Güyük Khan

Güyük (also Güyug;[note 2] c. March 19, 1206 – April 20, 1248) was the third Khagan-Emperor[note 1] of the Mongol Empire, the eldest son of Ögedei Khan and a grandson of Genghis Khan. He reigned from 1246 to 1248.

| |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3rd Khagan-Emperor of the Mongol Empire (Supreme Khan of the Mongols) King of Kings Emperor of the Yuan dynasty (posthumously) | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| 3rd Khagan-Emperor of the Mongol Empire[note 1] | |||||||||||||

| Reign | 24 August 1246 – 20 April 1248 | ||||||||||||

| Coronation | 24 August 1246 | ||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Ögedei Khagan Töregene (as regent) | ||||||||||||

| Successor | Möngke Khan | ||||||||||||

| Born | 19 March 1206 Khamag Mongol | ||||||||||||

| Died | 20 April 1248 (aged 42) Qum-Senggir, Xinjiang, Mongol Empire | ||||||||||||

| Spouse | Oghul Qaimish | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| House | Borjigin | ||||||||||||

| Father | Ögedei Khan | ||||||||||||

| Mother | Töregene | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Tengrism | ||||||||||||

Appearance

According to Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, Güyük was of "medium stature, very prudent and extremely shrewd, and serious and sedate in his manners."[2]

Early life

Güyük received military training and served as an officer under his grandfather Genghis Khan and later his father Ögedei Khan (after the death of Genghis in 1227). He married Oghul Qaimish of the Merkit clan. In 1233, Güyük, along with his maternal cousin Alchidai and the Mongol general Tangghud, conquered the short-lived Dongxia Kingdom of Puxian Wannu, who was a rebellious Jin official,[3] in a few months. After the death of Güyük's uncle Tolui, Ögedei proposed that Sorghaghtani, the widow of Tolui, marry his son Güyük. Sorghaghtani declined, saying that her prime responsibility was to her own sons.[4]

Güyük participated in the invasion of Eastern and Central Europe in 1236–1241 with other Mongol princes, including his cousin Batu and half-brother Kadan. He led his corps in the Siege of Ryazan and the lengthy siege of the Alanian capital Maghas. During the course of the conquest, Güyük quarreled violently with Batu at the victory banquet and screamed at him, "Batu is just an old woman with a quiver".[5][6] Güyük and Büri, a grandson of Chagatai, stormed out of the banquet and rode away swearing and cursing. When word reached the Great Khan, they were recalled for a time to Mongolia. Ögedei refused to see them and threatened to have his son Güyük executed. Ögedei calmed down and finally admitted Güyük into his ger. Ögedei criticized Güyük, "Do you think that the Russians surrendered because how mean you were to your own men. ...Because you captured one or two warriors, you think that you won the war. But you didn't capture even a single kid goat." Ögedei reprimanded his son harshly for fighting within the family and for mistreating his soldiers. Güyük was dispatched again to Europe.

In the meantime, Ögedei had died (in 1241), and his widow Töregene had taken over as regent, a position of great influence and authority that she used to advocate for her son Güyük. Batu withdrew from Europe so that he might have some influence over the succession, but despite his delaying tactics, Töregene succeeded in getting Güyük elected Khan in 1246. When Genghis Khan's youngest brother, Temüge, threatened the Great Khatun Toregene in an attempt to seize the throne, Güyük came to Mongolia from Emil to secure his position immediately.

Enthronement (1246)

Güyük's enthronement on 24 August 1246, near the Mongol capital at Karakorum, was attended by a large number of foreign ambassadors: the Franciscan friar and envoy of Pope Innocent IV, John of Plano Carpini and Benedict of Poland; Grand Duke Yaroslav II of Vladimir; the incumbents for the throne of Georgia; the brother of the king of Armenia and historian, Sempad the Constable; the future Seljuk Sultan of Rum, Kilij Arslan IV; and ambassadors of the Abbasid Caliph Al-Musta'sim and Ala ud din Masud of the Delhi Sultanate.[7] According to John of Plano Carpini, Güyük's formal election in a great kurultai, or diet of the tribes, took place while his company was at a camp called Sira Orda, or "Yellow Pavilion," along with 3,000 to 4,000 visitors from all parts of Asia and eastern Europe, bearing homage, tribute, and presents. They afterwards witnessed the formal enthronement at another camp in the vicinity called the "Golden Ordu," after which they were presented to the emperor. Mosul submitted to him, sending envoys to that assembly.

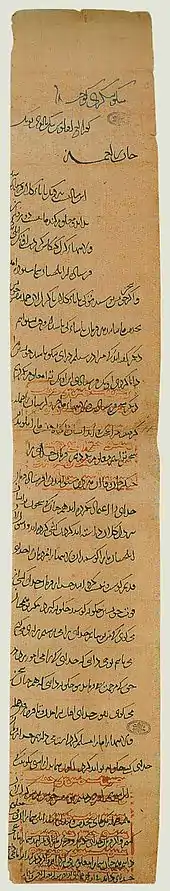

When the papal envoy John of Plano Carpini protested Mongol attacks on the Catholic kingdoms of Europe, Güyük stated that these people had slain Mongol envoys in the time of Genghis Khan and Ogedei Khan. He also claimed that "from the rising of the sun to its setting, all the lands have been made subject to the Great Khan", proclaiming an explicit ideology of world conquest.[8] The Khagan wrote a letter to Pope Innocent IV on the relations between the Church and the Mongols. "You must say with a sincere heart: 'We will be your subjects; we will give you our strength'. You must in person come with your kings, all together, without exception, to render us service and pay us homage. Only then will we acknowledge your submission. And if you do not follow the order of God, and go against our orders, we will know you as our enemy."

By this time, the relationship between Güyük and Toregene had deteriorated significantly, despite Toregene's role in Güyük's accession. Against Toregene's wishes, Güyük had Toregene's favorite, Fatima, arrested, tortured and executed for bewitching his brother Koden (Khuden), and Abd-ur-Rahman was also beheaded for corruption. Of the provincial officials appointed under Toregene, only the Oirat official Arghun Aqa remained. Toregene herself died later, possibly at Güyük's orders.[9] Güyük had Temüge's case investigated by Orda Khan and Möngke, and they had him executed.[10] Güyük replaced the child khan Qara Hülëgü of the Chagatai Khanate with his favorite cousin Yesü Möngke to secure his position. He also restored his father's officials, Mahmud Yalavach, Masud Beg and Chinqai to positions in the provinces.

Reign (1246–1248)

Güyük reversed several unpopular edicts of his mother the regent and made a surprisingly capable khan, appointing Eljigidei in Persia in preparation for an attack on Baghdad and the Ismailis and pursuing the war against the Song Dynasty. He was, nevertheless, insecure and won the disapproval of his subjects by executing several high-ranking officials of the previous regime for treason. The Seljuk princes struggled incessantly for the throne of the Sultanate of Rum. Despised by Izz-ad-Din, Rukn ad-Din Kilij Arslan IV came to Mongolia. Güyük ordered Rukn ad-Din enthroned in Iz-ad-Din Kaykaus II's place. A darughachi with 2,000 Mongol troops was sent to enforce this decision. When both David Narin and David Ulu summoned before Güyük in Karakorum, he made David Ulu the senior king and divided the Kingdom of Georgia between them.[11] After the treaty signed by the Mongols and the Cilician Armenia in 1243, the king Hetoum I sent his brother Sempad to the Mongol court in Karakorum and made a formal agreement in 1247 in which Cilician Armenia would be considered a vassal state of the Mongol Empire. Due to Armenia's voluntary surrender, Sempad received a Mongol wife, and his kingdom was spared Mongol overseers and tax. Güyük demanded full-submission of the Abbasids and the Ismailis. Güyük Khan blamed Baiju for the irritated resistance of the Abbasid Caliphate.

Güyük ordered an empire-wide census. In 1246, by the decree of Güyük, taxes amounting between 1⁄30 to 1⁄10 of value were imposed on everything and a heavy head tax of 60 silver drams was collected from males in Georgia and Armenia.[12] The Great Khan separated the position of the great darughachi from that of chief scribe. Güyük took half of his father's kheshig for himself. Under his rule, the Uyghur officials increased their dominance, sidelining the North Chinese and the Muslims. Güyük was a strict and intelligent person, though rather morose and sickly, and his bad drinking habit worsened his health.

Güyük sent Amuqan to Korea and the Mongols camped near Yiom-ju in July 1247. After the king Gojong of Goryeo refused to move his capital from Ganghwa Island to Songdo, Amuqan's force pillaged the Korean Peninsula until 1250.

Although Batu did not support Güyük's election, he respected the Great Khan as a traditionalist and sent Andrey and Alexander Nevsky to Karakorum in Mongolia in 1247 after their father's death. Güyük appointed Andrey Grand prince of Vladimir-Suzdal and Alexander prince of Kiev.[13] In 1248, he demanded Batu come towards Mongolia to meet him, a move that some contemporaries regarded as a pretext for Batu's arrest. In compliance with the order, Batu approached bringing a large army. When Güyük moved westwards, Sorghaghtani warned Batu that the Jochids might be his target.

The showdown never happened – Güyük died en route, in modern-day Qinghe County, Xinjiang, China. Güyük might have been poisoned, but some modern historians believe that he died of natural causes because his health deteriorated.[14] According to William of Rubruck he was killed in a violent brawl with Shiban. His widow Oghul Qaimish took over as regent, but she would be unable to keep the succession within her branch of the family. Möngke succeeded as Khan in 1251.

Wives, concubines, and children

It was common for powerful Mongol men to have many wives and concubines, but it is unknown how many wives or concubines Güyük had.[15][16]

- Primary Consort Wuwuerheimishi (元妃乌兀儿黑迷失), of the Merkit tribe (蔑兒乞氏)

- Empress Naimanzhen (乃蠻真皇后), of the Namaizhen tribe (乃蠻真氏)

- Empress Qinshu (欽淑皇后, d.1251), of the Merkit tribe (蔑兒乞氏)

- Khoja (忽察), first son

- Naqu (腦忽), second son

- Unknown wife or concubine:

- Khokhoo, third son

- Babahaer (公主 巴巴哈尔), first daughter

- Yelimishi (赵国公主 叶里迷失), second daughter

Legacy

The death of Güyük had a profound effect on world history. Güyük wanted to turn the Mongol power against Europe, but his premature death prevented Mongol forces from trying to move further west into Europe. Subsequent to Güyük's death, Mongol family politics caused the Mongol efforts to be instead directed against southern China, which was eventually conquered during the rule of Kublai Khan.

When Kublai Khan established the Yuan Dynasty in 1271, he had Güyük Khan placed on the official record as Dingzong (Chinese: 定宗).

Notes

- Decades before Kublai Khan announced the dynastic name "Great Yuan" in 1271, Khagans (Great Khans) of the "Great Mongol State" (Yeke Mongγol Ulus) already started to use the Chinese title of Emperor (Chinese: 皇帝; pinyin: Huángdì) practically in the Chinese language since Spring 1206 in the First Year of the reign of Genghis Khan (as 成吉思皇帝; 'Genghis Emperor'[1]).

- Mongolian script: ᠭᠦᠶᠦᠭgüyüg qaγan; Mongolian: Гүюг, romanized: Güyug; Chinese: 貴由; pinyin: Guìyóu

References

Citations

- "太祖本纪 [Chronicle of Taizu]". 《元史》 [History of Yuan] (in Classical Chinese).

元年丙寅,帝大会诸王群臣,建九斿白旗,即皇帝位于斡难河之源,诸王群臣共上尊号曰成吉思皇帝["Genghis Huangdi"]。

- Rockhill 1967.

- Nyíri, Pál (2007). Chinese in Eastern Europe and Russia. London: Routledge. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-415-54106-0.

- Man, John (2007). Kublai Khan. London: Bantam Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-553-81718-8.

- Christian, David (1998). Inner Eurasia from Prehistory to the Mongol Empire. Oxford: Blackwell. p. 412. ISBN 0-631-18321-3.

- Weatherford, Jack (2004). Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World. New York: Crown. p. 162. ISBN 0-609-61062-7.

- Roux, Jean-Paul (2003). L'Asie Centrale. Paris: Fayard. p. 312. ISBN 2-213-59894-0.

- Jolly, Karen Louise (1996). Tradition and Diversity : Christianity in a World Context to 1500. London: M. E. Sharpe. p. 459. ISBN 1-56324-468-3.

- Weatherford, Jack (2011). The Secret History of the Mongol Queens. New York: Broadway. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-0-307-40716-0.

- Weatherford, Jack (2004). Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World. New York: Crown. p. 165. ISBN 0-609-61062-7.

- ("Maurē Thalassa") # (Birmingham, M. # 1978). p. 256.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (2004). The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 259. ISBN 1-4039-6421-1.

- Martin, Janet (2011). Medieval Russia, 980–1584. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-521-67636-6.

- Atwood, C. P. (2004). Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. New York. p. 213. ISBN 0-8160-4671-9.

- McLynn, Frank (2015-07-14). Genghis Khan: His Conquests, His Empire, His Legacy. Hachette Books. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-306-82395-4.

- Broadbridge, Anne F. (2018-07-18). Women and the Making of the Mongol Empire. Cambridge University Press. pp. 74, 92. ISBN 978-1-108-63662-9.

Sources

- Jean-Paul Roux, L'Asie Centrale, Paris, 1997, ISBN 978-2-213-59894-9.

- Rockhill, William Woodville (1967), The Journey of William of Rubruck to The Eastern Parts of the World, 1253-55, As Narrated by Himself, With Two Accounts of the Earlier Journey of John of Pian de Carpine.

External links

- Plano Carpini's account of the Mongols

- Catholic Encyclopedia, "The Crusades" Archived 2014-02-01 at the Wayback Machine