Feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, and cultural customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structuring society around relationships that were derived from the holding of land in exchange for service or labour. Although it is derived from the Latin word feodum or feudum (fief),[1] which was used during the Medieval period, the term feudalism and the system which it describes were not conceived of as a formal political system by the people who lived during the Middle Ages.[2] The classic definition, by François Louis Ganshof (1944),[3] describes a set of reciprocal legal and military obligations which existed among the warrior nobility and revolved around the three key concepts of lords, vassals, and fiefs.[3]

A broader definition of feudalism, as described by Marc Bloch (1939), includes not only the obligations of the warrior nobility but the obligations of all three estates of the realm: the nobility, the clergy, and the peasantry, all of whom were bound by a system of manorialism; this is sometimes referred to as a "feudal society". Since the publication of Elizabeth A. R. Brown's "The Tyranny of a Construct" (1974) and Susan Reynolds's Fiefs and Vassals (1994), there has been ongoing inconclusive discussion among medieval historians as to whether feudalism is a useful construct for understanding medieval society.[10]

Definition

There is no commonly accepted modern definition of feudalism, at least among scholars.[4][7] The adjective feudal was in use by at least 1405, and the noun feudalism, now often employed in a political and propagandist context, was coined by 1771,[4] paralleling the French féodalité.

According to a classic definition by François Louis Ganshof (1944),[3] feudalism describes a set of reciprocal legal and military obligations which existed among the warrior nobility and revolved around the three key concepts of lords, vassals and fiefs,[3] though Ganshof himself noted that his treatment was only related to the "narrow, technical, legal sense of the word".

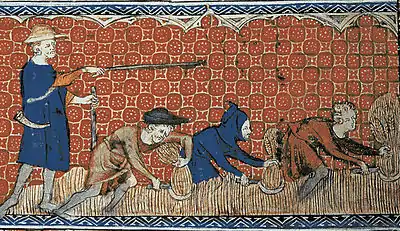

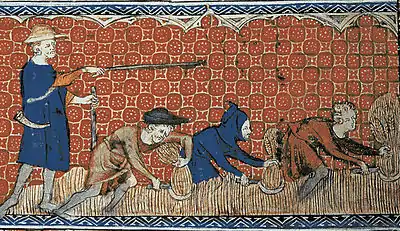

A broader definition, as described in Marc Bloch's Feudal Society (1939),[11] includes not only the obligations of the warrior nobility but the obligations of all three estates of the realm: the nobility, the clergy, and those who lived off their labour, most directly the peasantry which was bound by a system of manorialism; this order is often referred to as a "feudal society", echoing Bloch's usage.

Outside its European context,[4] the concept of feudalism is often used by analogy, most often in discussions of feudal Japan under the shoguns, and sometimes in discussions of the Zagwe dynasty in medieval Ethiopia,[12] which had some feudal characteristics (sometimes called "semifeudal").[13][14] Some have taken the feudalism analogy further, seeing feudalism (or traces of it) in places as diverse as China during the Spring and Autumn period (771-476 BCE), ancient Egypt, the Parthian Empire, feudalism in the Indian subcontinent and the Antebellum South and Jim Crow laws in the American South.[12]

The term feudalism has also been applied—often pejoratively—to non-Western societies where institutions and attitudes which are similar to those which existed in medieval Europe are perceived to prevail.[15] Some historians and political theorists believe that the term feudalism has been deprived of specific meaning by the many ways it has been used, leading them to reject it as a useful concept for understanding society.[4][5]

The applicability of the term feudalism has also been questioned in the context of some Central and Eastern European countries, such as Poland and Lithuania, with scholars observing that the medieval political and economic structure of those countries bears some, but not all, resemblances to the Western European societies commonly described as feudal.[16][17][18][19]

Etymology

The root of the term "feudal" originates in the Proto-Indo-European word *péḱu, meaning "cattle", and possesses cognates in many other Indo-European languages: Sanskrit pacu, "cattle"; Latin pecus (cf. pecunia) "cattle", "money"; Old High German fehu, fihu, "cattle", "property", "money"; Old Frisian fia; Old Saxon fehu; Old English feoh, fioh, feo, fee. The term "féodal" was first used in 17th-century French legal treatises (1614)[20][21] and translated into English legal treatises as an adjective, such as "feodal government".

In the 18th century, Adam Smith, seeking to describe economic systems, effectively coined the forms "feudal government" and "feudal system" in his book The Wealth of Nations (1776).[22] The phrase "feudal system" appeared in 1736, in Baronia Anglica, published nine years after the death of its author Thomas Madox, in 1727. In 1771, in his book The History of Manchester, John Whitaker first introduced the word "feudalism" and the notion of the feudal pyramid.[23][24]

The term "feudal" or "feodal" is derived from the medieval Latin word feodum. The etymology of feodum is complex with multiple theories, some suggesting a Germanic origin (the most widely held view) and others suggesting an Arabic origin. Initially in medieval Latin European documents, a land grant in exchange for service was called a beneficium (Latin).[25] Later, the term feudum, or feodum, began to replace beneficium in the documents.[25] The first attested instance of this is from 984, although more primitive forms were seen up to one-hundred years earlier.[25] The origin of the feudum and why it replaced beneficium has not been well established, but there are multiple theories, described below.[25]

The most widely held theory was proposed by Johan Hendrik Caspar Kern in 1870,[26][27] being supported by, amongst others, William Stubbs[25][28] and Marc Bloch.[25][29][30] Kern derived the word from a putative Frankish term *fehu-ôd, in which *fehu means "cattle" and -ôd means "goods", implying "a movable object of value".[29][30] Bloch explains that by the beginning of the 10th century it was common to value land in monetary terms but to pay for it with objects of equivalent value, such as arms, clothing, horses or food. This was known as feos, a term that took on the general meaning of paying for something in lieu of money. This meaning was then applied to land itself, in which land was used to pay for fealty, such as to a vassal. Thus the old word feos meaning movable property changed little by little to feus meaning the exact opposite: landed property.[29][30] It has also been suggested that word comes from the Gothic faihu, meaning "property", specifically, "cattle".[31]

Another theory was put forward by Archibald Ross Lewis.[25] Lewis said the origin of 'fief' is not feudum (or feodum), but rather foderum, the earliest attested use being in Vita Hludovici (840) by Astronomus.[32] In that text is a passage about Louis the Pious that says annona militaris quas vulgo foderum vocant, which can be translated as "Louis forbade that military provender (which they popularly call "fodder") be furnished."[25]

Another theory by Alauddin Samarrai suggests an Arabic origin, from fuyū (the plural of fay, which literally means "the returned", and was used especially for 'land that has been conquered from enemies that did not fight').[25][33] Samarrai's theory is that early forms of 'fief' include feo, feu, feuz, feuum and others, the plurality of forms strongly suggesting origins from a loanword. The first use of these terms is in Languedoc, one of the least Germanic areas of Europe and bordering Al-Andalus (Muslim Spain). Further, the earliest use of feuum (as a replacement for beneficium) can be dated to 899, the same year a Muslim base at Fraxinetum (La Garde-Freinet) in Provence was established. It is possible, Samarrai says, that French scribes, writing in Latin, attempted to transliterate the Arabic word fuyū (the plural of fay), which was being used by the Muslim invaders and occupiers at the time, resulting in a plurality of forms – feo, feu, feuz, feuum and others – from which eventually feudum derived. Samarrai, however, also advises to handle this theory with care, as Medieval and Early Modern Muslim scribes often used etymologically "fanciful roots" in order to claim the most outlandish things to be of Arabian or Muslim origin.[33]

History

Feudalism, in its various forms, usually emerged as a result of the decentralization of an empire: especially in the Carolingian Empire in 9th century AD, which lacked the bureaucratic infrastructure necessary to support cavalry without allocating land to these mounted troops. Mounted soldiers began to secure a system of hereditary rule over their allocated land and their power over the territory came to encompass the social, political, judicial, and economic spheres.[34]

These acquired powers significantly diminished unitary power in these empires. However, once the infrastructure to maintain unitary power was re-established—as with the European monarchies—feudalism began to yield to this new power structure and eventually disappeared.[34]

Classic feudalism

The classic François Louis Ganshof version of feudalism[4][3] describes a set of reciprocal legal and military obligations which existed among the warrior nobility, revolving around the three key concepts of lords, vassals and fiefs. In broad terms a lord was a noble who held land, a vassal was a person who was granted possession of the land by the lord, and the land was known as a fief. In exchange for the use of the fief and protection by the lord, the vassal would provide some sort of service to the lord. There were many varieties of feudal land tenure, consisting of military and non-military service. The obligations and corresponding rights between lord and vassal concerning the fief form the basis of the feudal relationship.[3]

Vassalage

Before a lord could grant land (a fief) to someone, he had to make that person a vassal. This was done at a formal and symbolic ceremony called a commendation ceremony, which was composed of the two-part act of homage and oath of fealty. During homage, the lord and vassal entered into a contract in which the vassal promised to fight for the lord at his command, whilst the lord agreed to protect the vassal from external forces. Fealty comes from the Latin fidelitas and denotes the fidelity owed by a vassal to his feudal lord. "Fealty" also refers to an oath that more explicitly reinforces the commitments of the vassal made during homage. Such an oath follows homage.[35]

Once the commendation ceremony was complete, the lord and vassal were in a feudal relationship with agreed obligations to one another. The vassal's principal obligation to the lord was to "aid", or military service. Using whatever equipment the vassal could obtain by virtue of the revenues from the fief, the vassal was responsible to answer calls to military service on behalf of the lord. This security of military help was the primary reason the lord entered into the feudal relationship. In addition, the vassal could have other obligations to his lord, such as attendance at his court, whether manorial, baronial, both termed court baron, or at the king's court.[36]

It could also involve the vassal providing "counsel", so that if the lord faced a major decision he would summon all his vassals and hold a council. At the level of the manor this might be a fairly mundane matter of agricultural policy, but also included sentencing by the lord for criminal offences, including capital punishment in some cases. Concerning the king's feudal court, such deliberation could include the question of declaring war. These are examples of feudalism; depending on the period of time and location in Europe, feudal customs and practices varied.

The feudal revolution in France

In its origin, the feudal grant of land had been seen in terms of a personal bond between lord and vassal, but with time and the transformation of fiefs into hereditary holdings, the nature of the system came to be seen as a form of "politics of land" (an expression used by the historian Marc Bloch). The 11th century in France saw what has been called by historians a "feudal revolution" or "mutation" and a "fragmentation of powers" (Bloch) that was unlike the development of feudalism in England or Italy or in Germany in the same period or later:[37] Counties and duchies began to break down into smaller holdings as castellans and lesser seigneurs took control of local lands, and (as comital families had done before them) lesser lords usurped/privatized a wide range of prerogatives and rights of the state, including travel dues, market dues, fees for using woodlands, obligations, use the lord's mill and, most importantly, the highly profitable rights of justice, etc.[38] (what Georges Duby called collectively the "seigneurie banale"[38]). Power in this period became more personal.[39]

This "fragmentation of powers" was not, however, systematic throughout France, and in certain counties (such as Flanders, Normandy, Anjou, Toulouse), counts were able to maintain control of their lands into the 12th century or later.[40] Thus, in some regions (like Normandy and Flanders), the vassal/feudal system was an effective tool for ducal and comital control, linking vassals to their lords; but in other regions, the system led to significant confusion, all the more so as vassals could and frequently did pledge themselves to two or more lords. In response to this, the idea of a "liege lord" was developed (where the obligations to one lord are regarded as superior) in the 12th century.[41]

End of European feudalism (1500–1850s)

Most of the military aspects of feudalism effectively ended by about 1500.[42] This was partly since the military shifted from armies consisting of the nobility to professional fighters thus reducing the nobility's claim on power, but also because the Black Death reduced the nobility's hold over the lower classes. Vestiges of the feudal system hung on in France until the French Revolution of the 1790s. Even when the original feudal relationships had disappeared, there were many institutional remnants of feudalism left in place. Historian Georges Lefebvre explains how at an early stage of the French Revolution, on just one night of August 4, 1789, France abolished the long-lasting remnants of the feudal order. It announced, "The National Assembly abolishes the feudal system entirely." Lefebvre explains:

Without debate the Assembly enthusiastically adopted equality of taxation and redemption of all manorial rights except for those involving personal servitude—which were to be abolished without indemnification. Other proposals followed with the same success: the equality of legal punishment, admission of all to public office, abolition of venality in office, conversion of the tithe into payments subject to redemption, freedom of worship, prohibition of plural holding of benefices ... Privileges of provinces and towns were offered as a last sacrifice.[43]

Originally the peasants were supposed to pay for the release of seigneurial dues; these dues affected more than a quarter of the farmland in France and provided most of the income of the large landowners.[44] The majority refused to pay and in 1793 the obligation was cancelled. Thus the peasants got their land free, and also no longer paid the tithe to the church.[45]

In the Kingdom of France, following the French Revolution, feudalism was abolished with a decree of August 11, 1789 by the Constituent Assembly, a provision that was later extended to various parts of Italian kingdom following the invasion by French troops. In the Kingdom of Naples, Joachim Murat abolished feudalism with the law of August 2, 1806, then implemented with a law of September 1, 1806 and a royal decree of December 3, 1808. In the Kingdom of Sicily the abolishing law was issued by the Sicilian Parliament on August 10, 1812. In Piedmont feudalism ceased by virtue of the edicts of March 7, and July 19, 1797 issued by Charles Emmanuel IV, although in the Kingdom of Sardinia, specifically on the island of Sardinia, feudalism was abolished only with an edict of August 5, 1848.

In the Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia, feudalism was abolished with the law of December 5, 1861 n.º 342 were all feudal bonds abolished. The system lingered on in parts of Central and Eastern Europe as late as the 1850s. Slavery in Romania was abolished in 1856. Russia finally abolished serfdom in 1861.[46][47]

More recently in Scotland, on November 28, 2004, the Abolition of Feudal Tenure etc. (Scotland) Act 2000 entered into full force putting an end to what was left of the Scottish feudal system. The last feudal regime, that of the island of Sark, was abolished in December 2008, when the first democratic elections were held for the election of a local parliament and the appointment of a government. The "revolution" is a consequence of the juridical intervention of the European Parliament, which declared the local constitutional system as contrary to human rights, and, following a series of legal battles, imposed parliamentary democracy.

Feudal society

The phrase "feudal society" as defined by Marc Bloch[11] offers a wider definition than Ganshof's and includes within the feudal structure not only the warrior aristocracy bound by vassalage, but also the peasantry bound by manorialism, and the estates of the Church. Thus the feudal order embraces society from top to bottom, though the "powerful and well-differentiated social group of the urban classes" came to occupy a distinct position to some extent outside the classic feudal hierarchy.

Historiography

The idea of feudalism was unknown and the system it describes was not conceived of as a formal political system by the people living in the medieval period. This section describes the history of the idea of feudalism, how the concept originated among scholars and thinkers, how it changed over time, and modern debates about its use.

Evolution of the concept

| English feudalism |

|---|

|

|

| Manorialism |

|

| Feudal land tenure in England |

|

| Feudal duties |

|

| Feudalism |

The concept of a feudal state or period, in the sense of either a regime or a period dominated by lords who possess financial or social power and prestige, became widely held in the middle of the 18th century, as a result of works such as Montesquieu's De L'Esprit des Lois (1748; published in English as The Spirit of Law), and Henri de Boulainvilliers's Histoire des anciens Parlements de France (1737; published in English as An Historical Account of the Ancient Parliaments of France or States-General of the Kingdom, 1739).[22] In the 18th century, writers of the Enlightenment wrote about feudalism to denigrate the antiquated system of the Ancien Régime, or French monarchy. This was the Age of Enlightenment, when writers valued reason and the Middle Ages were viewed as the "Dark Ages". Enlightenment authors generally mocked and ridiculed anything from the "Dark Ages" including feudalism, projecting its negative characteristics on the current French monarchy as a means of political gain.[48] For them "feudalism" meant seigneurial privileges and prerogatives. When the French Constituent Assembly abolished the "feudal regime" in August 1789, this is what was meant.

Adam Smith used the term "feudal system" to describe a social and economic system defined by inherited social ranks, each of which possessed inherent social and economic privileges and obligations. In such a system, wealth derived from agriculture, which was arranged not according to market forces but on the basis of customary labour services owed by serfs to landowning nobles.[49]

Karl Marx

Karl Marx also used the term in the 19th century in his analysis of society's economic and political development, describing feudalism (or more usually feudal society or the feudal mode of production) as the order coming before capitalism. For Marx, what defined feudalism was the power of the ruling class (the aristocracy) in their control of arable land, leading to a class society based upon the exploitation of the peasants who farm these lands, typically under serfdom and principally by means of labour, produce and money rents.[50] Marx thus defined feudalism primarily by its economic characteristics.

He also took it as a paradigm for understanding the power-relationships between capitalists and wage-labourers in his own time: "in pre-capitalist systems it was obvious that most people did not control their own destiny—under feudalism, for instance, serfs had to work for their lords. Capitalism seems different because people are in theory free to work for themselves or for others as they choose. Yet most workers have as little control over their lives as feudal serfs."[51] Some later Marxist theorists (e.g. Eric Wolf) have applied this label to include non-European societies, grouping feudalism together with imperial China and the Inca Empire, in the pre-Columbian era, as 'tributary' societies .[52]

Later studies

|

| Lord paramount / Territorial lord |

| Tenant-in-chief |

| Mesne lord |

| Lord of the manor / Overlord / Vogt / Liege lord |

| Esquire / Gentleman / Landed gentry |

| Franklin / yeoman / Retinue / Vavasour |

| Free tenant / Husbandman |

| Serf / Villein / Bordar / Cottar |

| Domestic servant |

| Vagabond |

| Slave |

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, J. Horace Round and Frederic William Maitland, both historians of medieval Britain, arrived at different conclusions as to the character of Anglo-Saxon English society before the Norman Conquest in 1066. Round argued that the Normans had brought feudalism with them to England, while Maitland contended that its fundamentals were already in place in Britain before 1066. The debate continues today, but a consensus viewpoint is that England before the Conquest had commendation (which embodied some of the personal elements in feudalism) while William the Conqueror introduced a modified and stricter northern French feudalism to England incorporating (1086) oaths of loyalty to the king by all who held by feudal tenure, even the vassals of his principal vassals (holding by feudal tenure meant that vassals must provide the quota of knights required by the king or a money payment in substitution).

In the 20th century, two outstanding historians offered still more widely differing perspectives. The French historian Marc Bloch, arguably the most influential 20th-century medieval historian,[50] approached feudalism not so much from a legal and military point of view but from a sociological one, presenting in Feudal Society (1939; English 1961) a feudal order not limited solely to the nobility. It is his radical notion that peasants were part of the feudal relationship that sets Bloch apart from his peers: while the vassal performed military service in exchange for the fief, the peasant performed physical labour in return for protection – both are a form of feudal relationship. According to Bloch, other elements of society can be seen in feudal terms; all the aspects of life were centred on "lordship", and so we can speak usefully of a feudal church structure, a feudal courtly (and anti-courtly) literature, and a feudal economy.[50]

In contradistinction to Bloch, the Belgian historian François Louis Ganshof defined feudalism from a narrow legal and military perspective, arguing that feudal relationships existed only within the medieval nobility itself. Ganshof articulated this concept in Qu'est-ce que la féodalité? ("What is feudalism?", 1944; translated in English as Feudalism). His classic definition of feudalism is widely accepted today among medieval scholars,[50] though questioned both by those who view the concept in wider terms and by those who find insufficient uniformity in noble exchanges to support such a model.

Although he was never formally a student in the circle of scholars around Marc Bloch and Lucien Febvre that came to be known as the Annales school, Georges Duby was an exponent of the Annaliste tradition. In a published version of his 1952 doctoral thesis entitled La société aux XIe et XIIe siècles dans la région mâconnaise (Society in the 11th and 12th centuries in the Mâconnais region), and working from the extensive documentary sources surviving from the Burgundian monastery of Cluny, as well as the dioceses of Mâcon and Dijon, Duby excavated the complex social and economic relationships among the individuals and institutions of the Mâconnais region and charted a profound shift in the social structures of medieval society around the year 1000. He argued that in early 11th century, governing institutions—particularly comital courts established under the Carolingian monarchy—that had represented public justice and order in Burgundy during the 9th and 10th centuries receded and gave way to a new feudal order wherein independent aristocratic knights wielded power over peasant communities through strong-arm tactics and threats of violence.

In 1939, the Austrian historian Theodor Mayer subordinated the feudal state as secondary to his concept of a Personenverbandsstaat (personal interdependency state), understanding it in contrast to the territorial state.[53] This form of statehood, identified with the Holy Roman Empire, is described as the most complete form of medieval rule, completing conventional feudal structure of lordship and vassalage with the personal association between the nobility.[54] But the applicability of this concept to cases outside of the Holy Roman Empire has been questioned, as by Susan Reynolds.[55] The concept has also been questioned and superseded in German historiography because of its bias and reductionism towards legitimating the Führerprinzip.

Challenges to the feudal model

In 1974, the American historian Elizabeth A. R. Brown[5] rejected the label feudalism as an anachronism that imparts a false sense of uniformity to the concept. Having noted the current use of many, often contradictory, definitions of feudalism, she argued that the word is only a construct with no basis in medieval reality, an invention of modern historians read back "tyrannically" into the historical record. Supporters of Brown have suggested that the term should be expunged from history textbooks and lectures on medieval history entirely.[50] In Fiefs and Vassals: The Medieval Evidence Reinterpreted (1994),[6] Susan Reynolds expanded upon Brown's original thesis. Although some contemporaries questioned Reynolds's methodology, other historians have supported it and her argument.[50] Reynolds argues:

Too many models of feudalism used for comparisons, even by Marxists, are still either constructed on the 16th-century basis or incorporate what, in a Marxist view, must surely be superficial or irrelevant features from it. Even when one restricts oneself to Europe and to feudalism in its narrow sense it is extremely doubtful whether feudo-vassalic institutions formed a coherent bundle of institutions or concepts that were structurally separate from other institutions and concepts of the time.[56]

The term feudal has also been applied to non-Western societies, in which institutions and attitudes similar to those of medieval Europe are perceived to have prevailed (see: examples of feudalism). Japan has been extensively studied in this regard.[57] Karl Friday notes that in the 21st century historians of Japan rarely invoke feudalism; instead of looking at similarities, specialists attempting comparative analysis concentrate on fundamental differences.[58] Ultimately, critics say, the many ways the term feudalism has been used have deprived it of specific meaning, leading some historians and political theorists to reject it as a useful concept for understanding society.[50]

Richard Abels notes that "Western Civilization and World Civilization textbooks now shy away from the term 'feudalism'."[59]

See also

General

- Barons in Scotland

- Bastard feudalism

- Cestui que

- English feudal barony

- Feudal baron

- Feudal duties

- List of feudal wars 12th–14th century

- Investiture

- Lehnsmann

- Majorat

- Neo-feudalism

- Nulle terre sans seigneur

- Protofeudalism

- Quia Emptores

- Statutes of Mortmain

- Suzerainty

- Vassal state

Non-European

- Fengjian (Chinese)

- Hacienda

- Feudalism in Pakistan

- Mandala (political model)

- Samanta Indian Feudal System

- Small castes

- Ziamet

- Zemene Mesafint

- Sakdina Thai feudal system

References

- feodum – see The Cyclopedic Dictionary of Law, by Walter A. Shumaker, George Foster Longsdorf, pg. 365, 1901.

- Noble, Thomas (2002). The Foundations of Western Civilization. Chantilly, VA: The Teaching Company. ISBN 978-1565856370.

- François Louis Ganshof (1944). Qu'est-ce que la féodalité. Translated into English by Philip Grierson as Feudalism, with a foreword by F. M. Stenton, 1st ed.: New York and London, 1952; 2nd ed: 1961; 3rd ed.: 1976.

- "Feudalism", by Elizabeth A. R. Brown. Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Brown, Elizabeth A. R. (October 1974). "The Tyranny of a Construct: Feudalism and Historians of Medieval Europe". The American Historical Review. 79 (4): 1063–1088. doi:10.2307/1869563. JSTOR 1869563.

- Reynolds, Susan, Fiefs and Vassals: The Medieval Evidence Reinterpreted. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994 ISBN 0-19-820648-8

- "Feudalism?", by Paul Halsall. Internet Medieval Sourcebook.

- "The Problem of Feudalism: An Historiographical Essay", by Robert Harbison, 1996, Western Kentucky University.

- Charles West, Reframing the Feudal Revolution: Political and Social Transformation Between Marne and Moselle, c. 800–c. 1100 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

- [4][5][6][7][8][9]

- Bloch, Marc, Feudal Society. Tr. L.A. Manyon. Two volume. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961 ISBN 0-226-05979-0

- Jessee, W. Scott (1996). Cowley, Robert; Parker, Geoffrey (eds.). "Feudalism". Reader's Companion to Military History. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company. Archived from the original on November 12, 2004.

- "Semifedual". Webster's Dictionary. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

having some characteristics of feudalism

- L. SHelton Woods (2002). Vietnam: A Global Studies Handbook. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576074169. Retrieved October 9, 2019.

- Cf. for example: McDonald, Hamish (October 17, 2007). "Feudal Government Alive and Well in Tonga". Sydney Morning Herald. ISSN 0312-6315. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- Dygo, Marian (2013). "Czy istniał feudalizm w Europie Środkowo-Wschodniej w średniowieczu?". Kwartalnik Historyczny (in Polish). 120 (4): 667. doi:10.12775/KH.2013.120.4.01. ISSN 0023-5903.

- Skwarczyński, P. (1956). "The Problem of Feudalism in Poland up to the Beginning of the 16th Century". The Slavonic and East European Review. 34 (83): 292–310. ISSN 0037-6795. JSTOR 4204744.

- Backus, Oswald P. (1962). "The Problem of Feudalism in Lithuania, 1506-1548". Slavic Review. 21 (4): 639–659. doi:10.2307/3000579. ISSN 0037-6779. JSTOR 3000579.

- Davies, Norman (2005). God's Playground A History of Poland: Volume 1: The Origins to 1795. OUP Oxford. pp. 165–166. ISBN 978-0-19-925339-5.

- "Feudal (n.d.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved September 16, 2007.

- Cantor, Norman F. (1994). The Civilization of the Middle Ages. ISBN 9780060170332.

- Fredric L. Cheyette. "FEUDALISM, EUROPEAN." in New Dictionary of the History Of Ideas, Vol. 2, ed. Maryanne Cline Horowitz, Thomas Gale 2005, ISBN 0-684-31379-0. pp. 828–831

- Elizabeth A. R. Brown, "Reflections on Feudalism: Thomas Madox and the Origins of the Feudal System in England," in Feud, Violence and Practice: Essays in Medieval Studies in Honor of Stephen D. White, ed. Belle S. Tuten and Tracey L. Billado (Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2010), 135-155 at 145-149.

- John Whitaker (1773). The History of Manchester: In Four Books. J. Murray. p. 359.

- Meir Lubetski (ed.). Boundaries of the ancient Near Eastern world: a tribute to Cyrus H. Gordon. "Notices on Pe'ah, Fay' and Feudum" by Alauddin Samarrai. Pg. 248–250, Continuum International Publishing Group, 1998.

- "fee, n.2." OED Online. Oxford University Press, June 2017. Web. August 18, 2017.

- H. Kern, 'Feodum', De taal- en letterbode, 1( 1870), pp. 189-201.

- William Stubbs. The Constitutional History of England (3 volumes), 2nd edition 1875–78, Vol. 1, pg. 251, n. 1

- Marc Bloch. Feudal Society, Vol. 1, 1964. pp.165–66.

- Marc Bloch. Feudalism, 1961, pg. 106.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, 9th.ed. vol. 9, p.119.

- Archibald R. Lewis. The Development of Southern French and Catalan Society 718–1050, 1965, pp. 76–77.

- Alauddin Samarrai. "The term 'fief': A possible Arabic origin", Studies in Medieval Culture, 4.1 (1973), pp. 78–82.

- Gat, Azar. War in Human Civilization, New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. pp. 332–343

- Medieval Feudalism Archived 2012-02-09 at the Wayback Machine, by Carl Stephenson. Cornell University Press, 1942. Classic introduction to Feudalism.

- Encyc. Brit. op.cit. It was a standard part of the feudal contract (fief [land], fealty [oath of allegiance], faith [belief in God]) that every tenant was under an obligation to attend his overlord's court to advise and support him; Sir Harris Nicolas, in Historic Peerage of England, ed. Courthope, p.18, quoted by Encyc. Brit, op.cit., p. 388: "It was the principle of the feudal system that every tenant should attend the court of his immediate superior".

- Chris Wickham, The Inheritance of Rome, p. 522-3.

- Wickham, The Inheritance of Rome, p. 518.

- Wickham, The Inheritance of Rome, p.522.

- Wickham, p.523.

- Elizabeth M. Hallam. Capetian France 987–1328, p.17.

- "The End of Feudalism" in J.H.M. Salmon, Society in Crisis: France in the Sixteenth Century (1979) pp 19–26

- Lefebvre, Georges (1962). The French Revolution: Vol. 1, from Its Origins To 1793. Columbia U.P. p. 130. ISBN 9780231085984.

- Forster, Robert (1967). "The Survival of the Nobility during the French Revolution". Past & Present. 37 (37): 71–86. doi:10.1093/past/37.1.71. JSTOR 650023.

- Paul R. Hanson, The A to Z of the French Revolution (2013) pp 293–94

- John Merriman, A History of Modern Europe: From the Renaissance to the Age of Napoleon (1996) pp 12–13

- Jerzy Topolski, Continuity and discontinuity in the development of the feudal system in Eastern Europe (Xth to XVIIth centuries)" Journal of European Economic History (1981) 10#2 pp: 373–400.

- Robert Bartlett. "Perspectives on the Medieval World" in Medieval Panorama, 2001, ISBN 0-89236-642-7

- Richard Abels. "Feudalism". usna.edu. Archived from the original on July 5, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- Philip Daileader, "Feudalism", The High Middle Ages, Course No. 869, The Teaching Company, ISBN 1-56585-827-1

- Peter Singer, Marx: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000) [first published 1980], p. 91.

- Wolf, Eric Robert (2010). Europe and the people without history. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-26818-0. OCLC 905625305.

- Bentley, Michael (2006). Companion to Historiography. Routledge. p. 126. ISBN 9781134970247. Retrieved November 17, 2019.

- Elazar, Daniel Judah (1996). Covenant and commonwealth : from Christian separation through the Protestant Reformation. Vol. 2. Transaction Publishers. p. 76. ISBN 9781412820523. Retrieved November 17, 2019.

- Raynolds, Susan (1996). Fiefs and Vassals: The Medieval Evidence Reinterpreted. Oxford University Press. p. 397. ISBN 9780198206484. Retrieved November 17, 2019.

- Reynolds, p 11

- Hall, John Whitney (1962). "Feudalism in Japan-A Reassessment". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 5 (1): 15–51. doi:10.1017/S001041750000150X. JSTOR 177767. S2CID 145750386.

- Karl Friday, "The Futile Paradigm: In Quest of Feudalism in Early Medieval Japan," History Compass 8.2 (2010): 179–196.

- Richard Abels, "The Historiography of a Construct: 'Feudalism' and the Medieval Historian." History Compass (2009) 7#3 pp: 1008–1031.

Further reading

- Bloch, Marc, Feudal Society. Tr. L.A. Manyon. Two volumes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961 ISBN 0-226-05979-0

- Ganshof, François Louis (1952). Feudalism. London; New York: Longmans, Green. ISBN 978-0-8020-7158-3.

- Guerreau, Alain, L'avenir d'un passé incertain. Paris: Le Seuil, 2001. (Complete history of the meaning of the term.)

- Poly, Jean-Pierre and Bournazel, Eric, The Feudal Transformation, 900–1200., Tr. Caroline Higgitt. New York and London: Holmes and Meier, 1991.

- Reynolds, Susan, Fiefs and Vassals: The Medieval Evidence Reinterpreted. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994 ISBN 0-19-820648-8

Historiographical works

- Abels, Richard (2009). "The Historiography of a Construct: "Feudalism" and the Medieval Historian". History Compass. 7 (3): 1008–1031. doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2009.00610.x.

- Brown, Elizabeth, 'The Tyranny of a Construct: Feudalism and Historians of Medieval Europe', American Historical Review, 79 (1974), pp. 1063–8.

- Cantor, Norman F., Inventing the Middle Ages: The Lives, Works, and Ideas of the Great Medievalists of the Twentieth century. Quill, 1991.

- Friday, Karl (2010). "The Futile Paradigm: In Quest of Feudalism in Early Medieval Japan". History Compass. 8 (2): 179–196. doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2009.00664.x.

- Harbison, Robert. "The Problem of Feudalism: An Historiographical Essay", 1996, Western Kentucky University. online

End of feudalism

- Bean, J.M.W. Decline of English Feudalism, 1215–1540 (1968)

- Davitt, Michael. The fall of feudalism in Ireland: Or, The story of the land league revolution (1904)

- Hall, John Whitney (1962). "Feudalism in Japan-A Reassessment". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 5 (1): 15–51. doi:10.1017/S001041750000150X. JSTOR 177767. S2CID 145750386.; compares Europe and Japan

- Nell, Edward J. "Economic Relationships in the Decline of Feudalism: An Examination of Economic Interdependence and Social Change." History and Theory (1967): 313–350. in JSTOR

- Okey, Robin. Eastern Europe 1740–1985: feudalism to communism (Routledge, 1986)

France

- Herbert, Sydney. The Fall of Feudalism in France (1921) full text online free

- Mackrell, John Quentin Colborne. The Attack on Feudalism in Eighteenth-century France (Routledge, 2013)

- Markoff, John. Abolition of Feudalism: Peasants, Lords, and Legislators in the French Revolution (Penn State Press, 2010)

- Sutherland, D. M. G. (2002). "Peasants, Lords, and Leviathan: Winners and Losers from the Abolition of French Feudalism, 1780-1820". The Journal of Economic History. 62 (1): 1–24. JSTOR 2697970.

Global Health

- Keshri VR, Bhaumik S (2022) . The feudal structure of global health and its implications for decolonisation . BMJ Global Health Available online https://gh.bmj.com/content/7/9/e010603

External links

- "Feudalism", by Elizabeth A. R. Brown. Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- "Feudalism?", by Paul Halsall. Internet Medieval Sourcebook.

- "Feudalism: the history of an idea", by Fredric Cheyette (Amherst), excerpted from New Dictionary of the History of Ideas (2004)

- Medieval Feudalism, by Carl Stephenson. Cornell University Press, 1942. Classic introduction to Feudalism.

- "The Problem of Feudalism: An Historiographical Essay" at the Wayback Machine (archived February 26, 2009), by Robert Harbison, 1996, Western Kentucky University.