1995 Quebec referendum

The 1995 Quebec referendum was the second referendum to ask voters in the predominantly French-speaking Canadian province of Quebec whether Quebec should proclaim sovereignty and become an independent country, with the condition precedent of offering a political and economic agreement to Canada.

| ||||||||||||||||

Do you agree that Quebec should become sovereign after having made a formal offer to Canada for a new economic and political partnership within the scope of the bill respecting the future of Quebec and of the agreement signed on June 12, 1995? French: Acceptez-vous que le Québec devienne souverain, après avoir offert formellement au Canada un nouveau partenariat économique et politique, dans le cadre du projet de loi sur l'avenir du Québec et de l'entente signée le 12 juin 1995? | ||||||||||||||||

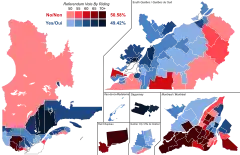

Results by constituency. Shades of blue indicate a "Yes" majority, while shades of red indicate No. The darker the shade, the larger the majority. | ||||||||||||||||

| Location | Quebec | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Results | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

The culmination of multiple years of debate and planning after the failure of the Meech Lake and Charlottetown constitutional accords, the referendum was launched by the provincial Parti Québécois government of Jacques Parizeau. Despite initial predictions of a heavy sovereignist defeat, an eventful and complex campaign followed, with the "Yes" side flourishing after being taken over by Bloc Québécois leader Lucien Bouchard.

Voting took place on 30 October 1995, and featured the largest voter turnout in Quebec's history (93.52%). The "No" option carried by a margin of 54,288 votes, receiving 50.58% of the votes cast.[1] Parizeau, who announced his pending resignation as Quebec premier the following day, later stated that he would have quickly proceeded with a unilateral declaration of independence had the result been affirmative and negotiations failed or been refused,[2] the latter of which was later revealed as the federal position in the event of a "Yes" victory.

Controversies over both the provincial vote counting and direct federal financial involvement in the final days of the campaign reverberated in Canadian politics for over a decade after the referendum took place. In the aftermath of the close result, the federal government, after unilaterally recognizing Quebec as a distinct society and amending the federal constitutional veto procedure, referred the issue to the Supreme Court of Canada, which stated that the unilateral secession contemplated in the referendum was illegal.

Background

Quebec, a province in Canada since its foundation in 1867, has always been the sole majority French-speaking province. Long ruled by forces (such as the Union Nationale) that focused on affirmation of the province's Francophone and Catholic identity within Canada, the Quiet Revolution of the early 1960s prompted a surge in civic and economic nationalism, as well as voices calling for the independence of the province and the establishment of a nation state. Among these was René Lévesque, who founded the Parti Québécois with like-minded groups seeking independence from Canada. After winning power in 1976, the PQ government held a referendum in 1980 seeking a mandate to negotiate "sovereignty-association" with Canada, which was decisively defeated.

In response to the referendum result, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau said that he would seek to "patriate" the Canadian Constitution and institute what would eventually become the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. During tense negotiations in November 1981, an agreement was reached between Trudeau and nine of the ten provincial premiers by Trudeau, but not Lévesque. The Constitution Act of 1982 was enacted without the Quebec National Assembly's approval,[3] after the Supreme Court of Canada ruled against the Quebec government that its consent was not necessary for constitutional change.

New Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and Quebec Liberal premier Robert Bourassa sought a series of constitutional amendments designed to address Quebec's concerns. In the Meech Lake Accord, the federal government and all provincial premiers agreed to a series of amendments that decentralized some powers and recognized Quebec as a distinct society. The Accord, after fierce debate in English Canada, fell apart in dramatic fashion in the summer of 1990, as two provinces failed to ratify it within the three-year time limit required by the constitution. This prompted outrage among Quebec nationalists and a surge in support for sovereignty. While the Accord was collapsing, Lucien Bouchard, a cabinet minister in Mulroney's government, led a coalition of six Progressive Conservative members of parliament and one Liberal MP from Quebec to form a new federal party devoted to Quebec sovereignty, the Bloc Québécois.

Following these events, Bourassa said that a referendum would be held in 1992, with either sovereignty or a new constitutional agreement as the subject.[4] This prompted a national referendum on the Charlottetown Accord of 1992, a series of constitutional amendments that included the proposals of the Meech Lake Accord as well as other matters. The Accord was rejected by a majority of voters both in Quebec and English Canada.

In the 1993 federal election, the Liberals returned to power with a majority government under Jean Chrétien, who had been Minister of Justice during the 1980–81 constitutional discussions and the Bloc Québécois won 54 seats with 49.3% of Quebec's vote. The result made the Bloc the second largest party in the House of Commons, giving it the role of Official Opposition and allowing Bouchard to confront Chrétien in Question Period on a daily basis.

In Quebec, the 1994 provincial election brought the Parti Québécois back to power, led by Jacques Parizeau. The party's platform promised to hold a referendum on sovereignty during the first year of its term in office.[5] The PQ won a majority government with 44.75% of the popular vote, just ahead of the Liberals' 44.4%.

Prelude

.jpg.webp)

In preparation for the referendum, every household in Quebec was sent a draft of the Act Respecting the Future of Quebec (also referred to as the Sovereignty Bill), with the announcement of the National Commission on the Future of Quebec to commence in February 1995. The commission was boycotted by the Liberal Party of Quebec, the Liberal Party of Canada, and the Progressive Conservative Party of Canada.[6]

The primary issue of debate within the sovereignty movement became on what terms sovereignty would be put before the electorate. Parizeau, long identified with the independantiste wing of the party, was opposed to the PQ's general historical preference for an economic relationship with the rest of Canada to be offered alongside sovereignty, as he thought this would encourage the Federal government to simply refuse to negotiate and cast the project as doomed, as had happened in 1980. As a practical matter, Parizeau believed that given the emotional circumstances of separation a special partnership was unlikely, and that given free trade agreements and other multilateral institutions it was unnecessary.

Parizeau's stance created opposition in the sovereignty movement, which coalesced around Bloc Québécois leader Lucien Bouchard. A popular and charismatic figure, Bouchard had come close to death from necrotizing fasciitis and lost his left leg. His recovery, and subsequent public appearances on crutches, provided a rallying point for sovereigntists and the public at large.[7][8] Bouchard thought a proposal lacking a partnership would doom the project among soft nationalists (such as himself) who worried about the economic consequences of separation.

As polls showed Parizeau's approach as highly unlikely to even exceed 40% support in a referendum, leaders of the movement engaged in a heated public debate. After Parizeau moved the planned referendum date to the fall, Deputy Premier Bernard Landry aroused ire by stating he would not want to be involved in a "charge of the light brigade." During the Bloc's April conference, after a speech demanding a change in direction, Bouchard expressed ambivalence to a radio show about participating if a partnership proposal was not included.[9] Mario Dumont, leader of the new Action démocratique du Québec, also stated that he would only consider participation in the referendum if a partnership was made part of the question.[10]

The final findings of the National Commission, issued April 19, included a statement that the public generally desired an economic partnership with Canada.[11] Fearing Bouchard and Dumont would further dilute their position as the referendum wore on,[10] Parizeau agreed to negotiate a broader approach, and would agree to a statement that included partnership with Dumont and Bouchard on June 12, 1995.[12] The Agreement contained details of the partnership negotiation process, and a general plan of seeking "sovereignty" while requiring an economic and social partnership offer be negotiated and presented to the rest of Canada. Most importantly for Parizeau, the agreement also allowed the government to declare immediate independence if negotiations were not successful or heard after a successful referendum.[13]

Bertrand v. Quebec

The looming referendum prompted a number of actions in the Quebec Superior Court, which were consolidated under the application of prominent lawyer Guy Bertrand. Bertrand asked for interim and permanent injunctions against the holding of the referendum.[14] The Federal Attorney General declined to intervene,[14] and after failing in a motion to strike the application, the Quebec Attorney General unilaterally withdrew from the hearing.[15][16] The Quebec government moved the September sitting of the National Assembly two days forward to be sure that parliamentary immunity would prevent MNAs from being summoned to testify.[16]

Justice Lesage of the Court found that secession could only legally be performed by constitutional amendment pursuant to Section V of the Constitution Act, 1982, and that a unilateral declaration of independence would be "manifestly illegal."[14] Lesage refused to issue an injunction to stop the referendum, as he believed that to do so could paralyze the workings of government and cause more disorder than the referendum being held.[17] The Court opted for declaratory relief, declaring that the Sovereignty Bill and the referendum constituted a serious threat to Bertrand's Charter rights.[14][note 1]

Parizeau denounced the decision as undemocratic,[18] stated that the Constitution Act, 1982 did not apply to Quebec,[19] and refused to move the referendum timetable.[18] Quebec Attorney General Paul Bégin stated that he believed an extra-constitutional referendum was legal pursuant to international law.[16] Daniel Johnson announced the following day that the ruling would not change the strategy of the "No" campaign.[16] Some Federal officials questioned if their level of government could be involved after the declaration,[16] but ultimately the Federal government decided to participate.

Referendum question

In a dramatic reading at the Grand Théâtre de Québec on September 6, the final version of the Sovereignty Bill was unveiled.[20] The bill would be tabled in the National Assembly awaiting the result of the referendum.

The question in the 1980 referendum, in an attempt to build a broad coalition, had sought only the authority to negotiate sovereignty with the Canadian government, and promised a second referendum to ratify the results of any negotiation. Parizeau believed a second referendum was unnecessary and would only encourage the remainder of Canada to use delaying tactics. The draft initial Act featured a question only asking for the authority to declare Quebec sovereign.[note 2]

Pursuant to the partnership agreement with Bouchard and Dumont, the referendum question was changed to incorporate the partnership agreement. It was presented on September 7, 1995, to be voted on October 30, 1995. In English, the question on the ballot asked:

Do you agree that Quebec should become sovereign, after having made a formal offer to Canada for a new economic and political partnership, within the scope of the bill respecting the future of Quebec and of the agreement signed on June 12, 1995?[21][note 3]

The question came under immediate fire from federalists, who had no input in the drafting. Quebec Liberal leader Daniel Johnson stated it was confusing and at the very least should have contained the word "country."[22] Prominent federalists argued that the referendum question should not have mentioned "partnership" proposals, because no Canadian political leaders outside Quebec had shown any interest in negotiating a possible partnership agreement with an independent Quebec, and arguably no entity capable of undertaking such negotiations actually existed.[23]

Other federalists argued that the question erroneously implied an agreement had been reached between Canada and Quebec regarding a partnership on June 12, 1995. Parizeau would later express regret that the agreement had to be cited in the question, but noted that the June 12, 1995 agreement had been sent to every registered voter in the province.[24]

Campaign

Participants

Pursuant to Quebec's Referendum Act (enacted by the National Assembly prior to the referendum of 1980), the campaign would be conducted as a provincially governed election campaign, and all campaign spending had to be authorized and accounted for under "Yes" (Le Comité national du OUI) or "No" (Comité des Québécoises et des Québécois pour le NON) umbrella committees. Each committee had an authorized budget of $5 million. Campaign spending by any person or group other than the official committees would be illegal after the official beginning of the referendum campaign.

After the agreement of June 12, the "Yes" campaign would be headed by Jacques Parizeau. The official "No" campaign would be chaired by Liberal leader Daniel Johnson Jr.

Making matters more complex, especially for the "No" camp, was the federal nature of Canada. The governing Liberal Party of Canada and its leader, Prime Minister Jean Chrétien were not strongly represented in the province outside of Montreal. Chrétien's involvement in the 1982 negotiations and his stance against the Meech Lake Accord made him unpopular with moderate francophone federalists and sovereignists, who would be the swing voters in the referendum.[25] Lucienne Robillard, a nationalist former Bourassa-era cabinet minister, would serve as the federal Liberal representative on the "No" committee.[26] Jean Charest, leader of the Federal Progressive Conservative Party, would be prominently featured, as he and the PCs had closely and productively cooperated with the Quebec Liberals in the Meech Lake negotiations.[27]

Fearing missteps by politicians not used to Quebec that had occurred during the Meech Lake and Charlottetown debates, Johnson and the campaign heavily controlled appearances by Federal politicians, including Chrétien.[28] Johnson bluntly banned any appearance by the Reform Party or its leader, Preston Manning.[29] This would go unchallenged by Ottawa for the majority of the campaign,[30] but created much frustration within the governing Liberals in Ottawa.[31] Prominent Chrétien adviser Eddie Goldenberg believed that the "No" campaign at some points was more focused on the future election position of the Quebec Liberals rather than the referendum itself.[32]

Early days

The campaign officially began on October 2, 1995, with a televised address by both leaders. Parizeau emphasized that he believed this might be the last opportunity for sovereignty for the foreseeable future, while Johnson chose to forecast the uncertainty that a "Yes" vote could provoke.[33]

Johnson's campaign focused on the practical problems created by the sovereignty process, emphasizing that an independent Quebec would be in an uncertain position regarding the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and not be able to control the Canadian dollar.[34] Prominent business figures such as Power Corporation president Paul Desmarais and Bombardier Inc. head Laurent Beaudoin spoke that they believed a "Yes" victory could spell doom for their Quebec business interests.[35]

The initial campaign for the "Yes" was led by Parizeau, with Dumont campaigning separately in rural areas. In addition to the traditional themes of the movement's appeal to Quebec nationalism, the "Yes" campaign attempted to highlight the slim possibility of any future reform to Canada's federal system.[36] Parizeau bitterly attacked business leaders for intervening in the referendum, calling it a betrayal of their Quebec customers and workers.[37] While Parizeau's responses were highly popular with "Yes" stalwarts, it was generally seen that speeches against business leaders were only highlighting the economic uncertainty that worried swing voters.[38]

Polls in the first week were highly disappointing for the "Yes" camp, as they showed them behind by 5–7 percentage points among decided voters, with an even larger gap if "undecided" voters were weighed toward the "No" side as would generally be expected.[39] Parizeau, a general fixture in Quebec politics for decades whose strong views of sovereignty were well known among the populace, was under pressure to create a spark.[39]

Appointment of Bouchard

In an unannounced ceremony on October 7 at the Université de Montréal, Parizeau made a surprise announcement: He appointed Bouchard as "chief negotiator" for the partnership talks following a "Yes" vote.[40] The move came as a dramatic surprise to the campaign, promoting the popular Bouchard to the fore and simultaneously emphasizing the "partnership" aspect of the question.[41]

Bouchard, already popular, became a sensation: in addition to his medical struggles and charisma, his more moderate approach and prominent involvement in the Meech Lake Accord while in Ottawa reminded undecided nationalist voters of federal missteps from years past.[42] Politicians on both sides described his appeal as messianic and almost impossible to personally attack, in contrast to the well-worn figures on both sides of the referendum.[43] "No" advisor John Parisella noted that at focus groups, when presented with statements Bouchard had made that they did not like, participants would refuse to believe he meant them.[42] New polls eventually showed a majority of Quebecers intending to vote "Yes".[44]

"No" forces, including Johnson, were shocked by the development, which required wholesale changes in strategy three weeks before the vote.[45] Unwilling to believe Parizeau had given up his leadership role voluntarily, most in the "No" camp and Ottawa had assumed a coup had taken place, though the manoeuvre had been planned and voluntary.[46] The dramatic events prompted many federal politicians to lobby for similarly dramatic intervention from Ottawa and the federal government, which were refused by the "No" committee, who believed that with Bouchard's introduction the margin for error was dramatically reduced.[47] The "No" campaign continued to focus on the economic benefits of federation.[48]

Bouchard's speeches asked Quebecers to vote "Yes" to give a clear mandate for change, and that only the clarity of a "Yes" vote would provide a final solution to Canada's long-standing constitutional issues and a new partnership with English Canada for the betterment of both.[49] Bouchard's popularity was such that his remarks that the Québécois were the "white race" with the lowest rate of reproduction, which threatened to cast the project as focused on ethnic nationalism, were traversed with ease.[50] Bloc Québécois MP Suzanne Tremblay was less successful in this regard, and apologized after answering journalist Joyce Napier's question of how minority francophones outside of Quebec would be helped by independence by stating that Napier's last name and lack of a Québécois accent made her ignorant of the subject.[51][52]

Midcampaign

Pursuant to the Referendum Act, both committees were required to contribute to a brochure sent to every voter describing their positions.[53] The official "No" brochure, written by the Quebec Liberals, stated that Quebec was a distinct society, and that Quebec should enjoy full autonomy in areas of provincial jurisdiction.[53] Parizeau, while speaking in Hull, challenged Chrétien to tell voters that, if "No" won, Ottawa would withdraw from all provincial jurisdictions, prompting a vague response from the "No" campaign.[54]

On October 21 in Longueuil, Johnson, hoping to defuse the issue, ad libbed a challenge to Chrétien to declare his position on distinct society recognition.[55] When presented with the request Chrétien, in New York for a United Nations meeting, responded, "No. We're not talking about the Constitution, we're talking about the separation of Quebec from the rest of Canada."[56] The remarks in direct contradiction to Johnson were portrayed in the press as a blunt refusal.[57]

Chrétien's position was far more difficult than Johnson's: part of the 1993 Liberal election platform had been moving the country away from large scale constitutional debates. Provincial governments were also far more hostile to the constitutional process than they had been in the decade prior, with even the federal government's typical ally, Ontario, being firmly against any pursuit of constitutional accommodation.[58]

French President Jacques Chirac, while answering a call from a viewer in Montreal on CNN's Larry King Live, declared that, if the "Yes" side were successful, the fact that the referendum had succeeded would be recognized by France.[59]

At a federalist rally of about 12,500 people which was held at the Verdun Auditorium on October 24, Chrétien introduced a focus on Quebec's emotional attachment to Canada, promised reforms to give Quebec more power, and in a more startling announcement, declared that he would support enshrinement of Quebec as a distinct society and that he would support reforms to the Canadian constitution.[60] The sudden reversal of Chrétien's long-standing position on the issue, along with Chrétien's wan complexion and atypically nervous appearance, sparked considerable comment.[61] Charest further emphasized his commitment to constitutional reform if a "No" victory was achieved.[60]

Aboriginal activism

In response to the referendum, aboriginal peoples in Quebec strongly affirmed their own right to self-determination. First Nations chiefs said that forcing their peoples to join an independent Quebec without their consent would violate international law, violating their rights to self-determination. Aboriginal groups also demanded to be full participants in any new constitutional negotiations resulting from the referendum.[62] First Nations communities contributed significantly to the tense debate on a hypothetical partition of Quebec.

The Grand Council of the Crees in Northern Quebec was particularly vocal and prominent in its resistance to the idea of being included in an independent Quebec. Grand Chief Matthew Coon Come issued a legal paper, titled Sovereign Injustice,[63] which sought to affirm the Cree right to self-determination in keeping their territories in Canada. On October 24, 1995, the Cree organized their own referendum, asking the question: "Do you consent, as a people, that the Government of Quebec separate the James Bay Crees and Cree traditional territory from Canada in the event of a Yes vote in the Quebec referendum?" 96.3% of the 77% of Crees who cast ballots voted to stay in Canada.

| No/Non: 4,666 (96.3%) |

Yes/Oui: 183 (3.7%) | ||

| ▲ | |||

The Inuit of Nunavik held a similar local vote, asking voters, "Do you agree that Quebec should become sovereign?", with 96% voting No.[62]

| No/Non: 96% | Yes/Oui: 4% | ||

| ▲ | |||

25 October 1995: Three addresses

Five days before the vote, United States President Bill Clinton, while recognizing the referendum as an internal issue of Canada, gave a minute-long statement extolling the virtues of a united Canada, ending with "Canada has been a great model for the rest of the world, and has been a great partner of the United States, and I hope that can continue."[64] While the statement provided relief in sovereignist circles for not being a stronger endorsement of the "No" position,[65] the implication of Clinton, who was popular in Quebec and the leader of the province's most important trading partner, endorsing Canadian unity had strong reverberations in the electorate.[64]

The same night, Prime Minister Jean Chrétien gave a televised address to the nation in English and French. Broadly similar in both languages, Chrétien promoted the virtues of Canadian federalism to Quebec, touched on the shared values of the country, warned that Parizeau would use the referendum result as a mandate to declare independence from Canada (while explicitly not stating the result would be accepted), and announced that Quebec would be recognized as a distinct society and that any future constitutional reform that impacted Quebec would be made with the province's consent.[66]

The "Yes" side was provided airtime for a rebuttal in English and French. Lucien Bouchard was given the task in both languages, with the "Yes" campaign stating that a federal politician should give the response.[67] Bouchard's French address recounted the previous animosities of the constitutional debate, specifically targeting Chrétien's career and actions, including showing a newspaper headline from the aftermath of the 1982 Constitution that featured Trudeau and Chrétien laughing.[68] Bouchard then focused on the details of the partnership aspect of the proposal.[67] He used his English address to ask Canadians to understand the "Yes" side and to announce an intention to negotiate in good faith.[67]

The next day, Montreal radio station CKOI broadcast a prank call by radio announcer Pierre Brassard, impersonating Chrétien, to Queen Elizabeth II asking her to make a televised address imploring Quebecers to vote "no", in an apparent satirical reference to the Chirac and Clinton interventions and the TV addresses of the night before. The Queen appeared to reluctantly agree to the request and talked to Brassard for 17 minutes before her staff identified the hoax (after a delay due to a Chretien aide wrongly speculating to Buckingham Palace staff that it could be a genuine call).[69]

Unity Rally

Fisheries Minister Brian Tobin, expressing anxiety to his staff about the referendum the week before, was told about a small rally planned in Place du Canada in Montreal for businesspersons on October 27.[70] Asked by Federal advisor John Rae, Pierre Claude Nolin agreed to allow Tobin to invite Canadians outside Quebec to the rally, provided Quebec's referendum laws were adhered to.[71] Tobin then encouraged fellow caucus members to send as many people as possible.[72]

After gaining permission from the Prime Minister (over the objections of Quebec members of Cabinet[73]), Tobin then appeared on the national English-language Canada AM, and while disavowing any connection with the "No" organization, announced that the "No" side would be holding a rally in Montreal on October 27, and implored Canadians from around the country to attend the rally to support the "crusade for Canada." [74] Tobin noted that committees were being formed in Ottawa and Toronto, charter aircraft were being ordered, and that Canadian Airlines had a 90% off "unity" sale.[75] Tobin proceeded to call the chairman of Air Canada in his capacity as a private citizen and suggest planes be made available at the same rate, a request that was granted.[75]

Tobin's Canada AM appearance resulted in calls flooding MP's offices in English Canada, and bus companies volunteered hundreds of vehicles to take Canadians from outside of Quebec to Montreal.[76] The rally at Place du Canada was estimated to have between 50,000 and 125,000 attendees, with estimates varying wildly as the crowd grew and shrank throughout the day.[77] Jean Chrétien, Jean Charest and Daniel Johnson spoke to the crowd for the occasion, which would become known as the "Unity Rally".[76] Images of the large crowd with an oversized Canadian flag became iconic.[78] Charest felt the rally helped to keep momentum for the "No" campaign moving.[79]

The federal government's intervention in the rally attracted strident protests from the "Yes" side, who felt the discounts and coordination were an illegal intervention in the referendum.[80] Bouchard publicly contrasted the rally with what he believed was the inattention of English Canada to the collapse of the Meech Lake Accord.[81] Nolin regretted granting permission for the "No" committee once the scale became known,[82] and Johnson felt the rally only exacerbated tensions with regard to English Canada. Opinions on whether the rally had an impact were divided and unable to be gauged, as the rally happened while the final polls for the Monday referendum were being produced.[83]

Opinion polling

During the campaign, polls were reported by all pollsters and press outlets with a general guideline of having undecided voters split unevenly in favour of the "No" side: This ranged from 2/3 to 3/4 of the undecided vote.

| Completion Date | Polling organisation/client | Sample size | Yes | No | Undecided | Lead |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 October 1995 | Official results | 4,757,509 | 49.42% | 50.58% | 1.16% | |

| Oct 27 | Léger & Léger | 1,003 | 47% | 41% | 12% | 6% |

| Oct 27 | Unity Rally held | |||||

| Oct 25 | SOM | 1,115 | 46% | 40% | 14% | 6% |

| Oct 25 | Angus Reid | 1,029 | 48% | 44% | 8% | 4% |

| Oct 25 | Bouchard and Chrétien Television Addresses, Clinton Remarks | |||||

| Oct 23 | CROP | 1,072 | 44% | 43% | 13% | 2% |

| Oct 20 | Léger & Léger | 1,005 | 46% | 42% | 12% | 4% |

| Oct 18 | Angus Reid | 1,012 | 45% | 44% | 11% | 1% |

| Oct 16 | CROP | 1,151 | 42% | 44% | 14% | 2% |

| Oct 16 | SOM | 981 | 43% | 43% | 14% | 0% |

| Oct 12 | Léger & Léger | 1,002 | 45% | 42% | 13% | 3% |

| Oct 12 | Gallup | 1,013 | 39% | 43% | 18% | 4% |

| Oct 11 | Créatec | 470 | 43% | 49% | 8% | 6% |

| Oct 9 | Lepage | 1,285 | 45% | 42% | 13% | 3% |

| Oct 7 | Lucien Bouchard announced as Chief Negotiator for the Yes side | |||||

| Oct 4 | Léger & Léger | 1,015 | 43% | 44% | 13% | 1% |

| Sep 29 | Lepage | 1,369 | 44% | 46% | 10% | 2% |

| Sep 28 | Léger & Léger | 1,006 | 44% | 45% | 11% | 1% |

| Sep 27 | Angus Reid | 1,000 | 41% | 45% | 14% | 4% |

| Sep 25 | SOM/Environics | 1,820 | 39% | 48% | 13% | 9% |

| Sep 25 | CROP | 2,020 | 39% | 47% | 14% | 8% |

| Sep 25 | Decima | 750 | 40% | 42% | 18% | 2% |

| Sep 19 | Créatec | 1,004 | 39% | 46% | 15% | 7% |

| Sep 14 | COMPAS | 500 | 36% | 40% | 24% | 4% |

| Sep 12 | SOM | 1,003 | 37% | 45% | 18% | 8% |

| Sep 9 | Léger & Léger | 959 | 44% | 43% | 13% | 1% |

| Sources: Polls & the 1995 Quebec Referendum, p.15 | ||||||

Result

.svg.png.webp)

93.52% of the 5,087,009 registered Quebecers voted in the referendum, a higher turnout than any provincial or federal election in Canada's history. The proposal of June 12, 1995 was rejected by voters, with 50.58% voting "No" and 49.42% voting "Yes". The margin was significantly smaller than the 1980 referendum. The "Yes" side was the choice of French speakers by an estimated majority of about 60%.[84] Anglophones and allophones (those who do not have English or French as a first language) voted "No" by a margin of 95%.[84]

There was a majority "Yes" vote in 80 out of 125 National Assembly ridings.[84] The "Yes" side was strongest in Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean, the Gaspé, the Centre-du-Québec, and generally the suburbs of Quebec City and Montreal. While there was disappointment in the results of Montreal and the Beauce, Quebec City's soft support for "Yes" was the greatest surprise for the "Yes" side.[84] This prompted speculation that provincial civil servants did not want the uncertainty a "Yes" would bring, especially after Parizeau had promised to integrate displaced Federal civil servants in a sovereign Quebec.[84]

The heavily populated western ridings of Montreal, including the West Island, home to a large anglophone population, voted "No" by margins eclipsing 80%; some polling stations recorded no "Yes" votes at all.[85] The far North, the Outaouais, the Beauce, and the Eastern Townships also generally voted "No".

The riding with the highest "Yes" result was Saguenay along the northern shore with 73.3% voting yes; The riding with the highest "No" result was D'Arcy-McGee in western Montreal with 96.38% voting "No"; The riding with the closest result was Vimont in Laval, which the "Yes" won by 6 votes and the highest turnout was in Marguerite-D'Youville (96.52%).[86]

| Choice | Votes | % |

|---|---|---|

| 2,362,648 | 50.58 | |

| Yes | 2,308,360 | 49.42 |

| Valid votes | 4,671,008 | 98.18 |

| Invalid or blank votes | 86,501 | 1.82 |

| Total votes | 4,757,509 | 100.00 |

| Registered voters and turnout | 5,087,009 | 93.52 |

| Oui/Yes: 2,308,360 (49.4%) |

Non/No: 2,362,648 (50.6%) | ||

| ▲ | |||

Immediate responses

"No" supporters gathered at Métropolis in Montreal, where Johnson expressed hope for reconciliation in Quebec and stated he expected the federal government to pursue constitutional changes.[85] Prime Minister Chrétien echoed similar sentiments to Johnson, and stated that he "extended his hand" to Quebec's premier and government.[87]

"Yes" supporters met at the Palais des congrès de Montréal on referendum night. After the result became known, Dumont and Bouchard made speeches accepting the result as part of the movement's democratic convictions and expressing hope that a subsequent referendum would bring a "Yes" victory.[88]

Jacques Parizeau, who had not prepared a concession speech, rejected one prepared by Jean-François Lisée and spoke without notes. Noting that 60% of French-speakers had voted yes, he stated that he would address French-speaking Québécois as nous ("we"), and that they had spoken clearly in favour of the "Yes."[89] He then stated that the only thing that had stopped the "Yes" side was "money and the ethnic vote" and that the next referendum would be successful with only a few more percentage points of French speakers onside.[89] The remarks, widely lambasted in the Canadian and international press as ethnocentric, sparked surprise and anger in the "Yes" camp, as the movement had gone to great lengths to disown ethnic nationalism.[90]

Bernard Landry confronted Parizeau at a Cabinet meeting the next morning about the remarks, stating that the movement "had to hide its head in shame."[91] Parizeau, after canvassing opinions, then told his Cabinet that he would resign as premier and leader of the Parti Québécois. It was later revealed that he had declared he would retire anyway if the "Yes" side lost, in an embargoed interview with TVA taped days before the referendum.

Six days after the referendum, André Dallaire, a "Yes" supporter with schizophrenia, upset at the result, broke into Chrétien's Ottawa residence armed with a knife.[92] Dallaire attempted to find Chrétien and kill the prime minister in his bed before being discovered by Aline Chrétien, who barricaded the bedroom door.[93] Chrétien was unharmed, and Dallaire would eventually be found not criminally responsible by reason of mental defect.[94]

Contingency preparation for a "Yes" victory

Sovereignists

Sovereignists believed that a "Yes" vote of 50% plus one vote was a binding result pursuant to the Referendum Act and the Sovereignty Bill, [95] as well as the general international law principle of self-determination. In the event of a "Yes" victory, Parizeau had said he intended to return to the National Assembly of Quebec within two days of the result and seek support for a motion recognizing the result of the referendum.[96] In a speech he had prepared in the event of a "Yes" victory, he said a sovereign Quebec's first move would be to "extend a hand to its Canadian neighbour" in partnership pursuant to the wording of the referendum.[97]

Parizeau's immediate plans after the referendum relied upon what he felt would be general pressure from economic markets and the business community in English Canada to stabilize the situation as quickly as possible, which he believed would mitigate any catastrophic initial events (such as blockades) and prepare for negotiations.[98]

Despite the prominent placement of Bouchard in the referendum campaign, Parizeau planned to retain all authority with regard to negotiations, and to appoint most members of the negotiation team if they were to occur.[99] Parizeau also believed federalist Quebecers such as Chrétien and Charest would be quickly disregarded and replaced at negotiations by representatives from the other nine provinces.[100] If the Federal government refused to negotiate, or if negotiations were to exceed October 30, 1996, Parizeau stated that he would proceed with a unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) for an independent Quebec pursuant to Section 26 of the Sovereignty Bill.[2]

Parizeau's hopes for international recognition, a practical requirement of statehood, rested with France and the Francophonie. He believed that if Quebec declared independence in these circumstances, President of the French National Assembly Philippe Séguin, a powerful Gaullist power broker who was sympathetic to the sovereignty movement,[101] would pressure President Chirac to recognize the declaration.[102] He counted on a French recognition to spread quickly to the Francophonie and bring the issue to a head.[103] Benoit Bouchard, Canada's ambassador at the time, believed that the plan was irrational as he doubted Séguin, who was supposed to be a neutral figure in his role, could bring sufficient pressure in the country's semi-presidential system.[104]

In interviews conducted in 2014, Bouchard[105] and Dumont[106] both believed that negotiations would have resulted had the "Yes" side won and that Quebec would have remained in Canada with a more autonomous status. Bouchard, while approving of Parizeau's intention to unilaterally declare independence should negotiations be refused,[107] implied that he and Dumont would have been able to control negotiations and offer a subsequent referendum on a new agreement.[108] Dumont noted that international recognition would have been difficult had two of the three leaders of the "Yes" campaign been against a UDI, and that he and Bouchard were willing to slow the process down if necessary.[109] For his part, Bernard Landry believed that nothing short of a seat at the United Nations would have been accomplished had the "Yes" won.[110]

Recognition

As the referendum was only of force and effect pursuant to a provincial law, neither the provincially sanctioned "No" committee nor the Federal government had any input on the question of the referendum. Federalists strongly differed on how or if a "Yes" referendum result would be recognized. "No" campaign head Daniel Johnson disputed the "Yes" side's position that a simple majority was sufficient to declare independence, as he believed the question was too vague and gave negotiators too broad a mandate given the enormity of the issue and the uncertainty of negotiations.[111][112]

Jean Chrétien refused to publicly comment or consider contingencies regarding a possible "Yes" victory, and at no point stated the referendum bound the Federal government to negotiations or permitted a unilateral declaration of independence.[113] His wording of speeches during the referendum noted that Parizeau would interpret a "Yes" vote as a mandate to separate Quebec from Canada, but never offered recognition that this was legal or recognizable. A speech drafted for Chrétien in the event of a "Yes" vote stated that the question was too ambiguous to be binding and that only dissatisfaction with the status quo had been stated.[113]

Reform party leader Preston Manning, a prominent proponent of direct democracy, would have recognized any result, with critics suspecting he preferred a "Yes" vote for electoral gain.[114] Jean Charest recognized the referendum's legitimacy, although a draft post-referendum speech had him interpreting a "Yes" vote as a call for drastic reform of Canadian federation instead of separation.[115] The New Democratic Party's official position was that the result had to be recognized.[114]

Negotiations

Little planning was made for the possibility of a "Yes" vote by the Canadian federal government, with the general consensus being that the referendum would be easily won and that planning would spark panic or give the referendum undeserved legitimacy. Some members of the federal cabinet met to discuss several possible scenarios, including referring the issue of Quebec's independence to the Supreme Court. Senior civil servants met to consider the impact of a vote for secession on issues such as territorial boundaries and the federal debt. A dispute arose as to whether Jean Chrétien and many prominent members of Cabinet who had been elected in Quebec ridings could represent Canada at a hypothetical partnership negotiation.[116]

Manning intended to immediately call for Chrétien's resignation and for a general election if the referendum were successful,[117] even though the Liberals, independently of their Quebec seats, had a sizable majority in the House of Commons.[116] There was also some doubt that Chrétien would be able to assure the governor general that he retained enough support within his party to remain the prime minister.[116][118] Chrétien's intention was, whatever the result, to stay in office.[119] New Brunswick Premier Frank McKenna later confirmed that he had been invited into a hypothetical "national unity" cabinet if the "Yes" side was victorious,[120] with a general understanding that former Ontario Premier Bob Rae was to be included as well.[121]

Premier of Saskatchewan Roy Romanow secretly formed a committee to study consequences if Quebec successfully seceded, including strengthening Saskatchewan's relationships with other western provinces, also seceding from Canada, or joining the United States.[122]

Controversies post-referendum

Rejected ballots

When the counting was completed, approximately 86,000 ballots were rejected by Deputy Returning Officers, alleging that they had not been marked properly by the voter. Each polling station featured a Deputy Returning Officer (appointed by the "Yes") who counted the ballots while a Poll Clerk (appointed by the "No") recorded the result of the count.[123]

Controversy arose over whether the Deputy Returning Officers of the Chomedey, Marguerite-Bourgeois and Laurier-Dorion ridings had improperly rejected ballots. In these ridings the "No" vote was dominant, and the proportion of rejected ballots was 12%,[124] 5.5% and 3.6%.[125][126] Thomas Mulcair, member of the Quebec National Assembly for Chomedey, told reporters that there was "an orchestrated attempt to steal the vote" in his riding.[124] A study released months after the referendum by McGill University concluded that ridings with a greater number of "No" votes had a higher percentage of rejected ballots.[127] Directeur général des élections du Québec (DGEQ), Pierre F. Cote, launched an inquiry into the alleged irregularities, supervised by the Chief Justice of the Quebec Superior Court, Alan B. Gold. All ballots of the three ridings plus a sample of ballots from other ridings were examined. The inquiry concluded that some ballots had been rejected without valid reasons, but the incidents were isolated. The majority of the rejected ballots were "No" votes, in proportion to the majority of the valid votes in those districts.

Two Deputy Returning Officers were charged by the DGEQ with violating elections laws, but in 1996 were found not guilty (a decision upheld by the Quebec Court of Appeal), after it was found that the ballots were not rejected in a fraudulent or irregular manner, and that there was no proof of conspiracy.[128] A Quebec Court judge acquitted a Deputy Returning Officer charged with illegally rejecting 53% of the ballots cast at his Chomedey polling district.

In 2000, the Quebec Superior Court denied an application by Alliance Quebec that attempted to force the DGEQ to give access to all 5 million ballots, ruling that the only authority that could do so expired in 1996.[129][130] The referendum ballots were shredded and recycled in 2008 after appeals were exhausted.[131] In May 2005, former PQ Cabinet minister Richard Le Hir said that the PQ coordinated the ballot rejections, which PQ officials denied.[132][133]

Citizenship and Immigration Canada

Citizenship Court judges from across Canada were sent into the province to ensure as many qualified immigrants living in Quebec as possible had Canadian citizenship before the referendum, and thus were able to vote. The goal was to have 10,000 to 20,000 outstanding citizenship applications processed for residents of Quebec by mid-October.[134] 43,855 new Quebecers obtained their Canadian citizenship during 1995, with about one quarter of these (11,429) being granted during the month of October.[135] When confronted about the issue by a Bloc Québécois MP who suggested shortcuts were being taken to hurry citizenship applications for immigrants who would most likely vote "No", Minister of Citizenship and Immigration Sergio Marchi responded that this was common before provincial election campaigns in other provinces.[136]

Spending limits and Option Canada

The Canadian Unity Council incorporated a Montreal-based lobbying group called Option Canada with the mandate to promote federalism in Quebec.[137][138] Option Canada received $1.6 million in funding from the Canadian Heritage Department in 1994, $3.35 million in 1995 and $1.1 million in 1996.[139] The Montreal Gazette reported in March 1997 that the group also had other funds from undeclared sources.[138] A Committee to Register Voters Outside Quebec was created to help citizens who had left Quebec before the 1995 vote register on the electoral list. The Committee handed out pamphlets during the referendum, including a form to be added to the list of voters. The pamphlet gave out a toll-free number as contact information, which was the same number as the one used by the Canadian Unity Council.[140]

After the referendum, the DSEQ filed 20 criminal charges of illegal expenditures by Option Canada and others on behalf of the "No" side, which were dropped after the Supreme Court of Canada in Libman vs. Quebec-Attorney General ruled sections of the Referendum Act restricting third-party expenditures were unconstitutionally restrictive under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Aurèle Gervais, communications director for the Liberal Party of Canada, as well as the students' association at Ottawa's Algonquin College, were charged with infractions of Quebec's Election Act after the referendum for illegally hiring buses to bring supporters to Montreal for the rally.[141] Environment Minister Sergio Marchi told reporters that Gervais should wear [the charges against him] like a badge of honour."[142] Two years later, the Quebec Superior Court dismissed the charges, stating that the actions took place outside of Quebec and so the Quebec Election Act did not apply.[143]

The DSEQ asked retired Quebec court judge Bernard Grenier in 2006 to investigate Option Canada after the publication of Normand Lester and Robin Philpot's "The Secrets of Option Canada", which alleged over $5,000,000 had been spent helping the "No" campaign.[144] Grenier determined that CA$539,000 was illegally spent by the "No" side during the referendum, although he drew no conclusions over the "Unity Rally." Grenier said there was no evidence of wrongdoing by Jean Charest or that the rally was part of a plan to sabotage the sovereigntist movement.[145] Grenier urged Quebecers in his report to move on.[145] The Bloc Québécois called for a federal inquiry, which did not occur.[146]

Responses

After the referendum, the ballot for Quebec elections was redesigned to reduce the size of the space where voters could indicate their choice[147] and the rules on allowable markings were relaxed, so that Deputy Returning Officers would have fewer grounds for rejecting ballots. The Quebec government also changed the Electoral Act so that voters would need to show a Canadian passport, Quebec driver's licence or Quebec provincial health care card at the polling station for identification purposes in future elections.

Aftermath

Quebec

Parizeau's resignation led to Bouchard becoming the leader of the PQ and premier unopposed. While Bouchard maintained a third referendum was forthcoming provided "winning conditions" occurred, his government's chief priority became reform of the Quebec economy. Daniel Johnson would resign as leader of the Liberal Party of Quebec, and after significant pressure in English Canada, Charest resigned as national PC leader and was acclaimed as leader of the Quebec Liberals.

Observers expected Bouchard to announce another sovereignty referendum if his party won the 1998 Quebec general election.[148] While he defeated Charest,[149] Bouchard continued his government's focus on austerity. Bouchard retired in 2001 and was replaced by Bernard Landry who, despite promising a more robust stance on the sovereignty issue, was ousted in the 2003 Quebec general election by Charest, who would become premier.

Distinct society and veto

After the referendum, Chrétien attempted to pursue constitutional recognition of distinct society, but was stopped by the blunt refusal of Ontario Premier Mike Harris to discuss any constitutional matters due to his perception they had dominated the country's debates for too long.[150] Given the impossibility of any meaningful change without Ontario's approval, Chrétien opted to pursue unilateral federal changes to fulfill his government's referendum commitments. This included legislation which required permission from the provinces of Quebec, Ontario and British Columbia for federal approval to be granted to any constitutional amendment,[151] granting Quebec a de facto veto.[152] The Federal parliament also officially recognized Quebec as a distinct society. Both changes, not being constitutional amendments, are theoretically reversible by future parliaments.

"Plan B"

Chrétien also pursued what he called "Plan B" in hopes of convincing Quebec voters that economic and legal obstacles would follow if Quebec were to declare itself sovereign; its public face would become professor Stéphane Dion.[153] This included a reference to the Supreme Court of Canada, which followed Federal intervention post-referendum into the Bertrand case: The 1998 Reference Re Secession of Quebec stated that unilateral secession was illegal, would require a constitutional amendment, and that only a clear majority on a clear question could bring about any sort of obligation on the federal and provincial governments to negotiate secession.[154]

After the decision, the Liberal government passed the Clarity Act, which stated that any future referendum would have to be on a "clear question" and that it would have to represent a "clear majority" for the federal Parliament to recognize its validity. Section 1(4) of the Act stated that questions that provided for only a mandate for negotiation or envisioned other partnerships with Canada would be considered unclear, and thus not recognized. The National Assembly of Quebec passed Bill 99, proclaiming the right of self-determination and the right of the National Assembly to set referendum questions pursuant to the Referendum Act and to declare the winning majority in a referendum as a simple majority of 50% plus 1 vote. Bill 99's constitutionality was litigated for 25 years,[155] until the Quebec Court of Appeal ruled in 2021 that the law, given its general wording, was constitutional when applied within provincial jurisdiction.[156]

Sponsorship scandal

Following the narrow victory, the Chrétien government established a pro-Canada advertising campaign. The aim was to sponsor hunting, fishing and other recreational events, and in doing so promote Canada within Quebec. While many of the events sponsored were legitimate, a large sum of money was mismanaged. Auditor General Sheila Fraser released a report in November 2003, outlining the problems. This eventually led to the Gomery Commission's investigation of the Sponsorship Scandal. Bloc Québécois leader Gilles Duceppe argued that Canada was trying to "buy" federalism and using it as an excuse to channel dirty money into Liberal-friendly pockets.

See also

- 1980 Quebec referendum

- Quebec sovereignty movement

- Quebec federalist ideology

- Quebec nationalism

- National Question (Quebec)

- Politics of Quebec

- History of Quebec

Notes

- The Court specifically named Sections 2,3,6,7, 15, and 24(1) of the Charter. (Haljan, 303)

- Are you in favour of the Act passed by the National Assembly declaring the sovereignty of Quebec? (Draft Bill Respecting the Sovereignty of Quebec "Draft Bill on the Sovereignty of Quebec". Archived from the original on 2010-07-02. Retrieved 2009-07-26.)

- In French :"Acceptez-vous que le Québec devienne souverain, après avoir offert formellement au Canada un nouveau partenariat économique et politique, dans le cadre du projet de loi sur l'avenir du Québec et de l'entente signée le 12 juin 1995?"

References

- "Québec Referendum (1995)". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on December 21, 2014. Retrieved December 20, 2014.

- Hébert and Lapierre (2014), p. 42-43.

- Patriation: The Constitution Comes Home Archived 2014-02-27 at the Wayback Machine. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved on June 1, 2007.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 31.

- Benesh, Peter. "As Quebec goes, so goes Canada". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. September 12, 1994.

- Haljan, p. 302.

- Gamble, David. "Bouchard: 'It's My Job'". The Toronto Sun. February 20, 1995.

- Delacourt, Susan. "Flesh-eating disease claims leader's leg". The Tampa Tribune. December 4, 1994.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 108-114.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 130.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 121.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 135.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 136.

- Haljan, p. 303.

- Haljan, p. 302-3.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 149.

- Haljan, p. 304.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 148.

- Johnson, William. Independence referendum? Scotland has it right. Globe and Mail, November 5, 2012 "Independence referendum? Scotland has it right". Archived from the original on 2018-05-01. Retrieved 2017-09-10.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 149-50.

- "Quebec referendum of 1995 – Canadian history". britannica.com. Archived from the original on 14 February 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 153.

- Ruypers; et al. (2005). Canadian and World Politics. Emond Montgomery Publication. p. 196. ISBN 978-1-55239-097-9. Archived from the original on 2021-03-24. Retrieved 2020-10-21.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 155.

- Hébert and Lapierre (2014), p. 253.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 157.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 186.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 183-4.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 189.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 236.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 184-5.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 188.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 208-9.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 213-4.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 214.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 210.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 215.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 218.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 221.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 227.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 231.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 242.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 243.

- Hébert and Lapierre (2014), p. 12.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 229.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 228-30.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 235-6.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 245.

- Hébert and Lapierre (2014), p. 120.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 238.

- "Non-Québécois accent sounds ignorant to MP". Vancouver Sun, October 18, 1995.

- "Leaders on both sides eating their words". Edmonton Journal, October 18, 1995.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 270.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 270-1.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 285.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 286.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 287.

- Hébert and Lapierre (2014), p. 213-4.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 296.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 304.

- Hébert and Lapierre (2014), p. 245.

- Aboriginal Peoples and the 1995 Quebec Referendum: A survey of the issues Archived 2006-06-13 at the Wayback Machine. Parliamentary Research Branch (PRB) of the Library of Parliament. February 1996.

- financière, UNI Coopération. "Erreur – UNI – Coopération financière". uni.ca. Archived from the original on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 311.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 312.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 313-4.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 314.

- Chrétien, p. 147-8.

- F. Sergent, "Un coup de fil pour piéger la reine", Liberation (30 October 1995) https://www.liberation.fr/evenement/1995/10/30/un-coup-de-fil-pour-pieger-la-reine_145691

- Cardinal (2005), p. 324.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 324-27.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 329.

- Hébert and Lapierre (2014), p. 123.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 327-28.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 328.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 334.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 338-9.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 337.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 336.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 342-346.

- Trudeau, Pierre Elliot. "Trudeau Accuses Bouchard of Betraying Quebecers". Montreal Gazette. February 3, 1996. Accessed : "Feb. 3, 1996: Trudeau accuses Bouchard of betraying Quebecers". Archived from the original on 2015-02-09. Retrieved 2015-02-09.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 325.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 342.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 405.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 400.

- "DGEQ October 30, 1995 Results". Le Directeur général des élections du Québec. Archived from the original on December 13, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 401.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 397.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 398.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 398-400.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 407.

- Chrétien, p. 176-7.

- Chrétien, p. 177.

- Chrétien, p. 178.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 356.

- Hébert and Lapierre (2014), p. 44.

- financière, UNI Coopération. "Erreur – UNI – Coopération financière". uni.ca. Archived from the original on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 357-8.

- Hébert and Lapierre (2014), p. 46 and 50.

- Hébert and Lapierre (2014), p. 90.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 195.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 300.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 200.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 301.

- Hébert and Lapierre (2014), p. 20-24.

- Hébert and Lapierre (2014), p. 37.

- Hébert and Lapierre (2014), p. 21.

- Hébert and Lapierre (2014), p. 24.

- Hébert and Lapierre (2014), p. 35.

- Hébert and Lapierre (2014), p. 53.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 355.

- Hébert and Lapierre (2014), p. 88.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 366-7.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 369.

- Hébert and Lapierre (2014), p. 80-81.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 363.

- Hébert and Lapierre (2014), p. 172.

- Seguin, Rheal. "Ministers plotted to oust Chrétien if referendum was lost, CBC says". The Globe and Mail. September 9, 2005.

- Cardinal (2005), p. 366.

- Hébert and Lapierre (2014), p. 219.

- Hébert and Lapierre (2014), p. 228.

- Warren, Jeremy (2014-08-26). "Secret Romanow group mulled secession". The StarPhoenix. Archived from the original on 2014-08-29.

- ^Referendum Act (Quebec) Archived 2017-09-25 at the Wayback Machine, R.S.Q. c.C-64.1, App. 2, S. 310

- Gray, John. "Be strict, PQ told scrutineers 'Following the rules' in Chomedey meant 1 ballot in 9 rejected, mostly votes for No". The Globe and Mail. November 10, 1995.

- "Mysterious doings on referendum night". The Globe and Mail. November 9, 1995.

- "Référendum du 30 octobre 1995" Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine. Elections Quebec. Retrieved on June 1, 2007.

- Contenta, Sandro. "Fears fuelled of referendum plot New report says 'charges of electoral bias ... are plausible'". The Toronto Star. April 29, 1996.

- Contenta, Sandro. "31 face charges over rejection of No ballots But 'no conspiracy' to steal vote found". The Toronto Star. May 14, 1996.

- Referendum Act Archived 2017-09-25 at the Wayback Machine s.42.

- Wyatt, Nelson. "English rights group eyes cash for fight over rejected ballots". The Toronto Star. August 3, 2000.

- The Globe and Mail. Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine May 1, 2008.

- Marsden, William. "Chomedey scrutineers... ...'under orders'". The Montreal Gazette. A8. November 2, 1995.

- Seguin, Rheal. "PQ accused of considering Nazi-style tactics in 1995; Former minister says Parizeau weighed using propaganda before referendum". The Globe and Mail. May 20, 2005.

- "Citizenship blitz in Quebec". The Montreal Gazette. August 31, 1995.

- O'Neill, Pierre. "Le camp du NON a-t-il volé le référendum de 1995?". Le Devoir. August 11, 1999.

- "Question Period – Monday, October 16, 1995" Archived June 4, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Parliament of Canada. Retrieved on June 10, 2007.

- Taber, Jane; Leblanc, Daniel (January 5, 2006). "Mounties eye another referendum handout". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 2006-01-13.

- "Option Canada fuss amounts to little" Archived 2008-06-03 at the Wayback Machine. The Montreal Gazette. May 30, 2007.

- Feurgeson, Elizabeth (May 30, 2007). "A snapshot of Option Canada's history". The Montreal Gazette. Archived from the original on 2008-06-03.

- Macpherson, Don. "Vote-hunting Bid to lure outside voters not a formula for stability". The Montreal Gazette. August 22, 1995.

- "Source of funding for huge federalist rally in Quebec in 1995 still a mystery" Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine. 570 News. May 29, 2007.

- Vienneau, David. "Unity rally charges against top Liberal a 'badge of honour'". The Toronto Star. June 4, 1996.

- "Archived copy". ProQuest 433167694.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Ex-Option Canada director resigns after report on referendum spending" Archived 2008-06-03 at the Wayback Machine. cbc.ca Archived 2017-09-23 at the Wayback Machine. May 30, 2007.

- "'No' side illegally spent $539K in Quebec referendum: report" Archived 2007-05-31 at the Wayback Machine. cbc.ca Archived 2017-09-23 at the Wayback Machine. May 29, 2007.

- "Photo of 1995 referendum ballot". elections.ca. Archived from the original on 1 June 2010. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Turner, Craig (1997-09-20). "Provinces Brainstorm on Issue of Quebec Secession". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on 2019-07-08. Retrieved 2019-07-08.

- Hébert and Lapierre (2014), p. 83.

- Hébert and Lapierre (2014), p. 213-14.

- An Act respecting constitutional amendments, S.C. 1996, c. 1, section 1

- Russell, Peter (2011). "The Patriation and Quebec Veto References: The Supreme Court Wrestles with the Political Part of the Constitution". The Supreme Court Law Review. 54: 76.

- Harder & Patten, eds., The Chrétien Legacy (McGill Queen's University Press, 2006) p. 43

- Reference re Secession of Quebec, [1998] 2 SCR 217, 1998 CanLII 793 (SCC)

- Wells, Paul (October 18, 2013). "Exclusive: Stephen Harper's legal challenge to Quebec secession". Maclean's. Ottawa. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- Wells, Paul (April 10, 2021). "Court rejects Henderson's appeal of Bill 99 ruling, but he cries victory anyway". Montreal Gazette. Montreal. Archived from the original on February 22, 2022. Retrieved Feb 22, 2022.

Consulted works/further reading

- Argyle, Ray (2004). Turning Points: The Campaigns that Changed Canada 2004 and Before. Toronto: White Knight Publications. ISBN 978-0-9734186-6-8.

- Cardinal, Mario (2005). Breaking Point: Quebec, Canada, The 1995 Referendum. Montreal: Bayard Canada Books. ISBN 2-89579-068-X.

- Chrétien, Jean (2007). My Years as Prime Minister. Toronto: Vintage Canada. ISBN 978-0-676-97901-5.

- CBC documentary Breaking Point (2005)

- Robin Philpot (2005). Le Référendum volé. Montreal: Les éditions des intouchables. ISBN 2-89549-189-5.

- Haljan, David (2014). Constitutionalising Secession. Portland: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781782253303.

- Hébert, Chantal (With Jean Lapierre) (2014). The Morning After: The 1995 Referendum and the Day that Almost Was. Toronto: Alfred A Knopf Canada. ISBN 978-0-345-80762-5.

- Paul Jay documentary Neverendum Referendum

- Fox, John; Andersen, Robert; Dubonnet, Joseph (1999). "The Polls and the 1995 Quebec Referendum". Canadian Journal of Sociology. 24 (3): 411–424. doi:10.2307/3341396. JSTOR 3341396.