Drowning

Drowning is a type of suffocation induced by the submersion of the mouth and nose in a liquid. Most instances of fatal drowning occur alone or in situations where others present are either unaware of the victim's situation or unable to offer assistance. After successful resuscitation, drowning victims may experience breathing problems, vomiting, confusion, or unconsciousness. Occasionally, victims may not begin experiencing these symptoms until several hours after they are rescued. An incident of drowning can also cause further complications for victims due to low body temperature, aspiration of vomit, or acute respiratory distress syndrome (respiratory failure from lung inflammation).

| Drowning | |

|---|---|

| |

| Vasily Perov: The Drowned, 1867 | |

| Specialty | Critical care medicine |

| Symptoms | Event: Often occurs silently with a person found unconscious[1][2] After rescue: Breathing problems, vomiting, confusion, unconsciousness[2][3] |

| Complications | Hypothermia, aspiration of vomit into lungs, acute respiratory distress syndrome[4] |

| Usual onset | Rapid[3] |

| Risk factors | Alcohol use, epilepsy, low socioeconomic status, access to water,[5] cold water shock |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Suicide, seizure, murder, hypoglycemia, heart arrhythmia[2] |

| Prevention | Fencing pools, teaching children to swim, safe boating practices[6][5] |

| Treatment | Rescue breathing, CPR, mechanical ventilation[7] |

| Medication | Oxygen therapy, intravenous fluids, vasopressors[7] |

| Frequency | 4.5 million (2015)[8] |

| Deaths | 324,000 (2016)[6] |

Drowning is more likely to happen when spending extended periods of time near large bodies of water.[4][6] Risk factors for drowning include alcohol use, drug use, epilepsy, low socioeconomic status (which is often related to minimal or non-existent swimming skills), lack of training, and, in the case of children, a lack of supervision.[6] Common drowning locations include natural and man-made bodies of water, bathtubs, and swimming pools.[3][7]

Drowning occurs when an individual spends too much time with their nose and mouth submerged in a liquid to the point of being unable to breathe. If this is not followed by an exit to the surface, low oxygen levels and excess carbon dioxide in the blood trigger a neurological state of breathing emergency, which results in increased physical distress and occasional contractions of the vocal folds.[9] Significant amounts of water usually only enter the lungs later in the process.[4]

While the word "drowning" is commonly associated with fatal results, drowning may be classified into three different types: drowning that results in death, drowning that results in long-lasting health problems, and drowning that results in no health complications.[10] Sometimes the term "near-drowning" is used in the latter cases. Among children who survive, health problems occur in about 7.5% of cases.[7]

Steps to prevent drowning include teaching children and adults to swim and to recognise unsafe water conditions, never swimming alone, use of personal flotation devices on boats and when swimming in unfavourable conditions, limiting or removing access to water (such as with fencing of swimming pools), and exercising appropriate supervision.[6][5] Treatment of victims who are not breathing should begin with opening the airway and providing five breaths of mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.[7] Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is recommended for a person whose heart has stopped beating and has been underwater for less than an hour.[7]

Causes

A major contributor to drowning is the inability to swim. Other contributing factors include the state of the water itself, distance from a solid footing, physical impairment, or prior loss of consciousness. Anxiety brought on by fear of drowning or water itself can lead to exhaustion, thus increasing the chances of drowning.

Approximately 90% of drownings take place in freshwater (rivers, lakes, and a relatively small number of swimming pools); the remaining 10% take place in seawater.[11] Drownings in other fluids are rare and often related to industrial accidents.[12] In New Zealand's early colonial history, so many settlers died while trying to cross the rivers that drowning was called "the New Zealand death."[13]

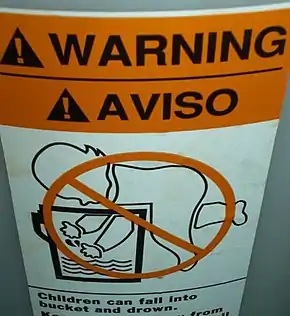

People have drowned in as little as 30 mm (1.2 in) of water while lying face down.[14] Children have drowned in baths, buckets, and toilets. People who are inebriated or otherwise intoxicated can drown in puddles.

Death can occur due to complications following an initial drowning. Inhaled fluid can act as an irritant inside the lungs. Even small quantities can cause the extrusion of liquid into the lungs (pulmonary edema) over the following hours; this reduces the ability to exchange the air and can lead to a person "drowning in their own body fluid." Vomit and certain poisonous vapors or gases (as in chemical warfare) can have a similar effect. The reaction can take place up to 72 hours after the initial incident and may lead to a serious injury or death.[15]

Risk Factors

Many behavioral and physical factors are related to drowning:[16][17]

- Drowning is the most common cause of death for people with seizure disorders, largely in bathtubs. Epileptics are more likely to die due to accidents such as drowning. However, this risk is especially elevated in low and middle-income countries compared to high-income countries.[18]

- The use of alcohol increases the risk of drowning across developed and developing nations. Alcohol is involved in approximately 50% of fatal drownings, and 35% of non-fatal drownings.[19]

- Inability to swim can lead to drowning. Participation in formal swimming lessons can reduce this risk. The optimal age to start the lessons is childhood, between one and four years of age.[20]

- Feeling overly tired reduces swimming performance. This exhaustion can be rapidly aggravated by anxious movements motivated by fear during or in anticipation of drowning. An overconfident appraisal of one's own physical capabilities can lead to "swimming out too far" and exhaustion before returning to solid footing.

- Free access to water can be hazardous, especially to young children. Barriers can prevent young children from gaining access to the water.

- Ineffective supervision, since drowning can occur anywhere there is water, even in the presence of lifeguards.

- Risk can vary with location depending on age. Children between one and four more commonly drown in home swimming pools than elsewhere. Drownings in natural water settings increase with age. More than half of drownings occur among those fifteen years and older occurred in natural water environments.[20]

- Familial or genetic history of sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) or sudden cardiac death (SCD) can predispose children to drown.[21] Extensive genetic testing and/or consultation with a cardiologist should be done especially when there is a high suspicion of familial history and/or clinical evidence of sudden cardiac arrest or sudden cardiac death.

- Individuals with undetected primary cardiac arrhythmias, as cold water immersion or aquatic exercise can induce these arrhythmias to occur.[22]

Population groups at risk in the US are generally the old and young.[16]

- Youth: drowning rates are highest for children under five years of age and people fifteen to twenty-four years of age.

- Males: nearly 80% of drowning victims are male.

- Minorities: the fatal unintentional drowning rate for African Americans above the age of 29 between 1999 and 2010 was significantly higher than that of white people above the age of 29.[23] The fatal drowning rate of African American children of ages from five to fourteen is almost three times that of white children in the same age range and 5.5 times higher in swimming pools. These disparities might be associated with a lack of basic swimming education in some minority populations.

Free-Diving

Some additional causes of drowning can also happen during freediving activities:

- Ascent blackout, also called deep water blackout, is caused by hypoxia during ascent from depth. The partial pressure of oxygen in the lungs under pressure at the bottom of a deep free dive is adequate to support consciousness but drops below the blackout threshold as the water pressure decreases on the ascent. It usually strikes upon arriving near the surface as the pressure approaches normal atmospheric pressure.[24]

- Shallow water blackout caused by hyperventilation prior to swimming or diving. The primary urge to breathe is triggered by rising carbon dioxide (CO2) levels in the bloodstream.[25] The body detects CO2 levels very accurately and relies on this to control breathing.[25] Hyperventilation reduces the carbon dioxide content of the blood but leaves the diver susceptible to a sudden loss of consciousness without warning from hypoxia. There is no bodily sensation that warns a diver of an impending blackout, and people (often capable swimmers swimming under the surface in shallow water) become unconscious and drown quietly without alerting anyone to the fact that there is a problem; they are typically found at the bottom.

Pathophysiology

Drowning can be considered as going through four stages:[26]

- Breath-hold under voluntary control until the urge to breathe due to hypercapnia becomes overwhelming

- Fluid is swallowed and/or aspirated into the airways

- Cerebral anoxia stops breathing and aspiration

- Cerebral injury due to anoxia becomes irreversible

Generally, in the early stages of drowning, a person holds their breath to prevent water from entering their lungs.[7] When this is no longer possible, a small amount of water entering the trachea causes a muscular spasm that seals the airway and prevents further passage of water.[7] If the process is not interrupted, loss of consciousness due to hypoxia is followed rapidly by cardiac arrest.

Oxygen Deprivation

A conscious person will hold their breath (see Apnea) and will try to access air, often resulting in panic, including rapid body movement. This uses up more oxygen in the bloodstream and reduces the time until unconsciousness. The person can voluntarily hold his or her breath for some time, but the breathing reflex will increase until the person tries to breathe, even when submerged.[27]

The breathing reflex in the human body is weakly related to the amount of oxygen in the blood but strongly related to the amount of carbon dioxide (see Hypercapnia). During an apnea, the oxygen in the body is used by the cells and excreted as carbon dioxide. Thus, the level of oxygen in the blood decreases, and the level of carbon dioxide increases. Increasing carbon dioxide levels lead to a stronger and stronger breathing reflex, up to the breath-hold breakpoint, at which the person can no longer voluntarily hold his or her breath. This typically occurs at an arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide of 55 mm Hg but may differ significantly between people.

The breath-hold breakpoint can be suppressed or delayed, either intentionally or unintentionally. Hyperventilation before any dive, deep or shallow, flushes out carbon dioxide in the blood resulting in a dive commencing with an abnormally low carbon dioxide level: a potentially dangerous condition known as hypocapnia. The level of carbon dioxide in the blood after hyperventilation may then be insufficient to trigger the breathing reflex later in the dive.

Following this, a blackout may occur before the diver feels an urgent need to breathe. This can occur at any depth and is common in distance breath-hold divers in swimming pools. Both deep and distance free divers often use hyperventilation to flush out carbon dioxide from the lungs to suppress the breathing reflex for longer. It is important not to mistake this for an attempt to increase the body's oxygen store. The body at rest is fully oxygenated by normal breathing and cannot take on any more. Breath-holding in water should always be supervised by a second person, as by hyperventilating, one increases the risk of shallow water blackout because insufficient carbon dioxide levels in the blood fail to trigger the breathing reflex.[28]

A continued lack of oxygen in the brain, hypoxia, will quickly render a person unconscious, usually around a blood partial pressure of oxygen of 25–30 mmHg.[28] An unconscious person rescued with an airway still sealed from laryngospasm stands a good chance of a full recovery. Artificial respiration is also much more effective without water in the lungs. At this point, the person stands a good chance of recovery if attended to within minutes.[28] More than 10% of drownings may involve laryngospasm, but the evidence suggests that it is not usually effective at preventing water from entering the trachea. The lack of water found in the lungs during autopsy does not necessarily mean there was no water at the time of drowning, as small amounts of freshwater are readily absorbed into the bloodstream. Hypercapnia and hypoxia both contribute to laryngeal relaxation, after which the airway is effectively open through the trachea. There is also bronchospasm and mucous production in the bronchi associated with laryngospasm, and these may prevent water entry at terminal relaxation.[29]

The hypoxemia and acidosis caused by asphyxia in drowning affect various organs. There can be central nervous system damage, cardiac arrhythmia, pulmonary injury, reperfusion injury, and multiple-organ secondary injury with prolonged tissue hypoxia.[30]

A lack of oxygen or chemical changes in the lungs may cause the heart to stop beating. This cardiac arrest stops the flow of blood and thus stops the transport of oxygen to the brain. Cardiac arrest used to be the traditional point of death, but at this point, there is still a chance of recovery. The brain cannot survive long without oxygen, and the continued lack of oxygen in the blood, combined with the cardiac arrest, will lead to the deterioration of brain cells, causing first brain damage and eventually brain death from which recovery is generally considered impossible. The brain will die after approximately six minutes without oxygen at normal body temperature, but hypothermia of the central nervous system may prolong this.[31]

The extent of central nervous system injury to a large extent determines the survival and long term consequences of drowning, In the case of children, most survivors are found within 2 minutes of immersion, and most fatalities are found after 10 minutes or more.[30]

Water Aspiration

If water enters the airways of a conscious person, the person will try to cough up the water or swallow it, often inhaling more water involuntarily.[32] When water enters the larynx or trachea, both conscious and unconscious people experience laryngospasm, in which the vocal cords constrict, sealing the airway. This prevents water from entering the lungs. Because of this laryngospasm, in the initial phase of drowning, water generally enters the stomach, and very little water enters the lungs. Though laryngospasm prevents water from entering the lungs, it also interferes with breathing. In most people, the laryngospasm relaxes sometime after unconsciousness, and water can then enter the lungs, causing a "wet drowning." However, about 7–10% of people maintain this seal until cardiac arrest.[27] This has been called "dry drowning", as no water enters the lungs. In forensic pathology, water in the lungs indicates that the person was still alive at the point of submersion. An absence of water in the lungs may be either a dry drowning or indicates a death before submersion.[33]

Aspirated water that reaches the alveoli destroys the pulmonary surfactant, which causes pulmonary edema and decreased lung compliance, compromising oxygenation in affected parts of the lungs. This is associated with metabolic acidosis, secondary fluid, and electrolyte shifts. During alveolar fluid exchange, diatoms present in the water may pass through the alveolar wall into the capillaries to be carried to internal organs. The presence of these diatoms may be diagnostic of drowning.

Of people who have survived drowning, almost one-third will experience complications such as acute lung injury (ALI) or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).[34] ALI/ARDS can be triggered by pneumonia, sepsis, and water aspiration. These conditions are life-threatening disorders that can result in death if not treated promptly.[34] During drowning, aspirated water enters the lung tissues, causes a reduction in alveolar surfactant, obstructs ventilation, and triggers a release of inflammatory mediators which ultimately results in hypoxia.[34] Specifically, upon reaching the alveoli, hypotonic liquid found in freshwater dilutes pulmonary surfactant, destroying the substance.[35] Comparatively, aspiration of hypertonic seawater draws liquid from the plasma into the alveoli and similarly causes damage to surfactant by disrupting the alveolar-capillary membrane.[35] Still, there is no clinical difference between salt and freshwater drowning. Once someone has reached definitive care, supportive care strategies such as mechanical ventilation can help to reduce the complications of ALI/ARDS.[34]

Whether a person drowns in freshwater or salt water makes no difference in respiratory management or its outcome.[36] People who drown in freshwater may experience worse hypoxemia early in their treatment, however, this initial difference is short-lived and the management of both fresh water and salt water drowning is essentially the same.[36]

Cold-Water Immersion

Submerging the face in water cooler than about 21 °C (70 °F) triggers the diving reflex, common to air-breathing vertebrates, especially marine mammals such as whales and seals. This reflex protects the body by putting it into energy-saving mode to maximise the time it can stay underwater. The strength of this reflex is greater in colder water and has three principal effects:[37]

- Bradycardia, a slowing of the heart rate to less than 60 beats per minute.[38]

- Peripheral vasoconstriction, the restriction of the blood flow to the extremities to increase the blood and oxygen supply to the vital organs, especially the brain.

- Blood shift, the shifting of blood to the thoracic cavity, the region of the chest between the diaphragm and the neck, to avoid the collapse of the lungs under higher pressure during deeper dives.

The reflex action is automatic and allows both a conscious and an unconscious person to survive longer without oxygen underwater than in a comparable situation on dry land. The exact mechanism for this effect has been debated and may be a result of brain cooling similar to the protective effects seen in people who are treated with deep hypothermia.[39][40]

The actual cause of death in cold or very cold water is usually lethal bodily reactions to increased heat loss and to freezing water, rather than any loss of core body temperature. Of those who die after plunging into freezing seas, around 20% die within 2 minutes from cold shock (uncontrolled rapid breathing and gasping causing water inhalation, a massive increase in blood pressure and cardiac strain leading to cardiac arrest, and panic), another 50% die within 15 – 30 minutes from cold incapacitation (loss of use and control of limbs and hands for swimming or gripping, as the body 'protectively' shuts down the peripheral muscles of the limbs to protect its core),[41] and exhaustion and unconsciousness cause drowning, claiming the rest within a similar time.[42] A notable example of this occurred during the sinking of the Titanic, in which most people who entered the −2 °C (28 °F) water died within 15–30 minutes.[43]

[S]omething that almost no one in the maritime industry understands. That includes mariners [and] even many (most) rescue professionals: It is impossible to die from hypothermia in cold water unless you are wearing flotation, because without flotation – you won’t live long enough to become hypothermic.

— Mario Vittone, lecturer and author in water rescue and survival[41]

Submersion into cold water can induce cardiac arrhythmias (abnormal heart rates) in healthy people, sometimes causing strong swimmers to drown.[44] The physiological effects caused by the diving reflex conflict with the body's cold shock response, which includes a gasp and uncontrollable hyperventilation leading to aspiration of water.[45] While breath-holding triggers a slower heart rate, cold shock activates tachycardia, an increase in heart rate.[44] It is thought that this conflict of these nervous system responses may account for the arrhythmias of cold water submersion.[44]

Heat transfers very well into water, and body heat is therefore lost extremely quickly in water compared to air,[46] even in merely 'cool' swimming waters around 70 °F (~20 °C).[42] A water temperature of 10 °C (50 °F) can lead to death in as little as one hour, and water temperatures hovering at freezing can lead to death in as little as 15 minutes.[42] This is because cold water can have other lethal effects on the body. Hence, hypothermia is not usually a reason for drowning or the clinical cause of death for those who drown in cold water.

Upon submersion into cold water, remaining calm and preventing loss of body heat is paramount.[47] While awaiting rescue, swimming or treading water should be limited to conserve energy, and the person should attempt to remove as much of the body from the water as possible; attaching oneself to a buoyant object can improve the chance of survival should unconsciousness occur.[47]

Hypothermia (and cardiac arrest) presents a risk for survivors of immersion. This risk increases if the survivor—feeling well again—tries to get up and move, not realizing their core body temperature is still very low and will take a long time to recover.

Most people who experience cold-water drowning do not develop hypothermia quickly enough to decrease cerebral metabolism before ischemia and irreversible hypoxia occur. The neuroprotective effects appear to require water temperatures below about 5 °C (41 °F).[48]

Diagnosis

The World Health Organization in 2005 defined drowning as "the process of experiencing respiratory impairment from submersion/immersion in liquid."[10] This definition does not imply death or even the necessity for medical treatment after removing the cause, nor that any fluid enters the lungs. The WHO further recommended that outcomes should be classified as death, morbidity, and no morbidity.[10] There was also consensus that the terms wet, dry, active, passive, silent, and secondary drowning should no longer be used.[10]

Experts differentiate between distress and drowning.

- Distress – people in trouble, but who can still float, signal for help, and take action.

- Drowning – people suffocating and in imminent danger of death within seconds.

Forensics

Forensic diagnosis of drowning is considered one of the most difficult in forensic medicine. External examination and autopsy findings are often non-specific, and the available laboratory tests are often inconclusive or controversial. The purpose of an investigation is generally to distinguish whether the death was due to immersion or whether the body was immersed postmortem. The mechanism in acute drowning is hypoxemia and irreversible cerebral anoxia due to submersion in liquid.

Drowning would be considered a possible cause of death if the body was recovered from a body of water, near a fluid that could plausibly have caused drowning, or found with the head immersed in a fluid. A medical diagnosis of death by drowning is generally made after other possible causes of death have been excluded by a complete autopsy and toxicology tests. Indications of drowning are seldom completely unambiguous and may include bloody froth in the airway, water in the stomach, cerebral edema and petrous or mastoid hemorrhage. Some evidence of immersion may be unrelated to the cause of death, and lacerations and abrasions may have occurred before or after immersion or death.[26]

Diatoms should normally never be present in human tissue unless water was aspirated. Their presence in tissues such as bone marrow suggests drowning; however, they are present in soil and the atmosphere, and samples may easily be contaminated. An absence of diatoms does not rule out drowning, as they are not always present in water.[26] A match of diatom shells to those found in the water may provide supporting evidence of the place of death. Drowning in saltwater can leave significantly different concentrations of sodium and chloride ions in the left and right chambers of the heart, but they will dissipate if the person survived for some time after the aspiration, or if CPR was attempted,[26] and have been described in other causes of death.

Most autopsy findings relate to asphyxia and are not specific to drowning. The signs of drowning are degraded by decomposition. Large amounts of froth will be present around the mouth and nostrils and in the upper and lower airways in freshly drowned bodies. The volume of froth is generally much greater in drowning than from other origins. Lung density may be higher than normal, but normal weights are possible after cardiac arrest or vasovagal reflex. The lungs may be overinflated and waterlogged, filling the thoracic cavity. The surface may have a marbled appearance, with darker areas associated with collapsed alveoli interspersed with paler aerated areas. Fluid trapped in the lower airways may block the passive collapse that is normal after death. Hemorrhagic bullae of emphysema may be found. These are related to the rupture of alveolar walls. These signs, while suggestive of drowning, are not conclusive.

Prevention

It is estimated that more than 85% of drownings could be prevented by supervision, training in water skills, technology, and public education.[50][32]

- Surveillance: Watching the swimmers is a basic task, because drownings can be silent and unnoticed: a person drowning may not always be able to attract attention, often because they have become unconscious. Surveillance of children is especially important. The highest rates of drowning globally are among children under five,[51] and young children should be supervised, regardless of whether they can already swim. The danger increases when they are alone. A baby can drown in the bathtub, in the toilet, and even in a small bucket filled with less than an inch of water. It only takes around 2 minutes underwater for an adult to lose consciousness, and only between 30 seconds and 2 minutes for a small child to die. Choosing supervised swimming places is safer. Many pools and bathing areas either have lifeguards or a pool safety camera system for local or remote monitoring, and some have computer-aided drowning detection. Bystanders are also important in detection of drownings and in notifying them (personally or by phone, alarm, etc.) to lifeguards, who may be unaware if distracted or busy.[52] Evidence shows that alarms in pools are poor for any utility.[7] The World Health Organization recommends analyzing when the most crowded hours in the swimming zones are, and to increase the number of lifeguards at those moments.

- Learning to swim: Being able to swim is one of the best defenses against drowning. It is recommended that children learn to swim in a safe and supervised environment when they are between 1 and 4 years old. Learning to swim is also possible in adults by using the same methods as children. It's still possible to drown even after learning to swim (because of the state of the water and other circumstances), so it's recommended to choose swimming places that are safe and kept under surveillance.

- Additional education: The WHO recommends training the general public in first-aid for the drowned, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and to behave safely when in the water. It is recommended to teach those who cannot swim to keep themselves away from deep waters.

- Pool fencing: Every private and public swimming pool should be fenced and enclosed on every side, so no person can access the water unsupervised.[53] The "Raffarin law", applied in France in 2003, forced the fencing of pools.[54]

.jpg.webp)

- Pool drains: Swimming pools often have drainage systems to cycle the water. Drains without covers can injure swimmers by trapping hair or other parts of the body, leading to immobilization and drowning. Drains should not suction too strongly. It is recommended for a pool to have many small drainage holes instead of a single large one. Periodic revisions are required to certify that the system is working well.

- Caution with certain conditions: Some conditions require one to be cautious when near water. For example, epilepsy and other seizure disorders may increase the possibility of drowning during a convulsion, making it more dangerous to swim, dive, and bathe. It is recommended that people with these conditions take showers rather than baths and are taught about the dangers of drowning.[55]

- Alcohol or drugs: Alcohol and drugs increase the probability of drowning. This danger is greater in bars near the water and parties on boats where alcohol is consumed. For example, Finland sees several drownings every year at Midsummer weekend as Finnish people spend more time in and around the lakes and beaches, often after having consumed alcohol.[56][57][58]

.jpg.webp)

- Lifejacket use: Children that cannot swim and other people at risk of drowning should wear a fastened and well-fitting lifejacket when near or in the water. Other flotation devices (inflatable inner tubes, water wings, foam tubes, etc.) may be useful, although they are usually considered toys.[50] Other flotation instruments are considered safe, like the professional circle-shaped lifebuoy (hoop-buoy, ring-buoy, life-ring, life-donut, lifesaver, or life preserver), which is mainly designed to be thrown, and some other professional variants that are used by lifeguards in their rescues.

- Depth awareness: Diving accidents in pools can cause serious injury. Up to 21% of shallow-water diving accidents can cause spinal injury, occasionally leading to death. Between 1.2% and 22% of all spinal injuries are from diving accidents. If the person does not die, the injury could cause permanent paralysis.[59]

- Avoid dangerous waters: Avoid swimming in waters that are too turbulent, where waves are large, with dangerous animals, or are too cold. Also avoid dragging currents, which are currents that are turbulent, foamy, and that can drag people or debris. If caught by one of these currents, swim out from it (it is possible to move out gradually, in a diagonal direction until you arrive at the shore).

- Navigating safely: Many people who die by drowning die in navigation accidents. Safe navigation practices include being informed of the state of the sea and equipping the boat with regulatory instruments to keep people afloat. These instruments are lifejackets (see 'lifejacket use' above) and professional lifebuoys with the shape of a circle (ring-buoy, hoop-buoy, life-ring, life-donut, lifesaver, or life preserver).

- Use the "buddy system": Don't swim alone, but with another person who can help in case of a problem.

- Rescue robots and drones: Nowadays, there exist some remote-controlled modern devices that can accomplish a water rescue. Floating rescue robots can move across the water, allowing the victim to hold on to the drone and be moved out of the water. Flying drones are very fast and can drop life jackets from air, and may help to locate the victim’s position.

- Follow the rules: Many people who drown fail follow the safety guidelines of the area. It is important to pay attention to the signage that indicates whether swimming is allowed or if a lifeguard is on duty. (lifeguards, coastguards, etc.)

Water Safety

The concept of water safety involves the procedures and policies that are directed to prevent people from drowning or from becoming injured in water.[60]

Time limits

The time a person can safely stay underwater depends on many factors, including energy consumption, number of prior breaths, physical condition, and age. An average person can last between one and three minutes before falling unconscious[30] and around ten minutes before dying.[61][30][31] In an unusual case, a person was resuscitated after 65 minutes underwater.[62]

Management

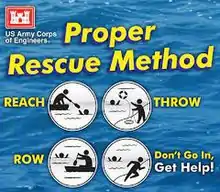

Rescue

When a person is drowning or a swimmer becomes missing, a fast water rescue may become necessary to take that person out of the water as soon as possible. Drowning is not necessarily violent or loud, with splashing and cries; it can be silent.[63]

Rescuers should avoid endangering themselves unnecessarily; whenever it is possible, they should assist from a safe ground position,[32] such as a boat, a pier, or any patch of land near the victim. The fastest way to assist is to throw a buoyant object (such as a lifebuoy). It is very important to avoid aiming directly at the victim, since even the lightest lifebuoys weight over 2 kilograms, and can stun, injure or even render a person unconscious if they impact on the head.[64] Alternatively, one could try to pull the victim out of the water by holding out an object to grasp. Some examples include: ropes, oars, poles, one's own arm, a hand, etc. This carries the risk of the rescuer being pulled into the water by the victim, so the rescuer must take a firm stand, lying down, as well as securing to some stable point. Alternatively, there are modern flying drones that drop life jackets.

Bystanders should immediately call for help. A lifeguard should be called, if present. If not, emergency medical services and paramedics should be contacted as soon as possible. Less than 6% of people rescued by lifeguards need medical attention, and only 0.5% need CPR. The statistics worsen when rescues are made by bystanders.

.jpg.webp)

If lifeguards or paramedics are unable to be called, bystanders must rescue the drowning person. Alternatively, there are small floating robots that can reach the victim, as human rescue carries a risk for the rescuer, who could be drowned.[65][66][67] Death of the would-be rescuer can happen because of the water conditions, the instinctive drowning response of the victim, the physical effort, and other problems.

After reaching the victim, first contact made by the rescuer is important. A drowning person in distress is likely to cling to the rescuer in an attempt to stay above the water surface, which could submerge the rescuer in the process. To avoid this, it is recommended that the rescuer approaches the panicking person with a buoyant object or extending a hand, so the victim has something to grasp. It can even be appropriate to approach from behind, taking one of the victim's arms, and pressing it against the victim's back to restrict unnecessary movement. Communication is also important.

If the victim clings to the rescuer and the rescuer cannot control the situation, a possibility is to dive underwater (as drowning people tend to move in the opposite direction, seeking the water surface) and consider a different approach to help the drowning victim.

It is possible that the victim has already sunk beneath the water surface. If this has happened, the rescue requires caution, as the victim could be conscious and cling to the rescuer underwater. The rescuer must bring the victim to the surface by grabbing either (or both) of the victim's arms and swimming upward, which may entice the victim to travel in the same direction, thus making the task easier, especially in the case of an unconscious victim. Should the victim be located in deeper waters (or simply complicates matters too much) the rescuer should dive, take the victim from behind, and ascend vertically to the water surface holding the victim.

After a successful contact with the victim, any ballast (such as weight belt) should be discarded.

Finally, the victim must be taken out of the water, which is achieved by a towing maneuver. This is commonly done placing the victim body in a face-up horizontal position, passing one hand under the victim's armpit to then grab the jaw with it, and towing by swimming backwards. The victim's mouth and nose must be kept above the water surface.

If the person is cooperative, the towing may be done in a similar fashion with the hands going under the victim's armpits. Other styles of towing are possible, but all of them keeping the victim's mouth and nose above the water.

Unconscious people may be pulled in an easier way: pulling on a wrist or on the shirt while they are in a face-up horizontal position. Victims with suspected spinal injuries can require a more specific grip and special care, and a backboard (spinal board) may be needed for their rescue.[68]

For unconscious people, an in-water resuscitation could increase the chances of survival by a factor of about three, but this procedure requires both medical and swimming skills, and it becomes impractical to send anyone besides the rescuer to execute that task. Chest compressions require a suitable platform, so an in-water assessment of circulation is pointless. If the person does not respond after a few breaths, cardiac arrest may be assumed, and getting them out of the water becomes a priority.[32]

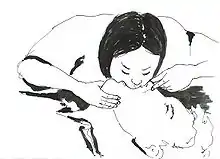

First Aid

The checks for responsiveness and breathing are carried out with the person horizontally supine. If unconscious but breathing, the recovery position is appropriate.

If not breathing, rescue ventilation is necessary. Drowning can produce a gasping pattern of apnea while the heart is still beating, and ventilation alone may be sufficient. The airway-breathing-circulation (ABC) sequence should be followed, rather than starting with compressions as is typical in cardiac arrest,[69] because the basic problem is lack of oxygen. If the victim is not a baby, it is recommended to start with 5 normal rescue breaths, as the initial ventilation may be difficult because of water in the airways, which can interfere with effective alveolar inflation. Thereafter, a continual sequence of 2 rescue breaths and 30 chest compressions is applied. This alternation is repeated until vital signs are re-established, the rescuers are unable to continue, or advanced life support is available.[32]

For babies (very small sized infants), the procedure is slightly modified. In each sequence of rescue breaths (the 5 initial breaths, and the further series of 2 breaths), the rescuer's mouth covers the baby's mouth and nose simultaneously (because a baby's face is too small). Besides, the intercalated series of 30 chest compressions are applied by pressing with only two fingers (due to the body of the babies is more fragile) on the chest bone (approximately on the lower part).

Attempts to actively expel water from the airway by abdominal thrusts, Heimlich maneuver or positioning head downwards should be avoided as there is no obstruction by solids, and they delay the start of ventilation and increase the risk of vomiting, with a significantly increased risk of death, as the aspiration of stomach contents is a common complication of resuscitation efforts.[32][70]

Treatment for hypothermia may also be necessary. However, in those who are unconscious, it is recommended their temperature not be increased above 34 degrees C.[71] Because of the diving reflex, people submerged in cold water and apparently drowned may revive after a relatively long period of immersion.[72] Rescuers retrieving a child from water significantly below body temperature should attempt resuscitation even after protracted immersion.[72]

Medical Care

People with a near-drowning experience who have normal oxygen levels and no respiratory symptoms should be observed in a hospital environment for a period of time to ensure there are no delayed complications.[73] The target of ventilation is to achieve 92% to 96% arterial saturation and adequate chest rise. Positive end-expiratory pressure will generally improve oxygenation. Drug administration via peripheral veins is preferred over endotracheal administration. Hypotension remaining after oxygenation may be treated by rapid crystalloid infusion.[32] Cardiac arrest in drowning usually presents as asystole or pulseless electrical activity. Ventricular fibrillation is more likely to be associated with complications of pre-existing coronary artery disease, severe hypothermia, or the use of epinephrine or norepinephrine.[32]

While surfactant may be used, no high-quality evidence exist that looks at this practice.[3] Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation may be used in those who cannot be oxygenated otherwise.[3] Steroids are not recommended.[3]

Prognosis

| Drowning outcomes (after hospital treatment) | |

|---|---|

| Duration of submersion | Risk of death or poor outcomes[32] |

| 0–5 min | 10% |

| 6–10 min | 56% |

| 11–25 min | 88% |

| >25 min | nearly 100% |

| Signs of brain-stem injury predict death or severe neurological consequences | |

People who have drowned who arrive at a hospital with spontaneous circulation and breathing usually recover with good outcomes.[72] Early provision of basic and advanced life support improve the probability of a positive outcome.[32]

A longer duration of submersion is associated with a lower probability of survival and a higher probability of permanent neurological damage.[72]

Contaminants in the water can cause bronchospasm and impaired gas exchange and can cause secondary infection with delayed severe respiratory compromise.[72]

Low water temperature can cause ventricular fibrillation, but hypothermia during immersion can also slow the metabolism, allowing longer hypoxia before severe damage occurs.[72] Hypothermia that reduces brain temperature significantly can improve the outcome. A reduction of brain temperature by 10 °C decreases ATP consumption by approximately 50%, which can double the time the brain can survive.[32]

The younger the person, the better the chances of survival.[72] In one case, a child submerged in cold (37 °F (3 °C)) water for 66 minutes was resuscitated without apparent neurological damage.[72] However, over the long term significant deficits were noted, including a range of cognitive difficulties, particularly general memory impairment, although recent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetoencephalography (MEG) were within normal range.[74]

Children

Drowning is a major worldwide cause of death and injury in children. An estimate of about 20% of non-fatal drowning victims may result in varying degrees of ischemic and/or hypoxic brain injury. Hypoxic injuries refers to a lack or absence of oxygen in certain organs or tissues. Ischemic injuries on the other hand refers inadequate blood supply to certain organs or part of the body. These injuries can lead to an increased risk of long-term morbidity.[75] Prolonged hypothermia and hypoxemia from nonfatal submersion drowning can result in cardiac dysrhythmias such as ventricular fibrillation, sinus bradycardia, or atrial fibrillation.[76] Long-term neurological outcomes of drowning cannot be predicted accurately during the early stages of treatment. Although survival after long submersion times, mostly by young children, has been reported, many survivors will remain severely and permanently neurologically compromised after much shorter submersion times. Factors affecting the probability of long-term recovery with mild deficits or full function in young children include the duration of submersion, whether advanced life support was needed at the accident site, the duration of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and whether spontaneous breathing and circulation are present on arrival at the emergency room.[77] Prolonged submersion in water for more than 5–10 minutes usually leads to poorer prognosis.[78]

Data on the long-term outcome are scarce and unreliable. Neurological examination at the time of discharge from the hospital does not accurately predict long-term outcomes. Some people with severe brain injury who were transferred to other institutions died months or years after the drowning and are recorded as survivors. Nonfatal drownings have been estimated as two to four times more frequent than fatal drownings.[77]

Long-Term Effects of Drowning in Children

Long-term effects of nonfatal drowning mainly include damage to major organs such as the brain, lungs, and kidneys. Prolonged submersion time is highly attributed to hypoxic ischemic brain injury in susceptible areas of the brain such as the hippocampus, insular cortex, and/or basal ganglia. Severity in hypoxic ischemic damage of these brain structures corresponds to the severity in global damage to areas of the cerebral cortex.[79] The cerebral cortex is a brain structure that is responsible for language, memory, learning, emotion, intelligence, and personality.[80] Global damage to the cerebral cortex can affect one or more of its primary function. Treatment of pulmonary complication from drowning is highly dependent on the amount of lung injury that occurred during the incident. These lung injuries can be contributed by water aspiration and also irritants present in the water such as microbial pathogens leading to complications such as lung infection that can develop in adult respiratory disease syndrome later on in life.[81] Some literature suggests that occurrences of drowning can lead to acute kidney injury from lack of blood flow and oxygenation due to shock and global hypoxia. These kidney injury can cause irreversible damage to the kidneys and may require long-term treatment such as renal replacement therapy.[82]

Infant Risk

Children are overrepresented in drowning statistics, with children aged 0–4 years old having the highest number of deaths due to unintentional downing.[83] In 2019 alone, 32,070 children between the ages 1–4 years old died as a result of unintentional drowning, equating to an age-adjusted fatality of 6.04 per 100,000 children.[83] Infants are particularly vulnerable because while their mobility develops quickly, their perception concerning their ability for locomotion between surfaces develops slower.[83] An infant can have full control of their movements, but simply won't recognize that water does not provide the same support for crawling as hardwood floors would. An infant’s capacity for movement needs to be met with an appropriate perception of surfaces of support (and avoidance of surfaces that do not support locomotion) to avoid drowning.[83] By crawling and interacting with their environment, infants learn to distinguish surfaces offering support for locomotion from those that do not, and their perception of surface characteristics will improve, as well as their perception of falls risk, over several weeks.[83]

Epidemiology

In 2019 alone, roughly 236,000 people died from drowning, thereby causing it to be the third leading cause of unintentional death globally trailing only traffic injuries and falls.[85][86]

In many countries, drowning is one of the main causes of preventable death for children under 12 years old. In the United States in 2006, 1100 people under 20 years of age died from drowning.[87] The United Kingdom has 450 drownings per year, or 1 per 150,000, whereas in the United States, there are about 6,500 drownings yearly, around 1 per 50,000. In Asia suffocation and drowning were the leading causes of preventable death for children under five years of age;[88][89] a 2008 report by UNICEF found that in Bangladesh, for instance, 46 children drown each day.[90]

Due to a generally increased likelihood for risk-taking, males are four times more likely to have submersion injuries.[91]

In the fishing industry, the largest group of drownings is associated with vessel disasters in bad weather, followed by man-overboard incidents and boarding accidents at night, either in foreign ports or under the influence of alcohol.[91] Scuba diving deaths are estimated at 700 to 800 per year, associated with inadequate training and experience, exhaustion, panic, carelessness, and barotrauma.[91]

South Asia

Deaths due to drowning is high in the South Asian region with India, China, Pakistan and Bangladesh accounting for up to 52% of the global deaths.[92] Death due to drowning is known to be high in the Sundarbans region in West Bengal and in Bihar.[93][94]

According to Daily Times in rural Pakistan while boats are preferred mode of transport where available same time, due to influence of female modesty culture in Pakistan generally women are not encouraged in swimming; in a 2022 July tragedy at Sadiqabad when a boat carrying 100 people capsized in Indus river, many could rescue themselves but 19 women were confirmed dead by drowning since they could not save themselves by swimming.[95]

Africa

In lower income countries, cases of drowning and deaths caused by drowning are under reported and data collection is limited.[96] In spite of this, many low-income countries in Africa still exhibit some of the highest rates of drowning, with incidence rates calculated from population based studies across 15 different countries (Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Malawi, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Nigeria, Ghana, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Guinea, Cote d'Ivoire, and the Gambia) ranging from 0.33 per 100,000 population to 502 per 100,000 population.[97] Potential risk factors include young age, male gender, having to commute across or work on the water (e.g. Fishermen), quality and carrying capacity of the boat, and poor weather.[97]

United States

In the United States, drowning is the second leading cause of death (after motor vehicle accidents) in children 12 and younger.[98]

People who drown are more likely to be male, young, or adolescent.[98] There is a racial disparity found in drowning incidents. According to CDC data collected from 1999 to 2019, drowning rates among Native Americans was 2 times higher than non-Hispanic whites while the rate among African-Americans was 1.5 times higher.[99][100] Surveys indicate that 10% of children under 5 have experienced a situation with a high risk of drowning. Worldwide, about 175,000 children die through drowning every year.[101] The causes of drowning cases in the US from 1999 to 2006 were as follows:

| 31.0% | Drowning and submersion while in natural water |

| 27.9% | Unspecified drowning and submersion |

| 14.5% | Drowning and submersion while in swimming pool |

| 9.4% | Drowning and submersion while in bathtub |

| 7.2% | Drowning and submersion following fall into natural water |

| 6.3% | Other specified drowning and submersion |

| 2.9% | Drowning and submersion following fall into swimming pool |

| 0.9% | Drowning and submersion following fall into bathtub |

According to the US National Safety Council, 353 people ages 5 to 24 drowned in 2017.[102]

Society and culture

Old Terminology

The word "drowning"—like "electrocution"—was previously used to describe fatal events only. Occasionally, that usage is still insisted upon, though the medical community's consensus supports the definition used in this article. Several terms related to drowning which have been used in the past are also no longer recommended.[7] These include:

- Active drowning: people, such as non-swimmers and the exhausted or hypothermic at the surface, who are unable to hold their mouth above water and are suffocating due to lack of air. Instinctively, people in such cases perform well-known behaviors in the last 20–60 seconds before being submerged, representing the body's last efforts to obtain air.[10][32] Notably, such people are unable to call for help, talk, reach for rescue equipment, or alert swimmers even feet away, and they may drown quickly and silently close to other swimmers or safety.[10]

- Dry drowning: drowning in which no water enters the lungs.[10][32]

- Near drowning: drowning which is not fatal.[10][32]

- Wet drowning: drowning in which water enters the lungs.[10][32]

- Passive drowning: people who suddenly sink or have sunk due to a change in their circumstances. Examples include people who drown in an accident due to sudden loss of consciousness or sudden medical condition.[32]

- Secondary drowning: physiological response to foreign matter in the lungs due to drowning causing extrusion of liquid into the lungs (pulmonary edema) which adversely affects breathing.[10][32]

- Silent drowning: drowning without a noticeable external display of distress.[10][103]

Dry Drowning

Dry drowning is a term that has never had an accepted medical definition and that is currently medically discredited.[104][105] Following the 2002 World Congress on Drowning in Amsterdam, a consensus definition of drowning was established: it is the "process of experiencing respiratory impairment from submersion/immersion in liquid."[106] This definition resulted in only three legitimate drowning subsets: fatal drowning, non-fatal drowning with illness/injury, and non-fatal drowning without illness/injury.[107] In response, major medical consensus organizations have adopted this definition worldwide and have officially discouraged any medical or publication use of the term "dry drowning".[104] Such organizations include the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation,[108] the Wilderness Medical Society,[47] the American Heart Association,[109] the Utstein Style system,[108] the International Lifesaving Federation,[110] the International Conference on Drowning,[106] Starfish Aquatics Institute,[111] the American Red Cross,[112] the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),[113][114][115] the World Health Organization[116] and the American College of Emergency Physicians.[117]

Drowning experts have recognized that the resulting pathophysiology of hypoxemia, acidemia, and eventual death is the same whether water entered the lung or not. As this distinction does not change management or prognosis but causes significant confusion due to alternate definitions and misunderstandings, it is generally established that pathophysiological discussions of "dry" versus "wet" drowning are not relevant to drowning care.[118]

"Dry drowning" is frequently cited in the news with a wide variety of definitions.[119] and is often confused with the equally inappropriate and discredited term "secondary drowning" or "delayed drowning".[120] Various conditions including spontaneous pneumothorax, chemical pneumonitis, bacterial or viral pneumonia, head injury, asthma, heart attack, and chest trauma have been misattributed to the erroneous terms "delayed drowning," "secondary drowning," and "dry drowning." Currently, there has never been a case identified in the medical literature where a person was observed to be without symptoms and who died hours or days later as a direct result of drowning alone.[104]

Capital Punishment

In Europe, drowning was used as capital punishment. During the Middle Ages, a sentence of death was read using the words cum fossa et furca, or "with pit and gallows".[121]

Drowning survived as a method of execution in Europe until the 17th and 18th centuries.[122] England had abolished the practice by 1623, Scotland by 1685, Switzerland in 1652, Austria in 1776, Iceland in 1777, and Russia by the beginning of the 1800s. France revived the practice during the French Revolution (1789–1799) and it was carried out by Jean-Baptiste Carrier at Nantes.[123]

References

- "Drowning". CDC. 15 September 2017. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- Ferri, Fred F. (2017). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2018 E-Book: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 404. ISBN 9780323529570.

- "Drowning - Injuries; Poisoning - Merck Manuals Professional Edition". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. September 2017. Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- Handley, AJ (16 April 2014). "Drowning". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 348: g1734. doi:10.1136/bmj.g1734. PMID 24740929. S2CID 220103200.

- Preventing drowning: an implementation guide (PDF). WHO. 2015. p. 2. ISBN 978-92-4-151193-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 October 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- "Drowning". WHO. 2020. Archived from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- Mott, TF; Latimer, KM (1 April 2016). "Prevention and Treatment of Drowning". American Family Physician. 93 (7): 576–82. PMID 27035042.

- GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- North, Robert (December 2002). "The pathophysiology of drowning". South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society Journal. Archived from the original on 14 March 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- van Beeck, EF; Branche, CM; Szpilman, D; Modell, JH; Bierens, JJ (November 2005). "A new definition of drowning: towards documentation and prevention of a global public health problem". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 83 (11): 853–6. PMC 2626470. PMID 16302042.

- Handley, Anthony J. (16 April 2014). "Drowning". BMJ. 348: bmj.g1734. doi:10.1136/bmj.g1734. ISSN 0959-8138. PMID 24740929. S2CID 220103200. Archived from the original on 5 March 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- "Accident Search Results Page". Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- Young, David (13 July 2012). "Rivers - The impact of European settlement". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 2 June 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- Gulli, Benjamin; Ciatolla, Joseph A.; Barnes, Leaugeay (2011). Emergency Care and Transportation of the Sick and Injured. Sudbury, Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett. p. 1157. ISBN 9780763778286. Archived from the original on 25 November 2017.

- Clarke, E. B.; Niggemann, E. H. (November 1975). "Near-drowning". Heart & Lung: The Journal of Critical Care. 4 (6): 946–955. ISSN 0147-9563. PMID 1042029. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2020 – via PubMed.

- Staff (23 September 2014). "Drowning". CDC Tip sheets. Atlanta. Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- Staff (28 April 2016). "Unintentional Drowning: Get the Facts". Home and Recreational Safety. Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- Watila, Musa M.; Balarabe, Salisu A.; Ojo, Olubamiwo; Keezer, Mark R.; Sander, Josemir W. (October 2018). "Overall and cause-specific premature mortality in epilepsy: A systematic review" (PDF). Epilepsy & Behavior. 87: 213–225. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.07.017. ISSN 1525-5050. PMID 30154056. S2CID 52114431.

- Hamilton, Kyra; Keech, Jacob J.; Peden, Amy E.; Hagger, Martin S. (3 June 2018). "Alcohol use, aquatic injury, and unintentional drowning: A systematic literature review". Drug and Alcohol Review. 37 (6): 752–773. doi:10.1111/dar.12817. ISSN 0959-5236. PMID 29862582. S2CID 44151090. Archived from the original on 14 March 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- "Drowning". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- "Drowning: Background, Etiology, Epidemiology". 21 October 2021.

- Kenny D, Martin R. Drowning and sudden cardiac death. Arch Dis Child. 2011 Jan;96(1):5-8. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.185215. Epub 2010 Jun 28. PMID 20584851.

- Gilcrest, Julia; Parker, Erin (May 2014). "Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Fatal Unintentional Drowning Among Persons Aged ≤29 Years — United States, 1999–2010". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Archived from the original on 10 November 2020. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- Campbell, Ernest (1996). "Free Diving and Shallow Water Blackout". Diving Medicine Online. scuba-doc.com. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- Lindholm, P; Lundgren, C. E. (2006). "Alveolar gas composition before and after maximal breath-holds in competitive divers". Undersea & Hyperbaric Medicine. 33 (6): 463–7. PMID 17274316. Archived from the original on 24 March 2011. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- Harle, Lindsey (August 2012). "Drowning". Forensic pathology: Types of injuries. PathologyOutlines.com. Archived from the original on 7 February 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- Gorman, Mark (2008). Jose Biller (ed.). Interface of Neurology and Internal Medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 702–706. ISBN 978-0-7817-7906-7. Archived from the original on 19 June 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- Lindholm, Peter (2006). Lindholm, P.; Pollock, N. W.; Lundgren, C. E. G. (eds.). Physiological mechanisms involved in the risk of loss of consciousness during breath-hold diving (PDF). Breath-hold diving. Proceedings of the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society/Divers Alert Network 2006 June 20–21 Workshop. Durham, NC: Divers Alert Network. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-930536-36-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 May 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- North, Robert (December 2002). "The pathophysiology of drowning" (PDF). South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society Journal. 32 (4). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- Cantwell, G Patricia (5 July 2016). "Drowning: Pathophysiology". Drugs & Diseases - Emergency Medicine. Medscape. Archived from the original on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- Hill, Erin (10 October 2020). "How Long Can the Brain Be without Oxygen before Brain Damage?". wisegeek. Archived from the original on 7 November 2020. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- Szpilman, David; Bierens, Joost J.L.M.; Handley, Anthony J.; Orlowski, James P. (4 October 2012). "Drowning". The New England Journal of Medicine. 366 (22): 2102–2110. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1013317. PMID 22646632.

- DiMaio, Dominick; DiMaio, Vincent J.M. (28 June 2001). Forensic Pathology (2nd ed.). Taylor & Francis. pp. 405–. ISBN 978-0-8493-0072-1. Archived from the original on 19 June 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- Jin, Faguang; Li, Congcong (5 April 2017). "Seawater-drowning-induced acute lung injury: From molecular mechanisms to potential treatments". Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 13 (6): 2591–2598. doi:10.3892/etm.2017.4302. ISSN 1792-0981. PMC 5450642. PMID 28587319.

- Bierens JJ, Lunetta P, Tipton M, Warner DS. Physiology Of Drowning: A Review. Physiology (Bethesda). 2016 Mar;31(2):147-66.

- Michelet, Pierre; Dusart, Marion; Boiron, Laurence; Marmin, Julien; Mokni, Tarak; Loundou, Anderson; Coulange, Mathieu; Markarian, Thibaut (3 August 2018). "Drowning in fresh or salt water". European Journal of Emergency Medicine. Publish Ahead of Print (5): 340–344. doi:10.1097/mej.0000000000000564. ISSN 0969-9546. PMID 30080702. S2CID 51929866.

- Tipton, Mike (1 December 2003). "Cold water immersion: sudden death and prolonged survival". The Lancet. 362: s12–s13. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15057-X. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 14698111. S2CID 44633363. Archived from the original on 14 March 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- "Bradycardia - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- Lundgren, Claus E. G.; Ferrigno, Massimo, eds. (1985). Physiology of Breath-hold Diving. 31st Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society Workshop. Vol. UHMS Publication Number 72(WS-BH)4-15-87. Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society. Archived from the original on 2 June 2009. Retrieved 24 April 2009.

- Mackensen, G. B.; McDonagh, D. L.; Warner, D. S. (March 2009). "Perioperative hypothermia: use and therapeutic implications". J. Neurotrauma. 26 (3): 342–58. doi:10.1089/neu.2008.0596. PMID 19231924.

- Vittone, Mario (21 October 2010). "The Truth About Cold Water". Survival. Mario Vittone. Archived from the original on 14 January 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- "Hypothermia safety". United States Power Squadrons. 23 January 2007. Archived from the original on 8 December 2008. Retrieved 19 February 2008.

- Butler, Daniel Allen (1998). Unsinkable: The Full Story of RMS Titanic. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-1814-1.

- Shattock, Michael J.; Tipton, Michael J. (14 June 2012). "'Autonomic conflict': a different way to die during cold water immersion?". The Journal of Physiology. 590 (14): 3219–3230. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2012.229864. ISSN 0022-3751. PMC 3459038. PMID 22547634.

- Tipton, M. J.; Collier, N.; Massey, H.; Corbett, J.; Harper, M. (21 September 2017). "Cold water immersion: kill or cure?". Experimental Physiology. 102 (11): 1335–1355. doi:10.1113/ep086283. ISSN 0958-0670. PMID 28833689. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- Sterba, J. A. (1990). "Field Management of Accidental Hypothermia during Diving". US Navy Experimental Diving Unit Technical Report. NEDU-1-90. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2008.

- Schmidt, AC; Sempsrott JR; Hawkins SC (2016). "Wilderness Medical Society Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Drowning". Wilderness & Environmental Medicine. 27 (2): 236–51. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2015.12.019. PMID 27061040. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- Cantwell, G Patricia (5 July 2016). "Drowning: Prognosis". Drugs & Diseases - Emergency Medicine. Medscape. Archived from the original on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- "Bathing". The Maryland Republican. Annapolis, Maryland, U.S. 1 November 1825. p. 2. Archived from the original on 14 March 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. "Water-Related Injuries". Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- "Drowning". www.who.int. Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- Pia, Frank (June 1984). "The RID factor as a cause of drowning". Parks & Recreation. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2012 – via pia-enterprises.com.

- Thompson, D. C.; Rivara, F. P. (2000). "Pool fencing for preventing drowning in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (2): CD001047. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001047. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 8407364. PMID 10796742.

- Piscines, Cheminées Villas. "Swimming Pool Laws". Angloinfo France. Angloinfo France. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- Bain, Eva (20 June 2018). "Drowning in epilepsy: A population-based case series". Epilepsy Research. 145: 123–126. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2018.06.010. PMID 29957568. S2CID 49591807. Archived from the original on 14 March 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2020 – via Science Direct.

- Näyhä, Simo (18 December 2007). "Heat mortality in Finland in the 2000s". International Journal of Circumpolar Health. 66 (5): 418–424. doi:10.3402/ijch.v66i5.18313. PMID 18274207. S2CID 6762672.

- "Ovi Magazine : Finnish midsummer consumed by alcohol by Thanos Kalamidas". www.ovimagazine.com. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- "Summer Solstice - Midsummer in Finland". www.homesofmyrtlebeach.com. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- Borius, Pierre-Yves (3 December 2009). "Cervical spine injuries resulting from diving accidents in swimming pools: outcome of 34 patients". European Spine Journal. 19 (4): 552–557. doi:10.1007/s00586-009-1230-3. PMC 2899837. PMID 19956985.

- "Water safety - RoSPA". rospa.com. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- DeNicola, L. K.; Falk, J. L.; Swanson, M. E.; Gayle, M. O.; Kissoon, N. (July 1997). "Submersion injuries in children and adults". Critical Care Clinics. 13 (3): 477–502. doi:10.1016/s0749-0704(05)70325-0. ISSN 0749-0704. PMID 9246527.

- Sanders, Mick J.; Lewis, Lawrence M.; Quick, Gary (1 August 2020). Mosby's Paramedic Textbook - Mick J. Sanders, Lawrence M. Lewis, Gary Quick - Google Books. ISBN 9780323072755. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- "Drowning Doesn't Look Like Drowning — Foster Community Online". Foster.vic.au. Archived from the original on 8 March 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- "§ 160.150-4 Construction and workmanship - (e) Weight". Guideline 160.150--Specification for Lifebuoys, SOLAS (PDF). p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 March 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- Rowan, Karen (14 August 2010). "Why do people often drown together?". Live Science. Archived from the original on 28 May 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- Franklin, Richard; Pearn, John (26 October 2010). "Drowning for love: the aquatic victim-instead-of-rescuer syndrome: drowning fatalities involving those attempting to rescue a child" (PDF). Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 47 (1–2): 44–47. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01889.x. PMID 20973865. S2CID 205470277. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 May 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- Starrenburg, Caleb (5 January 2014). "Would-be rescuers losing their lives". Stuff.co.nz. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- "2005 ILCOR resuscitation guidelines" (PDF). Circulation. 112 (22 supplement). 29 November 2005. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.166480. S2CID 247579422. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 February 2008. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

There is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against the use of oxygen by the first aid provider.

- Hazinski, Mary Fran, ed. (2010). Guidelines for CPR and ECC (PDF). Highlights of the 2010 American Heart Association (Report). American Heart Association. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Near drowning

- Wall, Ron (2017). Rosen's Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice (9 ed.). Elsevier. p. 1802. ISBN 978-0323354790.

- McKenna, Kim D. (2011). Mosby's paramedic textbook. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 1262–1266. ISBN 978-0-323-07275-5. Archived from the original on 19 June 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- "Drowning - Symptoms, diagnosis and treatment". BMJ Best Practice. Archived from the original on 3 December 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- Hughes, S. K.; Nilsson, D. E.; Boyer, R. S.; Bolte, R. G.; Hoffman, R. O.; Lewine, J. D.; Bigler, E. D. (2002). "Neurodevelopmental outcome for extended cold water drowning: A longitudinal case study". Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 8 (4): 588–596. doi:10.1017/s1355617702814370. PMID 12030312. S2CID 23780668.

- Gonzalez-Rothi RJ. Near drowning: consensus and controversies in pulmonary and cerebral resuscitation. Heart Lung. 1987 Sep;16(5):474-82. PMID 3308778.

- Rivers JF, Orr G, Lee HA. Drowning. Its clinical sequelae and management. Br Med J. 1970 Apr 18;2(5702):157-61. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5702.157. PMID 4909451; PMCID: PMC1699975.

- Suominen, Pertti K.; Vähätalo, Raisa (15 August 2012). "Neurologic long term outcome after drowning in children". Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine. 20 (55): 55. doi:10.1186/1757-7241-20-55. ISSN 1757-7241. PMC 3493332. PMID 22894549.

- Quan, Linda; Wentz, Kim R.; Gore, Edmond J.; Copass, Michael K. (1 October 1990). "Outcome and Predictors of Outcome in Pediatric Submersion Victims Receiving Prehospital Care in King County, Washington". Pediatrics. 86 (4): 586–593. doi:10.1542/peds.86.4.586. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 2216625. S2CID 7375830.

- Ibsen, Laura M.; Koch, Thomas (November 2002). "Submersion and asphyxial injury". Critical Care Medicine. 30 (Supplement): S402–S408. doi:10.1097/00003246-200211001-00004. ISSN 0090-3493. PMID 12528781.

- "Cerebral Cortex: What It Is, Function & Location". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- Bierens, Joost J. L.M.; Knape, Johannes T.A.; Gelissen, Harry P. M.M. (December 2002). "Drowning". Current Opinion in Critical Care. 8 (6): 578–586. doi:10.1097/00075198-200212000-00016. ISSN 1070-5295. PMID 12454545.

- Zeraati, Abbas Ali; Amini, Shahram; Mortazi, Hasan; Zeraati, Tina; Zeraati, Dorsa (1 May 2018). "Sp238The Effect of Selenium on Prevention of Acute Kidney Injury After On-Pump Cardiac Surgery". Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 33 (suppl_1): i423–i424. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfy104.sp238. ISSN 0931-0509.

- Burnay, Carolina; Anderson, David I.; Button, Chris; Cordovil, Rita; Peden, Amy E. (11 April 2022). "Infant Drowning Prevention: Insights from a New Ecological Psychology Approach". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 19 (8): 4567. doi:10.3390/ijerph19084567. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 9029552. PMID 35457435.

- "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Archived from the original on 11 November 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- Lozano, R; Naghavi, M.; Foreman, K.; Lim, S.; Shibuya, K.; Aboyans, V.; Abraham, J.; Adair, T.; Aggarwal, R.; Ahn, S. Y.; Alvarado, M.; Anderson, H. R.; Anderson, L. M.; Andrews, K. G.; Atkinson, C.; Baddour, L. M.; Barker-Collo, S.; Bartels, D. H.; Bell, M. L.; Benjamin, E. J.; Bennett, D.; Bhalla, K.; Bikbov, B.; Bin Abdulhak, A.; Birbeck, G.; Blyth, F.; Bolliger, I.; Boufous, S.; Bucello, C.; et al. (15 December 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30050819. PMID 23245604. S2CID 1541253. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- "Drowning". www.who.int. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- Committee on injury, violence, and poison prevention (2010). "Policy Statement—Prevention of Drowning". Pediatrics. 126 (1): 178–185. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1264. PMID 20498166. Archived from the original on 9 June 2010.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Drowning, Homicide and Suicide Leading Killers for Children in Asia". The Salem News. 11 March 2008. Archived from the original on 11 September 2011. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- "UNICEF Says Injuries A Fatal Problem For Asian Children". All Headline News. 13 March 2008. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- "Children Drowning, Drowning Children" (PDF). The Alliance for Safe Children. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 August 2011. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- Cantwell, G Patricia (5 July 2016). "Drowning: Epidemiology". Drugs & Diseases - Emergency Medicine. Medscape. Archived from the original on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- Franklin, Richard Charles; Peden, Amy E.; Hamilton, Erin B.; Bisignano, Catherine; Castle, Chris D.; Dingels, Zachary V.; Hay, Simon I.; Liu, Zichen; Mokdad, Ali H.; Roberts, Nicholas L. S.; Sylte, Dillon O. (October 2020). "The burden of unintentional drowning: global, regional and national estimates of mortality from the Global Burden of Disease 2017 Study". Injury Prevention. 26 (Supp 1): i83–i95. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2019-043484. ISSN 1475-5785. PMC 7571364. PMID 32079663.

- Gupta, Medhavi; Bhaumik, Soumyadeep; Roy, Sujoy; Panda, Ranjan Kanti; Peden, Margaret; Jagnoor, Jagnoor (October 2021). "Determining child drowning mortality in the Sundarbans, India: applying the community knowledge approach". Injury Prevention. 27 (5): 413–418. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2020-043911. hdl:10044/1/98550. ISSN 1475-5785. PMID 32943493. S2CID 221787099.

- Dandona, Rakhi; Kumar, G. Anil; George, Sibin; Kumar, Amit; Dandona, Lalit (October 2019). "Risk profile for drowning deaths in children in the Indian state of Bihar: results from a population-based study". Injury Prevention. 25 (5): 364–371. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2018-042743. ISSN 1475-5785. PMC 6839727. PMID 29778993.

- "19 women killed as wedding boat capsizes in Sadiqabad". Daily Times. 19 July 2022. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- "Global Drowning Research & Prevention | Drowning Prevention | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 17 June 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- Miller, Lauren; Alele, Faith; Emeto, Theophilus; Franklin, Richard (25 September 2019). "Epidemiology, Risk Factors and Measures for Preventing Drowning in Africa: A Systematic Review". Medicina. 55 (10): 637. doi:10.3390/medicina55100637. ISSN 1648-9144. PMC 6843779. PMID 31557943.

- "Drowning". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 23 September 2014. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- Clemens, Tessa (2021). "Persistent Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Fatal Unintentional Drowning Rates Among Persons Aged ≤29 Years — United States, 1999–2019". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 70 (24): 869–874. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7024a1. ISSN 0149-2195. PMC 8220955. PMID 34138831.

- Hazzard, Andrew (28 September 2021). "Racial Disparities Persist in Drowning Deaths". Sahan Journal. Archived from the original on 28 September 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- "Traffic Accidents Top Cause Of Fatal Child Injuries". Science. National Public Radio. 10 December 2008. Archived from the original on 12 December 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- "Drowning: It Can Happen in an Instant". US National Safety Council. 2019. Archived from the original on 14 June 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- Breining, Greg (29 May 2015). "Silent Drowning: How to Spot the Signs and Save a Life". Outdoors. Safe Bee. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- Hawkins, SC; Sempsrott, J.; Schmidt, A. (16 June 2017). "Drowning in a Sea of Misinformation: Dry Drowning and Secondary Drowning". Emergency Medicine News. Archived from the original on 7 August 2017.

- Szpilman, D; Bierens JL; Handley A; Orlowski JP (2012). "Drowning". New England Journal of Medicine. 10 (2): 2102–2110. doi:10.1056/nejmra1013317. PMID 22646632.

- van Beeck, EF (2006). "Definition of Drowning". In Handbook on Drowning: Prevention, Rescue, Treatment. Berlin: Springer.

- Van Beeck, EF; Branche, CM (2005). "A new definition of drowning: towards documentation and prevention of a global public health program". Bull World Health Organ. 83 (11): 853–856. PMC 2626470. PMID 16302042.