Mary, mother of Jesus

Mary[lower-alpha 3] was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth,[4] the wife of Joseph, and the mother of Jesus. She is a central figure of Christianity, the world's largest religion. The New Testament of the Bible provides with the earliest accounts of Mary, mainly in the canonical Gospels. She is described as a young virgin[lower-alpha 4] who was chosen by Yahweh to conceive Jesus through the Holy Spirit. After giving birth to Jesus in Bethlehem, she raised him in the city of Nazareth, in Galilee.

Mary | |

|---|---|

Our Lady of Sorrows by Giovanni Battista Salvi da Sassoferrato, 17th century | |

| Born | c. 18 BC[lower-alpha 1] |

| Died | after c. 30/33 AD |

| Spouse | Joseph |

| Children | Jesus[lower-alpha 2] |

| Parent(s) | according to some apocryphal writings Joachim and Anne |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Mother of Jesus |

| Chronology |

|---|

|

| Marian perspectives |

|

| Catholic Mariology |

|

| Marian dogmas |

|

| Mary in culture |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Mary has been venerated since early Christianity,[8][9] and is considered by millions to be the holiest and greatest saint for being chosen by God to bear and raise Jesus. The Eastern and Oriental Orthodox, Catholic, Anglican, and Lutheran churches believe that Mary, as mother of Jesus, is the Theotokos (Mother of God; Θεοτόκος). There is significant diversity in the Marian beliefs and devotional practices of major Christian traditions. The Catholic Church holds distinctive Marian dogmas, namely her status as the Mother of God, her Immaculate Conception, her perpetual virginity, and her Assumption into heaven.[10] Many Protestants minimize Mary's role, based on the lack of biblical support for any beliefs other than the virgin birth.[11] Mary also has the highest position in Islam among all women.[12][13] Two of the longer chapters of the Quran are named after her and her family.[14]

According to Catholic and Eastern Christian teachings, at the end of her earthly life, God raised Mary's body into heaven; this is known in the Christian West as the Assumption of Mary,[15][16] and in the East as the Dormition of the Mother of God. She is said to have miraculously appeared to believers many times over the centuries.

Names and titles

Mary's name in the original manuscripts of the New Testament was based on her original Aramaic name מרים, transliterated as Maryam or Mariam.[17] The English name Mary comes from the Greek Μαρία, a shortened form of the name Μαριάμ. Both Μαρία and Μαριάμ appear in the New Testament.

In Christianity

In Christianity, Mary is commonly referred to as the Virgin Mary, in accordance with the belief that the Holy Spirit impregnated her, thereby conceiving her first-born son Jesus miraculously, without sexual relations with her betrothed/husband Joseph, "until her son [Jesus] was born".[18] The word "until" has inspired considerable analysis on whether Joseph and Mary produced siblings after the birth of Jesus or not.[lower-alpha 5] Among her many other names and titles are the Blessed Virgin Mary (often abbreviated to "BVM", or "BMV" after the Latin "Beata Maria Virgo"),[20] Saint Mary (occasionally), the Mother of God (primarily in Western Christianity), the Theotokos (primarily in Eastern Christianity), Our Lady (Medieval Italian: Madonna), and Queen of Heaven (Regina caeli; see also here),[21][22] although the title "queen of heaven" was for centuries before used as an epithet for a number of ancient sky-goddesses, such as Nin-anna, Astarte, Ishtar and Astoreth, the Canaanite sky-goddess worshipped during the Hebrew prophet Jeremiah's lifetime.[23]

Titles in use vary among Anglicans, Lutherans, Catholics, Orthodox, Protestants, Mormons, and other Christians.

The three main titles for Mary used by the Orthodox are Theotokos (Θεοτόκος or "God-bearer"), Aeiparthenos (ἀειπαρθὲνος) which means ever-virgin, as confirmed in the Second Council of Constantinople in 553, and Panagia (Παναγία) meaning "all-holy".[24] Catholics use a wide variety of titles for Mary, and these titles have in turn given rise to many artistic depictions.

The title Theotokos, which means "God-bearer," was recognized at the Council of Ephesus in 431.[25][26] The direct equivalents of title in Latin are Deipara and Dei Genitrix, although the phrase is more often loosely translated into Latin as Mater Dei ("Mother of God"), with similar patterns for other languages used in the Latin Church. However, this same phrase in Greek (Μήτηρ Θεοῦ), in the abbreviated form ΜΡ ΘΥ, is an indication commonly attached to her image in Byzantine icons. The Council stated that the Church Fathers "did not hesitate to speak of the holy Virgin as the Mother of God".[27][28][29]

Some Marian titles have a direct scriptural basis. For instance, the title "Queen Mother" has been given to Mary, as she was the mother of Jesus, sometimes referred to as the "King of Kings" due to his ancestral descent from King David.[30][31][32][33][34] This is also based on the Hebrew tradition of the "Queen-Mother," the Gebirah or "Great Lady."[35][36] Other titles have arisen from reported miracles, special appeals, or occasions for calling on Mary.[lower-alpha 6]

In Islam

In Islam, Mary is known as Maryam (Arabic: مريم, romanized: Maryām), mother of Isa (عيسى بن مريم). She is often referred to by the honorific title "Sayyidatuna", meaning "Our Lady"; this title is in parallel to "Sayyiduna" ("Our Lord"), used for the prophets.[41] A related term of endearment is "Siddiqah",[42] meaning "she who confirms the truth" and "she who believes sincerely completely". Another title for Mary is "Qānitah", which signifies both constant submission to God and absorption in prayer and invocation in Islam.[43] She is also called "Tahira", meaning "one who has been purified" and representing her status as one of two humans in creation (and the only woman) to not be touched by Satan at any point.[44] In the Quran, she is described both as "the daughter of Imran and "the sister of Aaron".[45]

Life in the New Testament

The canonical Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles are the primary sources of historical information about Mary[46][47]. They are almost contemporary sources, as the synoptic Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles are generally considered dating from around AD 66–90, while the gospel of John would date from AD 90–110. They provide limited information about Mary, as they primarily focus on the teaching of Jesus and on his apostles[46]. The historical reliability of the Gospels and historical reliability of the Acts of the Apostles are subject to debate, as it was common practice in early Christian writings to mix historical facts with legendary stories.[46]

The earliest account of Mary is in the epistle to the Galatians, which was written before the gospels. She is referred to as "a woman" and is not named: "But when the fullness of time had come, God sent his Son, born of a woman, born under the law" (Galatians 4:4).[47]

Mary is mentioned several times in the canonical Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles:

- The Gospel of Luke mentions Mary the most often, identifying her by name twelve times, all of these in the infancy narrative (Luke 1:27–2:34).[48]

- The Gospel of Matthew mentions her by name five times, four of these (1:16, 18, 20: 2:12)[49] in the infancy narrative and only once (Matthew 13:55)[50] outside the infancy narrative.

- The Gospel of Mark names her once (Mark 6:3)[51] and mentions Jesus' mother without naming her in Mark 3:31–32.[52]

- The Gospel of John refers to the mother of Jesus twice, but never mentions her name. She is first seen at the wedding at Cana (John 2:1–12).[53] The second reference has her standing near the cross of Jesus together with Mary Magdalene, Mary of Clopas (or Cleophas), and her own sister (possibly the same as Mary of Clopas; the wording is semantically ambiguous), along with the "disciple whom Jesus loved" (John 19:25–26).[54] John 2:1–12[53] is the only text in the canonical gospels in which the adult Jesus has a conversation with Mary. He does not address her as "Mother" but as "Woman". In Koine Greek (the language that the Gospel of John was composed in), calling one's mother "Woman" was not disrespectful, and could even be tender.[55] Accordingly, some versions of the Bible translate it as "Dear woman".[56]

- In the Acts of the Apostles, Mary and the brothers of Jesus are mentioned in the company of the eleven apostles who are gathered in the upper room after the Ascension of Jesus (Acts 1:14).[57]

In the Book of Revelation, also part of the New Testament, the "woman clothed with the sun" (Revelation 12:1, 12:5–6)[58] is sometimes identified as Mary.

Genealogy

The New Testament tells little of Mary's early history. The Gospel of Matthew does give a genealogy for Jesus by his father's paternal line, only identifying Mary as the wife of Joseph. John 19:25[59] states that Mary had a sister; semantically it is unclear if this sister is the same as Mary of Clopas, or if she is left unnamed. Jerome identifies Mary of Clopas as the sister of Mary, mother of Jesus.[60] According to the early 2nd century historian Hegesippus, Mary of Clopas was likely Mary's sister-in-law, understanding Clopas (Cleophas) to have been Joseph's brother.[61]

According to the writer of Luke, Mary was a relative of Elizabeth, wife of the priest Zechariah of the priestly division of Abijah, who was herself part of the lineage of Aaron and so of the Tribe of Levi.[62] Some of those who believe that the relationship with Elizabeth was on the maternal side, believe that Mary, like Joseph, was of the royal Davidic line and so of the Tribe of Judah, and that the genealogy of Jesus presented in Luke 3 from Nathan, is in fact the genealogy of Mary, while the genealogy from Solomon given in Matthew 1 is that of Joseph.[63][64][65] (Aaron's wife Elisheba was of the tribe of Judah, so all their descendants are from both Levi and Judah.)[66]

Annunciation

Mary resided in "her own house" (Luke 1:56)[67] in Nazareth in Galilee, possibly with her parents, and during her betrothal—the first stage of a Jewish marriage. Jewish maidens were considered marriageable at the age of twelve years and six months, though the actual age of the bride varied with circumstances. The marriage was preceded by the betrothal, after which the bride legally belonged to the bridegroom, though she did not live with him till about a year later, when the marriage used to be celebrated.[68]

The angel Gabriel announced to her that she was to be the mother of the promised Messiah by conceiving him through the Holy Spirit, and, after initially expressing incredulity at the announcement, she responded, "I am the handmaid of the Lord. Let it be done unto me according to your word."[69][lower-alpha 7] Joseph planned to quietly divorce her, but was told her conception was by the Holy Spirit in a dream by "an angel of the Lord"; the angel told him to not hesitate to take her as his wife, which Joseph did, thereby formally completing the wedding rites.[70][71]

Since the angel Gabriel had told Mary that Elizabeth—having previously been barren—was then miraculously pregnant,[72] Mary hurried to see Elizabeth, who was living with her husband Zechariah in "the hill country..., [in] a city of Juda", identified by some with Hebron.[lower-alpha 8] Mary arrived at the house and greeted Elizabeth who called Mary "the mother of my Lord", and Mary spoke the words of praise that later became known as the Magnificat from her first word in the Latin version.[Luke 1:46–55] After about three months, Mary returned to her own house (Luke 1:56–57).[73]

Birth of Jesus

According to the gospel of Luke, a decree of the Roman Emperor Augustus required that Joseph return to his hometown of Bethlehem to register for a Roman census.[lower-alpha 9] While he was there with Mary, she gave birth to Jesus; but because there was no place for them in the inn, she used a manger as a cradle.[75]: p.14 [76] From the age at which Jewish maidens became marriageable, it is possible that Mary gave birth to her son when she was about thirteen or fourteen years of age. No historical document tells us how old she actually was at the time of the Nativity.[68] After eight days, the boy was circumcised according to Jewish law and named "Jesus" (ישוע, Yeshu'a), which means "YHWH is salvation".[77]

After Mary continued in the "blood of her purifying" another 33 days, for a total of 40 days, she brought her burnt offering and sin offering to the Temple in Jerusalem (Luke 2:22),[78] so the priest could make atonement for her.[79] They also presented Jesus – "As it is written in the law of the Lord, Every male that openeth the womb shall be called holy to the Lord" (Luke 2:23; Exodus 13:2; 23:12–15; 22:29; 34:19–20; Numbers 3:13; 18:15).[80] After the prophecies of Simeon and the prophetess Anna in Luke 2:25–38,[81] the family "returned into Galilee, to their own city Nazareth".[82]

According to the gospel of Matthew, magi coming from Eastern regions arrived at Bethlehem where Jesus and his family were living, and worshiped him. Joseph was then warned in a dream that King Herod wanted to murder the infant, and the family fled by night to Egypt and stayed there for some time. After Herod's death in 4 BC, they returned to Nazareth in Galilee, rather than Bethlehem, because Herod's son Archelaus was the ruler of Judaea.[83]

Mary is involved in the only event in Jesus' adolescent life that is recorded in the New Testament. At the age of 12, Jesus, having become separated from his parents on their return journey from the Passover celebration in Jerusalem, was found in the Temple among the religious teachers.[84]: p.210 [85]

In the life of Jesus

Mary was present when, at her suggestion, Jesus worked his first miracle during a wedding at Cana by turning water into wine.[86] Subsequently, there are events when Mary is present along with James, Joseph, Simon, and Judas, called Jesus' brothers, and unnamed sisters.[87] Following Jerome, the Church Fathers interpreted the words translated as "brother" and "sister" as referring to close relatives.[88][89]

The hagiography of Mary and the Holy Family can be contrasted with other material in the Gospels. These references include an incident which can be interpreted as Jesus rejecting his family in the New Testament: "And his mother and his brothers arrived, and standing outside, they sent in a message asking for him […] And looking at those who sat in a circle around him, Jesus said, 'These are my mother and my brothers. Whoever does the will of God is my brother, and sister, and mother'."[90][91]

Mary is also depicted as being present in a group of women at the crucifixion standing near the disciple whom Jesus loved along with Mary of Clopas and Mary Magdalene,[54] to which list Matthew 27:56[92] adds "the mother of the sons of Zebedee", presumably the Salome mentioned in Mark 15:40.[93]

After the Ascension of Jesus

In Acts 1:12-26,[94] especially verse 14, Mary is the only one other than the eleven apostles to be mentioned by name who abode in the upper room, when they returned from Mount Olivet. Her presence with the apostles during the Pentecost is not explicit, although it has been held as a fact by Christian tradition.

From this time, she disappears from the biblical accounts, although it is held by Catholics that she is again portrayed as the heavenly woman in the Book of Revelation.[95]

Her death is not recorded in the scriptures, but Orthodox tradition, tolerated also by Catholics, has her first dying a natural death, known as the Dormition of Mary,[96] and then, soon after, her body itself also being assumed (taken bodily) into Heaven. Belief in the corporeal assumption of Mary is a dogma of the Catholic Church, in the Latin and Eastern Catholic Churches alike, and is believed as well by the Eastern Orthodox Church,[97][98] the Coptic Orthodox Church, and parts of the Anglican Communion and Continuing Anglican movement.[99]

Later writings

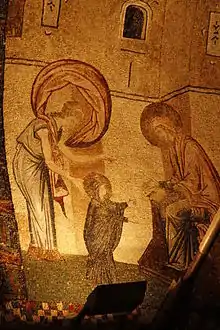

According to the apocryphal Gospel of James, Mary was the daughter of Saint Joachim and Saint Anne. Before Mary's conception, Anne had been barren and was far advanced in years. Mary was given to service as a consecrated virgin in the Temple in Jerusalem when she was three years old, much as Hannah had taken Samuel to the Tabernacle as recorded in the Old Testament.[100] The idea that she was allowed in the Holy of Holies is a patent impossibility, as this likely would have constituted blasphemy for Jews of the time.[101]

While unproven, some apocryphal accounts state that at the time of her betrothal to Joseph, Mary was 12–14 years old.[1] According to ancient Jewish custom, Mary could have been betrothed at about 12.[102] Her age during her pregnancy has varied up to 17 in apochyphal sources.[103][104] Hyppolitus of Thebes says that Mary lived for 11 years after the death of her son Jesus, dying in 41 AD.[105]

The earliest extant biographical writing on Mary is Life of the Virgin, attributed to the 7th-century saint Maximus the Confessor, which portrays her as a key element of the early Christian Church after the death of Jesus.[106][107][108]

Perspectives

Mary | |

|---|---|

The Virgin in Prayer, by Sassoferrato, c. 1650 | |

| |

| Honored in | Christianity, Islam, Druze faith[109] |

| Canonized | Pre-Congregation |

| Major shrine | Santa Maria Maggiore (See Marian shrines) |

| Feast | See Marian feast days |

| Attributes | Blue mantle, crown of 12 stars, pregnant woman, roses, woman with child, woman trampling serpent, crescent moon, woman clothed with the sun, heart pierced by sword, rosary beads |

| Patronage | See Patronage of the Blessed Virgin Mary |

Christian

Christian Marian perspectives include a great deal of diversity. While some Christians such as Catholics and Eastern Orthodox have well established Marian traditions, Protestants at large pay scant attention to Mariological themes. Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Anglican, and Lutherans venerate the Virgin Mary. This veneration especially takes the form of prayer for intercession with her Son, Jesus Christ. Additionally, it includes composing poems and songs in Mary's honor, painting icons or carving statues of her, and conferring titles on Mary that reflect her position among the saints.[22][24][110][111]

Catholic

In the Catholic Church, Mary is accorded the title "Blessed" (beata, μακάρια) in recognition of her assumption to Heaven and her capacity to intercede on behalf of those who pray to her. There is a difference between the usage of the term "blessed" as pertaining to Mary and its usage as pertaining to a beatified person. "Blessed" as a Marian title refers to her exalted state as being the greatest among the saints; for a person who has been declared beatified, on the other hand, "blessed" simply indicates that they may be venerated despite not being canonized. Catholic teachings make clear that Mary is not considered divine and prayers to her are not answered by her, but rather by God through her intercession.[112] The four Catholic dogmas regarding Mary are: her status as Theotokos, or Mother of God; her perpetual virginity; the Immaculate Conception; and her bodily Assumption into Heaven.[113][114][115]

The Blessed Virgin Mary, the mother of Jesus has a more central role in Roman Catholic teachings and beliefs than in any other major Christian group. Not only do Roman Catholics have more theological doctrines and teachings that relate to Mary, but they have more feasts, prayers, devotional and venerative practices than any other group.[110] The Catechism of the Catholic Church states: "The Church's devotion to the Blessed Virgin is intrinsic to Christian worship."[116]

For centuries, Catholics have performed acts of consecration and entrustment to Mary at personal, societal and regional levels. These acts may be directed to the Virgin herself, to the Immaculate Heart of Mary and to the Immaculate Conception. In Catholic teachings, consecration to Mary does not diminish or substitute the love of God, but enhances it, for all consecration is ultimately made to God.[117][118]

Following the growth of Marian devotions in the 16th century, Catholic saints wrote books such as Glories of Mary and True Devotion to Mary that emphasized Marian veneration and taught that "the path to Jesus is through Mary".[119] Marian devotions are at times linked to Christocentric devotions (such as the Alliance of the Hearts of Jesus and Mary).[120]

Major Marian devotions include: Seven Sorrows of Mary, Rosary and scapular, Miraculous Medal and Reparations to Mary.[121][122] The months of May and October are traditionally "Marian months" for Roman Catholics; the daily rosary is encouraged in October and in May Marian devotions take place in many regions.[123][124][125] Popes have issued a number of Marian encyclicals and Apostolic Letters to encourage devotions to and the veneration of the Virgin Mary.

Catholics place high emphasis on Mary's roles as protector and intercessor and the Catechism refers to Mary as "honored with the title 'Mother of God', to whose protection the faithful fly in all their dangers and needs".[116][126][127][128][129] Key Marian prayers include: Ave Maria, Alma Redemptoris Mater, Sub tuum praesidium, Ave maris stella, Regina caeli, Ave Regina caelorum and the Magnificat.[130]

Mary's participation in the processes of salvation and redemption has also been emphasized in the Catholic tradition, but they are not doctrines.[131][132][133][134] Pope John Paul II's 1987 encyclical Redemptoris Mater began with the sentence: "The Mother of the Redeemer has a precise place in the plan of salvation."[135]

In the 20th century, both popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI emphasized the Marian focus of the Catholic Church. Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) suggested a redirection of the whole church towards the program of Pope John Paul II in order to ensure an authentic approach to Christology via a return to the "whole truth about Mary,"[136] writing:

"It is necessary to go back to Mary if we want to return to that 'truth about Jesus Christ,' 'truth about the Church' and 'truth about man.'"[136]

There is significant diversity in the Marian doctrines attributed to her primarily by the Catholic Church. The key Marian doctrines held primarily in Catholicism can be briefly outlined as follows:

- Immaculate Conception: Mary was conceived without original sin.

- Mother of God: Mary, as the mother of Jesus, is the Theotokos (God-bearer), or Mother of God.

- Virgin birth of Jesus: Mary conceived Jesus by action of the Holy Spirit while remaining a virgin.

- Perpetual Virginity: Mary remained a virgin all her life, even after the act of giving birth to Jesus.

- Dormition: commemorates Mary's "falling asleep" or natural death shortly before her Assumption. Dormition is part of accepted Eastern Catholic theology, but not part of Roman Catholic doctrine.[137]

- Assumption: Mary was taken bodily into heaven either at, or before, her death.

The acceptance of these Marian doctrines by Roman Catholics and other Christians can be summarized as follows:[11][138][139]

| Doctrine | Church action | Accepted by |

|---|---|---|

| Mother of God | First Council of Ephesus, 431 | Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Anglicans, Lutherans, some Methodists |

| Virgin birth of Jesus | First Council of Nicaea, 325 | Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Assyrians, Anglicans, Baptists, mainline Protestants |

| Assumption of Mary | Munificentissimus Deus encyclicalPope Pius XII, 1950 | Catholics, Eastern and Oriental Orthodox (only following her natural death), some Anglicans, some Lutherans |

| Immaculate Conception | Ineffabilis Deus encyclicalPope Pius IX, 1854 | Catholics, some Anglicans, some Lutherans (early Martin Luther) |

| Perpetual Virginity | Second Ecumenical Council of Constantinople, 553Smalcald Articles, 1537 | Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Assyrians, some Anglicans, some Lutherans (Martin Luther) |

The title "Mother of God" (Theotokos) for Mary was confirmed by the First Council of Ephesus, held at the Church of Mary in 431. The Council decreed that Mary is the Mother of God because her son Jesus is one person who is both God and man, divine and human.[27] This doctrine is widely accepted by Christians in general, and the term "Mother of God" had already been used within the oldest known prayer to Mary, the Sub tuum praesidium, which dates to around 250 AD.[140]

The Virgin birth of Jesus was an almost universally held belief among Christians from the 2nd until the 19th century.[141] It is included in the two most widely used Christian creeds, which state that Jesus "was incarnate of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary" (the Nicene Creed, in what is now its familiar form)[142] and the Apostles' Creed. The Gospel of Matthew describes Mary as a virgin who fulfilled the prophecy of Isaiah 7:14,[143] The authors of the Gospels of Matthew and Luke consider Jesus' conception not the result of intercourse, and assert that Mary had "no relations with man" before Jesus' birth.[144] This alludes to the belief that Mary conceived Jesus through the action of God the Holy Spirit, and not through intercourse with Joseph or anyone else.[145]

The doctrines of the Assumption or Dormition of Mary relate to her death and bodily assumption to heaven. Roman Catholic Church has dogmatically defined the doctrine of the Assumption, which was done in 1950 by Pope Pius XII in Munificentissimus Deus. Whether Mary died or not is not defined dogmatically, however, although a reference to the death of Mary are made in Munificentissimus Deus. In the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Assumption of the Virgin Mary is believed, and celebrated with her Dormition, where they believe she died.

Catholics believe in the Immaculate Conception of Mary, as proclaimed ex cathedra by Pope Pius IX in 1854, namely that she was filled with grace from the very moment of her conception in her mother's womb and preserved from the stain of original sin. The Latin Church has a liturgical feast by that name, kept on 8 December.[146] Orthodox Christians reject the Immaculate Conception dogma principally because their understanding of ancestral sin (the Greek term corresponding to the Latin "original sin") differs from the Augustinian interpretation and that of the Catholic Church.[147]

The Perpetual Virginity of Mary asserts Mary's real and perpetual virginity even in the act of giving birth to the Son of God made Man. The term Ever-Virgin (Greek ἀειπάρθενος) is applied in this case, stating that Mary remained a virgin for the remainder of her life, making Jesus her biological and only son, whose conception and birth are held to be miraculous.[113][145][148] The Orthodox Churches hold the position articulated in the Protoevangelium of James that Jesus' brothers and sisters were Joseph's children from a marriage prior to that of Mary, which had left him widowed. Roman Catholic teaching follows the Latin father Jerome in considering them Jesus' cousins.

Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodox Christianity includes a large number of traditions regarding the Ever-Virgin Mary, the Theotokos.[149] The Orthodox believe that she was and remained a virgin before and after Christ's birth.[24] The Theotokia (hymns to the Theotokos) are an essential part of the Divine Services in the Eastern Church and their positioning within the liturgical sequence effectively places the Theotokos in the most prominent place after Christ.[150] Within the Orthodox tradition, the order of the saints begins with: the Theotokos, Angels, Prophets, Apostles, Fathers and Martyrs, giving the Virgin Mary precedence over the angels. She is also proclaimed as the "Lady of the Angels".[150]

The views of the Church Fathers still play an important role in the shaping of Orthodox Marian perspective. However, the Orthodox views on Mary are mostly doxological, rather than academic: they are expressed in hymns, praise, liturgical poetry, and the veneration of icons. One of the most loved Orthodox Akathists (standing hymns) is devoted to Mary and it is often simply called the Akathist Hymn.[151] Five of the twelve Great Feasts in Orthodoxy are dedicated to Mary.[24] The Sunday of Orthodoxy directly links the Virgin Mary's identity as Mother of God with icon veneration.[152] A number of Orthodox feasts are connected with the miraculous icons of the Theotokos.[150]

The Orthodox view Mary as "superior to all created beings", although not divine.[153] As such, the designation of Saint to Mary as Saint Mary is not appropriate.[154] The Orthodox does not venerate Mary as conceived immaculate. Gregory of Nazianzus, Archbishop of Constantinople in the 4th century AD, speaking on the Nativity of Jesus Christ argues that "Conceived by the Virgin, who first in body and soul was purified by the Holy Ghost, He came forth as God with that which He had assumed, One Person in two Natures, Flesh and Spirit, of which the latter defined the former."[155] The Orthodox celebrate the Dormition of the Theotokos, rather than Assumption.[24]

The Protoevangelium of James, an extra-canonical book, has been the source of many Orthodox beliefs on Mary. The account of Mary's life presented includes her consecration as a virgin at the temple at age three. The high priest Zachariah blessed Mary and informed her that God had magnified her name among many generations. Zachariah placed Mary on the third step of the altar, whereby God gave her grace. While in the temple, Mary was miraculously fed by an angel, until she was 12 years old. At that point, an angel told Zachariah to betroth Mary to a widower in Israel, who would be indicated. This story provides the theme of many hymns for the Feast of Presentation of Mary, and icons of the feast depict the story.[156] The Orthodox believe that Mary was instrumental in the growth of Christianity during the life of Jesus, and after his Crucifixion, and Orthodox theologian Sergei Bulgakov has written: "The Virgin Mary is the centre, invisible, but real, of the Apostolic Church."

Theologians from the Orthodox tradition have made prominent contributions to the development of Marian thought and devotion. John Damascene (c. 650 – c. 750) was one of the greatest Orthodox theologians. Among other Marian writings, he proclaimed the essential nature of Mary's heavenly Assumption or Dormition and her meditative role.

It was necessary that the body of the one who preserved her virginity intact in giving birth should also be kept incorrupt after death. It was necessary that she, who carried the Creator in her womb when he was a baby, should dwell among the tabernacles of heaven.[157]

From her we have harvested the grape of life; from her we have cultivated the seed of immortality. For our sake she became Mediatrix of all blessings; in her God became man, and man became God.[158]

More recently, Sergei Bulgakov expressed the Orthodox sentiments towards Mary as follows:[153]

Mary is not merely the instrument, but the direct positive condition of the Incarnation, its human aspect. Christ could not have been incarnate by some mechanical process, violating human nature. It was necessary for that nature itself to say for itself, by the mouth of the most pure human being: "Behold the handmaid of the Lord, be it unto me according to Thy word."

Protestant

Protestants in general reject the veneration and invocation of the Saints.[11]: 1174 They share the belief that Mary is the mother of Jesus and "blessed among women" (Luke 1:42)[159] but they generally do not agree that Mary is to be venerated. She is considered to be an outstanding example of a life dedicated to God.[160] As such, they tend not to accept certain church doctrines such as her being preserved from sin.[161] Theologian Karl Barth wrote that "the heresy of the Catholic Church is its Mariology".[162]

Some early Protestants venerated Mary. Martin Luther wrote that: "Mary is full of grace, proclaimed to be entirely without sin. God's grace fills her with everything good and makes her devoid of all evil."[163] However, as of 1532, Luther stopped celebrating the feast of the Assumption of Mary and also discontinued his support of the Immaculate Conception.[164] John Calvin remarked, "It cannot be denied that God in choosing and destining Mary to be the Mother of his Son, granted her the highest honor."[lower-alpha 10] However, Calvin firmly rejected the notion that Mary can intercede between Christ and man.[167]

Although Calvin and Huldrych Zwingli honored Mary as the Mother of God in the 16th century, they did so less than Martin Luther.[168] Thus the idea of respect and high honor for Mary was not rejected by the first Protestants; however, they came to criticize the Roman Catholics for venerating Mary. Following the Council of Trent in the 16th century, as Marian veneration became associated with Catholics, Protestant interest in Mary decreased. During the Age of the Enlightenment, any residual interest in Mary within Protestant churches almost disappeared, although Anglicans and Lutherans continued to honor her.[11]

In the 20th century, some Protestants reacted in opposition to the Catholic dogma of the Assumption of Mary. The tone of the Second Vatican Council began to mend the ecumenical differences, and Protestants began to show interest in Marian themes. In 1997 and 1998, ecumenical dialogues between Catholics and Protestants took place, but, to date, the majority of Protestants disagree with Marian veneration and some view it as a challenge to the authority of Scripture.[11]

Anglican

The various churches that form the Anglican Communion and the Continuing Anglican movement have different views on Marian doctrines and venerative practices given that there is no single church with universal authority within the Communion and that the mother church (the Church of England) understands itself to be both "Catholic" and "Reformed".[169] Thus unlike the Protestant churches at large, the Anglican Communion includes segments which still retain some veneration of Mary.[111]

Mary's special position within God's purpose of salvation as "God-bearer" is recognised in a number of ways by some Anglican Christians.[170] All the member churches of the Anglican Communion affirm in the historic creeds that Jesus was born of the Virgin Mary, and celebrates the feast days of the Presentation of Christ in the Temple. This feast is called in older prayer books the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary on 2 February. The Annunciation of our Lord to the Blessed Virgin on 25 March was from before the time of Bede until the 18th century New Year's Day in England. The Annunciation is called the "Annunciation of our Lady" in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer. Anglicans also celebrate in the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin on 31 May, though in some provinces the traditional date of 2 July is kept. The feast of the St. Mary the Virgin is observed on the traditional day of the Assumption, 15 August. The Nativity of the Blessed Virgin is kept on 8 September.[111]

The Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary is kept in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, on 8 December. In certain Anglo-Catholic parishes this feast is called the Immaculate Conception. Again, the Assumption of Mary is believed in by most Anglo-Catholics, but is considered a pious opinion by moderate Anglicans. Protestant-minded Anglicans reject the celebration of these feasts.[111]

Prayers and venerative practices vary greatly. For instance, as of the 19th century, following the Oxford Movement, Anglo-Catholics frequently pray the Rosary, the Angelus, Regina caeli, and other litanies and anthems of Mary reminiscent of Catholic practices.[171] Conversely, low church Anglicans rarely invoke the Blessed Virgin except in certain hymns, such as the second stanza of Ye Watchers and Ye Holy Ones.[170][172]

The Anglican Society of Mary was formed in 1931 and maintains chapters in many countries. The purpose of the society is to foster devotion to Mary among Anglicans.[111][173] High church Anglicans espouse doctrines that are closer to Roman Catholics, and retain veneration for Mary, such as Anglican pilgrimages to Our Lady of Lourdes, which have taken place since 1963, and pilgrimages to Our Lady of Walsingham, which have taken place for hundreds of years.[174]

Historically, there has been enough common ground between Roman Catholics and Anglicans on Marian issues that in 2005, a joint statement called Mary: grace and hope in Christ was produced through ecumenical meetings of Anglicans and Roman Catholic theologians. This document, informally known as the "Seattle Statement", is not formally endorsed by either the Catholic Church or the Anglican Communion, but is viewed by its authors as the beginning of a joint understanding of Mary.[111][175]

Lutheran

Despite Martin Luther's harsh polemics against his Roman Catholic opponents over issues concerning Mary and the saints, theologians appear to agree that Luther adhered to the Marian decrees of the ecumenical councils and dogmas of the church. He held fast to the belief that Mary was a perpetual virgin and Mother of God.[176][177] Special attention is given to the assertion that Luther, some 300 years before the dogmatization of the Immaculate Conception by Pope Pius IX in 1854, was a firm adherent of that view. Others maintain that Luther in later years changed his position on the Immaculate Conception, which, at that time was undefined in the church, maintaining however the sinlessness of Mary throughout her life.[178][179] For Luther, early in his life, the Assumption of Mary was an understood fact, although he later stated that the Bible did not say anything about it and stopped celebrating its feast. Important to him was the belief that Mary and the saints do live on after death.[180][181][182] "Throughout his career as a priest-professor-reformer, Luther preached, taught, and argued about the veneration of Mary with a verbosity that ranged from childlike piety to sophisticated polemics. His views are intimately linked to his Christocentric theology and its consequences for liturgy and piety."[183]

Luther, while revering Mary, came to criticize the "Papists" for blurring the line between high admiration of the grace of God wherever it is seen in a human being, and religious service given to another creature. He considered the Roman Catholic practice of celebrating saints' days and making intercessory requests addressed especially to Mary and other departed saints to be idolatry.[184][185] His final thoughts on Marian devotion and veneration are preserved in a sermon preached at Wittenberg only a month before his death:

Therefore, when we preach faith, that we should worship nothing but God alone, the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, as we say in the Creed: 'I believe in God the Father almighty and in Jesus Christ,' then we are remaining in the temple at Jerusalem. Again,'This is my beloved Son; listen to him.' 'You will find him in a manger'. He alone does it. But reason says the opposite: What, us? Are we to worship only Christ? Indeed, shouldn't we also honor the holy mother of Christ? She is the woman who bruised the head of the serpent. Hear us, Mary, for thy Son so honors thee that he can refuse thee nothing. Here Bernard went too far in his Homilies on the Gospel: Missus est Angelus.[186] God has commanded that we should honor the parents; therefore I will call upon Mary. She will intercede for me with the Son, and the Son with the Father, who will listen to the Son. So you have the picture of God as angry and Christ as judge; Mary shows to Christ her breast and Christ shows his wounds to the wrathful Father. That's the kind of thing this comely bride, the wisdom of reason cooks up: Mary is the mother of Christ, surely Christ will listen to her; Christ is a stern judge, therefore I will call upon St. George and St. Christopher. No, we have been by God's command baptized in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, just as the Jews were circumcised.[187][188]

Certain Lutheran churches such as the Anglo-Lutheran Catholic Church continue to venerate Mary and the saints in the same manner that Roman Catholics do, and hold all Marian dogmas as part of their faith.[189]

Methodist

Methodists do not have any additional teachings on the Virgin Mary except from what is mentioned in Scripture and the ecumenical Creeds. As such, Methodists generally accept the doctrine of the virgin birth, but reject the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception.[190] John Wesley, the principal founder of the Methodist movement within the Church of England, believed that Mary "continued a pure and unspotted virgin", thus upholding the doctrine of the perpetual virginity of Mary.[191][192] Contemporary Methodism does hold that Mary was a virgin before, during, and immediately after the birth of Christ.[193][194] In addition, some Methodists also hold the doctrine of the Assumption of Mary as a pious opinion.[195]

Nontrinitarian

Nontrinitarians, such as Unitarians, Christadelphians, Jehovah's Witnesses, and Latter-Day Saints[196] also acknowledge Mary as the biological mother of Jesus Christ, but most reject any immaculate conception and do not recognize Marian titles such as "Mother of God". The Latter-Day Saint movement's view affirms the virgin birth of Jesus[197] and Christ's divinity, but only as a separate being than God the Father. The Book of Mormon refers to Mary by name in prophecies and describes her as "most beautiful and fair above all other virgins"[198] and as a "precious and chosen vessel."[199][200]

In non-trinitarian groups that are also Christian mortalists, Mary is not seen as an intercessor between humankind and Jesus, whom mortalists would consider "asleep", awaiting resurrection.[201]

Jewish

The issue of the parentage of Jesus in the Talmud also affects Jewish views of Mary. However, the Talmud does not mention Mary by name, and is considerate rather than only polemic.[202][203] The story about Panthera is also found in the Toledot Yeshu, the literary origins of which can not be traced with any certainty, and given that it is unlikely to go before the 4th century, the time is too late to include authentic remembrances of Jesus.[204] The Blackwell Companion to Jesus states that the Toledot Yeshu has no historical facts and was perhaps created as a tool for warding off conversions to Christianity.[205] The tales from the Toledot Yeshu did impart a negative picture of Mary to ordinary Jewish readers.[206] The circulation of the Toledot Yeshu was widespread among European and Middle Eastern Jewish communities since the 9th century.[207] The name Panthera may be a distortion of the term parthenos ("virgin") and Raymond E. Brown considers the story of Panthera a fanciful explanation of the birth of Jesus that includes very little historical evidence.[208] Robert Van Voorst states that because Toledot Yeshu is a medieval document with its lack of a fixed form and orientation towards a popular audience, it is "most unlikely" to have reliable historical information.[209] Stacks of the copies of the Talmud were burnt upon a court order after the 1240 Disputation for allegedly containing material defaming the character of Mary.[206]

Islamic

.jpg.webp)

The Virgin Mary holds a singularly exalted place in Islam, and she is considered by the Quran to have been the greatest woman in the history of humankind. The Islamic scripture recounts the Divine Promise given to Mary as being: "Mary! God has chosen thee, and purified thee; He hath chosen thee above all the women of creation" (3:42).

Mary is often referred to by Muslims by the honorific title Sayedetina ("Our Lady"). She is mentioned in the Quran as the daughter of Imran.[210]

Moreover, Mary is the only woman named in the Quran and she is mentioned or referred to in the scripture a total of 50 times.[lower-alpha 11] Mary holds a singularly distinguished and honored position among women in the Quran. A sura (chapter) in the Quran is titled "Maryam" (Mary), the only sura in the Quran named after a woman, in which the story of Mary (Maryam) and Jesus (Isa) is recounted according to the view of Jesus in Islam.[14]

Birth

In a narration of hadith from Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq, he mentions that Allah revealed to Imran, "I will grant you a boy, blessed, one who will cure the blind and the leper and one who will raise the dead by My permission. And I will send him as an apostle to the Children of Israel." Then Imran related the story to his wife, Hannah, the mother of Mary. When she became pregnant, she conceived it was a boy, but when she gave birth to a girl, she stated "Oh my Lord! Verily I have delivered a female, and the male is not like the female, for a girl will not be a prophet," to which Allah replies in the Quran, "Allah knows better what has been delivered" (3:36). When Allah bestowed Jesus to Mary, he fulfilled his promise to Imran.[211]

Motherhood

Mary was declared (uniquely along with Jesus) to be a "Sign of God" to humanity;[212] as one who "guarded her chastity";[43] an "obedient one";[43] "chosen of her mother" and dedicated to Allah whilst still in the womb;[213] uniquely (amongst women) "Accepted into service by God";[214] cared for by (one of the prophets as per Islam) Zakariya (Zacharias);[214] that in her childhood she resided in the Temple and uniquely had access to Al-Mihrab (understood to be the Holy of Holies), and was provided with heavenly "provisions" by God.[214][210]

Mary is also called a "Chosen One";[44] a "Purified One";[44] a "Truthful one";[215] her child conceived through "a Word from God";[216] and "exalted above all women of The Worlds/Universes (the material and heavenly worlds)".[44]

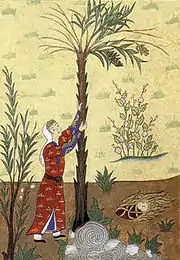

The Quran relates detailed narrative accounts of Maryam (Mary) in two places, 3:35 and 19:16.[217] These state beliefs in both the Immaculate Conception of Mary and the virgin birth of Jesus.[218][219][220] The account given in Sura 19 is nearly identical with that in the Gospel according to Luke, and both of these (Luke, Sura 19) begin with an account of the visitation of an angel upon Zakariya (Zecharias) and "Good News of the birth of Yahya (John)", followed by the account of the annunciation. It mentions how Mary was informed by an angel that she would become the mother of Jesus through the actions of God alone.[221]

In the Islamic tradition, Mary and Jesus were the only children who could not be touched by Satan at the moment of their birth, for God imposed a veil between them and Satan.[222] According to the author Shabbir Akhtar, the Islamic perspective on Mary's Immaculate Conception is compatible with the Catholic doctrine of the same topic. "O People of the Book! Do not go beyond the bounds in your religion, and do not say anything of Allah but the truth. The Messiah, Jesus son of Mary, was but a Messenger of God, and a Word of His (Power) which He conveyed to Mary, and a spirit from Him. So believe in Allah (as the One, Unique God), and His Messengers (including Jesus, as Messenger); and do not say: (Allah is one of) a trinity. Give up (this assertion) – (it is) for your own good (to do so). Allah is but One Allah; All-Glorified He is in that He is absolutely above having a son. To Him belongs whatever is in the heavens and whatever is on the earth. And Allah suffices as the One to be relied on, to Whom affairs should be referred." (Quran 4/171)[223][224]

The Quran says that Jesus was the result of a virgin birth. The most detailed account of the annunciation and birth of Jesus is provided in Suras 3 and 19 of the Quran, where it is written that God sent an angel to announce that she could shortly expect to bear a son, despite being a virgin.[225]

Bahá'í Faith

The Bahá'í Faith venerates Mary as the mother of Jesus. The Kitáb-i-Íqán, the primary theological work of the Bahá'í religion, describes Mary as "that most beauteous countenance," and "that veiled and immortal Countenance." The Bahá'í writings claim Jesus Christ was "conceived of the Holy Ghost"[226] and assert that in the Bahá'í Faith "the reality of the mystery of the Immaculacy of the Virgin Mary is confessed."[227]

Biblical scholars

The statement found in Matthew 1:25 that Joseph did not have sexual relations with Mary before she gave birth to Jesus has been debated among scholars, with some saying that she did not remain a virgin and some saying that she was a perpetual virgin.[228] Other scholars contend that the Greek word heos ("until") denotes a state up to a point, but does not mean that the state ended after that point, and that Matthew 1:25 does not confirm or deny the virginity of Mary after the birth of Jesus.[229][230][231] According to Biblical scholar Bart Ehrman, the Hebrew word almah, meaning young woman of childbearing age, was translated into Greek as parthenos, which often, though not always, refers to a young woman who has never had sex. In Isaiah 7:14, it is commonly believed by Christians to be the prophecy of the Virgin Mary referred to in Matthew 1:23.[232] While Matthew and Luke give differing versions of the virgin birth, John quotes the uninitiated Philip and the disbelieving Jews gathered at Galilee referring to Joseph as Jesus' father.[233][234][235][236]

Other biblical verses have also been debated; for example, the reference made by Paul the Apostle that Jesus was made "of the seed of David according to the flesh" (Romans 1:3)[237] may be interpreted as Joseph being the father of Jesus.[238]

Pre-Christian Rome

From the early stages of Christianity, belief in the virginity of Mary and the virgin conception of Jesus, as stated in the gospels, holy and supernatural, was used by detractors, both political and religious, as a topic for discussions, debates, and writings, specifically aimed to challenge the divinity of Jesus and thus Christians and Christianity alike.[239] In the 2nd century, as part of his anti-Christian polemic The True Word, the pagan philosopher Celsus contended that Jesus was actually the illegitimate son of a Roman soldier named Panthera.[240] The church father Origen dismissed this assertion as a complete fabrication in his apologetic treatise Against Celsus.[241] How far Celsus sourced his view from Jewish sources remains a subject of discussion.[242]

Christian devotion

2nd century

Justin Martyr was among the first to draw a parallel between Eve and Mary. This derives from his comparison of Adam and Jesus. In his Dialogue with Trypho, written sometime between 155-167,[243] he explains:

He became man by the Virgin, in order that the disobedience which proceeded from the serpent might receive its destruction in the same manner in which it derived its origin. For Eve, who was a virgin and undefiled, having conceived the word of the serpent, brought forth disobedience and death. But the Virgin Mary received faith and joy, when the angel Gabriel announced the good tidings to her that the Spirit of the Lord would come upon her, and the power of the Highest would overshadow her: wherefore also the Holy Thing begotten of her is the Son of God; and she replied, 'Be it unto me according to thy word." And by her has He been born, to whom we have proved so many scriptures refer, and by whom God destroys both the serpent and those angels and men who are like him; but works deliverance from death to those who repent of their wickedness and believe upon Him.[244]

Ireneaus, bishop of Lyon, also takes this up, in Against Heresies, written about the year 182:[245]

In accordance with this design, Mary the Virgin is found obedient, saying, "Behold the handmaid of the Lord; be it unto me according to your word." Luke 1:38 But Eve was disobedient; for she did not obey when as yet she was a virgin. ... having become disobedient, was made the cause of death, both to herself and to the entire human race; so also did Mary, having a man betrothed [to her], and being nevertheless a virgin, by yielding obedience, become the cause of salvation, both to herself and the whole human race. And on this account does the law term a woman betrothed to a man, the wife of him who had betrothed her, although she was as yet a virgin; thus indicating the back-reference from Mary to Eve,...For the Lord, having been born "the First-begotten of the dead," Revelation 1:5 and receiving into His bosom the ancient fathers, has regenerated them into the life of God, He having been made Himself the beginning of those that live, as Adam became the beginning of those who die. 1 Corinthians 15:20-22 Wherefore also Luke, commencing the genealogy with the Lord, carried it back to Adam, indicating that it was He who regenerated them into the Gospel of life, and not they Him. And thus also it was that the knot of Eve's disobedience was loosed by the obedience of Mary. For what the virgin Eve had bound fast through unbelief, this did the virgin Mary set free through faith.[246]

During the second century, the Gospel of James was also written. According to Stephen J. Shoemaker, ”its interest in Mary as a figure in her own right and its reverence for her sacred purity mark the beginnings of Marian piety within early Christianity”.[247]

3rd to 5th centuries

Christian devotion to Mary predates the emergence of a specific Marian liturgical system in the 5th century, following the First Council of Ephesus in 431. In Egypt, the veneration of Mary had started in the 3rd century and the term Theotokos was used by Origen, the Alexandrian Father of the Church.[248] The earliest known Marian prayer (the Sub tuum praesidium, or Beneath Thy Protection) is from the 3rd century (perhaps 270), and its text was rediscovered in 1917 on a papyrus in Egypt.[249][250] Following the Edict of Milan in 313, by the 5th century artistic images of Mary began to appear in public and larger churches were being dedicated to Mary, such as the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome.[251][252][253]

The Council of Ephesus itself was held at a church in Ephesus which had been dedicated to Mary about a hundred years before.[254][255][256] The Church of the Seat of Mary in Palestine was built shortly after the introduction of Marian liturgy at the council of Ephesus, in 456, by a widow named Ikelia.[257]

4th-century Arabia

According to the 4th-century heresiologist Epiphanius of Salamis, the Virgin Mary was worshipped as a mother goddess in the Christian sect of Collyridianism, which was found throughout Arabia sometime during the 300s AD. Collyridianism had women performing priestly acts, and made bread offerings to the Virgin Mary. The group was condemned as heretical by the Roman Catholic Church and was preached against by Epiphanius of Salamis, who wrote about the group in his writings titled Panarion.[258]

The adoption of the mother of Jesus as a virtual goddess may represent a reintroduction of aspects of the worship of Isis. According to Sabrina Higgins, "When looking at images of the Egyptian goddess Isis and those of the Virgin Mary, one may initially observe iconographic similarities. These parallels have led many scholars to suggest that there is a distinct iconographic relationship between Isis and Mary. In fact, some scholars have gone even further, and have suggested, on the basis of this relationship, a direct link between the cult of Mary and that of Isis."[259] Conversely, Carl Olson and Sandra Miesel dispute the idea that Christianity copied elements of Isis's iconography, saying that the symbol of a mother and her child is part of the universal human experience.[260]

Byzantium

Ephesus is a cultic centre of Mary, the site of the first church dedicated to her and the rumoured place of her death. Ephesus was previously a centre for worship of Artemis, a virgin goddess; the Temple of Artemis there is regarded as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. The cult of Mary was furthered by Queen Theodora in the 6th century.[261][262] According to William E. Phipps, in the book Survivals of Roman Religion,[263] "Gordon Laing argues convincingly that the worship of Artemis as both virgin and mother at the grand Ephesian temple contributed to the veneration of Mary."[264]

Middle Ages

The Middle Ages saw many legends about Mary, her parents, and even her grandparents.[265] Mary's popularity increased dramatically from the 12th century,[266] linked to the Vatican's designation of Mary as the mediatrix.[267][268]

Post-Reformation

Over the centuries, devotion and veneration to Mary has varied greatly among Christian traditions. For instance, while Protestants show scant attention to Marian prayers or devotions, of all the saints whom the Orthodox venerate, the most honored is Mary, who is considered "more honorable than the Cherubim and more glorious than the Seraphim".[24]

Orthodox theologian Sergei Bulgakov wrote: "Love and veneration of the Blessed Virgin Mary is the soul of Orthodox piety. A faith in Christ which does not include his mother is another faith, another Christianity from that of the Orthodox church."[153]

Although the Catholics and the Orthodox may honor and venerate Mary, they do not view her as divine, nor do they worship her. Roman Catholics view Mary as subordinate to Christ, but uniquely so, in that she is seen as above all other creatures.[269] Similarly, Theologian Sergei Bulgakov wrote that the Orthodox view Mary as "superior to all created beings" and "ceaselessly pray for her intercession". However, she is not considered a "substitute for the One Mediator" who is Christ.[153] "Let Mary be in honor, but let worship be given to the Lord", he wrote.[270] Similarly, Catholics do not worship Mary as a divine being, but rather "hyper-venerate" her. In Roman Catholic theology, the term hyperdulia is reserved for Marian veneration, latria for the worship of God, and dulia for the veneration of other saints and angels.[271] The definition of the three level hierarchy of latria, hyperdulia and dulia goes back to the Second Council of Nicaea in 787.[272]

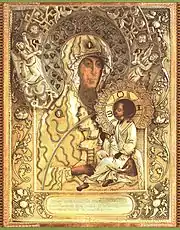

Devotions to artistic depictions of Mary vary among Christian traditions. There is a long tradition of Catholic Marian art and no image permeates Catholic art as does the image of Madonna and Child.[273] The icon of the Virgin Theotokos with Christ is, without doubt, the most venerated icon in the Orthodox Church.[274] Both Roman Catholic and Orthodox Christians venerate images and icons of Mary, given that the Second Council of Nicaea in 787 permitted their veneration with the understanding that those who venerate the image are venerating the reality of the person it represents,[275] and the 842 Synod of Constantinople confirming the same.[276] According to Orthodox piety and traditional practice, however, believers ought to pray before and venerate only flat, two-dimensional icons, and not three-dimensional statues.[277]

The Anglican position towards Mary is in general more conciliatory than that of Protestants at large and in a book he wrote about praying with the icons of Mary, Rowan Williams, former archbishop of Canterbury, said: "It is not only that we cannot understand Mary without seeing her as pointing to Christ; we cannot understand Christ without seeing his attention to Mary."[111][278]

On 4 September 1781, 11 families of pobladores arrived from the Gulf of California and established a city in the name of King Carlos III. The small town was named El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles de la Porciúncula (after our Lady of the Angels), a city that today is known simply as Los Angeles. In an attempt to revive the custom of religious processions within the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, in September 2011 the Queen of Angels Foundation, and founder Mark Anchor Albert, inaugurated an annual Grand Marian Procession in the heart of Downtown Los Angeles' historic core. This yearly procession, held on the last Saturday of August and intended to coincide with the anniversary of the founding of the City of Los Angeles, begins at the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels and concludes at the parish of La Iglesia de Nuestra Señora Reina de los Angeles which is part of the Los Angeles Plaza Historic District, better known as "La Placita".

Feasts

The earliest feasts that relate to Mary grew out of the cycle of feasts that celebrated the Nativity of Jesus. Given that according to the Gospel of Luke (Luke 2:22–40),[279] 40 days after the birth of Jesus, along with the Presentation of Jesus at the Temple, Mary was purified according to Jewish customs. The Feast of the Purification began to be celebrated by the 5th century, and became the "Feast of Simeon" in Byzantium.[280]

In the 7th and 8th centuries, four more Marian feasts were established in Eastern Christianity. In the West, a feast dedicated to Mary, just before Christmas was celebrated in the Churches of Milan and Ravenna in Italy in the 7th century. The four Roman Marian feasts of Purification, Annunciation, Assumption and Nativity of Mary were gradually and sporadically introduced into England by the 11th century.[280]

Over time, the number and nature of feasts (and the associated Titles of Mary) and the venerative practices that accompany them have varied a great deal among diverse Christian traditions. Overall, there are significantly more titles, feasts and venerative Marian practices among Roman Catholics than any other Christians traditions.[110] Some such feasts relate to specific events, such as the Feast of Our Lady of Victory, based on the 1571 victory of the Papal States in the Battle of Lepanto.[281][282]

Differences in feasts may also originate from doctrinal issues—the Feast of the Assumption is such an example. Given that there is no agreement among all Christians on the circumstances of the death, Dormition or Assumption of Mary, the feast of assumption is celebrated among some denominations and not others.[22][283] While the Catholic Church celebrates the Feast of the Assumption on 15 August, some Eastern Catholics celebrate it as Dormition of the Theotokos, and may do so on 28 August, if they follow the Julian calendar. The Eastern Orthodox also celebrate it as the Dormition of the Theotokos, one of their 12 Great Feasts. Protestants do not celebrate this, or any other Marian feasts.[22]

Relics

As Mary's body is believed by most Christians to have been taken up into the glory of heaven, her relics have been limited to:

- bodily relics: hair, nails, breast milk (Chapel of the Milk Grotto)

- clothes: Cincture of the Theotokos (Vatopedi monastery), Holy Girdle (Mount Athos), veil, shirt, gown, shoes

- houses : Basilica della Santa Casa and House of the Virgin Mary

In the 19th century, a house claimed to be that of Mary's was found near Ephesus in Turkey, based on the visions of Anne Catherine Emmerich, an Augustinian nun in Germany.[284][285] It has since been named as the House of the Virgin Mary by Roman Catholic pilgrims who consider it the place where Mary lived until her assumption.[286][287][288][289] The Gospel of John states that Mary went to live with the Disciple whom Jesus loved,[290] traditionally identified as John the Evangelist.[291] Irenaeus and Eusebius of Caesarea wrote in their histories that John later went to Ephesus, which may provide the basis for the early belief that Mary also lived in Ephesus with John.[292][293]

The apparition of Our Lady of the Pillar in the first century was actually believed to be a bilocation, as it occurred in Spain while Mary was living in Ephesus or Jerusalem. The pillar on which she was standing during the apparition is believed to be kept in the Cathedral-Basilica of Our Lady of the Pillar in Zaragoza and is therefore venerated as a relic.

Other relics are said to have been collected during later marian apparitions, such as her robe, veil, and part of her belt which were kept in Blachernae church in Constantinople after she appeared there during the 10th century. These relics, now lost, are celebrated by the Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic Churches as the Intercession of the Theotokos.

Few other objects are said to have been touched or given by Mary during apparitions, notably an image printed on a tilma, known as Our Lady of Guadalupe, belonging to Juan Diego.

Marian relics were criticized by John Calvin in Treatise on Relics:

The belief that the body of the Virgin was not interred on earth, but was taken to heaven, has deprived them of all pretext for manufacturing any relics of her remains, which otherwise might have been sufficiently abundant to fill a whole churchyard; yet in order to have at least something belonging to her, they sought to indemnify themselves for the absence of other relics with the possession of her hair and her milk. The hair is shown in several churches at Rome, and at Salvatierra in Spain, at Maçon, St Flour, Cluny, Nevers, and in many other towns. With regard to the milk, there is not perhaps a town, a convent, or nunnery, where it is not shown in large or small quantities. Indeed, had the Virgin been a wet-nurse her whole life, or a dairy, she could not have produced more than is shown as hers in various parts. How they obtained all this milk they do not say, and it is superfluous here to remark that there is no foundation in the Gospels for these foolish and blasphemous extravagances.

However, the veneration of marian relics by Catholics today is not as widespread as it used to be, as it has been largely surpassed by the veneration of marian images.

In arts

Iconography

In paintings, Mary is traditionally portrayed in blue. This tradition can trace its origin to the Byzantine Empire, from c. 500 AD, where blue was "the colour of an empress". A more practical explanation for the use of this colour is that in Medieval and Renaissance Europe, the blue pigment was derived from the rock lapis lazuli, a stone of greater value than gold, which was imported from Afghanistan. Beyond a painter's retainer, patrons were expected to purchase any gold or lapis lazuli to be used in the painting. Hence, it was an expression of devotion and glorification to swathe the Virgin in gowns of blue. Transformations in visual depictions of Mary from the 13th to 15th centuries mirror her "social" standing within the Church and in society.[294]

Traditional representations of Mary include the crucifixion scene, called Stabat Mater.[295][296] While not recorded in the Gospel accounts, Mary cradling the dead body of her son is a common motif in art, called a "pietà" or "pity".

Mary nursing the Infant Jesus. Early image from the Catacomb of Priscilla, Rome, c. 2nd century

Mary nursing the Infant Jesus. Early image from the Catacomb of Priscilla, Rome, c. 2nd century

Our Lady of Vladimir, a Byzantine representation of the Theotokos

Our Lady of Vladimir, a Byzantine representation of the Theotokos Theotokos Panachranta, from the 11th century Gertrude Psalter

Theotokos Panachranta, from the 11th century Gertrude Psalter Flight into Egypt by Giotto c. 1304

Flight into Egypt by Giotto c. 1304_basilica_inferiore_di_assisi_(1310-1329).jpg.webp) Lamentation by Pietro Lorenzetti, Assisi Basilica, c. 1310–1329

Lamentation by Pietro Lorenzetti, Assisi Basilica, c. 1310–1329

Chinese Madonna, St. Francis' Church, Macao

Chinese Madonna, St. Francis' Church, Macao

Visitation, from the St Vaast Altarpiece by Jacques Daret, 1434–1435

Visitation, from the St Vaast Altarpiece by Jacques Daret, 1434–1435 Virgin of Guadalupe, from the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, Mexico City, 16th century

Virgin of Guadalupe, from the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, Mexico City, 16th century

Madonna on Floral Wreath by Peter Paul Rubens with Jan Brueghel the Elder, c. 1619

Madonna on Floral Wreath by Peter Paul Rubens with Jan Brueghel the Elder, c. 1619 Adoration of the Magi, Rubens, 1634

Adoration of the Magi, Rubens, 1634 Virgin of Montserrat from Puerto Rico, c. 1775-1825

Virgin of Montserrat from Puerto Rico, c. 1775-1825 Virgin and Child, French (15th century)

Virgin and Child, French (15th century) Mary outside St. Nikolai Catholic Church in Ystad 2021

Mary outside St. Nikolai Catholic Church in Ystad 2021 A kneeling Virgin Mary pictured in the former coat of arms of Maaria

A kneeling Virgin Mary pictured in the former coat of arms of Maaria

Cinematic portrayals

Mary has been portrayed in various films and on television, including:

- The Miracle (1912 color silent film of the play The Miracle (as a statue which comes to life))

- Das Mirakel (1912) silent film; a German version of the play The Miracle

- The Song of Bernadette (1943 film), played by Linda Darnell.

- The Living Christ Series (1951 non-theatrical, non-television film twelve-part series), played by Eileen Rowe.

- The Miracle of Our Lady of Fatima (1952 film), played by Virginia Gibson.

- Ben-Hur (1959 film), played by José Greci.[297]

- The Miracle (1959 film; a loose remake of the 1912 film Das Mirakel)

- King of Kings (1961 film), played by Siobhán McKenna.[298]

- The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965 film), played by Dorothy McGuire.[299]

- Jesus of Nazareth (1977 two-part television miniseries), played by Olivia Hussey.[300]

- The Last Temptation of Christ (1988 film), played by Verna Bloom.[301]

- Mary, Mother of Jesus (1999 television film), played by Pernilla August.[302]

- Saint Mary (2002 film), played by Shabnam Gholikhani.[303]

- The Passion of the Christ (2004 film), played by Maia Morgenstern.[304]

- Imperium: Saint Peter (2005 television film), played by Lina Sastri.

- Color of the Cross (2006 film), played by Debbi Morgan.[305]

- The Nativity Story (2006 film), played by Keisha Castle-Hughes.[306]

- The Passion (2008 television miniseries), played by Paloma Baeza.[307][308]

- The Nativity (2010 four-part miniseries), played by Tatiana Maslany.

- Mary of Nazareth (2012 film), played by Alissa Jung.

- Son of God (2014 film), played by Roma Downey.[309]

- Mary Magdalene (2018 film), played by Irit Sheleg.[310]

- Jesus: His Life (2019 TV series), played by Houda Echouafni.[311]

- Fatima (2020 film), played by Joana Ribeiro.

Music

- Claudio Monteverdi: Vespro della Beata Vergine (1610)

- Johann Sebastian Bach: Magnificat (1723, rev. 1733)

- Franz Schubert: Ave Maria (1835)

- Charles Gounod: Ave Maria (1859)

See also

- Acts of Reparation to the Virgin Mary

- Genealogy of Jesus

- History of Catholic Mariology

- Holy Name of Mary

- Litany of the Blessed Virgin Mary

- Madonna (art)

- Marian and Holy Trinity columns

- Marian apparition

- Maryamaweet

- May crowning

- Miraculous births

- Miriai; Mandaean heroine that many equate with Mary

- Mother of the Church

- New Testament people named Mary

- Shrines to the Virgin Mary

- Society of Mary (Marianists)

Notes

- Per the Jewish customs surrounding marriage at the time, and the apocryphal Gospel of James, Mary was approximately 13–14 years old when giving birth to Jesus.[1] Her year of birth is therefore contingent on that of Jesus, and though some posit slightly different dates (such as Meier's dating of c. 7 or 6 BC)[2] general consensus places Jesus' birth in c. 4 BC,[3] thus placing Mary's birth in c. 18 BC.

- According to the Bible and the Quran.

- Hebrew: מִרְיָם, romanized: Mīryām; Imperial Aramaic: ܡܪܝܡ, romanized: Mariam; Arabic: مريم, romanized: Maryam; Ancient Greek: Μαρία, romanized: María; Latin: Maria; Coptic: Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, romanized: Maria; also known by various titles, styles and honorifics

- παρθένος; Matthew 1:23[5] uses the Greek parthénos, "virgin", whereas only the Hebrew of Isaiah 7:14,[6] from which the New Testament ostensibly quotes, as Almah – "young maiden". See article on parthénos in Bauercc/(Arndt)/Gingrich/Danker, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature.[7]

- See Sabine R. Huebner's succinct analysis of the issue: "Jesus is described as the 'first-born son' of Mary in Mt 1:25 and Lk 2:7. From this wording alone we can conclude that there were later-born sons […] The family […] had at least five sons and an unknown number of daughters."[19]

- To give a few examples, Our Lady of Good Counsel, Our Lady of Navigators, and Our Lady Undoer of Knots fit this description.[37][38][39][40]

- This event is described by some Christians as the Annunciation.

- Compare Luke 1:39–40 with Joshua 21:11 The Treasury of Scripture Knowledge says, "This was most probably Hebron, a city of the priests, and situated in the hill country of Judea (Jos 11:21; 21:11, 13), about 25 miles south of Jerusalem, and nearly 100 from Nazareth."

- The historicity of this census' relationship to the birth of Jesus continues to be one of scholarly disagreement; see, for example, p. 71 in Edwards, James R. (2015).[74]

- Alternately: "It cannot even be denied that God conferred the highest honour on Mary, by choosing and appointing her to be the mother of his Son."[165][166]

- See the following verses: 5:114, 5:116, 7:158, 9:31, 17:57, 17:104, 18:102, 19:16, 19:17, 19:18, 19:20, 19:22, 19:24, 19:27, 19:28, 19:29, 19:34, 21:26, 21:91, 21:101, 23:50, 25:17, 33:7, 39:45, 43:57, 43:61, 57:27, 61:6, 61:14, 66:12.

References

- "Catholic Encyclopedia: St. Joseph". Newadvent.org. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- Meier, John P. (1991). A Marginal Jew: The Roots of the Problem and the Person. Yale University Press. p. 407. ISBN 978-0-300-14018-7.

- Sanders, E. P. (1993). The Historical Figure of Jesus. Allen Lane Penguin Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-14-192822-7. Archived from the original on 18 April 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- Raymond Edward Brown; Joseph A. Fitzmyer; Karl Paul Donfried (1978). Mary in the New Testament. NJ: Paulist Press. p. 140. ISBN 9780809121687. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

...consonant with Mary's Jewish background

- Matthew 1:23

- Isaiah 7:14

- Bauercc/(Arndt)/Gingrich/Danker, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature, Second Edition, University of Chicago Press, 1979, p. 627.

- Mark Miravalle, Raymond L. Burke; (2008). Mariology: A Guide for Priests, Deacons, Seminarians, and Consecrated Persons ISBN 978-1-57918-355-4 page 178

- Mary for evangelicals by Tim S. Perry, William J. Abraham 2006 ISBN 0-8308-2569-X page 142

- "Mary, the mother of Jesus." The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, Houghton Mifflin. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2002. Credo Reference. Web. 28 September 2010.

- Encyclopedia of Protestantism, Volume 3 2003 by Hans Joachim Hillerbrand ISBN 0-415-92472-3 p. 1174 Archived 5 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Quran 3:42; cited in Stowasser, Barbara Freyer, "Mary", in: Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān, General Editor: Jane Dammen McAuliffe, Georgetown University, Washington DC.

- J.D. McAuliffe, Chosen of all women

- Jestice, Phyllis G. Holy people of the world: a cross-cultural encyclopedia, Volume 3. 2004 ISBN 1-57607-355-6 page 558 Sayyidana Maryam Archived 27 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Munificentissimus Deus: Dogma of the Assumption by Pius XII, 1950, 17

- Holweck, Frederick (1907), The Feast of the Assumption,(The Catholic Encyclopedia), vol. 2, New York: Robert Appleton Company, archived from the original on 7 January 2020, retrieved 19 April 2015, access date 18 April 2015

- "Mary", A Dictionary of First Names by Patrick Hanks, Kate Hardcastle and Flavia Hodges (27 July 2006). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198610602.

- Matthew 1:25

- Sabine R. Huebner, Papyri and the Social World of the New Testament (Cambridge University Press, 2019), p. 73. ISBN 1108470254

- Fulbert of Chatres, O Beata Virgo Maria, archived from the original on 4 March 2021, retrieved 27 March 2020

- Encyclopedia of Catholicism by Frank K. Flinn, J. Gordon Melton, 2007, ISBN 0-8160-5455-X, pages 443–444

- Hillerbrand, Hans Joachim. Encyclopedia of Protestantism, Volume 3, 2003. ISBN 0-415-92472-3, page 1174

- Jeremiah 44:17–19

- Eastern Orthodoxy through Western eyes by Donald Fairbairn 2002 ISBN 0-664-22497-0 page 99-101

- Longenecker, Father Dwight. "God-bearer". Catholic Answers. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- "Council of Ephesus". New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- "The Canons of the Two Hundred Holy and Blessed Fathers Who Met at Ephesus". Ccel.org. 1 June 2005. Archived from the original on 17 June 2010. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- M'Corry, John StewartTheotokos: Or, the Divine Maternity. 2009 ISBN 1-113-18361-6 page 10

- The Christian theology reader by Alister E. McGrath 2006 ISBN 1-4051-5358-X page 273

- Luke 1:32

- Isaiah 9:6

- 1 Kings 2:19–20

- Jeremiah 13:18–19

- What Every Catholic Should Know about Mary by Terrence J. McNally ISBN 1-4415-1051-6 page 128

- Hahn, Dr. Scott (September 2006). Hail, Holy Queen: The Mother of God in the Word of God. Image. p. 78. ISBN 9780385501699.

- Smith, Scott (2018). What You Need to Know About Mary: But Were Never Taught. Holy Water Books. p. 87. ISBN 978-0998360324.

- Legends of the Madonna by Anna Jameson 2009 1406853380 page 50

- Ann Ball, 2003 Encyclopedia of Catholic Devotions and Practices ISBN 0-87973-910-X page 515

- Candice Lee Goucher, 2007 World history: journeys from past to present ISBN 0-415-77137-4 page 102

- Ann Ball, 2003 Encyclopedia of Catholic Devotions and Practices ISBN 0-87973-910-X page 525

- Glassé, Cyril (2008). "Mary". The New Encyclopedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Plymouth, United Kingdom: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. pp. 340–341. ISBN 9780742562967. Archived from the original on 17 November 2019. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- Quran 5:73-75 Quran 5:73–75

- Quran 66:12

- Quran 3:42

- Quran 19:28

- Hesemann, Michael (8 November 2016). Mary of Nazareth: History, Archaeology, Legends. Ignatius. p. 4. ISBN 9781621640905.

- Canales, Arthur David (2010). "Mary of Nazareth" (PDF). Saint Mary’s Press. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- Luke 1:27–2:34

- Matthew 1:16–2:12

- Matthew 13:55

- Mark 6:3