Lockheed F-117 Nighthawk

The Lockheed F-117 Nighthawk is a retired American single-seat, twin-engine stealth attack aircraft developed by Lockheed's secretive Skunk Works division and operated by the United States Air Force (USAF). It was the first operational aircraft to be designed with stealth technology.

| F-117 Nighthawk | |

|---|---|

| |

| F-117 flying over mountains in Nevada in 2002 | |

| Role | Stealth attack aircraft[1] |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Lockheed Corporation |

| First flight | June 18, 1981 |

| Introduction | October 1983[2] |

| Retired | 22 April 2008[3] (Combat use) |

| Status | Used as training aircraft as of 2022 |

| Primary user | United States Air Force |

| Number built | 64 (5 YF-117As, 59 F-117As) |

| Developed from | Lockheed Have Blue |

The F-117 was based on the Have Blue technology demonstrator. The Nighthawk's maiden flight took place in 1981 at Groom Lake, Nevada, and the aircraft achieved initial operating capability status in 1983. The aircraft was shrouded in secrecy until it was revealed to the public in 1988. Of the 64 F-117s built, 59 were production versions, with the other five being prototypes.

The F-117 was widely publicized for its role in the Persian Gulf War of 1991. Although it was commonly referred to as the "Stealth Fighter", it was strictly an attack aircraft. F-117s took part in the conflict in Yugoslavia, where one was shot down by a surface-to-air missile (SAM) in 1999. The U.S. Air Force retired the F-117 in April 2008, primarily due to the fielding of the F-22 Raptor. Despite the type's official retirement, a portion of the fleet has been kept in airworthy condition, and Nighthawks have been observed flying since 2009.[4]

Development

Background and Have Blue

In 1964, Pyotr Ufimtsev, a Soviet mathematician, published a seminal paper titled Method of Edge Waves in the Physical Theory of Diffraction in the journal of the Moscow Institute for Radio Engineering, in which he showed that the strength of the radar return from an object is related to its edge configuration, not its size.[5] Ufimtsev was extending theoretical work published by the German physicist Arnold Sommerfeld.[6][7][8] Ufimtsev demonstrated that he could calculate the radar cross-section across a wing's surface and along its edge. The obvious and logical conclusion was that even a large aircraft could reduce its radar signature by exploiting this principle. However, the resulting design would make the aircraft aerodynamically unstable, and the state of computer technology in the early 1960s could not provide the kinds of flight computers which would later allow aircraft such as the F-117 and B-2 Spirit to stay airborne. By the 1970s, when Lockheed analyst Denys Overholser found Ufimtsev's paper, computers and software had advanced significantly, and the stage was set for the development of a stealth airplane.[9]

The F-117 was born after the Vietnam War, where increasingly sophisticated Soviet surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) had downed heavy bombers.[10] The heavy losses inflicted by Soviet-made SAMs upon the Israeli air force in the 1973 Yom Kippur war also contributed to a 1974 Defense Science Board assessment that in case of a conflict in Central Europe, air defenses would likely prevent NATO air strikes on targets in Eastern Europe.[11]

It was a black project, an ultra-secret program for much of its life; very few people in the Pentagon knew the program even existed.[12][13] The project began in 1975 with a model called the "Hopeless Diamond"[14][15] (a wordplay on the Hope Diamond because of its appearance). The following year, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) issued Lockheed Skunk Works a contract to build and test two Stealth Strike Fighters, under the code name "Have Blue".[16] These subscale aircraft incorporated jet engines of the Northrop T-38A, fly-by-wire systems of the F-16, landing gear of the A-10, and environmental systems of the C-130.[16] By bringing together existing technology and components, Lockheed built two demonstrators under budget, at $35 million for both aircraft, and in record time.[16]

The maiden flight of the demonstrators occurred on 1 December 1977.[17] Although both aircraft crashed during the demonstration program, test data proved positive. The success of Have Blue led the government to increase funding for stealth technology. Much of that increase was allocated towards the production of an operational stealth aircraft, the Lockheed F-117A, under the program code name "Senior Trend".[18][19]

Senior Trend

The decision to produce the F-117A was made on 1 November 1978, and a contract was awarded to Lockheed Advanced Development Projects, popularly known as the Skunk Works, in Burbank, California.[20] The program was led by Ben Rich, with Alan Brown as manager of the project.[21] Rich called on Bill Schroeder, a Lockheed mathematician, and Overholser, a computer scientist, to exploit Ufimtsev's work. The three designed a computer program called "Echo", which made it possible to design an airplane with flat panels, called facets, which were arranged so as to scatter over 99% of a radar's signal energy "painting" the aircraft.[9][22][10]

The first YF-117A, serial number 79-10780, made its maiden flight from Groom Lake ("Area 51"), Nevada, on 18 June 1981,[23] only 31 months after the full-scale development decision. The first production F-117A was delivered in 1982, and operational capability was achieved in October 1983.[6][24] The 4450th Tactical Group stationed at Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada, were tasked with the operational development of the early F-117, and between 1981 (prior to the arrival of the first models) and 1989 they used LTV A-7 Corsair IIs for training, to bring all pilots to a common flight training baseline and later as chase planes for F-117A tests.[25]

The F-117 was secret for much of the 1980s. Many news articles discussed what they called a "F-19" stealth fighter, and the Testor Corporation produced a very inaccurate scale model. When an F-117 crashed in Sequoia National Forest in July 1986, killing the pilot and starting a fire, the Air Force established restricted airspace. Armed guards prohibited entry, including firefighters, and a helicopter gunship circled the site. All F-117 debris was replaced with remains of a F-101A Voodoo crash stored at Area 51. When another fatal crash in October 1987 occurred inside Nellis, the military again provided little information to the press.[26]

The Air Force denied the existence of the aircraft until 10 November 1988, when Assistant Secretary of Defense J. Daniel Howard displayed a grainy photograph at a Pentagon press conference, disproving the many inaccurate rumors about the shape of the "F-19". After the announcement pilots could fly the F-117 during daytime and no longer needed to be associated with the A-7, flying the T-38 supersonic trainer for travel and training instead.[27] In April 1990, two F-117 aircraft were flown into Nellis, arriving during daylight and publicly displayed to a crowd of tens of thousands.[28]

Five Full Scale Development (FSD) aircraft were built, designated "YF-117A".[29] The last of 59 production F-117s were delivered on 3 July 1990.[24][30]

As the Air Force has stated, "Streamlined management by Aeronautical Systems Center, Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio, combined breakthrough stealth technology with concurrent development and production to rapidly field the aircraft ... The F-117A program demonstrates that a stealth aircraft can be designed for reliability and maintainability."[2]

Designation

The operational aircraft was officially designated "F-117A".[31] Most modern U.S. military aircraft use post-1962 designations in which the designation "F" is usually an air-to-air fighter, "B" is usually a bomber, "A" is usually a ground-attack aircraft, etc. (Examples include the F-15, the B-2 and the A-6.) The F-117 is primarily an attack aircraft,[1] so its "F" designation is inconsistent with the DoD system. This is an inconsistency that has been repeatedly employed by the U.S. Air Force with several of its attack aircraft since the late 1950s, including the Republic F-105 Thunderchief and General Dynamics F-111 Aardvark. A televised documentary quoted project manager Alan Brown as saying that Robert J. Dixon, a four-star Air Force general who was the head of Tactical Air Command felt that the top-notch USAF fighter pilots required to fly the new aircraft were more easily attracted to an aircraft with an "F" designation for fighter, as opposed to a bomber ("B") or attack ("A") designation.[32][33]

The designation "F-117" seems to indicate that it was given an official designation prior to the 1962 U.S. Tri-Service Aircraft Designation System and could be considered numerically to be a part of the earlier "Century series" of fighters. The assumption prior to the revealing of the aircraft to the public was that it would likely receive the F-19 designation as that number had not been used. However, there were no other aircraft to receive a "100" series number following the F-111. Soviet fighters obtained by the U.S. via various means under the Constant Peg program[34] were given F-series numbers for their evaluation by U.S. pilots, and with the advent of the Teen Series fighters, most often Century Series designations.[35]

As with other exotic military aircraft types flying in the southern Nevada area, such as captured fighters, an arbitrary radio call of "117" was assigned. This same radio call had been used by the enigmatic 4477th Test and Evaluation Squadron, also known as the "Red Hats" or "Red Eagles", that often had flown expatriated MiG jet fighters in the area, but there was no relationship to the call and the formal F-19 designation then being considered by the Air Force. Apparently, use of the "117" radio call became commonplace and when Lockheed released its first flight manual (i.e., the Air Force "dash one" manual for the aircraft), F-117A was the designation printed on the cover.[36]

Design

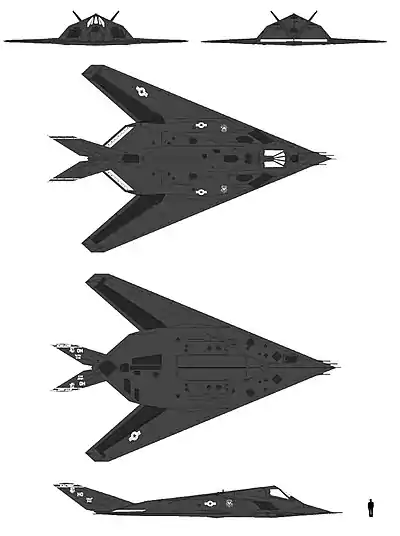

When the Air Force first approached Lockheed with the stealth concept, Skunk Works Director Kelly Johnson proposed a rounded design. He believed smoothly blended shapes offered the best combination of speed and stealth. However, his assistant, Ben Rich, showed that faceted-angle surfaces would provide a significant reduction in radar signature, and the necessary aerodynamic control could be provided with computer units. A May 1975 Skunk Works report, "Progress Report No. 2, High Stealth Conceptual Studies", showed the rounded concept that was rejected in favor of the flat-sided approach.[37] The resulting unusual design surprised and puzzled experienced pilots. A Royal Air Force (RAF) pilot who flew it as an exchange officer stated that when he first saw a photograph of the still-secret F-117, he "promptly giggled and thought [to himself] 'this clearly can't fly'".[38] Early stealth aircraft were designed with a focus on minimal radar cross-section (RCS) rather than aerodynamic performance. Highly stealthy aircraft like the F-117 Nighthawk are aerodynamically unstable in all three aircraft principal axes and require constant flight corrections from a fly-by-wire (FBW) flight system to maintain controlled flight.[39] It is shaped to deflect radar signals and is approximately the size of an F-15 Eagle.

The single-seat Nighthawk is powered by two non-afterburning General Electric F404 turbofan engines. It is air refuelable and features a V-tail. The maximum speed is 623 mph (1,003 km/h; 541 kn) at high altitude, the max rate of climb is 2,820 feet (860 m) per minute, and service ceiling is 43,000 to 45,000 feet (13,000 to 14,000 m).[40] The cockpit was quite spacious, with ergonomic displays and controls, but the field of view was somewhat obstructed with a large blind spot to the rear.[41]

Avionics

It has quadruple-redundant fly-by-wire flight controls. To lower development costs, the avionics, fly-by-wire systems, and other systems and parts were derived from the General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon, Boeing B-52 Stratofortress, McDonnell Douglas F/A-18 Hornet, and McDonnell Douglas F-15E Strike Eagle. The parts were originally described as spares in budgets for these aircraft, to keep the F-117 project secret.

The aircraft is equipped with sophisticated navigation and attack systems integrated into a digital avionics suite. It navigates primarily by GPS and high-accuracy inertial navigation. Missions are coordinated by an automated planning system that can automatically perform all aspects of an attack mission, including weapons release.[42] Targets are acquired by a thermal imaging infrared system, paired with a laser rangefinder/laser designator that finds the range and designates targets for laser-guided bombs. The F-117A's split internal bay can carry 5,000 pounds (2,300 kg) of ordnance. Typical weapons are a pair of GBU-10, GBU-12, or GBU-27 laser-guided bombs, two BLU-109 penetration bombs, or two Joint Direct Attack Munitions (JDAM) GPS/INS guided stand-off bombs. To maintain its low observability, the aircraft was not fitted with its own radar; not only would an active radar be detectable through its emissions, but an inactive radar would also act as a reflector of radar energy.[43]

Stealth

The F-117 has a radar cross-section of about 0.001 m2 (0.0108 sq ft).[44] Among the penalties for stealth are lower engine thrust due to losses in the inlet and outlet, a very low wing aspect ratio, and a high sweep angle (50°) needed to deflect incoming radar waves to the sides.[11] With these design considerations and no afterburner, the F-117 is limited to subsonic speeds.

The F-117A carries no radar, which lowers emissions and cross-section, and whether it carries any radar detection equipment remained classified as of 2008.[11] Its faceted shape (made from 2-dimensional flat surfaces) resulted from the limitations of the 1970s-era computer technology used to calculate its radar cross-section. Later supercomputers made it possible for subsequent aircraft like the B-2 bomber to use curved surfaces while maintaining stealth, through the use of far more computational resources to perform the additional calculations.[45]

The radar-absorbent flat sheets covering the F-117A weighed almost one ton, and were held in place by glue, with the gaps between the sheets filled with a kind of putty material called "butter".[11]

An exhaust plume contributes a significant infrared signature. The F-117 reduces IR signature with a non-circular tail pipe (a slit shape) to minimize the exhaust cross-section and maximize the mixing of hot exhaust with cool ambient air. The F-117 lacks afterburners, because the hot exhaust would increase the infrared signature, and breaking the sound barrier would produce an obvious sonic boom, as well as surface heating of the aircraft skin which also increases the infrared footprint. As a result, its performance in air combat maneuvering required in a dogfight would never match that of a dedicated fighter aircraft. This was unimportant in the case of this aircraft since it was designed to be a bomber.

Passive (multistatic) radar, bistatic radar[46] and especially multistatic radar systems detect some stealth aircraft better than conventional monostatic radars, since first-generation stealth technology (such as the F-117) reflects energy away from the transmitter's line of sight, effectively increasing the radar cross section (RCS) in other directions, which the passive radars monitor.

Operational history

During the program's early years, from 1984 to mid-1992, the F-117A fleet was based at Tonopah Test Range Airport, Nevada, where it served under the 4450th Tactical Group. Because the F-117 was classified during this time, the unit was officially located at Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada, and equipped with A-7 Corsair II aircraft. All military personnel were permanently assigned to Nellis AFB, and most personnel and their families lived in Las Vegas. This required commercial air and trucking to transport personnel between Las Vegas and Tonopah each week. The 4450th was absorbed by the 37th Tactical Fighter Wing in 1989. In 1992, the entire fleet was transferred to Holloman Air Force Base, New Mexico, under the command of the 49th Fighter Wing. This move also eliminated the Key Air and American Trans Air contract flights to Tonopah, which flew 22,000 passenger trips on 300 flights from Nellis to Tonopah per month.

The F-117 reached initial operating capability status in 1983.[2] The Nighthawk's pilots called themselves "Bandits". Each of the 558 Air Force pilots who have flown the F-117 has a Bandit number, such as "Bandit 52", that indicates the sequential order of their first flight in the F-117.[47] Pilots told friends and families that they flew the Northrop F-5 in aggressor squadrons against Tactical Air Command.[26]

The F-117 has been used several times in war. Its first mission was during the United States invasion of Panama in 1989.[48] During that invasion two F-117A Nighthawks dropped two bombs on Rio Hato airfield.

During the Gulf War in 1991, the F-117 flew approximately 1,300 sorties and scored direct hits on what the U.S. called 1,600 high-value targets in Iraq[2] over 6,905 flight hours.[49] Leaflet drops on Iraqi forces displayed the F-117 destroying ground targets and warned "Escape now and save yourselves".[27] Only 229 Coalition tactical aircraft could drop and designate laser-guided bombs of which 36 F-117s represented 15.7%, and only the USAF had the I-2000 bombs intended for hardened targets. So the F-117 represented 32% of all coalition aircraft that could deliver such bombs.[50]: 73–74 Notably, F-117s were used in the Amiriyah shelter bombing.[51]

Initial claims of the F-117's effectiveness were later found to be overstated.[52] Initial reports of F-117s hitting 80% of their targets were later scaled back to "41–60%".[50]: 132 On the first night, they failed to hit 40% of their assigned air-defense targets, including the Air Defense Operations Center in Baghdad, and 8 such targets remained functional out of 10 that could be assessed.[50]: 136–137 In their Desert Storm white paper, the USAF stated that "the F-117 was the only airplane that the planners dared risk over downtown Baghdad" and that this area was particularly well defended. (Dozens of F-16s were routinely tasked to attack Baghdad in the first few days of the war.)[50]: 137–138 In fact, most of the air defenses were on the outskirts of the city and many other aircraft hit targets in the downtown area, with minimal casualties when they attacked at night like the F-117.[50] This meant they avoided the optically aimed anti-aircraft cannon and infrared SAMs which were the biggest threat to Coalition aircraft.[50]: 105

The aircraft was operated in secret from Tonopah for almost a decade, but after the Gulf War the aircraft moved to Holloman in 1992—however, its integration with the USAF's non-stealth "iron jets" occurred slowly. As one senior F-117A pilot later said: Because of ongoing secrecy others continued to see the aircraft as "none of their business, a stand-alone system".[11] The F-117A and the men and women of the 49th Fighter Wing were deployed to Southwest Asia on multiple occasions. On their first deployment, with the aid of aerial refueling, pilots flew non-stop from Holloman to Kuwait, a flight of approximately 18.5 hours.[53]

Combat over Yugoslavia

.jpg.webp)

One F-117 (AF ser. no. 82-0806) was lost to enemy action. It was downed during an Operation Allied Force mission against the Army of Yugoslavia on 27 March 1999.[54] The aircraft was acquired by a fire control radar at a distance of 8.1 mi (13 km) and an altitude of 5.0 mi (8 km). SA-3s were then launched by a Yugoslav version of the Soviet Isayev S-125 "Neva" (NATO name SA-3 "Goa") anti-aircraft missile system.[54][55][56] The launcher was run by the 3rd Battalion of the 250th Air Defence Missile Brigade under the command of Colonel Zoltán Dani.[57]

After the explosion, the aircraft became uncontrollable, forcing the pilot to eject.[54] The pilot was recovered six hours later by a United States Air Force Pararescue team.[54][58] The stealth technology from the downed F-117 may have been acquired by Russia and China,[59] but the United States did not attempt to destroy the wreckage because senior Pentagon officials argued that its technology was already dated and no longer important to protect.[26]

American sources state that a second F-117 was targeted and damaged during the campaign, allegedly on 30 April 1999.[60][61] The aircraft returned to Spangdahlem base,[61] but it supposedly never flew again.[62][63] However, the USAF continued to use the F-117 during Allied Force.[64]

Later service and retirement

The F-117 was later used in the Operation Enduring Freedom in 2001 and Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003. It was only operated by the U.S. Air Force.

The loss in Serbia caused the USAF to create a subsection of their existing weapons school to improve tactics. More training was done with other units, and the F-117A began to participate in Red Flag exercises. Though advanced for its time, the F-117's stealthy faceted airframe required a large amount of maintenance and was eventually superseded by streamlined shapes produced with computer-aided design. Other weapon systems began to take on the F-117's roles, such as the F-22 Raptor gaining the ability to drop guided bombs.[65] By 2005, the aircraft was used only for certain missions, such as if a pilot needed to verify that the correct target had been hit, or when minimal collateral damage was vital.[11]

The USAF had once planned to retire the F-117 in 2011, but Program Budget Decision 720 (PBD 720), dated 28 December 2005, proposed retiring it by October 2008 to free up an estimated $1.07 billion[66] to buy more F-22s.[47] PBD 720 called for 10 F-117s to be retired in FY2007 and the remaining 42 in FY2008, stating that other USAF planes and missiles could stealthily deliver precision ordnance, including the B-2 Spirit, F-22 and JASSM.[67] The planned introduction of the multi-role F-35 Lightning II also contributed to the retirement decision.[68]

In late 2006, the USAF closed the F-117 formal training unit (FTU),[69] and announced the retirement of the F-117.[70] The first six aircraft to be retired took their last flight on 12 March 2007 after a ceremony at Holloman AFB to commemorate the aircraft's career. Brigadier General David L. Goldfein, commander of the 49th Fighter Wing, said at the ceremony, "With the launch of these great aircraft today, the circle comes to a close—their service to our nation's defense fulfilled, their mission accomplished and a job well done. We send them today to their final resting place—a home they are intimately familiar with—their first, and only, home outside of Holloman."[71]

Unlike most other USAF aircraft that are retired to Davis-Monthan AFB for scrapping, or dispersal to museums, most of the F-117s were placed in "Type 1000" storage[72] in their original hangars at the Tonopah Test Range Airport.[54] At Tonopah, their wings were removed and the aircraft are stored in their original climate-controlled hangars.[71] The decommissioning occurred in eight phases, with the operational aircraft retired to Tonopah in seven waves from 13 March 2007 until the last wave's arrival on 22 April 2008.[3][54] Four aircraft were kept flying beyond April by the 410th Flight Test Squadron at Palmdale for flight test. By August, two were remaining. The last F-117 (AF Serial No. 86-0831) left Palmdale to fly to Tonopah on 11 August 2008.[54][73] With the last aircraft retired, the 410th was inactivated in a ceremony on 1 August 2008.[74]

Five aircraft were placed in museums, including the first four YF-117As and some remains of the F-117 shot down over Serbia. Through 2009, one F-117 had been scrapped; AF Serial No. 79-0784 was scrapped at the Palmdale test facility on 26 April 2008. It was the last F-117 at Palmdale and was scrapped to test an effective method for destroying F-117 airframes.[54]

Congress had ordered that all F-117s mothballed from 30 September 2006 onwards were to be maintained "in a condition that would allow recall of that aircraft to future service" as part of the 2007 National Defense Authorization Act. By April 2016, lawmakers appeared ready to "remove the requirement that certain F-117 aircraft be maintained in a condition that would allow recall of those aircraft to future service", which would move them from storage to the aerospace maintenance and regeneration yard in Arizona to be scavenged for hard-to-find parts, or completely disassembled.[75] On 11 September 2017, it was reported that in accordance with the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2017, signed into law on 23 December 2016, "the Air Force will remove four F-117s every year to fully divest them—a process known as demilitarizing aircraft".[76]

Post-retirement sightings

Although officially retired, the F-117 fleet remained intact as of 2009, with photos showing the aircraft carefully mothballed.[54] As of 2016, the retired fleet comprised over 50 airframes, with some of the aircraft being flown periodically.[77] F-117s were spotted flying periodically from 2014 to 2019.[78][79][80][81][82] In March 2019, it was reported that four F-117s had been secretly deployed to the Middle East in 2016 and that one had to make an emergency landing at Ali Al Salem (OKAS), Kuwait sometime late that year.[83]

In February 2019, an F-117 was observed flying through the R-2508 Special Use Airspace Complex in the vicinity of Edwards Air Force Base, escorted by two F-16 Fighting Falcons that may have been providing top cover. Closer photographs of the aircraft revealed that the tail code had been scrubbed in an attempt to remove the paint. The partially-intact code identified it as a former aircraft of the 49th Operations Group.[81] An F-117 was also photographed in 2019 carrying unit markings previously unassociated with the aircraft—a band on the tail bearing the name Dark Knights, suggesting either an official or unofficial squadron is maintaining the Nighthawks.[84] In July 2019, one Nighthawk in a hybrid aggressor paint scheme was spotted flying above Death Valley, trailing behind a KC-135R Stratotanker.[85]

In March 2020, a spectator recorded an F-117 flying through the "Star Wars Canyon" in Death Valley, California.[4] On 20 May 2020, two more F-117s were sighted in a common aerial refueling area of Southern California trailing a NKC-135R Stratotanker from Edwards AFB, California.[82] In October 2020, at least two F-117s arrived at MCAS Miramar, featuring a tail code of TR which the Nighthawks based at Tonopah Range had previously used.[86][87]

On 13 September 2021, a pair of F-117s landed at Fresno Yosemite International Airport in California. They were scheduled to train with the California Air National Guard F-15C/D Eagles of the 144th Fighter Wing over the next few days.[88] One aircraft had red letters on its tail, and the other had white letters. One of the two was observed to not be fitted with radar reflectors.[89]

In January 2022, two F-117s were observed in flight in the Saline Military Operating Area. One had portions of its exterior covered in a "mirror-like coating" believed to be an experimental treatment to reduce the aircraft's infrared signature.[90]

Variants

F-117N "Seahawk"

The United States Navy tested the F-117 in 1984 but determined it was unsuitable for carrier use.[27] In the early 1990s, Lockheed proposed an upgraded carrier-capable F-117 variant dubbed the "Seahawk" to the Navy as an alternative to the canceled A/F-X program. The unsolicited proposal was received poorly by the Department of Defense, which lacked interest in the single mission capabilities on offer, particularly as it would take money away from the Joint Advanced Strike Technology program, which evolved into the Joint Strike Fighter. The F-117N would have differed from the land-based F-117 in several ways, such as the use of "elevators, a bubble canopy, a less sharply swept wing and reconfigured tail".[91][92] It would also be re-engined with General Electric F414 turbofans in place of the General Electric F404s. The aircraft would be optionally fitted with hardpoints, allowing for an additional 8,000 lb (3,600 kg) of payload, and a new ground-attack radar with air-to-air capability. In that role, the F-117N could carry AIM-120 AMRAAM air-to-air missiles.[91][93]

F-117B

After being rebuffed by the Navy, Lockheed submitted an updated proposal that included afterburning capability and a larger emphasis on the F-117N as a multi-mission aircraft, rather than just an attack aircraft.[93] To boost interest, Lockheed also proposed an F-117B land-based variant that shared most of the F-117N capabilities. This variant was proposed to the USAF and RAF.[94] Two RAF pilots formally evaluated the aircraft in 1986 as a reward for British help with the American bombing of Libya that year, RAF exchange officers began flying the F-117 in 1987,[27] and the British declined an offer during the Reagan administration to purchase the aircraft.[95] This renewed F-117N proposal was also known as the A/F-117X.[96] Neither the F-117N nor the F-117B were ordered.

Operators

- United States

- United States Air Force[97]

- 4450th Tactical Group – Tonopah Test Range, Nevada

- 4450th Tactical Squadron (1981–1989)

- 4451st Tactical Squadron (1981–1989)

- 4453rd Test and Evaluation Squadron (1985–1989)

- 37th Tactical Fighter Wing/Fighter Wing – Tonopah Test Range

- 415th Tactical Fighter Squadron (1989–1992)

- 416th Tactical Fighter Squadron (1989–1992)

- 417th Tactical Fighter Training Squadron (1989–1992)

- 49th Fighter Wing – Holloman AFB, New Mexico

- 7th Fighter Squadron (1992–2006)

- 8th Fighter Squadron (1992–2008)

- 9th Fighter Squadron (1993–2008)

- 412th Test Wing – Edwards AFB, California

- 410th Flight Test Squadron (1993–2008)

- 4450th Tactical Group – Tonopah Test Range, Nevada

Aircraft on display

United States

- YF-117A

- 79-10780 Scorpion 1 – on pedestal display on Nellis Boulevard, at the entrance to Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada (36°13′38.00″N 115°3′33.28″W). It was put in place on 16 May 1992, the first F-117 to be made a gate guardian.[98]

- 79-10781 Scorpion 2 – National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base outside Dayton, Ohio. It was delivered to the museum on 17 July 1991.[99]

- 79-10782 Scorpion 3 – Holloman Air Force Base, New Mexico. It was repainted to resemble the first F-117A used to drop weapons in combat. This aircraft was used for acoustics and navigation system testing. While wearing a flag painted on its bottom surface, this aircraft revealed the type's existence to high-ranking officials at Groom Lake on 14 December 1983, the first semi-public unveiling of the aircraft. It was placed on display at Holloman AFB on 5 April 2008.

- 79-10783 Scorpion 4 – It had been previously on display at the Blackbird Airpark Museum at Air Force Plant 42, Palmdale, California. In June 2012, Scorpion 4 was transported from Blackbird Airpark to Edwards AFB for restoration work; it is planned for the aircraft to be displayed at the Air Force Flight Test Center Museum.[100]

- F-117A

- 80-0785 – Pole-mounted outside the Skunk Works facility at United States Air Force Plant 42 in Palmdale, California. Hybrid airframe comprising the wreckage of 80–0785, the first production F-117A, and static test articles 778 and 779.[101]

- 82-0799 Midnight Rider – Hill Aerospace Museum; Aircraft arrived at the museum on 5 August 2020; it is to be prepared and painted for display.[102]

- 82-0803 Unexpected Guest – Displayed outside the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in Simi Valley, California.[103]

- 85-0813 The Toxic Avenger – Delivered to Castle Air Museum in Atwater, California on 29 July 2022 for restoration and then display. Restoration is expected to take about a year and cost around $75,000.[104]

- 85-0817 Shaba[105] – Arrived at the Kalamazoo Air Zoo on 11 December 2020 to be partially restored and put on display.

- 85-0819 Raven Beauty – Scheduled to be transported to the Stafford Air & Space Museum in early 2020 for preservation.

- 84-0827 – Stripped fuselage listed as "scrap" on a government surplus website in early 2020. Fate unknown.[106]

- 85-0831 – Located at the Strategic Air Command & Aerospace Museum in Ashland, Nebraska, where it is scheduled for restoration and display. It served as a test aircraft at Air Force Plant 42 in Palmdale, California from 1987 to 2008.[107]

- 85-0833 Black Devil – Unveiled at Palm Springs Air Museum on 3 October 2020. Under restoration and scheduled for public display in Spring 2021.[108]

Serbia

- F-117A

- 82-0806 Something Wicked – shot down over Serbia; the remains are displayed at the Museum of Aviation in Belgrade close to Belgrade Nikola Tesla Airport.[109]

Nicknames

The aircraft's official name is "Night Hawk",[110] however the alternative form "Nighthawk" is frequently used.

As it prioritized stealth over aerodynamics, it earned the nickname "Wobblin' Goblin" due to its alleged instability at low speeds. However, F-117 pilots have stated the nickname is undeserved.[111] "Wobblin' (or Wobbly) Goblin" is likely a holdover from the early Have Blue / Senior Trend (FSD) days of the project when instability was a problem. In the USAF, "Goblin" (without wobbly) persists as a nickname because of the aircraft's appearance. During Operation Desert Storm, Saudis dubbed the aircraft "Shaba", which is Arabic for "Ghost".[112] Some pilots also called the airplane the "Stinkbug".[113]

During the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia in 1999 it picked up the nickname "Invisible" (Serbian cyrillic "Невидљиви", latin "Nevidljivi") and it gained popularity after it was shot down over Serbian airspace near Buđanovci. The F-117 downing became a spot of Serbian pride with a phrase "We didn't know it was invisible" was coined.

Specifications (F-117A)

Data from U.S. Air Force National Museum, for the F-117A.[2]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 65 ft 11 in (20.09 m)

- Wingspan: 43 ft 4 in (13.21 m)

- Height: 12 ft 5 in (3.78 m)

- Wing area: 780 sq ft (72 m2) [114]

- Airfoil: Lozenge section, 3 flats Upper, 2 flats Lower[115]

- Empty weight: 29,500 lb (13,381 kg) [114]

- Max takeoff weight: 52,500 lb (23,814 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × General Electric F404-F1D2 turbofan engines, 9,040 lbf (40.2 kN) thrust each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 594 kn (684 mph, 1,100 km/h)

- Maximum speed: Mach 0.92

- Range: 930 nmi (1,070 mi, 1,720 km) ;

- Service ceiling: 45,000 ft (14,000 m)

- Wing loading: 67.3 lb/sq ft (329 kg/m2) calculated from[114]

- Thrust/weight: 0.40

Armament

- 2 × internal weapons bays with one hardpoint each (total of two weapons) equipped to carry:

- Bombs:

- GBU-10 Paveway II laser-guided bomb with 2,000 lb (910 kg) Mk84 blast/fragmentation or BLU-109 or BLU-116 Penetrator warhead

- GBU-12 Paveway II laser-guided bomb with 500 lb (230 kg) Mk82 blast/fragmentation warhead

- GBU-27 Paveway III laser-guided bomb with 2,000 lb (910 kg) Mk84 blast-fragmentation or BLU-109 or BLU-116 Penetrator warhead

- GBU-31 JDAM INS/GPS guided munition with 2,000 lb (910 kg) Mk84 blast-frag or BLU-109 Penetrator warhead

- B61 nuclear bomb[116]

- Bombs:

Notable appearances in media

The Omaha Nighthawks professional American football team used the F-117 Nighthawk as its logo.[117]

See also

- Sea Shadow

- Wainfan Facetmobile

Related development

- Lockheed Have Blue

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- BAE Replica

- MBB Lampyridae

Related lists

- List of Lockheed aircraft

- List of military aircraft of the United States

References

Notes

- Eden 2004, p. 240.

- Lockheed F-117A Nighthawk. National Museum of the United States Air Force. Retrieved 16 October 2016

- Pae, Peter. "Stealth fighters fly off the radar". Los Angeles Times, 23 April 2008. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- "A Rare F-117A Stealth Fighter Flies Over 'Star Wars Canyon'". Popular Mechanics, 19 March 2020

- Ufimtsev, P.Ya. "Method of Edge Waves in the Physical Theory of Diffraction". oai.dtic.mil. Retrieved 12 June 2010

- Day, Dwayne A. "Stealth Technology". Archived 18 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine Centennial of Flight, 2003. Retrieved 13 November 2010

- UCI Ufimtsev, Pyotr Ya. "Method of Edge Waves in the Physical Theory of Diffraction". Journal of the Moscow Institute for Radio Engineering, 1964

- Ireton, Major Colin T. "Filling the Stealth Gap". Air and Space Power Journal, Fall 2006

- Bartholomew Hott; George E. Pollock, "The Advent, Evolution, and New Horizons of United States Stealth Aircraft", ics.purdue.edu, archived from the original on 16 February 2003, retrieved 12 June 2010

- "F-117A Nighthawk". Air-Attack.com. Archived from the original on 28 February 2010. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- Sweetman, Bill (January 2008). "Unconventional Weapon". Air & Space Magazine. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- Cunningham, Jim (Fall 1991). "Cracks in the Black Dike, Secrecy, the Media and the F-117A". Air & Space Power Journal. United States Air Force. Archived from the original on 6 March 2008. Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- "Top Gun – the F-117 Stealth Fighter". BBC. Retrieved 10 May 2011

- Rich 1994, pp. 26–27

- "F-117 History" Archived 27 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine. F-117 Stealth Fighter Association. Retrieved 20 January 2007

- Goodall 1992, p. 19

- Eden 2004, pp. 242–243

- Goodall 1992, p. 24.

- F-117A "Senior Trend". f-117a.com. Retrieved 12 June 2010

- Rich 1994, p. 71

- "YouTube". Archived from the original on 13 March 2014 – via YouTube.

- "The Secrets of Stealth". Archived 3 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine Discovery Military Channel

- Goodall 1992, p. 27

- Goodall 1992, p. 29

- Holder, Bill; Wallace, Mike (2000). Lockheed F-117 Nighthawk: An Illustrated History of the Stealth Fighter. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7643-0067-7.

- Jeffrey T. Richelson (July 2001). "When Secrets Crash". Air Force Magazine. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- Crickmore, Paul (2003). Combat Legend: F-117 Nighthawk. Airlife. pp. 33, 48–49, 60. ISBN 1-84037-394-6.

- Gregos, J. "First Public Display of the F-117 at Nellis AFB April 21, 1990". dreamlandresort.com. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- "DOD 4120.15-L – Addendum". United States Department of Defense, December 2007. Retrieved 12 June 2010

- Donald 2003, p. 98

- DOD 4120.15-L: Model Designation of Military Aerospace Vehicles. (PDF), United States Department of Defense, 12 May 2004, p. 38, archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2004, retrieved 17 July 2017

- "Stealth and Beyond: Air Stealth (TV-series)". Archived 11 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine The History Channel, 2006. Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- Moderns (13 April 2017). "Modern Marvels S11E62 F117". Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2018 – via YouTube.

- Grier. Peter. "Constant Peg". airforce-magazine.com, Vol. 90, no. 4, April 2007. Retrieved 10 May 2011

- Peter W. Merlin (2011). Images of Aviation: Area 51. Boston: Arcadia Publishing. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-7385-7620-6.

- Miller 1990

- Slattery, Chad. "Secrets of the Skunk Works – 'Little Harvey, Concept B'". Air & Space/Smithsonian.

- Crickmore, Paul and Alison J. (2003) [1999]. Nighthawk F-117 Stealth Fighter. Zenith Imprint. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-1-61060-737-7.

- Rich and Janos, Skunk Works, pp. 30–31, 46.

- Dorr, Robert F. (2016). Air Combat: A History of Fighter Pilots. Berkley. p. 315. ISBN 978-0-425-21170-0

- Nijboer, Donald (2016). Fighting Cockpits: In the Pilot's Seat of Great Military Aircraft from World War I to Today, p. 210. Zenith Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-4956-4.

- "F-117A Nighthawk" Federation of American Scientists

- Holloway, Don (March 1996). "Stealth Secrets of the F-117 Nighthawk". Historynet.com. HistoryNet. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- Richardson 2001, p. 57

- Rich 1994, p. 21

- "Bistatic Radar Sets". Radartutorial.eu. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- Topolsky, Joshua. "Air Force's stealth fighters making final flights". CNN, 11 March 2008. Retrieved 11 March 2009

- Crocker, H.W. III (2006). Don't Tread on Me. New York: Crown Forum. ISBN 978-1-4000-5363-6.

- "Weapons: F-117A Stealth". PBS Frontline. Retrieved 12 June 2010

- "Operation Desert Storm Evaluation of the Air Campaign GAO/NSIAD-97-134" (PDF). General Accounting Office. 12 June 1997. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- Clark, Ramsey (1992). The Fire This Time: U.S. War Crimes in the Gulf. New York, NY: Thunder's Mouth Press. p. 70. ISBN 1-56025-047-X. OCLC 26097107.

- Schmitt, Eric. "Navy Looks On with Envy at Air Force Stealth Display". The New York Times, 17 June 1991. Retrieved 24 April 2010

- Petrescu, Florian Ion (2013). Lockheed Martin Color Germany. Petrescu, Relly Victoria. Norderstedt. p. 55. ISBN 978-3-8482-3073-0. OCLC 863964531.

- Logan, Don (2009). Lockheed F-117 Nighthawks: A Stealth Fighter Roll Call. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7643-3242-5.

- "How to Take Down an F-117". Strategy Page, 21 November 2005. Retrieved 12 June 2010

- "Serb discusses 1999 downing of stealth". USA Today, 26 October 2005. Retrieved 1 July 2009

- Dsouza, Larkins. "Who shot down F-117?" Defence Aviation, 8 February 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2011

- Whitcomb, Darrel. "The Night They Saved Vega 31". airforcemag.com. Air Force Association. Archived from the original on 22 April 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- Stojanovic, Dusan (23 January 2011). "China's new stealth fighter may use U.S. technology". China Digital Times.

- "Damage said attributed to full moon". Nl.newsbank.com, 6 May 1999. Retrieved 19 February 2012

- "Yes, Serbian Air Defenses Did Hit Another F-117 During Operation Allied Force In 1999". The Drive. 1 December 2020.

- Riccioni, Col. Everest E. "Description of our Failing Defence Acquisition System". Project on government oversight, 8 March 2005. Quote: "This event, which occurred during the Kosovo conflict on 27 March, was a major blow to the US Air Force. The aircraft was special: an F-117 Nighthawk stealth bomber that should have been all but invisible to the Serbian air defences. And this certainly wasn't a fluke—a few nights later, Serb missiles damaged a second F-117."

- Nixon, Mark. "Gallant Knights, MiG-29 in Action during Allied Force". AirForces Monthly magazine, January 2002

- Donald 2003, p. 119

- Miller, Jay (2005). Lockheed Martin F/A-22 Raptor, Stealth Fighter, p. 44. Aerofax. ISBN 1-85780-158-X

- Tiron, Roxana. "New Mexico Air Force base at crossroads". Archived 1 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine The Hill, 22 February 2006. Retrieved 11 March 2009

- "Program Budget Decision 720". Department of Defense

- Shea, Christopher. "Now you see it..." Boston Globe, 4 February 2007. Retrieved 11 March 2009

- "F-117 pilot school closes". Air Force Times. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 20 January 2007.

- Bates, Staff Sergeant Matthew. "F-117: A long, storied history that is about to end". US Air Force, 28 October 2006

- Barrier, Terri. "F-117A retirement bittersweet occasion". Aerotech News and Review, 16 March 2007

- According to a statement by the United States Air Force, "Aircraft in Type-1000 storage are to be maintained until recalled to active service, should the need arise. Type 1000 aircraft are termed inviolate, meaning they have a high potential to return to flying status and no parts may be removed from them. These aircraft are 're-preserved' every four years."

- Radecki, Alan. "F-117's final formation fling". Flight International, 8 August 2008. Retrieved 11 March 2009

- "410th FLTS 'Baja Scorpions' closes historic chapter". Archived 3 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Air Force, Edwards AFB, 5 August 2008

- "Congress appears ready to let the Lockheed F-117A Nighthawk go". FlightGlobal, 27 April 2016.

- Pawlyk, Oriana (11 September 2017). "Retired but Still Flying". Defensetech.org. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- Hlad, Jennifer (6 May 2016). "A Real Retirement for the Nighthawk". Air Force Magazine. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- "Why Is The 'Retired' F-117 Nighthawk Still Flying?". Foxtrotalpha.jalopnik.com. 16 March 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- Axe, David. "Yep, F-117 Stealth Fighters Are Still Flying in 2015". War Is Boring. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- "F-117 Flying 2013" 1 May 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2013

- "F-117 Nighthawk – still out there, still flying (clearest photos yet)". Combat Aircraft. 2019. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- Rogoway, Tyler. "F-117 Stealth Jets Flew Directly Over Los Angeles on Another Mission Off The California Coast". The Drive. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- Leone, Dario (11 April 2019). ""One of the F-117s secretly deployed to the middle East to take part in OIR made emergency landing in Kuwait", Scramble Magazine Says". The Aviation Geek Club. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- "'Dark Knights' – a new F-117 squadron?". Air Forces Monthly. 18 March 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- "Agressor F117? Incredible new images revealed". Combat Aircraft. 14 July 2019. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- Rogoway, Tyler (20 October 2020). "F-117s Make Surprise Visit To Marine Corps Air Station Miramar". The Drive. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- Rogoway, Tyler (22 October 2020). "Check Out These Close-Up Shots of F-117s Deployed To Miramar". The Drive. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- "Behold F-117s on Their Historic Deployment to Fresno in These Stunning Shots".

- Rogoway, Tyler (13 September 2021). "F-117s Make Surprise Appearance At Fresno Airport To Train Against Local F-15s". The Drive. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- Rogoway, Tyler. "F-35 And F-117 Spotted Flying With Mysterious Mirror-Like Skin". The Drive. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- "Navy still not interested in F-117N; JAST plan due tomorrow". Aerospace Daily, Vol. 167, No. 52, 1993, p. 426

- "Variant Aircraft". f-117a.com, 14 July 2003. Retrieved 7 November 2010

- Morocco, John D. "Lockheed Returns to Navy with new F-117N Design". Aviation Week & Space Technology, Vol. 140, No. 10, 1994, p. 26

- "Lockheed Martin targets RAF and USN for F-117". Flight International, 28 June 1995.

- Rogoway, Tyler (3 January 2017). "Reagan Invited Thatcher To Join The Top Secret F-117 Program". The Drive.

- "Skunk Works official touts A/F-117X as Navy stealth option". Aerospace Daily, Vol. 171, No. 56, 1994, p. 446

- "F-117 History". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved: 22 September 2010

- "Holloman Restores F-117 Nighthawk". Holloman Air Force Base. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- "F-117 Nighthawk/79-10781". National Museum of the USAF. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- "One of only four existing F-117s returns to Edwards". Archived 22 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine Edwards Air Force Base. 13 June 2012

- F-117A: The Black Jet. Retrieved 13 November 2020

- The Drive. Retrieved 10 August 2020

- . The Drive. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- . Merced Sun-Star. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- "Project: Get Shaba (817) Home". Kalamazoo Air Zoo. Retrieved 8 June 2020

- "Stripped F-117 Nighthawk Arrives At Hill Aerospace Museum Direct From Tonopah" The Drive. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- . Strategic Air Command & Aerospace Museum. Retrieved 18 June 2021

- The Aviationist. Retrieved 20 October 2020

- Daly, M. "Tape Reveals Stealth of Our Ukrainian Pal". Daily News. Retrieved 2 January 2008. Archived 4 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "DOD 4120.15-L: Model Designation of Military Aerospace Vehicles", p. 18. United States Department of Defense, 12 May 2004. Retrieved 20 January 2007

- Rhodes, Jeffrey P. "The Black Jet". Air Force Magazine, Air Force Association, Volume 73, Issue 7, July 1990. Retrieved 20 January 2007

- Gresham, John D. "Gulf War 20th: Emerging from the Shadows". defensemedianetwork.com, 21 January 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2011

- "F-117A: Frequently Asked Questions". Archived from the original on 8 March 2001.

- "F-117 Nighthawk Fast Facts" (PDF). Lockheed Martin. November 2019.

- Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- "F-117A Nighthawk" Archived 1 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 13 November 2010

- "Omaha Nighthawks official page". Archived 5 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine ufl-football.com. Retrieved 6 June 2010

Bibliography

- Donald, David, ed. (2003). Black Jets: The Development and Operation of America's Most Secret Warplanes. Norwalk, CT: AIRtime Publishing Inc. ISBN 978-1-880588-67-3.

- Eden, Paul, ed. (2004). The Encyclopedia of Modern Military Aircraft. London: Amber Books. ISBN 978-1-904687-84-9.

- Goodall, James C. (1992). "The Lockheed F-117A Stealth Fighter". America's Stealth Fighters and Bombers: B-2, F-117, YF-22 and YF-23. St. Paul, MN: Motorbooks International. ISBN 978-0-87938-609-2.

- Miller, Jay (1990). Lockheed F-117 Stealth Fighter. Arlington, TX: Aerofax Extra. ISBN 978-0-942548-48-8.

- Rich, Ben (1994). Skunk Works. New York: Back Bay Books. ISBN 978-0-316-74330-3.

- Richardson, Doug (2001). Stealth Warplanes. New York: Salamander Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7603-1051-9.

Further reading

- Aronstein, David C. and Albert C. Piccirillo (1997). HAVE BLUE and the F-117A. Reston, VA: AIAA. ISBN 978-1-56347-245-9.

- Fisk, Robert (2005). The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East. New York: Alfred Knopf. ISBN 978-1-84115-007-9.

- Grant, R.G. and John R. Dailey (2007). Flight: 100 Years of Aviation. Harlow, Essex: DK Adult. ISBN 978-0-7566-1902-2.

- Jenkins, Dennis R. and Tony R. Landis (2008). Experimental & Prototype U.S. Air Force Jet Fighters. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press. ISBN 978-1-58007-111-6.

- Sun, Andt (1990). F-117A Stealth Fighter. Hong Kong: Concord Publications Co. ISBN 978-962-361-017-9.

- Winchester, Jim, ed. (2004). "Lockheed F-117". Modern Military Aircraft (Aviation Factfile). Rochester, Kent, UK: Grange Books plc. ISBN 978-1-84013-640-1.

- The World's Great Stealth and Reconnaissance Aircraft. New York: Smithmark Publishing. 1991. ISBN 978-0-8317-9558-0.

External links

- Lockheed F-117A Nighthawk. National Museum of the United States Air Force

- The 49th Fighter Wing at Holloman Air Force Base

- F-117A.com – The "Black Jet" website (a comprehensive site)

- F-117 article and Stealth article on Centennial of Flight web site

- F-117A Nighthawk page on AirAttack.com

- F-117A Nighthawk page on FAS.org

- "Filling the Stealth Gap", in Air and Space Power Journal Fall 2006 Archived 28 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- The Advent, Evolution, and New Horizons of United States Stealth Aircraft

- "The Secrets of Stealth" on Discovery Military Channel

- Austrian Radar Plots on acig.org

- CNN – NATO air attack shifts, aims at violence inside Kosovo – 27 March 1999

- Google Maps directory of all surviving F-117s on public display

- (in German) Austrian article about interception of F-117

- Russians admit testing F-117 lost in Yugoslavia, 2001 Flight Global article