Mongol invasion of Europe

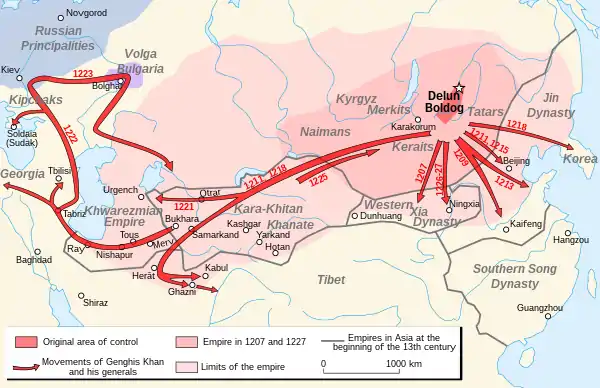

From the 1220s into the 1240s, the Mongols conquered the Turkic states of Volga Bulgaria, Cumania, Alania, and the Kievan Rus' federation. Following this, they began their invasion into heartland Europe by launching a two-pronged invasion of then-fragmented Poland, culminating in the Battle of Legnica (9 April 1241), and the Kingdom of Hungary, culminating in the Battle of Mohi (11 April 1241).[1] Invasions also were launched into the Caucasus against the Kingdom of Georgia and the Chechens and Ingush, as well as into the Southeast Europe against Bulgaria, Croatia, and the Latin Empire. The operations were planned by General Subutai (1175–1248) and commanded by Batu Khan (c. 1207–1255) and Kadan (d. c. 1261). Both of the latter were grandsons of Genghis Khan. Their conquests integrated much of Eastern European territory into the empire of the Golden Horde. Warring European princes realized they had to cooperate in the face of a Mongol invasion, so local wars and conflicts were suspended in parts of central Europe, only to be resumed after the Mongols had withdrawn.[2] After the initial invasions, subsequent raids and punitive expeditions continued into the late 13th century.

| Mongol invasion of Europe | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Mongol invasions and conquests | |||||||||

Mongol invasion of Europe 1236–1242 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

General overview

Invasions and conquest of Rus' lands

In 1223, Mongols routed a near 50,000 Rus'/Cuman army at the Battle of the Kalka River near modern day Mariupol before turning back for nearly a decade.

Ögedei Khan ordered Batu Khan to conquer Rus' in 1235.[3] The main force, headed by Jochi's sons, and their cousins, Möngke Khan and Güyük Khan, arrived at Ryazan in December 1237. Ryazan refused to surrender, and the Mongols sacked it and then stormed Suzdalia. Many Rus' armies were defeated; Grand Prince Yuri was killed on the Sit River (March 4, 1238). Major cities such as Vladimir, Torzhok, and Kozelsk were captured.

Afterward, the Mongols turned their attention to the steppe, crushing the Kypchaks and the Alans and sacking Crimea. Batu appeared in Kievan Rus' in 1239, sacking Pereiaslav and Chernihiv. The Mongols sacked Kiev on December 6, 1240, destroyed Sutiejsk and conquered Halych along with Volodymyr-Volynskyi. Batu sent a small detachment to probe the Poles before passing on to Central Europe. One column was routed by the Poles while the other defeated the Polish army and returned.[4]

Invasion of Central Europe

The attack on Europe was planned and executed by Subutai, who achieved perhaps his most lasting fame with his victories there. Having devastated the various Rus' principalities, he sent spies into Poland and Hungary, and as far as eastern Austria, in preparation for an attack into the heartland of Europe.[5] Having a clear picture of the European kingdoms, he prepared an attack nominally commanded by Batu Khan and two other familial-related princes. Batu Khan, son of Jochi, was the overall leader, but Subutai was the strategist and commander in the field, and as such, was present in both the northern and southern campaigns against Rus' principalities.[6] He also commanded the central column that moved against Hungary. While Kadan's northern force won the Battle of Liegnitz and Güyük's army triumphed in Transylvania, Subutai was waiting for them on the Hungarian plain. The newly reunited army then withdrew to the Sajó river where they inflicted a decisive defeat on King Béla IV of Hungary at the Battle of Mohi. Again, Subutai masterminded the operation, and it would prove one of his greatest victories.

Invasion of Poland

The Mongols invaded Central Europe with three armies. One army defeated an alliance which included forces from fragmented Poland and their allies, led by Henry II the Pious, Duke of Silesia in the Battle of Liegnitz. A second army crossed the Carpathian mountains and a third followed the Danube. The armies re-grouped and crushed Hungary in 1241, defeating the Hungarian army at the Battle of Mohi on April 11, 1241. The devastating Mongol invasion killed half of Hungary's population.[7] The armies swept the plains of Hungary over the summer, and in early 1242 regained impetus and extended their control into Dalmatia and Moravia. The Great Khan had, however, died in December 1241, and on hearing the news, all the "Princes of the Blood," against Subotai's recommendation, went back to Mongolia to elect the new Khan.[8]

After sacking Kiev,[9] Batu Khan sent a smaller group of troops to Poland, destroying Lublin and defeating an inferior Polish army. Other elements—not part of the main Mongol force—saw difficulty near the Polish-Halych border.

The Mongols then reached Polaniec on the Czarna Hańcza, where they set up camp.[10] There, the Voivode attacked them with the remaining Cracovian knights, which were few in number, but determined to vanquish the invader or die. Surprise gave the Poles an initial advantage and they managed to kill many Mongol soldiers. When the invaders realized the actual numerical weakness of the Poles, they regrouped, broke through the Polish ranks and defeated them. During the fighting, many Polish prisoners of war found ways to escape and hide in the nearby woods. The Polish defeat was partly influenced by the initially successful Polish knights having been distracted by looting.

Invasion of Lands of the Bohemian crown (Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia)

After the defeat of the European forces at Liegnitz, the Mongols then continued pillaging throughout Poland's neighboring kingdoms, particularly Silesia and Moravia. King Wenceslaus I of Bohemia fled back to protect his kingdom after arriving late and discovering the devastation the Mongols caused in those places; gathering reinforcements from Thuringia and Saxony as he retreated. He stationed his troops in the mountainous regions of Bohemia where the Mongols would not be able to utilize their cavalry effectively.[11]

By that time, Mongolian forces had divided into two, one led by Batu and Subutai who were planning to invade Hungary, and another led by Baidar and Kadan who were ravaging their way through Silesia and Moravia. When they arrived to attack Bohemia, the kingdom's defenses discouraged them from attacking and they withdrew to the town of Othmachau.[11][12] A small force of Mongolians did attack the strategic located (on the way to the mountain passes towards Bohemia) Silesian town of Glatz but the Bohemian cavalry under Wenceslaus managed to fend them off.[13][14] The Mongols then tried to take the town of Olmuetz, but Wenceslaus managed to get the aid of Austrian Babenbergs and they repulsed the raid.[11][15][16] A Mongol commander was captured in a sortie near Olmuetz.[17] Under Wenceslaus' leadership during the Mongol invasion, Bohemia remained one of a few eastern European kingdoms that was never pillaged by the Mongols even though most kingdoms around it such as Poland and Moravia were ravaged.[11] Such was his success that chroniclers sent messages to Emperor Frederick II of his "victorious defense".[18] After these failed attempts, Baidar and Kadan continued raiding Moravia (via the Moravian Gate route into the valley of the river March towards the Danube) before finally going southward to reunite with Batu and Subutai in Hungary.

Invasion of Hungary

The Hungarians had first learned about the Mongol threat in 1229, when King Andrew II granted asylum to some fleeing Ruthenian boyars. Some Magyars (Hungarians), left behind during the main migration to the Pannonian basin, still lived on the banks of the upper Volga (it is believed by some that the descendants of this group are the modern-day Bashkirs, although this people now speaks a Turkic language, not Magyar). In 1237 a Dominican friar, Julianus, set off on an expedition to lead them back, and was sent back to King Béla with a letter from Batu Khan. In this letter, Batu called upon the Hungarian king to surrender his kingdom unconditionally to the Tatar forces or face complete destruction. Béla did not reply, and two more messages were later delivered to Hungary. The first, in 1239, was sent by the defeated Cuman tribes, who asked for and received asylum in Hungary. The second was sent in February 1241 by the defeated Polish princes.

Only then did King Béla call upon his magnates to join his army in defense of the country. He also asked the papacy and the Western European rulers for help. Foreign help came in the form of a small knight-detachment under the leadership of Frederick II, Duke of Austria, but it was too small to change the outcome of the campaign. The majority of the Hungarian magnates also did not realize the urgency of the matter. Some may have hoped that a defeat of the royal army would force Béla to discontinue his centralization efforts and thus strengthen their own power.

Although the Mongol danger was real and imminent, Hungary was not prepared to deal with it; in the minds of a people who had lived free from nomadic invasions for the last few hundred years, an invasion seemed impossible, and Hungary was no longer a predominantly soldier population. Only rich nobles were trained as heavy-armored cavalry. The Hungarians had long since forgotten the light-cavalry strategy and tactics of their ancestors, which were similar to those now used by the Mongols. The Hungarian army (some 60,000 on the eve of the Battle of Mohi) was made up of individual knights with tactical knowledge, discipline, and talented commanders. Because his army was not experienced in nomadic warfare, King Béla welcomed the Cuman King Kuthen (also known as Kotony) and his fighters. However, the Cuman invitation proved detrimental to the Hungarians because Batu Khan considered this acceptance of a group he considered rebels as justifications for his invasion of Hungary. After rumors began to circulate in Hungary that the Cumans were agents of the Mongols, some hot-headed Hungarians attacked the Cuman camp and killed Kotony. This led the enraged Cumans to ride south, ravaging the countryside, and slaughtering the unsuspecting Magyar population. The Austrian troops retreated to Austria shortly thereafter to gain more western aid. The Hungarians now stood alone in the defense of their country.

The 1241 Mongol invasion first affected Moldavia and Wallachia (situated east and south of the Carpathians). Tens of thousands of Wallachians and Moldavians lost their lives defending their territories from the Golden Horde. Crops and goods plundered from Wallachian settlements seem to have been a primary supply source for the Golden Horde. The invaders killed up to half of the population and burned down most of their settlements, thus destroying much of the cultural and economic records from that period. Neither Wallachians nor the army of Hungary offered much resistance against the Mongols.[19] The swiftness of the invasion took many by surprise and forced them to retreat and hide in forests and the enclosed valleys of the Carpathians. In the end, however, the main target of the invasion was the Kingdom of Hungary.[19]

The Hungarian army arrived and encamped at the Sajó River on April 10, 1241, without having been directly challenged by the Mongols. The Mongols, having largely concealed their positions, began their attack the next night; after heavier-than-expected losses inflicted by Hungarian crossbowmen, the Mongols adjusted their strategy and routed the Hungarian forces rapidly. A major Hungarian loss was imminent, and the Mongols intentionally left a gap in their formation to permit the wavering Hungarian forces to flee and spread out in doing so, leaving them unable to effectively resist the Mongols as they picked off the retreating Hungarian remnants. While the king escaped with the help of his bodyguard, the remaining Hungarian army was killed by the Mongols or drowned in the river as they attempted escape. Following their decisive victory, the Mongols now systematically occupied the Great Hungarian Plains, the slopes of the northern Carpathian Mountains, and Transylvania. Where they found local resistance, they killed the population. Where the locale offered no resistance, they forced the men into servitude in the Mongol army. Still, tens of thousands avoided Mongol domination by taking refuge behind the walls of the few existing fortresses or by hiding in the forests or large marshes along the rivers. The Mongols, instead of leaving the defenseless and helpless people and continuing their campaign through Pannonia to Western Europe, spent time securing and pacifying the occupied territories. On Christmas day 1241, the costly siege of Esztergom destroyed the capital and economic center of the Kingdom of Hungary, forcing the capital to be moved to Buda.[20]

During the winter, contrary to the traditional strategy of nomadic armies which started campaigns only in spring-time, they crossed the Danube and continued their systematic occupation, including Pannonia. They eventually reached the Austrian borders and the Adriatic shores in Dalmatia. The Mongols appointed a darughachi in Hungary and minted coins in the name of Khagan.[21] According to Michael Prawdin, the country of Béla was assigned to Orda by Batu as an appanage. At least 20–40% of the population died, by slaughter or epidemic. Rogerius of Apulia, an Italian monk and chronicler who witnessed and survived the invasion, pointed out not only the genocidal element of the occupation, but also that the Mongols especially "found pleasure" in humiliating local women.[22] But while the Mongols claimed control of Hungary, they could not occupy fortified cities such as Fehérvár, Veszprém, Tihany, Győr, Pannonhalma, Moson, Sopron, Vasvár, Újhely, Zala, Léka, Pozsony , Nyitra, Komárom, Fülek and Abaújvár. Learning from this lesson, fortresses came to play a significant role in Hungary. King Béla IV rebuilt the country and invested in fortifications. Facing a shortage of money, he welcomed the settlement of Jewish families, investors, and tradesmen, granting them citizenship rights. The King also welcomed tens of thousands of Kun (Cumans) who had fled the country before the invasion. Chinese fire arrows were deployed by Mongols against the city of Buda on December 25, 1241, which they overran.[23]

The Mongolian invasion taught the Magyars a simple lesson: although the Mongols had destroyed the countryside, the forts and fortified cities had survived. To improve their defense capabilities for the future, they had to build forts, not only on the borders but also inside the country. In the siege of Esztergom, the defenses managed to hold off the Mongolians despite the latter having overwhelming numerical superiority and 30 siege machines which they had just used to reduce the wooden towers of the city.[24][25] During the remaining decades of the 13th century and throughout the 14th century, the kings donated more and more royal land to the magnates with the condition that they build forts and ensure their defenses.

Invasion of Croatia

During the Middle Ages, the Kingdom of Croatia was in a personal union with the Kingdom of Hungary, with Béla IV as a king.[26][27][28]

When routed on the banks of the Sajó river in 1241 by the Mongols, Béla IV fled to today's Zagreb in Croatia. Batu sent a few tumens (roughly 20,000 men at arms) under Khadan in pursuit of Bela. The major objective was not the conquest but the capture of the Arpad king. The poorly fortified Zagreb was unable to resist the invasion and was destroyed, its cathedral burned by Mongols.[29] In preparation for a second invasion, Gradec was granted a royal charter or Golden Bull of 1242 by King Béla IV, after which citizens of Zagreb engaged in building defensive walls and towers around their settlement.[30]

The Mongols' pursuit of Béla IV continued from Zagreb through Pannonia to Dalmatia. While in pursuit, the Mongols under the leadership of Kadan (Qadan) attacked Klis Fortress in Croatia in March 1242. Due to the strong fortifications of Klis, the Mongols dismounted and climbed over the walls using nearby cliffs. The defenders were able to inflict a number of casualties on the Mongols, which enraged the latter and caused them to fight hand to hand in the streets and gather a sizable amount of loot from houses. As soon as they learned that King Bela was elsewhere, they abandoned the attack and split off to attack Split and Trogir.[31] The Mongols pursued Béla IV from town to town in Dalmatia, while Croatian nobility and Dalmatian towns such as Trogir and Rab helped Béla IV to escape. After being defeated by the Croatian soldiers, the Mongols retreated and Béla IV was awarded Croatian towns and nobility. Only the city of Split did not aid Béla IV in his escape from the Mongols. Some historians claim that the mountainous terrain of Croatian Dalmatia was fatal for the Mongols because of the great losses they suffered from Croat ambushes in mountain passes.[30] In any case, though much of Croatia was plundered and destroyed, long-term occupation was unsuccessful.

Saint Margaret (January 27, 1242 – January 18, 1271), a daughter of Béla IV and Maria Laskarina, was born in Klis Fortress during the Mongol invasion of Hungary-Croatia in 1242.[32]

Invasion of German lands

On 9 April 1241, Mongol detachments entered Meissen and Lusatia following a decisive Mongol victory at the Battle of Liegnitz in Poland.[33] The Mongol light reconnaissance units, led by Orda Khan, pillaged through Meissen and burned most of the city of Meissen to the ground.[34] The Annales sancti Pantaleonis records these attacks.

Invasion of Austria

The subjugation of Hungary opened a pathway for the Mongol Horde to invade Vienna. Using similar tactics during their campaigns in previous Eastern and Central European countries, the Mongols first launched small squadrons to attack isolated settlements in the outskirts of Vienna in an attempt to instill fear and panic among the populace.[35] In 1241 the Mongols raided Wiener Neustadt and its neighboring districts, located south of Vienna. Wiener Neustadt took the brunt of the attack and, like previous invasions, the Mongols committed horrible atrocities on the relatively unarmed populace. The city of Korneuburg, just north of Vienna, was also pillaged and destroyed.[36] The Duke of Austria, Frederick II, had previously engaged the Mongols in Olomouc and in the initial stages of the Battle of Mohi. Unlike in Hungary however, Vienna under the leadership of Duke Frederick and his knights, together with their foreign allies, managed to rally quicker and annihilate the small Mongolian squadron.[37][38] After the battle, the Duke estimated that the Mongols lost 300 to upwards of 700 men, while the defending Europeans lost 100.[39] Austrian knights also subsequently defeated the Mongols at the borders of the River March in the district of Theben.[40] After the failed initial raids, the rest of the Mongols retreated after learning of the Great Khan Ögedei's death.

Invasion of Bulgaria

During his withdrawal from Hungary back into Ruthenia, part of Batu Khan's army invaded Bulgaria. A Mongolian force was defeated by the Bulgarian army under Tsar Ivan Asen II.[41] A larger force returned to raid Bulgaria again the same year, though little is known of what happened. According to the Persian historian Rashid-al-Din Hamadani, the Bulgarian capital of Tarnovo was sacked. This is unlikely, but rumor of it spread widely, being repeated in Palestine by Bar Hebraeus.[42] The invasion of Bulgaria is mentioned in other contemporary sources, such as Philippe Mouskès, Thomas of Cantimpré and Ricoldo of Montecroce.[43] Contemporary documents indicate that by 1253, Kaliman I was a tribute-paying vassal of the Mongols, a status he had probably been forced to accept during the invasion of 1242.[44]

European tactics against Mongols

The traditional European method of warfare of melee combat between knights ended in catastrophe when it was deployed against the Mongol forces as the Mongols were able to keep a distance and advance with superior numbers. The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 29 says that "Employed against the Mongol invaders of Europe, knightly warfare failed even more disastrously for the Poles at the Battle Liegnitz and the Hungarians at the Battle of Mohi in 1241. Feudal Europe was saved from sharing the fate of China and Muscovy not by its tactical prowess but by the unexpected death of the Mongols' supreme ruler, Ögedei, and the subsequent eastward retreat of his armies."[45]

However, during the initial Mongol invasion and the subsequent raids afterwards, heavily armored knights and cavalry proved more effective at fighting the Mongols than their light-armored counterparts. During the Battle of Mohi for example, while the Hungarian light cavalry and infantry were decimated by Mongol forces, the heavily armored knights in their employ (such as the Knights Templar) fought significantly better.[46] During the Battle of Liegnitz, the Knights Templar that numbered between 65 and 88 during the battle lost only three knights and 2 sergeants.[47] Austrian knights under Duke Frederick also fared better in fighting the Mongol invasion in Vienna.[38]

King Béla IV hired the help of the Knights of St. John, as well as training his own better-armed local knights, in preparation for the Second Mongol invasion of Hungary.[48] In the decades following the Mongolian raids on European settlements, Western armies (particularly Hungary) started to adapt to the Mongol tactics by building better fortifications against siege weapons and improving their heavy cavalry.[49] After the division of the Mongol Empire into four fragments, when the Golden Horde attempted the next invasion of Hungary, Hungary had increased their proportion of knights (led by Ladislaus IV of Hungary) and they quickly defeated the main Golden Horde Army in the hills of western Transylvania.[50]

By this time as well, many Eastern and Central European countries had ended their hostilities with one another and united to finally drive out the remnants of the Golden Horde.[51] Guerrilla warfare and stiff resistance also helped many Europeans, particularly those in Croatia and Dzurdzuketia, in preventing the Mongols from setting a permanent hold and driving them off.[52][53]

Possible Mongol diffusion of gunpowder to Europe

Several sources mention the Mongols deploying firearms and gunpowder weapons against European forces at the Battle of Mohi in various forms, including bombs hurled via catapult.[54][55][56] Professor Kenneth Warren Chase credits the Mongols for introducing gunpowder and its associated weaponry into Europe.[57] A later legend arose in Europe about a mysterious Berthold Schwarz who is credited with the invention of gunpowder by 15th- through 19th-century European literature.[58]

End of the Mongol advance

During 1241, most of the Mongol forces were resting on the Hungarian Plain. In late March 1242, they began to withdraw. The most common reason given for this withdrawal is the Great Khan Ögedei's death on December 11, 1241. Ögedei Khan died at the age of fifty-six after a binge of drinking during a hunting trip, which forced most of the Mongolian army to retreat back to Mongolia so that the princes of the blood could be present for the election of a new great khan. This is attested to by one primary source: the chronicle of Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, who after visiting the Mongol court, stated that the Mongols withdrew for this reason; he further stated that God had caused the Great Khan's death to protect Latin Christendom.[59] As Stephen Pow pointed out in his analysis of this issue, by Carpini's account, a messenger would have to be able to make the journey from Mongolia to Central Europe in a little over three months at a minimum; the messenger would have to arrive in March, meaning he took about three months in the middle of winter from the time of the khan's death. Carpini himself accompanied a Mongol party in a much shorter journey (from Kiev to Mongolia) in 1246, where the party "made great speed" in order to reach the election ceremony in time, and made use of several horses per person while riding nearly all day and night. It took five months.[60]

Rashid Al-Din, a historian of the Mongol Ilkhanate, explicitly states in the Ilkhanate's official histories that the Mongols were not even aware of Ogedei's death when they began their withdrawal.[61] Rashid Al-Din, writing under the auspices of the Mongol Empire, had access to the official Mongol chronicle when compiling his history (Altan Debter). John Andrew Boyle asserts, based on the orthography, that Rashid Al-Din's account of the withdrawal from central Europe was taken verbatim from Mongolian records.[62]

Another theory is that weather data preserved in tree rings points to a series of warm, dry summers in the region until 1242. When temperatures dropped and rainfall increased, the local climate shifted to a wetter and colder environment. That, in turn, caused flooding of the formerly dry grasslands and created a marshy terrain. Those conditions would have been less than ideal for the nomadic Mongol cavalry and their encampments, reducing their mobility and pastureland, curtailing their invasion into Europe west of the Hungarian plain,[63] and hastening their retreat.

The true reasons for the Mongol withdrawal are not fully known, but numerous plausible explanations exist. The Mongol invasion had bogged down into a series of costly and frustrating sieges, where they gained little loot and ran into stiff resistance. They had lost a large number of men despite their victories (see above). Finally, they were stretched thin in the European theater, and were experiencing a rebellion by the Cumans (Batu returned to put it down, and spent roughly a year doing so).[64] Others argue Europe's bad weather had an effect: Hungary has a high water table so it floods easily. An analysis of tree rings there found that Hungary had cold wet weather in early 1242, which likely turned Hungary's central plain into a huge swamp; so, lacking pastures for their horses, the Mongols would have had to fall back to Rus' in search of better grasslands.[65]

Regardless of their reasons, the Mongols had completely withdrawn from Central Europe by mid-1242, though they still launched military operations in the west at this time, most notably the 1241–1243 Mongol invasion of Anatolia. Batu specifically decided against attending the kurultai in favor of staying in Europe, which delayed the ceremony for several years.[66]

The historian Jack Weatherford claims that European survival was due to Mongol unwillingness to fight in the more densely populated German principalities, where the weather affected the glue and sinew of the Mongol bows. However, a counter to this assertion is that the Mongols were willing to fight in the densely populated areas of Song China and India. Furthermore, the Mongols were able to conquer Southern China which is located in a tropical climate zone and would have received far more rainfall and humidity than anywhere in Europe.[67][68] The territory of Western Europe had more forests and castles than the Mongols were accustomed, and there were opportunities for the European heavy cavalry to counter-attack. Also, despite the steppe tactics of the Avars and early Hungarians, both were defeated by Western states in the 9th and 10th centuries, though many states conquered by the Mongols have also faced steppe tactics successfully before. A significant number of important castles and towns in Hungary had also resisted the formidable and infamous Mongol siege tactics.

John Keegan thought that Europeans had an advantage due to more food surpluses enabling better campaigns, and larger horses.[69]

Some historians believe that the reason for Batu's stopping at the Mohi River was that he never intended to advance further.[70] He had made the new Rus' conquests secure for the years to come, and when the Great Khan died and Batu rushed back to Mongolia to put in his claim for power, it ended his westward expansion. Subutai's recall at the same time left the Mongol armies without their spiritual head and primary strategist. Batu Khan was not able to resume his plans for conquest to the "Great Sea" (the Atlantic Ocean) until 1255, after the turmoil after Ögedei's death had finally subsided with the election of Möngke Khan as Great Khan. Though he was capable of invading Western Europe, he was no longer interested .

Mongol infighting

From 1241 to 1248 a state of almost open warfare existed between Batu, son of Jochi, and Güyük, son of Ögedei. The Mongol Empire was ruled by a regency under Ögedei's widow Töregene Khatun, whose only goal was to secure the Great Khanate for her son, Güyük. There was so much bitterness between the two branches of the family that when Güyük died in 1248, he was on his way to confront Batu to force him to accept his authority. Batu also had problems in his last years with the Principality of Halych-Volhynia, whose ruler, Danylo of Halych, adopted a policy of confronting the Golden Horde and defeated some Mongol assaults in 1254. He was finally defeated in 1259, when Berke ruled the Horde. Batu Khan was unable to turn his army west until 1255, after Möngke had become Great Khan in 1251, and he had repaired his relations with the Great Khanate. However, as he prepared to finish the invasion of Europe, he died. His son did not live long enough to implement his father and Subutai's plan to invade Europe, and with his death, Batu's younger brother Berke became Khan of the Kipchak Khanate. Berke was not interested in invading Europe as much as stopping his cousin Hulagu Khan from ravaging the Holy Land. Berke had converted to Islam and watched with horror as his cousin destroyed the Abbasid Caliphate, the spiritual head of Islam as far as Berke was concerned. The Mamluks of Egypt, learning through spies that Berke was both a Muslim and not fond of his cousin, appealed to him for help and were careful to nourish their ties to him and his Khanate.

Both entities were Turkic in origin.[71] Many of the Mamluks were of Turkic descent and Berke's Khanate was almost totally Turkic also. Jochi, Genghis Khan's oldest son, was of disputed parentage and only received 4,000 Mongol warriors to start his Khanate. His nearly 500,000 warriors were virtually all Turkic people who had submitted to the Mongols. Thus, the Khanate was Turkic in culture and had more in common with their Muslim Turkic Mamluks brothers than with the Mongol shamanist Hulagu and his horde. Thus, when Hulagu Khan began to mass his army for war against the Mamluk-controlled Holy Land, they swiftly appealed to Berke Khan who sent armies against his cousin and forced him to defend his domains in the north.

Hulagu returned to his lands by 1262, but instead of being able to avenge his defeats, had to turn north to face Berke Khan, suffering severe defeat in an attempted invasion north of the Caucasus in 1263, after Berke Khan had lured him north and away from the Holy Land. Thus, the Kipchak Khanate never invaded Europe, keeping watch to the south and east instead. Berke sent troops into Europe only twice, in two relatively light raids in 1259 and 1265, simply to collect booty he needed to pay for his wars against Hulagu from 1262 to 1265.

Europe at the time of the Mongol invasion

The Papacy had rejected the pleas of Georgia in favor of launching crusades in Iberia and the Middle East, as well as preaching a Crusade against Kievan Rus in 1238 for refusing to join his earlier Balkan Crusade. Meanwhile, Emperor Frederick II, a well-educated ruler, wanted to annex Italy to unite his separated kingdoms of the Holy Roman Empire and Sicily. In addition to calling a council to depose the Holy Roman Emperor, Pope Gregory IX and his successor Innocent IV excommunicated Frederick four times and labeled him the Antichrist.[72]

In the 1240s the efforts of Christendom were already divided between five Crusades, only one of which was aimed against the Mongols. Initially, when Bela sent messengers to the Pope to request a Crusade against the Mongols, the Pope tried to convince them to instead join his Crusade against the Holy Roman Emperor. Eventually Pope Gregory IX did promise a Crusade and the Church finally helped sanction a small Crusade against the Mongols in mid-1241, but it was diverted when he died in August 1241. Instead of fighting the Mongols, the resources gathered by the Crusade was used to fight a Crusade against the Hohenstaufen Dynasty after the German barons revolted against the Holy Roman Emperor's son Conrad in September 1241.[73]

Later raids

The Golden Horde raids in the 1280s (those in Bulgaria, Hungary, and Poland), were much greater in scale than anything since the 1241–1242 invasion, thanks to the lack of civil war in the Mongol Empire at the time. They have sometimes been collectively referred to as "the second Mongol invasion of Europe", "the second Tatar-Mongol invasion of central and south-eastern Europe",[74] or "the second Mongol invasion of central Europe."[75]

Against Poland (1259 and 1287)

In 1259, eighteen years after the first attack, two tumens (20,000 men) from the Golden Horde, under the leadership of Berke, attacked Poland after raiding Lithuania.[76] This attack was commanded by general Burundai with young princes Nogai and Talabuga. Lublin, Sieradz, Sandomierz, Zawichost, Kraków, and Bytom were ravaged and plundered. Berke had no intention of occupying or conquering Poland. After this raid the Pope Alexander IV tried without success to organize a crusade against the Tatars.

An unsuccessful invasion followed in 1287, led by Talabuga and Nogai Khan. 30,000 men (three tumens) in two columns under Nogai (10,000 Mongol cavalry) and Talabuga (20,000 Mongols and Ruthenians) respectively raided Lesser Poland to plunder the area and meet up north of Kraków. Lublin, Mazovia, and Sieradz were successfully raided, but the Mongols failed to capture Sandomierz and Kraków and were repulsed with heavy casualties when they attempted to assault the cities, although the cities were devastated. Talabuga's main army (the rest of his column having dissolved across the countryside for raiding) was defeated by Duke Leszek II at the Battle of Łagów. After this severe setback, Talabuga linked back up with the raiding parties and fled Poland with the loot that was already taken. Nogai's column, after suffering losses during the assault on Kraków, split up to raid the lands both north and south of the city. One detachment headed towards the town of Stary Sącz, another to Podolínec, and others to the Duchy of Sieradz. The first detachment was surprised and defeated by the Poles and their Hungarian allies in the Battle of Stary Sącz, while the second devastated the area of Podhale while skirmishing with the locals. After the defeat at Stary Sącz, Nogai's whole column retreated into Ruthenia.[77]

Against Byzantine Thrace (1265, 1324 and 1337)

During the reign of Berke there was also a raid against Thrace. In the winter of 1265, the Bulgarian czar, Constantine Tych, requested Mongol intervention against the Byzantines in the Balkans. Nogai Khan led a Mongol raid of 20,000 cavalry (two tumens) against the territories of Byzantine eastern Thrace. In early 1265, Michael VIII Palaeologus confronted the Mongols, but his smaller squadron apparently had very low morale and was quickly routed. Most of them were cut down as they fled. Michael was forced to retreat to Constantinople on a Genoese ship while Nogai's army plundered all of Thrace. Following this defeat, the Byzantine emperor made an alliance with the Golden Horde (which was massively beneficial for the latter), giving his daughter Euphrosyne in marriage to Nogai. Michael also sent much valuable fabric to Golden Horde as tribute.[78]

Thrace also suffered raids in 1324 and 1337, during the reign of Uzbeg Khan.[79]

Against Bulgaria (1271, 1274, 1280 and 1285)

The successors of Tsar Ivan Asen II – the regency of Kaliman Asen I decided to pay tax to the Golden Horde. In 1271 Nogai Khan led a successful raid against the country, which was a vassal of the Golden Horde until the early 14th century. Bulgaria was again raided by the Tatars in 1274, 1280 and 1285. In 1278 and 1279 Tsar Ivailo led the Bulgarian army and crushed the Mongol raids before being surrounded at Silistra.[80] After a three-month siege, he managed to once again break through the elite Mongol forces, forcing them to retreat north of the Danube. In 1280 a rebellion inspired by Byzantium left Ivailo without much support, and so he fled to Nogai's camp, asking him for help before being killed by the Mongols. Tsar George I, however, became a Mongol vassal before the Mongol threat was finally ended with the reign of Theodore Svetoslav.

Against Hungary (1285)

In 1285 Nogai Khan led a raid of Hungary alongside Talabuga. Nogai lead an army that ravaged Transylvania with success: Cities like Reghin, Brașov and Bistrița were plundered and ravaged. However Talabuga, who led the main army in Northern Hungary, was stopped by the heavy snow of the Carpathians and the invading force was defeated[81] near Pest by the royal army of Ladislaus IV and ambushed by the Székely in the return. Nogai's own column suffered serious casualties. As with later invasions, it was repelled handily, the Mongols losing much of their invading force. The outcome could not have contrasted more sharply with the 1241 invasion, mostly due to the reforms of Béla IV, which included advances in military tactics and, most importantly, the widespread building of stone castles, both responses to the defeat of the Hungarian Kingdom in 1241. The failed Mongol attack on Hungary greatly reduced the Golden Horde's military power and caused them to stop disputing Hungarian borders.[75][82]

Against Serbia (1291)

In 1291 a large Mongol-Bulgarian alliance raided into Serbia, where Serbian king Stefan Uroš II Milutin defeated the Mongolian contingent. However, after a threat that Nogai himself will return with the Golden Horde, the Serbian king acknowledged Nogai's supremacy and sent his son as hostage to prevent further hostility when Nogai threatened to lead a punitive expedition himself.[83]

Against Germany (1340)

Contemporary Swiss historian John of Winterthur reports attacks by the Mongols on Hungary, the March of Brandenburg and Prussia during the period of 1340-1341.[84]

Counter-invasions of Europe

By the mid-14th century the grip of the Golden Horde over Central and Eastern Europe had started to weaken. Several European kingdoms started various incursions into Mongol-controlled lands with the aim of reclaiming captured territories as well as adding new ones from the Empire itself. The Kingdom of Georgia, under the leadership of King George V the Brilliant, restored Georgian dominance in their own lands and even took the Empire of Trebizond from Mongol hands.[85] Lithuania, taking advantage of internal strifes in the Golden Horde, started an invasion of their own, defeating the Mongols at the Battle at Blue Waters, as well as conquering territories of the Golden Horde such as the Principality of Kiev all the way to the Dnieper River, before being halted after their defeat at the Battle of the Vorskla River.[86][87] The Duchy of Moscow also started to reclaim many Rus' lands, eventually developing into the Tsardom of Russia. In 1345, the Kingdom of Hungary took the initiative and launched their own invasion force into Mongolian territory, capturing what would become Moldavia.[88]

By this point, some Western European armies also started to meet the Mongols in their conquered territories. In Caffa in Crimea for example, when the Mongols under Janibeg besieged it after a large fight between Christians and Muslims began, a relief force of an Genoese army came and defeated the Mongols, killing 15,000 of their troops and destroying their siege engines. A year later, the Genoese blockaded Mongol ports in the region, forcing Janibeg to negotiate, and in 1347 the Genoese were allowed to reestablish their colony in Tana on the Sea of Azov.[89]

Gallery

Golden Horde raid at old Ryazan.

Golden Horde raid at old Ryazan. Golden Horde raid at Kiev

Golden Horde raid at Kiev Golden Horde raid at Kozelsk

Golden Horde raid at Kozelsk Golden Horde raid Vladimir

Golden Horde raid Vladimir Golden Horde raid Suzdal

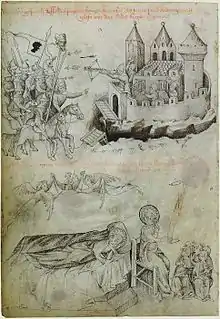

Golden Horde raid Suzdal The Hungarian King Béla IV on the flight from the Mongols under general Kadan of the Golden Horde.

The Hungarian King Béla IV on the flight from the Mongols under general Kadan of the Golden Horde.

See also

- Franco-Mongol alliance

- List of conflicts in Europe during Turco-Mongol rule

- Mongol invasions

- Mongol military tactics and organization

- Romania in the Early Middle Ages

- Timeline of the Mongol Empire

References

Citations

- Thomas T. Allsen (March 25, 2004). Culture and Conquest in Mongol Eurasia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521602709.

- Francis Dvornik (1962). The Slavs in European History and Civilization. Rutgers UP. p. 26. ISBN 9780813507996.

- Michell, Robert; Forbes, Nevell (1914). "The Chronicle of Novgorod 1016–1471". Michell. London, Offices of the society. p. 64. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- Eddie Austerlitz (2010). History of the Ogus. p. 27. ISBN 9781450729345.

- Bitwa pod Legnicą Chwała Oręża Polskiego Nr 3. Rzeczpospolita and Mówią Wieki. Primary author Rafał Jaworski. 12 August 2006 (in Polish) p. 8

- Bitwa pod Legnicą Chwała Oręża Polskiego Nr 3. Rzeczpospolita and Mówią Wieki. Primary author Rafał Jaworski. 12 August 2006 (in Polish) p. 4

- "Hungary – Culture, History, & People". britannica.com. Archived from the original on May 12, 2008. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- Hildinger, Erik. Mongol Invasions: Battle of Liegnitz Archived 2008-07-22 at the Wayback Machine. First published as: "The Mongol Invasion of Europe" in Military History, (June, 1997).

- The Destruction of Kiev Archived 2011-04-27 at archive.today

- Trawinski, Allan. The Clash of Civilizations. Page Publishing, Inc. (March 20, 2017). Section 15. ISBN 978-1635687118

- de Hartog, Leo. Genghis Khan: Conqueror of the World. Tauris Parke Paperbacks (January 17, 2004). p. 173. ISBN 978-1860649721

- Hildinger, Eric. Warriors Of The Steppe: Military History Of Central Asia, 500 Bc To 1700 Ad. Da Capo Press; 3rd printing edition (July 21, 1997). p. 144. ISBN 978-1885119438

- Hickman, Kenneth. "Mongol Invasions: Battle of Legnica". ThoughtsCO.com. Archived from the original on April 29, 2017. August 29, 2016

- Zimmermann, Wilhelm. A Popular History of Germany from the Earliest Period to the Present Day . Nabu Press (February 24, 2010). p. 1109. ISBN 978-1145783386

- Maurice, Charles Edmund. The Story of Bohemia from the Earliest Times to the Fall of National Independence in 1620: With a Short Summary of Later Events – Primary Source Edition. Nabu Press (March 18, 2014). p. 75. ISBN 978-1294890225

- Berend, Nora, Central Europe in the High Middle Ages: Bohemia, Hungary and Poland, c.900–c.1300 . Cambridge University Press (February 17, 2014). p. 447. ISBN 978-0521786959

- Długosz, The Annals, 181.

- "Christianity, Europe, and (Utraquist) Bohemia" (PDF). brrp.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- Epure, Violeta-Anca. "Invazia mongolă în Ungaria şi spaţiul românesc" (PDF). ROCSIR – Revista Româna de Studii Culturale (pe Internet) (in Romanian). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 14, 2015. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- "Genghis Khan: his conquest, his empire, his legacy"by Frank Lynn

- Michael Prawdin, Gerard (INT) Chaliand The Mongol Empire, p.268

- Richard Bessel; Dirk Schumann (2003). Life after death: approaches to a cultural and social history of Europe during the 1940s and 1950s. Cambridge University Press. pp. 143–. ISBN 978-0-521-00922-5. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- Gloria Skurzynski (2010). This Is Rocket Science: True Stories of the Risk-Taking Scientists Who Figure Out Ways to Explore Beyond Earth (illustrated ed.). National Geographic Books. p. 1958. ISBN 978-1-4263-0597-9. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

In A.D. 1232 an army of 30,000 Mongol warriors invaded the Chinese city of Kai-fung-fu, where the Chinese fought back with fire arrows...Mongol leaders learned from their enemies and found ways to make fire arrows even more deadly as their invasion spread toward Europe. On Christmas Day 1241 Mongol troops used fire arrows to capture the city of Buda in Hungary, and in 1258 to capture the city of Baghdad in what's now Iraq.

- Stephen Pow, Lindsay – Deep Ditches and Well-built walls. pp. 72, 132

- Z. J. Kosztolnyik -- Hungary in the 13th Century, East European Monographs, 1996. p. 174

- "Croatia (History)". Encarta. Archived from the original on October 31, 2009.

- Ltd., ICB - InterConsult Bulgaria. "CEEOL - Obsolete Link". www.ceeol.com. Archived from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- "Croatia (History)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on August 14, 2014.

- 750th Anniversary of the Golden Bull Granted by Bela IV Archived April 28, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- Klaić V., Povijest Hrvata, Knjiga Prva, Druga, Treća, Četvrta i Peta Zagreb 1982(in Croatian)

- Thomas of Split, Historia Salonitana.

- "Klis – A gateway to Dalmatia" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 18, 2011.

- Saunders, J. J. (1971). The History of the Mongol Conquests. Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 85. ISBN 9780710070739.

- McLynn, Frank. Genghis Khan: his conquest, his empire, his legacy.

- "Map Walk 20132013: The Conquests of the Mongols". Cleveland History. Archived from the original on March 9, 2017.

- Saunders, J. J. (1971). The History of the Mongol Conquests. Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 9780710070739.

- Jackson, Peter. The Mongols and the West: 1221–1410. Routledge; 1 edition (April 9, 2005). p. 67. ISBN 978-0582368965

- Howorth, Henry Hoyle. History of the Mongols from the 9th to the 19th Century: Part 1 the Mongols Proper and the Kalmyks. Cosimo Classics (January 1, 2013). p. 152. ISBN 978-1605201337

- Giessauf, Johannes (1997). "Herzog Friedrich II von Österreich und die Mongolengefahr 1241/42" (PDF). In H. Ebner; W. Roth (eds.). Forschungen zur Geschichte des Alpen-Adria-Raumes. Graz. pp. 173–199 [1–30].

- Howorth, Sir Henry Hoyle. History of the Mongols: From the 9th to the 19th Century, Volume 1. Forgotten Books (June 15, 2012). p. 152. ASIN B008HHQ8ZY

- Андреев (Andreev), Йордан (Jordan); Лалков (Lalkov), Милчо (Milcho) (1996). Българските ханове и царе (The Bulgarian Khans and Tsars) (in Bulgarian). Велико Търново (Veliko Tarnovo): Абагар (Abagar). ISBN 954-427-216-X.pp. 192–193

- Peter Jackson. The Mongols and the West: 1221–1410. 2005. p.65

- Jackson, p.79

- Jackson, p.105

- Encyclopædia Britannica, inc (2003). The New Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 663. ISBN 978-0-85229-961-6.

- Peter F. Sugar, Péter Hanák, Tibor Frank – A History of Hungary. p.27: "The majority of the Hungarian forces consisted of light cavalry, who appeared 'foreign' to the Western observers. Yet this army had given up nomadic battle tactics and proved useless when facing the masters of this style of warfare. Hungarian tactics were a mix of eastern and western military traditions, as were the ineffective walls of clay bricks and palisades. Two elements of the Hungarian defense had proved effective, however: close combat with mass armored knights and stone fortifications".

- Jackson, Peter (2005). The Mongols and the West, 1221–1410. Longman. p. 205. ISBN 0-582-36896-0.

- Peter F. Sugar, Péter Hanák, Tibor Frank – A History of Hungary pp. 28–29

- Stephen Pow, Lindsay – Deep Ditches and Well-built walls pp. 59, 76

- Z. J. Kosztolnyik – Hungary in the 13th Century, East European Monographs, 1996, p. 286

- Peter Jackson. The Mongols and the West: 1221–1410. 2005. p.205

- Anchalabze, George. The Vainakhs. Page 24

- Klaić V., Povijest Hrvata, Knjiga Prva, Druga, Treća, Četvrta i Peta Zagreb 1982. (Croatian)

- Michael Kohn (2006). Dateline Mongolia: An American Journalist in Nomad's Land. RDR Books. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-57143-155-4. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- William H. McNeill (1992). The Rise of the West: A History of the Human Community. University of Chicago Press. p. 492. ISBN 978-0-226-56141-7. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- Robert Cowley (1993). Robert Cowley (ed.). Experience of War (reprint ed.). Random House Inc. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-440-50553-2. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- Kenneth Warren Chase (2003). Firearms: a global history to 1700 (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-521-82274-9. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- Kelly (2005), p.23

- John of Plano Carpini, "History of the Mongols," in The Mission to Asia, ed. Christopher Dawson (London: Sheed and Ward, 1955), 44

- Carpini, History of the Mongols, 60; Pow, Deep ditches and well-built walls, pp. 19-21

- Rashid al-Din, Successors, 70–71.

- Rashid al-Din, Successors, 10–11. Translated by John Andrew Boyle. Boyle's preamble notes: "There are not infrequent interpolations from the Mongolian chronicle, and he even adopts its faulty chronology, in accordance with which the events of the European campaign take place a year later than in reality. In the present volume, Juvaini is down to the reign of Mongke (1251–1259) Rashid al-Din's main authority, but with considerable additional material from other sources. Thus the earlier historian's account of the invasion of eastern Europe (1241–1242) is repeated almost verbatim and is then followed, in a later chapter, by a much more detailed version of the same events, based, like the preceding description of the campaigns in Russia (1237–1240), on Mongol records, as is evident from the orthography of the proper names."

- "Climate probably stopped Mongols cold in Hungary, Science News, Science Ticker: Climate, Anthropology". By Helen Thompson. 2016. Archived from the original on August 3, 2016. Retrieved May 26, 2016.

- Rashid al-Din, Successors, 71–72.

- Büntgen, Ulf; Di Cosmo, Nicola (May 26, 2016). "Climatic and environmental aspects of the Mongol withdrawal from Hungary in 1242 CE". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 25606. Bibcode:2016NatSR...625606B. doi:10.1038/srep25606. PMC 4881396. PMID 27228400.

- J. J. Saunders, The History of the Mongol Conquests (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1971), 79.

- Climate

- Rain#Wettest known locations

- Sir John Keegan (1987) The Mask of Command, Viking: London, page 118

- "The Mongols in the West, Journal of Asian History v.33. n.1". By Denis Sinor. 1999. Archived from the original on September 1, 2009. Retrieved August 16, 2009.

- Amitai-Preiss, Reuven. The Mamluk-Ilkhanid War

- Frank McLynn, Genghis Khan (2015); Chris Peers, the Mongol War Machine (2015); Timothy May, the Mongol Art of War (2016). pp. 448–51

- Frank McLynn, Genghis Khan (2015); Chris Peers, the Mongol War Machine (2015); Timothy May, the Mongol Art of War (2016). pp. 450–1.

- Peter Jackson, "The Mongols and the West", 2005. Page 199

- Victor Spinei. "Moldavia in the 11th–14th centuries." Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste România. Bucharest, 1986. Pages 121–122.

- Stanisław Krakowski, Polska w walce z najazdami tatarskimi w XIII wieku, MON, 1956, pp. 181–201

- Stanisław Krakowski, Polska w walce z najazdami tatarskimi w XIII wieku, MON, 1956.

- René Grousset The Empire of Steppes, page 399–400

- Denis Sinor, "The Mongols in the West." Journal of Asian History (1999) pp: 1–44.

- Андреев (Andreev), Йордан (Jordan); Лалков (Lalkov), Милчо (Milcho) (1996). Българските ханове и царе (The Bulgarian Khans and Tsars) (in Bulgarian). Велико Търново (Veliko Tarnovo): Абагар (Abagar). ISBN 954-427-216-X.pp. 222

- Pál Engel, Tamás Pálosfalvi, Andrew Ayton: The Realm of St. Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895-1526, I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd, London, pp. 109

- The Roots of Balkanization: Eastern Europe C.E. 500–1500 – By Ion Grumeza Google Books.

- István Vásáry Cumans and Tatars: Oriental military in the pre-Ottoman Balkans, 1185–1365, p.89

- Jackson, Peter (2005). The Mongols and the West, 1221–1410. Routledge. pp. 206, 227.

- D. Kldiashvili, History of the Georgian Heraldry, Parlamentis utskebani, 1997, p. 35.

- Cherkas, Borys (December 30, 2011). Битва на Синіх Водах. Як Україна звільнилася від Золотої Орди [Battle at Blue Waters. How Ukraine freed itself from the Golden Horde] (in Ukrainian). istpravda.com.ua. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- Sedlar, Jean W. (1994). East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000–1500. University of Washington Press. p. 380. ISBN 0-295-97290-4.

- Kortüm, Hans-Henning. Transcultural Wars: from the Middle Ages to the 21st Century Akademie Verlag (March 22, 2006). p. 227

- Wheelis, Mark (September 1, 2002). "Biological Warfare at the 1346 Siege of Caffa". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 8 (9): 971–975. doi:10.3201/eid0809.010536. PMC 2732530. PMID 12194776.

Sources

- Sverdrup, Carl (2010). "Numbers in Mongol Warfare". Journal of Medieval Military History. Boydell Press. 8: 109–17 [p. 115]. ISBN 978-1-84383-596-7.

Further reading

- Allsen, Thomas T. (March 25, 2004). Culture and Conquest in Mongol Eurasia. Cambridge UP. ISBN 9780521602709.

- Atwood, Christopher P. Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire (2004)

- Chambers, James. The Devil's Horsemen: The Mongol Invasion of Europe (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1979)

- Christian, David. A History of Russia, Central Asia and Mongolia Vol. 1: Inner Eurasia from Prehistory to the Mongol Empire (Blackwell, 1998)

- Cook, David, "Apocalyptic Incidents during the Mongol Invasions", in Brandes, Wolfram / Schmieder, Felicitas (hg), Endzeiten. Eschatologie in den monotheistischen Weltreligionen (Berlin, de Gruyter, 2008) (Millennium-Studien / Millennium Studies / Studien zu Kultur und Geschichte des ersten Jahrtausends n. Chr. / Studies in the Culture and History of the First Millennium C.E., 16), 293–312.

- Halperin, Charles J. Russia and the golden horde: the Mongol impact on medieval Russian history (Indiana University Press, 1985)

- May, Timothy. The Mongol conquests in world history (Reaktion Books, 2013)

- Morgan, David. The Mongols, ISBN 0-631-17563-6

- Nicolle, David. The Mongol Warlords, Brockhampton Press, 1998

- Reagan, Geoffry. The Guinness Book of Decisive Battles, Canopy Books, New York (1992)

- Saunders, J.J. The History of the Mongol Conquests, Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, 1971, ISBN 0-8122-1766-7

- Sinor, Denis (1999). "The Mongols in the West". Journal of Asian History. 33 (1).; also in JSTOR

- Vernadsky, George. The Mongols and Russia (Yale University Press, 1953)

- Halperin, Charles J. "George Vernadsky, Eurasianism, the Mongols, and Russia." Slavic Review (1982): 477–493. in JSTOR

- Craughwell, Thomas J. (February 1, 2010). The Rise and Fall of the Second Largest Empire in History: How Genghis Khan almost conquered the world. Fair Winds. ISBN 9781616738518.

- Kauffman, JE (April 14, 2004). The medieval Fortress:Castles, Forts and Walled Cities of the medieval ages. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81358-0.\

- Fagan, Brian (August 1, 2010). The Great Warming:Climate Change and the Rise and Fall of Civilization. Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1-59691-780-4.

- Penn, Imma (2007). Dogma Evolution & Papal Fallacies:An Unveiled History of Catholicism. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4343-0874-0.