Margaret of Valois

Margaret of Valois (French: Marguerite, 14 May 1553 – 27 March 1615), popularly known as La Reine Margot, was a French princess of the Valois dynasty who became Queen of Navarre by marriage to Henry III of Navarre and then also Queen of France at her husband's 1589 accession to the latter throne as Henry IV.

| Margaret of Valois | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Queen consort of France | |||||

| Tenure | 2 August 1589 – 17 December 1599 | ||||

| Queen consort of Navarre | |||||

| Tenure | 18 August 1572 – 17 December 1599 | ||||

| Born | 14 May 1553 Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France | ||||

| Died | 27 March 1615 (aged 61) Hostel de la Reyne Margueritte, Paris, France | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | |||||

| |||||

| House | Valois | ||||

| Father | Henry II of France | ||||

| Mother | Catherine de' Medici | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

Margaret was the daughter of King Henry II of France and Catherine de' Medici and the sister of Kings Francis II, Charles IX and Henry III. Her union with the King of Navarre, which had been intended to contribute to the reconciliation of Roman Catholics and the Huguenots in France, was tarnished six days after the marriage ceremony by the St Bartholomew's Day massacre and the resumption of the French Wars of Religion. In the conflict between Henry III of France and the Malcontents, she took the side of Francis, Duke of Anjou, her younger brother, which caused Henry to have a deep aversion towards her.

As Queen of Navarre, Margaret also played a pacifying role in the stormy relations between her husband and the French monarchy. Shuttling back and forth between the two courts, she endeavoured to lead a happy conjugal life, but her infertility and the political tensions inherent in the civil conflict led to the end of her marriage. Mistreated by a brother, who was quick to take offence, and being rejected by a fickle and opportunistic husband, she chose the path of opposition in 1585. She took the side of the Catholic League and was forced to live in Auvergne in an exile that lasted 20 years. In 1599, she consented to a "royal divorce",[1] the annulment of the marriage, but only after the payment of a generous compensation.[2]

A well-known woman of letters, an enlightened mind as well as an extremely generous patron, she played a considerable part in the cultural life of the court, especially after her return from exile in 1605. She was a vector of Neoplatonism, which preached the supremacy of platonic love over physical love. During her imprisonment, she took advantage of the time to write her Memoirs, the first woman to have done so. She was one of the most fashionable women of her time and influenced many of Europe's royal courts with her clothing.

After her death, the anecdotes and slanders circulated about her created a legend, which was consolidated around the nickname La Reine Margot, invented by Alexandre Dumas père.[3] They were handed down through the centuries on the myth of a nymphomaniac and incestuous woman.[4][5] In the late 20th and the early 21st centuries, historians have reviewed the extensive chronicles of her life and concluded that many elements of her scandalous reputation stemmed from anti-Valois propaganda[6] and a factionalism that denigrated the participation of women in politics[7] and was created by Bourbon dynasty court historians in the 17th century.[8]

Life

Early life

Margaret of Valois was born on 14 May 1553 at the royal Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, the seventh child and third daughter of Henry II and Catherine de' Medici.[9] Three of her brothers would become kings of France: Francis II, Charles IX and Henry III. Her sister, Elisabeth of Valois, would become the third wife of King Philip II of Spain,[10] and her brother Francis II, married Mary, Queen of Scots.[11]

Her childhood was spent in the French royal nursery of the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye with her sisters Elisabeth and Claude, under the care of Charlotte de Vienne, baronne de Courton, "a wise and virtuous lady greatly attached to the Catholic religion".[12] After her sisters' weddings, Margaret grew up in the Château d'Amboise with her brothers Henry and Francis. During her childhood, her brother Charles IX gave her the nickname of "Margot".[13]

At the French court, she studied grammar, classics, history and Holy Scripture.[14] Margaret learned to speak Italian, Spanish, Latin and Greek in addition to her native French.[15] She was competent also in prose, poetry, horsemanship and dance. She traveled with her family and the court in the grand tour of France (1564–1566). During this period Margaret had direct experience of the dangerous and complex political situation in France, and learned from her mother the art of political mediation.[16]

In 1565, Catherine met with Philip II's chief minister the Duke of Alba at Bayonne in hopes of arranging a marriage between Margaret and Carlos, Prince of Asturias. However, Alba refused any consideration of a dynastic marriage.[17] Other marriage negotiations with Sebastian of Portugal and Archduke Rudolf also did not succeed.

During her teenage years, she and her brother Henry were very close friends. In 1568, leaving court to command the royal armies, he entrusted his 15-year-old sister with the defense of his interests with their mother.[18]

His words inspired me with resolution and powers I did not think myself possessed of before. I had naturally a degree of courage, and, as soon as I recovered from my astonishment, I found I was quite an altered person. His address pleased me, and wrought in me a confidence in myself; and I found I was become of more consequence than I had ever conceived I had been.[19]

Delighted with this mission, she fulfilled it conscientiously, but Henry showed no gratitude upon his return, according to her Memoirs.[20] He had suspicions of a secret romance between Margot and Henry of Guise and their presumptive plan of marriage.[18] When the royal family found this out, Catherine and Charles beat her and sent Henry of Guise away from court.[21] This episode is perhaps at the root of a "lasting brotherly hatred" between Margaret and her brother Henry, as well as the equally lasting cooling of relations with her mother.[22]

Some historians have hinted that the duke was Margaret's lover, but nothing confirms this.[23] In the sixteenth century, a king's daughter had to remain a virgin until her marriage for political reasons. Surely after their marriage she was not faithful to her husband,[24] however, it is difficult to discern what is true or invented about her extramarital affairs. Many have no basis, others were simply platonic. Most of Margaret's alleged adventures are the result of pamphlets that have had to politically discredit her and her family.

The most successful defamation was Le Divorce Satyrique (1607), which described Margaret as a nymphomaniac: nevertheless, these defamatory accusations do not stand up to a careful examination of the sources.

Vermillion wedding

By 1570, Catherine de' Medici was seeking a marriage between Margaret and Henry de Bourbon of Navarre, the leading Huguenot (French Calvinist Protestant). It was hoped this union would strengthen family ties, as the Bourbons were part of the French royal family and the closest relatives to the reigning Valois branch, and end the French Wars of Religion between Catholics and Huguenots.

On 11 April 1572, Margaret was betrothed to Henry. Henry was a few months younger than Margaret, and their initial impressions of each other were favorable. In one of her letters to Henry, his mother Jeanne d'Albret, queen of Navarre, wrote about Margaret: "She has frankly owned to me the favourable impression which she has formed of you. With her beauty and wit, she exercises a great influence over the Queen-Mother and the King, and Messieurs her younger brothers."[25] Jeanne d'Albret died in June 1572, two months after the engagement, and was succeeded on the throne by Henry, so that Margaret became queen of Navarre upon the day of her wedding.

Margaret and Henry, both 19 years of age, were married on 18 August 1572 at Notre Dame cathedral in Paris.[26] The marriage between a Roman Catholic and a Huguenot was controversial. Pope Gregory XIII refused to grant a dispensation for the wedding,[27] and the different faiths of the bridal couple made for an unusual wedding service. The King of Navarre had to remain outside the cathedral during the mass, where his place was taken by Margaret's brother, the Duke of Anjou.[28]

François Eudes de Mézeray, a 17th century historian, invented the anecdote that Margaret was forced to marry the King of Navarre by her brother Charles IX, who pushed down her head as though she were nodding her assent. This was Bourbon propaganda to justify the subsequent annulment of the marriage, 27 years later,[29] part of the myth of the "Reine Margot". Margaret did not mention this in her Memoirs, nor did any of her contemporaries.

I was set out in the most royal manner. I wore a crown on my head with the coët, or regal close dress of ermine, and I blazed in diamonds. My blue-coloured robe had a train to it of four ells in length, which was supported by three princesses. A platform had been raised, some height from the ground, which led from the Bishop's palace to the Church of Notre-Dame. It was huge with cloth of gold; and below it stood the people in throngs to view the procession, stifling with heat. We were received at the church door by the Cardinal de Bourbon, who officiated for that day, and pronounced the nuptial benediction. After this we proceeded on the same platform to the tribune which separates the nave from the choir, where was a double staircase, one leading into the choir, the other through the nave to the church door. The King of Navarre passed by the latter and went out of church.[30]

Just six days later, the Catholic faction assassinated many of the Huguenots gathered in Paris for the wedding (the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre).[32]

In her Memoirs, Margaret remembered that she saved the lives of several prominent Protestants during the massacre by keeping them in her rooms and refusing to admit the assassins.[33] Her eye-witness account of the massacre in Memoirs is the only one from the royal family.[34] These facts inspired Alexandre Dumas for his famous novel La Reine Margot (1845).

After St. Bartholomew's Day, Catherine de' Medici proposed to Margaret that the marriage be annulled, but she replied that this was impossible because she had already had sexual relations with Henry and was "in every sense" his wife. Later she wrote in her Memoirs: "I suspected the design of separating me from my husband was in order to work some mischief against him."[35]

In the libelle Le Réveil-matin des Français, written by an anonymous Huguenot author in 1574 against the royal family, Margaret was accused for the first time of incest with her brother Henry.[36] This libel was another part of the myth of the "Reine Margot".

Malcontent conspiracy

In 1573, Charles IX's fragile mental state and constitution deteriorated further, but the heir presumptive, his brother Henry, was elected king of Poland. Due to Henry's support of suppressing Protestant worship, moderate Catholic lords, called Malcontents, supported a plot to raise Charles' youngest brother, Francis of Alençon, to the throne of France instead. Alençon appeared willing to compromise in religious affairs, making him an appealing option to those tired of violence. Allied with the Protestants, the Malcontents executed several plots to seize power.

Due to her inclination for her two elder brothers, Margaret initially denounced the plot in which her husband was involved, but later turned her coat in the hope of becoming an indispensable link between moderate Catholic supporters and her King of Navarre's Huguenot supporters.[38] She actively participated in the organization of the coup d'état together with her powerful friends Henriette of Nevers and Claude Catherine of Clermont.[39]

In April 1574 the conspiracy was exposed, the leaders of the plot were arrested and decapitated, including Joseph Boniface de La Mole, pretended lover of Margaret.[40] After the failure of the conspiracy, Francis and Henry were held as prisoners at the Château de Vincennes. Margaret wrote a letter pleading for her husband, the Supporting Statement for Henry of Bourbon. She recorded in her Memoirs:

My husband, having no counsellor to assist him, desired me to draw up his defence in such a manner that he might not implicate any person, and, at the same time, clear my brother and himself from any criminality of conduct. With God's help I accomplished this task to his great satisfaction, and to the surprise of the commissioners, who did not expect to find them so well prepared to justify themselves.[41]

After Charles IX's death, at the accession of Henry III of France, Francis and Henry were left at liberty (albeit under surveillance) and even allowed at court, but the new king did not forgive or forget Margaret's betrayal.

A divided family

Relations between Henry and Margaret deteriorated. Margaret did not get pregnant even though Henry continued to pay his marital debt assiduously. But he had many mistresses and openly deceived Margaret with Charlotte de Sauve, member of Queen-Mother's notorious "Flying Squadron."[42] Charlotte also provoked a quarrel between Alençon and Navarre, both her lovers, spoiling Margaret's attempt at forming an alliance between her husband and youngest brother.[43]

This episode may give the impression that despite frequent infidelity, the marriage was a solid political alliance. In reality, Henry only approached his wife when it served his interests, and did not hesitate to abandon her if it did not. For her part, Margaret might have availed herself of the absence of jealousy of her husband to take a lover in the person of the famous Bussy d'Amboise.[40]

Alençon and Navarre finally managed to escape, one in September 1575 and the other in 1576.[28] Henry did not even warn his wife of his departure. Margaret found herself confined to her chambers in the Louvre, under suspicion as her husband's accomplice. She wrote in her Memoirs:

Besides, I had found a secret pleasure, during my confinement, from the perusal of good books, to which I had given myself up with a delight I never before experienced. [...] My captivity and its consequent solitude afforded me the double advantage of exciting a passion for study, and an inclination for devotion, advantages I had never experienced during the vanities and splendour of my prosperity.[44]

Alençon, who allied himself with the Huguenots, took up arms and refused to negotiate until his sister was set free. She was therefore released and assisted her mother in the peace talks. They led to a text extremely beneficial to the Protestants and to Alençon: the Edict of Beaulieu.[45]

Henry of Navarre, who had once again converted to the Protestant faith, sought to have Margaret join him in his kingdom of Navarre. During this conflict, they reconciled to the point that she reported pertinent information from the court in her letters.[46] But Catherine de' Medici and Henry III refused to release her to her husband, fearing that Margaret would become a hostage in the hands of the Huguenots or that she would act to strengthen the alliance between Navarre and Alençon.[47] However, Catherine was persuaded that Henry of Navarre could potentially change religion yet again, and used her daughter as bait to attract him to Paris.

Diplomatic mission in Flanders

In 1577, Margaret asked permission to go on a mission in the south of the Netherlands on behalf of her younger brother Francis d'Alençon. The Flemings, who had rebelled against Spanish rule in 1576, seemed willing to offer a throne to a foreign prince who was tolerant and willing to provide them with the diplomatic and military forces necessary to protect their independence. Henry III accepted the proposal of his sister because he would finally release the inconvenient duke of Alençon.

On the pretext of a bath in Spa thermal waters, Margaret left Paris with her court. She devoted two months to her mission: at every stage of the journey, during brilliant receptions, the queen of Navarre was entertained with gentlemen hostile to Spain and, while praising his brother, she tried to persuade them to join him.[48] She also met the governor of the Netherlands, Don Juan of Austria, with whom he had a friendly meeting in Namur.[49] Almost one quarter of her Memoirs are devoted to this mission. For Margaret, returning to France was dangerous due to the risk that the Spanish would capture her.

At the end, despite the contacts Margaret had found, the duke d'Alençon was incapable of defeating the Spanish army.[50]

After reporting her mission to her younger brother, Margaret returned to the court. The fighting multiplied between Henry III's mignons and Alençon's supporters, in the forefront of which Bussy d'Amboise, a lover of Margaret.[51] In 1578 Alençon asked to be absent. But Henry III saw in it the proof of his participation in a conspiracy: he had him arrested in the middle of the night, and kept him in his room, where Margaret joined him. As for Bussy, he was taken to the Bastille. A few days later, Francis fled again, thanks to a rope thrown out of his sister's window.[52]

Court of Nérac

_by_Nicholas_Hilliard.jpg.webp)

Shortly afterwards, Margaret, who denied any participation in this escape, finally got permission to join her husband. Catherine also saw the years pass and still had no heir. She hoped for a new wedding and invited her son-in-law to act as a good husband. Perhaps Henry III and the Queen-Mother also hoped that Margaret could play a conciliation role in the troubled provinces of the southwest.[53]

For her return with her husband, Margaret was accompanied by her mother and her chancellor, a renowned humanist, magistrate and poet, Guy Du Faur de Pibrac.[54] This journey was an opportunity for entering the cities crossed, a way of forging closer ties with the reigning family. At the end of their journey, they finally found the King of Navarre. Catherine and her son-in-law agreed on the modalities of the execution of the last edict of pacification – the object of the Nérac conference in 1579. Then, the Queen-Mother returned to Paris.

After her departure, the spouses stayed briefly in Pau where Margaret suffered from the prohibition of Catholic worship.[55] They then settled in Nérac, capital of the Albret, which was part of the kingdom of France and where the religious regulations and intolerance in force in Béarn did not apply:

Our residence, for the most part of the time I have mentioned, was Nérac, where our Court was so brilliant that we had no cause to regret our absence from the Court of France. We had with us the Princesse de Navarre, my husband's sister; there were besides a number of ladies belonging to myself. The King my husband was attended by a numerous body of lords and gentlemen, all as gallant persons as I have seen in any Court; and we had only to lament that they were Huguenots. [...] Sometimes we took a walk in the park on the banks of the river, bordered by an avenue of trees three thousand yards in length. The rest of the day was passed in innocent amusements; and in the afternoon, or at night, we commonly had a ball.[56]

Queen Margaret worked to create a refined court.[57] She was indeed forming a true literary academy. Besides Agrippa d'Aubigné, Navarre's companion in arms, and Pibrac, the poet Saluste du Bartas or Montaigne[40] frequented the court. Margaret had many exchanges with the author of the Essays.

The court of Nérac became especially famous for the amorous adventures that occurred there, to the point of having inspired Shakespeare's Love's Labour's Lost.[58] Margaret had an affair with one of the most illustrious companions of her husband, the Vicomte de Turenne. Henry of Navarre, on his side, endeavored to conquer all the maids of honor who accompanied his wife. In 1579, a religious war, later called the "Lovers' War", broke out between the Huguenots and King Henry III.[59]

The conflict was provoked by the misapplication of the last edict of pacification and by a conflict between Navarre and the lieutenant-general of the king in Guyenne, a province in which Henry was governor.[60] During the conflict, Margaret rather took the side of her husband.[61] It lasted briefly (1579–1580), thanks in part to the queen of Navarre who suggested calling her brother Alençon to lead the negotiations. They were rapid and culminated in the peace of Fleix.[62]

It is then that Margaret fell in love with the grand equerry of her brother, Jacques de Harlay, lord of Champvallon.[63] The letters she addressed to him illustrate her conception of love, imprinted with Neoplatonism. It was a matter of privileging the union of minds with that of the bodies – which did not mean that Margaret did not appreciate physical love[64] – to bring about the fusion of souls.

After the departure of Alençon, the situation of Margaret deteriorated. One of her ladies-in-waiting, Françoise de Montmorency-Fosseux a 14-year-old girl known as La Belle Fosseuse, was conducting a passionate affair with the King of Navarre and became pregnant. Margaret proposed banishing her rival from court, but La Belle Fosseuse screamed that she would refuse to cooperate. She never ceased to incite Henry against his wife, hoping perhaps to be married to him. "From that moment until the hour of [his mistress's] delivery, which was a few months after, [my husband] never spoke to me. [...] We slept in separate beds in the same chamber, and had done so for some time", remembered Margaret.[65]

Françoise finally gave birth to a daughter, but the child was stillborn. "It pleased God that she should bring forth a daughter since dead" wrote the queen in her Memoirs.[66]

Scandal in Paris

In 1582, Margaret returned to Paris. She had failed to give her husband an heir, which would have strengthened her position. However, the real reasons for her departure were obscure. No doubt she wanted to escape from an atmosphere that became hostile, perhaps also to approach her lover Champvallon, or to support her younger brother Alençon. Moreover, King Henry III and the Queen-Mother urged her to return, hoping thus to attract the King of Navarre to the court of France.[67]

Queen Margaret was initially well received by her brother, the King. Margaret maintained an active correspondence with her husband and tried to convince him to join her in Paris. But Henry of Navarre was not persuaded, and a rupturing of their relationship occurred when Margaret forced La Belle Fousseuse from her service on the order of the Queen-Mother.[68] After this new break with her husband, from November 1582 to August 1583, the queen of Navarre resumed the relationship with Champvallon, who had returned to Paris.[64]

In the meantime, the relationship between Margaret and her brother Henry III had become very strained. While the King alternated between a dissolute life and crises of mysticism, Margaret encouraged mockery against his morals and she made enemies of two of his chief mignons the Duke of Epernon and the Duke of Joyeuse, who retaliated by circulating very injurious reports about her private life.[69] In addition, Margaret encouraged Alençon to continue his expedition to the Netherlands, which King Henry III wished to interrupt, fearing a war with Spain.[70]

When she fell sick in June 1583, rumors claimed that she was pregnant by Champvallon.[71] Henri III was soon displeased by her reputation and behavior and expelled her from the court, an unprecedented and humiliating measure that scandalized Europe. The Queen's court was stopped by Henry III's guards and some of her servants were arrested and interrogated by the King himself, especially about the possible birth of a bastard child by Jacques de Harlay or an abortion.[72]

Moreover, warned of the rumors, the King of Navarre refused to receive his wife. He gave Henry III embarrassed explanations, then compensations.[73] The Queen of Navarre remained for eight months in uncertainty between the French and Navarre courts, waiting for the negotiations to be concluded. The Huguenot warlords found there the casus belli they were waiting for and Navarre took advantage of it to seize Mont-de-Marsan, which Henry III agreed to cede to him to close the incident.[74]

On 13 April 1584, after long negotiations, Margaret was allowed to return to her husband's court in Navarre, but she received an icy reception.[73] The situation got worse. In June 1584, her brother Francis died and she missed her most valuable ally.[75] With Alençon's death, Henry of Navarre became heir presumptive to the French throne, and he was under increased pressure to produce an heir.[76] In 1585, his new lover Diane d'Andouins, nicknamed La Belle Corisande, pressed the King of Navarre to repudiate Margaret, hoping to be married to him.

Rebellion and exile

In 1585, in an unprecedented gesture for a Queen of the sixteenth century, Margaret abandoned her husband.[77] She rallied the Catholic League, which united as well the intransigent Catholics with the people hostile to the policy of her family and her husband.[73] Determined to overcome her difficulties, Margaret masterminded a coup d'état and seized power over Agen, one of her appanages. The Queen of Navarre spent several months fortifying the city. Recruiting troops, she sent them to the assault of the cities around Agen.

But, tired of the Queen's demands, the Agenais revolted and agreed with the lieutenant of Henry III.[78] With the arrival of royal troops, Margaret had to flee precipitously. Refusing her mother's pleas that she move to a royal manor, she retreated to her lofty and impregnable fortress of Carlat with Jean de Lard de Galard, seigneur d'Aubiac, her pretended lover, whom she appointed captain of her guards.[79]

After a year, probably due to the approach of royal troops, Margaret took refuge in the castle of Ibois, a little to the north of Auvergne, as proposed to her by her mother.[80] But she found herself besieged by the royal troops who seized the fortress. She waited nearly a month for a decision on her fate.

On 13 October 1586, Margaret was imprisoned by her brother Henry III in the castle of Usson, in Auvergne. D'Aubiac was executed, despite Catherine de' Medici's wish, in front of Margaret.[81] Margaret assumed she was going to die and in a "farewell" letter to the Queen-Mother, she asked that after her execution a post-mortem be held to prove that she was not, despite gossip, pregnant with d'Aubiac's child.

But suddenly, her gaoler, the Marquis de Canillac, switched from the royal side in the civil war to that of the Catholic League and released her in early 1587.[82] Rumors at the court of France reported that she seduced him, but most probably he was bought by her.[83] Her freedom suited the League perfectly: her continued existence guaranteed that Henry of Navarre would remain without an heir.

Despite obtaining her freedom, Margaret decided to stay in the castle of Usson, where she spent eighteen years. Of her life in Usson, there is very little reliable information, so a lot of legends have gathered around it.[84] Here, she learned of her mother's death and of her brother Henry III's assassination in 1589. Her husband, Henry of Navarre, became King of France under the name of Henri IV. He was, however, not accepted by most of the Catholic population until he converted four years later.[85]

During this time, Margaret was able to train, as she had done at Nérac, a new court of intellectuals, musicians and writers. She restored the castle and committed her time to reading many works, especially religious and esoteric ones. Even her financial condition improved when her sister-in-law, Elisabeth of Austria, with whom she had always had good relations, began sending her half of her income.[86]

In 1594, Margaret received a letter from her friend Pierre de Bourdeille, known as Brantôme, with whom she was in contact, a panegyric entitled Discours sur la Reine de France et de Navarre. In response to the poet's work, which contained several mistakes and false rumors about her, she wrote her Memoirs. She was the first woman to have done so.[87]

I have been induced to undertake writing my Memoirs the more from five or six observations which I have had occasion to make upon your work, as you appear to have been misinformed respecting certain particulars. For example, in that part where mention is made of Pau, and of my journey in France; likewise where you speak of the late Maréchal de Biron, of Agen, and of the sally of the Marquis de Canillac from that place.[88]

Her work was dedicated to Brantôme, and it consisted of an autobiography from her infancy to 1582. The Memoirs were published posthumously in 1628.[15] Queen Margaret was also visited by writers, beginning with the faithful Brantôme, but also Honoré d'Urfé, who was no doubt inspired by Margaret to create the character of Galathee in L'Astrée, and Joseph Scaliger, who visited Usson in 1599.[89]

Reconciliation with Henry and annulment of marriage

By 1593, Henry IV first proposed to Margaret an annulment of their marriage.[90] Margaret resumed contact with him to try to improve her financial situation. Her infertility was proven, but she knew that the new King needed a legitimate son to consolidate his power. For this, he needed the support of his wife because he wished to marry again.

The negotiations began after the return of peace and Henry IV's return to Catholicism. To support the invalidity of the marriage with the pope, the King and Margaret put forward the infertility of the couple, their consanguinity, and the formal defects of the marriage.[91] During the talks, the queen’s financial situation improved, but she was displeased at the idea of Henry marrying his mistress, Gabrielle d'Estrees, mother of his son, César, who was legitimized in 1595, and refused to endorse what she considered to be a dishonorable remarriage: "It is repugnant to me to put in my place a woman of such low extraction and of so impure a life as the one about whom rumor speaks."[92]

She stopped the negotiations, but after the providential death of Gabrielle from eclampsia,[93] Margaret returned to her demand for reasons of conscience, in exchange for strong financial compensation and the right to retain the use of her royal title. During the trial, many witnesses reported the fake saying that Margaret had been forced by her mother and brother Charles IX to marry Henry.[94] Clement VIII pronounced the cancellation bull on 24 October 1599. Later, on 17 December 1599, the Archbishop of Arles pronounced the annulment of Henry's marriage to Margaret of Valois.[95] A year later Henry IV married Marie de' Medici, who nine months later gave him a son.

Following the annulment of their marriage, positive relations between the two former spouses continued. After twenty years of exile, Margaret entered the good graces of the King of France.[96] Her case was not foreseen by custom, but her new position allowed her to receive visitors at Usson who were charmed by the cultural quality of this "new Parnassus" and the generosity of their hostess.

On the other hand, well-established in the Auvergne and well-informed, she did not fail to spot the schemes of the Count of Auvergne, bastard son of King Charles IX of France and uterine brother (half-brother with the same mother) of Henriette d'Entragues – a mistress evicted by King Henry IV. Duly informed, in 1604 the King ordered the capture of the conspirator and the confiscation of all his property. Queen Margaret ought in her time to have inherited from Auvergne a property belonging to her mother, Catherine de' Medici, who had disinherited her from her brother Henry III's schemes for the benefit of this ally.[97] Margaret initiated a long trial and the King allowed her to return to Paris to manage her legal case.[98]

Last years in Paris

In 1605, after nineteen years in Usson, Margaret made her return to the capital. She impressed the Parisians for her appearance: her skin was red and raw, she wore an extravagant blonde wig and her clothes were twenty years out of fashion, but despite this she equally won the affection of the people.[99] Even if she had changed little - at least as far as her tastes were concerned - she became "horribly stout", according to Tallemant des Réaux.[100]

In Paris Queen Margaret established herself as a mentor of the arts and benefactress of the poor. She was also now very devout and Vincent de Paul was her chaplain.[101]

In 1606, she managed to win the lawsuit against her nephew and gained her entire maternal inheritance. After this, Margaret named as her heir the dauphin Louis. This was an extremely important political move for the Bourbon family, as it made official the dynastic transition between the Valois family, of which Queen Margaret was the last legitimate descendant, and that of Bourbon dynasty, just settled on the throne of France.[102]

It strengthened the friendship that had been created with Queen Marie de' Medici to delegitimize the claims of Henriette d'Entragues, sister of Charles of Valois and lover of Henry IV, who claimed that her son was the legitimate heir due to the King's promise of marriage. Margaret often helped plan events at court and nurtured the children of Henry IV and Marie.[103] In 1608, at the birth of Prince Gaston of France, future Duke of Orleans, Queen Margaret was chosen by the King himself to be the godmother.[104]

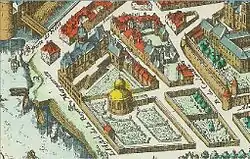

She settled her household on the Left Bank of the Seine in the Hostel de la Reyne Margueritte, which is illustrated in Merian's 1615 plan of Paris; the hostel was built for her to designs by Jean Bullant in 1609.[105] The palace became a Parisian political and intellectual center. Queen Margaret gave brilliant receptions with theatrical performances and ballets that lasted until night and had great patrons; she also opened a literary lounge where she organized a company of philosophers, poets and scholars (among them Marie de Gournay, Philippe Desportes, François Maynard, Etienne Pasquier, Théophile de Viau).[106]

On 13 May 1610, Queen Margaret attended Marie's coronation at Saint Denis. The following day, Henri IV was assassinated by the fanatic monk François Ravaillac and Marie de' Medici obtained the regency for their minor child. The regent was entrusted with various diplomatic roles, including the reception of foreign ambassadors at court, the celebrations for the future marriage of Louis XIII and in the Estates General in 1614, in which Margaret was charged with negotiating with clergy representatives. This was her last public assignment.[107]

Also in 1614, she entered the woman question (querelle des femmes) in response to The Flowers of Moral Secrets, a text that she considered to be misogynist, written by the Jesuit father Loryot. She wrote The Learned and Subtle Discourse in which she affirmed the superiority of the woman over man, arguing that God in the creation of the world started from the lower creatures up to the superiors and the woman is the last created creature, not even from the mud, like Adam, but from a rib. Furthermore, the delicacy of the aesthetic forms of women reflects only their perfection. For Queen Margaret, the world is not "made for man and man for God, but rather the world is made for man, man made for woman, and woman made for God".[108]

Early in March 1615, Margaret became dangerously ill. She died in her Hostel de la Reyne Marguerite, on 27 March 1615. "On March 27 – wrote Paul Phélypeaux de Pontchartrain – there died in Paris, Queen Margaret, the sole survivor of the race of Valois; a princess full of kindness and good intentions for the welfare and repose of the State, and who was her only enemy. She was deeply regretted".[109]

Queen Margaret was buried in the funerary chapel of the Valois in the Basilica of St. Denis.[110] Her casket has disappeared and it is not known whether it was removed and transferred when work was done at the chapel, or destroyed during the French Revolution.[111]

Legacy

Myth of Queen Margot

Queen Margaret's life is obscured by the legend of "Queen Margot", the myth of a nymphomaniac and incestuous woman in a damned family. Many slanders were spread throughout the life of the princess, but those in The Satiric Divorce (Le Divorce Satyrique), a pamphlet probably written by Théodore Agrippa d'Aubigné against Henry IV, were the ones that were most successful by being subsequently handed down as if they had been established.[112]

By 1630, after the Day of the Dupes, Cardinal Richelieu and his historians initiated a campaign against Marie de' Medici, and the systematic discrediting of all women and their political role revived Margaret's black legend.[113]

It is in the 19th century that the myth of Queen Margot was born. The nickname was invented by Alexandre Dumas père,[114] who titled his first novel in the Valois Trilogy: La Reine Margot (1845). He descried in the novel the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre and the intrigues of subsequent courtiers. The historian Jules Michelet instead exploited the figure of Princess Valois to denounce the "depravity" of the Ancien Régime.

Between the 19th and the 20th centuries, some historians such as Count Léo de Saint-Poincy sought to rehabilitate the figure of the Queen by trying to discern the scandals from reality and depicting her as a woman who challenged the turmoil of the civil war. To some modern historians, it appears that Margaret of Valois had never felt less than her brothers and even wanted to participate in the affairs of the kingdom. They have also addressed the political behavior of Margaret, in addition to her private life.[114] However, those studies remained marginal and did not affect official texts.

Only since the 1990s have some historians, such as Éliane Viennot,[115] Robert J. Sealy[116] and Kathleen Wellman, contributed to rehabilitating the image of the last Valois and to distinguishing between the historical figure of Margaret of Valois and the legend of Queen Margot. However, literary works and cinematographic works, such as La Reine Margot by Patrice Chéreau, have continued to perpetuate the image of an obscene and lustful woman.

In literature and fiction

The 1845 novel of Alexandre Dumas, père, La Reine Margot, is a fictionalised account of the events surrounding Margaret's marriage to Henry of Navarre.[117] The novel was adapted into film three times, with the 1994 version nominated for the Academy Award for Costume Design (Margaret was played by Isabelle Adjani).[118]

The main action of William Shakespeare's early comedy Love's Labour's Lost (1594–1595) is possibly based on an attempt at reconciliation made in 1578 between Margaret and Henry.[119]

Margaret appears in Jean Plaidy's novel, Myself, My Enemy (ISBN 9780399128776) a fictional memoir of Queen Henrietta Maria, consort of King Charles I of England. She also features in Plaidy's Catherine de Medici trilogy which focuses on her mother, Catherine de' Medici, mostly in the second book The Italian Woman (ISBN 9781451686524), and also in the third book, Queen Jezebel (ISBN 9781451686548).[120] Sophie Perinot's 2015 novel Médicis Daughter (ISBN 9781250072092) covers Margaret's adolescence and the early days of her marriage.

Margaret of Valois also has a major role in the Meyerbeer opera Les Huguenots.[121] That was one of the signature roles of the Australian soprano Joan Sutherland, who performed it for her farewell performance for the Australian Opera in 1990.[122] She also appears in the opera comique Le pré aux clercs, by Ferdinand Herold.

Margot was portrayed by Rebecca Liddiard in the series finale of the television series Reign.[123]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Margaret of Valois | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Henry IV of France's wives and mistresses

- Augusta Leigh

- Marguerite de Ravalet

References

- "Leur divorce fut royal", wrote the historian Anaïs Bazin, cited by Sainte-Beuve in his 1852 article on "La Reine Marguerite, ses mémoires et ses lettres" in vol. 6 of the Causeries du lundi (4th ed., Garnier Frères, n.d., p. 198).

- Wellman, Queens and Mistresses of Renaissance France, p. 306.

- Moisan, L'exil auvergnat de Marguerite de Valois (la reine Margot), p. 7, p. 195.

- Moshe Sluhovsky, «History as Voyeurism: from Marguerite De Valois to La Reine Margot», Rethinking History, 2000.

- Merki, La Reine Margot et la fin des Valois, pp. 369-383

- Sealy, The Myth of the Reine Margot, pp. 23-28.

- Moisan, pp. 192-195.

- Casanova, Regine per caso, pp. 103-107.

- Wellman, p. 277.

- Kamen 1997, p. 74.

- Knecht 1988, p. 207-208.

- Williams, Queen Margot, p. 3.

- Bruno Méniel, Éthiques et formes littéraires à la Renaissance, H. Champion, 2006, p. 89.

- Williams, p. 11.

- Pidduck, La Reine Margot, p. 19.

- Moisan, pp. 14–17.

- Knecht, The French Wars of Religion, 1559–1598, p. 39.

- Moisan, p. 18.

- Memoirs, p. 43.

- Mourgue, p. 10; Williams, pp. 24–25.

- Wellman, p. 280.

- Garrisson, Marguerite de Valois, p. 39–43.

- Williams, p. 39.

- Craveri, p. 69.

- Quoted in Williams, p. 60.

- Pitts, Henri IV of France: His Reign and Age, p. 60.

- Boucher, Deux épouses et reines à la fin du XVIe siècle, p. 25.

- R.J. Knecht, Catherine de' Medici, p. 153.

- Viennot, Marguerite de Valois. “La reine Margot”, p. 357.

- Memoirs, pp. 55-56; Boucher, p. 22.

- Knecht, The French religious wars: 1562–1598, pp. 51–52.

- Pitts, pp. 61–65.

- Memoirs, pp. 65–67.

- Craveri, p. 65.

- Memoirs, p. 67.

- Viennot, Marguerite de Valois, p. 313; Moisan, p. 192; Pidduck, p. 18.

- Wellman, p. 278.

- Memoirs, pp. 68–9.

- Boucher, p. 191.

- Moisan, p. 20.

- Memoirs, p. 70.

- Buisseret, Henry IV, King of France, p. 9

- Memoirs, p. 72.

- Memoirs, p. 112–3.

- Holt, p. 105–6; Knecht, Catherine de' Medici, p. 186

- Memoirs, p. 108.

- Memoirs, p. 115.

- Pitts, pp. 81–82.

- Williams, pp. 222–224.

- Holt, The French Wars of Religion, 1562–1629, pp. 121–122.

- Memoirs, p. 175.

- Memoirs, p. 198.

- Pitts, p. 82.

- Williams, p. 247.

- Williams, pp. 259–60.

- Memoirs, pp. 210–211.

- Viennot, Marguerite de Valois, p. 121.

- Craveri, p. 79.

- Although inaccurate, this name for the war relates to a series of scandals at the Navarre court and to the notion that Henry of Navarre took up arms in response to jibes about his love life from the French court.

- Memoirs, p. 211.

- Memoirs, p. 214.

- Memoirs, p. 221.

- Moisan, p. 23.

- Moisan, p. 24.

- Memoirs, pp. 224–228.

- Memoirs, p. 229.

- Moisan, pp. 20–21.

- Williams, pp. 283–285.

- Williams, pp. 289–290; Moisan, p. 25.

- Craveri, pp. 80–81.

- Moisan, pp. 24–25.

- Moisan, p. 27.

- Craveri, p. 80.

- Williams, pp. 302–303.

- Chamberlin, Marguerite of Navarre, p. 240.

- Moisan, p. 29.

- Moisan, p. 30.

- Viennot, Marguerite de Valois, p. 307; Boucher, p. 388

- Moisan, p. 58.

- Williams, p. 329.

- Knecht, Catherine de' Medici, pp. 254–55; Henry III wrote to his secretary Villeroy: "The Queen my mother wishes me to hang Obyac [sic] in the presence of this miserable creature [Margaret] in the courtyard of the Château d'Usson"

- Sealy, p. 125.

- Viennot, Marguerite de Valois, pp. 234–235.

- Williams, p. 337.

- "Henry IV". Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- Williams, pp. 341–342.

- Craveri, Amanti e regine, pp. 81–82.

- Memoirs, p. 29.

- Moisan, p. 144; Boucher, p. 240.

- Buisseret, p. 77.

- Éliane Viennot, « Autour d'un « démariage » célèbre : dix lettres inédites de Marguerite de Valois» in Bulletin de l'Association d'étude sur l'humanisme, la réforme et la renaissance, 1996, vol. 43, n°43, p.5-24.

- Quoted in Williams, pp. 354–355.

- Buisseret, p. 77–78.

- Boucher, p.378–383.

- Buisseret, p. 79.

- Craveri, pp. 82–83.

- Williams, pp. 361–363.

- Williams, p. 366.

- Wellman, p. 308.

- Williams, p. 369.

- Castarède, La triple vie de la reine Margot, p. 12.

- Craveri, p. 85.

- Pitts, p. 270.

- Williams, p. 377.

- It was eventually demolished and partially replaced in 1640 by the Hôtel de La Rochefoucauld. Currently the building no longer exists. Now is located the École National Supériore des Beaux Arts. "Histoire de la rue par les cartes"

- Craveri, p. 83.

- Williams, p. 385.

- Craveri, p. 83; Wellman, p. 312-314.

- Quoted in Williams, p. 385.

- Castarède, pp. 236–237.

- Castarède, p. 237.

- Moisan, p. 7; Casanova, p. 104.

- Casanova, p. 105.

- Moisan, p. 7.

- Casanova, p. 103.

- Robert J. Sealy suggest that many of Margaret's supposed sexual partners, such as Auvergnate barons, Lignerac, Aubiac and Canillac, were not her lovers but only political allies (Sealy, p. 121).

- Coward, D. (1997). Note on the Text. In A. Dumas, La Reine Margot (p. xxv). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Queen Margot at AllMovie

- Dobson, M. and Wells, S. The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare, Oxford University Press, 2001, p. 264

- Johnson, Arleigh (August 2013). "Queen Jezebel by Jean Plaidy". The Historical Novels Review. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- Loomis, George (21 June 2011). "'Les Huguenots,' Making Operatic History Again". New York Times. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- "Australia." The 1991 World Book Year Book. Chicago:World Book, Inc., 1991. ISBN 0-7166-0491-4.

- "Reign – All It Cost Her". Starry Constellation Magazine. 22 June 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- Anselme, pp. 210–211

- Anselme, pp. 131–132

- Anselme, pp. 126–128

- Tomas, p. 7

- Whale, p. 43

Bibliography

- Anselme de Sainte-Marie, Père (1726). Histoire généalogique et chronologique de la maison royale de France [Genealogical and chronological history of the royal house of France] (in French). Vol. 1 (3rd ed.). Paris: La compagnie des libraires.

- Pierre de Bourdeille, seigneur de Brantôme, Illustrious Dames of the Court of the Valois Kings. Translated by Katharine Prescott Wormeley. New York: Lamb, 1912. OCLC 347527.

- Jacqueline Boucher, Deux épouses et reines à la fin du XVIe siècle: Louise de Lorraine et Marguerite de France, Saint-Étienne, Presses universitaires de Saint-Étienne, 1998, ISBN 978-2862720807. (in French)

- David Buisseret, Henry IV, King of France, New York: Routledge, 1990. ISBN 0-04-445635-2.

- Cesarina Casanova, Regine per caso. Donne al governo in età moderna, Bari, Editori Laterza, 2014. ISBN 978-88-581-0991-5. (in Italian)

- Jean Castarède, La triple vie de la reine Margot, Éditions France-Empire, Paris, 1992, ISBN 2-7048-0708-6. (in French)

- Benedetta Craveri, Amanti e regine. Il potere delle donne, Milano, Adelphi, 2008, ISBN 978-88-459-2302-9. (in Italian)

- Janine Garrisson, Marguerite de Valois, Paris, Fayard, 1994. (in French)

- Charlotte Haldane, Queen of Hearts: Marguerite of Valois, 1553–1615, London: Constable, 1968.

- Marc P. Holt, The French Wars of Religion, 1562–1629, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Kamen, Henry (1997). Philip of Spain. Yale University Press.

- Robert J. Knecht, The French Wars of Religion, 1559–1598, 1989

- Robert J. Knecht, Catherine de' Medici. London and New York: Longman, 1998. ISBN 0-582-08241-2.

- Knecht, Robert J. (1988). Henry II, King of France 1547-1559. Duke University Press.

- Michel Moisan, L'exil auvergnat de Marguerite de Valois (la reine Margot) : Carlat-Usson, 1585–1605, Editions Creer, 1999. (in French)

- Alain Mourgue, Margot, reine d'Usson, Editions Le Manuscrit, 2008. (in French)

- Julianne Pidduck, La Reine Margot, London and New York, I.B. Tauris, 2005. ISBN 1-84511-100-1.

- Vincent J. Pitts, Henri IV of France; His Reign and Age, JHU Press, 2009.

- Robert J. Sealy, The Myth of Reine Margot: Toward the Elimination of a Legend, Peter Lang Publishing, 1994.

- Nicola Mary Sutherland, The Massacre of St. Bartholomew and the European conflict, 1559–1572 (1973)

- Natalie R. Tomas, The Medici Women: Gender and Power in Renaissance Florence. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2003. ISBN 0-7546-0777-1.

- Éliane Viennot, Marguerite de Valois. La reine Margot, Paris, Perrin, 2005 ISBN 2-262-02377-8. (in French)

- Éliane Viennot, Margherita di Valois. La vera storia della regina Margot, 1994, Mondadori, Milano ISBN 88-04-37694-5. (in Italian)

- Kathleen Wellman, Queens and Mistresses of Renaissance France, 2013

- Whale, Winifred Stephens (1914). The La Trémoille family. Boston, Houghton Mifflin. p. 43.

- Hugh Noel Williams, Queen Margot, wife of Henry of Navarre, New York, Harper and brothers, 1907.

- Marguerite of Valois, Memoirs of Marguerite de Valois, written by herself, New York, Merrill & Baker, 1800

External links

Media related to Marguerite de Valois at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Marguerite de Valois at Wikimedia Commons- Works by Margaret of Valois at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Margaret of Valois at Internet Archive

- Memoirs of Marguerite de Valois (in English):

- New York, Charles Scribners, 1892, translated by Violet Fane. View at Google Books .

- Boston, L. C. Page, 1899 . Vew at Project Gutenberg or Google Books .

- Image at cybersybils.net

- Image at pandemonium.tiscali.de