Leopold I of Belgium

Leopold I (French: Léopold; 16 December 1790 – 10 December 1865) was the first king of the Belgians, reigning from 21 July 1831 until his death in 1865.

| Leopold I | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait by Nicaise de Keyser, 1856 | |||||

| King of the Belgians | |||||

| Reign | 21 July 1831 – 10 December 1865 | ||||

| Predecessor | Erasme Louis Surlet de Chokier (as Regent of Belgium) | ||||

| Successor | Leopold II | ||||

| Prime Ministers | See list

| ||||

| Born | 16 December 1790 Ehrenburg Palace, Coburg, Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, Holy Roman Empire (modern-day Germany) | ||||

| Died | 10 December 1865 (aged 74) Castle of Laeken, Brussels, Belgium | ||||

| Burial | Church of Our Lady of Laeken | ||||

| Spouse | Charlotte of Wales

(m. 1816; died 1817)Louise of Orléans

(m. 1832; died 1850) | ||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| House |

| ||||

| Father | Francis, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld | ||||

| Mother | Countess Augusta Reuss of Ebersdorf | ||||

| Religion | Lutheran | ||||

| Signature | .PNG.webp) | ||||

The youngest son of Francis, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, Leopold took a commission in the Imperial Russian Army and fought against Napoleon after French troops overran Saxe-Coburg during the Napoleonic Wars. After Napoleon's defeat, Leopold moved to the United Kingdom where he married Princess Charlotte of Wales, who was second in line to the British throne and the only legitimate child of the Prince Regent (the future King George IV). Charlotte died after only a year of marriage, but Leopold continued to enjoy considerable status in Britain.

After the Greek War of Independence (1821–1830), Leopold was offered the throne of Greece under the 1830 London Protocol that created an independent Greek state, but turned it down, believing it to be too precarious. Instead, he accepted the throne of Belgium in 1831 following the country's independence in 1830. The Belgian government offered the position to Leopold because of his diplomatic connections with royal houses across Europe, and because as the British-backed candidate, he was not affiliated with other powers, such as France, which were believed to have territorial ambitions in Belgium which might threaten the European balance of power created by the 1815 Congress of Vienna.

Leopold took his oath as King of the Belgians on 21 July 1831, an event commemorated annually as Belgian National Day. His reign was marked by attempts by the Dutch to recapture Belgium and, later, by internal political division between liberals and Catholics. As a Protestant, Leopold was considered liberal and encouraged economic modernisation, playing an important role in encouraging the creation of Belgium's first railway in 1835 and subsequent industrialisation. As a result of the ambiguities in the Belgian Constitution, Leopold was able to slightly expand the monarch's powers during his reign. He also played an important role in stopping the spread of the Revolutions of 1848 into Belgium. He died in 1865 and was succeeded by his son, Leopold II.

Early life

Leopold was born in Coburg in the tiny German duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld in modern-day Bavaria on 16 December 1790.[1] He was the youngest son of Francis, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, and Countess Augusta of Reuss-Ebersdorf. In 1826, Saxe-Coburg acquired the city of Gotha from the neighboring Duchy of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg and gave up Saalfeld to Saxe-Meiningen, becoming Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.

Military career

In 1797, at just six years old, Leopold was given an honorary commission of the rank of colonel in the Izmaylovsky Regiment, part of the Imperial Guard, in the Imperial Russian Army.[1] Six years later, he received a promotion to the rank of Major General.[1]

When French troops occupied the Duchy of Saxe-Coburg in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars, Leopold went to Paris where he became part of the Imperial Court of Napoleon.[1] Napoleon offered him the position of adjutant, but Leopold refused. Instead, he went to Russia to take up a military career in the Imperial Russian cavalry, which was at war with France at the time.[1] He campaigned against Napoleon and distinguished himself at the Battle of Kulm at the head of his cuirassier division. By 1815, the time of the final defeat of Napoleon, he had reached the rank of lieutenant general at only 25 years of age.

Marriage to Charlotte

Leopold received British citizenship in March 1816.[2] On 2 May 1816, Leopold married Princess Charlotte of Wales at Carlton House in London. Charlotte was the only legitimate child of the Regent George (later George IV) and therefore second in line to the British throne. The Prince Regent had hoped Charlotte would marry William, Prince of Orange, but she favoured Leopold. Although the Regent was displeased, he found Leopold to be charming and possessing every quality to make his daughter happy, and so approved their marriage. The same year Leopold received an honorary commission to the rank of Field Marshal and Knight of the Order of the Garter.[1] The Regent also considered making Leopold a royal duke, the Duke of Kendal, though the plan was abandoned due to government fears that it would draw Leopold into party politics and would be viewed as a demotion for Charlotte.[2] The couple lived initially at Camelford House on Park Lane,[3] and then at Marlborough House on Pall Mall.[4]

On 5 November 1817, after having suffered a miscarriage, Princess Charlotte gave birth to a stillborn son. She herself died the next day following complications. Leopold was said to have been heartbroken by her death.[5]

Had Charlotte survived, she would have become queen of the United Kingdom on the death of her father and Leopold presumably would have assumed the role of prince consort, later taken by his nephew Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Despite Charlotte's death, the Prince Regent granted Prince Leopold the British style of Royal Highness by Order in Council on 6 April 1818.[6]

From 1828 to 1829, Leopold had an affair with the actress Caroline Bauer, who bore a striking resemblance to Charlotte. Caroline was a cousin of his advisor Baron Christian Friedrich von Stockmar. She came to England with her mother and took up residence at Longwood House, a few miles from Claremont House. But, by mid-1829, the liaison was over, and the actress and her mother returned to Berlin. Many years later, in memoirs published after her death, she declared that she and Leopold had engaged in a morganatic marriage and that he had bestowed upon her the title of Countess Montgomery. He would have broken this marriage when the possibility arose that he could become King of Greece.[7] The son of Baron Stockmar denied that these events ever happened, and indeed no records have been found of a civil or religious marriage with the actress.[8]

Refusal of the Greek throne

Following a Greek rebellion against the Ottoman Empire, Leopold was offered the throne of an independent Greece as part of the London Protocol of February 1830. Though initially showing interest in the position, Leopold eventually turned down the offer on 17 May 1830. The role would subsequently be accepted by Otto of Wittelsbach in May 1832 who ruled until he was finally deposed in October 1862.

Acceptance of the Belgian throne

At the end of August 1830, rebels in the Southern provinces (modern-day Belgium) of the United Netherlands rose up against Dutch rule. The rising, which began in Brussels, pushed the Dutch army back, and the rebels defended themselves against a Dutch attack. International powers meeting in London agreed to support the independence of Belgium, even though the Dutch refused to recognize the new state.

In November 1830, a National Congress was established in Belgium to create a constitution for the new state. Fears of "mob rule" associated with republicanism after the French Revolution of 1789, as well as the example of the recent, liberal July Revolution in France, led the Congress to decide that Belgium would be a popular, constitutional monarchy.

Search for a monarch

The choice of candidates for the position was one of the most controversial issues faced by the revolutionaries.[9] The Congress refused to consider any candidate from the Dutch ruling house of Orange-Nassau.[9] Some Orangists had hoped to offer the position to William I or his son, William, Prince of Orange, which would bring Belgium into personal union with the Netherlands like Luxembourg.[9] The Great Powers also worried that a candidate from another state could risk destabilizing the international balance of power and lobbied for a neutral candidate.[9]

Eventually the Congress was able to draw up a shortlist. The three viable possibilities were felt to be Eugène de Beauharnais, a French nobleman and stepson of Napoleon; Auguste of Leuchtenberg, son of Eugène; and Louis, Duke of Nemours, who was the son of the French King Louis-Philippe.[10] All the candidates were French and the choice between them was principally between choosing the Bonapartism of Beauharnais or Leuchtenberg and supporting the July Monarchy of Louis-Philippe.[10] Louis-Philippe realized that the choice of either of the Bonapartists could be first stage of a coup against him, but that his son would also be unacceptable to other European powers suspicious of French intentions.[11] Nemours refused the offer.[11] With no definitive choice in sight, Catholics and Liberals united to elect Erasme Louis Surlet de Chokier, a minor Belgian nobleman, as regent to buy more time for a definitive decision in February 1831.[12]

Leopold of Saxe-Coburg had been proposed at an early stage, but had been dropped because of French opposition.[10] The problems caused by the French candidates and the increased international pressure for a solution led to his reconsideration. On 22 April, he was finally approached by a Belgian delegation at Marlborough House to officially offer him the throne.[13] Leopold, however, was reluctant to accept.[14]

Accession

On 17 July 1831, Leopold travelled from Calais to Belgium, entering the country at De Panne.[15] Travelling to Brussels, he was greeted with patriotic enthusiasm along his route.[15] The accession ceremony took place on 21 July on the Place Royale/Koningsplein in Brussels. A stand had been erected on the steps of the Church of St. James on Coudenberg, surrounded by the names of revolutionaries fallen during the fighting in 1830.[16] After a ceremony of resignation by the regent, Leopold, dressed in the uniform of a Belgian lieutenant-general, swore loyalty to the constitution and became king.[16]

The enthronement is generally used to mark the end of the revolution and the start of the Kingdom of Belgium and is celebrated each year as the Belgian national holiday.

Reign

Consolidation of independence

Less than two weeks after Leopold's accession, on 2 August, the Netherlands invaded Belgium, starting the Ten Days' Campaign. The small Belgian army was overwhelmed by the Dutch assault and was pushed back. Faced with a military crisis, Leopold appealed to the French for support. The French promised support, and the arrival of their Armée du Nord in Belgium forced the Dutch to accept a diplomatic mediation and retreat back to the pre-war border. Skirmishes continued for eight years, but in April 1839, the two countries signed the Treaty of London, whereby the Dutch recognised Belgium's independence.

Leopold was generally unsatisfied with the amount of power allocated to the monarch in the Constitution, and sought to extend it wherever the Constitution was ambiguous or unclear while generally avoiding involvement in routine politics.[17]

Subsequent reign

Leopold I's reign was also marked by an economic crisis which lasted until the late 1850s.[18] In the aftermath of the revolution, the Dutch had closed the Scheldt to Belgian shipping, meaning that the port of Antwerp was effectively useless. The Netherlands and the Dutch colonies in particular, which had been profitable markets for Belgian manufacturers before 1830, were totally closed to Belgian goods.[18] The period between 1845 and 1849 was particularly hard in Flanders, where harvests failed and a third of the population became dependent on poor relief, and have been described as the "worst years of Flemish history".[18] The economic situation in Flanders also increased the internal migration to Brussels and the industrial areas of Wallonia, which continued throughout the period.[18]

Politics in Belgium under Leopold I were polarized between liberal and Catholic political factions, though before 1847 they collaborated in "Unionist" governments.[17] The liberals were opposed to the Church's influence in politics and society, while supporting free trade, personal liberties and secularization.[19] The Catholics wanted religious teachings to be a fundamental basis for the state and society and opposed all attempts by the liberals to attack the Church's official privileges.[19] Initially, these factions existed only as informal groups with which prominent politicians were generally identified. The liberals held power through much of Leopold I's reign. An official Liberal Party was formed in 1846, although a formal Catholic Party was only established in 1869. Leopold, who was himself a Protestant, tended to favor liberals and shared their desire for reform, even though he was not partisan.[17] On his own initiative, in 1842, Leopold proposed a law which would have stopped women and children from working in some industries, but the bill was defeated.[1] Leopold was an early supporter of railways, and Belgium's first stretch of railway, between northern Brussels and Mechelen, was completed in 1835. When completed, it was one of the first passenger railways in continental Europe.[20]

Revolution of 1848

_(14740791186).jpg.webp)

The success of economic reforms partially mitigated the effects of the economic downturn and meant that Belgium was not as badly affected as its neighbors by the Revolutions of 1848.[21] Nevertheless, in early 1848, a large number of radical publications appeared.[21] The most serious threat of the 1848 revolutions in Belgium was posed by Belgian émigré groups. Shortly after the revolution in France, Belgian migrant workers living in Paris were encouraged to return to Belgium to overthrow the monarchy and establish a republic.[21] Around 6,000 armed émigrés of the "Belgian Legion" attempted to cross the Belgian frontier. The first group, travelling by train, was stopped and quickly disarmed at Quiévrain on 26 March 1848.[19] The second group crossed the border on 29 March and headed for Brussels.[21] They were confronted by Belgian troops at the hamlet of Risquons-Tout and, during fighting, seven émigrés were killed and most of the rest were captured.[21] To defuse tension, Leopold theatrically offered his abdication, if this was the wish of the majority of his people.

The defeat at Risquons-Tout effectively ended the revolutionary threat to Belgium, as the situation in Belgium began to recover that summer after a good harvest, and fresh elections returned a strong Liberal majority.[21]

Role in international relations

Because of his family connections and position at the head of a neutral and unthreatening power, Leopold was able to act as an important intermediary in European politics during his reign. As a result of this, he earned the nickname the "Nestor of Europe", after the wise mediator in Homer's Iliad. Leopold played a particularly important role in moderating relations between the hostile Great Powers. In the later part of his reign, his role in managing relations between the United Kingdom and the French Empire of Napoleon III was particularly important.

Leopold was particularly known as a political marriage broker.[22] In 1835–1836, he promoted the marriage between his nephew Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and the Queen of Portugal, Maria II. He promoted the marriage of his niece, Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom, to his nephew, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Even before she succeeded to the throne, Leopold had been advising Victoria by letter, and continued to influence her after her accession.

In foreign policy, Leopold's principal object was the maintenance of Belgian neutrality. Despite pressure from the Great Powers, especially over the Crimean War (1853–56), Belgium remained neutral throughout the reigns of Leopold I and II.

Second marriage and family

Leopold married Louise-Marie of Orléans (daughter of Louis Philippe I) on 9 August 1832. They had four children:

- Louis Philippe, Crown Prince of Belgium (24 July 1833 – 16 May 1834) who died in infancy.

- Leopold, Duke of Brabant (9 April 1835 – 17 December 1909), the future King Leopold II. He married Archduchess Marie Henriette of Austria on 22 August 1853. They had three daughters and one son who died young. He religiously but not civilly remarried Caroline Lacroix, which made the marriage unrecognized by law, on 12 December 1909 on his deathbed. They already had two illegitimate sons.

- Prince Philippe, Count of Flanders (24 March 1837 – 17 November 1905) who married Princess Marie of Hohenzollern on 25 April 1867. They had five children, including king Albert I of Belgium

- Princess Charlotte of Belgium (7 June 1840 – 19 January 1927). She married Maximilian I of Mexico on 27 July 1857 and became Empress of Mexico. They had no issue. She adopted two sons, the grandsons of the first Emperor of Mexico.

Queen Louise-Marie died of tuberculosis on 11 October 1850, aged 38.[1]

Other descendants

Leopold also had two sons, George and Arthur, by his mistress Arcadie Meyer (née Claret).[23][24] George von Eppinghoven was born in 1849, and Arthur von Eppinghoven in 1852. At Leopold's request,[24] in 1862 his two sons were created Freiherr von Eppinghoven by his nephew, Ernest II, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha; in 1863 Arcadie was also created Baronin von Eppinghoven.[25]

Death and succession

Leopold died in Laeken near Brussels on 10 December 1865, a week short of his 75th birthday.[26] His funeral was held on 16 December, on what would have been his 75th birthday. He is interred in the Royal Crypt at the Church of Our Lady of Laeken, next to Louise-Marie.

Leopold was succeeded by his son, Leopold II, aged 30, who would rule until 1909.

Commemoration

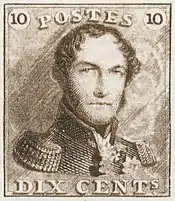

Belgian naval vessels named in his honour include the Leopold I, a frigate acquired by Belgium in 2007. His monogram features on the flag of the Flemish town of Leopoldsburg. His likeness has also appeared on postage stamps and commemorative coins issued since his death.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Leopold I of Belgium[22] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

References

- Monarchie website.

- The Lost Queen: The Life and Tragedy of the Prince Regent's Daughter. Pen and Sword History. 30 March 2020. ISBN 9781526736444.

- Sheppard, F. H. W. "Park Lane Pages 264-289 Survey of London: Volume 40, the Grosvenor Estate in Mayfair, Part 2 (The Buildings). Originally published by London County Council, London, 1980". British History Online. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- Walford, Edward. "Pall Mall Pages 123-139 Old and New London: Volume 4. Originally published by Cassell, Petter & Galpin, London, 1878". British History Online. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- Holme, Thea (1976), Prinny's Daughter, p.241 London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 978-0-241-89298-5. OCLC 2357829.

- "Royal Styles and Titles of Great Britain: Documents". www.heraldica.org.

- K. BAUER, Aus meinem Bühnenleben. Erinnerungen von Karoline Bauer, Berlin, 1876–1877.

- E. VON STOCKMAR, Denkwürdigkeiten aus den Papiere des Freihernn Christian Friedrich von Stockmar, Brunswick, 1873 ; R. VON WANGENHEIM, Baron Stockmar. Eine coburgisch-englische Geschichte, Coburg, 1996.

- Pirenne 1948, p. 11.

- Pirenne 1948, p. 12.

- Pirenne 1948, p. 14.

- Pirenne 1948, p. 20.

- Pirenne 1948, p. 26.

- Pirenne 1948, pp. 26–7.

- Pirenne 1948, p. 29.

- Pirenne 1948, p. 30.

- Chastain 1999.

- Carson 1974, p. 225.

- Ascherson 1999, pp. 20–1.

- Wolmar 2010, p. 19.

- Chastain 1997.

- Béeche. Arturo E. The Coburgs of Europe. Eurohistory. 2013. pp. ii, 4, 46, 354–355. ISBN 978-0-9854603-3-4

- Goddyn, Reinout (2002). De kinderen van de koning: Alle erfgenamen van Leopold I (in Dutch). House of Books. p. 96.

- Capron, Victor (2006). Sur les traces d'Arcadie Claret: le Grand Amour de Léopold Ier (in French). Brussels.

- Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels [Genealogical Handbook of the Nobility]. Freiherrlichen Häuser (in German). Vol. Band XXI. C. A. Starke. 1999. pp. 101–3.

- "Belgium – Last moments of King Leopold". The New York Times. 28 December 1865. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

Bibliography

- Ascherson, Neal (1999). The King Incorporated: Leopold the Second and the Congo (New ed.). London: Granta. ISBN 1862072906.

- Carson, Patricia (1974). The Fair Face of Flanders (Rev. ed.). Ghent: E.Story-Scientia. OCLC 463182600.

- Chastain, James. "Leopold I". Encyclopedia of 1848. Ohio University.

- Chastain, James. "Belgium in 1848". Encyclopedia of 1848 Revolutions. Ohio University. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- "Léopold Ier". La Monarchie Belge. Monarchie.be. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- Pirenne, Henri (1948). Histoire de Belgique (in French). Vol. VII: De la Révolution de 1830 à la Guerre de 1914 (2nd ed.). Brussels: Maurice Lamertin.

- Wolmar, Christian (2010). Blood, Iron & Gold: How the Railways transformed the World. London: Grove Atlantic. ISBN 9781848871717.

- Polasky, Janet L. (2004). "Leopold I (1790-1865)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/41227. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

External links

Media related to Leopold I of Belgium at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Leopold I of Belgium at Wikimedia Commons- Leopold I: Un Roi Protestant at the Chapelle royale