Illyrians

The Illyrians (Ancient Greek: Ἰλλυριοί, Illyrioi; Latin: Illyrii) were a group of Indo-European-speaking peoples who inhabited the western Balkan Peninsula in ancient times. They constituted one of the three main Paleo-Balkan populations, along with the Thracians and Greeks.

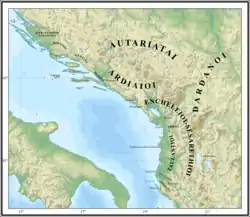

The territory the Illyrians inhabited came to be known as Illyria to later Greek and Roman authors, who identified a territory that corresponds to most of Albania, Montenegro, Kosovo,[lower-alpha 1] much of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, western and central Serbia and some parts of Slovenia between the Adriatic Sea in the west, the Drava river in the north, the Morava river in the east and in the south the Aous (modern Vjosa) river or possibly the Ceraunian Mountains.[1][2] The first account of Illyrian peoples dates back to the 6th century BC, in the works of the ancient Greek writer Hecataeus of Miletus.

The name "Illyrians", as applied by the ancient Greeks to their northern neighbors, may have referred to a broad, ill-defined group of peoples. The Illyrian tribes never collectively identified as "Illyrians", and it is unlikely that they used any collective nomenclature at all.[3] Illyrians seems to be the name of a specific Illyrian tribe who were among the first to encounter the ancient Greeks during the Bronze Age.[4] The Greeks later applied this term Illyrians, pars pro toto, to all people with similar language and customs.[5]

In archaeological, historical and linguistic studies, research about the Illyrians, from the late 19th to the 21st century, has moved from Pan-Illyrian theories, which identified as Illyrian even groups north of the Balkans to more well-defined groupings based on Illyrian onomastics and material anthropology since the 1960s as newer inscriptions were found and sites excavated. There are two principal Illyrian onomastic areas: the southern and the Dalmatian-Pannonian, with the area of the Dardani as a region of overlapping between the two. A third area, to the north of them – which in ancient literature was usually identified as part of Illyria – has been connected more to the Venetic language than to Illyrian. Illyric settlement in Italy was and still is attributed to a few ancient tribes which are thought to have migrated along the Adriatic shorelines to the Italian peninsula from the geographic "Illyria": the Dauni, the Peuceti and Messapi (collectively known as Iapyges).

The term "Illyrians" last appears in the historical record in the 7th century, referring to a Byzantine garrison operating within the former Roman province of Illyricum.[6]

Names and terminology

The terms 'Illyrians', 'Illyria' and 'Illyricum' have been used throughout history for ethnic and geographic contextualizations that have changed over time. Re-contextualizations of these terms often confused ancient writers and modern scholars. Notable scholarly efforts have been dedicated to try to analyze and explain these changes.[7]

The first known mention of Illyrians occurred in the late 6th and the early 5th century BC in fragments of Hecataeus of Miletus, the author of Γενεαλογίαι (Genealogies) and of Περίοδος Γῆς or Περιήγησις (Description of the Earth or Periegesis), where the Illyrians are described as a barbarian people.[8][9][note 1] In the Macedonian history during the 6th and 5th century B.C., the term 'Illyrian' had a political meaning that was quite definite, denoting a kingdom established on the north-western borders of Upper Macedonia.[12] From the 5th century B.C. onwards, the term 'Illyrian' was already applied to a large ethnic group whose territory extended deep into the Balkan mainland.[13][note 2] Ancient Greeks clearly considered the Illyrians as a completely distinct ethnos from both the Thracians (Θρᾷκες) and the Macedonians (Μακεδόνες).[18]

Most scholars hold that the territory originally designated as 'Illyrian' was roughly located in the region of the south-eastern Adriatic (modern Albania and Montenegro) and its hinterland, then was later extended to the whole Roman Illyricum province, which stretched from the eastern Adriatic to the Danube.[7] After the Illyrians had come to be widely known to the Greeks due to their proximity, this ethnic designation was broadened to include other peoples who, for some reason, were considered by ancient writers to be related with those peoples originally designated as Illyrians (Ἰλλυριοί, Illyrioi).[13][19] The original designation may have occurred during the Bronze Age, when Greek-speaking tribes may have been neighbours of the southernmost Illyrian tribe of that time that dwelled in the Zeta plain in Montenegro or in the Mat valley in Albania, being subsequently applied as a general term to people of the same language and manners.[4][20] It has been also inferred that if Greek populations had their first contact with Illyrian tribes when the latter dwelt around Shkodër, then an Illyrian expansion southwards took place during the early first millennium BC, before the later reaching Aous.[21] The label Illyrians was first used by outsiders, in particular Ancient Greeks, at the beginning of the 8th century BC. When the Greeks began to frequent the eastern Adriatic coast with the colonization of Corcyra, they started to have some knowledge and perceptions of the indigenous peoples of western Balkans.[3]

The Illyrian tribes evidently never collectively identified themselves as Illyrians and it is unlikely that they used any collective nomenclature at all.[3] Most modern scholars are certain that all the peoples of western Balkans that were collectively labeled as 'Illyrians' were not a culturally or linguistically homogeneous entity.[22][23] For instance, some tribes like the Bryges would not have been identified as Illyrian.[24] What criteria were initially used to define this group of peoples or how and why the term 'Illyrians' began to be used to describe the indigenous population of western Balkans cannot be said with certainty.[25] Scholarly debates have been waged to find an answer to the question whether the term 'Illyrians' (Ἰλλυριοί) derived from some eponymous tribe, or whether it has been applied to designate the indigenous population as a general term for some other specific reason.[26]

Illyrii proprie dicti

Ancient Roman writers Pliny the Elder and Pomponius Mela used the term Illyrii proprie dicti ('properly called Illyrians') to designate a people that was located in the coast of modern Albania and Montenegro.[26] Many modern scholars view the 'properly called Illyrians' as a trace of the Illyrian kingdom known in the sources from the 4th century BC until 167 BC, which was ruled in Roman times by the Ardiaei and Labeatae when it was centered in the Bay of Kotor and Lake Skadar. According to other modern scholars, the term Illyrii may have originally referred only to a small ethnos in the area between Epidaurum and Lissus, and Pliny and Mela may have followed a literary tradition that dates back as early as Hecataeus of Miletus.[8][26] Placed in central Albania, the Illyrii proprie dicti also might have been Rome's first contact with Illyrian peoples. In that case, it did not indicate an original area from which the Illyrians expanded.[27] The area of the Illyrii proprie dicti is largely included in the southern Illyrian onomastic province in modern linguistics.[28]

Origins

Archaeology and archaeogenetics

The Illyrians emerged from the fusion of PIE-descended Yamnaya-related population movements ca. 2500 BCE in the Balkans with the pre-existing Balkan Neolithic population, initially forming "Proto-Illyrian" Bronze Age cultures in the Balkans.[29][30][31] The proto-Illyrians during the course of their settlement towards the Adriatic coast merged with such populations of a pre-Illyrian substratum – like Enchelei might have been –, leading to the formation of the historical Illyrians who were attested in later times. It has been suggested that the myth of Cadmus and Harmonia may be a reflection in mythology of that historical era.[32]

Older Pan-Illyrian theories which emerged in the 1920s placed the proto-Illyrians as the original inhabitants of a very large area which reached central Europe. These theories, which have been dismissed, were used in the politics of the era and its racialist notions of Nordicism and Aryanism.[22] The main fact which these theories tried to address was the existence of traces of Illyrian toponymy in parts of Europe beyond the western Balkans, an issue whose origins are still unclear.[33] The specific theories have found little archaeological corroboration, as no convincing evidence for significant migratory movements from the Urnfield-Lusatian culture into the west Balkans has ever been found.[34][35][36]

Mathieson et al. 2018 archaeogenetic study included three samples from Dalmatia: two Early & Middle Bronze Age (1631-1521/1618-1513 calBCE) samples from Veliki Vanik (near Vrgorac) and one Iron Age (805-761 calBCE) sample from Jazinka Cave in Krka National Park. According to ADMIXTURE analysis they had approximately 60% Early European Farmers, 33% Western Steppe Herders and 7% Western Hunter-Gatherer-related ancestry. The male individual from Veliki Vanik carried the Y-DNA haplogroup J2b2a1-L283 while his and two female individuals mtDNA haplogroup were I1a1, W3a1 and HV0e.[37] Freilich et al. 2021 identify the Veliki Vanik samples as related to the Cetina culture (EBA-MBA western Balkans). They carry similar ancestry to a Copper Age sample from the site of Beli Manastir-Popova Zemlja (late Vučedol culture), eastern Croatia. The same autosomal profile persists in the Iron Age sample from Jazinka cave.[38]

Patterson et al. 2022 study examined 18 samples from the Middle Bronze Age up to Early Iron Age Croatia, which was part of Illyria. Out of the nine Y-DNA samples retrieved, which coincide with the historical territory where Illyrians lived (including tested Iapydes and Liburni sites), almost all belonged to the patrilineal line J2b2a1-L283 (>J-PH1602 > J-Y86930 and >J-Z1297 subclades) with the exception of one R1b-L2. The mtDNA haplogroups fell under various subclades of H, H1, H3b, H5, J1c2, J1c3, T2a1a, T2b, T2b23, U5a1g, U8b1b1, HV0e. In a three-way admixture model, they approximately had 49-59% EEF, 35-46% Steppe and 2-10% WHG-related ancestry.[39] In Lazaridis et al. (2022) key parts of the territory of historical territory of Illyria were tested. In 18 samples from the Cetina culture, all males except for one (R-L51 > Z2118) carried Y-DNA haplogroup J-L283. Many of them could be further identified as J-L283 > Z597 (> J-Y15058 > J-Z38240 > J-PH1602). The majority of individuals carried mtDNA haplogroups J1c1 and H6a1a. The related Posušje culture yielded the same Y-DNA haplogroup (J-L283 > J-Z38240). The same J-L283 population appears in the MBA-IA Velim Kosa tumuli of Liburni in Croatia (J-PH1602), and similar in LBA-IA Velika Gruda tumuli in Montenegro (J-Z2507 > J-Z1297 > J-Y21878). The oldest J-L283 (> J-Z597) sample in the study was found in MBA Shkrel, northern Albania as early as the 19th century BCE. In northern Albania, IA Çinamak, half of them men carried J-L283 (> J-Z622, J-Y21878) and the other half R-M269 (R-L51 x1, R-CTS1450 x1). The oldest sample in Çinamak dates to the first era of post-Yamnaya movements (EBA) and carries R-M269.[40] Autosomally, Croatian Bronze Age samples from various sites, from Cetina valley and Bezdanjača Cave were "extremely similar in their ancestral makeup",[41] while from Montenegro's Velika Gruda mainly had an admixture of "Anatolian Neolithic (~50%), Eastern European hunter-gatherer (~12%), and Balkan hunter-gatherer ancestry (~18%)".[42]

Aneli et al. 2022 found that the Early Iron Age Illyrians made "part of the same Mediterranean continuum" with the "autochthonous [...] Roman Republicans" and had high affinity with Daunians, part of Iapygians people in Southeast of Italian Peninsula, whose male samples also belonged to J-M241 > J-L283 among others.[43] It was also found in Bronze Age Nuragic civilization of Sardinia,[44][45] in two Etruscans and two 7-8th century men from Venosa and one Imperial Roman in Italy.[46][47][48][45][49] The presence of the subclade in Sardinia and other cultures is probably due to contact with people of Bronze Age Western Balkan origin.[50] The oldest Balkan J-L283 sample was found in Early Bronze Age (ca. 1950 BCE) site of Mokrin in Serbia.[51]

In ancient Greek and Roman literature

Different versions of the genealogy of the Illyrians, their tribes and their eponymous ancestor, Illyrius, existed in the ancient world both in fictional and non-fictional Greco-Roman literature. The fact that there were many versions of the genealogical story of Illyrius was ascertained by Ancient Greek historian Appian (1st–2nd century AD). However, only two versions of all these genealogical stories are attested.[52][53] The first version—which reports the legend of Cadmus and Harmonia—was recorded by Euripides and Strabo in accounts that would be presented in detail in Bibliotheca of Pseudo-Apollodorus (1st to 2nd century AD).[54] The second version—which reports the legend of Polyphemus and Galatea—was recorded by Appian (1st–2nd century AD) in his Illyrike.[52]

According to the first version Illyrius was the son of Cadmus and Harmonia, whom the Enchelei had chosen to be their leaders. He eventually ruled Illyria and became the eponymous ancestor of the whole Illyrian people.[55] In one of these versions, Illyrius was named so after Cadmus left him by a river named the Illyrian, where a serpent found and raised him.[54]

Appian writes that many mythological stories were still circulating in his time,[56] and he chose a particular version because it seemed to be the most correct one. Appian's genealogy of tribes is not complete as he writes that other Illyrian tribes exist, which he hasn't included.[54] According to Appian's tradition, Polyphemus and Galatea gave birth to Celtus, Galas, and Illyrius,[57] three brothers, progenitors respectively of Celts, Galatians and Illyrians. Illyrius had multiple sons: Encheleus, Autarieus, Dardanus, Maedus, Taulas and Perrhaebus, and daughters: Partho, Daortho, Dassaro and others. From these, sprang the Taulantii, Parthini, Dardani, Encheleae, Autariates, Dassaretii and the Daorsi. Autareius had a son Pannonius or Paeon and these had sons Scordiscus and Triballus.[5] Appian's genealogy was evidently composed in Roman times encompassing barbarian peoples other than Illyrians like Celts and Galatians.[58] and choosing a specific story for his audience that included most of the peoples who dwelled in the Illyricum of the Antonine era.[56] However, the inclusion in his genealogy of the Enchelei and the Autariatae, whose political strength has been highly weakened, reflects a pre-Roman historical situation.[59][note 3]

Basically, ancient Greeks included in their mythological accounts all the peoples with whom they had close contacts. In Roman times, ancient Romans created more mythical or genealogical relations to include various new peoples, regardless of their large ethnic and cultural differences. Appian's genealogy lists the earliest known peoples of Illyria in the group of the first generation, consisting mostly of southern Illyrian peoples firstly encountered by the Greeks, some of which were the Enchelei, the Taulantii, the Dassaretii and the Parthini.[60][61] Some peoples that came to the Balkans at a later date such as the Scordisci are listed in the group that belongs to the third generation. The Scordisci were a Celtic people mixed with the indigenous Illyrian and Thracian population. The Pannonians have not been known to the Greeks, and it seems that before the 2nd century BC they did not come into contact with the Romans. Almost all the Greek writers referred to the Pannonians with the name Paeones until late Roman times. The Scordisci and Pannonians were considered Illyrian mainly because they belonged to Illyricum since the early Roman Imperial period.[62]

History

Iron Age

Depending on the complexity of the diverse physical geography of the Balkans, arable farming and livestock (mixed farming) rearing had constituted the economic basis of the Illyrians during the Iron Age.

In southern Illyria organized realms were formed earlier than in other areas of this region. One of the oldest known Illyrian kingdoms is that of the Enchelei, which seems to have reached its height from the 8th–7th centuries BC, but the kingdom fell from dominant power around the 6th century BC.[63] It seems that the weakening of the kingdom of Enchelae resulted in their assimilation and inclusion into a newly established Illyrian realm at the latest in the 5th century BC, marking the arising of the Dassaretii, who appear to have replaced the Enchelei in the lakeland area of Lychnidus.[64][65] According to a number of modern scholars the dynasty of Bardylis—the first attested Illyrian dynasty—was Dassaretan.[66][note 4]

The weakening of the Enchelean realm was also caused by the strengthening of another Illyrian kingdom established in its vicinity—that of the Taulantii—which existed for some time along with that of the Enchelei.[70] The Taulantii—another people among the more anciently known groups of Illyrian tribes—lived on the Adriatic coast of southern Illyria (modern Albania), dominating at various times much of the plain between the Drin and the Aous, comprising the area around Epidamnus/Dyrrhachium.[71][note 5] In the 7th century BC the Taulantii invoked the aid of Corcyra and Corinth in a war against the Liburni. After the defeat and expulsion from the region of the Liburni, the Corcyreans founded in 627 BC on the Illyrian mainland a colony called Epidamnus, thought to have been the name of a barbarian king of the region.[73] A flourishing commercial centre emerged and the city grew rapidly. The Taulantii continued to play an important role in Illyrian history between the 5th and 4th–3rd centuries BC, and in particular, in the history of Epidamnus, both as its neighbors and as part of its population. Notably they influenced the affairs in the internal conflicts between aristocrats and democrats.[74][75] The Taulantian kingdom seems to have reached its climax during Glaukias' rule, in the years between 335 BC and 302 BC.[76][77][78]

The Illyrian kingdoms frequently came into conflicts with the neighbouring Ancient Macedonians, and the Illyrian pirates were also seen as significant threat to the neighbouring peoples.[79]

At the Neretva Delta, there was a strong Hellenistic influence on the Illyrian tribe of Daors. Their capital was Daorson located in Ošanići near Stolac in Herzegovina, which became the main center of classical Illyrian culture. Daorson, during the 4th century BC, was surrounded by megalithic, 5 meter high stonewalls, composed out of large trapeze stones blocks. Daors also made unique bronze coins and sculptures. The Illyrians even conquered Greek colonies on the Dalmatian islands.

After Philip II of Macedon defeated Bardylis (358 BC), the Grabaei under Grabos II became the strongest state in Illyria.[80] Philip II killed 7,000 Illyrians in a great victory and annexed the territory up to Lake Ohrid. Next, Philip II reduced the Grabaei, and then went for the Ardiaei, defeated the Triballi (339 BC), and fought with Pleurias (337 BC).[81]

During the second part of the 3rd century BC, a number of Illyrian tribes seem to have united to form a proto-state stretching from the central part of present-day Albania up to Neretva river in Herzegovina. The political entity was financed on piracy and ruled from 250 BC by the king Agron. The Illyrian attack under Agron, against Aerolians mounted in either 232 or 231 BC, is described by Polybius:

One hundred lembi with 5000 men on board sailed up to land at Medion. Dropping anchor at daybreak, they disembarked speedily and in secret. They then formed up in the order that was usual in their own country, and advanced in their several companies against the Aetolian lines. The latter were overwhelmed with astonishment at the unexpected nature and boldness of the move; but they had long been inspired with overweening self-confidence, and having full reliance on their own forces were far from being dismayed. They drew up the greater part of their hoplites and cavalry in front of their own lines on the level ground, and with a portion of their cavalry and their light infantry they hastened to occupy some rising ground in front of their camp, which nature had made easily defensible. A single charge, however, of the Illyrians, whose numbers and close order gave them irresistible weight, served to dislodge the light-armed troops, and forced the cavalry who were on the ground with them to retire to the hoplites. But the Illyrians, being on higher ground, and charging down on from it upon the Aetolian trrops formed up on the plain, routed them without difficulty. The Medionians joined the action by sallying out of the town and charging the Aetolians, thus, after killing a great number, and taking a still greater number prisoners, and becoming masters also of their arms and baggage, the Illyrians, having carried out the orders of Agron, conveyed their baggage and the rest of their booty to their boats and immediately set sail for their own country.[82]

He was succeeded by his wife Teuta, who assumed the regency for her stepson Pinnes following Agron's death in 231 BC.[83]

In his work The Histories, Polybius (2nd century BC) reported first diplomatic contacts between the Romans and Illyrians.[84] In the Illyrian Wars of 229 BC, 219 BC and 168 BC, Rome overran the Illyrian settlements and suppressed the piracy that had made the Adriatic unsafe for Roman commerce.[85] There were three campaigns, the first against Teuta the second against Demetrius of Pharos and the third against Gentius.[86] The initial campaign in 229 BC marks the first time that the Roman Navy crossed the Adriatic Sea to launch an invasion.[87] The impetus behind the emergence of larger regional groups, such as "Iapodes", "Liburnians", "Pannonians" etc., is traced to increased contacts with the Mediterranean and La Tène 'global worlds'.[88] This catalyzed "the development of more complex political institutions and the increase in differences between individual communities".[89] Emerging local elites selectively adopted either La Tène or Hellenistic and, later, Roman cultural templates "in order to legitimize and strengthen domination within their communities. They were competing fiercely through either alliance or conflict and resistance to Roman expansion. Thus, they established more complex political alliances, which convinced (Greco-Roman) sources to see them as ‘ethnic’ identities."[90]

The Roman Republic subdued the Illyrians during the 2nd century BC. An Illyrian revolt was crushed under Augustus, resulting in the division of Illyria in the provinces of Pannonia in the north and Dalmatia in the south. Depictions of the Illyrians, usually described as "barbarians" or "savages", are universally negative in Greek and Roman sources.[91]

Roman era and Late Antiquity

Prior to the Roman conquest of Illyria, the Roman Republic had started expanding its power and territory across the Adriatic Sea. The Romans came nevertheless into a series of conflicts with the Illyrians, equally known as the Illyrian Wars, beginning in 229 BC until 168 BC as the Romans defeated Gentius at Scodra.[92] The Great Illyrian Uprising took place in the Roman province of Illyricum in the 1st century AD, in which an alliance of native peoples revolted against the Romans. The main ancient source that describes this military conflict is Velleius Paterculus, which was incorporated into the second book of Roman History. Another ancient source about it is the biography of Octavius Augustus by Pliny the Elder.[93] The two leaders of uprising were Bato the Breucian and Bato the Daesitiate.

Geographically, the name 'Illyria' came to mean Roman Illyricum which from the 4th century to the 7th century signified the prefecture of Illyricum. It covered much of the western and central Balkans. After the defeat of the Great Illyrian Revolt and the consolidation of Roman power in the Balkans, the process of integration of Illyrians in the Roman world began. Some Illyrian communities were organized in their pre-Roman locations under their own civitates. Others migrated or were forcefully resettled in different regions. Some groups like the Azali were transferred from their homeland to frontier areas (northern Hungary) after the Great Illyrian Revolt. In Dacia, Illyrian communities like the Pirustae who were skilled miners were settled to the gold mines of Alburnus Maior where they formed their own communities. In Trajan's period these population movements were likely part of a deliberate policy of resettling, while later they involved free migrations. In their new regions, they were free salaried workers. Inscriptions show that by that era many of them had acquired Roman citizenship.[94]

By the 3rd century CE, Illyrian populations had been highly integrated in the Roman Empire and formed a core population of its Balkan provinces. During the crisis of the Third Century and the establishment of the Dominate, a new elite faction of Illyrians who were part of the Roman army along the Pannonian and Danubian limes rose in Roman politics. This faction produced many emperors from the late 3rd to the 6th century CE who are collectively known as the Illyrian Emperors and include the Constantinian, Valentinianic and Justinianic dynasties.[95][96][97][98][99] Gaius Messius Quintus Traianus Decius , a native of Sirmium, is usually recognized as the first Illyrian emperor in historiography.[100] The rise of the Illyrian Emperors represents the rise of the role of the army in imperial politics and the increasing shift of the center of imperial politics from the city of Rome itself to the eastern provinces of the empire.

The term Illyrians last appears in the historical record in the 7th century AD, in the Miracula Sancti Demetrii, referring to a Byzantine garrison operating within the former Roman province of Illyricum.[6][101] However, in the acts of the Second Council of Nicaea from 787, Nikephoros of Durrës signed himself as "Episcopus of Durrës, province of the Illyrians".[102] Since the Middle Ages the term "Illyrian" has been used principally in connection with the Albanians, although it was also used to describe the western wing of the Southern Slavs up to the 19th century,[103] being revived in particular during the Habsburg monarchy.[104][105] In Byzantine literature, references to Illyria as a defined region in administrative terms end after 1204 and the term specifically began to refer only to the more confined Albanian territory.[106]

Society

Social and political organisation

The structure of Illyrian society during classical antiquity was characterised by a conglomeration of numerous tribes and small realms ruled by warrior elites, a situation similar like that in most other societies at that time. Thucidides in the History of the Peloponnesian War (5th century BC) addresses the social organisation of the Illyrian tribes via a speech he attributes to Brasidas, in which he recounts that the mode of rulership among the Illyrian tribes is that of dynasteia—which Thucidides used in reference to foreign customs—neither democratic, nor oligarchic. Brasidas then goes on to explain that in the dynasteia the ruler rose to power "by no other means than by superiority in fighting".[107] Pseudo-Scymnus (2nd century BC) in reference to the social organisation of Illyrian tribes in earlier times than the era he lived in makes a distinction between three modes of social organisation. A part of the Illyrians were organized under hereditary kingdoms, a second part was organized under chieftains who were elected but held no hereditary power and some Illyrians were organised in autonomous communities governed by their own internal tribal laws. In these communities social stratification had not yet emerged.[108]

Warfare

The history of Illyrian warfare and weaponry spanned from around the 10th century BC up to the 1st century AD in the region defined by the Ancient Greek and Roman historians as Illyria. It concerns the armed conflicts of the Illyrian tribes and their kingdoms in the Balkan Peninsula and the Italian Peninsula as well as their pirate activity in the Adriatic Sea within the Mediterranean Sea.

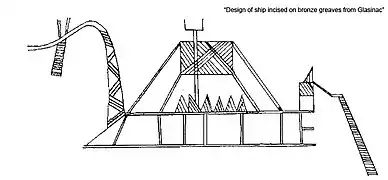

The Illyrians were a notorious seafaring people with a strong reputation for piracy especially common during the regency of king Agron and later queen Teuta.[109][110] They used fast and maneuverable ships of types known as lembus and liburna which were subsequently used by the Ancient Macedonians and Romans.[111] Livy described the Illyrians along the Liburnians and Istrians as nations of savages in general noted for their piracy.[112]

Illyria appears in Greco-Roman historiography from the 4th century BC. Illyrians were regarded as bloodthirsty, unpredictable, turbulent, and warlike by Ancient Greeks and Romans.[113] They were seen as savages on the edge of their world.[91] Polybius (3rd century BC) wrote: "the Romans had freed the Greeks from the enemies of all mankind".[114] According to the Romans, the Illyrians were tall and well-built.[115] Herodianus writes that "Pannonians are tall and strong always ready for a fight and to face danger but slow witted".[116] Illyrian rulers wore bronze torques around their necks.[117]

Apart from conflicts between Illyrians and neighbouring nations and tribes, numerous wars were recorded among Illyrian tribes too.

Illyrian ship dating from the 8th–7th century BC

Illyrian ship dating from the 8th–7th century BC The Sica

The Sica Illyrian type helmet

Illyrian type helmet

Culture

Language

The languages spoken by the Illyrian tribes are an extinct and poorly attested Indo-European language group, and it is not clear whether the languages belonged to the centum or the satem group. The Illyrians were subject to varying degrees of Celticization, Hellenization, Romanization and later Slavicization which possibly lead to the extinction of their languages.[118][119][120] In modern research, use of concepts like "Hellenization" and "Romanization" has declined as they have been criticized as simplistic notions which can't describe the actual processes via which material development moved from the centres of the ancient Mediterranean to its periphery.[91]

The vast majority of knowledge of Illyrian is based on the Messapian language if the latter is considered an Illyrian dialect.[121] The non-Messapian testimonies of Illyrian are too fragmentary to allow any conclusions whether Messapian should be considered part of Illyrian proper, although it has been widely thought that Messapian was related to Illyrian. An extinct Indo-European language, Messapian was once spoken in Messapia in the southeastern Italian Peninsula. It was spoken by the three Iapygian tribes of the region, the Messapians, the Daunii and the Peucetii.

On both sides on the border region between southern Illyria and northern Epirus the contact between the Illyrian and Greek languages produced an area of bilingualism between the two, although it is unclear how the impact of the one language to the other developed because of the scarcity of available archaeological material. However, this did not occur at the same level on both sides, with the Illyrians being more willing to adopt the more prestigious Greek language.[122][123] Ongoing research may provide further knowledge about these contacts beyond present limited sources.[123] Illyrians were exposed not only to Doric and Epirote Greek but also to Attic-Ionic.[123]

The Illyrian languages were once thought to be connected to the Venetic language in the Italian Peninsula but this view was abandoned.[124] Other scholars have linked them with the adjacent Thracian language supposing an intermediate convergence area or dialect continuum, but this view is also not generally supported. All these languages were likely extinct by the 5th century AD although traditionally, the Albanian language is identified as the descendant of Illyrian dialects that survived in remote areas of the Balkans during the Middle Ages but evidence "is too meager and contradictory for us to know whether the term Illyrian even referred to a single language".[125][126]

The ancestor dialects of the Albanian language would have survived somewhere along the boundary of Latin and Ancient Greek linguistic influence, the Jireček Line. There are various modern historians and linguists who believe that the modern Albanian language might have descended from a southern Illyrian dialect whereas an alternative hypothesis holds that Albanian was descended from the Thracian language.[127][125] Not enough is known of the ancient language to completely prove or disprove either hypothesis, see Origin of the Albanians.[128]

Linguistic evidence and subgrouping

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

Modern studies about Illyrian onomastics, the main field via which the Illyrians have been linguistically investigated as no written records have been found, began in the 1920s and sought to more accurately define Illyrian tribes, the commonalities, relations and differences between each other as they were conditioned by specific local cultural, ecological and economic factors, which further subdivided them into different groupings.[129][130] This approach has led in contemporary research in the definition of three main onomastic provinces in which Illyrian personal names appear near exclusively in the archaeological material of each province. The southern Illyrian or south-eastern Dalmatian province was the area of the proper Illyrians (the core of which was the territory of Illyrii proprie dicti of the classical authors, located in modern Albania) and includes most of Albania, Montenegro and their hinterlands. This area extended along the Adriatic coast from the Aous valley[28] in the south, up to and beyond the Neretva valley in the north.[28][131] The second onomastic province, the central Illyrian or middle Dalmatian-Pannonian province began to its north and covered a larger area than the southern province. It extended along the Adriatic coast between the Krka and Cetina rivers, covered much of Bosnia (except for its northern regions), central Dalmatia (Lika) and its hinterland in the central Balkans included western Serbia and Sandžak. The third onomastic province further to the north defined as North Adriatic area includes Liburnia and the region of modern Ljubljana in Slovenia. It is part of a larger linguistic area different from Illyrian that also comprises Venetic and its Istrian variety. These areas are not strictly defined geographically as there was some overlap between them.[132][133][131] The region of the Dardani (modern Kosovo, parts of northern North Macedonia, parts of eastern Serbia) saw the overlap of the southern Illyrian and Dalmatian onomastic provinces. Local Illyrian anthroponymy is also found in the area.[134]

In its onomastics, southern Illyrian (or south-east Dalmatian) has close relations with Messapic. Most of these relations are shared with the central Dalmatian area.[135] In older scholarship (Crossland (1982)), some toponyms in central and northern Greece show phonetic characteristics that were thought to indicate that Illyrians or closely related peoples were settled in those regions before the introduction of the Greek language.[136] However, such views largely relied on subjective ancient testimonies and are not supported by the earliest evidence (epigraphic etc.).[137]

Religion

The Illyrians, as most ancient civilizations, were polytheistic and worshipped many gods and deities developed of the powers of nature. The most numerous traces—still insufficiently studied—of religious practices of the pre-Roman era are those relating to religious symbolism. Symbols are depicted in every variety of ornament and reveal that the chief object of the prehistoric cult of the Illyrians was the Sun,[138][139] worshipped in a widespread and complex religious system.[138] The solar deity was depicted as a geometrical figure such as the spiral, the concentric circle and the swastika, or as an animal figure the likes of the birds, serpents and horses.[140][139] The symbols of water-fowl and horses were more common in the north, while the serpent was more common in the south.[139] Illyrian deities were mentioned in inscriptions on statues, monuments, and coins of the Roman period, and some interpreted by Ancient writers through comparative religion.[141][142] There appears to be no single most prominent god for all the Illyrian tribes, and a number of deities evidently appear only in specific regions.[141]

In Illyris, Dei-pátrous was a god worshiped as the Sky Father, Prende was the love-goddess and the consort of the thunder-god Perendi, En or Enji was the fire-god, Jupiter Parthinus was a chief deity of the Parthini, Redon was a tutelary deity of sailors appearing on many inscriptions in the coastal towns of Lissus, Daorson, Scodra and Dyrrhachium, while Medaurus was the protector deity of Risinium, with a monumental equestrian statue dominating the city from the acropolis. In Dalmatia and Pannonia one of the most popular ritual traditions during the Roman period was the cult of the Roman tutelary deity of the wild, woods and fields Silvanus, depicted with iconography of Pan. The Roman deity of wine, fertility and freedom Liber was worshipped with the attributes of Silvanus, and those of Terminus, the god protector of boundaries. Tadenus was a Dalmatian deity bearing the identity or epithet of Apollo in inscriptions found near the source of the Bosna river. The Delmatae also had Armatus as a war god in Delminium. The Silvanae, a feminine plural of Silvanus, were featured on many dedications across Pannonia. In the hot springs of Topusko (Pannonia Superior), sacrificial altars were dedicated to Vidasus and Thana (identified with Silvanus and Diana), whose names invariably stand side by side as companions. Aecorna or Arquornia was a lake or river tutelary goddess worshipped exclusively in the cities of Nauportus and Emona, where she was the most important deity next to Jupiter. Laburus was also a local deity worshipped in Emona, perhaps a deity protecting the boatmen sailing.

It seems that the Illyrians did not develop a uniform cosmology on which to center their religious practices.[139] A number of Illyrian toponyms and anthroponyms derived from animal names and reflected the beliefs in animals as mythological ancestors and protectors.[143] The serpent was one of the most important animal totems.[144] Illyrians believed in the force of spells and the evil eye, in the magic power of protective and beneficial amulets which could avert the evil eye or the bad intentions of enemies.[138][141] Human sacrifice also played a role in the lives of the Illyrians.[145] Arrian records the chieftain Cleitus the Illyrian as sacrificing three boys, three girls and three rams just before his battle with Alexander the Great.[146] The most common type of burial among the Iron Age Illyrians was tumulus or mound burial. The kin of the first tumuli was buried around that, and the higher the status of those in these burials the higher the mound. Archaeology has found many artifacts placed within these tumuli such as weapons, ornaments, garments and clay vessels. The rich spectrum in religious beliefs and burial rituals that emerged in Illyria, especially during the Roman period, may reflect the variation in cultural identities in this region.[147]

Archaeology

In total, at least six material cultures have been described to have emerged in Illyrian territories. Based on existing archaeological finds, comparative archaeological and geographical definition about them has been difficult.[148] Archaeogenetic studies have shown that a major Y-DNA haplogroup among Illyrians, J-L283 spread via Cetina culture across the eastern Adriatic from the Cetina valley in Croatia to Montenegro and northern Albania. The earliest archaeogenetic find related to Cetina in Albania is the Shkrel tumulus (19th century BCE). It is the oldest J-L283 find in the region historically known as Illyria. Freilich et al. (2021) determined that Cetina related samples from Veliki Vanik carry similar ancestry to a Copper Age sample from the site of Beli Manastir-Popova Zemlja (late Vučedol culture), eastern Croatia. The same autosomal profile persists in the Iron Age sample from Jazinka cave.[38] Cetina finds have been found in the western Adriatic since the second half of the thirds millenium in southern Italy. In Albania, new excavations show spread of Cetina culture in sites of central Albania (Blazi, Nezir, Keputa). Inland Cetina spread in Bosnia and Herzegovina, in particular Kotorac, a site near Sarajevo and contacts have been demonstrated with the Belotić Bela Crkva culture.[149] During the developed Middle Bronze Age, Belotić Bela Crkva which has been recognized as another Proto-Illyrian culture developed in northeastern Bosnia and western Serbia (Čačak area). Both inhumation and cremation have been observed in sites of this culture. Similar burial customs have been observed in the Glasinac plateau of eastern Bosnia, where the Glasinac-Mati culture first developed.[150]

During the 7th century BC, the beginning of the Iron Age, the Illyrians emerge as an ethnic group with a distinct culture and art form. Various Illyrian tribes appeared, under the influence of the Halstatt cultures from the north, and they organized their regional centers.[151] The cult of the dead played an important role in the lives of the Illyrians, which is seen in their carefully made burials and burial ceremonies, as well as the richness of the burial sites. In the northern parts of the Balkans, there existed a long tradition of cremation and burial in shallow graves, while in the southern parts, the dead were buried in large stone, or earth tumuli (natively called gromile) that in Herzegovina were reaching monumental sizes, more than 50 meters wide and 5 meters high. The Japodian tribe (found from Istria in Croatia to Bihać in Bosnia) have had an affinity for decoration with heavy, oversized necklaces out of yellow, blue or white glass paste, and large bronze fibulas, as well as spiral bracelets, diadems and helmets out of bronze. Small sculptures out of jade in form of archaic Ionian plastic are also characteristically Japodian. Numerous monumental sculptures are preserved, as well as walls of citadel Nezakcij near Pula, one of numerous Istrian cities from Iron Age. Illyrian chiefs wore bronze torques around their necks much like the Celts did.[152] The Illyrians were influenced by the Celts in many cultural and material aspects and some of them were Celticized, especially the tribes in Dalmatia[153] and the Pannonians.[154] In Slovenia, the Vače situla was discovered in 1882 and attributed to Illyrians. Prehistoric remains indicate no more than average height, male 165 cm (5 ft 5 in), female 153 cm (5 ft 0 in).[116]

Early Middle Ages

It is also evident that in a region which stretches from the southern Dalmatian coast, its hinterland, Montenegro, northern Albania up to Kosovo and Dardania, apart from a uniformity in onomastics there were also some archaeological similarities. However, it cannot be determined whether these tribes living there also formed a linguistic unity.[155]

The Komani-Kruja culture is an archaeological culture attested from late antiquity to the Middle Ages in central and northern Albania, southern Montenegro and similar sites in the western parts of North Macedonia. It consists of settlements usually built below hillforts along the Lezhë (Praevalitana)-Dardania and Via Egnatia road networks which connected the Adriatic coastline with the central Balkan Roman provinces. Its type site is Komani and its fort on the nearby Dalmace hill in the Drin river valley. Kruja and Lezha represent significant sites of the culture. The population of Komani-Kruja represents a local, non-Slavic western Balkan people which was linked to the Roman Justinianic military system of forts. The development of Komani-Kruja is significant for the study of the transition between the classical antiquity population of Albania to the medieval Albanians who were attested in historical records in the 11th century. Within Albanian archaeology, based on the continuity of pre-Roman Illyrian forms in the production of several types of local objects found in graves, the population of Komani-Kruja is framed as a group which descended from the local Illyrians who "re-asserted their independence" from the Roman Empire after many centuries and formed the core of the later historical region of Arbanon.[156] Illyrian-Albanian links were the main focus of Albanian nationalism during the Communism period.[157] What was established in this early phase of research was that Komani-Kruja settlements represented a local, non-Slavic population which has been described as Romanized Illyrian, Latin-speaking or Latin-literate.[158][159] This is corroborated by the absence of Slavic toponyms and survival of Latin ones in the Komani-Kruja area. In terms of historiography, the thesis of older Albanian archaeology is an untestable hypothesis as no historical sources exist which can link Komani-Kruja to the first definite attestation of medieval Albanians in the 11th century.[158][159] The nationalist interpretation of the Komani-Kruja cemeteries has been roundly rejected by non-Albanian scholars. John Wilkes has described it as "a highly improbable reconstruction of Albanian history". Some Albanian scholars even today have continued to espouse this model of continuity.[160]

Limited excavations campaigns occurred until the 1990s. Objects from a vast area covering nearby regions the entire Byzantine Empire, the northern Balkans and Hungary and sea routes from Sicily to Crimea were found in Dalmace and other sites coming from many different production centres: local, Byzantine, Sicilian, Avar-Slavic, Hungarian, Crimean and even possibly Merovingian and Carolingian. Within Albanian archaeology, based on the continuity of pre-Roman Illyrian forms in the production of several types of local objects found in graves, the population of Komani-Kruja was framed as a group which descended from the local Illyrians who "re-asserted their independence" from the Roman Empire after many centuries and formed the core of the later historical region of Arbanon.[156] As research focused almost entirely on grave contexts and burial sites, settlements and living spaces were often ignored.[161] Other views stressed that as an archaeological culture it shouldn't be connected to a single social or ethnic group but be contextualized in a broader Roman-Byzantine or Christian framework, nor should material finds be separated in ethnic categories as they can't be correlated to a specific culture. In this view, cemeteries from nearby regions which were classified as belonging to Slavic groups shouldn't be viewed as necessarily representing another people but as representations of class and other social factors as "ethnic identity was only one factor of varying importance".[162] Yugoslav archaeology proposed an opposite narrative and tried to frame the population as Slavic, especially in the region of western Macedonia.[163] Archaeological research has shown that these sites were not related to regions then inhabited by Slavs and even in regions like Macedonia, no Slavic settlements had been founded in the 7th century.[164]

Archaeologically, while it was considered possible and even likely that Komani-Kruja sites were used continuously from the 7th century onwards, it remained an untested hypothesis as research was still limited.[165] Whether this population represented local continuity or arrived at an earlier period from a more northern location as the Slavs entered the Balkans remained unclear at the time but regardless of their ultimate geographical origins, these groups maintained Justinianic era cultural traditions of the 6th century possibly as a statement of their collective identity and derived their material cultural references from the Justinianic military system.[166] In this context, they may have used burial customs as a means of reference to an "idealized image of the past Roman power".[166]

Research greatly expanded after 2009, and the first survey of Komani's topography was produced in 2014. Until then, except for the area of the cemetery, the size of the settlement and its extension remained unknown. In 2014, it was revealed that Komani occupied an area of more than 40 ha, a much larger territory than originally thought. Its oldest settlement phase dates to the Hellenistic era.[167] Proper development began in late antiquity and continued well into the Middle Ages (13th-14th centuries). It indicates that Komani was a late Roman fort and an important trading node in the networks of Praevalitana and Dardania. Participation in trade networks of the eastern Mediterranean via sea routes seems to have been very limited even in nearby coastal territory in this era.[168] The collapse of the Roman administration in the Balkans was followed by a broad demographic collapse with the exception of Komani-Kruja and neighbouring mountainous regions.[169] In the Avar-Slavic raids, communities from present-day northern Albania and nearby areas clustered around hill sites for better protection as is the case of other areas like Lezha and Sarda. During the 7th century, as Byzantine authority was reestablished after the Avar-Slavic raids and the prosperity of the settlements increased, Komani saw an increase in population and a new elite began to take shape. Increase in population and wealth was marked by the establishment of new settlements and new churches in their vicinity. Komani formed a local network with Lezha and Kruja and in turn this network was integrated in the wider Byzantine Mediterranean world, maintained contacts with the northern Balkans and engaged in long-distance trade.[170] Winnifrith (2020) recently described this population as the survival of a "Latin-Illyrian" culture which emerged later in historical records as Albanians and Vlachs. In Winnifrith's view, the geographical conditions of northern Albania favored the continuation of the Albanian language in hilly and mountainous areas as opposed to lowland valleys.[171] He adds that the language and religion of this culture remain uncertain. With bishops absent abroad, "the mountain flocks cannot have been too versed in theological or linguistic niceties".[171]

Nationalism

Albanians

The possible continuity between the Illyrian populations of the Western Balkans in antiquity and the Albanians has played a significant role in Albanian nationalism from the 19th century until the present day.[172][173]

South Slavs

At the beginning of the 19th century, many educated Europeans regarded the South Slavs as the descendants of ancient Illyrians. However, this is incorrect as Southern Slavs are descendants of Slavic tribes that migrated to the Balkans. Consequently, when Napoléon conquered part of the South Slavic lands, these areas were named after ancient Illyrian provinces (1809–1814).[174] After the demise of the First French Empire in 1815, the Habsburg monarchy became increasingly centralized and authoritarian, and fear of Magyarization arouse patriotic resistance among Croatians.[175] Under the influence of Romantic nationalism, a self-identified "Illyrian movement", in the form of a Croatian national revival, opened a literary and journalistic campaign initiated by a group of young Croatian intellectuals during the years of 1835–49.[176][177]

In Popular Culture

- The plot of 2022 movie Illyricvm is set in 37 BC and it deals with interactions between Romans and Illyrian tribes.[178]

See also

- Prehistory of the Balkans

- List of ancient Illyrian peoples and tribes

- List of rulers in Illyria

- List of settlements in Illyria

- Proposed Illyrian vocabulary

- List of ancient tribes in Illyria

- Adriatic Veneti

- Origin of Albanians

- History of Albania

- Early history of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- History of Croatia before the Croats

- Prehistoric Serbia

Notes

- The political status of Kosovo is disputed. Having unilaterally declared independence from Serbia in 2008, Kosovo is formally recognised as an independent state by 100 UN member states (with another 13 states recognising it at some point but then withdrawing their recognition) and 93 states not recognizing it, while Serbia continues to claim it as part of its own sovereign territory.

- Hecataeus' works can only be analyzed indirectly since the fragments have been preserved in the works of other ancient authors. The majority of the fragments are transmitted in the geographical lexicon (Ἐθνικά, Ethnica) of Stephanus of Byzantium (6th century AD), of which we possess only a later abridgment (epitome by Hermolaos). On the other hand, Stephanus is regarded by modern scholars a reliable source in general.[10][11]

- According to Borza due to the fact that the Illyrian tribes moved constantly there are no precise borders of 'Illyris' by Ancient Greek authors. Illyris approximately consisted an area located north of Epirus and western Macedonia,[14] and covered northern and central Albanian down to the mouth of the Aous.[15] According to Crossland (1982), Greeks of the 5th century B.C. recognized the Illyrii (Ἰλλυριοί) as an important non-Greek people living to the north of the Aetolians and the Acarnanians and further north in the territory of modern-day central and northern Albania, where Epidamnus/Dyrrhachium and Apollonia were founded by Greek colonists.[16] The Aous river, traditionally seen as a border region between Illyria and Epirus has been challenged as having such a status in contemporary research. Rather a transboundary area existed between Illyrians and tribes of Epirus which included the land of the Atintanians in the north and Tymphaea to the south. More recent scholarship places the Ceraunian Mountains as the barrier between Illyrians and the tribes of Epirus. But this mountainous barrier did not act as a border but rather as an area of cultural meeting.[1][17]

- According to some modern scholars Appian's Illyrian genealogy ultimately originated with Timaeus. Appian's immediate source probably was Timagenes, who was also used by Pompeius Trogus for the early history of the Illyrians.[59]

- There is also another historical reconstruction that considers Bardylis a Dardanian ruler, who during the expansion of his dominion included the region of Dassaretis in his realm, but this interpretation has been challenged by historians who consider Dardania too far north for the events involving the Illyrian king Bardylis and his dynasty.[67][68][69]

- When describing the Illyrian invasion of Macedonia ruled by Argaeus I, somewhere between 678 and 640 BC, the historian Polyaenus (fl. 2nd-century CE) recorded the oldest known king in Illyria, Galaurus or Galabrus, a ruler of the Taulantii who reigned in the latter part of the 7th century BC. However, nothing guarantees the authenticity of Polyaenus' passage.[72]

References

- Dausse 2015, p. 28:La cartographie récente de Lauriane Martinez-Sève41 fait apparaître une vaste zone entre Illyrie, Épire et Macédoine, constituée du nord au sud de l'Atintanie, de la Paravée et de la Tymphée. (..) De celle-ci dépend la frontière entre Illyriens et Épirotes. Elle s'applique en revanche moins bien au fleuve Aoos pour définir une frontière entre Épire et Illyrie. Pour les zones de montagnes, nous pouvons citer les monts Acrocérauniens qui pourraient marquer le passage entre la partie chaone de l'Épire et l'Illyrie. Mais la plupart du temps, la montagne est le lieu de vie de nombreuses populations de la Grèce du Nord. À ce titre, elle constitue plus un lieu de rencontre qu'une barrière.

- Wilkes 1992, pp. 6, 92; Boardman & Hammond 1982, p. 261

- Roisman & Worthington 2010, p. 280.

- Boardman 1982, p. 629.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 92.

- Schaefer 2008, p. 130.

- Dzino 2014, pp. 45–46.

- Matijasić 2011, p. 293.

- Dzino 2014, pp. 47–48.

- Matijasić 2011, p. 295–296.

- Matijasić 2015, p. 132.

- Katičić 1976, pp. 154–155.

- Katičić 1976, p. 156.

- Borza, 1991, p. 191: "Illyrian tribes moved about constantly, and there are no fixed land borders to the area known by the Greeks as 'Illyris'. Rouphly speaking, Illyris consisted of the large region north of Epirus and western Macedonia..."

- Hammond 1994, p. 438: Illyris', a geographical term which the Greeks applied to a territory neighbouring their own, covers more or less the area of northern and central Albania down to the mouth of the Aous.

- Crossland 1982, p. 839: "Greeks of the fifth century B.C. knew the Illyrii as an important non-Greek people living to the north of the Aetolians and the Acarnanians and further north in the territory which now forms central and northern Albania, where Greek colonists had founded Epidamnus (Dyrrhachium) and Apollonia."

- Wilkes 1992, p. 97.

- Crossland 1982, p. 841.

- Wilkes 1992, pp. 81, 183.

- Hammond 1966, p. 241.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 93-96: From this it has been inferred that if the first Greek contacts with a people called Illyrians took place when the latter dwelt around the Lake of Scodra, that is, north of the Taulantii and Parthini, there must have occurred later a southward movement of Illyrian people into an area once inhabited by Greek speakers. There may be some coincidence between this notional Illyrian expansion with a southward movement of iron-using peoples early in the first millennium BC, ....as far as the river Aous (Vijose)..

- Wilkes 1992, p. 38.

- Elsie 2015, p. 2.

- Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (7 July 2011). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. John Wiley & Sons. p. 280. ISBN 978-1-4443-5163-7.

- Dzino 2014, p. 47.

- Dzino 2014, p. 46.

- Garašanin 1982, pp. 585–586.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 92

- Wilkes 1992, p. 33–35, 39.

- Dzino 2014b, p. 15–19.

- Lazaridis & Alpaslan-Roodenberg 2022, pp. 8, 10–11, 13.

- Šašel Kos 2005, p. 235.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 39.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 38, 81.

- Stipčević 1977, p. 17.

- Dzino 2014b, p. 13–19.

- Mathieson I, Alpaslan-Roodenberg S, Posth C, Szécsényi-Nagy A, Rohland N, Mallick S, et al. (March 2018). "The genomic history of southeastern Europe". Nature. 555 (7695): 197–203. Bibcode:2018Natur.555..197M. doi:10.1038/nature25778. PMC 6091220. PMID 29466330.

- Freilich et al. 2021.

- Patterson, Nick; et al. (2022). "Large-scale migration into Britain during the Middle to Late Bronze Age" (PDF). Nature. 601 (7894): 588–594. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04287-4. PMC 8889665. PMID 34937049. S2CID 245509501.

- Lazaridis & Alpaslan-Roodenberg 2022: Supplementary Files, Table S1 / Supplementary Materials

- Lazaridis & Alpaslan-Roodenberg 2022, pp. 256: Supplementary Materials

- Lazaridis & Alpaslan-Roodenberg 2022, pp. 220: Supplementary Materials

- Aneli, Serena; Saupe, Tina; Montinaro, Francesco; Solnik, Anu; Molinaro, Ludovica; Scaggion, Cinzia; Carrara, Nicola; Raveane, Alessandro; Kivisild, Toomas; Metspalu, Mait; Scheib, Christiana; Pagani, Luca (2022). "The genetic origin of Daunians and the Pan-Mediterranean southern Italian Iron Age context". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 39 (2). doi:10.1093/molbev/msac014. PMC 8826970. PMID 35038748.

- Marcus, Joseph H.; et al. (February 24, 2020). "Genetic history from the Middle Neolithic to present on the Mediterranean island of Sardinia". Nature Communications. Nature Research. 11 (939): 939. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11..939M. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-14523-6. PMC 7039977. PMID 32094358.

- Fernandes DM, Mittnik A, Olalde I, Lazaridis I, Cheronet O, Rohland N, et al. (March 2020). "The spread of steppe and Iranian-related ancestry in the islands of the western Mediterranean". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 4 (3): 334–345. doi:10.1038/s41559-020-1102-0. PMC 7080320. PMID 32094539.

- Antonio ML, Gao Z, Moots HM, Lucci M, Candilio F, Sawyer S, et al. (November 2019). "Ancient Rome: A genetic crossroads of Europe and the Mediterranean". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science (published November 8, 2019). 366 (6466): 708–714. Bibcode:2019Sci...366..708A. doi:10.1126/science.aay6826. hdl:2318/1715466. PMC 7093155. PMID 31699931.

sample ID R474 and R116 check on YFull YTree subclade J-L283 list of scientific ancient samples

- Posth, Cosimo; Zaro, Valentina; Spyrou, Maria A. (September 24, 2021). "The origin and legacy of the Etruscans through a 2000-year archeogenomic time transect". Science Advances. Washington DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science. 7 (39): eabi7673. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abi7673. PMC 8462907. PMID 34559560.

sample ID CSN004 for Etruscan, VEN006 and VEN013 for Venosa

- Allentoft, ME (June 11, 2015). "Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia". Nature. Nature Research. 522 (7555): 167–172. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..167A. doi:10.1038/nature14507. PMID 26062507. S2CID 4399103.

sample RISE408, Norabak culture, MLBA, 1212-1010 BCE

- Wang, Chuan-Chao (February 4, 2019). "Ancient human genome-wide data from a 3000-year interval in the Caucasus corresponds with eco-geographic regions Eurasia". Nature Communications. Nature Research. 10 (1): 590. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-08220-8. PMC 6360191. PMID 30713341.

sample KDC001.A0101, BZNK-301/1, Kudachurt, kurgan 14, grave 218, Russia_North_Caucasus 1950-1778 BCE

- Lazaridis & Alpaslan-Roodenberg 2022, pp. 322: Supplementary Materials; J-Z2507 (within J2) is found in 21 individuals ... In the ancient data we find it in 3 samples from Rome,(436) with the earliest being R474.SG (700-600 BCE). All remaining samples are from the Balkans and indeed the Western Balkans (Montenegro, Croatia, Albania) and most of them are from the Bronze Age. Thus, J-Z2507 has a peri-Adriatic ancient distribution in agreement with the present-day distribution and may represent a Bronze Age or later expansion in the area. The immediately upstream nodes of J-Z2507 are J-Z585, J-Z615, J-Z597 with a similar time depth and include two additional Bronze Age samples from Albania and Croatia, and are thus part of the same pattern. J-Z600, the parent node of J-Z585, includes four additional individuals, one of which is from Croatia, and three of which are from the Late Bronze Age Nuragic culture in the island of Sardinia,(20, 453) thus suggesting that this culture included individuals of Bronze Age Western Balkan origin (these might have Italian intermediaries, but we do not detect any J-Z600 in mainland Italy prior to the aforementioned Iron Age sample from Rome)

- Žegarac, Aleksandra; Winkelbach, L; Blöcher, J; Diekmann, Y; Krečković Gavrilović, M (2021). "Ancient genomes provide insights into family structure and the heredity of social status in the early Bronze Age of southeastern Europe". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 10072. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-89090-x. PMC 8115322. PMID 33980902.

- Šašel Kos 2004, pp. 493, 502.

- Šašel Kos 2005, p. 124.

- Šašel Kos 2005, p. 124

- Grimal & Maxwell-Hyslop 1996, p. 230; Apollodorus & Hard 1999, p. 103 (Book III, 5.4)

- Šašel Kos 2004, p. 493.

- Grimal & Maxwell-Hyslop 1996, p. 168.

- Katičić 1995, p. 246.

- Šašel Kos 2005, p. 123.

- Šašel Kos 2004, p. 502.

- Papazoglu 1978, p. 213.

- Šašel Kos 2004, p. 503.

- Stipčević 1989, p. 34.

- Šašel Kos 2004, p. 500.

- Castiglioni 2010, pp. 93–95.

- Mortensen 1991, pp. 49–59; Cabanes 2002, pp. 50–51, 56, 75; Castiglioni 2010, p. 58; Lane Fox 2011, p. 342; Cambi, Čače & Kirigin 2002, p. 106; Mesihović & Šačić 2015, pp. 129–130.

- Cabanes 2002, pp. 50–51, 56, 75.

- Mortensen 1991, pp. 49–59.

- Lane Fox 2011, p. 342.

- Stipčević 1989, p. 35.

- Wilkes 1992, pp. 97–98.

- Cabanes 2002, p. 51.

- Wilkes 1992, pp. 110–111.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 112.

- Mesihović & Šačić 2015, pp. 39–40.

- Dzino 2014, p. 49.

- Wilkes 1992, pp. 112, 122–126.

- Stipčević 1989, pp. 35–36.

- Polybius.

- Hammond 1994, p. 438.

- Hammond 1993, pp. 106–107.

- Polybius 2.3

- Elsie 2015, p. 3.

- Bajrić 2014, p. 29.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 158.

- Boak & Sinnigen 1977, p. 111.

- Gruen 1986, p. 76.

- Dzino 2012, pp. 74–76.

- Dzino 2012, p. 97.

- Dzino 2012, pp. 84–85.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 4

- Battles of the Greek and Roman Worlds: A Chronological Compendium of 667 Battles to 31Bc, from the Historians of the Ancient World (Greenhill Historic Series) by John Drogo Montagu, ISBN 1-85367-389-7, 2000, page 47

- Mesihović 2011, pp. 8, 15.

- Holleran 2016, p. 103.

- Lenski, Noel (2014-06-26). Failure of Empire: Valens and the Roman State in the Fourth Century A.D. Univ of California Press, 2014. pp. 45–67. ISBN 9780520283893.

- Odahl, Charles M. (2001). Constantine and the Christian empire. London: Routledge. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-0-415-17485-5.

- Lenski, Noel Emmanuel (2002). Failure of empire: Valens and the Roman state in the fourth century A.D. University of California Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-520-23332-4. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- Croke, Brian (2001). Count Marcellinus and his chronicle. Oxford University Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-19-815001-5. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- Maas, Michael (2005). The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1139826877.

- Bohec, Yann Le (2013). The Imperial Roman Army. Routledge. p. 83. ISBN 9781135955069.

- Juka 1984, p. 60: "Since the Illyrians are referred to for the last time as an ethnic group in Miracula Sancti Demetri (7th century AD), some scholars maintain that after the arrival of the Slavs the Illyrians were extinct."

- Meksi, Aleksandër (1989) Të dhëna për historinë e hershme mesjetare të Shqipërisë (fundi i shek. VI — fillimi i shek. XI), / Données sur l'histoire médiévale ancienne de l'Albanie Iliria Année 1989, 19-1, p. 120

- Ćirković 2004, p. 2: "The name Illyrian was used to identify the western wing of the Southern Slavs up to the nineteenth century, although since the Middle Ages it has been used primarily in connection with the Albanians."

- Djilas 1991, pp. 20–21.

- Stergar 2016, pp. 111–112.

- Koder 2017, p. 206.

- Matijasić 2011, p. 26.

- Šašel Kos 1993, p. 120.

- The Illyrians (The Peoples of Europe) by John Wilkes, 1996, page 158, "...Illyrian success continued when command passed to Agron's widow Teuta, who granted individual ships a licence to universal plunder. In 231 ac the fleet and army attacked Ells and Messenia..."

- Møller, Bjørn. "Piracy, Maritime Terrorism and Naval Strategy." Copenhagen: Danish Institute for International Studies, November 16, 2008. 10.

- Dell, Harry J. 1967. The Origin and Nature of Illyrian Piracy. Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte 16, (3) (Jul.): 344-58. 345.

- Livy. The History of Rome, Band 2 - The History of Rome, Livy. T. Cadell and W. Davies, 1814. p. 324.

- Whitehorne 1994, p. 37; Eckstein 2008, p. 33; Strauss 2009, p. 21; Everitt 2006, p. 154.

- Champion 2004, p. 113.

- Juvenal 2009, p. 127.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 219.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 223.

- Bunson 1995, p. 202; Mócsy 1974.

- Pomeroy et al. 2008, p. 255

- Bowden 2003, p. 211; Kazhdan 1991, p. 248.

- Arthur Cook, Stanley; Percival Charlesworth, Martin; Bagnell Bury, John; Bernard Bury, John (1924). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press, p. 839

- Malkin 1998, p. 143.

- Filos 2017, pp. 222, 241

- Wilkes 1992, p. 183.

- Eastern Michigan University Linguist List: The Illyrian Language, linguistlist.org; accessed April 3, 2014

- Ammon et al. 2006, p. 1874: "Traditionally, Albanian is identified as the descendant of Illyrian, but Hamp (1994a) argues that the evidence is too meager and contradictory for us to know whether the term Illyrian even referred to a single language."

-

- Ceka 2005, pp. 40–42, 59

- Thunmann, Johannes E. "Untersuchungen uber die Geschichte der Oslichen Europaischen Volger". Teil, Leipzig, 1774.

- see Malcolm, Noel. Origins: Serbs, Vlachs, and Albanians. Malcolm is of the opinion that the Albanian language was an Illyrian dialect preserved in Dardania and then it (re-?)conquered the Albanian lowlands

- Indo-European language and culture: an introduction By Benjamin W. Fortson Edition: 5, illustrated Published by Wiley-Blackwell, 2004 ISBN 1-4051-0316-7, ISBN 978-1-4051-0316-9

- Stipčević, Alexander. Iliri (2nd edition). Zagreb, 1989 (also published in Italian as "Gli Illiri")

- NGL Hammond The Relations of Illyrian Albania with the Greeks and the Romans. In Perspectives on Albania, edited by Tom Winnifrith, St. Martin’s Press, New York 1992

- Encyclopedia of Indo-European culture By J. P. Mallory, Douglas Q. Adams Edition: illustrated Published by Taylor & Francis, 1997 ISBN 1-884964-98-2, ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5

- Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 9;Fortson 2004

- Stipčević 1977, p. 15.

- Fine 1983, pp. 9–10.

- De Simone 2017, p. 1869.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 70.

- Polomé 1982, p. 867.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 86.

- Polomé 1983, p. 537.

- Crossland 1982, pp. 841–842.

- Giannakis, Georgios; Crespo, Emilio; Filos, Panagiotis (2017). Studies in Ancient Greek Dialects: From Central Greece to the Black Sea. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 222. ISBN 9783110532135.

Crossland posited a posited (partial) Hellenization of pre-classical Epirus, with Greek elites ruling over non-Greek populations; cf. Nilsson (1909). A very brief synopsis of older works and views is available in Kokoszko&Witczak (2009,112) who in turn also favor a 'Hellenization' scenario Nonetheless, such views, which rely largely on some subjective ancient testimonies, are no supported by the earliest (and not only) epigraphic evidence.

- Stipčević 1977, p. 182.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 244.

- Stipčević 1977, pp. 182, 186.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 245.

- West 2007, p. 15.

- Stipčević 1977, p. 197.

- Stipčević 1976, p. 235.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 123.

- F. A. Wright (1934). ALEXANDER THE GREAT. London: GEORGE ROUTLEDGE SONS, LTD. pp. 63–64.

- Brandt, Ingvaldsen & Prusac 2014, p. 249.

- Stipčević 1977, p. 107.

- Gori 2018, p. 201.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 34.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 140.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 233.

- Bunson 1995, p. 202; Hornblower & Spawforth 2003, p. 426

- Hornblower & Spawforth 2003, p. 1106

- Matzinger, Joachim (2016). "Die albanische Autochthoniehypotheseaus der Sicht der Sprachwissenschaft" (PDF). Südosteuropa-Institut. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

Das Albanische sei die Nachfolgesprache des Illyrischen: An der sprachlichen Realität des Illyrischen kann prinzipiell nicht gezweifelt werden. Auf welcher Basis beruht aber die heutige Kenntnis des Illyrischen? Nach moderner Erkenntnis ist das, was Illyrisch zu nennen ist, auf den geographischen Bereich der süddalmatischen Küste und ihrem Hinterland zu begrenzen (modernes Crna Gora, Nordalbanien und Kosovo/Kosova [antikes Dardanien]), wo nach älteren griechi-schen Autoren Stämme beheimatet waren, die gemeinhin illyrisch benannt wurden (Hei-ner EICHNER). Das Gebiet deckt sich mit einem auch relativ einheitlichen Namensgebiet (Radoslav KATIČIĆ) und es gibt es zum Teil archäologische Übereinstimmungen (Hermann PARZINGER). Ob diese Stämme auch eine sprachlicheEinheitgebildet haben, lässt sich nicht feststellen. Aus diesem Grund darf der Begriff ‘Illyrer’ und ‘illyrisch’ primär nur als Sammelbegriffverstanden werden

- Wilkes 1996, p. 278.

- Curta, Florin (2013). "Seventh-Century Fibulae with Bent Stem in the Balkans". Archaeologia Bulgarica. 17 (1): 49–70.

In Albania, for a long time, the fibulae with bent stem have been regarded as the foremost element linking the Koman(i) culture to the Iron-Age civilization of the Illyrians, the main focus of Albanian nationalism during the Communist period

- Wilkes 1996, p. 278

- Bowden 2003, p. 61

- Bowden, William (2019). "Conflicting ideologies and the archaeology of Early Medieval Albania". Archeologia Medievale. All’Insegna del Giglio: 47. ISSN 0390-0592.

The nationalist interpretation of the cemeteries has, on the other hand, been roundly rejected by foreign scholars. Wilkes influential volume on the Illyrians described it as "a highly improbable reconstruction of Albanian history", and as noted above, I have published a number of trenchant critiques of it... of the earlier model.

- Nallbani 2017, p. 315.

- Vroom, Joanita (9 October 2017). "Saranda in the waves of time". In Moreland, John; Mitchell, John; Leal, Bea (eds.). Encounters, Excavations and Argosies: Essays for Richard Hodges. Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. p. 249. ISBN 978-1-78491-682-4.

All the cemeteries in south-eastern Albania have exactly the same shapes and incised decoration styles as Lako's ones in Saranda (especially his Nos. 23-27 in Table 3) but are dated later, that is to say between the 8th and 11th/12th centuries. Albanian archaeologists often connect these early medieval cemeteries to the so-called 'Komani-Kruja culture', and associate them with one particurlar ethnic group (regularly described as 'Slavic'). Recently, however, this view has been criticized by other scholars, who prefer to situate the 'Komani-Kruja culture' in a regionalized Romano-Byzantine or Christian context of various ethnic and social groups, adopting additional foreign elements(Popovic 1975:455-457; Popovic 1984: 214-243; Bowden 2003; 210-21; Curta 2006: 103-105). Consequently, we can conclude that the identification of the pottery finds from the Basilica excavation in Saranda with one period (the 6th and 7th centuries) and with one ethnic group (in this case the Slavs) is without doubt erroneous.

- Curta 2012, p. 73.

- Curta 2012, pp. 73–74

- Bowden 2004, p. 229

- Curta 2013

- Nallbani 2017, p. 320.

- Curta 2021, p. 79.

- Curta 2021, p. 314.

- Nallbani 2017, p. 325.

- Winnifrith 2021, pp. 98–99.

- Dzino 2014b, p. 11, 15–16.

- Gori, Maja (November 2012). "Who are the Illyrians? The Use and Abuse of Archaeology in the Construction of National and Trans-National Identities in the Southwestern Balkans". Archaeological review from Cambridge: Archaeology and the (De)Construction of National and Supra-National Polities. 27.2: 71–84.

- Djilas 1991, p. 20.

- Djilas 1991, p. 22.

- Despalatovic 1975.

- Dzino 2014b, p. 9–10.

- ""Illyricvm" smo stvarali 8 godina, a rekonstruirali smo i ilirski jezik". www.vecernji.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 2022-10-16.

Bibliography

- Ammon, Ulrich; Dittmar, Norbert; Mattheier, Klaus J.; Trudgill, Peter (2006), Sociolinguistics: An International Handbook of the Science of Language and Society, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 3-11-018418-4

- Apollodorus; Hard, Robin (1999), The Library of Greek Mythology, Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-283924-1

- Bajrić, Amela (2014). "Illyrian Queen Teuta and the Illyrians in Polybius's passage on the Roman mission in Illyria". Vjesnik Arheološkog muzeja u Zagrebu (in Croatian). 46 (1): 29–56.

- Benać, Alojz (1964). "Vorillyrier, Protoillyrier und Urillyrier". Symposium Sur la Délimitation Territoriale et Chronologique des Illyriens à l'Epoque Préhistorique. Sarajevo: Naučno društvo SR Bosne i Hercegovine: 59–94.

- Boak, Arthur Edward Romilly; Sinnigen, William Gurnee (1977), A History of Rome to A.D. 565, Macmillan, ISBN 9780024108005

- Boardman, John (1982), The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume III, Part I: The Prehistory of the Balkans; the Middle East and the Aegean World, Tenth to Eighth Centuries B.C., Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-22496-9

- Boardman, John; Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1982), The Cambridge Ancient History: The Expansion of the Greek World, Eighth to Six Centuries B.C, Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-23447-6

- Bowden, William (2003), Epirus Vetus: The Archaeology of a Late Antique Province, Duckworth, ISBN 0-7156-3116-0

- Bowden, William (2004). "Balkan Ghosts? Nationalism and the Question of Rural Continuity in Albania". In Christie, Neil (ed.). Landscapes of Change: Rural Evolutions in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1840146172.

- Brandt, J. Rasmus; Ingvaldsen, HÎkon; Prusac, Marina (2014). Death and Changing Rituals: Function and meaning in ancient funerary practices. Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-78297-639-4.

- Budden-Hoskins, Sandy; Malovoz, Andreja; Wu, Mu-Chun; Waldock, Lisa (2022). Mediating Marginality: Mounds, Pots and Performances at the Bronze Age Cemetery of Purić-Ljubanj, Eastern Croatia. Archaeopress. ISBN 978-1-78969-973-9.

- Bunson, Matthew (1995), A Dictionary of the Roman Empire, Oxford University Press US, ISBN 0-19-510233-9

- Cabanes, Pierre (1988). Les illyriens de Bardulis à Genthios (IVe–IIe siècles avant J.-C.) [The Illyrians from Bardylis to Gentius (4th – 2nd century BC)] (in French). Paris: SEDES. ISBN 2718138416.

- Cabanes, Pierre (2002) [1988]. Čutura, Dinko; Kuntić-Makvić, Bruna (eds.). Iliri od Bardileja do Gencia (IV. – II. stoljeće prije Krista) [The Illyrians from Bardylis to Gentius (4th – 2nd century BC)] (in Croatian). Translated by Vesna Lisičić. Svitava. ISBN 953-98832-0-2.

- Castiglioni, Maria Paola (2007). "Genealogical Myth and Political Propaganda in Antiquity: the Re-Use of Greek Myths from Dionysius to Augustus". In Carvalho, Joaquim (ed.). Religion and Power in Europe: Conflict and Convergence. Edizioni Plus. ISBN 978-88-8492-464-3.

- Castiglioni, Maria Paola (2010). Cadmos-serpent en Illyrie: itinéraire d'un héros civilisateur. Edizioni Plus. ISBN 9788884927422.

- Ceka, Neritan (2005), The Illyrians to the Albanians, Publ. House Migjeni, ISBN 99943-672-2-6

- Cambi, Nenad; Čače, Slobodan; Kirigin, Branko, eds. (2002). Greek influence along the East Adriatic Coast. Knjiga Mediterana. Vol. 26. ISBN 9531631549.

- Champion, Craige Brian (2004), Cultural Politics in Polybius's Histories, Berkeley, California: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-23764-1