Italian front (World War I)

The Italian front or Alpine front (Italian: Fronte alpino, "Alpine front"; in German: Gebirgskrieg, "Mountain war") involved a series of battles at the border between Austria-Hungary and Italy, fought between 1915 and 1918 in the course of World War I. Following secret promises made by the Allies in the 1915 Treaty of London, Italy entered the war aiming to annex the Austrian Littoral, northern Dalmatia, and the territories of present-day Trentino and South Tyrol. Although Italy had hoped to gain the territories with a surprise offensive, the front soon bogged down into trench warfare, similar to that on the Western Front in France, but at high altitudes and with very cold winters. Being the largest and most lethal offensive during the WW1, the effects of the Russian Brusilov offensive were far reaching, it helped to relieve the German pressure on Battle of Verdun, also helped to relieve the Austro-Hungarian pressure on the Italians, as a result the Austro-Hungarian Armed forces were fatally weakened in such a degree that Austria-Hungary was unable to conduct a major military operation without German help, finally Romania decided to enter the war on the side of the Allied Forces, however the Russian human and material losses also greatly contributed to the Russian revolutions.[8] Fighting along the front displaced much of the local population, and several thousand civilians died from malnutrition and illness in Italian and Austro-Hungarian refugee-camps.[9] The Allied victory at Vittorio Veneto, the disintegration of the Habsburg empire, and the Italian capture of Trento and Trieste ended the military operations in November 1918. The armistice of Villa Giusti entered into force on 4 November 1918, while Austria-Hungary no longer existed as a unified entity. Italy also refers to the Great War as the Fourth Italian War of Independence, which completed the last stage of Italian unification.[10]

| Italian front | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the European theatre of World War I | |||||||

.jpg.webp) From left to right: Ortler, autumn 1917; Fort Verena, June 1915; Paternkofel, 1915; Carso, 1917; Toblach Airport, 1915. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1915 – up to 58 divisions 1917 – 3 divisions 1918 – 2 divisions 1918 – 5 regiments 1918 – 3 regiments 1918 – 1 regiment |

1915 – up to 61 divisions 1917 – 5 divisions | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Total: ~2,160,000 casualties |

Total: 2,330,000+ casualties | ||||||

| 589,000 Italian civilians died of war-related causes | |||||||

History

Pre-war period

While being a member of the Triple Alliance which consisted of Italy, Austria-Hungary and Germany, Italy did not declare war in August 1914, arguing that the Triple Alliance was defensive in nature and therefore Austria-Hungary's aggression did not oblige Italy to take part.[11] Moreover, Austria-Hungary omitted to consult Italy before sending the ultimatum to Serbia and refused to discuss compensation due according to article 7 of the Alliance.[12] Italy had a longstanding rivalry with Austria-Hungary, dating back to the Congress of Vienna in 1815 after the Napoleonic Wars, which granted several regions on the Italian peninsula to the Austrian Empire.[11]

More importantly, a radical nationalist political movement, called Unredeemed Italy (Italia irredenta), founded in the 1880s, started claiming the Italian-inhabited territories of Austria-Hungary, especially in the Austrian Littoral and in the County of Tyrol. By the 1910s, the expansionist ideas of this movement were taken up by a significant part of the Italian political elite. The annexation of those Austro-Hungarian territories that were inhabited by Italians became the main Italian war goal, assuming a similar function to the issue of Alsace-Lorraine for the French.[11] However, of around 1.5 million people living in those areas, 45% were Italian speakers, while the rest were Slovenes, Germans and Croats. In northern Dalmatia, which was also among the Italian war aims, the Italian-speaking population was only around 5%.

In the early stages of the war, Allied diplomats secretly courted Italy, attempting to secure Italian participation on the Allied side. Set up between the British Foreign Secretary Edward Grey, the Italian Foreign Minister Sidney Sonnino and the French Foreign Minister Jules Cambon, Italy's entry was finally engineered by the Treaty of London of 26 April 1915, in which Italy renounced her obligations to the Triple Alliance.[13]

On February 16, 1915, despite concurrent negotiations with Austria, a courier was dispatched in great secrecy to London with the suggestion that Italy was open to a good offer from the Entente. [ ...] The final choice was aided by the arrival of news in March of Russian victories in the Carpathians. Salandra began to think that victory for the Entente was in sight, and was so anxious not to arrive too late for a share in the profits that he instructed his envoy in London to drop some demands and reach agreement quickly. [...] The Treaty of London was concluded on April 26 binding Italy to fight within one month. [...] Not until May 4 did Salandra denounce the Triple Alliance in a private note to its signatories.[14]

On 23 May, Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary.[13]

Campaigns of 1915–1916

During the Italo-Turkish War in Libya (1911–1912), the Italian military suffered equipment and munition shortages not yet repaired before Italian entry into the Great War.[15] At the opening of the campaign, Austro-Hungarian troops occupied and fortified high ground of the Julian Alps and Karst Plateau, but the Italians initially outnumbered their opponents three-to-one.

Battles of Isonzo in 1915

An Italian offensive aimed to cross the Soča (Isonzo) river, take the fortress town of Gorizia, and then enter the Karst Plateau. This offensive opened the first Battles of the Isonzo.

At the beginning of the First Battle of the Isonzo on 23 June 1915, Italian forces outnumbered the Austrians three-to-one but failed to penetrate the strong Austro-Hungarian defensive lines in the highlands of northwestern Gorizia and Gradisca. Because the Austrian forces occupied higher ground, Italians conducted difficult offensives while climbing. The Italian forces therefore failed to drive much beyond the river, and the battle ended on 7 July 1915.

Despite a professional officer corps, severely under-equipped Italian units lacked morale.[16] Also many troops deeply disliked the newly appointed Italian commander, general Luigi Cadorna.[17] Moreover, preexisting equipment and munition shortages slowed progress and frustrated all expectations for a "Napoleonic style" breakout.[15] Like most contemporaneous militaries, the Italian army primarily used horses for transport but struggled and sometimes failed to supply the troops sufficiently in the tough terrain.

Two weeks later on 18 July 1915, the Italians attempted another frontal assault against the Austro-Hungarian trench lines with more artillery in the Second Battle of the Isonzo. In the northern section of the front, the Italians managed to overrun Mount Batognica over Kobarid (Caporetto), which would have an important strategic value in future battles. This bloody offensive concluded in stalemate when both sides ran out of ammunition.

The Italians recuperated, rearmed with 1200 heavy guns, and then on 18 October 1915 launched the Third Battle of the Isonzo, another attack. Forces of Austria-Hungary repulsed this Italian offensive, which concluded on 4 November without resulting gains.

The Italians again launched another offensive on 10 November, the Fourth Battle of the Isonzo. Both sides suffered more casualties, but the Italians conquered important entrenchments, and the battle ended on 2 December for exhaustion of armaments, but occasional skirmishing persisted.

After the winter lull, the Italians launched the Fifth Battle of the Isonzo on 9 March 1916, and captured the strategic Mount Sabatino. But Austria-Hungary repulsed all other attacks, and the battle concluded on 16 March in poor weather for trench warfare.

The Asiago offensive

Following Italy's stalemate, the Austro-Hungarian forces began planning a counteroffensive (Battle of Asiago) in Trentino and directed over the plateau of Altopiano di Asiago, with the aim to break through to the Po River plain and thus cutting off the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Italian Armies in the North East of the country. The offensive began on 15 May 1916 with 15 divisions, and resulted in initial gains, but then the Italians counterattacked and pushed the Austro-Hungarians back to the Tyrol.

Later battles for the Isonzo

Later in 1916, four more battles along the Isonzo river erupted. The Sixth Battle of the Isonzo, launched by the Italians in August, resulted in a success greater than the previous attacks. The offensive gained nothing of strategic value but did take Gorizia, which boosted Italian spirits. The Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth battles of the Isonzo (14 September – 4 November) managed to accomplish little except to wear down the already exhausted armies of both nations.

The frequency of offensives for which the Italian soldiers partook between May 1915 and August 1917, one every three months, was higher than demanded by the armies on the Western Front. Italian discipline was also harsher, with punishments for infractions of duty of a severity not known in the German, French, and British armies.[18]

Shellfire in the rocky terrain caused 70% more casualties per rounds expended than on the soft ground in Belgium and France. By the autumn of 1917 the Italian army had suffered most of the deaths it was to incur during the war, yet the end of the war seemed to still be an eternity away.[18] This was not the same line of thought for the Austro-Hungarians. On 25 August, the Emperor Charles wrote to the Kaiser the following: "The experience we have acquired in the eleventh battle has led me to believe that we should fare far worse in the twelfth. My commanders and brave troops have decided that such an unfortunate situation might be anticipated by an offensive. We have not the necessary means as regards troops."[19]

Tunnel warfare in the mountains

%252C_l%C3%B6v%C3%A9sz%C3%A1rok%252C_h%C3%A1tt%C3%A9rben_a_Monte_Santo._Fortepan_52341.jpg.webp)

From 1915, the high peaks of the Dolomites range were an area of fierce mountain warfare. In order to protect their soldiers from enemy fire and the hostile alpine environment, both Austro-Hungarian and Italian military engineers constructed fighting tunnels which offered a degree of cover and allowed better logistics support. Working at high altitudes in the hard carbonate rock of the Dolomites, often in exposed areas near mountain peaks and even in glacial ice, required extreme skill of both Austro-Hungarian and Italian miners.

Beginning on the 13th, later referred to as White Friday, December 1916 would see 10,000 soldiers on both sides killed by avalanches in the Dolomites.[20] Numerous avalanches were caused by the Italians and Austro-Hungarians purposefully firing artillery shells on the mountainside, while others were naturally caused.

In addition to building underground shelters and covered supply routes for their soldiers like the Italian Strada delle 52 Gallerie, both sides also attempted to break the stalemate of trench warfare by tunneling under no man's land and placing explosive charges beneath the enemy's positions. Between 1 January 1916 and 13 March 1918, Austro-Hungarian and Italian units fired a total of 34 mines in this theatre of the war. Focal points of the underground fighting were Pasubio with 10 mines, Lagazuoi with 5, Col di Lana/Monte Sief also with 5, and Marmolada with 4 mines. The explosive charges ranged from 110 kilograms (240 lb) to 50,000 kilograms (110,000 lb) of blasting gelatin. In April 1916, the Italians detonated explosives under the peaks of Col Di Lana, killing numerous Austro-Hungarians.

1917: Germany arrives on the front

The Italians directed a two-pronged attack against the Austrian lines north and east of Gorizia. The Austrians checked the advance east, but Italian forces under Luigi Capello managed to break the Austrian lines and capture the Banjšice Plateau. Characteristic of nearly every other theater of the war, the Italians found themselves on the verge of victory but could not secure it because their supply lines could not keep up with the front-line troops and they were forced to withdraw. However, the Italians despite suffering heavy casualties had almost exhausted and defeated the Austro-Hungarian army on the front, forcing them to call in German help for the much anticipated Caporetto Offensive.

The Austro-Hungarians received desperately needed reinforcements after the Eleventh Battle of the Isonzo from German Army soldiers rushed in after the Russian offensive ordered by Kerensky of July 1917 failed. Also arrived German troops from Romanian front after the Battle of Mărășești. The Germans introduced infiltration tactics to the Austro-Hungarian front and helped work on a new offensive. Meanwhile, mutinies and plummeting morale crippled the Italian Army from within. The soldiers lived in poor conditions and engaged in attack after attack that often yielded minimal or no military gain.

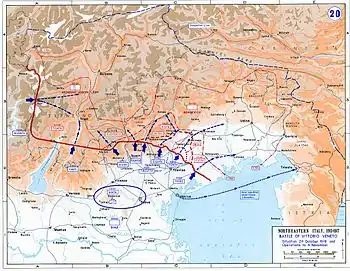

On 24 October 1917 the Austro-Hungarians and Germans launched the Battle of Caporetto (Italian name for Kobarid or Karfreit in German). Chlorine-arsenic agent and diphosgene gas shells were fired as part of a huge artillery barrage, followed by infantry using infiltration tactics, bypassing enemy strong points and attacking on the Italian rear. At the end of the first day, the Italians had retreated 19 kilometres (12 miles) to the Tagliamento River.

When the Austro-Hungarian offensive routed the Italians, the new Italian chief of staff, Armando Diaz ordered to stop their retreat and defend the fortified defenses around the Monte Grappa summit between the Roncone and the Tomatico mountains; although numerically inferior (51,000 against 120,000) the Italian Army managed to halt the Austro-Hungarian and German armies in the First Battle of Monte Grappa.

Second Battle of the Piave River (June 1918)

Advancing deep and fast, the Austro-Hungarians outran their supply lines, which forced them to stop and regroup. The Italians, pushed back to defensive lines near Venice on the Piave River, had suffered 600,000 casualties to this point in the war. Because of these losses, the Italian Government called to arms the so-called 99 Boys (Ragazzi del '99); the new class of conscripts born in 1899 who were turning 18 in 1917. In November 1917, British and French troops started to bolster the front line, from the 5 and 6 divisions respectively provided.[21][22] Far more decisive to the war effort than their troops was the Allies economic assistance by providing strategic materials (steel, coal and crops – provided by the British but imported from Argentina – etc.), which Italy always lacked sorely. In the spring of 1918, Germany pulled out its troops for use in its upcoming Spring Offensive on the Western Front. As a result of the Spring Offensive, Britain and France also pulled half of their divisions back to the Western Front.

The Austro-Hungarians now began debating how to finish the war in Italy. The Austro-Hungarian generals disagreed on how to administer the final offensive. Archduke Joseph August of Austria decided for a two-pronged offensive, where it would prove impossible for the two forces to communicate in the mountains.

The Second Battle of the Piave River began with a diversionary attack near the Tonale Pass named Lawine, which the Italians repulsed after two days of fighting.[23] Austrian deserters betrayed the objectives of the upcoming offensive, which allowed the Italians to move two armies directly in the path of the Austrian prongs. The other prong, led by general Svetozar Boroević von Bojna initially experienced success until aircraft bombed their supply lines and Italian reinforcements arrived.

The decisive Battle of Vittorio Veneto (October–November 1918)

To the disappointment of Italy's allies, no counter-offensive followed the Battle of Piave. The Italian Army had suffered huge losses in the battle, and considered an offensive dangerous. General Armando Diaz waited for more reinforcements to arrive from the Western Front. By the end of October 1918, Austro-Hungary was in a dire situation. Czechoslovakia, Croatia, and Slovenia proclaimed their independence and parts of their troops started deserting, disobeying orders and retreating. Many Czechoslovak troops, in fact, started working for the Allied Cause, and in September 1918, five Czechoslovak Regiments were formed in the Italian Army.

By October 1918, Italy finally had enough soldiers to mount an offensive. The attack targeted Vittorio Veneto, across the Piave. The Italian Army broke through a gap near Sacile and poured in reinforcements that crushed the Austro-Hungarian defensive line. On 31 October, the Italian Army launched a full scale attack and the whole front began to collapse. On 3 November, 300,000 Austro-Hungarian soldiers surrendered, at the same day the Italians entered Trento and Trieste, greeted by the population.

On 3 November, the military leaders of the already disintegrated Austria-Hungary sent a flag of truce to the Italian commander to ask again for an armistice and terms of peace. The terms were arranged by telegraph with the Allied authorities in Paris, communicated to the Austro-Hungarian commander, and were accepted. The Armistice with Austria was signed in the Villa Giusti, near Padua, on 3 November, and took effect at three o'clock in the afternoon of 4 November. Austria and Hungary signed separate armistices following the overthrow of the Habsburg monarchy and the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Casualties

Italian military deaths numbered 834 senior officers and generals, 16,872 junior officers, 16,302 non-commissioned officers, and 497,103 enlisted men, for a total of over 531,000 dead. Of these, 257,418 men came from Northern Italy, 117,480 from Central Italy, and 156,251 from Southern Italy.[24]

Austro-Hungarian KIAs (this category does not include soldiers who perished in the rear or as POWs) amounted to 4,538 officers and 150,812 soldiers, for a total of 155,350 dead. The losses were increasing over time; there were 31,135 killed in 1915, 38,519 in 1916, 42,309 in 1917 and 43,387 in 1918. [25] While the KIA numbers of Italian soldiers on the Italian front in 1915 were 66,090 killed , in 1916 this figure was 118,880 killed, in 1917 it was 152,790 killed, and in 1918 it stood at 40,250 killed soldiers.[26]

Occupation of northern Dalmatia and Tyrol

By the end of hostilities in November 1918, the Italian military had seized control of the entire portion of Dalmatia that had been guaranteed to Italy by the London Pact.[27] From 5–6 November 1918, Italian forces were reported to have reached Lissa, Lagosta, Sebenico, and other localities on the Dalmatian coast.[28] In 1918, Admiral Enrico Millo declared himself Italy's Governor of Dalmatia.[27] After 4 November the Italian military occupied also Innsbruck and all Tyrol by 20–22,000 soldiers of the III Corps of the First Army.[29][30]

(From Italian weekly La Domenica del Corriere, 24 September 1916).

._Sottoscrivete_al_presto_(Unterzeichnet_schnell)._1917._135_x_100_cm._(Slg.Nr._755)_Kopie.jpg.webp)

Italian Army Order of Battle as of 24 May 1915

source:[31]

First ArmyLieutenant General Roberto Brusati III CorpsLieutenant General Vittorio Camerana

V Corpssource:[37] Lieutenant General Florenzio Aliprindi

Army Troops

Second ArmyLieutenant General Pietro Frugoni II CorpsLieutenant General Enzio Reisoli

IV Corpssource:[45] Lieutenant General Mario Nicolis de Robilant

XII Corpssource:[47] Lieutenant General Luigi Segato

Army Troops

Third Armysource:[53] His Royal Highness, Prince Emanuele Filiberto, Duke of Aosta[54] VI Corpssource:[55] Lieutenant General Carlo Ruelle

VII Corpssource:[59] Lieutenant General Vincenzo Garioni

XI CorpsMain Source:[64] Lieutenant General Giorgio Cigliana

Army Troops

|

Fourth Armysource:[67] Lieutenant General Luigi Nava I CorpsLieutenant General Ottavio Ragni

IX CorpsLieutenant General Pietro Marini

Army Troops

Carnia Zonesource:[69] Lieutenant General Clemente Lequio

High Command Troopssource:[70] VIII Corpssource:[71] Lieutenant General Ottavio Briccola

X Corpssource:[73] Lieutenant General Domenico Grandi

XIII Corpssource:[74] Lieutenant General Gaetano Zoppi

XIV Corpssource:[78] Lieutenant General Paolo Morrone

3rd Cavalry DivisionLieutenant General Carlo Guicciardi di Cervarolo

4th Cavalry Divisionsource:[80] Lieutenant General Alessandro Malingri di Bagnolo

Misc.

|

See also

- Austro-Hungarian fortifications on the Italian border

- Museum of the White War in Adamello - located in Temù, in the Upper Val Camonica.

- White War

Notes

- Mortara 1925, pp. 28–29

- Clodfelter 2017, p. 419.

- Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire During the Great War 1914–1920, The War Office, p. 744.

- Bodart, Gaston: "Erforschung der Menschenverluste Österreich-Ungarns im Weltkriege 1914–1918," Austrian State Archive, War Archive Vienna, Manuscripts, History of the First World War, in general, A 91. Reports that 30% of Austro-Hungarian killed/wounded were incurred on the Italian front (including 155,350 out of 521,146 fatalities). While the casualty records remain incomplete (Bodart on the same page estimates the missing war-losses and gets a total figure of 1,213,368 deaths rather than 521,146), the proportions are accurate. 30% of casualties equates to 363,000 dead and 1,086,000 wounded.

- Heinz von Lichem, "Gebirgskrieg," Volume 3. States that 1/3 of Austro-Hungarian casualties were incurred on the Italian front, which if accurate would equate to 400,000 killed, 1,210,000 wounded, and 730,000 missing/captured.

- Tortato, Alessandro: La Prigionia di Guerra in Italia, 1914–1919, Milan 2004, pp. 49–50. Does not include 18,049 who died. Includes 89,760 recruited into various units and sent back to fight the AH army, and 12,238 who were freed.

- Clodfelter gives the total missing/captured as 653,000; well-documented Italian sources give the total number of prisoners as 477,024.

- Spencer C. Tucker (2002). The Great War, 1914-1918 (Warfare and History). Routledge. p. 119. ISBN 9781134817504.

- Petra Svoljšak (1991). Slovene refugees in Italy during the First World War (Slovenski begunci v Italiji med prvo svetovno vojno), Ljubljana. Diego Leoni – Camillo Zadra (1995), La città di legno: profughi trentini in Austria 1915–1918, Trento-Rovereto 1995.

-

"Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Nicolle 2003, p. 3

- "Expanded version of 1912 (In English) – World War I Document Archive". wwi.lib.byu.edu. Archived from the original on 14 January 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- Nicolle 2003, p. 5

- Smith, Denis Mack (1997). Modern Italy: A Political History. Ann Arbor: Univ. of Michigan Press. p. 262. ISBN 0-472-10895-6.

- Keegan, John (1999). The First World War. Knopf, N.Y. pp. 226, 227. ISBN 0-375-40052-4.

- Keegan 1998, p. 246.

- Keegan 1998, p. 376.

- Keegan 2001, p. 319.

- Keegan 2001, p. 322.

- Thompson, Mark (2008). The White War: Life and Death on the Italian Front, 1915–1919. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-22333-6.

- Williamson, Howard J. (2020). The award of the Military Medal for the campaign in Italy 1917-1918. privately published by Anne Williamson. ISBN 978-1-8739960-5-8.

The book includes: – A detailed overview of the Italian Campaign and its battles. – Notes on the [five] Divisions engaged in Italy.

- "Liste précise régiments [parmi 6 divisions] en Italie". Forum pages14-18 (in French). 10 April 2006. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "From the website of the museum of the war on Adamello". museoguerrabianca.it. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- Ministry of War and later Ministry of Defence: Albo d’Oro [Roll of Honour], 28 vols., Rome 1926–1964.

- Anatol Schmied-Kowarzik, War Losses (Austria-Hungary), [in:] International Encyclopedia of the First World War [accessed May 31, 2021]

- Pierluigi Scolè, , [in:] International Encyclopedia of the First World War [accessed May 31, 2021]

- Paul O'Brien. Mussolini in the First World War: the Journalist, the Soldier, the Fascist. Oxford, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Berg, 2005. Pp. 17.

- Giuseppe Praga, Franco Luxardo. History of Dalmatia. Giardini, 1993. Pp. 281.

- Low, Alfred D. (1974). The Anschluss Movement, 1918–1919, and the Paris Peace Conference. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. p. 296. ISBN 0-87169-103-5. Jump up ^

- Andrea di Michele. "Trento, Bolzano e Innsbruck: l'occupazione militare italiana del Tirolo (1918–1920)" (PDF) (in Italian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- Compiled from information in L’Esercito italiano nella grande guerra, Vol I-bis, pp. 75–104

- Roman numerals indicate battalion numbers; missing numbers were with the Colonial Army

- The other 3 batteries were assigned to XIV Corps.

- 75 mm Krupp cannon (75/27 Model 1906).

- One squadron attached to 1st Army.

- The heavy field artillery batteries were armed with Krupp 149/12 howitzers, which were essentially Krupp 15 cm M. 1913 howitzers.

- 11 June, 23rd squadron of mobile militia cavalry; 29 June, 21st squadron of mobile militia cavalry: both arrived & attached to V Corps. Attached: 305 mm howitzer battery 5 (arr. 1 June).

- 4 June, 4th Group of mobile militia cavalry (Squadrons 7 & 8) arrived and attached to 15th Division.

- Five batteries arrived on 26 May; the other two batteries assigned to XIV Corps.

- Deport 75 mm cannon (75/27 Mod. 1911).

- Under command of the Presidio of the Verona Fortress

- Under command of the Presidio of the Verona Fortress [Lieutenant General Gaetano Gabbo] (together with five batteries of 87 B, 1 battery of 149 G. & 2 batteries of 57)

- Under command of the Presidio of the Verona Fortress.

- 2 June, 1st Group of mobile militia cavalry (Squadrons 1 & 2) arrived and attached to 32nd Division.

- 3 June 14 Light Cavalry Regiment of Alessandria arrived and attached to IV Corps. Also on 3 June, 2nd Group of mobile militia cavalry (Squadrons 3 & 4) arrived and attached to IV Corps.

- 1st Co in the colonies; replaced with 1st bis Co.

- 4 June 15 Light Cavalry Regiment of Lodi (Squadrons 2–6) arrived and attached to XII Corps. Squadron 1 was in Libya.

- Table on allocation of mountain batteries (L'Esercito italiano nella grande guerra, Vol I-bis, p. 98) lists both 13th Group & 14th Group with the 36th Field Artillery.

- 1st Group was with 23rd Division; 3rd Group was with 24th Division.

- The 149 A cannon was a 149 mm cannon (model 149/35 A) with a steel barrel first manufactured in 1900 to replace the older 149 G (149/23).

- The 149 G cannon was a 149 mm cannon (model 149/23) with a cast iron barrel first manufactured in 1882.

- The 70 mm pack mountain gun (model 70/15) was introduced in 1904. The gun could be broken down into 4 pieces for transport by pack animals.

- Attached for the “first bound forward”: 149 G batteries 1–4.

- On 26 May His Royal Highness assumed command of the 3rd Army, which from 24 to 26 May was held temporarily by General Garioni.

- 28 May the 17th Light Cavalry Regiment of Caserta arrived and was attached to VI Corps. The regiment arrived with 5 squadrons, with 1st bis Squadron replacing 1st Squadron, which was in Libya.

- The other squadron of this regiment was attached to the Carnia Zone command.

- A Krupp 75 mm cannon designed for horse artillery (75/27 mod. 1912).

- The 2nd Group of this regiment (batteries 4 & 5) was assigned to 1st Cavalry Division

- 10 June 29 Light Cavalry Regiment of Udine arrived and was attached to VII Corps. Also attached: 310 mm howitzer battery 6 (arr. 10 July)

- Detached to 1st Cavalry Division, VI Corps

- One battalion detached to 2nd Cavalry Division

- 1st bis Co replaced 1st Co which was in the colonies.

- 1st bis Co replaced 1st Co which was in the colonies; one battalion detached to 2nd Cavalry Division.

- 2 June 11 Light Cavalry Regiment of Foggia arrived and was attached to this corps.

- the Brigade headquarters and 10th Infantry Regiment detached to 2nd Cavalry Division.

- Detached from the Queen's Brigade.

- Attached: 149 A batteries Nos 8 & 9; 305 mm howitzer batteries Nos 1 (arr. 1 June) & 2 (arr. 2 June); 280 mm howitzer battery Nos 4 (arr. 6 June), 5 (arr. 3 June), 6 (arr. 3 June) & 7 (arr. 6 June); 210 mm howitzer battery No 2 (arr. 30 May); 210 mortar batteries Nos 7, 8 (both arr. 3 June), 9 (at Belluno 31 May), 10 & 11.

- The other three batteries were assigned to 31st Division.

- Controlled by the High Command. Attached: 149 A batteries Nos 2–6 (still at Stretti); 310 mm howitzer batteries Nos 3 & 4 (both arr. 1 June); 280 mm howitzer batteries Nos 1–3 (on 24 May via RR directed to Stazione for the Carnia ); 210 howitzer battery No 1 (on 24 May at Spillimbergo); 210 mm mortar batteries Nos 1, 2 (24 May both at Spilimbergo), 3 (29 May at Chiusaforte), 4 (24 May at Spilimbergo), 5 & 6.

- Comando Supremo, headed by Lieutenant General Count Luigi Cadorna.

- 30 May the 2nd Bersagliari Cyclist Battalion left Rome to join this corps.

- 29 May the 3rd Group of Mobile Militia cavalry (Squadrons Nos 5 & 6) arrived and were attached to 26th Division. 11 June, the 9th Group of Mobile Militia cavalry (Squadrons Nos 17 & 18) arrived and were attached to 29th Division.

- 6 June 18 Light Cavalry Regiment of Piacenza arrived and was attached to X Corps; the regiment arrived with 5 squadrons ( Nos 1, 2, 4, 5& 6) with Squadron No 3 in Libya. 5 June 1 Bersagliari Cyclist Battalion left Naples to join this corps.

- 5 June the Royal Piemonte Cavalry Regiment (-) (Squadrons Nos 3, 4 & 5) joined XIII Corps; the other two squadrons were attached to XIV Corps.

- 3 June, the 10th Group of Mobile Militia cavalry (Squadron Nos 19 & 20) arrived and were attached to 25th Division.

- 1 June, the 6th Group of Mobile Militia cavalry (Squadron Nos 11 & 12) arrived and were attached to 30th Division.

- 12 June, the 8th Group of Mobile Militia cavalry (Squadron Nos 15 & 16) arrived and attached to 31st Division.

- 5 June Squadron Nos 1 & 2 of Royal Piemonte Cavalry Regiment joined XIV Corps; the rest of the regiment joined XIII Corps.

- 30 June, the 7th Group of Mobile Militia cavalry (Squadron Nos 13 & 14) arrived and was attached to 28th Division.

- 3 June 4 Bersagliari Cyclist Battalion left Turin to join this division.

- Squadron No 2 in Libya.

- Under the command of the Piazza di Venezia

- The Trappani Brigade was constituted in Palermo on 14 January 1915 with 3 regiments 143rd, 144th and 149th. In May it was dissolved. On 4 May the 149th Regiment was transferred to Brindisi, where it remained at the disposition of the Navy until, on 23 June, it moved into a war zone (Treviso) at the disposition of the High Command. On 6 May the 143rd Regiment (composed of troops from both the 143rd and 144th Regiments) sailed for Libya. The remaining troops of the 143rd and 144th Regiments reformed on the 144th Regiment HQ. On 4 July, the 144th Regiment left for Spresiano. On 4 July the brigade reformed with two regiments: 144th (9 companies) and 149th (12 companies).

- Detached to Brundisi; rejoined 4 July

Sources

- Erlikman, Vadim (2004). Poteri narodonaseleniia v XX veke : spravochnik. Moscow. ISBN 5-93165-107-1.

- Cassar, George H. (1998). The Forgotten Front: The British Campaign in Italy, 1917–1918. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 1-85285-166-X.

- Clodfelter, M. (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015 (4th ed.). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0786474707.

- Edmonds, J. E.; Davies, Sir Henry Rodolph (1949). Military Operations: Italy 1915–1919. History of the Great War based on Official Documents by Direction of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Maps in rear cover folder. London: HMSO. OCLC 4839237.

- Keegan, John (2001). The first World War; An Illustrated History. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0-09-179392-0.

- Keegan, John (1998). The first World War. London: Random House (UK). ISBN 0-09-1801788.

- Mortara, G (1925). La Salute pubblica in Italia durante e dopo la Guerra. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Nicolle, David (2003). The Italian Army of World War I. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-398-5.

- Page, Thomas Nelson (1920). Italy and the World War. New York, Charles Scribner's Sons, Full Text Available Online.

- Thompson, Mark (2008). The White War: Life and Death on the Italian Front, 1915–1919. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-465-01329-6.