Iyer

Iyers (also spelt as Ayyar, Aiyar, Ayer, or Aiyer) are an ethnoreligious community of Tamil-speaking Hindu Brahmins. Most Iyers are followers of the Advaita philosophy propounded by Adi Shankara and adhere to the Smarta tradition.[1] This is in contrast to the Iyengar community, who are adherents of Sri Vaishnavism. The Iyers and the Iyengars are together referred to as Tamil Brahmins. The majority of Iyers reside in Tamil Nadu, India.

| Iyer | |

|---|---|

Vadama Iyer priests | |

| Guru | Ādi Śaṅkarā |

| Religions | Hinduism |

| Languages | Tamil, Sanskrit |

| Country | India |

| Original state | Tamil Nadu |

| Populated states | Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka |

| Family names | Iyer, Sastri, Bhattar |

| Subdivisions | Vadama Brahacaraṇam Dīkṣitar Aṣṭasāhasram Śōḻiya |

| Related groups | Kerala Iyers Iyengars Vaidiki Brahmins Vaidiki Velanadu Havyaka Brahmin Hoysala Karnataka Brahmins Sthanika Brahmins Babburkamme |

Iyers are further divided into various denominations based on traditional and regional differences. Like all Brahmins, they are also classified based on their gotra, or patrilineal descent, and the Veda that they follow. They fall under the Pancha Dravida Brahmana classification of Brahmins in India.

Apart from the prevalent practice of using the title "Iyer" as surname, Iyers also commonly use other surnames, such as Sāstri[2] or Bhattar.

Etymology

Iyer (Tamil: ஐயர், pronounced [aɪjəɾ]) has several meanings in Tamil and other Dravidian languages, often referring to a respectable person. The Dravidian Etymological Dictionary lists various meanings for the term such as "father, sage, priest, teacher, brahman, superior person, master, king" with cognates such as tamayan meaning "elder brother" and simply ai "lord, master, husband, king, guru, priest, teacher, father".[3] Linguistic sources often derive the words Ayya, Ayira/Ayyira as Prakrit versions of the Sanskrit word Aryā which means 'noble'.[4][5]

In ancient times, Iyers were also called Anthanar[6] or Pārppān,[7][8] though the usage of the word Pārppān is considered derogatory in modern times. Until recent times, Kerala Iyers were called Pattars. Like the term pārppān, the word Pattar too is considered derogatory.[9]

Population and distribution

Today, Iyers live all over South India, but an overwhelming majority of Iyers continue to thrive in Tamil Nadu. Tamil Brahmins form an estimated less than 3 per cent of the state's total population and are distributed all over the state. However, accurate statistics on the population of the Iyer community are unavailable.[10]

Iyers are also found in fairly appreciable number in Western and Southern districts of Tamil Nadu. Iyers of the far south are called Tirunelveli Iyers and speak the Tirunelveli Brahmin dialect.

Migration

Over the last few centuries, many Iyers have migrated and settled in parts of Karnataka. During the rule of the Mysore Maharajahs, many Iyers from the then Madras province migrated to Mysore. The Ashtagrama Iyers are also a prominent group of Iyers in Karnataka.

Iyers have also been resident of the princely state of Travancore from ancient times. The Venad state (present Kanyakumari district) and the southern parts of Kerala was part of the Pandyan kingdom known as Then Pandi Nadu. There were also many Iyers in Venad which later on grew to be the Travancore state. The old capital of Travancore was Padmanabhapuram which is at present in Kanyakumari district. There has also been a continuous inflow from Tirunelveli and Ramnad districts of Tamil Nadu which are contiguous to the erstwhile princely state of Travancore. Many parts of the present Tirunelveli district were even part of the old Travancore state. These Iyers are known today as Trivandrum Iyers. Some of these people migrated to Cochin and later to Palakkad and Kozhikode districts. There were also migrations from Tanjore district of Tamil Nadu to Palakkad. Their descendants are known today as Palakkad Iyers. These Iyers are collectively now called as Kerala Iyers. In Coimbatore, there are many such Iyers due to its proximity to Kerala.[11] According to the Buddhist scripture Mahavamsa, the presence of Brahmins have been recorded in Sri Lanka as early as 500BC when the first migrations from the Indian mainland supposedly took place. Currently, Brahmins are an important constituent of the Sri Lankan Tamil minority.[12][13] Tamil Brahmins are believed to have played a historic role in the formation of the Jaffna Kingdom.[13][14][15]

Apart from South India, Iyers have also migrated to and settled in places in North India. There are significantly large Iyer communities in Mumbai,[16][17] and Delhi.[18] These migrations, which commenced during the British rule, were often undertaken in search of better prospects and contributed to the prosperity of the community.[19]

In recent times Iyers have also migrated in significant numbers to the United Kingdom, Europe and the United States[17] in search of better fortune.[20]

Subsects

Iyers have many sub-sects among them, such as Vadama, Brahacharnam or Brahatcharanam, Vāthima, Sholiyar or Chozhiar, Ashtasahasram, Mukkāni, Gurukkal, Kāniyālar and Prathamasāki.[21] Each sub-sect is further subdivided according to the village or region of origin.

Iyers, like all other Brahmins, trace their paternal ancestry to one of the eight rishis or sages.[22][23] Accordingly, they are classified into eight gotras based on the rishi they have descended from. A maiden in the family belongs to gotra of her father, but upon marriage takes the gotra of her husband.

The Vedas are further sub-divided into shakhas or "branches" and followers of each Veda are further sub-divided based on the shakha they adhere to. However, only a few of the shakhas are extant, the vast majority of them having disappeared. The different Vedas and the corresponding shakhas that exist today in Tamil Nadu are:[24]

| Veda | shākhā |

|---|---|

| Rig Veda | Shakala and Paingi |

| Yajur Veda | Kanva and Taittiriya |

| Sama Veda | Kauthuma, Jaiminiya/Talavakara, Shatyayaniya and Gautama |

| Atharva Veda | Shaunakiya and Paippalada |

Culture

Rituals

Iyer rituals comprise rites as described in Hindu scriptures such as Apastamba Sutra attributed to the Hindu sage Apastamba. The most important rites are the Shodasa Samaskāras or the 16 duties. Although many of the rites and rituals followed in antiquity are no longer practised, some have been retained.[25][26]

Iyers are initiated into rituals at the time of birth. In ancient times, rituals used to be performed when the baby was being separated from mother's umbilical cord. This ceremony is known as Jātakarma. However, this practice is no longer observed. At birth, a horoscope is made for the child based on the position of the stars. The child is then given a ritual name.[27] On the child's birthday, a ritual is performed to ensure longevity. This ritual is known as Ayushya Homam. This ceremony is held on the child's birthday reckoned as per the Tamil calendar based on the position of the nakshatras or stars and not the Gregorian calendar.[27] The child's first birthday is the most important and is the time when the baby is formally initiated by piercing the ears of the boy or girl. From that day onwards a girl is expected to wear earrings.

A second initiation (for the male child in particular) follows when the child crosses the age of seven. This is the Upanayana ceremony during which a Brahmana is said to be reborn. A three-piece cotton thread is installed around the torso of the child encompassing the whole length of his body from the left shoulder to the right hip. The Upanayana ceremony of initiation is solely performed for the members of the dvija or twice-born castes, generally when the individual is between 7 and 16 years of age.[28][29] In ancient times, the Upanayana was often considered as the ritual which marked the commencement of a boy's education, which in those days consisted mostly of the study of the Vedas. However, with the Brahmins taking to other vocations than priesthood, this initiation has become more of a symbolic ritual. The neophyte was expected to perform the Sandhya Vandanam on a regular basis and utter a prescribed set of prayers, three times a day: dawn, mid-day, and dusk. The most sacred and prominent of the prescribed set of prayers is the Gayatri Mantra, which is as sacred to the Hindus as the Six Kalimas to the Muslims and Ahunwar to the Zoroastrians. Once a year, Iyers change their sacred thread. This ritual is exclusive to South Indian Brahmins and the day is commemorated in Tamil Nadu as Āvani Avittam.[30][31]

Other important ceremonies for Iyers include the rites for the deceased. All Iyers are cremated according to Vedic rites, usually within a day of the individual's death.[32] The death rites include a 13-day ceremony, and regular Tarpanam[33] (performed every month thereafter, on Amavasya day, or New Moon Day), for the ancestors. There is also a yearly shrārddha, that must be performed. These rituals are expected to be performed only by male descendants of the deceased. Married men who perform this ritual must be accompanied by their wives. The women are symbolically important in the ritual to give a "consent" to all the proceedings in it.[34]

Festivals

Iyers celebrate almost all Hindu festivals like Deepavali, Navratri, Pongal, Vinayaka Chathurthi, Janmaashtami, Tamil New Year, Sivarathri and Karthika Deepam.

However, the most important festival which is exclusive to Brahmins of South India is the Āvani Avittam festival.[35]

Weddings

A typical Iyer wedding consists of Sumangali Prārthanai (Hindu prayers for prosperous married life), Nāndi (homage to ancestors), Nischayadhārtham (Engagement) and Mangalyadharanam (tying the knot). The main events of an Iyer marriage include Vratam (fasting), Kasi Yatra (pilgrimage to Kasi), Oonjal (Swing), Kanyadanam (placing the bride in the groom's care), Mangalyadharanam, Pānigrahanam and Saptapathi (or seven steps - the final and most important stage wherein the bride takes seven steps supported by the groom's palms thereby finalizing their union). This is usually followed by Nalangu, which is a casual and informal event.[36]

Traditional ethics

Iyers generally lead orthodox lives and adhere steadfastly to their customs and traditions. Iyers follow the Grihya Sutras of Apastamba and Baudhayana. The society is patriarchal but not feudal.[37]

Iyers are generally vegetarian. Some abjure onion and garlic on the grounds that they activate certain base senses.[38] Cow milk and milk products were approved. They were required to avoid alcohol and tobacco.[39]

Iyers follow elaborate purification rituals, both of self and the house. Men are forbidden from performing their "sixteen duties" while women are forbidden from cooking food without having a purificatory bath in the morning.[38] Food is to be consumed only after making an offering to the deities.

The bathing was considered sufficiently purifying only if it conformed to the rules of madi.[38] The word madi is used by Tamil Brahmins to indicate that a person is bodily pure. In order to practice madi, the Brahmin had to wear only clothes which had been recently washed and dried, and the clothes should remain untouched by any person who was not madi. Only after taking bath in cold water, and after wearing such clothes, would the person be in a state of madi.[40] This practice of madi is followed by Iyers even in modern times, before participating in any kind of religious ceremony.[38]

.

Clothing

Iyer men traditionally wear veshtis or dhotis which cover them from waist to foot. These are made of cotton and sometimes silk. Veshtis are worn in different styles. Those worn in typical brahminical style are known as panchakacham (from the sanskrit terms pancha and gajam meaning "five yards" as the length of the panchakacham is five yards in contrast to the veshtis used in daily life which are four or eight cubits long). They sometimes wrap their shoulders with a single piece of cloth known as angavastram (body-garment). In earlier times, Iyer men who performed austerities also draped their waist or chests with deer skin or grass.

The traditional Iyer woman is draped in a nine-yard saree, also known as madisār.[42]

Patronage of art

For centuries, Iyers have taken a keen interest in preserving the arts and sciences. They undertook the responsibility of preserving the Natya Shastra, a monumental work on Bharatanatyam, the classical dance form of Tamil Nadu. During the early 20th century, dance was usually regarded as a degenerate art associated with devadasis. Rukmini Devi Arundale, however, revived the dying art of Sadir into the more "respectable" art form of Bharatanatyam, thereby breaking social and caste taboos about Brahmins taking part in the study and practice of dance.[43][44] However many have claimed that, rather than becoming more open to other communities, the practice of Bharatanatyam was then restricted specifically to the middle and upper classes of Tamil society.[45]

However, compared to dance, the contribution of Iyers in field of music has been considerably noteworthy.[46][47]

Food

The main diet of Iyers is composed of vegetarian food,[48] mostly rice which is the staple diet for millions of South Indians. Vegetarian side dishes are frequently made in Iyer households apart from compulsory additions as rasam, sambar, etc. Home-made ghee is a staple addition to the diet, and traditional meals do not begin until ghee is poured over a heap of rice and lentils. The cuisine eschews the extent of spices and heat traditionally found in south Indian cuisine. Iyers are mostly known for their love for curd. Other South Indian delicacies such as dosas, idli, etc. are also relished by Iyers. Coffee amongst beverages and curd amongst food items form an indispensable part of the Iyer food menu.

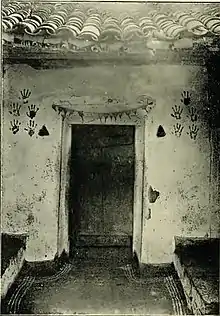

Housing

In ancient times, Iyers, along with Iyengars and other Tamil Brahmins, lived in exclusive Brahmin quarters of their village known as an agrahāram. Shiva and Vishnu temples were usually situated at the ends of an agrahāram. In most cases, there would also be a fast-flowing stream or river nearby.[49]

A typical agrahāram consisted of a temple and a street adjacent to it. The houses on either side of the street were exclusively peopled by Brahmins who followed a joint family system. All the houses were identical in design and architecture though not in size.[50]

With the arrival of the British and commencement of the Industrial Revolution, Iyers started moving to cities for their sustenance. Starting from the late 19th century, the agrahārams were gradually discarded as more and more Iyers moved to towns and cities to take up lucrative jobs in the provincial and judicial administration.[51]

However, there are still some agrahārams left where traditional Iyers continue to reside. In an Iyer residence, people wash their feet first with water on entering the house.[52][53]

Language

Tamil is the mother tongue of most Iyers residing in India and elsewhere. However, Iyers speak a distinct dialect of Tamil unique to their community.[54][55][56] This dialect of Tamil is known as Brāhmik or Brahmin Tamil. Brahmin Tamil is highly Sanskritized and has often invited ridicule from Tamil purists due to its extensive usage of the Sanskrit vocabulary.[57] While Brahmin Tamil used to be the lingua franca for inter-caste communication between different Tamil communities during pre-independence times, it has been gradually discarded by Brahmin themselves in favour of regional dialects.[58]

Iyers today

In addition to their earlier occupations, Iyers today have diversified into a variety of fields.[59] Three of India's Nobel laureates, Sir C. V. Raman, Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar and Venkatraman Ramakrishnan hail from the community.[60]

Since ancient times, Iyers, as members of the privileged priestly class, exercised a near-complete domination over educational, religious and literary institutions in the Tamil country.[61] Their domination continued throughout the British Raj as they used their knowledge of the English language and education to dominate politics, administration, the courts and intelligentsia. Upon India's independence in 1947, they tried to consolidate their hold on the administrative and judicial machinery. Such a situation led to resentment from the other castes in Tamil Nadu, the result of this atmosphere was a "non-Brahmin" movement and the formation of the Justice Party.[62] Periyar, who took over as Justice Party President in the 1940s, changed its name to Dravida Kazhagam, and formulated the view that Tamil Brahmins were Aryans as opposed to non-Brahmin Tamils who were Dravidian.[63] The ensuing anti-Brahminism and the rising unpopularity of the Rajaji Government left an indelible mark on the Tamil Brahmin community ending their political aspirations. In the 1960s the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (roughly translated as "Organisation for Progress of Dravidians") and its subgroups gained political ground on this platform forming state ministries, thereby wrenching control from the Indian National Congress, in which Iyers at that time were holding important party positions. Today, apart from a few exceptions, Iyers have virtually disappeared from the political arena.[64][65][66][67][68]

In 2006, the Tamil Nadu government took the decision to appoint non-Brahmin priests in Hindu temples in order to curb Brahmin ecclesiastical domination.[69] This created a huge controversy. Violence broke out in March 2008 when a non-Brahmin oduvar or reciter of Tamil idylls, empowered by the Government of Tamil Nadu, tried to make his way into the sanctum sanctorum of the Nataraja temple at Chidambaram.[70]

Criticism

Relations with other communities

The legacy of Iyers have often been marred by accusations of racism and counter-racism against them by non-Brahmins and vice versa.

Grievances and instances of discrimination by Brahmins are believed to be the main factors which fuelled the Dravidian Movement.[62] With the dawn of the 20th century, and the rapid penetration of western education and western ideas, there was a rise in consciousness amongst the lower castes who felt that rights which were legitimately theirs were being denied to them.[62] This led the non-Brahmins to agitate and form the Justice Party in 1916, which later became the Dravidar Kazhagam. The Justice Party banked on vehement anti-Hindu and anti-Brahmin propaganda to ease Brahmins out of their privileged positions. Gradually, the non-Brahmin replaced the Brahmin in every sphere and destroyed the monopoly over education and the administrative services which the Brahmin had previously held.[71]

The concept of "Brahmin atrocities" is refuted by some Tamil Brahmin historians. They argue that allegations of casteism against Tamil Brahmins have been exaggerated and that even prior to the rise of the Dravida Kazhagam, a significant section of Tamil Brahmin society was liberal and anti-casteist. They cite the example of the Temple Entry Proclamation passed by the princely state of Travancore which gave people of all castes the right to enter Hindu temples in the princely state was due to the efforts of the Dewan of Travancore, Sir C. P. Ramaswamy Iyer who was an Iyer.[72]

Dalit leader and founder of political party Pudiya Tamizhagam, Dr.Krishnasamy admits that the Anti-Brahmin Movement had not succeeded up to the expectations and that there continues to be as much discrimination of Dalits as had been before.

So many movements have failed. In Tamil Nadu there was a movement in the name of anti-Brahmanism under the leadership of Periyar. It attracted Dalits, but after 30 years of power, the Dalits understand that they are as badly-off - or worse-off - as they were under the Brahmans. Under Dravidian rule, they have been attacked and killed, their due share in government service is not given, they are not allowed to rise.[73]

Alleged negative attitude towards Tamil language and culture

Iyers have been called Sanskritists who entertained a distorted and contemptuous attitude towards Tamil language, culture and civilization.[74] The Dravidologist Kamil Zvelebil says that the Brahmin was chosen as a scapegoat to answer for the decline of Tamil civilization and culture in the medieval and post-medieval periods.[75][76] Agathiar, usually identified with the legendary Vedic sage Agastya is credited with compiling the first rules of grammar of the Tamil language.[77] Moreover, individuals like U. V. Swaminatha Iyer and Subramanya Bharathi have made invaluable contributions to the Dravidian Movement.[78][79] Parithimar Kalaignar was the first to campaign for the recognition of Tamil as a classical language.[80]

Portrayal in popular media

Brahmins are mentioned for the first time in the works of Sangam poets. During the early Christian era, Brahmin saints have been frequently praised for their efforts in combating Buddhism. In modern times, when Iyers and Iyengars control a significant percentage of the print and visual media, there has been significant coverage of Brahmins and Brahmin culture in magazines and periodicals and a number of Brahmin characters in novels, TV serials and films.

The first known literary work in Tamil to heap criticism on Brahmins was the Tirumanthiram, a treatise on Yoga from the 13th century.[81][82] The writings and speeches of Iyothee Thass, Maraimalai Adigal, Periyar, Bharatidasan, C. N. Annadurai and the leaders of Justice Party in the early 20th century and of the Dravidar Kazhagam in more modern times constitute much of modern anti-Brahmin rhetoric.[83][84][85]

Starting from the 1940s onwards, Annadurai and the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam have been using films and the mass media for the propagation of their political ideology.[86] Most of the films made, including the 1952-blockbuster Parasakthi, are anti-Brahminical in character.[87]

Notable people

Some of the early members of the community to gain prominence were sages and religious scholars like Agatthiar, Tholkappiyar (Tirunadumakini), Parimelalhagar and Naccinarkiniyar.[77] Prior to the 19th century, almost all prominent members of this community hailed from religious or literary spheres.[88] Tyagaraja, Syama Sastri and Muthuswamy Dīkshitar, who constitute the "Trinity of Carnatic music" were probably the first verified historical personages from the community, as the accounts or biographies of those who lived earlier appear semi-legendary in character.[89] Most of the Dewans of the princely state of Travancore during the 19th century were Tamil Brahmins (Iyers and Iyengars).[90]

See also

- Forward Castes

- Tamil Brahmins

Notes

- Béteille, André (26 October 2020). Caste, Class, and Power. University of California Press. doi:10.1525/9780520317864. ISBN 978-0-520-31786-4.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, śāstrī.

- Burrow, T.; M. B. Emeneau. A Dravidian etymological dictionary. Oxford University Press. p. 19.

- Nagendra Kumar Singh (1999). Encyclopaedia of Hinduism, Volume 7. Anmol Publications PVT LTD. p. 898. ISBN 978-81-7488-168-7.

- Miller, Edward (2009). A Simplified grammar of the Pali language. BiblioBazaar. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-103-26738-5.

- Pillai, Jaya Kothai (1972). Educational System of the Ancient Tamils. Tinnevelly: South India Saiva Siddhanta Works Pub. Society. p. 54.

- Caṇmukam, Ce. Vai. (1967). Naccinarkkiniyar's Conception of Phonology. Annamalai University. p. 212.

- Marr, John Ralston (1985). The Eight Anthologies: A Study in Early Tamil Literature. Institute of Asian Studies. p. 114.

- Nossiter, Thomas Johnson (1982). Communism in Kerala: A Study in Political Adaptation. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-905838-40-3.

- Vepachedu, Sreenivasarao (2003). "Brahmins". Mana Sanskriti (Our Culture) (69).

- Prabhakaran, G. (12 November 2005). "A colourful festival from a hoary past". The Hindu Metro Plus:Coimbatore. Archived from the original on 5 August 2007. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- Civattampi, K. (1995). Sri Lankan Tamil society and politics. Madras: New Century Book House. p. 3. ISBN 81-234-0395-X.

- Ritualizing on the Boundaries, Pg 3

- Gnanaprakasar, S. (1928). A critical history of Jaffna. Gnanaprakasa Yantra Salai. p. 96. ISBN 978-81-206-1686-8.

- Pathmanathan, Pg 1-13

- Ritualizing on the Boundaries, Pg 86

- Ritualizing on the Boundaries, Pg 12

- Migration and Urbanization among Tamil Brahmans, pp. 15-17

- Vishwanath, Rohit (23 June 2007). "BRIEF CASE: Tambram's Grouse". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- Migration and Urbanization among Tamil Brahmans, pp. 180-21

- Leach, E. R. (1960). Aspects of caste in south India, Ceylon, and north-west Pakistan. Cambridge [Eng.] Madras: Published for the Dept. of Archaeology and Anthropology at the University Press. p. 368.

- "Definition of the word gotra". Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- "Gotra". gurjari.net. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- "Shakha". www.dharmicscriptures.org. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- "The Sixteen Samskaras Part-I" (PDF). 8 August 2003. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- "Names of Samskaras". kamakoti.org. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- Austin, Lisette (21 May 2005). "Welcoming baby; Birth rituals provide children with a sense of community, culture". Parentmap. Archived from the original on 8 July 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- "Upanayanam". gurjari.net. Retrieved 2 September 2008.

- Neria Harish Hebbar (2 March 2003). "Customs and Classes of Hinduism". Boloji Media Inc. Archived from the original on 3 February 2007. Retrieved 2 September 2008.

- Jagannathan, Maithily (2005). South Indian Hindu festivals and traditions. Abhinav Publications. p. 93. ISBN 9788170174158.

- Verma, Manish (2002). Fasts and Festivals of India. Diamond Pocket Books (P) Ltd. p. 41. ISBN 978-81-7182-076-4.

- "Transition Rituals". Beliefnet Inc. Retrieved 2 September 2008.

- "Tharpanam". vadhyar.com. Retrieved 2 September 2008.

- Knipe, David M. "The Journey of a Lifebody". Hindu Gateway. Archived from the original on 30 September 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- "Avani Avittam". K.G.Corporate Consultants. Archived from the original on 14 September 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- Vaidyanath, Padma. "A South Indian Wedding – The Rituals and the Rationale". Sawnet. Archived from the original on 12 May 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- Pandey, U. C. (1971). Yajur-Veda: Apastamba-Grhya-Sutra.

- "The Practice of madi". ICSI Berkeley. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- Doniger, Wendy; Smith, Brian K. (1991). The Laws of Manu. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-044540-4.

- Rao, Vasudeva. Living Traditions in Contemporary Contexts: The Madhva Matha of Udipi. Orient Longman. p. 66.

- Lakshmi, S. (23 February 2008). "An oasis of vegetarian calm". Business Standard. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- "A saree caught in a time wrap". The Tribune. 23 January 2005. Retrieved 3 September 2008.

- Roles and Rituals for Hindu Women by Julia Leslie, Pg. 154

- Vishwanathan, Lakshmi (1 December 2006). "How Natyam danced its way into the Academy". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- "How the art of Devadasis was appropriated to create the world of Bharatanatyam". The News Minute. 10 February 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- From the Tanjore Court to the Madras Music Academy: A Social History of Music in South India by Lakshmi Subramanian ISBN 0-19-567835-4

- Jayakumar, Raghavan. "Popularity of Carnatic music". karnatik.com. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- N. Raghunathan. "The Hindu Attitude Towards Vegetarianism". International Vegetarian Union. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- Sashibhushan, M. G. (23 February 2004). "Quaint charm". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 5 July 2004. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- Migration and Urbanization among Tamil Brahmans, pp. 12-13

- Migration and Urbanization among Tamil Brahmans, pp. 6-14

- Srinivasan, Bombai. "The Goal and the Guide, Petal 3:Fire Walking". Sri Satya Sai Baba Website. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- Sridhar, Lalitha (6 August 2001). "Simply South". Business Line. Archived from the original on 23 February 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- "TAMIL: a language of India". Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 14th Edition. 2000. Archived from the original on 14 September 2008. Retrieved 3 September 2008.

- "Streams of Language: Tamil Dialects in History and Literature" (PDF). french Institute of Pondicherry. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 September 2008. Retrieved 3 September 2008.

- Purushotam, Nirmala Srirekham (2000). Negotiating multiculturalism: Disciplining Difference in Singapore. Walter de Gruyter. p. 37.

- Hebbar, Neria Harish (2 February 2003). "Tulu Language: Its Script and Dialects". Boloji Media Inc. Archived from the original on 4 May 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- Schiffman, Harold F. "Standardization or Restandardization: the case for 'Standard' Spoken Tamil".

- Migration and Urbanization among Tamil Brahmans, Pg 1

- "Brahmins dominate all modern professions". Rediff News. 12 October 2009.

- Vivekananda, Swami (1955). The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda. Advaita Ashrama. p. 296. ISBN 81-85301-46-8.

- K. Nambi Arooran (1980). "Caste & the Tamil Nation:The Origin of the Non-Brahmin Movement, 1905-1920". Tamil renaissance and Dravidian nationalism 1905-1944. Koodal Publishers. Retrieved 3 September 2008.

- Selvaraj, Sreeram (30 April 2007). "Periyar was against Brahminism, not Brahmins". Rediff News.

- Geetha, V. (2001). Towards a Non-Brahmin Millennium: From Iyothee Thass to Periyar. Bhatkal & Sen. ISBN 978-81-85604-37-4.

- Omvedt, Gail (2006). Dalit Visions: The Anti-caste Movement and the Construction of an Indian Identity. Orient Longman. p. 95. ISBN 978-81-250-2895-6.

- Rudolph, Lloyd I. (1961). "Urban Life and Populist Radicalism: Dravidian Politics in Madras". The Journal of Asian Studies. 20 (3): 283–297. doi:10.2307/2050816. JSTOR 2050816. S2CID 145124008.

- I. Rudolph, Lloyd; Suzanne Hoeber Rudolph (1969). The Modernity of Tradition: political development in India. University of Chicago. p. 78. ISBN 0-226-73137-5.

- Fuller, C. J. (2003). The Renewal of the Priesthood: Modernity and Traditionalism in a South Indian Temple. Princeton University Press. p. 117. ISBN 0-691-11657-1.

- "Tamil Nadu breaks caste barrier". BBC News. 16 May 2006. Retrieved 6 September 2008.

- "Tension at Chidambaram temple". Web India 123. 2 March 2008. Retrieved 6 September 2008.

- Jayaprasad, K. (1991). RSS and Hindu Nationalism. Deep & Deep Publications. p. 138.

- Omvedt, Gail. "The Dravidian movement". ambedkar.org. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- Zvelebil, Pg 197

- Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature, Pg 212

- Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature, Pg 213

- Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature, Appendix III, The Case of Akattiyam; Sanskrit and Tamil; Kankam, Pg 235–260

- B. Dirks, Nicholas (1996). Castes of Mind: Colonialism and the Making of Modern India. Orient Longman. p. 143. ISBN 81-7824-072-6.

- van der Veer, Peter (1996). Conversion to Modernities: The Globalization of Christianity. Routledge. p. 131. ISBN 0-415-91274-1.

- Saravanan, T. (12 September 2006). "Tamil scholar's house to be made a memorial". The Hindu. Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 10 August 2008.

- Zvelebil, Pg 226

- Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature. Sahitya akademi. 1992. p. 3899. ISBN 978-81-260-1221-3.

- Sachi Sri Kantha (1992). "Part 8: The Twin Narratives of Tamil Nationalism". Selected Writings by Dharmeratnam Sivaram (Taraki). Retrieved 3 September 2008.

- Palanithurai, Ganapathy (1997). Polyethnicity in India and Canada: Possibilities for Exploration. M. D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. p. 107. ISBN 978-81-7533-039-9.

- K. Klostermaier (1994). A survey of Hinduism. SUNY Press. p. 300. ISBN 978-0-7914-2109-3.

- Özbudun, Ergun; Weiner, Myron (1987). Competitive Elections in Developing Countries. Duke University Press. p. 62. ISBN 0-8223-0766-9.

- A. Srivathsan (12 June 2006). "Films and the politics of convenience". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 13 June 2006. Retrieved 20 July 2008.

- Sastri, K. A. Nilakanta (1966). A History of South India from Prehistoric Times to the Fall of Vijayanagar: from prehistoric times to the fall of Vijayanagar. Oxford University Press. p. 289. ISBN 0-19-560686-8.

- Ghose, Rajeshwari (1996). The Tyāgarāja cult in Tamilnāḍu: A Study in Conflict and Accommodation. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 10. ISBN 978-81-208-1391-5.

- Sivaraman, Mythily (2006). Fragments of a Life: A Family Archive. Zubaan. p. 4. ISBN 978-81-89013-11-0.

- "Rediff On The Net, Movies: Meet Nethra Raghuraman, Supermodel and Bollywood wannabe". m.rediff.com. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- Mahadevan, Shankar (8 September 2013). "I am a Malayali grew up in Mumbai: Shankar Mahadevan" (Interview). Interviewed by John Brittas. Kairali TV. 0:38. Retrieved 4 January 2010 – via Kairali Archive on YouTube.

Interviewer: You have some connection with Kerala in fact, your family migrated from Palakkad or something like that. Shankar Mahadevan: Yes, I am an Iyer from Palakkad actually

References

- Ghurye, G. S. (1991). Caste and Race in India. Bombay: Popular Prakashan. ISBN 0-8364-1837-9.

- W. Clothey, Fred (2006). Ritualizing on the Boundaries: Continuity and Innovation in the Tamil Diaspora. University of South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-57003-647-7.

- Pathmanathan (1978). The Kingdom of Jaffna. Arul M. Rajendran.

- Fuller, C. J.; Narasimhan, Haripriya (2008). From Landlords to Software Engineers: Migration and Urbanization among Tamil Brahmans. London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Zvelebil, Kamil (1973). The Smile of Murugan on Tamil Literature of South India. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-03591-5.

- Zvelebil, Kamil V. (1992). Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-09365-6.

- Ghosh, G. K.; Ghosh, Shukla (2003). Brahmin Women. Firma KLM. ISBN 9788171021079.

Further reading

- Pandian, M. S. S. Pandian (2007). Brahmin & Non-Brahmin : genealogies of the Tamil political present. ISBN 978-8178241623.

- K. Duvvury, Vasumathi (1991). Play, Symbolism, and Ritual: A Study of Tamil Brahmin Women's Rites of Passage (American University Studies Series XI, Anthropology and Sociology) (Hardcover). Peter Lang Pub Inc. ISBN 978-0-8204-1108-8.

- Figueira, Dorothy Matilda (2002). Aryans, Jews, Brahmins: Theorizing Authority Through Myths of Identity. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-5531-9.

- Sharma, Rajendra Nath (1977). Brahmins Through the Ages: Their Social, Religious, Cultural, Political, and Economic Life. Ajanta Publications.

- Subramaniam, Kuppu (1974). Brahmin Priest of Tamil Nadu. Wiley. ISBN 0-470-83535-4.

- Yanagisawa, Haruka (1996). A Century of Change: Caste and Irrigated Lands in Tamilnadu, 1860s-1970s. Manohar. ISBN 978-81-7304-159-4.

- Pandian, Jacob (1987). Caste, Nationalism and Ethnicity: An Interpretation of Tamil Cultural History and Social Order. Popular Prakashan. ISBN 978-0-86132-136-0.

- Pathmanathan, Sivasubramaniam (1974). The Kingdom of Jaffna:Origins and early affiliations. Colombo: Ceylon Institute of Tamil Studies. pp. 171–173.