Hindu temple

A Hindu temple, or mandir or koil in Indian languages,[lower-alpha 1] is a house, seat and body of divinity for Hindus. It is a structure designed to bring human beings and gods together through worship, sacrifice, and devotion.[3][4] The symbolism and structure of a Hindu temple are rooted in Vedic traditions, deploying circles and squares.[5] It also represents recursion and the representation of the equivalence of the macrocosm and the microcosm by astronomical numbers, and by "specific alignments related to the geography of the place and the presumed linkages of the deity and the patron".[6][7] A temple incorporates all elements of the Hindu cosmos — presenting the good, the evil and the human, as well as the elements of the Hindu sense of cyclic time and the essence of life — symbolically presenting dharma, artha, kama, moksa, and karma.[8][9][10]

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

|

The spiritual principles symbolically represented in Hindu temples are given in the ancient Sanskrit texts of India (for example, the Vedas and Upanishads), while their structural rules are described in various ancient Sanskrit treatises on architecture (Bṛhat Saṃhitā, Vāstu Śāstras).[11][12] The layout, the motifs, the plan and the building process recite ancient rituals, geometric symbolisms, and reflect beliefs and values innate within various schools of Hinduism.[5] A Hindu temple is a spiritual destination for many Hindus, as well as landmarks around which ancient arts, community celebrations and economy have flourished.[13][14]

Hindu temples come in many styles, are situated in diverse locations, deploy different construction methods and are adapted to different deities and regional beliefs,[15] yet almost all of them share certain core ideas, symbolism and themes. They are found in South Asia, particularly India and Nepal, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, in Southeast Asian countries such as Cambodia, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Island of Indonesia,[16][17] and countries such as Canada, Fiji, France, Guyana, Kenya, Mauritius, the Netherlands, South Africa, Suriname, Tanzania, Trinidad and Tobago, Uganda, the United Kingdom, the United States, and other countries with a significant Hindu population.[18] The current state and outer appearance of Hindu temples reflect arts, materials and designs as they evolved over two millennia; they also reflect the effect of conflicts between Hinduism and Islam since the 12th century.[19] The Swaminarayanan Akshardham in Robbinsville, New Jersey, United States, between the New York and Philadelphia metropolitan areas, was inaugurated in 2014 as one of the world's largest Hindu temples.[20]

Significance and meaning of a temple

A Hindu temple reflects a synthesis of arts, the ideals of dharma, beliefs, values and the way of life cherished under Hinduism. It is a link between man, deities, and the Universal Puruṣa in a sacred space.[21] It represents the triple-knowledge (trayi-vidya) of the Vedic vision by mapping the relationships between the cosmos (brahmaṇḍa) and the cell (pinda) by a unique plan based on astronomical numbers.[22] Subhash Kak sees the temple form and its iconography to be a natural expansion of Vedic ideology related to recursion, change and equivalence.[23]

In ancient Indian texts, a temple is a place of pilgrimage, known in India as a Tirtha.[5] It is a sacred site whose ambience and design attempts to symbolically condense the ideal tenets of the Hindu way of life.[21] All the cosmic elements that create and sustain life are present in a Hindu temple – from fire to water, from images of nature to deities, from the feminine to the masculine, from the fleeting sounds and incense smells to the eternality and universality at the core of the temple.

Susan Lewandowski states[11] that the underlying principle in a Hindu temple is the belief that all things are one, that everything is connected. The pilgrim is welcomed through 64-grid or 81-grid mathematically structured spaces, a network of art, pillars with carvings and statues that display and celebrate the four important and necessary principles of human life – the pursuit of artha (prosperity, wealth), of kama (pleasure, sex), of dharma (virtues, ethical life) and of moksha (release, self-knowledge).[24][25] At the centre of the temple, typically below and sometimes above or next to the deity, is mere hollow space with no decoration, symbolically representing Purusa, the Supreme Principle, the sacred Universal, one without form, which is present everywhere, connects everything, and is the essence of everyone. A Hindu temple is meant to encourage reflection, facilitate purification of one's mind, and trigger the process of inner realization within the devotee.[5] The specific process is left to the devotee's school of belief. The primary deity of different Hindu temples varies to reflect this spiritual spectrum.[26][27]

In Hindu tradition, there is no dividing line between the secular and the lonely sacred.[11] In the same spirit, Hindu temples are not just sacred spaces; they are also secular spaces. Their meaning and purpose have extended beyond spiritual life to social rituals and daily life, offering thus a social meaning. Some temples have served as a venue to mark festivals, to celebrate arts through dance and music, to get married or commemorate marriages,[28] the birth of a child, other significant life events or the death of a loved one. In political and economic life, Hindu temples have served as a venue for succession within dynasties and landmarks around which economic activity thrived.[29]

Forms and designs of Hindu temples

Almost all Hindu temples take two forms: a house or a palace. A house-themed temple is a simple shelter which serves as a deity's home. The temple is a place where the devotee visits, just like he or she would visit a friend or relative. The use of moveable and immoveable images is mentioned by Pāṇini. In Bhakti school of Hinduism, temples are venues for puja, which is a hospitality ritual, where the deity is honored, and where devotee calls upon, attends to and connects with the deity. In other schools of Hinduism, the person may simply perform jap, or meditation, or yoga, or introspection in his or her temple. Palace-themed temples often incorporate more elaborate and monumental architecture.[30]

Site

The appropriate site for a temple, suggest ancient Sanskrit texts, is near water and gardens, where lotus and flowers bloom, where swans, ducks and other birds are heard, where animals rest without fear of injury or harm.[5] These harmonious places were recommended in these texts with the explanation that such are the places where gods play, and thus the best site for Hindu temples.[5][11]

The gods always play where lakes are,

where the sun's rays are warded off by umbrellas of lotus leaf clusters,

and where clear waterpaths are made by swans

whose breasts toss the white lotus hither and thither,

where swans, ducks, curleys and paddy birds are heard,

and animals rest nearby in the shade of Nicula trees on the river banks.

The gods always play where rivers have for their braclets

the sound of curleys and the voice of swans for their speech,

water as their garment, carps for their zone,

the flowering trees on their banks as earrings,

the confluence of rivers as their hips,

raised sand banks as breasts and plumage of swans their mantle.

The gods always play where groves are near, rivers, mountains and springs, and in towns with pleasure gardens.— Varāhamihira, Brhat Samhita 1.60.4-8, 6th century CE[31]

While major Hindu temples are recommended at sangams (confluence of rivers), river banks, lakes and seashore, Brhat Samhita and Puranas suggest temples may also be built where a natural source of water is not present. Here too, they recommend that a pond be built preferably in front or to the left of the temple with water gardens. If water is neither present naturally nor by design, water is symbolically present at the consecration of temple or the deity. Temples may also be built, suggests Visnudharmottara in Part III of Chapter 93,[32] inside caves and carved stones, on hill tops affording peaceful views, mountain slopes overlooking beautiful valleys, inside forests and hermitages, next to gardens, or at the head of a town street.

Manuals

Ancient builders of Hindu temples created manuals of architecture, called Vastu-Sastra (literally "science" of dwelling; vas-tu is a composite Sanskrit word; vas means "reside", tu means "you"); these contain Vastu-Vidya (literally, knowledge of dwelling)[33] and Sastra meaning system or knowledge in Sanskrit. There exist many Vastu-Sastras on the art of building temples, such as one by Thakkura Pheru, describing where and how temples should be built.[34][35] By the 6th century CE, Sanskrit manuals for in India.[36] Vastu-Sastra manuals included chapters on home construction, town planning,[33] and how efficient villages, towns and kingdoms integrated temples, water bodies and gardens within them to achieve harmony with nature.[37][38] While it is unclear, states Barnett,[39] as to whether these temple and town planning texts were theoretical studies and if or when they were properly implemented in practice, the manuals suggest that town planning and Hindu temples were conceived as ideals of art and integral part of Hindu social and spiritual life.[33]

The Silpa Prakasa of Odisha, authored by Ramacandra Bhattaraka Kaulacara in the 9th or 10th centuries CE, is another Sanskrit treatise on Temple Architecture.[41] Silpa Prakasa describes the geometric principles in every aspect of the temple and symbolism such as 16 emotions of human beings carved as 16 types of female figures. These styles were perfected in Hindu temples prevalent in eastern states of India. Other ancient texts found expand these architectural principles, suggesting that different parts of India developed, invented and added their own interpretations. For example, in Saurastra tradition of temple building found in western states of India, the feminine form, expressions and emotions are depicted in 32 types of Nataka-stri compared to 16 types described in Silpa Prakasa.[41] Silpa Prakasa provides brief introduction to 12 types of Hindu temples. Other texts, such as Pancaratra Prasada Prasadhana compiled by Daniel Smith[42] and Silpa Ratnakara compiled by Narmada Sankara[43] provide a more extensive list of Hindu temple types.

Ancient Sanskrit manuals for temple construction discovered in Rajasthan, in northwestern region of India, include Sutradhara Mandana's Prasadamandana (literally, manual for planning and building a temple).[44] Manasara, a text of South Indian origin, estimated to be in circulation by the 7th century CE, is a guidebook on South Indian temple design and construction.[11][45] Isanasivagurudeva paddhati is another Sanskrit text from the 9th century describing the art of temple building in India in south and central India.[46][47] In north India, Brihat-samhita by Varāhamihira is the widely cited ancient Sanskrit manual from 6th century describing the design and construction of Nagara style of Hindu temples.[40][48][49]

The plan

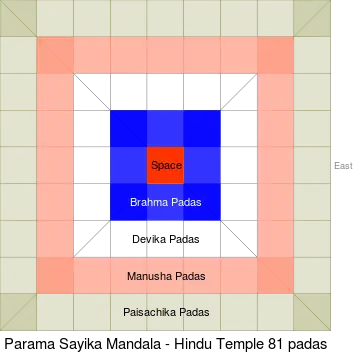

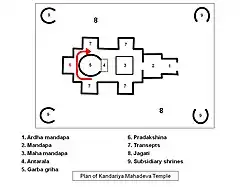

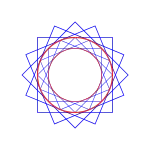

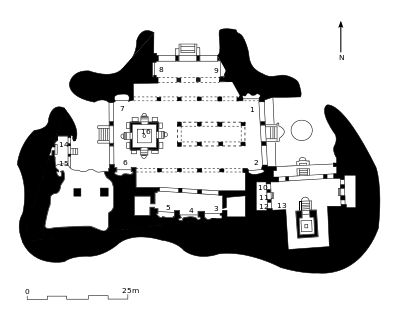

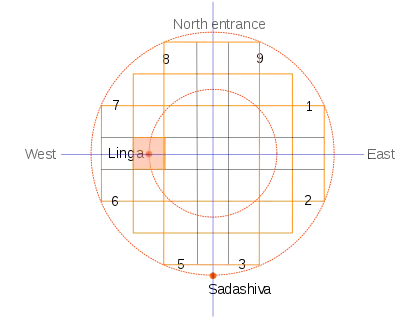

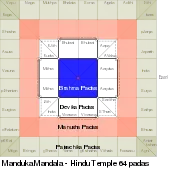

A Hindu temple design follows a geometrical design called vastu-purusha-mandala. The name is a composite Sanskrit word with three of the most important components of the plan. Mandala means circle, Purusha is universal essence at the core of Hindu tradition, while Vastu means the dwelling structure.[50] The Vastu-purusha-mandala is a yantra,[34] a design laying out a Hindu temple in a symmetrical, self-repeating structure derived from central beliefs, myths, cardinality and mathematical principles.

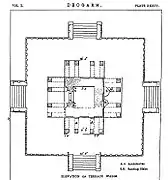

The four cardinal directions help create the axis of a Hindu temple, around which is formed a perfect square in the space available. The circle of the mandala circumscribes the square. The square is considered divine for its perfection and as a symbolic product of knowledge and human thought, while the circle is considered earthly, human and observed in everyday life (moon, sun, horizon, water drop, rainbow). Each supports the other.[5] The square is divided into perfect 64 (or in some cases 81) sub-squares called padas.[40][51] Each pada is conceptually assigned to a symbolic element, sometimes in the form of a deity. The central square(s) of the 64- or 81-grid is dedicated to Brahman (not to be confused with brahmin, the scholarly and priestly class in India), and are called Brahma padas.

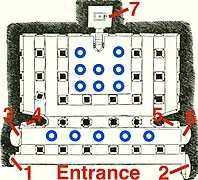

The 49-grid design is called Sthandila and is of great importance in creative expressions of Hindu temples in South India, particularly in Prakaras.[52] The symmetric Vastu-purusa-mandala grids are sometimes combined to form a temple superstructure with two or more attached squares.[53] The temples face sunrise, and the entrance for the devotee is typically this east side. The mandala pada facing sunrise is dedicated to Surya, the sun-god. The Surya pada is flanked by the padas of Satya, the deity of Truth, on one side and Indra, the king of the demigods, on other. The east and north faces of most temples feature a mix of gods and demigods; while the west and south feature demons and demigods related to the underworld.[54] This vastu-purusha-mandala plan and symbolism is systematically seen in ancient Hindu temples on the Indian subcontinent as well as those in southeast Asia, with regional creativity and variations.[55][56]

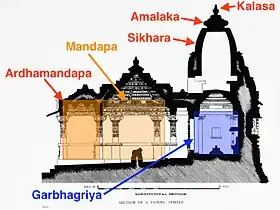

Beneath the mandala's central square(s) is the space for the all-pervasive, all-connecting Universal Spirit, the highest reality, the purusha.[57] This space is sometimes known as the garbha-griya (literally, “womb house”) – a small, perfect square, windowless, enclosed space without ornamentation that represents universal essence.[50] In or near this space is typically a cult image — which, though many Indians may refer to casually as an idol, is more formally known as a murti, or the main worshippable deity, who varies with each temple. Often this murti gives the temple a local name, such as a Visnu temple, Krishna temple, Rama temple, Narayana temple, Siva temple, Lakshmi temple, Ganesha temple, Durga temple, Hanuman temple, Surya temple, etc.[21] It is this garbha-griya which devotees seek for darsana (literally, a sight of knowledge,[58] or vision[50]).

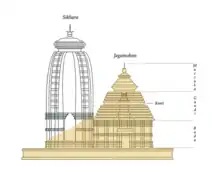

Above the vastu-purusha-mandala is a superstructure with a dome called Shikhara in north India, and Vimana in south India, that stretches towards the sky.[50] Sometimes, in makeshift temples, the dome may be replaced with symbolic bamboo with few leaves at the top. The vertical dimension's cupola or dome is designed as a pyramid, a cone or other mountain-like shape, once again using the principle of concentric circles and squares.[5] Scholars suggest that this shape is inspired by the cosmic mountain of Meru or Himalayan Kailasa, the abode of the gods, according to Vedic mythology.[50]

In larger temples, the central space typically is surrounded by an ambulatory for the devotee to walk around and ritually circumambulate the Purusa, the universal essence.[5] Often this space is visually decorated with carvings, paintings or images meant to inspire the devotee. In some temples, these images may be stories from Hindu Epics; in others, they may be Vedic tales about right and wrong or virtues and vice; in yet others, they may be murtis of locally worshipped deities. The pillars, walls and ceilings typically also have highly ornate carvings or images of the four just and necessary pursuits of life – kama, artha, dharma and moksa. This walk around is called pradakshina.[50]

Large temples also have pillared halls, called mandapa — one of which, on the east side, serves as the waiting room for pilgrims and devotees. The mandapa may be a separate structure in older temples, but in newer temples this space is integrated into the temple superstructure. Mega-temple sites have a main temple surrounded by smaller temples and shrines, but these are still arranged by principles of symmetry, grids and mathematical precision. An important principle found in the layout of Hindu temples is mirroring and repeating fractal-like design structure,[60] each unique yet also repeating the central common principle, one which Susan Lewandowski refers to as "an organism of repeating cells".[29]

The ancient texts on Hindu temple design, the Vāstu-puruṣa-mandala and Vastu Śāstras, do not limit themselves to the design of a Hindu temple.[61] They describe the temple as a holistic part of its community, and lay out various principles and a diversity of alternate designs for home, village and city layout along with the temple, gardens, water bodies and nature.[5][37]

- Exceptions to the square grid principle

A predominant number of Hindu temples exhibit the perfect-square grid principle.[62] However, there are some exceptions. For example, the Telika Mandir in Gwalior, built in the 8th century CE, is not a square but a rectangle in 2:3 proportion. Further, the temple explores a number of structures and shrines in 1:1, 1:2, 1:3, 2:5, 3:5 and 4:5 ratios. These ratios are exact, suggesting that the architect intended to use these harmonic ratios, and the rectangle pattern was not a mistake, nor an arbitrary approximation. Other examples of non-square harmonic ratios are found at the Naresar temple site of Madhya Pradesh and at the Nakti-Mata temple near Jaipur, Rajasthan. Michael Meister suggests that these exceptions mean that the ancient Sanskrit manuals for temple building were guidelines, and Hinduism permitted its artisans flexibility in expression and aesthetic independence.[40]

The symbolism

A Hindu temple is a symbolic reconstruction of the universe and the universal principles that enable everything in it to function.[63][64] The temples reflect Hindu philosophy and its diverse views on the cosmos and on truth.[60][65]

Hinduism has no traditional ecclesiastical order, no centralized religious authorities, no governing body, no prophet nor any binding holy book save the Vedas; Hindus can choose to be polytheistic, pantheistic, monistic, or atheistic.[66] Within this diffuse and open structure, spirituality in Hindu philosophy is an individual experience, and referred to as kṣaitrajña (Sanskrit: क्षैत्रज्ञ)[67]). It defines spiritual practice as one's journey towards moksha, awareness of self, the discovery of higher truths, true nature of reality, and a consciousness that is liberated and content.[68][69] A Hindu temple reflects these core beliefs. The central core of almost all Hindu temples is not a large communal space; the temple is designed for the individual, a couple or a family – a small, private space to allow visitors to experience darsana.

Darsana is itself a symbolic word. In ancient Hindu scripts, darsana is the name of six methods or alternate viewpoints of understanding truth.[70] These are Nyaya, Vaisesika, Sankhya, Yoga, Mimamsa and Vedanta – which flowered into individual schools of Hinduism, each of which is considered a valid, alternate path to understanding truth and achieving self-realization in the Hindu way of life.

From names to forms, from images to stories carved into the walls of a temple, symbolism is everywhere in a Hindu temple. Life principles such as the pursuit of joy, connection and emotional pleasure (kama) are fused into mystical, erotic and architectural forms in Hindu temples. These motifs and principles of human life are part of the sacred texts of the Hindus, such as its Upanishads; the temples express these same principles in a different form, through art and spaces. For example, Brihadaranyaka Upanisad (4.3.21) recites:

In the embrace of the beloved, one forgets the whole world, everything both within and without;

in the same way, one who embraces the Self knows neither within nor without.— Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, 7th century BCE[71]

The architecture of Hindu temples is also symbolic. The whole structure fuses the daily life and its surroundings with the divine concepts, through a structure that is open yet raised on a terrace, transitioning from the secular towards the sacred,[72] inviting the visitor inwards and upwards towards the Brahma pada, the temple's central core, a symbolic space marked by its spire (shikhara, vimana). The ancient temples had grand, intricately carved entrances but no doors, and they lacked a boundary wall. In most cultures, suggests Edmund Leach,[72] a boundary and gateway separates the secular and the sacred, and this gateway door is grand. In Hindu tradition, this is discarded in favor of an open and diffusive architecture, where the secular world was not separated from the sacred, but transitioned and flowed into the sacred.[73] The Hindu temple has structural walls, which were patterned usually within the 64-grid, or other geometric layouts. Yet the layout was open on all sides, except for the core space with a single opening for darsana. The temple space is laid out in a series of courts (mandapas). The outermost regions may incorporate the negative and suffering side of life with the symbolism of evil, asuras and rakshashas; but in small temples this layer is dispensed with. When present, this outer region diffuse into the next inner layer that bridges as human space, followed by another inner Devika padas space and symbolic arts incorporating the positive and joyful side of life about the good and the gods. This divine space then concentrically diffuses inwards and lifts the guest to the core of the temple, where resides the main murti, as well as the space for the Purusa, and ideas held to be most sacred principles in Hindu tradition. The symbolism in the arts and temples of Hinduism, suggests Edmund Leach, is similar to those in Christianity and other major religions of the world.[74]

The teams that built Hindu temples

Indian texts call the craftsmen and builders of temples as ‘‘Silpin’’ (Sanskrit: शिल्पिन्[75]), derived from ‘‘Silpa’’.[76] One of earliest mentions of Sanskrit word Silpa is in Atharvaveda, from about 1000 BCE, which scholars have translated as any work of art.[77] Other scholars suggest that the word Silpa has no direct one word translation in English, nor does the word ‘‘Silpin’’. Silpa, explains Stella Kramrisch,[46] is a multicolored word and incorporates art, skill, craft, ingenuity, imagination, form, expression and inventiveness of any art or craft. Similarly a Shilpin, notes Kramrisch, is a complex Sanskrit word, describing any person who embodies art, science, culture, skill, rhythm and employs creative principles to produce any divine form of expression. Silpins who built Hindu temples, as well as the art works and sculpture within them, were considered by the ancient Sanskrit texts to deploy arts whose number are unlimited, Kala (techniques) that were 64 in number,[78] and Vidya (science) that were of 32 types.[46]

The Hindu manuals of temple construction describe the education, characteristics of good artists and architects. The general education of a Hindu Shilpin in ancient India included Lekha or Lipi (alphabet, reading and writing), Rupa (drawing and geometry), Ganana (arithmetic). These were imparted from age 5 to 12. The advanced students would continue in higher stages of Shilpa Sastra studies till the age of 25.[79][80] Apart from specialist technical competence, the manuals suggest that best Silpins for building a Hindu temple are those who know the essence of Vedas and Agamas, consider themselves as students, keep well verse with principles of traditional sciences and mathematics, painting and geography.[34] Further they are kind, free from jealousy, righteous, have their sense under control, of happy disposition, and ardent in everything they do.[46]

According to Silparatna, a Hindu temple project would start with a Yajamana (patron), and include a Sthapaka (guru, spiritual guide and architect-priest), a Sthapati (architect) who would design the building, a Sutragrahin (surveyor), and many Vardhakins (workers, masons, painters, plasterers, overseers) and Taksakas (sculptors).[34][48] While the temple is under construction, all those working on the temple were revered and considered sacerdotal by the patron as well as others witnessing the construction.[76] Further, it was a tradition that all tools and materials used in temple building and all creative work had the sanction of a sacrament.[34] For example, if a carpenter or sculptor needed to fell a tree or cut a rock from a hill, he would propitiate the tree or rock with prayers, seeking forgiveness for cutting it from its surroundings, and explaining his intent and purpose. The axe used to cut the tree would be anointed with butter to minimize the hurt to the tree.[46] Even in modern times, in some parts of India such as Odisha, Visvakarma Puja is a ritual festival every year where the craftsmen and artists worship their arts, tools and materials.[81]

Social functions of Hindu temples

Hindu temples served as nuclei of important social, economic, artistic and intellectual functions in ancient and medieval India.[82][83] Burton Stein states that South Indian temples managed regional development function, such as irrigation projects, land reclamation, post-disaster relief and recovery. These activities were paid for by the donations (melvarum) they collected from devotees.[13] According to James Heitzman, these donations came from a wide spectrum of the Indian society, ranging from kings, queens, officials in the kingdom to merchants, priests and shepherds.[84] Temples also managed lands endowed to it by its devotees upon their death. They would provide employment to the poorest.[85] Some temples had large treasury, with gold and silver coins, and these temples served as banks.[86]

Hindu temples over time became wealthy from grants and donations from royal patrons as well as private individuals. Major temples became employers and patrons of economic activity. They sponsored land reclamation and infrastructure improvements, states Michell, including building facilities such as water tanks, irrigation canals and new roads.[87] A very detailed early record from 1101 lists over 600 employees (excluding the priests) of the Brihadisvara Temple, Thanjavur, still one of the largest temples in Tamil Nadu. Most worked part-time and received the use of temple farmland as reward.[87] For those thus employed by the temple, according to Michell, "some gratuitous services were usually considered obligatory, such as dragging the temple chariots on festival occasions and helping when a large building project was undertaken".[87] Temples also acted as refuge during times of political unrest and danger.[87]

In contemporary times, the process of building a Hindu temple by emigrants and diasporas from South Asia has also served as a process of building a community, a social venue to network, reduce prejudice and seek civil rights together.[88]

Library of manuscripts

| |||||

John Guy and Jorrit Britschgi state Hindu temples served as centers where ancient manuscripts were routinely used for learning and where the texts were copied when they wore out.[89] In South India, temples and associated mutts served custodial functions, and a large number of manuscripts on Hindu philosophy, poetry, grammar and other subjects were written, multiplied and preserved inside the temples.[90] Archaeological and epigraphical evidence indicates existence of libraries called Sarasvati-bhandara, dated possibly to early 12th-century and employing librarians, attached to Hindu temples.[91]

Palm-leaf manuscripts called lontar in dedicated stone libraries have been discovered by archaeologists at Hindu temples in Bali Indonesia and in 10th century Cambodian temples such as Angkor Wat and Banteay Srei.[92]

Temple schools

Inscriptions from the 4th century CE suggest the existence of schools around Hindu temples, called Ghatikas or Mathas, where the Vedas were studied.[93] In south India, 9th century Vedic schools attached to Hindu temples were called Calai or Salai, and these provided free boarding and lodging to students and scholars.[94][95] The temples linked to Bhakti movement in the early 2nd millennium, were dominated by non-Brahmins.[96] These assumed many educational functions, including the exposition, recitation and public discourses of Sanskrit and Vedic texts.[96] Some temple schools offered wide range of studies, ranging from Hindu scriptures to Buddhist texts, grammar, philosophy, martial arts, music and painting.[82][97] By the 8th century, Hindu temples also served as the social venue for tests, debates, team competition and Vedic recitals called Anyonyam.[82][97]

Hospitals, community kitchen, monasteries

According to Kenneth G. Zysk – a professor specializing in Indology and ancient medicine, Hindu mathas and temples had by the 10th-century attached medical care along with their religious and educational roles.[98] This is evidenced by various inscriptions found in Bengal, Andhra Pradesh and elsewhere. An inscription dated to about 930 CE states the provision of a physician to two matha to care for the sick and destitute. Another inscription dated to 1069 at a Vishnu temple in Tamil Nadu describes a hospital attached to the temple, listing the nurses, physicians, medicines and beds for patients. Similarly, a stone inscription in Andhra Pradesh dated to about 1262 mentions the provision of a prasutishala (maternity house), vaidya (physician), an arogyashala (health house) and a viprasattra (hospice, kitchen) with the religious center where people from all social backgrounds could be fed and cared for.[98][99] According to Zysk, both Buddhist monasteries and Hindu religious centers provided facilities to care for the sick and needy in the 1st millennium, but with the destruction of Buddhist centers after the 12th century, the Hindu religious institutions assumed these social responsibilities.[98] According to George Michell, Hindu temples in South India were active charity centers and they provided free meal for wayfarers, pilgrims and devotees, as well as boarding facilities for students and hospitals for the sick.[100]

The 15th and 16th century Hindu temples at Hampi featured storage spaces (temple granary, kottara), water tanks and kitchens.[101][102][103] Many major pilgrimage sites have featured dharmashalas since early times. These were attached to Hindu temples, particularly in South India, providing a bed and meal to pilgrims. They relied on any voluntary donation the visitor may leave and to land grants from local rulers.[104] Some temples have operated their kitchens on a daily basis to serve the visitor and the needy, while others during major community gatherings or festivals. Examples include the major kitchens run by Hindu temples in Udupi (Karnataka), Puri (Odisha) and Tirupati (Andhra Pradesh). The tradition of sharing food in smaller temple is typically called prasada.[104][105]

Styles

Hindu temples are found in diverse locations each incorporating different methods of construction and styles:

- Mountain[59] temples such as Masrur

- Cave[106] temples such as Chandrabhaga, Chalukya[107] and Ellora

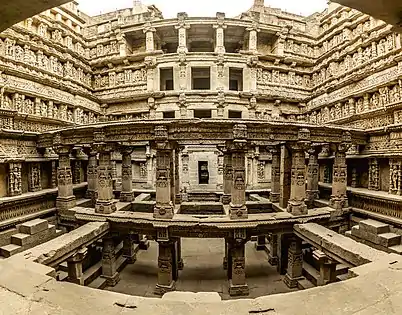

- Step well temple compounds such as the Mata Bhavani, Ankol Mata and Huccimallugudi.[108]

- Forest[106] temples such as Kasaun and Kusama[109]

- River bank and sea shore temples such as Somnath.

- Step well temples

In arid western parts of India, such as Rajasthan and Gujarat, Hindu communities built large walk-in wells that served as the only source of water in dry months but also served as social meeting places and carried religious significance. These monuments went down into the earth towards subterranean water, up to seven storeys, and were part of a temple complex.[110] These vav (literally, stepwells) had intricate art reliefs on the walls, with numerous murtis and images of Hindu deities, water spirits and erotic symbolism. The step wells were named after Hindu deities; for example, Mata Bhavani's Stepwell, Ankol Mata Vav, Sikotari Vav and others.[110] The temple ranged from being small single pada (cell) structure to large nearby complexes. These stepwells and their temple compounds have been variously dated from late 1st millennium BCE through 11th century CE. Of these, Rani ki vav, with hundreds of art reliefs including many of Vishnu deity avatars, has been declared a UNESCO World Heritage site.[111]

- Cave temples

The Indian rock-cut architecture evolved in Maharashtran temple style in the 1st millennium CE. The temples are carved from a single piece of rock as a complete temple or carved in a cave to look like the interior of a temple. Ellora Temple is an example of the former, while The Elephanta Caves are representative of the latter style.[112] The Elephanta Caves consist of two groups of caves—the first is a large group of five Hindu caves and the second is a smaller group of two Buddhist caves. The Hindu caves contain rock-cut stone sculptures, representing the Shaiva Hindu sect, dedicated to the god Shiva.[112]

Arts inside Hindu temples

A typical, ancient Hindu temple has a profusion of arts – from paintings to sculpture, from symbolic icons to engravings, from thoughtful layout of space to fusion of mathematical principles with Hindu sense of time and cardinality.

Ancient Sanskrit texts classify murtis and images in a number of ways. For example, one method of classification is the dimensionality of completion:[113]

- Chitra: images that are three-dimensional and completely formed

- Chitrardha: images that are engraved in half relief

- Chitrabhasa: images that are two-dimensional, such as paintings on walls and cloth

Another way of classification is by the expressive state of the image:

- Raudra or Dugra: are images that were meant to terrify, induce fear. These typically have wide, circular eyes, carry weapons, have skulls and bones as adornment. These murtis were worshiped by soldiers before going to war, or by people in times of distress or terrors. Raudra deity temples were not set up inside villages or towns, but invariably outside and in remote areas of a kingdom.[113]

- Shanta and saumya: are images that were pacific, peaceful and expressive of love, compassion, kindness and other virtues in Hindu pantheon. These images would carry symbolic icons of peace, knowledge, music, wealth, flowers, sensuality among other things. In ancient India, these temples were predominant inside villages and towns.[113]

A Hindu temple may or may not include a murti or images, but larger temples usually do. Personal Hindu temples at home or a hermitage may have a pada for yoga or meditation, but be devoid of anthropomorphic representations of god. Nature or others arts may surround him or her. To a Hindu yogin, states Gopinath Rao,[113] one who has realised the Self and the Universal Principle within himself, there is no need for any temple or divine image for worship. However, for those who have yet to reach this height of realization, various symbolic manifestations through images, murtis and icons as well as mental modes of worship are offered as one of the spiritual paths in the Hindu way of life. Some ancient Hindu scriptures like the Jabaladarshana Upanishad appear to endorse this idea[113]

शिवमात्मनि पश्यन्ति प्रतिमासु न योगिनः ।

अज्ञानं भावनार्थाय प्रतिमाः परिकल्पिताः ॥५९॥

- जाबालदर्शनोपनिषत्A yogin perceives god (Siva) within himself; images are for those who have not reached this knowledge.

— Jabaladarsana Upanishad, verse 59[114]

However, devotees aspiring to a personal relationship with the Supreme Lord, whom they worship variously as Krishna or Shiva, for example, tend to reverse such hierarchical views of self-realization, holding that the personal form of the deity, as the source of the Brahma-jyoti, or the light into which impersonalists, according to their ideals, propose to merge themselves and their individual identities, will benevolently accept worship through an arca vigraha, an authorized form constructed not according to imagination but in pursuit of scriptural directives.

Historical development and destruction

A number of ancient Indian texts suggest the prevalence of murtis, temples and shrines in Indian subcontinent for thousands of years. For example, the temples of the Koshala kingdom are mentioned in the Valmiki Ramayana[115] (various recent scholars' estimates for the earliest stage of the text range from the 7th to 4th centuries BCE, with later stages extending up to the 3rd century CE)[116] The 5th century BCE text, Astadhyayi, mentions male deity arcas or murtis of Agni, Indra, Varuna, Rudra, Mrda, Pusa, Surya, and Soma being worshipped, as well as the worship of arcas of female goddesses such as Indrani, Varunani, Usa, Bhavani, Prthivi and Vrsakapayi.[117] The 2nd century BCE "Mahabhasya" of Patanjali extensively describes temples of Dhanapati (deity of wealth and finance, Kubera), as well as temples of Rama and Kesava, wherein the worship included dance, music and extensive rituals. The Mahabhasya also describes the rituals for Krsna, Visnu and Siva. An image recovered from Mathura in north India has been dated to the 2nd century BCE.[117] Kautilya's Arthashastra from 4th century BCE describes a city of temples, each enshrining various Vedic and Puranic deities. All three of these sources have common names, describe common rituals, symbolism and significance possibly suggesting that the idea of murtis, temples and shrines passed from one generation to next, in ancient India, at least from the 4th century BCE.[117] The oldest temples, suggest scholars, were built of brick and wood. Stone became the preferred material of construction later.[118][119]

Early Jain and Buddhist literature, along with Kautilya's Arthashastra, describe structures, embellishments and designs of these temples – all with motifs and deities currently prevalent in Hinduism. Bas-reliefs and murtis have been found from 2nd to 3rd century, but none of the temple structures have survived. Scholars[117] theorize that those ancient temples of India, later referred to as Hindu temples, were modeled after domestic structure – a house or a palace. Beyond shrines, nature was revered, in forms such as trees, rivers, and stupas, before the time of Buddha and Vardhamana Mahavira. As Jainism and Buddhism branched off from the religious tradition later to be called Hinduism, the ideas, designs and plans of ancient Vedic and Upanishad era shrines were adopted and evolved, likely from the competitive development of temples and arts in Jainism and Buddhism. Ancient reliefs found so far, states Michael Meister,[117] suggest five basic shrine designs and combinations thereof in 1st millennium BCE:

- A raised platform with or without a symbol

- A raised platform under an umbrella

- A raised platform under a tree

- A raised platform enclosed with a railing

- A raised platform inside a pillared pavilion

Many of these ancient shrines were roofless, some had toranas and roof.

From the 1st century BCE through 3rd century CE, the evidence and details about ancient temples increases. The ancient literature refers to these temples as Pasada (or Prasada), stana, mahasthana, devalaya, devagrha, devakula, devakulika, ayatana and harmya.[117] The entrance of the temple is referred to as dvarakosthaka in these ancient texts notes Meister,[117] the temple hall is described as sabha or ayagasabha, pillars were called kumbhaka, while vedika referred to the structures at the boundary of a temple.

The 5th-century Ladkhan Shiva Temple, in the Aihole Hindu-Jain-Buddhist temple site, in Karnataka.

The 5th-century Ladkhan Shiva Temple, in the Aihole Hindu-Jain-Buddhist temple site, in Karnataka. Plan of 5th-century temples in Eran, Madhya Pradesh.

Plan of 5th-century temples in Eran, Madhya Pradesh. The early 6th-century Dashavatara Temple in the Deogarh complex has a simple, one-cell plan.

The early 6th-century Dashavatara Temple in the Deogarh complex has a simple, one-cell plan. 1880 sketch of the 9-square floorplan of the same temple (not to scale or complete). For better drawings:[120]

1880 sketch of the 9-square floorplan of the same temple (not to scale or complete). For better drawings:[120] Layout of Cave 3 temple of the 6th-century Chalukyan-style Badami cave temples

Layout of Cave 3 temple of the 6th-century Chalukyan-style Badami cave temples Plan of the 6th-century main-cave temple at Elephanta.

Plan of the 6th-century main-cave temple at Elephanta. The Elephanta main cave is thought to follow this mandala design.[121]

The Elephanta main cave is thought to follow this mandala design.[121] A 7th century Chalukyan-style temple ceiling, also in Aihole.

A 7th century Chalukyan-style temple ceiling, also in Aihole. Rani ki vav is an 11th-century stepwell, built by the Chaulukya dynasty, located in Patan. The stepwell remains well-preserved, but is partly silted over.

Rani ki vav is an 11th-century stepwell, built by the Chaulukya dynasty, located in Patan. The stepwell remains well-preserved, but is partly silted over.

| |||||

With the start of Gupta dynasty in the 4th century, Hindu temples flourished in innovation, design, scope, form, use of stone and new materials as well as symbolic synthesis of culture and dharmic principles with artistic expression.[122][123] It is this period that is credited with the ideas of garbhagrha for Purusa, mandapa for sheltering the devotees and rituals in progress, as well as symbolic motifs relating to dharma, karma, kama, artha and moksha. Temple superstructures were built from stone, brick and wide range of materials. Entrance ways, walls and pillars were intricately carved, while parts of temple were decorated with gold, silver and jewels. Visnu, Siva and other deities were placed in Hindu temples, while Buddhists and Jains built their own temples, often side by side with Hindus.[124]

The 4th through 6th century marked the flowering of Vidharbha style, whose accomplishments survive in central India as Ajanta caves, Pavnar, Mandhal and Mahesvar. In the Malaprabha river basin, South India, this period is credited with some of the earliest stone temples of the region: the Badami Chalukya temples are dated to the 5th century by some scholars,[125] and the 6th by some others.[126]

Over 6th and 7th centuries, temple designs were further refined during Maurya dynasty, evidence of which survives today at Ellora and in the Elephanta cave temples.

It is the 5th through 7th century CE when outer design and appearances of Hindu temples in north India and south India began to widely diverge.[127] Nevertheless, the forms, theme, symbolism and central ideas in the grid design remained same, before and after, pan-India as innovations were adopted to give distinctly different visual expressions.

The Western Chalukya architecture of the 11th- & 12th-century Tungabhadra region of modern central Karnataka includes many temples. Step-wells are consist of a shaft dug to the water table, with steps descending to the water; while they were built for secular purposes, some are also decorated as temples, or serve as a temple tank.

During the 5th to 11th century, Hindu temples flourished outside Indian subcontinent, such as in Cambodia, Viet Nam, Malaysia and Indonesia. In Cambodia, Khmer architecture favoured the Temple mountain style famously used in Angkor Wat, with a prang spire over the sanctum cell. Indonesian candi developed regional forms. In what is modern south and central Viet Nam, Champa architecture built brick temples.

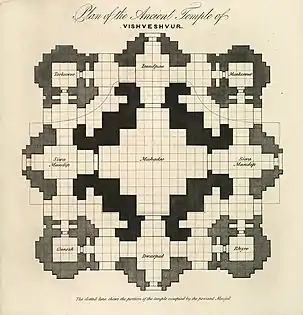

Destruction, conversion, and rebuilding Many Hindu temples have been destroyed, some, after rebuilding, several times. Deliberate temple destruction usually had religious motives. Richard Eaton has listed 80 campaigns of Hindu temple site destruction stretching over centuries, particularly from the 12th through the 18th century.[128] Others temples have served as non-Hindu places of worship, either after conversion or simultaneously with Hindu use.

In the 12th-16th century, during Muslim conquests in the Indian subcontinent and South Asia, Hindu temples, along with the temples of Buddhists and Jains, intermittently became targets of armies from Persian, Central Asian, and Indian sultanates. Imagined by these foreign zealots to be mere idols, sacred Forms of various deities were broken, spires and pillars were torn down, and temples were looted of their treasury. Some temples were converted into mosques, or parts used to build mosques.[129] There exist both Indian and Muslim traditions of religious toleration. Muslim rulers led campaigns of temple destruction and forbade repairs to damaged temples, following the Muslim traditions. The Delhi Sultanate destroyed a large number of temples; Sikandar the Iconoclast, Sultan of Kashmir, was also known for his intolerance.[130]

The 16th- and 19th-century Goa Inquisition destroyed hundreds of Hindu temples. All Hindu temples in Portuguese colonies in India were destroyed, according to a 1569 letter in the Portuguese royal archives.[131] Temples were not converted into churches. Religious conflict and desecrations of places of worship continued during the British colonial era.[132] Historian Sita Ram Goel's book "What happened to Hindu Temples" lists over 2000 sites where temples have been destroyed and mosques have been built over them. Some historians suggest that around 30,000 temples were destroyed by Islamic rulers between 1200 and 1800 CE. Destruction of Hindu temple sites was comparatively less in the southern parts of India, such as in Tamil Nadu. Cave-style Hindu temples that were carved inside a rock, hidden and rediscovered centuries later, such as the Kailasha Temple, have also preferentially survived. Many are now UNESCO world heritage sites.[133]

In India, the Place of Worship (Special Provisions) Act was enacted in 1991 which prohibited the conversion of any religious site from the religion to which it was dedicated on 15 August 1947.[134][135][136]

.jpg.webp) The Somnath temple in Gujarat was repeatedly destroyed and rebuilt. Here it is shown in 1869, after having been ruined by order of Aurangzeb in 1665. These ruins were demolished and the temple rebuilt in the 1950s.

The Somnath temple in Gujarat was repeatedly destroyed and rebuilt. Here it is shown in 1869, after having been ruined by order of Aurangzeb in 1665. These ruins were demolished and the temple rebuilt in the 1950s..jpg.webp) The Kashi Vishwanath Temple was destroyed by the army of Qutb al-Din Aibak in 1194 CE. Since then, it has been demolished twice (in the 1400s, and 1669 CE) and rebuilt four times (in the 1200s, twice in the 1500s under Akbar, and in the 1800s). Shown is the current 1800s temple, with the white domes and minaret of the co-located 1600s Gyanvapi Mosque in the background. The tonne of gold for the temple roof was donated by Ranjit Singh in 1835.[137][138]

The Kashi Vishwanath Temple was destroyed by the army of Qutb al-Din Aibak in 1194 CE. Since then, it has been demolished twice (in the 1400s, and 1669 CE) and rebuilt four times (in the 1200s, twice in the 1500s under Akbar, and in the 1800s). Shown is the current 1800s temple, with the white domes and minaret of the co-located 1600s Gyanvapi Mosque in the background. The tonne of gold for the temple roof was donated by Ranjit Singh in 1835.[137][138] An 1832 reconstruction of the 1500s temple Akbar funded. James Prinsep based the reconstruction on the foundations of the Gyanvapi Mosque. Many Hindu temples were rebuilt as mosques between 12th and 18th century CE.

An 1832 reconstruction of the 1500s temple Akbar funded. James Prinsep based the reconstruction on the foundations of the Gyanvapi Mosque. Many Hindu temples were rebuilt as mosques between 12th and 18th century CE. Ruins of the Martand Sun Temple after being destroyed on the orders of the Sultan of Kashmir, Sikandar the Iconoclast, in the early 15th century, with demolition lasting a year.

Ruins of the Martand Sun Temple after being destroyed on the orders of the Sultan of Kashmir, Sikandar the Iconoclast, in the early 15th century, with demolition lasting a year. In the 14th century, the armies of Delhi Sultanate, led by Malik Kafur, plundered the Meenakshi Temple and looted it of its valuables; it was rebuilt and expanded in the 16th century.

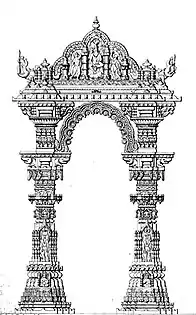

In the 14th century, the armies of Delhi Sultanate, led by Malik Kafur, plundered the Meenakshi Temple and looted it of its valuables; it was rebuilt and expanded in the 16th century. Kakatiya Kala Thoranam (the Warangal Gate) built in the 12th century by the Kakatiya dynasty; the Warangal Fort temple complex was destroyed in the 1300s by the Delhi Sultanate.[139]

Kakatiya Kala Thoranam (the Warangal Gate) built in the 12th century by the Kakatiya dynasty; the Warangal Fort temple complex was destroyed in the 1300s by the Delhi Sultanate.[139] Artistic rendition of the Kirtistambh, a surviving portion of the 10-11th century Rudra Mahalaya Temple. The temple was partly destroyed by the Sultan of Delhi, Alauddin Khalji, in 1296 CE, with part converted into a mosque and further parts destroyed by Ahmed Shah I in the fifteenth century.

Artistic rendition of the Kirtistambh, a surviving portion of the 10-11th century Rudra Mahalaya Temple. The temple was partly destroyed by the Sultan of Delhi, Alauddin Khalji, in 1296 CE, with part converted into a mosque and further parts destroyed by Ahmed Shah I in the fifteenth century. Exterior wall reliefs at Hoysaleswara Temple. The temple was twice sacked and plundered by the Delhi Sultanate in the early 14th century, and abandoned in the mid 14th century.[140]

Exterior wall reliefs at Hoysaleswara Temple. The temple was twice sacked and plundered by the Delhi Sultanate in the early 14th century, and abandoned in the mid 14th century.[140] The 12th-century Mahadev Temple is the only Kadamba-period temple building to survive the Goa Inquisition.

The 12th-century Mahadev Temple is the only Kadamba-period temple building to survive the Goa Inquisition.

Customs and etiquette

The customs and etiquette varies across India. Devotees in major temples may bring in symbolic offerings for the puja. This includes fruits, flowers, sweets and other symbols of the bounty of the natural world. Temples in India are usually surrounded with small shops selling these offerings.

When inside the temple, devotees keep both hands folded (namaste mudra). The inner sanctuary, where the murtis reside, is known as the garbhagriha. It symbolizes the birthplace of the universe, the meeting place of the gods and mankind, and the threshold between the transcendental and the phenomenal worlds.[141] It is in this inner shrine that devotees seek a darsana of, where they offer prayers. Devotees may or may not be able to personally present their offerings at the feet of the deity. In most large Indian temples, only the pujaris (priest) are allowed to enter into the main sanctum.[142]

Temple management staff typically announce the hours of operation, including timings for special pujas. These timings and nature of special puja vary from temple to temple. Additionally, there may be specially allotted times for devotees to perform circumambulations (or pradakshina) around the temple.[142]

Visitors and worshipers to large Hindu temples may be required to deposit their shoes and other footwear before entering. Where this is expected, the temples provide an area and help staff to store footwear. Dress codes vary. It is customary in temples in Kerala, for men to remove shirts and to cover pants and shorts with a traditional cloth known as a Vasthiram.[143] In Java and Bali (Indonesia), before one enters the most sacred parts of a Hindu temple, shirts are required as well as Sarong around one's waist.[144] At many other locations, this formality is unnecessary.

Regional variations in Hindu temples

Nagara Architecture of North Indian temples

North Indian temples are referred to as Nagara style of temple architecture.[145] They have sanctum sanctorum where the deity is present, open on one side from where the devotee obtains darśana. There may or may not be many more surrounding corridors, halls, etc. However, there will be space for devotees to go around the temple in clockwise fashion circumambulation. In North Indian temples, the tallest towers are built over the sanctum sanctorum in which the deity is installed.[146]

The north India Nagara style of temple designs often deploy fractal-theme, where smaller parts of the temple are themselves images or geometric re-arrangement of the large temple, a concept that later inspired French and Russian architecture such as the matryoshka principle. One difference is the scope and cardinality, where Hindu temple structures deploy this principle in every dimension with garbhgriya as the primary locus, and each pada as well as zones serving as additional centers of loci. This makes a Nagara Hindu temple architecture symbolically a perennial expression of movement and time, of centrifugal growth fused with the idea of unity in everything.[145]

Temples in West Bengal

In West Bengal, the Bengali terra cotta temple architecture is found. Due to lack of suitable stone in the alluvial soil locally available, the temple makers had to resort to other materials instead of stone. This gave rise to using terracotta as a medium for temple construction. Terracotta exteriors with rich carvings are a unique feature of Bengali temples. The town of Vishnupur in West Bengal is renowned for this type of architecture. There is also a popular style of building known as Navaratna (nine-towered) or Pancharatna (five-towered). An example of Navaratna style is the Dakshineswar Kali Temple.[147]

Temples in Odisha

Odisha temple architecture is known as Kalinga architecture,[148] classifies the spire into three parts, the Bāḍa (lower limb), the Ganḍi (body) and the Cuḷa/Mastaka (head). Each part is decorated in a different manner. Kalinga architecture is a style which flourished in Kalinga, the name for kingdom that included ancient Odisha. It includes three styles: Rekha Deula, Pidha Deula and Khakhara Deula.[149] The former two are associated with Vishnu, Surya and Shiva temples while the third is mainly associated with Chamunda and Durga temples. The Rekha Deula and Khakhara Deula houses the sanctum sanctorum while the Pidha Deula style includes space for outer dancing and offering halls.

Temples of Goa and other Konkani temples

The temple architecture of Goa is quite unique. As Portuguese colonial hegemony increased, Goan Hindu temples became the rallying point to local resistance.[150] Many these temples are not more than 500 years old, and are a unique blend of original Goan temple architecture, Dravidian, Nagar and Hemadpanthi temple styles with some British and Portuguese architectural influences. Goan temples were built using sedimentary rocks, wood, limestone and clay tiles, and copper sheets were used for the roofs. These temples were decorated with mural art called as Kavi kala or ocher art. The interiors have murals and wood carvings depicting scenes from the Hindu mythology.

South Indian and Sri Lankan temples

South Indian temples have a large gopuram, a monumental tower, usually ornate, at the entrance of the temple. This forms a prominent feature of Koils, Hindu temples of the Dravidian style.[151] They are topped by the kalasam, a bulbous stone finial. They function as gateways through the walls that surround the temple complex.[152] The gopuram's origins can be traced back to early structures of the Tamil kings Pallavas; and by the twelfth century, under the Pandya rulers, these gateways became a dominant feature of a temple's outer appearance, eventually overshadowing the inner sanctuary which became obscured from view by the gopuram's colossal size.[153] It also dominated the inner sanctum in amount of ornamentation. Often a shrine has more than one gopuram.[154] They also appear in architecture outside India, especially Khmer architecture, as at Angkor Wat. A koil may have multiple gopurams, typically constructed into multiple walls in tiers around the main shrine. The temple's walls are typically square with the outer most wall having gopuras. The sanctum sanctorum and its towering roof (the central deity's shrine) are also called the vimanam.[155] The inner sanctum has restricted access with only priests allowed beyond a certain point.

Temples in Kerala

Temples in Kerala have a different architectural style (keeping the same essence of Vastu), especially due to climatic differences Kerala have with other parts of India with larger rainfall. The temple roof is mostly tiled and is sloped and the walls are often square, the innermost shrine being entirely enclosed in another four walls to which only the pujari (priest) enters. The walls are decorated with either mural paintings or rock sculptures which many times are emphasised on Dwarapalakas.

Temples in Tamil Nadu

Temple construction reached its peak during rule of Pallavas. They built various temples around Kancheepuram, and Narasimhavarman II built the Shore Temple in Mamallapuram, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Pandyas rule created temples such as the Meenakshi Amman Temple at Madurai and Nellaiappar Temple at Tirunelveli.[156] The Cholas were prolific temple builders right from the times of the first medieval king Vijayalaya Chola. The Chola temples include Nataraja temple at Chidambaram, the Sri Ranganathaswamy Temple at Srirangam, the Brihadeeshwarar temple at Tanjore, Brihadeeshwarar temple at Gangaikonda Cholapuram and the Airavatesvarar Temple of Darasuram which are among the UNESCO World Heritage Sites. The Nayaks of Madurai reconstructed some of the well-known temples in Tamil Nadu such as the Meenakshi Temple.[11]

Temples in Nepal

Pashupatinath temple is one of the important temples of Hindu religion which is situated in Kathmandu, Nepal.[157] It is built in a pagoda style and is surrounded by hundreds of temples and buildings built by kings. The temples top is made from pure gold.

Khmer Temples

Angkor Wat was built as a Hindu temple by King Suryavarman II in the early 12th century in Yasodharapura (Khmer, present-day Angkor), the capital of the Khmer Empire, as his state temple and eventual mausoleum. Breaking from the Shaiva tradition of previous kings, Angkor Wat was instead dedicated to Vishnu. The Spire in Khmer Hindu temple is called Giri (mountain) and symbolizes the residence of gods just like Meru does in Bali Hindu mythology and Ku (Guha) does in Burmese Hindu mythology.[158]

Angkor Wat is just one of numerous Hindu temples in Cambodia, most of them in ruins. Hundreds of Hindu temples are scattered from Siem Reap to Sambor Prei Kuk in central Cambodian region.[159]

Temples in Indonesia

Ancient Hindu temples in Indonesia are called Candi (read: chandi). Prior to the rise of Islam, between the 5th to 15th century Dharmic faiths (Hinduism and Buddhism) were the majority in Indonesian archipelago, especially in Java and Sumatra. As the result numerous Hindu temples, locally known as candi, constructed and dominated the landscape of Java. According to local beliefs, Java valley had thousands of Hindu temples which co-existed with Buddhist temples, most of which were buried in massive eruption of Mount Merapi in 1006 CE.[160][161]

Between 1100 and 1500 additional Hindu temples were built, but abandoned by Hindus and Buddhists as Islam spread in Java circa 15th to 16th century. In last 200 years, some of these have been rediscovered mostly by farmers while preparing their lands for crops. Most of these ancient temples were rediscovered and reconstructed between 19th to 20th century, and treated as the important archaeological findings and also as tourist attraction, but not as the house of worship. Hindu temples of ancient Java bear resemblances with temples of South Indian style. The largest of these is the 9th century Javanese Hindu temple, Prambanan in Yogyakarta, now a UNESCO world heritage site. It was designed as three concentric squares and has 224 temples. The inner square contains 16 temples dedicated to major Hindu deities, of which Shiva temple is the largest.[162] The temple has extensive wall reliefs and carvings illustrating the stories from the Hindu epic Ramayana.[163]

In Bali, the Hindu temple is known as "Pura", which is designed as an open-air worship place in a walled compound. The compound walls have a series of intricately decorated gates without doors for the devotee to enter. The design, plan and layout of the holy pura follows a square layout.[164][165]

Majority of Hindu temples in Java were dedicated to Shiva, who Javanese Hindus considered as the God who commands the energy to destroy, recombine and recreate the cycle of life. Small temples were often dedicated to Shiva and his family (wife Durga, son Ganesha). Larger temple complexes include temples for Vishnu and Brahma, but the most majestic, sophisticated and central temple was dedicated to Shiva. The 732 CE Canggal inscription found in Southern Central Java, written in Indonesian Sanskrit script, eulogizes Shiva, calling him God par-excellence.

Temples in Vietnam

There are a number of Hindu temple clusters built by the Champa Kingdoms along the coast of Vietnam, with some on UNESCO world heritage site list.[166] Examples include Mỹ Sơn – a cluster of 70 temples with earliest dated to be from the 4th century CE and dedicated to Siva, while others are dedicated to Hindu deities Krishna, Vishnu and others. These temples, internally and with respect to each other, are also built on the Hindu perfect square grid concept. Other sites in Vietnam with Hindu temples include Phan Rang with the Cham temple Po Klong Garai.[167]

Temples in Thailand

Thailand has many notable Hindu temples including: the Sri Mariammam temple in Bangkok, the Devasathan, the Erawan Shrine, Prasat Muang Tam, Sdok Kok Thom and Phanom Rung. Most of the newer Hindu temples are of South Indian origin and were built by Tamil migrant communities. However, Thailand has many historic indigenous Hindu temples such as Phanom Rung. Although most indigenous Hindu temples are ruins, a few such as Devasathan in Bangkok are actively used.

Temples outside Asia

Many members of the diaspora from the Indian subcontinent have established Hindu temples outside India as a means of preserving and celebrating cultural and spiritual heritage abroad. Describing the hundreds of temples that can be found throughout the United States, scholar Gail M. Harley observes, "The temples serve as central locations where Hindus can come together to worship during holy festivals and socialize with other Hindus. Temples in America reflect the colorful kaleidoscopic aspects contained in Hinduism while unifying people who are disbursed throughout the American landscape."[168] Numerous temples in North America and Europe have gained particular prominence and acclaim, many of which were built by the Bochasanwasi Akshar Purushottam Swaminarayan Sanstha. The Ganesh temple of Hindu Temple Society of North America, in Flushing, Queens, New York City, is the oldest Hindu temple in the Western Hemisphere, and its canteen feeds 4,000 people a week, with as many as 10,000 during the Diwali (Deepavali) festival.[169]

.jpg.webp) The Ganesh temple of Hindu Temple Society of North America is the oldest Hindu temple in the Western hemisphere, in Flushing, Queens, New York City.

The Ganesh temple of Hindu Temple Society of North America is the oldest Hindu temple in the Western hemisphere, in Flushing, Queens, New York City. Swaminarayan Akshardham in Robbinsville, New Jersey, U.S., is the largest Hindu temple in the Western hemisphere.[170]

Swaminarayan Akshardham in Robbinsville, New Jersey, U.S., is the largest Hindu temple in the Western hemisphere.[170] BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir in London, United Kingdom.

BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir in London, United Kingdom. BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir in Toronto, Canada.

BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir in Toronto, Canada. BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir in Los Angeles, United States.

BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir in Los Angeles, United States. BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir in Houston, United States.

BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir in Houston, United States. BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir in Atlanta, United States.

BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir in Atlanta, United States. BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir in Chicago, United States.

BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir in Chicago, United States.

Temple management

The Archaeological Survey of India has control of most ancient temples of archaeological importance in India. In India, day-to-day activities of a temple is managed by a temple board committee that administers its finances, management, and events. Since independence, the autonomy of individual Hindu religious denominations to manage their own affairs with respect to temples of their own denomination has been severely eroded and the state governments have taken control of major Hindu temples in some countries; however, in others, such as the United States, private temple management autonomy has been preserved.

Etymology and nomenclature

In Sanskrit, the liturgical language of Hinduism, the word mandira means "house" (Sanskrit: मन्दिर). Ancient Sanskrit texts use many words for temple, such as matha, vayuna, kirti, kesapaksha, devavasatha, vihara, suravasa, surakula, devatayatana, amaragara, devakula, devagrha, devabhavana, devakulika, and niketana.[171] Regionally, they are also known as prasada, vimana, kshetra, gudi, ambalam, punyakshetram, deval, deula, devasthanam, kovil, candi, pura, and wat.

The following are the other names by which a Hindu temple is referred to in India:

- Devasthana (ದೇವಸ್ಥಾನ) in Kannada

- Deul/Doul/Dewaaloy in Assamese and in Bengali

- Deval/Raul/Mandir (मंदिर) in Marathi

- Devro/Mindar in Rajasthani

- Deula (ଦେଉଳ) or Mandira(ମନ୍ଦିର) in Odia and Gudi in Kosali Odia

- Gudi (గుడి), Devalayam (దేవాలయం), Devasthanam (దేవస్థానము), Kovela (కోవెల), Kshetralayam (క్షేత్రాలయం), Punyakshetram (పుణ్యక్షేత్రం), or Punyakshetralayam (పుణ్యక్షేత్రాలయం), Mandiramu (మందిరము) in Telugu

- Kovil or kō-vill (கோவில்) and occasionally Aalayam (ஆலயம்) in Tamil; the Tamil word Kovil means "residence of God"[172]

- Kshetram (ക്ഷേത്രം), Ambalam (അമ്പലം), Kovil (കോവിൽ), Devasthanam (ദേവസ്ഥാനം) or Devalayam (ദേവാലയം) in Malayalam

- Mandir (मंदिर) in Hindi, Nepali, Kashmiri, Marathi, Punjabi (ਮੰਦਰ), Gujarati (મંદિર), and Urdu (مندر)[173]

- Mondir (মন্দির) in Bengali

In Southeast Asia temples known as:

- Candi in Indonesia, especially in Javanese, Malay and Indonesian, used both for Hindu or Buddhist temples.

- Pura in Hindu majority island of Bali, Indonesia.

- Wat in Cambodia and Thailand, also applied to both Hindu and Buddhist temples.

- Temple sites

Some lands, including Varanasi, Puri, Kanchipuram, Dwarka, Amarnath, Kedarnath, Somnath, Mathura and Rameswara, are considered holy in Hinduism. They are called kṣétra (Sanskrit: क्षेत्र[174]). A kṣétra has many temples, including one or more major ones. These temples and its location attracts pilgrimage called tirtha (or tirthayatra).[175]

See also

- List of Hindu temples

- List of Hindu temples in India

- List of Hindu temples outside India

- List of largest Hindu temples

- List of largest Hindu ashrams

- Hindu temple architecture

- Mandi-Mandaean Temple

- Temple

- BAPS

References

- "mandir". The Chambers Dictionary (9th ed.). Chambers. 2003. ISBN 0-550-10105-5.

- "mandir". Collins English Dictionary (13th ed.). HarperCollins. 2018. ISBN 978-0-008-28437-4.

- Stella Kramrisch (1946). The Hindu Temple. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 135, context: 40–43, 110–114, 129–139 with footnotes. ISBN 978-81-208-0223-0., Quote: "The [Hindu] temple is the seat and dwelling of God, according to the majority of the [Indian] names" (p. 135); "The temple as Vimana, proportionately measured throughout, is the house and body of God" (p. 133).

- George Michell (1977). The Hindu Temple: An Introduction to Its Meaning and Forms. University of Chicago Press. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-0-226-53230-1.; Quote: "The Hindu temple is designed to bring about contact between man and the gods" (...) "The architecture of the Hindu temple symbolically represents this quest by setting out to dissolve the boundaries between man and the divine".

- Stella Kramrisch (1946). The Hindu Temple. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 19–43, 135–137, context: 129–144 with footnotes. ISBN 978-81-208-0223-0.

- Subhash Kak, "The axis and the perimeter of the temple." Kannada Vrinda Seminar Sangama 2005 held at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles on 19 November 2005.

- Subhash Kak, "Time, space and structure in ancient India." Conference on Sindhu-Sarasvati Valley Civilization: A Reappraisal, Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles, 21 & 22 February 2009.

- Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, Vol 2, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0222-3, pp. 346-357 and 423-424

- Klaus Klostermaier, "The Divine Presence in Space and Time – Murti, Tirtha, Kala"; in A Survey of Hinduism, ISBN 978-0-7914-7082-4, State University of New York Press, pp. 268-277.

- George Michell (1977). The Hindu Temple: An Introduction to Its Meaning and Forms. University of Chicago Press. pp. 61–76. ISBN 978-0-226-53230-1.

- Susan Lewandowski, "The Hindu Temple in South India", in Buildings and Society: Essays on the Social Development of the Built Environment, Anthony D. King (Ed.), ISBN 978-0710202345, Routledge, Chapter 4

- M.R. Bhat (1996), Brhat Samhita of Varahamihira, ISBN 978-8120810600, Motilal Banarsidass

- Burton Stein, "The Economic Function of a Medieval South Indian Temple", The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 19 (February 1960), pp. 163-76.

- George Michell (1988), The Hindu Temple: An Introduction to Its Meaning and Forms, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0226532301, pp. 58-65.

- Alice Boner (1990), Principles of Composition in Hindu Sculpture: Cave Temple Period, ISBN 978-8120807051, see Introduction and pp. 36-37.

- Francis Ching et al., A Global History of Architecture, Wiley, ISBN 978-0470402573, pp. 227-302.

- Brad Olsen (2004), Sacred Places Around the World: 108 Destinations, ISBN 978-1888729108, pp. 117-119.

- Paul Younger, New Homelands: Hindu Communities, ISBN 978-0195391640, Oxford University Press

- Several books and journal articles have documented the effect on Hindu temples of Islam's arrival in South Asia and Southeast Asia:

- Gaborieau, Marc (1985). "From Al-Beruni to Jinnah: idiom, ritual and ideology of the Hindu-Muslim confrontation in South Asia". Anthropology Today. Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 1 (3): 7–14. doi:10.2307/3033123. JSTOR 3033123.

- Eaton, Richard (2000). "Temple Desecration and Indo-Muslim States". Journal of Islamic Studies. 11 (3): 283–319. doi:10.1093/jis/11.3.283.

- Annemarie Schimmel, Islam in the Indian Subcontinent, ISBN 978-9004061170, Brill Academic, Chapter 1

- Robert W. Hefner, Civil Islam: Muslims and Democratization in Indonesia, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691050461, pp. 28-29.

- Frances Kai-Hwa Wang (28 July 2014). "World's Largest Hindu Temple Being Built in New Jersey". NBC News. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- George Michell (1988), The Hindu Temple: An Introduction to Its Meaning and Forms, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0226532301, Chapter 1

- Subhash Kak, "Time, space and structure in ancient India." Conference on Sindhu-Sarasvati Valley Civilization: A Reappraisal, Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles, 21 & 22 February 2009. arXiv:0903.3252

- Kak, S. Early Indian architecture and art. Migration and Diffusion. vol.6, pp. 6-27 (2005)

- Alain Daniélou (2001), The Hindu Temple: Deification of Eroticism, translated from French to English by Ken Hurry, ISBN 0-89281-854-9, pp. 101-127.

- Samuel Parker (2010), "Ritual as a Mode of Production: Ethnoarchaeology and Creative Practice in Hindu Temple Arts", South Asian Studies, 26(1), pp. 31-57; Michael Rabe, "Secret Yantras and Erotic Display for Hindu Temples", (Editor: David White), ISBN 978-8120817784, Princeton University Readings in Religion (Motilal Banarsidass Publishers), Chapter 25, pp. 435-446.

- Antonio Rigopoulos (1998). Dattatreya: The Immortal Guru, Yogin, and Avatara: A Study of the Transformative and bums Inclusive Character of a Multi-faceted Hindu Deity. State University of New York Press. pp. 223–224, 243. ISBN 978-0-7914-3696-7.

- Alain Daniélou (2001). The Hindu Temple: Deification of Eroticism. Inner Traditions. pp. 69–71. ISBN 978-0-89281-854-9.

- Pyong Gap Min, "Religion and Maintenance of Ethnicity among Immigrants – A Comparison of Indian Hindus and Korean Protestants", in Immigrant Faiths, Karen Leonard (Ed.), ISBN 978-0759108165, Chapter 6, pp. 102-103.

- Susan Lewandowski, The Hindu Temple in South India, in Buildings and Society: Essays on the Social Development of the Built Environment, Anthony D. King (Editor), ISBN 978-0710202345, Routledge, pp. 71-73.

- "Hindu Temple – Vishva Hindu Parishad – Thailand". Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, Vol 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0222-3, page 4

- Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, Vol 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0222-3, page 5-6

- BB Dutt (1925), Town planning in Ancient India at Google Books, ISBN 978-81-8205-487-5; See critical review by LD Barnett, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Vol. 4, Issue 2, June 1926, pp. 391.

- Stella Kramrisch (1976), The Hindu Temple Volume 1 & 2, ISBN 81-208-0223-3

- Jack Hebner (2010), Architecture of the Vastu Sastra – According to Sacred Science, in Science of the Sacred (Editor: David Osborn), ISBN 978-0557277247, pp. 85-92; N Lahiri (1996), Archaeological landscapes and textual images: a study of the sacred geography of late medieval Ballabgarh, World Archaeology, 28(2), pp. 244-264

- Susan Lewandowski (1984), Buildings and Society: Essays on the Social Development of the Built Environment, edited by Anthony D. King, Routledge, ISBN 978-0710202345, Chapter 4

- Sherri Silverman (2007), Vastu: Transcendental Home Design in Harmony with Nature, Gibbs Smith, Utah, ISBN 978-1423601326

- G. D. Vasudev (2001), Vastu, Motilal Banarsidas, ISBN 81-208-1605-6, pp. 74-92.

- LD Barnett, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Vol 4, Issue 2, June 1926, pp. 391.

- Meister, Michael (1983). "Geometry and Measure in Indian Temple Plans: Rectangular Temples". Artibus Asiae. 44 (4): 266–296. doi:10.2307/3249613. JSTOR 3249613.

- Alice Boner and Sadāśiva Rath Śarmā (1966), Silpa Prakasa Medieval Orissan Sanskrit Text on Temple Architecture at Google Books, E.J. Brill (Netherlands)

- H. Daniel Smith (1963), Ed. Pāncarātra prasāda prasādhapam, A Pancaratra Text on Temple-Building, Syracuse: University of Rochester, OCLC 68138877

- Mahanti and Mahanty (1995 Reprint), Śilpa Ratnākara, Orissa Akademi, OCLC 42718271

- Sinha, Amita (1998). "Design of Settlements in the Vaastu Shastras". Journal of Cultural Geography. 17 (2): 27–41. doi:10.1080/08873639809478319.

- Tillotson, G. H. R. (1997). "Svastika Mansion: A Silpa-Sastra in the 1930s". South Asian Studies. 13 (1): 87–97. doi:10.1080/02666030.1997.9628528.

- Stella Kramrisch (1958), Traditions of the Indian Craftsman, The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 71, No. 281, (Jul. - Sep., 1958), pp. 224-230

- Ganapati Sastri (1920), Īśānaśivagurudeva paddhati, Trivandrum Sanskrit Series, OCLC 71801033

- Heather Elgood (2000), Hinduism and the religious arts, ISBN 978-0304707393, Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 121-125.

- H, Kern (1865), The Brhat Sanhita of Varaha-mihara, The Asiatic Society of Bengal, Calcutta

- Susan Lewandowski, The Hindu Temple in South India, in Buildings and Society: Essays on the Social Development of the Built Environment, Anthony D. King (ed.), ISBN 978-0710202345, Routledge, pp. 68-69.

- The square is symbolic and has Vedic origins from the fire altar to Agni. The alignment along cardinal directions, similarly, is an extension of Vedic rituals of three fires. This symbolism is also found among Greek and other ancient civilizations, through the gnomon. In Hindu temple manuals, design plans are described with 1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49, 64, 81 up to 1024 squares; 1 pada is considered the simplest plan, as a seat for a hermit or devotee to sit and meditate on, or make offerings with the Vedic fire in front. The second design of 4 padas lacks the central core, and is also a meditative constructive. The 9-pada design has a sacred surrounded center, and is the template for the smallest temple. Older Hindu temple vastu-mandalas may use the 9- through 49-pada series, but 64 is considered the most sacred geometric grid in Hindu temples. It is also called Manduka, Bhekapada or Ajira in various ancient Sanskrit texts.

- In addition to a square four-sided layout, the Brhat Samhita also describes Vastu and mandala design principles based on a perfect triangle (3), hexagon (6), octagon (8) and hexadecagon (16) sided layouts, according to Stella Kramrisch.

- Rian; et al. (2007). "Fractal geometry as the synthesis of Hindu cosmology in Kandariya Mahadev temple, Khajuraho". Building and Environment. 42 (12): 4093–4107. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2007.01.028.

- Stella Kramrisch (1976), The Hindu Temple, Volume 1, ISBN 81-208-0223-3

- Datta and Beynon (2011), "Early Connections: Reflections on the canonical lineage of Southeast Asian temples", in EAAC 2011: South of East Asia: Re-addressing East Asian Architecture and Urbanism: Proceedings of the East Asian Architectural Culture International Conference, Department of Architecture, National University of Singapore, Singapore, pp. 1-17

- V.S. Pramar, Some Evidence on the Wooden Origins of the Vāstupuruṣamaṇḍala,Artibus Asiae, Vol. 46, No. 4 (1985), pp. 305-311.

- This concept has equivalence to the concept of Acintya, or Sang Hyang Widhi Wasa, in Balinese Hindu temples; elsewhere it has been referred to as satcitananda

- Stella Kramrisch (1976), The Hindu Temple, Vol. 1, ISBN 81-208-0223-3, p. 8.

- Meister, Michael W. (March 2006). "Mountain Temples and Temple-Mountains: Masrur". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 65 (1): 26–49. doi:10.2307/25068237. JSTOR 25068237.

- Trivedi, K. (1989). "Hindu temples: models of a fractal universe." The Visual Computer, 5(4), 243-258