Henry IV of France

Henry IV (French: Henri IV; 13 December 1553 – 14 May 1610), also known by the epithets Good King Henry or Henry the Great, was King of Navarre (as Henry III) from 1572 and King of France from 1589 to 1610. He was the first monarch of France from the House of Bourbon, a cadet branch of the Capetian dynasty. He was assassinated in 1610 by François Ravaillac, a Catholic zealot, and was succeeded by his son Louis XIII.

| Henry IV | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

_-_Henri_IV%252C_King_of_France_(1553-1610)_-_RCIN_402972_-_Royal_Collection.jpg.webp) Portrait by Frans Pourbus the Younger, 1610 | |||||

| King of France (more...) | |||||

| Reign | 2 August 1589 – 14 May 1610 | ||||

| Coronation | 27 February 1594 Chartres Cathedral | ||||

| Predecessor | Henry III | ||||

| Successor | Louis XIII | ||||

| King of Navarre | |||||

| Reign | 9 June 1572 – 14 May 1610 | ||||

| Predecessor | Jeanne III | ||||

| Successor | Louis II | ||||

| Born | 13 December 1553 Pau, Kingdom of Navarre | ||||

| Died | 14 May 1610 (aged 56) Paris, Kingdom of France | ||||

| Burial | 1 July 1610 Basilica of St Denis, Paris, France | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue |

Illegitimate:

| ||||

| |||||

| House | Bourbon | ||||

| Father | Antoine of Navarre | ||||

| Mother | Jeanne III of Navarre | ||||

| Religion | Calvinism 1553–1595 Catholicism 1595–1610 | ||||

| Signature |  | ||||

| Cause of death | Assassination | ||||

| Royal styles of King Henry IV Par la grâce de Dieu, Roi de France et de Navarre | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Most Christian Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Most Christian Majesty |

| Alternative style | Sire |

The son of Antoine de Bourbon, Duke of Vendôme and Jeanne d'Albret, the Queen of Navarre, Henry was baptised as a Catholic but raised in the Protestant faith by his mother. He inherited the throne of Navarre in 1572 on his mother's death. As a Huguenot, Henry was involved in the French Wars of Religion, barely escaping assassination in the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre. He later led Protestant forces against the royal army.

Henry and his predecessor Henry III of France were direct descendants of King Louis IX. Henry III belonged to the House of Valois, descended from Philip III of France, elder son of Saint Louis; Henry IV belonged to the House of Bourbon, descended from Robert, Count of Clermont, younger son of Saint Louis. As Head of the House of Bourbon, Henry was "first prince of the blood". Upon the death of his brother-in-law and distant cousin Henry III in 1589, Henry was called to the French succession by the Salic law.

He initially kept the Protestant faith (the only French king to do so) and had to fight against the Catholic League, which denied that he could wear France's crown as a Protestant. After four years of stalemate, he converted to Catholicism to obtain mastery over his kingdom (reportedly saying, "Paris is well worth a mass"). As a pragmatic politician (in the parlance of the time, a politique), he promulgated the Edict of Nantes (1598), which guaranteed religious liberties to Protestants, thereby effectively ending the French Wars of Religion.

An active ruler, Henry worked to regularise state finance, promote agriculture, eliminate corruption and encourage education. During his reign, the French colonization of the Americas truly began with the foundation of the colonies of Acadia and Canada at Port-Royal and Quebec, respectively. He is celebrated in the popular song "Vive le roi Henri" (which later became an anthem for the French monarchy during the reigns of his successors) and in Voltaire's Henriade.

Early life and King of Navarre

Childhood and adolescence

Henry de Bourbon was born in Pau, the capital of the joint Kingdom of Navarre with the sovereign principality of Béarn.[1] His parents were Queen Joan III of Navarre (Jeanne d'Albret) and her husband, Antoine de Bourbon, Duke of Vendôme, King of Navarre.[2] Although baptised as a Catholic, Henry was raised as a Protestant by his mother,[3] who had declared Calvinism the religion of Navarre. As a teenager, Henry joined the Huguenot forces in the French Wars of Religion. On 9 June 1572, upon his mother's death, the 19-year-old became King of Navarre.[4]

First marriage and Saint Bartholomew's Day Massacre

At Queen Joan's death, it was arranged for Henry to marry Margaret of Valois, daughter of Henry II of France and Catherine de' Medici. The wedding took place in Paris on 18 August 1572 on the parvis of Notre Dame Cathedral.[5]

On 24 August, the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre began in Paris. Several thousand Protestants who had come to Paris for Henry's wedding were killed, as well as thousands more throughout the country in the days that followed. Henry narrowly escaped death thanks to the help of his wife and his promise to convert to Catholicism. He was forced to live at the court of France, but he escaped in early 1576. On 5 February of that year, he formally abjured Catholicism at Tours and rejoined the Protestant forces in the military conflict.[4] He named his 16-year-old sister, Catherine de Bourbon, regent of Béarn. Catherine held the regency for nearly thirty years.

Wars of Religion

Henry became heir presumptive to the French throne in 1584 upon the death of Francis, Duke of Anjou, brother and heir to the Catholic Henry III, who had succeeded Charles IX in 1574. Given that Henry of Navarre was the next senior agnatic descendant of King Louis IX, King Henry III had no choice but to recognise him as the legitimate successor.[6]

War of the Three Henrys (1587–1589)

- King Henry III of France, supported by the royalists and the politiques;

- King Henry of Navarre, heir presumptive to the French throne and leader of the Huguenots, supported by Elizabeth I of England and the Protestant princes of Germany; and

- Henry of Lorraine, Duke of Guise, leader of the Catholic League, funded and supported by Philip II of Spain.

Salic law barred the king's sisters and all others who could claim descent through only the female line from inheriting. Since Henry of Navarre was a Huguenot, the issue was not considered settled in many quarters of the country, and France was plunged into a phase of the Wars of Religion known as the War of the Three Henrys (1587–1589).

Henry I, Duke of Guise pushed for complete suppression of the Huguenots and had much support among Catholic loyalists. Political disagreements among the parties set off a series of campaigns and counter-campaigns that culminated in the Battle of Coutras.[7]

In December 1588, Henry III had Henry I of Guise murdered,[8] along with his brother, Louis, Cardinal de Guise.[9] Henry III thought the removal of the brothers would finally restore his authority. However, the populace was horrified and rose against him. The title of the king was no longer recognized in several cities; his power was limited to Blois, Tours, and the surrounding districts. In the general chaos, Henry III relied on King Henry of Navarre and his Huguenots.

The two kings were united by a common interest—to win France from the Catholic League. Henry III acknowledged the King of Navarre as a true subject and Frenchman, not a fanatic Huguenot aiming for the destruction of Catholics. Catholic royalist nobles also rallied to the king's standard. With this combined force, the two kings marched to Paris. The morale of the city was low, and even the Spanish ambassador believed the city could not hold out longer than a fortnight. However, Henry III was assassinated shortly thereafter, on 2 August 1589, by a monk.[10]

King of France: Early reign

Succession (1589–1594)

When Henry III died, Henry of Navarre nominally became king of France. The Catholic League, however, strengthened by support from outside the country—especially from Spain—was strong enough to prevent a universal recognition of his new title. Pope Sixtus V excommunicated Henry and declared him devoid of any right to inherit the crown.[11] Most of the Catholic nobles who had joined Henry III for the siege of Paris also refused to recognize the claim of Henry of Navarre, and abandoned him. He set about winning his kingdom by military conquest, aided by English money and German troops. Henry's Catholic uncle Charles, Cardinal de Bourbon was proclaimed king by the League, but the Cardinal was Henry's prisoner at the time.[12] Henry was victorious at the Battle of Arques and the Battle of Ivry, but failed to take Paris after besieging it in 1590.[13]

When Cardinal de Bourbon died in 1590, the League could not agree on a new candidate. While some supported various Guise candidates, the strongest candidate was probably the Infanta Isabella Clara Eugenia of Spain, the daughter of Philip II of Spain, whose mother Elisabeth had been the eldest daughter of Henry II of France.[14] In the religious fervor of the time, the Infanta was recognized to be a suitable candidate, provided that she marry a suitable husband. The French overwhelmingly rejected Philip's first choice, Archduke Ernest of Austria, the Emperor's brother, also a member of the House of Habsburg. In case of such opposition, Philip indicated that princes of the House of Lorraine would be acceptable to him: the Duke of Guise; a son of the Duke of Lorraine; and the son of the Duke of Mayenne. The Spanish ambassadors selected the Duke of Guise, to the joy of the League. However, at that moment of seeming victory, the envy of the Duke of Mayenne was aroused, and he blocked the proposed election of a king.

The Parlement of Paris also upheld the Salic law. They argued that if the French accepted natural hereditary succession, as proposed by the Spaniards, and accepted a woman as their queen, then the ancient claims of the English kings would be confirmed, and the monarchy of centuries past would be nothing but an illegality.[15] The Parlement admonished Mayenne, as lieutenant-general, that the kings of France had resisted the interference of the pope in political matters, and that he should not raise a foreign prince or princess to the throne of France under the pretext of religion. Mayenne was angered that he had not been consulted prior to this admonishment, but yielded, since their aim was not contrary to his present views.

Despite these setbacks for the League, Henry remained unable to take control of Paris.

Conversion to Catholicism: "Paris is well worth a Mass" (1593)

On 25 July 1593, with the encouragement of his mistress, Gabrielle d'Estrées, Henry permanently renounced Protestantism and converted to Catholicism in order to secure his hold on the French crown, thereby earning the resentment of the Huguenots and his former ally Queen Elizabeth I of England. He was said to have declared that Paris vaut bien une messe ("Paris is well worth a mass"),[16][17][18] although there is some doubt whether he said this, or whether the statement was attributed to him by his contemporaries.[19][20] His acceptance of Catholicism secured the allegiance of the vast majority of his subjects.

Coronation and recognition (1594–1595)

Since Reims, traditional coronation place of French kings, was still occupied by the Catholic League, Henry was crowned King of France at the Cathedral of Chartres on 27 February 1594.[21] Pope Clement VIII lifted excommunication from Henry on 17 September 1595.[22] He did not forget his former Calvinist coreligionists, however, and was known for his religious tolerance. In 1598 he issued the Edict of Nantes, which granted circumscribed toleration to the Huguenots.[23]

Civil war and the Edict of Nantes

Henry IV successfully ended the civil wars. He and his ministers pacified Catholic leaders using bribes of about 7 million écus, which was more than France's revenue per annum. Huguenot leaders were placated by the Edict of Nantes, which had four separate documents. The articles laid down the tolerance which would be accorded to the Huguenots including the exact places where worship may or may not take place, three Protestant universities were recognized, and synods of the church would be allowed. The king also issued two personal documents (called brevets) which recognized the Protestant establishment. The Edict of Nantes signed religious tolerance into law, and the brevets were an act of benevolence that created a Protestant state within France.[24]

Despite this, it would take years to restore law and order to France. The Edict was met by opposition from the parlements, objecting guarantees offered to the Protestants. The Parlement de Rouen did not formally register the edict until 1609, although it begrudgingly observed its terms.[25]

Later reign

Domestic policies

During his reign, Henry IV worked through the minister Maximilien de Béthune, Duke of Sully, to regularize state finance, promote agriculture, drain swamps, undertake public works, and encourage education. He established the Collège Royal Henri-le-Grand in La Flèche (today the Prytanée Militaire de la Flèche). He and Sully protected forests from further devastation, built a system of tree-lined highways, and constructed bridges and canals. He had a 1200-metre canal built in the park at the Château Fontainebleau (which may be fished today) and ordered the planting of pines, elms, and fruit trees.

The King restored Paris as a great city, with the Pont Neuf, which still stands today, constructed over the river Seine to connect the Right and Left Banks of the city. Henry IV also had the Place Royale built (since 1800 known as Place des Vosges), and added the Grande Galerie to the Louvre Palace. More than 400 metres long and thirty-five metres wide, this huge addition was built along the bank of the Seine River. At the time it was the longest edifice of its kind in the world. King Henry IV, a promoter of the arts by all classes of people, invited hundreds of artists and craftsmen to live and work on the building's lower floors. This tradition continued for another two hundred years, until Emperor Napoleon I banned it. The art and architecture of his reign have become known as the "Henry IV style" since that time.

An economic policy enacted by Henry IV was to reduce the amount of funds spent on imports of foreign goods and instead manufacture and grow those goods in France. He accomplished this in a couple of ways. Sumptuary laws were passed limiting the use of gold and silver cloth, which had to be imported. He also built royal factories to produce luxury commodities sought by the aristocracy: crystal glass, silk, satin, and tapestries (at Gobelins Manufactory and Savonnerie de Chaillot workshops. The king established a Commission that re-established silk weaving in Tours and Lyon, and increased linen production in Picardy and Brittany. To promote agriculture, they distributed 16,000 free copies of The Theatre of Agriculture by Olivier de Serres, a manual that explained agricultural concepts.[26]

King Henry's vision extended beyond France, and he financed several expeditions of Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Monts and Samuel de Champlain to North America.[27] France laid claim to New France (now Canada).[28]

International relations

During the reign of Henry IV, rivalry continued among France, the Habsburg rulers of Spain, and the Holy Roman Empire for the mastery of Western Europe. The conflict was not resolved until after the Thirty Years' War.

Spain and Italy

During Henry's struggle for the crown, Spain had been the principal backer of the Catholic League, and it tried to thwart Henry. Under the Duke of Parma, an army from the Spanish Netherlands intervened in 1590 against Henry and foiled his siege of Paris. Another Spanish army helped the nobles opposing Henry to win the Battle of Craon against his troops in 1592.

After Henry's coronation, the war continued because there was an official tug-of-war between the French and Spanish states, but after victory at the Siege of Amiens in September 1597 the Peace of Vervins was signed in 1598. This enabled him to turn his attention to Savoy, with which he also had been fighting. Their conflicts were settled in the Treaty of Lyon of 1601, which mandated territorial exchanges between France and the Duchy of Savoy.

A major problem that Henry IV faced was known as the Spanish Road, which followed Spanish territory through Savoy to the Low Countries. His first opportunity in taking down parts of the Spanish Road was in a dispute over the ownership of the marquisate of Saluzzo. The last marquis left Saluzzo to the French crown in 1548 (when Savoy was occupied completely by France) but in absence of strong control during the Wars of Religion, the territory's ownership was disputed. The matter was placed before papal arbitration since the duke of Savoy was reluctant to recognize France's claim to the territory. He offered to cede Bresse to France if he could retain Saluzzo. Henri IV accepted this but Spain pointed out that ceding Bresse would remove a vital part of the Spanish Road. Spain promised the Duke full support if he rejected the agreement, and he did so. Henry IV was already at Lyon and had soldiers ready. Four days after the duke formally rejected the agreement, Henry IV launched an invasion of fifty thousand men against the duchy and in the next week, almost every area west of the Alps was French territory. In January 1601, Henry accepted an offer of papal arbitration in the dispute and gained not only Bresse, but Bugey and Gex. Savoy retained a narrow corridor of territory, the Val de Chézery. This allowed Spanish troops to cross from Lombardy to Franche Comté without going through France, but at this point the Spanish Road was just a single bridge across the Rhône River.[29]

Even though the Saluzzo conflict was Henry IV's last major military operation, he still continued to try and counter Spain by providing subsidies to its enemies. He generously assisted the Dutch, and paid them over 12 million livres between 1598 and 1610. Some years, the payment was 10% of France's total annual budget. France also sent subsidies to Geneva after the Duke of Savoy's attempt to capture the city in 1602.[30]

Germany

In 1609 Henry's intervention helped to settle the War of the Jülich Succession through diplomatic means.

It was widely believed that in 1610 Henry was preparing to go to war against the Holy Roman Empire. The preparations were terminated by his assassination, however, and the subsequent rapprochement with Spain under the regency of Marie de' Medici.

Ottoman Empire

Even before Henry's accession to the French throne, the French Huguenots were in contact with Aragonese Moriscos in plans against the Habsburg government of Spain in the 1570s.[32] Around 1575, plans were made for a combined attack of Aragonese Moriscos and Huguenots from Béarn under Henry against Spanish Aragon, in agreement with the king of Algiers and the Ottoman Empire, but this project floundered with the arrival of John of Austria in Aragon and the disarmament of the Moriscos.[33][34] In 1576, a three-pronged fleet from Constantinople was planned to disembark between Murcia and Valencia while the French Huguenots would invade from the north and the Moriscos accomplish their uprising, but the Ottoman fleet failed to arrive.[33]

After his crowning, Henry continued the policy of a Franco-Ottoman alliance and received an embassy from Sultan Mehmed III in 1601.[35][36] In 1604, a "Peace Treaty and Capitulation" was signed between Henry IV and the Ottoman Sultan Ahmed I. It granted numerous advantages to France in the Ottoman Empire.[36]

In 1606–07, Henry IV sent Arnoult de Lisle as Ambassador to Morocco to obtain the observance of past friendship treaties. An embassy was sent to Tunisia in 1608 led by François Savary de Brèves.[37]

East Asia

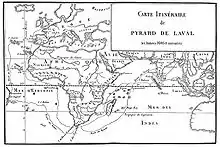

During the reign of Henry IV, various enterprises were set up to develop trade with faraway lands. In December 1600, a company was formed through the association of Saint-Malo, Laval, and Vitré to trade with the Moluccas and Japan.[38] Two ships, the Croissant and the Corbin, were sent around the Cape of Good Hope in May 1601. The Corbin was wrecked in the Maldives, leading to the adventure of François Pyrard de Laval, who managed to return to France in 1611.[38][39] The Croissant, carrying François Martin de Vitré, reached Ceylon and traded with Aceh in Sumatra, but was captured by the Dutch on the return leg at Cape Finisterre.[38][39] François Martin de Vitré was the first Frenchman to write an account of travels to the Far East in 1604, at the request of Henry IV, and from that time numerous accounts on Asia would be published.[40]

From 1604 to 1609, following the return of François Martin de Vitré, Henry attempted to set up a French East India Company on the model of England and the Netherlands.[39][40][41] On 1 June 1604, he issued letters patent to Dieppe merchants to form the Dieppe Company, giving them exclusive rights to Asian trade for 15 years. No ships were sent, however, until 1616.[38] In 1609, another adventurer, Pierre-Olivier Malherbe, returned from a circumnavigation of the globe and informed Henry of his adventures.[40] He had visited China and India, and had an encounter with Akbar.[40]

Religion

Historians have made the assertion that Henry IV was a convinced Calvinist, only changing his formal religious allegiance to adjust, suit or achieve his political goals.

Henry IV was baptized as a Catholic on 5 January 1554. He was raised in the Reformed Tradition by his mother Jeanne III of Navarre. In 1572, after the massacre of French Calvinists, he was forced by Catherine de' Medici and other powerful Catholic royalty to convert. In 1576, as he managed to escape from Paris, he abjured Catholicism and returned to Calvinism. In 1593, in order to gain recognition as King of France, he converted again to Catholicism. Although a formal Catholic, he valued his Calvinist upbringing and was tolerant toward the Huguenots until his death in 1610, and issued the Edict of Nantes which granted many concessions to them.

Assassination

Henry was the target of at least 12 assassination attempts, including one by Pierre Barrière in August 1593,[43] and another by Jean Châtel in December 1594.[44] Some of these assassination attempts were carried out against Henry because he was considered a usurper by some Catholics and a traitor by some Protestants.[45]

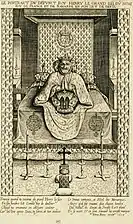

Henry was killed in Paris on 14 May 1610 by François Ravaillac, a Catholic zealot who stabbed him in the Rue de la Ferronnerie. Henry's coach was stopped by traffic congestion associated with the Queen's coronation ceremony, as depicted in the engraving by Gaspar Bouttats.[46][47] Hercule de Rohan, duc de Montbazon, was with him when he was killed; Montbazon was wounded, but survived. Ravaillac was immediately captured, and executed days later. Henry was buried at the Saint Denis Basilica.

His widow, Marie de' Medici, served as regent for their nine-year-old son, Louis XIII, until 1617.[48]

Assassination of Henry IV,

Assassination of Henry IV,

engraving by Gaspar Bouttats His assassin, François Ravaillac, brandishing his dagger

His assassin, François Ravaillac, brandishing his dagger Pierre Firens - "Le Roi Est Mort continues at the Palace of Versailles". 1610

Pierre Firens - "Le Roi Est Mort continues at the Palace of Versailles". 1610.jpg.webp) Lying in state at the Louvre, engraving after François Quesnel

Lying in state at the Louvre, engraving after François Quesnel

Legacy

In 1614, four years after Henry IV's death, a statue was erected in his honour on the Pont Neuf. During the early phase of the French Revolution when it aimed to create a constitutional monarchy rather than a republic, Henry IV was held up as an ideal that King Louis XVI was urged to emulate. When the Revolution radicalized and came to reject monarchy altogether, Henry IV's statue was torn down along with other royal monuments. It was nevertheless the first to be rebuilt, in 1818, and it still stands on the Pont Neuf today.[49]

A cult of personality surrounding Henry IV emerged during the Bourbon Restoration. The restored Bourbons were keen to play down the controversial reigns of Louis XV and Louis XVI, and instead lauded the reign of Henry IV.[50] The song Marche Henri IV ("Long Live Henry IV") was popular during the Restoration.[51] In addition, when Princess Caroline of Naples and Sicily (a descendant of his) gave birth to a male heir to the throne of France seven months after the assassination of her husband Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Berry, by a Republican fanatic, the boy was conspicuously named Henri in reference to his forefather Henry IV. The boy was also baptised with a spoon of Jurançon wine and some garlic, as is traditional in Béarn and Navarre. This imitated the quaint manner in which Henry IV had been baptised in Pau.

Henry serves as a loose inspiration for the character Ferdinand, King of Navarre, in William Shakespeare's 1590s play Love's Labour's Lost[52]

fr_(adjusted).jpg.webp)

.

The first edition of Henry IV's biography, Histoire du Roy Henry le Grand, was published in Amsterdam in 1661.[53] It was written by Hardouin de Péréfixe de Beaumont, successively bishop of Rhodez and archbishop of Paris, primarily for the edification of Louis XIV, grandson of Henry IV. [54] A translation into English was made by James Dauncey for another grandson, King Charles II of England. An English edition was published at London in 1663.[55]

On September 14, 1788, when anti-tax riots broke out during the incipient French Revolution, rioters demanded from those travelling through money for fireworks, and anyone riding in a carriage was forced to dismount to salute Henry IV.[56]

King Henry's accomplishments were compiled in de Sully's Royal Economies, published in 1611 after de Sully's fall from power. Upon closer historical analysis, it's clear that the memoirs are not entirely accurate. Forty percent of Royal Economies was made up of official documents from the reign of Henry IV, but subsequent research has shown that many were altered or even forged to make Henry IV's accomplishments look more notable. As well as de Sully's own part in them.[57]

Genealogy

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Henry IV of France[58] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Marriages and legitimate children

On 18 August 1572, Henry married his second cousin Margaret of Valois; their childless marriage was annulled in 1599. His subsequent marriage to Marie de' Medici on 17 December 1600 produced six children:

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Louis XIII, King of France[59] | 27 September 1601 | 14 May 1643 | Married Anne of Austria in 1615 |

| Elisabeth, Queen of Spain | 22 November 1602 | 6 October 1644 | Married Philip IV, King of Spain, in 1615 |

| Christine Marie, Duchess of Savoy | 10 February 1606 | 27 December 1663 | Married Victor Amadeus I, Duke of Savoy, in 1619 |

| Nicolas Henri, Duke of Orléans | 16 April 1607 | 17 November 1611 | |

| Gaston, Duke of Orléans | 25 April 1608 | 2 February 1660 | Married (1) Marie de Bourbon, Duchess of Montpensier, in 1626 Married (2) Marguerite of Lorraine in 1632 |

| Henrietta Maria, Queen of England, Queen of Scots, and Queen of Ireland | 25 November 1609 | 10 September 1669 | Married Charles I, King of England, King of Scots and King of Ireland, in 1625 |

Second marriage

Henry's first marriage was not a happy one, and the couple was childless. Henry and Margaret separated even before Henry acceded to the throne in August 1589; Margaret retired to the Château d'Usson in the Auvergne and lived there for many years. After Henry became king of France, it was of the utmost importance that he provide an heir to the crown to avoid the problem of a disputed succession.

Henry favoured the idea of obtaining an annulment of his marriage to Margaret and taking his mistress Gabrielle d'Estrées as his bride; after all, she had already borne him three children. Henry's councillors strongly opposed this idea, but the matter was resolved unexpectedly by Gabrielle's sudden death in the early hours of 10 April 1599, after she had given birth to a premature and stillborn son. His marriage to Margaret was annulled in 1599, and Henry married Marie de' Medici, daughter of Francesco I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, and Archduchess Joanna of Austria, in 1600.[60]

For the royal entry of Marie into Avignon on 19 November 1600, the citizens bestowed on Henry the title of the Hercule Gaulois ("Gallic Hercules"), justifying the extravagant flattery with a genealogy that traced the origin of the House of Navarre to a nephew of Hercules' son Hispalus.[61]

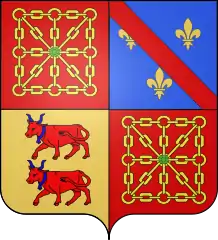

Armorial

The arms of Henry IV changed throughout his lifetime:

From 1562,

From 1562,

as Prince of Béarn and Duke of Vendôme From 1572,

From 1572,

as King of Navarre.svg.png.webp) From 1589,

From 1589,

as King of France and Navarre (also used by his successors) Grand Royal Coat of Arms of Henry and the House of Bourbon as Kings of France and Navarre (1589-1789)

Grand Royal Coat of Arms of Henry and the House of Bourbon as Kings of France and Navarre (1589-1789)

Notes

- Pitts 2009, p. 1.

- Pitts 2009, p. 334.

- Kamen 2002, p. 145.

- Dupuy, Johnson & Bongard 1995, p. 326.

- Knecht 1998, p. 153.

- Baird, Henry M., The Huguenots and Henry of Navarre, Vol. 1, (Charles Scribner's Sons:New York, 1886), p. 269

- Baird, Vol 1, p. 431

- Baird, Vol 2, p. 96

- Baird, Vol 2, p. 103

- Baird, Vol. 2, pp. 156–157

- Knecht 2014, p. 238.

- Baird, Vol. 2, p. 180

- Baird, Vol. 2, p. 181

- Holt, Mack P., The French Wars of Religion, 1562–2011, (Cambridge University Press, 1995), p. 148

- Ranke, Leopold. Civil Wars and Monarchy in France, p. 467

- Alistair Horne, Seven Ages of Paris, Random House (2004)

- F.P.G. Guizot (1787–1874) A Popular History of France..., gutenberg.org

- Janel Mueller & Joshua Scodel, eds, Elizabeth I, University of Chicago Press (2009)

- G. de Berthier de Savigny in his Histoire de France (1977 p. 167) claims that the Calvinists in revenge attributed the phrase to him.

- Paul Desalmand & Yves Stallini, Petit Inventaire des Citations Malmenées (2009)

- Knecht 2000, p. 269.

- Knecht 2000, p. 270.

- de La Croix, pp. 179–180

- Parker, pp. 117)

- Briggs, R. (pp. 33-4)

- Parker, G. pg. 120

- Harris, Carolyn (August 2017). "The Queen's land". Canada's History. 97 (4): 34–43. ISSN 1920-9894.

- de La Croix, p. 182

- Parker, G. (pp. 122-24)

- Parker, G. (pp-122-24)

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (1 January 1989). The Encyclopaedia of Islam: Fascicules 111–112: Masrah Mawlid. p. 799. ISBN 9789004092396. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- Kaplan, Benjamin J; Emerson, Michael O (2007). Divided by Faith. p. 311. ISBN 9780674024304. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- Lea, Henry Charles (January 1999). The Moriscos of Spain: Their Conversion and Expulsion. p. 281. ISBN 9780543959713.

- L.P. Harvey (15 September 2008). Muslims in Spain, 1500 to 1614. p. 343. ISBN 9780226319650. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- Gocek, Fatma Muge (3 December 1987). East Encounters West: France and the Ottoman Empire in the Eighteenth Century. p. 9. ISBN 9780195364330.

- Ziegler, Karl-Heinz (2004). "The peace treaties of the Ottoman Empire with European Christian powers". In Lesaffer, Randall (ed.). Peace Treaties and International Law in European History: From the Late Middle Ages to World War One. Cambridge University Press. p. 343. ISBN 978-0-521-82724-9.

- Moalla, Asma (27 November 2003). The Regency of Tunis and the Ottoman Porte, 1777-1814: Army and Government of a North-African Eyâlet at the End of the Eighteenth Century. p. 59. ISBN 9780203987223.

- Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume III: A Century of Advance. Book 1, Donald F. Lach pp. 93–94

- Newton, Arthur Percival (1936). The Cambridge History of the British Empire, volume 2. p. 61. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- Lach, Donald F; Van Kley, Edwin J (15 December 1998). Asia in the Making of Europe. p. 393. ISBN 9780226467658. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- A history of modern India, 1480–1950, Claude Markovits p. 144: The account of the experiences of François Martin de Vitré "incited the king to create a company in the image of that of the United Provinces"

- l'Académie française: Dictionnaire de la langue française (Institut de France. 6th edition. 1835): 'C'est un vert galant' se dit d'un homme vif, alerte, qui aime beaucoup les femmes et qui s'empresse à leur plaire. É.Littré: Dictionnaire Française (Hachette. 1863): Hommme vif, alerte, vigoreux et particulièrement empressé auprès de femmes. Grand Larousse de la Langue Française (Paris. 1973): Homme entreprenant auprès de femmes. And see Discussion under the heading Vert Galant – A look at the Dictionaries

- Baird, Vol. 2, p. 367

- Baird, Vol. 2, p. 368

- Pierre Miquel, Les Guerres de religion, Paris, Club France Loisirs (1980) ISBN 2-7242-0785-8, p. 399

- de l'Estoile, Pierre. Journal du règne de Henri IV. Paris: Gallimard, 1960. p. 84

- Knecht, Robert J. "The Murder of le roi Henri". History Today, May 2010.

- Moote, A. Lloyd. Louis XIII, the Just. University of California Press, Ltd., 1989. p. 41

- Thompson, Victoria E. (2012). "The Creation, Destruction and Recreation of Henri IV: Seeing Popular Sovereignty in the Statue of a King". History and Memory. 24 (2): 5–40. doi:10.2979/histmemo.24.2.5. ISSN 0935-560X. JSTOR 10.2979/histmemo.24.2.5. S2CID 159942339.

- Jones, Kimberly A. (1993). "Henri IV and the Decorative Arts of the Bourbon Restoration, 1814-1830: A Study in Politics and Popular Taste". Studies in the Decorative Arts. 1 (1): 2–21. doi:10.1086/studdecoarts.1.1.40662302. ISSN 1069-8825. JSTOR 40662302. S2CID 156578524.

- ""Vive Henri IV!"" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- G.R. Hibbard (editor), Love's Labour's Lost (Oxford University Press, 1990), p. 49

- PEREFIXE, Hardouin de Beaumont (1664). Histoire du Roy Henry le Grand (Third Elzevier ed.). Amsterdam: Daniel Elzevier.

- Hardouin, Paul Philippe (1661). Histoire de Henri-le-Grand, roi de France et de Navarre : suivie d'un recueil de quelques belles actions et paroles mémorables de ce prince (PDF) (Réédition ed.). Nîmes: C. Lacour.

- "The life of henry the fourth of france, Translated from the French of Perefix, by m. le moine, One of his most Christian Majesty's Gentlemen in Ordinary by PEREFIXE DE BEAUMONT, Paul Philippe Hardouin de]: (1785) | Antiquates Ltd - ABA, ILAB". www.abebooks.com. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- Peter Kropotkin (1909). "Chapter 5". The Great French Revolution, 1789-1793. Translated by N. F. Dryhurst. New York: Vanguard Printings.

Three weeks later, September 14, 1788, when the retirement of Lamoignon became known, the riotings were renewed. The mob rushed to set fire to the houses of the two ministers, Lamoignon and Brienne, as well as to that of Dubois. The troops were called out, and in the Rue Mélée and the Rue de Grenelle there was a horrible slaughter of poor folk who could not defend themselves. Dubois fled from Paris. "The people themselves would execute justice," said Les deux amis de la liberté. Later still, in October 1788, when the parlement that had been banished to Troyes was recalled, "the clerks and the populace" illuminated the Place Dauphine for several evenings in succession. They demanded money from the passersby to expend on fireworks, and forced gentlemen to alight from their carriages to salute the statue of Henri Quatre.

- Parker, G. (pg. 115)

- Neil D. Thompson and Charles M. Hansen, The Ancestry of Charles II, King of England (American Society of Genealogists, 2012).

- Pitts 2009, p. 335.

- Pitts 2009, p. 229.

- The official account, Labyrinthe royal... quoted in Jean Seznec, The Survival of the Pagan Gods, (B.F. Sessions, tr., 1995) p. 26

References

- Baird, Henry M. (1886). The Huguenots and Henry of Navarre (2 volumes). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. Vol. 2 (copies 1 & 2) at Google Books.

- Baumgartner, Frederic J. (1995). France in the Sixteenth Century. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-62088-5.

- de La Croix, Rene; de Castries, Duc (1979). The Lives of the Kings & Queens of France. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-50734-7.

- Dupuy, Trevor N.; Johnson, Curt; Bongard, David L. (1995). The Harper Encyclopedia of Military Biography. Castle Books. ISBN 978-0-7858-0437-6.

- Holt, Mack P. (2005). The French Wars of Religion, 1562–1629. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83872-6.

- Kamen, Henry, ed. (2002). "Henri IV Bourbon". Who's Who in Europe 1450 1750. Routledge.

- Knecht, Robert J. (1998). Catherine de' Medici. London; New York: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-08241-0.

- Knecht, Robert J. (2000). The French Civil Wars. Pearson Education Limited.

- Knecht, Robert J. (2014). Hero or Tyrant? Henry III, King of France, 1574-89. Routledge.

- Merlin, Paolo (2010). A 400 anni dai Trattati di Bruzolo. Gli equilibri europei prima e dopo i Trattati. Susa: Segusium (association).

- Moote, A. Lloyd (1991). Louis XIII, the Just. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07546-7.

- Parker, Geoffrey (1979). Europe in Crisis, 1598-1648. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

- Pitts, Vincent J. (2009). Henri IV of France: His Reign and Age. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Further reading

- Non-fiction

- Baumgartner, Frederic J. (1995). France in the Sixteenth Century. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-62088-5.

- Briggs, Robin (1977). Early Modern France, 1560–1715. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-289040-5.

- Bryson, David M. (1999). Queen Jeanne and the Promised Land: Dynasty, Homeland, Religion and Violence in Sixteenth-century France. Leiden; Boston, MA: Brill Academic. ISBN 978-90-04-11378-7.

- Buisseret, David (1990). Henry IV, King of France. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-04-445635-3.

- Cameron, Keith, ed. (1989). From Valois to Bourbon: Dynasty, State & Society in Early Modern France. Exeter: University of Exeter. ISBN 978-0-85989-310-7.

- Finley-Croswhite, S. Annette (1999). Henry IV and the Towns: The Pursuit of Legitimacy in French Urban Society, 1589–1610. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-62017-8.

- Frieda, Leonie (2005). Catherine de Medici. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-7538-2039-1.

- Greengrass, Mark (1984). France in the Age of Henri IV: The Struggle for Stability. London: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-49251-6.

- Holt, Mack P. (2005). The French Wars of Religion, 1562–1629. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83872-6.

- Lee, Maurice J. (1970). James I & Henri IV: An Essay in English Foreign Policy, 1603–1610. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-00084-3.

- Lloyd, Howell A. (1983). The State, France, and the Sixteenth Century. London: George Allen and Unwin. ISBN 978-0-04-940066-5.

- Lockyer, Roger (1974). Habsburg and Bourbon Europe, 1470–1720. Harlow, UK: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-35029-8.

- Love, Ronald S. (2001). Blood and Religion: The Conscience of Henri IV, 1553–1593. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-2124-7.

- Major, J. Russell (1997). From Renaissance Monarchy to Absolute Monarchy: French Kings, Nobles & Estates. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5631-0.

- Mousnier, Roland (1973). The Assassination of Henry IV: The Tyrannicide Problem and the Consolidation of the French Absolute Monarchy in the Early Seventeenth Century. Translated by Joan Spencer. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-684-13357-7.

- Parker, Geoffrey (1979). Europe in Crisis: 1598-1648. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

- Pettegree, Andrew (2002). Europe in the Sixteenth Century. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-20704-7.

- Salmon, J.H.M. (1975). Society in Crisis: France in the Sixteenth Century. London: Ernest Benn. ISBN 978-0-510-26351-5.

- Sutherland, N.M. (1973). The Massacre of St. Bartholomew and the European Conflict, 1559–1572. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-13629-4.

- ——— (1980). The Huguenot Struggle for Recognition. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-02328-2.

- ——— (1984). Princes, Politics and Religion, 1547–1589. London: Hambledon Press. ISBN 978-0-907628-44-6.

- ——— (2002). Henry IV of France and the Politics of Religion, 1572–1596. 2 volumes. Bristol: Elm Bank. ISBN 978-1-84150-846-7.

- Wolfe, Michael (1993). The Conversion of Henri IV: Politics, Power, and Religious Belief in Early Modern France. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-17031-8

- Fiction

- George Chapman (1559?–1634), The Conspiracy and Tragedy of Charles, Duke of Byron (1608), éd. John Margeson (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1988)

- Alexandre Dumas, La Reine Margot (Queen Margot) (1845)

- Heinrich Mann, Die Jugend des Königs Henry Quatre (1935); Die Vollendung des Königs Henry Quatre (1938) (in German)

- M. de Rozoy, Henri IV, Drame lyrique (1774) (in French)

External links

Henri IV. to the Fair Gabrielle., a poem by Letitia Elizabeth Landon adjoined to a painting Henri IV and Gabrielle d'Estrées by Richard Westall.

Henri IV. to the Fair Gabrielle., a poem by Letitia Elizabeth Landon adjoined to a painting Henri IV and Gabrielle d'Estrées by Richard Westall.- Henri IV – An unfinished reign Official website published by the French Ministry of Culture.