Ménière's disease

Ménière's disease (MD) is a disease of the inner ear that is characterized by potentially severe and incapacitating episodes of vertigo, tinnitus, hearing loss, and a feeling of fullness in the ear.[3][4] Typically, only one ear is affected initially, but over time, both ears may become involved.[3] Episodes generally last from 20 minutes to a few hours.[5] The time between episodes varies.[3] The hearing loss and ringing in the ears can become constant over time.[4]

| Ménière's disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Ménière's syndrome, idiopathic endolymphatic hydrops[1] |

| |

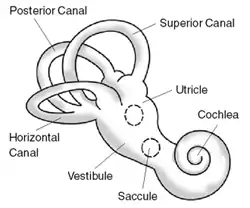

| Diagram of the inner ear | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Otolaryngology |

| Symptoms | Feeling like the world is spinning, ringing in the ears, hearing loss, fullness in the ear[3][4] |

| Usual onset | 40s–60s[3] |

| Duration | 20 minutes to few hours per episode[5] |

| Causes | Unknown[3] |

| Risk factors | Family history[4] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, hearing test[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Vestibular migraine, transient ischemic attack[1] |

| Treatment | Low-salt diet, diuretics, corticosteroids, counselling[3][4] |

| Prognosis | After ~10 years hearing loss and chronic ringing[5] |

| Frequency | 0.3–1.9 per 1,000[1] |

The cause of Ménière's disease is unclear, but likely involves both genetic and environmental factors.[1][3] A number of theories exist for why it occurs, including constrictions in blood vessels, viral infections, and autoimmune reactions.[3] About 10% of cases run in families.[4] Symptoms are believed to occur as the result of increased fluid buildup in the labyrinth of the inner ear.[3] Diagnosis is based on the symptoms and a hearing test.[3] Other conditions that may produce similar symptoms include vestibular migraine and transient ischemic attack.[1]

No cure is known.[3] Attacks are often treated with medications to help with the nausea and anxiety.[4] Measures to prevent attacks are overall poorly supported by the evidence.[4] A low-salt diet, diuretics, and corticosteroids may be tried.[4] Physical therapy may help with balance and counselling may help with anxiety.[3][4] Injections into the ear or surgery may also be tried if other measures are not effective, but are associated with risks.[3][5] The use of tympanostomy tubes, while popular, is not supported.[5]

Ménière's disease was first identified in the early 1800s by Prosper Ménière.[5] It affects between 0.3 and 1.9 per 1,000 people.[1] It most often starts in people 40 to 60 years old.[3][6] Females are more commonly affected than males.[1] After 5 to 15 years of symptoms, the episodes of the world spinning sometimes stop and the person is left with loss of balance, poor hearing in the affected ear, and ringing or other sounds in the affected ear or ears.[5]

Signs and symptoms

Ménière's is characterized by recurrent episodes of vertigo, fluctuating hearing loss, and tinnitus; episodes may be preceded by a headache and a feeling of fullness in the ears.[4] People may also experience additional symptoms related to irregular reactions of the autonomic nervous system. These symptoms are not symptoms of Meniere's disease per se, but rather are side effects resulting from failure of the organ of hearing and balance, and include nausea, vomiting, and sweating, which are typically symptoms of vertigo, and not of Ménière's.[1] This includes a sensation of being pushed sharply to the floor from behind.[5] Sudden falls without loss of consciousness (drop attacks) may be experienced by some people.[1]

Causes

The cause of Ménière's disease is unclear, but likely involves both genetic and environmental factors.[1][3][7] A number of theories exist including constrictions in blood vessels, viral infections, and autoimmune reactions.[3]

Mechanism

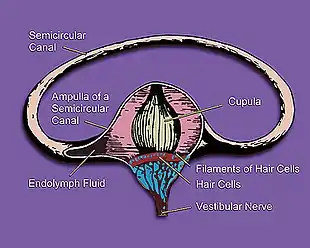

The initial triggers of Ménière's disease are not fully understood, with a variety of potential inflammatory causes that lead to endolymphatic hydrops (EH), a distension of the endolymphatic spaces in the inner ear. EH, in turn, is strongly associated with developing MD,[1] but not everyone with EH develops MD: "The relationship between endolymphatic hydrops and Meniere's disease is not a simple, ideal correlation."[8]

Additionally, in fully developed MD, the balance system (vestibular system) and the hearing system (cochlea) of the inner ear are affected, but some cases occur where EH affects only one of the two systems enough to cause symptoms. The corresponding subtypes of MD are called vestibular MD, showing symptoms of vertigo, and cochlear MD, showing symptoms of hearing loss and tinnitus.[9][10][11][12]

The mechanism of MD is not fully explained by EH, but fully developed EH may mechanically and chemically interfere with the sensory cells for balance and hearing, which can lead to temporary dysfunction and even to death of the sensory cells, which in turn can cause the typical symptoms of MD – vertigo, hearing loss, and tinnitus.[8][10]

Diagnosis

The diagnostic criteria as of 2015 define definite MD and probable MD as:[1][4]

Definite

- Two or more spontaneous episodes of vertigo, each lasting 20 minutes to 12 hours

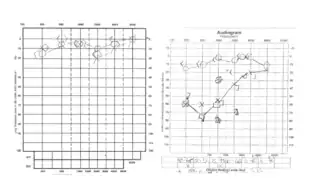

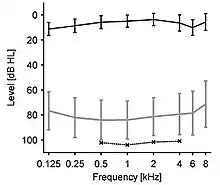

- Audiometrically documented low- to medium-frequency sensorineural hearing loss in the affected ear on at least one occasion before, during, or after one of the episodes of vertigo

- Fluctuating aural symptoms (hearing, tinnitus, or fullness) in the affected ear

- Not better accounted for by another vestibular diagnosis

Probable

- Two or more episodes of vertigo or dizziness, each lasting 20 minutes to 24 hours

- Fluctuating aural symptoms (hearing, tinnitus, or fullness) in the reported ear

- Not better accounted for by another vestibular diagnosis

A common and important symptom of MD is hypersensitivity to sounds.[14] This hypersensitivity is easily diagnosed by measuring the loudness discomfort levels (LDLs).[15]

Symptoms of MD overlap with migraine-associated vertigo (MAV) in many ways, but when hearing loss develops in MAV, it is usually in both ears, and this is rare in MD, and hearing loss generally does not progress in MAV as it does in MD.[1]

People who have had a transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke can present with symptoms similar to MD, and in people at risk magnetic resonance imaging should be conducted to exclude TIA or stroke.[1]

Other vestibular conditions that should be excluded include vestibular paroxysmia, recurrent unilateral vestibulopathy, vestibular schwannoma, or a tumor of the endolymphatic sac.[1]

Management

No cure for Ménière's disease is known, but medications, diet, physical therapy, and counseling, and some surgical approaches can be used to manage it.[4]

Medications

During MD episodes, medications to reduce nausea are used, as are drugs to reduce the anxiety caused by vertigo.[4][16] For longer-term treatment to stop progression, the evidence base is weak for all treatments.[4] Although a causal relation between allergy and Ménière's disease is uncertain, medication to control allergies may be helpful.[17] To assist with vertigo and balance problems, glycopyrrolate has been found to be a useful vestibular suppressant in patients with Meniere's disease.[18]

Diuretics, such as the thiazide-like diuretic chlortalidone, are widely used to manage MD on the theory that it reduces fluid buildup (pressure) in the ear.[19] Based on evidence from multiple but small clinical trials, diuretics appear to be useful for reducing the frequency of episodes of dizziness but do not seem to prevent hearing loss.[20][21]

In cases where hearing loss and continuing severe episodes of vertigo occur, a chemical labyrinthectomy, in which a medication such as gentamicin is injected into the middle ear and kills parts of the vestibular apparatus, may be prescribed.[4][22][23] This treatment has the risk of worsening hearing loss.[22]

Diet

People with MD are often advised to reduce their sodium intake.[16][24] Reducing salt intake, however, has not been well studied.[24]Based on the assumption that MD is similar in nature to a migraine, some advise eliminating "migraine triggers" such as caffeine, but the evidence for this is weak.[16] There is no high-quality evidence that changing diet by restricting salt, caffeine or alcohol improves symptoms.[25]

Physical therapy

While use of physical therapy early after the onset of MD is probably not useful due to the fluctuating disease course, physical therapy to help retraining of the balance system appears to be useful to reduce both subjective and objective deficits in balance over the longer term.[4][26]

Counseling

The psychological distress caused by the vertigo and hearing loss may worsen the condition in some people.[27] Counseling may be useful to manage the distress,[4] as may education and relaxation techniques.[28]

Surgery

If symptoms do not improve with typical treatment, surgery may be considered.[4] Surgery to decompress the endolymphatic sac is one option. A systematic review in 2015 found that three methods of decompression have been used – simple decompression, insertion of a shunt, and removal of the sac.[29] It found some evidence that all three methods were useful for reducing dizziness, but that the level of evidence was low, as trials were not blinded nor were placebo controls used.[29]

Another 2015 review found that, on autopsy, shunts used in these surgeries often turn out to be displaced or misplaced, and recommended their use only in cases where the condition is uncontrolled and affecting both ears.[16] A systematic review from 2014 found that in at least 75% of people, EL sac decompression was effective at controlling vertigo in the short term (>1 year of follow-up) and long term (>24 months).[30]

An estimated 30% of people with MD have Eustachian tube dysfunction.[31] While a 2005 review found tentative evidence of benefit from tympanostomy tubes for improvement in the unsteadiness associated with the disease,[31] a 2014 review concluded that their use is not supported.[5]

Destructive surgeries are irreversible and involve removing entire functionality of most, if not all, of the affected ear; as of 2013, almost no evidence existed with which to judge whether these surgeries are effective.[32] The inner ear itself can be surgically removed via labyrinthectomy, although hearing is always completely lost in the affected ear with this operation.[32] The surgeon can also cut the nerve to the balance portion of the inner ear in a vestibular neurectomy. The hearing is often mostly preserved; however, the surgery involves cutting open into the lining of the brain, and a hospital stay of a few days for monitoring is required.[32]

Poorly supported

- As of 2014, betahistine is often used as it is inexpensive and safe;[5] but evidence does not justify its use in MD.[33][34]

- Transtympanic micropressure pulses were investigated in two systematic reviews. Neither found evidence to justify this technique.[35][36]

- Intratympanic steroids were investigated in three systematic reviews. The data were found to be insufficient to decide if this therapy has positive effects.[37][38][39]

- Evidence does not support the use of alternative medicine such as acupuncture or herbal supplements.[3]

Prognosis

Ménière's disease usually starts confined to one ear; it extends to both ears in about 30% of cases.[5] People may start out with only one symptom, but in MD all three appear with time.[5] Hearing loss usually fluctuates in the beginning stages and becomes more permanent in later stages. MD has a course of 5–15 years, and people generally end up with mild disequilibrium, tinnitus, and moderate hearing loss in one ear.[5]

Epidemiology

From 3 to 11% of diagnosed dizziness in neuro-otological clinics are due to MD.[40] The annual incidence rate is estimated to be about 15 cases per 100,000 people and the prevalence rate is about 218 per 100,000, and around 15% of people with Meniere's disease are older than 65.[40] In around 9% of cases, a relative also had MD, indicating a genetic predisposition in some cases.[4]

The odds of MD are greater for people of white ethnicity, with severe obesity, and women.[1] Several conditions are often comorbid with MD, including arthritis, psoriasis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, irritable bowel syndrome, and migraine.[1]

History

The condition is named after the French physician Prosper Menière, who in an 1861 article described the main symptoms and was the first to suggest a single disorder for all of the symptoms, in the combined organ of balance and hearing in the inner ear.[41][42]

The American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium set criteria for diagnosing MD, as well as defining two subcategories – cochlear (without vertigo) and vestibular (without deafness).[43]

In 1972, the academy defined criteria for diagnosing MD as:[43]

- Fluctuating, progressive, sensorineural deafness

- Episodic, characteristic definitive spells of vertigo lasting 20 minutes to 24 hours with no unconsciousness, vestibular nystagmus always present.

- Tinnitus (ringing in the ears, from mild to severe) is accompanied often by ear pain and a feeling of fullness in the affected ear; usually, the tinnitus is more severe before a spell of vertigo and lessens after the vertigo attack.

- Attacks are characterized by periods of remission and exacerbation.

In 1985, this list changed to alter wording, such as changing "deafness" to "hearing loss associated with tinnitus, characteristically of low frequencies" and requiring more than one attack of vertigo to diagnose.[43] Finally in 1995, the list was again altered to allow for degrees of the disease:[43]

- Certain – Definite disease with histopathological confirmation

- Definite – Requires two or more definitive episodes of vertigo with hearing loss plus tinnitus and/or aural fullness

- Probable – Only one definitive episode of vertigo and the other symptoms and signs

- Possible – Definitive vertigo with no associated hearing loss

In 2015, the International Classification for Vestibular Disorders Committee of the Barany Society published consensus diagnostic criteria in collaboration with the American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, the European Academy of Otology and Neurootology, the Japan Society for Equilibrium Research, and the Korean Balance Society.[1][4]

References

- Lopez-Escamez, Jose A.; Carey, John; Chung, Won-Ho; et al. (2015). "Diagnostic criteria for Menière's disease". Journal of Vestibular Research: Equilibrium & Orientation. 25 (1): 1–7. doi:10.3233/VES-150549. ISSN 1878-6464. PMID 25882471.

- Dictionary.com Unabridged Archived 3 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine (v 1.1). Random House, Inc. Accessed on 9 September 2008

- "Ménière's Disease". NIDCD. 1 June 2016. Archived from the original on 27 July 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- Seemungal, Barry; Kaski, Diego; Lopez-Escamez, Jose Antonio (August 2015). "Early Diagnosis and Management of Acute Vertigo from Vestibular Migraine and Ménière's Disease". Neurologic Clinics. 33 (3): 619–628, ix. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2015.04.008. ISSN 1557-9875. PMID 26231275.

- Harcourt J, Barraclough K, Bronstein AM (2014). "Meniere's disease". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 349: g6544. doi:10.1136/bmj.g6544. PMID 25391837. S2CID 5099437.

- Phillips, John S.; Westerberg, Brian (6 July 2011). "Intratympanic steroids for Ménière's disease or syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD008514. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008514.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 21735432.

- Phillips, John S.; Westerberg, Brian (6 July 2011). "Intratympanic steroids for Ménière's disease or syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD008514. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008514.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 21735432.

- Salt AN, Plontke SK (2010). "Endolymphatic hydrops: pathophysiology and experimental models". Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America. 43 (5): 971–83. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2010.05.007. PMC 2923478. PMID 20713237.

- "Ménière's Disease". Nidcd.nih.gov (June 1, 2016 ed.). US: National Institutes of Health (Publication No. 10–3404). July 2010. Archived from the original on 27 July 2016.

- Gürkov R, Pyykö I, Zou J, Kentala E (2016). "What is Menière's disease? A contemporary re-evaluation of endolymphatic hydrops". Journal of Neurology. 263 Suppl 1: 71–81. doi:10.1007/s00415-015-7930-1. PMC 4833790. PMID 27083887.

- Naganawa S, Nakashima T (2014). "Visualization of endolymphatic hydrops with MR imaging in patients with Ménière's disease and related pathologies: current status of its methods and clinical significance". Japanese Journal of Radiology. 32 (4): 191–204. doi:10.1007/s11604-014-0290-4. PMID 24500139.

- Mom T, Pavier Y, Giraudet F, Gilain L, Avan P (2015). "Measurement of endolymphatic pressure". European Annals of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Diseases. 132 (2): 81–4. doi:10.1016/j.anorl.2014.05.004. PMID 25467202.

- Sheldrake J, Diehl PU, Schaette R (2015). "Audiometric characteristics of hyperacusis patients". Frontiers in Neurology. 6: 105. doi:10.3389/fneur.2015.00105. PMC 4432660. PMID 26029161.

- Chi, John J.; Ruckenstein, Michael J. (2010). "Chapter 6: Clinical Presentation of Ménière's disease". In Ruckenstein, Michael (ed.). Ménière's disease: evidence and outcomes. San Diego, California Abingdon, England: Plural Publishing, Inc. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-59756-620-9.

- Tyler RS, Pienkowski M, Roncancio ER, et al. (2014). "A review of hyperacusis and future directions: part I. Definitions and manifestations" (PDF). American Journal of Audiology. 23 (4): 402–19. doi:10.1044/2014_AJA-14-0010. PMID 25104073.

- Foster, Carol A. (2015). "Optimal management of Ménière's disease". Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 11: 301–307. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S59023. ISSN 1176-6336. PMC 4348125. PMID 25750534.

- Weinreich, Heather M.; Agrawal, Yuri (June 2014). "The Link Between Allergy and Menière's Disease". Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery. 22 (3): 227–230. doi:10.1097/MOO.0000000000000041. ISSN 1068-9508. PMC 4549154. PMID 24573125.

- Storper, Ian S.; Spitzer, Jaclyn B.; Scanlan, Mark (1998). "Use of glycopyrrolate in the treatment of Meniere's disease". The Laryngoscope. 108 (10): 1442–5. doi:10.1097/00005537-199810000-00004. PMID 9778280. S2CID 39137575.

- Thirlwall, A. S.; Kundu, S. (19 July 2006). "Diuretics for Ménière's disease or syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD003599. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003599.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 16856015.

- Crowson, Matthew G.; Patki, Aniruddha; Tucci, Debara L. (May 2016). "A Systematic Review of Diuretics in the Medical Management of Ménière's Disease". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 154 (5): 824–834. doi:10.1177/0194599816630733. ISSN 1097-6817. PMID 26932948. S2CID 24741244.

- Stern Shavit S, Lalwani AK (2019). "Are diuretics useful in the treatment of meniere disease?". Laryngoscope. 129 (10): 2206–2207. doi:10.1002/lary.28040. PMID 31046134.

- Pullens, B; van Benthem, PP (16 March 2011). "Intratympanic gentamicin for Ménière's disease or syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD008234. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008234.pub2. PMID 21412917.

- Huon, Leh-Kiong; Fang, Te-Yung; Wang, Pa-Chun (July 2012). "Outcomes of intratympanic gentamicin injection to treat Ménière's disease". Otology & Neurotology. 33 (5): 706–714. doi:10.1097/MAO.0b013e318259b3b1. PMID 22699980. S2CID 32209105.

- Espinosa-Sanchez, JM; Lopez-Escamez, JA (2016). "Menière's disease". Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 137: 257–77. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-63437-5.00019-4. ISBN 9780444634375. PMID 27638077.

- Hussain, Kiran; Murdin, Louisa; Schilder, Anne GM (31 December 2018). "Restriction of salt, caffeine and alcohol intake for the treatment of Ménière's disease or syndrome". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (12): CD012173. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012173.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6516805. PMID 30596397.

- Clendaniel, R. A.; Tucci, D. L. (December 1997). "Vestibular rehabilitation strategies in Meniere's disease". Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America. 30 (6): 1145–1158. doi:10.1016/S0030-6665(20)30155-9. ISSN 0030-6665. PMID 9386249.

- Orji, Ft (2014). "The Influence of Psychological Factors in Meniere's Disease". Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research. 4 (1): 3–7. doi:10.4103/2141-9248.126601. ISSN 2141-9248. PMC 3952292. PMID 24669323.

- Greenberg, Simon L.; Nedzelski, Julian M. (October 2010). "Medical and noninvasive therapy for Meniere's disease". Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America. 43 (5): 1081–1090. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2010.05.005. ISSN 1557-8259. PMID 20713246.

- Lim, Ming Yann; Zhang, Margaret; Yuen, Heng Wai; et al. (November 2015). "Current evidence for endolymphatic sac surgery in the treatment of Meniere's disease: a systematic review". Singapore Medical Journal. 56 (11): 593–98. doi:10.11622/smedj.2015166. ISSN 0037-5675. PMC 4656865. PMID 26668402.

- Sood, Amit Justin; Lambert, Paul R.; Nguyen, Shaun A.; et al. (July 2014). "Endolymphatic sac surgery for Ménière's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Otology & Neurotology. 35 (6): 1033–1045. doi:10.1097/MAO.0000000000000324. ISSN 1537-4505. PMID 24751747. S2CID 31381271.

- Walther LE (2005). "Procedures for restoring vestibular disorders". GMS Current Topics in Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery. 4: Doc05. PMC 3201005. PMID 22073053.

- Pullens, Bas; Verschuur, Hendrik P.; van Benthem, Peter Paul (2013). "Surgery for Ménière's disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD005395. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005395.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7389445. PMID 23450562.

- James, A. L.; Burton, M. J. (2001). "Betahistine for Menière's disease or syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD001873. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001873. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6769057. PMID 11279734.

- Adrion, C; Fischer, C. S.; Wagner, J; et al. (2016). "Efficacy and safety of betahistine treatment in patients with Meniere's disease: Primary results of a long term, multicentre, double blind, randomised, placebo controlled, dose defining trial (BEMED trial)". BMJ. 352: h6816. doi:10.1136/bmj.h6816. PMC 4721211. PMID 26797774.

- van Sonsbeek S, Pullens B, van Benthem PP (2015). "Positive pressure therapy for Ménière's disease or syndrome". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD008419. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008419.pub2. PMID 25756795.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Syed, M. I.; Rutka, J. A.; Hendry, J; et al. (2015). "Positive pressure therapy for Meniere's syndrome/disease with a Meniett device: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials". Clinical Otolaryngology. 40 (3): 197–207. doi:10.1111/coa.12344. PMID 25346252. S2CID 1025535.

- Hu, A; Parnes, L. S. (2009). "Intratympanic steroids for inner ear disorders: A review". Audiology and Neurotology. 14 (6): 373–82. doi:10.1159/000241894. PMID 19923807. S2CID 38726308.

- Miller MW, Agrawal Y (2014). "Intratympanic Therapies for Menière's disease". Current Otorhinolaryngology Reports. 2 (3): 137–143. doi:10.1007/s40136-014-0055-8. PMC 4157672. PMID 25215266.

- Phillips, John S.; Westerberg, Brian (6 July 2011). "Intratympanic steroids for Ménière's disease or syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD008514. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008514.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 21735432.

- Iwasaki, Shinichi; Yamasoba, Tatsuya (February 2015). "Dizziness and Imbalance in the Elderly: Age-related Decline in the Vestibular System". Aging and Disease. 6 (1): 38–47. doi:10.14336/AD.2014.0128. ISSN 2152-5250. PMC 4306472. PMID 25657851.

- Ishiyama, G.; et al. (April 2015). "Meniere's disease: histopathology, cytochemistry, and imaging". Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1343 (1): 49–57. Bibcode:2015NYASA1343...49I. doi:10.1111/nyas.12699. PMID 25766597. S2CID 36495592.

- Ménière, Prosper (1861). "Sur une forme de surdité grave dépendant d'une lésion de l'oreille interne" [On a form of severe deafness dependent on a lesion of the inner ear]. Bulletin de l'Académie Impériale de Médecine (in French). republished online at gallica.bnf.fr. 26: 241. Archived from the original on 16 February 2016.

- Beasley NJ, Jones NS (December 1996). "Menière's disease: evolution of a definition". J Laryngol Otol. 110 (12): 1, 107–13. doi:10.1017/S002221510013590X. PMID 9015421.

External links

- Basura, Gregory J.; Adams, Meredith E.; Monfared, Ashkan; et al. (8 April 2020). "Clinical Practice Guideline: Ménière's Disease". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 162 (2 suppl): S1–S55. doi:10.1177/0194599820909438. PMID 32267799.