Income tax

An income tax is a tax imposed on individuals or entities (taxpayers) in respect of the income or profits earned by them (commonly called taxable income). Income tax generally is computed as the product of a tax rate times the taxable income. Taxation rates may vary by type or characteristics of the taxpayer and the type of income.

| Part of a series on |

| Taxation |

|---|

|

| An aspect of fiscal policy |

|

The tax rate may increase as taxable income increases (referred to as graduated or progressive tax rates). The tax imposed on companies is usually known as corporate tax and is commonly levied at a flat rate. Individual income is often taxed at progressive rates where the tax rate applied to each additional unit of income increases (e.g. the first $10,000 of income taxed at 0%, the next $10,000 taxed at 1%, etc.). Most jurisdictions exempt local charitable organizations from tax. Income from investments may be taxed at different (generally lower) rates than other types of income. Credits of various sorts may be allowed that reduce tax. Some jurisdictions impose the higher of an income tax or a tax on an alternative base or measure of income.

Taxable income of taxpayers resident in the jurisdiction is generally total income less income producing expenses and other deductions. Generally, only net gain from the sale of property, including goods held for sale, is included in income. The income of a corporation's shareholders usually includes distributions of profits from the corporation. Deductions typically include all income-producing or business expenses including an allowance for recovery of costs of business assets. Many jurisdictions allow notional deductions for individuals and may allow deduction of some personal expenses. Most jurisdictions either do not tax income earned outside the jurisdiction or allow a credit for taxes paid to other jurisdictions on such income. Nonresidents are taxed only on certain types of income from sources within the jurisdictions, with few exceptions.

Most jurisdictions require self-assessment of the tax and require payers of some types of income to withhold tax from those payments. Advance payments of tax by taxpayers may be required. Taxpayers not timely paying tax owed are generally subject to significant penalties, which may include jail for individuals. Taxable income of taxpayers resident in the jurisdiction is generally total income less income producing expenses and other deductions. Generally, only net gain from the sale of property, including goods held for sale, is included in income. The income of a corporation's shareholders usually includes distributions of profits from the corporation. Deductions typically include all income-producing or business expenses including an allowance for recovery of costs of business assets. Many jurisdictions allow notional deductions for individuals and may allow deduction of some personal expenses. Most jurisdictions either do not tax income earned outside the jurisdiction or allow a credit for taxes paid to other jurisdictions on such income. Nonresidents are taxed only on certain types of income from sources within the jurisdictions, with few exceptions.

History

The concept of taxing income is a modern innovation and presupposes several things: a money economy, reasonably accurate accounts, a common understanding of receipts, expenses and profits, and an orderly society with reliable records.

For most of the history of civilization, these preconditions did not exist, and taxes were based on other factors. Taxes on wealth, social position, and ownership of the means of production (typically land and slaves) were all common. Practices such as tithing, or an offering of first fruits, existed from ancient times, and can be regarded as a precursor of the income tax, but they lacked precision and certainly were not based on a concept of net increase.

Early examples

The first income tax is generally attributed to Egypt.[1] In the early days of the Roman Republic, public taxes consisted of modest assessments on owned wealth and property. The tax rate under normal circumstances was 1% and sometimes would climb as high as 3% in situations such as war. These modest taxes were levied against land, homes and other real estate, slaves, animals, personal items and monetary wealth. The more a person had in property, the more tax they paid. Taxes were collected from individuals.[2]

In the year 10 AD, Emperor Wang Mang of the Xin Dynasty instituted an unprecedented income tax, at the rate of 10 percent of profits, for professionals and skilled labor. He was overthrown 13 years later in 23 AD and earlier policies were restored during the reestablished Han Dynasty which followed.

One of the first recorded taxes on income was the Saladin tithe introduced by Henry II in 1188 to raise money for the Third Crusade.[3] The tithe demanded that each layperson in England and Wales be taxed one tenth of their personal income and moveable property.[4]

In 1641, Portugal introduced a personal income tax called the décima.[5]

United Kingdom

The inception date of the modern income tax is typically accepted as 1799,[6] at the suggestion of Henry Beeke, the future Dean of Bristol.[7] This income tax was introduced into Great Britain by Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger in his budget of December 1798, to pay for weapons and equipment for the French Revolutionary War. Pitt's new graduated (progressive) income tax began at a levy of 2 old pence in the pound (1⁄120) on incomes over £60 (equivalent to £5,500 in 2019),[8] and increased up to a maximum of 2 shillings in the pound (10%) on incomes of over £200. Pitt hoped that the new income tax would raise £10 million a year, but actual receipts for 1799 totalled only a little over £6 million.[9]

Pitt's income tax was levied from 1799 to 1802, when it was abolished by Henry Addington during the Peace of Amiens. Addington had taken over as prime minister in 1801, after Pitt's resignation over Catholic Emancipation. The income tax was reintroduced by Addington in 1803 when hostilities with France recommenced, but it was again abolished in 1816, one year after the Battle of Waterloo. Opponents of the tax, who thought it should only be used to finance wars, wanted all records of the tax destroyed along with its repeal. Records were publicly burned by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, but copies were retained in the basement of the tax court.[10]

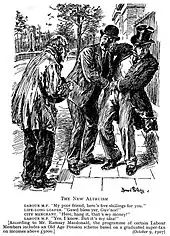

In the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, income tax was reintroduced by Sir Robert Peel by the Income Tax Act 1842. Peel, as a Conservative, had opposed income tax in the 1841 general election, but a growing budget deficit required a new source of funds. The new income tax, based on Addington's model, was imposed on incomes above £150 (equivalent to £16,224 in 2019).[11] Although this measure was initially intended to be temporary, it soon became a fixture of the British taxation system.

A committee was formed in 1851 under Joseph Hume to investigate the matter, but failed to reach a clear recommendation. Despite the vociferous objection, William Gladstone, Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1852, kept the progressive income tax, and extended it to cover the costs of the Crimean War. By the 1860s, the progressive tax had become a grudgingly accepted element of the United Kingdom fiscal system.[12]

United States

The US federal government imposed the first personal income tax on August 5, 1861, to help pay for its war effort in the American Civil War (3% of all incomes over US$800) (equivalent to $18,600 in 2020).[13][14][15] This tax was repealed and replaced by another income tax in 1862.[16][17] It was only in 1894 that the first peacetime income tax was passed through the Wilson-Gorman tariff. The rate was 2% on income over $4000 (equivalent to $110,000 in 2020), which meant fewer than 10% of households would pay any. The purpose of the income tax was to make up for revenue that would be lost by tariff reductions.[18] The US Supreme Court ruled the income tax unconstitutional, the 10th amendment forbidding any powers not expressed in the US Constitution, and there being no power to impose any other than a direct tax by apportionment.

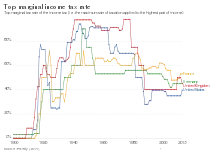

In 1913, the Sixteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution made the income tax a permanent fixture in the U.S. tax system. In fiscal year 1918, annual internal revenue collections for the first time passed the billion-dollar mark, rising to $5.4 billion by 1920.[19] The amount of income collected via income tax has varied dramatically, from 1% in the early days of US income tax to taxation rates of over 90% during World War II.

Timeline of introduction of income tax by country

- 1799–1802:

United Kingdom

United Kingdom - 1803–1816:

United Kingdom

United Kingdom - 1840:

Switzerland[20]

Switzerland[20] - 1842:

United Kingdom

United Kingdom - 1860:

India[21][lower-alpha 1]

India[21][lower-alpha 1] - 1861–1872:

United States

United States - 1872:

France[22]

France[22] - 1887:

Japan[23]

Japan[23] - 1891:

New Zealand[24]

New Zealand[24] - 1894–95:

United States

United States - 1900:

Spain[25]

Spain[25] - 1903:

Denmark,[26]

Denmark,[26]  Sweden

Sweden - 1908:

Indonesia[27]

Indonesia[27] - 1911:

Norway[28]

Norway[28] - 1913:

United States

United States - 1916:

.svg.png.webp) Australia,[29]

Australia,[29] .svg.png.webp) Russia[30]

Russia[30] - 1918:

.svg.png.webp) Canada

Canada - 1920:

Finland,

Finland,  Poland[31]

Poland[31] - 1921:

Iceland

Iceland - 1924:

Brazil,[32]

Brazil,[32]  Mexico[33]

Mexico[33] - 1932:

.svg.png.webp) Bolivia,[34]

Bolivia,[34]  Argentina[35]

Argentina[35] - 1934:

Peru[36]

Peru[36] - 1937:

China[37]

China[37] - 1942:

Venezuela[38]

Venezuela[38] - 2007:

Uruguay[39]

Uruguay[39]

Common principles

While tax rules vary widely, there are certain basic principles common to most income tax systems. Tax systems in Canada, China, Germany, Singapore, the United Kingdom, and the United States, among others, follow most of the principles outlined below. Some tax systems, such as India, may have significant differences from the principles outlined below. Most references below are examples; see specific articles by jurisdiction (e.g., Income tax in Australia).

Taxpayers and rates

Individuals are often taxed at different rates than corporations. Individuals include only human beings. Tax systems in countries other than the USA treat an entity as a corporation only if it is legally organized as a corporation. Estates and trusts are usually subject to special tax provisions. Other taxable entities are generally treated as partnerships. In the US, many kinds of entities may elect to be treated as a corporation or a partnership. Partners of partnerships are treated as having income, deductions, and credits equal to their shares of such partnership items.

Separate taxes are assessed against each taxpayer meeting certain minimum criteria. Many systems allow married individuals to request joint assessment. Many systems allow controlled groups of locally organized corporations to be jointly assessed.

Tax rates vary widely. Some systems impose higher rates on higher amounts of income. Example: Elbonia taxes income below E.10,000 at 20% and other income at 30%. Joe has E.15,000 of income. His tax is E.3,500. Tax rates schedules may vary for individuals based on marital status.[lower-alpha 2] In India on the other hand there is a slab rate system, where for income below INR 2.5 lakhs per annum the tax is zero percent, for those with their income in the slab rate of INR 2,50,001 to INR 5,00,000 the tax rate is 5%. In this way the rate goes up with each slab, reaching to 30% tax rate for those with income above INR 15,00,000.[40]

Residents and non-residents

Residents are generally taxed differently from non-residents. Few jurisdictions tax non-residents other than on specific types of income earned within the jurisdiction. See, e.g., the discussion of taxation by the United States of foreign persons. Residents, however, are generally subject to income tax on all worldwide income.[lower-alpha 3] A handful of jurisdictions (notably Singapore and Hong Kong) tax residents only on income earned in or remitted to the jurisdiction. There may arise a situation where the tax payer has to pay tax in one jurisdiction he or she is tax resident and also pay tax to other country where he or she is non-resident. This creates the situation of Double taxation which needs assessment of Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement entered by the jurisdictions where the tax payer is assessed as resident and non-resident for the same transaction.

Residence is often defined for individuals as presence in the jurisdiction for more than 183 days. Most jurisdictions base residence of entities on either place of organization or place of management and control.

Defining income

Most systems define income subject to tax broadly for residents, but tax nonresidents only on specific types of income. What is included in income for individuals may differ from what is included for entities. The timing of recognizing income may differ by type of taxpayer or type of income.

Income generally includes most types of receipts that enrich the taxpayer, including compensation for services, gain from sale of goods or other property, interest, dividends, rents, royalties, annuities, pensions, and all manner of other items.[lower-alpha 4] Many systems exclude from income part or all of superannuation or other national retirement plan payments. Most tax systems exclude from income health care benefits provided by employers or under national insurance systems.

Deductions allowed

Nearly all income tax systems permit residents to reduce gross income by business and some other types of deductions. By contrast, nonresidents are generally subject to income tax on the gross amount of income of most types plus the net business income earned within the jurisdiction.

Expenses incurred in a trading, business, rental, or other income producing activity are generally deductible, though there may be limitations on some types of expenses or activities. Business expenses include all manner of costs for the benefit of the activity. An allowance (as a capital allowance or depreciation deduction) is nearly always allowed for recovery of costs of assets used in the activity. Rules on capital allowances vary widely, and often permit recovery of costs more quickly than ratably over the life of the asset.

Most systems allow individuals some sort of notional deductions or an amount subject to zero tax. In addition, many systems allow deduction of some types of personal expenses, such as home mortgage interest or medical expenses.

Business profits

Only net income from business activities, whether conducted by individuals or entities is taxable, with few exceptions. Many countries require business enterprises to prepare financial statements[41] which must be audited. Tax systems in those countries often define taxable income as income per those financial statements with few, if any, adjustments. A few jurisdictions compute net income as a fixed percentage of gross revenues for some types of businesses, particularly branches of nonresidents.

Credits

Nearly all systems permit residents a credit for income taxes paid to other jurisdictions of the same sort. Thus, a credit is allowed at the national level for income taxes paid to other countries. Many income tax systems permit other credits of various sorts, and such credits are often unique to the jurisdiction.

Alternative taxes

Some jurisdictions, particularly the United States and many of its states and Switzerland, impose the higher of regular income tax or an alternative tax. Switzerland and U.S. states generally impose such tax only on corporations and base it on capital or a similar measure.

Administration

Income tax is generally collected in one of two ways: through withholding of tax at source and/or through payments directly by taxpayers. Nearly all jurisdictions require those paying employees or nonresidents to withhold income tax from such payments. The amount to be withheld is a fixed percentage where the tax itself is at a fixed rate. Alternatively, the amount to be withheld may be determined by the tax administration of the country or by the payer using formulas provided by the tax administration. Payees are generally required to provide to the payer or the government the information needed to make the determinations. Withholding for employees is often referred to as "pay as you earn" (PAYE) or "pay as you go."

Income taxes of workers are often collected by employers under a withholding or pay-as-you-earn tax system. Such collections are not necessarily final amounts of tax, as the worker may be required to aggregate wage income with other income and/or deductions to determine actual tax. Calculation of the tax to be withheld may be done by the government or by employers based on withholding allowances or formulas.

Nearly all systems require those whose proper tax is not fully settled through withholding to self-assess tax and make payments prior to or with final determination of the tax. Self-assessment means the taxpayer must make a computation of tax and submit it to the government. Some countries provide a pre-computed estimate to taxpayers, which the taxpayer can correct as necessary.

The proportion of people who pay their income taxes in full, on time, and voluntarily (that is, without being fined or ordered to pay more by the government) is called the voluntary compliance rate.[42] The voluntary compliance rate is higher in the US than in countries like Germany or Italy.[42] In countries with a sizeable black market, the voluntary compliance rate is very low and may be impossible to properly calculate.[42]

State, provincial, and local

Income taxes are separately imposed by sub-national jurisdictions in several countries with federal systems. These include Canada, Germany, Switzerland, and the United States, where provinces, cantons, or states impose separate taxes. In a few countries, cities also impose income taxes. The system may be integrated (as in Germany) with taxes collected at the federal level. In Quebec and the United States, federal and state systems are independently administered and have differences in determination of taxable income.

Wage-based taxes

Retirement oriented taxes, such as Social Security or national insurance, also are a type of income tax, though not generally referred to as such. In the US, these taxes generally are imposed at a fixed rate on wages or self-employment earnings up to a maximum amount per year. The tax may be imposed on the employer, the employee, or both, at the same or different rates.

Some jurisdictions also impose a tax collected from employers, to fund unemployment insurance, health care, or similar government outlays.

Economic and policy aspects

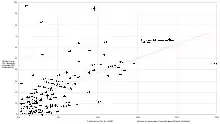

Multiple conflicting theories have been proposed regarding the economic impact of income taxes.[lower-alpha 5] Income taxes are widely viewed as a progressive tax (the incidence of tax increases as income increases).

Some studies have suggested that an income tax doesn't have much effect on the numbers of hours worked.[43]

Criticisms

Tax avoidance strategies and loopholes tend to emerge within income tax codes. They get created when taxpayers find legal methods to avoid paying taxes. Lawmakers then attempt to close the loopholes with additional legislation. That leads to a vicious cycle of ever more complex avoidance strategies and legislation.[44] The vicious cycle tends to benefit large corporations and wealthy individuals that can afford the professional fees that come with ever more sophisticated tax planning,[45] thus challenging the notion that even a marginal income tax system can be properly called progressive.

The higher costs to labour and capital imposed by income tax causes dead weight loss in an economy, being the loss of economic activity from people deciding not to invest capital or use time productively because of the burden that tax would impose on those activities. There is also a loss from individuals and professional advisors devoting time to tax-avoiding behaviour instead of economically productive activities.[46]

Criticism within Entrepreneurship

Income

Whether this is the earnings a firm receives, or an individual receives, it is subject to tax in many countries in the world. This tax subjection sometimes hinders the process of venturing into entrepreneurship. While this is not surprising since one of the “unconstituted constituted” rules of thumb for entrepreneurship is that there needs to be self-financing especially at the early stages of the new business. This tax burden on the income of a potential entrepreneur contributes to the lack of drive since there is a self-dependency with financing the business idea. In other cases, it can lead to withdrawal of pursuing that idea since someone else might have been able to overtake them and execute their idea in the project as time passes by Haufler et al. (2014, 28). Another way tax affects entrepreneurial entry through income rises from the fact that there is no guarantee of how well the business does. So, if the entrepreneurs are being taxed both for their business and their personal pay off from the business, they might end up making less or not enough to even re-invest in the business.

Additionally, if entrepreneurs are able to jump through the scales of starting and running a business the next phase is typically employing people to work for their business. To be able to employ people, they have to be able to afford to pay them and this is normally hard for entrepreneurs especially at the early stages of the business. Djankov et al. (2010) explained that when the income tax is imposed on businesses it discourages entrepreneurs from hiring workers. And this cycle is detrimental to the economy of that region because the reason they might have encouraged innovative entrepreneurs to locate might have been to create jobs in their area which interprets to economic growth. But if they are unable to create jobs and hire workers to join the business, it ultimately counters the initial goal that was meant to be attained by the policymakers of the area.

Additionally, Campodonico, Bonfatti and Pisan (2016) suggest that entrepreneurs should be discouraged from incurring debt by borrowing money. Ironically this aforementioned seems to be a source of financing most start-up entrepreneurs go through. Most entrepreneurs turn to debt financing since it is largely available, attainable, and highly recommended by their counterparts Henrekson and Sanandaji (2011, 10). When entrepreneurs are forced to incur debt financing it might be sustainable for a while but on a larger scale, if more entrepreneurs take this up, it leads to increased systemic risk and makes the economy more precarious to crash Henrekson et al. (2010, 9). This logically makes sense because it is something that has occurred before in the United States, i.e., the financial crisis in the United States.

Apart from the income tax affecting the number of entrepreneurs entering the market, Hedlund (2019) argues that it also affects the quality of ideas of the entrepreneurs entering the market. Hedlund expressed how there are entrepreneurs who partake in innovation to contribute to the social impact rather than just for monetary gain. Therefore, when there are suppressants in the entry policies specifically tax policies it causes a 9.4% - 12.5% reduction in the quality of innovation.

Tax credits are part of the incentives that business owners get from the government as a form of subsidy to help curb the costs associated with starting and running a business. Tax credits are simply the upgrade from getting a tax deduction or the better deal given in place of a tax deduction. They are typically granted to businesses rather than individuals except in special situations. A general example of how tax credits work is, if I received a tax credit of $1000 on my $5000 salary, I would not be taxed anymore, thereby saving $1000. While if I earned $5000 and received a tax deduction of $1000, my net income becomes $4000 and I am still taxed on that $4000 compared to $5000 which would have been more expensive. The explanation above describes how beneficial this tax credit could be if it is granted to entrepreneurs. The possible outcomes will benefit both the entrepreneurs in attaining their goals, as well as the policyholders in increasing economic growth. Evidence from Fazio et al. (2020) contributes to this conclusion by expressing that these tax credits not only positively influence the innovators at the beginning of their businesses but in the long run too.

Furthermore, there is an argument that when tax credits are given to bigger firms, there is an in-balance in the business ecosystem, which often leads to a crowding-out effect rather than a spillover effect Fazio et al. (2020). Some might dispute the argument by suggesting that when tax credits are granted to firms in general, there should be a higher amount given to smaller start-up firms compared to the bigger or incumbent firms to level the playing field.

These few reasons explained above are why taxes on income should be imminently reduced or completely dissolved to encourage people to participate in entrepreneurial activity within regions. Evidence from the research done has shown the effectiveness of reducing income taxes and how it played a role in the entrepreneurial growth of the region and on a larger scale, how it helped with the economic growth of that region. The persistence of high-income tax both for the entrepreneur prior to starting a business and the workers employed after the business starts seems to be a major issue to the hindrance of entrepreneurial activity in a location. A possible solution to this problem will be to cut the marginal taxes on the income as suggested by Carrol et al. (2000). Although this is a potential solution it should be carried out with a grain of salt to ensure that there is an even playing field for both entrepreneurs and incumbent innovative businesses.

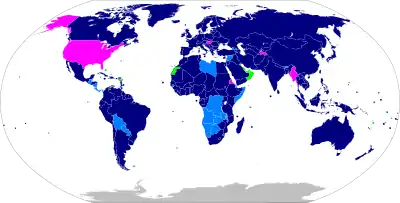

Around the world

Income taxes are used in most countries around the world. The tax systems vary greatly and can be progressive, proportional, or regressive, depending on the type of tax. Comparison of tax rates around the world is a difficult and somewhat subjective enterprise. Tax laws in most countries are extremely complex, and tax burden falls differently on different groups in each country and sub-national unit. Of course, services provided by governments in return for taxation also vary, making comparisons all the more difficult.

Countries that tax income generally use one of two systems: territorial or residential. In the territorial system, only local income – income from a source inside the country – is taxed. In the residential system, residents of the country are taxed on their worldwide (local and foreign) income, while nonresidents are taxed only on their local income. In addition, a very small number of countries, notably the United States, also tax their nonresident citizens on worldwide income.

Countries with a residential system of taxation usually allow deductions or credits for the tax that residents already pay to other countries on their foreign income. Many countries also sign tax treaties with each other to eliminate or reduce double taxation.

Countries do not necessarily use the same system of taxation for individuals and corporations. For example, France uses a residential system for individuals but a territorial system for corporations,[47] while Singapore does the opposite,[48] and Brunei taxes corporate but not personal income.[49][50]

Transparency and public disclosure

Public disclosure of personal income tax filings occurs in Finland, Norway and Sweden (as of the late-2000s and early 2010s).[51][52] In Sweden this information have been published in the annual directory Taxeringskalendern since 1905.

See also

- Category:Income taxes

- Smart contract: can be used in employment contracts and allows some degree of automation

- Wealth tax

Notes

- Income tax in India

- See, e.g., rates under the Germany and United States systems.

- The German system is typical in this regard.

- See, e.g., gross income in the United States.

- See, e.g., references in Tax#Economic effects, Economics#Macroeconomics, Fiscal policy

References

- Breasted, James Henry (1906). Ancient Records of Egypt. Vol. II: The Eighteenth Dynasty. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. paragraph 719-742.

- "Roman Taxes". UNRV.com. Retrieved April 12, 2014.

- "Saladin Tithe". Online Medieval Sources Bibliography.

- Harris, Peter (2006). Income tax in common law jurisdictions: from the origins to 1820, Volume 1. p. 34. ISBN 9780521870832.

- Freire Costa, Leonor; Lains, Pedro; Münch Miranda, Susana (2016). An Economic History of Portugal, 1143-2010. p. 8. ISBN 9781107035546.

- Harris, Peter (2006). Income tax in common law jurisdictions: from the origins to 1820, Volume 1. p. 1. ISBN 9780521870832.

- Urban, Sylvanus (1837). The Gentleman's Magazine. New Series. Vol. VII (162). pp. 546–47.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- "A tax to beat Napoleon". HM Revenue & Customs. Archived from the original on July 24, 2010. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- Adams, Charles (1998). Those Dirty Rotten Taxes: the tax revolts that built America. New York: The Free Press. ISBN 0-684-84394-3.

- United Kingdom Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth "consistent series" supplied in Thomas, Ryland; Williamson, Samuel H. (2018). "What Was the U.K. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- Bank, Steven A. (2011). Anglo-American Corporate Taxation: Tracing the Common Roots of Divergent Approaches. Cambridge University Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 9781139502597.

- Revenue Act of 1861, sec. 49, ch. 45, 12 Stat. 292, 309 (Aug. 5, 1861).

- Pollack, Sheldon D. (2014). "The First National Income Tax, 1861–1872". The Tax Lawyer. 67 (2): 311–330. JSTOR 24247751.

- Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2022). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved February 12, 2022. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth series.

- Sections 49, 51, and part of 50 repealed by Revenue Act of 1862, sec. 89, ch. 119, 12 Stat. 432, 473 (July 1, 1862); income taxes imposed under Revenue Act of 1862, section 86 (pertaining to salaries of officers, or payments to "persons in the civil, military, naval, or other employment or service of the United States ...") and section 90 (pertaining to "the annual gains, profits, or income of every person residing in the United States, whether derived from any kind of property, rents, interest, dividends, salaries, or from any profession, trade, employment or vocation carried on in the United States or elsewhere, or from any other source whatever ...").

- "THIRTY-EIGHTH CONGRESS. SESS.. I. C. 173. 1864" (PDF). Library of Congress. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-11-13. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- Dunbar, Charles F. (1894). "The New Income Tax". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 9 (1): 26–46. doi:10.2307/1883633. JSTOR 1883633.

- Young, Adam (September 7, 2004). "The Origin of the Income Tax". Ludwig von Mises Institute. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- "An outline of Swiss Tax System" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-05-06. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- Pandey, T. N. (February 13, 2000). "The evolution of income-tax". The Hindu Business Line.

- "Top Incomes in France in the Twentieth Century Inequality and Redistribution, 1901–1998 by Thomas Piketty". EuropeNow.

- Shiomi, Saburo (1935). "The Development of the Income Tax in Japan". Kyoto University Economic Review. 10 (1): 54–84. JSTOR 43216791.

- Vosslamber, Rob (2011). "Taxation for New Zealand's future: The introduction of New Zealand's progressive income tax in 1891". Accounting History. 17 (1): 105–122. doi:10.1177/1032373211424581. S2CID 154949776.

- Jiménez-Valladolid de L´Hotellerie-Fallois, Domingo Alberto; Vega Borrego, Félix (2013). "Corporate income tax subjects: Spain" (PDF). Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness of Spain. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 12, 2019. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Tax Policy Reforms in Denmark (PDF) (Report).

- "Who pulled the strings? A comparative study of Indonesian and Vietnamese tax reform" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-05-06. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- Zimmer, Frederik (2003). "The Development of the Concept of Income in Nordic Tax Law" (PDF). In Wahlgren, Peter (ed.). Scandinavian Studies in Law. Vol. 44: Tax Law. Stockholm: The Stockholm University Law Faculty. pp. 393–410.

- Stewart, Miranda (June 6, 2016). "Income Tax at 100 Years: A Little History". Tax and Transfer Policy Institute. Australian National University.

- Bowman, Linda (1993). "Russia's First Income Taxes: The Effects of Modernized Taxes on Commerce and Industry, 1885-1914". Slavic Review. 52 (2): 256–282. doi:10.2307/2499922. JSTOR 2499922. S2CID 156258835.

- Ustawa z dnia 16 lipca 1920 r. o państwowym podatku dochodowym i podatku majątkowym [Act on State Income Tax and Property Tax], Dz. U. z 1920 r. Nr 82, poz. 550 (1920-07-16)

- Rodriguez, Diogo (October 18, 2018). "Income tax in Brazil: past, present, and future". The Brazilian Report.

- Albertus, Michael (2015). Autocracy and Redistribution: the politics of land reform. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-107-10655-0.

- Contreras, Manuel E (1993). The Bolivian Tin Mining Industry in the First Half of the Twentieth Century (PDF). Institute of Latin American Studies Research Papers. Vol. 32. London: Institute of Latin American Studies. ISBN 0-901145-85-8.

- "Institutions and Factor Endowments: Income Taxation in Argentina and Australia" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-05-06. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- Basombrio Porras, Carlos. "Collection Agencies and Systems in Peru" (PDF): 129–132.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Pang Tim Tim, Terence (2002). "Kong Xiangxi, Chauncey". In Pak-Wah Leung, Edwin (ed.). Political Leaders of Modern China: A Biographical Dictionary. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 77. ISBN 0-313-30216-2.

- Moreno, María Antonia; Maita Bolívar, Miriam Adriana (2014). "Tax elasticity in Venezuela: A dynamic cointegration approach" (PDF): 1–49.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "6 años de IRPF, evaluación de la imposición a la renta personal" [Six years of IRPF, evaluation of the personal income tax] (presentation) (in Spanish). Jornadas Tributarias. October 30, 2013.

- "Income Tax Slabs - Economic Times". The Economic Times.

- See, e.g., UK requirements

- Chun, Rene (March 10, 2019). "Why Americans Don't Cheat on Their Taxes". The Atlantic. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- Killingsworth 1983 and Pencavel 1986

- "Why are taxes so complicated?". Tax Policy Center. May 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2013.

- Drucker, Jesse (April 18, 2012). "How to Pay No Taxes: 10 Strategies Used by the Rich". Bloomberg. Retrieved August 19, 2013.

- Kagan, Julia (March 15, 2022). "Deadweight Loss Of Taxation". Investopedia. Retrieved August 19, 2013.

- "International tax - France Highlights 2012" (PDF). Deloitte. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 25, 2012.

- "International tax - Singapore Highlights 2012" (PDF). Deloitte. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 3, 2013.

- "International tax – Brunei Darussalam Highlights 2012" (PDF). Deloitte. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 25, 2012.

- See. Lincoln IV, Charles Edward Andrew (2017). "Is Incorporation Really Better than Central Management and Control for Testing Corporate Residency? An Answer to Corporate Tax Evasion and Inversion". Ohio Northern University Law Review. 43: 359–372. SSRN 2918694.

- Bernasek, Anna (February 13, 2010). "Should Tax Bills Be Public Information?". The New York Times. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- Stinson, Jeffrey (June 18, 2008). "How much do you make? It'd be no secret in Scandinavia". USA Today. London.

External links

- What Is Income Tax Return (ITR) In India

- History of the Income Tax in the United States — Infoplease.com

- Greece - State collected less than half of revenues due last year

- THE EFFECT OF PUBLIC DISCLOSURE ON REPORTED TAXABLE INCOME: EVIDENCE FROM INDIVIDUALS AND CORPORATIONS IN JAPAN

- European Commission: Transparency and the fight against tax avoidance Archived 2015-06-28 at the Wayback Machine