Humanism

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

| Part of a series on |

| Humanism |

|---|

|

|

The meaning of the term "humanism" has changed according to the successive intellectual movements that have identified with it. During the Italian Renaissance, ancient works inspired scholars in various Italian cities, giving rise to a movement now called Renaissance humanism. With Enlightenment, humanistic values were re-enforced by the advances in science and technology, giving confidence to humans in their exploration of the world. By the early 20th century, organizations solely dedicated to humanism flourished in Europe and the United States, and have since expanded all over the globe. In the current day, the term generally refers to a focus on human well-being and advocates for human freedom, autonomy, and progress. It views humanity as responsible for the promotion and development of individuals, espouses the equal and inherent dignity of all human beings, and emphasizes a concern for humans in relation to the world.

Starting in the 20th century, humanist movements have typically been non-religious and aligned with secularism. Most frequently, humanism refers to a nontheistic view centered on human agency, and a reliance on science and reason rather than revelation from a supernatural source to understand the world. Humanists tend to advocate for human rights, free speech, progressive policies, and democracy. Those with a humanist worldview maintain religion is not a precondition of morality, and object to excessive religious entanglement with education and the state.

Contemporary humanist organizations work under the umbrella of Humanist International. Well know humanist associations are the Humanists UK and the American Humanist Association.

Etymology and definition

The word "humanism" derives from the Latin concept humanitas, which was first used by Cicero to describe values related to liberal education, a sense which survives in the modern university concept of the "humanities": the arts, philosophy, history, literature, and related disciplines. The word reappeared during the Italian Renaissance as umanista and entered the English language in the 16th century.[1] The word "humanist" was used to describe a group of students of classical literature and those advocating for education based on it.[2] In the early 19th century, the term Humanismus was used in Germany with several meanings and from there, it re-entered the English language with two distinct denotations; one an academic term linked to the study of classic literature while the other, more popular use signified a non-religious approach to life, implying an antithesis to theism.[3] It is probable Bavarian theologian Friedrich Immanuel Niethammer coined the term humanismus to describe the new classical curriculum he planned to offer in German secondary schools. Soon, other scholars such as Georg Voigt and Jacob Burckhardt adopted the term.[4] In the 20th century, the word was further refined, acquiring its contemporary meaning of a naturalistic approach to life, focusing on the well-being and freedom of humans.[5]

Defining humanism reveals the controversy surrounding humanism.[6] For philosopher Sidney Hook, writing in 1974, humanists are opposed to the imposition of one culture in some civilizations, do not belong to a church or established religion, do not support dictatorships, do not justify violence for social reforms or are more loyal to an organization than their abstract values. Hook also said humanists support the elimination of hunger and improvements to health, housing, and education.[7] Also in 1974, Humanist philosopher H. J. Blackham said humanism is a concept that focuses on improving the social conditions of humanity, increasing the autonomy and dignity of all humans.[8] In 1999, Jeaneane D. Fowler said the definition of humanism should include a rejection of divinity, and an emphasis on human well-being and freedom. She also comments there is a lack of a shared belief system or doctrine but, in general, humanists are aiming for happiness and self-fulfillment.[9]

In 2015, prominent humanist Andrew Copson attempted to define humanism as follows:

- Humanism is naturalistic in its understanding of the universe; science and free inquiry will help us comprehend more and more about what is surrounding us.

- This scientific approach does not reduce humans to anything lesser than human beings.

- Humanists place importance of the pursuit of a self-defined, meaningful, and happy life.

- Humanism is moral; morality is a way of humans improving our lives.

- Humanists engage in practical action to improve personal and social conditions.[10]

According to the International Humanist and Ethical Union: "Humanism is a democratic and ethical life stance, which affirms that human beings have the right and responsibility to give meaning and shape to their own lives. It stands for the building of a more humane society through an ethic based on human and other natural values in the spirit of reason and free inquiry through human capabilities. It is not theistic, and it does not accept supernatural views of reality".[11]

Dictionaries define humanism as a worldview or life stance. According to Merriam Webster Dictionary, humanism is " ... a doctrine, attitude, or way of life centered on human interests or values; especially: a philosophy that usually rejects supernaturalism and stresses an individual's dignity and worth and capacity for self-realization through reason".[12]

History

Predecessors

Traces of humanism can be traced in the ancient Greek philosophy. Pre-Socratics philosophers were the first Western philosophers to attempt to explain the world in terms of human reason and natural law without relying on myth, tradition, or religion. Protagoras, who lived in Athens c. 440 BCE, put forward some fundamental humanist ideas. Only some fragments of his work survive. He made one of the first agnostic statements; according to one fragment: "About the gods I am able to know neither that they exist nor that they do not exist nor of what kind they are in form: for many things prevent me for knowing this, its obscurity and the brevity of man's life". (80B4 DK) [13] Socrates spoke of the need to "know thyself"; his thought changed the focus of the contemporary philosophy from nature to humans and their well-being. Socrates, a theist who was executed for atheism, investigated the nature of morality by reasoning.[14] Aristotle (384–322 BCE) taught rationalism and a system of ethics based on human nature that also parallels humanist thought.[13] In the 3rd century BCE, Epicurus formed an influential human-centered philosophy that focused on achieving eudaimonia. Epicureans continued Democritus' atomist theory—a materialistic theory that suggests the fundamental unit of the universe was an indivisible atom. Human happiness, living well, friendship, and the avoidance of excesses were the key ingredients of Epicurean philosophy that flourished in and beyond the post-Hellenic world.[13]

Ancient Greek literature, which was translated into Arabic during the Abbasid Caliphate during the 8th and 9th centuries, influenced Islamic currents with rationalism. Many medieval Muslim thinkers pursued humanistic, rational, and scientific discourses in their search for knowledge, meaning, and values. A wide range of Islamic writings on love, poetry, history, and philosophical theology show medieval Islamic thought was open to the humanistic ideas of individualism, occasional secularism, skepticism, liberalism, and free speech; schools were established at Baghdad, Basra and Isfahan.[15]

Renaissance

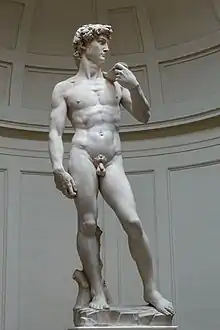

The intellectual movement that was later known as "renaissance humanism" first appeared in Italy. This movement has greatly influenced western culture up until the modern day.[16] Italian scholars discovered Ancient Greek thought, particularly that of Aristotle, through Arabic translations from Africa and Spain.[17] Renaissance humanism emerged in Italy along with the flourishment of literature and the arts in the thirteenth century Italy.[18] One of the first centers of the Greek literature revival was Padua, where Lovato Lovati and others studied ancient texts and wrote new literary works.[19] Other centers were Verona, Naples, and Avignon.[20] Petrarch, who is often referred to as the father of humanism, is a significant figure.[21] Petrarch was raised in Avignon; he was inclined toward education at a very early age and studied alongside his father, who was also well educated. Petrarch's enthusiasm for ancient texts led him to discover manuscripts that were influential for the history of the Renaissance, such as Cicero's Pro Archia and Pomponius Mela's De chorographia. Petrarch wrote poems such as Canzoniere and De viris illustribus in Latin, in which he described humanist ideas; his love for antiquity was evident.[22] His most significant contribution was a list of books he created outlining the four major categories or disciplines (rhetoric, moral philosophy, poetry, and grammar), that would be the base of humanistic studies (studia humanitatis) that were widely adopted for educational purposes. His list relied heavily on ancient writers, especially Cicero.[23]

Revival of classicist authors continued after Petrarch's death. Florence chancellor and humanist Coluccio Salutati made his city a prominent bastion of humanist values. Members of his circle were other notable humanists such as Poggio Bracciolini, Niccolò Niccoli and Leonardo Bruni, who rediscovered, translated and popularized ancient texts.[24] Humanists succeeded in setting the principles of education. Vittorino da Feltre and Guarino Veronese created schools based on humanistic principles, their curriculum was widely adopted and by the sixteenth century, humanistic paideia was the dominant outlook of pre-university education.[25] Parallel with advances in education, humanists in renaissance made progress in other fields, as in philosophy, mathematics and religion. In philosophy, Angelo Poliziano, Nicholas of Cusa , Marsilio Ficino contributed furthering the understanding of ancient classical philosophers and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola undermined the dominance of Aristotelian philosophy with revitalizing Sextus Empiricus skepticism. Religion was not untouched with the increased interest of humanistic paideia, Pope Nicholas V initiated the translation of Hebrew and Greek biblical and other texts to Latin.[26]

Humanist values spread outside of Italy through of books and people. Individuals moving to Italy to study, returned to their homelands and spread humanistic messages. Printing houses dedicated in ancient text established in Venice, Basel and Paris. By the end of fifteenth century, the center of humanism had shifted from Italy to northern Europe, with Erasmus of Rotterdam being the leading humanist scholar. [27] The most profound and longest-lasting effect of Renaissance humanism was their education curriculum and methods. Humanists insisted on the importance of classical literature in providing intellectual discipline, moral standards, and a civilized taste for the elite—an educational approach that reached the contemporary era.[28]

Enlightenment

During the Age of Enlightenment, humanistic ideas resurfaced, this time further from religion and classical literature.[29] Science, reason, and intellectualism advanced, and the mind replaced God as the means with which to understand the world. Divinity was no longer dictating human morals, and humanistic values (such as tolerance and opposition to slavery) started to take shape. Life-changing technological discoveries allowed ordinary people to face religion with a new morality and greater confidence about humankind and its abilities.[29] New philosophical, social, and political ideas appeared. Some thinkers rejected theism outright and various currents were formed; atheism, deism, and hostility to organized religion.[30] Notably during the Enlightenment, Baruch Spinoza redefined God as signifying the totality of nature; Spinoza was accused of atheism but remained silent on the matter.[31] Naturalism was also advanced by prominent Encyclopédistes. Baron d'Holbach wrote the polemic System of Nature, claiming religion is built on fear and helped tyrants through the ages.[32] Diderot and Helvetius also combined their materialism with sharp, political critique.[32]

Also during the Enlightenment, the abstract conception of humankind started forming—a critical juncture for the construction of humanist philosophy. Previous appeals to "Men" now shifted towards "Man"; this is evident in political documents like The Social Contract (1762) of Rousseau, in which he says "Man is born free, but is everywhere in chains". Likewise, Thomas Paine's Rights of Man uses the singular form of the word, revealing a universal conception of Man.[33] In parallel, Baconian empiricism—though not humanism per se—paved the way for Thomas Hobbes's materialism.[34]

Scholar J. Brent Crosson notes that, while it is a wide held belief that the birth of humanism was solely a European affair, the fact was that intellectual thought from other continents such as Africa and Asia contributed significantly as well. He also notes that during enlightenment, the universal Man did not encompass all humans but was shaped by gender and race. He thinks that the shift from man to human is a process that started during enlightenment and is still ongoing.[35]Also, Crosson noted that enlightenment, especially in Britain during scientific revolution, produce not only the notion of universal man and an optimism that reason will prevail over religious superstitions, but also gave birth to pseudoscientific ideas such as race that shaped European history. He gives the paradigm of Africa; Africa was a contribution to knowledge until renaissance, but was disregarded afterwards.[36]

From Darwin to current era

French philosopher Auguste Comte (1798–1857) introduced the idea of a "religion of humanity"—which is sometimes attributed to Thomas Paine—an atheist cult based on some humanistic tenets that had some prominent members but soon declined. It was nonetheless influential during the 19th century, and its humanism and rejection of supernaturalism are echoed in the works of later authors such as Oscar Wilde, George Holyoake—who coined the word secularism—George Eliot, Émile Zola, and E. S. Beesly, further re-enforcing and popularizing the concept of humankind. Paine's The Age of Reason along with the 19th-century Biblical criticism of the German Hegelians David Strauss and Ludwig Feuerbach—both of whom discuss the importance of freedom—created forms of humanism.[37][38]

Advances in science and philosophy further eroded religious belief. Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection offered naturalists an explanation for the plurality of species, weakening the previously convincing teleological argument for the existence of God.[39] Darwin's theory also implied that humans are just another species, contradicting the traditional theological view of humans as something more than just animals.[40] Philosophers Ludwig Feuerbach, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Karl Marx attacked religion on several grounds, and theologians David Strauss and Julius Wellhausen questioned the Bible.[39] In parallel, utilitarianism was developed in Britain through the works of Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill. Utilitarianism, a moral philosophy, centers its attention on human happiness, aiming to eliminate human and animal pain and, in doing so, giving no attention to supernatural phenomena.[41] In Europe and the US, along with philosophical critique of theistic beliefs, large parts of society abandoned or distanced themselves from religion. Ethical societies were formed, leading to the contemporary humanist movement.[42]

The rise of rationalism and the scientific method was followed in the late 19th century in Britain by the birth of many rationalist and ethical associations such as the National Secular Society, the Ethical Union, and the Rationalist Press Association.[38] In the 20th century, humanism was further promoted by the work of philosophers such as A. J. Ayer, Antony Flew, and Bertrand Russell, whose advocacy of atheism in Why I Am Not a Christian further popularized humanist ideas. In 1963, the British Humanist Association evolved out of the Ethical Union and merged with many smaller ethical and rationalist groups. Elsewhere in Europe, humanist organizations also flourished. In the Netherlands, the Dutch Humanist Alliance gained a wide base of support after World War II. In Norway, the Norwegian Humanist Association also gained popular support.[43]

In the US, humanism evolved with the aid of significant figures of the Unitarian Church. Humanist magazines such as The New Humanist, which published the Humanist Manifesto I in 1933, appeared. The American Ethical Union emerged from newly founded, small, ethicist societies.[38] The American Humanist Association (AHA) was established in 1941 and became as popular as some of its European counterparts. The AHA spread to all states, and some prominent public figures such as Isaac Asimov, John Dewey, Erich Fromm, Paul Kurtz, Carl Sagan, and Gene Roddenberry became members.[43] Humanist organizations from all continents have created the International Humanist and Ethical Union (IHEU), which is now known as Humanists International and promotes the humanist agenda via the United Nations organizations UNESCO and UNICEF.[44]

Varieties of humanism

Early 20th century naturalists, who viewed their humanism as a religion and participated in church-like congregations, used the term "religious humanism". Religious humanism appeared mostly in the US and is now rarely practiced. The American Humanist Association arose from religious humanism.[45] The same term has also been used by religious groups such as the Quakers to describe themselves but the term is misapplied in those cases.[46]

The term "Renaissance humanism" was later given to a tradition of cultural and educational reform engaged in by civic and ecclesiastical chancellors, book collectors, educators, and writers who, by the late 15th century, began to be referred to as umanisti ("humanists"). It developed during the 14th and early 15th centuries.[47] While modern humanism's roots can be traced to the Renaissance, "Renaissance humanism" differs from it vastly.[48][49]

Other terms using "humanism" in their name include:

- "Christian humanism": a historical current in the late Middle Ages, where Christian scholars combined Christian faith with interest in classical antiquity and a focus on human well-being.[50]

- "Ethical humanism": a synonym of Ethical culture, was prominent in the US in early the 20th century, focused on relations between humans. [51]

- "Scientific humanism": emphasises belief in the scientific method as a component of humanism, as in the works of John Dewey and Julian Huxley. Largely synonymous with secular humanism.[52]

- "Secular humanism" was coined in the mid-20th century. It was initially an attempt to denigrate humanism but was embraced by some humanist associations.[53] It is synonymous with the contemporary humanist movement.[54]

- "Marxist humanism": one of several rival schools of Marxist thought, which accepts basic humanistic tenets (secularism, naturalism) but differs to other humanism because of its vague stance on democracy and rejection of free will.[55]

Philosophy

Immanuel Kant provided the underpinning of the humanist narrative. His theory of critical philosophy laid down the foundations the world of knowledge, defending rationalism and grounding it, along with his anthropology (his study of psychology, ethics, and human nature) to the empirical world.[56] He also supported the idea of moral autonomy of the individual, which was fundamental to his philosophy, deducing that morality is the product of the way we live, it is not a preset of fixed values. Instead of a universalistic ethic code, Kant suggested a universalistic procedure that shapes the various ethics that differ among various group of people.[57]

Humanism is strongly based on reason.[58] For humanists, humans are reasonable beings but reasoning and the scientific method are the means of finding truth.[59] Science and reason have gained widespread approval due to their tremendous successes in various fields.[60] Appeals to irrationality and invocation of supernatural phenomena have failed to coherently explain the world. One form of irrational thinking is adducing hidden agencies to explain natural phenomena or diseases; humanists are skeptical of these kinds of explanations.[61]

The hallmark of humanist philosophy is human autonomy.[62] For people to be autonomous, their beliefs and actions must be the result of their own reasoning.[62] For humanists, autonomy dignifies each individual—without autonomy, people are reduced to being less than humans.[63] They also consider human essence to be universal, irrespective of race or social status, diminishing the importance of collective identities and signifying the importance of individuals.[64]

Philosopher and humanist advocate Corliss Lamont, in his book The philosophy of humanism (1997) states that "In the Humanist ethics the chief end of thought and action is to further this-earthly human interests on behalf of the greater glory of people. The watchword of Humanism is happiness for all humanity in this existence as contrasted with salvation for the individual soul in a future existence and the glorification of a supernatural Supreme Being...It heartily welcomes all life-enhancing and healthy pleasures, from the vigorous enjoyments of youth to the contemplative delights of mellowed age, from the simple gratifications of food and drink, sunshine and sports, to the more complex appreciation of art and literature, friendship and social communion...". [65]

Criticism of humanism

Criticism of humanism focuses on its adherence to human rights, which some critics have further claimed are "Western". Critics claim humanist values are becoming a tool of Western moral dominance, which is a form of neo-colonialism leading to oppression and a lack of ethical diversity.[66] Other critics argue humanism is an oppressive philosophy because it is not free from the biases of the white, heterosexual males who shaped it.[67] History professor Samuel Moyn attacks humanism for its advocacy of human rights. According to Moyn, in the 1960s, human rights were a declaration of anti-colonial struggle but during the 1970s, they were transformed into a utopian vision, replacing the failing utopias of the 20th century. The humanist underpinning of human rights transforms them into a moral tool that is impractical and ultimately non-political. He also finds a commonality between humanism and the Catholic discourse on human dignity.[68]

Anthropology professor Talal Asad sees humanism as a project of modernity and a secularized continuation of Western Christian theology. In Asad's view, just as the Catholic Church passed the Christian doctrine of love to Africa and Asia while assisting in the enslavement of large parts of their population, humanist values have at times been a pretext for Western countries to expand their influence to other parts of the world to humanize "barbarians".[69] Asad has also argued humanism is not a purely secular phenomenon but takes from Christianity the idea of the essence of humanity.[70] Asad is not optimistic Western humanisms can incorporate other humanistic traditions such as those from India and China without subsuming and ultimately eliminating them.[71]

Sociology professor Didier Fassin sees humanism's focus on empathy and compassion rather than goodness and justice as a problem. According to Fassin, humanism originated in the Christian tradition, particularly the Parable of the Good Samaritan, in which empathy is universalized. Fassin also claims humanism's central essence, the sanctity of human life, is a religious victory hidden in a secular wrapper.[72]

Another line of argumentation of Humanism is it is being against traditional values, and ultimate it destroys family and family values.[65] A similar line, in a more religious tone, argues that materialism of humanism diminishes human as a something without a soul, without a higher nature, or being a reflection of God.[73]

Antihumanism

Antihumanism is the rejection of humanism on the ground it is a pre-scientific ideology.[74] This argument developed during the 19th and 20th centuries in parallel with the advancement of humanism. Prominent thinkers questioned the metaphysics of humanism and the human nature of its concept of freedom.[67] Nietzsche, while departing from a humanistic, pro-Enlightenment viewpoint, criticized humanism for illusions on a number of topics, especially the nature of truth. For him, objective truth is an anthropomorphic illusion and humanism is meaningless.[75] Nietzsche also argued replacing theism with reason, science, and truth is nothing but replacing one religion with another.[76]

According to Karl Marx, humanism is a bourgeois project that attempts to present itself as radical but is not.[77] After the atrocities of World War II, questions about human nature and the concept of humanity were renewed.[78] During the Cold War, influential Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser introduced the term "theoretical antihumanism" to attack both humanism and socialist currents that leaned towards humanism, eschewing more structural and formal interpretations of Marx. According to Althusser, Marx's early writings resonate with the humanistic idealism of Hegel, Kant, and Feuerbach but Marx took a radical turn towards scientific socialism in 1845, rejecting concepts such as the essence of man.[79] Other antihumanists such as Martin Heidegger and Michel Foucault attacked the notion of humanity using psychoanalysis, Marxism, and linguistic theory.[80]

Themes

Humanism and morality

The humanist attitude towards morality has changed through the centuries. During the modern era, starting in the 18th century, humanists were oriented towards an objective and universalist stance on ethics. Both Utilitarian philosophy, which aims to increase human happiness and decrease human suffering, and Kantian ethics—acting only according to that maxim whereby you can, at the same time, will that it should become a universal law—shaped the humanist moral narrative until the early 20th century. Because the concepts of free will and reason are not based on scientific naturalism, their influence on humanists remained in the early 20th century but was reduced by social progressiveness and egalitarianism.[81] Along with the social changes nations faced in the late 20th century, humanist ethics evolved to be a constant voice supporting secularism, civil rights, personal autonomy, religious toleration, multiculturalism, and cosmopolitanism.[82]

A naturalistic criticism to humanistic morality is the denial of the existence of morality. For naturalistic skeptics, morality was never wired within humans, during the evolutionary process that created humans, who are primarily selfish and self centered.[83] Defending humanism morality, Humanist scholar and philosopher John R. Shook makes three observations that lead him to the acceptance of morality. First he notices that homo sapiens have a conception of morality, this concept must have been with us since the beginning of human history and must have been created by noticing and thinking upon behaviors. He also adds that morality is a universal finding among human cultures and all cultures strive to improve their moral level. Spook concludes that while morality was initially generated by our genes, culture also shaped and is shaping human morals. He calls "moral naturalism" the view that morality is a natural phenomenon, can be scientifically studied and Morality is seen as a tool aiming for the flourishing of human rather than a set of doctrines.[84]

Humanist philosopher Brian Ellis argues for a social humanist theory of morality called "social contractual utilitarianism", which is built on Hume's naturalism and empathy, Aristotelian virtue theory, and Kant's idealism. According to Ellis, morality should aim for eudaimonia, an Aristotelian concept that combines a satisfying life with virtue and happiness by improving societies on a global scale.[85] Humanist Andrew Copson takes a consequentialist and utilitarian approach to morality. According to Copson, humanist ethical traits all aim at human welfare.[86] Philosopher Stephen Law emphasizes certain principles of humanist ethics; respect for personal moral autonomy, rejection of god-given moral commands, an aim for human well-being, and "emphasiz[ing] the role of reason in making moral judgements".[87]

Humanism's godless approach to morality has driven religious criticism. A popular belief, for morals to exist there must be a divinity delivering sets of doctrines, is illustrated by Dostoevsky's axiom in The Brothers Karamazov; "if God does not exist, then everything is permitted". It implies that chaos will ensue if religious belief disappears.[88] For humanists, theism is an obstacle to morality rather than a precondition for it.[89] According to humanists, if people act only out of fear, blind adherence to a dogma, or expectation of a reward, it is a selfish motivation rather than morality.[90] Humanists point to the subjectivity of the supposed objective divine commands by referring to the Euthyphro dilemma; "does God command something because it is good or is something good because God commands it?" If goodness is independent from God, humans can reach goodness without religion but relativism is invited if God creates goodness.[91] Another line of arguing against this religious criticism, is that ultimately, even through religious means, morality is human-mane. The interpretation of holy scriptures almost always includes human reasoning; interpreters reach contradictory theories, indicating morality is based on human reasoning.[92]

Humanism and religion

Humanism has been widely seen as antithetical to religion.[93] Philosopher of religion David Kline, traces the roots of this animosity since renaissance, when humanistic views deconstructed of the previous religiously defined order. Kline describes various ways this antithesis has evolved. Firstly, Kline notes, that the emergence of a confident human-made knowledge, which was a new way of epistemology, repelled the church from its previous authoritative place. Kline uses the paradigm of non-humanist Copernicus, Kepler and Galileo, to illustrate how scientific discoveries added to the deconstruction of the religious narrative in favor of human generated knowledge. That ultimately delinked the fate of human from the divine will prompting social and political shifts [94] The relation of state and citizens changed as civic humanistic principles emerged, where people were not meant to be servile to religiously grounded monarchies anymore, but could pursue their own destiny.[95] Kline also points at the aspect of personal beliefs, that added to the hostility among humanism and religion. Humanism was associated with prominent thinkers that advocated on a rational basis against the existence of God. Critique of theism continued through the various (humanistic) revolutions in Europe, constantly challenging religious worldview, attitudes and superstitions on a rational basis- a tendency that continued to the 20th century.[96]

According to Stephen Law, Humanism adherence to secularism place him at odds with religion, especially dominant religion in each country striving to retain privileges gained the last centuries. Worth noting that religious persons can be, and indeed many are, secularists. Law notices a line of criticism against secularism, that it suppress freedom of expression of religious persons but firmly denies such accusation- instead he says, he protects this kind of freedom- it just opposes privilege status of religious views. [97]

Prominent humanist Andrew Copson adopts a more peaceful stance against religion. For Copson, humanism is not incompatible with various aspects of religion. Copson sees various domains in religion: Belief, practice, identity and cultural, in which a person adhering to few religious domains could also be humanist.[98] Copson adds that religious critics usually frame humanism as an enemy of religion, but in contrary, most humanists are proponents of religious tolerance or exhibit a curiosity on religions effects in society politics, commenting "Only a few are regularly outraged by other people’s false beliefs per se."[99]

Humanism and the meaning of life

In the 19th century, the problem of the meaning of life arose, along with the decline of religion and its accompanied teleology, puzzling both society and philosophers.[100] Unlike religions, humanism does not have a definite view on the meaning of life.[101] Humanists commonly say people create rather than discover meaning. While many philosophers such as Kierkegaard, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche wrote on the meaning of life in a godless world, the work of Albert Camus has echoed and shaped humanism. In The Myth of Sisyphus, the absurd hero Sisyphus is destined to push a heavy rock up to a hill; the rock slips back and he must repeat the task.[102]

Personal humanist interpretations of the meaning of life vary from the pursuit of happiness without recklessness and excesses to participation in human history and connection with loved ones, living animals, and plants.[101][lower-alpha 1] Some answers are not far from those of religious discourse if the appeal to divinity is overlooked.[104] According to humanist professor Peter Derks, the features that contribute to the meaning of life are: having a purpose in life that is morally worthy, positively evaluating oneself, having an understanding of one's environment, being seen and understood by others, the ability to connect emotionally with others, and a desire to have a meaning in life.[105] Humanist professor Anthony B. Pinn places the meaning of life in the quest of what he calls "complex subjectivity". Pinn, who is advocating for a non-theistic, humanistic religion inspired by African cultures, says seeking the never-reaching meaning of life contributes to well-being. Pinn argues rituals and ceremonies, which are times for reflection, provide an opportunity to assess the meaning of life, improving well-being.[106]

Well-being and the living of a good life have been at the center of humanist reflection. For humanists, well-being is intertwined with values that arise from the meaning of life that each human sets for him or herself.[107] Humanist philosopher Bertrand Russell described the good life as one "inspired by love, guided by knowledge".[108] A.C. Grayling noted a good life "is the life that feels meaningful and fulfilling to the one living it".[109] Despite the platitudes, humanism does not have a doctrine of good life nor offers any certainties; each person should decide for herself what constitutes a good life.[110] For humanists, it is vital the option for a meaningful and fulfilling life is open to all members of society.[111]

Humanism in politics

The hallmark of contemporary humanism in the political arena, is the demand for secularism.[112] Philosopher Alan Haworth, says that secularism deliver fair treatment to all citizens of a State, since all are treated without discrimination, since religion is a private issue and the state should have no say over it.[113] He also adds secularism helps plurality and diversity, that are fundamental aspects of our modern world.[114] Haworth, also examines political objections to humanist call for secularism. He examines the conservative argument of Edmund Burke that calls for common sense instead of abstract reasoning, and preserving traditional and Christian values and puts importance on national continuity. Haworth sees that Christian Values have not stopped Europeans committing atrocities in Europe and elsewhere. While this kind of barbarism can be found in most civilizations, Haworth notes that religions usually fuels rhetoric and enable these actions. More, he adds, the values of hard work, honesty, charity and likewise, are also to be found in other civilizations. [115] Humanism, Haworth adds, also opposes the irrationality of nationalism and totalitarianism, whether these be part of fascism or Marxist–Leninist communism.[116]

According to professor Joseph O. Baker, in political theory, contemporary humanism is sculptured by two main axons. The first is more individualistic, and the second inclines to collectivism. The trajectory of these two axons leads to libertarianism and socialism respectively, but a whole range of various combinations exist. Individualistic humanists often have a philosophical perspective of humanism, in the political arena are inclined to libertarianism and in ethics tend to follow a scientistic approach. Those who lean to collectivism, have a more applied view of humanism, they lean towards socialism and have a humanitarian approach in ethics.[117] The second group has some connections with the thought of young Marx, especially his anthropological views rejecting his political practices.[118] A factor that holds many humanists away from the libertarian view, is the consequences they feel it bears. Libertarianism is tied to neoliberalism and capitalistic society that is conceived to be inhumane.[119]

Historically, humanism has been a part of both major 20th-century ideological currents—liberalism and Marxism. Early 19th-century socialism was connected to humanism. In the twentieth century, a humanistic interpretation of Marxism focused on Marx's early writings, viewing Marxism not as a "scientific socialism" but as a philosophical critique aimed at the overcoming of "alienation". In the US, liberalism is associated mostly with humanistic principles, which is distinct from the European use of the same word, which has economical connotations.[120] In the Post-War era, Jean-Paul Sartre and other French existentialists advocated for humanism, tying it to socialism while trying to stay neutral during the Cold War.[121]

Humanist psychology and counselling

Humanist counseling is the applied psychology inspired by humanism, which is one of the major currents of counseling. There are various approaches such as discussion and critical thinking, replying to existential anxiety, and focusing on social and political dimensions of problems.[122] Humanist counseling focuses on respecting the worldview of clients and placing it in the correct cultural context. The approach emphasizes an individual's inherent drive towards self-actualization and creativity. It also recognizes the importance of moral questions about the way one should interact with people according to one's worldview. This is examined using a process of dialogue.[123] Generally, humanist counseling aspires to help people to live a good, fulfilling, and meaningful life by continual interpretation and reflection.[124] Humanist counseling originated in the post-World War II Netherlands.[125]

Humanistic counseling, a different term from humanist counseling, is based on the works of psychologists Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow. It introduced a positive, humanistic psychology in response to what they viewed as the over-pessimistic view of psychoanalysis in the early 1960s. Other sources include the philosophies of existentialism and phenomenology.[125]

Some modern counselling organisations have humanist origins, like the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy in the UK, which was founded by Harold Blackham, which he developed alongside the British Humanist Association's Humanist Counselling Service.[126] Modern-day humanist pastoral care in the UK and the Netherlands also draws on elements of humanistic psychology.[127]

Geographies of humanism

Africa

In Africa, contemporary humanism has been shaped from its colonial history and the introduction of Christianity and Islam. African philosophers focused on the interdependency among humans and among humans and nature.[128] Pre-colonial oral traditions reflecting African views on human and human good, were eliminated by the conquer of European powers. Christianity and Islam advanced and many intra-African atrocities took place. Even so, Africans never abandoned the ideas of human value and the mutual interdependence of humans, which are core features of African humanism. This idea was advanced by philosophers such as Kwasi Wiredu and Jean-Godefroy Bidima. Wiredu emphased the need of human interaction for human to become what he is, and projected his thought to the need for democracy. Bidima added that the interaction should be enduringly since history and humans are constantly evolving.[129] Socialist philosopher Léopold Sédar Senghor, Africans were naturally leaning towards humanism (and socialism), not because of its scientific or epistemological basis, but because of their intuition.[130]

Middle East

It is a wide-held view, that in middle East, due to the dominance of Islam, humanistic values found a hostile environment and were unable to flourish.[131] Even though, scholar Khurram Hussain identifies some traits among early Islam world which he thinks they resonate with humanism. He notes that Islam unified a diverse population and provided political, epistemological and social solutions to the then fragmented Arab world.[132] Also, Hussain argues that there is a form of humanism within the Islamic anthropology. To support his argument, he notes various examples (i.e. the lack of "original sin") indicating that in Islamic theology, human is a free moral agent. He also points to the thought of Islamic scholars as Ibn al-‛Arabī and al-Jīlī that placed human in the centre of the universe, a place held for God in Christian traditions. [133] Khurram Hussain also notes the Arab Spring of 2011 reviled that humanistic values (as democracy, freedom, fairness) are popular in Middle East and are not inheritable incompatible from Islam.[134]

East Asia

In East Asia, Confucianism's core ideas are humanistic.[135] The philosophy of Confucius (551–479 BCE), which eventually became the basis of the state ideology of successive Chinese dynasties and nearby polities in East Asia, contains several humanistic traits, placing a high value on human life, and discounting mysticism and superstition, including speculations on ghosts and an afterlife.[136] Confucianism is considered a religious form of humanism because supernatural phenomena such as Heaven (tian)—which supposedly guides the world—have a place in it.[137] In the Analects of Confucius, humanist features are apparent; sinologist Theodore de Bary spots respectfulness, reasonableness, kindness, and enthusiasm for learning. A fundamental teaching of Confucius was that a person can become a junzi (someone who is noble, just, or kind) through education. Without religious appeals, Confucius advised people to act according to an axiom that is the negative mirror of the Western golden rule: "Is there one word that one can act upon throughout the course of one's life?" According to Confucius; "Reciprocity [shu]—what you would not want for yourself, do not do to others". (Analects 15:23) After Confucius' death, his disciple Mencius (371–289 BCE) centered his philosophies on secular, humanistic concerns like the nature of good governance and the role of education rather than ideas founded on the state or folk religions of the time.[138] Societies in China, Japan and Korea were shaped by the prevalence of humanistic Confucianism.[135]

Early Taoism also holds some humanistic tenets. Taoism developed initially as a naturalistic philosophy, aiming to the harmony of self, society and the universe. Naturalness is the goal that is achieved by wu‐wei (non‐action), and the fundamental book of Taoism Tao Te Ching is based on humanistic thought according to philosopher Michael LaFargue.[139] Buddhism also has been seen to bear elements of humanistic thought. This is because Buddhism aims to the salvage human from the sorrows of life, after abandoning egoistic tendencies and coming in peace with society and universe.[140]

North America

In the United States, constitution was shaped by humanistic ideas endorsed as part of the Enlightenment of the first presidents of the United States, but did not go far enough to tackle gender and race inequality issues.[141] Professor of Religious Studies Carol Wayne White notes that Black communities experiencing injustice leaned towards atheism in the 20th Century. Lately, many black organizations rejecting theism or having a humanistic related agenda are loosely connected within the Black Lives Matter movement.[142] Black literature reveals the quest for freedom and justice in a community often subordinated to white dominance.[143]

Latin America

Humanism in Latin America is hard to detect mainly because of the dominance of Catholicism and Protestantism.[144] European positivism had influenced the thought of scholars and political leaders in Latin America during the 19th century but its influences waved at the next century.[145] In recent years, humanist organizations have multiplied in Latin America.[144]

Europe

In Europe, various currents of 19th century though as freethinkers, ethicists, atheists and rationalists have merged to form the contemporary humanist movement.[146] Various national organizations founded the European Humanist Federation (EHF) in 1991, affirming their strong support of secularism. All humanistic organizations strongly promote a naturalistic world view, scientific approach, individualism and solidarity but they vary in terms of their practice. One line is that they should focus to meet the needs of nonreligious peoples or their members, the other one is pursuing activism in order to bring social change. These two main patterns in European humanism, that coexist within humanist organizations often collude with each other.[147]

Demographics of humanism

Humanists demographic data are sparse. Scholar Yasmin Trejo examined the results of a Pew Research Center's Religious Landscape Study, that was released in 2014.[148] Trejo did not use self-identification as a method to measure humanists, but combined the answers of 2 particular questions: "Do you believe in God or a universal spirit?" (she picked those answering "no") and "when it comes to questions of right or wrong, which of the following do you look to most for guidance?" (picking answers "scientific information" and "philosophy and reason"). Trejo finds that most humanists identify as atheist or agnostics (37% and 18%), 29% as "nothing in particular", while 16% of humanists identify as religious (following religious traditions).[149] She also found that most humanists (80%) were raised having a religious background. [150] 6 out of 10 humanists are married to non-religious spouses, while one in four humanists are married to a Christian.[151] There is a gender divide among Humanists, most of them being males (67%) Trejo suggests that this can be explained by the fact that more atheists are males, while women are not easily drifted away from religion because of socialization, community influence and stereotypes.[152] Other findings is the high education level of most humanists (higher than general population) that indicates a higher socioeconomic status.[153] Finally, the overwhelming population of humanists is non-Hispanic Whites; Trejo's explanations is that minority groups are usually very religious.[154]

Humanist organizations

Humanist organizations exist in several countries. Humanists International is a global organization.[155] Humanists UK (formerly the British Humanist Association) and the American Humanist Association are two of the oldest humanist organizations.

London-based Humanists UK has around 28,000 members and a budget of over £1 million (2015 figures) to cover operational costs. Its membership includes some high-profile people such as Richard Dawkins, Brian Cox, Salman Rushdie, Polly Toynbee, and Stephen Fry, who are mostly known for their participation in public debate, promoting reason, science and secularism, and objecting to state funding for faith-based events or institutes.[156] Humanists UK organizes and conducts non-religious[157] ceremonies for weddings, namings, coming of age, and funerals. According to Stephen Law, ceremonies and rituals exist in our culture because they help humans express emotions rather than having a magical effect on the participants.[158]

The American Humanist Association was formed in 1941 from previous humanist associations. Its journal The Humanist is the continuation of a previous publication The Humanist Bulletin.[44] In 1953, the AHA established the "Humanist of the Year" award to honor individuals who promote science.[159] A few decades later, it became a well-recognized organization, initiating progressive campaigns for abortion rights and opposing discriminatory policies, resulted in it becoming a target of the religious right by the 1980s.[160] High-profile members of academia and public figures have published work in The Humanist, and joined and lead the AHA.

See also

- Alternatives to the Ten Commandments – secular and humanist alternatives

- Amsterdam Declaration

- Anthropocentrism

- Community organizing

- Extropianism

- Existentialism Is a Humanism, by Jean-Paul Sartre

- John N. Gray

- Human dignity

- Humanist celebrant

- Humanistic Buddhism

- Humanistic economics

- Humanist International

- Humanist Movement

- Humanistic psychology

- Humanitas

- HumanLight

- Index of humanism articles

- Letter on Humanism by Martin Heidegger

- List of humanists

- Materialism

- Misanthropy

- Natural rights

- Objectivity (philosophy)

- Paideia

- Pluralistic Rationalism

- Post-theism

- Religious humanism

- Secular humanism

- Sentientism

- Social psychology

- Soka Gakkai

- Unitarian Universalism

- Ubuntu

Notes

- To illustrate the importance of pursuing happiness without excesses, Andrew Copson quotes Epicurus: "When I say that pleasure is the goal of living I do not mean the pleasures of libertines ... I mean, on the contrary, the pleasure that consists of freedom from bodily pain and mental agitation. Pleasant life is not the product of one drinking party after another or sexual intercourse with women and young men or of the seafood and other delicacies afforded by the serious table. On the contrary, it is the result of sober thinking ... " Copson is citing 66 Epicurus, Letter to Menoeceus, in The Art of Happiness, trans. Strodach, p. 159.[103]

References

- Harper.

- Mann 1996; Copson 2015, pp. 1–2.

- Copson 2015, pp. 1–2; Fowler 1999, pp. 18–19.

- Davies 1997, pp. 9–10.

- Copson 2015, pp. 3–4.

- Davies 1997, p. 3–5.

- Hook 1974, pp. 31–33.

- Blackham 1974, pp. 35–37.

- Fowler 1999, p. 9.

- Copson 2015, pp. 6–24.

- Copson 2015, pp. 5–6; Fowler 1999, p. 11.

- Cherry 2009, p. 26.

- Law 2011, chapter History of Humanism, #Ancient Greece.

- Lamont 1997, pp. 34–35.

- Goodman 2003, p. 155; Ljamai 2015, pp. 153–56.

- Monfasani 2020, p. 1.

- Mann 1996, pp. 14–15.

- Monfasani 2020, p. 4; Nederman 2020.

- Mann 1996, p. 6.

- Mann 1996, p. 8.

- Mann 1996, p. 8; Monfasani 2020, p. 1.

- Mann 1996, pp. 8–14.

- Monfasani 2020, p. 8:That was the reason Cicero was name as the grandfather of humanism by classicist scholar Berthold Ullman

- Monfasani 2020, pp. 9–10.

- Monfasani 2020, p. 10.

- Monfasani 2020, pp. 10–11.

- Monfasani 2020, pp. 12–13.

- Kristeller 2008, p. 114.

- Fowler 1999, p. 16.

- Fowler 1999, p. 18.

- Lamont 1997, p. 74.

- Lamont 1997, p. 45.

- Davies 1997, p. 25.

- Davies 1997, pp. 108–09.

- Crosson 2020, pp. 1–3.

- Crosson 2020, pp. 5–6.

- Davies 1997, pp. 26–30.

- Hardie 2000, 19th Century.

- Law 2011, p. 36.

- Lamont 1997, p. 75.

- Law 2011, p. 37.

- Law 2011, p. 39.

- Hardie 2000, 20th Century.

- Morain & Morain 1998, p. 100.

- Wilson 1974, p. 15; Copson 2015, pp. 3–4.

- Fowler 1999, p. 20.

- Mann 1996, pp. 1–2.

- Norman 2004, p. 14.

- Copson 2015, pp. 2–3.

- Wilson 1974, p. 15.

- Wilson 1974, pp. 15–16.

- Wilson 1974, p. 16.

- Copson 2015, p. 2.

- Fowler 1999, pp. 21–22.

- Lamont 1997, pp. 28–29; Davies 1997, pp. 56–57.

- Walker 2020, pp. 4–6.

- Dierksmeier 2011, p. 79; Rohlf 2020, Morality and freedom.

- Law 2015, p. 55.

- Law 2015, p. 58.

- Law 2015, p. 57.

- Law 2015, pp. 57–61.

- Nida-Rümelin 2009, p. 17.

- Norman 2004, p. 104.

- Nida-Rümelin 2009, pp. 16–17.

- Lamont 1997, p. 248.

- Jakelić 2020, p. 2.

- Childers & Hentzi 1995, pp. 140–41.

- Jakelić 2020, pp. 12–14.

- Jakelić 2020, pp. 3–6.

- Jakelić 2020, p. 6.

- Jakelić 2020, pp. 6–7.

- Jakelić 2020, pp. 7–8.

- Norman 2004, p. 56.

- Soper 1986, pp. 11–12.

- Davies 1997, pp. 36–37.

- Soper 1986, pp. 12–13.

- Davies 1997, p. 40.

- Davies 1997, pp. 50–52.

- Davies 1997, pp. 57–60.

- Norman 2004, pp. 75–77.

- Norman 2004, pp. 98–105; Shook 2015, p. 406.

- Shook 2015, pp. 421–422.

- Shook 2015, pp. 407–408.

- Shook 2015, pp. 407-410 & 421.

- Ellis 2010, pp. 135–37.

- Copson 2015, pp. 21–22.

- Law 2011, Humanism and morality.

- Norman 2004, p. 86.

- Norman 2004, p. 86; Shook 2015, pp. 404–05.

- Norman 2004, pp. 89–90.

- Norman 2004, pp. 88–89; Shook 2015, p. 405.

- Norman 2004, pp. 87–88; Shook 2015, p. 405.

- Kline 2020, pp. 224–225.

- Kline 2020, pp. 225–232.

- Kline 2020, pp. 230–236.

- Kline 2020, pp. 236–240.

- Law 2015, Humanism and secularism.

- Copson 2015, p. 25.

- Copson 2015, pp. 25–28: Stephen Law makes a similar argument at ‘’Humanism, a very short introduction’’ (2011) at page 23

- Norman 2015, pp. 326–28.

- Norman 2015, p. 341.

- Norman 2015, pp. 334–35.

- Copson 2015, p. 15.

- Law 2011, Chapter: The meaning of life, part: Humanism and the meaning of life.

- Butler 2020, pp. 2–3.

- Butler 2020, pp. 3–4.

- Butler 2020, p. 17.

- Fowler 1999, pp. 178–79.

- Grayling 2015, p. 92.

- Fowler 1999, pp. 179–81; Grayling 2015, pp. 90–93.

- Copson 2015, pp. 23–24; Butler 2020, p. 17.

- Haworth 2015, pp. 255–256.

- Haworth 2015, pp. 259–261.

- Haworth 2015, pp. 261–262.

- Haworth 2015, pp. 263–66.

- Haworth 2015, pp. 263–77.

- Baker 2020, pp. 1–7.

- Baker 2020, pp. 8–9.

- Baker 2020, pp. 10–11.

- Nida-Rümelin 2009, pp. 17–18.

- Soper 1986, pp. 79–81.

- Schuhmann 2015, pp. 173–82.

- Schuhmann 2015, pp. 182–88.

- Schuhmann 2015, pp. 188–89.

- Schuhmann 2015, pp. 173–74.

- "Harold John Blackham". Humanist Heritage. Humanists UK. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- Savage 2021.

- Masolo 2020, p. 1.

- Masolo 2020, pp. 23–25.

- Masolo 2020, p. 3.

- Hussain 2020, pp. 1–2.

- Hussain 2020, pp. 4–5.

- Hussain 2020, pp. 8–12.

- Hussain 2020, pp. 12.

- Huang 2020, pp. 1–2.

- Law 2011, chapter History of Humanism, #Confucius.

- Heavens 2013, pp. 31–35; Yao 2000, pp. 44–45.

- Fowler 2015, pp. 133–37.

- Fowler 2015, pp. 139-141 & 147.

- Fowler 2015, p. 147.

- White 2020, p. 20.

- White 2020, pp. 20–21.

- White 2020, p. 19-20.

- White 2020, p. 19.

- White 2020, p. 17-18.

- Schröder 2020, p. 1.

- Schröder 2020, pp. 13–14.

- Trejo 2020, pp. 1–3.

- Trejo 2020, p. 8.

- Trejo 2020, pp. 11–12.

- Trejo 2020, p. 14.

- Trejo 2020, p. 16.

- Trejo 2020, p. 18.

- Trejo 2020, p. 19.

- Norman 2004, p. 160.

- Engelke 2015, pp. 216–18.

- Engelke 2015, pp. 216–21.

- Law 2011, pp. 138–40.

- Morain & Morain 1998, pp. 105–12.

- Morain & Morain 1998, pp. 100–05.

Sources

- Baker, Joseph O. (2020). "The Politics of Humanism". In Anthony B. Pinn (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Humanism. Pemberton. pp. 1–20. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190921538.013.20. ISBN 978-0-19-092153-8.

- Blackham, H. J. (1974). "A definition of humanism". In Paul Kurtz (ed.). The Humanist Alternative: Some Definitions of Humanism. Pemberton. ISBN 978-0-87975-013-8.

- Butler, Philip (2020). "Humanism and the Conceptualization of Value and Well-Being". In Anthony B. Pinn (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Humanism. Pemberton. pp. 644–664. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190921538.013.20. ISBN 978-0-19-092153-8.

- Cherry, Matt (2009). "The Humanist Tradition". In Heiko Spitzeck (ed.). Humanism in Business. Shiban Khan, Ernst von Kimakowitz, Michael Pirson, Wolfgang Amann. Cambridge University Press. pp. 26–51. ISBN 978-0-521-89893-5.

- Childers, Joseph W.; Hentzi, Gary (1995). The Columbia Dictionary of Modern Literary and Cultural Criticism. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-07242-7.

- Copson, Andrew (2015). "What is Humanism?". In A. C. Grayling (ed.). The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Humanism. Andrew Copson. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–72. ISBN 978-1-119-97717-9.

- Crosson, J. Brent (2020). "Humanism and Enlightenment". In Anthony B. Pinn (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Humanism. Pemberton. pp. 1–35. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190921538.013.33. ISBN 978-0-19-092153-8.

- Davies, Tony (1997). Humanism. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-11052-5.

- Dierksmeier, Claus (2011). "Kant's Humanist Ethics". In C. Dierksmeier; W. Amann; E. Von Kimakowitz; H. Spitzeck; M. Pirson; Ernst Von Kimakowitz (eds.). Humanistic Ethics in the Age of Globality. Springer. pp. 79–93. ISBN 978-0-230-31413-9.

- Ellis, Brian (30 March 2010). "Humanism and Morality". Sophia. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 50 (1): 135–139. doi:10.1007/s11841-010-0164-x. ISSN 0038-1527. S2CID 145380913.

- Engelke, Matthew (2015). "Humanist Ceremonies: The Case of Non-Religious Funerals in England". In A. C. Grayling (ed.). The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Humanism. Andrew Copson. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 216–233. ISBN 978-1-119-97717-9.

- Fowler, Jeaneane D. (1999). Humanism: Beliefs and Practices. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-898723-70-7.

- Fowler, Merv R (2015). "Ancient China". In A. C. Grayling (ed.). The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Humanism. Andrew Copson. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 133–152. ISBN 978-1-119-97717-9.

- Goodman, Lenn E. (2003). Islamic Humanism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-988500-8.

- Grayling, A.C. (2015). "The Good and Worthwhile Life". In A. C. Grayling (ed.). The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Humanism. Andrew Copson. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 87–84. ISBN 978-1-119-97717-9.

- Harper, Douglas. "Humanism". Online Etymological Dictionary. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Jakelić, Slavica (2020). "Humanism and Its Critics". In Anthony B. Pinn (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Humanism. Pemberton. pp. 264–293. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190921538.013.8. ISBN 978-0-19-092153-8.

- Hardie, Glenn M (2000). "Humanist history: a selective review". Humanist in Canada. Gale Academic OneFile (132): 24–29, 38.

- Haworth, Alan (2015). "Humanism and the Political Order". In A. C. Grayling (ed.). The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Humanism. Andrew Copson. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 255–279. ISBN 978-1-119-97717-9.

- Heavens, Timothy (2013). "Confucianism as humanism" (PDF). CLA Journal (1): 33–41.

- Hook, Sidney (1974). "The snare of definitions". In Paul Kurtz (ed.). The Humanist Alternative: Some Definitions of Humanism. Pemberton. ISBN 978-0-87975-013-8.

- Huang, Chun-chien (2020). "Humanism in East Asia". In Anthony B. Pinn (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Humanism. Pemberton. pp. 1–29. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190921538.013.31. ISBN 978-0-19-092153-8.

- Hussain, Khuram (2020). "Humanism in the Middle East". In Anthony B. Pinn (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Humanism. Pemberton. pp. 1–17. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190921538.013.35. ISBN 978-0-19-092153-8.

- Kline, David (2020). "Humanism Against Religion". In Anthony B. Pinn (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Humanism. Pemberton. pp. 224–244. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190921538.013.20. ISBN 978-0-19-092153-8.

- Kristeller, Paul Oskar (2008). "Humanism". In C. B. Schmitt; Quentin Skinner; Eckhard Kessler; Jill Kraye (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Renaissance Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 111–138. ISBN 978-1-139-82748-5.

- Monfasani, John (2020). "Humanism and the Renaissance". In Anthony B. Pinn (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Humanism. Oxford University Press. pp. 150–175. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190921538.013.30. ISBN 978-0-19-092153-8.

- Ljamai, Abdelilah (2015). "Humanistic Thought in the Islamic World of the Middle Ages". In A. C. Grayling (ed.). The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Humanism. Andrew Copson. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 153–169. ISBN 978-1-119-97717-9.

- Law, Stephen (2011). Humanism: A Very Short Introduction. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-161400-2.

- Law, Stephen (2015). "Science, Reason, and Scepticism". In A. C. Grayling (ed.). The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Humanism. Andrew Copson. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 55–71. ISBN 978-1-119-97717-9.

- Lamont, Corliss (1997). The Philosophy of Humanism. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8044-6379-9.

- Mann, Nicholas (1996). "The origins of humanism". In Jill Kraye (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Renaissance Humanism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43624-3.

- Masolo, D.A. (2020). "Humanism in Africa". In Anthony B. Pinn (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Humanism. Pemberton. pp. 1–30. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190921538.013.28. ISBN 978-0-19-092153-8.

- Morain, Lloyd; Morain, Mary (1998). Humanism as the Next Step. Humanist Press. ISBN 978-0-931779-09-1.

- Nederman, Cary (8 September 2020). Edward N. Zalta (ed.). "Civic Humanism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2020 ed.). Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- Nida-Rümelin, Julian (2009). "Philosophical grounds of humanism in economics". In Heiko Spitzeck (ed.). Humanism in Business. Shiban Khan, Ernst von Kimakowitz, Michael Pirson, Wolfgang Amann. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89893-5.

- Norman, Richard (2004). On Humanism. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-70659-2.

- Norman, Richard (2015). "Life Without Meaning?". In A. C. Grayling (ed.). The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Humanism. Andrew Copson. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 325–246. ISBN 978-1-119-97717-9.

- Rohlf, Michael (2020). Edward N. Zalta (ed.). "Immanuel Kant". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Savage, David (2021). "The Development of Non-Religious Pastoral Support in the UK". Religions. 12 (10): 812. doi:10.3390/rel12100812.

- Schröder, Stefan (2020). "Humanism in Europe". In Anthony B. Pinn (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Humanism. Pemberton. pp. 1–24. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190921538.013.32. ISBN 978-0-19-092153-8.

- Schuhmann, Carmen (2015). "Counselling and the Humanist Worldview". In A. C. Grayling (ed.). The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Humanism. Andrew Copson. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 173–193. ISBN 978-1-119-97717-9.

- Shook, John R (2015). "Humanism, Moral Relativism, and Ethical Objectivity". In A. C. Grayling (ed.). The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Humanism. Andrew Copson. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 403–425. ISBN 978-1-119-97717-9.

- Soper, Kate (1986). Humanism and Anti-humanism. Open Court. ISBN 978-0-8126-9017-0.

- Trejo, A.G. Yasmin (2020). "Changing demographics of humanism". In Anthony B. Pinn (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Humanism. Pemberton. pp. 1–25. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190921538.013.15. ISBN 978-0-19-092153-8.

- Walker, Corey D. B. (2020). "Humanism and the Modern Age". In Anthony B. Pinn (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Humanism. Pemberton. pp. 1–18. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190921538.013.17. ISBN 978-0-19-092153-8.

- White, Carol Wyene (2020). "Humanism in the Americas". In Anthony B. Pinn (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Humanism. Pemberton. pp. 1–40. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190921538.013.11. ISBN 978-0-19-092153-8.

- Wilson, Edwin H. (1974). "Humanism's many definitions". In Paul Kurtz (ed.). The Humanist Alternative: Some Definitions of Humanism. Pemberton. ISBN 978-0-87975-013-8.

- Yao, Xinzhong (2000). An Introduction to Confucianism. Cambridge University Press. pp. 15–25. ISBN 978-0-521-64430-3.

Further reading

- Cummings, Dolan (2018). Debating Humanism. Andrews UK Limited. ISBN 978-1-84540-690-5.

- Dacey, Austin (2003). The Case for Humanism An Introduction. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-1393-8.

- Gay, Peter (1964). The Party of Humanity: Essays in the French Enlightenment. Borzoi book. Knopf. ISBN 978-90-10-04434-1. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- Levi, Albert William (1969). Humanism & Politics: Studies in the Relationship of Power and Value in the Western Tradition. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-13900-9. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- Proctor, Robert E. (1998). Defining the Humanities: How Rediscovering a Tradition Can Improve Our Schools : with a Curriculum for Today's Students. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-33421-3.

- Ranisch, Robert (2014). Post- and transhumanism: an introduction. Frankfurt am Main. ISBN 9783631606629.

- Rockmore, Tom (1995). Heidegger and French Philosophy: Humanism, Antihumanism, and Being. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-11181-2.

- Wernick, A. (2001). Auguste Comte and the Religion of Humanity: The Post-theistic Program of French Social Theory. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66272-7. Retrieved 24 October 2022.