North American F-100 Super Sabre

The North American F-100 Super Sabre is an American supersonic jet fighter aircraft that served with the United States Air Force (USAF) from 1954 to 1971 and with the Air National Guard (ANG) until 1979. The first of the Century Series of USAF jet fighters, it was the first USAF fighter capable of supersonic speed in level flight.[2] The F‑100 was designed by North American Aviation as a higher-performance follow-on to the F-86 Sabre air-superiority fighter.[3]

| F-100 Super Sabre | |

|---|---|

| |

| An F-100D Super Sabre over Rogers Dry Lake | |

| Role |

|

| Manufacturer | North American Aviation |

| First flight | 25 May 1953 |

| Introduction | 27 September 1954 |

| Retired | 1979, United States Air National Guard; 1988, Republic of China Air Force[1] |

| Primary users | United States Air Force Turkish Air Force Republic of China Air Force French Air Force |

| Produced | 1953–1959 |

| Number built | 2,294 |

| Developed from | North American F-86 Sabre |

| Developed into | North American F-107 |

_in_flight_060905-F-1234S-053.jpg.webp)

Adapted as a fighter-bomber, the F-100 was superseded by the high-speed Republic F-105 Thunderchief for strike missions over North Vietnam. The F‑100 flew extensively over South Vietnam as the air force's primary close air-support jet until being replaced by the more efficient subsonic LTV A-7 Corsair II.[4] The F‑100 also served in other NATO air forces and with other U.S. allies. In its later life, it was often referred to as the "Hun", a shortened version of "one hundred".[5]

Design and development

In January 1951, North American Aviation delivered an unsolicited proposal for a supersonic day fighter to the United States Air Force. Named Sabre 45 because of its 45° wing sweep, it represented an evolution of the F-86 Sabre. The mockup was inspected on 7 July 1951, and after over 100 modifications, the new aircraft was accepted as the F-100 on 30 November 1951. Extensive use of titanium throughout the aircraft was notable.[6] On 3 January 1952, the USAF ordered two prototypes followed by 23 F-100As in February and an additional 250 F-100As in August.

The YF-100A first flew on 25 May 1953, seven months ahead of schedule. It reached Mach 1.04 on this first flight in spite of being fitted with a derated XJ57-P-7 engine. The second prototype flew on 14 October 1953, followed by the first production F-100A on 9 October 1953. The USAF operational evaluation from November 1953 to December 1955 found the new fighter to have superior performance, but declared it not ready for wide-scale deployment due to various deficiencies in the design. These findings were subsequently confirmed during "Project Hot Rod" operational suitability tests.

Six F-100s arrived at the Air Proving Ground Command (APGC), Eglin Air Force Base, in August 1954. The Air Force Operational Test Center (AFOTC) was scheduled to use four of the fighters in operational suitability tests and the other two were to undergo armament tests by the Air Force Armament Center. The Tactical Air Division of the AFOTC was conducting the APGC testing under the direction of project office Lieutenant Colonel Henry W. Brown. Initial testing was completed by APGC personnel at Edwards Air Force Base.[7]

Particularly troubling was the yaw instability in certain flight conditions, which produced inertia coupling. The aircraft could develop a sudden yaw and roll, which would happen too fast for the pilot to correct and would quickly overstress the aircraft structure to disintegration. Under these conditions, North American's chief test pilot, George Welch, was killed while dive testing an early-production F-100A (s/n 52-5764) on 12 October 1954.

Another control problem stemmed from handling characteristics of the swept wing at high angles of attack. As the aircraft approached stall speeds, loss of lift on the tips of the wings caused a violent pitch-up. This particular phenomenon (which could easily be fatal at low altitude with insufficient time to recover) became known as the "Sabre dance".

Nevertheless, delays in the Republic F-84F Thunderstreak program pushed the Tactical Air Command (TAC) to order the raw F-100A into service. TAC also requested that future F-100s be fighter-bombers, with the capability of delivering nuclear bombs.

The F-100 was one of the first aircraft with a stabilator (all-moving tailplane).[8] Unlike modern stabilators which use an anti-servo tab, springs were attached to the control stick to provide increasing resistance to pilot input.

The North American F-107 was a follow-on Mach 2 development of the F-100 with the air intake moved above and behind the cockpit. It was not produced in favor of the Republic F-105 Thunderchief.

Operational history

The F-100A officially entered USAF service on 27 September 1954, with the 479th Fighter Wing at George AFB, California. By 10 November 1954, the F-100As suffered six major accidents[9] due to flight instability, structural failures, and hydraulic-system failures, prompting the USAF to ground the entire fleet until February 1955. The 479th finally became operational in September 1955. Due to ongoing problems, the USAF began phasing out the F-100A in 1958, with the last aircraft leaving active duty in 1961. By that time, 47 aircraft had been lost in major accidents.[10] Escalating tension due to construction of the Berlin Wall in August 1961 forced the USAF to recall the F-100As into active service in early 1962. The aircraft was finally retired in 1970.

The TAC request for a fighter-bomber was addressed with the F-100C, which flew in March 1954 and entered service on 14 July 1955, with the 450th Fighter Wing, Foster AFB, Texas. Operational testing in 1955 revealed that the F-100C was at best an interim solution, sharing all the flaws of the F-100A. The uprated J57-P-21 engine boosted performance, but continued to suffer from compressor stalls, but the F-100C was considered an excellent platform for nuclear toss bombing because of its high top speed. The inertia coupling problem was reasonably addressed with the installation of a yaw damper in the 146th F-100C, later retrofitted to earlier aircraft. A pitch damper was added starting with the 301st F-100C, at a cost of US$10,000 per aircraft.[10]

The addition of "wet" hardpoints meant the F-100C could carry a pair of 275 U.S. gal (1,040 L) and a pair of 200 U.S. gal (770 L) drop tanks. However, the combination caused a loss of directional stability at high speeds, so the four tanks were soon replaced by a pair of 450 U.S. gal (1,730 L) drop tanks. The 450s proved scarce and expensive and were often replaced by smaller 335 US gal (1,290 L) tanks. Most troubling to TAC was the fact that, as of 1965, only 125 F-100Cs were capable of using all non-nuclear weapons in the USAF inventory, particularly cluster bombs and AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missiles.[10] By the time the F-100C was phased out in June 1970, 85 had been lost in major accidents.

The definitive F-100D aimed to address the offensive shortcomings of the F-100C by being primarily a ground-attack aircraft with secondary fighter capabilities. To this effect, the aircraft was fitted with autopilot, upgraded avionics, and starting with the 184th production aircraft, AIM-9 Sidewinder capability. In 1959, 65 aircraft were modified to also fire the AGM-12 Bullpup air-to-ground missile. To further address the dangerous flight characteristics, the wingspan was extended by 26 in (66 cm) and the vertical tail area was increased by 27%.

The first F-100D (54–2121) flew on 24 January 1956, piloted by Daniel Darnell. It entered service on 29 September 1956 with the 405th Fighter Wing at Langley AFB. The aircraft suffered from reliability problems with the constant-speed drive, which provides constant-frequency current to the electrical systems. In fact, the drive was so unreliable that the USAF required it to have its own oil system to minimize damage in case of failure. Landing-gear and brake-parachute malfunctions claimed a number of aircraft, and the refueling probes had a tendency to break away during high-speed maneuvers. Numerous post-production fixes created such a diversity of capabilities between individual aircraft that by 1965, around 700 F-100Ds underwent High Wire modifications to standardize the weapon systems. High Wire modifications took 60 days per aircraft at a cost for the entire project of US$150 million.

On 26 March 1958, an F-100D fitted with an Astrodyne booster rocket making 150,000 lbf (667.2 kN) of thrust successfully performed a Zero-length launch.[11] This was accomplished with the addition of a large canister to the underside of the aircraft, which contained a black powder compound and was ignited electromechanically, driving the jet engine to minimal ignition point.[12] The capability was incorporated into late-production aircraft.

The F-100F two-seat trainer entered service in 1958. It received many of the same weapons and airframe upgrades as the F-100D, including the new afterburners. By 1970, 74 F-100Fs were lost in major accidents.

By 1961, England AFB, Louisiana, (401st Tactical Wing)had four fighter-bomber squadrons, the 612th, 613th, 614th, and the 615th (Fighting Tigers). During the Berlin crisis (approximately September 1961), the 614th was deployed to Ramstein Air Base, Germany, to support the West Germans. At the initial briefing, the 614th personnel were informed that due to the close proximity of the USSR, if an ICBM were to be launched, they would have only 30 minutes to launch the 614th's aircraft and retire to the nearest German bunker.

In 1966, the Combat Skyspot program fitted some F-100Ds with an X band radar transmitter to allow for ground-directed bombing in inclement weather or at night. In 1967, the USAF began a structural reinforcement program to extend the aircraft's service life from the designed 3,000 flying hours to 7,000. The USAF alone lost 500 F-100Ds, predominantly in accidents. After one aircraft suffered wing failure, particular attention was paid to lining the wings with external bracing strips. During the Vietnam War, combat losses constituted as many as 50 aircraft per year. After a major accident, the USAF Thunderbirds reverted from F-105 Thunderchiefs to the F-100D, which they operated from 1964 until it was replaced by the F-4 Phantom II in 1968.[13]

The F-100 was the subject of many modification programs over the course of its service. Many of these were improvements to electronics, structural strengthening, and projects to improve ease of maintenance. One of these was the replacement of the original afterburners of the J-57 engines with the more advanced afterburners from retired Convair F-102 Delta Dagger interceptors. This modification changed the appearance of the aft end of the F-100, doing away with the original "petal-style" exhaust. The afterburner modification started in the 1970s and solved maintenance problems with the old type, as well as operational problems, including compressor-stall issues.

By 1972, the F-100 was mostly phased out of USAF active service and turned over to tactical fighter groups and squadrons in the ANG. In ANG units, the F-100 was eventually replaced by the F-4 Phantom II, LTV A-7 Corsair II, and A-10 Thunderbolt II, with the last F-100 retiring in 1979, with the introduction of the F-16 Fighting Falcon. In foreign service, the Royal Danish Air Force and Turkish Air Force F-100s soldiered on until 1982.

Over the lifetime of its USAF service, 889 F-100 aircraft were destroyed in accidents, involving the deaths of 324 pilots.[14] The deadliest year for F-100 accidents was 1958, with 116 aircraft destroyed, and 47 pilots killed.[14]

After Super Sabres were withdrawn from service, a large number were converted into remote-controlled drones (QF-100) under the USAF Full Scale Aerial Target (FSAT) program for use as targets for various antiaircraft weapons, including missile-carrying fighters and fighter-interceptors, with FSAT operations being conducted primarily at Tyndall AFB, Florida. A few F-100s also found their way into civilian hands, primarily with defense contractors supporting USAF and NASA flight test activities at Edwards AFB, California.

Project Slick Chick

North American received a contract to modify six F-100As to RF-100As carrying five cameras, three Fairchild K-17 cameras (see Fairchild K-20 camera) in a trimetrogon mounting for photo mapping and two Fairchild K-38 cameras in a split vertical mounting with the cameras mounted horizontally, shooting via a mirror angled at 45° to reduce the effects of airframe vibrations. All gun armament was removed, and the cameras installed in the gun and ammunition bays were covered by a bulged fairing under the forward fuselage.[15]

The selected pilots trained on the F-100A at Edwards Air Force Base and George Air Force Base in California and then at Palmdale Air Force Base for training with the actual RF-100As with which they would be deployed. Flight tests revealed that the RF-100A in its intended operational fit of four external tanks was lacking in directional and longitudinal stability, requiring careful handling and close attention to speed limitations for the drop tanks.

Once pilot training was completed in April 1955, three aircraft were deployed to Bitburg Air Base in Germany, flying to Brookley AFB in Mobile, Alabama, cocooned, loaded on an aircraft carrier and delivered to Short Brothers at Sydenham, Belfast, for reassembly and preparation for flight. At Bitburg, they were allocated to Detachment 1 of the 7407th Support Squadron, and commenced operations flying over Eastern Bloc countries at high altitude (over 50,000 ft) to acquire intelligence on military targets. Many attempts were made to intercept these aircraft to no avail, with some photos of fighter airfields clearly showing aircraft climbing for attempted intercepts. The European detachment probably only carried out six missions between mid-1955 and mid-1956 when the Lockheed U-2 took over as the deep-penetration aerial reconnaissance asset.

Three RF-100As were also deployed to the 6021st Reconnaissance Squadron at Yokota Air Base in Japan, but details of operations there are not available. Two RF-100A aircraft were lost in accidents, one due to probable overspeeding, which caused the separation of one of the drop tanks and resulted in complete loss of control, and the other due to an engine flame-out. In mid-1958, all four remaining RF-100As were returned to the US and later supplied to the Republic of China Air Force in Taiwan.

Project High Wire

"High Wire" was a modernization program for selected F-100Cs, Ds and Fs. It comprised two modifications - an electrical rewiring upgrade and a heavy maintenance and inspect-and-repair as necessary (IRAN) upgrade. Rewiring upgrade operations consisted of replacing old wiring and harnesses with improved maintainable designs. Heavy maintenance and IRAN included new kits, modifications, standardized configurations, repairs, replacements, and complete refurbishment.

This project required all new manuals and incremented (i.e. -85 to -86) block numbers. All later-production models, especially the F models, included earlier High Wire modifications. New manuals included colored illustrations and had the Roman numeral (I) added after the aircraft number (i.e. T.O. 1F-100D(I)-1S-120, 12 January 1970).[16][17]

Total production was 2,294 aircraft.

Fighter and close air support missions

On 16 April 1961, six Super Sabres were deployed from Clark Air Base in the Philippines to Don Muang Royal Thai Air Force Base in Thailand for air-defense purposes, the first F-100s to enter combat in Southeast Asia.[18] From that date until their redeployment in 1971, the F-100s were the longest serving U.S. jet fighter-bomber to fight in the Vietnam War. They served as MiG combat air patrol (CAP) escorts for F-105 Thunderchiefs, Misty FACs, and Wild Weasels over North Vietnam, and were then relegated to close air support and ground attacks within South Vietnam.

On 18 August 1964, the first F-100D shot down by ground fire, piloted by 1st Lt Colin A. Clarke, of the 428th TFS; Clarke ejected and survived. On 4 April 1965, as escorts protecting F-105s attacking the Thanh Hoa Bridge, F-100 Super Sabres fought the USAF's first air-to-air jet combat duel in the Vietnam War, in which an F-100 piloted by Captain Donald W. Kilgus of the 416th Fighter Squadron shot down a Vietnam People's Air Force MiG-17, using cannon fire, while another fired AIM-9 Sidewinder missiles.[19] The surviving North Vietnamese pilot confirmed three of the MiG-17s had been shot down.[20] Although recorded by the U.S. Air Force as a probable kill, this represented the first aerial victory by the U.S. Air Force in Vietnam.[21] The small force of four MiG-17s, though, had penetrated the escorting F-100s to claim two F-105s.

The F-100 was soon replaced by the F-4C Phantom II for MiG CAP, which pilots noted suffered for lacking built-in guns for dogfights.[22]

The Vietnam War was not known for using activated Army National Guard, Air National Guard, or other U.S. Reserve units, but rather, had a reputation for conscription during the course of the war. During a confirmation hearing before Congress in 1973, Air Force General George S. Brown, who had commanded the 7th Air Force during the war, stated that five of the best Super Sabre squadrons in Vietnam were from the Air National Guard.[23] This included the (120 TFS) of the Colorado Air National Guard, the 136 TFS of the New York Air National Guard TFS, the 174 TFS of the Iowa Air National Guard, and the 188 TFS of the New Mexico Air National Guard. The fifth unit was a regular AF squadron manned by mostly air national guardsmen.

The Air National Guard F-100 squadrons increased the regular USAF by nearly 100 Super Sabres in theater, averaging, for the Colorado ANG F-100s, 24 missions a day, delivering ordnance and munitions with a 99.5% reliability rate.[24] From May 1968 to April 1969, the ANG Super Sabres flew more than 38,000 combat hours and more than 24,000 sorties. Between them, at the cost of seven F-100 Air Guard pilots killed (plus one staff officer) and the loss of 14 Super Sabres to enemy action, the squadrons expended over four million rounds of 20 mm shells, 30 million pounds of bombs and over 10 million pounds of napalm against their enemy.[25]

The Hun was also deployed as a two-seat F-100F model, which served as a "fast FAC" or Misty FAC in North Vietnam and Laos, spotting targets for other fighter-bomber aircraft, performing road reconnaissance, and conducting search-and-rescue missions as part of the top-secret Commando Sabre project, based out of Phu Cat and Tuy Hoa air bases.

By the war's end, 242 F-100 Super Sabres had been lost in Vietnam, as the F-100 was progressively replaced by the F-4 Phantom II and the F-105 Thunderchief.[26] The Hun had logged 360,283 combat sorties during the war and its wartime operations came to end on 31 July 1971.[27] The four fighter wings with F-100s flew more combat sorties in Vietnam than over 15,000 P-51 Mustangs had flown during World War II. After 1965, they did not fly into North Vietnam and mainly performed close air-support missions. Despite the April 1965 dogfight, the USAF classified the engagement as resulting in a "probable" kill, and no F-100 was ever officially credited with any aerial victories. No F-100 in Vietnam was lost to enemy fighters, but 186 were shot down by antiaircraft fire, seven were destroyed in Vietcong attacks on airbases, and 45 crashed in operational incidents.[28]

Wild Weasel

The F-100 was also the first Wild Weasel air defense suppression aircraft, whose specially trained crews were tasked with locating and destroying enemy missile defenses. Four F-100F Wild Weasel Is were fitted with APR-25 vector radar homing and warning receivers, IR-133 panoramic receivers with greater detection range, and KA-60 panoramic cameras. The APR-25 could detect early-warning radars and emissions from SA-2 Guideline tracking and guidance systems. These aircraft deployed to Korat Royal Thai Air Force Base, Thailand, in November 1965, began flying combat missions with the 388th Tactical Fighter Wing in December. They were joined by three more aircraft in February 1966. All Wild Weasel F-100Fs were eventually modified to fire the AGM-45 Shrike anti-radiation missile.

Algerian war

French Air Force Super Sabres of the EC 1/3 Navarre flew combat missions, striking from bases within France against targets in Algeria. The planes were based at Reims, refuelling at Istres on the return flight from Algeria.[29] The F-100 was the main fighter-bomber in the French Air Force during the 1960s, until it was replaced by the Jaguar.

Turkey

Turkish Air Force F-100 units were used during the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974. Together with F-104G Starfighters, they provided close air support to Turkish ground troops and bombed targets around Nicosia.[30] In March 1987, Turkish Super Sabres bombed Kurdish bases in northern Iraq.[31] On 14 September 1983, a pair of Turkish Air Force F-100F Super Sabres of 182 Filo “Atmaca” penetrated Iraqi airspace. A Mirage F1EQ of the Iraqi Air Force intercepted the flight and fired a Super 530F-1 missile at them. One of the Turkish fighter jets (s/n 56-3903) was shot down and crashed in Zakho valley near the Turkish-Iraqi border. The plane's pilots reportedly survived the crash and were returned to Turkey. The incident was not made public by either side, although some details surfaced in later years. The incident was revealed in 2012 by Turkish Defence Minister İsmet Yılmaz, in response to a parliamentary question by Republican People's Party (CHP) MP Metin Lütfi Baydar in the aftermath of the downing of a Turkish F-4 Phantom II in Syria, in 2012.[32]

Taiwan

Taiwan took delivery of 119 F-100As, 4 RF-100As, and 14 F-100Fs, and lost a number of F-100As and Fs in the course of service, but never lost a single RF-100As in either combat or accident. Those four RF-100As had never been sent on a reconnaissance mission over mainland China, as they could only produce photographic images of mediocre quality at best. Moreover, after each flying hour, the ground personnel had to spend over 100 hours on the aircraft maintenance. All of the RF-100As were returned to the US after one year and 11 months (1 January 1959 – 1 December 1960) in ROCAF service.

Achievements

Source: Knaack[10]

- The first operational aircraft in United States Air Force inventory capable of exceeding the speed of sound in level flight.

- On 29 October 1953, the first YF-100A prototype set a world speed record of 755.149 mph (656.207 kn, 1,215.295 km/h) at low altitude.

- On 20 August 1955, an F-100C set a supersonic world speed record of 822.135 mph (714.416 kn, 1,323.098 km/h).

- On 4 September 1955, an F-100C won the Bendix Trophy, covering 2,235 mi (2,020 nmi, 3,745 km) at an average speed of 610.726 mph (530.706 kn, 982.868 km/h).

- On 26 December 1956, two F-100Ds became the first-ever aircraft to successfully perform buddy refueling.

- On 13 May 1957, three F-100Cs set a new world distance record for single-engine aircraft by covering the 6,710 mi (5,835 nmi, 10,805 km) distance from London to Los Angeles in 14 hours and 4 minutes. The flight was accomplished using inflight refueling.

- On 7 August 1959, two F-100Fs became the first-ever jet fighters to fly over the North Pole.

- On 16 April 1961, the first USAF combat jets to enter the Vietnam War.

- On 4 April 1965, the first USAF aircraft to engage in aerial jet combat during the Vietnam War, while escorting F-105 Thunderchiefs to target.

- The United States Air Force Thunderbirds operated the F-100C from 1956 until 1964. After briefly converting to the F-105 Thunderchief, the team flew F-100Ds from July 1964 until November 1968, before converting to the F-4E Phantom II.

Costs

The costs are in contemporary United States dollars and have not been adjusted for inflation.[10]

| F-100A | F-100C | F-100D | F-100F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R&D | 23.2 million for the program or 10,134 prorated per aircraft | |||

| Airframe | 748,259 | 439,323 | 448,216 | 577,023 |

| Engine | 217,390 | 178,554 | 162,995 | 143,527 |

| Electronics | 8,549 | 12,050 | 10,904 | 13,667 |

| Armament | 19,905 | 21,125 | 66,230 | 66,332 |

| Ordnance | 20,807 | 12,125 | 8,684 | 3,885 |

| Flyaway cost | 1,014,910 | 663,181 | 697,029 | 804,445 |

| Additional modification costs | 224,048 | 110,559 | 105,604 | |

| Cost per flying hour | 583 | 583 | ||

| Maintenance cost per flying hour | 215 | 249 | 249 | 249 |

Variants

- YF-100A

- Prototype, model NA-180 two built, s/n 52-5754 and 5755.[33]

- YQF-100

- Nine test unmanned drone version: two D-models, one YQF-100F F-model,see DF-100F, and six other test versions.[34]

- F-100A

- Single-seat day fighter; 203 built, model NA-192.[33]

- RF-100A ("Slick Chick")

- Six F-100A aircraft modified for photo reconnaissance in 1954. Unarmed, with camera installations in lower fuselage bay. Used for overflights of Soviet Bloc countries in Europe and the Far-East. Retired from USAF service in 1958, the surviving four aircraft were transferred to the Republic of China Air Force and retired in 1960.

- F-100B

- See North American F-107

- F-100BI

- Proposed interceptor version of F-100B, did not advance beyond mock-up.

- F-100C

- Seventy Model NA-214 and 381 Model NA-217.[33] Additional fuel tanks in the wings, fighter-bomber capability, probe-and-drogue refueling capability, uprated J57-P-21 engine on late production aircraft. First flight: March 1954; 476 built.

- TF-100C

- One F-100C converted into a two-seat training aircraft.

- F-100D

- Single-seat fighter-bomber, more advanced avionics, larger wing and tail fin, landing flaps. First flight: 24 January 1956; 1,274 built.

- F-100F

- Two-seat training version, armament decreased from four to two cannon. First flight: 7 March 1957; 339 built.

- DF-100F

- This designation was given to one F-100F that was used as drone director.[34]

- NF-100F

- Three F-100Fs used for test purposes, the prefix "N" indicates that modifications prevented return to regular operational service.

- TF-100F

- Specific Danish designation given to 14 F-100Fs exported to Denmark in 1974 in order to distinguish these from the 10 F-100Fs delivered 1959–1961.

- QF-100

- Another 209 D and F models were ordered and converted to unmanned radio-controlled Full Scale Aerial Target[35] drones and drone directors for testing and destruction by modern air-to-air missiles used by current U.S. Air Force fighter jets.[34]

- F-100J

- Unbuilt all-weather export version for Japan

- F-100K

- Unbuilt design study for a two-seat F-100F powered by a J57-P-55 engine

- F-100L

- Unbuilt design study for a single-seat F-100D powered by a J57-P-55 engine

- F-100N

- Unbuilt version with simplified avionics for NATO customers

- F-100S

- Proposed French-built F-100F with Rolls-Royce Spey turbofan engine

Operators

Denmark

Denmark

- Royal Danish Air Force

- Flyvevåbnet operated a total of 72 aircraft. 48 F-100Ds and 10 Fs were delivered to Denmark from 1959 to 1961 as MDAP equipment. The F-100 replaced the F-84G Thunderjet as a strike fighter in three squadrons; 725, 727 and 730. The F-100s of Eskadrille 725 were replaced by Saab F-35 Draken in 1970 and in 1974 14 two-seated ex-USAF TF-100F were bought. The last Danish F-100s were retired from service in 1982, replaced by F-16s. The surviving MDAP F-100s were transferred to Turkey (21 F-100Ds and two F-100Fs), while six TF-100Fs were sold for target towing.[36][37]

France

France

- The Armée de l'Air was the first non-US air force to receive the F-100 Super Sabre. The first aircraft arrived in France on 1 May 1958. A total of 100 aircraft (85 F-100Ds and 15 F-100Fs) were supplied to France, and assigned to the NATO 4th Allied Tactical Air Force. They were stationed at German-French bases. French F-100s were used on combat missions flying from bases in France against targets in Algeria. In 1967, France left NATO, and German-based F-100s were transferred to France, using bases vacated by the USAF. The last unit on F100D/F was the Escadron 4/11 Jura, based at Djibouti, which kept the Super Sabre until 1978.

Taiwan (Republic of China)

Taiwan (Republic of China)

- Republic of China Air Force

- The only non-US air force to operate the F-100A model. The first F-100 was delivered in October 1958. It was followed by 15 F-100As in 1959, and by 65 more F-100As in 1960. In 1961, four unarmed RF-100As were delivered.[38] Additionally, 38 ex-USAF/Air National Guard F-100As were delivered later, to bring the total strength to 118 F-100As and four RF-100As. F-100As were retrofitted with the F-100D vertical tail with its AN/APS-54 tail-warning radar and equipped to launch Sidewinder air-to-air missiles. Several were lost in intelligence missions over the People's Republic of China.

Turkey

Turkey

- The Turk Hava Kuvvetleri received 206 F-100C, D and F Super Sabres. Most came from USAF stocks, and 21 F-100Ds and two F-100Fs were supplied by Denmark. Turkish F-100s saw extensive action during the 1974 military operation against Cyprus.

United States

United States

- List of F-100 units of the United States Air Force

Gallery

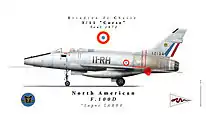

F100 D E.C 3/11 "Corse"

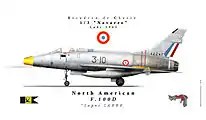

F100 D E.C 3/11 "Corse" F100 D E.C 1/3 "Navarre"

F100 D E.C 1/3 "Navarre" F100 D E.C 4/11 "Jura"

F100 D E.C 4/11 "Jura" F100 C Skyblazers Aerobatic Team

F100 C Skyblazers Aerobatic Team

Surviving aircraft

Denmark

- F-100F

- 56-3927/GT-927 – Denmark Flying Museum, Stauning

Germany

- F-100D

- 54-2136 French Air Force – Schwäbisches Bauern Technical Museum, Eschach-Seifertshofen.[40]

- 54-2185 French Air Force – Schwäbisches Bauern Technical Museum, Eschach-Seifertshofen.[41]

- F-100F

- 56-3944 United States Air Force – Flugausstellung Leo Junior, Hermeskeil.[42]

Italy

- F-100D

- 54-2290 – Aviano Air Base gate guardian; marked as 56-2927 "Thor's Hammer" used in Vietnam, wrong colors though.

Netherlands

- F-100D

- 54-2265 - (painted as 54–1871, 32nd FIS) – On display at the Nationaal Militair Museum, Soesterberg. After service with the French Air Force it was returned to USAF, repainted in USAF markings and in 1976 to gate guardian at RAF Wethersfield, England. It was then removed 20 January 1988 and reported at the time to be destined for AMARC, to be held in storage on behalf of USAFM (now NMUSAF).[43]

Taiwan

- F-100A

Turkey

- F-100C

- F-100D

- F-100F

United Kingdom

- F-100D

- 54-2157 – North East Aircraft Museum, Sunderland.[52]

- 54-2165 – Imperial War Museum, Duxford[53]

- 54-2174 – Midland Air Museum, Coventry.[54]

- 54-2196 – Norfolk and Suffolk Aviation Museum, Bungay.[55]

- 54-2223 – Newark Air Museum, Newark-on-Trent.[56]

- 54-2613 – Dumfries and Galloway Aviation Museum, Dumfries.[57]

- F-100F

- 56-3938 French Air Force – Lashenden Air Warfare Museum, Ashford where an aircraft accident at the museum damaged 938 and the remains were shipped to the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson AFB in Dayton, Ohio, United States.[58]

United States

Airworthy

- F-100F

YF-100A

- 52-5755 – Century Circle, West Gate at Air Force Flight Test Center Museum, Edwards AFB, California.[64]

F-100A

- 52-5759 – USAF History and Traditions Museum, Lackland AFB, Texas.[65]

- 52-5760 – Museum Desert Storate, Air Force Flight Test Center Museum, Edwards AFB, California.[66]

- 52-5761 – New England Air Museum, Bradley International Airport, Connecticut.[67]

- 52-5762 – Grand Haven Memorial Airpark, Grand Haven, Michigan.[68]

- 52-5770 – Travis AFB Heritage Center, Vacaville, California.[69]

- 52-5773 – Commemorative Air Force Headquarters, Midland, Texas.[70]

- 52-5777 – Hill Aerospace Museum, Hill AFB, Utah.[71]

- 53-1532 – 150th Special Operations Wing, New Mexico Air National Guard area, Kirtland AFB, Albuquerque, New Mexico.[72]

- 53-1533 – Baxter Memorial Park, Melrose, New Mexico.[73]

- 53-1553 – South Dakota Air and Space Museum, Rapid City, South Dakota.[74]

- 53-1559 – 178th Fighter Wing / Springfield-Beckley Municipal Airport, Springfield, Ohio.[75]

- 53-1573 – Seymour Johnson AFB, North Carolina.[76]

- 53-1578 – 140th Fighter Wing / Colorado Air National Guard compound, Buckley Space Force Base, Aurora, Colorado.[77]

- 53-1600 – Tucumcari Historical Museum, Tucumcari, New Mexico.[78]

- 53-1629 – Ebing Air National Guard Base – 188th Fighter Wing, Fort Smith, Arkansas.[79]

- 53-1684 – Historic Aviation Memorial Museum, Tyler, Texas.[80]

- 53-1688 – stored for Raytheon at the Mojave Airport, Mojave, California.[81]

F-100C

- 53-1709 (painted as F-100D 55–2879) – Castle Air Museum (former Castle AFB), Atwater, California[82]

- 53-1712 – Grissom Air Museum, Grissom ARB (former Grissom AFB), Peru, Indiana.[83]

- 53-1716 – Luke Air Force Base Air Park, Luke AFB, Phoenix, Arizona.[84]

- 54-1748 – Holt Heritage Airpark, Mountain Home AFB, Boise, Idaho.[85]

- 54-1752 – Dyess Linear Air Park, Dyess AFB, Texas.[86]

- 54-1753 – Southern Museum of Flight, Birmingham, Alabama.[87]

- 54-1784 – Prairie Aviation Museum, Bloomington, Illinois. Formerly at Octave Chanute Aerospace Museum, former Chanute AFB, Rantoul, Illinois.[88][89]

- 54-1785 – Yankee Air Museum, Belleville, Michigan[90]

- 54-1786 – March Field Air Museum, March ARB (former March AFB), Riverside, California.[91]

- 54-1823 – Pima Air & Space Museum (adjacent to Davis-Monthan AFB), Tucson, Arizona.[92]

- 54-1986 (painted as F-100C 54-1954 as flown by former northwest Florida resident and Medal of Honor recipient, Colonel George Bud Day, USAF Ret Dec) – Air Force Armament Museum, Eglin AFB, Florida.[93]

- 54-1993 – Freedom Historical Air Park, McConnell AFB, Wichita, Kansas.[94]

- 54-2005 – 185th Air Refueling Wing / Sioux City Air National Guard Base, Sioux Gateway Airport, Sioux City, Iowa.[95]

- 54-2091 – Yanks Air Museum, Chino, California.[96][97]

- 54-2106 – Volk Field Air National Guard Base, Wisconsin.[98]

F-100D

- 54-2145 – Air Power Park near Langley AFB in Hampton, Virginia.[99]

F-100D on display at Sheppard AFB.

F-100D on display at Sheppard AFB. - 54-2151 – Sheppard AFB Air Park, Sheppard AFB, Texas.[100]

- 54-2281 – Harry Bonsall Park, Glendale, Arizona[101]

- 54-2299 – Joe Davies Heritage Airpark, Air Force Plant 42, Palmdale, California[102]

- 55-2855 – Toledo ANGB, Toledo Express Airport, Toledo, Ohio.[103]

- 55-2884 – 121st Air Refueling Wing / Rickenbacker ANGB, Columbus, Ohio.[104]

- 55-3503 – Pueblo Weisbrod Aircraft Museum, Pueblo, Colorado.[105]

- 55-3595 – Nellis AFB, Nevada.[106]

- 55-3650 – 180th Fighter Wing / Toledo Air National Guard Base, Swanton, Ohio.[107]

- 55-3667 – Missouri Air National Guard / Whiteman Air Force Base, Knob Noster, Missouri.[108]

- 55-3678 – Maxwell AFB Air Park, Maxwell AFB, Alabama.[109]

- 55-3754 – National Museum of the United States Air Force, Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio.[110]

- 55-3805 – Connecticut ANGB – 103d Airlift Wing area, Windsor Locks, Connecticut.[111]

- 56-2928 – Dobbins ARB, Marietta, Georgia.[112]

- 56-2940 – Cannon AFB, New Mexico.[113]

- 56-2967 – Myrtle Beach, South Carolina.[114]

- 56-2993 – New York ANGB – 107th Airlift Wing area, Niagara Falls, New York.[115]

- 56-2995 – Massachusetts ANGB – 102nd Intelligence Wing compound, Otis ANGB, Falmouth, Massachusetts.[116]

- 56-3000 – Lackland AFB / Kelly Field Annex (former Kelly AFB) – 149th Fighter Wing area, San Antonio, Texas.[117]

- 56-3008 – Massachusetts ANGB – 104th Fighter Wing complex, Westfield, Massachusetts.[118]

- 56-3020 – NAS JRB New Orleans, 159th Fighter Wing area, New Orleans, Louisiana.[119]

- 56-3022 – Mansfield Lahm ANGB – 179th Airlift Wing area, Mansfield, Ohio.[120]

- 56-3025 – Selfridge Military Air Museum, Mount Clemens, Michigan.[121]

- 56-3046 – Randall County Veterans Park, Amarillo, Texas.[122]

- 56-3055 – Tucson Air National Guard Base - 162nd Fighter Wing complex, Tucson, Arizona.[123]

- 56-3081 – MAPS Air Museum, Akron/Canton Airport Ohio.[124]

- 56-3141 – Planes of Fame, Chino, California.[125]

- 56-3154 – Lone Star Flight Museum, Houston, Texas.[126]

- 56-3187 – Sioux Falls ANGB – 114th FG, Sioux Falls, South Dakota.[127]

- 56-3208 – Fessenden, North Dakota.[128]

- 56-3220 – Holloman AFB, New Mexico.[129]

- 56-3288 – Aerospace Museum of California, Sacramento, California.[130]

- 56-3299 – Buckley Space Force Base – 140th Fighter Wing area, Aurora, Colorado.[131]

- 56-3320 – Terre Haute ANGB – 181st Fighter Wing area, Terre Haute, Indiana.[132]

- 56-3417 – Wings Over the Rockies Air and Space Museum (former Lowry AFB), Denver, Colorado.[133]

- 56-3426 – Des Moines ANGB – 132nd Fighter Wing area, Des Moines, Iowa.[134]

- 56-3434 – Previously at Arkansas National Guard HQ, Little Rock, Arkansas.[135] relocated to Valiant Air Command Warbird Museum, Space Coast Regional Airport, Titusville, Florida in 2015 for restoration.[136]

- 56-3440 – Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, Fairfax County, Virginia.[137]

F-100F

- 56-3727 – Warrior Park, Davis-Monthan AFB, Arizona.[138]

- 56-3730 – USAF Academy, Colorado.[139]

- 56-3812 – Veterans Park, Duncan, Arizona.[140]

- 56-3813 – Riverside Park, Independence, Kansas[141]

- 56-3814 – Bay Street Park, Texas City, Texas.[142]

- 56-3819 – Saint Maries Municipal Airport, Saint Maries, Idaho.[143]

- 56-3822 – Clay County Veterans Memorial Park, Lineville, Alabama.[144]

- 56-3825 – Aurora Municipal Airport, Aurora, Nebraska.[145]

- 56-3832 – Evergreen Aviation and Space Museum, McMinnville, Oregon.[146]

- 56-3837 – National Museum of the United States Air Force, Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio.[147]

- 56-3855 – Las Cruces Municipal Airport, Las Cruces, New Mexico.[148]

- 56-3897 – Atlantic City ANGB – 177th Fighter Wing complex, Atlantic City, New Jersey.[149]

- 56-3894 – Selfridge Military Air Museum, Selfridge Air National Guard Base, Mount Clemens, Michigan.[150]

- 56-3899 – Glenn L. Martin Aviation Museum, Middle River, Maryland.[151]

- 56-3904 – Aviation Cadet Museum, Silver Wings Field, Eureka Springs, Arkansas.[152]

- 56-3905 – Glenn L. Martin Aviation Museum, Middle River, Maryland.[153]

- 56-3929 – Fayette Regional Air Center Airport, La Grange, Texas.[154]

- 56-3982 – Hangar 25 Air Museum, Big Spring, Texas.[155]

- 56-3990 – Commemorative Air Force – Highland Lakes Squadron, Burnet, Texas.[156]

- 58-1232 – Museum of Aviation, Robins AFB, Warner Robins, Georgia (relocated from the now-closed Brooks AFB, TX)

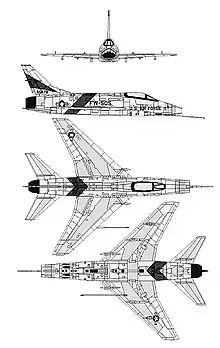

Specifications (F-100D)

Data from Quest for Performance[157]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 50 ft (15 m)

- Wingspan: 38 ft 9 in (11.81 m)

- Height: 16 ft 2.75 in (4.9467 m)

- Wing area: 400 sq ft (37 m2)

- Aspect ratio: 3.76

- Airfoil: NACA 64A007[158]

- Zero-lift drag coefficient: CD0.0130

- Drag area: 5.0 sq ft (0.46 m2)

- Empty weight: 21,000 lb (9,525 kg)

- Gross weight: 28,847 lb (13,085 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 34,832 lb (15,800 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Pratt & Whitney J57-P-21/21A afterburning turbojet engine, 10,200 lbf (45 kN) thrust dry, 16,000 lbf (71 kN) with afterburner

Performance

- Maximum speed: 924 mph (1,487 km/h, 803 kn)

- Maximum speed: Mach 1.4

- Range: 1,995 mi (3,211 km, 1,734 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 50,000 ft (15,000 m)

- Rate of climb: 22,400 ft/min (114 m/s)

- Lift-to-drag: 13.9

- Wing loading: 72.1 lb/sq ft (352 kg/m2)

- Thrust/weight: 0.55

Armament

- Guns: 4× 20 mm (0.787 in) M39A1 revolver cannon each with 200 rounds per gun

- Hardpoints: 6 with a capacity of 7,040 lb (3,190 kg), with provisions to carry combinations of:

- Missiles: ** 4× AIM-9 Sidewinder or

- 2× AGM-12 Bullpup or

- 2× or 4× LAU-3/A 2.75" (70 mm) unguided rocket dispenser[159]

- Bombs: Conventional bombs or Mark 7, Mk 28, Mk 38, or Mk 43 nuclear bombs[160]

Avionics

See also

- Flight airspeed record

- 1959 Kadena Air Base F-100 crash

- Ejection seat

Related development

- North American F-86 Sabre

- North American FJ-4 Fury

- North American F-107

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- Dassault Super Mystère

- Dassault Étendard IV

- Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-19

- Vought F-8 Crusader

Related lists

- List of military aircraft of the United States

- List of fighter aircraft

References

Notes

- "Historical Listings: China, Nationalist (Taiwan) (NCH)." Archived 10 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine World Air Forces. Retrieved: 19 May 2011.

- Rendall, Ivan (1999). Rolling Thunder: jet combat from World War II to the Gulf War (First U.S. ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster Inc. p. 110. ISBN 0-684-85780-4.

- "North American F-100C "Super Sabre"". fas.org. 29 June 1999. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- "A-7 Corsair II". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre; Historical Snapshot". Boeing. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- "Production Fighter Tops Speed of Sound." Popular Mechanics, December 1953, p. 81.

- Playground News, 26 August 1954, "6 F-100s At Eglin For Test."

- Abzug, Malcolm J.; Larrabee, E. Eugene (23 September 2002). Airplane Stability and Control: A History of the Technologies that Made Aviation Possible. Cambridge University Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-107-32019-2. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

One of the first all-moving tail applications was the North American F-100 Super Sabre.

- Including the death of British Air Commodore Geoffrey D. Stephenson while on an exchange tour

- Knaack, Marcelle Size. Encyclopedia of U.S. Air Force Aircraft and Missile Systems: Volume 1 Post-World War II Fighters 1945–1973. Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History, 1978. ISBN 0-912799-59-5.

- "North American Aviation NF-100D (56-2904)". thexhunters.com. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- Davis, Jim (20 May 2008). "1958 F-100 Uses Short "Runway"". YouTube. Archived from the original on 13 November 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- Martin Caidin's book Thunderbirds was written while the team flew F-100s, he was the only journalist to ever fly with them.

- "Official USAF F-100 accident rate table (PDF)." Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine afsc.af.mil. Retrieved: 12 April 2011.

- Gordon, Doug. "Through the Curtain". Flypast, December 2009. Key Publishing. Stamford. ISSN 0262-6950.

- USAF F-100 Super Sabre – Flight Manual – Technical Order: 1F-100D(I)-1S-120; 12 January 1970.

- USAF F-100 Super Sabre – Flight Manual – Technical Order: 1F-100C(I)-1S-65; 2 February 1971.

- Anderton 1987, p. 57.

- Davies and Menard 2011, cover image of F-100 attacking MiG-17, p. 21: photo of Kilgus's F-100.

- Toperczer, Dr. Istvan. Air War Over North Viet Nam: The Vietnamese People's Air Force 1949–1977. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications, 1998. ISBN 0-89747-390-6.

- Dorr, Robert F. (18 April 2014). "F-100 Versus MiG-17: The Air Battle Nobody Told You About". defensemedianetwork.com. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- Anderton 1987, p. 71.

- Anderton 1987, p. 136.

- Anderton 1987, p. 144.

- Anderton 1987, pp. 136, 145.

- Hobson 2001, p. 269.

- Thompson 2008, pp. 73–74.

- Dorr, Robert F. (12 September 2013). "F-100 Super Sabre Flew Most Missions in Vietnam". defensemedianetwork.com. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- Flintham 1989, p. 82.

- Flintham 1989, pp. 16–17.

- Flintham 1989, p. 180.

- "The Aviationist » 30 years later, Ankara admits Turkish Air Force jet was shot down by Iraq". The Aviationist. 6 September 2012. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- Thompson 1999, p. 64.

- Baugher, Joe. "QF-100 Drone." USAAC/USAAF/USAF Fighters, 30 January 2010. Retrieved: 12 April 2011.

- Gustin, Emmanuel. "Acronyms and Codenames FAQ, FSAT". hazegray.org. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- page 46 & 54 in Jan Jørgensen: "Flyvevåbnet – Scenes from Danish military aviation history", 2010, Nordic Airpower, ISBN 978-87-993688-0-8 (in English)

- Schrøder, Hans (1991). "Royal Danish Airforce". Ed. Kay S. Nielsen. Tøjhusmuseet, 1991, p. 1–64. ISBN 87-89022-24-6.

- "North American RF-100A Super Sabre". joebaugher.com. 27 November 1999. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/55-2736." Archived 25 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Virtual Aviation Museum. Retrieved: 7 March 2013.

- "F-100F on Display." Archived 25 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Virtual Aviation Museum. Retrieved: 4 September 2009.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/54-2185." Archived 25 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Virtual Aviation Museum. Retrieved: 7 March 2013.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3944." Archived 25 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Virtual Aviation Museum. Retrieved: 4 September 2009.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/54-2265." nmm.nl. Retrieved: 14 October 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/53-1550." airliners.net. Retrieved: 7 March 2013.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/53-1571." airliners.net. Retrieved: 7 March 2013.

- www.facebook.com " https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=797758016987606&set=a.308294772600602.69586.100002602450559&type=1&theater." Retrieved 7 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - "F-100 Super Sabre/53-1589." airliners.net Retrieved: 7 March 2013.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/53-1696." airliners.net. Retrieved: 7 March 2013.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/54-2009/3-089". tayyareci.com. Retrieved: 12 March 2011.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/54-2245/E-245". tayyareci.com. Retrieved: 12 March 2011.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3788/8-788". tayyareci.com. Retrieved: 12 March 2011.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/54-2157." North East Aircraft Museum. Retrieved: 16 June 2013.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/54-2165." Imperial War Museum Duxford Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/54-2174." Midland Air Museum. Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/54-2196." Norfolk and Suffolk Aviation Museum. Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/54-2223." Newark Air Museum. Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/54-2613." Dumfries and Galloway Aviation Museum. Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3938." Lashendene Air Warfare Museum. Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "FAA Registry: N26AZ." faa.gov Retrieved: 27 July 2021.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3844." Collings Foundation Retrieved: 12 June 2015.

- "FAA Registry: N416FS." faa.gov Retrieved: 27 July 2021.

- "FAA Registry: N2011V." faa.gov Retrieved: 27 July 2021.

- "FAA Registry: N419FS." faa.gov Retrieved: 27 July 2021.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/52-5755." Air Force Flight Test Museum. Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/52-5759." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/52-5760." Archived 2 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine Air Force Flight Test Museum. Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/52-5761." New England Air Museum. Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/52-5762. aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/52-5770." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/52-5773." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/52-5777." Hill Aerospace Museum. Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/53-1532." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/53-1533." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/53-1553." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/53-1559." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/53-1573." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/53-1578." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/53-1600." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 12 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/53-1629." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 12 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/53-1684." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 12 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/53-1688." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 12 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/53-1709." Castle AFB Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/53-1712." Grissom Air Museum. Retrieved: 5 March 2013.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/53-1716." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/54-1748." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 12 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/54-1752." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/54-1753." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "USAF Serial Number Search (54-1784)". Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- "Prairie Aviation Museum (F-100)". Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- "USAF Serial Number Search (54-1785)". Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/54-1786." March Field Museum. Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/54-1823." Pima Air & Space Museum. Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/54-1986." Air Force Armament Museum. Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/54-1993." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/54-2005." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/54-2091." Yanks Air Museum. Retrieved: 5 March 2013.

- "FAA Registry: N2011M." faa.gov Retrieved: 27 July 2021.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/54-2106." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/54-2145." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/54-2151." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/54-2281." City of Glendale, Arizona. Retrieved: 2 November 2013.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/54-2299." Archived 29 October 2015 at Archive-It City of Palmdale, California. Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/55-2855." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 12 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/55-2884." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/55-3503." Archived 30 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine Pueblo Weisbrod Aircraft Museum. Retrieved: 6 March 2013.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/55-3595." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/55-3650." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/55-3667." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/55-3678." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/55-3754." National Museum of the USAF. Retrieved: 16 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/55-3805." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-2928." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-2940." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-2967." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 12 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-2993." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-2995." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3000." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3008." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3020." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3022." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 12 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3025." Selfridge Military Air Museum. Retrieved: 12 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3046." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 12 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3055." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved : 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3081." MAPS Air Museum. Retrieved: 6 March 2013.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3141." Archived 6 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine Planes of Fame. Retrieved: 12 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3154." Archived 30 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine Lone Star Flight Museum. Retrieved: 6 March 2013.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3187." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3208." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 12 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3220." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100D Super Sabre/56-3288." Aerospace Museum of California. Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3299." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3320." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3417." Wings Over the Rockies Museum. Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3426." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3434." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 12 June 2015;

- https://www.nbbd.com/godo/vac/un-scramble/1610-unscramble.pdf

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3440." Archived 7 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3727." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3730." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3812." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 12 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3813." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3814." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 12 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3819." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 12 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3825." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 12 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3825." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 12 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3832." Archived 30 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine Evergreen Aviation and Space Museum. Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "North American F-100F Super Sabre." National Museum of the USAF. Retrieved: 12 September 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3855." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 12 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3897." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3894." Selfridge Military Air Museum. Retrieved: 12 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3899." Archived 1 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine Glenn L. Martin Aviation Museum. Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3904." Aviation Cadet Museum. Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3905." Archived 1 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine Glenn L. Martin Aviation Museum. Retrieved: 1 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3929." aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 12 June 2015.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3982." Hangar 25 Air Museum. Retrieved: 23 July 2017.

- "F-100 Super Sabre/56-3990." Archived 26 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine CAF – Highland Lakes Squadron. Retrieved: 12 June 2015.

- Loftin, L.K. Jr. Quest for Performance: The Evolution of Modern Aircraft. NASA SP-468. Retrieved: 22 April 2006.

- Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- Rhodes, Jeffrey P. "Fighters." USAF Magazine: Archives, 20 February 1997, p. 15.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Collections". airandspace.si.edu.

Bibliography

- Anderton, David A. North American F-100 Super Sabre. London: Osprey Publishing Limited, 1987. ISBN 0-85045-662-2 .

- Başara, Levent. F-100 Super Sabre in Turkish Air Force – Türk Hava Kuvvetlerinde F-100 Super Sabre. Hobbytime, Ankara-Turkey, 2011. EAN 8680157170010 (in Turkish and English)

- Davies, Peter E. North American F-100 Super Sabre. Ramsbury, Wiltshire, UK: Crowood Press, 2003. ISBN 1-86126-577-8.

- Davies, Peter E. and David W. Menard. F-100 Super Sabre Units of the Vietnam War (Osprey Combat Aircraft, No. 89) Oxford, UK: Osprey, 2011. ISBN 978-1-84908-446-8.

- Donald, David (June 2004). "North American F-100 Super Sabre". Century Jets: USAF Frontline Fighters of the Cold War. London: AIRtime Publishing Inc., 2003. ISBN 1-880588-68-4.

- Drendel, Lou. Century Series in Color (Fighting Colors). Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications, 1980. ISBN 0-89747-097-4.

- Flintham, Victor (1989). Air wars and aircraft: A Detailed Record of Air Combat, 1945 to the Present. Arms and Armour Press. ISBN 0-85368-779-X.

- Gordon, Doug. "Through the Curtain". Flypast, December 2009. ISSN 0262-6950

- Gordon, Doug (March–April 2001). "Turbulent Times: The USAF's 20th TFW in the 1950s, Part Two - Super Sabres". Air Enthusiast (92): 2–8. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Goodrum, Alastair (January–February 2004). "Down Range: Losses over the Wash in the 1960s and 1970s". Air Enthusiast (109): 12–17. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Gunston, Bill. Fighters of the Fifties. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Specialty Press Publishers & Wholesalers, Inc., 1981. ISBN 0-933424-32-9.

- Hobson, Chris. Vietnam Air Losses: United States Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps Fixed-Wing Aircraft Losses in Southeast Asia, 1961–1973. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press, 2001. ISBN 1-85780-115-6.

- Jenkins, Dennis R. and Tony R. Landis. Experimental & Prototype U.S. Air Force Jet Fighters. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1-58007-111-6.

- Pace, Steve. X-Fighters: USAF Experimental and Prototype Fighters, XP-59 to YF-23. St. Paul, Minnesota: Motorbooks International, 1991. ISBN 0-87938-540-5.

- Thompson, Kevin F. "North American NA-180>NA-262 YF-100A/F-100A/C/D/F Super Sabre." North American: Aircraft 1934–1999 – Volume 2. Santa Ana, California: Johnathan Thompson, Greens, Inc., 1999. ISBN 0-913322-06-7.

- Thompson, Warren E. "Centuries Series: F-100 Super Sabre." Combat Aircraft, Volume 9, Issue 3, June–July 2008, London: Ian Allan Publishing.

- Weaver, Michael E. "The F-100 Super Sabre as an Air Superiority Fighter." Air Power History. 67: 1 (Spring 2020), 8-15.

External links

- JoeBaugher: F-100 Super Sabre Index

- JoeBaugher: Foreign Air Forces with F-100s

- F-100 Photo Database

- Warbird Alley: F-100 page – Information about privately owned F-100s

- F-100 Super Sabre Survivors, Static displays, locations, serial numbers, and links

- "Supersonic Fighter" a 1955 Flight article on the F-100 Super Sabre by Bill Gunston (missing pages)

- Video of an F-100 (s/n 56-2904) Zero Length Launch at British Pathe (1958, silent, b/w)

- The Intake - The Journal of the Super Sabre Society – full archives dating back to 2006

- Bibliography for further reading