Göktürks

The Göktürks, Celestial Turks or Blue Turks (Old Turkic: 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰:𐰉𐰆𐰑𐰣, romanized: Türük Bodun; Chinese: 突厥; pinyin: Tūjué; Wade–Giles: T'u-chüeh) were a nomadic confederation of Turkic peoples in medieval Inner Asia. The Göktürks, under the leadership of Bumin Qaghan (d. 552) and his sons, succeeded the Rouran Khaganate as the main power in the region and established the First Turkic Khaganate, one of several nomadic dynasties that would shape the future geolocation, culture, and dominant beliefs of Turkic peoples.

𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰:𐰉𐰆𐰑𐰣 Türük Bodun | |

|---|---|

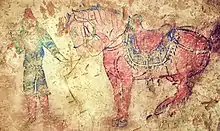

Göktürk petroglyphs from modern Mongolia (6th to 8th century).[1] | |

| Total population | |

| Ancestral to some Turkic populations | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Central and Eastern Asia | |

| Languages | |

| Old Turkic Middle Chinese[2] | |

| Religion | |

| Tengrism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Türgesh, Toquz Oghuz, Xueyantuo, Shatuo[3] |

Etymology

._After_679_in_the_style_of_the_Nezak_Huns.jpg.webp)

Strictly speaking, the common name "Göktürk" emerged from the misreading of the word "Kök" meaning Ashina, ruling clan of the historical ethnic group's endonym: which was attested as Old Turkic: 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰, romanized: Türük[4][5] Old Turkic: 𐰛𐰇𐰜⁚𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰, romanized: Kök Türük,[4][5] or Old Turkic: 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰚, romanized: Türk.[6] They were known in Middle Chinese historical sources as the Tūjué (Chinese: 突厥; reconstructed in Middle Chinese as romanized: *dwət-kuɑt > tɦut-kyat).[7] According to Chinese sources, Tūjué meant "combat helmet" (Chinese: 兜鍪; pinyin: Dōumóu; Wade–Giles: Tou1-mou2), reportedly because the shape of the Altai Mountains, where they lived, was similar to a combat helmet.[8][9][10] Róna-Tas (1991) pointed to a Khotanese-Saka word, tturakä "lid", semantically stretchable to "helmet", as a possible source for this folk etymology, yet Golden thinks this connection requires more data.[11]

It is generally accepted that the name Türk is ultimately derived from the Old-Turkic migration-term[12] 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰 Türük/Törük, which means 'created, born'.[13]

Göktürk means "Celestial Turk",[14] or sometimes "Blue Turk" (i.e. because sky blue is associated with celestial realms). This is consistent with "the cult of heavenly ordained rule" which was a recurrent element of Altaic political culture and as such may have been imbibed by the Göktürks from their predecessors in Mongolia.[15] The name of the ruling Ashina clan may derive from the Khotanese Saka term for "deep blue", āššɪna.[16]

The ethnonym was also recorded in various other Middle Asian languages, such as Sogdian *Türkit ~ Türküt, tr'wkt, trwkt, turkt > trwkc, trukč; Khotanese Saka Ttūrka/Ttrūka, Ruanruan to̤ro̤x/türǖg and Old Tibetan Drugu.[7][17]

According to the American Heritage Dictionary the word Türk meant "strong" in Old Turkic;[18] though Gerhard Doerfer supports this theory, Gerard Clauson points out that "the word Türk is never used in the generalized sense of 'strong'" and that the noun Türk originally meant "'the culminating point of maturity' (of a fruit, human being, etc.), but more often used as an [adjective] meaning (of a fruit) 'just fully ripe'; (of a human being) 'in the prime of life, young, and vigorous'".[19]

Origins

.jpg.webp)

The Göktürk rulers originated from the Ashina clan, who were first attested to in 439. The Book of Sui reports that in that year, on October 18, the Tuoba ruler Emperor Taiwu of Northern Wei overthrew Juqu Mujian of the Northern Liang in eastern Gansu,[20][21][22] whence 500 Ashina families fled northwest to the Rouran Khaganate in the vicinity of Gaochang.[9][23]

According to the Book of Zhou and History of the Northern Dynasties, the Ashina clan was a component of the Xiongnu confederation,[8][10] specifically, the Northern Xiongnu tribes[24][25] or southern Xiongnu "who settled along the northern Chinese frontier", according to Edwin G. Pulleyblank.[26] However, this view is contested.[23] Göktürks were also posited as having originated from an obscure Suo state (索國) (MC: *sâk) which was situated north of the Xiongnu and had been founded by the Sakas.[8][10][27] According to the Book of Sui and the Tongdian, they were "mixed Hu (barbarians)" (雜胡) from Pingliang (平涼), now in Gansu, Northwest China.[9][28] Pointing to the Ashina's association with the Northern tribes of the Xiongnu, some researchers (e.g. Duan, Lung, etc.) proposed that Göktürks belonged in particular to the Tiele confederation, likewise Xiongnu-associated,[9] by ancestral lineage.[29][30] However, Lee and Kuang (2017) state that Chinese sources do not describe the Ashina-led Göktürks as descending from the Dingling or beloning to the Tiele confederation.[31]

Chinese sources linked the Hu on their northern borders to the Xiongnu just as Graeco-Roman historiographers called the Pannonian Avars, Huns and Hungarians “Scythians". Such archaizing was a common literary topos, implying similar geographic origins and nomadic lifestyle but not direct filiation.[32]

As part of the heterogeneous Rouran Khaganate, the Turks lived for generations north of the Altai Mountains, where they 'engaged in metal working for the Rouran'.[9][33] According to Denis Sinor, the rise to power of the Ashina clan represented an 'internal revolution' in the Rouran Khaganate rather than an external conquest.[34]

According to Charles Holcombe, the early Turk population was rather heterogeneous and many of the names of Turk rulers, including the two founding members, are not even Turkic.[35] This is supported by evidence from the Orkhon inscriptions, which include several non-Turkic lexemes, possibly representing Uralic or Yeniseian words.[36][37] Peter Benjamin Golden points out that the khaghans of the Turkic Khaganate, the Ashina, who were of an undetermined ethnic origin, adopted Iranian and Tokharian (or non-Altaic) titles, he also adds that this hypothesis assumes that they were not themselves lranian or Tokharian in speech.[38] German Turkologist W.-E. Scharlipp points out that many common terms in Turkic are Iranian in origin.[39] Whatever language the Ashina may have spoken originally, they and those they ruled would all speak Turkic, in a variety of dialects, and create, in a broadly defined sense, a common culture.[38][40]

Expansion

The Göktürks reached their peak in late 6th century and began to invade the Sui Dynasty of China. However, the war ended due to the division of Turkic nobles and their civil war for the throne of Khagan. With the support of Emperor Wen of Sui, Yami Qaghan won the competition. However, the Göktürk empire was divided to Eastern and Western empires. Weakened by the civil war, Yami Qaghan declared allegiance to Sui Dynasty.[41] When Sui began to decline, Shibi Khagan began to assault its territory and even surrounded Emperor Yang of Sui in Siege of Yanmen (615 AD) with 100,000 cavalry troops. After the collapse of Sui dynasty, the Göktürks intervened in the ensuing Chinese civil wars, providing support to the northeastern rebel Liu Heita against the rising Tang in 622 and 623. Liu enjoyed a long string of success but was finally routed by Li Shimin and other Tang generals and executed. The Tang dynasty was then established.

Conquest by the Tang

Although the Göktürk Khaganate once provided support to the Tang Dynasty in the early period of the civil war during the collapse of the Sui dynasty, the conflicts between the Göktürks and Tang finally broke out when Tang was gradually reunifying China proper. The Göktürks began to attack and raid the northern border of the Tang Empire and once marched their main force to Chang'an, the capital of Tang. Having not recovered from the civil war, the Tang briefly had to pay tribute to Göktürk nobles.[45] Allied with tribes opposing the Göktürk Khaganate, the Tang defeated the main force of Göktürk army in Battle of Yinshan four years later and captured Illig Qaghan in 630 AD.[46] With the submission of the Turkic tribes, the Tang conquered the Mongolian Plateau.

After a vigorous court debate, Emperor Taizong decided to pardon the Göktürk nobles and offered them positions as imperial guards.[45] However, the proposition was ended by a plan for the assassination of the emperor. On May 19, 639[47] Ashina Jiesheshuai and his tribesmen directly assaulted Emperor Taizong of Tang at Jiucheng Palace (九成宮, in present-day Linyou County, Baoji, Shaanxi). However, they did not succeed and fled to the north, but were caught by pursuers near the Wei River and were killed. Ashina Hexiangu was exiled to Lingbiao.[48] After the unsuccessful raid of Ashina Jiesheshuai, on August 13, 639[49] Taizong installed Qilibi Khan and ordered the settled Turkic people to follow him north of the Yellow River to settle between the Great Wall of China and the Gobi Desert.[50] However, many Göktürk generals still remained loyal in service to the Tang Empire.

In 679, Ashide Wenfu and Ashide Fengzhi, who were Turkic leaders of the Chanyu Protectorate (單于大都護府), declared Ashina Nishufu as qaghan and revolted against the Tang dynasty.[51] In 680, Pei Xingjian defeated Ashina Nishufu and his army. Ashina Nishufu was killed by his men.[51] Ashide Wenfu made Ashina Funian a qaghan and again revolted against the Tang dynasty.[51] Ashide Wenfu and Ashina Funian surrendered to Pei Xingjian. On December 5, 681[52] 54 Göktürks, including Ashide Wenfu and Ashina Funian, were publicly executed in the Eastern Market of Chang'an.[51] In 682, Ilterish Qaghan and Tonyukuk revolted and occupied Heisha Castle (northwest of present-day Hohhot, Inner Mongolia) with the remnants of Ashina Funian's men.[53] The restored Göktürk Khaganate intervened in the war between Tang and Khitan tribes.[54] However, after the death of Bilge Qaghan, the Göktürks could no longer subjugate other Turk tribes in the grasslands. In 744, allied with Tang Dynasty, the Uyghur Khaganate defeated the last Göktürk Khaganate and controlled the Mongolian Plateau.[55]

Genetics

A genetic study published in Nature in May 2018 examined the remains of four elite Türk soldiers buried between ca. 300 AD and 700 AD.[56] The extracted samples of Y-DNA belonged to haplogroup Q (sample DA86),[57] haplogroup R1 (samples DA89,[57] DA224) and Haplogroup O (sample DA228[58]).[59] The extracted samples of mtDNA belonged to C4b1 (sample DA86), A14(samples DA89), H2a (samples DA224) and A15c (sample DA228).[60] The examined Türks were found to have more East Asian ancestry than the preceding Tian Shan Huns. Evidence of European ancestry was also detected, suggesting ongoing contacts with Europe. Succeeding Turkic states of Central Asia displayed even higher levels of East Asian ancestry, indicating that the Turkification of Central Asia was carried out by dominant minorities of East Asian origin.[61][62]

See also

- Göktürk family tree

- Horses in East Asian warfare

- Khazars

- Timeline of the Turkic peoples (500–1300)

- Silver Deer of Bilge Khan

In popular culture

- Kürşat, fictional character based on Göktürk prince Ashina Jiesheshuai

- Göktürk-1, Göktürk-2, Göktürk-3 satellites named after Göktürks

- Gokturk exoplanet named after Gökturks

References

- Altınkılıç, Arzu Emel (2020). "Göktürk giyim kuşamının plastik sanatlarda değerlendirilmesi" (PDF). Journal of Social and Humanities Sciences Research: 1101–1110.

- Ma, Lirong (2014). "Sino-Turkish Cultural Ties under the Framework of Silk Road Strategy". Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies (In Asia). 8 (2): 44–65. doi:10.1080/19370679.2014.12023242. S2CID 158969735.

- Xiu Ouyang, (1073), Historical Records of the Five Dynasties, p. 39

- Kultegin's Memorial Complex, Türik Bitig Orkhon inscriptions

- Bilge Kagan's Memorial Complex, Türik Bitig

- Tonyukuk's Memorial Complex, Türik Bitig Bain Tsokto inscriptions

- Golden 2011, p. 20.

- Linghu Defen et al., Book of Zhou, Vol. 50. (in Chinese)

- Wei Zheng et al., Book of Sui, Vol. 84. (in Chinese)

- Li Yanshou (李延寿), History of the Northern Dynasties, Vol. 99. (in Chinese)

- Golden, Peter B. "Türks and Iranians: Aspects of Türk and Khazaro-Iranian Interaction". Turcologica (105): 25.

- (Bŭlgarska akademii︠a︡ na naukite. Otdelenie za ezikoznanie/ izkustvoznanie/ literatura, Linguistique balkanique, Vol. 27–28, 1984, p. 17

- Faruk Sümer, Oghuzes (Turkmens): History, Tribal organization, Sagas, Turkish World Research Foundation, 1992, p. 16)

- Marshall Cavendish Corporation 2006, p. 545.

- Wink 64.

- Findley 2004, p. 39.

- Golden 2018, p. 292.

- American Heritage Dictionary (2000). "The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition – "Turk"". bartleby.com. Archived from the original on 2007-01-16. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- Clauson, G. (1972). An Etymological Dictionary of Pre-13th Century Turkish. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 542–543. ISBN 0-19-864112-5.

- Wei Shou, Book of Wei, Vol. 4-I. (in Chinese)

- Sima Guang, Zizhi Tongjian, Vol. 123. (in Chinese)

- 永和七年 (太延五年) 九月丙戌 Academia Sinica (in Chinese) Archived 2013-10-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Christian 1998, p. 249.

- New Book of Tang, vol. 215 upper. "突厥阿史那氏, 蓋古匈奴北部也." "The Ashina family of the Turk probably were the northern tribes of the ancient Xiongnu." translated by Xu (2005)

- Xu Elina-Qian, Historical Development of the Pre-Dynastic Khitan, University of Helsinki, 2005

- Golden 2018, p. 306.

- Golden 2018, p. 300.

- 杜佑, 《通典》, 北京: 中華書局出版, (Du You, Tongdian, Vol.197), 辺防13 北狄4 突厥上, 1988, ISBN 7-101-00258-7, p. 5401. (in Chinese)

- Lung, Rachel (2011). Interpreters in Early Imperial China. John Benjamins. p. 48. ISBN 978-90-272-2444-6.

- Duan (1988). Dingling, Gaoju and Tiele. pp. 39–41. ISBN 7-208-00110-3.

- Lee, Joo-Yup; Kuang, Shuntu (18 October 2017). "A Comparative Analysis of Chinese Historical Sources and Y-DNA Studies with Regard to the Early and Medieval Turkic Peoples". Inner Asia. Brill. 19 (2): p. 201 of 197–239.

- Sinor 1990.

- Sima Guang, Zizhi Tongjian, Vol. 159. (in Chinese)

- Sinor 1990, p. 295.

- Holcombe 2001, p. 114.

- Sinor 1990, p. 291.

- Vovin, Alexander. "Did the Xiongnu speak a Yeniseian language?". Central Asiatic Journal 44/1 (2000), pp. 87–104.

- Golden 1992, p. 126.

- Scharlipp, Wolfgang-Ekkehard (1992). Die frühen Türken in Zentralasien. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. p. 18. ISBN 3-534-11689-5.

(...) Über die Ethnogenese dieses Stammes ist viel gerätselt worden. Auffallend ist, dass viele zentrale Begriffe iranischen Ursprungs sind. Dies betrifft fast alle Titel (...). Einige Gelehrte wollen auch die Eigenbezeichnung türk auf einen iranischen Ursprung zurückführen und ihn mit dem Wort "Turan", der persischen Bezeichnung für das Land jeneseits des Oxus, in Verbindung bringen.

- Lev Gumilyov, (1967), Drevnie Turki (Ancient Turks), p. 22-25

- Wei 魏, Zheng 徵 (656). Book of Sui 隋書 Vol. 2 Vol. 51 & Vol.84.

- Narantsatsral, D. "THE SILK ROAD CULTURE AND ANCIENT TURKISH WALL PAINTED TOMB" (PDF). The Journal of International Civilization Studies.

- Cosmo, Nicola Di; Maas, Michael (26 April 2018). Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity: Rome, China, Iran, and the Steppe, ca. 250–750. Cambridge University Press. pp. 350–354. ISBN 978-1-108-54810-6.

- Baumer, Christoph (18 April 2018). History of Central Asia, The: 4-volume set. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 185–186. ISBN 978-1-83860-868-2.

- Liu 劉, Xu 昫 (945). Old Book of Tang 舊唐書 Vol.2 & Vol.194.

- Liu 劉, Xu 昫 (945). Old book of Tang 舊唐書 Vol.2 & Vol. 67.

- 貞觀十三年 四月戊寅 Academia Sinica Archived 2010-05-22 at the Wayback Machine (in Chinese)

- Sima Guang, Zizhi Tongjian, Vol. 195. (in Chinese)

- 貞觀十三年 七月庚戌 Academia Sinica Archived 2010-05-22 at the Wayback Machine (in Chinese)

- Ouyang Xiu et al., New Book of Tang, Vol. 215-I.

- Sima Guang, Zizhi Tongjian, Vol. 202 (in Chinese)

- 開耀元年 十月乙酉 Academia Sinica Archived 2010-05-22 at the Wayback Machine (in Chinese)

- Sima Guang, Zizhi Tongjian, Vol. 203 (in Chinese)

- Liu 劉, Xu 昫 (945). Old Book of Tang 舊唐書 Vol. 6 & Vol.194.

- Liu 劉, Xu 昫 (945). Old Book of Tang 舊唐書 Vol.103,Vol.194 & Vol.195.

- Damgaard et al. 2018, Supplementary Table 2, Rows 60, 62, 127, 130.

- "Haplotree Information Project - Ancient DNA". haplotree.info. Retrieved 2021-03-08. Map based on public dataset on www.haplogroup.info by Carlos Quiles (www.indo-european.eu).

- "Haplotree.info - Ancient DNA. Map based on All Ancient DNA v. 2.06.03". haplotree.info. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- Damgaard et al. 2018, Supplementary Table 9, Rows 44, 87, 88.

- Damgaard et al. 2018, Supplementary Table 8, Rows 128, 130, 70, 73.

- Damgaard et al. 2018, pp. 4–5. "We find evidence that elite soldiers associated with the Turkic Khaganate are genetically closer to East Asians... These results suggest that Turkic cultural customs were imposed by an East Asian minority elite onto central steppe nomad populations... The wide distribution of the Turkic languages from Northwest China, Mongolia and Siberia in the east to Turkey and Bulgaria in the west implies large-scale migrations out of the homeland in Mongolia... [T]he genomic history of the Eurasian steppes is the story of a gradual transition from Bronze Age pastoralists of West Eurasian ancestry towards mounted warriors of increased East Asian ancestry..."

- Damgaard et al. 2018, Supplementary Information, p. 12.

Sources

- Christian, David (1998). A history of Russia, Central Asia and Mongolia, Vol. 1: Inner Eurasia from prehistory to the Mongol Empire. Blackwell.

- Findley, Carter Vaughn (2004). The Turks in World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-988425-4.

- Damgaard, P. B.; et al. (May 9, 2018). "137 ancient human genomes from across the Eurasian steppes". Nature. Nature Research. 557 (7705): 369–373. Bibcode:2018Natur.557..369D. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0094-2. PMID 29743675. S2CID 13670282. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- Golden, Peter (1992). An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples: Ethnogenesis and State-Formation in Medieval and Early Modern Eurasia and the Middle East. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. ISBN 9783447032742.

- Golden, Peter B. (August 2018). "The Ethnogonic Tales of the Türks". The Medieval History Journal. 21 (2): 291–327. doi:10.1177/0971945818775373. S2CID 166026934.

- Golden, Peter Benjamin (2011). "Ethnogenesis in the tribal zone: The Shaping of the Turks". Studies on the peoples and cultures of the Eurasian steppes. București: Ed. Acad. Române. ISBN 978-973-1871-96-7.

- Great Soviet Encyclopaedia, 3rd ed. Article "Turkic Khaganate" (online Archived 2005-05-16 at the Wayback Machine).

- Grousset, René. The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press, 1970. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- Gumilev, Lev (2007) (in Russian) The Göktürks (Древние тюрки ;Drevnie ti︠u︡rki). Moscow: AST, 2007. ISBN 5-17-024793-1.

- Skaff, Jonathan Karem (2009). Nicola Di Cosmo (ed.). Military Culture in Imperial China. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03109-8.

- Yu. Zuev (I︠U︡. A. Zuev) (2002) (in Russian), "Early Türks: Essays on history and ideology" (Rannie ti︠u︡rki: ocherki istorii i ideologii), Almaty, Daik-Press, p. 233, ISBN 9985-4-4152-9

- Wechsler, Howard J. (1979). "T'ai-Tsung (Reign 626–49): The Consolidator". In Denis Twitchett; John Fairbank (eds.). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 3: Sui and T'ang China Part I. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-21446-9.

- Wink, André. Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World. Brill Academic Publishers, 2002. ISBN 0-391-04173-8.

- Zhu, Xueyuan (朱学渊) (2004) (in Chinese) The Origins of the Ethnic Groups of Northern China (中国北方诸族的源流). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju (中华书局) ISBN 7-101-03336-9

- Xue, Zongzheng (薛宗正) (1992) (in Chinese) A History of the Turks (突厥史). Beijing: Chinese Social Sciences Press (中国社会科学出版社) ISBN 7-5004-0432-8

- Nechaeva, Ekaterina (2011). "The "Runaway" Avars and Late Antique Diplomacy". In Ralph W. Mathisen, Danuta Shanzer (ed.). Romans, Barbarians, and the Transformation of the Roman World: Cultural Interaction and the Creation of Identity in Late Antiquity. Ashgate. pp. 175–181. ISBN 9780754668145.

- Sinor, Denis (1990). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24304-9.