Narcissism

Narcissism is a self-centered personality style characterized as having an excessive interest in one's physical appearance or image and an excessive preoccupation with one's own needs, often at the expense of others.[1][2]

Narcissism exists on a continuum that ranges from normal to abnormal personality expression.[3] While there exists normal, healthy levels of narcissism in humans, there are also more extreme levels of narcissism, being seen particularly in people who are self-absorbed, or people who have a pathological mental illness like narcissistic personality disorder.[3][4]

It is one of the traits featured in the dark triad, along with Machiavellianism and subclinical psychopathy.[5]

History of thought

The term "narcissism" comes from the Roman poet Ovid's Metamorphoses, written in the year 8 AD. Book III of the poem tells the mythical story of a handsome young man, Narcissus, who spurns the advances of many potential lovers. When Narcissus rejects the nymph Echo, who was cursed to only echo the sounds that others made, the gods punish Narcissus by making him fall in love with his own reflection in a pool of water. When Narcissus discovers that the object of his love cannot love him back, he slowly pines away and dies.[6]

The concept of excessive selfishness has been recognized throughout history. In ancient Greece, the concept was understood as hubris.

It wasn't until the late 1800s that narcissism began to be defined in psychological terms.[7] Since that time, the term narcissism has had a significant divergence in meaning in psychology. It has been used to describe

- a sexual perversion,

- a normal [healthy] developmental stage,

- a symptom in psychosis, and

- a characteristic in several of the object relations [subtypes].[8] Paul Näcke and Havelock Ellis (1889) are the first psychiatrists, independent of each other, to use the term "narcissism" to describe a person who treats his own body in the same way in which the body of a sexual partner is ordinarily treated. Narcissism, in this context, was seen as a perversion that consumed a person's entire sexual life.[7] In 1911 Otto Rank published the first clinical paper about narcissism, linking it to vanity and self-admiration.[9][7]

Ernest Jones (1913) was the first to construe extreme narcissism, which he called the "God-complex", as a character flaw. He described people with God-complex as being aloof, self-important, overconfident, auto-erotic, inaccessible, self-admiring, and exhibitionistic, with fantasies of omnipotence and omniscience. He observed that these people had a high need for uniqueness.[10][11][12]

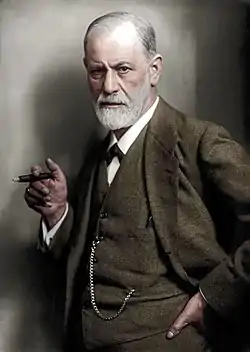

Sigmund Freud (1914) published his theory of narcissism in a lengthy essay titled "On Narcissism: An Introduction". Freud postulated that all humans have a level of narcissism from birth (primary narcissism), it is healthy, and in time, evolves outward as love for others. Freud had declared that narcissism was a necessary intermediate stage between auto-eroticism and object-love, love for others. He also theorized that narcissism becomes a neurosis (secondary narcissism) when individuals who had reached the point of projecting their affections to others, turned their affection back on themselves. In time these individuals become cut off from society and uninterested in others.[13][14][15]

Robert Waelder (1925) was the first to conceptualize narcissism as a personality trait. His definition described individuals who are condescending, feel superior to others, are preoccupied with admiration, and exhibit a lack of empathy.[16] Waelder's work and his case study have been influential in the way narcissism and the clinical disorder Narcissistic personality disorder are defined today. His patient was a successful scientist with an attitude of superiority, an obsession with fostering self-respect, and a lack of normal feelings of guilt. The patient was aloof and independent from others, had an inability to empathize with others, and was selfish sexually. Waelder's patient was also overly logical and analytical and valued abstract intellectual thought over the practical application of scientific knowledge.[17]

Karen Horney (1939) postulated that narcissism was on a spectrum that ranged from healthy self-esteem to a pathological state.[16]

The term entered the broader social consciousness following the publication of The Culture of Narcissism by Christopher Lasch in 1979.[18] Since then, social media, bloggers, and self-help authors have indiscriminately applied "narcissism" [19] as a label for the self-serving and for all domestic abusers.[20][21]

Characteristics

Narcissism is not necessarily 'good' or 'bad'; it depends on the contexts and outcomes being measured. In certain social contexts such as initiating social relationships, and with certain outcome variables, such as feeling good about oneself, healthy narcissism can be helpful. In other contexts, such as maintaining long-term relationships and with outcome variables, such as accurate self-knowledge, narcissism can be unhelpful.[22]

Four dimensions of narcissism as a personality variable have been delineated: leadership/authority, superiority/arrogance, self-absorption/self-admiration, and exploitativeness/entitlement.[23]

Normal and healthy levels of narcissism

Narcissism is an essential component of mature self-esteem and basic self-worth.[24][25][26] In essence, narcissistic behaviors are a system of intrapersonal and interpersonal strategies devoted to protecting one's self-esteem.[27]

It has been suggested that healthy narcissism is correlated with good psychological health. Self-esteem works as a mediator between narcissism and psychological health. Therefore, because of their elevated self-esteem, deriving from self-perceptions of competence and likability, high narcissists are relatively free of worry and gloom.[28]

Destructive levels of narcissism

Narcissism, in and of itself, is a normal personality trait. However, high levels of narcissistic behavior can be damaging and self-defeating.[29] Destructive narcissism is the constant exhibition of a few of the intense characteristics usually associated with pathological Narcissistic Personality Disorder such as a "pervasive pattern of grandiosity", which is characterized by feelings of entitlement and superiority, arrogant or haughty behaviors, and a generalized lack of empathy and concern for others.[2] On a spectrum, destructive narcissism is more extreme than healthy narcissism but not as extreme as the pathological condition.[30]

Pathological levels of narcissism

Extremely high levels of narcissistic behavior are considered pathological. The pathological condition of narcissism is, as Freud suggested, a magnified, extreme manifestation of healthy narcissism. Freud's idea of narcissism described a pathology that manifests itself in the inability to love others, a lack of empathy, emptiness, boredom, and an unremitting need to search for power, while making the person unavailable to others.[29] The clinical theorists Kernberg, Kohut and Theodore Millon all saw pathological narcissism as a possible outcome in response to unempathic and inconsistent early childhood interactions. They suggested that narcissists try to compensate in adult relationships.[31] German psychoanalyst Karen Horney (1885–1952) also saw the narcissistic personality as a temperament trait molded by a certain kind of early environment.

Heritability

Heritability studies using twins have shown that narcissistic traits, as measured by standardized tests, are often inherited. Narcissism was found to have a high heritability score (0.64) indicating that the concordance of this trait in the identical twins was significantly influenced by genetics as compared to an environmental causation. It has also been shown that there is a continuum or spectrum of narcissistic traits ranging from normal and a pathological personality.[32][33] Furthermore, evidence suggests that individual elements of narcissism have their own heritability score. For example, intrapersonal grandiosity has a score of 0.23, and interpersonal entitlement has a score of 0.35.[34] While the genetic impact on narcissism levels is significant, it isn't the only factor at play.

Expressions of narcissism

Sexual narcissism

Sexual narcissism has been described as an egocentric pattern of sexual behavior that involves an inflated sense of sexual ability or sexual entitlement, sometimes in the form of extramarital affairs. This can be overcompensation for low self-esteem or an inability to sustain true intimacy.[35]

While this behavioral pattern is believed to be more common in men than in women,[36][37] it occurs in both males and females who compensate for feelings of sexual inadequacy by becoming overly proud or obsessed with their masculinity or femininity.[38]

The controversial condition referred to as "sexual addiction" is believed by some experts to be sexual narcissism or sexual compulsivity, rather than an addictive behavior.[39]

Parental narcissism

Narcissistic parents often see their children as extensions of themselves, and encourage the children to act in ways that support the parents' emotional and self-esteem needs.[40] Due to their vulnerability, children may be significantly affected by this behavior.[41] To meet the parents’ needs, the child may sacrifice their own wants and feelings.[42] A child subjected to this type of parenting may struggle in adulthood with their intimate relationships.

In extreme situations, this parenting style can result in estranged relationships with the children, coupled with feelings of resentment, and in some cases, self-destructive tendencies.[40]

Workplace narcissism

- Professionals. There is a compulsion of some professionals to constantly assert their competence, even when they are wrong.[43][44] Professional narcissism can lead otherwise capable, and even exceptional, professionals to fall into narcissistic traps. "Most professionals work on cultivating a self that exudes authority, control, knowledge, competence and respectability. It's the narcissist in us all—we dread appearing stupid or incompetent."[43]

- Executives. Executives are often provided with potential narcissistic triggers:

- inanimate – status symbols like company cars, company-issued smartphone, or prestigious offices with window views; and

- animate – flattery and attention from colleagues and subordinates.[45]: 143

- Narcissism has been linked to a range of potential leadership problems ranging from poor motivational skills to risky decision making, and in extreme cases, white-collar crime.[46] High-profile corporate leaders that place an extreme emphasis on profits may yield positive short-term benefits for their organizations, but ultimately it drags down individual employees as well as entire companies.[47]

- Subordinates may find everyday offers of support swiftly turn them into enabling sources, unless they are very careful to maintain proper boundaries.[45]: 143, 181

- Studies examining the role of personality in the rise to leadership have shown that individuals who rise to leadership positions can be described as inter-personally dominant, extroverted, and socially skilled.[46] When examining the correlation of narcissism in the rise to leadership positions, narcissists who are often inter-personally dominant, extroverted, and socially skilled, were also likely to rise to leadership but were more likely to emerge as leaders in situations where they were not known, such as in outside hires (versus internal promotions). Paradoxically, narcissism can present as characteristics that facilitate an individual's rise to leadership, and ultimately lead that person to underachieve or even to fail.[46]

- General workforce. Narcissism can create problems in the general workforce. For example, individuals high in narcissism inventories are more likely to engage in counterproductive behavior that harms organizations or other people in the workplace.[48] Aggressive (and counterproductive) behaviors tend to surface when self-esteem is threatened.[49][50] Individuals high in narcissism have fragile self-esteem and are easily threatened. One study found that employees who are high in narcissism are more likely to perceive the behaviors of others in the workplace as abusive and threatening than individuals who are low in narcissism.[51]

Celebrity narcissism

Celebrity narcissism (sometimes referred to as Acquired situational narcissism) is a form of narcissism that develops in late adolescence or adulthood, brought on by wealth, fame and the other trappings of celebrity. Celebrity narcissism develops after childhood, and is triggered and supported by the celebrity-obsessed society. Fans, assistants and tabloid media all play into the idea that the person really is vastly more important than other people, triggering a narcissistic problem that might have been only a tendency, or latent, and helping it to become a full-blown personality disorder. "Robert Millman says that what happens to celebrities is that they get so used to people looking at them that they stop looking back at other people."[52] In its most extreme presentation and symptoms, it is indistinguishable from narcissistic personality disorder, differing only in its late onset and its environmental support by large numbers of fans. "The lack of social norms, controls, and of people centering them makes these people believe they're invulnerable,"[53] so that the person may suffer from unstable relationships, substance abuse or erratic behaviors.

Collective narcissism

Collective narcissism is a type of narcissism where an individual has an inflated self-love of their own group.[54] While the classic definition of narcissism focuses on the individual, collective narcissism asserts that one can have a similar excessively high opinion of a group, and that a group can function as a narcissistic entity.[54] Collective narcissism is related to ethnocentrism; however, ethnocentrism primarily focuses on self-centeredness at an ethnic or cultural level, while collective narcissism is extended to any type of ingroup beyond just cultures and ethnicities.[54][55]

Normalization of narcissistic behaviors

Some commentators contend that the American populace has become increasingly narcissistic since the end of World War II.[57][58][59][60] People compete mightily for attention. In social situations they tend to steer the conversation away from others and toward themselves. The profusion of popular literature about "listening" and "managing those who talk constantly about themselves" suggests its pervasiveness in everyday life.[61] This claim is substantiated by the growth of "reality TV" programs,[57] the growth of an online culture in which digital media, social media and the desire for fame are generating a "new era of public narcissism."[62]

Also supporting the contention that American culture has become more narcissistic is an analysis of US popular song lyrics between 1987 and 2007. This found a growth in the use of first-person singular pronouns, reflecting a greater focus on the self, and also of references to antisocial behavior; during the same period, there was a diminution of words reflecting a focus on others, positive emotions, and social interactions.[63][64] References to narcissism and self-esteem in American popular print media have experienced vast inflation since the late 1980s.[64] Between 1987 and 2007 direct mentions of self-esteem in leading US newspapers and magazines increased by 4,540 per cent while narcissism, which had been almost non-existent in the press during the 1970s, was referred to over 5,000 times between 2002 and 2007.[64]

Individualistic vs collectivist national cultures

Similar patterns of change in cultural production are observable in other Western states. For example, a linguistic analysis of the largest circulation Norwegian newspaper found that the use of self-focused and individualistic terms increased in frequency by 69 per cent between 1984 and 2005 while collectivist terms declined by 32 per cent.[65]

One study looked at differences in advertising between an individualistic culture, United States, and a collectivist culture, South Korea and found that in the US there was a greater tendency to stress the distinctiveness and uniqueness of the person; where as advertising in South Korean stressed the importance of social conformity and harmony.[65] These cultural differences were greater than the effects of individual differences within national cultures.[65]

Controversies

There has been an increased interest in narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) in the last 10 years.[66] There are areas of substantial debate that surround the subject including:

- clearly defining the difference between normal and pathological narcissism,[66]

- understanding the role of self-esteem in narcissism,[66]

- reaching a consensus on the classifications and definitions of sub-types such as "grandiose" and "vulnerable dimensions" or variants of these,[66]

- understanding what are the central versus peripheral, primary versus secondary features/characteristics of narcissism,

- determining if there is consensual description,[66]

- agreeing on the etiological factors,[66]

- deciding what field or discipline narcissism should be studied by,[66]

- agreeing on how it should be assessed and measured,[66] and

- agreeing on its representation in textbooks and classification manuals.[66]

This extent of the controversy was on public display in 2010-2013 when the committee on personality disorders for the 5th Edition (2013) of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders recommended the removal of Narcissistic Personality from the manual. A contentious three year debate unfolded in the clinical community with one of the sharpest critics being professor John Gunderson, MD, the person who led the DSM personality disorders committee for the 4th edition of the manual.[67]

See also

- Compensation

- Empathy

- Entitlement

- Grandiosity

- Self-esteem

References

- "Oxford Learner's Dictionary". oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- "APA Dictionary of Psychology". dictionary.apa.org. American Psychological Association. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- Krizan, Zlatan; Herlache, Anne (January 27, 2017). "The Narcissism Spectrum Model: A Synthetic View of Narcissistic Personality". Personality and Social Psychology Review. 22 (1): 3–31. doi:10.1177/1088868316685018. PMID 28132598. S2CID 206682971.

- Nazario, MD, Brunilda. "Narcissistic Personality Disorder". webmd.com. Web MD. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Furnham, Adrian; Richards, Steven C.; Paulhus, Delroy L. (2013). "The Dark Triad of Personality: A 10 Year Review". Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 7 (3): 199–216. doi:10.1111/spc3.12018.

- "Narcissus Greek mythology". britannica.com. Britanica. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- Millon, Theodore; Grossman, Seth; Million, Carrie; Meagher, Sarah; Ramnath, Rowena (2004). Personality Disorders in Modern Life (PDF). Wiley. p. 343. ISBN 978-0471237341.

- Gay, Peter (May 17, 2006). Freud: A Life for Our Time. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 340. ISBN 978-0393328615.

- Ogrodniczuk, John (2013). "Historical overview of pathological narcissism. In: Understanding and Treating Pathological Narcissism". American Psychological Association: 15–26. doi:10.1037/14041-001.

- Jones, M.D., Ernest. "Essays In Applied Psychoanalysis Vol II". archive.org. Osmania University Library. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- Jones, Ernest (15 March 2007). Essays in Applied Psycho-Analysis. Lightning Source Inc. p. 472. ISBN 978-1-4067-0338-2. Retrieved 2012-01-22.

- Evans, Naiema. "History of Narcissism". deepblue.lib.umich.edu. University of Michigan.

- Strachey, James. "Standard Edition of the Complete Works of Sigmund Freud" (PDF). sas.upenn.edu. University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- Freud, Sigmund, On Narcissism: An Introduction, 1914

- SigmundFreud.net. "On Narcissism, 1914 by Freud". SigmundFreud.net. Sigmund Freud. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- Levy, Kenneth; Reynoso, John; Wasserman, Rachel; Clarkin, John (2007). Personality Disorders: Toward the DSM-V; Chapter 9, Narcissistic Personality Disorder. SAGE Publications, Inc. p. 235. ISBN 9781412904223.

- Bergmann, Martin S. (1987). Anatomy of Loving; Man's Quest to Know what Love I. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0449905531.

- Daum, Meghan (6 January 2011). "Narcissist -- give it a rest". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

The term has been misused and overused so flagrantly that it’s now all but meaningless when it comes to labeling truly destructive tendencies.

- Pilossoph, Jackie. "So, you think your spouse is a narcissist? You might not want to be so quick with the label". chicagotribune.com. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

the word is extremely overused, and I don’t think people truly understand what it means

- Gay, Peter (May 17, 2006). Freud: A Life for Our Time. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 340. ISBN 978-0393328615.

Some in fact exploited it as a handy term of abuse for modern culture or as a loose synonym for bloated self-esteemed.

- Malkin Ph.D., Craig. "Why We Need to Stop Throwing the "Narcissist" Label Around". psychologytoday.com. Psychology Today. Retrieved April 12, 2015.

The current promiscuous use of the term narcissist forevery minor instance of self-absorption, however, trivializes that very real pain.

- Campbell, W. Keith; Foster, Joshua D. (2007). "The Narcissistic Self: Background, an Extended Agency Model, and Ongoing Controversies". In Sedikides, Constantine; Spencer, Steven J. (eds.). The Self. Frontiers of Social Psychology. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1841694399.

- Horton, R. S.; Bleau, G.; Drwecki, B. (2006). "Parenting Narcissus: What Are the Links Between Parenting and Narcissism?" (PDF). Journal of Personality. 74 (2): 345–76. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.526.7237. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00378.x. PMID 16529580. See p. 347.

- Federn, Ernst (1972). "Thirty-five years with Freud: In honour of the hundredth anniversary of Paul Federn, M.D." Journal of Clinical Psychology. 32: 18–34 – via Wiley Online Library.

- Becker, Ernest (1973). "The Denial of Death" (PDF). The Free Press. Retrieved 2020-11-04.

- Kohut, Heinz (1966). "Forms and Transformation of Narcissism" (PDF). Narcissistic Abuse Rehab. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association. Retrieved 2020-11-04.

- Horton, Robert S; Bleau, Geoff; Drwecki, Brian. "Parenting Narcissus: What Are the LinksBetween Parenting and Narcissism?" (PDF). Wabash College. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Sedikides, C.; Rudich, E.A.; Gregg, A.P.; Kumashiro, Ml; Rusbult, C. (2004). "Are Normal Narcissists Psychologically Healthy?: self-esteem matters" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 87 (3): 400–16. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.400. hdl:1871/17274. PMID 15382988. S2CID 12903591.

- Kohut (1971). The Analysis of the Self. A systematic approach to the psychoanalytic treatment of narcissistic personality disorders. London: The University of Chicago Press.

- Brown, Nina W., The Destructive Narcissistic Pattern, 1998

- Morf, Caroline C.; Rhodewalt, Frederick (2001). "Unraveling the Paradoxes of Narcissism: A Dynamic Self-Regulatory Processing Model". Psychological Inquiry. 12 (4): 177–96. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1204_1. S2CID 2004430.

- Livesley WJ, Jang KL, Jackson DN, Vernon PA (December 1993). "Genetic and environmental contributions to dimensions of personality disorder". Am J Psychiatry. 150 (12): 1826–31. doi:10.1176/ajp.150.12.1826. PMID 8238637.

- DeWall, C. Nathan; Pond, Richard S.; Campbell, W. Keith; Twenge, Jean M. (August 2011). "Tuning in to psychological change: Linguistic markers of psychological traits and emotions over time in popular U.S. song lyrics". Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. 5 (3): 200–207. doi:10.1037/a0023195. ISSN 1931-390X.

- Luo, Yu L. L.; Cai, Huajian; Song, Hairong (2014-04-02). "A Behavioral Genetic Study of Intrapersonal and Interpersonal Dimensions of Narcissism". PLOS ONE. 9 (4): e93403. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...993403L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0093403. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3973692. PMID 24695616.

- Hurlbert, D.F.; Apt, C. (1991). "Sexual narcissism and the abusive male". Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 17 (4): 279–92. doi:10.1080/00926239108404352. PMID 1815094.

- Hurlbert, D.F.; Apt, C.; Gasar, S.; Wilson, N.E.; Murphy, Y. (1994). "Sexual narcissism: a validation study". Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 20 (1): 24–34. doi:10.1080/00926239408403414. PMID 8169963.

- Ryan, K.M.; Weikel, K.; Sprechini, G. (2008). "Gender differences in narcissism and courtship violence in dating couples". Sex Roles. 58 (11–12): 802–13. doi:10.1007/s11199-008-9403-9. S2CID 19749572.

- Schoenewolf, G. (2013). Psychoanalytic Centrism: Collected Papers of a Neoclassical Psychoanalyst. Living Center Press.

- Apt, C.; Hurlbert, D.F. (1995). "Sexual Narcissism: Addiction or Anachronism?". The Family Journal. 3 (2): 103–07. doi:10.1177/1066480795032003. S2CID 143630223.

- Rapport, Alan, Ph. D.Co-Narcissism: How We Adapt to Narcissistic Parents. The Therapist, 2005.

- Wilson, Sylia; Durbin, C. Emily (November 2011). "Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction During Early Childhood: Contributions of Parental and Child Personality Traits". Journal of Personality. 80 (5): 1313–1338. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2011.00760.x. ISSN 0022-3506. PMID 22433002.

- James I. Kepner, Body Process (1997) p. 73

- Banja, John, Medical Errors and Medical Narcissism, 2005

- Banja, John, (as observed by Eric Rangus) John Banja: Interview with the clinical ethicist

- A. J. DuBrin (2012). Narcissism in the Workplace.

- Brunell, A. B.; Gentry, W. A.; Campbell, W.; Hoffman, B. J.; Kuhnert, K. W.; DeMarree, K. G. (2008). "Leader emergence: The case of the narcissistic leader" (PDF). Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 34 (12): 1663–76. doi:10.1177/0146167208324101. PMID 18794326. S2CID 28823065. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-06-05.

- Hill, Victor (2005) Corporate Narcissism in Accounting Firms Australia, Pengus Books Australia

- Judge, T. A.; LePine, J. A.; Rich, B. L. (2006). "Loving Yourself Abundantly: Relationship of the Narcissistic Personality to Self- and Other Perceptions of Workplace Deviance, Leadership, and Task and Contextual Performance". Journal of Applied Psychology. 91 (4): 762–76. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.762. PMID 16834504.

- Bushman, B. J.; Baumeister, R. F. (1998). "Threatened egotism, narcissism, self-esteem, and direct and displaced aggression: Does self-love or self-hate lead to violence?". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 75 (1): 219–29. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.337.396. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.219. PMID 9686460. S2CID 145798157.

- Penney, L. M.; Spector, P. E. (2002). "Narcissism and counterproductive work behavior: Do bigger egos mean bigger problems?". International Journal of Selection and Assessment. 10 (1–2): 126–34. doi:10.1111/1468-2389.00199.

- Wislar, J. S.; Richman, J. A.; Fendrich, M.; Flaherty, J. A. (2002). "Sexual harassment, generalized workplace abuse and drinking outcomes: The role of personality vulnerability". Journal of Drug Issues. 32 (4): 1071–88. doi:10.1177/002204260203200404. S2CID 145170557.

- Simon Crompton, All about me (London 2007) p. 171

- Crompton, p. 171

- Golec de Zavala, A, et al. "Collective narcissism and its social consequences." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 97.6 (2009): 1074–96. Psyc articles. EBSCO. Web. 26 Mar. 2011.

- Bizumic, Boris, and John Duckitt. "My Group Is Not Worthy of Me": Narcissism and Ethnocentrism." Political Psychology 29.3 (2008): 437–53. Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection. EBSCO. Web. 9 Apr. 2011.

- Sorokowski, P; Sorokowska, A; Oleszkiewicz, A; Frackowiak, T; Huk, A; Pisanski, K (2015). "Selfie posting behaviors are associated with narcissism among men". Personality and Individual Differences. 85: 123–27. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.05.004.

- Lorentzen, Justin (2007). "The culture(s) of narcissism: simultaneity and the psychedelic sixties". In Gaitanidis, Anastasios; Curk, Polona (eds.). Narcissism – A Critical Reader. London: Karnac Books. p. 127. ISBN 978-1855754539.

- Lasch, Christopher (1979). The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations. Warner Books. ISBN 978-0446321044.

- Lorentzen, Justin (2007). "The culture(s) of narcissism: simultaneity and the psychedelic sixties". In Gaitanidis, Anastasios; Curk, Polona (eds.). Narcissism – A Critical Reader. London: Karnac Books. p. 129. ISBN 978-1855754539.

- Nelson, Kristina (2004). Narcissism in High Fidelity. Lincoln: iUniverse. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0595318049.

- Charles, Derber (15 June 2000). The Pursuit of Attention: Power and Ego in Everyday Life 2nd Edition (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195135497.

- Marshall, David P. (November 2004). "Fame's Perpetual Motion". M/C Journal. 7 (5). doi:10.5204/mcj.2401. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- DeWall, C. Nathan; Pond, Richard S. Jr.; Campbell, W. Keith; Twenge, Jean M. (August 2011). "Tuning in to psychological change: Linguistic markers of psychological traits and emotions over time in popular U.S. song lyrics". Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. 5 (3): 200–07. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.684.1672. doi:10.1037/a0023195.

- Twenge, Jean M. (2011). Campbell, W. Keith; Miller, Joshua D. (eds.). The Handbook of Narcissism and Narcissistic Personality Disorder: Theoretical Approaches, Empirical Findings, and Treatments. Hoboken NJ: John Wiley & Sons. p. 203. ISBN 9781118029268.

- Twenge, Jean M. (2011). Campbell, W. Keith; Miller, Joshua D. (eds.). The Handbook of Narcissism and Narcissistic Personality Disorder: Theoretical Approaches, Empirical Findings, and Treatments. Hoboken NJ: John Wiley & Sons. p. 202. ISBN 9781118029268.

- Miller; Lynam; Hyatt; Campbell (8 May 2017). "Controversies in Narcissism". Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 13: 291–315. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045244. PMID 28301765. S2CID 207585237.

- Zanor, Charles. "A Fate That Narcissists Will Hate: Being Ignored". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

Further reading

- Blackburn, Simon, Mirror, Mirror: The Uses and Abuses of Self-Love (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014)

- Twenge, Jean M.; Campbell, W., Keith The Narcissism Epidemic: Living in the Age of Entitlement (2009)

- Hotchkiss, Sandy; Masterson, James F., Why Is It Always About You? : The Seven Deadly Sins of Narcissism (2003)

- Brown, Nina W., Children of the Self-Absorbed: A Grown-up's Guide to Getting over Narcissistic Parents (2008)

- McFarlin, Dean, Where Egos Dare: The Untold Truth About Narcissistic Leaders – And How to Survive Them (2002)

- Brown, Nina W., The Destructive Narcissistic Pattern (1998)

- Golomb, Elan, Trapped in the Mirror – Adult Children of Narcissists in their Struggle for Self (1995)