Jurassic Park III

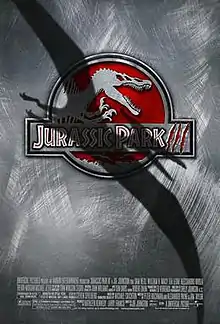

Jurassic Park III is a 2001 American science fiction action film.[3] It is the third installment in the Jurassic Park franchise and the final film in the original Jurassic Park trilogy, following The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997). The film stars Sam Neill, William H. Macy, Téa Leoni, Alessandro Nivola, Trevor Morgan, and Michael Jeter. It was written by Peter Buchman, Alexander Payne, and Jim Taylor, and was directed by Joe Johnston. It is the first film in the franchise to not be directed by Steven Spielberg, who served as executive producer, instead. It is also the franchise's first film to not be based on a novel by Michael Crichton, although the film includes characters and ideas by him, including scenes from his first novel Jurassic Park (1990). Like its predecessor, the film takes place on Isla Sorna, a fictional island of cloned dinosaurs located off Central America's Pacific coast. The film involves a divorced couple (portrayed by Macy and Leoni) who trick paleontologist Dr. Alan Grant (Neill) into helping them find their son (Morgan), who is missing on the island. Neill and Laura Dern reprised their roles from the first film, Jurassic Park (1993).

| Jurassic Park III | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Joe Johnston |

| Written by |

|

| Based on | Characters by Michael Crichton |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Shelly Johnson |

| Edited by | Robert Dalva |

| Music by | Don Davis |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 92 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $93 million[2] |

| Box office | $368.8 million[2] |

After the release of Spielberg's Jurassic Park, Joe Johnston expressed interest in directing a sequel. Although Spielberg returned to direct the first sequel, he gave Johnston permission to direct a possible third film. Universal Pictures announced a third film in June 1998, with a release scheduled for mid-2000. Craig Rosenberg wrote the first draft of the script, about teenagers becoming marooned on Isla Sorna. Johnston was announced as director in 1999, and Rosenberg's draft was rejected. A second draft, by Buchman, involved dinosaur attacks in various mainland locations, while a parallel story within the script would involve Alan Grant and others crash-landing on Isla Sorna. Around five weeks before the start of filming, Johnston and Spielberg rejected the second draft in favor of a simpler story idea suggested by David Koepp, the writer of the previous two films. Payne and Taylor were hired to rewrite the earlier script by Buchman, who made further revisions to their draft. The script also received uncredited work by John August. Filming lasted five months, and began in Hawaii on August 30, 2000, before moving to California. A final draft of the script was never completed during production, and Johnston considered quitting the project on a few occasions because of uncertainty about how the film would turn out. As with previous films, Jurassic Park III features a combination of computer-generated and animatronic dinosaurs, created respectively by Industrial Light & Magic and Stan Winston. Unlike the previous films, Jurassic Park III features a Spinosaurus as the main dinosaur antagonist, replacing the Tyrannosaurus rex. The same creature would then make its return in the fourth season of Jurassic World Camp Cretaceous twenty years later.

Jurassic Park III was theatrically released on July 18, 2001. Despite mixed reviews from critics, the film was successful at the box office, grossing $368 million worldwide. Nevertheless, it is the lowest-grossing installment in the series. The next film in the series, Jurassic World, was released in 2015, starting the Jurassic World trilogy. Neill and Dern reprised their roles in the 2022 film Jurassic World Dominion.

Plot

Twelve-year-old Eric Kirby and his mother's boyfriend, Ben Hildebrand, go parasailing near the restricted Isla Sorna.[lower-alpha 1] The boat's crew is killed by an unknown attacker, prompting Ben to detach the line before the vessel crashes into rocks. Eric and Ben drift towards the island.

Eight weeks later, paleontologist Dr. Alan Grant struggles to secure funding for his Velociraptor research, and rebuffs the public's obsession with the events on Isla Nublar.[lower-alpha 2] Grant discusses his research with longtime colleague Ellie, hypothesizing that Velociraptors were socially advanced beyond even primates. In Montana, his assistant, Billy Brennan, uses a three-dimensional printer to replicate a Velociraptor larynx.

Paul and Amanda Kirby, a seemingly wealthy couple, offer to fund Grant's research if he gives them an illegal aerial tour of Isla Sorna. Grant reluctantly agrees and flies there with Billy, the Kirbys' associates Udesky and Cooper, and their pilot Nash. Grant learns that the Kirbys plan to land; he protests, but Cooper knocks him unconscious. Grant awakens to find the plane has landed, and the group flees when a predator approaches the runway. As the group boards the plane, Cooper is left behind. The plane lifts off as a Spinosaurus emerges and devours Cooper. Nash hits the dinosaur, and the plane crashes into the jungle. The Spinosaurus attacks the plane and eats Nash, who has Paul's satellite phone. The survivors flee, only to encounter a Tyrannosaurus. The two dinosaurs fight, and the Spinosaurus kills the Tyrannosaurus as the humans escape.

Grant confronts the Kirbys, who reveal they are a middle-class divorced couple searching for their son Eric and Amanda's boyfriend Ben. Government agencies declined to help, so they deceived Grant and brought him along, mistakenly believing him to have experience on Isla Sorna. The group searches for Eric and Ben as they travel to the coast. They find Ben's corpse attached to the parasail which Billy takes. They also stumble upon a Velociraptor nest, and Billy secretly places two eggs in his bag.

They soon discover an InGen compound, where a Velociraptor attacks them, before vocalizing for its pack. The humans escape within a herd of Corythosaurus and Parasaurolophus, causing a stampede; Grant and Udesky are separated from the others. The Velociraptors trap Udesky and attempt to lure Paul, Amanda, and Billy from their place in a tree. Failing to coerce the group into rescuing Udesky, a Velociraptor kills him before the pack departs. Grant observes the pack communicating and suspects that they are searching for something; as he tries to slip away, they ambush him. Eric disrupts the pack with canisters of tear gas and brings Grant to an overturned supply truck where he has been taking shelter. The following morning, Grant and Eric reunite with Billy and the Kirbys; the group narrowly escapes the Spinosaurus.

Grant, suspicious of Billy, checks his bag and finds the Velociraptor eggs, which Billy reveals he planned to sell for funding. Grant decides to keep the eggs in the hopes that the Velociraptors may spare them if the eggs are returned. The group then unknowingly enters into an aviary filled with Pteranodons. A flock attacks the group and flies away with Eric. Billy rescues him using the parasail but is swarmed and seemingly killed. The group escapes the aviary but unintentionally leave the cage unlocked. They board a small barge and make their way down a river. That night, they retrieve the ringing satellite phone from the dung of the Spinosaurus. Grant contacts Ellie and tells her where they are, but the Spinosaurus attacks the barge. Fuel from the boat leaks into the water, and Grant ignites it using a flare gun, forcing the Spinosaurus to permanently flee.

The following day, the group arrive at the coast but are surrounded by the Velociraptor pack. Grant uses the replica larynx to confuse the pack and present their eggs. Upon hearing distant helicopters, the raptors reclaim their eggs and disappear into the jungle. The U.S. Navy lands on the beach, summoned by Ellie, and rescue the survivors. On a helicopter, they discover that Billy has also been rescued, albeit in a seriously injured state. They watch the newly escaped Pteranodons fly alongside them as they leave the island.

Cast

- Sam Neill as Dr. Alan Grant, a paleontologist

- William H. Macy as Paul Kirby, Amanda's ex-husband and Eric's father

- Téa Leoni as Amanda Kirby, Paul's ex-wife and Eric's mother

- Alessandro Nivola as Billy Brennan, Dr. Grant's assistant

- Trevor Morgan as Eric Kirby, Paul and Amanda's son

- Michael Jeter as Udesky, the Kirbys' mercenary associate

- John Diehl as Cooper, the Kirbys' secondary mercenary associate

- Bruce A. Young as Nash, the pilot of the group's airplane

- Laura Dern as Ellie, an author and paleobotanist who visited Isla Nublar with Alan in the first movie

- Taylor Nichols as Mark, Ellie's husband who works for the State Dept.

- Mark Harelik as Ben Hildebrand, Amanda's boyfriend who goes parasailing with Eric

- Julio Oscar Mechoso as Enrique Cardoso, the parasailing operator

- Blake Bryan as Charlie, Mark and Ellie's son

Production

When Steven Spielberg's film Jurassic Park was released in 1993, his friend Joe Johnston became interested in directing a potential sequel. While Spielberg expected to direct the first sequel, he agreed Johnston could direct a possible third film.[4][5][6] The second film, entitled The Lost World: Jurassic Park, includes a scene showing a Tyrannosaurus rampaging through San Diego; Spielberg had intended to use this scene for a third film but later decided to add it into the second film after realizing he probably would not direct another film in the series.[7] After the release of the second film in May 1997, Spielberg was busy with other projects; when asked about the possibility of a third Jurassic Park film, he responded that it would give him a tremendous headache to make it.[8] Spielberg had no intention of returning to the Jurassic Park series as a director,[9] stating that the films were difficult to make.[10] He had been satisfied with directing the previous films, and felt that the third film needed someone new to take over. After the release of the second film, Johnston again asked Spielberg about directing a Jurassic Park sequel.[11]

Pre-production

Universal Pictures announced the film in June 1998, with Spielberg as a producer. Michael Crichton, who wrote the Jurassic Park novels, was to collaborate with Spielberg to create a storyline and write a script,[12] although Johnston later said that Crichton had no involvement with the project.[6] The film was initially set for release in mid-2000.[12] Spielberg initially devised a story involving Dr. Alan Grant, who was discovered to have been living on one of InGen's islands. According to Johnston: "He'd snuck in, after not being allowed in to research the dinosaurs, and was living in a tree like Robinson Crusoe. But I couldn't imagine this guy wanting to get back on any island that had dinosaurs in it after the first movie".[13]

Craig Rosenberg, who previously wrote and directed Hotel de Love,[14] began writing the first draft of Jurassic Park III in June 1999.[6][15] Spielberg and Johnston were impressed by Rosenberg's prior work,[16] which included thriller screenplays for Spielberg's company DreamWorks.[17] Rosenberg's draft involved teenagers becoming marooned on Isla Sorna,[6][15] and it included a sequence involving the aquatic reptile Kronosaurus, which was not featured in the final film.[13][10] Another scrapped scene would involve characters on motorcycles trying to evade raptors.[18][19]

Johnston was announced as the film's director in August 1999, with Rosenberg still attached.[16] Spielberg gave complete creative freedom to Johnston, who said that Spielberg "has strongly pointed out that I shouldn't try to copy him".[20] Production was expected to begin in early 2000.[16][21] The previous films were shot in Hawaii, and the island of Kauai was the preferred filming location for the third film, although no decisions would be made until the finalization of the script.[14] Rosenberg's draft about teenagers on Isla Sorna was rejected in September 1999.[22] Johnston said it was "not a badly written script", but he felt that viewers would not want to see such a story,[6] also saying that it read like a bad episode of Friends.[22]

Buchman draft

Peter Buchman was hired to rewrite Rosenberg's draft, and did so going into early 2000.[23] Buchman's draft involves dinosaurs causing a series of mysterious killings on the mainland, followed by an investigation. The script also has a parallel story that involves Alan Grant, Billy, and a family crash-landing on Isla Sorna.[6][22]

The draft begins with a vacationing couple who go parasailing over Isla Sorna, becoming the latest tourists to go missing there. A representative for the U.S. State Department, Harlan Finch, goes to Costa Rica and meets environmentalist Simone Garcia, who informs him of a recent dinosaur attack. Meanwhile, Grant is seeking financial donors for a raptor research station that he wants to build on Isla Sorna. Finch offers Grant exclusive research rights to the island if he will help the U.S. government acquire jurisdiction over it. Grant agrees, and is scheduled to testify along with Simone at a hearing, to be held the next day in San José, Costa Rica.[23]

Grant also meets Paul Roby, a wealthy businessman who offers him a donation if he will host an aerial tour of Isla Sorna. Grant agrees, and they fly over the island prior to the hearing, along with Grant's graduate student Billy Hume and Paul's 12-year-old son Miles, a dinosaur enthusiast.[23][24][25] Also on the tour is Paul's bodyguard Cooper,[26][27][28] and Susan Brentworth, Paul's business associate and girlfriend. The plane is forced to land on the island after hitting an unidentified object. As it takes off again, it hits a Spinosaurus and crashes. The story would then alternate between the island and San José. The hearing would reveal that dinosaur attacks have taken place in various mainland locations, ranging from the Baja California Peninsula to Panama. Finch becomes concerned that the dinosaurs are breeding, thus posing a worldwide problem.[23]

The island scenes would largely play out the same as the final film, although the aviary and InGen laboratory sequences were much longer and more complex in this draft. Part of the script would involve the humans spending the night in the laboratory and making it their base of operations, although velociraptors would eventually sneak into the lab,[6][23] after Billy stole their eggs. The humans would escape on dirt bikes and later take refuge in treetops. Cooper would die to velociraptors while protecting Miles,[23] and Billy would die to a Pteranodon during the aviary sequence.[23][29] Near the end of the draft, the U.S. government sends in fighter jets to bomb the island and destroy its dinosaur population. In the process, Roby is spotted by a pilot and he and his family are rescued from the island. However, Grant refuses to leave and, in his final scene, retreats into the jungle, incorporating Spielberg's initial idea.[23]

These final scenes inspired the title Jurassic Park: Extinction, although the filmmakers decided against this name as it seemed to suggest a definitive end to the franchise. Johnston also considered it a vague title, with Extinction potentially referring to the dinosaurs, the human population, or Grant. The name was eventually simplified as Jurassic Park III. Johnston said that no one was "particularly fond" of the title "but you certainly knew what it meant".[23] Other potential titles included Jurassic Park: Breakout and The Extinction: Jurassic Park 3.[30]

Filming locations were scouted for this draft,[6] including Fiordland, New Zealand, which was once considered as a location for the previous film.[31][32][33] In March 2000, Maui, Hawaii, reportedly had been chosen instead of New Zealand.[34]

Casting and further rewrites

Sam Neill signed to the project in June 2000, reprising his role from the first film as Dr. Alan Grant.[35] Johnston later described Grant in the third film as being more cynical and sarcastic following the character's experience in the first film.[36] Neill was happy to return, as he felt his performance in the first film could have been better.[37] Hawaii was confirmed as a filming location for a three-week shoot,[38] and filming overall was expected to take 18 weeks. Filming was scheduled to begin by August 2000, with a projected release in July 2001.[35] William H. Macy originally turned down his role due to scheduling conflicts,[39] so filming was delayed by a month.[40] Macy had been working with Laura Dern on the 2001 film Focus, and she urged him to accept the role in Jurassic Park III.[41] Trevor Morgan and Téa Leoni were subsequently announced as cast members.[42]

Johnston felt that Buchman's draft was too complicated, particularly in getting Alan Grant back to an island of dinosaurs. When screenwriter David Koepp held discussions with Johnston, Koepp suggested the simpler "rescue mission" plot. Koepp had written the previous two films, but had no involvement in writing the script for Jurassic Park III.[5][6][22] In July 2000, about five weeks before filming began,[5][6] Johnston and Spielberg rejected the entire second script because they were dissatisfied with it; $18 million had already been spent on the film,[43] which had been storyboarded and budgeted. Some set-building had already begun, as well.[6] The rejection came after Johnston and Spielberg approved Koepp's story idea, believing it to be superior to the earlier story.[5][6][22] Many sequences from the second rejected draft, and some from the original draft, were incorporated into the final film as a way of salvaging the work that had been put into the project up to that point.[6][44] At the time, Utah's Dinosaur National Monument and a military base at Oahu were being considered as filming locations.[45][46]

Alexander Payne and Jim Taylor began rewriting Buchman's script in July 2000,[39][47] while Spielberg signed a deal with Universal to receive 20% of the film's profits.[48] Payne and Taylor were hired to improve the film's characters and story, as the script primarily consisted of action. They were surprised to receive the writing offer, as the project differed from past films on which they had worked, but Universal had been impressed with their rewrite on the studio's film Meet the Parents.[49][50][51] Payne and Taylor were not hardcore fans of the Jurassic Park franchise, although Taylor enjoyed its premise. The two writers watched the previous Jurassic Park films and spent the next four weeks writing their draft of the script.[51]

Payne and Taylor had previously written Citizen Ruth (1996), which starred Dern. She had also portrayed Ellie in the first Jurassic Park film. The character was absent from the previous Jurassic Park III script, so Payne and Taylor decided to write in a small part for Dern to reprise the role.[51] She was initially hesitant to reappear only for a cameo, so Spielberg suggested that Ellie have an important role in saving the characters on the island. Dern was convinced after learning that Payne and Taylor were working on the script.[23] In one draft, Neill and Dern's characters were a couple in the process of splitting up.[52] Johnston said: "I didn't want to see them as a couple anymore. For one thing, I don't think they look like a couple. It would be uncomfortable to still see them together. And Laura Dern doesn't look like she's aged for the past 15 years!"[22]

Buchman made subsequent revisions to the script,[5][47] and John August did uncredited work on it, as well.[53] Much of the humor added by Payne and Taylor was not used in the final film.[51] According to Payne: "We gave them a new script, and then we saw the movie, and it's all action. They took the rest out!"[49] Writing credit ultimately went to Buchman, Payne, and Taylor.[51] Johnston described the final film as simpler, faster-moving, and more intense than the earlier films.[54]

Filming

A final draft of the script was never completed during production.[6] While the first act was mostly in place, the middle portion of the script was not as complete, and the ending had yet to be written.[55][56] Principal photography began on August 30, 2000,[57][58][59] and it lasted five months.[60] Filming the script was a lengthy process because of technical preparations before scenes.[61] Macy criticized the project during filming.[9] Commenting on the slow pace of filming, Macy said "we would do a quarter-page, [or] some days, an eighth of a page. And that would be a full 12-hour day".[61] Johnston said that filming ultimately went over schedule by a few days, primarily because of weather and unexpected technical issues, although he was satisfied with how the schedule eventually turned out considering these issues.[62]

Macy also noted that executive producer Spielberg was not seen on set, despite a chair bearing his name that was always present, with Macy saying, "You don't know if it's a threat or a promise!"[62] Spielberg was busy creating the 2001 film A.I. Artificial Intelligence.[63] While Macy was impressed with the Jurassic Park III footage, he criticized the project for starting without a finished script: "The script has been evolving and being rewritten as we go, and what you want to say is, 'Who launched a $100 million ship without a rudder, and who's getting fired for this?' But that's the way it goes. That's the way they make these movies... big deal. I think someone should be shot, but I'm not in charge".[64] Johnston said the actors went through an uncomfortable production shoot and that Macy may have simply made the critical comments on a bad day of filming.[54] As the film approached its release, Macy said: "It was about the most amazing thing I've ever done in this business".[9]

Johnston thought about quitting the project on a few occasions because of uncertainty about how the film would turn out, considering that it did not have a finished script.[44] He said that making the film was "a living hell on a daily basis",[5] and that shooting without a finished script was "nerve-wracking, but it was also a way of freeing up the whole creative process. We could literally decide on the day how we wanted a scene to progress. I'm not saying it's the way to make movies, but it gives you more freedom". Johnston said the actors were "very flexible" and that they dealt with the lack of a finished script "the best they could".[65] Alessandro Nivola criticized the film after its release, saying in a 2002 interview: "It was like the only part I've ever done that just had nothing for me to latch on to, character-wise. [...] It was kind of maddening".[66] The actors were frequently bruised during filming.[60][9] Leoni said "more of my makeup was to cover the real bruises than to create fake ones". Michael Lantieri, who worked on the previous films,[67] returned as the special effects consultant. Lantieri said that Jurassic Park III was the most physically demanding film of the series: "We had a cast that was willing to get real bruises and bumps, be around real heat, and actually go underwater".[60]

Locations

.jpeg.webp)

Filming began at Dillingham Airfield in Mokulēia, Hawaii,[57][58][59] and continued on Oahu during early September 2000.[58] Filming in Oahu included Heeia Kea Ranch.[60] Aerial footage of Molokai's North Shore cliffs was then filmed over a two-day period, followed by a week of filming in Kauai,[57][59][68] where locations included Hanalei Valley and rain forests in the Manoa Valley.[60] Filming in Hawaii concluded in mid-September 2000, after scenes were shot at the South Fork of Kauai's Wailua River.[68][69][70] By that time, John August had been hired to do the uncredited script revisions,[53] which were followed by additional work from Buchman.[47] Macy also wrote a scene.[44][55]

After the Hawaii shoot, production moved to California.[53] A dinosaur lecture given by the character of Alan Grant was filmed at Occidental College in Los Angeles on October 10, 2000.[71][72] Scenes were filmed at Center Bay Studios in Los Angeles at the end of October.[73] Other filming locations in California included a rock quarry in Irwindale,[74] while the interior of the InGen compound was filmed in a warehouse located east of downtown Los Angeles.[60] Another scene was filmed at El Mirage Lake, where Udesky and the mercenaries prepare for their visit to Isla Sorna.[75] Dern's small role as Ellie was filmed in a day.[22] Scenes set at Ellie's house were filmed in South Pasadena, California.[60]

Filming subsequently moved to Universal Studios' backlot in Los Angeles for 96 days.[60][72] Production designer Ed Verreaux and greensman Danny Ondrejko created a jungle rain forest at Universal's Stage 12. Ondrejko and his 14-member team took two months to create the jungle set, and Lantieri's team created mist and fog through the use of pipes. Johnston was impressed with the set and had difficulty distinguishing it from the jungles in Hawaii.[60]

The most challenging scene for Lantieri was the Spinosaurus attack on the plane, which was filmed on a soundstage.[60] Lantieri's team built four plane props for the scene.[4] The beginning of the scene depicts the crashed airplane in a tree, 15 feet (4.6 m) above ground, before the plane later falls to the ground and is rolled around by the Spinosaurus. For the early portion of the sequence, Lantieri created a pneumatic gimbal disguised as a tree, with the plane placed on top. The gimbal had 100 horsepower and was powered by hydraulics and hoses. It allowed the plane to be shaken and tilted. The plane also had a breakaway cockpit area for a shot in which the Spinosaurus tears the front end off. A later portion of the attack scene required close collaboration with Winston's team, which created a full-scale Spinosaurus leg prop, controlled by puppeteers. The leg, suspended in the air by two poles, was slammed down into one of the plane fuselage props for a series of shots. Another prop plane was rigged with a hydraulic machine, which crushed the fuselage from the inside, giving the impression that it was being crushed by the Spinosaurus. With another prop plane, the actors were filmed inside the fuselage as it is rolled around.[60] The actors agreed to do their own stunts for the scene,[4] which Macy compared to being inside a clothes dryer.[60] Stunt people were only used for one shot during this scene.[4]

The film is the first in the series not to be based on a novel, although it includes characters and ideas from Crichton, who wrote the novels that inspired the previous two films.[60] For Jurassic Park III, Crichton received a "based on characters created by" credit.[76] Scenes involving a pterosaur aviary and a T. rex's attempted attack on a river raft were featured in the first novel Jurassic Park (1990). Although these scenes were absent from the novel's film adaptation, they were added into Jurassic Park III. The film's Spinosaurus attack on the boat is a modified version of the scene from the novel.[67][77][78] At Falls Lake, located on the Universal lot, Verreaux and his team built a giant rock wall as part of a set that would depict InGen's Pteranodon aviary. Three months were spent laying foam blocks that were molded by hand to form jagged rock. A team subsequently built a 10-story, three-sided scaffold covered with netting to simulate the aviary. The aviary scene was filmed in early December 2000.[60][79] The set was then redecorated for the nighttime exterior sequence in which the Spinosaurus attacks the boat. The scene involved rain and fire, and took nine nights of filming.[60] Part of the scene required Macy to stand on a giant crane and distract the Spinosaurus. Macy fell off the crane, but had a harness. Another portion of the scene required the actors to perform under water.[9][41][80][81] The scene depicting the satellite phone in Spinosaurus feces was filmed using 250 US gallons (950 l; 210 imp gal) of oatmeal.[82]

In a November 2000 draft of the script, the U.S. State Department was to send in a helicopter and Ellie to rescue the characters, with Ellie explaining that she arrived thanks to a good friend at the department. This ending was not considered exciting enough, resulting in the final ending with the Marines and Navy coming to rescue the characters, while excluding Ellie from coming to the island. In the final film, Ellie's husband is an employee of the State Department, although his involvement in rescuing the group is not specified. The new ending was written in December, and the Pentagon lent two Sikorsky SH-60 Seahawks to the production, as well as four assault amphibious vehicles and 80 Marines.[83] Production returned to Hawaii in January 2001 to film the ending on Kauai's Pila'a Beach.[6][83][84] The film's longest rough cut without credits was around 96 minutes long.[22] The final film, including credits, is 92 minutes, making it the shortest installment in the series.[85]

Creatures on screen

As with the previous films, Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) provided dinosaurs through computer-generated imagery (CGI), while Stan Winston and his team provided animatronics.[60][86] The animatronics were more advanced than those used in previous films,[15][9] and included the ability to blink, for an increased sense of realism.[10] While animatronics were used for close-up shots, other scenes used sticks with pictures of dinosaur heads attached, as placeholders to which the actors could react.[15] Puppeteers worked together to create the T. rex, Spinosaurus, and Velociraptor movements.[60] Multiple puppeteers were assigned to operate different parts of each animatronic dinosaur, and in some cases, hours of practice were needed for a dinosaur's puppeteers to perform in synchrony.[54] The animatronics were powerful and considered dangerous, as one wrong move could kill someone.[86][87] One scene, depicting Udesky's death, was filmed with Winston team member John Rosengrant wearing a partial raptor suit.[4][88] Winston's team took roughly 13 months to design and create the various practical dinosaurs.[67] ILM scanned dinosaur sculptures, also created by Winston's team, to create the computer-generated versions of the animals.[4] ILM also designed some dinosaurs entirely through CGI, including Ankylosaurus and Brachiosaurus.[60] New dinosaurs not featured in earlier films included the Ankylosaurus, in addition to Ceratosaurus and Corythosaurus.[67]

Paleontologist Jack Horner worked as the film's technical advisor, as he had done for the previous films.[60] Horner was brought on early in the film's development when story ideas were being considered. After two films, the filmmakers wanted to replace the T. rex with a new dinosaur antagonist. Baryonyx was originally considered, and early concept posters reflected this.[4] Horner ultimately convinced the filmmakers to replace the T. rex with the larger Spinosaurus,[89] an animal which had a distinctive sail on its back. Johnston said that "a lot of dinosaurs have a very similar silhouette to the T. rex ... and we wanted the audience to instantly recognize this as something else".[90] Horner hypothesized that T. rex was more of a scavenger, while Spinosaurus was a true predator.[60] The roars of the Spinosaurus in the film were created by mixing the low guttural sounds of a lion and an alligator, a bear cub crying, and a lengthened cry of a large bird that gave the roars a raspy quality.[91]

Winston and his sculptors created an initial Spinosaurus design, and Horner then provided his scientific opinion. Winston's team began with a 1/16 maquette version of the Spinosaurus, before creating a 1/5-scale version with more detail, leading to the creation of the final, full-scale version. The process took 10 months.[60] The Spinosaurus animatronic was built from the knees up,[87] while full body shots of the animal were done through CGI.[54] The Spinosaurus animatronic measured 44 feet long,[10] weighed 13 tons, and was faster and more powerful than the 9-ton T. rex. Winston and his team had to remove a wall to get the Spinosaurus animatronic out of Winston's studio, located in Van Nuys, California. It was then transported by flatbed truck to the jungle set at Universal Studios' Stage 12. Verreaux had to design the set to accommodate the dinosaur. At the soundstage, the Spinosaurus was placed on a track that allowed the creature to be moved backward and forward.[60][87] Four Winston technicians were required to fully operate the Spinosaurus animatronic.[92]

The fight between the Spinosaurus and T. rex was one of the last scenes shot for the film, and the two animatronics were put to extensive use for the fight.[87] A T. rex animatronic from the previous film was re-skinned for its appearance in Jurassic Park III.[60][87] The Spinosaurus animatronic was so powerful that it ripped the head off of the T. rex during filming.[4][87] Johnston said the fight was meant as a modern homage to various earlier films that featured dinosaurs created by Ray Harryhausen.[67] An early script featured a death sequence for the Spinosaurus near the end of the film, as Alan Grant would use the resonating chamber to call a pack of raptors which would attack and kill it.[93]

Because of new discoveries and theories in the field of paleontology, several dinosaurs are portrayed differently in this film from in previous ones. Discoveries suggesting velociraptors were feathered prompted the addition of quill-like structures on the head and neck of the males in the film. Horner said: "We've found evidence that velociraptors had feathers, or feather-like structures, and we've incorporated that into the new look of the raptor".[60]

Spielberg insisted that Johnston include Pteranodons, which had been removed from the previous films for budget reasons, with the exception of a brief appearance in The Lost World: Jurassic Park.[13][94] The Pteranodons featured in Jurassic Park III are a fictionalized version of the actual animal. The animals were created with a combination of animatronics and puppetry.[60] Winston and his team created a Pteranodon model with a wingspan of 40 feet, although the creatures are predominantly featured in the film through CGI. ILM animators studied footage of bats and birds while in flight, and also closely worked with a Pteranodon expert to create the creatures' flight movements.[10] Winston's team also designed and created five rod puppets to depict baby pteranodons in a nest, with puppeteers working underneath the nest to control them.[60] Johnston chose the pteranodons to end the film because he wanted an ending shot of "these creatures being beautiful and elegant".[15] At one point, there were discussions about a final sequence in which the pteranodons would attack the survivors in their helicopter after departing from the island. This was scrapped for budgetary reasons.[95]

The film contains more than 400 effects shots, about twice the number featured in the two previous films combined. Most of the shots were for the fight between the T. rex and Spinosaurus, and for the Pteranodon aviary sequence.[10] Less than half of the 400 effects shots involved dinosaurs, as the animators also had to focus on environmental surroundings, such as jungle foliage brushed by dinosaurs. Some shots were only a few seconds long, but required months of work.[96]

Music

Composer John Williams, who worked on the previous films, was busy writing the music for A.I. Artificial Intelligence; he recommended Don Davis to write the Jurassic Park III score. Williams' original themes and several new ones—such as one for the Spinosaurus that focused on low sounds, with tubas, trombones, and timpani—were integrated into the score. The fight between the Spinosaurus and the Tyrannosaurus, which Davis compared to King Kong's fight with dinosaurs in the 1933 film, juxtaposes the Spinosaurus theme with the one Williams wrote for the T. rex.[97] In addition, "Big Hat, No Cattle", a song by Randy Newman, was used in a restaurant scene.[98] The soundtrack was released in July 2001.[99]

Marketing and merchandise

A teaser trailer was released online in September 2000,[100] and the first image from the film was released four months later.[101] Universal avoided excessive early marketing to prevent a possible backlash; the studio believed awareness of the film was already sufficient.[102] Marketing began in April 2001, three months before the film's release.[103] The first footage from the film was aired during the second-season finale of Survivor in May 2001,[104] and the official website went online at the end of June.[105] Promotional partners included Kodak and the Coca-Cola Company.[106][107] No fast-food promotions took place in the United States,[102] although children's meal toys based on the film were offered in Canadian Burger King outlets.[108]

A novelization by Scott Ciencin, aimed at young children, was published, as well.[109] Ciencin also wrote three children's books to tie in with the film's events:[110][111] Jurassic Park Adventures: Survivor, the first book, details the eight weeks Eric spent alone on Isla Sorna;[112] Jurassic Park Adventures: Prey has Eric and Alan returning to Isla Sorna to rescue a group of teenage filmmakers;[113] and Jurassic Park Adventures: Flyers involves Eric and Alan leading the Pteranodon home after they nest in a Universal Studios theme park.[114]

In early 2001, Hasbro released a line of 3.5-inch (89 mm) action figures including electronic dinosaurs, humans, and vehicles, to coincide with the film's release.[115][116] The figures were scaled down from the original Kenner action figures from the pre-Jurassic Park III toy lines.[115] A line of toys were also released through the Lego Studios brand.[117][118] Playskool released a line of toys called Jurassic Park Junior, which were aimed at young children.[119][120] A smaller line of die-cast toys and a range of clothes were also produced. In November 2001, to promote the film's impending home media release, Universal launched a viral marketing website for Isla Travel, a fictional Isla Sorna travel agency.[121]

Cell phone promotion

For the film's home media release, Universal partnered with cell-phone company Hop-On to produce "the world's first disposable cell phone", which would have been available through an in-package offer upon purchase of the film.[122][123] The telephones were to be delivered free to customers who responded to a winning promotional card that was supplied with selected copies of the film.[122] Around 5,000 copies of the film contained a winning promotional card; around 1,000 of them were redeemed.[124]

The promotion was cancelled because the handsets could not be finished on time.[124][125] An investigation by the San Francisco Chronicle revealed that sample versions of Hop-On's cell phones were actually modified Nokia handsets; Hop-On was having problems with its own design.[125] Customers who were to receive the cell phones received a $30 check and a free DVD, instead.[124]

Release

Jurassic Park III premiered at the Universal Amphitheater in Los Angeles, California, on July 16, 2001;[126] two days later the film was released in the United States and other countries.[127] Neill, a resident of New Zealand, hosted the film's Australasian premiere in the city of Dunedin in August.[128]

The film was released on VHS and DVD on December 11, 2001.[129][130] It was re-released with both sequels in December as the Jurassic Park Trilogy,[131] and as the Jurassic Park Adventure Pack in November 2005.[132] In 2011, the film was released on Blu-ray as part of the Jurassic Park: Ultimate Trilogy Blu-ray collection.[133] Jurassic Park III is also included in the Jurassic Park 4K UHD Blu-ray collection, which was released on May 22, 2018.[134]

Reception

Box office

Jurassic Park III opened on July 18, 2001 with $19 million. At the time, it had the second-highest Wednesday opening of any film, after Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace.[135] In just five days, it generated a total of $80.9 million. The film had also grossed $50.3 million during its three-day opening weekend.[136] When the film opened, it had the fourth-highest July opening weekend, behind Independence Day, Men in Black and X-Men.[137] The film ultimately earned $181.2 million in the United States and $368.8 million worldwide, making it the eighth-highest-grossing film of the year worldwide. Despite this, it is the lowest-grossing film in the franchise.[2]

Critical response

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 48% based on 186 reviews, with an average rating of 5.30/10. The site's critics consensus reads: "Jurassic Park III is darker and faster than its predecessors, but that doesn't quite compensate for the franchise's continuing creative decline."[138] On Metacritic the film has a weighted average score of 42 out of 100, based on 30 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[139] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B−" on an A+ to F scale.[140] On Metacritic, it was the lowest-rated film of the Jurassic Park franchise until the release of Jurassic World Dominion in 2022 and remains the lowest rated film in the original Jurassic Park trilogy. The films' distributor Universal did not allow reviews to be published until the film's release.[141]

Entertainment Weekly's Owen Gleiberman, who praised the previous Jurassic Park films, awarded the third film a C grade, writing "Jurassic Park III has no pretensions to be anything more than a goose-bumpy fantasy theme-park ride for kids, but it's such a routine ride. Spielberg's wizardry is gone, and his balletic light touch as well, and that gives too much of this 90-minute movie over to the duller-than-dull characters".[142] Derek Elley of Variety called the film "an all-action, helter-skelter, don't-forget-to-buy-the-computer-game ride that makes the two previous installments look like models of classic filmmaking".[143] Ben Varkontine of PopMatters called it "not as good a ride as the first, but a damn sight better than the second".[144] Much of the criticism was leveled at the plot as being simply a chase movie with no character development; Apollo Movie Guide panned the film as being "almost the same as the first movie" with "no need for new ideas or even a script".[145] Empire magazine gave the film 3 stars out of 5, calling it "short, scrappy and intermittently scary".[146]

On Ebert and Roeper, Richard Roeper gave it a Thumbs Down while Roger Ebert awarded a Thumbs Up.[147] In a subsequent review, Ebert called it "the best blockbuster of the Summer".[148] In his review, Ebert gave the film three stars and said it "is not as awe-inspiring as the first film or as elaborate as the second, but in its own B-movie way it's a nice little thrill machine". He also wrote: "I can't praise it for its art, but I must not neglect its craft, and on that basis I recommend it".[149] Paleontologist Robert T. Bakker, an early pioneer of the dinosaur-bird connection, said the feather quills added to the Velociraptor for Jurassic Park III "looked like a roadrunner's toupee", but conceded that feathers are difficult subjects for computer animation and speculated that Jurassic Park IV's raptors would have more realistic plumage.[150] Spielberg, according to his spokesman, was "very happy" with Johnston's work on the film.[151] In 2002, Crichton said he had not watched the film.[152] Some fans of the series were upset with the decision to kill off the T. rex and replace it with a new dinosaur.[153]

Retrospective assessments

Some later reviews of the film have been positive,[94][154][155] with a couple of critics declaring it superior to The Lost World: Jurassic Park.[156][157] Retrospective reviews have also praised the aviary sequence.[94][154][156][157][158] Simon Brew, writing for Den of Geek, stated in 2007 that the film has "an efficiency and focus" that was missing in the previous film. He enjoyed the set pieces, but criticized the abrupt ending.[154] Comparing the first film with Jurassic Park III, David Chen of /Film wrote in 2009 that the original managed to "thrill audiences and make them think", while the latter "did neither particularly well".[159]

Several critics reviewed the film in 2015, when Jurassic World was released. Justin Harp of Digital Spy wrote that despite the shortcomings of Jurassic Park III, it "remains immensely watchable and visually impressive. It manages to strike a clear balance between moments of terror and genuine laughs". Although Harp considered the film to be the black sheep of the series, he described it as "fresh, exciting and, most of all, a whole lot of fun".[157] Matt Goldberg of Collider wrote that the film "doesn't really have any reason to exist beyond proving that the franchise maybe never should have been a franchise to begin with". Goldberg stated that the film "is overly excited to let you know [the raptors] can vocally speak to each other, which ends up just looking funny. It feels like we're missing subtitles".[160] Zaki Hasan of Sequart Organization enjoyed the film, but wrote that it has issues such as the abrupt ending.[161]

Entertainment Weekly, in 2018, wrote "what the plot lacks in credibility it makes up for with relatability". The magazine praised it as the only film in the series that "has zero to do with scientific stupidity or sinister corporate forces", writing that it was "perhaps the most narratively original" film out of all them.[94] Neill said in 2021 that he believes the film is "dismissed too easily", opining that it is "pretty damn good" aside from the final 10 minutes and "hurried" ending.[162][163]

Accolades

| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipient(s) | Result | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI Film Awards | May 15, 2002 | Best Music | Don Davis and John Williams | Won | [164] |

| Golden Raspberry Awards | March 23, 2002 | Worst Remake or Sequel | Nominated | [165] | |

| Golden Reel Awards | March 23, 2002 | Best Sound Editing – Effects & Foley | Nominated | [166] | |

| Golden Trailer Awards | 2002 | Best Horror/Thriller Film | Nominated | [167] | |

| Satellite Awards | January 19, 2002 | Best Visual Effects | Jim Mitchell | Nominated | [168] |

| Best Sound | Howell Gibbens | Nominated | |||

| Saturn Awards | June 10, 2002 | Best Science Fiction Film | Nominated | [169] | |

| Best Special Effects | Nominated | ||||

| Stinkers Bad Movie Awards | 2002 | Worst Actress | Tea Leoni | Nominated | [170] |

| Worst Screenplay for a Film Grossing More Than $100 Million Worldwide Using Hollywood Math | Nominated | ||||

| Worst Sequel | Nominated | ||||

Video games

Several film-based video games were released in 2001. Knowledge Adventure produced three games, Jurassic Park III: Danger Zone!, Jurassic Park III: Dino Defender, and Scan Command: Jurassic Park, all for Microsoft Windows. Three other games were released by Konami for the Game Boy Advance, including Jurassic Park III: The DNA Factor, Jurassic Park III: Island Attack, and Jurassic Park III: Park Builder. An arcade game, also titled Jurassic Park III, was also released.[171]

Notes

- The island became restricted to visitors following the events of The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997).

- As depicted in Jurassic Park (1993).

References

- "Jurassic Park III". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on February 16, 2013. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- "Jurassic Park III (2001)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on May 9, 2021. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- "Jurassic Park III (2001) - Joe Johnston". AllMovie. Archived from the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- The Making of Jurassic Park III (DVD). Universal Pictures. 2005.

- "Back to Jurassic Park with Joe Johnston". IGN. July 17, 2001. Archived from the original on February 22, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- "Jumanji's Joe Johnston Joins Jurassic". About.com. Archived from the original on March 5, 2006. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Ressner, Jeffrey (May 19, 1997). "Cinema: I Wanted to See a T. rex Stomping Down a Street". TIME. Archived from the original on October 3, 2018. Retrieved November 12, 2015.(subscription required)

- Archerd, Army (May 28, 1997). "Spielberg adds joke to Japanese 'World'". Variety. Archived from the original on February 20, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- "Macy Gets Fired Up Over Jurassic Park Dinosaurs". Zap2It. July 6, 2001. Archived from the original on February 21, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- Hockensmith, Steve (July 15, 2001). "Dino vs. dino: Grudge match". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on February 25, 2020. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- Spelling, Ian (July 2001). "Dream Worker". Starlog. p. 30. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- Cox, Dan (June 30, 1998). "'Jurassic 3' slated by U; Spielberg, Crichton to pen pic". Variety. Archived from the original on December 25, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- "Johnston on Underwater Dinos, Spielberg's JP3 Idea". DansJP3Page.com. Movieline. June 10, 2001. Archived from the original on June 28, 2001.

- "'Jurassic Park 3' eyeing Kauai". The Honolulu Advertiser. August 19, 1999. Archived from the original on February 27, 2020. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- Bonin, Liane (July 18, 2001). "Dino Might". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on July 21, 2001.

- Petrikin, Chris (August 5, 1999). "'Jurassic' redux". Variety. Archived from the original on December 25, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- Fleming, Michael (April 26, 2001). "Newmarket winds up in the 'Poe' house". Variety. Archived from the original on December 5, 2020. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- Mathai, Jeremy (July 20, 2021). "'Jurassic Park 3' Could've Featured A Scene Where A Raptor Rode A Motorcycle Off A Cliff". /Film. Archived from the original on November 16, 2021. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- Howard, Jessica (July 20, 2021). "Apparently 'Jurassic Park 3' Almost Featured A Velociraptor Riding A Motorcycle To Its Death". Uproxx. Archived from the original on November 16, 2021. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- "Jurassic Park 3". Empire. January 17, 2000. Archived from the original on July 2, 2001.

- "Spielberg dodges directing 'Jurassic 3'". CNN. August 6, 1999. Archived from the original on December 6, 2006. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- "Evolution of the dinos - Ten questions with Joe Johnston". DVDFile.com. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original on January 3, 2002.

- Mottram, James (2021). Jurassic Park: The Ultimate Visual History. Insight Editions. ISBN 978-1-68383-545-5. Archived from the original on May 2, 2022. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- "'Jurassic Park' 3 cast call". Reno Gazette-Journal. June 10, 2000. Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved February 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Head, Steve (June 11, 2000). "Who Gets to Run From the Dinosaurs in Jurassic Park 3?". IGN. Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- "Jurassic Park III early script page (1 of 3)". DansJP3Page.com. 2000. Archived from the original on June 12, 2001.

- "Jurassic Park III early script page (2 of 3)". DansJP3Page.com. 2000. Archived from the original on June 13, 2001.

- "Jurassic Park III early script page (3 of 3)". DansJP3Page.com. 2000. Archived from the original on June 13, 2001.

- Adler, Shawn (January 31, 2008). "A Return To 'Jurassic Park' Wouldn't Be Dino-Mite Says Star". MTV. Archived from the original on February 21, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- Jurassic Park III (DVD). 2001. During the pre-production phase, concept artists created posters for the film using these working titles. The posters can be found via the special features of certain DVD releases of the film.

- "JURASSIC PARK 3.... some news and some musings..." Aint-It-Cool-News.com. February 1, 2000. Archived from the original on March 3, 2000.

- "Further Information On JURASSIC PARK 3". Aint-It-Cool-News.com. February 2, 2000. Archived from the original on March 4, 2000.

- "Scene Is Set For 'Jurassic Park' Sequel". Sun-Sentinel. October 25, 1996. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- Head, Steve (March 29, 2000). "Location News & Trailer Rumor". IGN.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- McNary, Dave (June 28, 2000). "Neill to reprise 'Jurassic' role; Third installment to begin shooting July/Aug". Variety. Archived from the original on December 25, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- Baskin, Ellen (July 16, 2001). "Bone Vivant". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 25, 2020. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- Mottram, James (June 26, 2001). "Sam Neill interview". BBC. Archived from the original on September 14, 2020. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- Ryan, Tim (June 21, 2000). "Hawaii will star in 'Jurassic Park' prequel". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Archived from the original on November 18, 2000.

- Brake, Scott (July 20, 2000). "Rewrites and New Casting For Jurassic Park 3". IGN.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- DiOrio, Carl; Brodesser, Claude (July 20, 2000). "Inside Move: 'Jurassic' elects scribes". Variety. Archived from the original on February 22, 2020. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

- Polowy, Kevin (April 13, 2018). "Role Recall: William H. Macy on talking 'Fargie', shooting 'Boogie Nights' suicide, and crying for 12 hours during 'Pleasantville'". Yahoo. Archived from the original on February 27, 2020. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- Head, Steve (August 9, 2000). "Jurassic Park 3, The Casting Continues". IGN.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- Masters, Kim (January 30, 2013). "Lucasfilm's Kathleen Kennedy on 'Star Wars', 'Lincoln' and Secret J.J. Abrams Meetings (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 9, 2015.

- "Jurassic III Had Shaky Start". Sci Fi Wire. July 11, 2001. Archived from the original on August 15, 2001. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- Head, Steve (August 16, 2000). "Jurassic Park 3 and the Dinosaur Quarry". IGN.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- Head, Steve (August 7, 2000). "Jurassic Park 3 Seeks Military Base". IGN.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- "Jurassic Park III Script Pages Online". Ain't It Cool News. May 17, 2001. Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- Head, Steve (July 31, 2000). "Spielberg Signs Lucrative Deal For Jurassic Park 3". IGN. Archived from the original on February 22, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- "Exposure: Uneasy Rider". Spin. June 23, 2003. Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- Hennigan, Adrian (January 14, 2005). "Alexander Payne interview". BBC. Archived from the original on January 30, 2020. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- Mertes, Micah (June 20, 2018). "Alexander Payne wrote a 'Jurassic Park' sequel". Omaha World-Herald. Archived from the original on February 25, 2020. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- Pearlman, Cindy (July 17, 2001). "New dinosaur is bigger and badder". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on July 19, 2001.

- Head, Steve (September 21, 2000). "Flying Dinos for Jurassic Park 3?". IGN.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- Spelling, Ian (July 2001). "Jurassic Sky". Starlog. pp. 58–61. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- "Jurassic Park III". Entertainment Weekly. May 18, 2001. Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- Longsdorf, Amy (July 14, 2001). "Spotlight on Tea Leoni ** "Jurassic' star has a sense of humor about the Land of Make Believe". The Morning Call. Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- Ryan, Tim (August 25, 2000). "Cameras roll soon for Jurassic Park III". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Archived from the original on October 18, 2000.

- Kieszkowski, Elizabeth (September 2, 2000). "Media gain access to 'Jurassic Park III' set". The Honolulu Advertiser. Archived from the original on October 18, 2000.

- K. Kakesako, Gregg (September 4, 2000). "Film producers catch aloha spirit". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Archived from the original on June 25, 2001.

- "Jurassic Park 3: Production Notes". Cinema.com. Archived from the original on May 28, 2016. Retrieved June 3, 2016.

- Tobias, Scott (May 30, 2001). "William H. Macy interview". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on June 5, 2001.

- Head, Steve (March 9, 2001). "Joe Cool Johnston Responds to Macy's Comments". IGN. Archived from the original on February 21, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- King, Dennis (July 20, 2001). "Jurassic Park III". Tulsa World. Archived from the original on February 21, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- "Jurassic III: Hell on Earth for Star". TV Guide. December 18, 2000. Archived from the original on February 21, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- Turner, Megan (July 9, 2001). "After Throwing Away the Script, Filmmakers Were in the . . . Jurassic Dark". New York Post. Archived from the original on February 21, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- Head, Steve (October 16, 2002). "Jurassic Park IV? "I Hope Not", Says Nivola". IGN. Archived from the original on February 21, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- Berry, Mark F. (2015). "Jurassic Park III". The Dinosaur Filmography. McFarland. pp. 171–178. ISBN 978-1-4766-0674-3. Archived from the original on February 18, 2022. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- "Another 'Jurassic' filming on Kaua'i". The Garden Island. September 15, 2000. Archived from the original on March 6, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- "Creature features still big on Kaua'i". The Garden Island. September 16, 2000. Archived from the original on March 6, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Cook, Chris (September 22, 2000). "Keeping Kaua'i on the silver screen". The Garden Island. Archived from the original on March 6, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Head, Steve (October 13, 2000). "Jurassic Park 3 Goes to School". IGN. Archived from the original on February 22, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- Head, Steve (October 24, 2000). "Jurassic Park 3 on the Studio Backlot". IGN.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- Head, Steve (October 31, 2000). "Jurassic Park 3 at Center Bay Studios". IGN.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- "Jurassic Park III production notes: Dinos Everywhere". CinemaReview.com. Archived from the original on January 6, 2016. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- Johnson, Shelly (March 20, 2017). "'Silhouette Sunday' Reprise from ASC Instagram". Archived from the original on February 25, 2020. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- Elley, Derek (July 17, 2001). "Jurassic Park III". Variety. Archived from the original on September 13, 2007. Retrieved July 9, 2007.

- Vlastelica, Ryan (June 4, 2015). "In Jurassic Park, Spielberg made a family favorite from an adult book". A.V. Club. Archived from the original on February 4, 2017. Retrieved July 26, 2017.

- "Jurassic Park III Review". Aint It Cool News. July 19, 2001. Archived from the original on February 27, 2020. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- Johnson, Shelly (April 11, 2017). "Jurassic Park 3 – Pteranodon Canyon". Archived from the original on February 22, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- Mottram, James (June 26, 2001). "William H Macy interview". BBC. Archived from the original on September 12, 2019. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- Belloni, Matthew; Wilson Hunt, Stacey (June 8, 2011). "The Drama Actor Roundtable". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 27, 2020. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- Keck, William (July 26, 2001). "The poop on JPIII's dino droppings". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on February 21, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- Robb, David L. (2011). "The Producers Will 'Punch It Up' In Any Manner We Dictate". Operation Hollywood: How the Pentagon Shapes and Censors the Movies. Prometheus Books. pp. 73–75. ISBN 978-1-61592-451-6. Archived from the original on May 2, 2022. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- "Finale Photos". DansJP3Page.com. February 6, 2001. Archived from the original on February 23, 2001.

- Ankers, Adele (April 6, 2022). "Jurassic World: Dominion Runtime Reportedly Revealed, And It's the Longest in the Franchise". IGN. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- "Building a Better Dinosaur with Stan Winston". IGN. July 18, 2001. Archived from the original on February 22, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- "Jurassic Park III's T-rex killer: Spinosaurus". Stan Winston School of Character Arts. September 29, 2012. Archived from the original on February 27, 2020. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- Sciretta, Peter (December 24, 2014). "'Jurassic Park': The Evolution of a Raptor Suit". /Film. Archived from the original on February 22, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- Brown, Simon Leo (March 20, 2016). "Jurassic World dinosaur expert Jack Horner details where movies got the science wrong". ABC Online. Archived from the original on October 27, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- "Production Notes". Cinema Review. Archived from the original on May 15, 2008. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- "How Jurassic Park III Created The Roar Of The Spinosaurus". /Film. August 19, 2022.

- Goodale, Gloria (July 20, 2001). "An all-too-real dinosaur 'puppet'". Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on February 25, 2020. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- Kennedy, Michael (July 21, 2021). "How The Spinosaurus Was Supposed To Die In Jurassic Park 3". ScreenRant. Archived from the original on November 16, 2021. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- "The Ultimate Guide to Jurassic Park". Entertainment Weekly. Time Home Entertainment. June 15, 2018. pp. 78–80. ISBN 9781547843688. Archived from the original on August 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Libbey, Dirk (September 3, 2020). "One Awesome-Sounding Jurassic Park 3 Scene Got Cut Thanks To Being Too Expensive". CinemaBlend. Archived from the original on June 25, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- Holtzclaw, Mike (July 15, 2001). "All About the Dinos". Daily Press. Archived from the original on February 25, 2020. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- The Sounds of Jurassic Park III. Jurassic Park III Blu-Ray: Universal Home Video.

- Plume, Kenneth (July 25, 2001). "Composer Don Davis Talks Jurassic Park III and the Matrix Sequels". IGN. Archived from the original on May 2, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- "Jurassic Park III soundtrack valued at $12.99". Soundtrack.net. Archived from the original on May 26, 2013. Retrieved May 17, 2007.

- Head, Steve (September 11, 2000). "Jurassic Park 3 Teaser Trailer Online". IGN.com. Archived from the original on November 6, 2014. Retrieved November 6, 2014.

- Head, Steve (January 10, 2001). "First Photo from Jurassic Park 3". IGN. Archived from the original on February 21, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- Rose, Marla Matzer (May 25, 2001). "Studios taking cautious tack in marketing". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on June 12, 2001.

- "Behind the Scenes of Jurassic Park 3". Digital Media FX. April 8, 2001. Archived from the original on April 20, 2001.

- "First Jurassic Park III TV Spot Right Here, Baby!!!". AintItCool.com. May 3, 2001. Archived from the original on November 16, 2015. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- Head, Steve (June 30, 2001). "Jurassic Park III Official Site Goes Live". IGN. Archived from the original on February 22, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- "Kodak - Jurassic Park 3 Partner". CountingDown.com. April 2, 2001. Archived from the original on April 11, 2001.

- "Coke announces in-theater tie-in". CountingDown.com. March 26, 2001. Archived from the original on April 11, 2001.

- "Burger King confirmed for fast food promotion!". CountingDown.com. May 20, 2001. Archived from the original on June 28, 2001.

- Ciencin, Scott (2001). Jurassic Park III. Random House Books for Young Readers. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-375-81318-4.

- "Scott Ciencin". News-Press. March 6, 2001. Archived from the original on August 5, 2021. Retrieved February 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Ciencin's dinosaur books keep kids roaring for more". News-Press. March 9, 2001. Archived from the original on November 23, 2021. Retrieved February 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Ciencin, Scott (June 2001). Survivor. Boxtree. p. 116. ISBN 0-7522-1978-2.

- Scott Ciencin (October 2001). Prey. Boxtree. p. 123. ISBN 0-375-81290-3.

- Ciencin, Scott (March 2002). Flyers. Boxtree. p. 128. ISBN 0-375-81291-1.

- "Jurassic Park 3". JPToys.com. Archived from the original on November 6, 2015. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- Lipkowitz, Daniel (2001). "Hasbro: Jurassic Park III". Altered States Magazine. Archived from the original on February 22, 2001.

- Lipkowitz, Daniel (2001). "LEGO: Jurassic Park III, Mindstorms". Altered States Magazine. Archived from the original on February 22, 2001.

- "The LEGO Company and Universal Studios Consumer Products Group Announce New Toys Based on Jurassic Park III". The Free Library. February 5, 2001. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- Keier, Helen (February 15, 2001). "Toy Fair Day 3 – Part 2: Jurassic Park 3, Lord of the Rings, Star Wars & More!". IGN. Archived from the original on February 18, 2001.

- "Dinosaurs even the smallest kids will love". ToyNerd.com. June 18, 2013. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- "DVD Promo Site islaTravel.com Opens". DansJP3Page.com. November 27, 2001. Archived from the original on February 3, 2002.

- Hettrick, Scott (November 28, 2001). "Dinos phone in video promotion". Variety. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- "Universal Studios Home Video and Hop-On Introduce the World's First Disposable, Fully Recyclable Cell Phone: The Jurassic Park Survival Cell Phone". Hop-On.com. November 29, 2001. Archived from the original on June 3, 2002.

- Wagner, Holly J. (June 7, 2002). "Jurassic Park III Survival Phone Promo Is Extinct". Home Media Magazine. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- Wallack, Todd (March 29, 2002). "Sample 'new' cell phone really just modified Nokia". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- Head, Steve (July 10, 2001). "Jurassic Park III's West Coast Premiere". IGN. Archived from the original on November 27, 2015. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- "Universal Pictures to Release 'Jurassic Park III' Wednesday, July 18 In Digital Cinema Format in 10 Theaters, Including Two Screens at Loews Universal Studios Cinemas". Business Wire (Press release). Berkshire Hathaway. July 10, 2001. Archived from the original on August 11, 2001. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- "Dinosaur tale sounds GE warning". TVNZ. August 24, 2001. Archived from the original on February 25, 2020. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- "Jurassic Park III". IGN. December 12, 2001. Archived from the original on October 11, 2002.

- Wolf, Jessica (September 21, 2001). "Jurassic Park III' Becomes Sellthrough Quarry Dec. 11". hive4media.com. Archived from the original on November 1, 2001. Retrieved September 2, 2019.

- "Jurassic Park Trilogy". IGN. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009.

- "Jurassic Park Adventure Pack". IGN. November 17, 2005. Archived from the original on February 5, 2008.

- Shaffer, R.L. (October 25, 2011). "Jurassic Park: Ultimate Trilogy Blu-ray Review". IGN. Archived from the original on May 23, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- "High Def Digest | Blu-ray and Games News and Reviews in High Definition". ultrahd.highdefdigest.com. Archived from the original on May 23, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- "Same weekend. New record. 'Men in Black 2' Bags $87 Million Over Fourth of July Weekend". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- Pearlman, Cindy (July 23, 2001). "'Jurassic 3' delivers crushing blow". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on July 25, 2001.

- "Box Office: Jurassic Park III Roars to No. 1". ABC News. Archived from the original on March 26, 2022. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- "Jurassic Park III". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on June 12, 2015. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

- "Jurassic Park III: Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on April 19, 2007. Retrieved May 15, 2007.

- "Find CinemaScore" (Type "Jurassic Park" in the search box). CinemaScore. Archived from the original on January 2, 2018. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- "Jurassic Hype". OC Weekly. July 19, 2001. Archived from the original on December 2, 2019.

- "News Review: Jurassic Park III". Entertainment Weekly. August 9, 2006. Archived from the original on December 5, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- Elley, Derek (July 17, 2001). "Jurassic Park III". Variety. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Varkontine, Ben. "Jurassic Park III". PopMatters. Archived from the original on September 3, 2007. Retrieved July 8, 2007.

- Webster, Brian. "Jurassic Park III". Apollo Movie Guide. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved July 8, 2007.

- "Review of Jurassic Park 3". EmpireOnline. Archived from the original on October 17, 2012.

- "Ebert and Roeper Jurassic Park III". Buena Vista Entertainment. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- "Ebert and Roeper Planet of the Apes". Buena Vista Entertainment. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- Ebert, Roger (July 18, 2001). "Jurassic Park 3 review". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on September 12, 2001. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- Bakker, R. 2004. "Dinosaurs Acting Like Birds, and Vice Versa – An Homage to the Reverend Edward Hitchcock, First Director of the Massachusetts Geological Survey" in Feathered Dragons. Currie, P.; Koppelhus, E.; Shugar, M.; Wright J. eds. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 1-11.

- "Jurassic Park Four Unearthed". Empire. May 22, 2001. Archived from the original on July 2, 2001.

- "Frequently Asked Questions". Crichton-Official.com. Archived from the original on June 2, 2002.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Romano, Nick (June 17, 2015). "Jurassic World Snuck In A Sweet Nod To Jurassic Park 3". CinemaBlend. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Brew, Simon (November 20, 2007). "Underappreciated movies: Jurassic Park III". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Nemiroff, Perri (April 8, 2021). "'Jurassic Park III' Is a Good Movie, Actually; Collider Movie Club Explains Why". Collider. Archived from the original on June 25, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- Nashawaty, Chris (March 22, 2013). "Jurassic Park III". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Harp, Justin (June 10, 2015). "In Defence Of... Jurassic Park III: Fresh, exciting and a whole lot of fun". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Stefansky, Emma (August 7, 2020). "I Don't Understand Why Everyone Hates 'Jurassic Park III'". Thrillist. Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- Chen, David (September 7, 2009). "Jurassic Park vs. Jurassic Park 3: Lament for a Fallen Franchise". /Film. Archived from the original on June 25, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- Goldberg, Matt (June 10, 2015). "Jurassic Park III Revisited: "This Is How You Make Dinosaurs?"". Collider. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Hasan, Zaki (June 11, 2015). "Jurassic Park III: A Retro Review". Sequart Organization. Archived from the original on February 18, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Meares, Joel (February 4, 2021). "Sam Neill Says Jurassic World: Dominion Co-Star Chris Pratt Showed Him a Thing Or Two About Being An Action Star". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- Chase, Stephanie (February 3, 2021). "Jurassic World star Sam Neill defends Jurassic Park III". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on February 3, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- "Top Film, TV, Cable Composers Honored at BMI's Annual Film/TV Awards". Broadcast Music Incorporated. Archived from the original on October 18, 2017. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- Armstrong, Mark (February 11, 2002). "Razzies Get 'Fingered'". E! Online. Archived from the original on August 9, 2018. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- Hobbs, John (February 10, 2002). "Sound editors tap noms for Golden Reel Awards". Variety. Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- "WINNERS AND NOMINEES". Golden Trailer Awards. Archived from the original on March 7, 2012. Retrieved June 23, 2011.

- Berkshire, Geoff (December 17, 2001). "'Moulin Rouge' in orbit, topping Satellite noms". Variety. Archived from the original on July 6, 2018. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- "Nominees for 28th Annual Saturn Awards". United Press International. March 14, 2002. Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- "2001 24th Hastings Bad Cinema Society Stinkers Awards". Stinkers Bad Movie Awards. Archived from the original on August 15, 2007. Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- "Jurassic Park Licensees". Moby Games. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2007.

External links

- Official website (

Page will play audio when loaded)

Page will play audio when loaded)

- Jurassic Park III at Amblin

- Jurassic Park III at IMDb

- Jurassic Park III at AllMovie

- Jurassic Park III at Rotten Tomatoes

- Jurassic Park III at Box Office Mojo