January 2007.

- "Eastern Deccan Plateau Moist Forests". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 5 January 2007.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 375–421.

- "Deccan | plateau, India". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- History of Asia by B.V. Rao p.288

- The Castes and Tribes of H.E.H. the Nizam's Dominions, Volume 1, by Syed Siraj ul Hassan-page-12

- Portraits of a Nation: History of Ancient India by kamlesh kapur p.584-585

- The Penguin History of Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300 by Romila Thapar: p.365-366

- Ancient Indian History and Civilization by Sailendra Nath Sen: p.383-384

- Marshall Cavendish Corporation (2008). India and Its Neighbors, Part 1, p. 335. Tarreytown, New York: Marshall Cavendish Corporation.

- Richard M. Eaton 2005, p. 83.

- Richard M. Eaton 2005, p. 88.

- Benichou, Lucien D. (2000). From Autocracy to Integration: Political Developments in Hyderabad State (1938–1948), p. 232. Chennai: Orient Longman Limited.

- Ottens, Berthold (1 January 2003). "Minerals of the Deccan Traps, India". HighBeam Research. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- Deccan Plateau, India. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- Subramanian, T. S. (20 March 2011). "Massive uranium deposits found in Andhra Pradesh". news. Chennai, India: The Hindu. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- Thakur, Monami (19 July 2011). "Massive uranium deposits found in Andhra Pradesh". International Business Times. USA.

- Bedi, Rahul (19 July 2011). "Largest uranium reserves found in India". The Telegraph. New Delhi, India. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- "Peninsular India". ita. September 1995. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

Bibliography

- Richard M. Eaton (2005). A Social History of the Deccan, 1300–1761. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521254847.

- Shah Manzoor Alam (2011). "The Historic Deccan - A Geographical Appraisal". In Kalpana Markandey; Geeta Reddy Anant (eds.). Urban Growth Theories and Settlement Systems of India. Concept. ISBN 978-81-8069-739-5.

External links

Media related to Deccan Plateau at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Deccan Plateau at Wikimedia Commons- Dynasties of Deccan