Documentary hypothesis

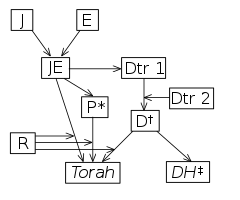

The documentary hypothesis (DH) is one of the models used by biblical scholars to explain the origins and composition of the Torah (or Pentateuch, the first five books of the Bible: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy).[4] A version of the documentary hypothesis, frequently identified with the German scholar Julius Wellhausen, was almost universally accepted for most of the 20th century.[5] It posited that the Pentateuch is a compilation of four originally independent documents: the Jahwist (J), Elohist (E), Deuteronomist (D), and Priestly (P) sources. The first of these, J, was dated to the Solomonic period (c. 950 BCE).[1] E was dated somewhat later, in the 9th century BCE, and D was dated just before the reign of King Josiah, in the 7th or 8th century. Finally, P was generally dated to the time of Ezra in the 5th century BCE.[3][2] The sources would have been joined together at various points in time by a series of editors or "redactors."[6]

- J: Yahwist (10th–9th century BCE)[1][2]

- E: Elohist (9th century BCE)[1]

- Dtr1: early (7th century BCE) Deuteronomist historian

- Dtr2: later (6th century BCE) Deuteronomist historian

- P*: Priestly (6th–5th century BCE)[3][2]

- D†: Deuteronomist

- R: redactor

- DH: Deuteronomistic history (books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings)

The consensus around the classical documentary hypothesis has now collapsed.[5] This was triggered in large part by the influential publications of John Van Seters, Hans Heinrich Schmid, and Rolf Rendtorff in the mid-1970s.[7] These "revisionist" authors argued that J was to be dated no earlier than the time of the Babylonian captivity (597–539 BCE),[8] and rejected the existence of a substantial E source.[9] They also called into question the nature and extent of the three other sources. Van Seters, Schmid, and Rendtorff shared many of the same criticisms of the documentary hypothesis, but were not in complete agreement about what paradigm ought to replace it.[7] As a result, there has been a revival of interest in "fragmentary" and "supplementary" models, frequently in combination with each other and with a documentary model, making it difficult to classify contemporary theories as strictly one or another.[10] Modern scholars also have given up the classical Wellhausian dating of the sources, and generally see the completed Torah as a product of the time of the Persian Achaemenid Empire (probably 450–350 BCE), although some would place its production as late as the Hellenistic period (333–164 BCE), after the conquests of Alexander the Great.[11]

History of the documentary hypothesis

The Torah (or Pentateuch) is collectively the first five books of the Bible: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy.[12] According to tradition they were dictated by God to Moses,[13] but when modern critical scholarship began to be applied to the Bible it was discovered that the Pentateuch was not the unified text one would expect from a single author.[14] As a result, the Mosaic authorship of the Torah had been largely rejected by leading scholars by the 17th century, with many modern scholars viewing it as a product of a long evolutionary process.[15][16][Note 1]

In the mid-18th century, some scholars started a critical study of doublets (parallel accounts of the same incidents), inconsistencies, and changes in style and vocabulary in the Torah.[15] In 1780 Johann Eichhorn, building on the work of the French doctor and exegete Jean Astruc's "Conjectures" and others, formulated the "older documentary hypothesis": the idea that Genesis was composed by combining two identifiable sources, the Jehovist ("J"; also called the Yahwist) and the Elohist ("E").[17] These sources were subsequently found to run through the first four books of the Torah, and the number was later expanded to three when Wilhelm de Wette identified the Deuteronomist as an additional source found only in Deuteronomy ("D").[18] Later still the Elohist was split into Elohist and Priestly ("P") sources, increasing the number to four.[19]

These documentary approaches were in competition with two other models, the fragmentary and the supplementary.[20] The fragmentary hypothesis argued that fragments of varying lengths, rather than continuous documents, lay behind the Torah; this approach accounted for the Torah's diversity but could not account for its structural consistency, particularly regarding chronology.[21] The supplementary hypothesis was better able to explain this unity: it maintained that the Torah was made up of a central core document, the Elohist, supplemented by fragments taken from many sources.[21] The supplementary approach was dominant by the early 1860s, but it was challenged by an important book published by Hermann Hupfeld in 1853, who argued that the Pentateuch was made up of four documentary sources, the Priestly, Yahwist, and Elohist intertwined in Genesis-Exodus-Leviticus-Numbers, and the stand-alone source of Deuteronomy.[22] At around the same period Karl Heinrich Graf argued that the Yahwist and Elohist were the earliest sources and the Priestly source the latest, while Wilhelm Vatke linked the four to an evolutionary framework, the Yahwist and Elohist to a time of primitive nature and fertility cults, the Deuteronomist to the ethical religion of the Hebrew prophets, and the Priestly source to a form of religion dominated by ritual, sacrifice and law.[23]

Wellhausen and the new documentary hypothesis

In 1878 Julius Wellhausen published Geschichte Israels, Bd 1 ("History of Israel, Vol 1").[24] The second edition was printed as Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels ("Prolegomena to the History of Israel"), in 1883,[25] and the work is better known under that name.[26] (The second volume, a synthetic history titled Israelitische und jüdische Geschichte ["Israelite and Jewish History"],[27] did not appear until 1894 and remains untranslated.) Crucially, this historical portrait was based upon two earlier works of his technical analysis: "Die Composition des Hexateuchs" ("The Composition of the Hexateuch") of 1876/77 and sections on the "historical books" (Judges–Kings) in his 1878 edition of Friedrich Bleek's Einleitung in das Alte Testament ("Introduction to the Old Testament").

Wellhausen's documentary hypothesis owed little to Wellhausen himself but was mainly the work of Hupfeld, Eduard Eugène Reuss, Graf, and others, who in turn had built on earlier scholarship.[28] He accepted Hupfeld's four sources and, in agreement with Graf, placed the Priestly work last.[19] J was the earliest document, a product of the 10th century BCE and the court of Solomon; E was from the 9th century in the northern Kingdom of Israel, and had been combined by a redactor (editor) with J to form a document JE; D, the third source, was a product of the 7th century BCE, by 620 BCE, during the reign of King Josiah; P (what Wellhausen first named "Q") was a product of the priest-and-temple dominated world of the 6th century; and the final redaction, when P was combined with JED to produce the Torah as we now know it.[29][30]

Wellhausen's explanation of the formation of the Torah was also an explanation of the religious history of Israel.[30] The Yahwist and Elohist described a primitive, spontaneous and personal world, in keeping with the earliest stage of Israel's history; in Deuteronomy he saw the influence of the prophets and the development of an ethical outlook, which he felt represented the pinnacle of Jewish religion; and the Priestly source reflected the rigid, ritualistic world of the priest-dominated post-exilic period.[31] His work, notable for its detailed and wide-ranging scholarship and close argument, entrenched the "new documentary hypothesis" as the dominant explanation of Pentateuchal origins from the late 19th to the late 20th centuries.[19][Note 2]

Critical reassessment

In the mid to late 20th century new criticism of the documentary hypothesis formed.[5] Three major publications of the 1970s caused scholars to reevaluate the assumptions of the documentary hypothesis: Abraham in History and Tradition by John Van Seters, Der sogenannte Jahwist ("The So-Called Yahwist") by Hans Heinrich Schmid, and Das überlieferungsgeschichtliche Problem des Pentateuch ("The Tradition-Historical Problem of the Pentateuch") by Rolf Rendtorff. These three authors shared many of the same criticisms of the documentary hypothesis, but were not in agreement about what paradigm ought to replace it.[7]

Van Seters and Schmid both forcefully argued that the Yahwist source could not be dated to the Solomonic period (c. 950 BCE) as posited by the documentary hypothesis. They instead dated J to the period of the Babylonian captivity (597–539 BCE), or the late monarchic period at the earliest.[8] Van Seters also sharply criticized the idea of a substantial Elohist source, arguing that E extends at most to two short passages in Genesis.[32]

Some scholars, following Rendtorff, have come to espouse a fragmentary hypothesis, in which the Pentateuch is seen as a compilation of short, independent narratives, which were gradually brought together into larger units in two editorial phases: the Deuteronomic and the Priestly phases.[33][34][35] By contrast, scholars such as John Van Seters advocate a supplementary hypothesis, which posits that the Torah is the result of two major additions—Yahwist and Priestly—to an existing corpus of work.[36]

Some scholars use these newer hypotheses in combination with each other and with a documentary model, making it difficult to classify contemporary theories as strictly one or another.[10] The majority of scholars today continue to recognise Deuteronomy as a source, with its origin in the law-code produced at the court of Josiah as described by De Wette, subsequently given a frame during the exile (the speeches and descriptions at the front and back of the code) to identify it as the words of Moses.[37] Most scholars also agree that some form of Priestly source existed, although its extent, especially its end-point, is uncertain.[38] The remainder is called collectively non-Priestly, a grouping which includes both pre-Priestly and post-Priestly material.[39]

The general trend in recent scholarship is to recognize the final form of the Torah as a literary and ideological unity, based on earlier sources, likely completed during the Persian period (539–333 BCE).[40][41] A minority of scholars would place its final compilation somewhat later, however, in the Hellenistic period (333–164 BCE).[42]

A revised neo-documentary hypothesis still has adherents, especially in North America and Israel.[43] This distinguishes sources by means of plot and continuity rather than stylistic and linguistic concerns, and does not tie them to stages in the evolution of Israel's religious history.[43] Its resurrection of an E source is probably the element most often criticised by other scholars, as it is rarely distinguishable from the classical J source and European scholars have largely rejected it as fragmentary or non-existent.[44]

The Torah and the history of Israel's religion

Wellhausen used the sources of the Torah as evidence of changes in the history of Israelite religion as it moved (in his opinion) from free, simple and natural to fixed, formal and institutional.[45] Modern scholars of Israel's religion have become much more circumspect in how they use the Old Testament, not least because many have concluded that the Bible is not a reliable witness to the religion of ancient Israel and Judah,[46] representing instead the beliefs of only a small segment of the ancient Israelite community centred in Jerusalem and devoted to the exclusive worship of the god Yahweh.[47][48]

See also

- Authorship of the Bible

- Biblical criticism

- Books of the Bible

- Dating the Bible

- Mosaic authorship

- Umberto Cassuto, Jewish scholar who was critical of the documentary hypothesis

- Q Source, a similar theory for the construction of the Synoptic Gospels

Notes

- The reasons behind the rejection are covered in more detail in the article on Mosaic authorship.

- The two-source hypothesis of Eichhorn was the "older" documentary hypothesis, and the four-source hypothesis adopted by Wellhausen was the "newer".

References

- Viviano 1999, p. 40.

- Gmirkin 2006, p. 4.

- Viviano 1999, p. 41.

- Patzia & Petrotta 2010, p. 37.

- Carr 2014, p. 434.

- Van Seters 2015, p. viii.

- Van Seters 2015, p. 41.

- Van Seters 2015, pp. 41–43.

- Carr 2014, p. 436.

- Van Seters 2015, p. 12.

- Greifenhagen 2003, pp. 206–207, 224 fn.49.

- McDermott 2002, p. 1.

- Kugel 2008, p. 6.

- Campbell & O'Brien 1993, p. 1.

- Berlin 1994, p. 113.

- Baden 2012, p. 13.

- Ruddick 1990, p. 246.

- Patrick 2013, p. 31.

- Barton & Muddiman 2010, p. 19.

- Viviano 1999, pp. 38–39.

- Viviano 1999, p. 38.

- Barton & Muddiman 2010, p. 18–19.

- Friedman 1997, p. 24–25.

- Wellhausen 1878.

- Wellhausen 1883.

- Kugel 2008, p. 41.

- Wellhausen 1894.

- Barton & Muddiman 2010, p. 20.

- Viviano 1999, p. 40–41.

- Gaines 2015, p. 260.

- Viviano 1999, p. 51.

- Van Seters 2015, p. 42.

- Viviano 1999, p. 49.

- Thompson 2000, p. 8.

- Ska 2014, pp. 133–135.

- Van Seters 2004, p. 77.

- Otto 2015, p. 605.

- Carr 2014, p. 457.

- Otto 2014, p. 609.

- Greifenhagen 2003, pp. 206–207.

- Whisenant 2010, p. 679, "Instead of a compilation of discrete sources collected and combined by a final redactor, the Pentateuch is seen as a sophisticated scribal composition in which diverse earlier traditions have been shaped into a coherent narrative presenting a creation-to-wilderness story of origins for the entity 'Israel.'"

- Greifenhagen 2003, pp. 206–207, 224 n. 49.

- Gaines 2015, p. 271.

- Gaines 2015, p. 272.

- Miller 2000, p. 182.

- Lupovitch, Howard N. (2010). "The world of the Hebrew Bible". Jews and Judaism in World History. Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 5–10. ISBN 978-0-203-86197-4.

- Stackert 2014, p. 24.

- Wright 2002, p. 52.

Bibliography

- Baden, Joel S. (2012). The Composition of the Pentateuch: Renewing the Documentary Hypothesis. Anchor Yale Reference Library. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15263-0.

- Barton, John (2014). "Biblical Scholarship on the European Continent, in the UK, and Ireland". In Saeboe, Magne; Ska, Jean Louis; Machinist, Peter (eds.). Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. III: From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Part II: The Twentieth Century – From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-54022-0.

- Barton, John; Muddiman, John (2010). The Pentateuch. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-958024-8.

- Berlin, Adele (1994). Poetics and Interpretation of Biblical Narrative. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-002-6.

- Bos, James M. (2013). Reconsidering the Date and Provenance of the Book of Hosea. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-567-06889-7.

- Brettler, Marc Zvi (2004). "Torah: Introduction". In Berlin, Adele; Brettler, Marc Zvi (eds.). The Jewish Study Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-529751-5.

The Jewish study Bible.

- Campbell, Antony F.; O'Brien, Mark A. (1993). Sources of the Pentateuch: Texts, Introductions, Annotations. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-4514-1367-0.

Sources of the Pentateuch: Texts, Introductions, Annotations.

- Carr, David M. (2007). "Genesis". In Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-528880-3.

- Carr, David M. (2014). "Changes in Pentateuchal Criticism". In Saeboe, Magne; Ska, Jean Louis; Machinist, Peter (eds.). Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. III: From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Part II: The Twentieth Century – From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-54022-0.

- Enns, Peter (2013). "3 Things I Would Like to See Evangelical Leaders Stop Saying about Biblical Scholarship". patheos.com.

- Frei, Peter (2001). "Persian Imperial Authorization: A Summary". In Watts, James (ed.). Persia and Torah: The Theory of Imperial Authorization of the Pentateuch. Atlanta, GA: SBL Press. p. 6. ISBN 9781589830158.

- Friedman, Richard Elliott (1997). Who Wrote the Bible?. HarperOne.

- Gaines, Jason M.H. (2015). The Poetic Priestly Source. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-5064-0046-4.

- Gertz, Jan C.; Levinson, Bernard M.; Rom-Shiloni, Dalit (2017). "Convergence and Divergence in Pentateuchal Theory". In Gertz, Jan C.; Levinson, Bernard M.; Rom-Shiloni, Dalit (eds.). The Formation of the Pentateuch: Bridging the Academic Cultures of Europe, Israel, and North America. Mohr Siebeck.

- Gmirkin, Russell (2006). Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-567-13439-4.

- Greifenhagen, Franz V. (2003). Egypt on the Pentateuch's Ideological Map. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-567-39136-0.

- Houston, Walter (2013). The Pentateuch. SCM Press. ISBN 978-0-334-04385-0.

- Kawashima, Robert S. (2010). "Sources and Redaction". In Hendel, Ronald (ed.). Reading Genesis. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-49278-2.

- Kratz, Reinhard G. (2013). "Rewriting Torah". In Schipper, Bernd; Teeter, D. Andrew (eds.). Wisdom and Torah: The Reception of 'Torah' in the Wisdom Literature of the Second Temple Period. BRILL. ISBN 9789004257368.

- Kratz, Reinhard G. (2005). The Composition of the Narrative Books of the Old Testament. A&C Black. ISBN 9780567089205.

- Kugel, James L. (2008). How to Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now. FreePress. ISBN 978-0-7432-3587-7.

- Kurtz, Paul Michael (2018). Kaiser, Christ, and Canaan: The Religion of Israel in Protestant Germany, 1871–1918. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-155496-4.

- Levin, Christoph (2013). Re-Reading the Scriptures. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-152207-9.

- McDermott, John J. (2002). Reading the Pentateuch: A Historical Introduction. Pauline Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-4082-4.

- McEntire, Mark (2008). Struggling with God: An Introduction to the Pentateuch. Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-88146-101-5.

- McKim, Donald K. (1996). Westminster Dictionary of Theological Terms. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 978-0-664-25511-4.

- Miller, Patrick D. (2000). Israelite Religion and Biblical Theology: Collected Essays. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-84127-142-2.

- Monroe, Lauren A.S. (2011). Josiah's Reform and the Dynamics of Defilement. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-977536-1.

- Moore, Megan Bishop; Kelle, Brad E. (2011). Biblical History and Israel's Past. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-6260-0.

- Nicholson, Ernest Wilson (2003). The Pentateuch in the Twentieth Century. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-925783-6.

- Otto, Eckart (2014). "The Study of Law and Ethics in the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament". In Saeboe, Magne; Ska, Jean Louis; Machinist, Peter (eds.). Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. III: From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Part II: The Twentieth Century – From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-54022-0.

- Patrick, Dale (2013). Deuteronomy. Chalice Press. ISBN 978-0-8272-0566-6.

- Patzia, Arthur G.; Petrotta, Anthony J. (2010). Pocket Dictionary of Biblical Studies. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-6702-8.

- Ruddick, Eddie L. (1990). "Elohist". In Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey (eds.). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-86554-373-7.

- Sharpes, Donald K. (2005). Lords of the Scrolls. Peter Lang. ISBN 0-300-15263-9.

- Ska, Jean-Louis (2006). Introduction to reading the Pentateuch. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575061221.

- Ska, Jean Louis (2014). "Questions of the 'History of Israel' in Recent Research". In Saeboe, Magne; Ska, Jean Louis; Machinist, Peter (eds.). Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. III: From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Part II: The Twentieth Century – From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-54022-0.

- Stackert, Jeffrey (2014). A Prophet Like Moses: Prophecy, Law, and Israelite Religion. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-933645-6.

- Thompson, Thomas L. (2000). Early History of the Israelite People: From the Written & Archaeological Sources. BRILL. ISBN 9004119434.

- Van Seters, John (2015). The Pentateuch: A Social-Science Commentary. Bloomsbury T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-65880-7.

- Viviano, Pauline A. (1999). "Source Criticism". In Haynes, Stephen R.; McKenzie, Steven L. (eds.). To Each Its Own Meaning: An Introduction to Biblical Criticisms and Their Application. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 978-0-664-25784-2.

- Wellhausen, Julius (1878). Geschichte Israels. Vol. 1. Berlin: Druck und Verlag von Georg Reimer.

- Wellhausen, Julius (1883). Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Berlin: Druck und Verlag von Georg Reimer. Project Gutenberg edition; full text at sacred-texts.com

- Wellhausen, Julius (1894). Israelitische und jüdische Geschichte. Vol. 2. Berlin: Druck und Verlag von Georg Reimer.

- Whisenant, Jessica (2010). "The Pentateuch as Torah: New Models for Understanding Its Promulgation and Acceptance by Gary N. Knoppers, Bernard M. Levinson". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 130 (4): 679–681. JSTOR 23044597.

- Wright, J. Edward (2002). The Early History of Heaven. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-534849-1.

External links

Media related to Documentary hypothesis at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Documentary hypothesis at Wikimedia Commons- Wikiversity – The King James Version according to the documentary hypothesis