Punjab, Pakistan

Punjab (Punjabi and Urdu: پنجاب, Panjāb) is one of the four provinces of Pakistan. Located in centraleastern region, Punjab is the second-largest province of Pakistan by land area and the largest province by population. It shares land borders with the Pakistani provinces of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to the north-west, Balochistan to the south-west and Sindh to the south, as well as Islamabad Capital Territory to the north-west, Autonomous Territory of AJK to the north and International border with the Indian states of Rajasthan and Punjab to the east and Indian-administered Kashmir to the north-east. Punjab is the most fertile province of the country as River Indus and it's four major tributaries Ravi, Jhelum, Chenab and Sutlej flow through it.

Punjab

پنجاب | |

|---|---|

Province of Pakistan | |

Counter-clockwise from top: Badshahi Mosque, Noor Mahal, Derawar Fort, Khewra Salt Mine, Faisalabad Clock Tower, Tomb of Shah Rukn-e-Alam | |

Flag  Seal | |

.svg.png.webp) Location of Punjab within Pakistan | |

| Coordinates: 31°N 72°E | |

| Country | |

| Established | 1 July 1970 |

| Capital and largest city | Lahore |

| Government | |

| • Type | Self-governing Province subject to the Federal Government |

| • Body | Government of Punjab |

| • Governor | Muhammad Baligh-ur-Rehman |

| • Chief Minister | Chaudhry Pervaiz Elahi |

| • Chief Secretary | Kamran Ali Afzal |

| • Legislature | Provincial Assembly |

| • High Court | Lahore High Court |

| Area | |

| • Total | 205,344 km2 (79,284 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 2nd, Pakistan |

| Population (2017)[1] | |

| • Total | 110,012,442 |

| • Rank | 1st, Pakistan |

| • Density | 540/km2 (1,400/sq mi) |

| GDP (nominal)(2021–22;est.) | |

| • Total | Rs.54.68 trillion (USD$230 billion) |

| • Per Capita | ₨.494,769.05 (USD$4,081) |

| GDP (PPP)(2021–22;est.) | |

| • Total | Rs.184 trillion (USD$778 billion) |

| • Per Capita | ₨.1.68 million (USD$9,073) |

| Time zone | UTC+05:00 (PKT) |

| ISO 3166 code | PK-PB |

| Main language(s) | |

| Provincial sports teams | List:

|

| HDI (2021) | 0.564 (medium) |

| Literacy rate (2020) | 66.3%[3] |

| National Assembly seats | 183 |

| Provincial Assembly seats | 371[4] |

| Divisions | 10 |

| Districts | 41 |

| Tehsils | 146 |

| Union councils | 7602 |

| Website | punjab |

Forming the bulk of the transnational Punjab region between Pakistan and India, it is bounded locally by Sindh to the south, Balochistan to the west, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to the northwest, the Islamabad Capital Territory to the north, and the Pakistani-administered territory of Azad Jammu and Kashmir to the northeast. On its eastern side, it is bounded by the India–Pakistan border, sharing an international boundary with the Indian states of Punjab and Rajasthan to the east and southeast, respectively, and a disputed boundary with the Indian-administered territory of Jammu and Kashmir to the northeast. The province's capital is Lahore—a cultural, modern, historical, economic, and cosmopolitan centre of Pakistan. Other major cities include Faisalabad, Rawalpindi, Gujranwala, Multan, and Sialkot. Punjab is also the world's fifth-most populous subnational entity, and the most populous outside of China and India.

Modern-day Pakistani Punjab has been inhabited since ancient times; the Indus Valley civilization, dating to 3300 BCE, was first discovered at Harappa.[5] It features heavily in the Sanskrit-language Indian epic known as the Mahabharata, and is also home to Taxila, the site of what is considered by many scholars to be the oldest university in the world.[6][7][8][9][10]

Multan was the ancient capital and cultural centre of the region, it was conquered by Alexander the Great after a fierce battle.[11] In 326 BCE, Alexander the Great defeated the ancient Indian king Porus in the Battle of the Hydaspes near Mong. Subsequently, Punjab formed part of the Maurya Empire, the Kushan Empire, and the Gupta Empire.

In the 7th century, the region saw its first wave of Arab conquests, which introduced Islam; by the 8th century, when Muhammad bin Qasim conquered the key city of Multan.[11]

The Umayyad Caliphate had largely conquered Punjab. Arabs ruled the Punjab region for next 3 centuries with their capital in Multan.[11] In the subsequent centuries, the region was conquered by various dynasties, including the Hindu Shahis, the Ghaznavids, the Ghurids, the Delhi Sultanate, the Mughal Empire, the Afghan Empire, and the Sikh Empire.

Multan remained the medieval capital of Punjab up till start of 17th century.[12] During the 18th century, an Iranian invasion of Mughal-ruled India under Iranian ruler Nader Shah caused Mughal authority in Punjab to collapse. Later, the region was conquered by the Afghans under Ahmad Shah Durrani; the Afghan Empire eventually lost control of Punjab as a result of the Afghan–Sikh Wars. In 1799, the Sikh Empire was formally established under the rule of Ranjit Singh with its capital based in Lahore, and Punjab remained under Sikh rule until the arrival of the British Empire. The region was central to the independence movements of Pakistan and India, with Lahore being the site of both the Declaration of Indian Independence as well as the Lahore Resolution that called for the establishment of a separate state for Indian Muslims. The modern-day Pakistani province has its roots in the Punjab Province of British India, which was divided along religious boundaries by the Radcliffe Line during the partition of India in 1947.[13]

Punjab is Pakistan's most industrialized province, with the industrial sector comprising 24 percent of the province's gross domestic product.[14] It is known across Pakistan for its relative prosperity,[15] and has the lowest rate of poverty among all Pakistani provinces.[16][17] However, a clear divide is present between the northern and southern portions of the province;[15] with poverty rates in northern Punjab being among the lowest in Pakistan,[18] while some in southern Punjab are among the most impoverished.[19] Punjab is also one of the most urbanized regions of South Asia, with approximately 40 percent of its population being concentrated in urban areas.[20]

It has been strongly influenced by Sufism, with numerous Sufi shrines spread across the province, attracting millions of devotees annually.[21] Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism, was born in the town of Nankana Sahib, near Lahore.[22][23][24] Punjab is also the site of the Katas Raj Temples, which feature prominently in Hindu mythology.[25] Several of the World Heritage Sites listed by UNESCO are located in Punjab, including the Shalimar Gardens, the Lahore Fort, the archaeological excavations at Taxila, and the Rohtas Fort, among others.[26]

Etymology

Though the name Punjab is of Persian origin, its two parts (پنج, panj, 'five' and آب, āb, 'water') are cognates of the Sanskrit words, पञ्च, pañca, 'five' and अप्, áp, 'water', of the same meaning.[27][28] The word pañjāb thus means 'The Land of Five Waters', referring to the rivers Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Sutlej, and Beas.[29] All are tributaries of the Indus River, the Sutlej being the largest. References to a land of five rivers may be found in the Mahabharata, which calls one of the regions in ancient Bharat Panchanada (Sanskrit: पञ्चनद, romanized: pañca-nada, lit. 'five rivers').[30][31] Persian place names are very common in Northwest India and Pakistan. The ancient Greeks referred to the region as Pentapotamía (Greek: Πενταποταμία),[32][33][34] which has the same meaning as the Persian word.

History

Ancient period

The Punjab region is noted as the site of one of the earliest urban societies, the Indus Valley Civilization that flourished from about 3000 B.C. and declined rapidly 1,000 years later, following the Indo-Aryan migrations that overran the region in waves between 1500 and 500 B.C.[35] Frequent intertribal wars stimulated the growth of larger groupings ruled by chieftains and kings, who ruled local kingdoms known as Mahajanapadas.[35] The rise of kingdoms and dynasties in the Punjab is chronicled in the ancient Hindu epics, particularly the Mahabharata.[35]

Multan was the noted centre of excellence of the region which was attacked by Greek army led by Alexander. The Mali tribe together with nearby tribes gathered an army of 90,000 personnel to face Greek army. This was the largest army faced by Greeks in entire subcontinent.[11] During the siege of the city's citadel, the Alexander leaped into the inner area of the citadel, where he killed the Mallians' leader. Alexander was wounded by an arrow that had penetrated his lung, leaving him severely injured. The city was conquered after a fierce battle.[11][36]

In 326 B.C. The earliest known notable local king of this region was known as King Porus, who fought the famous Battle of the Hydaspes against Alexander the Great. His kingdom spanned between rivers Hydaspes (Jhelum) and Acesines (Chenab); Strabo had held the territory to contain almost 300 cities.[37] He (alongside Abisares) had a hostile relationship with the Kingdom of Taxila which was ruled by his extended family.[37] When the armies of Alexander crossed Indus in its eastward migration, probably in Udabhandapura, he was greeted by the-then ruler of Taxila, Omphis.[37] Omphis had hoped to force both Porus and Abisares into submission leveraging the might of Alexander's forces and diplomatic missions were mounted, but while Abisares accepted the submission, Porus refused.[37] This led Alexander to seek for a face-off with Porus.[37] Thus began the Battle of the Hydaspes in 326 BC; the exact site remains unknown.[37] The battle is thought to be resulted in a decisive Greek victory; however, A. B. Bosworth warns against an uncritical reading of Greek sources who were obviously exaggerative.[37] Alexander later founded two cities—Nicaea at the site of victory and Bucephalous at the battle-ground, in memory of his horse, who died soon after the battle.[37][lower-alpha 1] Later, tetradrachms would be minted depicting Alexander on horseback, armed with a sarissa and attacking a pair of Indians on an elephant.[37][38] Porus refused to surrender and wandered about atop an elephant, until he was wounded and his force routed.[37] When asked by Alexander how he wished to be treated, Porus replied "Treat me as a king would treat another king".[39] Despite the apparently one-sided results, Alexander was impressed by Porus and chose to not depose him.[40][41][42] Not only was his territory reinstated but also expanded with Alexander's forces annexing the territories of Glausaes, who ruled to the northeast of Porus' kingdom.[40] After Alexander's death in 323 BCE, Perdiccas became the regent of his empire, and after Perdiccas's murder in 321 BCE, Antipater became the new regent.[43] According to Diodorus, Antipater recognized Porus's authority over the territories along the Indus River. However, Eudemus, who had served as Alexander's satrap in the Punjab region, treacherously killed Porus.[44] The battle is historically significant because it resulted in the syncretism of ancient Greek political and cultural influences to the Indian subcontinent, yielding works such as Greco-Buddhist art, which continued to have an impact for the ensuing centuries. The region was then divided between the Maurya Empire and the Greco-Bactrian kingdom in 302 B.C.E. Menander I Soter conquered Punjab and made Sagala (present-day Sialkot) the capital of the Indo-Greek Kingdom.[45][46] Menander is noted for having become a patron and convert to Greco-Buddhism and he is widely regarded as the greatest of the Indo-Greek kings.[47] Greek influence in the region ended around 12 B.C.E. when the Punjab fell under the Sassanids.

Medieval period

Islam emerged as the major power in southern Punjab after the Umayyad caliphate conquered the region in 711 AD.[35] The city of Multan became a center of the Ismaili sect of Islam. Umayyads after conquering key cities of Uch and Multan inhabited thousands of Arabs in Multan, These Arabs ruled the vast areas of Punjab for next 3 centuries. From their capital in Multan they ruled the far areas of Kashmir. Islam spread rapidly.[11][48]

In the ninth century, the Hindu Shahi dynasty emerged in the Punjab, ruling much of Punjab and eastern Afghanistan.[35] Lahore emerged as an important city of Central Punjab in late 10th century. It was ruled by Arabs of Amirate of Multan and then by Hindu Shahi Empire.[48] The 10th century Arab historian Masudi mentioned that in his time the kings of Gandhara were all called Hajaj, J.haj or Ch'hach, while the area itself was called "country of the Rahbūt" (Rajputs).[49] The character transliterated to "Hahaj" and Alexander Cunningham had it equated to the Janjua tribe/clan.[50] Rahman doubts this theory and instead transliterates to "J.haj", an Arabicised form of Chhachh, which is even today the name of the region around the Hindu Shahi capital of Hund.[50] In the 10th century, this region was occupied by the tribe of the Gakhars/Khokhars, who formed a large part of the Hindu Shahi army according to the Persian historian Firishta.[50]

Ghaznavid rule

The Turkic Ghaznavids in the tenth century attacked the regions of Punjab. Multan and Uch were conquered after 3 attacks and Multan's Arab ruler Abul Fateh Daud was defeated, thousands of Hindus and Ismailis were killed according to 11th century scholar Abu Mansur al-Baghdadi, though the community was not extinguished,[52] famous Sun Temple was destroyed. This ended the 3 centuries Arab rule over Punjab.[11] Ghaznavids overthrew the Hindu Shahis and consequently ruled for 157 years, gradually declining as a power until the Ghurid conquests of key Punjab cities of Uch, Multan and Lahore by Muhammad of Ghor in 1186, deposing the last Ghaznavid ruler Khusrau Malik.[11][53]

Following the death of Muhammad of Ghor in 1206, the Ghurid state fragmented and was replaced in northern India by the Delhi Sultanate and for some time independent sultanates ruled by various Sultans.[11] The Delhi Sultanate ruled the Punjab for the next three hundred years, led by five unrelated dynasties, the Mamluks, Khalajis, Tughlaqs, Sayyids and Lodis.

Tughlaqs rule

Ghiyath al Din Tughlaq, the former governor of Multan and Dipalpur founded Tughlaq dynasty in Delhi and ruled the subcontinent region . Earlier he was the governor of Multan and fought 28 battles against Mongols from there and saved Punjab and Sindh regions from advances of Mongols and had survived. After his death his son Muhammad Tughlaq became the emperor.[11]

Mongol invasion

15th century saw rise of many prominent Muslims from Punjab. Khizr Khan established the Sayyid dynasty, the fourth dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate after the fall of the Tughlaqs.[54]

Mongols led by Timur attacked the Punjab region. Multan's governor Khizr Khan allied with Timur for Mongols rule in subcontinent. Timur also captured Lahore and gave its control to Khizr Khan. Together they sacked Delhi sultanate and Timur gave Khizr Khan the throne of subcontinent. Who ruled on the name of Timur.[11] Khizr Khan established Sayyid Dynasty which ruled the subcontinent from 1414-1451.[55] A contemporary writer Yahya Sirhindi mentions in his Takhrikh-i-Mubarak Shahi that Khizr Khan was a descendant of prophet Muhammad.[56] Members of the dynasty derived their title, Sayyid, or the descendants of the Islamic prophet, Muhammad, based on the claim that they belonged to his lineage through his daughter Fatima. However, Yahya Sirhindi based his conclusions on unsubstantial evidence, the first being a casual recognition by the famous saint Sayyid Jalaluddin Bukhari of Uch Sharif of his Sayyid heritage,[57] and secondly the noble character of the Sultan which distinguished him as a Prophet's descendant.[58]

According to Richard M. Eaton, Khizr Khan was son of a Punjabi chieftain.[54] He was a Khokhar chieftain who travelled to Samarkand and profited from the contacts he made with the Timurid society[60] Later on, Delhi Sultanate, weakened by invasion of Emir Timur, could not control all regions of the Empire and different local kingdoms appeared. In 1407, Sultan Muzaffar Shah I, a Tank Rajput[61] or a Khatri[62] Muslim from Punjab[59] established the Gujarat Sultanate.

In 1445, Sultan Qutbudin, chief of Langah, a Jat Zamindar tribe[63][64][65][66] established the Langah Sultanate in Multan. The Sultanate included regions of southern and central Punjab and areas of Khyber and Balochistan. A large number of Baloch settlers arrived and towns of Dera Ghazi Khan and Dera Ismail Khan were founded.[67]

Another prominent name is that of Jasrath Khokhar who helped Sultan Zain Ul Abideen of Kashmir to gain his throne and ruled over vast tracts of Jammu and North Punjab. He also conquered Delhi for a brief period in 1431 but was driven out by Mubarak Shah.[68]

Modern period

During Mughal period Punjab region was divided into two provinces; Multan province and Lahore province. Multan province consisted of southern Punjab and few regions of central Punjab, parts of Khyber and Balochistan areas , bordering Kandahar province and Persian Safavid Empire. Lahore province included parts of central and northern Punjab and the Indian Punjab region, bordering Delhi and Kashmir provinces.[69]

The Mughals came to power in the early sixteenth century and gradually expanded to control all of the Punjab from their various capitals.[69] During the Mughal era, Saadullah Khan, born into a family of Jat agriculturalists[70] belonging to the Thaheem tribe[71] from Chiniot[72] remained Grand vizier (or Prime Minister) of the Mughal empire in the period 1645-1656.[72] Lahore served as Mughal capital for many years. Other capitals included Delhi, Fatehpur, Agra and Kabul etc.[69] Other prominent Muslims from Punjab who rose to nobility during the Mughal Era include Wazir Khan,[73] Adina Beg Arain,[74] and Shahbaz Khan Kamboh.[75]

The Mughal Empire ruled the region until it was severely weakened in the eighteenth century.[35] As Mughal power weakened, Afghan rulers took control of the region.[35] Contested by Marathas and Afghans, the region was the center of the growing influence of the Sikhs, who expanded and established the Sikh empire as the Mughals and Afghans weakened, ultimately ruling the Punjab, eastern Afghanistan, and territories north into the Himalayas.[35]

The Sikh Empire ruled the Punjab until the British annexed it in 1849 following the First and Second Anglo-Sikh Wars.[76]

British Rule

Most of the Punjabi homeland formed a province of British India, though a number of small princely states retained local rulers who recognized British authority.[35] The Punjab with its rich farmlands became one of the most important colonial assets.[35] Lahore was a noted center of learning and culture, and Rawalpindi became an important military installation.[35] Multan remained an important settlement and Bahawalpur had emerged as another important city.[77]

Most Punjabis supported the British during World War I, providing men and resources to the war effort even though the Punjab remained a source of anti colonial activities.[78] Disturbances in the region increased as the war continued.[35] At the end of the war, high casualty rates, heavy taxation, inflation, and a widespread influenza epidemic disrupted Punjabi society.[35] In 1919 a British officer ordered his troops to fire on a crowd of demonstrators, mostly Sikhs in Amritsar. The Jallianwala massacre fueled the indian independence movement.[35] Nationalists declared the independence of India from Lahore in 1930 but were quickly suppressed.[35]

When the Second World War broke out, nationalism in British India had already divided into religious movements.[35] Many Sikhs and other minorities supported the Hindus, who promised a secular multicultural and multireligious society, and Muslim leaders in Lahore passed a resolution to work for a Muslim Pakistan, making the Punjab region a center of growing conflict between Indian and Pakistani nationalists.[35] At the end of the war, the British granted separate independence to India and Pakistan, setting off massive communal violence as Muslims fled to Pakistan and Hindu and Sikh Punjabis fled east to India.[35]

The British Raj had major political, cultural, philosophical, and literary consequences in the Punjab, including the establishment of a new system of education. During the independence movement, many Punjabis played a significant role, including Madan Lal Dhingra, Sukhdev Thapar, Ajit Singh Sandhu, Bhagat Singh, Udham Singh, Kartar Singh Sarabha, Bhai Parmanand, Choudhry Rahmat Ali, and Lala Lajpat Rai. At the time of partition in 1947, the province was split into East and West Punjab. East Punjab (48%) became part of India, while West Punjab (52%) became part of Pakistan.[79] The Punjab bore the brunt of the civil unrest following partition, with casualties estimated to be in the millions.[80][81][82][83]

Another major consequence of partition was the sudden shift towards religious homogeneity occurred in all districts across Punjab owing to the new international border that cut through the province. This rapid demographic shift was primarily due to wide scale migration but also caused by large-scale religious cleansing riots which were witnessed across the region at the time. According to historical demographer Tim Dyson, in the eastern regions of Punjab that ultimately became Indian Punjab following independence, districts that were 66% Hindu in 1941 became 80% Hindu in 1951; those that were 20% Sikh became 50% Sikh in 1951. Conversely, in the western regions of Punjab that ultimately became Pakistani Punjab, all districts became almost exclusively Muslim by 1951.[84]

Geography

Punjab is Pakistan's second largest province by area after Balochistan with an area of 205,344 square kilometres (79,284 square miles).[85] It occupies 25.8% of the total landmass of Pakistan.[85] Punjab province is bordered by Sindh to the south, the province of Balochistan to the southwest, the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to the west, and the Islamabad Capital Territory and Azad Kashmir in the north. Punjab borders Jammu and Kashmir in the north, and the Indian states of Punjab and Rajasthan to the east.

The capital and largest city is Lahore which was the capital of the wider Punjab region since 17th century. Other important cities include Faisalabad, Rawalpindi, Gujranwala, Sargodha, Multan, Sialkot, Bahawalpur, Gujrat, Sheikhupura, Jhelum and Sahiwal. The undivided Punjab region was home to six rivers, of which five flow through Pakistan's Punjab province. From west to east, the rivers are: the Indus, Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi and Sutlej. It is the nation's only province that touches every other province; it also surrounds the federal enclave of the national capital city at Islamabad.[86][87]

Topography

Punjab's landscape consists mostly consists of fertile alluvial plains of the Indus River and its four major tributaries in Pakistan, the Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, and Sutlej rivers which traverse Punjab north to south – the fifth of the "five waters" of Punjab, the Beas River, lies exclusively in the Indian state of Punjab. The landscape is amongst the most heavily irrigated on earth and canals can be found throughout the province. Punjab also includes several mountainous regions, including the Sulaiman Mountains in the southwest part of the province, the Margalla Hills in the north near Islamabad, and the Salt Range which divides the most northerly portion of Punjab, the Pothohar Plateau, from the rest of the province. Sparse deserts can be found in southern Punjab near the border with Rajasthan and near the Sulaiman Range. Punjab also contains part of the Thal and Cholistan deserts. In the South, Punjab's elevation reaches 2,327 metres (7,635 ft) near the hill station of Fort Munro in Dera Ghazi Khan.

Climate

Most areas in Punjab experience extreme weather with foggy winters, often accompanied by rain. By mid-February the temperature begins to rise; springtime weather continues until mid-April, when the summer heat sets in. The onset of the southwest monsoon is anticipated to reach Punjab by May, but since the early 1970s, the weather pattern has been irregular. The spring monsoon has either skipped over the area or has caused it to rain so hard that floods have resulted. June and July are oppressively hot. Although official estimates rarely place the temperature above 46 °C, newspaper sources claim that it reaches 51 °C and regularly carry reports about people who have succumbed to the heat. Heat records were broken in Multan in June 1993, when the mercury was reported to have risen to 54 °C. In August the oppressive heat is punctuated by the rainy season, referred to as barsat, which brings relief in its wake. The hardest part of the summer is then over, but cooler weather does not come until late October.

Recently the province experienced one of the coldest winters in the last 70 years.[88]

Punjab's region temperature ranges from −2° to 45 °C, but can reach 50 °C (122 °F) in summer and can touch down to −10 °C in winter.

Climatically, Punjab has three major seasons:[89]

- Hot weather (April to June) when temperature rises as high as 123 °F (51 °C).

- Rainy season (July to September). Average rainfall annual ranges between 96 cm sub-mountain region and 46 cm in the plains.

- Cold / Foggy / mild weather (October to March). Temperature goes down as low as 35.6 °F (2.0 °C).

Weather extremes are notable from the hot and barren south to the cool hills of the north. The foothills of the Himalayas are found in the extreme north as well, and feature a much cooler and wetter climate, with snowfall common at higher altitudes.

Demographics

| Historical population figures[90][91][lower-alpha 2] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Population | Urban | Rural |

|

| |||

| 1941 | 17,309,857 | N/A | N/A |

| 1951 | 20,540,762 | 3,568,076 | 16,972,686 |

| 1961 | 25,463,974 | 5,475,922 | 19,988,052 |

| 1972 | 37,607,423 | 9,182,695 | 28,424,728 |

| 1981 | 47,292,441 | 13,051,646 | 34,240,795 |

| 1998 | 73,621,290 | 23,019,025 | 50,602,265 |

| 2017 | 110,012,615 | 40,401,164 | 70,008,451 |

Population

The province is home to over half the population of Pakistan, and is the world's fifth-most populous subnational entity, and the most populous outside China or India. Punjab has the lowest poverty rates in Pakistan, although a divide is present between the northern and southern parts of the province.[15] Sialkot District in the prosperous northern part of the province has a poverty rate of 5.63%,[92] while Rajanpur District in the poorer south has a poverty rate of 60.05%.[19]

Languages

The major native language spoken in the Punjab is Punjabi, representing the largest language spoken in the country. Punjabi is recognized as the provincial language of Punjab but is not given any official recognition in the Constitution of Pakistan at the national level.

Several languages closely related to Punjabi are spoken in the periphery of the region. In the southern half of Punjab, the majority language is Saraiki, while in the north there are speakers of Hindko and Pothwari.[94] Pashto is also spoken in some parts of Punjab, especially in Attock, Mianwali and Rawalpindi districts.[95]

The use of Urdu and English as the near exclusive languages of broadcasting, the public sector, and formal education have led some to fear that Punjabi in Pakistan is being relegated to a low-status language and that it is being denied an environment where it can flourish. Several prominent educational leaders, researchers, and social commentators have echoed the opinion that the intentional promotion of Urdu and the continued denial of any official sanction or recognition of the Punjabi language amounts to a process of "Urdu-isation" that is detrimental to the health of the Punjabi language[96][97][98] In August 2015, the Pakistan Academy of Letters, International Writer's Council (IWC) and World Punjabi Congress (WPC) organised the Khawaja Farid Conference and demanded that a Punjabi-language university should be established in Lahore and that Punjabi language should be declared as the medium of instruction at the primary level.[99][100] In September 2015, a case was filed in Supreme Court of Pakistan against Government of Punjab, Pakistan as it did not take any step to implement the Punjabi language in the province.[101][102] Additionally, several thousand Punjabis gather in Lahore every year on International Mother Language Day.

Hafiz Saeed, chief of Jama'at-ud-Da'wah (JuD) has questioned Pakistan's decision to adopt Urdu as its national language in a country where majority of people speak Punjabi language, citing his interpretation of Islamic doctrine as encouraging education in the mother-tongue.[103] The list of thinktanks, political organisations, cultural projects, and individuals that demand authorities at the national and provincial level to promote the use of the language in the public and official spheres includes:

- Cultural and research institutes: Punjabi Adabi Board, the Khoj Garh Research Centre, Punjabi Prachar, Institute for Peace and Secular Studies, Adbi Sangat, Khaaksaar Tehreek, Saanjh, Maan Boli Research Centre, Punjabi Sangat Pakistan, Punjabi Markaz, Sver International

- Trade unions and youth groups: Punjabi Writers Forum, National Students Federation, Punjabi Union-Pakistan, Punjabi National Conference, National Youth Forum, Punjabi Writers Forum, National Students Federation, Punjabi Union, Pakistan, and the Punjabi National Conference.

- Notable activists include Tariq Jatala, Farhad Iqbal, Diep Saeeda, Khalil Ojla, Afzal Sahir, Jamil Ahmad Paul, Mazhar Tirmazi, Mushtaq Sufi, Biya Je, Tohid Ahmad Chattha and Bilal Shaker Kahaloon, Nazeer Kahut[104][105][106]

Religions

| Religion | Population (1941)[109] |

Percentage (1941) |

Population (2017)[108] |

Percentage (2017) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islam |

12,983,076 | 75% | 107,559,164 | 97.77% |

| Hinduism |

2,376,309 | 13.73% | 220,024 | 0.2% |

| Sikhism |

1,527,345 | 8.82% | N/A | N/A |

| Christianity |

382,669 | 2.21% | 2,068,233 | 1.88% |

| Others[lower-alpha 4] | 40,458 | 0.23% | 3,455 | 0% |

| Total Population | 17,309,857 | 100% | 110,012,442 | 100% |

The Punjabi people first practiced Hinduism, the oldest recorded religion in the Punjab region.[110] The historical Vedic religion constituted the religious ideas and practices in the Punjab during the Vedic period (1500–500 BCE).[111][112][113][114] It is one of the major traditions which shaped Hinduism, though present-day Hinduism is markedly different from the historical Vedic religion.[113][115][116] The bulk of the Rigveda was composed in the Punjab region between circa 1500 and 1200 BC,[117] while later Vedic scriptures were composed more eastwards, between the Yamuna and Ganges rivers. An ancient Indian law book called the Manusmriti, developed by Brahmin Hindu priests, shaped Punjabi religious life from 200 BC onward.[118] Later, the spread of Buddhisim and Jainism in the Indian subcontinent saw the growth of Buddhism and Jainism in the Punjab.[119] Islam was introduced via southern Punjab in the 8th century, becoming the majority by the 16th century, via local conversion.[120][121] There was a small Jain community left in Punjab by the 16th century, while the Buddhist community had largely disappeared by the turn of the 10th century.[122] The region became predominantly Muslim due to missionary Sufi saints whose dargahs dot the landscape of the Punjab region.[123] The rise of Sikhism in the 1700s saw some Punjabis, both Hindu and Muslim, accepting the new Sikh faith.[118][124] A number of Punjabis during the colonial period of India became Christians, with all of these religions characterizing the religious diversity now found in the Punjab region.[118]

The population of Punjab (Pakistan) is estimated to be 110,012,442, of which as per as 2017 census, 107,559,164 i.e. (97.2%) Muslim with a Sunni Hanafi majority and a Shia Ithna 'ashariyah minority. The largest non-Muslim minority is Christians and make up 2,068,233 i.e. (2.5%) of the population. Hindus form about 220,024 people I.e (0.2%) of the population. The other minorities include Sikhs, Parsis and Baháʼís.[108]

Provincial government

The Government of Punjab is a provincial government in the federal structure of Pakistan, is based in Lahore, the capital of the Punjab Province. The Chief Minister of Punjab (CM) is elected by the Provincial Assembly of the Punjab to serve as the head of the provincial government in Punjab, Pakistan. The current Chief Minister is Chaudhry Pervaiz Elahi He got elected by the National Assembly on 26 July 2022. The Provincial Assembly of the Punjab is a unicameral legislature of elected representatives of the province of Punjab, which is located in Lahore in eastern Pakistan. The Assembly was established under Article 106 of the Constitution of Pakistan as having a total of 371 seats, with 66 seats reserved for women and eight reserved for non-Muslims.

There are 48 departments in Punjab government. Each Department is headed by a Provincial Minister (Politician) and a Provincial Secretary (A civil servant of usually BPS-20 or BPS-21). All Ministers report to the Chief Minister, who is the Chief Executive. All Secretaries report to the Chief Secretary of Punjab, who is usually a BPS-22 Civil Servant. The Chief Secretary in turn, reports to the Chief Minister. In addition to these departments, there are several Autonomous Bodies and Attached Departments that report directly to either the Secretaries or the Chief Secretary.

Divisions

_Divisions.png.webp)

| Sr. No. | Division | Headquarters | Area (km2) |

Population (2017) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bahawalpur | Bahawalpur | 45,588 | 11,464,031 |

| 2 | Dera Ghazi Khan | Dera Ghazi Khan | 38,778 | 11,014,398 |

| 3 | Faisalabad | Faisalabad | 17,917 | 14,177,081 |

| 4 | Gujranwala | Gujranwala | 8,975 | 10,616,702 |

| 5 | Lahore | Lahore | 16,104 | 19,398,081 |

| 6 | Multan | Multan | 21,137 | 12,265,161 |

| 7 | Rawalpindi | Rawalpindi | 22,255 | 10,007,821 |

| 8 | Sahiwal | Sahiwal | 10,302 | 7,380,386 |

| 9 | Sargodha | Sargodha | 26,360 | 8,181,499 |

| 10 | Gujrat | Gujrat | 8,231 | 5,507,282 |

When the divisions were restored as a tier of government in 2008, a tenth division – Sheikhupura Division – was created from part of Lahore Division.

Districts

.png.webp)

| Sr. No. | District | Headquarters | Area (km2) |

Population (2017) |

Density (people/km2) |

Division |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Attock | Attock | 6,858 | 1,883,556 | 274 | Rawalpindi |

| 2 | Bahawalnagar | Bahawalnagar | 8,878 | 2,981,919 | 335 | Bahawalpur |

| 3 | Bahawalpur | Bahawalpur | 24,830 | 3,668,106 | 147 | Bahawalpur |

| 4 | Bhakkar | Bhakkar | 8,153 | 1,650,518 | 202 | Sargodha |

| 5 | Chakwal | Chakwal | 6,524 | 1,495,982 | 229 | Rawalpindi |

| 6 | Chiniot | Chiniot | 2,643 | 1,369,740 | 518 | Faisalabad |

| 7 | Dera Ghazi Khan | Dera Ghazi Khan | 11,922 | 2,872,201 | 240 | Dera Ghazi Khan |

| 8 | Faisalabad | Faisalabad | 5,856 | 7,873,910 | 1344 | Faisalabad |

| 9 | Gujranwala | Gujranwala | 3,622 | 5,014,196 | 1384 | Gujranwala |

| 10 | Gujrat | Gujrat | 3,192 | 2,756,110 | 863 | Gujrat |

| 11 | Hafizabad | Hafizabad | 2,367 | 1,156,957 | 488 | Gujrat |

| 12 | Jhang | Jhang | 8,809 | 2,743,416 | 311 | Faisalabad |

| 13 | Jhelum | Jhelum | 3,587 | 1,222,650 | 340 | Rawalpindi |

| 14 | Kasur | Kasur | 4,796 | 3,454,996 | 720 | Lahore |

| 15 | Khanewal | Khanewal | 4,349 | 2,921,986 | 671 | Multan |

| 16 | Khushab | Khushab | 6,511 | 1,281,299 | 196 | Sargodha |

| 17 | Lahore | Lahore | 1,772 | 11,126,285 | 6278 | Lahore |

| 18 | Layyah | Layyah | 6,291 | 1,824,230 | 290 | Dera Ghazi Khan |

| 19 | Lodhran | Lodhran | 2,778 | 1,700,620 | 612 | Multan |

| 20 | Mandi Bahauddin | Mandi Bahauddin | 2,673 | 1,593,292 | 596 | Gujrat |

| 21 | Mianwali | Mianwali | 5,840 | 1,546,094 | 264 | Sargodha |

| 22 | Multan | Multan | 3,720 | 4,745,109 | 1275 | Multan |

| 23 | Muzaffargarh | Muzaffargarh | 8,249 | 4,322,009 | 523 | Dera Ghazi Khan |

| 24 | Narowal | Narowal | 2,337 | 1,709,757 | 731 | Gujranwala |

| 25 | Nankana Sahib[125] | Nankana Sahib | 2,960 | 1,356,374 | 458 | Lahore |

| 26 | Okara | Okara | 4,377 | 3,039,139 | 694 | Sahiwal |

| 27 | Pakpattan | Pakpattan | 2,724 | 1,823,687 | 669 | Sahiwal |

| 28 | Rahim Yar Khan | Rahim Yar Khan | 11,880 | 4,814,006 | 405 | Bahawalpur |

| 29 | Rajanpur | Rajanpur | 12,319 | 1,995,958 | 162 | Dera Ghazi Khan |

| 30 | Rawalpindi | Rawalpindi | 5,286 | 5,405,633 | 1322 | Rawalpindi |

| 31 | Sahiwal | Sahiwal | 3,201 | 2,517,560 | 786 | Sahiwal |

| 32 | Sargodha | Sargodha | 5,854 | 3,703,588 | 632 | Sargodha |

| 33 | Sheikhupura | Sheikhupura | 5,960 | 3,460,426 | 580 | Lahore |

| 34 | Sialkot | Sialkot | 3,016 | 3,893,672 | 1291 | Gujranwala |

| 35 | Toba Tek Singh | Toba Tek Singh | 3,252 | 2,190,015 | 673 | Faisalabad |

| 36 | Vehari | Vehari | 4,364 | 2,897,446 | 663 | Multan |

| 37 | Talagang | Talagang | 3,122 | 572,818 | 198 | Rawalpindi |

| 38 | Murree | Murree | Rawalpindi | |||

| 39 | Taunsa | Taunsa | Dera Ghazi Khan | |||

| 40 | Kot Addu | Kot Addu | Dera Ghazi Khan | |||

| 41 | Wazirabad | Wazirabad | 1,206 | 830,396 | 689 | Gujrat |

Major cities

| List of major cities in Punjab | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | City | District | Population | Image |

| 1 | Lahore | Lahore | 11,126,285 |  |

| 2 | Faisalabad | Faisalabad | 3,204,726 |  |

| 3 | Rawalpindi | Rawalpindi | 2,098,231 |  |

| 4 | Gujranwala | Gujranwala | 2,027,001 |  |

| 5 | Multan | Multan | 1,871,843 |  |

| 6 | Bahawalpur | Bahawalpur | 762,111 |  |

| 7 | Sargodha | Sargodha | 659,862 |  |

| 8 | Sialkot | Sialkot | 655,852 |  |

| 9 | Sheikhupura | Sheikhupura | 473,129 |  |

| 10 | Rahim Yar Khan | Rahim Yar Khan | 420,419 |  |

| 11 | Jhang | Jhang | 414,131 |  |

| 12 | Dera Ghazi Khan | Dera Ghazi Khan | 399,064 |  |

| 13 | Gujrat | Gujrat | 390,533 |  |

| 14 | Sahiwal | Sahiwal | 389,605 |  |

| 15 | Wah Cantonment | Rawalpindi | 380,103 | %252C_Wah_Cantt.jpg.webp) |

| Source: pbscensus 2017[126] | ||||

| This is a list of city proper populations and does not indicate metro populations. | ||||

Economy

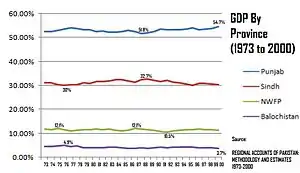

Punjab has the largest economy in Pakistan, contributing most to the national GDP. The province's economy has quadrupled since 1972.[127] Its share of Pakistan's GDP was 54.7% in 2000 and 59% as of 2010. It is especially dominant in the service and agriculture sectors of Pakistan's economy. With its contribution ranging from 52.1% to 64.5% in the Service Sector and 56.1% to 61.5% in the agriculture sector. It is also a major manpower contributor because it has the largest pool of professionals and highly skilled (technically trained) manpower in Pakistan. It is also dominant in the manufacturing sector, though the dominance is not as huge, with historical contributions ranging from a low of 44% to a high of 52.6%.[128] In 2007, Punjab achieved a growth rate of 7.8%[129] and during the period 2002–03 to 2007–08, its economy grew at a rate of between 7% to 8% per year.[130] and during 2008–09 grew at 6% against the total GDP growth of Pakistan at 4%.

Despite the lack of a coastline, Punjab is the most industrialised province of Pakistan;[14] its manufacturing industries produce textiles, sports goods, heavy machinery, electrical appliances, surgical instruments, vehicles, auto parts, metals, sugar mill plants, aircraft, cement, agricultural machinery, bicycles and rickshaws, floor coverings, and processed foods. In 2003, the province manufactured 90% of the paper and paper boards, 71% of the fertilizers, 69% of the sugar and 40% of the cement of Pakistan.[131]

Despite its tropical wet and dry climate, extensive irrigation makes it a rich agricultural region. Its canal-irrigation system established by the British is the largest in the world. Wheat and cotton are the largest crops. Other crops include rice, sugarcane, millet, corn, oilseeds, pulses, vegetables, and fruits such as kinoo. Livestock and poultry production are also important. Despite past animosities, the rural masses in Punjab's farms continue to use the Hindu calendar for planting and harvesting.

Punjab contributes about 76% to annual food grain production in the country. Cotton and rice are important crops. They are the cash crops that contribute substantially to the national exchequer. Attaining self-sufficiency in agriculture has shifted the focus of the strategies towards small and medium farming, stress on barani areas, farms-to-market roads, electrification for tube-wells and control of water logging and salinity.

Punjab has also more than 68 thousand industrial units. There are 39,033 small and cottage industrial units. The number of textile units is 14,820. The ginning industries are 6,778. There are 7,355 units for processing of agricultural raw materials including food and feed industries.

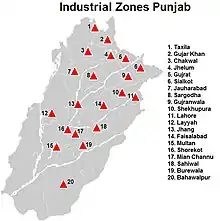

Lahore and Gujranwala Divisions have the largest concentration of small light engineering units. The district of Sialkot excels in sports goods, surgical instruments and cutlery goods. Industrial estates are being developed by Punjab government to boost industrialization in province, Quaid e Azam Business Park Sheikhupura is one of the industrial area which is being developed near Sheikhupura on Lahore-Islamabad motorway.[133]

Punjab is also a mineral-rich province with extensive mineral deposits of coal, iron, gas, petrol, rock salt (with the second largest salt mine in the world), dolomite, gypsum, and silica-sand. The Punjab Mineral Development Corporation is running over a hundred economically viable projects. Manufacturing includes machine products, cement, plastics, and various other goods.

The incidence of poverty differs between the different regions of Punjab. With Northern and Central Punjab facing much lower levels of poverty than Western and Southern Punjab. Those living in Southern and Western Punjab are also a lot more dependent on agriculture due to lower levels of industrialisation in those regions.

Education

The literacy rate has increased greatly over the last 40 years (see the table below). Punjab has the highest Human Development Index out of all of Pakistan's provinces at 0.564.[134]

| Year | Literacy Rate |

|---|---|

| 1972 | 20.7% |

| 1981 | 27.4% |

| 1998 | 46.56% |

| 2009 | 59.6% |

| 2021 | 66.3%[3] |

This is a chart of the education market of Punjab estimated by the government in 1998.

| Qualification | Urban | Rural | Total | Enrollment Ratio(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| – | 23,019,025 | 50,602,265 | 73,621,290 | — |

| Below Primary | 3,356,173 | 11,598,039 | 14,954,212 | 100.00 |

| Primary | 6,205,929 | 18,039,707 | 24,245,636 | 79.68 |

| Middle | 5,140,148 | 10,818,764 | 15,958,912 | 46.75 |

| Matriculation | 4,624,522 | 7,119,738 | 11,744,260 | 25.07 |

| Intermediate | 1,862,239 | 1,821,681 | 3,683,920 | 9.12 |

| BA, BSc... degrees | 110,491 | 96,144 | 206,635 | 4.12 |

| MA, MSc... degrees | 1,226,914 | 764,094 | 1,991,008 | 3.84 |

| Diploma, Certificate... | 418,946 | 222,649 | 641,595 | 1.13 |

| Other qualifications | 73,663 | 121,449 | 195,112 | 0.26 |

Public universities

- Allama Iqbal Medical College, Lahore

- Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan

- COMSATS Institute of Information Technology, Lahore

- COMSATS Institute of Information Technology, Sahiwal

- Fatima Jinnah Women University, Rawalpindi

- Ghazi University D.G.Khan, D.G.Khan

- Government College University, Lahore

- Government College University, Faisalabad

- Gujranwala Medical College, Gujranwala

- Khawaja Fareed University of Engineering and Information Technology, Rahim Yar Khan

- King Edward Medical College, Lahore

- Kinnaird College for Women, Lahore

- Lahore College for Women University, Lahore

- Muhammad Nawaz Sharif University of Agriculture, Multan

- Muhammad Nawaz Sharif University of Engineering & Technology, Multan

- National College of Arts, Lahore

- National Textile University, Faisalabad

- NFC Institute of Engineering and Technology, Multan

- Nishtar Medical College, Multan

- Sargodha Medical College, Sargodha

- Rawalpindi Women University

- The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Bahawalpur

- University College of Agriculture, Sargodha

- University of Agriculture, Faisalabad

- University of Arid Agriculture, Rawalpindi

- University of Education, Lahore

- University of Engineering and Technology, Lahore

- University of Engineering and Technology, Taxila

- University of Gujrat, Gujrat

- University of Health Sciences, Lahore

- University of Sahiwal

- University of Sargodha, Sargodha

- University of the Punjab, Lahore

- University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Lahore

- Virtual University of Pakistan, Lahore

- Women University Multan, Multan

Private universities

- Beaconhouse National University, Lahore

- Forman Christian College, Lahore

- GIFT University, Gujranwala

- Hajvery University, Lahore

- Imperial College of Business Studies, Lahore

- Institute of Management Sciences, Lahore, Pak-AIMS, Lahore

- Lahore School of Economics, Lahore

- Lahore University of Management Sciences, Lahore

- Minhaj International University, Lahore

- National University of Computer & Emerging Sciences, Lahore

- Pakistan Institute of Fashion and Design, Lahore

- Sargodha Institute of Technology, Sargodha

- University of Central Punjab, Lahore

- University of Chenab, Gujrat

- University of Faisalabad, Faisalabad

- University of Health Sciences, Lahore

- University of Lahore, Lahore

- University of Management and Technology, Lahore

- University of South Asia, Lahore

- University College Lahore, Lahore

- University of Wah, Wah Cantonment

- HITEC University, Taxila Cantonment

- Institute of Southern Punjab, Multan

- Pakistan Institute of Engineering and Technology, Multan

- Multan Medical and Dental College, Multan

- Lahore Garrison University, Lahore[137]

Culture

The culture in Punjab grew out of the settlements along the five rivers, which served as an important route to the Near East as early as the ancient Indus Valley civilization, dating back to 3000 BCE.[110] Agriculture has been the major economic feature of the Punjab and has therefore formed the foundation of Punjabi culture, with one's social status being determined by landownership.[110] The Punjab emerged as an important agricultural region, especially following the Green Revolution during the mid-1960's to the mid-1970's, has been described as the "breadbasket of both India and Pakistan".[110]

Fairs and festivals

The Islamic festivals are typically observed.[138][139] Non-Islamic festivals include Lohri, Basant and Vaisakhi, which are usually celebrated as seasonal festivals.[140] The Islamic festivals are set according to the lunar Islamic calendar (Hijri), and the date falls earlier by 10 to 13 days from year to year.[141]

Some Islamic clerics and some politicians have attempted to ban the participation of non-Islamic festivals because of the religious basis,[142] and they being declared haram (forbidden in Islam).[143]

Tourism

Tourism in Punjab is regulated by the Tourism Development Corporation of Punjab.[144] The province has a number of large cosmopolitan cities, including the provincial capital Lahore. Major visitor attractions there include Lahore Fort and Shalimar Gardens, which are now recognised World Heritage Sites. The Walled City of Lahore, Badshahi Mosque, Wazir Khan Mosque, Tomb of Jahangir and Nur Jahan, Tomb of Asaf Khan, Chauburji and other major sites visited by tourists each year.

Murree is a famous hill station stop for tourists.[145] The Pharwala Fort, which was built by an ancient Hindu civilisation, is on the outskirts of the city. The city of Sheikhupura also has a number of sites from the Mughal Empire, including the World Heritage-listed Rohtas Fort near Jhelum. The Katasraj temple in the city of Chakwal is a major destination for Hindu devotees. The Khewra Salt Mines is one of the oldest mines in South Asia. Faisalabad's clock tower and eight bazaars were designed to represent the Union Jack.[146]

The province's southward is arid. Multan is known for its mausoleums of saints and Sufi pirs. The Multan Museum, Multan fort, DHA 360° zoo and Nuagaza tombs are significant attractions in the city. The city of Bahawalpur is located near the Cholistan and Thar deserts. Derawar Fort in the Cholistan Desert is the site for the annual Cholistan Jeep Rally. The city is also near the ancient site of Uch Sharif which was once a Delhi Sultanate stronghold. The Noor Mahal, Sadiq Ghar Palace, Darbar Mall were built during the reign of the Nawabs. The Lal Suhanra National Park is a major zoological garden on the outskirts of the city.

Social issues

One social/educational issue is the status of Punjabi language. According to Manzur Ejaz, "In Central Punjab, Punjabi is neither an official language of the province nor it is used as medium of education at any level. There are only two daily newspapers published in Punjabi in the Central areas of Punjab. Only a few monthly literary magazines constitute Punjabi press in Pakistan".[147]

Notable people

- List of people from Punjab, Pakistan, also includes people born in what is today Indian Punjab but moved to Pakistan after partition

- List of Punjabi people, also includes people of Punjabi ethnicity from India and elsewhere

See also

- Punjab

- List of people from Punjab, Pakistan

Notes

- Craterus supervised the construction. These cities are yet to be identified.

- 1941 figure reached by combining total population of all districts (Lahore, Sialkot, Gujranwala, Sheikhupura, Gujrat, Shahpur, Jhelum, Rawalpindi, Attock, Mianwali, Montgomery, Lyallpur, Jhang, Multan, Muzaffargargh, Dera Ghazi Khan), one tehsil (Shakargarh -- then part of Gurdaspur District), and one princely state (Bahawalpur) in British Punjab as per 1941 census data. These districts, tehsil, and princely state would ultimately make up the subdivision of West Punjab Province, Pakistan (contemporarily known as Punjab Province, Pakistan), following the partition of India in 1947. The districts and princely state in 1941 that made up Punjab Province, Pakistan have since undergone various bifurcations at several points throughout the post-independence era, due to the rapid population growth witnessed across the province.

- 1941 census: Including Ad-Dharmis

- 1941 census: Including Jainism, Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Tribals, others, or not stated

2017 census: Also includes Sikhs, Baháʼís, Ahmadyyas, others, and not stated

References

- 2017 Census Archived 15 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- "Sub-national HDI - Subnational HDI - Global Data Lab". Globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- "KP Achieves Highest Literacy Rate Growth Among All Provinces". 9 June 2022.

- "Provincial Assembly – Punjab". Archived from the original on 1 February 2009.

- Beck, Roger B. (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell. ISBN 0-395-87274-X.

- Needham, Joseph (2004). Within the Four Seas: The Dialogue of East and West. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-36166-4.

- Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004). A History of India (4th ed.). Routledge. ISBN 0-415-32919-1.

In the early centuries the centre of Buddhist scholarship was the University of Taxila.

- Balakrishnan Muniapan; Junaid M. Shaikh (2007). "Lessons in corporate governance from Kautilya's Arthashastra in ancient India". World Review of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development. 3 (1).

Kautilya was also a Professor of Politics and Economics at Taxila University. Taxila University is one of the oldest known universities in the world and it was the chief learning centre in ancient India.

- Radha Kumud Mookerji 1989, p. 478: "Thus the various centres of learning in different parts of the country became affiliated, as it were, to the educational centre, or the central university, of Taxila which exercised a kind of intellectual suzerainty over the wide world of letters in India."

- Radha Kumud Mookerji 1989, p. 479: "This shows that Taxila was a seat not of elementary, but higher, education, of colleges or a university as distinguished from schools."

- Amjad 1989, p. .

- Waheed, Sarah Fatima (20 January 2022). Hidden Histories of Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-83452-0.

- Dalrymple, William (29 June 2015). "THE GREAT DIVIDE". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 14 July 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- Government of the Punjab – Planning & Development Department (March 2015). "PUNJAB GROWTH STRATEGY 2018 Accelerating Economic Growth and Improving Social Outcomes" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

The industrial sector of Punjab employs around 23% of the province's labour force and contributes 24% to the provincial GDP

- Farooqui, Tashkeel (20 June 2016). "Northern Punjab, urban Sindh people more prosperous than rest of country: report". The Express Tribune. Archived from the original on 24 July 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- Arif, G. M. "Poverty Profile of Pakistan" (PDF). Benazir Income Support Programme. Government of Pakistan. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

Among the four provinces, the highest incidence of poverty is found in Sindh (45%), followed by Balochistan (44%), Khyber Pakhtukhaw (KP) (37%) and Punjab (21%)

- Islamabad Capital Territory is Pakistan's least impoverished administrative unit, but ICT is not a province. Azad Kashmir also has a rate of poverty lower than Punjab, but is not a province.

- Arif, G. M. "Poverty Profile of Pakistan" (PDF). Benazir Income Support Programme. Government of Pakistan. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

See Table 5, Page 12 "Sialkot District"

- Arif, G. M. "Poverty Profile of Pakistan" (PDF). Benazir Income Support Programme. Government of Pakistan. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

See Table 5, Page 12 "Rajanpur District"

- Government of the Punjab – Planning & Development Department (March 2015). "PUNJAB GROWTH STRATEGY 2018 Accelerating Economic Growth and Improving Social Outcomes" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

Punjab is among the most urbanized regions of South Asia and is experiencing a consistent and long-term demographic shift of the population to urban regions and cities, with around 40% of the province's population living in urban areas

- Gilmartin, David (1988). Empire and Islam: Punjab and the Making of Pakistan. University of California Press. pp. 40–41.

- Macauliffe, Max Arthur (2004) [1909]. The Sikh Religion – Its Gurus, Sacred Writings and Authors. India: Low Price Publications. ISBN 81-86142-31-2.

- Singh, Khushwant (2006). The Illustrated History of the Sikhs. India: Oxford University Press. pp. 12–13. ISBN 0-19-567747-1.

- Malik, Iftikhar Haider (2008). The History of Pakistan. Greenwood Publishing Group.

- "Katas Raj Temples". Temple Darshan. Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- "Properties inscribed on the World Heritage List (Pakistan)". UNESCO. UNESCO. Archived from the original on 4 July 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- H K Manmohan Siṅgh. "The Punjab". The Encyclopedia of Sikhism, Editor-in-Chief Harbans Singh. Punjabi University, Patiala. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- Gandhi, Rajmohan (2013). Punjab: A History from Aurangzeb to Mountbatten. New Delhi, India, Urbana, Illinois: Aleph Book Company. p. 1 ("Introduction"). ISBN 978-93-83064-41-0.

- "Punjab." Pp. 107 in Encyclopædia Britannica (9th ed.), vol. 20.

- Kenneth Pletcher, ed. (2010). The Geography of India: Sacred and Historic Places. Britannica Educational Publishing. p. 199. ISBN 978-1-61530-202-4.

The word's origin can perhaps be traced to panca nada, Sanskrit for "five rivers" and the name of a region mentioned in the ancient epic the Mahabharata.

- Rajesh Bala (2005). "Foreign Invasions and their Effect on Punjab". In Sukhdial Singh (ed.). Punjab History Conference, Thirty-seventh Session, March 18-20, 2005: Proceedings. Punjabi University. p. 80. ISBN 978-81-7380-990-3.

The word Punjab is a compound of two words-Panj (Five) and aab (Water), thus signifying the land of five waters or rivers. This origin can perhaps be traced to panch nada, Sanskrit for 'Five rivers' the word used before the advent of Muslims with a knowledge of Persian to describe the meeting point of the Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej rivers, before they joined the Indus.

- Lassen, Christian. 1827. Commentatio Geographica atque Historica de Pentapotamia Indica [A Geographical and Historical Commentary on Indian Pentapotamia]. Weber. p. 4: "That part of India which today we call by the Persian name ''Penjab'' is named Panchanada in the sacred language of the Indians; either of which names may be rendered in Greek by Πενταποταμια. The Persian origin of the former name is not at all in doubt, although the words of which it is composed are both Indian and Persian.... But, in truth, that final word is never, to my knowledge, used by the Indians in proper names compounded in this way; on the other hand, there exist multiple Persian names which end with that word, e.g., Doab and Nilab. Therefore, it is probable that the name Penjab, which is today found in all geographical books, is of more recent origin and is to be attributed to the Muslim kings of India, among whom the Persian language was mostly in use. That the Indian name Panchanada is ancient and genuine is evident from the fact that it is already seen in the Ramayana and Mahabharata, the most ancient Indian poems, and that no other exists in addition to it among the Indians; for Panchála, which English translations of the Ramayana render with Penjab...is the name of another region, entirely distinct from Pentapotamia...."

- Latif, Syad Muhammad (1891). History of the Panjáb from the Remotest Antiquity to the Present Time. Calcultta Central Press Company. p. 1.

The Panjáb, the Pentapotamia of the Greek historians, the north-western region of the empire of Hindostán, derives its name from two Persian words, panj (five), an áb (water, having reference to the five rivers which confer on the country its distinguishing features."

- Khalid, Kanwal (2015). "Lahore of Pre Historic Era" (PDF). Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan. 52 (2): 73.

The earliest mention of five rivers in the collective sense was found in Yajurveda and a word Panchananda was used, which is a Sanskrit word to describe a land where five rivers meet. [...] In the later period the word Pentapotamia was used by the Greeks to identify this land. (Penta means 5 and potamia, water ___ the land of five rivers) Muslim Historians implied the word "Punjab " for this region. Again it was not a new word because in Persian-speaking areas, there are references of this name given to any particular place where five rivers or lakes meet.

- Minahan, James (2012). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 257–259. ISBN 978-1-59884-659-1.

- "Arrian. Indica. English | The Online Books Page". onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- Bosworth, Albert Brian (1993). "The campaign of the Hydaspes". Conquest and Empire: The Reign of Alexander the Great. Cambridge University Press. pp. 125–130.

- Holt, Frank Lee (2003). Alexander the Great and the mystery of the elephant medallions. University of California Press.

- Rogers, p. 200.

- Bosworth, Albert Brian (1993). "From the Hydaspes to the Southern Ocean". Conquest and Empire: The Reign of Alexander the Great. Cambridge University Press.

- Anson, Edward M. (2013). Alexander the Great: Themes and Issues. Bloomsbury. p. 151. ISBN 9781441193797.

- Roy 2004, pp. 23–28.

- Heckel, Waldemar (2006). Who's Who in the Age of Alexander the Great: Prosopography of Alexander's Empire. Wiley. ISBN 9781405112109.

- Irfan Habib; Vivekanand Jha (2004). Mauryan India. A People's History of India. Aligarh Historians Society / Tulika Books. p. 16. ISBN 978-81-85229-92-8.

- Hazel, John (2013). Who's Who in the Greek World. Routledge. p. 155. ISBN 9781134802241.

Menander king in India, known locally as Milinda, born at a village named Kalasi near Alasanda (Alexandria-in-the-Caucasus), and who was himself the son of a king. After conquering the Punjab, where he made Sagala his capital, he made an expedition across northern India and visited Patna, the capital of the Mauraya empire, though he did not succeed in conquering this land as he appears to have been overtaken by wars on the north-west frontier with Eucratides.

- Ahir, D. C. (1971). Buddhism in the Punjab, Haryana, and Himachal Pradesh. Maha Bodhi Society of India. p. 31. OCLC 1288206.

Demetrius died in 166 B.C., and Apollodotus, who was a near relation of the King died in 161 B.C. After his death, Menander carved out a kingdom in Punjab. Thus from 161 B.C. onward Menander was the ruler of Punjab till his death in 145 B.C. or 130 B.C.

- "Menander | Indo-Greek king". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- Hudud, al-Alam (1970). Hudud Al-Alam, 'the Regions of the World': A Persian Geography, 327A.H. - 982A.D. Luzac.

- Rehman 1976, p. 48.

- Rehman 1976, pp. 48–50.

- Rehman 1976, p. 187 and Pl. V B., "the horseman is shown wearing a turban-like head-gear with a small globule on the top".

- MacLean, Derryl N. (1989). Religion and Society in Arab Sind. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-08551-0.

- Mehta, Jaswant Lal (1979). Advanced Study in the History of Medieval India. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 76. ISBN 978-81-207-0617-0.

- Richard M. Eaton (2019). India in the Persianate Age: 1000–1765. p. 117. ISBN 978-0520325128.

- Mahajan, V. D. (2007). History of medieval India (10th ed.). New Delhi: S Chand. ISBN 978-81-219-0364-6. OCLC 768730047.

- Porter, Yves; Degeorge, Gérard (2009). The Glory of the Sultans: Islamic Architecture in India. Though Timur had since withdrawn his forces, the Sayyid Khizr Khān, the scion of a venerable Arab family who had settled in Multān, continued to pay him tribute: Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-08-030110-9.

- The Cambridge History of India. The claim of Khizr Khān, who founded the dynasty known as the Sayyids, to descent from the prophet of Arabia was dubious, and rested chiefly on its causal recognition by the famous saint Sayyid Jalāl - ud - dīn of Bukhārā .: S. Chand. 1958.

- Ramesh Chandra Majumdar (1951). The History and Culture of the Indian People: The Delhi sultanate. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

- Wink, André (2003). Indo-Islamic society: 14th - 15th centuries. BRILL. p. 143. ISBN 978-90-04-13561-1.

Similarly, Zaffar Khan Muzaffar, the first independent ruler of Gujarat was not a foreign muslim but a Khatri convert, of a low subdivision called the Tank, originally from Southern Punjab

- Orsini, Francesca (2015). After Timur left : culture and circulation in fifteenth-century North India. Oxford Univ. Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-19-945066-4. OCLC 913785752.

-

- Abbas, Syed Anwer (2021). Confluence of Cultures: Hindu, Muslim, Buddhists & Jain mosque and Mausoleum. Notion Press. ISBN 9781639046041.

- Chandra, Satish (2004). Medieval India ( From Sultanat to the Mughals), PART ONE Delhi Sultanat ( 1206-1526). Har-Anand Publications. p. 218. ISBN 9788124110645.

- Muzaffar Husain Syed, Syed Saud Akhtar, BD Usmani (2011). Concise History of Islam. p. 271.

- Kapadia, Aparna (2018). Gujarat: The Long Fifteenth Century and the Making of a Region. Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 9781107153318.

- Edward James Rapson, Sir Wolseley Haig, Sir Richard Burn (1965). The Cambridge History of India: Turks and Afghans, edited by W Haig, 1965. Cambridge. p. 294.

- Mahajan, VD (2007). History of Medieval India. S. Chand. p. 245. ISBN 9788121903646.*Jenkins, Everett (2010). The Muslim Diaspora - A comprehensive reference to the spread of Islam in Asia, Africa, Europe and the America, 570 - 1799. McFarland & Company Inc. p. 275. ISBN 9780786447138.

- Jutta, Jain-Neubauer (1981). The Stepwells of Gujarat: In Art- Historical perspective. p. 62.

- Saran, Kishori Lal (1992). The legacy of Muslim Rule in India. Aditya Prakashan. p. 233. ISBN 9788185689036.

- Lane-Pool, Stanley (2014). Mohammadan Dyn: Orientalism V 2 - volume 2, page -312, writer. p. 312. ISBN 9781317853947.

-

- Kapadia, Aparna (2018). In Praise of Kings: Rajputs, Sultans and Poets in Fifteenth-century Gujarat. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-107-15331-8.

Gujarati historian Sikandar does narrate the story of Muzaffar Shah's ancestors having once been Hindus "Tanks" a branch of Khatris who trace their dynasty from the solar god.

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (25 April 2008). Historical Dictionary of Medieval India. Scarecrow Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-8108-5503-8.

The founder of the Gujarat Sultanate he was a convert from a sect of Hindu Khatris known as Tanks.

- Misra, S. C. (Satish Chandra) (1963). The rise of Muslim power in Gujarat; a history of Gujarat from 1298 to 1442. New York: Asia Pub. House. p. 137.

Zafar Khan was not a foreign muslim. He was a convert to Islam from a sect of the Khatris known as Tank.

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2004). Gunpowder and Firearms: Warfare in Medieval India. Oxford University Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-19-566526-0.

Zafar Khan (entitled Muzaffar Shah) himself was a convert to Islam from a sub-caste of the Khatris known as Tank.

- Kapadia, Aparna (2018). In Praise of Kings: Rajputs, Sultans and Poets in Fifteenth-century Gujarat. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-107-15331-8.

- Ahmed, Iftikhar (1984). "Territorial Distrtibution of Jatt Castes in Punjab c. 1595 - c. 1881". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. Indian History Congress. 45: 429, 432. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44140224.

- Mubārak, A.F.; Blochmann, H. (1891). The Ain I Akbari. Bibliotheca Indica. Vol. 2. Asiatic Society of Bengal. p. 321. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- Lambrick, H. T. (1975). Sind : a general introduction. Hyderabad: Sindhi Adabi Board. p. 212. ISBN 0-19-577220-2. OCLC 2404471.

- Roseberry 1987, p. 177.

- Roseberry 1987, p. .

- Elliot & Dowson (1872), Chapter XXI Tárikh-i Mubárak Sháhí, of Yahyá bin Ahmad.

- History, Hourly (June 2020). Mughal Empire: A History from Beginning to End. Independently Published. ISBN 979-8-6370-3729-2.

- Journal of Central Asia. Vol. 15. Centre for the Study of the Civilizations of Central Asia, Quaid-i-Azam University. 1992. p. 84. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

Sadullah Khan was the son of Amir Bakhsh a cultivator of Chiniot . He belongs to Jat family. He was born on Thursday , the 10th Safar 1000 A.H./1591 A.C.

- Quddus, S.A. (1992). Punjab, the Land of Beauty, Love, and Mysticism. Royal Book Company. p. 402. ISBN 978-969-407-130-5. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- Siddiqui, Shabbir A. (1986). "Relations Between Dara Shukoh and Sa'adullah Khan". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 47: 273–276. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44141552.

- Koch, Ebba (2006). The complete Taj Mahal: and the riverfront gardens of Agra. Illustrated by Richard André Barraud. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-500-34209-1. OCLC 69022179.

- Chhabra, G.S. (2005). Advance Study in the History of Modern India (Volume-1: 1707-1803). Lotus Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-81-89093-06-8.

- AA Sheikh Md Asrarul Hoque Chisti (2012). "Shahbaz Khan". In Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- Grewal, J. S. (1998). "The Sikh empire (1799–1849) - Chapter 6". The Sikhs of the Punjab. The New Cambridge History of India (Revised ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 126–128. ISBN 0-521-63764-3.

- Minahan, James (2012). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-659-1.

- Hibbert, Christopher (1980). The great mutiny: India 1857. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-14-004752-3.

- "Pakistan Geotagging: Partition of Punjab in 1947". 3 October 2014. Archived from the original on 8 February 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2016.. Daily Times (10 May 2012). Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- Talbot, Ian (2009). "Partition of India: The Human Dimension". Cultural and Social History. 6 (4): 403–410. doi:10.2752/147800409X466254. S2CID 147110854.

The number of casualties remains a matter of dispute, with figures being claimed that range from 200,000 to 2 million victims.

- D'Costa, Bina (2011). Nationbuilding, Gender and War Crimes in South Asia. Routledge. p. 53. ISBN 978-0415565660.

- Butalia, Urvashi (2000). The Other Side of Silence: Voices From the Partition of India. Duke University Press.

- Sikand, Yoginder (2004). Muslims in India Since 1947: Islamic Perspectives on Inter-Faith Relations. Routledge. p. 5. ISBN 978-1134378258.

- Dyson 2018, pp. 188–189.

- "Punjab". Small and Medium Enterprises Development Authority. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- Ali, Choudhary Rahmat (28 January 1933). "Now or Never. Are we to live or perish forever?". Archived from the original on 30 June 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- S. M. Ikram (1 January 1995). Indian Muslims and partition of India. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. pp. 177–. ISBN 978-81-7156-374-6. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- "Mercury drops to freezing point – Dawn Pakistan". 6 January 2007.

- "Welcome to Official Web site of Punjab, India". Archived from the original on 23 November 2005. Retrieved 23 November 2005.

- The figures for 1998 are from pop by province – statpak.gov.pk. The estimates for 2012 are from Population shoots up by 47 percent since 1998 Archived 1 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Thenews.com.pk. Retrieved on 12 July 2013.

- India. Census Commissioner 1941, p. 8.

- Arif, G. M. "Poverty Profile of Pakistan" (PDF). Benazir Income Support Programme. Government of Pakistan. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

See Table 5, Page 12

- "CCI defers approval of census results until elections". Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Shackle 1979, p. 198.

- Khan, Muhammad Kamal (8 April 2020). Pashto Phonology: An Evaluation of the Relationship between Syllable Structure and Word Order. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-5275-4925-8.

In some cities of Punjab, such as Attock, Mianwali and Rawalpindi, Pashto is spoken among other local languages.

- "Punjabis Without Punjabi". apnaorg.com. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Inferiority complex declining Punjabi language: Punjab University Vice-Chancellor". ppinewsagency.com. Pakistan Press International. Archived from the original on 27 November 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Urdu-isation of Punjab - The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. 4 May 2015. Archived from the original on 27 November 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- "Rally for ending 150-year-old 'ban on education in Punjabi". The Nation. 21 February 2011. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- "Sufi poets can guarantee unity". The Nation. 26 August 2015. Archived from the original on 30 October 2015.

- "Supreme Court's Urdu verdict: No language can be imposed from above". The Nation. 15 September 2015. Archived from the original on 16 September 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- "Two-member SC bench refers Punjabi language case to CJP". Business Recorder. 14 September 2015. Archived from the original on 21 October 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- "Pakistan should have adopted Punjabi as national language: Hafiz Saeed" Zee News. 6 March 2016

- "Pakistan should have adopted Punjabi as national language: Hafiz Saeed | Zee News". Zee News. 6 March 2016. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Mind your language—The movement for the preservation of Punjabi". The Herald. 2 September 2106.

- "Mind your language—The movement for the preservation of Punjabi - People & Society - Herald". herald.dawn.com. 4 August 2016. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Punjabi in schools: Pro-Punjabi outfits in Pakistan threaten hunger strike". The Times of India. 4 October 2015.

- "Punjabi in schools: Pro-Punjabi outfits in Pakistan threaten hunger strike - Times of India". timesofindia.indiatimes.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Rally for Ending the 150-year-old Ban on Education in Punjabi" The Nation. 21 February 2011.

- "Rally for ending 150-year-old 'ban on education in Punjabi". nation.com.pk. 21 February 2011. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Population by Religion" (PDF). pbs.gov.pk. Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- "SALIENT FEATURES OF FINAL RESULTS CENSUS-2017" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- India. Census Commissioner 1941, p. 42.

- Nayar, Kamala Elizabeth (2012). The Punjabis in British Columbia: Location, Labour, First Nations, and Multiculturalism. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. ISBN 978-0-7735-4070-5.

- Lindsay Jones; Mircea Eliade; Charles J. Adams, eds. (2005). Encyclopedia of religion (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA. pp. 9552–9553. ISBN 0-02-865733-0. OCLC 56057973.

- "Vedic religion". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Sullivan, Bruce M. (2001). The A to Z of Hinduism. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-8108-4070-7. OCLC 46732488.

- Samuel, Geoffrey (2010). The origins of yoga and tantra : Indic religions to the thirteenth century. Cambridge University Press. pp. 97–99, 113–118. ISBN 978-0-521-69534-3. OCLC 781947262.

- Michaels, Axel (2004). Hinduism. Past and present. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 38.

- Michaels (2004, p. 38): "The legacy of the Vedic religion in Hinduism is generally overestimated. The influence of the mythology is indeed great, but the religious terminology changed considerably: all the key terms of Hinduism either do not exist in Vedic or have a completely different meaning. The religion of the Veda does not know the ethicised migration of the soul with retribution for acts (karma), the cyclical destruction of the world, or the idea of salvation during one's lifetime (jivanmukti; moksa; nirvana); the idea of the world as illusion (maya) must have gone against the grain of ancient India, and an omnipotent creator god emerges only in the late hymns of the rgveda. Nor did the Vedic religion know a caste system, the burning of widows, the ban on remarriage, images of gods and temples, Puja worship, Yoga, pilgrimages, vegetarianism, the holiness of cows, the doctrine of stages of life (asrama), or knew them only at their inception. Thus, it is justified to see a turning point between the Vedic religion and Hindu religions."

Jamison, Stephanie; Witzel, Michael (1992). "Vedic Hinduism" (PDF). Harvard University. p. 3.: "... to call this period Vedic Hinduism is a contradictio in terminis since Vedic religion is very different from what we generally call Hindu religion – at least as much as Old Hebrew religion is from medieval and modern Christian religion. However, Vedic religion is treatable as a predecessor of Hinduism."

See also Halbfass 1991, pp. 1–2 - Flood, Gavin (13 July 1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43878-0.

- Nayar, Kamala Elizabeth (2012). The Punjabis in British Columbia: Location, Labour, First Nations, and Multiculturalism. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-7735-4070-5.

- "In ancient Punjab, religion was fluid, not watertight, says Romila Thapar". The Indian Express. 3 May 2019.

Thapar said Buddhism was very popular in Punjab during the Mauryan and post-Mauryan period. Bookended between Gandhara in Taxila on the one side where Buddhism was practised on a large scale and Mathura on another side where Buddhism, Jainism and Puranic religions were practised, this religion flourished in the state. But after the Gupta period, Buddhism began to decline.

- Rambo, Lewis R.; Farhadian, Charles E. (6 March 2014). The Oxford Handbook of Religious Conversion. Oxford University Press. pp. 489–491. ISBN 978-0-19-971354-7.