Ine of Wessex

Ine, also rendered Ini or Ina, (Latin: Inus; c. AD 670 – after 726) was King of Wessex from 689[1] to 726. At Ine's accession, his kingdom dominated much of southern England. However, he was unable to retain the territorial gains of his predecessor, Cædwalla, who had expanded West Saxon territory substantially. By the end of Ine's reign, the kingdoms of Kent, Sussex, and Essex were no longer under West Saxon sway; however, Ine maintained control of what is now Hampshire, and consolidated and extended Wessex's territory in the western peninsula.

| Ine | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) King Ine depicted in the Transfiguration Window of Wells Cathedral. | |

| King of Wessex | |

| Reign | 689–726 |

| Predecessor | Cædwalla |

| Successor | Æthelheard |

| Born | c. 670 |

| Died | After 726 Rome |

| Consort | Æthelburg of Wessex |

| House | Wessex |

| Father | Cenred |

Ine is noted for his code of laws (Ines asetnessa or "laws of Ine"), which he issued in about 694. These laws were the first issued by an Anglo-Saxon king outside Kent. They shed much light on the history of Anglo-Saxon society, and reveal Ine's Christian convictions. Trade increased significantly during Ine's reign, with the town of Hamwic (now Southampton) becoming prominent. It was probably during Ine's reign that the West Saxons began to mint coins, though none have been found that bear his name.

Ine abdicated in 726 to go to Rome, leaving, in the words of the contemporary chronicler Bede, the kingdom to "younger men". He was succeeded by Æthelheard.

Genealogy and accession

Early sources agree that Ine was the son of Cenred, and that Cenred was the son of Ceolwald; further back there is less agreement.[2] Ine was born around 670[3] and his siblings included a brother, Ingild, and two sisters, Cuthburh and Cwenburg. Ingild is given by the Anglo-Saxon royal genealogies as ancestor of king Egbert of Wessex and the subsequent kings of England.[4] Cuthburh was married to King Aldfrith of Northumbria,[5] and Ine himself was married to Æthelburg.[2] Bede tells that Ine was "of the blood royal", by which he means the royal line of the Gewisse, the early West Saxon tribal name.[6]

The genealogy of Ine and of the kings of Wessex is known from two sources: the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and the West Saxon Genealogical Regnal List. The Chronicle was created in the late 9th century, probably at the court of Alfred the Great, and some of its annals incorporated short genealogies of kings of Wessex. These are often at variance with the more extensive information in the Regnal List.[7] The inconsistencies appear to result from the efforts of later chroniclers to demonstrate that each king on the list was descended from Cerdic, the founder, according to the Chronicle, of the West Saxon line in England.[8]

Ine's predecessor on the throne of Wessex was Cædwalla, but there is some uncertainty about the transition from Cædwalla to Ine. Cædwalla abdicated in 688 and departed for Rome to be baptized. According to the West Saxon Genealogical Regnal List, Ine reigned for 37 years, abdicating in 726. These dates imply that he did not gain the throne until 689, which could indicate an unsettled period between Cædwalla's abdication and Ine's accession. Ine may have ruled alongside his father, Cenred, for a period: there is weak evidence for joint kingships, and stronger evidence of subkings reigning under a dominant ruler in Wessex, not long before this time.[9] Ine acknowledges his father's help in his code of laws,[10] and there is also a surviving land-grant that indicates Cenred was still reigning in Wessex after Ine's accession.[11][12]

Reign

The extent of West Saxon territory at the start of Ine's reign is fairly well known. The upper Thames valley on both sides of the river had long been the territory of the Gewisse, though Cædwalla had lost territory north of the river to the kingdom of Mercia before Ine's accession. To the west, Ceawlin of Wessex is known to have reached the Bristol Channel one hundred years before.[13] The West Saxons had since expanded further down the southwestern peninsula, pushing back the boundary with the British kingdom of Dumnonia, which was probably roughly equivalent to modern Devon and Cornwall.[14] On the West Saxons' eastern border was the kingdom of the East Saxons, which included London and what is now Surrey. To the southeast were the South Saxons, on the coast east of the Isle of Wight. Beyond Sussex lay the kingdom of Kent.[15] Ine's predecessor, Cædwalla, had made himself overlord of most of these southern kingdoms,[16] though he had not been able to prevent Mercian inroads along the upper Thames.[14]

Ine retained control of the Isle of Wight, and made further advances in Dumnonia, but the territorial gains Cædwalla had made in Sussex, Surrey and Kent were all lost by the end of Ine's reign.[14]

Kent, Essex, Sussex, and Surrey

Ine made peace with Kent in 694, when its king Wihtred gave Ine a substantial sum in compensation for the death of Cædwalla's brother Mul, who had been killed during a Kentish rebellion in 687. The value of the amount offered to Ine by Wihtred is uncertain; most manuscripts of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle record "thirty thousand", and some specify thirty thousand pounds. If the pounds are equal to sceattas, then this amount is the equal of a king's weregild—that is, the legal valuation of a man's life, according to his rank.[17][18]

Ine kept the South Saxons, who had been conquered by Cædwalla in 686, in subjugation for a period.[19] King Nothhelm of Sussex is referred to in a charter of 692 as a kinsman of Ine (perhaps by marriage).[11][20] Sussex was still under West Saxon domination in 710, when Nothhelm is recorded as having campaigned with Ine in the west against Dumnonia.[14]

Control of Surrey, which may never have been an independent kingdom, passed between Kent, Mercia, Essex, and Wessex in the years before Ine's reign. Essex also included London, and the diocese of London included Surrey; this appears to have been a source of friction between Ine and the East Saxon and Mercian kings, until the province was transferred to the diocese of Winchester in 705.[21] Evidence for Ine's early control of Surrey comes from the introduction to his laws, in which he refers to Eorcenwald, bishop of London, as "my bishop".[14][22] Ine's subsequent relations with the East Saxons are illuminated by a letter written in 704 or 705 by Bishop Wealdhere of London to Brihtwold, the Archbishop of Canterbury. The letter refers to "disputes and discords" that had arisen "between the king of the West Saxons and the rulers of our country". The rulers that Wealdhere refers to are Sigeheard and Swæfred of the East Saxons, and the cause of the discord was the East Saxons' sheltering of exiles from the West Saxons. Ine had agreed to peace on the condition that the exiles were expelled. A council at Brentford was planned to resolve the disputes.[20][23] By this point Surrey had clearly passed out of West Saxon control.[20]

Bede records that Ine held Sussex in subjection for "several years",[24] but in 722 an exile named Ealdbert fled to Surrey and Sussex, and Ine invaded Sussex as a result. Three years later Ine invaded again, this time killing Ealdberht. Sussex had evidently broken away from West Saxon domination some time before this.[2][14] It has been suggested that Ealdberht was a son of Ine, or a son of Ine's brother Ingild.[25]

Dumnonia and Mercia

In 710, Ine and Nothhelm fought against Geraint of Dumnonia, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle;[2] John of Worcester states that Geraint was killed in this battle.[26] It has traditionally been thought that Ine's advance brought him control of what is now Devon, the new border with Dumnonia being the river Tamar.[20] However, this does not match with subsequent events such as the Battle of Hehil or Athelstan driving the Britons from Isca (Exeter). The Annales Cambriae, a 10th-century chronicle,[27] records that in 722 the British defeated their enemies at the Battle of Hehil. The "enemies" must be Ine or his people, but the location is unidentified; historians have suggested locations in both Cornwall and Devon.[14][28]

Ine fought a battle at Woden's Barrow in 715, either against the Mercians under Ceolred or together with them against an unnamed opponent; the result is not recorded. Woden's Barrow is a tumulus, now called Adam's Grave, at Alton Prior, Wiltshire.[29] Ine may not have recovered any of the lands north of the Thames that had belonged to the West Saxons under previous kings, but it is known that he controlled the southern bank: a charter dated 687 shows him giving land to the church at Streatley on the Thames and at nearby Basildon.[14][30]

Other conflicts

In 721, the Chronicle records that Ine slew one Cynewulf, of whom nothing else is known, though his name suggests a connection to the Wessex royal line. A quarrel apparently arose in the royal family soon afterwards: in 722, according to the Chronicle, Ine's queen Æthelburg destroyed Taunton, which her husband had built earlier in his reign,[2] around 710.

Internal affairs

The first mention of the office of ealdorman in Wessex, and the first references to the shires they led, occur during Ine's reign. It may have been Ine who divided Wessex into something approximating the modern counties of Hampshire, Wiltshire, Somerset, Devon, and Dorset, though earlier administrative boundaries might also have influenced these borders.[19] It has also been suggested that these counties began as divisions of the kingdom among members of the royal family.[9]

By about 710, in the middle of Ine's reign, the trading settlement of Hamwic had become established on the west bank of the river Itchen; the site is now part of the modern city of Southampton. The goods traded at this port included glass vessels, and finds of animal bones suggest an active trade in hides. Further evidence of trade comes from finds of imported goods such as quernstones, whetstones, and pottery; and finds of sceattas from the town include Frisian coins. Specialist trades carried on in the town included cloth-making, smithying, and metalworking. It is not known whether Ine took an interest in Hamwic, but some of the goods he favoured, including luxuries, were imported there, and the merchants would probably have needed royal protection. The total population of Hamwic has been estimated at 5,000, and this high population itself implies Ine's involvement, since no-one but the king would have been able to arrange to feed and house such a large group of people.[31][32]

The growth of trade after about 700 was paralleled by an expansion of the area of circulation of the sceat, the common coin of the day, to include the upper Thames valley.[20] It is thought that the first West Saxon coinage was minted during Ine's reign, though no coins bearing his name have been found—sceattas typically gave no hint of the reigning king.[19]

Laws

The earliest Anglo-Saxon law code to survive, which may date from 602 or 603, is that of Æthelberht of Kent, whose reign ended in 616.[33][34] In the 670s or 680s, a code was issued in the names of Hlothhere and Eadric of Kent.[35] The next kings to issue laws were Wihtred of Kent and Ine.[36][37]

The dates of Wihtred's and Ine's laws are somewhat uncertain, but there is reason to believe that Wihtred's laws were issued on 6 September 695,[38] while Ine's laws were written in 694 or shortly before.[14] Ine had recently agreed peaceful terms with Wihtred over compensation for the death of Mul, and there are indications that the two rulers collaborated to some degree in producing their laws. In addition to the coincidence of timing, there is one clause that appears in almost identical form in both codes.[39] Another sign of collaboration is that Wihtred's laws use gesith, a West Saxon term for noble, in place of the Kentish term eorlcund. It is possible that Ine and Wihtred issued the law codes as an act of prestige, to re-establish authority after periods of disruption in both kingdoms.[20]

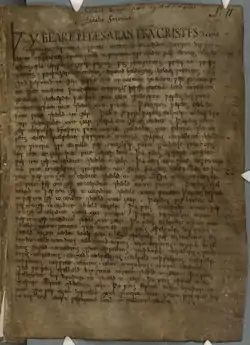

Ine's laws survive only because Alfred the Great appended them to his own code of laws.[40] The oldest surviving manuscript, and only complete copy, is in Corpus Christi College, Cambridge MS 173, which contains both Alfred's and Ine's law codes and the oldest extant text of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Two more partial texts survive. One was originally a complete copy of Ine's laws, part of British Library MS Cotton Otho B xi, but that manuscript was largely destroyed in 1731 by a fire at Ashburnham House in which only Chapters 66 to 76.2 of Ine's laws escaped destruction. A fragment of Ine's laws can also be found in British Museum MS Burney 277.[36]

It is possible that we do not have Ine's laws in their original 7th-century form. Alfred mentions in the prologue to his laws that he rejected earlier laws which he disliked. He did not specify what laws he omitted, but if they were the ones no longer relevant in his own time, it cannot be assumed that the surviving version of Ine's laws is complete.[36]

The prologue to Ine's laws lists his advisors. Three people are named: bishops Eorcenwald and Hædde, and Ine's father, King Cenred. Ine was a Christian king, whose intent to encourage Christianity is clear from the laws. The oath of a communicant, for example, is declared to carry more weight than that of a non-Christian;[36] and baptism and religious observance are also addressed. Significant attention is also paid to civil issues—more than in the contemporary Kentish laws.[41]

One of the laws states that common land might be enclosed by several ceorls (the contemporary name for Saxon freemen). Any ceorl who fails to fence his share, however, and allows his cattle to stray into someone else's field is to be held liable for any damage caused.[40] This does not mean that the land was held in common: each ceorl had his own strip of land that supported him. It is notable that a king's law is required to settle a relatively minor issue; the laws do not mention the role of local lords in obtaining compliance from the ceorls.[42] It is clear from this and other laws that tenants held the land in tenure from a lord; the king's close involvement indicates that the relationship between lord and tenant was under the king's control.[43]

The laws that deal with straying cattle provide the earliest documentary evidence for an open-field farming system. They show that open-field agriculture was practiced in Wessex in Ine's time, and it is probable that this was also the prevalent agricultural method throughout the English midlands, and as far north and east as Lindsey and Deira. Not all of Wessex used this system, however: it was not used in Devon, for example.[42] The law which mentions a "yard" of land is the first documented mention of that unit. A yard was a unit of land equal to a quarter of a hide; a hide was variable from place to place but could be as much as 120 acres (49 ha). The yard in this sense later became the standard holding of the medieval villein, and was known as the virgate. One historian has commented that "the beginnings of a manorial economy are clearly visible in Ine's laws."[43]

The fine for neglecting fyrd, the obligation to do military service for the king, is set at 120 shillings for a nobleman, and 30 shillings for a ceorl,[40] incidentally revealing that ceorls were required to serve in the army. Scholars have disagreed on the military value of the ceorl, but it is not surprising that all free men would fight, since defeat might have meant slavery.[44]

Another law specified that anyone accused of murder required at least one high-ranking person among his "oath-helpers". An oath-helper would swear an oath on behalf of an accused man, to clear him from the suspicion of the crime. Ine's requirement implies that he did not trust an oath sworn only by peasants. It may represent a significant change from an earlier time when a man's kin were expected to support him with oaths.[45]

The laws made separate provision for Ine's English and British subjects, favouring the former over the latter; the weregilds paid for Britons were half of those paid for Saxons of the same social class, and their oaths also counted for less.[46] The evidence they provide for the incomplete integration of the two populations is supported by research into placename history, the history of religious houses, and local archaeology, which indicates that the western part of Wessex was thinly settled by the Germanic newcomers at the time the laws were issued.[16] It is notable that, although issued by the Saxon king of a Saxon kingdom, the term used in the laws to define Ine's Germanic subjects is Englisc. This reflects the existence, even at this early date, of a common English identity encompassing all the Germanic peoples of Britain.[47]

Christianity

Ine was a Christian king, who ruled as a patron and protector of the church. The introduction to his laws names his advisors, among whom are Eorcenwald, Bishop of London and Hædde, Bishop of Winchester; Ine says that the laws were also made with the advice and instruction of "all my ealdormen, and chief councillors of my people, and also a great assembly of the servants of God".[22][48] The laws themselves demonstrate Ine's Christian convictions, specifying fines for failing to baptize infants or to tithe.[19] Ine supported the church by patronising religious houses, especially in the new diocese of Sherborne,[19] which had been divided from the diocese of Winchester in 705. Ine had opposed this division, ignoring threats of excommunication from Canterbury, but he agreed to it when Bishop Haedde died.[20]

The first West Saxon nunneries were founded in Ine's reign by Ine's kinswoman, Bugga, the daughter of King Centwine, and by Ine's sister Cuthburh, who founded the abbey of Wimborne at some point after she separated from her husband, King Aldfrith of Northumbria.[32][49] At the bishop Aldhelm's suggestion in 705, Ine built the church which later became Wells Cathedral,[50] and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle also records that Ine built a minster at Glastonbury. This must refer to additional building or re-building since there was already a British monastery at Glastonbury.[51]

Ine has been credited with supporting the establishment of an organized church in Wessex, though it is not clear that this was his initiative. He is also connected with the oldest known West Saxon synods, presiding at one himself and apparently addressing the assembled clerics.[52]

There is a tradition that Ine was a saint, and was the dedicatee of St Ina's Church in Llanina near New Quay, Wales. However, a more likely dedicatee for this church is the fifth-century Welsh Saint Ina.[53][54]

Abdication, succession and life in Rome

In 726, Ine abdicated, with no obvious heir and, according to Bede, left his kingdom to "younger men" in order to travel, with his wife Æthelburg, to Rome where they both died; his predecessor, Cædwalla, had also abdicated to go to Rome and was baptized there by the pope. A pilgrimage to Rome was thought to aid one's chance of a welcome in heaven, and according to Bede, many people went to Rome at this time for this reason: "... both noble and simple, layfolk and clergy, men and women alike."[6] Either Ine or Offa of Mercia is traditionally supposed to have founded the Schola Saxonum there, in what is today the Roman rione, or district, of Borgo. The Schola Saxonum took its name from the militias of Saxons who served in Rome, but it eventually developed into a hostelry for English visitors to the city.[55] According to Roger of Wendover, Ine founded the Schola Saxonum in 727.[56]

Ine's successor was King Æthelheard; it is not known whether Æthelheard was related to Ine, though some later sources state that Æthelheard was Ine's brother-in-law.[57] Æthelheard's succession to the throne was disputed by an ætheling, Oswald, and it may be that Mercian support for Æthelheard in the unsettled aftermath of Ine's abdication both helped establish Æthelheard as king and also brought him into the sphere of influence of Æthelbald, the king of Mercia.[2][25]

See also

- House of Wessex family tree

Notes

- Dugdale, William (1693). Monasticon Anglicanum, or, The history of the ancient abbies, and other monasteries, hospitals, cathedral and collegiate churches in England and Wales. With divers French, Irish, and Scotch monasteries formerly relating to England. Abridged Version. Translated by Wright, James. Sam Keble. pp. 3.

- Swanton, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, pp. 42–43.

- Panton, James (24 February 2011). Historical Dictionary of the British Monarchy. Scarecrow Press. p. 108. ISBN 9780810874978.

- Garmonsway, G.N. ed., The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, London, J. M. Dent & Sons, Ltd., pp. xxxii,2,4,42,66

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 143.

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History, quoted from Leo Sherley-Price's translation, p. 276.

- For a discussion of the Chronicle and Regnal List see Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, pp. 128–129. For a recent translation of both sources, see Swanton, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, pp. 2, 40–41.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, pp. 142–143.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p.145–146

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 122.

- "Anglo-Saxons.net S 1164". Retrieved 4 July 2007.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 120.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 29.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, pp. 72–73.

- Blair, Roman Britain, p. 209.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, pp. 137–138.

- Swanton, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 40–41, note 3.

- Lapidge, Michael (ed.), "Wergild", in The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England, p. 469.

- Lapidge, Michael (ed.), "Ine", in The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England, p. 251.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 125–126.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 49.

- Eorcenwald 1 at Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England. Retrieved 17 July 2007. See under "Event" and "Law-making/legislation"

- A translation of Wealdhere's letter can be found in Whitelock, English Historical Documents, p. 729.

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History, quoted from Leo Sherley-Price's translation, p. 230.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 131 & note 75.

- John of Worcester was a 12th-century chronicler who had access to versions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle that have not survived to the present day. See Campbell (ed.), The Anglo-Saxons, p. 222. For the chronicle text, see Forester, Chronicle, p. 36.

- Higham, King Arthur, p. 170.

- Todd & Fleming, The Southwest, p. 273.

- Swanton, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, p. 14.

- "Anglo-Saxons.net: S 239". Retrieved 19 July 2007.

- Campbell (ed.), The Anglo-Saxons, p. 102.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, pp. 139–140.

- Whitelock, English Historical Documents, p. 357.

- Attenborough. The laws of the earliest English kings. pp. 4–17

- Attenborough. The laws of the earliest English kings. pp. 18–23

- Whitelock, English Historical Documents, pp. 327–337.

- Attenborough. The laws of the earliest English kings. pp. 24–61

- Whitelock, English Historical Documents, p. 361.

- The law is chapter 20 in Ine's code, and chapter 28 in Wihtred's. Ine's version reads "If a man from a distance or a foreigner goes through the wood off the track, and does not shout nor blow a horn, he is to be assumed to be a thief, to be either killed or redeemed." Wihtred's version is "If a man from a distance or a foreigner goes off the track, and he neither shouts nor blows a horn, he is to be assumed to be a thief, to be either killed or redeemed." See Whitelock, English Historical Documents, pp. 364, 366.

- Whitelock, English Historical Documents, pp. 364–372.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 124.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, pp. 279–280.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, pp. 312–314.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 290.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, pp. 316–317.

- Yorke, Barbara. 1995. Wessex in the Early Middle Ages. P.72.

- Patrick Wormald, "Bede, the Bretwaldas and the origins of the Gens Anglorum", in Patrick Wormald, The Times of Bede – studies in early English Christian society and its historian (Oxford 2006), pp. 106–34 at p. 119

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 2.

- Lapidge, Michael (ed.), "Cuthburg", in The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England, p. 133.

- "Wells Cathedral". Britania. Archived from the original on 4 July 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- Swanton, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, p. 40, note 1.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 71.

- Baring-Gould, Sabine (1911). Lives of the British Saints. p. 318. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- "Saint Ina of Wessex". CatholicSaints.Info. 23 August 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- Keynes & Lapidge, Alfred the Great, p. 244.

- Reader, Rebecca (1994). "Chapter Three: Matthew Paris and Offa of Mercia". Matthew Paris and Anglo-Saxon England: a thirteenth-century vision of the distant past (PhD). Durham University. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 147. The relationship is recorded in a forged charter: "Anglo-Saxons.net S 250". Retrieved 15 August 2007.

References

- Primary sources

- Attenborough, F.L. Tr., ed. (1922). The laws of the earliest English kings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780404565459. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- Bede (1991). D.H. Farmer (ed.). Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Translated by Leo Sherley-Price. Revised by R. E. Latham. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-044565-X.

- Swanton, Michael (1996). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92129-5.

- Secondary sources

- Campbell, James; John, Eric; Wormald, Patrick (1991). The Anglo-Saxons. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-014395-5.

- Forester, Thomas (1854). The Chronicle of Florence of Worcester. London: Henry G. Bohn. OCLC 59447738.

- Higham, Nicholas J. (2002). King Arthur:Myth-making and History. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-21305-3.

- Hunter Blair, Peter (1966). Roman Britain and Early England: 55 B.C. – A.D. 871. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-00361-2.

- Keynes, Simon; Lapidge, Michael (2004). Alfred the Great: Asser's Life of King Alfred and other contemporary sources. Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044409-2.

- Kirby, D.P. (1992). The Earliest English Kings. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-09086-5.

- Lapidge, Michael (1999). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

- Stenton, Frank M. (1971). Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-821716-1.

- Todd, Malcolm; Fleming, Andrew (1987). The South West to AD 1000. London: Longman. ISBN 0-582-49273-4.

- Whitelock, Dorothy (1968). English Historical Documents v.l. c.500–1042. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode.

- Yorke, Barbara (1990). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. London: Seaby. ISBN 1-85264-027-8.

External links

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Ine". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- Ine 1 at Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England