Lusaka

Lusaka (/luːˈsɑːkə/; loo-SAH-kə) is the capital and largest city of Zambia. It is one of the fastest-developing cities in southern Africa.[7] Lusaka is in the southern part of the central plateau at an elevation of about 1,279 metres (4,196 ft). As of 2019, the city's population was about 3.3 million, while the urban population is estimated at 2.5 million in 2018.[8] Lusaka is the centre of both commerce and government in Zambia and connects to the country's four main highways heading north, south, east and west. English is the official language of the city administration, while Tonga, Lenje, Soli, Lozi and Nyanja are the commonly spoken street languages.

Lusaka

Mwalusaka | |

|---|---|

City | |

From top: Lusaka city at night, Downtown Lusaka, Lusaka National Museum | |

Flag | |

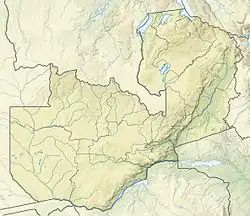

Lusaka Location of Lusaka in Zambia  Lusaka Lusaka (Africa) | |

| Coordinates: 15°25′S 28°17′E | |

| Country | Zambia |

| Province | Lusaka Province |

| District | Lusaka District |

| Established | 1905 |

| City status | 25 August 1960 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-council government |

| • Mayor | Chilando Chitangala (PF) |

| Area | |

| • City | 360 km2 (140 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,279[2] m (4,190 ft) |

| Population (2010 Census) | |

| • City | 1,747,152[3] |

| • Estimate (2020) | 2,731,696[4] |

| • Metro | 2,238,569 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (CAT) |

| Area code | 0211[5] |

| HDI (2018) | 0.664[6] Medium |

| Website | http://www.lcc.gov.zm |

The earliest evidence of settlement in the area dates to the 6th century AD, with the first known settlement in the 11th century. It was then home to the Lenje and Soli peoples from the 17th or 18th century. The founding of the modern city occurred in 1905 when it lay in the British protectorate of Northern Rhodesia, which was controlled by the British South African Company (BSAC). The BSAC built a railway linking their mines in the Copperbelt to Cape Town and Lusaka was designated as a water stop on that line, named after a local Lenje chief called Lusaaka. White Afrikaner farmers then settled in the area and expanded Lusaka into a regional trading centre, taking over its administration. In 1929, five years after taking over control of Northern Rhodesia from the BSAC, the British colonial administration decided to move its capital from Livingstone to a more central location, and Lusaka was chosen. Town planners including Stanley Adshead worked on the project, and the city was built out over the subsequent decades.

Lusaka lost some of its status to Salisbury (now Harare in Zimbabwe) when the latter became the capital of the merged Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland in 1953, but regained it when it was named the capital of newly independent Zambia in 1964. A large-scale building programme in the city followed, including government buildings, the University of Zambia and a new airport. Wealthy suburbs in Lusaka include Woodlands, Ibex Hill and Rhodes Park. Large-scale migration of people from other areas of Zambia occurred both before and after independence, and a lack of sufficient formal housing led to the emergence of numerous unplanned shanty towns on the city's western and southern fringes.

History

Early history

The earliest evidence of settlement in the area around what is now the Lusaka area dates to the 6th century. The first known village dates to around the 11th century, a settlement of round huts close to the modern suburb of Olympia. The subsequent centuries saw considerable fluctuation of people in the area, until the arrival of the Lenje and Soli peoples in the 17th or 18th century.[9] The Soli are believed by scholars to have arrived as part of the Luba migration along the Luapula River,[10] while the Lenje are related to the Ila–Tonga.[11] Modern Lusaka lies on the boundary of the territories of the two groups, with the Lenje inhabiting the region to the north of the city and the Soli to the south.[12] In the 19th century, African and European slave traders began arriving from the coastal regions of modern-day Tanzania, Mozambique and Angola, enslaving members of the Soli and Lenje communities for shipment to the Middle East, Europe and South America.[9][13] The need to evade these attacks as well as their use of a shifting-cultivation farming system, necessitated frequent relocation amongst the Soli and Lenje, and there were, therefore, no major permanent settlements.[13]

In the late 19th century, British–South African mining entrepreneur and politician Cecil Rhodes founded the British South African Company (BSAC), with a charter from Queen Victoria to colonise and develop land in sections of what is now northern South Africa, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Malawi and Botswana.[14] Rhodes was a strong believer in the Cape to Cairo railway project, although with German East Africa blocking the route to the north of BSAC territory, he could not progress it during his lifetime.[15] With little regard for the human rights of the African populations, Rhodes personally led the conquest of territory as far as Salisbury (now Harare in Zimbabwe), and his company continued extending to the north even after his death in 1902.[14] The BSAC took formal control of the region around Lusaka through the protectorate of Barotziland–North-Western Rhodesia, named after Rhodes, in 1899.[16][17] The capital was initially at Kalomo, being switched to Livingstone in 1907.[18] This was merged in 1911 with the territory of North-Eastern Rhodesia to form Northern Rhodesia, predecessor of modern Zambia.[19]

Faced with uprisings by Africans within their territory, as well as an economic decline and a desire to expand mining interests in northern Zambia's Copperbelt, the BSAC expedited the building of the northbound railway from South Africa into Northern Rhodesia from 1896.[20][21] Lusaka was founded in 1905 as a water stop on the route and was named after a Chief Lusaaka, the leader of a nearby Lenje village.[9] The section of line through Lusaka was built by the Mashonaland Railway Company, extending the line by 452 kilometres (281 mi) from Kalomo through to the mining town of Broken Hill (now Kabwe).[22][23] During the subsequent years, white Afrikaner farmers settled in the area, Lusaka becoming their regional centre and access point to the railway. By 1913, several stores and a hotel had opened, and they persuaded the BSAC to declare Lusaka as a recognised town and cede control of local affairs to them.[13][9] This early town was governed by the Lusaka Village Management Board, elected by the farmers, and consisted of a tract of land along the railway route, 5 kilometres (3 mi) in length and 1.5 kilometres (0.9 mi) wide.[13]

After World War I, the United Kingdom took control Tanganyika (now Tanzania), which had been previously part of German East Africa. This created an almost continuous line of British colonies from South Africa through to Egypt and led to the revival of projects for the Cape to Cairo railway and a similar road route.[15][24] The British imperial government took direct control of Northern Rhodesia in 1924, through a governor and legislative council, but the BSAC retained its rights over mining acquired in prior decades.[24][25] The new administration favoured an indirect rule system with self-governance for the African population, although in reality the rights of Africans remained very limited.[26] The mining corporations, as well as Afrikaner farmers around Lusaka, did not welcome the change, favouring a South African model.[27][28] The colonial administration favoured the establishment of planned towns as a means of asserting its authority.[29]

Designation as Northern Rhodesia's capital

In March 1929, the UK's Colonial Office sent a telegram to the Northern Rhodesian government recommending that the capital of the territory be moved, citing "communications" and also "health" reasons.[29] However, the medical rationale for the relocation was not explicitly published at the time.[30] James Maxwell, a former physician and the protectorate's governor since 1927, brought his former colleague David Alexander from Nigeria to assist with him with this relocation project.[29] Keen to avoid the informal development of the townships that were emerging close to mining areas, Alexander recommended that a town planner be recruited to design the capital. Maxwell and Alexander then investigated possible sites for the new city, eventually choosing Lusaka as a result of its situation on the railway and at the crossroads of Northern Rhodesia's Great North Road and Great East Road.[13][31] Maxwell requested a town planner from the Colonial Office, which sent University College London professor Stanley Adshead, as well as a water engineer, to the colony. Adshead examined several possible locations for the capital, eventually confirming Lusaka as a suitable location in late 1930. He had considered placing the capital in the Copperbelt, but a mutual distrust between the mining corporations and the government meant that both preferred to maintain some distance between the capital and the mines.[31] The water engineer's investigations concluded that there was sufficient groundwater,[13] and the report confirming Lusaka as the planned capital was approved by the legislative council in July 1931.[31][30]

Ronald Storrs replaced Maxwell as governor in 1932, but funds were limited as a result of the Great Depression and there was little progress on the development of Lusaka. Several thousand Africans migrated to the city in search of construction work, but none was available, leading to large-scale poverty, hunger, and rioting.[32][33] Storrs's greatest interest in the project was the development of the Government House, echoing a similar project he had initiated as governor of Cyprus, when his headquarters was burned down in a revolt. Seeking to emulate the Cyprus building, as well as the recently completed viceroy's mansion in New Delhi, Storrs commissioned several top architects to work on the plan, which was presented at the Royal Academy. The £43,000 projected cost of the building was more than 10 per cent of the total budget earmarked for the Lusaka project and the Colonial Office insisted in late 1933 that it be reduced. Storrs left his post as governor shortly afterwards, on the grounds of ill health.[34] By that point, the completed work consisted of a few short stretches of road (including Cairo Road, named for its anticipated place on the proposed Cape to Cairo Road) and some houses and flats for government officials.[35][36]

Storrs's replacement as governor was Hubert Winthrop Young, who had been serving as governor of neighbouring Nyasaland (now Malawi). Early in his tenure, in April 1934, Young hosted a visit to Lusaka by Prince George, the fourth son of King George V.[37] During his visit, George laid the foundation stone of Lusaka's administrative buildings,[38] as well as opening roads named after his father and himself.[37] After the royal visit, Young wrote to the Colonial Office that he was "optimistic about the future of Lusaka", and he appointed administrator Eric Dutton to lead the project.[35] There was some resistance from the white population of Livingstone, which feared that the capital would lead to a loss of business. Young refused their demand to compensate them financially, but he sought to placate them by establishing Livingstone as the protectorate's tourism capital, with a new museum and a game reserve. Lusaka formally became the capital in May 1935, with a "Lusaka week" celebration scheduled to coincide with celebrations of George V's silver jubilee. The government commissioned a special train, which moved all government officials from Livingstone to Lusaka during a single weekend.[39]

Under Adshead's original plans, Lusaka was proposed as a pure administrative centre, with no industry or large African population; he commented at one point that it "could never become an important city".[13][40] Under Bowling's revised plans, there were areas designated for both light and heavy industry, as well as a business area.[13][41] He gave prominence to the airport, as well as to the government house, albeit under a simpler design than that envisaged by Storrs. Both men had built racial segregation into their plans, dividing the city into "native" and "non-native" areas, with residential areas and services for Africans placed on the southern periphery of the city. Despite producing these plans, both Adshead and Bowling had left Rhodesia before the Lusaka week, and the remainder of the building was left to Dutton and a small team of white officials.[41] The city's footprint covered a large area, even at this early stage, despite much of it being undeveloped. This was part of a policy devised by Adshead intended to allow internal expansion, rather than the usual central core with suburbs added outside.[42][43]

Later colonial years

The building of Lusaka continued through the second half of the 1930s, but progress was slowed by a shortage of funds. The Northern Rhodesia government had hoped to raise money through taxes on the mining companies, but these were mostly registered in the United Kingdom and paid all the tax on their revenues there. The loan taken to cover the project's £400,000 budget was guaranteed by the Beit Trust, but there was no scope for additional infrastructure to be built.[44] The UK launched an investigation into a possible merger of Southern Rhodesia, Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland in 1938, a prospect which caused private businesses to withdraw investment, fearing that Lusaka would lose its capital status. This left the government as the sole source of funds.[45] Also in 1938, the Northern Rhodesia government commissioned a report by finance expert Alan Pim, to examine the territory's economy. This concluded that despite the relatively high taxes on mining in the territory, the administration (which was already heavily reliant on revenue from mining) was not getting its fair share.[46] Pim also criticised the allocation of housing for Africans in Lusaka, noting that of 10,000 living in the city at that time, only 1,500 were in formal housing.[42] Africans were at that time only permitted to live in the city under temporary work permits, with family members required to remain elsewhere.[47]

The need for metals during World War II led to a boom in the copper industry which, accompanied by a 1941 excess-profits tax ordered by the UK, brought increased revenue to the government.[48] The boom also led to a substantial increase in urbanisation.[13] Lusaka's official population (which excluded much of the African population) rose from around 2,000 in 1931 to almost 19,000 in 1946, with a 15 per cent annual growth rate.[47] In 1948, the government passed the African Housing Ordinance, which authorised permanent residential suburbs for Africans, including married couples. Employers in the city were also required to pay for their workers' housing. The city authorities founded the African Housing Board, which built the new suburbs of New Chilenje and Matero. Lusaka's African workforce, which remained relatively unskilled, did not benefit as much as that of the Copperbelt, where a shortage of skilled mining labour had led to improved pay.[49] In 1952, a development plan for Lusaka gained statutory approval for the first time – earlier proposals such as those by Adshead and Bowling had never been legally sanctioned.[42] This plan envisaged much more territory for the African suburbs, but only around one-third of these were ever built.[50]

In 1953, the British government approved the pre-war plan to merge Northern Rhodesia with its two neighbours, forming the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. Authorities in London cited the economic benefits and the belief that the merged territory would form a "multiracial state" to counter the rise of Apartheid in South Africa. The federation was popular with white settlers across the region, especially in Southern Rhodesia, but was strongly opposed by the African population.[51] Lusaka remained the capital of Northern Rhodesia but many of the government departments, as well as some private sector industries, moved to Salisbury, which was designated as the federal capital. Lusaka's economy suffered as a result, with reduced jobs in construction, transportation, and domestic service. This economic decline, coupled with a fall in copper prices in the mid-to-late 1950s, resulted in large-scale unemployment among both African and white Lusakans. The population continued to grow, however, as increasing numbers moved from rural areas to the city's informal settlements.[50] In contrast to South Africa, where the government regularly bulldozed them, the authorities in Rhodesia tolerated these squatter areas although they provided no services and Africans continued to live under strict legal constraints.[52]

Capital of THE REPUBLIC OF Zambia

As discontent with federation rose, a new group of African leaders emerged in the late 1950s, seeking majority rule and independence for Northern Rhodesia, as had recently been attained in Ghana. After a civil disobedience in 1962, led by Kenneth Kaunda's United National Independence Party (UNIP), the UK Government agreed to a new constitution under which Africans took control of the legislature. The end of the federation followed in 1963, and in 1964, Northern Rhodesia became independent as the Republic of Zambia.[53] Lusaka was named as the capital of Zambia.[54] A large-scale building programme in the city followed, including: government buildings, the University of Zambia and a new airport. The employment opportunities that arose from this attracted further migration from rural areas into Lusaka, exacerbating the city's housing shortage. The government constructed several new housing estates during the 1960s, including New Kamwala and Chilenje South.[55] This was the first time that good-quality housing with public utilities had been built for the African population, although it was largely limited to civil servants and copper-industry workers, with the majority of residents continuing to live in the informal settlements.[55][56]

Although Zambia, Malawi and Tanzania had achieved independence by the mid-1960s,[51][57] the other nearby territories of Mozambique, Angola, Southern Rhodesia and South Africa were still under white minority control. Many activists from these territories moved to post-independence Lusaka, and American historian Evan Wade later described it as the "center of anti-colonial resistance for Southern Africa".[56][58] In 1969, the city hosted the Fifth Summit Conference of East and Central African States, attended by fourteen leaders of African countries. The conference produced the Lusaka Manifesto, a pledge of solidarity by the signatories in seeking majority rule in southern Africa. The manifesto advocated a strategy of negotiation rather than violence and was later endorsed by the United Nations.[58] The 1965 Unilateral Declaration of Independence in Southern Rhodesia and subsequent UN embargo and eventual border closure impacted Zambia's economy, depriving it of its principal trade route.[59]

In the early days of independence, with high revenues from copper exports, economists described Zambia as a "middle-income country" with the potential to become fully developed. Beginning in the 1970s, however, the Zambian economy suffered a major decline as a result of falling copper prices and rising oil prices.[59] Per capita income dropped by 50% between 1974-94. The slow-down also highlighted what American political scientist John Harbeson described as a "massive and inefficient parastatal sector as well as the government's prevailing urban bias", and led to a fall in formal employment in Lusaka which continued for several decades.[60] The lack of jobs decreased the level of rural-to-urban migration in Zambia,[61] but the decline of the copper industry caused a large movement of people from the Copperbelt cities to Lusaka. This, and the natural population growth in the city's young population, gave Lusaka a population growth of around 4% in the 1990s, exceeding the national average.[61]

The Zambian economy grew rapidly during the 2000s,[62] and the government initiated projects designed to improve the quality of housing and access to services in Lusaka.[63] These included a comprehensive urban development plan, prepared by the Zambian government and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), and an urban and regional planning bill, which was enacted in 2015.[64] Inequality and underinvestment in housing remain high, however, with 70% of residents still living in unplanned settlements in 2015.[63] In 2018, the city council began a programme of road improvements to tackle chronic traffic congestion, but the lack of quality housing and services remains an issue as of 2021.[65]

Geography

The Zambian terrain consists mainly of a high-altitude plateau, with some hills and mountains.[66] Lusaka is located on the plateau, in south-central Zambia at 15°25′S 28°17′E, with an altitude of 1,280 metres (4,200 ft).[67][68] It is located 472 kilometres (293 mi) north east of the tourism capital, Livingstone, and 362 kilometres (225 mi) from Kitwe on the Copperbelt, Zambia's second-largest city. Mpulungu, the most distant major Zambian town from Lusaka, lies 1,074 kilometres (667 mi) away on the shores of Lake Tanganyika.[69] The city of Lusaka is coterminous with Lusaka District, and is the capital of Lusaka Province, which is Zambia's smallest but most populated province.[70][71] Lusaka District borders Chilanga District to the west and south, Kafue District to the south-east and Chongwe District to the east, all in Lusaka Province. It also borders Chibombo District to the north.[70]

The geology of Lusaka is divided between uneven-depth folded and faulted schist in the north, and limestone with dolomitic marble in the south, to a depth of 120 metres (390 ft). These rocks yield more groundwater than the crystalline basement rock which is the most prevalent in Zambia. The limestone regions have formed underground karsts, into which surface water drains, causing a lack of major rivers and few streams.[72] The city lies on a drainage divide, with waters in the north east of the city draining into the Chongwe River, via the Ngwerere and Chalimbana streams, while the west and south are within the basin of the Kafue River. Both the Chongwe and the Kafue ultimately drain into the Zambezi River.[73] The soil is predominantly Leptosols in the schist region and Phaeozems on the dolomite. These non-clay soils result in reduced filtration of groundwater before it reaches aquifers.[74]

Cityscape

Lusaka's central business district (CBD) is located in the area surrounding Cairo Road, to the west of the Zambia Railways line from Livingstone to the Copperbelt. This is the historical site where the original colonial town was founded in the early 20th century. Cairo Road, a north–south multi-lane highway roughly four kilometres (2+1⁄2 mi) in length,[75] is the CBD's main artery, which features office buildings as well as shops, cafes and other retail businesses.[76][77] However, heavy vehicles (trucks) are not allowed on Cairo Road (they are advised to use Lumumba Road to bypass this thoroughfare to the west when travelling north and south). Four of the top five tallest buildings in Zambia are located on Cairo Road, including the tallest, the 90-metre (300 ft) 23-storey Findeco House.[78][lower-alpha 1] To the west of Cairo Road there are two major markets, the Central Market and New City Market.[75]

East of the CBD lies the government area, which including the State House and the various ministries, around Cathedral Hill and Ridgeway neighbourhoods.[83] East of there, along Independence Avenue, lies Woodlands, which is the principal residential area for Lusaka's rich elite, as well as wealthy expatriates.[77] The wealthy suburbs of Makeni, Ibex Hill and Rhodes Park are also situated in the east of the city.[76][83] Other suburbs include Kalingalinga, Kamwala, Kabwata, Olympia Park, Roma, Fairview and Northmead.[77] The majority of Lusaka residents, however, live in the unplanned shanty towns, which are predominantly in the west, south and north of the city.[84] These include Matero, Chilenje and Libala.[76]

Along Great East Road are three of the largest shopping malls in Zambia: Arcades shopping mall (with open-air storefronts), East Park shopping mall and Manda Hill shopping mall (enclosed shops), which was revamped and houses many most international stores and restaurants.[85] Overlooking Arcades is the Sun Share Tower on Katimamulilo Road near the Radisson Blu hotel. The 58-metre-high Tower was launched in 2017 by Sun Share Ltd.[86]

Monuments and national symbols in Lusaka include the National Museum, government buildings around the CBD, the African Freedom statue and a memorial to the victims of the 1993 Zambia national football team plane crash, located at the National Heroes Stadium.[87]

Climate

Primarily due to its high altitude, Lusaka features a humid subtropical climate (Cwa) according to Köppen climate classification. Its coldest month, July, has a monthly mean temperature of 14.9 °C (58.8 °F). Lusaka features hot summers and cool winters, with cold conditions mainly restricted to nights in June and July. The hottest month is October, which sees daily average high temperatures at around 32 °C (90 °F). There are three main seasons: a warm monsoon season between November and March, a dry winter between April and August, and a hot summer in September and October.

| Climate data for Lusaka | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 39.6 (103.3) |

36.4 (97.5) |

33.6 (92.5) |

33.0 (91.4) |

32.0 (89.6) |

29.9 (85.8) |

29.7 (85.5) |

33.5 (92.3) |

38.5 (101.3) |

37.2 (99.0) |

38.6 (101.5) |

33.9 (93.0) |

39.6 (103.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 27.4 (81.3) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.5 (81.5) |

27.1 (80.8) |

25.8 (78.4) |

23.8 (74.8) |

24.0 (75.2) |

26.5 (79.7) |

30.3 (86.5) |

31.7 (89.1) |

30.4 (86.7) |

27.7 (81.9) |

27.5 (81.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 21.5 (70.7) |

21.5 (70.7) |

21.1 (70.0) |

19.9 (67.8) |

17.4 (63.3) |

15.2 (59.4) |

14.9 (58.8) |

17.3 (63.1) |

21.3 (70.3) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.4 (74.1) |

21.7 (71.1) |

19.9 (67.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 17.6 (63.7) |

17.4 (63.3) |

16.4 (61.5) |

14.0 (57.2) |

10.7 (51.3) |

7.8 (46.0) |

7.2 (45.0) |

9.2 (48.6) |

12.9 (55.2) |

16.2 (61.2) |

17.4 (63.3) |

17.8 (64.0) |

13.7 (56.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 13.0 (55.4) |

12.9 (55.2) |

10.0 (50.0) |

8.0 (46.4) |

5.4 (41.7) |

0.2 (32.4) |

0.7 (33.3) |

2.8 (37.0) |

5.8 (42.4) |

9.0 (48.2) |

10.8 (51.4) |

10.4 (50.7) |

0.2 (32.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 245.4 (9.66) |

185.9 (7.32) |

95.0 (3.74) |

34.7 (1.37) |

3.1 (0.12) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.00) |

0.4 (0.02) |

1.7 (0.07) |

18.4 (0.72) |

89.3 (3.52) |

208.1 (8.19) |

882.1 (34.73) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 18 | 15 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 16 | 72 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 82.3 | 82.5 | 80.7 | 75.8 | 69.3 | 65.2 | 61.1 | 53.6 | 46.3 | 48.6 | 60.2 | 78.6 | 67.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 176.7 | 168.0 | 220.1 | 246.0 | 275.9 | 270.0 | 294.5 | 303.8 | 291.0 | 272.8 | 234.0 | 182.9 | 2,935.7 |

| Source: NOAA[88] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

As of the 2010 Zambian census, the population of Lusaka was 1,715,032, of whom 838,210 were male and 876,822 female.[89] This represented a 58 per cent increase since the 2000 census,[lower-alpha 2] and the city has continued to grow rapidly with an estimated population of 2,731,696 in 2020.[91] Although the area was historically on the boundary between the territory of the Soli and Lenje peoples,[12] modern Lusaka has no single dominant ethnic group, with all of Zambia's peoples represented.[61] This is a result of extensive migration from all areas of the country into the city, as well as the government's "One Zambia, One Nation" policy which encourages government employees to work across the country irrespective of their area of origin.[92] Although most of the population is African and of Bantu origin, there are also some non-Bantu long-term residents in Lusaka. This includes white people, many descendants of those who settled around the railway in colonial times and Gujarati-speaking Indians, whose numbers have increased since Zambian independence. Many of these non-African residents hold Zambian citizenship.[93]

Languages

As with the rest of Zambia, English is the official national language in Lusaka, and is used in education from the fifth grade in school, at the age of 11, through to university.[94][92] It is also the language used by large business, most newspapers and media, as well as the government.[92][93] The lingua franca in the city until the 1980s was Nyanja, brought by immigrants from Eastern Province. Since then, however, with increased migration from the Copperbelt, there has been growing use of Bemba among the city's residents.[61] The mixture of three languages has led to a hybrid language in Lusaka known as Town Nyanja. This is based on Nyanja, but incorporates vocabulary from English and Bemba as well as Nsenga.[92]

Government

As the national capital, Lusaka is the seat of the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government, epitomised by the presence of the National Assembly (parliament), the State House (office of the President), and the High Court. The Parliament is situated at the Parliament complex, which features a 15-story building. The city is also the capital of Lusaka Province, the smallest and most populous of the country's ten provinces, and forms an administrative district run by Lusaka City Council (namely Lusaka District). The city council is headed by the Mayor of Lusaka, with Chilando Chitangala the incumbent as of 2021. [95]

Education

Zambia's oldest and largest institution of learning is the University of Zambia which is based in Lusaka and was established in 1965 and officially opened to the general public (which included both local and international students) in July 1966. Other universities and colleges located in Lusaka include: University of Lusaka (UNILUS), Zambian Open University (ZAOU), Chainama Hills College, Evelyn Hone College of Applied Arts and Commerce, Zambia Centre for Accountancy Studies University (ZCASU), Natural Resources Development College (NRDC), National Institute of Public Administration (NIPA), Cavendish University, Lusaka Apex Medical University and DMI-St. Eugene University. Lusaka has some of the finest schools in Zambia, including the American International School of Lusaka, Rhodes Park School, the Lusaka International Community School, the French International School, the Italian international School, the Lusaka Islamic Cultural, and Educational Foundation (LICEF), the Chinese International School, Lusaka Russian Embassy School,[96] and Baobab College. Rhodes Park School is not an international school, though there is a large presence of Angolans, Nigerians, Congolese, South Africans, and Chinese. The children of late President Levy Mwanawasa, as well as the children of late Vice-president George Kunda, attended the Rhodes Park School. Other well-known schools located in Lusaka include Matero Boys' Secondary School (MaBoys), Parklands High School, Roma Girls' Secondary School, Munali Boys' and Girls' Secondary Schools, Chudleigh House School, Kabulonga Boys' and Girls' Secondary Schools, Lake Road PTA School, David Kaunda Technical School (DK), Ibex Hill School, Kamwala Secondary, Libala Secondary, Silverest Secondary School and St. Mary's Secondary School.

Places of worship

Among the places of worship, these are the predominant Christian churches and temples: the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Lusaka (Catholic Church), seated at the Child Jesus Cathedral; the Anglican Cathedral of the Holy Cross in Cathedral Hill; the Seventh-day Adventist (SDA); United Church in Zambia (World Communion of Reformed Churches); New Apostolic Church; Reformed Church in Zambia (World Communion of Reformed Churches); Baptist Union of Zambia (Baptist World Alliance); and the Assemblies of God.[97] The Jehovah’s Witnesses and LDS churches both have a few chapels and growing base of members. There are also several large mosques to serve the local Muslim community. Synagogues here are noticeably absent.

Culture

Attractions include Lusaka National Museum, the Political Museum, the Zintu Community Museum, the Freedom Statue, the Zambian National Assembly, the Agricultural Society Showgrounds (known for their annual agricultural show), the Moore Pottery Factory, the Lusaka Playhouse theatre, a cenotaph, Lusaka Golf Club, National Heroes Stadium, Woodlands Stadium, the Lusaka Central Sports Club, Kalimba Reptile Park, Mulungushi Conference Centre, Monkey Pools and the zoo, Pazuri and botanical gardens of the Munda Wanga Environmental Park.

Economy

Lusaka is the economic and financial hub of Zambia, serving as the country's main gateway to the rest of the world and largest business centre.[98] Although district-level GDP figures are not recorded in Zambia, on a provincial level Lusaka Province had the second-highest gross domestic product in Zambia in 2014, contributing 27.2 per cent of the national output, a figure narrowly below that of the resource-rich Copperbelt Province.[99]

In contrast to Zambia as a whole, in which agriculture and mining are the largest contributors, Lusaka's economy is dominated by the service sector, as well as wholesale and retail trade.[100] Major employment areas in the city include finance, insurance, real estate, transport, communications, energy, construction and manufacturing.[100] The headquarters of Zambian banks are located in the city, as is the Lusaka Stock Exchange, which launched in 1993.[98]

Retail

Lusaka is home to the largest and most numerous shopping centres in the country, including Manda Hill, Levy Junction, EastPark, Cosmopolitan, and the smaller but well-known Arcade Shopping Centre. It also has newly built shopping malls such as Lewanika shopping mall, Centro mall, Novare Pinnacle malls in Woodlands and along the Great North Road.

Infrastructure

Transport

Lusaka is home to Kenneth Kaunda International Airport (which is used for both civil and military operations). There is also Lusaka City Airport, which is used by the Zambian Air Force.

The city is served by the operating sections of the Cape to Cairo Railway, which connects it to Lubumbashi and Bulawayo. The international airport is connected to the railway line.

The city is crossed by Trans-African Highway 9 (TAH 9), which connects it to the cities of Harare and Lubumbashi, and by Trans-African Highway 4 (TAH 4), which connects it to Dodoma and Bulawayo.

Lusaka's city centre is at the crossroads of three major routes, namely the Great North Road (T2), Great East Road (T4) and Mongu Road (M9). The Great North Road connects north to Kabwe, Mpika and the republic of Tanzania (with branches linking to Ndola, Kitwe and DR Congo) and south to Choma, Livingstone and the republic of Zimbabwe. The Great East Road connects east to Chipata and the republic of Malawi (with a branch road linking to the republic of Mozambique). The Mongu Road connects west to Kaoma and Mongu (and could possibly become the main route to Angola via the Barotse Floodplain Causeway).

Intracity public transport is provided primarily by minibuses, but also includes larger buses and shared taxis on fixed routes.[101] Vehicles on most routes travel between specific parts of the city and the four terminals in the central business district (referred to as "Town"): Kulima Tower, City Market, Millennium and Lumumba.[102] There is no official map of public transport routes in Lusaka, but an initiative to create a user-generated content map was begun in 2014.[103] All public transport vehicles in Lusaka are operated by private operators.

Bus services within Lusaka neighbourhoods, the CBD, and towns surrounding Lusaka, such as Siavonga and Chirundu, use the Lusaka City Market Bus station, Inter-city Bus Terminus, Millennium Bus Station, and Kulima Tower Station.

Healthcare

Zambia has five national tertiary hospitals, of which two are located in Lusaka.[104] The larger of these is the University Teaching Hospital (UTH), which has 1655 beds and space for 250 babies.[105] UTH serves as the highest-level hospital for a population of around 2 million people, as well as taking referrals from other health institutions around the country.[106] It serves as Zambia's principal centre for the training of medical professionals including doctors and nurses, the latter in a specialist Nursing School within the UTH complex.[105] Lusaka's second tertiary hospital is the Chainama Hills,[104] which has 210 authorised beds and 167 unofficial "floor beds", is Zambia's only psychiatric hospital.[107] The Chainama Hills site also serves as the training centre for clinical officers in Zambia.[105]

Overall, Lusaka had a total of 34 health centres run by the government in 2007, as well as 134 run by the private sector.[108] The government has sought to decentralise provision from the Ministry of Health and Lusaka's day-to-day healthcare is provided by the provincial-level Lusaka District Health Management Team and the citywide Lusaka District Health Management Team.[109][110] The priorities for the district, which in 2007 accounted for 90 per cent of the city's health cases, include malaria, reproductive health, child health, tuberculosis, leprosy, HIV and other sexually-transmitted diseases, environmental health, mental health, and medicine supply.[111] The Zambian government has a long-term aim of providing universal health care (UHC) for all Zambians. As of 2017, it had notionally achieved free primary health provision for all, but availability was often limited due to capacity constraints. To address this, the ministry of health partnered with JICA to on a project to take the necessary steps to achieve genuine UHC.[112]

Sport

The largest sports venue in Lusaka is National Heroes Stadium, which was built with assistance and financing from China. Named in honour of those who died in the 1993 Zambia national football team plane crash,[113] it opened in 2014 and has a capacity of 60,000.[114] The stadium is used to host home matches of the Zambian national football team,[115] and was one of two host stadia for the 2017 Africa U-20 Cup of Nations in Zambia, alongside the Levy Mwanawasa Stadium in Ndola.[116] That tournament was won by Zambia at the National Heroes Stadium, with a 2–0 win against Senegal.[117] The stadium is also used for athletics events, including the 2021 All Comers Tournament, which served as a qualification event for the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo.[118]

As of 2021, six of the eighteen teams in the association football Zambia Super League are based in Lusaka.[119] The city's most successful club is Zanaco F.C., which has won seven national titles, the most recent in 2016.[120] Zanaco were founded in 1978 as the team of the Zambia National Commercial Bank, and have played in the top division since 1989.[121] Green Buffaloes are another successful team in Lusaka, with six titles, although the most recent was in 1981.[120] In addition to the National Heroes stadium, Lusaka's football teams play home games at the Nkoloma Stadium, Sunset Stadium and Woodlands Stadium.[122]

Lusaka is home to the basketball team UNZA Pacers, which is part of the University of Zambia.

International relations

Lusaka is twinned with:

Dushanbe, Tajikistan, since 1966

Dushanbe, Tajikistan, since 1966 Beirut, Lebanon, (2018)

Beirut, Lebanon, (2018) Udon Thani, Thailand, (2015)

Udon Thani, Thailand, (2015) Los Angeles, United States, since 1968

Los Angeles, United States, since 1968 Izhevsk, Russia

Izhevsk, Russia

Notable people

The rugby union players Corné Krige and George Gregan, who respectively captained the South African and Australian teams in both the 2002 and 2003 Tri Nations Series, were coincidentally born in the same hospital in Lusaka.[123][124][125]

The former Zimbabwe cricketer Henry Olonga was also born in Lusaka. He was the first black cricketer – and the youngest person – to play for Zimbabwe.[126]

Lusaka is the hometown and place of residence of Joseph and Luka Banda, the first conjoined twins to be successfully separated by Ben Carson and his team.[127]

Former professional footballer Enock Mwepu was born in Lusaka.

See also

- Southern Africa Freedom Trail

- Kafue Railway Bridge (railway bridge from Livingstone to Lusaka)

- Komboni

Notes

References

- City of Lusaka Website Archived 20 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Airport altitude, http://climexp.knmi.nl/ Retrieved 7 March 2015

- Central Statistical Office. "Population and Demography of Zambia". Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- Central Statistical Office. "Population and Demographic Projections". Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- "Zambia". International Telecommunication Union. 14 November 2019. Archived from the original on 15 September 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- "Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- "Africa's fastest-growing cities". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- "Zambia Population 2020 (Live)". worldpopulationreview.com. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- Myers 2016, p. 48.

- Fagan 1961, p. 228.

- Roberts, Andrew D. (15 April 2021). "Zambia – People". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- Tribal and linguistic map of Zambia (Map) – via African Studies Centre Leiden.

- Mulenga 2003, p. 2.

- Woodhouse, Christopher Montague. "Cecil Rhodes | Biography, Significance, & Facts". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- Fox 1920, p. 100.

- Mulenga 2003, pp. 1–2.

- "Barotziland North-Western Rhodesia Order in Council, 1899" (PDF). Government of the United Kingdom. 28 November 1899. Retrieved 12 June 2021 – via Barotseland Post.

- Hunt 1959, pp. 9 &, 12.

- "Northern Rhodesia Order in Council, 1911" (PDF). Government of the United Kingdom. 17 August 1911. Retrieved 12 June 2021 – via Barotse National Freedom Alliance.

- Lunn 1992, pp. 240–241.

- Katzenellenbogen 1974, p. 64.

- Winchester 1935a, pp. 867–868.

- Winchester 1935b, pp. 869–874.

- Home 2013, p. 4.

- Clough 1924, pp. 281–282.

- Home 2013, pp. 4–5.

- Home 2013, p. 6.

- Ranger 1980, p. 351.

- Home 2013, p. 7.

- "Northern Rhodesia - Tuesday 19 April 1932". Hansard. Parliament of the United Kingdom. 19 April 1932. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- Home 2013, p. 8.

- Home 2013, p. 9.

- Hansen 1982, p. 122.

- Home 2013, pp. 9–10.

- Home 2013, p. 10.

- Home 2013, p. 21.

- Home 2013, p. 2.

- "Lusaka will be Rhodesia capital". Spokane Chronicle. 3 April 1934. Retrieved 15 June 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Home 2013, p. 11.

- Home 2013, p. 1.

- Home 2013, p. 14.

- Home 2013, p. 16.

- "Modern City New African Colony Seat". The Ithaca Journal. 4 June 1935. p. 9 – via Newspapers.com.

- Home 2013, p. 15.

- "Politics – and Other Subjects: Rhodesia". The Windsor Star. 2 February 1938. p. 4. Retrieved 18 June 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Roberts 1982, p. 352.

- Mulenga 2003, p. 3.

- Roberts 1982, p. 353.

- Hansen 1982, pp. 122–123.

- Hansen 1982, p. 123.

- Kalinga, WOwen Jato. "Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- Hansen 1982, p. 124.

- Roberts, Andrew D. (15 April 2021). "Zambia – Colonial Rule". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- Home 2013, p. 18.

- Hansen 1982, p. 125.

- Wade, Evan (3 November 2014). "Lusaka, Zambia (1913–)". Blackpast.org. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- Ingham, Kenneth. "Tanzania – Independence". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- Chongo 2016, p. 13.

- Roberts, Andrew D. (15 April 2021). "Zambia – Zambia under Kaunda". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- Frischkorn 2015, pp. 209–210.

- Mulenga 2003, p. 4.

- "How to stop Zambia from turning into Zimbabwe". 12 November 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- Wragg & Lim 2014, p. 262.

- "The Urban and Regional Planning: Act Number 3 of 2015". National Assembly of Zambia. 14 August 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- Chigudu 2021, pp. 6–7.

- Grönwall, Mulenga & McGranahan 2010, p. 47.

- Pletcher, Kenneth. "Lusaka". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- CIA 2007, p. 684.

- McIntyre 2016, p. 68.

- "About Lusaka". Lusaka City Council. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- "Lusaka Provincial Administration » About Lusaka". Provincial Administration, Lusaka Province. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- Grönwall, Mulenga & McGranahan 2010, p. 49.

- Lusaka City Council & Environmental Council of Zambia 2008, p. 3.

- Grönwall, Mulenga & McGranahan 2010, p. 50.

- McIntyre 2016, p. 119.

- Hamonga 1996, p. 61.

- Auzias & Labourdette 2017, p. 86.

- "Zambia's tallest buildings - Top 20". Emporis. STR Germany. Archived from the original on 11 May 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- "Findeco House". Emporis. STR Germany. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- "Society House". Emporis. STR Germany. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- "Indeco House". Emporis. STR Germany. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- "ZANACO House". Emporis. STR Germany. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- "Lusaka" (Map). OpenStreetMap. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- Mulenga 2003, p. 7.

- Mwakikagile, Godfrey (2010). Zambia: Life in an African Country. New Africa Press. p. 161. ISBN 9789987160112. Archived from the original on 13 November 2017.

- "Sun Share LTD to Launch tower building at the Penthouse Party". Lusaka Times. 13 December 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- Myers & Subulwa 2018, p. 124.

- "LUSAKA INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT Climate Normals 1961-1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- "2010 Census of Population and Housing". 11. Central Statistical Office (Zambia). November 2012: 2. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0141689.s006.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "2000 Census of Population and Housing: Summary Report". Central Statistical Office (Zambia). November 2003. p. 10.

- Mulenga et al. 2021, p. e777.

- Mutunda 2007, p. 2.

- Roberts, Andrew D. (15 April 2021). "Zambia – People". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- Sikombe, Kathy (14 February 2013). "Zambia grapples with language challenge". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- "Chilando Chitangala Was Duly Elected As Lusaka Mayor ~". 21 September 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- "Russian Embassy School, Lusaka, Zambia". bizpages.org. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- Britannica, Zambia, britannica.com, USA, accessed on 7 July 2019

- United Nations 2011, p. 19.

- Central Statistical Office 2017, p. 8.

- Mulenga 2016, p. 5.

- "Can You Do It? Using Public Transportation in Lusaka Zambia". Travel Wanderings. 5 September 2013. Archived from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- "Making Public Transport in Lusaka City More Efficient and Effective" (PDF). Zambia Institute for Policy Analysis & Research. December 2013. Archived from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- "And We Have a Map!". Lusaka Public Transport Map: A User-Generated Mapping Project. 10 March 2014. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- Tropical Health and Education Trust; Ministry of Health (Zambia) (2007). "Main Report: Mapping of Health Links in the Zambian Health Services and Associated Academic Institutions under the Ministry of Health" (PDF). Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- "Lusaka (Zambia)". The British Association of Urological Surgeons. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- "University Teaching Hospital, Lusaka". Zambia UK Health Workforce Alliance. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- Mwape et al. 2010, p. 2.

- United Nations Human Settlements Programme, p. 12.

- United Nations Human Settlements Programme 2007, p. 12.

- Mandyata, Olowski & Mutale 2017, p. 3.

- Mandyata, Olowski & Mutale 2017, p. 4.

- Turner, Claire (7 August 2017). "Universal Health Coverage: what can the Republic of Zambia learn from Thailand?". iDSI. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- Muchimba 2015, p. 213.

- Gondwe, Kennedy (12 January 2014). "Zambia finish building new stadium". BBC Sport. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- "National Heroes Stadium and Levy Mwanawasa get CAF approval to host World Cup qualifiers". ZamFoot. 4 May 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- Gondwe, Kennedy (25 February 2017). "Zambia prepares for start of African U-20s". BBC Sport. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- Gondwe, Kennedy (12 March 2017). "Zambia crowned U-20 champions on home soil". BBC Sport. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- "4 athletes in Zambia for Olympics qualifiers | The Nation Online". The Nation Online. 4 March 2021. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- Kalumiana, Kalumiana (27 May 2021). "Zambia 2020/21". RSSSF. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- Schöggl, Hans (5 November 2020). "Zambia Champions". RSSSF. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- Zanaco F.C. "Zanaco FC - Who We Are". zanacofc.co.zm. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- "Zambian Super League Fixtures & Results: 27th June 2021 – 3rd July 2021". ESPN. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- "George Gregan - Player Profile". Georgegregan.com. Archived from the original on 9 November 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- "Captain Courageous: Corné Krige" Archived 26 July 2011 at Wikiwix, TheGoal.com, retrieved 26 June 2006.

- "Rugby Union World Cup Special Reports: South Africa" Archived 19 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 6 October 2003.

- "Henry Olonga- a short biography". ESPNcricinfo. 18 September 1999. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- Terris, Ben; Kirchner, Stephanie (13 November 2015). "The Story of the Surgery that made Ben Carson Famous". The Washington Post. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

Bibliography

- Auzias, Dominique; Labourdette, Jean-Paul (2017). Zambie – Escapade au Malawi (in French). Petit Futé. ISBN 979-1-03314-501-1.

- Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) (2007). The World Factbook 2007. Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-16-078580-1.

- Central Statistical Office, Republic of Zambia (2017). "Research Paper on Provincial Gross Domestic Product" (PDF). Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- Central Statistical Office, Republic of Zambia (2018). "Zambia in Figures" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 July 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- Chigudu, Andrew (2021). "The Changing Institutional and Legislative Planning Framework of Zambia and Zimbabwe: Nuances for Urban Development". Land Use Policy. 100: 104941. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104941.

- Chongo, Clarence (2016). "A Good Measure of Sacrifice: Aspects of Zambia's Contribution to the Liberation Wars in Southern Africa, 1964-1975". Zambia Social Science Journal. 6 (1). Article 3.

- Clough, G.D. (1924). "The Constitutional Changes in Northern Rhodesia and Matters Incidental to the Transition". Journal of Comparative Legislation and International Law. 3. Cambridge University Press on behalf of the British Institute of International and Comparative Law. 6 (4): 278–282. JSTOR 752781.

- Fagan, B.M. (1961). "A Collection of Nineteenth-Century Soli Ironwork from the Lusaka Area of Northern Rhodesia". The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 91 (2): 228–250. doi:10.2307/2844415. JSTOR 2844415.

- Fox, H. Wilson (February 1920). "The Cape-to-Cairo Railway and Train Ferries". The Geographical Journal. The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers). 55 (2): 73–101. doi:10.2307/1781582. JSTOR 1781582.

- Frischkorn, Rebecca (2015). "Political Economy of Control: Urban Refugees and the Regulation of Space in Lusaka, Zambia". Economic Anthropology. 2: 205–223. doi:10.1002/sea2.12025.

- Grönwall, Jenny T.; Mulenga, Martin; McGranahan, Gordon (2010). Groundwater, self-supply and poor urban dwellers: A review with case studies of Bangalore and Lusaka. International Institute for Environment and Development.

- Hansen, Karen Tranberg (1982). "Lusaka's Squatters: Past and Present". African Studies Review. Cambridge University Press. 25 (2–3): 117–136. doi:10.2307/524213. JSTOR 524213. S2CID 145505993.

- Hamonga, Paul (1996). "Lusaka". BBC Focus on Africa. BBC African Service. 7.

- Hunt, B.L. (1959). "Kalomo–Livingstone in 1907". Northern Rhodesia Journal. Northern Rhodesian Government Printer. 4 (1).

- Home, Robert, ed. (2013). Lusaka: The New Capital of Northern Rhodesia. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-82868-0.

- Katzenellenbogen, Simon (January 1974). "Zambia and Rhodesia: Prisoners of the Past: A Note on the History of Railway Politics in Central Africa". African Affairs. Oxford University Press on behalf of The Royal African Society. 73 (290): 63–66. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a096455. JSTOR 720981.

- Lunn, Jon (1992). "The Political Economy of Primary Railway Construction in the Rhodesias, 1890-1911". The Journal of African History. Cambridge University Press. 33 (2): 239–254. doi:10.1017/S0021853700032229. JSTOR 183000. S2CID 162300534.

- Lusaka City Council; Environmental Council of Zambia (2008). Lusaka City State of Environment Report. ISBN 978-9982-861-01-4.

- McIntyre, Chris (2016). Zambia – The Bradt Travel Guide (6th ed.). Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-78477-012-9.

- Muchimba, Jerry (2015). Godfrey 'Ucar' Chitalu. Troubador Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-78462-220-6.

- Mulenga, Chileshe L. (2003). "Urban slums reports: The case of Lusaka, Zambia" (PDF). Understanding Slums: Case Studies for the Global Report on Human Settlements. Institute of Economic and Social Research, University of Zambia. Retrieved 12 June 2021 – via University College London.

- Mulenga, Chileshe L. (2016). The State of Food Insecurity in Lusaka, Zambia: Issue 19 of Urban food security series. Southern African Migration Programme. ISBN 978-1-92059-710-8.

- Mulenga, Lloyd B.; Hines, Jonas Z.; Fwoloshi, Sombo; Chirwa, Lameck; Siwingwa, Mpanji; Yingst, Samuel; Wolkon, Adam; Barradas, Danielle T.; Favaloro, Jennifer; Zulu, James E.; Banda, Dabwitso; Nikoi, Kotey I.; Kampamba, Davies; Banda, Ngawo; Chilopa, Batista; Hanunka, Brave; Stevens Jr., Thomas L.; Shibemba, Aaron; Mwale, Consity; Sivile, Suilanji; Zyambo, Khozya D.; Makupe, Alex; Kapina, Muzala; Mweemba, Aggrey; Sinyange, Nyambe; Kapata, Nathan; Zulu, Paul M.; Chanda, Duncan; Mupeta, Francis; Chilufya, Chitalu; Mukonka, Victor; Agolory, Simon; Malama, Kennedy (2021). "Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in six districts in Zambia in July, 2020: a cross-sectional cluster sample survey". The Lancet Global Health. 9 (6): e773–e781. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00053-X. PMC 8382844. PMID 33711262.

- Mandyata, Chomba Brian; Olowski, Linda Kampata; Mutale, Wilbroad (December 2017). "Challenges of implementing the integrated disease surveillance and response strategy in Zambia: a health worker perspective". BMC Public Health. 17 (1): 746. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4791-9. PMC 5615443. PMID 28950834.

- Mutunda, Sylvester (2007). Lê, Thao; Lê, Quynh (eds.). "Language Behavior in Lusaka: The Use of Nyanja Slang". The International Journal of Language Society and Culture. ISSN 1327-774X.

- Mwape, Lonia; Sikwese, Alice; Kapungwe, Augustus; Mwanza, Jason; Flisher, Alan; Lund, Crick; Cooper, Sara (2010). "Integrating mental health into primary health care in Zambia: a care provider's perspective". International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 4 (1): 21. doi:10.1186/1752-4458-4-21. PMC 2919445. PMID 20653981.

- Myers, Garth A. (2016). "Remaking the Edges: Surveillance and Flows in Sub-Saharan Africa's New Suburbs". In Loeb, Carolyn; Luescher, Andreas (eds.). The Design of Frontier Spaces: Control and Ambiguity. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-31703-607-4.

- Myers, Garth A.; Subulwa, Angela G. (2018). "The Cityscapes of Lusaka and Mongu: Narrating National Symbolism in Zambia". In Diener, Alexander C.; Hagen, Joshua (eds.). The City as Power: Urban Space, Place, and National Identity. ISBN 9781538118276.

- Ranger, Terence (July 1980). "Making Northern Rhodesia Imperial: Variations on a Royal Theme, 1924-1938". African Affairs. Oxford University Press on behalf of The Royal African Society. 79 (316): 349–373. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a097229. JSTOR 722045.

- Roberts, Andrew D. (1982). "Notes towards a Financial History of Copper Mining in Northern Rhodesia". Canadian Journal of African Studies. Taylor & Francis, Ltd. on behalf of the Canadian Association of African Studies. 16 (2): 347–359. doi:10.2307/484302. JSTOR 484302.

- United Nations (2011). "An Investment Guide to Zambia: Opportunities and Conditions" (PDF). Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- Winchester, Clarence, ed. (2 August 1935). "Progress in Rhodesia: An important railway system in the heart of Africa". Railway Wonders of the World. Amalgamated Press. 27.

- Winchester, Clarence, ed. (9 August 1935). "Progress in Rhodesia: An important railway system in the heart of Africa". Railway Wonders of the World. Amalgamated Press. 28.

- Wragg, Emma; Lim, Regina (2014). "Urban visions from Lusaka, Zambia". Habitat International. 46: 260–270. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.10.005.

External links

Lusaka travel guide from Wikivoyage

Lusaka travel guide from Wikivoyage- Lusaka City Council

- Zambia Tourism page on Lusaka