First Republic of Armenia

The First Republic of Armenia,[9] officially known at the time of its existence as the Republic of Armenia (classical Armenian: Հայաստանի հանրապետութիւն),[lower-alpha 1] was the first modern Armenian state since the loss of Armenian statehood in the Middle Ages.[lower-alpha 2]

Republic of Armenia Հայաստանի Հանրապետութիւն | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1918–1920 | |||||||||||||

.svg.png.webp) Flag | |||||||||||||

| Anthem: Mer Hayrenik | |||||||||||||

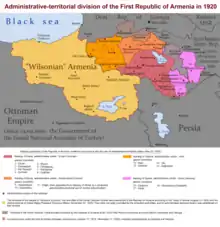

First Republic of Armenia in 1918–1920. | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Erivan (present-day Yerevan) | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Armenian | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Armenian Apostolic | ||||||||||||

| Government | Parliamentary republic | ||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||

• June 1918–May 1919 | Hovhannes Kajaznuni | ||||||||||||

• May 1919–May 1920 | Alexander Khatisian | ||||||||||||

• May–November 1920 | Hamo Ohanjanyan | ||||||||||||

• November–December 1920 | Simon Vratsian | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | Khorhrdaran | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Interwar period | ||||||||||||

• Declaration of Independence | 28 May 1918 | ||||||||||||

• Act of United Armenia | 28 May 1919 | ||||||||||||

• Sovietization | 2 December 1920 | ||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| mid-1918 (after the Treaty of Batum)[1][2] | 11,000 km2 (4,200 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| 1919 (after the Armistice of Mudros)[3][4] | 70,000 km2 (27,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| 1920 (per the Treaty of Sèvres)[5] | 160,000 km2 (62,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

| 500,000 | |||||||||||||

| 1,300,000 | |||||||||||||

| Currency | Armenian rouble | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Armenia Artsakh Azerbaijan Georgia Turkey | ||||||||||||

The republic was established in the Armenian-populated territories of the disintegrated Russian Empire, known as Eastern Armenia or Russian Armenia. The leaders of the government came mostly from the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF or Dashnaktsutyun). The First Republic of Armenia bordered the Democratic Republic of Georgia to the north, the Ottoman Empire to the west, Persia to the south, and the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic to the east. It had a total land area of roughly 70,000 km2, and a population of 1.3 million.

The Armenian National Council declared the independence of Armenia on 28 May 1918. From its very onset, Armenia was plagued with a variety of domestic and foreign issues. A humanitarian crisis emerged from the aftermath of the Armenian genocide as hundreds of thousands of Armenian refugees from the Ottoman Empire were forced to settle in the fledgling republic.[22] Lasting two and a half years in existence, the Republic of Armenia became involved in several armed conflicts with its neighbors, caused by overlapping territorial claims. By late 1920, the nation was partitioned between the Turkish Nationalist forces and Russian Red Army. The First Republic, along with the Republic of Mountainous Armenia which repelled the Soviet invasion until July 1921, ceased to exist as an independent state, superseded by the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic that became part of the Soviet Union in 1922. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the republic regained its independence as the current Republic of Armenia in 1991.[23]

Background

The Russian offensive during the Caucasus Campaign of World War I, the subsequent occupation, and the creation of a provisional administrative government gave hope for ending Ottoman Turkish rule in Western Armenia. With the help of several battalions of Armenians recruited from the Russian Empire, the Russian army had made progress on the Caucasus Front, advancing as far as the city of Erzurum in 1916. The Russians continued to make considerable advances even after the toppling of Tsar Nicholas II in February 1917.[24]

In March 1917, the spontaneous revolution that toppled Tsar Nicholas and the Romanov dynasty established a caretaker administration, known as the Provisional Government. Shortly after, the Provisional Government replaced Grand Duke Nicholas' administration in the Caucasus with the five-member Special Transcaucasian Committee, known by the acronym Ozakom. The Ozakom included Armenian Democrat Mikayel Papadjanian, and was set to heal wounds inflicted by the old regime. In doing so, Western Armenia was to have a general commissar and was to be subdivided into the districts of Trebizond, Erzerum, Bitlis, and Van.[25] The decree was a major concession to the Armenians: Western Armenia was placed under the central government and through it under immediate Armenian jurisdiction. Dr. Hakob Zavriev would serve as the assistant for civil affairs and he in turn would see to it that most civil officials were Armenian.

In October 1917, the Bolsheviks seized power from the Provisional Government and announced that they would be withdrawing troops from both the Western and Caucasus fronts.[26] The Armenians, Georgians, and Muslims of the Caucasus all rejected the Bolsheviks' legitimacy.

Towards independence

On 5 December 1917, the Ottoman Empire and the Transcaucasian Commissariat signed the armistice of Erzincan, ending armed conflict. After the Bolshevik seizure of power, a multinational congress of Transcaucasian representatives met to create a provisional regional executive body known as the Transcaucasian Seim. The Commissariat and the Seim were heavily encumbered by the pretense that the South Caucasus formed an integral unit of a non-existent Russian democracy.[27] The Armenian deputies in the Seim were hopeful that the anti-Bolshevik forces in Russia would prevail in the Russian Civil War and rejected any idea of separating from Russia. In February 1918, the Armenians, Georgians and Muslims had reluctantly joined to form the Transcaucasian Federation, but disputes among the three groups continued as unity began to falter.

On 3 March 1918, Russia followed the armistice of Erzincan with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and left the war. It ceded territory from 14 March to April 1918, when a conference was held between the Ottoman Empire and the delegation of the Seim. Under the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the Russians allowed the Turks to retake the Western Armenian provinces, as well as to take over the provinces of Kars, Batum, and Ardahan.

In addition to these provisions, a secret clause obligated the Armenians and Russians to demobilize their forces in both western and eastern Armenia.[28] Having killed and deported most of Armenians of Western Armenia during the Armenian genocide, the Ottoman Empire intended to eliminate the Armenian population of Eastern Armenia.[29] Shortly after the signing of Brest-Litovsk the Turkish army began its advance, taking Erzurum in March and Kars in April, which the Transcaucasian government of Nikolay Chkheidze had ordered soldiers to abandon. Beginning on 21 May, the Ottoman army moved ahead again.

On 11 May 1918, a new peace conference opened at Batum. At this conference, the Ottomans extended their demands to include Tiflis, as well as Alexandropol and Echmiadzin, which they wanted for a railroad to be built to connect Kars and Julfa with Baku. The Armenian and Georgian members of the Republic's delegation began to stall.

On 26 May 1918, Georgia declared independence; on 28 May, it signed the Treaty of Poti, and received protection from Germany.[30] The following day, the Muslim National Council in Tiflis announced the establishment of the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan.

Having been abandoned by its regional allies, the Armenian National Council, based in Tiflis and led by Russian Armenian intellectuals who represented Armenian interests in the Caucasus, declared its independence on May 28.[31] It dispatched Hovhannes Kajaznuni and Alexander Khatisyan, both members of the ARF, to Yerevan to take over power and issued the following statement on 30 May (retroactive to 28 May):

In view of the dissolution of the political unity of Transcaucasia and the new situation created by the proclamation of the independence of Georgia and Azerbaijan, the Armenian National Council declares itself to be the supreme and only administration for the Armenian provinces. Because of the certain grave circumstances, the national council, deferring until the near future the formation of an Armenian National government, temporarily assumes all governmental functions, in order to take hold the political and administrative helm of the Armenian provinces.[32]

Meanwhile, the Turks had taken Alexandropol and were intent on eliminating the center of Armenian resistance based in Yerevan. The Armenians were able to stave off total defeat and delivered crushing blows to the Turkish army in the battles of Sardarapat, Karakilisa and Abaran.

The Republic of Armenia had to sue for negotiations at the Treaty of Batum, which was signed in Batum on 4 June 1918. It was Armenia's first treaty. After the Ottoman Empire took vast swathes of territory and imposed harsh conditions, the new republic was left with 10,000 square kilometers.[33]

Administration

On 30 May 1918 the Armenian Revolutionary Federation had decided that Armenia should be a republic under a provisional coalition government. The declaration stated that the Republic of Armenia was to be a self-governing state, endowed with a constitution, the supremacy of state authority, independence, sovereignty, and plenipotentiary power. Kajaznuni became the country's first Prime Minister and Aram Manukian was the first minister of Interior.

The constitution granted universal suffrage to all citizens, regardless of qualifiers, who were at least twenty years old. The first elections under the new constitution occurred between 21 and 23 June 1919 and of the 80 members elected to Parliament, three were women: Perchuhi Partizpanyan-Barseghyan, Varvara Sahakyan and Katarine Zalyan-Manukyan[34]

Armenia established a Ministry of Interior and created a police force. The Armenian parliament passed a law on the police on 21 April 1920, specifying its structure, jurisdiction, and responsibilities. The Interior Ministry was also responsible for communications and telegraph, railroad, and the public school system, in addition to enforcing law and order. The reforms came soon and each of these departments became ministries.

In 1919, the leaders of the Republic had to deal with issues on three fronts: domestic, regional, and international. The Armenian Congress of Eastern Armenians that took control in 1918 fell apart and in June 1919, the first national elections would be held. During the 1920s, which began under the premiership of Hovhannes Kajaznuni, Armenians from within the former Russian Empire and the United States would assist in developing the fledgling Republic's judicial system. In January 1919 another important milestone was completed by the Armenian Parliament, which was the opening of the country's first state university, Yerevan State University.

Ministers of the Republic of Armenia

Speaker of the Khorhurd

- Serop Zakaryan (30 June 1918 – 1 August 1918)

- Avetik Sahakyan (1 August 1918 – 1 August 1919)

- Avetis Aharonian (1 August 1919 – 4 November 1920)

- Hovhannes Kajaznuni (4 November 1920 – 2 December 1920)

Prime Minister

- Hovhannes Kajaznuni (30 June 1918 – 28 May 1919) (in Tbilisi, Georgia until 19 July 1918)

- Alexander Khatisian (28 May 1919 – 5 May 1920)

- Hamazasp "Hamo" Ohanjanian (5 May 1920 – 23 November 1920)

- Simon Vratsian (23 November 1920 – 2 December 1920)

Minister of Foreign Affairs

- Alexander Khatisian (30 June 1918 – 4 November 1918)

- Sirakan Tigranian (4 November 1918 – 27 April 1919)

- Alexandre Khatisian (27 April 1919 – 5 May 1920)

- Hamazasp "Hamo" Ohanjanian (3 April 1920 – 23 November 1920)

- Simon Vratsian (23 November 1920 – 2 December 1920)

Minister of Internal Affairs

- Aram Manukian (4 November 1918 – 29 January 1919)

- Alexandre Khatisian (26 January 1919 – 27 April 1919)

- Sargis Manasian (27 April 1919 – 10 August 1919)

- Abraham Giulkhandanian (10 August 1919 – 5 May 1920)

- Ruben Ter Minasian (5 May 1920 – 24 November 1920)

- Sargis Araratyan (24 November – 2 December 1920)

Minister of Military Affairs

- Hovhannes Hakhverdian (15 March 1918 – 27 March 1919)

- Kristapor Araratian (27 March 1919 – 3 April 1920)

- Ruben Ter Minasian (5 May 1920 – 24 November 1920)

- Drastamat Kanayan (24 November 1920 – 2 December 1920)

Minister of Financial Affairs

- Artashes Enfiadjian (4 November 1918 – 27 April 1919)

- Grigor Jaghetyan (24 April 1919 – 5 August 1919)

- Sargis Araratian (10 August 1919 – 5 May 1920)

- Artashes Enfiadjian (5 May 1920 – 24 November 1920)

- Hambardzum Terteryan (25 November 1920 – 2 December 1920)

Minister of Judicial Affairs (Justice)

- Samson Harutiunian (4 November 1918 – 27 April 1919)

- Harutiun Chmshkian (27 April 1919 – 10 August 1919)

- Abraham Giulkhandanian (10 August 1919 – 10 September 1920)

- Artashes Chilingarian (24 October 1920 – 23 November 1920)

- Arsham Khondkaryan (23 November 1920 – 2 December 1920)

Minister of Enlightenment (Public Instruction)

- Mikayel Atabekian (4 November 1918 - 4 December 1918)

- Gevorg Melik-Karageozian (4 December 1918 – June 24, 1919)

- Sirakan Tigranian (5 August 1919 – 24 June 1919)

- Nikol Aghbalian (1 August 1919 – 5 May 1920)

- Ghaz Ghazaryan (5 May 1920 – 23 November 1920)

- Vahan Minakhoryan (23 November 1920 – 2 December 1920)

Minister of Provisions

- Levon Ghulian (4 November 1918 – 27 April 1919)

- Kristapor Vermishian (27 April 1919 – 24 June 1919)

- Sahak Torosyan (5 May 1920 – 25 November 1920

Minister of Welfare (Public Assistance)

- Khachatur Kaijikian (4 November 1918 – 11 November 1918)

- Levon Ghulian (11 November 1918 – 13 December 1918)

- Christophor Vermishyan (13 December 1918 - 7 February 1919)

- Sahak Torosian (7 February 1919 – 24 June 1919)

- Avetik Sahakian (10 August 1919 – 31 October 1920

- Artashes Babalian (31 October 1919 – 5 May 1920)

- Sargis Araratyan (5 May 1920 – 25 November 1920)

- Hambardzum Terteryan (25 November 1920 – 2 December 1920)

Minister of Agricultural Administration

- Avetik Sahakian (1 August 1919 – 2 December 1920)

Minister of State Control

- Grigor Djaghetian (10 September 1919 – 2 December 1920)

Minister of Communications

- Arshak Djamalian (3 April 1920 – 23 November 1920

- Arsham Khondkaryan (25 November 1920 – 2 December 1920)

Military

Thanks to the efforts of Armenian National Council of Tiflis, the Armenian National Corps was established to fight against the Ottoman offensive of late 1917 and early 1918. On 13 December 1917, the Armenian National Corps was established, with General Tovmas Nazarbekian was appointed commander and Drastamat Kanayan became the defence minister. Nazarbekian used his experience in the Russian Caucasus Army to aid in the creation of the regular army.[35] Units of this corps formed the basis of the Armenian army. Armenian conscripts and volunteers from the Russian Army later established the core of the armed forces of the First Republic. In accordance with the harsh terms of the Treaty of Batum signed on 4 June 1918 the Ottoman Empire demobilized most of the Armenian army. They were allowed only a limited force and were severely restricted in where their troops could operate.[36]

Organization

The Armenian National Corps had the following military units[37]

- 2 rifle divisions, which included 6 artillery batteries

- one cavalry brigade

- Armenian (volunteer) Division, which included:

- 1st Brigade (Erzurum Regiment and the Yerznka Regiment)

- 2nd Brigade (Khnus Regiment, Gharakilisa Regiment, Van Regiment and the Zeytun Regiment)

- Local army militia units:

- Lori Regiment

- Shushi Regiment

- Akhalkalaki Regiment

- Kazakh Regiment

- Nukhi Detachment

- Akhaltsikhe Detachment

- Igdir Detachment

- Khanasor Detachment

Administrative divisions

| Province (Nahang)[40][41] | Center | Counties (Gavars) | Location | Population (1916)[42] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ararat

Արարատյան նահանգ Araratyan nahang |

Erevan (Yerevan) | - Erevan

- Etchmiadzin - Nor Bayazet - Surmalu - Sharur - Daralagyaz - Nakhichevan - Goghtan |

South of Erivan

Ararat plain, Igdir, Kotayk, Lake Sevan, Nakhichevan, Vayots Dzor |

866,000 |

| Vanand

Վանանդի նահանգ Vanandi nahang |

Kars | - Kars

- Kaghzvan - Voghtik - Ardahan |

Most of Kars

Historical region of Vanand |

404,000 |

| Shirak

Շիրակի նահանգ Shiraki nahang |

Alexandropol (Gyumri) | - Alexandropol

- Karakalisa - Dilijan |

North of Erivan

Historical regions of Shirak, Lori, Javakhk and Tavush |

518,000 |

| Syunik

Սյունիքի նահանգ Syunik’i nahang |

Gerusy (Goris) | - Zangezur

- Kapan - Mountainous Karabakh |

Southwest of Elisabethpol

Historical regions of Syunik and Artsakh |

442,000 |

The Armenian republic included the following subdivisions of the former Russian Empire:[43]

| District (okrug/uyezd) | Section | Population (1916)[42] |

|---|---|---|

| Erivan Governorate | 1,120,242 | |

| All | All (Nakhichevan Uyezd partially controlled by Muslim militias) | 1,120,242 |

| Kars Oblast | 404,305 | |

| Kars | All | 191,970 |

| Kaghizvan | All | 83,208 |

| Olti | All (partially controlled by Muslim militias of Japhar-Bey)[22] | 40,091 |

| Ardahan | Southern section (up to Kura River) | 89,036 |

| Elisabethpol Governorate | 717,506 | |

| Zangezur | Mountainous section (controlled by forces of Andranik Ozanian) | 226,398 |

| Kazakh | Mountainous section | 137,049 |

| Shusha | Mountainous section | 188,745 |

| Jevanshir | Mountainous section | 75,730 |

| Karyagino (Jebrayil) | Mountainous section | 89,584 |

| Tiflis Governorate | 169,351 | |

| Borchaly | Southern section (Lori uchastok) | 169,351 |

Demographics

Background

Before World War I, in 1914, the territory was part of Russian Armenia; among the total Armenian population of 2,800,000, about 1,500,000 lived in the Ottoman Empire, and the remainder were in Russian Armenia.[3] An estimate in 1918, during the new Armenian Republic's first year, indicated that there were 800,000 Armenians and more than 100,000 Muslims, mostly Ottoman Turks, and Azerbaijani Turks and Kurds everywhere else. Of the 800,000 Armenians, about 500,000 were native Russian Armenians and 300,000 were destitute and starving refugees fleeing from the massacres that took place in the Ottoman Empire.[44]

The surviving Armenian population in 1919 was 2,500,000, two million of whom were distributed in the Caucasus.[3] Of these 2,000,000 in the Caucasus, 1,300,000 were to be found within the boundaries of the new Republic of Armenia, which included 300,000 to 350,000 refugees who had escaped from the Ottoman Empire.[3] There were 1,650,000 Armenians in the new Republic.[3] Also added to this Armenian population were 350,000 to 400,000 people of other nationalities, and a total population of about 2,000,000 within the Armenian Republic.[3]

The surviving Armenian population in 1921 was 1,200,000 in the republic, 400,000 in Georgia, 340,000 in Azerbaijan and those in the other regions of the Caucasus brought the total to 2,195,000.[45]

| Country | 1914[3] | 1918[46] | 1919[3] | 1921[45] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russian Empire

(later Soviet Union) |

Armenia | 1,300,000 | 470,000 | 1,293,000 | 1,200,000 |

| Azerbaijan | 653,000 | 700,000 | 340,000 | ||

| Georgia | 535,000 | 400,000 | |||

| Other | 255,000 | ||||

| Ottoman Empire (later Republic of Turkey) | 1,500,000 | 500,000 | 281,000 | ||

| Other | 528,000 | ||||

| TOTAL | 2,800,000 | 1,658,000 | 2,493,000 | 3,004,000 | |

Population

| Faith | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Armenians | 470,000 | 69.22 |

| Muslims | 168,000 | 24.74 |

| Others | 41,000 | 6.04 |

| TOTAL | 679,000 | 100.00 |

| Nationality | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Armenians | 1,293,000 | 59.89 |

| Turkic peoples | 588,000 | 27.23 |

| Russians and Greeks | 110,000 | 5.09 |

| Kurds | 82,000 | 3.80 |

| Yazidis and Roma | 73,000 | 3.38 |

| Georgians | 13,000 | 0.60 |

| TOTAL | 2,159,000 | 100.00 |

| Faith | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Armenians | 1,293,000 | 59.89 |

| Muslims | 670,000 | 31.03 |

| Orthodox | 123,000 | 5.70 |

| Pagans | 73,000 | 3.38 |

| TOTAL | 2,159,000 | 100.00 |

| Nationality | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Armenians | 1,012,787 | 70.83 |

| ↳ Natives | 775,111 | 54.21 |

| ↳ Refugees | 237,676 | 16.62 |

| Tatars | 312,611 | 21.86 |

| Kurds | 39,492 | 2.76 |

| Yazidis | 31,793 | 2.22 |

| Russians | 27,200 | 1.90 |

| Turks | 6,000 | 0.42 |

| Greeks | 6,000 | 0.42 |

| TOTAL | 1,429,882 | 100.00 |

Paris peace conference memorandum

In a memorandum to the Paris peace conference of the territorial claims of "Integral Armenia", the Armenian delegation included the whole Erivan Governorate, most of the Kars Oblast, the southwestern parts of the Tiflis Governorate, and the western part of the Elisabethpol Governorate. The nationalities of each claimed region is as follows:

| District | Armenian | Tatar[lower-alpha 3] | Other | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kazakh | 61,000 | 9,000 | 1,929 | 71,929 |

| Elisabethpol | 52,000 | 16,500 | 8,200 | 76,700 |

| Jevanshir | 22,000 | 17,000 | — | 39,000 |

| Shusha | 98,000 | 30,000 | — | 128,000 |

| Karyagino[lower-alpha 4] | 22,000 | — | — | 22,000 |

| Zangezur | 100,000 | 50,000 | — | 150,000 |

| Elisabethpol | 355,000 | 122,500 | 10,129 | 487,629 |

| Akhalkalaki | 82,275 | 8,308 | 16,091 | 106,674 |

| Borchaly | 64,000 | 9,600 | 21,650 | 95,250 |

| Gori | 1,200 | — | — | 1,200 |

| Tiflis | 147,475 | 17,908 | 37,741 | 203,124 |

| Ardahan | 470 | 15,550 | 21,720 | 37,740 |

| Kagizman | 34,721 | 5,782 | 42,305 | 82,808 |

| Kars | 80,752 | 51,659 | 45,177 | 177,588 |

| Olti | 4,953 | 330 | 34,914 | 40,197 |

| Kars | 120,896 | 73,321 | 144,116 | 338,333 |

| Erivan | 669,871 | 373,841 | 70,986 | 1,114,698 |

| TOTAL | 1,293,000 | 588,000 | 279,000 | 2,160,000 |

Refugee crisis

There was also an Armenian settlement problem that brought conflict with other ethnic residents. In all, there were over 300,000 embittered and impatient Armenian refugees escaping from the Armenian genocide in the Ottoman Empire who were now the government's responsibility. This proved an insurmountable humanitarian issue. Typhus was a major sickness, because of its effect on children. Conditions in the outlying regions, not necessarily consisting of refugees, weren't any better. The Ottoman governing structure and Russian army had already withdrawn from the region. The Armenian government had neither time nor resources to rebuild the infrastructure. In 1918, the throngs of refugees were distributed as follows:

.jpg.webp)

| External image | |

|---|---|

| Famine | |

| Districts | Refugees |

|---|---|

| Erevan (Yerevan) | 75,000 |

| Etchmiadzin (Vagharshapat) | 70,000 |

| Novo-Bayazit (Gavar) | 38,000 |

| Daralagiaz (Vayots Dzor) | 36,000 |

| Bash-Abaran (Aparan) | 35,000 |

| Ashtarak | 30,000 |

| Akhta (Hrazdan)-Elenovka (Sevan) | 22,000 |

| Bash-Garni (Garni) | 15,000 |

| Karakilisa (Vanadzor) | 16,000 |

| Dilijan | 13,000 |

| TOTAL | 350,000 |

The government of Hovhannes Kajaznuni was faced with a most sobering reality in the winter of 1918–19. The newly formed government was responsible for over half a million Armenian refugees in the Caucasus. It was a long and harsh winter.[50] The homeless masses, lacking food, clothing and medicine, had to endure the elements. Many who survived the exposure and famine succumbed to the ravaging diseases. By the spring of 1919, the typhus epidemic had run its course, the weather improved and the first American Committee for Relief in the Near East shipment of wheat reached Batum. The British army transported the aid to Yerevan. Yet by that time some 150,000 of the refugees had perished. Vratsian puts this figure at around 180,000, or nearly 20% of the entire nascent Republic. 40% of the inhabitants of eight villages near Etchmiadzin and 25% of the sixteen villages in neighboring Ashtarak had succumbed by April. During the winter of 1918-1919 the population of Talin, a district midway between Etchmiadzin and Alexandropol, was cut in half and nearly 60% of the Armenians in the Surmalu uyezd starved to death.[51]

By 6 April 1920, the refugees from parts of Russian Armenia occupied by the Ottoman Army in 1918 had been largely resettled, however, 310,835 refugees from Western Armenia were still distributed around the Armenian Republic awaiting the political resolution and unification of their homeland to the eastern Armenian state. There were also 11,099 Armenian orphans throughout orphanages in Transcaucasia, 7,523 of whom were within the borders of Armenia.[52] Western Armenian refugees and orphans were distributed as follows:[52]

| Country | Province | Town | Refugees | Orphans |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ararat Nahang | Yerevan | 62,590 | 1,375 | |

| Etchmiadzin | 43,762 | 357 | ||

| Nor Bayazet | 6,610 | 100 | ||

| Igdir | 6,300 | ... | ||

| Keshishkend | 6,082 | ... | ||

| Bash Aparan | ... | 1,600 | ||

| Ashtarak | ... | 881 | ||

| Shirak Nahang | Alexandropol | 94,856 | ... | |

| Gharakalisa | 26,443 | 293 | ||

| Dilijan | 7,192 | 453 | ||

| Jalaloghli | ... | 898 | ||

| Hamamlu | ... | 65 | ||

| Vanand Nahang | Kars | 57,000 | 1,476 | |

| Kaghzvan | ... | 25 | ||

| Tiflis Governorate | Tiflis | ... | 2,400 | |

| Ganja Governorate | Elizavetpol | ... | 150 | |

| Total | 310,835 | 10,073 | ||

Foreign relations

Consolidation of territory

By 1920, the Republic of Armenia administered an area that covered most of present-day Armenia, in addition to most of the Kars, Surmalu and Nakhichevan districts. The regions of Nakhichevan, Nagorno-Karabakh, Zangezur (corresponding to the contemporary province of Syunik), and Dilijan (also referred to as Kazakh-Shamshadin, corresponding to the contemporary province of Tavush) were strongly disputed and fought over with neighbouring Azerbaijan whom considered these regions to be of tantamount importance.

The Olti Okrug (the western half of which was controlled by Turco-Kurdish militias since the Ottoman withdrawal) was claimed by Armenia, as a constituent county of the larger Kars Oblast, however, they were unable to establish full control over it. The overwhelmingly ethnic Armenian Lori uchastok was disputed and jointly administered with Georgia following the conclusion of the 2-week-war over the region and the establishment of the Lori Neutral Zone. South of the capital of the republic, centered in Davalu and Zangibasar, local Azerbaijanis openly rebelled against the Armenian government during the Muslim uprisings of July 1919.

Following the disestablishment of the Aras Republic and Armenia's consolidation of Nakhichevan, acting prime minister Khatisian in Julfa wired salutations to Persian Prime Minister Vosuq ed-Dowleh, who replied by extolling the traditional bonds between Armenia and Persia and welcoming the Republic of Armenia as a neighbor.[53]

Recognition

On 19 January 1920, on account of the defeat of Denikin's Volunteer Army, the League of Nations and the Supreme Allied Council formally recognized the three Transcaucasian republics including Armenia as de facto governments over the region, in a last-ditch attempt to deter Bolshevik Russian penetration into the Transcaucasus.[54][55]

Despite the difficulties Armenia faced in consolidating its territory, after the signing of the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920, it was granted formal diplomatic de jure recognition by the Great Powers.[56] The United States, as well as several South American nations officially opened diplomatic channels with the government. Armenian diplomatic and consular missions were established in the United Kingdom, Italy, Poland, Germany, Serbia, Romania,[57] Greece, Iran, Japan and Africa.[58]

Georgian-Armenian war

In December 1918, Armenia and Georgia engaged in a brief military conflict over disputed border areas in the largely Armenian-populated Lori and Akhalkalak districts along with some other neighboring regions. Both nations claimed the districts, which Georgia had occupied after the Ottomans evacuated the area. Inconclusive fighting continued for two weeks. An Armenian offensive under Drastamat Kanayan (Dro) made substantial gains in the first ten days. By 25 December Armenian troops had reached positions 50 kilometres (30 miles) from Tiflis (which had a plurality of Armenian population back then), when the Allied representatives in the city intervened.[59][60] On 1 January 1919, military operations of both sides ceased and peace talks began supervised by the British and French, which ended in Tbilisi a few days later.[60][61] The draft British plan established that Georgian troops would remain in Akhalkalak and northern Borchaly, whereas Armenian forces would settle in southern Borchaly, and the British would take positions between the two opponents. This forced Armenia to relinquish its wartime gains in the region, including the copper mines of Alaverdi. Georgia accepted the plan and the Allies decided to impose it with or without the approval of the government of Armenia. Finally, hostilities ceased on 31 December when the parties agreed to the British-brokered ceasefire. British mediation facilitated the end of the war, and resulted in the establishment of a joint Armeno-Georgian civil administration in the "Lori Neutral Zone" or the "Shulavera Condominium".[62] Along the newly created border numerous Armenian settlements like Akhalkalak, Samshvilde, Bolnis-Khachen and Shulaver remained under Georgian control since then, while there were no Georgian settlements under Armenian control.

Tense diplomacy

Relations between Armenia and Georgia despite the conclusion of peace remained tense.[63] In the spring of 1919, ARA (American Relief Agency) officials began to complain that Georgian officials, who demanded a share of the provisions, were holding up railway traffic carrying vital supplies of flour and other foodstuffs to Armenia.[64] Moved by their complaints and the debilitating food crisis in Armenia, Georges Clemenceau, as president of the Versailles Conference, issued a carefully worded protest letter on 18 July, calling on "the authorities in Georgia" to cease further interference. Georgia issued its own protest to this communiqué, however, by 25 July American officials were already reporting that the rail traffic had begun to pick up.[65]

In autumn 1919, the two countries began negotiations for a new transit treaty which was concluded on 3. In addition to this, the parties also concluded an arbitration treaty whereby they agreed to settle their territorial disputes. The treaties were acclaimed by the liberal and socialist press in both countries. To blunt conservative criticism, the Menshevik Bor'ba newspaper remarked that the transit treaty would give Georgia access to the markets of Persia and would yield a lucrative income in transportation fees. All Georgian political observers agreed, however, that the immediate benefits would favour Armenia and that the Armenian government should reciprocate with a conciliatory attitude on other issues.

Territorial disputes

A considerable degree of hostility existed between Armenia and its new neighbor to the east, the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan, stemming largely from racial, religious, cultural and societal differences. The Azeris had close ethnic and religious ties to the Turks and had provided material support for them in their drive to Baku in 1918. Although the borders of the two countries were still undefined, Azerbaijan claimed most of the territory Armenia was sitting on, demanding all or most parts of the former Russian provinces of Elizavetpol, Tiflis, Yerevan, Kars and Batum.[66] As diplomacy failed to accomplish compromise, even with the mediation of the commanders of a British expeditionary force that had installed itself in the Caucasus, territorial clashes between Armenia and Azerbaijan took place throughout 1919 and 1920, most notably in the regions of Nakhichevan, Karabakh and Syunik (Zangezur). Repeated attempts to bring these provinces under Azerbaijani jurisdiction were met with resistance by their Armenian inhabitants.[67] In May 1919, Dro led an expeditionary unit that was successful in establishing Armenian administrative control in Nakhichevan, albeit temporarily.[68]

While problems with Azerbaijan continued, a new self-proclaimed and unrecognized state headed by Fakhr al-Din Pirioghlu and centered in Kars, the South West Caucasian Republic was established. It claimed the territory around the regions of Kars and Batum, the Nakhichevan and Sharur districts of the Yerevan province and the Akhaltsikhe and Akhalkalaki districts of the Tiflis province. It existed alongside the British general governorship created during the Entente's intervention in Transcaucasia.[69] It was abolished by British High Commissioner Admiral Somerset Arthur Gough-Calthorpe in April 1919 and the entire Kars region was assigned to the Armenian Republic.[70]

Battle for Karabakh

The largest escalation of the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict occurred in mid-March 1920 during the botched Karabakh uprising culminating in the massacre and expulsion of Shusha's majority Armenian population.[71] Through 1918–1919, the area of Mountainous Karabakh was under the de facto administration of the local Armenian Karabakh Council, which was supported by the region's overwhelmingly Armenian population.[72] During this period, Azerbaijan several times attempted to assert its authority over the region, backed by the British governor of Baku, Lieutenant General Thomson, who appointed Dr. Khosrov bey Sultanov as governor-general of Karabakh and Zangezur (though Zangezur was never subjugated)[22] with the intention of bringing Karabakh under Azerbaijani subordination.[73] In 1919, under threat of extermination (demonstrated by the Khaibalikend Massacre), the Karabakh Council was forced to sign an agreement to recognise and submit to Azerbaijani jurisdiction until its status could be decided at the Paris Peace Conference.[74]

Ending early 1920, the Paris Peace Conference was inconclusive in the resolution of the Transcaucasian territorial disputes, therefore, the Armenian Republic, by this time in a much stronger position to assert itself, took it upon themselves to free the Karabakh Council from its callous Azerbaijani governor.[75] Subversive preparations began for a staged uprising in the region of the Karabakh Council, timed to coincide with Azerbaijani Novruz celebrations.[76] The uprising due to its poor coordination was unsuccessful in ousting the Azerbaijani garrisons from Shusha and neighboring Khankend, resulting in a pogrom against Shushi's majority Armenian population, in which the Azerbaijani garrison and residents burned and looted half of the city.[77]

Following the uprising, Armenian forces under the command of Garegin Nzhdeh and Dro Kanayan were dispatched by Yerevan to assist the Karabakh rebels, at the same time Azerbaijan moved most of its army westward to break the Armenian resistance and its reinforcements, despite the threat of the approaching 11th Red Army of Bolshevik Russia from the north.[78] By Azerbaijan's Sovietization barely a month after the uprising began, Azerbaijani forces were able to maintain control over the central cities of Karabakh, Shushi and Khankend, whilst its immediate surroundings were firmly in the hands of Armenian villagers supplemented by the Armenian armed forces.[79] This situation persisted until the overwhelming Bolshevik army drove out the Armenian army detachments from the region, after which the fears of the Armenians of Karabakh were alleviated by virtue of returning to the stability of Russian control.[80]

Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres was signed between the Allied and Associated Powers and Ottoman Empire at Sèvres, France on 10 August 1920. The treaty included a clause on Armenia: it made all parties signing the treaty recognize Armenia as a free and independent state. The drawing of definite borders was, however, left to President Woodrow Wilson and the United States State Department, and was only presented to Armenia on 22 November. The new borders gave Armenia access to the Black Sea and awarded large portions of the eastern provinces of the Ottoman Empire to the republic.[81]

Turkish and Soviet invasions

On 20 September 1920, the Turkish General Kazım Karabekir invaded the region of Sarikamish, in an effort to retake land lost in the Treaty of Sèvres.[82] In response, Armenia declared war on Turkey on 24 September and the Turkish–Armenian War began. In the regions of Oltu, Sarikamish, Kars, Alexandropol (Gyumri) Armenian forces clashed with those of Karabekir's XV Corps. Fearful of possible Russian support for Armenia, Mustafa Kemal Pasha had earlier sent several delegations to Moscow in search of an alliance, finding a receptive response from the Soviet government, which started sending gold and weapons to the Turkish revolutionaries. This proved disastrous for the Armenians.

The 11th Red Army began its virtually unopposed advance into Armenia on 29 November 1920. The actual transfer of power took place on 2 December in Yerevan. The Armenian leadership approved an ultimatum, presented to it by the Soviet plenipotentiary Boris Legran. Armenia decided to join the Soviet sphere, while Soviet Russia agreed to protect its remaining territory from the advancing Turkish army. The Soviets also pledged to take steps to rebuild the army, protect the Armenians and to not pursue non-communist Armenians. The final condition of this pledge was reneged on when the Dashnaks were forced out of the country following an attempted uprising.[83]

Armenia gave way to communist power in late 1920. In November 1920, the Turkish revolutionaries captured Alexandropol and were poised to move in on the capital. A ceasefire was concluded on 18 November. Negotiations were then carried out between Karabekir and a peace delegation led by Alexander Khatisian in Alexandropol; although Karabekir's terms were extremely harsh the Armenian delegation had little recourse but to agree to them. The Treaty of Alexandropol was thus signed on 3 December 1920.[84]

On 5 December, the Armenian Revolutionary Committee (Revkom, made up of mostly Armenians from Azerbaijan) also entered the city.[85] Finally, on the following day, 6 December, Felix Dzerzhinsky's Cheka entered Yerevan, thus effectively ending the existence of the First Republic of Armenia. At that point what was left of Armenia was under the influence of the Bolsheviks. The part occupied by Turkey remained for the most part theirs, as laid out in the terms of the subsequent Treaty of Kars. Soon, the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic was proclaimed, under the leadership of Aleksandr Myasnikyan. It was to be included in the newly created Transcaucasian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic.[86]

Maps

Russian occupied area of Turkish Armenia in 1917, a year before creation of the Republic and the collapse of the Russo-Armenian counter offensive.

Russian occupied area of Turkish Armenia in 1917, a year before creation of the Republic and the collapse of the Russo-Armenian counter offensive. Europe in 1912 and 1918.

Europe in 1912 and 1918. Europe in 1919.

Europe in 1919. Claims presented by the Republic of Armenia at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919.

Claims presented by the Republic of Armenia at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919.

In culture

The Sardarapat Memorial at the site of the Battle of Sardarabad is the symbol of the First Republic. Every year on May 28, Armenia's political leadership and thousands of ordinary people visit the memorial to celebrate the foundation of Armenian statehood.[87]

In his Antranik of Armenia short story, Armenian-American writer William Saroyan writes about the First Republic of Armenia. "It was a small nation of course, a very unimportant nation, surrounded on all sides by enemies, but for two years Armenia was Armenia, and the capital was Erivan. For the first time in thousands of years Armenia was Armenia."[88]

See also

- Aftermath of World War I

- Armenian genocide

- Democratic Republic of Georgia

- Azerbaijan Democratic Republic

- Kars Oblast

- United Armenia

- Wilsonian Armenia

Notes

- Other names of the country include Araratian Republic[10] (Արարատյան հանրապետություն, Republic of Ararat or Ararat Republic)[11][12] and Republic of Erivan/Yerevan[13] or Erivan/Yerevan Republic.[14] These terms were often used by Ottoman Armenians because the country "was only a dusty province without Ottoman Armenia whose salvation Armenians had been seeking for 40 years."[15] It has also been known as the Dashnak Republic due to the fact that the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, better known as Dashnaktsutyun or simply Dashnak was the dominant political force in the country.[16] During the Soviet era, the Communist-influenced Armenian academic circles, namely the Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia, referred to it as the Bourgeois Republic of Armenia (Հայաստանի Բուրժուական Հանրապետություն).[17] Since Armenia's independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, the most commonly used term in Armenia is the First Republic of Armenia (Հայաստանի Առաջին Հանրապետություն), or the First Republic for short.[18]

- Sources vary on when Armenian statehood was lost. The Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia in ceased to exist in 1375.[19] However, others suggest that Armenian statehood was lost in 1045 with the fall of Bagratid Armenia, because Cilician Armenia was outside of the traditional Armenian homeland, while Bagratid Armenia was the last major Armenian state in the Armenian Highlands.[20][21]

- Includes Azerbaijanis, Karapapakhs, and Turks.

- Known before 1905 as the Jebrail Uyezd.

References

- Specific sources

- Hewsen, Robert (2001). Armenia: A Historical Atlas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 235. ISBN 0-226-33228-4.

- Walker, Christopher J. (1990). Armenia: The Survival of a Nation (revised second ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 257. ISBN 9780312042301.

- Maintenance of Peace in Armenia. United States Congress. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. USA: Govt. print. off. 1919. p. 119. Retrieved 2011-02-14.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Chiclet, Christophe (2005). "The Armenian Genocide" in Turkey Today: A European Country? Olivier Roy (ed.) London: Anthem Press. p. 167. ISBN 1-84331-173-9.

- Hakobyan, Tatul (9 August 2015). "Sèvres: The Unfulfilled Armenian Dream". ANI Armenian Research Center. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

If the Treaty of Sèvres had been realised, the Republic of Armenia would have covered a territory of over 160 thousand square kilometres.

- Hewsen, Robert (2001). Armenia: A Historical Atlas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 235. ISBN 0-226-33228-4.

- Walker, Christopher J. (1990). Armenia: The Survival of a Nation (revised second ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 257. ISBN 9780312042301.

- Chiclet, Christophe (2005). "The Armenian Genocide" in Turkey Today: A European Country? Olivier Roy (ed.) London: Anthem Press. p. 167. ISBN 1-84331-173-9.

-

- "Division of Armenology and Social Sciences". Armenian National Academy of Sciences.

...the political history of the First Republic of Armenia...

- Libaridian, Gerald J. (2007). Modern Armenia: people, nation, state. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. p. 266. ISBN 978-1-4128-0648-0.

...two most important and consequential events for Armenians in the twentieth century: the Genocide and the experience of the First Republic of Armenia, 1918-1920.

- Avakian, Arra S. (1998). "The First Republic of Armenia (1918-1920)". Armenia: A Journey Through History: Van. Electric Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-916919-24-5.

- Danielyan, Eduard (2003). "Armenia". In Mokyr, Joel (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Economic History, Volume 2. Oxford University Press. p. 157.

The first Republic of Armenia (1918–1920) suffered a difficult time, sheltering thousands of refugees while enduring epidemics and Turkish invasions...

- Mirzoyan, Alla (2010). Armenia, the Regional Powers, and the West: Between History and Geopolitics. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 13. ISBN 9780230106352.

For instance, the contemporary celebration of the independence day of the First Republic of Armenia on May 28 accomplishes the mental integration of 1918 and 1991 into an uninterrupted experience of independence...

- de Waal, Thomas (2003). Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-8147-1945-9.

From 1918 to 1920, Yerevan was the capital of the briefly independent first republic of Armenia...

- "The Birth of the First Republic of Armenia". civilnet.am. CivilNet. 28 May 2013.

- "Richard Hovannisian to Discuss First Republic of Armenia at Lecture in Belmont". The Armenian Weekly. 3 November 2015.

- "Division of Armenology and Social Sciences". Armenian National Academy of Sciences.

- Hovannisian 1971, p. 259.

- Pasdermadjian, Garegin; Torossian, Aram (1918). Why Armenia should be free: Armenia's role in the present war, Issue 30. Hairenik Publishing. p. 37.

- Hovannisian 1971, p. 454.

- Chisholm, Hugh (1922). The Encyclopædia Britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, literature and general information, Volume 32. The Encyclopædia Britannica Co. p. 802.

- Walker, Christopher J. (1980). Armenia, the survival of a nation. Croom Helm. p. 231.

- Walker, Christopher J. (1990). Armenia: The Survival of a Nation (revised second ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 272–273. ISBN 9780312042301.

- Suny 1993, p. 131.

- Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia (in Armenian). Vol. 6. Yerevan. 1980. pp. 137–138.

- "Նախկին վարչապետներ [Previous Prime Ministers]" (in Armenian). Government of Armenia Website. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- de Waal, Thomas (2010). The Caucasus: An Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 28. ISBN 9780199746200.

- Nazaryan, Lousine (28 May 2009). "Historian Ashot Melkonyan: "The idea of unity of the Armenian nation must not be buried in oblivion"". Hayastani Hanrapetutyun. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- "Declaration of Independence (May 30, 1918)". ARF Archives Institute. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- Hovannisian 1971, pp. 88–89.

- Armenia: A Historical Atlas, by Robert H. Hewsen and Christoper C. Salvatico, 2001

- Hovannisian 1967, pp. 80–82.

- Hovannisian 1967, pp. 75–80.

- Hovannisian 1967, p. 104.

- Hovannisian 1967, p. 106.

- Hovannisian 1967, pp. 103–105, 130.

- Balakian. Burning Tigris, pp. 319-323.

- Lang, David Marshall (1962). A Modern History of Georgia. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, pp. 207-208.

- Hovannisian 1967, pp. 186–201.

- Hovannisian 1967, p. 191.

- Hovannisian 1967, p. 198.

- Badalyan, Lena (18 May 2018). "Women's Suffrage: The Armenian Formula". chai-khana.org. Tbilisi, Georgia: Chai Khana. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- Grigoris Palakʻean (2009). Armenian Golgotha: A Memoir of the Armenian Genocide, 1915-1918. Vintage Books. pp. 446, 447. ISBN 978-1-4000-9677-0.

- Hovannisian 1967, p. 197.

- International Encyclopedia of the First World War: Armenia

- "New Republics in the Caucasus: Armenia, Azerbaidjan, and Georgia: Their Mutual Relations and Their Present Status". Current History. University of California Press. 11 (3): 496. 1920. JSTOR 45325199 – via JSTOR.

- "Gains of the Turkish Nationalists: Armenia's Hopes Crushed by Kemal—Complicated Situation in Syria—Progress in Palestine". Current History. Gains of the Turkish Nationalists: Armenia's Hopes Crushed by Kemal. 13 (1): 67. 1921. JSTOR 45329058 – via JSTOR.

- "Հայաստանի նահանգների նոր բաժանումը 1920-ին. Արարատ, Շիրակ, Վանանդ, Սյունիք" [The new division of the states of Armenia in 1920. Ararat, Shirak, Vanand, Syunik]. Aniarc. 18 June 2020. Retrieved 2022-09-13.

- Hakobyan, Tatul (3 January 2019). "Հայաստանի վարչական բաժանումները 1918-1922 թվականներին" [Administrative divisions of Armenia in 1918-1922]. CIVILNET (in Armenian). Retrieved 2022-09-13.

- Кавказский календарь на 1917 год [Caucasian calendar for 1917] (in Russian) (72nd ed.). Tiflis: Tipografiya kantselyarii Ye.I.V. na Kavkaze, kazenny dom. 1917. pp. 178–237. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021.

- Albert Parsadanyan. Intelligence Warehouse-1. Yerevan: VMV Publication, 2003, p. 57.

- Hewsen. Armenia, p. 235.

- See the US State Department values given here.

- Hovannisian 1967, p. 236.

- texte, Conférence de la paix (1919 / 1920 ; Paris) Auteur du; texte, Arménie Délégation à la conférence de la paix (1919) Auteur du (1920). La République arménienne / Délégation de la République arménienne à la Conférence de la paix.

- RG 256, 184.021/216.

- File:République_arménienne_(1919),_tableau_d'ensemble.jpg

- Hovannisian 1971, pp. 126–155.

- Hovannisian 1971, p. 128.

- Harutyunyan, Babken (2019). Atlas of the Armenian Genocide. Vardan Mkhitaryan. Erevan. ISBN 978-9939-0-2999-3. OCLC 1256558984.

- Hovannisian 1971, p. 246.

- Hille, Charlotte Mathilde Louise (2010). State building and conflict resolution in the Caucasus. Leiden: Brill. p. 143. ISBN 978-9004179011. OCLC 668211543.

- Kazemzadeh, Firuz (2008). The struggle for Transcaucasia (1917-1921) ([New ed.] ed.). London: Anglo Caspian Press. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-9560004-0-8. OCLC 303046844.

- League of Nations. Assembly. Fifth Committee (1920). Admission of new members to the League of Nations: Armenia. Report presented by the 5th Committee to the Assembly. Robarts - University of Toronto. [Geneva, League of Nations].

- "21 septembrie 1920 / O sută de ani de relații diplomatice România-Armenia". 21 September 2020.

- Hovannisian 1982, pp. 526–529.

- Partskhaladze, George; Andersen, Andrew (2015). "Armeno-Georgian War of 1918 and Armeno-Georgian Territorial Issue in the 20th Century".

- "iveria".

- Hovannisian 1971, p. 114.

- Hovannisian 1971, pp. 120–125.

- "iveria".

- Hovannisian 1982, pp. 140–144.

- Hovannisian 1982, p. 145.

- Hovannisian 1982, p. 192, map 4.

- Hakobyan, Tatul (18 September 2021). "1918-1920. Հայաստանը եւ Ադրբեջանը բաժանում են Զանգեզուրը" [1918-1920. Armenia and Azerbaijan divide Zangezur]. Aliq Media Armenia. Retrieved 2022-09-13.

- Hovannisian 1971, pp. 243–247.

- Hovannisian 1971, pp. 205–214.

- Hovannisian 1971, p. 327.

- Hovannisian 1971, p. 152.

- Hovannisian 1971, p. 83.

- Swietochowski, Tadeusz (1995). Russia and Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition. New York. p. 76.

- Sbornik dokumentov i materialov (1992). Nagorny Karabakh 1918—1923. Yerevan. pp. 323–326.

- Hovannisian 1971, pp. 134–142.

- Hovannisian 1971, pp. 134–142 and 147–150.

- Hovannisian 1971, pp. 149–150.

- Leeuw, Charles van der (2000). Azerbaijan : a quest for identity, a short history. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 120. ISBN 0-312-21903-2. OCLC 39538940.

- Kazemzadeh, Firuz (2008). The struggle for Transcaucasia (1917-1921) ([New ed.] ed.). London: Anglo Caspian Press. p. 274. ISBN 978-0-9560004-0-8. OCLC 303046844.

- Kadishev, A.B. (1961). Interventsia I Grazhdanskaja Vojna v Zakavkazje. Moscow. pp. 196–200.

- Hovannisian 1996, pp. 40–44.

- Hovannisian 1996, pp. 184–197.

- Suny 1993, p. 140.

- Hovannisian 1996, pp. 394–396.

- Hovannisian 1996, p. 373.

- Suny 1993, p. 141.

- Hakobyan, Tatul (28 May 2009). "On Armenian independence day, a visit to Sardarapat, symbol of Armenian pride". Armenian Reporter. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- Saroyan, William (1943). 31 selected stories from "Inhale and Exhale". New York: Avon Book Company. p. 107.

- General sources

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1967). Armenia on the Road to Independence, 1918. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-00574-0.

- Hovannisian, Richard G., The Republic of Armenia:

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1971). The Republic of Armenia, Vol. I: The first year, 1918-1919. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520018051.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1982). The Republic of Armenia, Vol. II: From Versailles to London, 1919-1920. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04186-0.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1996). The Republic of Armenia, Vol. IV: Between Crescent and Sickle, Partition and Sovietization. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-08804-2.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (1993). Looking toward Ararat Armenia in modern history. Bloomington: Indiana university press. ISBN 9780253207739.

Further reading

- (in Armenian) Aghayan, Tsatur P. Հոկտեմբերը և Հայ Ժողովրդի Ազատագրական Պայքարը (October and the Liberation Struggle of the Armenian People). Yerevan: Yerevan State University Press, 1982.

- Barton, James L. Story of Near East Relief, (1915-1930). New York: Macmillan, 1930.

- Egan, Eleanor Franklin. "This To Be Said For The Turk." Saturday Evening Post, 192, December 20, 1919.

- Gidney, James B. A Mandate for Armenia. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1967.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. The Republic of Armenia. 4 volumes. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971–1996.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. Armenia on the Road to Independence, 1918. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967.

- Kazemzadeh, Firuz. The Struggle for Transcaucasia, 1917-1921. New York, Oxford: Philosophical Library, 1951.

- (in Armenian) Khatisian, Alexander. Հայաստանի Հանրապետութեան Ծագումն ու Զարգացումը (The Birth and Development of the Armenian Republic). Athens: Nor Or Publishing, 1930.

- (in French) Ter Minassian, Anahide. La République d’Arménie: 1918-1920. Bruxelles: Editions Complexe, 1989.

- (in Armenian) Vratsian, Simon. Հայաստանի Հանրապետութիւն (The Republic of Armenia). Paris: H.H.D. Amerikayi Publishing, 1928.

- (in Russian) Makhmourian, Gayane G. Armenia in the U.S. Politics of 1917-1923 (Армения в политике США 1917-1923 гг.). Yerevan: Institute of History, National Academy of Sciences, 2018.

- (in Russian) Makhmourian, Gayane G. The Policy of Great Britain in Armenia and Transcaucasia in 1918-1920. White Man's Burden (Политика Великобритании в Армении и Закавказье в 1918-1920 гг. Бремя белого человека). Yerevan: Institute of History, National Academy of Sciences, Lousakn Publishing, 2002.

- (in Russian) Makhmourian, Gayane G. The League of Nations, the Armenian Question and the Republic of Armenia (Лига Наций, Армянский вопрос и Республика Армения). Yerevan: Institute of History, National Academy of Sciences, Artagers Publishing, 1999.

- (in Russian) Armenia in Documents of the U.S. Department of State 1917-1920 (Армения в документах Государственного департамента США 1917-1920 гг.). comp. and trans. from English by Gayane Makhmourian. Yerevan: Institute of History, National Academy of Sciences, 2012.