Elasticity (economics)

In economics, elasticity measures the percentage change of one economic variable in response to a percentage change in another.[1] If the price elasticity of the demand of something is -2, a 10% increase in price causes the demand quantity to fall by 20%.

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

|

|

Introduction

Elasticity is an important concept in neoclassical economic theory, and enables in the understanding of various economic concepts, such as the incidence of indirect taxation, marginal concepts relating to the theory of the firm, distribution of wealth, and different types of goods relating to the theory of consumer choice. An understanding of elasticity is also important when discussing welfare distribution, in particular consumer surplus, producer surplus, or government surplus.

Elasticity is present throughout many economic theories, with the concept of elasticity appearing in several main indicators. These include price elasticity of demand, price elasticity of supply, income elasticity of demand, elasticity of substitution between factors of production, cross-price elasticity of demand, and elasticity of intertemporal substitution.

In differential calculus, elasticity is a tool for measuring the responsiveness of one variable to changes in another causative variable. Elasticity can be quantified as the ratio of the percentage change in one variable to the percentage change in another variable when the latter variable has a causal influence on the former and all other conditions remain the same. For example, the factors that determine consumers' choice of goods mentioned in consumer theory include the price of the goods, the consumer's disposable budget for such goods, and the substitutes of the goods.[2]

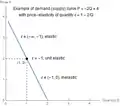

Within microeconomics, elasticity and slope are closely linked. For price elasticity, the relationship between the two variables on the x-axis and y-axis can be obtained by analyzing the linear slope of the demand or supply curve or the tangent to a point on the curve. When the tangent of the straight line or curve is steeper, the price elasticity (demand or supply) is smaller; when the tangent of the straight line or curve is flatter, the price elasticity (demand or supply) is higher.[3]

Elasticity is a unitless ratio, independent of the type of quantities being varied. An elastic variable (with an absolute elasticity value greater than 1) responds more than proportionally to changes in other variables. A unit elastic variable (with an absolute elasticity value equal to 1) responds proportionally to changes in other variables. In contrast, an inelastic variable (with an absolute elasticity value less than 1) changes less than proportionally in response to changes in other variables. A variable can have different values of its elasticity at different starting points. For example, for the suppliers of the goods, the quantity of a good supplied by producers might be elastic at low prices but inelastic at higher prices, so that a rise from an initially low price might bring on a more-than-proportionate increase in quantity supplied. In contrast, a raise from an initially high price might bring on a less-than-proportionate rise in quantity supplied.

In empirical work, an elasticity is the estimated coefficient in a linear regression equation where both the dependent variable and the independent variable are in natural logs. Elasticity is a popular tool among empiricists because it is independent of units and thus simplifies data analysis.

The concept of price elasticity was first cited in an informal form in the book Principles of Economics published by the author Alfred Marshall in 1890.[2] Subsequently, a major study of the price elasticity of supply and the price elasticity of demand for US products was undertaken by Joshua Levy and Trevor Pollock in the late 1960s.[4]

Definition

Elasticity is the measure of the sensitivity of one variable to another. A highly elastic variable will respond more dramatically to changes in the variable it is dependent on. The x-elasticity of y measures the fractional response of y to a fraction change in x, which can be written as

- x-elasticity of y:

In economics, the common elasticities (price-elasticity of demand), price elasticity of supply, and cross-price elasticity) all have the same form:

- P-elasticity of Q: if continuous, or if discrete.

| elastic | Q changes more than P | |

| unit elastic | Q changes like P | |

| inelastic | Q changes less than P |

Suppose price rises by 1%. If the elasticity of supply is 0.5, quantity rises by .5%; if it is 1, quantity rises by 1%; if it is 2, quantity rises by 2%.

Special cases:

- Perfectly elastic: ; quantity has an infinite response to even a small price change.

- Perfectly inelastic: ; quantity does not respond at all to a price change.

Seller revenue (or, alternatively, consumer expenditure) is maximized when (unit elasticity) because at that point a change in price is exactly cancelled by the quantity response, leaving unchanged. To maximize revenue, a firm must:

- Relatively Elastic Demand: increase price if demand is inelastic:

- reduce price if demand is elastic:

The elasticity of demand is different at different points of a demand curve, so for most demand functions, including linear demand, a firm following this advice will find some price at which and further price changes would reduce revenue. (This is not true for some theoretical demand functions: has an elasticity of -.5 for any value of , so revenue rises infinitely as price rises to infinity even though quantity approaches zero. See Isoelastic function.)

perfect Q-inelasticity of P: P is constant as Q changes

perfect Q-inelasticity of P: P is constant as Q changes perfect Q-elasticity of P: P changes while Q = constant

perfect Q-elasticity of P: P changes while Q = constant Conventional demand curve (downwards linear slope), with its elasticity

Conventional demand curve (downwards linear slope), with its elasticity Example of demand curve with constant elasticity

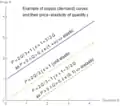

Example of demand curve with constant elasticity Examples of supply curves with different elasticity

Examples of supply curves with different elasticity Examples of a non-linear supply curve with its elasticity

Examples of a non-linear supply curve with its elasticity

Types of Elasticity

Price Elasticity of Demand

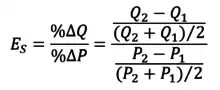

Price Elasticity of Demand measures sensitivity of demand to price. Thus, it measures the percentage change in demand in response to a change in price.[5] More precisely, it gives the percentage change in quantity demanded in response to a one per cent change in price (ceteris paribus, i.e. holding constant all the other determinants of demand, such as income). Expressing this mathematically, price elasticity of demand is calculated by dividing the percentage change in the quantity demanded by the percentage change in the price.[6]

If price elasticity of demand is calculated to be less than 1, the good is said to be inelastic. An inelastic good will respond less than proportionally to a change in price; for example, a price increase of 40% that results in a decrease in demand of 10%. Goods that are inelastic often have at least one of the following characteristics: -Few, if any, available substitutes (eg precious metals) -Essential goods (eg petrol) -Addictive goods (eg alcohol, cigarettes) -Bought infrequently or a small percentage of income (eg salt)

For goods with a high elasticity value, consumers will be more sensitive to price changes. For the average consumer, an increase in price of an inessential good with many available substitutes will often result in that consumer not purchasing the good at all, or purchasing one of the substitutes instead.[7]

Price Elasticity of Supply

The Price Elasticity of Supply measures how the amount of a good that a supplier wishes to supply changes in response to a change in price.[8] In a manner analogous to the price elasticity of demand, it captures the extent of horizontal movement along the supply curve relative to the extent of vertical movement. If supply elasticity is zero, the supply of a good supplied is "totally inelastic", and the quantity supplied is fixed. It is calculated by dividing the percentage change in quantity supplied by the percentage change in price.[9]

Income Elasticity of Demand

Income Elasticity of Demand is a measure used to show the responsiveness of the quantity demanded of a good or service to a change in the consumer income. Mathematically, this is calculated by dividing the percentage change in the quantity demanded by the percentage change in income.[10] Generally, a higher income will increase quantity demanded as consumers will be willing to spend more.

Cross-Price Elasticity of Demand

Cross Price Elasticity of Demand measures the sensitivity between the quantity demanded in one good when there is a change in price in another good.[11] As a common elasticity, it follows a similar formula to Price Elasticity of Demand. Thus, to calculate it the percentage change in the quantity of the first good is divided by the percentage change in price in the second good.[11] The related goods that may be used to determine sensitivity can be complements or substitutes.[5] Finding a high-cross price elasticity between the goods may indicate that they are more likely substitutes and may have similar characteristics.[12] If cross-price elasticity is negative, the goods are likely to be complements.

Real-world examples of cross-price elasticity:[13]

| Product Under Investigation | Comparison Product | Price Elasticity |

| US Domestic Tuna | Imported Tuna | 0.45 |

| US Domestic Tuna | Bread | -0.33 |

| US Domestic Tuna | Ground Meat | 0.3 |

| Beer | Wine | 0.2 |

| Beer | Soft Drinks | 0.3 |

| Transit | Automobiles | 0.85 |

| Transportation | Recreation | -0.05 |

| Food | Recreation | 0.15 |

| Clothing | Food | -0.18 |

Elasticity of Scale

Elasticity of scale or output elasticity measures the percentage change in output induced by a collective percent change in the usages of all inputs.[14] A production function or process is said to exhibit constant returns to scale if a percentage change in inputs results in an equal percentage in outputs (an elasticity equal to 1). It exhibits increasing returns to scale if a percentage change in inputs results in greater percentage change in output (an elasticity greater than 1). The definition of decreasing returns to scale is analogous.[15][16][17][18]

%252C_Prometheus_Books.JPG.webp)

Determinants of Elasticity

There are various factors that may affect elasticity, and these factors differ for the types of elasticity.

Factors Affecting Price Elasticity of Demand

If a product has various available substitutes that exist in the market, it is likely that it would be elastic.[19] If a product has a competitive product at a cheaper price in the market in which it shares many characteristics with, it is likely that consumers would deviate to the cheaper substitute. Thus, if many substitutions existed in the market, a consumer would have more choices and the elasticity of demand would be higher (elastic). In contrast, if there were few substitutions that existed in the market, consumers will have fewer choices and little to no available substitutes which means elasticity of demand would be lower (inelastic).[19]

If a product is a necessity to the survival or daily life of a consumer, it is likely to be inelastic.[20] This is due to the fact that if a product is so intrinsically important to the daily life of a consumer, a change in price is not likely to affect its demand.[1]

If the price of a product is increasing and it has little available substitutes, it is likely that the consumer will still continue to pay this higher price.[1] The fact that the consumer needs the good in the short-run, means that he is likely to continue this action regardless in the long-run. This shows inelasticity of demand, because even if there is a huge increase of a product's price, there is no reduction of demand. However, if the consumer could not afford the new price of the product, they would likely have to learn to live without it, making the price elastic in the long-run.[19]

Alternatively, we may also determine the factors affecting demand elasticity by considering three “Intuitive factors. Firstly, we may consider that there is different nature of elasticity when weighting a “brand” of a product or a “category” of a product, a particular brand of product is subject to elasticity as other brand may replace it, while a “category” of a product may not be easily replaced by other category of products. Secondly, like a complementary product, there are some commodities that is inelastic as buyer may have proceeding commitment to purchase it in the future, such as vehicle spare part. Thirdly, consumer mostly pay attention to product which cost a majority of share of their spending, hence any change of price in this product or services would be immediately affect consumer demand, hence this kind of product is elastic, while a product which is not part of consumer majority of purchase is inelastic due to “low involvement to products” effect.[21]

Factors Affecting Price Elasticity of Supply

Like Price Elasticity of Demand, time also affects Price Elasticity of Supply. Though, there are other varying factors that affect this too, such as: capacity, availability of raw materials, flexibility, and the number of competitors in the market. Though, the time horizon is arguably the most influential detriment to price elasticity of supply.[9]

The longer the time horizon, the easier it is for commodity buyers to choose alternative products (substitutes). Further, as the time for suppliers to respond to price changes increases, a given price change will have a more significant impact on supply. However, suppliers can also hire more labour overtime, raise more funds, build more new factories to expand production capacity, and ultimately increase supply. In general, long-term supply is more elastic than short-term supply because producers need some time to adjust their ability to adapt to changes in demand.[22]

Applications

The concept of elasticity has an extensive range of applications in economics. In particular, an understanding of elasticity is fundamental in understanding the response of supply and demand in a market.[6]

Elasticity is also an important concept for enterprises and governments. For enterprises, elasticity is relevant in the calculation of the fluctuation of commodity prices, and its relation to income.

For enterprise, the concept of elasticity also can be applied for pricing strategy. At one hand a businessman has to calculate as if reducing price will necessarily increasing the demand of their products, or will it not be necessary so and resolving a lost for the company[23] At the other hand, enterprise have to consider whether Increasing price and cutting production quantity led to greater revenue.[24] To answer that, it is suggested that if the demand of that product is elastic enough, it is profitable for enterprises to cut price and let the demand to increase over time.[25] But in other hand if the price is inelastic, it is profitable to cut the quantity of production and let the price to rise, because as the product is inelastic enough, so consumer have no alternative to purchase other type of product or services to replace it. Though it is clear that the enterprise should not let their product price to pass by that inelasticity threshold, if so, then the product will be subject to price elasticity and be affected by declining demand over time.[24]

For governments, the concept is important for the implementation of taxation. When a government wants to increase taxes on goods, it can use elasticity to judge whether increasing the tax rate will be beneficial. Often, the demand for goods will be significantly reduced when a government increases taxes on them. Whilst a tax increase on inelastic goods will not impact their demand, it may affect goods that are elastic. Aside from taxation, elasticity can also assist in analysing the need for government intervention.

Additionally, for essential goods, the government must ensure that they are available to most consumers. Through setting price ceilings and floors, the government is intervening by ensuring that these goods are reasonably available.

As stated by British political economist David Ricardo, luxury goods taxes have certain advantages over necessities taxes. They are usually paid from income and, therefore, will not reduce the country's production capital. For instance, when the price of wine products rises due to increased taxes, consumers can give up drinking wine.[26]

Other common uses of elasticity include:

- Analysis of incidence of the tax burden and other government policies. See Tax incidence.

- Income elasticity of demand, used as an indicator of industry health, future consumption patterns, and a guide to firms' investment decisions. See Income elasticity of demand.

- Effect of international trade and terms of trade effects. See Marshall–Lerner condition and Singer–Prebisch thesis.

- Analysis of consumption and saving behavior. See Permanent income hypothesis.

- Analysis of advertising on consumer demand for particular goods. See Advertising elasticity of demand.

Variants

In some cases the discrete (non-infinitesimal) arc elasticity is used instead. In other cases, such as modified duration in bond trading, a percentage change in output is divided by a unit (not percentage) change in input, yielding a semi-elasticity instead.

See also

- Arc elasticity

- Elasticity of a function

References

- Hayes, Adam. "Learn About Elasticity". Investopedia. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- L.F.G., López (Apr–Jun 2019). "The concept of elasticity and strategies for teaching it in introductory courses of economics". Semestre Económico. 22 (51): 149–167. doi:10.22395/seec.v22n51a7.

- Chen, Xudong (October 1, 2017). "Elasticity as Relative Slopes: A Graphical Approach to Linking the Concepts of Elasticity and Slope". The American Economist. 62 (2): 258–267. doi:10.1177/0569434516682713. S2CID 157222255.

- Taylor, Lester D.; Houthakker, H.S. (2010). Consumer demand in the United States : prices, income, and consumption behavior (Originally published by Harvard University Press, 2005) (3rd ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-1-4419-0510-9.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - Webster, Thomas, J. (2015). Managerial Economics: Tools for Analysing Business Strategy. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. pp. 55, 70. ISBN 978-1-4985-0794-3.

- Layton, Allan; Robinson, Tim; Tucker, Irvin, B. (2016). Economics for Today. South Melbourne, Victoria: Cengage Learning Australia Pty Ltd. p. 105.

- "Elasticity | economics | Britannica".

- Perloff, J. (2008). p.36.

- Gans, Joshua; King, Stephen; Mankiw, Gregory, N. (2017). Principles Of Microeconomics. South Melbourne, Victoria: Cengage Learning. pp. 108–116. ISBN 978-0-17-028246-8.

- Gans, Joshua; King, Stephen; Mankiw, Gregory, N. (2017). Principles of Microeconomics. South Melbourne, Victoria: Cengage Learning. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-17-028246-8.

- Hayes, Adam. "Understanding the Cross Elasticity of Demand". Investopedia. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- Kolay, Sreya; Tyagi, Rajeev, K. (2018). "Product Similarity and Cross-Price Elasticity". Review of Industrial Organization. 52: 85–100. doi:10.1007/s11151-017-9578-8. S2CID 157974644 – via Springer Link.

- MOTTA, DOBRESCU (March 2019). PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS (FOURTH ed.). LIONSHEART STUDIOS. pp. 64–80.

- Varian (1992). pp.16–17.

- Samuelson, W. & Marks, S. (2003). p.233.

- Hanoch, G. (1975). "The Elasticity of Scale and the Shape of Average Costs". American Economic Review. 65 (3): 492–497. JSTOR 1804855.

- Panzar, J. C.; Willig, R. D. (1977). "Economies of Scale in Multi-Output Production". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 91 (3): 481–493. doi:10.2307/1885979. JSTOR 1885979.

- Zelenyuk, V. (2013). "A scale elasticity measure for directional distance function and its dual: Theory and DEA estimation". European Journal of Operational Research. 228 (3): 592–600. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2013.01.012.

- Ravelojaona, Paola (2019). "On constant elasticity of substitution – Constant elasticity of transformation Directional Distance Functions". European Journal of Operational Research. 272 (2): 780–791. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2018.07.020. S2CID 52900747.

- Dholakia, R.H., 2016. Demand elasticities for pulses and public policy options, London: Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad.

- Png, Ivan (30 June 2012). Managerial Economics (4 ed.). Routledge. p. 41. doi:10.4324/9780203116098. ISBN 978-0-203-11609-8.

- Galchynskyi, Leonid (2020-06-24). "Estimation of the price elasticity of petroleum products' consumption in Ukraine". Equilibrium (Toruń ). 15 (2): 315–339. doi:10.24136/eq.2020.015.

- Mithani, D (2009). Introductory Managerial Economics. Global Media, Mumbai. pp. 108–109.

- Png, Ivan (30 June 2012). Managerial Economics (4 ed.). Routledge. pp. 43–44. doi:10.4324/9780203116098. ISBN 978-0-203-11609-8.

- Mithani, D (2009). Introductory Managerial Economics. Mumbai: Global Media. pp. 108–109.

- Maneschi, Andrea (2004). "The true meaning of David Ricardo's four magic numbers". Journal of International Economics. 62 (2): 433–443. doi:10.1016/S0022-1996(03)00008-4.

Further reading

- Lovell, Michael C. (2004). Economics with Calculus. Hackensack: World Scientific. pp. 75–85. ISBN 981-238-857-5.

- Varian, Hal (1994). "Market Demand". Intermediate Microeconomics : A Modern Approach. New York: W.W. Norton. pp. 261–280. ISBN 0-393-96320-9.

External links

- Economics Basics: Elasticity from Investopedia.com. Accessed February 29, 2008.

- Revenue and Elasticity and Elasticity, Total Revenue, and the Linear Demand Curve by Fiona Maclachlan, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.