Phuket province

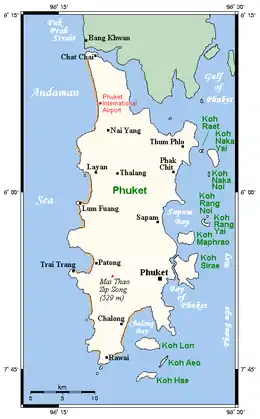

Phuket (/ˌpuːˈkɛt/; Thai: ภูเก็ต, [pʰūː.kèt] (![]() listen), Malay: Bukit or Tongkah; Hokkien:普吉; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Phó͘-kiat) is one of the southern provinces (changwat) of Thailand. It consists of the island of Phuket, the country's largest island, and another 32 smaller islands off its coast.[5] It lies off the west coast of mainland Thailand in the Andaman Sea. Phuket Island is connected by the Sarasin Bridge to Phang Nga province to the north. The next nearest province is Krabi, to the east across Phang Nga Bay.

listen), Malay: Bukit or Tongkah; Hokkien:普吉; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Phó͘-kiat) is one of the southern provinces (changwat) of Thailand. It consists of the island of Phuket, the country's largest island, and another 32 smaller islands off its coast.[5] It lies off the west coast of mainland Thailand in the Andaman Sea. Phuket Island is connected by the Sarasin Bridge to Phang Nga province to the north. The next nearest province is Krabi, to the east across Phang Nga Bay.

Phuket

ภูเก็ต | |

|---|---|

Phuket viewpoint | |

Flag .png.webp) Seal | |

Map of Thailand highlighting Phuket province | |

| Country | Thailand |

| Capital | Phuket (city) |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Narong Woonsiew (Since 15 Jun 2020)[1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 543 km2 (210 sq mi) |

| • Rank | Ranked 76th |

| Population (2019)[3] | |

| • Total | 416,582 |

| • Rank | Ranked 63rd |

| • Density | 755/km2 (1,960/sq mi) |

| • Rank | Ranked 4th |

| Human Achievement Index | |

| • HAI (2017) | 0.6885 "high" Ranked 1st |

| Time zone | UTC+7 (ICT) |

| Postal code | 83xxx |

| Calling code | 076 |

| ISO 3166 code | TH-83 |

| Website | phuket.go.th |

Phuket province has an area of 576 km2 (222 sq mi), somewhat less than that of Singapore, and is the second-smallest province of Thailand. The island was on one of the major trading routes between India and China, and was frequently mentioned in foreign ships' logs of Portuguese, French, Dutch, and English traders, but was never colonised by a European power. It formerly derived its wealth from tin and rubber and now from tourism.

Toponymy

There are several possible derivations of the relatively recent name "Phuket" (of which the digraph ph represents an aspirated /pʰ/). One theory is it is derived from the word Bukit (Jawi: بوكيت) in Malay which means "hill", as this is what the island appears like from a distance.

Phuket was formerly known as Thalang (ถลาง Tha-Laang), derived from the old Malay "telong" (Jawi: تلوڠ) which means "cape". The northern district of the province, which was the location of the old capital, still uses this name. In Western sources and navigation charts, it was known as Junk Ceylon or Junkceylon (a corruption of the Malay Tanjung Salang, i.e., "Cape Salang").[6]: 179

Geography

.jpg.webp)

Map of Phuket (beaches in brown) | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Andaman Sea |

| Coordinates | 7°53′24″N 98°23′54″E |

| Area | 576 km2 (222 sq mi) |

| Length | 50 km (31 mi) |

| Width | 20 km (12 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 529 m (1736 ft) |

| Highest point | Khao Mai Thao Sip Song |

| Administration | |

Thailand | |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 386,605 (2015) |

| Pop. density | 1,042/km2 (2699/sq mi) |

Phuket is the largest island in Thailand. It is located in the Andaman Sea in southern Thailand. The island is mostly mountainous with a mountain range in the west of the island from the north to the south. The mountains of Phuket form the southern end of the Phuket mountain range, which ranges for 440 kilometres (270 mi) from the Kra Isthmus.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Although some recent geographical works refer to the sections of the Tenasserim Hills in the isthmus as the "Phuket Range", these names are not found in classical geographic sources. Besides, the name Phuket is relatively recent having previously been named Jung Ceylon and Thalang. The highest elevation of the island is usually regarded as Khao Mai Thao Sip Song (Twelve Canes), at 529 metres (1,736 ft) above sea level. However, it has been reported by barometric pressure readings that there is an even higher elevation (with no apparent name), of 542 meters above sea level, in the Kamala hills behind Kathu waterfall.

The population was 249,446 in 2000, rising to 525,709 in the 2010 decennial census,[7] the highest growth rate of all provinces nationwide at 7.4 percent annually. Some 600,000 people reside on Phuket currently,[8] among them migrants, international ex-pats, Thais registered in other provinces, and locals. The registered population, however, includes only Thais who are registered in a thabian ban or house registration book, which most are not, and at the end of 2012 was 360,905 persons.[9]

Phuket is approximately 863 kilometres (536 mi) south of Bangkok and covers an area of 543 square kilometres (210 sq mi) excluding small islets. Other islands are: Ko Lone 4.77 square kilometres (1.84 sq mi), Ko Maprao 3.7 square kilometres (1.4 sq mi), Ko Naka Yai 2.08 square kilometres (0.80 sq mi), Ko Racha Noi 3.06 square kilometres (1.18 sq mi), Ko Racha Yai 4.5 square kilometres (1.7 sq mi), and the second biggest, Ko Sire 8.8 square kilometres (3.4 sq mi).

The island's length, from north to south, is 48 kilometres (30 mi) and its width is 21 kilometres (13 mi).[10]

Forest, rubber, and palm oil plantations cover 60 percent of the island. The west coast has several sandy beaches. The east coast beaches are more often muddy. Near the southernmost point is Laem Phromthep (Thai: แหลมพรหมเทพ, "Brahma's Cape"), a popular viewpoint. In the mountainous north of the island is the Khao Phra Thaeo No-Hunting Area, protecting more than 20 km2 of the rainforest. The three highest peaks of this reserve are the Khao Prathiu (384 metres (1,260 ft)), Khao Bang Pae 388 metres (1,273 ft), and Khao Phara 422 metres (1,385 ft). The Sirinat National Park on the northwest coast was established in 1981 to protect an area of 90 square kilometres (35 sq mi) (68 kilometres (42 mi) marine area), including the Nai Yang Beach where sea turtles lay their eggs.[11] The total forest area is 113 km2 (44 sq mi) or 20.6 percent of provincial area.[12]

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification, Phuket features a tropical monsoon climate (Am). Due to its proximity to the equator, in the year, there is little variation in temperatures. The city has an average annual high of 32 °C (90 °F) and an annual low of 25 °C (77 °F). Phuket has a dry season that runs from December to March and a wet season that covers the remaining eight months. However, like many cities that feature a tropical monsoon climate, Phuket sees some precipitation even during its dry season. Phuket averages roughly 2,200 millimetres (87 in) of rain.

| Climate data for Phuket (Mueang Phuket district) (1981-2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 36.3 (97.3) |

36.7 (98.1) |

37.8 (100.0) |

37.8 (100.0) |

37.8 (100.0) |

35.8 (96.4) |

35.0 (95.0) |

35.5 (95.9) |

35.0 (95.0) |

35.3 (95.5) |

34.8 (94.6) |

34.2 (93.6) |

37.8 (100.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 32.7 (90.9) |

33.6 (92.5) |

34.0 (93.2) |

33.9 (93.0) |

32.8 (91.0) |

32.4 (90.3) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.0 (89.6) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.7 (89.1) |

31.7 (89.1) |

32.5 (90.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 28.1 (82.6) |

28.7 (83.7) |

29.2 (84.6) |

29.4 (84.9) |

28.8 (83.8) |

28.6 (83.5) |

28.2 (82.8) |

28.1 (82.6) |

27.5 (81.5) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.7 (81.9) |

27.6 (81.7) |

28.3 (82.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 24.5 (76.1) |

24.9 (76.8) |

25.4 (77.7) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.6 (78.1) |

25.5 (77.9) |

25.1 (77.2) |

25.3 (77.5) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.7 (76.5) |

24.4 (75.9) |

25.0 (77.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 19.5 (67.1) |

18.6 (65.5) |

20.0 (68.0) |

20.5 (68.9) |

21.2 (70.2) |

21.9 (71.4) |

20.5 (68.9) |

21.1 (70.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

20.5 (68.9) |

20.3 (68.5) |

18.4 (65.1) |

18.4 (65.1) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 30.3 (1.19) |

23.9 (0.94) |

73.5 (2.89) |

142.9 (5.63) |

259.5 (10.22) |

213.3 (8.40) |

258.2 (10.17) |

286.8 (11.29) |

361.2 (14.22) |

320.1 (12.60) |

177.4 (6.98) |

72.4 (2.85) |

2,219.5 (87.38) |

| Average rainy days | 4.6 | 3.1 | 6.7 | 11.8 | 18.8 | 18.2 | 19.6 | 19.0 | 22.1 | 22.5 | 15.4 | 9.3 | 171.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 70 | 69 | 71 | 75 | 79 | 79 | 79 | 79 | 82 | 82 | 79 | 75 | 77 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 235.6 | 214.7 | 204.6 | 183.0 | 151.9 | 150.0 | 151.9 | 151.9 | 108.0 | 145.7 | 174.0 | 198.4 | 2,069.7 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 7.6 | 7.6 | 6.6 | 6.1 | 4.9 | 5.0 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 3.6 | 4.7 | 5.8 | 6.4 | 5.7 |

| Source 1: Thai Meteorological Department[13]: 27 | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Office of Water Management and Hydrology, Royal Irrigation Department (sun and humidity)[14]: 116 | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Phuket (Phuket International Airport) (1981-2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 35.5 (95.9) |

38.5 (101.3) |

37.5 (99.5) |

37.6 (99.7) |

37.7 (99.9) |

35.0 (95.0) |

34.2 (93.6) |

34.8 (94.6) |

34.4 (93.9) |

33.9 (93.0) |

36.1 (97.0) |

33.5 (92.3) |

38.5 (101.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 32.1 (89.8) |

33.1 (91.6) |

33.6 (92.5) |

33.4 (92.1) |

32.2 (90.0) |

31.7 (89.1) |

31.3 (88.3) |

31.2 (88.2) |

30.7 (87.3) |

30.8 (87.4) |

31.1 (88.0) |

31.2 (88.2) |

31.9 (89.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 27.0 (80.6) |

27.7 (81.9) |

28.3 (82.9) |

28.6 (83.5) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.3 (82.9) |

27.9 (82.2) |

28.0 (82.4) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.0 (80.6) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.7 (80.1) |

27.7 (81.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 22.6 (72.7) |

22.8 (73.0) |

23.4 (74.1) |

24.2 (75.6) |

24.7 (76.5) |

24.9 (76.8) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.9 (76.8) |

24.2 (75.6) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.5 (74.3) |

22.9 (73.2) |

23.9 (75.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 17.9 (64.2) |

17.1 (62.8) |

18.5 (65.3) |

20.2 (68.4) |

19.5 (67.1) |

19.6 (67.3) |

20.2 (68.4) |

18.9 (66.0) |

19.0 (66.2) |

20.8 (69.4) |

17.0 (62.6) |

18.9 (66.0) |

17.0 (62.6) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 36.2 (1.43) |

27.2 (1.07) |

100.3 (3.95) |

154.0 (6.06) |

281.5 (11.08) |

256.8 (10.11) |

261.5 (10.30) |

329.8 (12.98) |

399.1 (15.71) |

353.4 (13.91) |

207.8 (8.18) |

67.4 (2.65) |

2,475 (97.43) |

| Average rainy days | 6.2 | 4.1 | 7.9 | 12.9 | 20.2 | 18.9 | 20.3 | 20.2 | 22.8 | 23.3 | 16.6 | 10.0 | 183.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76 | 74 | 76 | 80 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 84 | 86 | 83 | 79 | 81 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 198.4 | 180.8 | 201.5 | 183.0 | 155.0 | 150.0 | 155.0 | 114.7 | 108.0 | 108.5 | 138.0 | 179.8 | 1,872.7 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 6.4 | 6.4 | 6.5 | 6.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 4.6 | 5.8 | 5.1 |

| Source 1: Thai Meteorological Department[13]: 27–28 | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Office of Water Management and Hydrology, Royal Irrigation Department (sun and humidity)[14]: 117 | |||||||||||||

History

.jpg.webp)

16th–18th century: European contact

The Portuguese explorer Fernão Mendes Pinto arrived in Siam in 1545. His accounts of the country go beyond Ayutthaya and include a reasonably detailed account of ports in the south of the Kingdom as well. Pinto was one of the first European explorers to detail Phuket in his travel accounts. He referred to the island as "Junk Ceylon", a name the Portuguese used for Phuket Island in their maps, mentioning the name seven times in his accounts. Pinto said that Junk Ceylon was a destination port where trading vessels made regular stops for supplies and provisions. However, during the mid-16th century, the island was in decline due to pirates and often rough and unpredictable seas, which deterred merchant vessels from visiting the island. Pinto mentioned several other notable port cities in his accounts, including Patani and Ligor, which is modern-day Nakhon Si Thammarat.[15]

In the 17th century, the Dutch, English and, after the 1680s, the French, competed for the opportunity to trade with Junk Ceylon, which was a rich source of tin. In September 1680, a ship of the French East India Company visited the island and left with a full cargo of tin.[15]

A year or two later, the Siamese King Narai, seeking to reduce Dutch and English influence, named as governor a French medical missionary, Brother René Charbonneau, a member of the Siam mission of the Société des Missions Étrangères. Charbonneau remained as governor until 1685.[16]

In 1685, King Narai confirmed the French tin monopoly in Phuket to their ambassador, the Chevalier de Chaumont.[6]: 179 Chaumont's former maître d'hôtel, Sieur de Billy, was named governor of the island.[6]: 50 However, the French were expelled from Siam after the 1688 Siamese revolution. On 10 April 1689, Desfarges led an expedition to re-capture Thalang to restore French control in Siam.[17] His occupation of the island led to nothing, and Desfarges returned to Puducherry in January 1690.[6]: 185

1785: Burmese invasion

Before the Burmese attacked Thalang in 1785 during the "Nine Armies' Wars", Francis Light, a British East India Company captain (and later founder of Penang), who had been based on the island for some years, notified the local administration that he had observed Burmese forces preparing to attack.[18] The island's military governor had just died, so the Burmese thought that it could be easily seized. Than Phu Ying Chan, the widow of the recently deceased governor, and her sister Mook (คุณมุก) ordered the women of the island to dress as soldiers and take positions on the Thalang city walls. The Burmese called off their attack due to the perceived strength of the defences. Short of supplies, they retreated. After a month-long siege of the capital city, the Burmese were forced to retreat on 13 March 1785. The two women became local heroines, receiving the royal titles Thao Thep Kasattri and Thao Si Sunthon from a grateful King Rama I.[5]

The seal of Phuket is a depiction of the Two Heroines Monument along Highway 402 in Phuket. This commemorates the sisters[19] The seal is a circle surrounded by a kranok pattern[20] and has been used since 1985.

19th–20th centuries

During the reign of King Chulalongkorn (Rama V) from 1 October 1868 to 23 October 1910, Phuket became the administrative centre of the tin-producing southern provinces. His reign was characterized by the modernization of Siam, governmental and social reforms, and territorial concessions to the British and French. As Siam was threatened by Western expansionism, Chulalongkorn managed to save Siam from colonization.

In 1876, mining laborers in Phuket and nearby provinces formed a rebellion. This was due to the low tin price, the government's tight fiscal policy, and Chinese laborers are not treated fairly.

In 1933 Monthon Phuket (มณฑลภูเก็ต) was dissolved and Phuket became a province.[21]

2004 tsunami

On 26 December 2004, Phuket and other nearby areas on Thailand's west coast suffered damage when they were struck by a tsunami caused by the Indian Ocean earthquake. The waves destroyed several highly populated areas in the region, killing up to 5,300 people in Thailand, and two hundred thousand more throughout the Asian region.[22] Some 250 were reported dead in Phuket, including foreign tourists. Almost all of the major beaches on the west coast of Phuket, especially Kamala, Patong, Karon, and Kata sustained major damage, with some damage caused to resorts and villages on the island's southern beaches. Thailand's hardest-hit area was the Takua Pa District of Phang Nga province north of Phuket, where a thousand or more Burmese workers building new beach resorts died.[23][24] In December 2006, Thailand launched the first of 22 tsunami-detection buoys to be positioned around the Indian Ocean as part of a regional warning system. The satellite-linked deep-sea buoys float 1,000 km (620 mi) offshore, roughly midway between Thailand and Sri Lanka.[25]

Demographics

.jpg.webp)

As with most of Thailand, the majority of the population is Buddhist, but there is a significant number of Muslims (20 percent) in Phuket, mainly descendants of the island's original Austronesian peoples. Among the Muslims, many are of Malay descent.[26][27] People of Chinese ancestry make up an even larger population, many of whom are descendants of the tin miners who migrated to Phuket during the 19th century.[28] Peranakans, known as "Phuket Babas" in the local tongue, constitute a fair share of Chinese community members, particularly among those who have family ties with the Peranakans of Penang and Malacca.[29]

Phuket provincial population in the preliminary count of the 2010 census was counted to be 525,018 people, including some 115,881 expatriates, or 21.1 per cent of the population. However, it is admitted this is inaccurate since the Phuket Provincial Employment Office currently records for more than 64,000 Burmese, Lao and Cambodian workers legally residing on the island.[30] The Thai census figure for 2015 shows a population of 386,605 persons.[31]

The number of people on Phuket island swells to over a million during the high season, as tourists, mainly from Western Europe, China, Russia, and the United States flock to Phuket around Christmas.

Religion

Administrative divisions

Provincial government

Phuket is divided into three districts (amphoe), which are further divided into 17 subdistricts (tambon), and 103 villages (muban).

- Mueang Phuket

- Kathu

- Thalang

Local government

As of 26 November 2019 there are:[33] one Phuket Provincial Administration Organisation (ongkan borihan suan changwat) and 12 municipal (thesaban) areas in the province. Phuket has city (thesaban nakhon) status. Kathu and Patong have town (thesaban mueang) status. Further 9 subdistrict municipalities (thesaban tambon). The non-municipal areas are administered by 6 Subdistrict Administrative Organisations - SAO (ongkan borihan suan tambon).[3]

Economy

.jpg.webp)

Tin mining was a major source of income for the island from the 16th century until petering out in the 20th century. In modern times, Phuket's economy has rested on two pillars: rubber tree plantations (making Thailand the biggest producer of rubber in the world[34]) and tourism.[35]

Since the 1980s, the sandy beaches on the west coast of the island have been developed as tourist destinations, with Patong, Karon, and Kata being the most popular. Since the 2004 tsunami, all damaged buildings and attractions have been restored. Phuket is being intensely developed, with many new hotels, apartments, and houses under construction.

In July 2005, Phuket was voted one of the world's top five retirement destinations by Fortune Magazine.[36]

In 2017, Phuket received about 10 million visitors, most of them foreign, with China the leading contributor. Tourists generated some 385 billion baht in revenues, nearly 14 percent of the 2.77 trillion baht earned by the nation as a whole.[37]

The first half of 2019 saw a dip in the number of tourists visiting Phuket, driving lower hotel occupancy rates and leading to increased price competition. RevPAR (revenue per available room) is down. A decline in the number of tourists, combined with an oversupply of hotel rooms, is the root of the problem. Despite falling numbers, the Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT) claims that tourism revenues have risen by 3.1% in the first half of 2019.

It is unclear how many hotel rooms Phuket has available. Oxfam says it has 60,000 hotel rooms for its 9.1 million annual visitors.[38]: 7 The Bangkok Post in September 2019 reported that Phuket has 600 hotels with 40,000 rooms.[39] Three weeks earlier it said that Phuket had 93,941 hotel rooms available, excluding villas and hostels, with an additional 15,000 projected to become available by 2024.[40]

Transportation

- Air

Phuket International Airport (HKT) commenced a 5.7 billion baht (US$185.7 million) expansion in September 2012, scheduled for completion on 14 February 2016. The airport will increase its annual handling capacity from 6.5 million to 12.5 million passengers, and add a new international terminal.[41]

- Rail

There is currently no rail line to Phuket. Trains run to Surat Thani and Khiri Rat Nikhom 230 km away.

- City transit

Songthaews are a common mode of transport in Phuket. Phuket's songthaews are larger than those found in other areas of Thailand. Songthaews are the cheapest mode of transportation from town to town. They travel between the town and the beaches. There are also conventional bus services and motorbike taxis. The latter are found in large numbers in the main town and at Patong Beach. Traditional tuk-tuks have been replaced by small vans, mostly red, with some being yellow or green. Car taxis in Phuket are quite expensive and charge flat rates between towns. Privately run buses are available from the airport to Phuket Town and major beaches. It is often recommended by locals to take the ride-share company, Grab.

- Bus

Phuket's Bus Station 2 BKS Terminal is the long-distance arrivals hub for buses to and from Bangkok and other major Thai cities and provinces. Located four kilometres to the north of Phuket's town centre and port, the complex is large and modern, linking with transportation by tuk-tuk, metered taxi, motorcycle taxi, songthaew, or local bus to the island's beaches and resorts. There are daily scheduled buses from private and government-run companies going to Phuket from Bangkok's Mo Chit and Southern terminal stations.

- Tram

The Mass Rapid Transit Authority of Thailand (MRTA) announced in 2018 that bidding to construct a 60-kilometer-long, 23-station tram network in Phuket will commence in 2020. The 39 billion baht tram is part of the government's Private-Public-Partnership (PPP) plan which ensures it will be fast-tracked. The planned route stretches from Takua Thung District in Phang Nga province to Chalong in Phuket. Phase one will connect Phuket International Airport with Chalong, about 40 kilometres. It will take three years to complete.[42]

- Ferry

There are daily ferry boats that connect Phuket to neighboring islands Phi Phi and Koh Lanta. Ferries depart daily from Rassada Pier and Tonsai Pier, with service expanding each year. The average price for a one-way ticket ranges from 300 THB to 1500 THB.[43][44]

Health

6 hospitals exist in Phuket. The main hospital in Phuket operated by the Ministry of Public Health is Vachira Phuket Hospital, with smaller hospitals at Thalang and Patong. 3 Private hospitals exist which are Phuket International Hospital, Bangkok Hospital Phuket, and Mission Hospital Phuket.

Human achievement index 2017

| Health | Education | Employment | Income |

| 5 | 4 | 29 | 4 |

| Housing | Family | Transport | Participation |

|

|

|

|

| 65 | 14 | 2 | 71 |

| Province Phuket, with an HAI 2017 value of 0.6885 is "high", occupies place 1 in the ranking. | |||

Since 2003, United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in Thailand has tracked progress on human development at the sub-national level using the Human achievement index (HAI), a composite index covering all the eight key areas of human development. The National Economic and Social Development Board (NESDB) has taken over this task since 2017.[4]

| Rank | Classification |

| 1 - 15 | "high" |

| 16 - 30 | "somewhat high" |

| 31 - 45 | "average" |

| 45 - 60 | "somewhat low" |

| 61 - 77 | "low" |

| Map with provinces and HAI 2017 rankings |

|

Sport

In 2009, the club is formed as Phuket F.C., nicknamed The Southern Sea Kirins, and admitted to the Regional League South Division. Club home games are to be played at Surakul Stadium. Sirirak Konthong was named as the first-ever coach of Phuket. In 2010 Phuket won the Southern Regional Division 2 and finished 2nd in the Division 2 Champions League after losing to Buriram FC in the final anyway the club was promoted to 2011 Thai Division 1 League. In 2009, the club is formed as Phuket F.C., sports_nicknamed The Southern Sea Kirins, and admitted to the Regional League South Division. Club home games are to be played at Surakul Stadium. Sirirak Konthong was named as the first-ever coach of Phuket. In 2010 Phuket won the Southern Regional Division 2 and finished second in the Division 2 Champions League after losing to Buriram FC in the final anyway the club was promoted to 2011 Thai Division 1 League. In 2015, the club is relegated to 2016 Regional League Division 2 Southern Region.

In 2017, Phuket F.C. decided to dissolve the club due to financial problems about unfair contract cancellation.[45]

In 2018, Phuket F.C. collapsed and combined with Banbueng F.C.[46] In 2019 the club was renamed to Phuket City.[47] However, the club was renamed back to Banbueng F.C. due to the take over of Banbueng's boards again. They have moved their ground back to IPE Chonburi Stadium in Chonburi too.

In 2020, Patong City participated 2020–21 Thai League 3 Southern Region for, the first time in the professional league of club history.[48]

Attractions

- Two Heroines Monument (อนุสาวรีย์วีรสตรี), is the monument in Thalang District, a memorial statue of Thao Thep Kasattri (Kunying Jan) and Thao Sri Sunthon (Mook), who rallied islanders in 1785 to repel Burmese invaders.[49]

- Thalang National Museum (พิพิธภัณฑสถานแห่งชาติ ถลาง), established in 1985, on the 200th anniversary of the Thalang War.[50]

- Hat Karon (หาดกะรน) is the second largest of Phuket's tourist beaches, approximately 20 kilometres (12 mi) from town.

- Wat Chalong (วัดฉลองหรือวัดไชยธาราราม) has a statue of Luang Pho Cham, who helped the people of Phuket put down the Angyee in 1876 during the reign of Rama V.

- Old Phuket Town in Phuket town, around Thalang, Dibuk, Yaowarat, Phang Nga, and Krabi Roads. The architecture is Sino-Portuguese-style.

- On On Hotel in downtown Phuket Town which was shown in the movie ‘The Beach’ with Leonardo DiCaprio in 2000.

- Aquaria Phuket opened on August 24, 2019.[51]

- Freedom Beach, one of the prettiest beaches on the island, with incredibly soft white sand and clear blue waters. It is just a few minutes away from Patong Beach, accessible by boat or hiking.

- A day trip to the Phi Phi Islands takes about 50 minutes when departing from Phuket by speedboat and these islands are a beautiful sight worth taking in.

Local culture

- Thao Thep Krasattri and Thao Si Sunthon Fair (งานท้าวเทพกระษัตรี - ท้าวศรีสุนทร) is held on March 13 every year to commemorate the two heroines who rallied the Thalang people to repel Burmese invaders.

- Vegetarian Festival or Nine Emperor gods Festival (Hokkien Chinese language: 九皇勝會, Kiú-Hông Sēng-Huē or 九皇爺, Kiú-Hông Iâ; Phuket Chinese people Call 食菜節, Tsia̍h-tshài (เทศกาลกินเจ (กินผัก-เจี๊ยะฉ่าย)), is held on the first day of the ninth Chinese lunar month (end-Sep or early-Oct). Phuket islanders of Chinese ancestry commit themselves to a nine-day vegetarian diet, a form of purification believed to help make the forthcoming year trouble-free. The festival is marked by several ascetic displays, including fire-walking and ascending sharp-bladed ladders.[52]

- Ghost Festival or Phóo-tōo Festival (Hokkien Chinese language: 普渡節; Full name is Û-lân-phûn Sēng-Huē (Hokkien Chinese language: 盂蘭盆勝會)), is held on the middle day of the seventh Chinese lunar month. Intrinsic to the Ghost Festival is ancestor worship. Activities include preparing food offerings, burning incense, and burning joss paper, a papier-mâché form of material items such as clothes, gold, and other goods for the visiting spirits. Elaborate meals (often vegetarian) are served with empty seats for each of the deceased in the family. Other festivities may include, buying and releasing miniature paper boats and lanterns on water, which signifies giving direction to lost souls.

- Phuket King's Cup Regatta (งานแข่งเรือใบชิงถ้วยพระราชทาน) is held every December. The Kata Beach Resort hosts yachtsmen, largely from neighbouring countries who compete for trophies.[53]

- Laguna Phuket Triathlon (ลากูน่าภูเก็ตไตรกีฬา) is held each December. The triathlon (a 1,800 metres (5,900 ft) swim, a 55 kilometres (34 mi) bike race and a 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) run and a 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) fun run) attracts athletes from all over the world.[54]

- Phuket Travel Fair (เทศกาลเปิดฤดูการท่องเที่ยวจังหวัดภูเก็ต), starting 1 November, is usually called the Patong Carnival, from the place where celebrations happen. Colourful parades, sports events, and beauty competitions for foreign tourists are major activities. A popular festival, the Patong Carnival opening drew over 30,000 foreign and Thai tourists.[55]

- Chao Le (Sea Gypsy) Boat Floating Festival (งานประเพณีลอยเรือชาวเล) falls during the middle of the sixth and eleventh lunar months yearly. The sea gypsy villages at Rawai and Sapam hold their ceremonies on the 13th; Ko Si-re celebrates on the 14th; and Laem La (east of the bridge on Phuket's northern tip) on the 15th. Ceremonies, which centre on the setting of small boats adrift similar to the Thai festival of Loi Krathong, are held at night and their purpose is to drive away evil and bring good luck.

- Phuket Bike Week is the biggest motorbike event in Asia. Motorcyclists with their motorcycles and spectators from many countries like France join this event in every year. The event highlights include a motorcycle exhibition, bike parades "Ride for Peace", custom bike contests, live entertainment, Mr. Phuket Bike Week competition, bike accessories and apparel from local and international venders.[56][57]

Twin towns and sister cities

Phuket province has a number of sister cities. They are:

Gallery

Monument to Thao Thep Kasattri and Thao Sri Sunthon in Phuket

Monument to Thao Thep Kasattri and Thao Sri Sunthon in Phuket Kata Noi Beach

Kata Noi Beach.jpg.webp) Big Buddha monument overlooking Phuket

Big Buddha monument overlooking Phuket Patong Beach

Patong Beach Ko Hae Island

Ko Hae Island Phromthep Cape and Kaeo Yai Island

Phromthep Cape and Kaeo Yai Island.jpg.webp) Mai Khao, Thalang District

Mai Khao, Thalang District

References

- "ประกาศสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี เรื่อง แต่งตั้งข้าราชการพลเรือนสามัญ" [Announcement of the Prime Minister's Office regarding the appointment of civil servants] (PDF). Royal Thai Government Gazette. 137 (Special 142 Ngor). 3. 17 June 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- Advancing Human Development through the ASEAN Community, Thailand Human Development Report 2014, table 0:Basic Data (PDF) (Report). United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Thailand. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-974-680-368-7. Retrieved 17 January 2016, Data has been supplied by Land Development Department, Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, at Wayback Machine.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - "รายงานสถิติจำนวนประชากรและบ้านประจำปี พ.ศ.2561" [Statistics, population and house statistics for the year 2018]. Registration Office Department of the Interior, Ministry of the Interior (in Thai). 31 December 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- Human achievement index 2017 by National Economic and Social Development Board (NESDB), pages 1-40, maps 1-9, retrieved 14 September 2019, ISBN 978-974-9769-33-1

- "Phuket". Amazing Thailand. Tourism Authority of Thailand. Archived from the original on 2013-07-05. Retrieved 2015-01-03.

- Smithies, Michael (2002), Three military accounts of the 1688 "Revolution" in Siam, Itineria Asiatica, Orchid Press, Bangkok, ISBN 974-524-005-2

- "Thailand & Phuket Census 2010" (PDF). National Statistical Office Thailand. National Statistical Office Thailand. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- Administrative Divisions of Thailand: Provinces and Districts – Statistics and Maps by City Population Archived 2012-01-07 at the Wayback Machine. Citypopulation.de (2011-11-12). Retrieved on 2013-08-25.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-10-27. Retrieved 2013-10-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Phuket Town Treasure Map Archived 2010-01-28 at the Wayback Machine www.phuket-maps.com

- "Sirinart National Park". Amazing Thailand. Tourist Authority of Thailand (TAT). Archived from the original on 2015-01-15. Retrieved 2015-01-16.

- "ตารางที่ 2 พี้นที่ป่าไม้ แยกรายจังหวัด พ.ศ.2562" [Table 2 Forest area Separate province year 2019]. Royal Forest Department (in Thai). 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2021, information, Forest statistics Year 2019

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - "Climatological Data for the Period 1981-2010". Thai Meteorological Department. Archived from the original on 31 July 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- "ปริมาณการใช้น้ำของพืชอ้างอิงโดยวิธีของ Penman Monteith (Reference Crop Evapotranspiration by Penman Monteith)" (PDF) (in Thai). Office of Water Management and Hydrology, Royal Irrigation Department. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- "คำว่าถลาง".

- Ahmad, Abu Talib; Tan, Liok Ee (2 May 2018). New Terrains in Southeast Asian History. Ohio University Press. ISBN 9780896802285. Retrieved 2 May 2018 – via Google Books.

- A History of South-east Asia p. 350, by Daniel George Edward Hall (1964) St. Martin's Press

- Simmonds, E.H.S. (December 1965). "Francis Light and The Ladies of Thalang". Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. Cambridge University Press for SOAS, University of London. 38 (2 (208)): 592–619. ISSN 0126-7353. JSTOR 611568.

- ตราประจำจังหวัด. Retrieved 22 Oct 2013 from http://www.phuket.go.th Archived 2013-11-19 at the Wayback Machine

- กุศล เอี่ยมอรุณ, จตุพร มีสกุล. Phuket. Bangkok: Sarakadee Press.

- "จดหมายเหตุรายวันจดรายงานราชการของข้าหลวงเทศาภิบาลมณฑลภูเก็ต ร.ศ. 121".

- Puavilai, Wilai (2005-01-29). "Tsunami disaster in Thailand, ICU experience" (PDF). World Health Organisation (WHO). WHO Tsunami & Health Situation Report 31. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- Chankaew, Prapan; Sagolj, Damir (2014-12-23). "Hundreds Of Victims Of The 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami Have Still Not Been Identified". Business Insider. Reuters. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- Tang, Alisa (2005-06-27). "Forgotten Burmese Victims of Tsunami Rebuild Thai Resorts". The Irrawaddy. AP. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- "NOAA Provides First Tsunami Detection Buoy for the Indian Ocean". NOAA. Archived from the original on 2013-03-06. Retrieved 2012-06-17.

- Tristan Jones (1999). To Venture Further. Sheridan House, Inc. p. 53. ISBN 1-57409-064-X.

- Walter Armstrong Graham (1913). Siam: A Handbook of Practical, Commercial, and Political Information. F. G. Browne. pp. 115, 124.

- Annabelle Gambe (2000). Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurship and Capitalist Development in Southeast Asia. LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster. p. 108. ISBN 3-8258-4386-6.

- D'Oliveiro, Michael (2007-03-31). "The Peranakan Trail". The Star Online. The Star (Malaysia). Archived from the original on 2015-07-05. Retrieved 2015-01-16.

- Phuket News: Phuket population "only" 525,000: Census Archived 2011-05-12 at the Wayback Machine. Phuketgazette.net. Retrieved on 2013-08-25.

- "รายงานสถิติจำนวนประชากรและบ้านประจำปี พ.ศ.2558". Department of Provincial Administration (DOPA). Archived from the original on 8 September 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- "Phuket: City of Gastronomy during 2017–2021" (PDF). Phuket Province. 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- "Number of local government organizations by province". dla.go.th. Department of Local Administration (DLA). 26 November 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

41 Phuket: 1 PAO, 1 City mun., 2 Town mun., 9 Subdistrict mun., 6 SAO.

- "Top rubber producers again eye joint moves to arrest sliding prices". Reuters. 6 February 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-09-12. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- "Phuket's Economy". Archived from the original on 2017-02-02.

- "Paradise Found: Where to Retire Abroad". CNN. July 11, 2005. Archived from the original on February 12, 2009.

- Sritama, Suchat (16 July 2018). "A Fatal Wake-up Call". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- Sarosi, Diana (October 2017). Tourism's Dirty Secret; The Exploitation of Hotel Housekeepers (PDF). Oxfam Canada. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- Worraachaddejchai, Dusida (13 September 2019). "Mice held back by Phuket's regulations". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Kasemsuk, Narumon (5 August 2019). "Phuket loses lustre". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- "An evergreen dream". TTGmice. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- "Bidding date set for 2020 for Phuket's new tram network". Bangkok Post. 18 July 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- "Koh Lanta to Phuket ferry tickets, compare times and prices". www.directferries.com. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- "Phuket to Phi Phi Ferry | Phuket to Phi Phi Speedboat". phuketharbour.com. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- "ภูเก็ตยุบสโมสรหลังฟีฟ่าสั่งจ่ายค่าปรับ83ล้านให้อดีตแข้งต่างชาติ".

- "ภูเก็ตเฮ!นายทุนยาสูบเทคบ้านบึง หนุนลุยที3ใช้ชื่อภูเก็ต ซิตี้".

- "เปิดตัวยิ่งใหญ่! สโมสร "ภูเก็ต ซิตี้" มั่นใจเลื่อนชั้นภายในปีนี้ ดันภูเก็ตเป็นเมืองแห่งกีฬา". 14 February 2019.

- "ทีมฟุตบอลน้องใหม่ของคนภูเก็ต "ป่าตอง ซิตี้" ก้าวสู่ลีกอาชีพครั้งแรก". 14 February 2020.

- "Two Heroines Monument". Amazing Thailand. Tourism Authority of Thailand. Archived from the original on 2015-01-03. Retrieved 2015-01-03.

- "Phuket Museums". Amazing Thailand. Tourist Authority of Thailand. Archived from the original on 2014-02-28. Retrieved 2015-01-03.

- "BIGGEST AQUARIUM OPENS". Bangkok Post. 25 August 2019.

- "Vegetarian Festival, Phuket". Amazing Thailand. Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT). Archived from the original on 2018-05-02. Retrieved 2015-01-16.

- "Phuket King's Cup Regatta". Phuket King's Cup Regatta. Archived from the original on 2015-01-08. Retrieved 2015-01-03.

- "Laguna Phuket Triathlon". Challenge; Laguna-Phuket Tri-Fest. Archived from the original on 2015-01-11. Retrieved 2015-01-16.

- "Phuket Carnival 2018 kicks off in a blaze of colour". Phuket: The Thaiger. 2018-11-01. Retrieved 2018-11-01.

- "Phuket Bike Week: 11-19 April 2015". Archived from the original on 29 September 2015. Retrieved 2015-09-28.

- "22nd anniversary PHUKET BIKE WEEK 2016 on April 8-16, 2016 - at Patong Beach and Phuket Town, Phuket, Thailand". www.phuketbikeweek.com. Archived from the original on 2015-09-29. Retrieved 2015-09-28.

- "List of twinned cities" (PDF). Ministry of Urban Development, India. Archived from the original on 2011-07-17.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - "Sister Cities". Heinan Government. Archived from the original on 2010-07-16.

- "Nakhodka celebrates the day of twin-cities". Nakhodka City Administration. 2009-04-24. Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2010-07-13.

- "Phuket becomes sister city with Suining, China". Nakhodka City Administration. 2016-06-30. Archived from the original on 2017-02-02.

- "行政長官與泰國外長會面 澳門普吉府締結友好城市".

External links

- Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David: Phuket’s Historic Peranakan Community

Phuket travel guide from Wikivoyage

Phuket travel guide from Wikivoyage

.tif.png.webp)