George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 1738[lower-alpha 3] – 29 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until his death in 1820. He was the longest-lived and longest-reigning king in British history. He was concurrently Duke and Prince-elector of Brunswick-Lüneburg ("Hanover") in the Holy Roman Empire before becoming King of Hanover on 12 October 1814. He was a monarch of the House of Hanover but, unlike his two predecessors, he was born in Great Britain, spoke English as his first language[1] and never visited Hanover.[2]

| George III | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Coronation portrait by Allan Ramsay, 1762 | |||||

| King of Great Britain and Ireland,[lower-alpha 1] Elector/King of Hanover[lower-alpha 2] (more...) | |||||

| Reign | 25 October 1760 – 29 January 1820 | ||||

| Coronation | 22 September 1761 | ||||

| Predecessor | George II | ||||

| Successor | George IV | ||||

| Prince Regent | George (1811–1820) | ||||

| Born | Prince George 4 June 1738 [NS][lower-alpha 3] Norfolk House, St James's Square, London, England | ||||

| Died | 29 January 1820 (aged 81) Windsor Castle, Berkshire, England | ||||

| Burial | 16 February 1820 Royal Vault, St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| House | Hanover | ||||

| Father | Frederick, Prince of Wales | ||||

| Mother | Princess Augusta of Saxe-Gotha | ||||

| Religion | Anglicanism | ||||

| Signature |  | ||||

George's life and reign were marked by a series of military conflicts involving his kingdoms, much of the rest of Europe, and places farther afield in Africa, the Americas and Asia. Early in his reign, Great Britain defeated France in the Seven Years' War, becoming the dominant European power in North America and India. However, many of Britain's American colonies were soon lost in the American War of Independence. Further wars against revolutionary and Napoleonic France from 1793 concluded in the defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. In 1807, the transatlantic slave trade was banned from the British Empire.

In the later part of his life, George had recurrent, and eventually permanent, mental illness. Although it has since been suggested that he had bipolar disorder or the blood disease porphyria, the cause of his illness remains unknown. George suffered a final relapse in 1810, and his eldest son, the Prince of Wales, became Prince Regent the following year. When George III died in 1820, the Regent succeeded him as King George IV. Historical analysis of George III's life has gone through a "kaleidoscope of changing views" that have depended heavily on the prejudices of his biographers and the sources available to them.[3]

Early life

_and_Edward_Augustus%252C_Duke_of_York_and_Albany_by_Richard_Wilson.jpg.webp)

George was born on 4 June 1738 in London at Norfolk House in St James's Square. He was a grandson of King George II, and the eldest son of Frederick, Prince of Wales, and Augusta of Saxe-Gotha. As he was born two months prematurely and thought unlikely to survive, he was baptised the same day by Thomas Secker, who was both Rector of St James's, Piccadilly, and Bishop of Oxford.[4][5] One month later he was publicly baptised at Norfolk House, again by Secker. His godparents were King Frederick I of Sweden (for whom Lord Baltimore stood proxy), his uncle Frederick III, Duke of Saxe-Gotha (for whom Lord Carnarvon stood proxy), and his great-aunt Sophia Dorothea, Queen in Prussia (for whom Lady Charlotte Edwin stood proxy).[6]

George grew into a healthy, reserved and shy child. The family moved to Leicester Square, where George and his younger brother Prince Edward, Duke of York and Albany, were educated together by private tutors. Family letters show that he could read and write in both English and German, as well as comment on political events of the time, by the age of eight.[7] He was the first British monarch to study science systematically.[8]

Apart from chemistry and physics, his lessons included astronomy, mathematics, French, Latin, history, music, geography, commerce, agriculture and constitutional law, along with sporting and social accomplishments such as dancing, fencing and riding. His religious education was wholly Anglican.[8] At the age of 10, George took part in a family production of Joseph Addison's play Cato and said in the new prologue: "What, tho' a boy! It may with truth be said, A boy in England born, in England bred."[9] Historian Romney Sedgwick argued that these lines appear "to be the source of the only historical phrase with which he is associated".[10]

King George II disliked the Prince of Wales and took little interest in his grandchildren. However, in 1751, the Prince died unexpectedly from a lung injury at the age of 44, and his son George became heir apparent to the throne and inherited his father's title of Duke of Edinburgh. Now more interested in his grandson, three weeks later the King created George Prince of Wales.[11][12]

%252C_by_Jean-%C3%89tienne_Liotard.jpg.webp)

In the spring of 1756, as George approached his eighteenth birthday, the King offered him a grand establishment at St James's Palace, but George refused the offer, guided by his mother and her confidant, Lord Bute, who later served as prime minister.[13] George's mother, now the Dowager Princess of Wales, preferred to keep George at home where she could imbue him with her strict moral values.[14][15]

Marriage

In 1759, George was smitten with Lady Sarah Lennox, sister of Charles Lennox, 3rd Duke of Richmond, but Lord Bute advised against the match and George abandoned his thoughts of marriage. "I am born for the happiness or misery of a great nation," he wrote, "and consequently must often act contrary to my passions."[16] Nevertheless, attempts by the King to marry George to Princess Sophie Caroline of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel were resisted by him and his mother;[17] Sophie married Frederick, Margrave of Bayreuth, instead.[18]

The following year, at the age of 22, George succeeded to the throne when his grandfather, George II, died suddenly on 25 October 1760, two weeks before his 77th birthday. The search for a suitable wife intensified. On 8 September 1761 in the Chapel Royal, St James's Palace, the King married Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, whom he met on their wedding day.[lower-alpha 4] A fortnight later on 22 September, both were crowned at Westminster Abbey. George never took a mistress (in contrast with his grandfather and his sons), and the couple enjoyed a happy marriage until his mental illness struck.[1][9]

They had 15 children—nine sons and six daughters. In 1762, George purchased Buckingham House (on the site now occupied by Buckingham Palace) for use as a family retreat.[20] His other residences were Kew Palace and Windsor Castle. St James's Palace was retained for official use. He did not travel extensively and spent his entire life in southern England. In the 1790s, the King and his family took holidays at Weymouth, Dorset,[21] which he thus popularised as one of the first seaside resorts in England.[22]

Early reign

George, in his accession speech to Parliament, proclaimed: "Born and educated in this country, I glory in the name of Britain."[23] He inserted this phrase into the speech, written by Lord Hardwicke, to demonstrate his desire to distance himself from his German forebears, who were perceived as caring more for Hanover than for Britain.[24] During George III's lengthy reign, Britain was a constitutional monarchy, ruled by his ministerial government, and prominent men in Parliament.[25]

Although his accession was at first welcomed by politicians of all parties,[lower-alpha 5] the first years of his reign were marked by political instability, largely generated as a result of disagreements over the Seven Years' War.[27] George was also perceived as favouring Tory ministers, which led to his denunciation by the Whigs as an autocrat.[1] On his accession, the Crown lands produced relatively little income; most revenue was generated through taxes and excise duties. George surrendered the Crown Estate to Parliamentary control in return for a civil list annuity for the support of his household and the expenses of civil government.[28]

Claims that he used the income to reward supporters with bribes and gifts[29] are disputed by historians who say such claims "rest on nothing but falsehoods put out by disgruntled opposition".[30] Debts amounting to over £3 million over the course of George's reign were paid by Parliament, and the civil list annuity was increased from time to time.[31] He aided the Royal Academy of Arts with large grants from his private funds,[32] and may have donated more than half of his personal income to charity.[33] Of his art collection, the two most notable purchases are Johannes Vermeer's Lady at the Virginals and a set of Canalettos, but it is as a collector of books that he is best remembered.[34] The King's Library was open and available to scholars and was the foundation of a new national library.[35]

.jpg.webp)

In May 1762, the incumbent Whig government of Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle, was replaced with one led by the Scottish Tory Lord Bute. Bute's opponents worked against him by spreading the calumny that he was having an affair with the King's mother, and by exploiting anti-Scottish sentiment amongst the English.[36] John Wilkes, a member of parliament, published The North Briton, which was both inflammatory and defamatory in its condemnation of Bute and the government. Wilkes was eventually arrested for seditious libel but he fled to France to escape punishment; he was expelled from the House of Commons, and found guilty in absentia of blasphemy and libel.[37] In 1763, after concluding the Peace of Paris which ended the war, Lord Bute resigned, allowing the Whigs under George Grenville to return to power. Britain received enormous concessions, including West Florida. Britain restored to France lucrative slave-sugar islands in the West Indies, including Guadeloupe and Martinique. France ceded Canada to Britain, in addition to all land between the Allegheny Mountains and the Mississippi River, except New Orleans, which was ceded to Spain.[38]

Later that year, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 placed a limit upon the westward expansion of the American colonies and created an Indian reserve. The Proclamation aimed to divert colonial expansion to the north (to Nova Scotia) and to the south (Florida), and protect the British fur trade with the Indians.[39] The Proclamation Line did not bother the majority of settled farmers, but it was unpopular with a vocal minority. This discontent ultimately contributed to conflict between the colonists and the British government.[40] With the American colonists generally unburdened by British taxes, the government thought it appropriate for them to pay towards the defence of the colonies against native uprisings and the possibility of French incursions.[lower-alpha 6]

The central issue for the colonists was not the amount of taxes but whether Parliament could levy a tax without American approval, for there were no American seats in Parliament.[43] The Americans protested that like all Englishmen they had rights to "no taxation without representation". In 1765, Grenville introduced the Stamp Act, which levied a stamp duty on every document in the British colonies in North America. Since newspapers were printed on stamped paper, those most affected by the introduction of the duty were the most effective at producing propaganda opposing the tax.[44]

Meanwhile, the King had become exasperated at Grenville's attempts to reduce the King's prerogatives, and tried, unsuccessfully, to persuade William Pitt the Elder to accept the office of Prime Minister.[45] After a brief illness, which may have presaged his illnesses to come, George settled on Lord Rockingham to form a ministry, and dismissed Grenville.[46]

Lord Rockingham, with the support of Pitt and the King, repealed Grenville's unpopular Stamp Act. Rockingham's government was weak, and he was replaced as prime minister in 1766 by Pitt, whom George created Earl of Chatham. The actions of Lord Chatham and George III in repealing the Act were so popular in America that statues of them both were erected in New York City.[47] Lord Chatham fell ill in 1767, and Augustus FitzRoy, 3rd Duke of Grafton, took over the government. Grafton did not formally become Prime Minister until 1768. That year, John Wilkes returned to England, stood as a candidate in the general election, and came top of the poll in the Middlesex constituency. Wilkes was again expelled from Parliament. He was re-elected and expelled twice more, before the House of Commons resolved that his candidature was invalid and declared the runner-up as the victor.[48] Grafton's government disintegrated in 1770, allowing the Tories led by Lord North to return to power.[49]

George was deeply devout and spent hours in prayer,[50] but his piety was not shared by his brothers. George was appalled by what he saw as their loose morals. In 1770, his brother Prince Henry, Duke of Cumberland and Strathearn, was exposed as an adulterer. The following year, Cumberland married a young widow, Anne Horton. The King considered her inappropriate as a royal bride: she was from a lower social class and German law barred any children of the couple from the Hanoverian succession.[51]

George insisted on a new law that essentially forbade members of the Royal Family from legally marrying without the consent of the Sovereign. The subsequent bill was unpopular in Parliament, including among George's own ministers, but passed as the Royal Marriages Act 1772. Shortly afterwards, another of George's brothers, Prince William Henry, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh, revealed he had been secretly married to Maria, Countess Waldegrave, the illegitimate daughter of Sir Edward Walpole. The news confirmed George's opinion that he had been right to introduce the law: Maria was related to his political opponents. Neither lady was ever received at court.[51]

Lord North's government was chiefly concerned with discontent in America. To assuage American opinion most of the custom duties were withdrawn, except for the tea duty, which in George's words was "one tax to keep up the right [to levy taxes]".[52] In 1773, the tea ships moored in Boston Harbor were boarded by colonists and the tea was thrown overboard, an event that became known as the Boston Tea Party. In Britain, opinion hardened against the colonists, with Chatham now agreeing with North that the destruction of the tea was "certainly criminal".[53]

With the clear support of Parliament, Lord North introduced measures, which were called the Intolerable Acts by the colonists: the Port of Boston was shut down and the charter of Massachusetts was altered so that the upper house of the legislature was appointed by the Crown instead of elected by the lower house.[54] Up to this point, in the words of Professor Peter Thomas, George's "hopes were centred on a political solution, and he always bowed to his cabinet's opinions even when sceptical of their success. The detailed evidence of the years from 1763 to 1775 tends to exonerate George III from any real responsibility for the American Revolution."[55] Though both the Americans and older British historians characterised George as a tyrant, in these years he acted as a constitutional monarch supporting the initiatives of his ministers.[56]

American War of Independence

The American War of Independence was the culmination of the civil and political American Revolution resulting from the American Enlightenment. In the 1760s, a series of acts by Parliament was met with resistance in thirteen of Britain's American colonies. In particular they rejected new taxes levied by Parliament, a body in which they had no direct representation. Locally governed by colonial legislatures, the colonies had previously enjoyed a high level of autonomy in their internal affairs and viewed Parliament's acts as a denial of their rights as Englishmen.[57] Armed conflict between British regulars and colonial militiamen broke out at the Battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775. After petitions to the Crown for intervention with Parliament were ignored, the rebel leaders were declared traitors by the Crown and a year of fighting ensued. Thomas Paine's published work Common Sense abrasively referred to George III as "the Royal Brute of Great Britain".[58]

The colonies declared their independence in July 1776, listing twenty-seven grievances against the British king and legislature while asking the support of the populace. Among George's other offenses, the Declaration charged, "He has abdicated Government here ... He has plundered our seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people." The gilded equestrian statue of the king in New York was pulled down.[59] The British captured the city in 1776 but lost Boston, and the grand strategic plan of invading from Canada and cutting off New England failed with the surrender of British Lieutenant-General John Burgoyne following the battles of Saratoga.[60]

Although Prime Minister Lord North was not an ideal war leader, George III managed to give Parliament a sense of purpose to fight, and Lord North was able to keep his cabinet together. Lord North's cabinet ministers, the Earl of Sandwich, First Lord of the Admiralty, and Lord George Germain, Secretary of State for the Colonies, however, proved to lack leadership skills suited for their positions, which in turn, aided the American war effort.[61]

George III is often accused of obstinately trying to keep Great Britain at war with the revolutionaries in America, despite the opinions of his own ministers.[62] In the words of the British historian George Otto Trevelyan, the King was determined "never to acknowledge the independence of the Americans, and to punish their contumacy by the indefinite prolongation of a war which promised to be eternal."[63] The King wanted to "keep the rebels harassed, anxious, and poor, until the day when, by a natural and inevitable process, discontent and disappointment were converted into penitence and remorse".[64] Later historians defend George by saying in the context of the times no king would willingly surrender such a large territory,[9][65] and his conduct was far less ruthless than contemporary monarchs in Europe.[66] After Saratoga, both Parliament and the British people were in favour of the war; recruitment ran at high levels and although political opponents were vocal, they remained a small minority.[9][67]

With the setbacks in America, Lord North asked to transfer power to Lord Chatham, whom he thought more capable, but George refused to do so; he suggested instead that Chatham serve as a subordinate minister in North's administration, but Chatham refused. He died later in the same year.[68] Lord North was allied to the "King's Friends" in Parliament and believed George III had the right to exercise powers.[69] In early 1778, France (Britain's chief rival) signed a treaty of alliance with the United States and the confrontation soon escalated from "civil war" to something that has been characterized as "world war".[70] The French fleet was able to outrun the British naval blockade of the Mediterranean and sailed to North America.[70] The conflict now affected North America, Europe, and India.[70] The United States and France were joined by Spain in 1779 and the Dutch Republic, while Britain had no major allies of its own, except for the Loyalists and German auxiliaries. Lord Gower and Lord Weymouth both resigned from the government. Lord North again requested that he also be allowed to resign, but he stayed in office at George III's insistence.[71]

During the summer of 1779, a combined French-Spanish naval fleet threatened to invade England and transport 31,000 French troops across the English Channel. George III said that Britain was confronted by the "most serious crisis the nation ever knew." In August, sixty-six warships entered the English channel, but due to sickness, hunger, and adverse winds, the French-Spanish armada lost its nerve, and withdrew, ending the invasion threat.[72]

In late 1779, George III advocated sending more British warships and troops, guarding the English Channel, across the Atlantic, to the West Indies. He boldly said: "We must risk something, otherwise we will only vegetate in this war. I own I wish either with spirit to get through it, or with a crash be ruined." In January 1780, 7,000 British troops, under General Sir John Vaughan, were transported to the West Indies.[73] Nonetheless, opposition to the costly war was increasing, and in June 1780 contributed to disturbances in London known as the Gordon riots.[74]

As late as the siege of Charleston in 1780, Loyalists could still believe in their eventual victory, as British troops inflicted defeats on the Continental forces at the Battle of Camden and the Battle of Guilford Court House.[75] In late 1781, the news of Lord Cornwallis's surrender at the siege of Yorktown reached London; Lord North's parliamentary support ebbed away and he resigned the following year. The King drafted an abdication notice, which was never delivered,[65][76] finally accepted the defeat in North America, and authorized peace negotiations. The Treaties of Paris, by which Britain recognized the independence of the American states and returned Florida to Spain, were signed in 1782 and 1783.[77] In early 1783, George III privately conceded "America is lost!" He reflected that the Northern colonies had developed into Britain's "successful rivals" in commercial trade and fishing.[78] Up to 70,000 Loyalists fled to Canada, the Caribbean, or England after their homes and businesses were looted and destroyed by hostile Americans.[79]

When John Adams was appointed American Minister to London in 1785, George had become resigned to the new relationship between his country and the former colonies. He told Adams, "I was the last to consent to the separation; but the separation having been made and having become inevitable, I have always said, as I say now, that I would be the first to meet the friendship of the United States as an independent power."[80]

William Pitt

With the collapse of Lord North's ministry in 1782, the Whig Lord Rockingham became Prime Minister for the second time but died within months. The King then appointed Lord Shelburne to replace him. Charles James Fox, however, refused to serve under Shelburne, and demanded the appointment of William Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland. In 1783, the House of Commons forced Shelburne from office and his government was replaced by the Fox–North Coalition. Portland became Prime Minister, with Fox and Lord North, as Foreign Secretary and Home Secretary respectively.[9]

The King disliked Fox intensely, for his politics as well as his character: he thought Fox unprincipled and a bad influence on the Prince of Wales.[81] George III was distressed at having to appoint ministers not of his liking, but the Portland ministry quickly built up a majority in the House of Commons, and could not be displaced easily. He was further dismayed when the government introduced the India Bill, which proposed to reform the government of India by transferring political power from the East India Company to Parliamentary commissioners.[82] Although the King actually favoured greater control over the company, the proposed commissioners were all political allies of Fox.[83] Immediately after the House of Commons passed it, George authorised Lord Temple to inform the House of Lords that he would regard any peer who voted for the bill as his enemy. The bill was rejected by the Lords; three days later, the Portland ministry was dismissed, and William Pitt the Younger was appointed Prime Minister, with Temple as his Secretary of State. On 17 December 1783, Parliament voted in favour of a motion condemning the influence of the monarch in parliamentary voting as a "high crime" and Temple was forced to resign. Temple's departure destabilised the government, and three months later the government lost its majority and Parliament was dissolved; the subsequent election gave Pitt a firm mandate.[9]

Signs of illness

Pitt's appointment was a great victory for George. It proved that the King could appoint prime ministers on the basis of his own interpretation of the public mood without having to follow the choice of the current majority in the House of Commons. Throughout Pitt's ministry, George supported many of Pitt's political aims and created new peers at an unprecedented rate to increase the number of Pitt's supporters in the House of Lords.[84] During and after Pitt's ministry, George was extremely popular in Britain.[85] The British people admired him for his piety and for remaining faithful to his wife.[86] He was fond of his children and was devastated at the death of two of his sons in infancy, in 1782 and 1783 respectively.[87] Nevertheless, he set his children a strict regimen. They were expected to attend rigorous lessons from seven in the morning and to lead lives of religious observance and virtue.[88] When his children strayed from George's principles of righteousness, as his sons did as young adults, he was dismayed and disappointed.[89]

By this time, George's health was deteriorating. He had a mental illness characterised by acute mania, which was possibly a symptom of the genetic disease porphyria,[90] although this has been questioned: the original authors of the theory, Ida Macalpine and her son Richard Hunter, were "highly selective" in choosing evidence to support their claim and the most likely diagnosis, using more recent techniques, is bipolar disorder.[91][92][93] However, a study of samples of the King's hair published in 2005 revealed high levels of arsenic, a cause of metabolic blood disorders and thus a possible trigger for porphyria. The source of the arsenic is not known, but it could have been a component of medicines or cosmetics.[94]

The King may have had a brief episode of disease in 1765, but a longer episode began in the summer of 1788. At the end of the parliamentary session, he went to Cheltenham Spa to recuperate. It was the furthest he had ever been from London—just short of 100 miles (150 km)—but his condition worsened. In November of that year, he became seriously deranged, sometimes speaking for many hours without pause, causing him to foam at the mouth and his voice to become hoarse. George would frequently repeat himself and write sentences with over 400 words at a time, and his vocabulary became "more complex, creative and colourful", possible symptoms of bipolar disorder.[95] His doctors were largely at a loss to explain his illness, and spurious stories about his condition spread, such as the claim that he shook hands with a tree in the mistaken belief that it was the King of Prussia.[96] Treatment for mental illness was primitive by modern standards, and the King's doctors, who included Francis Willis, treated the King by forcibly restraining him until he was calm, or applying caustic poultices to draw out "evil humours".[97]

In the reconvened Parliament, Fox and Pitt wrangled over the terms of a regency during the King's incapacity. While both agreed that it would be most reasonable for the Prince of Wales to act as regent, Fox suggested, to Pitt's consternation, that it was the Prince's absolute right to act on his ill father's behalf with full powers. Pitt, fearing he would be removed from office if the Prince of Wales were empowered, argued that it was for Parliament to nominate a regent, and wanted to restrict the regent's authority.[98] In February 1789, the Regency Bill, authorising the Prince of Wales to act as regent, was introduced and passed in the House of Commons, but before the House of Lords could pass the bill, George III recovered.[99]

Slavery

According to the historian Andrew Roberts, George wrote a document in the 1750s "denouncing all of the arguments for slavery, and calling them an execration and ridiculous and 'absurd'." "George never bought or sold a slave in his life. He never invested in any of the companies that did such a thing. He signed legislation to abolish slavery."[100]

During George III's lengthy reign, a coalition of abolitionists and Atlantic slave uprisings caused the British public to spurn slavery, but George and his son, the Duke of Clarence, supported the efforts of the London Society of West India Planters and Merchants to delay the abolition of the British slave trade for almost 20 years.[101][102] Pitt conversely wished to see slavery abolished but, because the cabinet was divided and the King was in the pro-slavery camp,[103][104] Pitt decided to refrain from making abolition official government policy. Instead, he worked toward abolition in an individual capacity.[105]

On 7 November 1775, during the American War of Independence, John Murray, Lord Dunmore, issued a proclamation that freed slaves of Rebel masters who would enlist to put down the colonial rebellion. Dunmore was the last Royal Governor of Virginia, appointed by King George III in July 1771. Dunmore's Proclamation inspired slaves to escape from captivity and fight for the British. On 30 June 1779, George III's Commanding General Henry Clinton broadened Dunmore's proclamation with his Philipsburg Proclamation. For all colonial slaves who fled their Rebel masters, Clinton forbade their recapture and resale, giving them protection by the British military. Approximately 20,000 freed slaves joined the British, fighting for George III. In 1783, given British certificates of freedom, 3,000 former slaves, including their families, settled in Nova Scotia.[106]

Between 1791 and 1800, almost 400,000 Africans were shipped to the Americas, by 1,340 slaving voyages, mounted from British ports, including Liverpool and Bristol. On 25 March 1807 George III signed into law An Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, under which the transatlantic slave trade was banned in all of the British Empire.[107]

French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

.jpg.webp)

After George's recovery, his popularity, and that of Pitt, continued to increase at the expense of Fox and the Prince of Wales.[108] His humane and understanding treatment of two insane assailants, Margaret Nicholson in 1786 and John Frith in 1790, contributed to his popularity.[109] James Hadfield's failed attempt to shoot the King in the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, on 15 May 1800 was not political in origin but motivated by the apocalyptic delusions of Hadfield and Bannister Truelock. George seemed unperturbed by the incident, so much so that he fell asleep in the interval.[110]

The French Revolution of 1789, in which the French monarchy had been overthrown, worried many British landowners. France declared war on Great Britain in 1793; in response to the crisis, George allowed Pitt to increase taxes, raise armies, and suspend the right of habeas corpus. The First Coalition to oppose revolutionary France, which included Austria, Prussia, and Spain, broke up in 1795 when Prussia and Spain made separate peace with France.[111] The Second Coalition, which included Austria, Russia, and the Ottoman Empire, was defeated in 1800. Only Great Britain was left fighting Napoleon Bonaparte, the First Consul of the French Republic.

A brief lull in hostilities allowed Pitt to concentrate effort on Ireland, where there had been an uprising and attempted French landing in 1798.[112] In 1800, the British and Irish Parliaments passed an Act of Union that took effect on 1 January 1801 and united Great Britain and Ireland into a single state, known as the "United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland". George used the opportunity to abandon the title "king of France", which English and British Sovereigns had maintained since the reign of Edward III.[113] It was suggested that George adopt the title "Emperor of the British Isles", but he refused.[9] As part of his Irish policy, Pitt planned to remove certain legal disabilities that applied to Roman Catholics. George III claimed that to emancipate Catholics would be to violate his coronation oath, in which Sovereigns promise to maintain Protestantism.[114] Faced with opposition to his religious reform policies from both the King and the British public, Pitt threatened to resign.[115] At about the same time, the King had a relapse of his previous illness, which he blamed on worry over the Catholic question.[116] On 14 March 1801, Pitt was formally replaced by the Speaker of the House of Commons, Henry Addington. Addington opposed emancipation, instituted annual accounts, abolished income tax and began a programme of disarmament. In October 1801, he made peace with the French, and in 1802 signed the Treaty of Amiens.[117]

George did not consider the peace with France as real; in his view it was an "experiment".[118] The war resumed in 1803, but public opinion distrusted Addington to lead the nation in war, and instead favoured Pitt. An invasion of England by Napoleon seemed imminent, and a massive volunteer movement arose to defend England against the French. George's review of 27,000 volunteers in Hyde Park, London, on 26 and 28 October 1803 and at the height of the invasion scare, attracted an estimated 500,000 spectators on each day.[119] The Times said: "The enthusiasm of the multitude was beyond all expression."[120] A courtier wrote on 13 November that "The King is really prepared to take the field in case of attack, his beds are ready and he can move at half an hour's warning."[121] George wrote to his friend Bishop Hurd, "We are here in daily expectation that Bonaparte will attempt his threatened invasion ... Should his troops effect a landing, I shall certainly put myself at the head of mine, and my other armed subjects, to repel them."[122] After Admiral Lord Nelson's famous naval victory at the Battle of Trafalgar, the possibility of invasion was extinguished.[123]

In 1804, George's recurrent illness returned; after his recovery, Addington resigned and Pitt regained power. Pitt sought to appoint Fox to his ministry, but George refused. Lord Grenville perceived an injustice to Fox, and refused to join the new ministry.[9] Pitt concentrated on forming a coalition with Austria, Russia, and Sweden. This Third Coalition, however, met the same fate as the First and Second Coalitions, collapsing in 1805. The setbacks in Europe took a toll on Pitt's health, and he died in 1806, reopening the question of who should serve in the ministry. Grenville became Prime Minister, and his "Ministry of All the Talents" included Fox. Grenville pushed through the Slave Trade Act 1807, which passed both houses of Parliament with large majorities.[103] The King was conciliatory towards Fox, after being forced to capitulate over his appointment. After Fox's death in September 1806, the King and ministry were in open conflict. To boost recruitment, the ministry proposed a measure in February 1807 whereby Roman Catholics would be allowed to serve in all ranks of the Armed Forces. George instructed them not only to drop the measure, but also to agree never to set up such a measure again. The ministers agreed to drop the measure then pending, but refused to bind themselves in the future.[124] They were dismissed and replaced by William Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland, as the nominal Prime Minister, with actual power being held by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Spencer Perceval. Parliament was dissolved, and the subsequent election gave the ministry a strong majority in the House of Commons. George III made no further major political decisions during his reign; the replacement of Portland by Perceval in 1809 was of little real significance.[125]

Final years, illnesses and death

In late 1810, at the height of his popularity,[126] King George, already virtually blind with cataracts and in pain from rheumatism, suffered a relapse into his mental disorder and became dangerously ill. In his view the malady had been triggered by stress over the death of his youngest and favourite daughter, Princess Amelia.[127] The Princess's nurse reported that "the scenes of distress and crying every day ... were melancholy beyond description."[128] George accepted the need for the Regency Act 1811,[129] and the Prince of Wales (later George IV) acted as Regent for the remainder of the King's life. Despite signs of a recovery in May 1811, by the end of the year George III had become permanently insane, and lived in seclusion at Windsor Castle until his death.[130]

Prime Minister Spencer Perceval was assassinated in 1812 and was replaced by Lord Liverpool. Liverpool oversaw British victory in the Napoleonic Wars. The subsequent Congress of Vienna led to significant territorial gains for Hanover, which was elevated from an electorate to a kingdom.

Meanwhile, George's health deteriorated. He developed dementia, and became completely blind and increasingly deaf. He was incapable of knowing or understanding that he was declared King of Hanover in 1814, or that his wife died in 1818.[131] At Christmas 1819, he spoke nonsense for 58 hours, and for the last few weeks of his life was unable to walk.[132] He died, of pneumonia, at Windsor Castle at 8:38 pm on 29 January 1820, six days after the death of his fourth son Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn.[133] His favourite son, Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany, was with him.[134] George III lay in state for two days, and his funeral and interment took place on 16 February in St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle.[133][135][136]

Legacy

George was succeeded in turn by two of his sons, George IV and William IV, who both died without surviving legitimate children, leaving the throne to Victoria, the only legitimate child of his fourth son Prince Edward.

George III lived for 81 years and 239 days and reigned for 59 years and 96 days: both his life and his reign were longer than those of any of his predecessors and subsequent kings; only Queens Victoria and Elizabeth II lived and reigned longer.

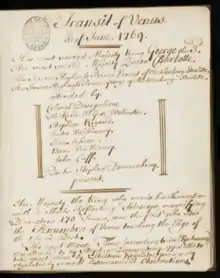

George III was dubbed "Farmer George" by satirists, at first to mock his interest in mundane matters rather than politics, but later to portray him as a man of the people, contrasting his homely thrift with his son's grandiosity.[137] Under George III, the British Agricultural Revolution reached its peak and great advances were made in fields such as science and industry. There was unprecedented growth in the rural population, which in turn provided much of the workforce for the concurrent Industrial Revolution.[138] George's collection of mathematical and scientific instruments is now owned by King's College London but housed in the Science Museum, London, to which it has been on long-term loan since 1927. He had the King's Observatory built in Richmond-upon-Thames for his own observations of the 1769 transit of Venus. When William Herschel discovered Uranus in 1781, he at first named it Georgium Sidus (George's Star) after the King, who later funded the construction and maintenance of Herschel's 1785 40-foot telescope, which at the time was the biggest ever built.

George III hoped that "the tongue of malice may not paint my intentions in those colours she admires, nor the sycophant extoll me beyond what I deserve"[139] but, in the popular mind, George III has been both demonised and praised. While very popular at the start of his reign, by the mid-1770s George had lost the loyalty of revolutionary American colonists,[140] though it has been estimated that as many as half of the colonists remained loyal.[141] The grievances in the United States Declaration of Independence were presented as "repeated injuries and usurpations" that he had committed to establish an "absolute Tyranny" over the colonies. The Declaration's wording has contributed to the American public's perception of George as a tyrant. Contemporary accounts of George III's life fall into two camps: one demonstrating "attitudes dominant in the latter part of the reign, when the King had become a revered symbol of national resistance to French ideas and French power", while the other "derived their views of the King from the bitter partisan strife of the first two decades of the reign, and they expressed in their works the views of the opposition".[142]

Building on the latter of these two assessments, British historians of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, such as Trevelyan and Erskine May, promoted hostile interpretations of George III's life. However, in the mid-twentieth century the work of Lewis Namier, who thought George was "much maligned", started a re-evaluation of the man and his reign.[143] Scholars of the later twentieth century, such as Butterfield and Pares, and Macalpine and Hunter,[144] are inclined to treat George sympathetically, seeing him as a victim of circumstance and illness. Butterfield rejected the arguments of his Victorian predecessors with withering disdain: "Erskine May must be a good example of the way in which an historian may fall into error through an excess of brilliance. His capacity for synthesis, and his ability to dovetail the various parts of the evidence ... carried him into a more profound and complicated elaboration of error than some of his more pedestrian predecessors ... he inserted a doctrinal element into his history which, granted his original aberrations, was calculated to project the lines of his error, carrying his work still further from centrality or truth."[145] In pursuing war with the American colonists, George III believed he was defending the right of an elected Parliament to levy taxes, rather than seeking to expand his own power or prerogatives.[146] In the opinion of modern scholars, during the long reign of George III, the monarchy continued to lose its political power and grew as the embodiment of national morality.[9]

Titles, styles, honours and arms

Titles and styles

- 4 June 1738 – 31 March 1751: His Royal Highness Prince George[147]

- 31 March 1751 – 20 April 1751: His Royal Highness The Duke of Edinburgh

- 20 April 1751 – 25 October 1760: His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales

- 25 October 1760 – 29 January 1820: His Majesty The King

In Great Britain, George III used the official style "George the Third, by the Grace of God, King of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, Defender of the Faith, and so forth". In 1801, when Great Britain united with Ireland, he dropped the title of king of France, which had been used for every English monarch since Edward III's claim to the French throne in the medieval period.[113] His style became "George the Third, by the Grace of God, of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland King, Defender of the Faith."[148]

In Germany, he was "Duke of Brunswick and Lüneburg, Arch-Treasurer and Prince-elector of the Holy Roman Empire" (Herzog von Braunschweig und Lüneburg, Erzschatzmeister und Kurfürst des Heiligen Römischen Reiches[149]) until the end of the empire in 1806. He then continued as duke until the Congress of Vienna declared him "King of Hanover" in 1814.[148]

Honours

.svg.png.webp) Great Britain: Royal Knight of the Garter, 22 June 1749[150]

Great Britain: Royal Knight of the Garter, 22 June 1749[150].svg.png.webp) Ireland: Founder of the Most Illustrious Order of St. Patrick, 5 February 1783[151]

Ireland: Founder of the Most Illustrious Order of St. Patrick, 5 February 1783[151]

Arms

Before his succession, George was granted the royal arms differenced by a label of five points Azure, the centre point bearing a fleur-de-lis Or on 27 July 1749. Upon his father's death, and along with the dukedom of Edinburgh and the position of heir-apparent, he inherited his difference of a plain label of three points Argent. In an additional difference, the crown of Charlemagne was not usually depicted on the arms of the heir, only on the Sovereign's.[152]

From his succession until 1800, George bore the royal arms: Quarterly, I Gules three lions passant guardant in pale Or (for England) impaling Or a lion rampant within a tressure flory-counter-flory Gules (for Scotland); II Azure three fleurs-de-lys Or (for France); III Azure a harp Or stringed Argent (for Ireland); IV tierced per pale and per chevron (for Hanover), I Gules two lions passant guardant Or (for Brunswick), II Or a semy of hearts Gules a lion rampant Azure (for Lüneburg), III Gules a horse courant Argent (for Saxony), overall an escutcheon Gules charged with the crown of Charlemagne Or (for the dignity of Archtreasurer of the Holy Roman Empire).[153][154]

Following the Acts of Union 1800, the royal arms were amended, dropping the French quartering. They became: Quarterly, I and IV England; II Scotland; III Ireland; overall an escutcheon of Hanover surmounted by an electoral bonnet.[155] In 1816, after the Electorate of Hanover became a kingdom, the electoral bonnet was changed to a crown.[156]

Coat of arms from 1749 to 1751

Coat of arms from 1749 to 1751.svg.png.webp) Coat of arms from 1751 to 1760 as Prince of Wales

Coat of arms from 1751 to 1760 as Prince of Wales.svg.png.webp) Coat of arms used from 1760 to 1801 as King of Great Britain

Coat of arms used from 1760 to 1801 as King of Great Britain.svg.png.webp) Coat of arms used from 1801 to 1816 as King of the United Kingdom

Coat of arms used from 1801 to 1816 as King of the United Kingdom.svg.png.webp) Coat of arms used from 1816 until death, also as King of Hanover

Coat of arms used from 1816 until death, also as King of Hanover

Issue

| British Royalty |

| House of Hanover |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

| George III |

|

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes[157] |

|---|---|---|---|

| George IV | 12 August 1762 | 26 June 1830 | Prince of Wales 1762–1820; married 1795, Princess Caroline of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel; had one daughter: Princess Charlotte |

| Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany | 16 August 1763 | 5 January 1827 | Married 1791, Princess Frederica of Prussia; no issue |

| William IV | 21 August 1765 | 20 June 1837 | Duke of Clarence and St Andrews; married 1818, Princess Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen; no surviving legitimate issue, but had illegitimate children with Dorothea Jordan |

| Charlotte, Princess Royal | 29 September 1766 | 6 October 1828 | Married 1797, King Frederick of Württemberg; no surviving issue |

| Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn | 2 November 1767 | 23 January 1820 | Married 1818, Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld; Queen Victoria was their daughter; descendants include Charles III, Felipe VI of Spain, Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden, Harald V of Norway and Margrethe II of Denmark. |

| Princess Augusta Sophia | 8 November 1768 | 22 September 1840 | Never married, no issue |

| Princess Elizabeth | 22 May 1770 | 10 January 1840 | Married 1818, Frederick, Landgrave of Hesse-Homburg; no issue |

| Ernest Augustus, King of Hanover | 5 June 1771 | 18 November 1851 | Duke of Cumberland and Teviotdale 1799–1851; married 1815, Princess Friederike of Mecklenburg-Strelitz; had issue; descendants include Prince Ernst August of Hanover, Constantine II of Greece and Felipe VI of Spain. |

| Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex | 27 January 1773 | 21 April 1843 | (1) Married 1793, in contravention of the Royal Marriages Act 1772, Lady Augusta Murray; had issue; marriage annulled 1794 (2) Married 1831, Lady Cecilia Buggin (later Duchess of Inverness in her own right); no issue |

| Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge | 24 February 1774 | 8 July 1850 | Married 1818, Princess Augusta of Hesse-Kassel; had issue; descendants include Charles III |

| Princess Mary | 25 April 1776 | 30 April 1857 | Married 1816, Prince William Frederick, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh; no issue |

| Princess Sophia | 3 November 1777 | 27 May 1848 | Never married, no issue |

| Prince Octavius | 23 February 1779 | 3 May 1783 | Died in childhood |

| Prince Alfred | 22 September 1780 | 20 August 1782 | Died in childhood |

| Princess Amelia | 7 August 1783 | 2 November 1810 | Never married, no issue |

Ancestry

| Ancestors of George III[158] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Cultural depictions of George III

- List of mentally ill monarchs

Notes

- United Kingdom from 1 January 1801, following the Acts of Union 1800.

- King from 12 October 1814.

- All dates in this article are in the New Style Gregorian calendar. George was born on 24 May in the Old Style Julian calendar used in Great Britain until 1752.

- George was falsely said to have married Hannah Lightfoot, a Quaker, on 17 April 1759, prior to his marriage to Charlotte, and to have had at least one child by her. However, Lightfoot had married Isaac Axford in 1753, and had died in or before 1759, so there could have been no legal marriage or children. The jury at the 1866 trial of Lavinia Ryves, the daughter of imposter Olivia Serres who pretended to be "Princess Olive of Cumberland", unanimously found that a supposed marriage certificate produced by Ryves was a forgery.[19]

- For example, the letters of Horace Walpole written at the time of the accession defended George but Walpole's later memoirs were hostile.[26]

- An American taxpayer would pay a maximum of sixpence a year, compared to an average of twenty-five shillings (50 times as much) in England.[41] In 1763, the total revenue from America amounted to about £1 800, while the estimated annual cost of the military in America was put at £225 000. By 1767, it had risen to £400 000.[42]

References

- "George III". Official website of the British monarchy. Royal Household. 31 December 2015. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- Brooke, p. 314; Fraser, p. 277.

- Butterfield, p. 9.

- Hibbert, p. 8.

- The Third Register Book of the Parish of St James in the Liberty of Westminster For Births & Baptisms. 1723–1741. 24 May 1738.

- "No. 7712". The London Gazette. 20 June 1738. p. 2.

- Brooke, pp. 23–41.

- Brooke, pp. 42–44, 55.

- Cannon, John (September 2004). "George III (1738–1820)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/10540. Retrieved 29 October 2008. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (Subscription required).

- Sedgwick, pp. ix–x.

- "No. 9050". The London Gazette. 16 April 1751. p. 1.

- Hibbert, pp. 3–15.

- Brooke, pp. 51–52; Hibbert, pp. 24–25.

- Bullion, John L. (2004). "Augusta, princess of Wales (1719–1772)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/46829. Retrieved 17 September 2008 (Subscription required).

- Ayling, p. 33.

- Ayling, p. 54; Brooke, pp. 71–72.

- Ayling, pp. 36–37; Brooke, p. 49; Hibbert, p. 31.

- Benjamin, p. 62.

- "Documents relating to the case". The National Archives. Retrieved 14 October 2008.

- Ayling, pp. 85–87.

- Ayling, p. 378; Cannon and Griffiths, p. 518.

- Watson, p. 549.

- Brooke, p. 612.

- Brooke, p. 156; Simms and Riotte, p. 58.

- Baer, George III (1738–1820), December 22, 2021

- Butterfield, pp. 22, 115–117, 129–130.

- Hibbert, p. 86; Watson, pp. 67–79.

- "Our history". The Crown Estate. 2004. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- Kelso, Paul (6 March 2000). "The royal family and the public purse". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- Watson, p. 88; this view is also shared by Brooke (see for example p. 99).

- Medley, p. 501.

- Ayling, p. 194; Brooke, pp. xv, 214, 301.

- Brooke, p. 215.

- Ayling, p. 195.

- Ayling, pp. 196–198.

- Brooke, p. 145; Carretta, pp. 59, 64 ff.; Watson, p. 93.

- Brooke, pp. 146–147.

- Willcox & Arnstein (1988), pp. 131–132.

- Chernow, p. 137.

- Watson, pp. 183–184.

- Cannon and Griffiths, p. 505; Hibbert, p. 122.

- Cannon and Griffiths, p. 505.

- Black, p. 82.

- Watson, pp. 184–185.

- Ayling, pp. 122–133; Hibbert, pp. 107–109; Watson, pp. 106–111.

- Ayling, pp. 122–133; Hibbert, pp. 111–113.

- Ayling, p. 137; Hibbert, p. 124.

- Ayling, pp. 154–160; Brooke, pp. 147–151.

- Ayling, pp. 167–168; Hibbert, p. 140.

- Brooke, p. 260; Fraser, p. 277.

- Brooke, pp. 272–282; Cannon and Griffiths, p. 498.

- Hibbert, p. 141.

- Hibbert, p. 143.

- Watson, p. 197.

- Thomas, p. 31.

- Ayling, p. 121.

- Taylor (2016), pp. 91-100

- Chernow, pp. 214–215.

- Carretta, pp. 97–98, 367.

- O'Shaughnessy, Andrew Jackson (2014). The Men Who Lost America: British Leadership, the American Revolution, and the Fate of the Empire. pp. 158–164.

- Willcox & Arnstein (1988), p. 162.

- O'Shaughnessy, ch 1.

- Trevelyan, vol. 1 p. 4.

- Trevelyan, vol. 1 p. 5.

- Cannon and Griffiths, pp. 510–511.

- Brooke, p. 183.

- Brooke, pp. 180–182, 192, 223.

- Hibbert, pp. 156–157.

- Willcox & Arnstein, p. 157.

- Willcox & Arnstein, pp. 161, 165.

- Ayling, pp. 275–276.

- Taylor (2016), p.287

- Taylor (2016), p. 290

- Ayling, p. 284.

- The Oxford Illustrated History of the British Army (1994) p. 129.

- Brooke, p. 221.

- U.S. Department of State, Treaty of Paris, 1783. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- Bullion, George III on Empire, 1783, p. 306.

- Roos, Dave (7 October 2021). "Famous Loyalists of the Revolutionary War Era". history.com. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- Adams, C.F., ed. (1850–1856), The works of John Adams, second president of the United States, vol. VIII, pp. 255–257, quoted in Ayling, p. 323 and Hibbert, p. 165.

- e.g. Ayling, p. 281.

- Hibbert, p. 243; Pares, p. 120.

- Brooke, pp. 250–251.

- Watson, pp. 272–279.

- Brooke, p. 316; Carretta, pp. 262, 297.

- Brooke, p. 259.

- Ayling, p. 218.

- Ayling, p. 220.

- Ayling, pp. 222–230, 366–376.

- Röhl, Warren, and Hunt.

- Peters, Timothy J.; Wilkinson, D. (2010). "King George III and porphyria: a clinical re-examination of the historical evidence". History of Psychiatry. 21 (1): 3–19. doi:10.1177/0957154X09102616. PMID 21877427. S2CID 22391207.

- Peters, T. (June 2011). "King George III, bipolar disorder, porphyria and lessons for historians". Clinical Medicine. 11 (3): 261–264. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.11-3-261. PMC 4953321. PMID 21902081.

- Rentoumi, V.; Peters, T.; Conlin, J.; Gerrard, P. (2017). "The acute mania of King George III: A computational linguistic analysis". PLOS One. 3 (12): e0171626. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1271626R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0171626. PMC 5362044. PMID 28328964.

- Cox, Timothy M.; Jack, N.; Lofthouse, S.; Watling, J.; Haines, J.; Warren, M. J. (2005). "King George III and porphyria: an elemental hypothesis and investigation". The Lancet. 366 (9482): 332–335. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66991-7. PMID 16039338. S2CID 13109527.

- "Was George III a manic depressive?". BBC News. 15 April 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- Ayling, pp. 329–335; Brooke, pp. 322–328; Fraser, pp. 281–282; Hibbert, pp. 262–267.

- Ayling, pp. 334–343; Brooke, p. 332; Fraser, p. 282.

- Ayling, pp. 338–342; Hibbert, p. 273.

- Ayling, p. 345.

- Why Andrew Roberts Wants Us to Reconsider King George III, Isaac Chotiner, The New Yorker, 9 November 2021, accessed 5 December 2021

- Newman, Brooke (28 July 2020). "Throne of Blood". slate.com. Slate. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- Rodriguez, Junius P. (26 March 2015). Encyclopedia of Emancipation and Abolition in the Transatlantic World. Routledge. ISBN 9781317471806 – via Google Books.

- "Reasons for the success of the abolitionist campaign in 1807". BBC. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- "Black Abolitionists and the end of the transatlantic slave trade". Black History Month 2019.

- Ditchfield, G. (31 October 2002). George III: An Essay in Monarchy. Springer. ISBN 9780230599437 – via Google Books.

- Klein, Christopher (13 February 2020). "The Ex-Slaves Who Fought with the British". History. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- "Transatlantic slave trade and abolition". Royal Museums Greenwich. 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- Ayling, pp. 349–350; Carretta, p. 285; Fraser, p. 282; Hibbert, pp. 301–302; Watson, p. 323.

- Carretta, p. 275.

- Ayling, pp. 181–182; Fraser, p. 282.

- Ayling, pp. 395–396; Watson, pp. 360–377.

- Ayling, pp. 408–409.

- Weir, p. 286.

- Ayling, p. 411.

- Hibbert, p. 313.

- Ayling, p. 414; Brooke, p. 374; Hibbert, p. 315.

- Watson, pp. 402–409.

- Ayling, p. 423.

- Colley, p. 225.

- The Times, 27 October 1803, p. 2.

- Brooke, p. 597.

- Letter of 30 November 1803, quoted in Wheeler and Broadley, p. xiii.

- "Nelson, Trafalgar, and those who served". National Archives. Retrieved 31 October 2009.

- Pares, p. 139.

- Ayling, pp. 441–442.

- Brooke, p. 381; Carretta, p. 340.

- Hibbert, p. 396.

- Hibbert, p. 394.

- Brooke, p. 383; Hibbert, pp. 397–398.

- Fraser, p. 285; Hibbert, pp. 399–402.

- Ayling, pp. 453–455; Brooke, pp. 384–385; Hibbert, p. 405.

- Hibbert, p. 408.

- Black, p. 410.

- Letter from Duke of York to George IV, quoted in Brooke, p. 386.

- "Royal Burials in the Chapel since 1805". St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle. Dean and Canons of Windsor. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- Brooke, p. 387.

- Carretta, pp. 92–93, 267–273, 302–305, 317.

- Watson, pp. 10–11.

- Brooke, p. 90.

- Carretta, pp. 99–101, 123–126.

- Ayling, p. 247.

- Reitan, p. viii.

- Reitan, pp. xii–xiii.

- Macalpine, Ida; Hunter, Richard A. (1991) [1969]. George III and the Mad-Business. Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-5279-7

- Butterfield, p. 152.

- Brooke, pp. 175–176.

- The London Gazette consistently refers to the young prince as "His Royal Highness Prince George" "No. 8734". The London Gazette. 5 April 1748. p. 3. "No. 8735". The London Gazette. 9 April 1748. p. 2. "No. 8860". The London Gazette. 20 June 1749. p. 2. "No. 8898". The London Gazette. 31 October 1749. p. 3. "No. 8902". The London Gazette. 17 November 1749. p. 3. "No. 8963". The London Gazette. 16 June 1750. p. 1. "No. 8971". The London Gazette. 14 July 1750. p. 1.

- Brooke, p. 390.

- Marquardt, Bernd (28 July 2018). Universalgeschichte des Staates: von der vorstaatlichen Gesellschaft zum Staat der Industriegesellschaft. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 9783643900043 – via Google Books.

- Shaw, Wm. A. (1906) The Knights of England, I, London, p. 44.

- Shaw, p. ix.

- Velde, François (5 August 2013). "Marks of Cadency in the British Royal Family". Heraldica. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- See, for example, Berry, William (1810). An introduction to heraldry containing the rudiments of the science. pp. 110–111.

- Pinches, John Harvey; Pinches, Rosemary (1974). The Royal Heraldry of England. Heraldry Today. Slough, Buckinghamshire: Hollen Street Press. pp. 215–216. ISBN 978-0-900455-25-4.

- "No. 15324". The London Gazette. 30 December 1800. p. 2.

- "No. 17149". The London Gazette. 29 June 1816. p. 1.

- Kiste, John Van der (19 January 2004). George III's Children. The History Press. p. 205. ISBN 9780750953825.

- Genealogie ascendante jusqu'au quatrieme degre inclusivement de tous les Rois et Princes de maisons souveraines de l'Europe actuellement vivans [Genealogy up to the fourth degree inclusive of all the Kings and Princes of sovereign houses of Europe currently living] (in French). Bourdeaux: Frederic Guillaume Birnstiel. 1768. p. 4.

Bibliography

- Ayling, Stanley Edward (1972). George the Third. London: Collins. ISBN 0-00-211412-7.

- Benjamin, Lewis Saul (1907). Farmer George. Pitman and Sons.

- Baer, Marc (22 December 2021). "George III (1738–1820)". Encyclopedia Virginia.

- Bullion, John L. (1994). "George III on Empire, 1783". The William and Mary Quarterly. Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture. 51 (2): 305–310. doi:10.2307/2946866. JSTOR 2946866.

- Black, Jeremy (2006). George III: America's Last King. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-11732-9.

- Brooke, John (1972). King George III. London: Constable. ISBN 0-09-456110-9.

- Butterfield, Herbert (1957). George III and the Historians. London: Collins.

- Cannon, John (2004). "George III (1738–1820)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/10540. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Cannon, John; Griffiths, Ralph (1988). The Oxford Illustrated History of the British Monarchy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822786-8.

- Carretta, Vincent (1990). George III and the Satirists from Hogarth to Byron. Athens, Georgia: The University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0-8203-1146-4.

- Chernow, Ron (2010). Washington: A Life. Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1-59420-266-7.

- Colley, Linda (2005). Britons: Forging the Nation, 1707–1837. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300107595.

- Fraser, Antonia (1975). The Lives of the Kings and Queen of England. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-76911-1.

- Hibbert, Christopher (1999). George III: A Personal History. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-025737-3.

- Medley, Dudley Julius (1902). A Student's Manual of English Constitutional History. p. 501.

- O'Shaughnessy, Andrew Jackson (2013). The Men Who Lost America: British Leadership, the American Revolution, and the Fate of the Empire. ISBN 9780300191073.

- Pares, Richard (1953). King George III and the Politicians. Oxford University Press.

- Reitan, E. A., ed. (1964). George III, Tyrant Or Constitutional Monarch?. Boston: D. C. Heath and Company. A compilation of essays encompassing the major assessments of George III up to 1964

- Röhl, John C. G.; Warren, Martin; Hunt, David (1998). Purple Secret: Genes, "Madness" and the Royal Houses of Europe. London: Bantam Press. ISBN 0-593-04148-8.

- Sedgwick, Romney, ed. (1903). Letters from George III to Lord Bute, 1756–1766. Macmillan.

- Simms, Brendan; Riotte, Torsten (2007). The Hanoverian Dimension in British History, 1714–1837. Cambridge University Press.

- Taylor, Alan (2016). American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-393-35476-8.

- Thomas, Peter D. G. (1985). "George III and the American Revolution". History. 70 (228): 16–31. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.1985.tb02477.x.

- Trevelyan, George (1912). George the Third and Charles Fox: The Concluding Part of the American Revolution. New York: Longmans, Green.

- Watson, J. Steven (1960). The Reign of George III, 1760–1815. London: Oxford University Press.

- Weir, Alison (1996). Britain's Royal Families: The Complete Genealogy (Revised ed.). London: Random House. ISBN 0-7126-7448-9.

- Wheeler, H. F. B.; Broadley, A. M. (1908). Napoleon and the Invasion of England. Volume I. London: John Lane The Bodley Head.

- Willcox, William B.; Arnstein, Walter L. (1988). The Age of Aristocracy 1688 to 1830 (Fifth ed.). D.C. Heath and Company. ISBN 0-669-13423-6.

Further reading

- Black, Jeremy (1996). "Could the British Have Won the American War of Independence?". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 74 (299): 145–154. JSTOR 44225322. online 90-minute video lecture given at Ohio State in 2006; requires Real Player

- Butterfield, Herbert (1965). "Some Reflections on the Early Years of George III's Reign". Journal of British Studies. 4 (2): 78–101. doi:10.1086/385501. JSTOR 175147. S2CID 162958860.

- Ditchfield, G. M. (31 October 2002). George III: An Essay in Monarchy. ISBN 9780333919620.

- Golding, Christopher T. (2017). At Water's Edge: Britain, Napoleon, and the World, 1793–1815. Temple University Press.

- Hadlow, Janice (2014). A Royal Experiment: The Private Life of King George III. Henry Holt and Company.

- Hecht, J. Jean (1966). "The Reign of George III in Recent Historiography". In Furber, Elizabeth Chapin (ed.). Changing views on British history: essays on historical writing since 1939. Harvard University Press. pp. 206–234.

- Macalpine, Ida; Hunter, Richard (1966). "The 'insanity' of King George III: a classic case of porphyria". Br. Med. J. 1 (5479): 65–71. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5479.65. PMC 1843211. PMID 5323262.

- Macalpine, I.; Hunter, R.; Rimington, C. (1968). "Porphyria in the Royal Houses of Stuart, Hanover, and Prussia". British Medical Journal. 1 (5583): 7–18. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5583.7. PMC 1984936. PMID 4866084.

- Namier, Lewis B. (1955). "King George III: A Study in Personality". Personalities and Power. London: Hamish Hamilton.

- O'Shaughnessy, Andrew Jackson (Spring 2004). "'If Others Will Not Be Active, I Must Drive': George III and the American Revolution". Early American Studies. 2 (1): iii, 1–46. doi:10.1353/eam.2007.0037. S2CID 143613757.

- Roberts, Andrew (2021). The Last King of America: The Misunderstood Reign of George III. Viking Press. ISBN 978-1984879264.

- Robertson, Charles Grant (1911). England under the Hanoverians. London: Methuen.

- Robson, Eric (1952). "The American Revolution Reconsidered". History Today. 2 (2): 126–132. British views

- Smith, Robert A. (1984). "Reinterpreting the Reign of George III". In Schlatter, Richard (ed.). Recent Views on British History: Essays on Historical Writing since 1966. Rutgers University Press. pp. 197–254.

External links

- Portraits of King George III at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Georgian Papers Programme

- George III papers, including references to madhouses and insanity from the Historic Psychiatry Collection, Menninger Archives, Kansas Historical Society

- Newspaper clippings about George III in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- "Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade – Estimates". slavevoyages.org.

.svg.png.webp)