Llywelyn ap Gruffudd

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (c. 1223 – 11 December 1282), sometimes written as Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, also known as Llywelyn the Last (Welsh: Llywelyn Ein Llyw Olaf, lit. 'Llywelyn, Our Last Leader'), was the native Prince of Wales (Latin: Princeps Walliae; Welsh: Tywysog Cymru) from 1258 until his death at Cilmeri in 1282. Llywelyn was the son of Gruffydd ap Llywelyn Fawr and grandson of Llywelyn the Great, and he was one of the last native and independent princes of Wales before its conquest by Edward I of England and English rule in Wales that followed, until Owain Glyndŵr held the title during the Welsh Revolt of 1400–1415.

| Llywelyn ap Gruffudd | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prince of Aberffraw Lord of Snowdon | |||||

Contemporary depiction | |||||

| Prince of Wales | |||||

| Reign | 1246–1282 | ||||

| Predecessor | Dafydd ap Llywelyn | ||||

| Successor | Dafydd ap Gruffydd | ||||

| Born | c. 1223 Gwynedd, Wales | ||||

| Died | 11 December 1282 Aberedw, Powys, Wales | ||||

| Spouse | Eleanor de Montfort | ||||

| Issue | Gwenllian of Wales Princess Catherine | ||||

| |||||

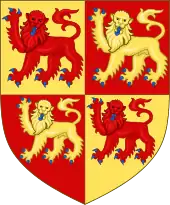

| Royal house | Aberffraw | ||||

| Father | Gruffydd ap Llywelyn Fawr | ||||

| Mother | Senana ferch Caradog | ||||

Genealogy and early life

Llywelyn was the second of the four sons of Gruffydd, the eldest son of Llywelyn the Great, and Senana ferch Caradog, the daughter of Caradoc ap Thomas ap Rhodri, Lord of Anglesey.[note 1][1] The eldest was Owain Goch ap Gruffydd and Llywelyn had two younger brothers, Dafydd ap Gruffydd and Rhodri ap Gruffydd. Llywelyn is thought to have been born around 1222 or 1223. He is first heard of holding lands in the Vale of Clwyd around 1244.

Following his grandfather's death in 1240, Llywelyn's uncle, Dafydd ap Llywelyn (who was Llywelyn the Great's eldest legitimate son), succeeded him as ruler of Gwynedd. At this time, Llywelyn went on crusade with Richard of Cornwall, brother of Henry III of England.[2] Llywelyn's father, Gruffydd (who was Llywelyn's eldest son but illegitimate), and his brother, Owain, were initially kept prisoner by Dafydd, then transferred into the custody of King Henry III of England. Gruffydd died in 1244, from a fall while trying to escape from his cell at the top of the Tower of London.[3] The window from which he attempted to escape the Tower was bricked up and can still be seen to this day.

This freed Dafydd ap Llywelyn's hand as King Henry could no longer use Gruffydd against him, and war broke out between him and King Henry in 1245. Llywelyn supported his uncle in the savage fighting that followed. Owain, meanwhile, was freed by Henry after his father's death in the hope that he would start a civil war in Gwynedd, but stayed in Chester, so when Dafydd died in February 1246 without leaving an heir, Llywelyn had the advantage of being on the spot.

Early reign

Llywelyn and Owain came to terms with King Henry and in 1247, signed the Treaty of Woodstock at Woodstock Palace.[4] The terms they were forced to accept restricted them to Gwynedd Uwch Conwy, the part of Gwynedd west of the River Conwy, which was divided between them. Gwynedd Is Conwy, east of the river, was taken over by King Henry.

When Dafydd ap Gruffydd came of age, King Henry accepted his homage and announced his intention to give him part of the already reduced Gwynedd. Llywelyn refused to accept this, and Owain and Dafydd formed an alliance against him. This led to the Battle of Bryn Derwin in June 1255. Llywelyn defeated Owain and Dafydd and captured them, thereby becoming sole ruler of Gwynedd Uwch Conwy. Llywelyn now looked to expand his area of control. The population of Gwynedd Is Conwy resented English rule. This area, also known as "Perfeddwlad" (meaning 'middle land') had been given by King Henry to his son Edward and during the summer of 1256, he visited the area, but failed to deal with grievances against the rule of his officers. An appeal was made to Llywelyn, who, that November, crossed the River Conwy with an army, accompanied by his brother, Dafydd, whom he had released from prison. By early December, Llywelyn controlled all of Gwynedd Is Conwy apart from the royal castle at Dyserth as a reward for his support and dispossessing his brother-in-law, Rhys Fychan, who supported the king. An English army led by Stephen Bauzan invaded to try to restore Rhys Fychan but was decisively defeated by Welsh forces at the Battle of Cadfan in June 1257, with Rhys having previously slipped away to make his peace with Llywelyn.[5]

Rhys Fychan now accepted Llywelyn as overlord, but this caused problems for Llywelyn, as Rhys's lands had already been given to Maredudd. Llywelyn restored his lands to Rhys, but the king's envoys approached Maredudd and offered him Rhys's lands if he would change sides. Maredudd paid homage to Henry in late 1257. By early 1258, Llywelyn was using the title Prince of Wales, first used in an agreement between Llywelyn and his supporters and the Scottish nobility associated with the Comyn family. The English Crown refused to recognise this title however,[6] and in 1263, Llywelyn's brother, Dafydd, went over to King Henry.

On 12 December 1263 in the commote of Ystumanner, Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn did homage and swore fealty to Llywelyn. In return he was made a vassal lord and the lands taken from him by Llywelyn about six years earlier were restored to him.[7]

In England, Simon de Montfort (the Younger) defeated the king's supporters at the Battle of Lewes in 1264, capturing the king and the Lord Edward. Llywelyn began negotiations with de Montfort, and in 1265, offered him 30,000 marks in exchange for a permanent peace, in which Llywelyn's right to rule Wales would be acknowledged. The Treaty of Pipton, 22 June 1265, established an alliance between Llywelyn and de Montfort, but the very favourable terms given to Llywelyn in this treaty were an indication of de Montfort's weakening position. De Montfort was to die at the Battle of Evesham in 1265, a battle in which Llywelyn took no part.

Supremacy in Wales

After Simon de Montfort's death, Llywelyn launched a campaign in order to rapidly gain a bargaining position before King Henry had fully recovered. In 1265, Llywelyn captured Hawarden Castle and routed the combined armies of Hamo Lestrange and Maurice fitz Gerald in north Wales. Llywelyn then moved on to Brycheiniog, and in 1266, he routed Roger Mortimer's army. With these victories and the backing of the papal legate, Ottobuono, Llywelyn opened negotiations with the king, and was eventually recognised as Prince of Wales by King Henry in the Treaty of Montgomery in 1267. In return for the title, the retention of the lands he had conquered and the homage of almost all the native rulers of Wales, he was to pay a tribute of 25,000 marks in yearly installments of 3,000 marks, and could if he wished, purchase the homage of the one outstanding native prince - Maredudd ap Rhys of Deheubarth - for another 5,000 marks. However, Llywelyn's territorial ambitions gradually made him unpopular with some minor Welsh leaders, particularly the princes of south Wales.

The Treaty of Montgomery marked the high point of Llywelyn's power. Problems began arising soon afterwards, initially a dispute with Gilbert de Clare concerning the allegiance of a Welsh nobleman holding lands in Glamorgan. Gilbert built Caerphilly Castle in response to this. King Henry sent a bishop to take possession of the castle while the dispute was resolved but when Gilbert regained the castle by trickery, the king was unable to do anything about it.

Following the death of King Henry in late 1272, with the new King Edward I of England away from the kingdom, the rule fell to three men. One of them, Roger Mortimer was one of Llywelyn's rivals in the marches. When Humphrey de Bohun tried to take back Brycheiniog, which was granted to Llywelyn by the Treaty of Montgomery, Mortimer supported de Bohun. Llywelyn was also finding it difficult to raise the annual sums required under the terms of this treaty, and ceased making payments.

In early 1274, there was a plot by Llywelyn's brother, Dafydd, and Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn of Powys Wenwynwyn and his son, Owain, to kill Llywelyn. Dafydd was with Llywelyn at the time, and it was arranged that Owain would come with armed men on 2 February to carry out the assassination; however, he was prevented by a snowstorm. Llywelyn did not discover the full details of the plot until Owain confessed to the Bishop of Bangor. He said that the intention had been to make Dafydd prince of Gwynedd, and that Dafydd would reward Gruffydd with lands. Dafydd and Gruffydd fled to England where they were maintained by the king and carried out raids on Llywelyn's lands, increasing Llywelyn's resentment. When Edward called Llywelyn to Chester in 1275 to pay homage, Llywelyn refused to attend.

Llywelyn also made an enemy of King Edward by continuing to ally himself with the family of Simon de Montfort, even though their power was now greatly reduced. Llywelyn sought to marry Eleanor de Montfort, born in 1252, Simon de Montfort's daughter. They were married by proxy in 1275, but King Edward took exception to the marriage, in part because Eleanor was his first cousin: her mother was Eleanor of England, daughter of King John and princess of the House of Plantagenet. When Eleanor sailed from France to meet Llywelyn, Edward hired pirates to seize her ship and she was imprisoned at Windsor Castle until Llywelyn made certain concessions.

In 1276, Edward declared Llywelyn a rebel and in 1277, gathered an enormous army to march against him. Edward's intention was to disinherit Llywelyn completely and take over Gwynedd Is Conwy himself. He was considering two options for Gwynedd Uwch Conwy: either to divide it between Llywelyn's brothers, Dafydd and Owain, or to annex Anglesey and divide only the mainland between the two brothers. Edward was supported by Dafydd ap Gruffydd and Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn. Many of the lesser Welsh princes who had supported Llywelyn now hastened to make peace with Edward. By the summer of 1277, Edward's forces had reached the River Conwy and encamped at Deganwy, while another force had captured Anglesey and took possession of the harvest there. This deprived Llywelyn and his men of food, forcing them to seek terms.

Treaty of Aberconwy

What resulted was the Treaty of Aberconwy, which guaranteed peace in Gwynedd in return for several difficult concessions from Llywelyn, including confining his authority to Gwynedd Uwch Conwy once again. Part of Gwynedd Is Conwy was given to Dafydd ap Gruffydd, with a promise that if Llywelyn died without an heir, he would be given a share of Gwynedd Uwch Conwy instead.

Llywelyn was forced to acknowledge the English king as his sovereign; initially he had refused, but after the events of 1276, Llywelyn was stripped of all but a small portion of his lands. He went to meet Edward, and found Eleanor lodged with the royal family at Worcester; after Llywelyn agreed to Edward's demands, Edward gave them permission to be married at Worcester Cathedral. A stained glass window exists to this day depicting the wedding of the Prince of Wales and Lady Eleanor. By all accounts, the marriage was a genuine love match; Llywelyn is not known to have fathered any illegitimate children, which is extremely unusual for the Welsh royalty. (In medieval Wales, illegitimate children were as entitled to their father's property as legitimate children.)

Last campaign and death

By early 1282, many of the lesser princes who had supported Edward against Llywelyn in 1277 were becoming disillusioned with the exactions of the royal officers. On Palm Sunday that year, Dafydd ap Gruffydd attacked the English at Hawarden Castle and then laid siege to Rhuddlan. The revolt quickly spread to other parts of Wales, with Aberystwyth castle captured and burnt and rebellion in Ystrad Tywi in south Wales, also inspired by Dafydd according to the annals, where Carreg Cennen castle was captured.

Llywelyn, according to a letter he sent to the Archbishop of Canterbury John Peckham, was not involved in the planning of the revolt. He felt obliged, however, to support his brother and a war began for which the Welsh were ill-prepared. Personal tragedy also struck him at this time when, on or about 19 June 1282, his wife, Eleanor de Montfort, died shortly after giving birth to their daughter, Gwenllian. Their previous daughter, Princess Catherine, had been married to Philip ap Ivor, Lord of Cardigan.[8]

Events followed a similar pattern to 1277, with Edward's forces capturing Gwynedd Is Conwy, Anglesey and taking the harvest. The English force occupying Anglesey tried to cross to the mainland on a bridge of boats, but failed and was defeated in the Battle of Moel-y-don. The Archbishop of Canterbury tried mediating between Llywelyn and Edward, and Llywelyn was offered a large estate in England if he would surrender Wales to Edward, while Dafydd was to go on crusade and not return without the king's permission.[2] In an emotional reply, which has been compared to the Declaration of Arbroath, Llywelyn said he would not abandon the people whom his ancestors had protected since "the days of Kamber son of Brutus" and rejected the offer.

Llywelyn now left Dafydd to lead the defence of Gwynedd and took a force south, trying to rally support in mid and south Wales and open up an important second front. On 11 December at the Battle of Orewin Bridge at Builth Wells, he was killed while separated from his army. The exact circumstances are unclear and there are two conflicting accounts of his death. Both accounts agree that Llywelyn was tricked into leaving the bulk of his army and was then attacked and killed. The first account says that Llywelyn and his chief minister approached the forces of Edmund Mortimer and Hugh Le Strange after crossing a bridge. They then heard the sound of battle as the main body of his army was met in battle by the forces of Roger Despenser and Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn. Llywelyn turned to rejoin his forces and was pursued by a lone lancer who struck him down. It was not until some time later that an English knight recognised the body as that of the prince. This version of events was written in the north of England some fifty years later and has suspicious similarities with details about the Battle of Stirling Bridge in Scotland.

An alternative version of events written in the east of England by monks in contact with Llywelyn's exiled daughter, Gwenllian ferch Llywelyn, and niece, Gwladys ferch Dafydd, states that Llywelyn, at the front of his army, approached the combined forces of Edmund and Roger Mortimer, Hugo Le Strange, and Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn on the promise that he would receive their homage. This was a deception. His army was immediately engaged in fierce battle during which a significant section of it was routed, causing Llywelyn and his eighteen retainers to become separated. At around dusk, Llywelyn and a small group of his retainers (which included clergy) were ambushed and chased into a wood at Aberedw. Llywelyn was surrounded and struck down. As he lay dying, he asked for a priest and gave away his identity. He was then killed and his head hewn from his body. His person was searched and various items recovered, including a list of "conspirators", which may well have been faked, and his privy seal.

If the king wishes to have the copy [of the list] found in the breeches of Llywelyn, he can have it from Edmund Mortimer, who has custody of it and also of Llywelyn’s privy seal and certain other things found in the same place.

— Archbishop Peckham, in his first letter to Robert Bishop of Bath and Wells, 17 December 1282 (Lambeth Palace Archives)[9]

The privy seal of Llywelyn the Last, his wife Eleanor and his brother Dafydd are thought to have been melted down by the English after finding them upon their bodies to make a chalice in 1284.[10]

There are legends surrounding the fate of Llywelyn's severed head. It is known that it was sent to Edward at Rhuddlan and after being shown to the English troops based in Anglesey, Edward sent the head on to London. In London, it was set up in the city pillory for a day, and crowned with ivy (i.e. to show he was a "king" of Outlaws and in mockery of the ancient Welsh prophecy, which said that a Welshman would be crowned in London as king of the whole of Britain). Then it was carried by a horseman on the point of his lance to the Tower of London and set up over the gate. It was still on the Tower of London 15 years later.[9]

The last resting place of Llywelyn's body is not known for certain; however, it has always been tradition that it was interred at the Cistercian Abbey at Abbeycwmhir. On 28 December 1282, Archbishop Peckham wrote a letter to the Archdeacon of Brecon at Brecon Priory, in order to

... inquire and clarify if the body of Llywelyn has been buried in the church of Cwmhir, and he was bound to clarify the latter before the feast of Epiphany, because he had another mandate on this matter, and ought to have certified the lord Archbishop before Christmas, and has not done so.[9]

There is further supporting evidence for this hypothesis in the Chronicle of Florence of Worcester:

As for the body of the Prince, his mangled trunk, it was interred in the Abbey of Cwm Hir, belonging to the Cistercian Order.[9]

Another theory is that his body was transferred to Llanrumney Hall in Cardiff.[11]

The poet Gruffudd ab yr Ynad Coch wrote in an elegy on Llywelyn:

Do you not see the path of the wind and the rain?

Do you not see the oak trees in turmoil?

Cold my heart in a fearful breast

For the king, the oaken door of Aberffraw

There is an enigmatic reference in the Welsh annals Brut y Tywysogion, "… and then Llywelyn was betrayed in the belfry at Bangor by his own men". No further explanation is given.

Annexation

With the loss of Llywelyn, Welsh morale and the will to resist diminished. Dafydd was Llywelyn's named successor. He carried on the struggle for several months, but in June 1283 was captured in the uplands above Abergwyngregyn at Bera Mountain together with his family. He was brought before Edward, then taken to Shrewsbury where a special session of Parliament condemned him to death. He was dragged through the streets, hanged, drawn and quartered.

After the final defeat of 1283, Gwynedd was stripped of all royal insignia, relics, and regalia. Edward took particular delight in appropriating the royal home of the Gwynedd dynasty. In August 1284, he set up his court at Abergwyngregyn, Gwynedd. With equal deliberateness, he removed all the insignia of majesty from Gwynedd; a coronet was solemnly presented to the shrine of St. Edward at Westminster; the matrices of the seals of Llywelyn, of his wife, and of his brother Dafydd were melted down to make a chalice which was given by the king to Vale Royal Abbey where it remained until the dissolution of that institution in 1538, after which it came into the possession of the family of the final abbot.[12]) The most precious religious relic in Gwynedd, the fragment of the True Cross known as Cross of Neith, was paraded through London in May 1285 in a solemn procession on foot led by the king, the queen, the archbishop of Canterbury and fourteen bishops, and the magnates of the realm. Edward was thereby appropriating the historical and religious regalia of the house of Gwynedd and placarding to the world the extinction of its dynasty and the annexation of the principality to his Crown. Commenting on this a contemporary chronicler is said to have declared "and then all Wales was cast to the ground."[13]

Most of Llywelyn's relatives ended their lives in captivity with the notable exceptions of his younger brother Rhodri ap Gruffydd, who had long since sold his claim to the crown and endeavoured to keep a very low profile, and a distant cousin, Madog ap Llywelyn, who in 1294 led a revolt and briefly claimed the title Prince of Wales. Llywelyn and Eleanor's baby daughter Gwenllian of Wales was captured by Edward's troops in 1283. She was interned at Sempringham Priory in England for the rest of her life, becoming a nun in 1317 and dying without issue in 1337, probably knowing little of her heritage and speaking none of her language.

Dafydd's two surviving sons were captured and incarcerated at Bristol Gaol, where they eventually died many years later. Llywelyn's elder brother Owain Goch disappears from the record in 1282. Llywelyn's surviving brother Rhodri (who had been exiled from Wales since 1272) survived and held manors in Gloucestershire, Cheshire, Surrey, and Powys and died around 1315. His grandson, Owain Lawgoch, later claimed the title Prince of Wales.

Family tree

| Llywelyn the Great 1173–1195–1240 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gruffydd ap Llywelyn 1198–1244 | Dafydd ap Llywelyn 1212–1240–1246 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owain Goch ap Gruffydd d. 1282 | Llywelyn ap Gruffydd 1223–1246–1282 | Dafydd ap Gruffydd 1238–1282–1283 | Rhodri ap Gruffydd 1230–1315 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gwenllian of Wales 1282–1337 | Llywelyn ap Dafydd 1267–1283–1287 | Owain ap Dafydd 1275–1287–c. 1325 | Tomas ap Rhodri 1300–1325–1363 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In popular culture

The life of Llywelyn the Last is the subject of Edith Pargeter's Brothers of Gwynedd Quartet: 'Sunrise in the West' (1974); 'The Dragon at Noonday' (1975); 'The Hounds of Sunset' (1976); and 'Afterglow and Nightfall' (1977).

The 1982 Bardic Chair at the National Eisteddfod of Wales was awarded to Gerallt Lloyd Owen for his awdl Cilmeri, which Hywel Teifi Edwards has called the only 20th-century awdl, that matches T. Gwynn Jones' 1902 masterpiece Ymadawiad Arthur ("The Passing of Arthur"). Owen's Cilmeri reimagines the death of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in battle near the village of the same name on 11 December 1282, while leading his doomed uprising against the occupation of Wales by King Edward I of England. Owen's poem depicts the Prince as a tragic hero and invests his fall with an anguish unmatched since Gruffudd ab yr Ynad Coch wrote his famous lament for the Prince immediately following his death. Owen also, according to Edwards, encapsulates in the Prince's death the Welsh people's continuing "battle for national survival."[15]

The lives of Llywelyn Fawr, Llywelyn ap Gruffydd and Dafydd ap Gruffydd are the subject of Sharon Kay Penman's "Welsh Trilogy": Here be Dragons (1985); Falls the Shadow (1988); and The Reckoning (1991).

An alternate history/time travel science fiction series, After Cilmeri by Sarah Woodbury, explores what might have happened if Llywelyn had survived the ambush at Cilmeri, and had a son and assistance from people from the future.

Llywelyn the Last is the subject of the New Riders of the Purple Sage song "Llewellyn". The song focuses on the Conquest of Wales by Edward I, but specifically on the Campaign of 1282–83. In the song, the band claims "In September, Edward [Edward I] moved up to the baird/ His forces stronger every day/ Llewellyn then turned southward bound/ His forces lay upon the ground." It also claims that the message of Llywelyn's death came "soon thereafter."

Llywelyn is a minor character in Jean Plaidy's novel Edward Longshanks, the seventh novel of the Plantagenet Saga series.

Bertrice Small includes Llywelyn's life in her book, A Memory of Love, which centres on the fictional life of one of his illegitimate children, Rhonwyn.

See also

- Castell Du

- List of rulers of Wales

Notes

- According to several non-contemporary Welsh genealogical tracts, the mother of Llywelyn was Rhanullt, an otherwise unknown daughter of Rǫgnvaldr Guðrøðarson, King of the Isles. If correct, these sources could indicate that Llywelyn's father married a daughter of Rǫgnvaldr in about 1220. Contemporary sources, however, show that Llywelyn's mother was Senana.

References

- Colin A. Gresham (1973). Eifionydd: a Study in Landownership from the Medieval Period to the Present Day. University of Wales Press. p. 345. ISBN 978-0-7083-0435-8.

- Hurlock, Kathryn (2011). Wales and the Crusades, c. 1095-1291. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. pp. 111–112, 193–199. ISBN 978-0708324271.

- Wynford Vaughan-Thomas (1985). Wales, a History. M. Joseph. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-7181-2468-7.

- Davies, John History of Wales p.140

- Lloyd, J.E. A history of Wales p.720-1

- Moore, D. 'The Welsh Wars of Independence', Stroud 2005, p.135

- Smith, J Beverley (2014). Llywelyn ap Gruffydd: Prince of Wales. University of Wales Press.

- "The Royal Families of England, Scotland, and Wales, with Pedigrees of Royal Descents in Illustration" (PDF). Sir Bernard Burke, C.B., LL.D., Ulster King of Arms. 1876. p. 51. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- "Death of Llywelyn". Cilmeri. 10 December 2006. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- Schofield, Phillipp R.; McEwan, John; New, Elizabeth; Johns, Sue (15 June 2016). Seals and Society: Medieval Wales, the Welsh Marches and their English Border Region. University of Wales Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-78316-872-9.

- Williams, Tryst (8 August 2005). "Last true Welsh prince buried under pub?". Western Mail. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- "Houses of Cistercian monks: The abbey of Vale Royal". A History of the County of Chester. Vol. 3. London: Victoria County History. 1980. pp. 156–165.

- Davies, Rees (1 May 2001). "Wales: A Culture Preserved". bbc.co.uk/history. p. 3. Retrieved 6 May 2008.

- Prestwich, Michael (1997). Edward I. New Haven. ISBN 978-0-300-14665-3. OCLC 890476967.

- Edwards (2016), The Eisteddfod, pages 51-53.

Further reading

- Evans, Gwynfor (2001). Cymru O Hud [Welsh are still here]. Abergwyngregyn. ISBN 0-86243-545-5. - (English version), Evans, Gwynfor; Morgan, Mihangel (2002). Eternal Wales. Abergwyngregyn. ISBN 0-86243-608-7.

- Lloyd, John Edward (1911). A History of Wales, from the Earliest Times to the Edwardian Conquest. archive.org. Vol. II (Reprint Vol. 2 of 2 ed.). Longmans, Green & Co. ISBN 978-1-334-06136-3.

- Maund, Kari L. (2006). The Welsh Kings: Warriors, Warlords, and Princes. searchworks.stanford.edu (3rd ed.). Tempus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7524-2973-1.

- Pierce, T. Jones (1962). Cymdeithas Hanes Sir Caernarfon- Trafodion [Caernarfronshire History society talks]. Abergwyngregyn.

- Smith, Beverley J. (2001). Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, Prince of Wales. University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-1474-6.

- Stephenson, David (1984). The Governance of Gwynedd. University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-0850-9. OL 22379507M.

- Y Traethodydd [The Essayist]. July 1998. ISSN 0969-8930.

Garth Celyn evidence (Tystiolaeth Garth Celyn)

External links

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Llewelyn". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1893). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 34. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 13–21.

- "LLYWELYN ap GRUFFYDD ('Llywelyn the Last,' or Llywelyn II), Prince of Wales (died 1282)". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales.

- Death of Llywelyn. Cilmeri is another name for Cefn-y-Bedd ("Ridge of the Grave"), a burial mound where Llywelyn is said to have been slain.

- Places and artifacts associated with Llywelyn the Last