Linux distribution

A Linux distribution[lower-alpha 1] (often abbreviated as distro) is an operating system made from a software collection that includes the Linux kernel and, often, a package management system. Linux users usually obtain their operating system by downloading one of the Linux distributions, which are available for a wide variety of systems ranging from embedded devices (for example, OpenWrt) and personal computers (for example, Linux Mint) to powerful supercomputers (for example, Rocks Cluster Distribution).

A typical Linux distribution comprises a Linux kernel, GNU tools and libraries, additional software, documentation, a window system (the most common being the X Window System, or, more recently, Wayland), a window manager, and a desktop environment.

Most of the included software is free and open-source software made available both as compiled binaries and in source code form, allowing modifications to the original software. Usually, Linux distributions optionally include some proprietary software that may not be available in source code form, such as binary blobs required for some device drivers.[1]

A Linux distribution may also be described as a particular assortment of application and utility software (various GNU tools and libraries, for example), packaged with the Linux kernel in such a way that its capabilities meet many users' needs.[2] The software is usually adapted to the distribution and then combined into software packages by the distribution's maintainers. The software packages are available online in repositories, which are storage locations usually distributed around the world.[3][4] Beside "glue" components, such as the distribution installers (for example, Debian-Installer and Anaconda) and the package management systems, very few packages are actually written by a distribution's maintainers.

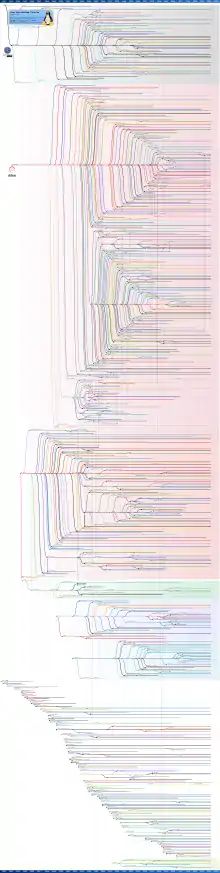

Almost one thousand Linux distributions exist.[5][6] Because of the huge availability of software, distributions have taken a wide variety of forms, including those suitable for use on desktops, servers, laptops, netbooks, mobile phones and tablets,[7][8] as well as in minimal environments typically for use in embedded systems.[9][10] There are commercially backed distributions, such as Fedora Linux (Red Hat), openSUSE (SUSE) and Ubuntu (Canonical Ltd.); and entirely community-driven distributions, such as Debian, Slackware, Gentoo and Arch Linux. Most distributions come ready-to-use and precompiled for a specific instruction set, while some (such as Gentoo) are distributed mostly in source code form and must be compiled locally for installation.[11]

History

Linus Torvalds developed the Linux kernel and distributed its first version, 0.01, in 1991. Linux was initially distributed as source code only, and later as a pair of downloadable floppy disk images: one bootable and containing the Linux kernel itself, and the other with a set of GNU utilities and tools for setting up a file system. Since the installation procedure was complicated, especially in the face of growing amounts of available software, distributions sprang up to simplify it.[13]

Early distributions included:

- H. J. Lu's "Boot-root", the aforementioned disk image pair with the kernel and the absolute minimal tools to get started (late 1991)[14]

- MCC Interim Linux (February 1992)

- Softlanding Linux System (SLS) which included the X Window System and was the most comprehensive distribution for a short time (1992)

- Yggdrasil Linux/GNU/X, a commercial distribution (December 1992)

The two oldest, still active distribution projects started in 1993. The SLS distribution was not well maintained, so in July 1993 a new SLS-based distribution, Slackware, was released by Patrick Volkerding.[15] Also dissatisfied with SLS, Ian Murdock set to create a free distribution by founding Debian, first released in December 1993.[16]

Users were attracted to Linux distributions as alternatives to the DOS and Microsoft Windows operating systems on IBM PC compatible computers, Mac OS on the Apple Macintosh, and proprietary versions of Unix. Most early adopters were familiar with Unix from work or school. They embraced Linux distributions for their low (or absent) cost, and the availability of the source code for most or all of their software.

As of 2017, Linux has become more popular in server and embedded-devices markets than the desktop market. It is used on over 50% of web servers;[17] its current desktop market share is about 3.7%.[18]

Components

Many Linux distributions provide an installation system akin to that provided with other modern operating systems. Other distributions, including Gentoo Linux, provide only the binaries of a basic kernel, compilation tools, and an installer; the installer compiles all the requested software for the specific architecture of the user's computer, using these tools and the software's source code.

Package management

Distributions are normally segmented into packages. Each package contains a specific application or service. Examples of packages are a library for handling the PNG image format, a collection of fonts, and a web browser.

The package is typically provided as compiled code, with installation and removal of packages handled by a package management system (PMS) rather than a simple file archiver. Each package intended for such a PMS contains meta-information such as its description, version number, and its dependencies (other packages it requires to run). The package management system evaluates this meta-information to allow package searches, perform automatic upgrades to newer versions, and to check that all dependencies of a package are present (and either notify the user to install them, or install them automatically).

Although Linux distributions typically contain much more software than proprietary operating systems, it is normal for local administrators to also install software not included in the distribution. An example would be a newer version of a software application than that supplied with the distribution, or an alternative to that chosen by the distribution (for example, KDE Plasma Workspaces rather than GNOME, or vice versa, for the user interface layer). If the additional software is distributed in source-only form, it must be locally compiled. However, if additional software is locally added, the "state" of the local system may fall out of synchronization with the state of the package manager's database. If so, the local administrator must take additional measures to ensure the entire system is kept up-to-date, as the package manager may no longer be able to do so automatically.

Most distributions install packages, including the kernel and other core operating system components, in a predetermined configuration. A few now require or permit configuration adjustments at first install time. This makes installation less daunting, particularly for new users, but is not always acceptable. For specific requirements, much software must be carefully configured to be useful, to work correctly with other software, or to be secure, and local administrators are often obliged to spend time reviewing and reconfiguring it.

Some (but not all) distributions go to considerable lengths to adjust and customize the software they include, and some provide configuration tools to help users do so.

By obtaining and installing everything normally provided in a distribution, an administrator may create a "distributionless" installation. It is possible to build such systems from scratch, avoiding distributions altogether. One needs a way to generate the first binaries until the system is self-hosting. This can be done via compilation on another system capable of building binaries for the intended target (possibly by cross-compilation). For example, see Linux From Scratch.

Types and trends

In broad terms, Linux distributions may be:

- Commercial or non-commercial

- Designed for enterprise users, power users, or for home users

- Supported on multiple types of hardware, or platform-specific, even to the extent of certification by the platform vendor

- Designed for servers, desktops, or embedded devices

- General purpose or highly specialized toward specific machine functionalities (e.g. firewalls, network routers, and computer clusters)

- Targeted at specific user groups, for example through language internationalization and localization, or through inclusion of many music production or scientific computing packages

- Built primarily for security, usability, portability, or comprehensiveness

- Standard release or rolling release, see below.

The diversity of Linux distributions is due to technical, organizational, and philosophical variation among vendors and users. The permissive licensing of free software means that users with sufficient knowledge and interest can customize any existing distribution, or design one to suit their own needs.

Rolling distributions

Rolling Linux distributions are kept current using small and frequent updates. The terms partially rolling and partly rolling (along with synonyms semi-rolling and half-rolling), fully rolling, truly rolling and optionally rolling are sometimes used by software developers and users.[19][20][21][22][23][24]

Repositories of rolling distributions usually contain very recent software releases—often the latest stable versions available. They have pseudo-releases and installation media that are simply snapshots of the distribution at the time of the installation image's release. Typically, a rolling-release OS installed from older installation medium can be fully updated after it is installed.

Depending on the usage case, there can be pros and cons to both standard release and rolling release software development methodologies.[25]

In terms of the software development process, standard releases require significant development effort to keep old versions up-to-date by propagating bug fixes back to the newest branch, versus focusing on the newest development branch. Also, unlike rolling releases, standard releases require more than one code branch to be developed and maintained, which increasing the workloads of the software developers and maintainers.

On the other hand, software features and technology planning are easier in standard releases due to a better understanding of upcoming features in the next version(s). Software release cycles can also be synchronized with those of major upstream software projects, such as desktop environments.

As far as the user experience, standard releases are often viewed as more stable and bug-free since software conflicts can be more easily addressed and the software stack more thoroughly tested and evaluated, during the software development cycle.[25][26] For this reason, they tend to be the preferred choice in enterprise environments and mission-critical tasks.[25]

However, rolling releases offer more current software which can also provide increased stability and fewer software bugs along with the additional benefits of new features, greater functionality, faster running speeds, and improved system and application security. Regarding software security, the rolling release model can have advantages in timely security updates, fixing system or application security bugs and vulnerabilities, that standard releases may have to wait till the next release for or patch in various versions. In a rolling release distribution, where the user has chosen to run it as a highly dynamic system, the constant flux of software packages can introduce new unintended vulnerabilities.[25]

Installation-free distributions (live CD/USB)

A "live" distribution is a Linux distribution that can be booted from removable storage media such as optical discs or USB flash drives, instead of being installed on and booted from a hard disk drive. The portability of installation-free distributions makes them advantageous for applications such as demonstrations, borrowing someone else's computer, rescue operations, or as installation media for a standard distribution.

When the operating system is booted from a read-only medium such as a CD or DVD, any user data that needs to be retained between sessions cannot be stored on the boot device but must be written to another storage device, such as a USB flash drive or a hard disk drive.[27]

Many Linux distributions provide a "live" form in addition to their conventional form, which is a network-based or removable-media image intended to be used only for installation; such distributions include SUSE, Ubuntu, Linux Mint, MEPIS and Fedora Linux. Some distributions, including Knoppix, Puppy Linux, Devil-Linux, SuperGamer, SliTaz GNU/Linux and dyne:bolic, are designed primarily for live use. Additionally, some minimal distributions can be run directly from as little space as one floppy disk without the need to change the contents of the system's hard disk drive.[28]

Examples

The website DistroWatch lists many Linux distributions, and displays some of the ones that have the most web traffic on the site. The Wikimedia Foundation released an analysis of the browser User Agents of visitors to WMF websites until 2015, which includes details of the most popular Operating System identifiers, including some Linux distributions.[29] Many of the popular distributions are listed below.

Widely used GNU-based or GNU-compatible distributions

- Debian, a non-commercial distribution and one of the earliest, maintained by a volunteer developer community with a strong commitment to free software principles and democratic project management.

- Ubuntu, a desktop and server distribution derived from Debian, maintained by British company Canonical Ltd.

- There are several distributions based on Ubuntu that mainly replace the GNOME stock desktop environment, like: Kubuntu based on KDE, Lubuntu based on LXQT, Xubuntu based on XFCE, Ubuntu MATE based on MATE, Ubuntu Budgie based on Budgie. Other official forks have specific uses like: Ubuntu Kylin for Chinese-speaking users, or Ubuntu Studio for media content creators.

- Linux Mint, a distribution based on and compatible with Ubuntu. Supports multiple desktop environments, among others GNOME Shell fork Cinnamon and GNOME 2 fork MATE.

- Ubuntu, a desktop and server distribution derived from Debian, maintained by British company Canonical Ltd.

- Fedora Linux, a community distribution sponsored by American company Red Hat and the successor to the company's previous offering, Red Hat Linux. It aims to be a technology testbed for Red Hat's commercial Linux offering, where new open-source software is prototyped, developed, and tested in a communal setting before maturing into Red Hat Enterprise Linux.

- Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL), a derivative of Fedora Linux, maintained and commercially supported by Red Hat. It seeks to provide tested, secure, and stable Linux server and workstation support to businesses.

- openSUSE, a community distribution mainly sponsored by German company SUSE.

- SUSE Linux Enterprise, derived from openSUSE, maintained and commercially supported by SUSE

- Arch Linux, a rolling release distribution targeted at experienced Linux users and maintained by a volunteer community, offers official binary packages and a wide range of unofficial user-submitted source packages. Packages are usually defined by a single PKGBUILD text file.

- Manjaro Linux, a derivative of Arch Linux that includes a graphical installer and other ease-of-use features for less experienced Linux users.

- Gentoo, a distribution targeted at power users, known for its FreeBSD Ports-like automated system for compiling applications from source code

Linux kernel based operating systems

- Android, Google's commercial operating system based on Android OSP that runs on many devices such as smart phones, smart TVs, set-top boxes.

- Chrome OS, Google's commercial operating system based on Chromium OS that only runs on Chromebooks, Chromeboxes and tablet computers. Like Android, it has the Google Play Store and other Google apps. Support for applications that require GNU compatibility is available through a virtual machine called Crostini and referred to by Google as Linux support, see Chromebook § Integration with Linux.

Whether the above operating systems count as a "Linux distribution" is a controversial topic. They use the Linux kernel, so the Linux Foundation[30] and Chris DiBona,[31] Google's open-source chief, agree that Android is a Linux distribution; others, such as Google engineer Patrick Brady, disagree by noting the lack of support for many GNU tools in Android, including glibc.[32]

Other Linux kernel based operating systems include Cyanogenmod, its fork LineageOS, Android-x86 and recently Tizen, Mer/Sailfish OS and KaiOS.

Lightweight distributions

Lightweight Linux distributions are those that have been designed with support for older hardware in mind, allowing older hardware to still be used productively, or, for maximum possible speed in newer hardware by leaving more resources available for use by applications. Examples include Tiny Core Linux, Puppy Linux and Slitaz.

Niche distributions

Other distributions target specific niches, such as:

- Routers – for example, targeted by the tiny embedded router distribution OpenWrt

- Internet of things – for example, targeted by Ubuntu Core[33]

- Home theater PCs – for example, targeted by KnoppMyth, Kodi (former XBMC) and Mythbuntu

- Specific platforms – for example, Raspberry Pi OS targets the Raspberry Pi platform

- Education – examples are Edubuntu and Karoshi, server systems based on PCLinuxOS

- Scientific computer servers and workstations – for example, targeted by Scientific Linux

- Digital audio workstations for music production – for example, targeted by Ubuntu Studio

- Computer Security, digital forensics and penetration testing – examples are Kali Linux and Parrot Security OS

- Privacy and anonymity – for example, targeted by Tails, Whonix, Qubes, or FreedomBox

- Offline use – for example, Endless OS

- Microsoft's Azure Sphere

Interdistribution issues

The Free Standards Group is an organization formed by major software and hardware vendors that aims to improve interoperability between different distributions. Among their proposed standards are the Linux Standard Base, which defines a common ABI and packaging system for Linux, and the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard which recommends a standard filenaming chart, notably the basic directory names found on the root of the tree of any Linux filesystem. Those standards, however, see limited use, even among the distributions developed by members of the organization.

The diversity of Linux distributions means that not all software runs on all distributions, depending on what libraries and other system attributes are required. Packaged software and software repositories are usually specific to a particular distribution, though cross-installation is sometimes possible on closely related distributions.

Tools for choosing a distribution

The process of constantly switching between distributions is often referred to as "distro hopping".[34] Virtual machines such as VirtualBox and VMware Workstation virtualize hardware allowing users to test live media on a virtual machine. Some websites like DistroWatch offer lists of distributions, and link to screenshots of operating systems as a way to get a first impression of various distributions.

There are tools available to help people select an appropriate distribution, such as several versions of the Linux Distribution Chooser,[35] and the universal package search tool whohas.[36] There are easy ways to try out several Linux distributions before deciding on one: Multi Distro is a Live CD that contains nine space-saving distributions.[37] Tools like Ventoy allow booting from one of several live distributions copied to a storage device by selecting the appropriate disk image from a boot menu.[38]

Installation

There are several ways to install a Linux distribution. The most common method of installing Linux is by booting from a live USB memory stick, which can be created by using a USB image writer application and the ISO image, which can be downloaded from the various Linux distribution websites. DVD disks, CD disks, network installations and even other hard drives can also be used as "installation media".[39]

In the 1990s Linux distributions were installed using sets of floppies but this has been abandoned by all major distributions. By the 2000s many distributions offered CD and DVD sets with the vital packages on the first disc and less important packages on later ones. Some distributions, such as Debian also enabled installation over a network after booting from either a set of floppies or a CD with only a small amount of data on it.[40]

New users tend to begin by partitioning a hard drive in order to keep their previously installed operating system. The Linux distribution can then be installed on its own separate partition without affecting previously saved data.[41]

In a Live CD setup, the computer boots the entire operating system from CD without first installing it on the computer's hard disk. Many distributions have a Live CD installer, where the computer boots the operating system from the disk, and it can then be installed on the computer's hard disk, providing a seamless transition from the OS running from the CD to the OS running from the hard disk.

Both servers and personal computers that come with Linux already installed are available from vendors including Hewlett-Packard, Dell and System76.

On embedded devices, Linux is typically held in the device's firmware and may or may not be consumer-accessible.

Anaconda, one of the more popular installers, is used by Red Hat Enterprise Linux, Fedora (which uses the Fedora Media Writer) and other distributions to simplify the installation process. Debian, Ubuntu and many others use Debian-Installer.

Installation via an existing operating system

Some distributions let the user install Linux on top of their current system, such as WinLinux or coLinux. Linux is installed to the Windows hard disk partition, and can be started from inside Windows itself.

Virtual machines (such as VirtualBox or VMware) also make it possible for Linux to be run inside another OS. The VM software simulates a separate computer onto which the Linux system is installed. After installation, the virtual machine can be booted as if it were an independent computer.

Various tools are also available to perform full dual-boot installations from existing platforms without a CD, most notably:

- The (now deprecated) Wubi installer, which allows Windows users to download and install Ubuntu or its derivatives into a FAT32 or an NTFS partition without an installation CD, allowing users to easily dual boot between either operating system on the same hard drive without losing data. Replaced by Ubiquity.

- Win32-loader, which is in the process of being integrated in official Debian CDs/DVDs, and allows Windows users to install Debian without a CD, though it performs a network installation and thereby requires repartitioning[42]

- UNetbootin, which allows Windows and Linux users to perform similar no-CD network installations for a wide variety of Linux distributions and additionally provides live USB creation support

Proprietary software

Some specific proprietary software products are not available in any form for Linux. As of September 2015, the Steam gaming service has 1,500 games available on Linux, compared to 2,323 games for Mac and 6,500 Windows games.[43][44][45] Emulation and API-translation projects like Wine and CrossOver make it possible to run non-Linux-based software on Linux systems, either by emulating a proprietary operating system or by translating proprietary API calls (e.g., calls to Microsoft's Win32 or DirectX APIs) into native Linux API calls. A virtual machine can also be used to run a proprietary OS (like Microsoft Windows) on top of Linux.

OEM contracts

Computer hardware is usually sold with an operating system other than Linux already installed by the original equipment manufacturer (OEM). In the case of IBM PC compatibles the OS is usually Microsoft Windows; in the case of Apple Macintosh computers it has always been a version of Apple's OS, currently macOS; Sun Microsystems sold SPARC hardware with the Solaris installed; video game consoles such as the Xbox, PlayStation, and Wii each have their own proprietary OS. This limits Linux's market share: consumers are unaware that an alternative exists, they must make a conscious effort to use a different operating system, and they must either perform the actual installation themselves, or depend on support from a friend, relative, or computer professional.

However, it is possible to buy hardware with Linux already installed. Lenovo, Hewlett-Packard, Dell, Affordy,[46] Purism, Pine64 and System76 all sell general-purpose Linux laptops.[47] Custom-order PC manufacturers will also build Linux systems, but possibly with the Windows key on the keyboard. Fixstars Solutions (formerly Terra Soft) sells Macintosh computers and PlayStation 3 consoles with Yellow Dog Linux installed.

It is more common to find embedded devices sold with Linux as the default manufacturer-supported OS, including the Linksys NSLU2 NAS device, TiVo's line of personal video recorders, and Linux-based cellphones (including Android smartphones), PDAs, and portable music players.

The current Microsoft Windows license lets the manufacturer determine the refund policy.[48] With previous versions of Windows, it was possible to obtain a refund if the manufacturer failed to provide the refund by litigation in the small claims courts.[49] On February 15, 1999, a group of Linux users in Orange County, California held a "Windows Refund Day" protest in an attempt to pressure Microsoft into issuing them refunds.[50] In France, the Linuxfrench and AFUL (French speaking Libre Software Users' Association) organizations along with free software activist Roberto Di Cosmo started a "Windows Detax" movement,[51] which led to a 2006 petition against "racketiciels" (translation: Racketware) with 39,415 signatories and the DGCCRF branch of the French government filing several complaints against bundled software. On March 24, 2014, a new international petition was launched by AFUL on the Avaaz platform,[52] translated into several languages and supported by many organizations around the world.

Statistics

There are no official figures on popularity, adoption, downloads or installed base of Linux distributions.

There are also no official figures for the total number of Linux systems,[53][54] partly due to the difficulty of quantifying the number of PCs running Linux (see Desktop Linux adoption), since many users download Linux distributions. Hence, the sales figures for Linux systems and commercial Linux distributions indicate a much lower number of Linux systems and level of Linux adoption than is the case; this is mainly due to Linux being free and open-source software that can be downloaded free of charge.[53][55] A Linux Counter Project had kept track of a running guesstimate of the number of Linux systems, but did not distinguish between rolling release and standard release distributions. It ceased operation in August 2018, though a few related blog posts were created through October 2018.[56]

Desktop usage statistical reports for particular Linux distributions have been collected and published since July 2014[57] by the Linux Hardware Project.

See also

- Comparison of Linux distributions

- Light-weight Linux distribution

- List of Linux distributions

Notes

- Sometimes called a GNU/Linux distribution, with some related controversy

References

- "Explaining Why We Don't Endorse Other Systems". gnu.org. June 30, 2014. Archived from the original on April 24, 2011. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- "Linux Operating Systems: Distributions". swift.siphos.be. November 27, 2014. Archived from the original on October 3, 2018. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- Chris Hoffman (June 27, 2012). "HTG Explains: How Software Installation & Package Managers Work On Linux". howtogeek.com. Archived from the original on February 10, 2015. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- "The status of CentOS mirrors". centos.org. January 15, 2015. Archived from the original on December 31, 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- "The LWN.net Linux Distribution List". LWN.net. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved September 11, 2015.

- "DistroWatch.com: Put the fun back into computing. Use Linux, BSD". distrowatch.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- Jim Martin. "How to install Ubuntu Touch on your Android phone or tablet". PC Advisor. Archived from the original on October 27, 2015. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- David Hayward. "Install Linux on your x86 tablet: five distros to choose from". TechRadar. Archived from the original on April 13, 2019. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- Brian Proffitt (February 3, 2010). "The Top 7 Best Linux Distributions for You". linux.com. Archived from the original on January 5, 2015. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- Eric Brown (November 4, 2014). "Mobile Linux Distros Keep on Morphing". linux.com. Archived from the original on February 13, 2015. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- "Debian and Other Distros". debian.org. December 7, 2013. Archived from the original on January 14, 2015. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- "Linux Distributions Timeline". FabioLolix. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- Berlich, Ruediger (April 2001). "ALL YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT... The early history of Linux, Part 2, Re: distribution" (PDF). LinuxUser. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 28, 2012. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- "A Short History of Linux Distributions [LWN.net]". lwn.net. Archived from the original on June 23, 2018. Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- "The Slackware Linux Project: Slackware Release Announcement". Slackware.com. July 16, 1993. Archived from the original on August 9, 2011. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- "A Brief History of Debian - Debian Releases". debian.org. May 4, 2013. Archived from the original on August 17, 2011. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- "Usage statistics and market share of Unix for websites". w3techs.org. November 5, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- "Browser & Platform Market Share January 2017". w3counter.com. January 31, 2017. Archived from the original on February 22, 2017. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- The Chakra Project. "half-rolling development model". chakra-project-org. Archived from the original on October 11, 2011. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- The Chakra Project. "The Chakra Project Wiki: FAQs". chakra-project-org. Archived from the original on August 27, 2011.

- "Fedora Release Life-cycle Proposals". fedoraproject.org. Archived from the original on May 18, 2019. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- "Fedora Development Mailing List". fedoraproject.org. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- Rev. "Linux Certification – Preparation". walkingwithzen.com. Archived from the original on September 14, 2011. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- "Why openSUSE". opensuse.org. Archived from the original on May 18, 2019. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- Chad Perrin (August 2, 2010), Point-release vs rolling-release: developer, user and security considerations, techrepublic.com, archived from the original on September 28, 2012, retrieved September 6, 2011

- K.Mandla (March 9, 2007). "The pros and cons of a rolling release". kmandla.wordpress.com. Archived from the original on November 12, 2010. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

- Jonathan Corbet (June 15, 2011). "Debating overlayfs". LWN.net. Archived from the original on July 24, 2015. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- "PiTuX – a micro serial terminal distro". asashi.net. Archived from the original on February 2, 2015. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- "Wikimedia Traffic Analysis Report - Operating Systems". stats.wikimedia.org. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- Ask AC: Is Android Linux?. "Ask AC: Is Android Linux?". Android Central. Archived from the original on April 8, 2017. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- derStandard.at. "Google: "Android is the Linux desktop dream come true" - Suchmaschinen - derStandard.at " Web". Derstandard.at. Archived from the original on April 22, 2013. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- Paul, Ryan (February 24, 2009). "Dream(sheep++): A developer's introduction to Google Android". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on July 4, 2017. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- Dieguez Castro, Jose (2016). Introducing Linux Distros. Apress. pp. 49, 345. ISBN 978-1-4842-1393-3.

- "How I stopped distro hopping". Linux Today. Archived from the original on September 19, 2016. Retrieved July 10, 2016.

- "Distro Selector". Desktop Linux At Home. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- "Philipp's Homepage: whohas". Philippwesche.org. February 11, 2010. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- "Multi Distro is Linux times 9 on a single CD-R". Linux.com. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- Langner, Christopher. "Tutorial - Ventoy". Linux Magazine. Linux New Media USA. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- "2.4. Installation Media". www.debian.org. Archived from the original on July 24, 2018. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- "Network install from a minimal CD". Debian. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- "WindowsDualBoot". ubuntu.com. June 29, 2015. Archived from the original on March 2, 2020. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- Debian Webmaster. "Debian - Details of package win32-loader in Lenny". Packages.debian.org. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- Jared Newman (September 21, 2015). "Steam for Linux tops 1,500 games as launch of Valve's Steam Machines nears". PCWorld. Archived from the original on November 19, 2015. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- "Steam's living room hardware blitz gets off to a muddy start". Ars Technica. October 15, 2015. Archived from the original on January 11, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

- "The state of Linux gaming in the SteamOS era". Ars Technica. February 26, 2015. Archived from the original on May 8, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

- "Affordy - TITAN Computers". Shop.affordy.com. Archived from the original on May 29, 2009. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- "Laptops/Notebooks with Linux Preinstalled". Mcelrath.org. June 10, 2010. Archived from the original on August 20, 2011. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- "Microsoft Software License Terms: Windows 7 Professional" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 11, 2012. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- "Getting a Windows Refund in California Small Claims Court". Linuxjournal.com. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- "Windows Refund Day". Marc.merlins.org. February 15, 1999. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- Detaxe.org Archived March 24, 2007, at the Wayback Machine (in French) Say no to bundled software - Say yes to informed consumers

- AM, Last modified: 04/29/2014 01:10. "International petition | AFUL". no.more.racketware.info. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- Prashanth Venkataram (September 10, 2010). "Counter-Debunking the 1% myth". dasublogbyprashanth.blogspot.com. Archived from the original on September 15, 2010. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- Schestowitz, Roy (July 2007). "Can Linux Adoption Ever be Accurately Gauged?". Archived from the original on February 7, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2008.

- Caitlyn Martin (September 7, 2010). "Debunking the 1% myth". oreilly.com. Archived from the original on February 27, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- C. Lohner. "The Linuxcounter project is closed!". Archived from the original on August 31, 2019. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

- A. Ponomarenko. "Linux Hardware Trends". Archived from the original on September 20, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

External links

- The LWN.net Linux Distribution List – a categorized list with information about each entry

- List of GNU/Linux distributions considered free by the Free Software Foundation

- Google's approach to a large-scale live upgrading between two widely different Linux distributions: presentation and text version, LinuxCon 2013, by Marc Merlin

- Rolling release vs. fixed release Linux, ZDNet, February 3, 2015, by Steven J. Vaughan-Nichols