Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised the English monarch. Great councils were first called Parliaments during the reign of Henry III (r. 1216–1272). By this time, the king required Parliament's consent to levy taxation.

Parliament of England | |

|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) Royal coat of arms of England, 1558–1603 | |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Houses | Upper house: House of Lords (1341–1649 / 1660–1707) House of Peers (1657–1660) Lower house: House of Commons (1341–1707) |

| History | |

| Established | 15 June 1215 (Lords only) 20 January 1265 (Lords and elected Commons) |

| Disbanded | 1 May 1707 |

| Preceded by | Curia regis |

| Succeeded by | Parliament of Great Britain |

| Leadership | |

William Cowper1 since 1705 | |

Speaker of the House of Commons | John Smith1 since 1705 |

| Structure | |

| |

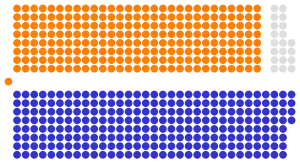

House of Commons political groups | Final composition of the English House of Commons: 513 Seats Tories: 260 seats Unclassified: 20 seats |

| Elections | |

| Ennoblement by the Sovereign or inheritance of an English peerage | |

House of Commons voting system | First past the post with limited suffrage1 |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Palace of Westminster, Westminster, London | |

| Footnotes | |

| 1Reflecting Parliament as it stood in 1707.

See also: Parliament of Scotland, Parliament of Ireland | |

Originally a unicameral body, a bicameral Parliament emerged when its membership was divided into the House of Lords and House of Commons, which included knights of the shire and burgesses. During Henry IV's time on the throne, the role of Parliament expanded beyond the determination of taxation policy to include the "redress of grievances," which essentially enabled English citizens to petition the body to address complaints in their local towns and counties. By this time, citizens were given the power to vote to elect their representatives—the burgesses—to the House of Commons.

Over the centuries, the English Parliament progressively limited the power of the English monarchy, a process that arguably culminated in the English Civil War and the High Court of Justice for the trial of Charles I.

Predecessors (pre-13th century)

Witan

The origins of Parliament can be traced to the 10th century when a unified Kingdom of England was forged from several smaller kingdoms. In Anglo-Saxon England, the king would hold deliberative assemblies of nobles and prelates called witans. These assemblies numbered anywhere from twenty-five to hundreds of participants, including bishops, abbots, ealdormen, and thegns. Witans met regularly during the three feasts of Christmas, Easter and Whitsun and at other times. In the past, kings interacted with their nobility through royal itineration, but the new kingdom's size made that impractical. Having nobles come to the king for witans was an important alternative to maintain control of the realm.[1]

Witans served several functions. They appear to have had a role in electing kings, especially in times when the succession was disputed. They were theatrical displays of kingship in that they coincided with crown-wearings. They were also forums for receiving petitions and building consensus among the magnates. Kings dispensed patronage, such as granting bookland, and these were recorded in charters witnessed and consented to by those in attendance. Appointments to offices, such as to bishoprics or ealdormanries, were also made during witans. In addition, important political decisions were made in consultation with witans, such as going to war and making treaties. Witans also helped the king to produce Anglo-Saxon law codes and acted as a court for important cases (such as those involving the king or important magnates).[2]

Magnum Concilium

After the Norman Conquest of 1066, William the Conqueror (r. 1066–1087) continued the tradition of summoning assemblies of magnates to consider national affairs, conduct state trials, and make laws; although legislation now took the form of writs rather than law codes. These assemblies were called magnum concilium (Latin for "great council").[3] While kings had access to familiar counsel, this private advice could not replace the need for consensus building, and overreliance on familiar counsel could lead to political instability. Great councils were valued because they "carried fewer political risks, allowed responsibility to be more broadly shared, and drew a larger body of prelates and magnates into the making of decisions".[4]

The council's members were the king's tenants-in-chief. The greater tenants, such as archbishops, bishops, abbots, earls, and barons were summoned by individual writ, but sometimes lesser tenants[note 1] were also summoned by sheriffs.[6] Politics in the period following the Conquest (1066–1154) was dominated by about 200 wealthy laymen, in addition to the king and leading clergy. High-ranking churchmen (such as bishops and abbots) were important magnates in their own right. According to Domesday Book, the English church owned between 25% and 33% of all land in 1066.[7]

Traditionally, the great council was not involved in levying taxes. Royal finances derived from land revenues, feudal aids and incidents, and the profits of royal justice. This changed near the end of Henry II's reign (1154–1189) due to the levying of national taxation to finance the Third Crusade, ransom Richard I, and pay for the series of Anglo-French wars fought between the Plantagenet and Capetian dynasties. In 1188, Henry II set a precedent when he applied to the great council for consent to levy the Saladin tithe.[8]

The burden imposed by national taxation and the likelihood of resistance made consent politically necessary. It was convenient for kings to present the great council of magnates as a representative body capable of consenting on behalf of all within the kingdom. Increasingly, the kingdom was described as the communitas regni (Latin for "community of the realm") and the barons as their natural representatives. But this development also created more conflict between kings and the baronage as the latter attempted to defend what they considered the rights belonging to the king's subjects.[9]

King John (r. 1199–1216) alienated the barons by his partiality in dispensing justice, heavy financial demands and abusing his right to feudal incidents, reliefs, and aids. In 1215, the barons forced John to abide by a charter of liberties similar to charters issued by earlier kings (see Charter of Liberties).[10] Known as Magna Carta (Latin for "Great Charter"), the charter was based on three assumptions important to the later development of Parliament:[11]

- the king was subject to the law

- the king could only make law and raise taxation (except customary feudal dues) with the consent of the community of the realm

- that the obedience owed by subjects to the king was conditional and not absolute

While the clause stipulating no taxation "without the common counsel" was deleted from later reissues, it was nevertheless adhered to by later kings. Magna Carta transformed the feudal obligation to advise the king into a right to consent. While it was the barons who made the charter, the liberties guaranteed within it were granted to "all the free men of our realm".[12] The charter was promptly repudiated by the king, which led to the First Barons' War,[13] but Magna Carta would gain the status of fundamental law during the reign of John's successor.[14]

Early development (1216–1307)

Henry III and the first parliaments

Henry III (r. 1216–1272) became king at nine years old after his father, King John, died during the First Barons' War. During the king's minority, England was ruled by a regency government that relied heavily on great councils to legitimise its actions. Great councils even consented to the appointment of royal ministers, an action that normally was considered a royal prerogative. Historian John Maddicott writes that the "effect of the minority was thus to make the great council an indispensable part of the country's government [and] to give it a degree of independent initiative and authority which central assemblies had never previously possessed".[15]

The regency government officially ended when Henry turned sixteen in 1223, and the magnates demanded the adult king confirm previous grants of Magna Carta made in 1216 and 1217 to ensure their legality. At the same time, the king needed money to defend his possessions in Poitou and Gascony from a French invasion. At a great council in 1225, a deal was reached that saw Magna Carta and the Charter of the Forest reissued in return for a fifteenth tax on "movables" (personal property and rents). This set a precedent that taxation was granted in return for the redress of grievances.[16]

In the mid-1230s, the word parliament came into common use for meetings of the great council.[17] The word parliament comes from the French parlement first used in the late 11th century with the meaning of parley or conversation (compare to the parlements of Ancien Régime France).[18] It was in Parliament, and with its assent, that the king declared law and where national affairs were deliberated. It granted or refused the king's request for extraordinary taxation (as opposed to ordinary feudal or customary taxes), and it served as England's highest court of justice.[19]

After the 1230s, the normal meeting place for Parliament was fixed at Westminster. Parliament tended to meet according to the legal year so that the courts were also in session. It often met in January or February for the Hilary term, in April or May for the Easter term, in July, and in October for the Michaelmas term.[20] In the 13th century, most parliaments had between forty to eighty attendees.[21] Meetings of Parliament always included:[22][23]

- the king

- chief ministers and other ministers (great officers of state, justices of the King's Bench and Common Bench, and barons of the exchequer)

- members of the king's council

- ecclesiastical magnates (archbishops, bishops, abbots, priors)

- lay magnates (earls and barons)

Other groups were occasionally summoned. The lesser tenants-in-chief (or knights) were regularly summoned to consent to taxation; though, they were summoned on the basis of their status as tenants of the Crown rather than as representatives of a wider class. The lower clergy (deans, cathedral priors, archdeacons, parish priests) were occasionally summoned when papal taxation was on the agenda. Beginning around the 1220s, the concept of representation, summarised in the Roman law maxim quod omnes tangit ab omnibus approbetur (Latin for "what touches all should be approved by all"), gained new importance among the clergy, and they began choosing proctors to represent them at church assemblies and, when summoned, at Parliament.[24]

Emergence of parliamentary politics

In 1232, Peter des Roches became the king's chief minister. His nephew, Peter de Rivaux, accumulated a large number of offices, including keeper of the privy seal and keeper of the wardrobe; yet, these appointments were not approved by the magnates as had become customary during the regency government. Under Roches, the government revived practices used during King John's reign and that had been condemned in Magna Carta, such as arbitrary disseisins, revoking perpetual rights granted in royal charters, depriving heirs of their inheritances, and marrying heiresses to foreigners.[25]

To make matters worse, both Roches and Rivaux were foreigners from Poitou. The rise of a royal administration controlled by foreigners and dependent solely on the king stirred resentment among the magnates, who felt excluded from power. Several barons rose in rebellion, and the bishops intervened to persuade the king to change ministers. At a great council in April 1234, the king agreed to remove Rivaux and other ministers. This was the first occasion in which a king was forced to change his ministers by a great council or parliament. The struggle between king and Parliament over ministers became a permanent feature of English politics.[26]

Thereafter, the king ruled in concert with an active Parliament, which considered matters related to foreign policy, taxation, justice, administration, and legislation. January 1236 saw the passage of the Statute of Merton, the first English statute. Among other things, the law continued barring bastards from inheritance. Significantly, the language of the preamble describes the legislation as "provided" by the magnates and "conceded" by the king, which implies that this was not simply a royal measure consented to by the barons.[27][28] In 1237, Henry asked Parliament for a tax to fund his sister Isabella's dowry. The barons were unenthusiastic, but they granted the funds in return for the king's promise to reconfirm Magna Carta, add three magnates to his personal council, limit the royal prerogative of purveyance, and protect land tenure rights.[29]

But Henry was adamant that three concerns were exclusively within his royal prerogative: family and inheritance matters, patronage, and appointments. Important decisions were made without consulting Parliament, such as in 1254 when the king accepted the throne of the Kingdom of Sicily for his younger son, Edmund Crouchback.[30] He also clashed with Parliament over appointments to the three great offices of chancellor, justiciar, and treasurer. The barons believed these three offices should be restraints on royal misgovernment, but the king promoted minor officials within the royal household who owed their loyalty exclusively to him.[31]

Parliament's main tool against the king was to deny consent to national taxation, which they consistently withheld after 1237. Nevertheless, this proved ineffective at restraining the king as he was still able to raise lesser amounts of revenue from sources that did not require parliamentary consent:[32][33]

- county farms (the fixed sum paid annually by sheriffs for the privilege of administering and profiting from royal lands in their counties)

- profits from the eyre

- tallage on the royal demesne, the towns, foreign merchants, and most importantly English Jews

- scutage

- feudal dues and fines

- profits from wardship, escheat, and vacant episcopal sees

In 1253, while fighting in Gascony, Henry requested men and money to resist an anticipated attack from the King of Castile. In a January 1254 Parliament, the bishops themselves promised an aid but would not commit the rest of the clergy. Likewise, the barons promised to assist the king if he was attacked but would not commit the rest of the laity to pay money.[34] For this reason, delegates from the lower clergy from each diocese and two knights of the shire from every county were summoned to Parliament in April 1254.[35] This was the first time that representatives of the Commons or communities of the realm were summoned to Parliament. The knights were elected by the barons, other knights, and probably freeholders of sufficient standing. Such a development illustrated the increasing importance of the gentry as a class. As representatives of their counties, the knights' decisions would be binding on all taxpayers in the shires. No taxation was granted, however, as the attack from Castile never materialised.[36]

Reform movement and civil war

By 1258, the relationship between the king and the baronage had reached a breaking point over the "Sicilian Business", in which Henry had promised to pay papal debts in return for the pope's help securing the Sicilian crown for his son, Edmund. At the Oxford Parliament of 1258, reform-minded barons forced a reluctant king to accept a constitutional framework known as the Provisions of Oxford. The king was now required to govern according to the advice of a council of fifteen magnates. Royal ministers—such as the justiciar, treasurer, and chancellor—would serve for one-year terms, after which they would be accountable to the king and the Fifteen for their conduct in office.[37] Parliament was to meet three times a year at Michaelmas (October 6), Candlemas (February 3), and on June 1. The barons were to elect twelve representatives who together with the Fifteen could act on legislation and other matters even when Parliament was not in session. Historian Ronald Butt describes this as "a kind of standing parliamentary committee".[38] The October Parliament of 1259 enacted the Provisions of Westminster, a set of legal and administrative reforms designed to correct the grievances of the barons and lesser landowners.[39]

While Henry was in France making peace with Louis IX, a dispute arose whether Parliament could meet without the king's consent. Henry ordered Hugh Bigod, the justiciar, to postpone the upcoming Parliament scheduled for Candlemas 1260 until the king returned to England. Simon de Montfort, a leader of the baronial reformers, ignored these orders and continued with plans to hold a Parliament. When the king arrived back in England he summoned a Parliament which met in July, where Montfort was brought to trial though ultimately cleared of wrongdoing.[40]

In April 1261, the pope released the king from his oath to adhere to the Provisions of Oxford, and Henry publicly renounced the Provisions in May. Most of the barons were willing to let the king reassume power provided he ruled well. By 1262, Henry had regained all of his authority, and Montfort left England. The barons were now divided mainly by age. The elder barons remained loyal to the king, but younger barons coalesced around Montfort, who returned to England in the spring of 1263.[41]

The royalist barons and rebel barons fought each other in the Second Barons' War. The king was defeated at the Battle of Lewes in 1264, and Montfort became the real ruler of England for the next twelve months. However, Henry was still king, and the rebels never considered removing him. Instead, Montfort called a Parliament to sanction a new form of government to control the king. The Parliament held in June 1264 was notable for including knights of the shire who were expected to deliberate fully on political matters, not just assent to taxation. This Parliament approved the appointment of three electors (Montfort, Stephen Bersted, Bishop of Chichester, and Gilbert de Clare, 7th Earl of Gloucester). These men were to choose a council of nine, by whose advice the king was to rule. The electors could replace any of the nine as they saw fit, but the electors themselves could only be removed by Parliament.[42]

Montfort held to other Parliaments during his time in power. The most famous—Simon de Montfort's Parliament—was held in January 1265 amidst threat of a French invasion and unrest throughout the realm. For the first time, burgesses (elected by those residents of boroughs or towns who held burgage tenure, such as wealthy merchants or craftsmen)[43] were summoned along with knights of the shire.[44] Montfort was killed at the Battle of Evesham in 1265, and Henry was restored to power. In August 1266, Parliament authorised the Dictum of Kenilworth, which nullified everything Montfort had done and removed all restraints on the king.[45] In 1267, some of the reforms contained in the 1259 Provisions of Westminster were revised in the form of the Statute of Marlborough passed in 1267. This was the start of a process of statutory reform that continued into the reign of Henry's successor.[46]

Edward I

Montfort's scheme was later formally adopted by Edward I in the so-called "Model Parliament" of 1295. The attendance at parliament of knights and burgesses historically became known as the summoning of "the Commons", a term derived from the Norman French word "commune", literally translated as the "community of the realm".

The role of Parliament in the government of the English kingdom increased due to Edward's determination to unite England, Wales and Scotland under his rule by force. He was also keen to unite his subjects in order to restore his authority and not face rebellion as was his father's fate. Edward therefore encouraged all sectors of society to submit petitions to parliament detailing their grievances in order for them to be resolved. This seemingly gave all of Edward's subjects a potential role in government and this helped Edward assert his authority. Both the Statute of Westminster 1275 and Statute of Westminster 1285, with the assistance of Robert Burnell, codified the existing law in England.

As the number of petitions being submitted to parliament increased, they came to be dealt with, and often ignored, more and more by ministers of the Crown so as not to block the passage of government business through parliament. However, the emergence of petitioning is significant because it is some of the earliest evidence of parliament being used as a forum to address the general grievances of ordinary people. Submitting a petition to parliament is a tradition that continues to this day in the Parliament of the United Kingdom and in most Commonwealth realms.

These developments symbolise the fact that parliament and government were by no means the same thing by this point. If monarchs were going to impose their will on their kingdom, they would have to control parliament rather than be subservient to it.

From Edward's reign onwards, the authority of the English Parliament would depend on the strength or weakness of the incumbent monarch. A strong the king or queen would wield enough influence to pass their legislation through parliament without much trouble. Some strong monarchs even bypassed it completely, although this was not often possible in the case of financial legislation due to the post-Magna Carta convention of parliament granting taxes. When weak monarchs governed, parliament often became the centre of opposition against them.

The composition of parliaments in this period varied depending on the decisions that needed to be taken in them. The nobility and senior clergy were always summoned. From 1265 onwards, when the monarch needed to raise money through taxes, it was usual for knights and burgesses to be summoned too. However, when the king was merely seeking advice, he often only summoned the nobility and the clergy, sometimes with and sometimes without the knights of the shires. On some occasions the Commons were summoned and sent home again once the monarch was finished with them, allowing parliament to continue without them. It was not until the mid-14th century that summoning representatives of the shires and the boroughs became the norm for all parliaments.

Formal separation of Lords and Commons

One of the moments that marked the emergence of parliament as a true institution in England was the deposition of Edward II in January 1327. Even though it is debatable whether Edward II was deposed in parliament or by parliament, this remarkable sequence of events consolidated the importance of parliament in the English unwritten constitution. Parliament was also crucial in establishing the legitimacy of the king who replaced Edward II: his son Edward III.

In 1341 the Commons met separately from the nobility and clergy for the first time, creating what was effectively an Upper Chamber and a Lower Chamber, with the knights and burgesses sitting in the latter. This Upper Chamber became known as the House of Lords from 1544 onward, and the Lower Chamber became known as the House of Commons, collectively known as the Houses of Parliament.

The authority of parliament grew under Edward III; it was established that no law could be made, nor any tax levied, without the consent of both Houses and the Sovereign. This development occurred during the reign of Edward III because he was involved in the Hundred Years' War and needed finances. During his conduct of the war, Edward tried to circumvent parliament as much as possible, which caused this edict to be passed.

The Commons came to act with increasing boldness during this period. During the Good Parliament (1376), the Presiding Officer of the lower chamber, Peter de la Mare, complained of heavy taxes, demanded an accounting of the royal expenditures, and criticised the king's management of the military. The Commons even proceeded to impeach some of the king's ministers. The bold Speaker was imprisoned, but was soon released after the death of Edward III.

During the reign of the next monarch, Richard II, the Commons once again began to impeach errant ministers of the Crown. They insisted that they could not only control taxation, but also public expenditure. Despite such gains in authority, however, the Commons still remained much less powerful than the House of Lords and the Crown.

This period also saw the introduction of a franchise which limited the number of people who could vote in elections for the House of Commons. From 1430 onwards, the franchise was limited to Forty Shilling Freeholders, that is men who owned freehold property worth forty shillings or more. The Parliament of England legislated the new uniform county franchise, in the statute 8 Hen. 6, c. 7. The Chronological Table of the Statutes does not mention such a 1430 law, as it was included in the Consolidated Statutes as a recital in the Electors of Knights of the Shire Act 1432 (10 Hen. 6, c. 2), which amended and re-enacted the 1430 law to make clear that the resident of a county had to have a forty shilling freehold in that county to be a voter there.

King, Lords and Commons

During the reign of the Tudor monarchs, it is often argued that the modern structure of the English Parliament began to be created. The Tudor monarchy, according to historian J. E. Neale, was powerful, and there were often periods of several years when parliament did not sit at all. However, the Tudor monarchs realised that they needed parliament to legitimise many of their decisions, mostly out of a need to raise money through taxation legitimately without causing discontent. Thus they consolidated the state of affairs whereby monarchs would call and close parliament as and when they needed it. However, if monarchs did not call Parliament for several years, it is clear the Monarch did not require Parliament except to perhaps strengthen and provide a mandate for their reforms to Religion which had always been a matter within the Crown's prerogative but would require the consent of the Bishopric and Commons.

By the time of the Tudor monarch Henry VII's 1485 coronation, the monarch was not a member of either the Upper Chamber or the Lower Chamber. Consequently, the monarch would have to make his or her feelings known to Parliament through his or her supporters in both houses. Proceedings were regulated by the presiding officer in either chamber.

From the 1540s the presiding officer in the House of Commons became formally known as the "Speaker", having previously been referred to as the "prolocutor" or "parlour" (a semi-official position, often nominated by the monarch, that had existed ever since Peter de Montfort had acted as the presiding officer of the Oxford Parliament of 1258). This was not an enviable job. When the House of Commons was unhappy it was the Speaker who had to deliver this news to the monarch. This began the tradition whereby the Speaker of the House of Commons is dragged to the Speaker's Chair by other members once elected.

A member of either chamber could present a "bill" to parliament. Bills supported by the monarch were often proposed by members of the Privy Council who sat in parliament. For a bill to become law it would have to be approved by a majority of both Houses of Parliament before it passed to the monarch for royal assent or veto. The royal veto was applied several times during the 16th and 17th centuries and it is still the right of the monarch of the United Kingdom and Commonwealth realms to veto legislation today, although it has not been exercised since 1707 (today such an exercise might precipitate some form of constitutional crisis).

When a bill was enacted into law, this process gave it the approval of each estate of the realm: the King, Lords and Commons. The Parliament of England was far from being a democratically representative institution in this period. It was possible to assemble the entire peerage and senior clergy of the realm in one place to form the estate of the Upper Chamber.

The voting franchise for the House of Commons was small; some historians estimate that it was as little as three per cent of the adult male population; and there was no secret ballot. Elections could therefore be controlled by local grandees, because in many boroughs a majority of voters were in some way dependent on a powerful individual, or else could be bought by money or concessions. If these grandees were supporters of the incumbent monarch, this gave the Crown and its ministers considerable influence over the business of parliament.

Many of the men elected to parliament did not relish the prospect of having to act in the interests of others. So a law was enacted, still on the statute book today, whereby it became unlawful for members of the House of Commons to resign their seat unless they were granted a position directly within the patronage of the monarchy (today this latter restriction leads to a legal fiction allowing de facto resignation despite the prohibition, but nevertheless it is a resignation which needs the permission of the Crown). However, while several elections to parliament in this period would be considered corrupt by modern standards, many elections involved genuine contests between rival candidates, even though the ballot was not secret.

Establishment of permanent seat

It was in this period that the Palace of Westminster was established as the seat of the English Parliament. In 1548, the House of Commons was granted a regular meeting place by the Crown, St Stephen's Chapel. This had been a royal chapel. It was made into a debating chamber after Henry VIII became the last monarch to use the Palace of Westminster as a place of residence and after the suppression of the college there.

This room was the home of the House of Commons until it was destroyed by fire in 1834, although the interior was altered several times up until then. The structure of this room was pivotal in the development of the Parliament of England. While most modern legislatures sit in a circular chamber, the benches of the British Houses of Parliament are laid out in the form of choir stalls in a chapel, simply because this is the part of the original room that the members of the House of Commons used when they were granted use of St Stephen's Chapel.

This structure took on a new significance with the emergence of political parties in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, as the tradition began whereby the members of the governing party would sit on the benches to the right of the Speaker and the opposition members on the benches to the left. It is said that the Speaker's chair was placed in front of the chapel's altar. As Members came and went they observed the custom of bowing to the altar and continued to do so, even when it had been taken away, thus then bowing to the Chair, as is still the custom today.

The numbers of the Lords Spiritual diminished under Henry VIII, who commanded the Dissolution of the Monasteries, thereby depriving the abbots and priors of their seats in the Upper House. For the first time, the Lords Temporal were more numerous than the Lords Spiritual. Currently, the Lords Spiritual consist of the Archbishops of Canterbury and York, the Bishops of London, Durham and Winchester, and twenty-one other English diocesan bishops in seniority of appointment to a diocese.

The Laws in Wales Acts of 1535–42 annexed Wales as part of England and this brought Welsh representatives into the Parliament of England, first elected in 1542.

Rebellion and revolution

| Parliaments of England 1604–1705 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| List of parliaments of England | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Parliament had not always submitted to the wishes of the Tudor monarchs. But parliamentary criticism of the monarchy reached new levels in the 17th century. When the last Tudor monarch, Elizabeth I, died in 1603, King James VI of Scotland came to power as King James I, founding the Stuart monarchy.

In 1628, alarmed by the arbitrary exercise of royal power, the House of Commons submitted to Charles I the Petition of Right, demanding the restoration of their liberties. Though he accepted the petition, Charles later dissolved parliament and ruled without them for eleven years. It was only after the financial disaster of the Scottish Bishops' Wars (1639–1640) that he was forced to recall Parliament so that they could authorise new taxes. This resulted in the calling of the assemblies known historically as the Short Parliament of 1640 and the Long Parliament, which sat with several breaks and in various forms between 1640 and 1660.

The Long Parliament was characterised by the growing number of critics of the king who sat in it. The most prominent of these critics in the House of Commons was John Pym. Tensions between the king and his parliament reached a boiling point in January 1642 when Charles entered the House of Commons and tried, unsuccessfully, to arrest Pym and four other members for their alleged treason. The Five Members had been tipped off about this, and by the time Charles came into the chamber with a group of soldiers they had disappeared. Charles was further humiliated when he asked the Speaker, William Lenthall, to give their whereabouts, which Lenthall famously refused to do.

From then on relations between the king and his parliament deteriorated further. When trouble started to brew in Ireland, both Charles and his parliament raised armies to quell the uprisings by native Catholics there. It was not long before it was clear that these forces would end up fighting each other, leading to the English Civil War which began with the Battle of Edgehill in October 1642: those supporting the cause of parliament were called Parliamentarians (or Roundheads), and those in support of the Crown were called Royalists (or Cavaliers).

Battles between Crown and Parliament continued throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, but parliament was no longer subservient to the English monarchy. This change was symbolised in the execution of Charles I in January 1649.

In Pride's Purge of December 1648, the New Model Army (which by then had emerged as the leading force in the parliamentary alliance) purged Parliament of members that did not support them. The remaining "Rump Parliament", as it was later referred to by critics, enacted legislation to put the king on trial for treason. This trial, the outcome of which was a foregone conclusion, led to the execution of the king and the start of an 11-year republic.

The House of Lords was abolished and the purged House of Commons governed England until April 1653, when army chief Oliver Cromwell dissolved it after disagreements over religious policy and how to carry out elections to parliament. Cromwell later convened a parliament of religious radicals in 1653, commonly known as Barebone's Parliament, followed by the unicameral First Protectorate Parliament that sat from September 1654 to January 1655 and the Second Protectorate Parliament that sat in two sessions between 1656 and 1658, the first session was unicameral and the second session was bicameral.

Although it is easy to dismiss the English Republic of 1649–60 as nothing more than a Cromwellian military dictatorship, the events that took place in this decade were hugely important in determining the future of parliament. First, it was during the sitting of the first Rump Parliament that members of the House of Commons became known as "MPs" (Members of Parliament). Second, Cromwell gave a huge degree of freedom to his parliaments, although royalists were barred from sitting in all but a handful of cases.

Cromwell's vision of parliament appears to have been largely based on the example of the Elizabethan parliaments. However, he underestimated the extent to which Elizabeth I and her ministers had directly and indirectly influenced the decision-making process of her parliaments. He was thus always surprised when they became troublesome. He ended up dissolving each parliament that he convened. Yet it is worth noting that the structure of the second session of the Second Protectorate Parliament of 1658 was almost identical to the parliamentary structure consolidated in the Glorious Revolution Settlement of 1689.

In 1653 Cromwell had been made head of state with the title Lord Protector of the Realm. The Second Protectorate Parliament offered him the crown. Cromwell rejected this offer, but the governmental structure embodied in the final version of the Humble Petition and Advice was a basis for all future parliaments. It proposed an elected House of Commons as the Lower Chamber, a House of Lords containing peers of the realm as the Upper Chamber. A constitutional monarchy, subservient to parliament and the laws of the nation, would act as the executive arm of the state at the top of the tree, assisted in carrying out their duties by a Privy Council. Oliver Cromwell had thus inadvertently presided over the creation of a basis for the future parliamentary government of England. In 1657 he had the Parliament of Scotland (temporarily) unified with the English Parliament.

In terms of the evolution of parliament as an institution, by far the most important development during the republic was the sitting of the Rump Parliament between 1649 and 1653. This proved that parliament could survive without a monarchy and a House of Lords if it wanted to. Future English monarchs would never forget this. Charles I was the last English monarch ever to enter the House of Commons.

Even to this day, a Member of the Parliament of the United Kingdom is sent to Buckingham Palace as a ceremonial hostage during the State Opening of Parliament, in order to ensure the safe return of the sovereign from a potentially hostile parliament. During the ceremony the monarch sits on the throne in the House of Lords and signals for the Lord Great Chamberlain to summon the House of Commons to the Lords Chamber. The Lord Great Chamberlain then raises his wand of office to signal to the Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod, who has been waiting in the central lobby. Black Rod turns and, escorted by the doorkeeper of the House of Lords and an inspector of police, approaches the doors to the chamber of the Commons. The doors are slammed in his face—symbolising the right of the Commons to debate without the presence of the Queen's representative. He then strikes three times with his staff (the Black Rod), and he is admitted.

Parliament from the Restoration to the Act of Settlement

The revolutionary events that occurred between 1620 and 1689 all took place in the name of parliament. The new status of parliament as the central governmental organ of the English state was consolidated during the events surrounding the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660.

After the death of Oliver Cromwell in September 1658, his son Richard Cromwell succeeded him as Lord Protector, summoning the Third Protectorate Parliament in the process. When this parliament was dissolved under pressure from the army in April 1659, the Rump Parliament was recalled at the insistence of the surviving army grandees. This in turn was dissolved in a coup led by army general John Lambert, leading to the formation of the Committee of Safety, dominated by Lambert and his supporters.

When the breakaway forces of George Monck invaded England from Scotland, where they had been stationed without Lambert's supporters putting up a fight, Monck temporarily recalled the Rump Parliament and reversed Pride's Purge by recalling the entirety of the Long Parliament. They then voted to dissolve themselves and call new elections, which were arguably the most democratic for 20 years although the franchise was still very small. This led to the calling of the Convention Parliament which was dominated by royalists. This parliament voted to reinstate the monarchy and the House of Lords. Charles II returned to England as king in May 1660. The Anglo-Scottish parliamentary union that Cromwell had established was dissolved in 1661 when the Scottish Parliament resumed its separate meeting place in Edinburgh.

The Restoration began the tradition whereby all governments looked to parliament for legitimacy. In 1681 Charles II dissolved parliament and ruled without them for the last four years of his reign. This followed bitter disagreements between the king and parliament that had occurred between 1679 and 1681. Charles took a big gamble by doing this. He risked the possibility of a military showdown akin to that of 1642. However, he rightly predicted that the nation did not want another civil war. Parliament disbanded without a fight. Events that followed ensured that this would be nothing but a temporary blip.

Charles II died in 1685 and he was succeeded by his brother James II. During his lifetime Charles had always pledged loyalty to the Protestant Church of England, despite his private Catholic sympathies. James was openly Catholic. He attempted to lift restrictions on Catholics taking up public offices. This was bitterly opposed by Protestants in his kingdom. They invited William of Orange,[48] a Protestant who had married Mary, daughter of James II and Anne Hyde to invade England and claim the throne.

William assembled an army estimated at 15,000 soldiers (11,000 foot and 4000 horse)[49] and landed at Brixham in southwest England in November, 1688. When many Protestant officers, including James's close adviser, John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, defected from the English army to William's invasion force, James fled the country. Parliament then offered the Crown to his Protestant daughter Mary, instead of his infant son (James Francis Edward Stuart), who was baptised Catholic. Mary refused the offer, and instead William and Mary ruled jointly, with both having the right to rule alone on the other's death.

As part of the compromise in allowing William to be King—called the Glorious Revolution—Parliament was able to have the 1689 Bill of Rights enacted. Later the 1701 Act of Settlement was approved. These were statutes that lawfully upheld the prominence of parliament for the first time in English history. These events marked the beginning of the English constitutional monarchy and its role as one of the three elements of parliament.

Union: the Parliament of Great Britain

After the Treaty of Union in 1707, Acts of Parliament passed in the Parliament of England and the Parliament of Scotland created a new Kingdom of Great Britain and dissolved both parliaments, replacing them with a new Parliament of Great Britain based in the former home of the English parliament. The Parliament of Great Britain later became the Parliament of the United Kingdom in 1801 when the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was formed through the Acts of Union 1800.

Acts of Parliament

Specific Acts of Parliament can be found at the following articles:

- List of Acts of the Parliament of England to 1483

- List of Acts of the Parliament of England, 1485–1601

- List of Acts of the Parliament of England, 1603–1641

- List of Acts of the Parliament of England, 1642–1660

- List of Acts of the Parliament of England, 1660–1699

- List of Acts of the Parliament of England, 1700–1706

Locations

Other than London, Parliament was also held in the following cities:

- York, various

- Lincoln, various

- Oxford, 1258 (Mad Parliament), 1681

- Kenilworth, 1266

- Acton Burnell Castle, 1283[50]

- Shrewsbury, 1283 (trial of Dafydd ap Gruffydd), 1397 ('Great' Parliament)

- Carlisle, 1307

- Oswestry Castle, 1398

- Northampton 1328

- New Sarum (Salisbury), 1330

- Winchester, 1332, 1449

- Leicester, 1414 (Fire and Faggot Parliament), 1426 (Parliament of Bats)

- Reading Abbey, 1453

- Coventry, 1459 (Parliament of Devils)

See also

- Duration of English parliaments before 1660

- History of local government in England

- Lex Parliamentaria

- List of English ministries

- List of parliaments of England

- Modus Tenendi Parliamentum

Notes

References

- Maddicott 2010, pp. 2–6 & 11–12.

- Maddicott 2010, pp. 22, 25–26, 28, 30 & 33.

- Maddicott 2010, pp. 57, 61 & 75.

- Maddicott 2010, pp. 91 & 96.

- Maddicott 2010, p. 83.

- Maddicott 2010, pp. 76–80.

- Huscroft 2016, pp. 47 & 76.

- Maddicott 2009, p. 6.

- Maddicott 2010, pp. 123 & 140–143.

- Lyon 2016, pp. 58 & 62–63.

- Butt 1989, p. 60.

- Maddicott 2009, pp. 6–7.

- Lyon 2016, p. 63.

- Maddicott 2010, p. 152.

- Maddicott 2010, pp. 149–151 & 153.

- Butt 1989, p. 73.

- Maddicott 2010, p. 157.

- Richardson & Sayles 1981, p. I 146.

- Butt 1989, p. 65.

- Maddicott 2010, pp. 162 & 164.

- Maddicott 2009, p. 3.

- Brand 2009, p. 10.

- Maddicott 2010, p. 187.

- Maddicott 2010, pp. 202, 205 & 208.

- Maddicott 2010, pp. 167–168.

- Butt 1989, pp. 75–77.

- Sayles 1974, p. 40.

- Maddicott 2010, pp. 168–169.

- Maddicott 2010, p. 173.

- Maddicott 2010, p. 178.

- Butt 1989, p. 90.

- Butt 1989, p. 91.

- Maddicott 2010, pp. 174–175.

- Butt 1989, pp. 93–94.

- Sayles 1974, p. 44.

- Butt 1989, p. 95.

- Lyon 2016, pp. 67–70.

- Butt 1989, p. 100.

- Butt 1989, p. 102.

- Butt 1989, pp. 105–106.

- Butt 1989, p. 107.

- Butt 1989, pp. 108–109.

- Butt 1989, p. 123.

- Sayles 1974, pp. 60 & 63.

- Butt 1989, pp. 113–114.

- Jones 2012, p. 241.

- Butt 1989, p. xxiii.

- Troost 2005, p. 191.

- Troost 2005, pp. 204–205.

- Virtual Shropshire Archived 30 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine

Bibliography

- Brand, Paul (2009). "The Development of Parliament, 1215–1307". In Jones, Clyve (ed.). A Short History of Parliament: England, Great Britain, the United Kingdom, Ireland and Scotland. The Boydell Press. pp. 10–15. ISBN 978-1-843-83717-6.

- Butt, Ronald (1989). A History of Parliament: The Middle Ages. London: Constable. ISBN 0-0945-6220-2.

- Huscroft, Richard (2016). Ruling England, 1042–1217 (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-78655-4.

- Jones, Dan (2012). The Plantagenets: The Warrior Kings and Queens Who Made England (revised ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 978-1-101-60628-5.

- Lyon, Ann (2016). Constitutional History of the UK (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-20398-8.

- Maddicott, John (2009). "Origins and Beginnings to 1215". In Jones, Clyve (ed.). A Short History of Parliament: England, Great Britain, the United Kingdom, Ireland and Scotland. The Boydell Press. pp. 3–9. ISBN 978-1-843-83717-6.

- Maddicott, J. R. (2010). The Origins of the English Parliament, 924-1327. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-58550-2.

- Powell, J. Enoch; Wallis, Keith (1968). The House of Lords in the Middle Ages: A History of the English House of Lords to 1540. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-2977-6105-6.

- Richardson, H. G.; Sayles, G. O. (1981). The English Parliament in the Middle Ages. London: Hambledon Press. ISBN 0-9506-8821-5.

- Sayles, George O. (1974). The King's Parliament of England. Historical Controversies. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-3930-9322-0.

- Troost, Wouter (2005). William III, the Stadholder-King: A Political Biography. Translated by Grayson, J. C. Ashgate. ISBN 0-7546-5071-5.

Further reading

- Blackstone, William (1765). Commentaries on the Laws of England. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Chisholm, Hugh (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). pp. 835–849.

- Fryde, E. B.; Miller, Edward, eds. (1970). Historical Studies of the English Parliament. Vol. 1, Origins to 1399. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-09610-3.

- Fryde, E. B.; Miller, Edward, eds. (1970). Historical Studies of the English Parliament. Vol. 2, 1399 to 1603. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-09611-1.

- Spufford, Peter (1967). Origins of the English Parliament. Problems and Perspectives in History. Barnes & Noble, Inc.

- Thompson, Faith (1953). A Short History of Parliament: 1295-1642. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816664672. OCLC 646750148.

External links

- Birth of the English Parliament. UK Parliament

- Parliament and People. British Library

- Origins and growth of Parliament. National Archives