H. H. Holmes

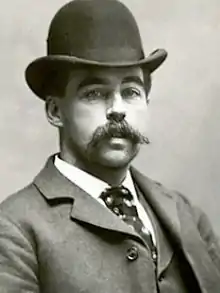

Herman Webster Mudgett (May 16, 1861 – May 7, 1896), better known as Dr. Henry Howard Holmes or H. H. Holmes, was an American con artist and serial killer, the subject of more than 50 lawsuits in Chicago alone. Until his execution in 1896, he chose a career of crime including insurance fraud, swindling; check forging; 3 to 4 bigamous illegal marriages; murder and horse theft.

H. H. Holmes | |

|---|---|

Mugshot of Holmes, c. 1895 | |

| Born | Herman Webster Mudgett May 16, 1861 Gilmanton, New Hampshire, U.S. |

| Died | May 7, 1896 (aged 34) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Other names | See aliases

|

| Alma mater |

|

| Spouses |

|

| Conviction(s) | First-degree murder |

| Criminal charge | Murder |

| Penalty | Death |

| Details | |

| Victims | 1 killed and confirmed 9 total suspected |

Span of crimes | 1891–1894 |

| Location(s) | Illinois, Indiana, Ontario, Pennsylvania |

Date apprehended | November 17, 1894 |

Despite his confession of 27 murders (including some people who were verifiably still alive) while awaiting execution,[1] Holmes was convicted and sentenced to death for only one murder, that of accomplice and business partner Benjamin Pitezel. It is believed he killed three of the Pitezel children, as well as 3 mistresses, the child of one of the said mistresses and the sister of another.[2] Holmes was executed on May 7, 1896, nine days before his 35th birthday.[3]

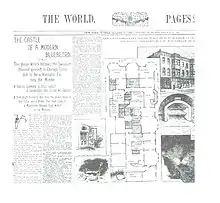

Much of the lore surrounding the "Murder Castle" along with many of his alleged crimes are considered likely exaggerated or fabricated for sensationalistic tabloid pieces. Many of these factual inaccuracies have persisted due to the combination of ineffective police investigation and hyperbolic tabloid journalism, which are often cited as historical record.[4] Holmes gave various contradictory accounts of his life, initially claiming innocence and later that he was possessed by Satan. His propensity for lying has made it difficult for researchers to ascertain the truth on the basis of his statements.[5]

Since the 1990s, Holmes has often been described as a serial killer, however, Adam Selzer points out in his book on Holmes, "Just killing several people isn't necessarily enough for most definitions [of a serial killer]. More often, it has to be a series of similar crimes, committed over a period of time, usually more to satisfy a psychological urge on the killer's part than any more practical motive." and "The murders we can connect him [Holmes] to generally had a clear motive: someone knew too much, or was getting in his way, and couldn't be trusted. The murders weren't simply for love of bloodshed but a necessary part of furthering his swindling operations and protecting his lifestyle."[6]

Early life

Holmes was born as Herman Webster Mudgett in Gilmanton, New Hampshire, on May 16, 1861, to Levi Horton Mudgett and Theodate Page Price, both of whom were descended from the first English immigrants in the area. Mudgett was his parents' third-born child; he had an older sister Ellen, an older brother Arthur, a younger brother Henry, and a younger sister Mary.[7][8] Holmes's father was from a farming family, and at times he worked as a farmer, trader, and house painter; his parents were devout Methodists.[9] Later attempts to fit Holmes into the patterns seen in modern serial killers have described him torturing animals and suffering from abuse at the hands of a violent father, but contemporary and eyewitness accounts of his childhood do not provide proof of either.[6]

At the age of 16, Holmes graduated from Phillips Exeter Academy and took teaching jobs in Gilmanton and later in nearby Alton. On July 4, 1878, he married Clara Lovering in Alton; their son, Robert Lovering Mudgett, was born on February 3, 1880, in Loudon, New Hampshire. Robert became a certified public accountant and served as city manager of Orlando, Florida.

Holmes enrolled in the University of Vermont in Burlington at age 18 but was dissatisfied with the school and left after one year. In 1882, he entered the University of Michigan's Department of Medicine and Surgery[10] and graduated in June 1884 after passing his exams.[11] While enrolled, he worked in the anatomy lab under Professor William James Herdman, then the chief anatomy instructor, and the two were said to have been engaged in facilitating grave robbing to supply medical cadavers.[12][13] Holmes had apprenticed in New Hampshire under Nahum Wight, a noted advocate of human dissection.[6] Years later, when Holmes was suspected of murder and claimed to be nothing but an insurance fraudster, he admitted to using cadavers to defraud life insurance companies several times in college.[6]

Housemates described Holmes as treating Clara violently, and in 1884, before his graduation, she moved back to New Hampshire and later wrote she knew little of him afterwards.[14] After he moved to Mooers Forks, New York, a rumor spread that Holmes had been seen with a little boy who later disappeared. Holmes claimed the boy went back to his home in Massachusetts. No investigation took place and Holmes quickly left town.[15]

He later traveled to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and got a job as a keeper at Norristown State Hospital, but quit after a few days. He later took a position at a drugstore in Philadelphia, but while he was working there, a boy died after taking medicine that was purchased at the store. Holmes denied any involvement in the child's death and immediately left the city. Right before moving to Chicago, he changed his name to Henry Howard Holmes to avoid the possibility of being exposed by victims of his previous scams.[15]

In his confession after his arrest, Holmes claimed he had killed his former medical school classmate, Robert Leacock, in 1886 for insurance money.[7] Leacock, however, died in Watford, Ontario, in Canada on October 5, 1889.[16] In late 1886, while still married to Clara, Holmes married Myrta Belknap (b. October 1862 in Pennsylvania)[17] in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He filed for divorce from Clara a few weeks after marrying Myrta, alleging infidelity on her part. The claims could not be proven and the suit went nowhere. Surviving paperwork indicated she probably was never even informed of the suit.[6] In any case, the divorce was never finalized;[18][19] it was dismissed June 4, 1891, on the grounds of "want of prosecution."[20]

Holmes had a daughter with Myrta, Lucy Theodate Holmes, who was born on July 4, 1889, in Englewood, Chicago, Illinois.[21] Lucy became a public schoolteacher. Holmes lived with Myrta and Lucy in Wilmette, Illinois, and spent most of his time in Chicago tending to business. Holmes married Georgiana Yoke on January 17, 1894, in Denver, Colorado,[18][22] while still married to both Clara and Myrta.[18]

Illinois and the Murder Castle

.jpg.webp)

Holmes arrived in Chicago in August 1886, which is when he began using the name H. H. Holmes.[23] He came across Elizabeth S. Holton's drugstore at the northwest corner of South Wallace Avenue and West 63rd Street in Englewood.[24] Holton gave Holmes a job, and he proved to be a hardworking employee, eventually buying the store. Although several books portray Holton's husband as an old man who quickly vanished along with his wife, Dr. Holton was a fellow Michigan alumnus, only a few years older than Holmes, and both Holtons remained in Englewood throughout Holmes's life and survived well into the 20th century; it is a myth that they were killed by Holmes.[6] Likewise, Holmes did not kill alleged "Castle" victim Miss Kate Durkee, who turned out to be very much alive.[25]

Holmes purchased an empty lot across from the drugstore, where construction began in 1887 for a two-story mixed-use building, with apartments on the second floor and retail spaces, including a new drugstore. A creditor of Holmes named John DeBrueil died of apoplexy on April 17, 1891, in the drugstore. When Holmes declined to pay the architects or the steel company, Aetna Iron and Steel, they sued in 1888.[6] In 1892, he added a third floor, telling investors and suppliers he intended to use it as a hotel during the upcoming World's Columbian Exposition, though the hotel portion was never completed. In 1892, the hotel was somewhat completed, with three stories and a basement. The ground floor was the storefront.[26]

Fictionalized accounts report that Holmes constructed the hotel to lure in tourists visiting the nearby World's Fair in order to murder them and sell their skeletons to medical schools. There is no evidence that Holmes ever tried to lure strangers into his hotel to murder them. In fact, none of his likely victims were strangers. Holmes did have a history of selling cadavers to medical schools. However, he acquired his wares through grave-robbing rather than murder.[4]

Reports by the yellow press labeled the building as Holmes's "Murder Castle", claiming the structure contained secret torture chambers, trap doors, gas chambers and a basement crematorium; none of these claims were true.[27] Other accounts claim that the hotel was made up of over a hundred rooms and laid out like a maze, with doors opening into brick walls, windowless rooms and dead-end staircases. In reality, the hotel floor was moderately sized and largely unremarkable. It did contain some hidden rooms, but they were used for hiding furniture Holmes bought on credit and did not intend to pay for.[4]

The hotel was gutted by a fire started by an unknown arsonist shortly after Holmes was arrested but was largely rebuilt and used as a post office until 1938.[28] Besides his infamous "Murder Castle", Holmes also had a one-story factory which he claimed was to be used for glass bending. It is unclear if the factory furnace was ever used for glass bending; it was speculated to have been used to destroy incriminating evidence of Holmes's crimes.[29]

Early victims

.jpg.webp)

.pdf.jpg.webp)

One of Holmes's early victims was his mistress, Julia Smythe. She was the wife of Ned (Icilius) Conner, who had moved into Holmes's building and began working at his pharmacy's jewelry counter. After Conner found out about Smythe's affair with Holmes, he quit his job and moved away, leaving Smythe and her daughter Pearl behind. Smythe gained custody of Pearl and remained at the hotel, continuing her relationship with Holmes.[6]

Julia and Pearl disappeared on Christmas Eve of 1891, and Holmes later claimed she had died during an abortion. Despite his medical background, Holmes was unlikely to be experienced in carrying out abortions, and mortality from such a procedure was high at that time. Holmes claimed to have poisoned Pearl, likely to hide the circumstances of her mother's death. A partial skeleton, possibly of a child around Pearl's age was found when excavating Holmes's cellar. Pearl's father, Ned, was a key witness at Holmes's trial in Chicago.[4]

Emeline Cigrande began working in the building in May 1892, and disappeared that December.[1] Rumors following her disappearance claimed she had gotten pregnant by Holmes, possibly being a victim of another failed abortion that Holmes tried to cover up.[4]

Another young girl who had worked for Holmes in his building named Emily Van Tassel "vanished", too.[30][31]

While working in the Chemical Bank building on Dearborn Street, Holmes met and became close friends with Benjamin Pitezel, a carpenter with a criminal past who was exhibiting, in the same building, a coal bin he had invented.[6] Holmes used Pitezel as his right-hand man for several criminal schemes. A district attorney later described Pitezel as "Holmes's tool... his creature."[32]

In early 1893, a one-time actress named Minnie Williams moved to Chicago. Holmes claimed to have met her in an employment office, though there were rumors he had met her in Boston years earlier. He offered her a job at the hotel as his personal stenographer and she accepted. Holmes persuaded Williams to transfer the deed to her property in Fort Worth, Texas, to a man named Alexander Bond (an alias of Holmes).[6]

In April 1893, Williams transferred the deed, with Holmes serving as the notary (Holmes later signed the deed over to Pitezel, giving him the alias "Benton T. Lyman"). The next month, Holmes and Williams, presenting themselves as husband and wife, rented an apartment in Chicago's Lincoln Park. Minnie's sister, Annie, came to visit, and in July, she wrote to her aunt that she planned to accompany "Brother Harry" to Europe. Neither Minnie nor Annie were seen alive after July 5, 1893.[6]

Although not proven Holmes was suspected of killing six other persons who vanished between 1891 and 1895. Dr. Russler, who had an office in the "Castle", went missing in 1892.[33] Kitty Kelly, a stenographer for Holmes, also went missing in 1892.[34] John G. Davis of Greenville, Pennsylvania, went to visit the 1893 "World's Fair" and vanished. In 1920 his daughter asked that he be declared legally dead.[35] Henry Walker of Greensburg, Indiana, who went missing in November 1893, was alleged to have insured his life to Holmes for $20,000 and wrote to friends that he was working for Holmes in Chicago.[36] Milford Cole of Baltimore, Maryland, was alleged to have disappeared after receiving a telegram from Holmes to come to Chicago in July 1894.[31] An otherwise unknown victim was a Lucy Burbank; her bankbook was found in the "castle" in 1895.[37]

Pitezel murders

With insurance companies pressing to prosecute him for arson, Holmes left Chicago in July 1894. He reappeared in Fort Worth, where he had inherited property from the Williams sisters, at the intersection of modern-day Commerce Street and 2nd Street. Here, he once again attempted to build an incomplete structure without paying his suppliers and contractors. This building was not a site of any additional killings.[38]

In July 1894, Holmes was arrested and briefly jailed for the first time, on the charge of selling mortgaged goods in St. Louis, Missouri.[39] He was promptly bailed out, but while in jail he struck up a conversation with a convicted outlaw named Marion Hedgepeth, who was serving a 25-year sentence. Holmes had concocted a plan to swindle an insurance company out of $10,000 by taking out a policy on himself and then faking his death.[5]

Holmes promised Hedgepeth a $500 commission in exchange for the name of a lawyer who could be trusted. Holmes was directed to a young St. Louis attorney named Jeptha Howe. Howe thought Holmes's scheme was brilliant, and agreed to play a part. Nevertheless, Holmes's plan to fake his own death failed when the insurance company became suspicious and refused to pay. Holmes did not press the claim; instead, he concocted a similar plan with Pitezel.[5]

Pitezel agreed to fake his own death so that his wife could collect on a $10,000 life insurance policy,[5] which she was to split with Holmes and Howe. The scheme, which was to take place in Philadelphia, called for Pitezel to set himself up as an inventor under the name B.F. Perry, and then be killed and disfigured in a lab explosion. Holmes was to find an appropriate cadaver to play the role of Pitezel. Instead, Holmes killed Pitezel by knocking him unconscious with chloroform and setting his body on fire with the use of benzene. In his confession, Holmes implied Pitezel was still alive after he used the chloroform on him, before he set him on fire. However, forensic evidence presented at Holmes's later trial showed chloroform had been administered after Pitezel's death (a fact of which the insurance company was unaware), presumably to fake suicide to exonerate Holmes should he be charged with murder.[1][5]

Holmes collected the insurance payout on the basis of the genuine Pitezel corpse. Holmes then went on to manipulate Pitezel's unsuspecting wife into allowing three of her five children (Alice, Nellie and Howard) to be placed in his custody. The eldest daughter and the baby remained with Mrs. Pitezel. Holmes and the three Pitezel children traveled throughout the northern United States and into Canada. Simultaneously, he escorted Mrs. Pitezel along a parallel route, all the while using various aliases and lying to Mrs. Pitezel concerning her husband's death (claiming Pitezel was hiding in London),[5][40] as well as lying to her about the true whereabouts of her three missing children. In Detroit, just before entering Canada, they were only separated by a few blocks.[41]

In an even more audacious move, Holmes was staying at another location with his wife, who was unaware of the whole affair. Holmes later confessed to murdering Alice and Nellie by forcing them into a large trunk and locking them inside. He drilled a hole in the lid of the trunk and put one end of a hose through the hole, attaching the other end to a gas line to asphyxiate the girls. Holmes buried their nude bodies in the cellar of his rental house at 16 St. Vincent Street in Toronto.[5][42] This home and address no longer exist, St. Vincent Street having long since been realigned into a part of Bay Street.

Frank Geyer, a Philadelphia police detective assigned to investigate Holmes and find the three missing children, found the decomposed bodies of the two Pitezel girls in the cellar of the Toronto home. Detective Geyer wrote, "The deeper we dug, the more horrible the odor became, and when we reached the depth of three feet, we discovered what appeared to be the bone of the forearm of a human being."[43] Geyer then went to Indianapolis, where Holmes had rented a cottage. Holmes was reported to have visited a local pharmacy to purchase the drugs which he used to kill young Howard Pitezel, and a repair shop to sharpen the knives he used to chop up the body before he burned it. The boy's teeth and bits of bone were discovered in the home's chimney.[5][44]

Capture, arrest, trial, and execution

Holmes's murder spree finally ended when he was arrested in Boston on November 17, 1894, after being tracked there from Philadelphia by the private Pinkerton National Detective Agency. He was held on an outstanding warrant for horse theft in Texas because the authorities had become more suspicious at this point and Holmes appeared poised to flee the country in the company of his unsuspecting third wife.[5][45]

In July 1895, following the discovery of Alice and Nellie's bodies, Chicago police and reporters began investigating Holmes's building in Englewood, now locally referred to as The Castle. Though many sensational claims were made, no evidence was found which could have convicted Holmes in Chicago.[5] According to Selzer, stories of torture equipment found in the building are 20th-century fiction.[6]

In October 1895, Holmes was put on trial for the murder of Benjamin Pitezel, and was found guilty and sentenced to death. By then, it was evident Holmes had also murdered the three missing Pitezel children. Following his conviction, Holmes confessed to 27 murders in Chicago, Indianapolis, and Toronto (though some people he "confessed" to murdering were still alive), and six attempted murders. Holmes was paid $7,500[1] by the Hearst newspapers in exchange for his confession, which was quickly found to be mostly nonsense.[46]

While writing his confessions in prison, Holmes mentioned how drastically his facial appearance had changed since his imprisonment.[5]

On May 7, 1896, Holmes was hanged at Moyamensing Prison, also known as the Philadelphia County Prison, for the murder of Pitezel.[1][47] Until the moment of his death, Holmes remained calm and amiable, showing very few signs of fear, anxiety, or depression.[48] Despite this, he asked for his coffin to be contained in cement and buried 10 feet deep, because he was concerned grave robbers would steal his body and use it for dissection.[1][10] Holmes's neck did not break; he instead strangled to death slowly, twitching for over 15 minutes before being pronounced dead 20 minutes after the trap had been sprung.[47][49]

Upon his execution, Holmes's body was interred in an unmarked grave at Holy Cross Cemetery, a Catholic cemetery in the Philadelphia Western suburb of Yeadon, Pennsylvania.

On New Year's Eve 1909, Hedgepeth, who had been pardoned for informing on Holmes,[1] was shot and killed by police officer Edward Jaburek during a holdup at a Chicago saloon.[50]

On March 7, 1914, the Chicago Tribune reported that, with the death of Patrick Quinlan, the former caretaker of the castle, "the mysteries of Holmes's castle" would remain unexplained. Quinlan had committed suicide by taking strychnine. His body was found in his bedroom with a note that read, "I couldn't sleep."[51] Quinlan's surviving relatives claimed he had been "haunted" for several months and was suffering from hallucinations.[18]

The castle itself was mysteriously gutted by fire in August 1895. According to a newspaper clipping from The New York Times, two men were seen entering the back of the building between 8 and 9 p.m. About half an hour later, they were seen exiting the building and rapidly running away. Following several explosions, the castle went up in flames. Afterwards, investigators found a half-empty gas can underneath the back steps of the building. The building survived the fire and remained in use until it was torn down in 1938. The site is occupied by the Englewood branch of the United States Postal Service.[52]

In 2017, amid allegations Holmes had in fact escaped execution, Holmes's body was exhumed for testing led by Janet Monge of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Due to his coffin being contained in cement, his body was found not to have decomposed normally. His clothes were almost perfectly preserved and his mustache was found to be intact. The body was positively identified by his teeth as being that of Holmes. Holmes was then reburied.[53]

.jpg.webp) H. H. Holmes's mugshot (1895)

H. H. Holmes's mugshot (1895) Benjamin Pitezel

Benjamin Pitezel.jpg.webp) Execution of H. H. Holmes (Moyamensing Prison, Philadelphia, 1896)

Execution of H. H. Holmes (Moyamensing Prison, Philadelphia, 1896)

In popular culture

The case was notorious in its time and received wide publicity in the international press. Depraved: The Shocking True Story of America's First Serial Killer by Harold Schechter (1994), was the first major book on Holmes to characterize him as a serial killer.

Interest in Holmes's crimes was revived in 2003 by Erik Larson's The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair That Changed America, a best-selling nonfiction book that juxtaposed an account of the planning and staging of the World's Fair with a fictionalized version of Holmes's story. His story had been chronicled in The Torture Doctor by David Franke (1975), The Scarlet Mansion by Allan W. Eckert (1985), as well as "The Monster of Sixty-Third Street" chapter in Gem of the Prairie: An Informal History of the Chicago Underworld by Herbert Asbury (1940, republished 1986).

The 1974 novel American Gothic by horror writer Robert Bloch was a fictionalized version of the story of H. H. Holmes.[54]

Selzer's comprehensive 2017 biography, H. H. Holmes: The True History of the White City Devil, attempted to separate fact from fiction, and to trace how the story grew.[55]

In 2017, History aired an eight episode limited docuseries entitled American Ripper, in which Holmes's great-great-grandson, Jeff Mudgett, along with former CIA analyst Amaryllis Fox, investigated clues to attempt to prove that Holmes was also the infamous London serial killer, Jack the Ripper.[56]

In 2018, horror writer Sara Tantlinger published The Devil's Dreamland: Poetry Inspired by H.H. Holmes (Strangehouse Books) which won the 2018 Bram Stoker Award for Best Poetry Collection.[57]

In 2015, a film adaptation of The Devil in the White City, starring Leonardo DiCaprio and directed by Martin Scorsese, was to begin filming but never got off the ground. In 2019, Scorsese and DiCaprio were executive producers in a television version released by Paramount TV and Hulu.[58]

Supermassive Games is set to release the fourth entry in their Dark Pictures Anthology video game series titled, The Devil in Me which is inspired by H. H. Holmes and the Murder Castle which will be released on November 18, 2022. [59]

See also

- Insurable interest

- Insurance fraud

- List of serial killers by country

- List of serial killers in the United States

References

Citations

- JD Crighton; Herman W. Mudgett MD (2017). Holmes' Own Story: Confessed 27 Murders, Lied, then Died. Aerobear Classics. pp. 87–90. ISBN 978-1-946100-00-9.

- Herman W. Mudgett (1897). The Trial of Herman W. Mudgett, Alias H.H. Holmes, for the Murder of Benjamin F. Pitezel: In the Court of Oyer and Terminer and General Jail Delivery and Quarter Sessions of the Peace, in and for the City and County of Philadelphia, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania ... 1895. Bisel.

- Scott Patrick Johnson (2011). Trials of the Century: An Encyclopedia of Popular Culture and the Law. ABC-CLIO. pp. 173–174. ISBN 978-1-59884-261-6.

- Selzer, Adam (2017). H.H. Holmes : the true history of the White City Devil. New York, NY. ISBN 978-1-5107-1343-7.

- Crighton, JD (2017). Detective in the White City: The Real Story of Frank Geyer. Murrieta, CA: RW Publishing House. pp. 136–208. ISBN 978-1-946100-02-3.

- Selzer, Adam (2017). HH Holmes: The True History of the White City Devil. Skyhorse. ISBN 978-1-5107-1343-7.

- Kerns, Rebecca; Lewis, Tiffany; McClure, Caitlin (2012). "Herman Webster Mudgett: 'Dr. H.H Holmes or Beast of Chicago'" (PDF). Department of Psychology, Radford University. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 29, 2015. Retrieved May 22, 2015.

- New Hampshire Registrar of Vital Statistics. "Index to births, early to 1900", Registrar of Vital Statistics, Concord, New Hampshire. FHL Microfilms: film number 1001018

- Erik Larson (September 30, 2010). The Devil In The White City. Transworld. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-4090-4460-4. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- Glenn, Alan (October 22, 2013). "A double dose of the macabre". Michigan Today. Ann Arbor: Regents of the University of Michigan. Archived from the original on June 21, 2016. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- Larson, Erik (September 30, 2010). The Devil In The White City. Transworld. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-4090-4460-4. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- Dr. Henry H. Holmes at the University of Michigan, Part Two, Martin Hill Ortiz, March 2016. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- In the Archives: The Friendless Dead, Ann Arbor Chronicle, October 1, 2013. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- Letter from Clara Mudgett to Dr. Arthur MacDonald, 1896)

- H. H. Holmes: America's First Serial Killer documentary

- University of Michigan (July 9, 2017). "General Catalogue of Officers and Students and Supplements Containing Death Notices". The University. – via Google Books.; Mudgett {class of 1884} is also listed as deceased 1896 on the same page as Leacock

- "Person Details for M B Holmes in household of Jno A Ripley, "United States Census, 1900"". FamilySearch. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

- Schechter 1994

- "New Hampshire, Marriage and Divorce Records, 1659–1947 for Clara A Mudgett". Ancestry.com. Ancestry.com Operations, Inc. October 29, 1906. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 8, 2016.

- Courts, Pennsylvania (July 9, 1895). "The District Reports of Cases Decided in All the Judicial Districts of the State of Pennsylvania". H. W. Page. – via Google Books.

- Lucy Theodate Holmes, passport application, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795–1925 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: The Generations Network, Inc., 2007. Original data: Passport Applications, January 2, 1906–IMarch 31, 1925; (National Archives Microfilm Publication M1490, 2740 rolls); General Records of the Department of State, Record Group 59; National Archives, Washington, D.C.

- "Colorado Statewide Marriage Index, 1853–2006", index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/KNQH-NNX Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine : accessed December 16, 2014), Henry M Howard and Georgiana Yoke, January 17, 1894, Denver, Colorado, United States; citing p. 16256, State Archives, Denver; FHL microfilm 1,690,090 .

- "H.H. Holmes | Biography & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on October 10, 2019. Retrieved November 17, 2019.

- "The Strange Life of H. H. Holmes". by Debra Pawlak. The Mediadrome. 2002. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved January 3, 2011.

- "The morning call. (San Francisco [Calif.]) 1878–1895, November 23, 1894, Image 1". The Morning Call. November 23, 1894. ISSN 1946-6145. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- "Murder Castle". Archived from the original on February 14, 2019. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- Little, Becky. "Did Serial Killer H.H. Holmes Really Build a 'Murder Castle'?". HISTORY. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- "The Holmes Castle". 2008. Archived from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- "Excavating the H.H. Holmes "Body Dump" Site – Mysterious Chicago Tours". mysteriouschicago.com. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- The Sun August 4, 1895 p.4

- "The Indianapolis journal., July 29, 1895, Image 1 [Library of Congress]". July 29, 1895.

- Larson, Erik, "The Devil in the White City", Crown Publishers, 2003, p. 68, 70

- "Evening star. (Washington, D.C.) 1854-1972, July 29, 1895, Image 2". Evening Star. July 29, 1895. p. 2. ISSN 2331-9968. Retrieved July 22, 2017.

- "The San Francisco call., July 25, 1895, Image 1 [Library of Congress]". July 25, 1895.

- The Pittsburgh Press July 12,1920 .p.16 accessed November 15,2018

- "The Indianapolis journal., August 01, 1895, Image 1 [Library of Congress]". August 1895.

- "The San Francisco call., July 22, 1895, Page 2, Image 2 [Library of Congress]". July 22, 1895. p. 2.

- Smith, Chris Silver (May 7, 2012). "Locating the Site of H. H. Holmes's "Murder Castle" in Fort Worth, Texas". Nodal Bits. Nodal Bits. Archived from the original on January 13, 2019. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

- "St. Louis Post-Dispatch". July 19, 1894. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 5, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- The Devil in the White City by Erik Larson

- Geyer, Detective Frank P. "The Holmes-Pitezel case; a history of the Greatest Crime of the Century", Publishers' Union (1896), pg. 212

- Geyer "The Holmes-Pitezel case", pg. 213

- Geyer, Frank P. (1896). The Holmes-Pitezel case: a history of the greatest crime of the century and of the search for the missing Pitezel children. Philadelphia, PA: Publishers' Union. p. 231.

- Lloyd, Christopher (October 24, 2008). "Grisly Indy". The Indianapolis Star.

- Holmes was thus simultaneously moving three groups of people across the country, each ignorant of the other groups.

- "The Straight Dope: Did Dr. Henry Holmes kill 200 people at a bizarre "castle" in 1890s Chicago?". straightdope.com. July 6, 1979. Archived from the original on March 17, 2010. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- Ramsland. "H. H. Holmes: Master of Illusion". Crime Library. Archived from the original on May 21, 2013. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

On May 7, 1896, H. H. Holmes went to the hangman's noose. His last meal was boiled eggs, dry toast and coffee. Even at the noose, he changed his story. He claimed to have killed only two people, and tried to say more, but at 10:13 a.m., the trapdoor opened and he was hanged. Blundell stated that it took 15 minutes for Holmes to strangle to death on the gallows.

- Franke, D. (1975). The Torture Doctor. New York: Avon. ISBN 978-0-8015-7832-8.

- "Holmes Cool to the End". The New York Times. May 9, 1896. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

Under the Noose He Says He Only Killed Two Women. He denies the Murder of Pitezel. Slept Soundly Through His Last Night on Earth and Was Calm on the Scaffold. Priests with him on the Gallows. Prayed with Him Before the Trap Was Sprung. Dead in Fifteen Minutes, but Neck Was Not Broken. Murderer Herman Mudgett, alias H. H. Holmes, was hanged this morning in the County Prison for the killing of Pitezel. The drop fell at 10:12 o'clock, and twenty minutes later he was pronounced dead.

- Marion Hedgespeth death certificate, Cook County Coroner, #31295 dated January 11, 1910.

- Patrick B. Quinlan, death certificate, March 4, 1914, Portland, Ionia, Michigan. Digital image of death certificate Archived July 9, 2012, at archive.today

- The Backyard Traveler (April 6, 2010). "Exploring Illinois by Rich Moreno: The Site of the Infamous Murder Castle". exploringillinois.blogspot.com. Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

- "Exhumation confirms gravesite of notorious Chicago serial killer H.H. Holmes". Chicago Tribune. Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 3, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- Robert Bloch. "AMERICAN GOTHIC". Kirkus Reviews. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- "Nonfiction Book Review: H.H. Holmes: The True History of the White City Devil by Adam Selzer. Skyhorse, $26.99 (460p) ISBN 978-1-5107-1343-7". April 2017. Archived from the original on April 12, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- "American Ripper". Retrieved July 5, 2020.

- "2018 Bram Stoker Awards Winners & Nominees". The Bram Stoker Awards. April 13, 2018. Archived from the original on November 5, 2019. Retrieved September 3, 2019.

- Greene, Steve (February 11, 2019). "Leonardo DiCaprio and Martin Scorsese's 'Devil in the White City' was released in 2019 as a Hulu Series". IndieWire. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- Moss, Gabriel (August 26, 2022). "The Dark Pictures Anthology: The Devil In Me - First-Look Preview". IGN. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

General bibliography

- Asbury, Hebert (1986) [1940]. Gem of the Prairie: An Informal History of the Chicago Underworld. DeKalb, Illinois: Northern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-87580-534-4.

- Crighton, J. D. (2017). Detective in the White City: The Real Story of Frank Geyer. Murrieta, California: RW Publishing House. ISBN 978-1-946100-02-3.

- Crighton, J. D. (January 2017). Holmes' Own Story: Confessed 27 Murders—Lied Then Died. Murrieta, California: Aerobear Classics, an imprint of Aerobear Press. ISBN 978-1-946100-01-6.

- Larson, Erik (February 2004). The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair That Changed America. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-375-72560-9.

- Schechter, Harold (1994). Depraved: The Definitive True Story of H. H. Holmes, Whose Grotesque Crimes Shattered Turn-of-the-Century Chicago. New York: Pocket Books. ISBN 978-0-671-02544-1. OCLC 607738864, 223220639.

- Selzer, Adam (2017). HH Holmes: The True History of the White City Devil. New York: Skyhorse. ISBN 978-1-5107-1343-7.

Further reading

- Borowski, John (November 2005). Estrada, Dimas (ed.). The Strange Case of Dr. H. H. Holmes. West Hollywood, California: Waterfront Productions. ISBN 978-0-9759185-1-7.

- Franke, David (1975). The Torture Doctor. New York: Avon. ISBN 978-0-380-00730-1.

- Geary, Rick (2003). The Beast of Chicago: An Account of the Life and Crimes of Herman W. Mudgett, Known to the World as H. H. Holmes. New York: NBM Publishing. ISBN 978-1-56163-365-4.

- Mudgett, Jeff (April 2009). Bloodstains. U.S.: ECPrinting.com & Justin Kulinski. ISBN 978-0-615-40326-7.

External links

- "Modern Bluebeard: H. H. Holmes's Castles (sic) Reveals His True Character". Chicago Tribune. August 18, 1895: 40.

- Pennsylvania State Reports Volume 174 on Mughett's trial in death of Benjamin Pitzel 1896

- "The Master of Murder Castle: A Classic of Chicago Crime" John Bartlow Martin. Harper's Weekly. December 1943: 76–85.

- The Twenty-Seven Murders of H. H. Holmes Discussion of Holmes's confession of 27 murders

- Holmes's Own Story (1895) by Mudgett, Herman W.

- Works by H. H. Holmes at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)