Lombard language

Lombard (native name: lombard[N 1] / lumbáart,[N 2] depending on the orthography; pronounced [lũˈbɑːrt] or [lomˈbart]) is a Gallo-Romance language,[6] spoken by millions of speakers in Northern Italy and Southern Switzerland, including most of Lombardy and some areas of neighbouring regions, notably the eastern side of Piedmont and the western side of Trentino, and in Switzerland in the cantons of Ticino and Graubünden.[7] Lombard is also spoken in Santa Catarina in Brazil by Lombard immigrants from the Province of Bergamo.[4][8]

| Lombard | |

|---|---|

| lombard / lumbaart | |

| Native to | Italy, Switzerland |

| Region | Italy[1][2][3]

Brazil[4] |

Native speakers | 3.8 million (2002)[5] |

| Dialects |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | lmo |

| Glottolog | lomb1257 |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAA-oc & 51-AAA-od |

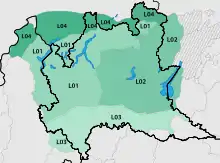

Lombard language distribution in Europe:

Areas where Lombard is spoken

Areas where Lombard is spoken alongside other languages (Alemannic, Ladin and Romansh) and areas of linguistic transition (with Piedmontese, with Emilian and with Venetian)

Areas of influence of Lombard (Tridentine dialect)

? Areas of uncertain diffusion of Ladin | |

Lombard is classified as Definitely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

Origins

The most ancient linguistic substratum that has left a mark on the Lombard language is that of the ancient Ligures.[9][10] However, available information about this ancient language and its influence on modern Lombard is extremely vague and limited.[9][10] This is in sharp contrast to the influence left by the Celts who settled Northern Italy and brought their Celtic languages, also culturally and linguistically Celticizing the Ligures.[11] The Celtic substratum of modern Lombard and neighboring languages of Northern Italy is self-evident, so that the Lombard language is classified as a Gallo-Italic language (from the ancient Roman name for identifying the Celts, that is Gauls).[9]

Roman domination shaped the dialects spoken in the area, which was called Cisalpine Gaul by the Romans, so that much of the lexicon and grammar of the Lombard language find their origin in the Latin language.[11] Yet, such influence was not homogeneous;[9] idioms of different areas were influenced by previous linguistic substrata, and each area was marked by a stronger or weaker Latinisation or preservation of ancient Celtic characteristics.[9]

Also the Germanic Lombardic language left strong traces in modern Lombard language, as it was the variety of Germanic spoken by the Germanic Lombards (or Longobards), who settled all Northern Italy (called Greater Lombardy after them) and other parts of the Italian peninsula after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Lombardic acted as a linguistic superstratum on Lombard and neighboring Gallo-Italic languages, since the Germanic Lombards did not impose their language by law on the Gallo-Roman population, but rather acquired the Gallo-Italic language from the local population. Lombardic left traces, mostly in lexicon and phonetics, without Germanicizing the local language in its structure, so that Lombard preserved its Romance structure.[12]

Status

Lombard is considered a minority language, structurally separate from Italian, by Ethnologue and by the UNESCO Red Book on Endangered Languages. However, Italy and Switzerland do not recognize Lombard speakers as a linguistic minority. In Italy this is the same as for most other minority languages,[13] which have been for long time incorrectly devalued as corrupted regional dialects of Italian—despite the fact that they belong to different subgroups of the Romance language family, and their historical development is not related to standard Italian (derived from Tuscan).[14]

Speakers

Historically, the vast majority of Lombards spoke Lombard only.[15] With the rise of standard Italian throughout Italy and Lombard-speaking Switzerland, one is not likely to find wholly monolingual Lombard speakers, but a small minority may still be uncomfortable speaking standard Italian. Surveys in Italy find that all Lombard speakers also speak Italian, and their command of each of the two languages varies according to their geographical position as well as their socio-economic situation. The most reliable predictor was found to be the speaker's age: studies have found that young people are much less likely to speak Lombard as proficiently as their grandparents did.[16] In some areas, elderly people are more used to speaking Lombard than Italian, even though they know the latter as well as the former.

Classification

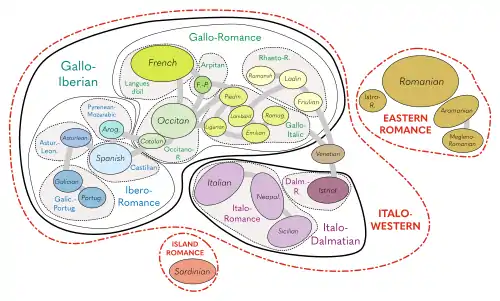

Lombard belongs to the Gallo-Italic (Cisalpine) group of Gallo-Romance languages, which belongs to the Western Romance subdivision.[17]

Varieties

Traditionally, the Lombard dialects have been classified into the Eastern, Western, Alpine, and Southern Lombard dialects.[18]

The varieties of the Italian provinces of Milan, Varese, Como, Lecco, Lodi, Monza and Brianza, Pavia and Mantua belong to Western Lombard, and the ones of Bergamo, Brescia and Cremona are dialects of Eastern Lombard. All the varieties spoken in the Swiss areas (both in canton Ticino and canton Graubünden) are Western, and both Western and Eastern varieties are found in the Italian areas.

The varieties of the Alpine valleys of Valchiavenna and Valtellina (province of Sondrio) and upper-Valcamonica (province of Brescia) and the four Lombard valleys of the Swiss canton of Graubünden, although they have some peculiarities of their own and some traits in common with Eastern Lombard, should be considered Western. Also, dialects from the Piedmontese provinces of Verbano-Cusio-Ossola and Novara, the Valsesia valley (province of Vercelli), and the city of Tortona are closer to Western Lombard than to Piedmontese. Alternatively, following the traditional classification, the varieties spoken in parts of Sondrio, Trento, Ticino and Grigioni can be considered as Alpine Lombard,[19] while those spoken in southern Lombardy such as in Pavia, Lodi, Cremona and Mantova can be classified as Southern Lombard.[20]

Literature

The Lombard variety with the oldest literary tradition (from the 13th century) is that of Milan, but Milanese, the native Lombard variety of the area, has now almost completely been superseded by Italian from the heavy influx of immigrants from other parts of Italy (especially Apulia, Sicily, and Campania) during the fast industrialization after the Second World War.

Ticinese is a comprehensive denomination for the Lombard varieties spoken in Swiss canton Ticino (Tessin), and the Ticinese koiné is the Western Lombard koiné used by speakers of local dialects (particularly those diverging from the koiné itself) when they communicate with speakers of other Lombard dialects of Ticino, Grigioni, or Italian Lombardy. The koiné is similar to Milanese and the varieties of the neighbouring provinces on the Italian side of the border.

There is extant literature in other varieties of Lombard, for example La masséra da bé, a theatrical work in early Eastern Lombard, written by Galeazzo dagli Orzi (1492–?) presumably in 1554.[21]

Usage

Standard Italian is widely used in Lombard-speaking areas. However, the status of Lombard is quite different in the Swiss and Italian areas, so that the Swiss areas have now become the real stronghold of Lombard.

In Switzerland

In the Swiss areas, the local Lombard varieties are generally better preserved and more vital than in Italy. No negative feelings are associated with the use of Lombard in everyday life, even with complete strangers. Some radio and television programmes, particularly comedies, are occasionally broadcast by the Swiss Italian-speaking broadcasting company in Lombard. Moreover, it is common for people to answer in Lombard in spontaneous interviews. Even some television ads have been broadcast in Lombard. The major research institution working on Lombard dialects is located in Bellinzona, Switzerland (CDE – Centro di dialettologia e di etnografia, a governmental (cantonal) institution); there is no comparable institution in Italy. In December 2004, the CDE released a dictionary in five volumes, covering all the Lombard varieties spoken in the Swiss areas.[N 2]

In Italy

Today, in most urban areas of Italian Lombardy, people under 40 years old speak almost exclusively Italian in their daily lives because of schooling and television broadcasts in Italian. However, in rural areas, Lombard is still vital and used alongside Italian.

A certain revival of the use of Lombard has been observed in the last decade. The popularity of modern artists singing their lyrics in some Lombard dialect (in Italian rock dialettale, the best known of such artists being Davide Van de Sfroos) is also a relatively new but growing phenomenon involving both the Swiss and Italian areas.

Lombard is spoken in Campione d'Italia, an exclave of Italy surrounded by Swiss territory on Lake Lugano.

Phonology

The following tables show the sounds used in all dialects of Lombard.

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/

Alveolar |

Post-alv./

Palatal |

Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | (ŋ) | |

| Stop | voiceless | p | t | c | k |

| voiced | b | d | ɟ | ɡ | |

| Affricate | voiceless | t͡s | tɕ | ||

| voiced | d͡z | dʑ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | |

| voiced | z | ʒ | |||

| Sonorant | central | ʋ | r | j | w |

| lateral | l | (ʎ) | |||

In Eastern Lombard and Pavese dialect, /dz/, /z/ and /ʒ/ merge to [z] and /ts/, /s/ and /ʃ/ to [s]. In Eastern Lombard, the last sound is often further debuccalized to [h].

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrounded | Rounded | Unrounded | Rounded | ||

| Close | i iː | y yː | u u: | ||

| Near-close | ɪ | ʏ | ʊ ʊ: | ||

| Close-mid | e eː | ø øː | o | ||

| Open-mid | ɛ | (œ)[23] | ɔ | ||

| Near-open | ɐ[24] | ||||

| Open | a aː | ɑ ɑː | ɒ ɒ: | ||

In Western varieties, vowel length is contrastive (e.g. Milanese andà "to go" vs andàa "gone"),[22] but Eastern varieties normally use only short allophones.

When two repeating orthographic vowels that are separated by a dash, that prevents them from being confused with the long vowel, such as a-a in ca-àl "horse".[22]

Western long /aː/ and short /ø/ tend to be back [ɑː] and lower [œ], respectively. /e/ and /ɛ/ may merge to [ɛ].

See also

- Diachronics of plural inflection in the Gallo-Italian languages

- Emilian-Romagnol language

- Gallo-Italic of Sicily

- La Spezia–Rimini Line

- Languages of Europe

- Ligurian language

- Piedmontese language

- Pierre Bec

- Romance plurals

- Venetian language

Notes

- Classical Milanese orthography

- "Lessico dialettale della Svizzera italiana (LSI)" [Dialectal Lexicon of Italian Switzerland (LSI)], Centro di dialettologia e di etnografia (in Italian), archived from the original on 2005-11-23

References

- Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, many nations: a historical dictionary of European national groups. Westport.

- Moseley, Christopher (2007). Encyclopedia of the world's endangered languages. New York.

- Coluzzi, Paolo (2007). Minority language planning and micronationalism in Italy. Berne.

- Spoken in Botuverá, in Brazil, municipality established by Italian migrants coming from the valley between Treviglio and Crema. A thesis of Leiden University about Brasilian Bergamasque: .

- Lombard at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- "Documentation for ISO 639 identifier: LMO".

Identifier: LMO - Language(s) Name: Lombard - Status: Active - Code set: 639-3 - Scope: Individual - Type: Living

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Jones, Mary C.; Soria, Claudia (2015). "Assessing the effect of official recognition on the vitality of endangered languages: a case of study from Italy". Policy and Planning for Endangered Languages. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 130. ISBN 9781316352410. Archived from the original on 2017-04-21.

Lombard (Lumbard, ISO 639-9 lmo) is a cluster of essentially homogeneous varieties (Tamburelli 2014: 9) belonging to the Gallo-Italic group. It is spoken in the Italian region of Lombardy, in the Novara province of Piedmont, and in Switzerland. Mutual intelligibility between speakers of Lombard and monolingual Italian speakers has been reported as very low (Tamburelli 2014). Although some Lombard varieties, Milanese in particular, enjoy a rather long and prestigious literary tradition, Lombard is now mostly used in informal domains. According to Ethnologue, Piedmontese and Lombard are spoken by between 1,600,000 and 2,000,000 speakers and around 3,500,000 speakers, respectively. These are very high figures for languages that have never been recognised officially nor systematically taught in school

- Bonfadini, Giovanni. "lombardi, dialetti" [Lombard dialects]. Enciclopedia Treccani (in Italian).

- Agnoletto, p.120

- D'Ilario, p.28

- D'Ilario, p.29

- "Il milanese crogiuolo di tanti idiomi". Archived from the original on 2017-09-24.

- Coluzzi, P. (2004). Regional and Minority Languages in Italy. 'Marcator Working Papers', 14.

- von Wartburg, W. (1950). "Die Ausgliederung der romanischen Sprachräume", Bern, Francke.

- De Mauro, T. (1970) Storia linguistica dell'Italia unita (Second Edition), Laterza, Berkeley.

- 2006 report Archived 2010-07-04 at the Wayback Machine by the Italian institute for national statistics.(ISTAT)

- Tamburelli, Marco; Brasca, Lissander (2018). "Revisiting the classification of Gallo-Italic: a dialectometric approach". Digital Scholarship in the Humanities. 33 (2): 442–455. doi:10.1093/llc/fqx041.

- "Lingua lombarda". Lingua Lombarda (in Italian). Circolo Filologico Milanese.

- "Lombardo alpino". Lingua Lombarda (in Italian). Circolo Filologico Milanese.

- "Lombardo meridionale". Lingua Lombarda (in Italian). Circolo Filologico Milanese.

- Produzione e circolazione del libro a Brescia tra Quattro e Cinquecento: atti della seconda Giornata di studi "Libri e lettori a Brescia tra Medioevo ed età moderna" Valentina Grohovaz (Brescia, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore) 4 marzo 2004. Published by "Vita e Pensiero" in 2006, ISBN 88-343-1332-1, ISBN 978-88-343-1332-9 (Google Books).

- Sanga, Glauco (1984). Dialettologia Lombarda (in Italian). University of Pavia. pp. 283–285.

- [œ] occurs in most areas of the language but can overlap in usage with [ø], as they both share the same trigram (oeu).

- Common realization of unstressed final /a/

Bibliography

- Agnoletto, Attilio (1992). San Giorgio su Legnano - storia, società, ambiente. SBN IT\ICCU\CFI\0249761.

- D'Ilario, Giorgio (2003). Dizionario legnanese. Artigianservice. SBN IT\ICCU\MIL\0625963.

- Bernard Comrie, Stephen Matthews, Maria Polinsky (eds.), The Atlas of languages: the origin and development of languages throughout the world. New York 2003, Facts On File. p. 40.

- Brevini, Franco - Lo stile lombardo: la tradizione letteraria da Bonvesin da la Riva a Franco Loi / Franco Brevini - Pantarei, Lugan - 1984 (Lombard style: literary tradition from Bonvesin da la Riva to Franco Loi )

- Glauco Sanga: La lingua Lombarda, in Koiné in Italia, dalle origini al 500 (Koinés in Italy, from the origin to 1500), Lubrina publisher, Bèrghem.

- Claudio Beretta: Letteratura dialettale milanese. Itinerario antologico-critico dalle origini ai nostri giorni - Hoepli, 2003.

- G. Hull: "The linguistic Unity of Northern Italy and Rhaetia, PhD thesis, University of Sydney, 1982; published as The Linguistic Unity of Northern Italy and Rhaetia: Historical Grammar of the Padanian Language, 2 vols. Sydney: Beta Crucis Editions, 2017.

- Jørgen G. Bosoni: «Una proposta di grafia unificata per le varietà linguistiche lombarde: regole per la trascrizione», in Bollettino della Società Storica dell’Alta Valtellina 6/2003, p. 195-298 (Società Storica Alta Valtellina: Bormio, 2003). A comprehensive description of a unified set of writing rules for all the Lombard varieties of Switzerland and Italy, with IPA transcriptions and examples.

- Tamburelli, M. (2014). Uncovering the ‘hidden’ multilingualism of Europe: an Italian case study. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 35(3), 252-270.

- NED Editori: I quatter Vangeli de Mattee, March, Luca E Gioann - 2002.

- Stephen A. Wurm: Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger of Disappearing. Paris 2001, UNESCO Publishing, p. 29.

- Studi di lingua e letteratura lombarda offerti a Maurizio Vitale, (Studies in Lombard language and literature) Pisa: Giardini, 1983

- A cura di Pierluigi Beltrami, Bruno Ferrari, Luciano Tibiletti, Giorgio D'Ilario: Canzoniere Lombardo - Varesina Grafica Editrice, 1970.

- Sanga, Glauco. 1984. Dialettologia Lombarda. University of Pavia. 346pp.

External links

- Far Lombard This Lombard language association website is a place where you can learn Lombard through texts and audio visual materials.

- Lombard language digital library

- Learn Lombard online

- Learn Lombard Italian site

- Centro di dialettologia e di etnografia del Cantone Ticino.

- Repubblica e Cantone Ticino Documenti orali della Svizzera italiana. (in Italian)

- Istituto di dialettologia e di etnografia valtellinese e valchiavennasca.

- LSI - Lessico dialettale della Svizzera italiana.

- RTSI: Acquarelli popolari, some video and audio documents (interviews, recordings, etc. of writers from Ticino) in Ticinese varieties (please notice that the metalanguage of this site is Italian, and that some of the interviews are in Italian rather than in Ticinese Lombard).

- UNESCO Red Book on Endangered Languages: Europe. Potentially endangered languages, where Lombard is classified as a potentially endangered language.

- VSI - Vocabolario dei dialetti della Svizzera italiana.

- in_lombard website dedicated to the Lombard language (in English)

- Lombard basic lexicon at the Global Lexicostatistical Database

- Lombard Wiktionary in incubator