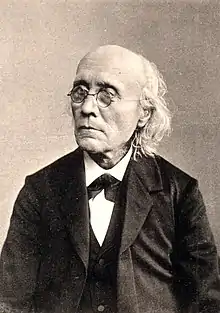

Gustav Fechner

Gustav Theodor Fechner (/ˈfɛxnər/; German: [ˈfɛçnɐ]; 19 April 1801 – 18 November 1887)[1] was a German physicist, philosopher, and experimental psychologist. A pioneer in experimental psychology and founder of psychophysics (techniques for measuring the mind), he inspired many 20th-century scientists and philosophers. He is also credited with demonstrating the non-linear relationship between psychological sensation and the physical intensity of a stimulus via the formula: , which became known as the Weber–Fechner law.[2][3]

Gustav Fechner | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Gustav Theodor Fechner 19 April 1801 Groß Särchen (near Muskau), Saxony, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 18 November 1887 (aged 86) |

| Nationality | German |

| Education | Medizinische Akademie Carl Gustav Carus Leipzig University (PhD, 1835) |

| Known for | Weber–Fechner law |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Experimental psychology |

| Institutions | Leipzig University |

| Thesis | De variis intensitatem vis Galvanicae metiendi methodis [Various methods of measuring Galvanic force intensity] (1835) |

| Notable students | Hermann Lotze |

| Influences | Immanuel Kant |

| Influenced | Gerardus Heymans Wilhelm Wundt Ernst Mach William James Alfred North Whitehead Charles Hartshorne Ernst Weber Sigmund Freud Friedrich Paulsen Ludwig von Bertalanffy |

Early life and scientific career

Fechner was born at Groß Särchen, near Muskau, in Lower Lusatia, where his father, a maternal uncle, and his paternal grandfather were pastors. His mother, Johanna Dorothea Fechner (b. 1774), née Fischer, also came from a religious family. Despite these religious influences, Fechner became an atheist in later life.[4]

Fechner's father, Samuel Traugott Fischer Fechner (1765-1806) was free-thinking in many ways, for example by having his children be vaccinated, teaching them Latin, and being a passionate grower of fruit.[4] He died unexpectedly in 1806, leaving the family destitute.[5] Fechner had an elder brother, Eduard Clemens Fechner (1799-1861) and three younger sisters: Emilie, Clementine, and Mathilde. Fechner and his brother were then raised for a few years by his maternal uncle—the pastor, before being reunited with his mother and sistes in Dresden.[4]

Fechner was educated first at Sorau (now Żary in Western Poland).

In 1817 Fechner studied medicine for six months at the Medizinische Akademie Carl Gustav Carus in Dresden and from 1818 at the University of Leipzig, the city in which he spent the rest of his life.[6] He earned his PhD from Leipzig in 1823.[7]

In 1834 he was appointed professor of physics at Leipzig. But in 1839, he injured his eyes in the research on afterimages by gazing at the sun through colored glasses,[8] while studying the phenomena of color and vision, and, after much suffering, resigned. Subsequently, recovering, he turned to the study of the mind and its relations with the body, giving public lectures on the subjects dealt with in his books.[9] Whilst lying in bed, Fechner had an insight into the relationship between mental sensations and material sensations. This insight proved to be significant in the development of psychology as there was now a quantitative relationship between the mental and physical worlds.[10]

Contributions

Fechner published chemical and physical papers, and translated chemical works by Jean-Baptiste Biot and Louis Jacques Thénard from French. He also wrote several poems and humorous pieces, such as the Vergleichende Anatomie der Engel (1825), written under the pseudonym of "Dr. Mises."[9]

Elemente der Psychophysik

Fechner's epoch-making work was his Elemente der Psychophysik (1860). He started from the monistic thought that bodily facts and conscious facts, though not reducible one to the other, are different sides of one reality. His originality lies in trying to discover an exact mathematical relation between them. The most famous outcome of his inquiries is the law known as Fechner's Law, which may be expressed as follows:[9]

- "In order that the intensity of a sensation may increase in arithmetical progression, the stimulus must increase in geometrical progression."

The law has been found to be immensely useful, but to fail for very faint and for very strong sensations. Within its useful range, Fechner's law is that sensation is a logarithmic function of physical intensity. S. S. Stevens pointed out that such a law does not account for the fact that perceived relationships among stimuli (e.g., papers coloured black, dark grey, grey, light grey, and white) are unchanged with changes in overall intensity (i.e., in the level of illumination of the papers). He proposed, in his famous 1961 paper entitled "To Honor Fechner and Repeal His Law", that intensity of stimulation is related to perception via a power-law.

Fechner's general formula for getting at the number of units in any sensation is S = c log R, where S stands for the sensation, R for the stimulus numerically estimated, and c for a constant that must be separately determined by experiment in each particular order of sensibility. Fechner's reasoning has been criticized on the grounds that although stimuli are composite, sensations are not. "Every sensation," says William James, "presents itself as an indivisible unit; and it is quite impossible to read any clear meaning into the notion that they are masses of units combined."[9]

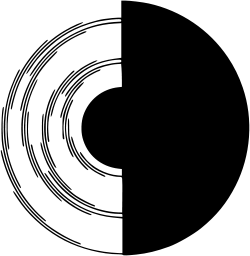

The Fechner color effect

In 1838, he also studied the still-mysterious perceptual illusion of what is still called the Fechner color effect, whereby colors are seen in a moving pattern of black and white. The English journalist and amateur scientist Charles Benham, in 1894, enabled English-speakers to learn of the effect through the invention of the spinning top that bears his name, Benham's top. Whether Fechner and Benham ever actually met face to face is not known.

The median

In 1878, Fechner published a paper in which he developed the notion of the median. He later delved into experimental aesthetics and thought to determine the shapes and dimensions of aesthetically pleasing objects. He mainly used the sizes of paintings as his data base. In his 1876 Vorschule der Aesthetik, he used the method of extreme ranks for subjective judgements.[11]

Fechner is generally credited with introducing the median into the formal analysis of data.[12]

Synesthesia

In 1871, Fechner reported the first empirical survey of coloured letter photisms among 73 synesthetes.[13][14] His work was followed in the 1880s by that of Francis Galton.[15][16][17]

Corpus callosum split

One of Fechner's speculations about consciousness dealt with brain. During his time, it was known that the brain is bilaterally symmetrical and that there is a deep division between the two halves that are linked by a connecting band of fibers called the corpus callosum. Fechner speculated that if the corpus callosum were split, two separate streams of consciousness would result - the mind would become two. Yet, Fechner believed that his theory would never be tested; he was incorrect. During the mid-twentieth century, Roger Sperry and Michael Gazzaniga worked on epileptic patients with sectioned corpus callosum and observed that Fechner's idea was correct.[18]

Golden section hypothesis

Fechner constructed ten rectangles with different ratios of width to length and asked numerous observers to choose the "best" and "worst" rectangle shape. He was concerned with the visual appeal of rectangles with different proportions. Participants were explicitly instructed to disregard any associations that they have with the rectangles, e.g. with objects of similar ratios. The rectangles chosen as "best" by the largest number of participants and as "worst" by the fewest participants had a ratio of 0.62 (21:34).[19] This ratio is known as the "golden section" (or golden ratio) and referred to the ratio of a rectangle's width to length that is most appealing to the eye. Carl Stumpf was a participant in this study.

However, there has been some ongoing dispute on the experiment itself, as the fact that Fechner deliberately discarded results of the study ill-fitting to his needs became known, with many mathematicians, including Mario Livio, refuting the result of the experiment.[20]

The two-piece normal distribution

In his posthumously published Kollektivmasslehre (1897), Fechner introduced the Zweiseitige Gauss'sche Gesetz or two-piece normal distribution, to accommodate the asymmetries he had observed in empirical frequency distributions in many fields. The distribution has been independently rediscovered by several authors working in different fields.[21]

Fechner's paradox

In 1861, Fechner reported that if he looked at a light with a darkened piece of glass over one eye then closed that eye, the light appeared to become brighter, even though less light was coming into his eyes.[22] This phenomenon has come to be called Fechner's paradox.[23] It has been the subject of numerous research papers, including in the 2000s.[24] It occurs because the perceived brightness of the light with both eyes open is similar to the average brightness of each light viewed with one eye.[22]

Influence

Fechner, along with Wilhelm Wundt and Hermann von Helmholtz, is recognized as one of the founders of modern experimental psychology. His clearest contribution was the demonstration that because the mind was susceptible to measurement and mathematical treatment, psychology had the potential to become a quantified science. Theorists such as Immanuel Kant had long stated that this was impossible, and that therefore, a science of psychology was also impossible.

Though he had a vast influence on psychophysics, the actual disciples of his general philosophy were few. Ernst Mach was inspired by his work on psychophysics.[25] William James also admired his work: in 1904, he wrote an admiring introduction to the English translation of Fechner's Büchlein vom Leben nach dem Tode (Little Book of Life After Death). Furthermore, he influenced Sigmund Freud, who refers to Fechner when introducing the concept of psychic locality in his The Interpretation of Dreams that he illustrates with the microscope-metaphor.[26][27][28]

Fechner's world concept was highly animistic. He felt the thrill of life everywhere, in plants, earth, stars, the total universe. Man stands midway between the souls of plants and the souls of stars, who are angels.[29] God, the soul of the universe, must be conceived as having an existence analogous to men. Natural laws are just the modes of the unfolding of God's perfection. In his last work Fechner, aged but full of hope, contrasts this joyous "daylight view" of the world with the dead, dreary "night view" of materialism. Fechner's work in aesthetics is also important. He conducted experiments to show that certain abstract forms and proportions are naturally pleasing to our senses, and gave some new illustrations of the working of aesthetic association.[9] Charles Hartshorne saw him as a predecessor on his and Alfred North Whitehead's philosophy and regretted that Fechner's philosophical work had been neglected for so long.[30]

Fechner's position in reference to predecessors and contemporaries is not very sharply defined. He was remotely a disciple of Schelling,[9] learned much from Baruch Spinoza, G. W. Leibniz, Johann Friedrich Herbart, Arthur Schopenhauer, and Christian Hermann Weisse, and decidedly rejected G. W. F. Hegel and the monadism of Rudolf Hermann Lotze.

Fechner's work continues to have an influence on modern science, inspiring continued exploration of human perceptual abilities by researchers such as Jan Koenderink, Farley Norman, David Heeger, and others.

Honours

Fechner Crater

In 1970, the International Astronomical Union named a crater on the far side of the moon after Fechner.[31]

Fechner Day

In 1985 the International Society for Psychophysics called its annual conference Fechner Day. The conference is now scheduled to include 22 October to allow psychophysicists to celebrate the anniversary of Fechner's waking up on that day in 1850 with a new approach into how to study the mind.[32] Fechner Day runs annually with the 2021 Fechner Day being the 37th.[33] It is organized annually, by a different academic host each year.[34][35] During the pandemic resulting from COVID-19, Fechner Day was held online in 2020 and 2021.

Family and later life

Little is known of Fechner's later years, nor of the circumstances, cause, and manner of his death.

Fechner was the brother of painter Eduard Clemens Fechner and of Clementine Wieck Fechner, who was the stepmother of Clara Wieck when Clementine became her father Friedrich Wieck's second wife.

Works

- Praemissae ad theoriam organismi generalem ("Advances in the general theory of organisms") (1823).

- (Dr. Mises) Stapelia mixta (1824). Internet Archive (Harvard)

- Resultate der bis jetzt unternommenen Pflanzenanalysen ("Results of plant analyses undertaken to date") (1829). Internet Archive (Stanford)

- Maassbestimmungen über die galvanische Kette (1831).

- (Dr. Mises) Schutzmittel für die Cholera ("Protective equipment for cholera") (1832). Google (Harvard) — Google (UWisc)

- Repertorium der Experimentalphysik (1832). 3 volumes.

- Volume 1. Internet Archive (NYPL) — Internet Archive (Oxford)

- Volume 2. Internet Archive (NYPL) — Internet Archive (Oxford)

- Volume 3. Internet Archive (NYPL) — Internet Archive (Oxford)

- (ed.) Das Hauslexicon. Vollständiges Handbuch praktischer Lebenskenntnisse für alle Stände (1834–38). 8 volumes.

- Das Büchlein vom Leben nach dem Tode (1836). 6th ed., 1906. Internet Archive (Harvard) — Internet Archive (NYPL)

- (in English) On Life After Death (1882). Google (Oxford) — IA (UToronto) 2nd ed., 1906. Internet Archive (UMich) 3rd ed., 1914. IA (UIllinois)

- (in English) The Little Book of Life After Death (1904). IA (UToronto) 1905, Internet Archive (UCal) — IA (Ucal) — IA (UToronto)

- (Dr. Mises) Gedichte (1841). Internet Archive (Oxford)

- Ueber das höchste Gut ("Concerning the Highest Good") (1846). Internet Archive (Stanford)

- (Dr. Mises) Nanna oder über das Seelenleben der Pflanzen (1848). 2nd ed., 1899. 3rd ed., 1903. Internet Archive (UMich) 4th ed., 1908. Internet Archive (Harvard)

- Zend-Avesta oder über die Dinge des Himmels und des Jenseits (1851). 3 volumes. 3rd ed., 1906. Google (Harvard)

- Ueber die physikalische und philosophische Atomenlehre (1855). 2nd ed., 1864. Internet Archive (Stanford)

- Professor Schleiden und der Mond (1856). Google (UMich)

- Elemente der Psychophysik (1860). 2 volumes. Volume 1. Google (ULausanne) Volume 2. Internet Archive (NYPL)

- Ueber die Seelenfrage ("Concerning the Soul") (1861). Internet Archive (NYPL) — Internet Archive (UCal) — Internet Archive (UMich) 2nd ed., 1907. Google (Harvard)

- Die drei Motive und Gründe des Glaubens ("The three motives and reasons of faith") (1863). Google (Harvard) — Internet Archive (NYPL)

- Einige Ideen zur Schöpfungs- und Entwickelungsgeschichte der Organismen (1873). Internet Archive (UMich)

- (Dr. Mises) Kleine Schriften (1875). Internet Archive (UMich)

- Erinnerungen an die letzen Tage der Odlehre und ihres Urhebers (1876). Google (Harvard)

- Vorschule der Aesthetik (1876). 2 Volumes. Internet Archive (Harvard)

- In Sachen der Psychophysik (1877). Internet Archive (Stanford)

- Die Tagesansicht gegenüber der Nachtansicht (1879). Google (Oxford) 2nd ed., 1904. Internet Archive (Stanford)

- Revision der Hauptpuncte der Psychophysik (1882). Internet Archive (Harvard)

- Kollektivmasslehre (1897). Internet Archive (NYPL)

References

- "Gustav Fechner - German psychologist and physicist". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- Fancher, R. E. (1996). Pioneers of Psychology (3rd ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-96994-0.

- Sheynin, Oscar (2004), "Fechner as a statistician.", British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology (published May 2004), vol. 57, no. Pt 1, pp. 53–72, doi:10.1348/000711004849196, PMID 15171801

- Michael Heidelberger (2004). "1: Life and Work". Nature from within: Gustav Theodor Fechner and his Psychophysical Worldview. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 21. ISBN 9780822970774.

The study of medicine also contributed to a loss of religious faith and to becoming atheist.

- Beiser, Frederick C. "Gustav Theodor Fechner". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- Fechner, Gustav Theodor at vlp.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de.

- Meischner-Metge, Anneros. "Chronological table to the life of Gustav Theodor Fechner". Leipzig University. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- Boring, E. G. (1950). A history of experimental psychology (2nd ed.). (pp. 284-295) Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Sturt, Henry Cecil (1911). "Fechner, Gustav Theodor". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 231–232.

- Schultz, P.D., & Schultz, S.E. (2008). A History of Modern Psychology.(pp. 81-82).Thompson Wadsworth.

- Michael Heidelberger. "Gustav Theodor Fechner". /statprob.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- Keynes, John Maynard; A Treatise on Probability (1921), Pt II Ch XVII §5 (p 201).

- Fechner, G. (1876) Vorschule der Aesthetik. Leipzig: Breitkopf und Hartel. Website: chuoft.pdf

- Campen, Cretien van (1996). De verwarring der zintuigen. Artistieke en psychologische experimenten met synesthesie. Psychologie & Maatschappij, vol. 20, nr. 1, pp. 10–26.

- Galton F (1880). "Visualized Numerals". Nature. 21 (543): 494–5. doi:10.1038/021494e0.

- Galton F (1880). "Visualized Numerals". Nature. 21 (533): 252–6. doi:10.1038/021252a0.

- Galton F. (1883). Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development. Macmillan. Retrieved 2008-06-17.

- [Gazzinga, M.S (1970). The bisected brain. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts]

- Fechner, Gustav (1876). Vorschule der Ästhetik. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel. pp. 190–202.

- Livio, Mario (2002). The Golden Ratio: The Story of Phi, the World's Most Astonishing Number (1st ed.). New York: Broadway Books. ISBN 0-7679-0815-5. OCLC 49226115.

- Wallis, K.F. (2014). "The two-piece normal, binormal, or double Gaussian distribution: its origin and rediscoveries". Statistical Science, Vol. 29, No. 1, pp.106-112. DOI: 10.1214/13-STS417 arXiv:1405.4995

- Levelt, W. J. M. (1965). Binocular brightness averaging and contour information. British Journal of Psychology, 56, 1-13. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1965.tb00939.x

- Robinson, T. R. (1896). Light intensity and depth perception. American Journal of Psychology, 7, 518-532. https://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1411847

- Ding, J., & Levi, D. M. (2017). Binocular combination of luminance profiles. Journal of Vision, 17(13, 4), 1-32. https://dx.doi.org/10.1167/17.13.4

- Pojman, Paul, "Ernst Mach", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2011 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- Nicholls, Angus; Liebshcher, Martin (24 June 2010). Thinking the Unconscious: Nineteenth-Century German Thought. Cambridge University Press. p. 272. ISBN 9780521897532.

- Freud, Sigmund (18 March 2015). The Interpretation of Dreams. Translated by A. A. Brill. Mineola New York: Courier Dover Publications. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-486-78942-2.

- Sulloway, Frank J. (1979). Freud: Biologist of the Mind.(pp. 66-67). Basic Books.

- Marshall, M E (1969), "Gustav Fechner, Dr. Mises, and the comparative anatomy of angels.", Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences (published Jan 1969), vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 39–58, doi:10.1002/1520-6696(196901)5:1<39::AID-JHBS2300050105>3.0.CO;2-C, PMID 11610088

- For Hartshorne's appreciation of Fechner see his Aquinas to Whitehead – Seven Centuries of Metafysics of Religion. Hartshorne also comments that William James failed to do justice to the theological aspects of Fechner's work. Hartshorne saw also resemblances with the work of Fechner's contemporary Jules Lequier. See also: Hartshorne – Reese (ed.) Philosophers speak of God.

- Fechner, Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature, International Astronomical Union (IAU) Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature (WGPSN)

- Kreuger, L. E. (1993) Personal Communication. ref History of Psychology 4th edition David Hothersal 2004 ISBN 9780072849653

- "Fechner Day 2018 – The International Society for Psychophysics". www.ispsychophysics.org.

- "FECHNER DAY 2018". fechnerdays Webseite!. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- "Fechner Day 2017 — Welcome (index)". fechnerday.com. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

Further reading

- Heidelberger, M. (2001), "Gustav Theodor Fechner" in Statisticians of the Centuries (ed. C. C. Heyde and E. Seneta) pp. 142–147. New York: Springer Verlag, 2001.

- Heidelberger, M. (2004), Nature From Within: Gustav Theodor Fechner and his Psychophysical Worldview (trans. Cynthia Klohr), Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2004. ISBN 0-822-9421-00

- Robinson, David K. (2010), "Gustav Fechner: 150 years of Elemente der Psychophysik", in History of Psychology, Vol 13(4), Nov 2010, pp. 409–410. APA PsycNet

- Stigler, Stephen M. (1986), The History of Statistics: The Measurement of Uncertainty before 1900, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, pp. 242–254.

External links

Media related to Gustav Theodor Fechner at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gustav Theodor Fechner at Wikimedia Commons- Works by Gustav Theodor Fechner at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Gustav Fechner at Internet Archive

- William James on Fechner

- Works of Gustav Theodor Fechner at Projekt Gutenberg-DE. (German)

- Excerpt from Elements of Psychophysics from the Classics in the History of Psychology website.

- Robert H. Wozniak's Introduction to Elemente der Psychophysik.

- Biography, bibliography and digitized sources in the Virtual Laboratory of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science

- Granville Stanley 1912 'Founders of modern psychology p. 125ff archive.org

- Gustav Theodor Fechner 1904 The Little Book of Life after Death Foreword by William James

- Gustav Theodor Fechner 1908 The Living Word

- Gustav Theodor Fechner at statprob.com