Brain tumor

A brain tumor occurs when abnormal cells form within the brain.[2] There are two main types of tumors: malignant tumors and benign (non-cancerous) tumors.[2] These can be further classified as primary tumors, which start within the brain, and secondary tumors, which most commonly have spread from tumors located outside the brain, known as brain metastasis tumors.[1] All types of brain tumors may produce symptoms that vary depending on the size of the tumor and the part of the brain that is involved.[2] Where symptoms exist, they may include headaches, seizures, problems with vision, vomiting and mental changes.[1][2][7] Other symptoms may include difficulty walking, speaking, with sensations, or unconsciousness.[1][3]

| Brain tumor | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Intracranial neoplasm, brain tumour |

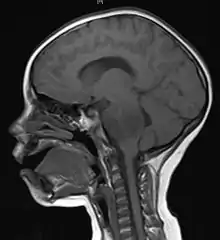

| |

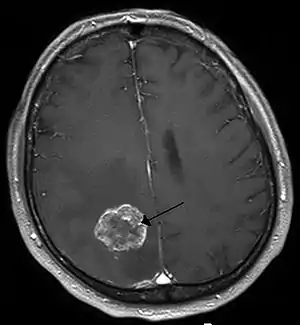

| Brain metastasis in the right cerebral hemisphere from lung cancer, shown on magnetic resonance imaging | |

| Specialty | Neurosurgery, Neuro-oncology |

| Symptoms | Vary depending on the part of the brain involved, headaches, seizures, problem with vision, vomiting, mental changes[1][2] |

| Types | Malignant, benign[2] |

| Causes | Usually unknown[2] |

| Risk factors | Neurofibromatosis, exposure to vinyl chloride, Epstein–Barr virus, ionizing radiation[1][2][3] |

| Diagnostic method | Computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, tissue biopsy[1][2] |

| Treatment | Surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy[1] |

| Medication | Anticonvulsants, dexamethasone, furosemide[1] |

| Prognosis | Average five-year survival rate 33% (US)[4] |

| Frequency | 1.2 million nervous system cancers (2015)[5] |

| Deaths | 228,800 (worldwide, 2015)[6] |

The cause of most brain tumors is unknown.[2] Uncommon risk factors include exposure to vinyl chloride, Epstein–Barr virus, ionizing radiation, and inherited syndromes such as neurofibromatosis, tuberous sclerosis, and von Hippel-Lindau Disease.[1][2][3] Studies on mobile phone exposure have not shown a clear risk.[3] The most common types of primary tumors in adults are meningiomas (usually benign) and astrocytomas such as glioblastomas.[1] In children, the most common type is a malignant medulloblastoma.[3] Diagnosis is usually by medical examination along with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).[2] The result is then often confirmed by a biopsy. Based on the findings, the tumors are divided into different grades of severity.[1]

Treatment may include some combination of surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy.[1] Since the brain is the body's only non-fungible organ, surgery carries a risk of the tumor returning. If seizures occur, anticonvulsant medication may be needed.[1] Dexamethasone and furosemide are medications that may be used to decrease swelling around the tumor.[1] Some tumors grow gradually, requiring only monitoring and possibly needing no further intervention.[1] Treatments that use a person's immune system are being studied.[2] Outcomes for malignant tumors vary considerably depending on the type of tumor and how far it has spread at diagnosis.[3] Although benign tumors only grow in one area, they may still be life-threatening depending on their size and location.[8] Malignant glioblastomas usually have very poor outcomes, while benign meningiomas usually have good outcomes.[3] The average five-year survival rate for all (malignant) brain cancers in the United States is 33%.[4]

Secondary, or metastatic, brain tumors are about four times as common as primary brain tumors,[2][9] with about half of metastases coming from lung cancer.[2] Primary brain tumors occur in around 250,000 people a year globally, and make up less than 2% of cancers.[3] In children younger than 15, brain tumors are second only to acute lymphoblastic leukemia as the most common form of cancer.[10] In NSW Australia in 2005, the average lifetime economic cost of a case of brain cancer was AU$1.9 million, the greatest of any type of cancer.[11]

Signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of brain tumors are broad. People may experience symptoms regardless of whether the tumor is benign (not cancerous) or cancerous.[12] Primary and secondary brain tumors present with similar symptoms, depending on the location, size, and rate of growth of the tumor.[13] For example, larger tumors in the frontal lobe can cause changes in the ability to think. However, a smaller tumor in an area such as Wernicke's area (small area responsible for language comprehension) can result in a greater loss of function.[14]

Headaches

Headaches as a result of raised intracranial pressure can be an early symptom of brain cancer.[15] However, isolated headache without other symptoms is rare, and other symptoms including visual abnormalities may occur before headaches become common.[15] Certain warning signs for headache exist which make the headache more likely to be associated with brain cancer.[15] These are, as defined by the American Academy of Neurology: "abnormal neurological examination, headache worsened by Valsalva maneuver, headache causing awakening from sleep, new headache in the older population, progressively worsening headache, atypical headache features, or patients who do not fulfill the strict definition of migraine".[15] Other associated signs are headaches that are worse in the morning or that subside after vomiting.[16]

Location-specific symptoms

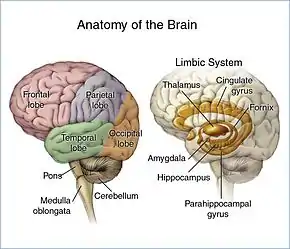

The brain is divided into lobes and each lobe or area has its own function.[17][18] A tumor in any of these lobes may affect the area's performance. The symptoms experienced are often linked to the location of the tumor, but each person may experience something different.[19]

- Frontal lobe: Tumors may contribute to poor reasoning, inappropriate social behavior, personality changes, poor planning, lower inhibition, and decreased production of speech (Broca's area).[19]

- Temporal lobe: Tumors in this lobe may contribute to poor memory, loss of hearing, and difficulty in language comprehension (Wernicke's area is located in this lobe).[18]

- Parietal lobe: Tumors here may result in poor interpretation of languages, difficulty with speaking, writing, drawing, naming, and recognizing, and poor spatial and visual perception.[20]

- Occipital lobe: Damage to this lobe may result in poor vision or loss of vision.[21]

- Cerebellum: Tumors in this area may cause poor balance, muscle movement, and posture.[22]

- Brain stem: Tumors on the brainstem can cause seizures, endocrine problems, respiratory changes, visual changes, headaches and partial paralysis.[22]

Behavior changes

A person's personality may be altered due to the tumor damaging lobes of the brain. Since the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes[13] control inhibition, emotions, mood, judgement, reasoning, and behavior, a tumor in those regions can cause inappropriate social behavior,[23] temper tantrums,[23] laughing at things which merit no laughter,[23] and even psychological symptoms such as depression and anxiety.[19] More research is needed into the effectiveness and safety of medication for depression in people with brain tumors.[24]

Personality changes can have damaging effects such as unemployment, unstable relationships, and a lack of control.[17]

Cause

Epidemiological studies are required to determine risk factors.[25] Aside from exposure to vinyl chloride or ionizing radiation, there are no known environmental factors associated with brain tumors. Mutations and deletions of tumor suppressor genes, such as P53, are thought to be the cause of some forms of brain tumor.[26] Inherited conditions, such as Von Hippel–Lindau disease, tuberous sclerosis, multiple endocrine neoplasia, and neurofibromatosis type 2 carry a high risk for the development of brain tumors.[1][27][28] People with celiac disease have a slightly increased risk of developing brain tumors.[29] Smoking has been suggested to increase the risk but evidence remains unclear.[30]

Although studies have not shown any link between cell phone or mobile phone radiation and the occurrence of brain tumors,[31] the World Health Organization has classified mobile phone radiation on the IARC scale into Group 2B – possibly carcinogenic.[32] The claim that cell phone usage may cause brain cancer is likely based on epidemiological studies which observed a slight increase in glioma risk among heavy users of wireless phones. When those studies were conducted, GSM (2G) phones were in use. Modern, third-generation (3G) phones emit, on average, about 1% of the energy emitted by those GSM (2G) phones, and therefore the finding of an association between cell phone usage and increased risk of brain cancer is not based upon current phone usage.[3]

Pathophysiology

Meninges

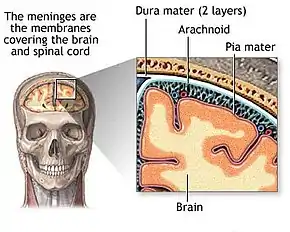

Human brains are surrounded by a system of connective tissue membranes called meninges that separate the brain from the skull. This three-layered covering is composed of (from the outside in) the dura mater, arachnoid mater, and pia mater. The arachnoid and pia are physically connected and thus often considered as a single layer, the leptomeninges. Between the arachnoid mater and the pia mater is the subarachnoid space which contains cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This fluid circulates in the narrow spaces between cells and through the cavities in the brain called ventricles, to support and protect the brain tissue. Blood vessels enter the central nervous system through the perivascular space above the pia mater. The cells in the blood vessel walls are joined tightly, forming the blood–brain barrier which protects the brain from toxins that might enter through the blood.[33]

Tumors of the meninges are meningiomas and are often benign. Though not technically a tumor of brain tissue, they are often considered brain tumors since they protrude into the space where the brain is, causing symptoms. Since they are usually slow-growing tumors, meningiomas can be quite large by the time symptoms appear.[34]

Brain matter

The brains of humans and other vertebrates are composed of very soft tissue and have a gelatin-like texture. Living brain tissue has a pink tint in color on the outside (gray matter), and nearly complete white on the inside (white matter), with subtle variations in color. The three largest divisions of the brain are:

- Cerebral cortex

- Brainstem

- Cerebellum[33]

These areas are composed of two broad classes of cells: neurons and glia. These two types are equally numerous in the brain as a whole, although glial cells outnumber neurons roughly 4 to 1 in the cerebral cortex. Glia come in several types, which perform a number of critical functions, including structural support, metabolic support, insulation, and guidance of development.[35] Primary tumors of the glial cells are called gliomas and often are malignant by the time they are diagnosed.[36]

The thalamus and hypothalamus are major divisions of the diencephalon, with the pituitary gland and pineal gland attached at the bottom; tumors of the pituitary and pineal gland are often benign.

The brainstem lies between the large cerebral cortex and the spinal cord. It is divided into the midbrain, pons, and medulla oblongata.[33]

Spinal cord

The spinal cord is considered a part of the central nervous system.[37] It is made up of the same cells as the brain: neurons and glial cells.[33]

Diagnosis

Although there is no specific or singular symptom or sign, the presence of a combination of symptoms and the lack of corresponding indications of other causes can be an indicator for investigation towards the possibility of a brain tumor. Brain tumors have similar characteristics and obstacles when it comes to diagnosis and therapy with tumors located elsewhere in the body. However, they create specific issues that follow closely to the properties of the organ they are in.[38]

The diagnosis will often start by taking a medical history noting medical antecedents, and current symptoms. Clinical and laboratory investigations will serve to exclude infections as the cause of the symptoms. Examinations in this stage may include the eyes, otolaryngological (or ENT) and electrophysiological exams. The use of electroencephalography (EEG) often plays a role in the diagnosis of brain tumors.

Brain tumors, when compared to tumors in other areas of the body, pose a challenge for diagnosis. Commonly, radioactive tracers are uptaken in large volumes in tumors due to the high activity of tumor cells, allowing for radioactive imaging of the tumor. However, most of the brain is separated from the blood by the blood-brain barrier (BBB), a membrane that exerts a strict control over what substances are allowed to pass into the brain. Therefore, many tracers that may reach tumors in other areas of the body easily would be unable to reach brain tumors until there was a disruption of the BBB by the tumor. Disruption of the BBB is well imaged via MRI or CT scan, and is therefore regarded as the main diagnostic indicator for malignant gliomas, meningiomas, and brain metastases.[38]

Swelling or obstruction of the passage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the brain may cause (early) signs of increased intracranial pressure which translates clinically into headaches, vomiting, or an altered state of consciousness, and in children changes to the diameter of the skull and bulging of the fontanelles. More complex symptoms such as endocrine dysfunctions should alarm doctors not to exclude brain tumors.

A bilateral temporal visual field defect (due to compression of the optic chiasm) or dilation of the pupil, and the occurrence of either slowly evolving or the sudden onset of focal neurologic symptoms, such as cognitive and behavioral impairment (including impaired judgment, memory loss, lack of recognition, spatial orientation disorders), personality or emotional changes, hemiparesis, hypoesthesia, aphasia, ataxia, visual field impairment, impaired sense of smell, impaired hearing, facial paralysis, double vision, or more severe symptoms such as tremors, paralysis on one side of the body hemiplegia, or (epileptic) seizures in a patient with a negative history for epilepsy, should raise the possibility of a brain tumor.

Imaging

Medical imaging plays a central role in the diagnosis of brain tumors. Early imaging methods – invasive and sometimes dangerous – such as pneumoencephalography and cerebral angiography have been abandoned in favor of non-invasive, high-resolution techniques, especially magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans,[37] though MRI is typically the reference standard used.[39] Neoplasms will often show as differently colored masses (also referred to as processes) in CT or MRI results.

- Benign brain tumors often show up as hypodense (darker than brain tissue) mass lesions on CT scans. On MRI, they appear either hypodense or isointense (same intensity as brain tissue) on T1-weighted scans, or hyperintense (brighter than brain tissue) on T2-weighted MRI, although the appearance is variable.

- Contrast agent uptake, sometimes in characteristic patterns, can be demonstrated on either CT or MRI scans in most malignant primary and metastatic brain tumors.

- Pressure areas where the brain tissue has been compressed by a tumor also appear hyperintense on T2-weighted scans and might indicate the presence a diffuse neoplasm due to an unclear outline. Swelling around the tumor known as peritumoral edema can also show a similar result.

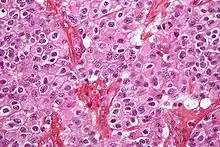

This is because these tumors disrupt the normal functioning of the BBB and lead to an increase in its permeability. More recently, advancements have been made to increase the utility of MRI in providing physiological data that can help to inform diagnosis and prognosis. Perfusion Weighted Imaging (PWI) and Diffusion Weighted Imaging (DWI) are two MRI techniques that reviews have been shown to be useful in classifying tumors by grade, which was not previously viable using only structural imaging.[40] However, these techniques cannot alone diagnose high- versus low-grade gliomas, and thus the definitive diagnosis of brain tumor should only be confirmed by histological examination of tumor tissue samples obtained either by means of brain biopsy or open surgery. The histological examination is essential for determining the appropriate treatment and the correct prognosis. This examination, performed by a pathologist, typically has three stages: interoperative examination of fresh tissue, preliminary microscopic examination of prepared tissues, and follow-up examination of prepared tissues after immunohistochemical staining or genetic analysis.

Pathology

Tumors have characteristics that allow the determination of malignancy and how they will evolve, and determining these characteristics will allow the medical team to determine the management plan.

Anaplasia or dedifferentiation: loss of differentiation of cells and of their orientation to one another and blood vessels, a characteristic of anaplastic tumor tissue. Anaplastic cells have lost total control of their normal functions and many have deteriorated cell structures. Anaplastic cells often have abnormally high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios, and many are multinucleated. Additionally, the nucleus of anaplastic cells is usually unnaturally shaped or oversized. Cells can become anaplastic in two ways: neoplastic tumor cells can dedifferentiate to become anaplasias (the dedifferentiation causes the cells to lose all of their normal structure/function), or cancer stem cells can increase their capacity to multiply (i.e., uncontrollable growth due to failure of differentiation).

Atypia: an indication of abnormality of a cell (which may be indicative of malignancy). Significance of the abnormality is highly dependent on context.[41]

Neoplasia: the (uncontrolled) division of cells. As such, neoplasia is not problematic but its consequences are: the uncontrolled division of cells means that the mass of a neoplasm increases in size, and in a confined space such as the intracranial cavity this quickly becomes problematic because the mass invades the space of the brain pushing it aside, leading to compression of the brain tissue and increased intracranial pressure and destruction of brain parenchyma. Increased intracranial pressure (ICP) may be attributable to the direct mass effect of the tumor, increased blood volume, or increased cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) volume, which may, in turn, have secondary symptoms.

Necrosis: the (premature) death of cells, caused by external factors such as infection, toxin or trauma. Necrotic cells send the wrong chemical signals which prevent phagocytes from disposing of the dead cells, leading to a buildup of dead tissue, cell debris and toxins at or near the site of the necrotic cells[42]

Arterial and venous hypoxia, or the deprivation of adequate oxygen supply to certain areas of the brain, occurs when a tumor makes use of nearby blood vessels for its supply of blood and the neoplasm enters into competition for nutrients with the surrounding brain tissue.[43] More generally a neoplasm may cause release of metabolic end products (e.g., free radicals, altered electrolytes, neurotransmitters), and release and recruitment of cellular mediators (e.g., cytokines) that disrupt normal parenchymal function.[44]

Classification

Tumors can be benign or malignant, can occur in different parts of the brain, and may be classified as primary or secondary. A primary tumor is one that has started in the brain, as opposed to a metastatic tumor, which is one that has spread to the brain from another area of the body.[45] The incidence of metastatic tumors is approximately four times greater than primary tumors.[9] Tumors may or may not be symptomatic: some tumors are discovered because the patient has symptoms, others show up incidentally on an imaging scan, or at an autopsy.

Grading of the tumors of the central nervous system commonly occurs on a 4-point scale (I-IV) created by the World Health Organization in 1993. Grade I tumors are the least severe and commonly associated with long-term survival, with severity and prognosis worsening as the grade increases. Low-grade tumors are often benign, while higher grades are aggressively malignant and/or metastatic. Other grading scales do exist, many based upon the same criteria as the WHO scale and graded from I-IV.[46]

Primary

The most common primary brain tumors are:[47]

- Pituitary adenomas[48] (15%)

- Nerve sheath tumors (10%)

These common tumors can also be organized according to tissue of origin as shown below:[49]

|

Tissue of origin |

Children | Adults |

|---|---|---|

| Astrocytes | Pilocytic Astrocytoma (PCA) | Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM) |

| Oligodendrocytes | Oligodendroglioma | |

| Ependyma | Ependymoma | |

| Neurons | Medulloblastoma | |

| Meninges | Meningioma |

Secondary

Secondary tumors of the brain are metastatic and have invaded the brain from cancers originating in other organs. This means that a cancerous neoplasm has developed in another organ elsewhere in the body and that cancer cells have leaked from that primary tumor and then entered the lymphatic system and blood vessels. They then circulate through the bloodstream, and are deposited in the brain. There, these cells continue growing and dividing, becoming another invasive neoplasm of primary cancer's tissue. Secondary tumors of the brain are very common in the terminal phases of patients with an incurable metastasized cancer; the most common types of cancers that bring about secondary tumors of the brain are lung cancer, breast cancer, malignant melanoma, kidney cancer, and colon cancer (in decreasing order of frequency).

Secondary brain tumors are more common than primary ones; in the United States, there are about 170,000 new cases every year. Secondary brain tumors are the most common cause of tumors in the intracranial cavity. The skull bone structure can also be subject to a neoplasm that by its very nature reduces the volume of the intracranial cavity, and can damage the brain.[50]

By behavior

Brain tumors or intracranial neoplasms can be cancerous (malignant) or non-cancerous (benign). However, the definitions of malignant or benign neoplasms differ from those commonly used in other types of cancerous or non-cancerous neoplasms in the body. In cancers elsewhere in the body, three malignant properties differentiate benign tumors from malignant forms of cancer: benign tumors are self-limited and do not invade or metastasize. Characteristics of malignant tumors include:

- uncontrolled mitosis (growth by division beyond the normal limits)

- anaplasia: the cells in the neoplasm have an obviously different form (in size and shape). Anaplastic cells display marked pleomorphism. The cell nuclei are characteristically extremely hyperchromatic (darkly stained) and enlarged; the nucleus might have the same size as the cytoplasm of the cell (nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio may approach 1:1, instead of the normal 1:4 or 1:6 ratio). Giant cells – considerably larger than their neighbors – may form and possess either one enormous nucleus or several nuclei (syncytia). Anaplastic nuclei are variable and bizarre in size and shape.

- invasion or infiltration (medical literature uses these terms as synonymous equivalents. However, for clarity, the articles that follow adhere to a convention that they mean slightly different things; this convention is not followed outside these articles):

- Invasion or invasiveness is the spatial expansion of the tumor through uncontrolled mitosis, in the sense that the neoplasm invades the space occupied by adjacent tissue, thereby pushing the other tissue aside and eventually compressing the tissue. Often these tumors are associated with clearly outlined tumors in imaging.

- Infiltration is the behavior of the tumor either to grow (microscopic) tentacles that push into the surrounding tissue (often making the outline of the tumor undefined or diffuse) or to have tumor cells "seeded" into the tissue beyond the circumference of the tumorous mass; this does not mean that an infiltrative tumor does not take up space or does not compress the surrounding tissue as it grows, but an infiltrating neoplasm makes it difficult to say where the tumor ends and the healthy tissue starts.

- metastasis (spread to other locations in the body via lymph or blood).

Of the above malignant characteristics, some elements do not apply to primary neoplasms of the brain:

- Primary brain tumors rarely metastasize to other organs; some forms of primary brain tumors can metastasize but will not spread outside the intracranial cavity or the central spinal canal. Due to the BBB, cancerous cells of a primary neoplasm cannot enter the bloodstream and get carried to another location in the body. (Occasional isolated case reports suggest spread of certain brain tumors outside the central nervous system, e.g. bone metastasis of glioblastoma multiforme.[51])

- Primary brain tumors generally are invasive (i.e. they will expand spatially and intrude into the space occupied by other brain tissue and compress those brain tissues); however, some of the more malignant primary brain tumors will infiltrate the surrounding tissue.

By genetics

In 2016, the WHO restructured their classifications of some categories of gliomas to include distinct genetic mutations that have been useful in differentiating tumor types, prognoses, and treatment responses. Genetic mutations are typically detected via immunohistochemistry, a technique that visualizes the presence or absence of a targeted protein via staining.[39]

- Mutations in IDH1 and IDH2 genes are commonly found in low-grade gliomas

- Loss of both IDH genes combined with loss of chromosome arms 1p and 19q indicates the tumor is an oligodendroglioma[52]

- Loss of TP53 and ATRX characterizes astrocytomas

- Genes EGFR, TERT, and PTEN, are commonly altered in gliomas and are useful in differentiating tumor grade and biology[39]

Specific types

Anaplastic astrocytoma, Anaplastic oligodendroglioma, Astrocytoma, Central neurocytoma, Choroid plexus carcinoma, Choroid plexus papilloma, Choroid plexus tumor, Colloid cyst, Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumour, Ependymal tumor, Fibrillary astrocytoma, Giant-cell glioblastoma, Glioblastoma multiforme, Gliomatosis cerebri, Gliosarcoma, Hemangiopericytoma, Medulloblastoma, Medulloepithelioma, Meningeal carcinomatosis, Neuroblastoma, Neurocytoma, Oligoastrocytoma, Oligodendroglioma, Optic nerve sheath meningioma, Pediatric ependymoma, Pilocytic astrocytoma, Pinealoblastoma, Pineocytoma, Pleomorphic anaplastic neuroblastoma, Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, Primary central nervous system lymphoma, Sphenoid wing meningioma, Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma, Subependymoma, Trilateral retinoblastoma.

Treatment

A medical team generally assesses the treatment options and presents them to the person affected and their family. Various types of treatment are available depending on tumor type and location, and may be combined to produce the best chances of survival:[48]

- Surgery:[48] complete or partial resection of the tumor with the objective of removing as many tumor cells as possible.

- Radiotherapy:[48] the most commonly used treatment for brain tumors; the tumor is irradiated with beta, x rays or gamma rays.

- Chemotherapy:[48] a treatment option for cancer, however, it is not always used to treat brain tumors as the blood-brain barrier can prevent some drugs from reaching the cancerous cells.

- A variety of experimental therapies are available through clinical trials.

Survival rates in primary brain tumors depend on the type of tumor, age, functional status of the patient, the extent of surgical removal and other factors specific to each case.[53]

Standard care for anaplastic oligodendrogliomas and anaplastic oligoastrocytomas is surgery followed by radiotherapy. One study found a survival benefit for the addition of chemotherapy to radiotherapy after surgery, compared with radiotherapy alone.[54]

Surgery

The primary and most desired course of action described in medical literature is surgical removal (resection) via craniotomy.[48] Minimally invasive techniques are becoming the dominant trend in neurosurgical oncology.[55] The main objective of surgery is to remove as many tumor cells as possible, with complete removal being the best outcome and cytoreduction ("debulking") of the tumor otherwise. A Gross Total Resection (GTR) occurs when all visible signs of the tumor are removed, and subsequent scans show no apparent tumor.[56] In some cases access to the tumor is impossible and impedes or prohibits surgery.

Many meningiomas, with the exception of some tumors located at the skull base, can be successfully removed surgically. Most pituitary adenomas can be removed surgically, often using a minimally invasive approach through the nasal cavity and skull base (trans-nasal, trans-sphenoidal approach). Large pituitary adenomas require a craniotomy (opening of the skull) for their removal. Radiotherapy, including stereotactic approaches, is reserved for inoperable cases.

Several current research studies aim to improve the surgical removal of brain tumors by labeling tumor cells with 5-aminolevulinic acid that causes them to fluoresce.[57] Postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy are integral parts of the therapeutic standard for malignant tumors.[58][59]

Multiple metastatic tumors are generally treated with radiotherapy and chemotherapy rather than surgery and the prognosis in such cases is determined by the primary tumor, and is generally poor.

Radiation therapy

The goal of radiation therapy is to kill tumor cells while leaving normal brain tissue unharmed. In standard external beam radiation therapy, multiple treatments of standard-dose "fractions" of radiation are applied to the brain. This process is repeated for a total of 10 to 30 treatments, depending on the type of tumor. This additional treatment provides some patients with improved outcomes and longer survival rates.

Radiosurgery is a treatment method that uses computerized calculations to focus radiation at the site of the tumor while minimizing the radiation dose to the surrounding brain. Radiosurgery may be an adjunct to other treatments, or it may represent the primary treatment technique for some tumors. Forms used include stereotactic radiosurgery, such as Gamma knife, Cyberknife or Novalis Tx radiosurgery.[60]

Radiotherapy is the most common treatment for secondary brain tumors. The amount of radiotherapy depends on the size of the area of the brain affected by cancer. Conventional external beam "whole-brain radiotherapy treatment" (WBRT) or "whole-brain irradiation" may be suggested if there is a risk that other secondary tumors will develop in the future.[61] Stereotactic radiotherapy is usually recommended in cases involving fewer than three small secondary brain tumors. Radiotherapy may be used following, or in some cases in place of, resection of the tumor. Forms of radiotherapy used for brain cancer include external beam radiation therapy, the most common, and brachytherapy and proton therapy, the last especially used for children.

People who receive stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) and whole-brain radiation therapy (WBRT) for the treatment of metastatic brain tumors have more than twice the risk of developing learning and memory problems than those treated with SRS alone.[62][63] Results of a 2021 systematic review found that when using SRS as the initial treatment, survival or death related to brain metastasis was not greater than alone versus SRS with WBRT.[64]

Postoperative conventional daily radiotherapy improves survival for adults with good functional well-being and high grade glioma compared to no postoperative radiotherapy. Hypofractionated radiation therapy has similar efficacy for survival as compared to conventional radiotherapy, particularly for individuals aged 60 and older with glioblastoma.[65]

Chemotherapy

Patients undergoing chemotherapy are administered drugs designed to kill tumor cells.[48] Although chemotherapy may improve overall survival in patients with the most malignant primary brain tumors, it does so in only about 20 percent of patients. Chemotherapy is often used in young children instead of radiation, as radiation may have negative effects on the developing brain. The decision to prescribe this treatment is based on a patient's overall health, type of tumor, and extent of cancer. The toxicity and many side effects of the drugs, and the uncertain outcome of chemotherapy in brain tumors puts this treatment further down the line of treatment options with surgery and radiation therapy preferred.[66]

UCLA Neuro-Oncology publishes real-time survival data for patients with a diagnosis of glioblastoma multiforme. They are the only institution in the United States that displays how brain tumor patients are performing on current therapies. They also show a listing of chemotherapy agents used to treat high-grade glioma tumors.[67]

Genetic mutations have significant effects on the effectiveness of chemotherapy. Gliomas with IDH1 or IDH2 mutations respond better to chemotherapy than those without the mutation. Loss of chromosome arms 1p and 19q also indicate better response to chemoradiation.[39]

Other

A shunt may be used to relieve symptoms caused by intracranial pressure, by reducing the build-up of fluid (hydrocephalus) caused by the blockage of the free flow of cerebrospinal fluid.[68]

Prognosis

The prognosis of brain cancer depends on the type of cancer diagnosed. Medulloblastoma has a good prognosis with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgical resection while glioblastoma multiforme has a median survival of only 12 months even with aggressive chemoradiotherapy and surgery. Brainstem gliomas have the poorest prognosis of any form of brain cancer, with most patients dying within one year, even with therapy that typically consists of radiation to the tumor along with corticosteroids. However, one type, focal brainstem gliomas in children, seems open to exceptional prognosis and long-term survival has frequently been reported.[69]

Prognosis is also affected by presentation of genetic mutations. Certain mutations provide better prognosis than others. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas, as well as deletion of chromosome arms 1p and 19q, generally indicate better prognosis. TP53, ATRX, EGFR, PTEN, and TERT mutations are also useful in determining prognosis.[39]

Glioblastoma multiforme

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most aggressive (grade IV) and most common form of a malignant brain tumor. Even when aggressive multimodality therapy consisting of radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and surgical excision is used, median survival is only 12–17 months. Standard therapy for glioblastoma multiforme consists of maximal surgical resection of the tumor, followed by radiotherapy between two and four weeks after the surgical procedure to remove the cancer, then by chemotherapy, such as temozolomide.[70] Most patients with glioblastoma take a corticosteroid, typically dexamethasone, during their illness to relieve symptoms. Experimental treatments include targeted therapy, gamma knife radiosurgery,[71] boron neutron capture therapy, gene therapy also chemowafer implants.[72][73]

Oligodendrogliomas

Oligodendrogliomas are incurable but slowly progressive malignant brain tumors. They can be treated with surgical resection, chemotherapy, radiotherapy or a combination. For some suspected low-grade (grade II) tumors, only a course of watchful waiting and symptomatic therapy is opted for. These tumors show a high frequency of co-deletions of the p and q arms of chromosome 1 and chromosome 19 respectively (1p19q co-deletion) and have been found to be especially chemosensitive with one report claiming them to be one of the most chemosensitive tumors.[74] A median survival of up to 16.7 years has been reported for grade II oligodendrogliomas.[75]

Acoustic neuroma

Acoustic neuromas are non-cancerous tumors.[76] They can be treated with surgery, radiation therapy, or observation. Early intervention with surgery or radiation is recommended to prevent progressive hearing loss.[77]

Epidemiology

Figures for incidences of cancers of the brain show a significant difference between more- and less-developed countries (the less-developed countries have lower incidences of tumors of the brain).[78] This could be explained by undiagnosed tumor-related deaths (patients in extremely poor situations do not get diagnosed, simply because they do not have access to the modern diagnostic facilities required to diagnose a brain tumor) and by deaths caused by other poverty-related causes that preempt a patient's life before tumors develop or tumors become life-threatening. Nevertheless, statistics suggest that certain forms of primary brain tumors are more common among certain populations.[79]

The incidence of low-grade astrocytoma has not been shown to vary significantly with nationality. However, studies examining the incidence of malignant central nervous system (CNS) tumors have shown some variation with national origin. Since some high-grade lesions arise from low-grade tumors, these trends are worth mentioning. Specifically, the incidence of CNS tumors in the United States, Israel, and the Nordic countries is relatively high, while Japan and Asian countries have a lower incidence. These differences probably reflect some biological differences as well as differences in pathologic diagnosis and reporting.[80] Worldwide data on incidence of cancer can be found at the WHO (World Health Organisation) and is handled by the IARC (International Agency for Research on Cancer) located in France.[81]

United States

In the United States in 2015, approximately 166,039 people were living with brain or other central nervous system tumors. Over 2018, it was projected that there would be 23,880 new cases of brain tumors and 16,830 deaths in 2018 as a result,[79] accounting for 1.4 percent of all cancers and 2.8 percent of all cancer deaths.[82] Median age of diagnosis was 58 years old, while median age of death was 65. Diagnosis was slightly more common in males, at approximately 7.5 cases per 100 000 people, while females saw 2 fewer at 5.4. Deaths as a result of brain cancer were 5.3 per 100 000 for males, and 3.6 per 100 000 for females, making brain cancer the 10th leading cause of cancer death in the United States. Overall lifetime risk of developing brain cancer is approximated at 0.6 percent for men and women.[79][83]

UK

Brain, other CNS or intracranial tumors are the ninth most common cancer in the UK (around 10,600 people were diagnosed in 2013), and it is the eighth most common cause of cancer death (around 5,200 people died in 2012).[84] White British patients with brain tumour are 30% more likely to die within a year of diagnosis than patients from other ethnicities. The reason for this is unknown.[85]

Children

In the United States more than 28,000 people under 20 are estimated to have a brain tumor.[86] About 3,720 new cases of brain tumors are expected to be diagnosed in those under 15 in 2019.[87] Higher rates were reported in 1985–1994 than in 1975–1983. There is some debate as to the reasons; one theory is that the trend is the result of improved diagnosis and reporting, since the jump occurred at the same time that MRIs became available widely, and there was no coincident jump in mortality. Central nervous system tumors make up 20–25 percent of cancers in children.[88][82][89]

The average survival rate for all primary brain cancers in children is 74%.[86] Brain cancers are the most common cancer in children under 19, are result in more death in this group than leukemia.[90] Younger people do less well.[91]

The most common brain tumor types in children (0-14) are: pilocytic astrocytoma, malignant glioma, medulloblastoma, neuronal and mixed neuronal-glial tumors, and ependymoma.[92]

In children under 2, about 70% of brain tumors are medulloblastomas, ependymomas, and low-grade gliomas. Less commonly, and seen usually in infants, are teratomas and atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumors.[93] Germ cell tumors, including teratomas, make up just 3% of pediatric primary brain tumors, but the worldwide incidence varies significantly.[94]

In the UK, 429 children aged 14 and under are diagnosed with a brain tumour on average each year, and 563 children and young people under the age of 19 are diagnosed.[95]

Research

Immunotherapy

Cancer immunotherapy is being actively studied. For malignant gliomas no therapy has been shown to improve life expectancy as of 2015.[96]

Vesicular stomatitis virus

In 2000, researchers used the vesicular stomatitis virus, or VSV, to infect and kill cancer cells without affecting healthy cells.[97][98]

Retroviral replicating vectors

Led by Prof. Nori Kasahara, researchers from USC, who are now at UCLA, reported in 2001 the first successful example of applying the use of retroviral replicating vectors towards transducing cell lines derived from solid tumors.[99] Building on this initial work, the researchers applied the technology to in vivo models of cancer and in 2005 reported a long-term survival benefit in an experimental brain tumor animal model.[100] Subsequently, in preparation for human clinical trials, this technology was further developed by Tocagen (a pharmaceutical company primarily focused on brain cancer treatments) as a combination treatment (Toca 511 & Toca FC). This has been under investigation since 2010 in a Phase I/II clinical trial for the potential treatment of recurrent high-grade glioma including glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) and anaplastic astrocytoma. No results have yet been published.[101]

References

- "Adult Brain Tumors Treatment". NCI. 28 February 2014. Archived from the original on 5 July 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- "General Information About Adult Brain Tumors". NCI. 14 April 2014. Archived from the original on 5 July 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- "Chapter 5.16". World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. ISBN 978-9283204299. Archived from the original on 19 September 2016.

- "Cancer of the Brain and Other Nervous System - Cancer Stat Facts". SEER. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- Vos, Theo; et al. (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, et al. (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- Longo DL (2012). "369 Seizures and Epilepsy". Harrison's principles of internal medicine (18th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 3258. ISBN 978-0-07-174887-2.

- "Benign brain tumour (non-cancerous)". nhs.uk. 20 October 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Merrell RT (December 2012). "Brain tumors". Disease-a-Month. 58 (12): 678–89. doi:10.1016/j.disamonth.2012.08.009. PMID 23149521.

- World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 1.3. ISBN 978-9283204299.

- "Brain Tumour Facts 2011" (PDF). Brain Tumour Alliance Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 January 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- "Brain Tumors". Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- "Mood Swings and Cognitive Changes | American Brain Tumor Association". www.abta.org. Archived from the original on 2 August 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- "Coping With Personality & Behavioral Changes". www.brainsciencefoundation.org. Archived from the original on 30 July 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- Kahn K, Finkel A (June 2014). "It IS a tumor -- current review of headache and brain tumor". Current Pain and Headache Reports. 18 (6): 421. doi:10.1007/s11916-014-0421-8. PMID 24760490. S2CID 5820118.

- "Nosebleeds & Headaches: Do You Have Brain Cancer?". Advanced Neurosurgery Associates. 19 November 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- Gregg N, Arber A, Ashkan K, Brazil L, Bhangoo R, Beaney R, et al. (November 2014). "Neurobehavioural changes in patients following brain tumour: patients and relatives perspective" (PDF). Supportive Care in Cancer. 22 (11): 2965–72. doi:10.1007/s00520-014-2291-3. PMID 24865878. S2CID 2072277.

- "Coping With Personality & Behavioral Changes". www.brainsciencefoundation.org. Archived from the original on 30 July 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- "Mood Swings and Cognitive Changes | American Brain Tumor Association". www.abta.org. Archived from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- Warnick R (August 2018). "Brain Tumors: an introduction". Mayfield Brain and Spine Clinic.

- "Changes in Vision - Brain Tumour Symptoms". www.thebraintumourcharity.org. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- "Brain Tumors". Children's Hospital of Wisconsin. 6 March 2019.

- Jones C. "Brain Tumor Symptoms | Miles for Hope | Brain Tumor Foundation". milesforhope.org. Archived from the original on 14 August 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- Beevers Z, Hussain S, Boele FW, Rooney AG (July 2020). "Pharmacological treatment of depression in people with a primary brain tumour". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7: CD006932. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006932.pub4. PMC 7388852. PMID 32678464.

- Krishnatreya M, Kataki AC, Sharma JD, Bhattacharyya M, Nandy P, Hazarika M (2014). "Brief descriptive epidemiology of primary malignant brain tumors from North-East India". Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 15 (22): 9871–3. doi:10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.22.9871. PMID 25520120.

- Kleihues P, Ohgaki H, Eibl RH, Reichel MB, Mariani L, Gehring M, Petersen I, Höll T, von Deimling A, Wiestler OD, Schwab M (1994). "Type and frequency of p53 mutations in tumors of the nervous system and its coverings". Molecular Neuro-oncology and Its Impact on the Clinical Management of Brain Tumors. Recent results in cancer research. Vol. 135. Springer. pp. 25–31. ISBN 978-3540573517.

- Hodgson TS, Nielsen SM, Lesniak MS, Lukas RV (September 2016). "Neurological Management of Von Hippel-Lindau Disease". The Neurologist (Review). 21 (5): 73–8. doi:10.1097/NRL.0000000000000085. PMID 27564075. S2CID 29232748.

- Rogers L, Barani I, Chamberlain M, Kaley TJ, McDermott M, Raizer J, et al. (January 2015). "Meningiomas: knowledge base, treatment outcomes, and uncertainties. A RANO review". Journal of Neurosurgery (Review). 122 (1): 4–23. doi:10.3171/2014.7.JNS131644. PMC 5062955. PMID 25343186.

- Hourigan CS (June 2006). "The molecular basis of coeliac disease". Clinical and Experimental Medicine (Review). 6 (2): 53–9. doi:10.1007/s10238-006-0095-6. PMID 16820991. S2CID 12795861.

- "Brain Cancer Causes, Symptoms, Stages & Life Expectancy". MedicineNet. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- Frei P, Poulsen AH, Johansen C, Olsen JH, Steding-Jessen M, Schüz J (October 2011). "Use of mobile phones and risk of brain tumours: update of Danish cohort study". BMJ. 343: d6387. doi:10.1136/bmj.d6387. PMC 3197791. PMID 22016439.

- "IARC classifies radiofrequency electromagnetic fields as possibly carcinogenic to humans" (PDF). World Health Organization press release N° 208 (Press release). International Agency for Research on Cancer. 31 May 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 June 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- Moore KL, Agur AM, Dalley II AF (September 2017). Clinically oriented anatomy (Eighth ed.). Philadelphia. ISBN 9781496347213. OCLC 978362025.

- "Meningioma Brain Tumor". neurosurgery.ucla.edu. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- "Neurons & Glial Cells | SEER Training". training.seer.cancer.gov. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Farah P, Ondracek A, Chen Y, Wolinsky Y, et al. (November 2013). "CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2006-2010". Neuro-Oncology. 15 (Suppl 2): ii1-56. doi:10.1093/neuonc/not151. PMC 3798196. PMID 24137015.

- "Adult Central Nervous System Tumors Treatment (PDQ®)–Patient Version - National Cancer Institute". www.cancer.gov. 11 May 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Herholz K, Langen KJ, Schiepers C, Mountz JM (November 2012). "Brain tumors". Seminars in Nuclear Medicine. 42 (6): 356–70. doi:10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2012.06.001. PMC 3925448. PMID 23026359.

- Iv M, Yoon BC, Heit JJ, Fischbein N, Wintermark M (January 2018). "Current Clinical State of Advanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Brain Tumor Diagnosis and Follow Up". Seminars in Roentgenology. 53 (1): 45–61. doi:10.1053/j.ro.2017.11.005. PMID 29405955.

- Margiewicz S, Cordova C, Chi AS, Jain R (January 2018). "State of the Art Treatment and Surveillance Imaging of Glioblastomas". Seminars in Roentgenology. 53 (1): 23–36. doi:10.1053/j.ro.2017.11.003. PMID 29405952.

- Watson, Anika (1 January 2007). "Significance of "Atypia" Found on Needle Biopsy of the Breast: Correlation with Surgical Outcome". Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library.

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Necrosis

- Emami Nejad, Asieh; Najafgholian, Simin; Rostami, Alireza; Sistani, Alireza; Shojaeifar, Samaneh; Esparvarinha, Mojgan; Nedaeinia, Reza; Haghjooy Javanmard, Shaghayegh; Taherian, Marjan; Ahmadlou, Mojtaba; Salehi, Rasoul; Sadeghi, Bahman; Manian, Mostafa (December 2021). "The role of hypoxia in the tumor microenvironment and development of cancer stem cell: a novel approach to developing treatment". Cancer Cell International. 21 (1): 62. doi:10.1186/s12935-020-01719-5. PMC 7816485. PMID 33472628.

- Krishna, V (2004). Textbook of Pathology. Chennai: Orient Longman. p. 1029. ISBN 8125026959.

- "What you need to know about brain tumors". National Cancer Institute. Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- Gupta A, Dwivedi T (October 2017). "A Simplified Overview of World Health Organization Classification Update of Central Nervous System Tumors 2016". Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice. 8 (4): 629–641. doi:10.4103/jnrp.jnrp_168_17. PMC 5709890. PMID 29204027.

- Park BJ, Kim HK, Sade B, Lee JH (2009). "Epidemiology". In Lee JH (ed.). Meningiomas: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcome. Springer. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-84882-910-7.

- "Brain Tumors - Classifications, Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatments". www.aans.org. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- "Classifications of Brain Tumors". AANS. American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Metastatic brain tumor

- Frappaz D, Mornex F, Saint-Pierre G, Ranchere-Vince D, Jouvet A, Chassagne-Clement C, et al. (1999). "Bone metastasis of glioblastoma multiforme confirmed by fine needle biopsy". Acta Neurochirurgica. 141 (5): 551–2. doi:10.1007/s007010050342. PMID 10392217. S2CID 40327650.

- "Oligodendroglioma". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- Nicolato A, Gerosa MA, Fina P, Iuzzolino P, Giorgiutti F, Bricolo A (September 1995). "Prognostic factors in low-grade supratentorial astrocytomas: a uni-multivariate statistical analysis in 76 surgically treated adult patients". Surgical Neurology. 44 (3): 208–21, discussion 221–3. doi:10.1016/0090-3019(95)00184-0. PMID 8545771.

- Lecavalier-Barsoum M, Quon H, Abdulkarim B (May 2014). "Adjuvant treatment of anaplastic oligodendrogliomas and oligoastrocytomas". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD007104. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd007104.pub2. PMC 7388823. PMID 24833028.

- Spetzler RF, Sanai N (February 2012). "The quiet revolution: retractorless surgery for complex vascular and skull base lesions". Journal of Neurosurgery. 116 (2): 291–300. doi:10.3171/2011.8.JNS101896. PMID 21981642.

- "Brain & Spinal Tumors: Surgery & Recovery | Advanced Neurosurgery". Advanced Neurosurgery Associates. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- Brennan P (4 August 2008). "Introduction to brain cancer". cliniclog.com. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- Penoncello GP, Gagneur JD, Vora SA, Mrugala MM, Bendok BR, Rong Y (5 February 2022). "Comprehensive commissioning and clinical implementation of GammaTiles STaRT for intracranial brain tumors". Advances in Radiation Oncology. 7 (4): 100910. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2022.100910. ISSN 2452-1094. PMC 9010698. PMID 35434425. S2CID 246623373.

- DeAngelis LM (January 2001). "Brain tumors". The New England Journal of Medicine. 344 (2): 114–23. doi:10.1056/NEJM200101113440207. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 11150363.

- "Radiosurgery treatment comparisons – Cyberknife, Gamma knife, Novalis Tx". Archived from the original on 20 May 2007. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- "Treating secondary brain tumours with WBRT". Cancer Research UK. Archived from the original on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- "Whole Brain Radiation increases risk of learning and memory problems in cancer patients with brain metastases". MD Anderson Cancer Center. Archived from the original on 5 October 2008. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- "Metastatic brain tumors". International RadioSurgery Association. Archived from the original on 16 June 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- Garsa, Adam; Jang, Julie K.; Baxi, Sangita; Chen, Christine; Akinniranye, Olamigoke; Hall, Owen; Larkin, Jody; Motala, Aneesa; Newberry, Sydne; Hempel, Susanne (9 June 2021). "Radiation Therapy for Brain Metasases". doi:10.23970/ahrqepccer242. PMID 34152714. S2CID 236256085.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Khan L, Soliman H, Sahgal A, Perry J, Xu W, Tsao MN (May 2020). "External beam radiation dose escalation for high grade glioma". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5 (8): CD011475. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011475.pub3. PMC 7389526. PMID 32437039.

- Perkins A, Liu G (February 2016). "Primary Brain Tumors in Adults: Diagnosis and Treatment". American Family Physician. 93 (3): 211–217. PMID 26926614.

- "How Our Patients Perform: Glioblastoma Multiforme". UCLA Neuro-Oncology Program. Archived from the original on 9 June 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- Dalvi A. "Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus Causes, Symptoms, Treatment". eMedicineHealth. Emedicinehealth.com. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- "Brain Stem Gliomas in Childhood". Childhoodbraintumor.org. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- Sasmita AO, Wong YP, Ling AP (February 2018). "Biomarkers and therapeutic advances in glioblastoma multiforme". Asia-Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology. 14 (1): 40–51. doi:10.1111/ajco.12756. PMID 28840962.

- "GBM Guide – MGH Brain Tumor Center". Brain.mgh.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on 16 February 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- Tai CK, Kasahara N (January 2008). "Replication-competent retrovirus vectors for cancer gene therapy" (PDF). Frontiers in Bioscience. 13 (13): 3083–95. doi:10.2741/2910. PMID 17981778. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2012.

- Murphy AM, Rabkin SD (April 2013). "Current status of gene therapy for brain tumors". Translational Research. 161 (4): 339–54. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2012.11.003. PMC 3733107. PMID 23246627.

- Ty AU, See SJ, Rao JP, Khoo JB, Wong MC (January 2006). "Oligodendroglial tumor chemotherapy using "decreased-dose-intensity" PCV: a Singapore experience". Neurology. 66 (2): 247–9. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000194211.68164.a0. PMID 16434664. S2CID 31170268. Archived from the original on 20 July 2008.

- "Neurology". Neurology. Archived from the original on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- "Acoustic Neuroma (Vestibular Schwannoma)". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- "UpToDate". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- Bondy ML, Scheurer ME, Malmer B, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Davis FG, Il'yasova D, et al. (October 2008). "Brain tumor epidemiology: consensus from the Brain Tumor Epidemiology Consortium". Cancer. 113 (7 Suppl): 1953–68. doi:10.1002/cncr.23741. PMC 2861559. PMID 18798534.

- "Cancer Stat Facts: Brain and Other Nervous System Cancer". National Cancer Institute. 31 March 2019.

- Jallo GI, Benardete EA (January 2010). "Low-Grade Astrocytoma". Archived from the original on 27 July 2010.

- "CANCERMondial". International Agency for Research on Cancer. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- "What are the key statistics about brain and spinal cord tumors?". American Cancer Society. 1 May 2012. Archived from the original on 2 July 2012.

- "2018 CBTRUS Fact Sheet". Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States. 31 March 2019. Archived from the original on 14 February 2019. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- "Brain, other CNS and intracranial tumours statistics". Cancer Research UK. Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- White British brain tumour patients 'more likely to die in a year' The Guardian

- "Quick Brain Tumor Facts". National Brain Tumor Society. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- "CBTRUS - 2018 CBTRUS Fact Sheet". www.cbtrus.org. Archived from the original on 14 February 2019. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- Hoda SA, Cheng E (6 November 2017). "Robbins Basic Pathology". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 148 (6): 557. doi:10.1093/ajcp/aqx095.

- Chamberlain MC, Kormanik PA (February 1998). "Practical guidelines for the treatment of malignant gliomas". The Western Journal of Medicine. 168 (2): 114–120. PMC 1304839. PMID 9499745.

- "Childhood Brain Cancer Now Leads to More Deaths than Leukemia". Fortune. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- Gurney JG, Smith MA, Bunin GR. "CNS and Miscellaneous Intracranial and Intraspinal Neoplasms" (PDF). SEER Pediatric Monograph. National Cancer Institute. pp. 51–57. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

In the US, approximately 2,200 children and adolescents younger than 20 years of age are diagnosed with malignant central nervous system tumors each year. More than 90 percent of primary CNS malignancies in children are located within the brain.

- "Ependymoma". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- Rood BR. "Infantile Brain Tumors". The Childhood Brain Tumor Foundation. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- Echevarría ME, Fangusaro J, Goldman S (June 2008). "Pediatric central nervous system germ cell tumors: a review". The Oncologist. 13 (6): 690–9. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0037. PMID 18586924.

- "About childhood brain tumours". Archived from the original on 7 August 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- Bloch O (2015). "Immunotherapy for malignant gliomas". Cancer Treatment and Research. 163: 143–158. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-12048-5_9. ISBN 978-3-319-12047-8. PMID 25468230.

- Auer R, Bell JC (January 2012). "Oncolytic viruses: smart therapeutics for smart cancers". Future Oncology. 8 (1): 1–4. doi:10.2217/fon.11.134. PMID 22149027.

- Garber K (March 2006). "China approves world's first oncolytic virus therapy for cancer treatment". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 98 (5): 298–300. doi:10.1093/jnci/djj111. PMID 16507823.

- Logg CR, Tai CK, Logg A, Anderson WF, Kasahara N (May 2001). "A uniquely stable replication-competent retrovirus vector achieves efficient gene delivery in vitro and in solid tumors". Human Gene Therapy. 12 (8): 921–32. doi:10.1089/104303401750195881. PMC 8184367. PMID 11387057.

- Tai CK, Wang WJ, Chen TC, Kasahara N (November 2005). "Single-shot, multicycle suicide gene therapy by replication-competent retrovirus vectors achieves long-term survival benefit in experimental glioma". Molecular Therapy. 12 (5): 842–51. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.03.017. PMC 8185609. PMID 16257382.

- "A Study of a Retroviral Replicating Vector Administered to Subjects With Recurrent Malignant Glioma". Clinical Trials.gov. July 2014. Archived from the original on 26 November 2011.

- van der Pol Y, Mouliere F (October 2019). "Toward the Early Detection of Cancer by Decoding the Epigenetic and Environmental Fingerprints of Cell-Free DNA". Cancer Cell. 36 (4): 350–368. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2019.09.003. PMID 31614115.

- Eibl RH, Schneemann M (October 2021). "Liquid Biopsy and Primary Brain Tumors". Cancers (Basel). 13 (21): 5429. doi:10.3390/cancers13215429. PMC 8582521. PMID 34771592.

External links

- Brain and CNS cancers at Curlie

- Brain tumour information from Cancer Research UK

- Neuro-Oncology: Cancer Management Guidelines

- MedPix Teaching File MR Scans of Primary Brain Lymphoma, etc.