Nepali language

Nepali (English: /nɪˈpɔːli/;[3] Devanagari: नेपाली, [ˈnepali]) is an Indo-Aryan language of the sub-branch of Eastern Pahari native to the Himalayas region of South Asia. It is the official, lingua franca, and most widely spoken language of Nepal and Nepali has official status in the Indian state of Sikkim, Darjeeling Sadar subdivision and Kalimpong district, the Gorkhaland Territorial Administration of West Bengal and it is spoken by about a quarter of population in Bhutan. It also has a significant number of speakers in the states of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Himachal Pradesh, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram and Uttarakhand.[4] Nepali is also spoken in Myanmar by the Burmese Gurkhas and it is also spoken by the Nepali diaspora in the Middle East, Brunei, Australia and worldwide.[5] With approximately 16 million native speakers and another 9 million as second language speakers, Nepali is the most-spoken Northern Indo-Aryan language.

| Nepali | |

|---|---|

| नेपाली | |

The word "Nepali" written in Devanagari script | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈnepali] |

| Native to | Nepal, India, and Bhutan |

| Region | Karnali Province[lower-alpha 1][1] |

| Ethnicity | Khas people |

Native speakers | 16 million (2011 census)[2] L2 speakers 9 million (2011 census)[2] |

Indo-European

| |

| Devanagari Devanagari Braille | |

Signed forms | Signed Nepali |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

|

| Regulated by | Nepal Academy |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ne |

| ISO 639-2 | nep |

| ISO 639-3 | nep – inclusive codeIndividual code: npi – Nepali |

| Glottolog | nepa1254nepa1252 duplicate code |

| Linguasphere | 59-AAF-d |

Map showing distribution of Nepali speakers in South Asia. Dark red is areas with a Nepali-speaking majority or plurality, light red is where Nepali speakers are more than 20% of the population | |

Nepali language originated from the Sinja Valley, Karnali Province then the capital city of the Khasa Kingdom around the 10th and 14th centuries. It developed proximity to a number of Indo-Aryan languages, most significantly to other Pahari languages. Nepali was originally spoken by the Khas people, an Indo-Aryan ethno-linguistic group native to the Himalayan region of South Asia. The earliest inscription in the Nepali language is believed to be an inscription in Dullu, Dailekh District which was written around the reign of King Bhupal Damupal around the year 981. The institutionalisation of the Nepali language arose during the rule of the Kingdom of Gorkha (later became known as the Kingdom of Nepal) in the 16th century. Over the centuries, different dialects of the Nepali language with distinct influences from Sanskrit, Maithili, Hindi, and Bengali are believed to have emerged across different regions of the current-day Nepal and Uttarakhand, making Nepali the lingua franca.

Nepali is a highly fusional language with relatively free word order, although the dominant arrangement is subject–object–verb word order (SOV). There are three major levels or gradations of honorific: low, medium and high. Low honorific is used where no respect is due, medium honorific is used to signify equal status or neutrality, and high honorific signifies respect. Like all modern Indo-Aryan languages, Nepali grammar has syncretized heavily, losing much of the complex declensional system present in the older languages. Nepali literature, developed a significant literature within a short period of a hundred years in the 19th century. Around 1830, several Nepali poets wrote on themes from the Sanskrit epics Ramayana and the Bhagavata Purana, which was followed by Bhanubhakta Acharya translating the Ramayana in Nepali which received "great popularity for the colloquial flavour of its language, its religious sincerity, and its realistic natural descriptions".[6]

Etymology

The initial name of Nepali language was Khas Kura.An archaic dialect of the language is spoken in Karnali.[7] During the Shah dynasty the language was also referred to as Gorakhā bhāṣā (Nepali: गोरखा भाषा), meaning language of the Gorkhas.[8][9][10][11][12] Gorkha Bhasa Prakashini Samiti (Gorkha Language Publishing Committee), a government institution established in 1913 (B.S. 1970) for advancement of Gorkha Bhasa, renamed itself as Nepali Bhasa Prakashini Samiti (Nepali Language Publishing Committee) in 1933 (B.S. 1990), and is currently known as Sajha Prakashan.[12] The language is also called Parvate Kurā (Nepali: पर्वते कुरा), which literally means talks of the hills.[9][13][14][15][16] The name Pāṣyā Bolī (Nepali: पाष्या बोली) was also briefly used during the regime of Jung Bahadur Rana.[17] The Tibetan nationalities refer to the language as Khasa Bhāṣā.[18][19][20][21] Nepali language is known as Khae Bhāe (Nepal Bhasa: 𑐏𑐫𑑂 𑐨𑐵𑐫𑑂, खय् भाय्) in the Newar community,[22] Jyārdī Gyoī (Tamang:ज्यार्दी ग्योई) or Jyārtī Gyot (Tamang:ज्यार्ती ग्योत्) in the Tamang community,[23][24] Khasanta (Chepang:खस्अन्त) in the Chepang community,[25] Roṅakeka (Lhowa:रोङकेक) in the Lhowa community[26] and Khase Puka (Dungmali:खसे पुक) in Dungmali community.[19] In Bhutan, the language is known as Lhotshamkha in Dzongkha.[27]

History

Early Nepali

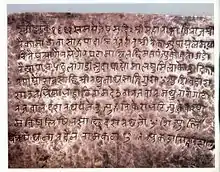

The earliest evidence and inscriptions of dialects related to the Nepali language support the theory of a linguistic intrusion from the West or Northwest Himalayas into the Central Himalayas in the present-day regions of Western Nepal during the rule of Khasas, an Indo-Aryan speaking group, who migrated from the northwest.[28] The oldest discovered inscription in the Nepali language is believed to be the Dullu Inscription, believed to have been written around the reign of King Bhupal Damupal around the year 981. Changes of phonological patterns indicate that Nepali is related to other Northwest Indian languages, including Sindhi, Punjabi, and Lahnda. Comparative reconstructions based on vocabulary have substantiated the relations of the Nepali language to proto-Dardic, Pahari, Sindhi, Lahnda, and Punjabi.[29] Archaeological and historical investigations show that modern Nepali descends from the language spoken by the ancient Khasha people. There is some mention of the word khasha in Sanskrit legal, historical, and literary texts like Manusmriti (circa 100 CE), Puranas (350–1500), and the Rajatarangini (1148).[29] The Khashas are documented to have ruled over a vast territory comprising what is now western Nepal, parts of Garhwal and Kumaon in northern India, and some parts of southwestern Tibet. King Ashoka Challa (1255–1278) is believed to have proclaimed himself Khasha-Rajadhiraja (emperor of the Khashas) in a copper-plate inscription found in Bodh Gaya, and several other copper plates in ancient Nepali have been traced back to the king's descendants.[29]

Middle Nepali

The Ashoka Challa inscription of 1255 is the earliest example of modern Nepali. The languages of these early inscriptions are considered to be a dialect of Jumla and West Nepal, rather than a predecessor of the dialect of Gorkha, which became the modern Nepali language.[30]

The earliest example of modern Nepali is the literary manuscript Svastanivratakatha, dated 1648. Other such early literary texts in modern Nepali are the anonymous version of the "Khandakhadya" (dated 1649), the "Bajapariksha" (1700) and "Jvarotpatticikitsa" written by Banivilas Jytoirvid (1773) and "Prayascittapradipa" written by Premnidhi Pant (1780).[30] The 1670 Rani Pokhari inscription of King Pratap Malla, another early example of modern Nepali, indicates the significant increment of Nepali speakers in Kathmandu valley.[30] The currently popular variant of Nepali is believed to have originated around 500 years ago with the mass migration of a branch of Khas people from the Karnali-Bheri-Seti eastward to settle in lower valleys of the Karnali and the Gandaki basin that were well-suited to rice cultivation. Over the centuries, different dialects of the Nepali language with distinct influences from Sanskrit, Maithili, Hindi, and Bengali are believed to have emerged across different regions of the current-day Nepal and Uttarakhand, making Khasa the lingua franca.

The institutionalisation of the Nepali language is believed to have started with the Shah kings of Gorkha Kingdom, in the modern day Gorkha District of Nepal. In 1559, a prince of Lamjung, Dravya Shah established himself on the throne of Gorkha with the help of local Khas and Magars. He raised an army of khas people under the command of Bhagirath Panta. Later, in the late 18th century, his descendant, Prithvi Narayan Shah, raised and modernized an army of Chhetri, Thakuri, Magars, Gurung people, and others and set out to conquer and consolidate dozens of small principalities in the Himalayas. Since Gorkha had replaced the original Khas homeland, Khaskura was redubbed Gorkhali "language of the Gorkhas".

Modern Nepali

One of the most notable military achievements of Prithvi Narayan Shah was the conquest of Kathmandu Valley, a region called Nepal at the time. After the overthrowing of the Malla rulers, Kathmandu was established as Prithvi Narayan's new capital. The Khas people originally referred to their language as Khas kurā ("Khas speech"), which was also known as Parbatiya (or Parbattia or Paharia, meaning language of the hill country).[31][32] The Newar people used the term "Gorkhali" as a name for this language, as they identified it with the Gorkhali conquerors. The Gorkhalis themselves started using this term to refer to their language at a later stage.[33] The census of India prior to independence used the term Naipali at least from 1901 to 1951, the 1961 census replacing it with Nepali.[34][35]

Historically, Sanskrit has been a significant source of vocabulary for the Nepali language.[36] According to exclusive phonological evidences observed by lexicographer Sir Ralph Turner, Nepali language is closely related to Punjabi, Lahnda, Hindi and Kumaoni while it appears to share some distinguishing features with the other Indo-Aryan languages like Rajasthani, Gujarati and Bangla.[36] Ethnologist Brian Houghton Hodgson stated that the Khas or Parbattia language is an "Indian Prakrit" brought by colonies from south of the Nepalese hills, and the whole structure including the eighth-tenth portion of the vocabulary of it is "substantially Hindee" due to the influences and loanwords it shares with Arabic and Farsi.[37]

Contemporary Nepali

Expansion – particularly to the north, west, and south – brought the growing state into conflict with the British and the Chinese. This led to wars that trimmed back the territory to an area roughly corresponding to Nepal's present borders. After the Gorkha conquests, the Kathmandu valley or Nepal became the new center of politics. As the entire conquered territory of the Gorkhas ultimately became Nepal, in the early decades of the 20th century, Gorkha language activists in India, especially Darjeeling and Varanasi, began petitioning Indian universities to adopt the name 'Nepali' for the language.[38] Also in an attempt to disassociate himself with his Khas background, the Rana monarch Jung Bahadur Rana decreed that the term Gorkhali be used instead of Khas kurā to describe the language. Meanwhile, the British Indian administrators had started using the term "Nepal" to refer to the Gorkha kingdom. In the 1930s, Nepal government also adopted this term fully. Subsequently, the Khas language came to be known as "Nepali language".[1]

The earliest Nepali grammar to have survived was written by Veerendra Keshari Aryal entitled "Nepali Vyakaran" and it is dated around 1891 to 1905. The grammar is based on Panini model and it equates Nepali with Prakrit and labels it as "the mountain Prakrit".[39] However, later the official institution established in 1912 for formalizing Nepali language, the "Gorkha Bhasha Prakashini Samiti", accepted the 1920 grammar text entitled Candrika Gorkha Bhasha Vyakaran by Pandit Hemraj Pandey as the official grammar of the Nepali language.[39] Nepali is spoken indigenously over most of Nepal west of the Gandaki River, then progressively less further to the east.[40]

Literature

Nepali developed a significant literature within a short period of a hundred years in the 19th century. This literary explosion was fuelled by Adhyatma Ramayana; Sundarananda Bara (1833); Birsikka, an anonymous collection of folk tales; and a version of the ancient Indian epic Ramayana by Bhanubhakta Acharya (d. 1868). The contribution of trio-laureates Lekhnath Paudyal, Laxmi Prasad Devkota, and Balkrishna Sama took Nepali to the level of other world languages. The contribution of expatriate writers outside Nepal, especially in Darjeeling and Varanasi in India, is also notable.

Geographical distribution

According to the 2011 national census, 44.6% of the population of Nepal speaks Nepali as its first language.[41] and 32.8% speak Nepali as a second language.[42] Ethnologue reports 12,300,000 speakers within Nepal (from the 2011 census).[42]

Nepali is traditionally spoken in the hilly regions of Nepal.[43] The language is prominently used by the government of Nepal and is the everyday language of the local population. The exclusive use of Nepali in the court system and by the government of Nepal, however, is being challenged. Gaining recognition for other languages of Nepal was one of the goals of the decades-long Maoist insurgency.[44]

In Bhutan, native Nepali speakers, known as Lhotshampa, are estimated at 35%[45] of the population. This number includes displaced Bhutanese refugees, with unofficial estimates of the ethnic Bhutanese refugee population as high as 30 to 40%, constituting a majority in the south (about 242,000 people).[46]

According to the 2011 Census of India, there were a total of 2,926,168 Nepali language speakers in India.[47]

Nepali is the third-most spoken language in the Australian territory of Tasmania, where it is spoken by 1.3% of its population,[48] and fifth-most spoken language in the Northern Territory, Australia, spoken by 1.3% of its population.[49]

Dialects

Dialects of Nepali include Acchami, Baitadeli, Bajhangi, Bajurali, Bheri, Dadeldhuri, Dailekhi, Darchulali, Darchuli, Gandakeli, Humli, Purbeli, and Soradi.[42] These dialects can be distinct from Standard Nepali. Mutual intelligibility between Baitadeli, Bajhangi, Bajurali (Bajura), Humli, and Acchami is low.[42] The dialect of Nepali language spoken in Karnali Province is not mutually intelligible with Standard Nepali. The language is known with its old name as Khas Bhasa in Karnali.[7]

Phonology

Vowels and consonants are outlined in the tables below.

Monophthongs

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i ĩ | u ũ | |

| Close-mid | e ẽ | o | |

| Open-mid | ʌ ʌ̃ | ||

| Open | a ã |

Nepali distinguishes six oral vowels and five nasal vowels. /o/ does not have a phonemic nasal counterpart, although it is often in free variation with [õ].

Diphthongs

Nepali has ten diphthongs: /ui̯/, /iu̯/, /ei̯/, /eu̯/, /oi̯/, /ou̯/, /ʌi̯/, /ʌu̯/, /ai̯/, and /au̯/.

Consonants

| Bilabial | Dental | Alveolar | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m ⟨म⟩ | n ⟨न/ञ⟩ | (ɳ ⟨ण⟩) | ŋ ⟨ङ⟩ | |||||

| Plosive/ Affricate |

voiceless | unaspirated | p ⟨प⟩ | t ⟨त⟩ | t͡s ⟨च⟩ | ʈ ⟨ट⟩ | k ⟨क⟩ | ||

| aspirated | pʰ ⟨फ⟩ | tʰ ⟨थ⟩ | t͡sʰ ⟨छ⟩ | ʈʰ ⟨ठ⟩ | kʰ ⟨ख⟩ | ||||

| voiced | unaspirated | b ⟨ब⟩ | d ⟨द⟩ | d͡z ⟨ज⟩ | ɖ ⟨ड⟩ | ɡ ⟨ग⟩ | |||

| aspirated | bʱ ⟨भ⟩ | dʱ ⟨ध⟩ | d͡zʱ ⟨ |

ɖʱ ⟨ढ⟩ | ɡʱ ⟨घ⟩ | ||||

| Fricative | s ⟨श/ष/स⟩ | ɦ ⟨ह⟩ | |||||||

| Rhotic | r ⟨र⟩ | ||||||||

| Approximant | (w ⟨व⟩) | l ⟨ल⟩ | (j ⟨य⟩) | ||||||

[j] and [w] are nonsyllabic allophones of [i] and [u], respectively. Every consonant except [j], [w], and /ɦ/ has a geminate counterpart between vowels. /ɳ/ and /ʃ/ also exist in some loanwords such as /baɳ/ बाण "arrow" and /nareʃ/ नरेश "king", but these sounds are sometimes replaced with native Nepali phonemes.

Final schwas may or may not be preserved in speech. The following rules can be followed to figure out whether or not Nepali words retain the final schwa.

1) Schwa is retained if the final syllable is a conjunct consonant. अन्त (anta, 'end'), सम्बन्ध (sambandha, 'relation'), श्रेष्ठ (śreṣṭha, 'greatest'/a last name).

Exceptions: conjuncts such as ञ्च ञ्ज in मञ्च (mañc, 'stage') गञ्ज (gañj, 'city') and occasionally the last name पन्त (panta/pant).

2) For any verb form the final schwa is always retained unless the schwa-cancelling halanta is present. हुन्छ (huncha, 'it happens'), भएर (bhaera, 'in happening so; therefore'), गएछ(gaecha, 'he apparently went'), but छन् (chan, 'they are'), गईन् (gain, 'she went').

Meanings may change with the wrong orthography: गईन (gaina, 'she didn't go') vs गईन् (gain, 'she went').

3) Adverbs, onomatopoeia and postpositions usually maintain the schwa and if they don't, halanta is acquired: अब (aba 'now'), तिर (tira, 'towards'), आज (āja, 'today') सिम्सिम (simsim 'drizzle') vs झन् (jhan, 'more').

4) Few exceptional nouns retain the schwa such as: दुख(dukha, 'suffering'), सुख (sukha, 'pleasure').

Note: Schwas are often retained in music and poetry to facilitate singing and recitation.

Grammar

Nepali is a highly Fusional language with relatively free word order, although the dominant arrangement is SOV (subject–object–verb). There are three major levels or gradations of honorific: low, medium and high. Low honorific is used where no respect is due, medium honorific is used to signify equal status or neutrality, and high honorific signifies respect. There is also a separate highest level honorific, which was used to refer to members of the royal family, and by the royals among themselves.[50] Like all modern Indo-Aryan languages, Nepali grammar has syncretized heavily, losing much of the complex declensional system present in the older languages. Instead, it relies heavily on periphrasis, a marginal verbal feature of older Indo-Aryan languages.[51]

Writing system

Nepali is written in Devanagari script.

In the section below Nepali is represented in Latin transliteration using the IAST scheme and IPA. The chief features are: subscript dots for retroflex consonants; macrons for etymologically, contrastively long vowels; h denoting aspirated plosives. Tildes denote nasalised vowels.

Consonants

Vowels

| Orthography | अ | आ | इ | ई | उ | ऊ | ए | ऐ | ओ | औ | अं | अः | अँ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IAST | a | ā | i | ī | u | ū | e | ai | o | au | aṃ | aḥ | am̐/ã |

| IPA | ʌ | a | i | i | u | u | e | ʌi̯ | o | ʌu̯ | ʌ̃ | ʌɦʌ | ʌ̃ |

| Vowel mark indicated on consonant b | ब | बा | बि | बी | बु | बू | बे | बै | बो | बौ | बं | बः | बँ |

Sample text

The following is a sample text in Nepali, of Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

| Nepali |

|---|

| धारा १. सबै व्यक्तिहरू जन्मजात स्वतन्त्र हुन् ती सबैको समान अधिकार र महत्व छ। निजहरूमा विचार शक्ति र सद्विचार भएकोले निजहरूले आपसमा भातृत्वको भावनाबाट व्यवहार गर्नु पर्छ।[52] |

| Transliteration (IAST) |

| Dhārā 1. Sabai vyaktiharū janmajāt svatantra hun tī sabaiko samān adhikār ra mahatva cha. Nijharūmā vicār śakti ra sadvicār bhaekole nijharūle āpasmā bhatṛtvako bhāvanabāṭa vyavahār garnu parcha. |

| Transcription (IPA) |

| [dʱaɾa ek sʌbʌi̯ bektiɦʌɾu d͡zʌnmʌd͡zat sotʌntɾʌ ɦun ti sʌbʌi̯ko sʌman ʌd(ʱ)ikaɾ rʌ mʌːtːo t͡sʰʌ nid͡zɦʌɾuma bit͡saɾ sʌkti ɾʌ sʌdbit͡sar bʱʌekole nid͡zɦʌɾule apʌsma bʱatɾitːoko bʱawʌnabaʈʌ bebaːr ɡʌɾnu pʌɾt͡sʰʌ] |

| Gloss (word-to-word) |

| Article 1. All human-beings from-birth independent are their all equal right and importance is. In themselves, intellect and conscience endowed therefore they one another brotherhood's spirit treatment with do must. |

| Translation (grammatical) |

| Article 1. All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. |

Vocabulary

| Numeral | Written | IAST | IPA | Etymology | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | ० | शुन्य/सुन्ना | śunya | [sunːe] | Sanskrit śūnya (शून्य) |

| 1 | १ | एक | ek | /ek/ | Sanskrit eka (एक) |

| 2 | २ | दुई | duī | /d̪ui̯/ | Sanskrit dvi (द्वि) |

| 3 | ३ | तीन | tīn | /t̪in/ | Sanskrit tri (त्रि) |

| 4 | ४ | चार | cār | /t͡sar/ | Sanskrit catúr (चतुर्) |

| 5 | ५ | पाँच | pām̐c | /pãt͡s/ | Sanskrit pañca (पञ्च) |

| 6 | ६ | छ | cha | /t͡sʰʌ/ | Sanskrit ṣáṣ (षष्) |

| 7 | ७ | सात | sāt | /sat̪/ | Sanskrit saptá (सप्त) |

| 8 | ८ | आठ | āṭh | /aʈʰ/ | Sanskrit aṣṭá (अष्ट) |

| 9 | ९ | नौ | nau | /nʌu̯/ | Sanskrit náva (नव) |

| 10 | १० | दश | daś | /d̪ʌs/ | Sanskrit dáśa दश |

| 11 | ११ | एघार | eghāra | [eɡʱäɾʌ] | |

| 12 | १२ | बाह्र | bāhra | /barʌ/ [bäɾʌ] | |

| 20 | २० | बीस | bīs | /bis/ | |

| 21 | २१ | एक्काइस | ekkāis | /ekːai̯s/ | |

| 22 | २२ | बाइस | bāis | /bai̯s/ | |

| 100 | १०० | एक सय | ek saya | [ek sʌe̞] | |

| 1 000 | १,००० | एक हजार | ek hajār | /ek ɦʌd͡zar/ | |

| 10 000 | १०,००० | दश हजार | daś hajār | [d̪ʌs ɦʌd͡zär] | |

| 100 000 | १,००,००० | एक लाख | ek lākh | /ek lakʰ/ | See lakh |

| 1,000,000 | १०,००,००० | दश लाख | daś lākh | [d̪ʌs läkʰ] | |

| 10,000,000 | १,००,००,००० | एक करोड | ek karoḍ | [ek kʌɾoɽ] | See crore |

| 100,000,000 | १०,००,००,००० | दश करोड | daś karoḍ | [d̪ʌs kʌɾoɽ] | |

| 1,000,000,000 | १,००,००,००,००० | एक अरब | ek arab | [ek ʌɾʌb] | |

| 10,000,000,000 | १०,००,००,००,००० | दश अरब | daś arab | [d̪ʌs ʌɾʌb] | |

| 1012 | १०१२ | एक खरब | ek kharab | [ek kʰʌɾʌb] | |

| 1014 | १०१४ | एक नील | ek nīl | /ek nil/ | |

| 1016 | १०१६ | एक पद्म | ek padma | /ek pʌd̪mʌ/ | |

| 1018 | १०१८ | एक शंख | ek śaṅkha | /ek sʌŋkʰʌ/ | |

The numbering system has roots in Vedic numbering system, found in the ancient scripture of Ramayana.

See also

- Vikram Samvat

- Nepali language movement

References

- Richard Burghart 1984, pp. 118–119.

- Nepali at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

Nepali at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018) - "Nepali | Definition of Nepali by Oxford Dictionary on Lexico.com also meaning of Nepali". Lexico Dictionaries | English. Archived from the original on 23 July 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- "52nd Report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India" (PDF). nclm.nic.in. Ministry of Minority Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- "Nepali language | Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- "Nepali literature". Britannica. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- "5 features of Nepali, Nepal's lingua franca, that you are unaware of". Online Khabar. Online Khabar. 3 October 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- Lienhard, Siegfried (1992). Songs of Nepal: An Anthology of Nevar Folksongs and Hymns. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas. ISBN 81-208-0963-7. Page 3.

- Maharjan, Rajendra. "एकल राष्ट्र–राज्यको धङधङी". EKantipur. Kantipur Publication Limited. Retrieved 30 October 2021.आजभन्दा करिब नौ दशकअघि मात्रै देशको नाम ‘नेपाल’ का रूपमा स्विकारिएको हो भने, पहिले खस–पर्वते–गोर्खाली भनिने भाषालाई ‘नेपाली’ नामकरण गरिएको हो ।

- Clark, T. W. (1973). "Nepali and Pahari". Current Trends in Linguistics. Walter de Gruyter. p. 252.

- "The kings song". Himal Southasian. June 2003. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- "साझा प्रकाशन एक झलक". Sajha Prakashan. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- "पर्वते(नेपाली) भाषाको इतिहास". Nepal Patra. Retrieved 9 November 2021.नेपाली भाषा बिभिन्न समयमा बिभिन्न नामले चिनिन्थ्यो । खस कुरा, पर्वते भाषा तथा गोर्खाली भाषा आदि । यी मध्ये खस कुरा सबैभन्दा पुरानो नाम हो । खस जातीहरूले बोल्ने भाषा भएको हुनाले यसलाई खस भाषा भनिएको हो । यो भाषा पश्चिम नेपालको कर्णाली क्षेत्रमा विकशित भएर पूर्वतर्फ फैलदै गएको हो । खस कुरा पश्चिम नेपालको अर्को भाषा खाम कुरा, जुन नेपालका मगर जातीहरूले बोल्ने गर्दछन्, संगै विकशित हुँदै अगाडी बढ्यो ।

- Baniya, Karnabahadur. सेनकालीन पाल्पाको संस्कृति : एक ऐतिहासिक विवेचना. Palpa: Tribhuvan Multiple Campus. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 9 November 2021.ISSN:2616-017x

- "Nepali". Harvard University. Department of South Asian Studies. Retrieved 9 November 2021. long-established language dating back to the 1200s, it was previously known as Khas Kura and later Gorkha bhasa and also Parbate (‘the language of the mountain people’).

- Shrestha, Shiva Raj. Khaptad Region in Mythology (PDF). p. 10. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- Vasistha, Kedar. "'गोर्खा पत्रिकाहरू'को पदचाप". Gorakhapatra Online. Retrieved 9 November 2021. जङ्गबहादुरलाई पनि घिसार्ने गरिएको पाइन्छ तर उनको पालामा गोर्खा भाषा वा नेपाली भाषा नभनी पाष्या बोली वा पर्वते भाषाको प्रचलन रहेको देखिन्छ । तर उक्त सनद जारी भएको एक वर्षपछिको जङ्गबहादुरको एक पत्रमा उनले गोर्खा वा गोर्खाली वा नेपाली भाषाका नमुना भनी नभनी पाष्या (पाखे) बोली भनेका छन् ।

- Thapa, Lekh Bahadur (1 November 2013). "Roots: A Khas story". The Kathmandu Post. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- Kapali, Rukshana H. "खस-आर्यहरूले जस्तै हूबहु नबोल्दा किन लाञ्छना ?". Saino Khabar. नेवाः समुदायमा "खे भाये" वा "पर्त्या भाये", तामाङ भाषामा "ज्यार्दी ग्योइ" वा "ज्यार्ती ग्योत्", चेपाङ भाषामा "खस्अन्त", ल्होवा भाषामा "रोङकेक", इत्यादि ।

- "ईतिहासमा सबैभन्दा पहिले उत्पीडनमा परेको जाति". Hamra Kura. खसहरूलाई राईहरुले ‘खासा’ वा ‘लिच्चु’ वा ‘बाज्यु’ पनि भनेको पाइन्छ। लिम्बुहरुले ‘पेन’ वा ‘पेनेवा’ भन्दछन्। कोदो खाने भएकाले त्यस्तो भनिएको हो कि ! निम्न हिमाली क्षेत्रमा रहने भएकाले तामाङहरुले खसहरुलाई ‘ज्यार्दी’ वा ‘रोङ्बा’ भनेको पाइन्छ ।

- Hodgson, B. H. (1841). "Illustrations of the literature and religion of the Buddhists". Serampore. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- "के नेपाली भाषाको उत्पत्ति सिँजामै भएको हो ?". चौलानी खबर. 26 July 2019. खसद्वारा नै यहाँ यो भाषा पसेकोले यसले यहाँ ‘खय् भाय्’ भन्ने नाम पाएको हो ।

- "पश्चिमी तामाङ शब्दकोष". SIL Nepal. ज्यार्ती ग्योत् [dzjarti gjot] नाम – नेपाली भाषा

- "सिङ्ल्ह, गोने ङ्या र मेला". पिजनखबर.

- "ख". चेपाङ शब्दकोष. खस्अन्त [khəs.ʔən.tə] क्रि.वि. नेपाली adv Nepali (esp. in reference to the Nepali language)

- "रोङकेक". Lhowa Dictionary. SIL International. Retrieved 11 November 2021.रोङकेक [ᶫroŋkek] ना. नेपाली भाषा Nepali language (sem. domains: 9.7.1.5 – भाषाका नामहरू.)

- Bhutan, Tourism Council of. "Language". bhutan.travel. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- Jain & Cardona 2007, p. 543.

- "Nepali language | Britannica".

- Jain & Cardona 2007, p. 544.

- Balfour, Edward (1871). Cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia, Commercial, Industrial and Scientific: Products of the Mineral, Vegetable and Animal Kingdoms, Useful Arts and Manufactures. Scottish & Adelphi presses. p. 529 – via Google Books.

- Cust, Robert N. (1878). A Sketch of the Modern Languages of the East Indies. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 9781136384691 – via Google Books.

- Richard Burghart 1984, p. 118.

- General, India Office of the Registrar (1967). Census of India, 1961: Tripura. Manager of Publications. p. 336 – via Google Books.

Nepali (Naipali in 1951)

- Commissioner, India Census; Gait, Edward Albert (1902). Census of India, 1901. Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing, India. p. 91 – via Internet Archive.

Naipali is an Indo-Aryan language spoken by the upper classes in Nepal, whereas the minor Nepalese languages, such as Gurung, Magar, Jimdar, Yakha, etc., are members of the Tibeto-Burman family

- Jain & Cardona 2007, p. 545.

- Hodgson 2013, pp. 1–2.

- Onta, Pratyoush (1996) "Creating a Brave Nepali Nation in British India: The Rhetoric of Jati Improvement, Rediscovery of Bhanubhakta and the Writing of Bir History" in Studies in Nepali History and Society 1(1), p. 37-76.

- Jain & Cardona 2007, p. 548.

- "Nepal". Ethnologue. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Major highlights" (PDF). Central Bureau of Statistics. 2013. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- "Nepali (npi)". Ethnologue. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- "Languages in Nepal".

- Gurung, Harka (20 January 2005). Social Exclusion and Maoist Insurgency. p. 5. Retrieved 13 April 2012 – via Google Books.

- "Background Note: Bhutan". U.S. Department of State. 2 February 2010. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- Worden, Robert L.; Savada, Andrea Matles (1991). "Chapter 6: Bhutan - Ethnic Groups". Nepal and Bhutan: Country Studies (3rd ed.). Federal Research Division, United States Library of Congress. pp. 424. ISBN 978-0-8444-0777-7. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- "Language – India, States And Union Territories (Table C-16)" (PDF). census.gov.in. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- "Snapshot of Tasmania". abs.gov.au. 28 June 2022. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- "Snapshot Northern Territory, Housing and Population Census 2021". abs.gov.au. 28 June 2022. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- Jain & Cardona 2007, p. 571.

- Jain & Cardona 2007, p. 596.

- "Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Nepali language" (PDF). ohchr.org. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

Footnotes

- historically spoken just by the Karnali Khas people, now spoken as the lingua franca in Nepal

Bibliography

- Richard Burghart (1984). "The Formation of the Concept of Nation-State in Nepal". The Journal of Asian Studies. 44 (1): 101–125. doi:10.2307/2056748. JSTOR 2056748. S2CID 154584368.

- Jain, Danesh; Cardona, George (26 July 2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. ISBN 9781135797119.

- Hodgson, Brian Houghton (2013). Essays on the Languages, Literature, and Religion of Nepál and Tibet (Reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108056083. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

Further reading

- पोखरेल, मा. प्र. (2000), ध्वनिविज्ञान र नेपाली भाषाको ध्वनि परिचय, नेपाल राजकीय प्रज्ञा प्रतिष्ठान, काठमाडौँ।

- Schmidt, R. L. (1993) A Practical Dictionary of Modern Nepali.

- Turner, R. L. (1931) A Comparative and Etymological Dictionary of the Nepali Language.

- Clements, G.N. & Khatiwada, R. (2007). "Phonetic realization of contrastively aspirated affricates in Nepali." In Proceedings of ICPhS XVI (Saarbrücken, 6–10 August 2007), 629- 632.

- Hutt, M. & Subedi, A. (2003) Teach Yourself Nepali.

- Khatiwada, Rajesh (2009). "Nepali". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 39 (3): 373–380. doi:10.1017/S0025100309990181.

- Manders, C. J. (2007) नेपाली व्याकरणमा आधार A Foundation in Nepali Grammar.

- Dr. Dashrath Kharel, "Nepali linguistics spoken in Darjeeling-Sikkim"

External links

- List of Nepali words at Wiktionary, the free dictionary

- Omniglot – Nepali Language

- Barala – Easy Nepali Typing

- नेपाली बृहत् शब्दकोश | Nepali Brihat Shabdakosh (Comprehensive Nepali Dictionary) | "Nepal Academy"

- नेपाली बृहत् शब्दकोश | Nepali Brihat Shabdakosh – Nepali Dictionary "Nepali Brihat Shabdakosh Latest Edition"