Mohamed Atta

Mohamed Mohamed el-Amir Awad el-Sayed Atta (/ˈætɑː/ AT-ah; Arabic: محمد محمد الأمير عوض السيد عطا [mæˈħæmmæd elʔæˈmiːɾ ˈʕɑwɑdˤ esˈsæj.jed ˈʕɑtˤɑ]; September 1,[1] 1968 – September 11, 2001) was an Egyptian Islamist and the ringleader of the September 11 attacks in 2001 where which four United States airliners were commandeered with the intention of destroying specific civilian, military, and governmental targets. He was the hijacker-pilot of American Airlines Flight 11 which he crashed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center as part of the coordinated attacks.[2][3][4][5][6] At 33 years of age, he was the oldest of the 19 hijackers who took part in the attacks. Atta was directly responsible for the deaths of more than 1,600 people during the attacks.

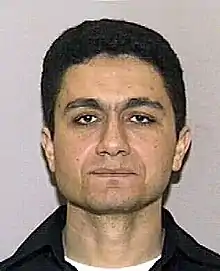

Mohamed Atta | |

|---|---|

| محمد عطا | |

Atta in May 2001 | |

| Born | Mohamed Mohamed el-Amir Awad el-Sayed Atta September 1, 1968 Kafr el-Sheikh, Egypt |

| Died | September 11, 2001 (aged 33) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Plane crash, suicide |

| Nationality | Egyptian |

| Alma mater | Cairo University Hamburg University of Technology |

| Known for | Ringleader of the September 11 attacks as the hijacker-pilot of American Airlines Flight 11 |

Born and raised in Egypt, Atta studied architecture at Cairo University, graduating in 1990, and continued his studies in Germany at the Hamburg University of Technology. In Hamburg, Atta became involved with the al-Quds Mosque, where he met Marwan al-Shehhi, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, and Ziad Jarrah, together forming the Hamburg cell. Atta disappeared from Germany for periods of time, embarking on the hajj in 1995 but also meeting Osama bin Laden and other top al-Qaeda leaders in Afghanistan from late-1999 to early-2000. Atta and the other Hamburg cell members were recruited by bin Laden and Khalid Sheikh Mohammed for a "planes operation" in the United States. Atta returned to Hamburg in February 2000, and began inquiring about flight training in the United States.

In June 2000, Atta, Ziad Jarrah and Marwan al-Shehhi arrived in the United States to learn how to pilot planes, obtaining instrument ratings in November. Beginning in May 2001, Atta assisted with the arrival of the muscle hijackers, and in July he traveled to Spain to meet with bin al-Shibh to finalize the plot. In August 2001, Atta traveled as a passenger on several "surveillance" flights, to establish in detail how the attacks could be carried out.

On the morning of September 11, Atta boarded American Airlines Flight 11, which he and his team then hijacked. Atta took control of the plane and crashed it into the North Tower of the World Trade Center at 8:46 a.m.[7] The crash led to the collapse of the tower and the deaths of more than 1,600 people.

Aliases

Mohamed Atta had varied his name on documents, also using "Mehan Atta", "Mohammad El Amir", "Muhammad Atta", "Mohamed El Sayed", "Mohamed Elsayed", "Muhammad al-Amir", "Awag Al Sayyid Atta", and "Awad Al Sayad".[8] In Germany, he registered his name as "Mohamed el-Amir Awad el-Sayed Atta", and went by the name Mohamed el-Amir at the Hamburg University of Technology.[9] In his will, written in 1996, Atta gives his name as "Mohamed the son of Mohamed Elamir awad Elsayed".[10] Atta also claimed different nationalities, sometimes Egyptian and other times telling people he was from the United Arab Emirates.[9]

Early life

Atta was born on September 1, 1968, in Kafr el-Sheikh, located in Egypt's Nile Delta region.[9] His father, Mohamed el-Amir Awad el-Sayed Atta, was a lawyer, educated in both sharia and civil law. His mother, Bouthayna Mohamed Mustapha Sheraqi, came from a wealthy farming and trading family and was also educated. Bouthayna and Mohamed married when she was 14, via an arranged marriage. The family had few relatives on the father's side and kept their distance from Bouthayna's family. In-laws characterized Atta's father as "austere, strict, and private," and neighbors viewed the family as reclusive.[11] Atta was the only son; he had two older sisters who are both well-educated and successful in their careers — one as a medical doctor and the other as a professor.[12]

When Atta was ten, his family moved to the Cairo neighborhood of Abdeen, situated near the city center. His father, who kept the family ever insulated, forbade young Atta to fraternize with the other children in their neighborhood. Having little else to do, he mostly studied at home and easily excelled in school.[13][14] In 1985, Atta enrolled at Cairo University and focused his studies on engineering. He was among the highest-scoring students; by his senior year, he was admitted to an exclusive architecture program. After he graduated in 1990 with an architecture degree,[15] he joined the Engineers Syndicate, an organization under the control of the Muslim Brotherhood.[9] He then worked for several months at the Urban Development Center in Cairo, where he joined various building projects and dispatched diverse architectural tasks.[16] Also in 1990, Atta's family moved into the eleventh floor of an apartment building in the Egyptian city of Giza.[15][17]

Atta also got engaged to a woman lined up by his father and her family in Cairo, at late 1999, after coming back from Germany the same year. Although the marriage never happened, Atta's father mentioned they liked each other.[18]

Germany

Atta graduated from Cairo University with marks insufficient for the graduate program. As his father insisted that he go abroad for graduate studies, Atta, to this end, entered a German-language program at the Goethe Institute in Cairo.[19] In 1992, his father had overheard a German couple who were visiting Egypt's capital. The couple explained at dinner that they ran an exchange program and invited Atta to continue his studies in Germany; they also offered him room and board at their home in the city. Mohamed Atta accepted and was in Germany two weeks later, in July.

In Germany, he enrolled in the urban planning graduate program at the Hamburg University of Technology.[12] Atta initially lived with two high school teachers; however, they eventually found his closed-mindedness and introverted personality to be too much for them. Atta began adhering to the strictest Islamic diet, frequenting the most conservative mosques, socializing seldom, and acting disdainfully towards the couple's unmarried daughter who had a young child. After six months, they asked him to leave.[20][21][22]

By early 1993, Atta had moved into university housing with two roommates, in Centrumshaus. He stayed there until 1998. During that period, his roommates grew annoyed with him. He seldom bathed, and they could not bear his "complete, almost aggressive insularity".[23] He kept to himself to such an extent that he would often react to simple greetings with silence.

Academic studies

At the Hamburg University of Technology, Atta studied under the guidance of the department chair, Dittmar Machule, who specialized in the Middle East.[24] Atta was averse to modern development. This included the construction of high-rise buildings in Cairo and other ancient cities in the region. He believed that the drab and impersonal apartment blocks, built in the 60s and 70s, ruined the beauty of old neighborhoods and robbed their people of privacy and dignity. Atta's family moved into an apartment block in 1990; it was to him but "a shabby symbol of Egypt's haphazard attempts to modernize and its shameless embrace of the West."[15] For his thesis, Atta concentrated on the ancient Syrian city of Aleppo. He researched the history of the urban landscape in relation to the general theme of conflict between Arab and modern civilization. He criticized how the newfangled skyscrapers and other modernizing projects were disrupting the fabric of communities by blocking common streets and altering the skyline.

Atta's professor, Dittmar Machule, brought him along on an archaeological expedition to Aleppo in 1994.[25] The invitation had been for a three-day visit, but Atta ended up staying several weeks that August, only to visit Aleppo yet again that December.[26] While in Syria, he met Amal, a young Palestinian woman who worked for a planning bureau in the city. Volker Hauth, who was traveling with Atta, described Amal as "attractive and self-confident. She observed Muslim customs, taking taxis to and from the office so as not to come into close physical contact with men on buses. But she was also said to be 'emancipated' and 'challenging'. Atta and Amal appeared to be attracted to each other, but Atta soon decided that "she had a quite different orientation and that the emancipation of the young lady did not fit." His nascent infatuation with her, begrudgingly realised, was the closest thing Atta knew to romance.[9] In mid-1995, he stayed for three months in Cairo, on a grant from the Carl Duisberg Society, along with fellow students Volker Hauth and Ralph Bodenstein. The academic team inquired into the effects of redevelopment in the Islamic Cairo, the old quarter, which the government undertook to remodel for tourism. Atta stayed in Cairo awhile with his family after Hauth and Bodenstein flew back to Germany.[27][28]

While in Hamburg, Atta held several positions, such as one part-time job at Plankontor, as well as another at an urban planning firm, beginning in 1992. He was let go from the firm in 1997, however, because its business had declined and "his draughtsmanship was not needed" after it bought a CAD system.[9][29] Among other odd jobs to supplement his income, Atta sometimes worked at a cleaning company and sometimes bought and sold cars.[30] Atta had harbored a desire to return to his native city, ever since he finished his studies in Hamburg; but he was prevented by the dearth of job prospects in Cairo, his family lacking the "right connections" to avail the customary nepotism.[31][32] Further, after the Egyptian government had imprisoned droves of political activists, he knew better than to trust it not to target him too, with his social and political beliefs being such as they were.[33]

Religious zeal and Hamburg cell

After coming to Hamburg in 1992, Atta grew more religiously fanatical and frequented the mosque with greater regularity.[34] His friends in Germany described him as an intelligent man in whom religious convictions and political motives held equal sway. He harbored anger and resentment toward the U.S. for its policy in Islamic nations of the Middle East, with nothing inflaming his ire more than the Oslo Accords and the Gulf War in particular.[35][36] He was also angry and bitter at the elite in his native Egypt, who he believed hoarded power for themselves, as well as at the Egyptian government, that cracked down on the dissident Muslim Brotherhood.[37] Atta was anti-Semitic, believing that Jews controlled the world's media, financial, and political institutions from New York City.[38] These beliefs were even stronger during Operation Infinite Reach, which he believed that Monica Lewinsky was a Jewish agent influencing Bill Clinton against aiding Palestine, which would later play a key role in creating the Hamburg Cell.[39]

On August 1, 1995, Atta returned to Egypt for three months of study.[40] Before this trip he grew out a beard, with a view to show himself as a devout Muslim and to make a political gesture thereby.[30][41] Atta returned to Hamburg on October 31, 1995,[40] only to join the pilgrimage to Mecca shortly thereafter.[30]

In Hamburg, Atta was intensely drawn to al-Quds Mosque which adhered to a "harsh, uncompromisingly fundamentalist, and resoundingly militant" version of Sunni Islam.[42] He made acquaintances at al-Quds; some of whom visited him on occasion at Centrumshaus. He also began teaching classes both at Al-Quds and at a Turkish mosque near the Harburg district. Atta also started and led a prayer group, which Ahmed Maklat and Mounir El Motassadeq joined. Ramzi bin al-Shibh was also there, teaching occasional classes, and became Atta's friend.[43]

On April 11, 1996, Atta signed his last will and testament at the mosque, officially declaring his Muslim beliefs and giving 18 instructions regarding his burial.[10][44] This was the same day that Israel, much to the outrage of Atta, attacked Lebanon in Operation Grapes of Wrath; signing the will "offering his life" was his response.[38] The instructions in his last will and testament reflect both Sunni funeral practices along with some more puritanical demands from Salafism, including asking people not "to weep and cry" and to generally refrain from showing emotion. The will was signed by el-Motassadeq and a second person at the mosque.[45]

After leaving Plankontor in the summer of 1997, Atta disappeared again and did not return until 1998. He had made no progress on his thesis. Atta phoned his graduate advisor, Machule, and mentioned family problems at home, saying, "Please understand, I don't want to talk about this."[46][47] At the winter break in 1997, Atta left and did not return to Hamburg for three months. He said that he went on pilgrimage to Mecca again, just 18 months after his first time. This claim has been disputed; Terry McDermott has argued that it is unusual for someone to go on pilgrimage so soon after the first time and to spend three months there (more than Hajj requires). When Atta returned, he claimed that his passport was lost and applied for a new one, which is a common tactic to erase evidence of travel to places such as Afghanistan.[48] When he returned in spring 1998, after disappearing for several months, he had grown a thick long beard, and "seemed more serious and aloof" than before to those who knew him.[30]

By mid-1998, Atta was no longer eligible for university housing in Centrumshaus. He moved into a nearby apartment in the Wilhelmsburg district, where he lived with Said Bahaji and Ramzi bin al-Shibh. By early 1999, Atta had completed his thesis, and formally defended it in August 1999.[47]

In mid-1998, Atta worked alongside Shehhi, bin al-Shibh, and Belfas, at a warehouse, packing computers in crates for shipping.[49] The Hamburg group did not stay in Wilhelmsburg for long. The next winter, they moved into an apartment at Marienstrasse 54 in the borough of Harburg, near the Hamburg University of Technology,[50] at which they enrolled. It was here that the Hamburg cell developed and acted more as a group.[51] They met three or four times a week to discuss their anti-American feelings and to plot possible attacks. Many al-Qaeda members lived in this apartment at various times, including hijacker Marwan al-Shehhi, Zakariya Essabar, and others.

In late 1999, Atta, Shehhi, Jarrah, Bahaji, and bin al-Shibh decided to travel to Chechnya to fight against the Russians, but were convinced by Khalid al-Masri and Mohamedou Ould Salahi at the last minute to change their plans. They instead traveled to Afghanistan over a two-week period in late November. On November 29, 1999, Mohamed Atta boarded Turkish Airlines Flight TK1662 from Hamburg to Istanbul, where he changed to flight TK1056 to Karachi, Pakistan.[4] After they arrived, they were selected by Al Qaeda leader Mohammed Atef as suitable candidates for the "planes operation" plot. They were all well-educated, had experience of living in western society, along with some English skills, and would be able to obtain visas.[38] Even before bin al-Shibh had arrived, Atta, Shehhi, and Jarrah were sent to the House of Ghamdi near bin Laden's home in Kandahar, where he was waiting to meet them. Bin Laden asked them to pledge loyalty and commit to suicide missions, which Atta and the other three Hamburg men all accepted. Bin Laden sent them to see Atef to get a general overview of the mission, and then they were sent to Karachi to see Khalid Sheikh Mohammed to go over specifics.[52]

German investigators said that they had evidence that Mohamed Atta trained at al-Qaeda camps in Afghanistan from late 1999 to early 2000. The timing of the Afghanistan training was outlined on August 23, 2002, by a senior investigator. The investigator, Klaus Ulrich Kersten was the director of Germany's federal anticrime agency, the Bundeskriminalamt. He provided the first official confirmation that Atta and two other pilots had been in Afghanistan, and he also provided the first dates of the training. Kersten said in an interview at the agency's headquarters in Wiesbaden that Atta was in Afghanistan from late 1999 until early 2000,[53][54] and that there was evidence that Atta met with Osama bin Laden there.[55]

A video surfaced in October 2006. The first chapter of the video showed bin Laden at Tarnak Farms on January 8, 2000. The second chapter showed Atta and Ziad Jarrah reading their wills together ten days later on January 18.[4][56] On his return journey, Atta left Karachi on February 24, 2000, by flight TK1057 to Istanbul where he changed to flight TK1661 to Hamburg.[4] Immediately after returning to Germany, Atta, al-Shehhi, and Jarrah reported their passports stolen, possibly to discard travel visas to Afghanistan.[57]

United States

On March 22, 2000, Atta was still in Germany when he sent an e-mail to the Academy of Lakeland in Florida. He inquired about flight training, "Dear sir, we are a small group of young men from different Arab countries. Now, we are living in Germany since a while for study purposes. We would like to start training for the career of airline professional pilots. In this field, we haven't yet any knowledge but we are ready to undergo an intensive training program (up to ATP and eventually higher)." Atta sent 50–60 similar e-mails to other flight training schools in the United States.[58]

On May 17, Atta applied for a United States visa. The next day, he received a five-year B-1/B-2 (tourist/business) visa from the United States embassy in Berlin. Atta had lived in Germany for approximately five years and also had a "strong record as a student". He was therefore treated favorably and not scrutinized.[59] After obtaining his visa, Atta took a bus on June 2 from Hamburg to Prague where he stayed overnight before traveling on to the United States the next day. Bin al-Shibh later explained that they believed it would contribute to operational security for Atta to fly out of Prague instead of Hamburg, where he traveled from previously. Likewise, Shehhi traveled from a different location, in his case via Brussels.[60][61]

On June 6, 2002, ABC's World News Tonight broadcast an interview with Johnelle Bryant, former loan officer at the U.S. Department of Agriculture in south Florida, who told about her encounter with Mohamed Atta. This encounter took place "around the third week of April to the third week of May of 2000", before Atta's official entry date into the United States (see below). According to Bryant, Atta wanted to finance the purchase of a crop-duster. "He wanted to finance a twin-engine, six-passenger aircraft and remove the seats," Bryant told ABC's World News Tonight. He insisted that she write his name as ATTA, that he originally was from Egypt but had moved to Afghanistan, that he was an engineer and that his dream was to go to a flight school. He asked about the Pentagon and the White House. He said he wanted to visit the World Trade Center and asked Bryant about the security there. He mentioned Al Qaeda and said the organization "could use memberships from Americans". He mentioned Osama bin Laden and said "this man would someday be known as the world's greatest leader." Bryant said "the picture that came out in the newspaper, that's exactly what that man looked like."[62][63] Bryant contacted the authorities after recognising Atta in news reports.[64] Law-enforcement officials said Bryant passed a lie-detector exam.[65]

According to official reports, Atta flew from Prague to Newark International Airport, arriving on June 3, 2000. That month, Atta and Shehhi stayed in hotels and rented rooms in New York City on a short-term basis. Jarrah had arrived in the United States on June 27, 2000, after his flight landed at Newark, New Jersey, and Jarrah had decided to go with Shehhi and Atta to search for different flight schools in the US. They continued to inquire about flight schools and personally visited some, including Airman Flight School in Norman, Oklahoma, which they visited on July 3, 2000. Days later, Shehhi, Jarrah and Atta ended up in Venice, Florida.[16] Atta and Shehhi established accounts at SunTrust Bank and received wire transfers from Ali Abdul Aziz Ali, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed's nephew in the United Arab Emirates.[16][60] On July 6, 2000, Atta, Jarrah and Shehhi enrolled at Huffman Aviation in Venice, where they entered the Accelerated Pilot Program.[16] When Atta and Shehhi arrived in Florida, they initially stayed with Huffman's bookkeeper and his wife in a spare room of their house. After a week, they were asked to leave because they were rude. Atta and Shehhi then moved into a small house nearby in Nokomis where they stayed for six months.[66][67]

Atta began flight training on July 6, 2000, and continued training nearly every day. By the end of July, both Atta and Shehhi did solo flights. Atta earned his private pilot certificate in September, and then he and Shehhi decided to switch flight schools. Both enrolled at Jones Aviation in Sarasota and took training there for a brief time. They had problems following instructions and were both very upset when they failed their Stage 1 exam at Jones Aviation. They inquired about multi-engine planes and told the instructor that "they wanted to move quickly, because they had a job waiting in their country upon completion of their training in the U.S." In mid-October, Atta and Shehhi returned to Huffman Aviation to continue training. In November 2000, Atta earned his instrument rating, and then a commercial pilot's license in December from the Federal Aviation Administration.[16]

Atta continued with flight training that included solo flights and simulator time. On December 22, Atta and Shehhi applied to Eagle International for large jet and simulator training for McDonnell Douglas DC-9 and Boeing 737-300 models. On December 26, Atta and Shehhi needed a tow for their rented Piper Cherokee on a taxiway of Miami International Airport after the engine shut down. On December 29 and 30, Atta and Marwan went to the Opa-locka Airport where they practiced on a Boeing 727 simulator, and they obtained Boeing 767 simulator training from Pan Am International on December 31. Atta purchased cockpit videos for Boeing 747-200, Boeing 757-200, Airbus A320 and Boeing 767-300ER models via mail-order from Sporty's Pilot Shop in Batavia, Ohio, in November and December 2000.[16]

Records on Atta's cellphone indicated that he phoned the Moroccan embassy in Washington on January 2, just before Shehhi flew to the country. Atta flew to Spain on January 4, 2001, to coordinate with bin al-Shibh and returned to the United States on January 10. While in the United States he traveled to Lawrenceville, Georgia, where he and Shehhi visited an LA Fitness Health Club. During that time Atta flew out of Briscoe Field in Lawrenceville with a pilot, and Atta and either the pilot or Shehhi flew around the Atlanta area. They lived in the area for several months. On April 3, Atta and Shehhi rented a postal box in Virginia Beach, Virginia.

On April 11, Atta and Shehhi rented an apartment at 10001 Atlantic Blvd, Apt. 122 in Coral Springs, Florida, for $840 per month,[68] and assisted with the arrival of the muscle hijackers. On April 16, Atta was given a citation for not having a valid driver's license, and he began steps to get the license. On May 2, Atta received his driver's license in Lauderdale Lakes, Florida. While in the United States, Atta owned a red 1989 Pontiac Grand Prix.[69]

On June 27, Atta flew from Fort Lauderdale to Boston, Massachusetts, where he spent a day, and then continued to San Francisco for a short time, and from there to Las Vegas. On June 28, Atta arrived at McCarran International Airport in Las Vegas to meet with the three other pilots. He rented a Chevrolet Malibu from an Alamo Rent A Car agency. It is not known where he stayed that night, but on the 29th he registered at the Econo Lodge at 1150 South Las Vegas Boulevard. Here he presented an AAA membership for a discount, and paid cash for the $49.50/night room. During his trip to Las Vegas, he is thought to have used a video camera that he had rented from a Select Photo outlet back in Delray Beach, Florida.[70]

July 2001 summit in Spain

In July 2001, Atta again left for Spain in order to meet with bin al-Shibh for the last time. On July 7, 2001, Atta flew on Swissair Flight 117 from Miami to Zürich, where he had a stopover.[71] On July 8, Atta was recorded on surveillance video when he withdrew 1700 Swiss francs from an ATM. He used his credit card to purchase two Swiss Army knives and some chocolate in a shop at the Zürich Airport.[72] After the stopover in Zürich, he arrived in Madrid at 4:45 pm on Swissair Flight 656, and spent several hours at the airport. Then at 8:50 pm, he checked into the Hotel Diana Cazadora in Barajas, a town near the airport. That night and twice the next morning, he called Bashar Ahmad Ali Musleh, a Jordanian student in Hamburg who served as a liaison for bin al-Shibh.[73]

On the morning of July 9, Mohamed Atta rented a silver Hyundai Accent, which he booked from SIXT Rent-A-Car for July 9 to 16, and later extended to the 19th.[73][74] He drove east out of Madrid towards the Mediterranean beach area of Tarragona. On the way, Atta stopped in Reus to pick up Ramzi bin al-Shibh at the airport. They drove to Cambrils, where they spent a night at the Hotel Monica. They checked out the next morning, and spent the next few days at an unknown location in Tarragona.[73] The absence of other hotel stays, signed receipts or credit card stubs has led investigators to believe that the men may have met in a safe house provided by other al-Qaeda operatives in Spain. There, Atta and bin al-Shibh held a meeting to complete the planning of the attacks. Several clues have been found to link their stay in Spain to Syrian-born Imad Eddin Barakat Yarkas (Abu Dahdah), and Amer el Azizi, a Moroccan in Spain. They may have helped arrange and host the meeting in Tarragona.[75] Yosri Fouda, who interviewed bin al-Shibh and Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM) before the arrest, believes that Said Bahaji and KSM may have also been present at the meeting. Spanish investigators have said that Marwan al-Shehhi and two others later joined the meeting. Bin al-Shibh would not discuss this meeting with Fouda.[76]

During the Spain meetings, Atta and bin al-Shibh had coordinated the details of the attacks. The 9/11 Commission obtained details about the meeting, based on interrogations of bin al-Shibh in the weeks after his arrest in September 2002. Bin al-Shibh explained that he passed along instructions from Osama bin Laden, including his desire for the attacks to be carried out as soon as possible. Bin Laden was concerned about having so many operatives in the United States. Atta confirmed that all the muscle hijackers had arrived in the United States, without any problems, but said that he needed five to six more weeks to work out details. Bin Laden also asked that other operatives not be informed of the specific data until the last minute. During the meeting, Atta and bin al-Shibh also decided on the targets to be hit, ruling out a strike on a nuclear plant. Bin al-Shibh passed along bin Laden's list of targets; bin Laden wanted the U.S. Capitol, the Pentagon, and the World Trade Center to be attacked, as they were deemed "symbols of America." If any of the hijackers could not reach their intended targets, Atta said, they were to crash the plane. They also discussed the personal difficulties Atta was having with fellow hijacker Ziad Jarrah. Bin al-Shibh was worried that Jarrah might even abandon the plan. The 9/11 Commission Report speculated that the now-convicted terrorist conspirator Zacarias Moussaoui was being trained as a possible replacement for Jarrah.[59][60]

From July 13 to 16, Atta stayed at the Hotel Sant Jordi in Tarragona.[73][74] After bin al-Shibh returned to Germany on July 16, 2001, Atta had three more days in Spain. He spent two nights in Salou at the beachside Casablanca Playa Hotel, then spent the last two nights at the Hotel Residencia Montsant.[77] On July 19, Atta returned to the United States, flying on Delta Air Lines from Madrid to Fort Lauderdale, via Atlanta.[74]

Final plans in the U.S.

On July 22, 2001, Atta rented a Mitsubishi Galant from Alamo Rent a Car, putting 3,836 miles (6,173 km) on the vehicle before returning it on July 26. On July 25, Atta dropped Ziad Jarrah off at Miami International Airport for a flight back to Germany. On July 26, Atta traveled via Continental Airlines to Newark, New Jersey, checked into the Kings Inn Hotel in Wayne, New Jersey, and stayed there until July 30 when he took a flight from Newark back to Fort Lauderdale.[16]

On August 4, Atta is believed to have been at Orlando International Airport waiting to pick up suspected "20th Hijacker" Mohammed al-Qahtani from Dubai, who ended up being held by immigration as "suspicious." Atta was believed to have used a payphone at the airport to phone a number "linked to al-Qaeda" after Qahtani was denied entry.[78]

On August 6, Atta and Shehhi rented a white, four-door 1995 Ford Escort from Warrick's Rent-A-Car, which was returned on August 13. On August 6, Atta booked a flight on Spirit Airlines from Fort Lauderdale to Newark, leaving on August 7 and returning on August 9. The reservation was not used and canceled on August 9 with the reason "Family Medical Emergency". Instead, he went to Central Office & Travel in Pompano Beach to purchase a ticket for a flight to Newark, leaving on the evening of August 7 and schedule to return in the evening on August 9. Atta did not take the return flight. On August 7, Atta checked into the Wayne Inn in Wayne, New Jersey and checked out on August 9. The same day, he booked a one-way first-class ticket via the Internet on America West Flight 244 from Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport to Las Vegas.[16] Atta traveled twice to Las Vegas on "surveillance flights" rehearsing how the 9/11 attacks would be carried out. Other hijackers traveled to Las Vegas at different times in the summer of 2001.

Throughout the summer, Atta met with Nawaf al-Hazmi to discuss the status of the operation on a monthly basis.[79]

On August 23, Atta's driver license was revoked in absentia after he failed to show up in traffic court to answer the earlier citation for driving without a license.[80] [81]

September 11 attacks and death

On September 10, 2001, Atta picked up Omari from the Milner Hotel in Boston, Massachusetts, and the two drove their rented Nissan Altima to a Comfort Inn in South Portland, Maine. On the way, they were seen getting gasoline at an Exxon gas station and visited the Longfellow House in Portland that afternoon;[82] they arrived at the hotel at 5:43 p.m. and spent the night in Room 233. While in South Portland, they were seen making two ATM withdrawals and stopping at Wal-Mart. The FBI also reported that "two middle-eastern men" were seen in the parking lot of a Pizza Hut, where Atta is known to have eaten that day.[83][84][85]

Atta and Omari arrived early the next morning, at 5:40 a.m., at the Portland International Jetport, where they left their rental car in the parking lot and boarded at 6:00 a.m. Colgan Air (US Airways Express) BE-1900C flight to Boston's Logan International Airport.[86] In Portland, Mohamed Atta was selected by the Computer Assisted Passenger Prescreening System (CAPPS), which required his checked bags to undergo extra screening for explosives but involved no extra screening at the passenger security checkpoint.[87]

The connection between the two flights at Logan International Airport was within Terminal B, but the two gates were not connected within security. Passengers must leave the secured area, go outdoors, cross a covered roadway, and enter another building before going through security once again. There are two separate concourses in Terminal B; the south concourse is mainly used by US Airways and the north one is mostly used by American Airlines. It had been overlooked that there would still be a security screen to pass in Boston because of this distinct detail of the terminal's arrangement. A ticket staffer at Portland Airport reported becoming uneasy with Atta's anger upon being told of the additional screening requirements in Boston, but that he did not act on his suspicions after becoming concerned that he was racially profiling Atta.[88] At 6:45 a.m., while at the Boston airport, Atta took a call from Flight 175 hijacker Marwan al-Shehhi. This call was apparently to confirm that the attacks were ready to begin. Atta checked in for American Airlines Flight 11, passed through security again, and boarded the flight. Atta was seated in business class, in seat 8D. At 7:59 a.m., the plane departed from Boston to Los Angeles International Airport, carrying 81 passengers.[86]

The hijacking began at 8:14 a.m. — 15 minutes after the flight departed — when beverage service would be starting. At this time, the pilots stopped responding to air traffic control, and the aircraft began deviating from the planned route.[7] At 8:18 am, flight attendants Betty Ong and Madeline Amy Sweeney began making phone calls to American Airlines to report what was happening. Ong provided information about lack of communication with the cockpit, lack of access to the cockpit, and passenger injuries.[86][89] At 8:24:38 a.m., a voice believed to be Atta's was heard by air traffic controllers, saying: "We have some planes. Just stay quiet and you will be OK. We are returning to the airport." "Nobody move, everything will be OK. If you try to make any moves you'll endanger yourself and the airplane. Just stay quiet." "Nobody move, please. We are going back to the airport. Don't try to make any stupid moves." The plane's transponder was turned off at 8:21 a.m. At 8:46:40 a.m., Atta crashed the plane into the North Tower of the World Trade Center in New York City.[90][7]

Because the flight from Portland to Boston had been delayed,[91] his bags did not make it onto Flight 11. Atta's bags were later recovered in Logan International Airport, and they contained airline uniforms, flight manuals, and other items. The luggage included a copy of Atta's will, written in Arabic, as well as a list of instructions, called "The Last Night". This document is divided into three sections; the first is a fifteen point list providing detailed instructions for the last night of a martyr's life, the second gives instructions for travelling to the plane and the third from the time between boarding the plane and martyrdom. Almost all of these points discuss spiritual preparation, such as prayer and citing religious scripture.[92]

Martyrdom video

On October 1, 2006, The Sunday Times released a video it had obtained "through a previously tested channel", purporting to show Mohamed Atta and Ziad Jarrah recording a martyrdom message six months earlier at a training camp in Afghanistan. The video, bearing the date of January 18, 2000, is of good resolution but contains no sound track. Lip readers have failed to decipher it. Atta and Jarrah appear in high spirits, laughing and smiling in front of the camera. They had never been pictured together before. Unidentified sources from both Al-Qaeda and the United States confirmed The Times the video's authenticity. A separate section of the video shows Osama bin Laden addressing his followers at a complex near Kandahar. Ramzi bin al-Shibh is also identified in the video. According to The Sunday Times, "American and German investigators have struggled to find evidence of Atta's whereabouts in January 2000 after he disappeared from Hamburg. The hour-long tape places him in Afghanistan at a decisive moment in the development of the conspiracy when he was given operational command. Months later both he and Jarrah enrolled at flying schools in America."[2][93]

Mistaken identity

In the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 attacks, the names of the hijackers were released. There was some confusion regarding who Mohamed Atta was, and cases of mistaken identity. Initially, Mohamed Atta's identity was confused with that of a native Jordanian, Mahmoud Mahmoud Atta, who bombed an Israeli bus in the West Bank in 1986, killing one and severely injuring three. Mahmoud Atta was 14 years older than Atta.[94] Mahmoud Atta, a naturalized U.S. citizen, was subsequently deported from Venezuela to the United States, extradited to Israel, tried and sentenced to life in prison. The Israeli Supreme Court later overturned his extradition and set him free.[95] After 9/11, there also were reports stating that Mohamed Atta had attended International Officers School at Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery, Alabama. The Washington Post quoted a United States Air Force official who explained, "discrepancies in their biographical data, such as birth dates 20 years off, indicate we are probably not talking about the same people."[96]

Prague controversy

In the months following the September 11 attacks, officials at the Czech Interior Ministry asserted that Atta made a trip to Prague on April 8, 2001, to meet with an Iraqi intelligence agent named Ahmed Khalil Ibrahim Samir al-Ani. This piece of information was passed on to the FBI as "unevaluated raw intelligence".[97] Intelligence officials have concluded that such a meeting did not occur. A Pakistani businessman named Mohammed Atta had come to Prague from Saudi Arabia on May 31, 2000, with this second Atta possibly contributing to the confusion. The Egyptian Mohamed Atta arrived at the Florenc bus terminal in Prague, from Germany, on June 2, 2000. He left Prague the next day, flying on Czech Airlines to Newark, New Jersey, U.S. In the Czech Republic, some intelligence officials say the source of the purported meeting was an Arab informant who approached the Czech intelligence service with his sighting of Atta only after Atta's photograph had appeared in newspapers all over the world. United States and Czech intelligence officials have since concluded that the person seen with Ani was mistakenly identified as Atta, and the consensus of investigators is that Atta never attended a meeting in Prague.[98][99][100]

Able Danger

In 2005, Army Lt. Col. Anthony Shaffer and Congressman Curt Weldon alleged that the Defense Department data mining project, Able Danger, produced a chart that identified Atta, along with Nawaf al-Hazmi, Khalid al-Mihdhar, and Marwan al-Shehhi, as members of a Brooklyn-based al-Qaeda cell in early 2000.[101] Shaffer largely based his allegations on the recollections of Navy Captain, Scott Phillpott,[102] who later recanted his recollection, telling investigators that he was "convinced that Atta was not on the chart that we had." Phillpott said that Shaffer was "relying on my recollection 100 percent," and the Defense Department Inspector General's report indicated that Philpott "may have exaggerated knowing Atta's identity because he supported using Able Danger's techniques to fight terrorism."[103][104]

Five witnesses who had worked on Able Danger and had been questioned by the Defense Department's Inspector General later told investigative journalists that their statements to the IG were distorted by investigators in the final IG's report, or the report omitted essential information that they had provided. The alleged distortions of the IG report centered around excluding any evidence that Able Danger had identified and tracked Atta years before 9/11.[105]

Lt. Col. Shaffer's book also clearly indicates direct identification of the Brooklyn cell, and Mohamed Atta.[106]

Family reaction and denial

Atta's father, Mohamed el-Amir Awad el-Sayed Atta, a retired lawyer in Egypt, vehemently rejected allegations his son was involved in the September 11 attacks, and instead accused the Mossad and the United States government of having a hand in framing his son.[32] Atta Sr. rejected media reports that stated his son was drinking wildly, and instead described his son as a quiet boy uninvolved with politics, shy and devoted to studying architecture.[107] The elder Mr. Atta said he had spoken with Mohamed by phone the day after on September 12, 2001. He held interviews with the German news magazine Bild am Sonntag in late 2002, saying his son was alive and hiding in fear for his life, and that American Christians were responsible for the attacks.[108] In an interview on September 24, 2001, Atta Sr. stated, "My son is gone. He is now with God. The Mossad killed him."[109]

In 2021, on the 20th anniversary of the attacks, Atta's mother was interviewed by a Spanish newspaper. His mother, 79, at the time denied her son's involvement in the attacks and that she feels he is in Afghanistan.[110]

Motivation

There are multiple, conflicting explanations for Atta's behavior and motivation. Political psychologist Jerrold Post has suggested that Atta and his fellow hijackers were just following orders from al-Qaeda leadership, "and whatever their destructive, charismatic leader Osama bin Laden said was the right thing to do for the sake of the cause was what they would do."[111] In turn, political scientist Robert Pape has claimed that Atta was motivated by his commitment to the political cause, that he was psychologically normal, and that he was "not readily characterized as depressed, not unable to enjoy life, not detached from friends and society."[112] By contrast, criminal justice professor, Adam Lankford, has found evidence that indicated Atta was suicidal, and that his struggles with social isolation, depression, guilt, shame, hopelessness, and rage were extraordinarily similar to the struggles of those who commit conventional suicide and murder-suicide. By this view, Atta's political and religious beliefs affected the method of his suicide and his choice of target, but they were not the underlying causes of his behavior.[113]

In popular culture

- Atta is played by Egyptian-born American musician and actor Kamel Boutros in the 2004 television film The Hamburg Cell.

- Atta appears as one of the hijackers aboard Flight 11 in the Family Guy episode, "Back to the Pilot". He is voiced by John Viener.[114]

See also

- Suicide attack

- PENTTBOM

- Hijackers in the September 11 attacks

Notes

- "Egypt's Lost Son: Mohamed el-Amir el-Sayyed Atta". January 24, 2021.

- Fouda, Yosri (October 1, 2006). "The laughing 9/11 bombers". The Sunday Times. London. Archived from the original on May 24, 2011. Retrieved September 4, 2010.

- Bernstein, Richard (September 10, 2002). "On Path to the U.S. Skies, Plot Leader Met bin Laden". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 17, 2009. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- Fouda, Yosri (October 1, 2006). "Chilling message of the 9/11 plots". The Sunday Times. London. Archived from the original on July 6, 2008. Retrieved September 24, 2008.

- "Video of 9/11 ringleader Mohammed Atta posted by British news site". USA Today. October 1, 2006. Archived from the original on December 2, 2008. Retrieved September 24, 2008.

- Ross, Brian (September 10, 2009). "FBI Informant Says Agents Missed Chance to Stop 9/11 Ringleader Mohammed Atta". ABC News. Archived from the original on December 30, 2013. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- "Flight Path Study – American Airlines Flight 11" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. February 19, 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 5, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- Cherry, Alan (September 28, 2001). "The Trail of Terror". Sun-Sentinel.

- Hooper, John (September 23, 2001). "The shy, caring, deadly fanatic". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on January 25, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- "Mohamed Atta's Last Will and Testament". PBS Frontline. Archived from the original on September 30, 2008. Retrieved August 1, 2008.

- McDermott (2005), p. 9-11

- Cloud, John (September 30, 2001). "Atta's Odyssey". Time. Archived from the original on December 10, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- McDermott (2005), p. 12-14

- "Transcript: A Mission to Die For". Four Corners / ABC (Australia). November 12, 2001. Archived from the original on September 17, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- "The Day That Changed America". Newsweek. December 31, 2001.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation (February 4, 2008). "Hijackers' Timeline" (PDF). 9/11 Myths. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 7, 2011. Retrieved August 1, 2008.

- Adams, Paul (September 4, 2002). "In Egypt, some see war on terror as a war on Islam". Globe and Mail. Canada. Archived from the original on March 14, 2008. Retrieved January 19, 2008.

- "A Perfect Soldier". Los Angeles Times. January 27, 2002.

- Fouda and Fielding (2003), p. 78

- Swanson, Stevenson (March 7, 2003). "9/11 haunts hijacker's sponsors; German couple talks of living with pilot Atta". Chicago Tribune.

- McDermott, Terry (January 27, 2002). "A Perfect Soldier; Mohamed Atta, whose hard gaze has stared from a billion television screens and newspaper pages, has become, for many, the face of evil incarnate". Los Angeles Times.

- McDermott (2005), pp. 22–23

- McDermott (2005), p. 25

- McDermott (2005), p. 24

- "Interview with Professor Dittmar Machule". ABC (Australia). October 18, 2001. Archived from the original on June 18, 2008. Retrieved August 1, 2008.

- "A Mission to Die For – Europe Map". ABC (Australia). October 18, 2001. Archived from the original on September 30, 2008. Retrieved August 1, 2008.

- McDermott (2005), p. 29-31

- Corbin (2003), p. 122

- McDermott (2005), p. 47

- Finn, Peter (September 22, 2001). "A Fanatic's Quiet Path to Terror; Rage Was Born in Egypt, Nurtured in Germany, Inflicted on U.S.". The Washington Post.

- "The Mastermind". CBS News. March 5, 2003. Archived from the original on September 30, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- Lappin, Elena (August 29, 2002). "Portrait: Atta in Hamburg". Prospect. Archived from the original on September 30, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- Corbin (2003), p. 123

- Buncombe, Andrew (October 12, 2001). "Childhood clues to what makes a killer". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on January 19, 2010. Retrieved September 8, 2010.

- "Four Corners – Volker Hauth interview". ABC (Australia). October 18, 2001. Archived from the original on June 18, 2008. Retrieved August 1, 2008.

- "Four Corners – Ralph Bodenstein interview". ABC (Australia). October 18, 2001. Archived from the original on June 17, 2008. Retrieved August 1, 2008.

- Loeterman, Ben; Hedrick Smith (January 17, 2002). "Inside the Terror Network". Frontline. PBS. Archived from the original on February 24, 2011. Retrieved September 8, 2010.

- Wright, Lawrence (2006). "Chapter 18 ("Boom")". The Looming Tower. Alfred P. Knopf. ISBN 9780375414862.

- Wright 2006.

- Fouda and Fielding (2003), p. 82

- "Volker Hauth interview". Four Corners. Australian Broadcasting Company (ABC). October 18, 2001. Archived from the original on May 4, 2010. Retrieved September 8, 2010.

- McDermott (2005), p. 2-3

- McDermott (2005), p. 34-37

- Fouda and Fielding (2003), p. 77

- Finn, Peter and Charles Lane (October 6, 2001). "Will Gives a Window into Suspect's Mind" (PDF). The Washington Post and 9/11 Digital Archive. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 28, 2008.

- Sly, Liz (September 21, 2001). "In hindsight, more suspicion called for; Hamburg was early hotbed for plotters". Chicago Tribune.

- McDermott (2005), Chapter 5

- McDermott (2005), p. 57

- McDermott (2005), p. 58

- McDermott (2005), p. 63

- Bernstein, Richard Bernstein (September 10, 2002). "On Path to the U.S. Skies, Plot Leader Met bin Laden". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 1, 2009. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- McDermott (2005), p. 180

- "Atta 'trained in Afghanistan'". BBC. August 24, 2002. Archived from the original on August 12, 2011. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- Frantz, Douglas; Desmond Butler (August 24, 2002). "Germans Lay Out Early Qaeda Ties to 9/11 Hijackers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 17, 2014. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- Bernstein, Richard (September 10, 2002). "On Path to the U.S. Skies, Plot Leader Met bin Laden". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 17, 2014. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- Popkin, Jim (October 1, 2006). "Video showing Atta, bin Laden is unearthed". NBC News. Retrieved January 28, 2008.

- "Inside the Terror Network". Frontline. PBS. January 17, 2002. Archived from the original on September 30, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- "Zacarias Moussauoi v. the United States (trial testimony)". Cryptome / United States District Court – Eastern District of Virginia. March 7, 2006. Archived from the original on December 23, 2013. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- "9/11 and Terrorist Travel" (PDF). Staff Report. National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 16, 2012. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- 9/11 Commission (June 2004). "Chapter 7". 9/11 Commission Report. National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. Archived from the original on October 23, 2013. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- McDermott (2005), p. 194

- "Transcript of Johnelle Bryant Interview". ABC News. June 6, 2002. Archived from the original on January 31, 2011. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- "Transcript: Bryant Interview, Part 2". ABC News. June 6, 2002. Archived from the original on January 31, 2011. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- "Twin towers hijacker 'sought US loan'". BBC News. June 7, 2002. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- "Hijacker tried to get U.S. loan to buy plane". The Seattle Times. June 7, 2002. Archived from the original on October 4, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- Allison, Wes (October 2, 2001). "The terrorists next door". St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on September 30, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- Whittle, Patrick (September 10, 2006). "Landlord: Steve Kona". Herald Tribune (Sarasota, Florida). Archived from the original on September 30, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- "Terrorist amongst us". Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Retrieved January 25, 2009.

- Tobin, Thomas C. (September 1, 2002). "Florida: Terror's Launching Pad". The St. Petersburg Times. St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on September 5, 2002. Retrieved September 5, 2002.

- "Algerian accused in Britain of training hijackers". Las Vegas Review-Journal. November 29, 2001. Archived from the original on June 18, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- "Hijackers' True Name Usage" (PDF). U.S.D.C. Eastern District of Virginia. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 12, 2009. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- "Investigating Terror". CNN. October 20, 2001. Archived from the original on September 30, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- Irujo, José María (March 21, 2004). "Atta recibió en Tarragona joyas para que los miembros del 'comando' del 11-S se hiciesen pasar por ricos saudíes". El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- "Stipulation" (PDF). U.S.D.C. Eastern District of Virginia. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 13, 2009. Retrieved January 27, 2008.

- "War Without Borders – The Madrid Bombing". The Fifth Estate. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). December 1, 2004. Archived from the original on December 2, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- Fouda and Fielding (2003), p. 216

- Frantz, Douglas (May 1, 2002). "Search for Sept. 11 Suspect Focuses on a Visit to Spain". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 4, 2009. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- Sullivan, Laura (January 27, 2004). "Sept. 11 hijacker raised suspicions at border". Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- Los Angeles Times, Document links al Qaeda paymaster, 9/11 plotter Archived January 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, September 27, 2002

- "NewsMine.org – hijackers traced to huffman aviation.txt". Archived from the original on December 28, 2005.

- Ross, Brian (July 29, 2011). "While America Slept: The True Story of 9/11". ABC News. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- Babin, John William (2015). Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in Portland : the fireside poet of Maine. Levinsky, Allan M. Charleston, SC. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-1-62619-499-1. OCLC 926057150.

- Belluck, Pam (October 5, 2001). "A Mundane Itinerary on the Eve of Terror". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 17, 2014. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- Wood, Graeme (March 2015). "What ISIS Really Wants". The Atlantic. Atlantic Media. Archived from the original on February 26, 2015. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- "9/11 mystery: What was Atta doing on 9/10?". NBC News. September 7, 2006. Archived from the original on February 27, 2015. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- "Staff Report – "We Have Some Planes": The Four Flights – a Chronology" (PDF). National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 6, 2008. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- "The Aviation Security System and the 9/11 Attacks – Staff Statement No. 3" (PDF). 9/11 Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 28, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- "Ticket agent recalls anger in Atta's eyes". NBC News.

- Sullivan, Laura (January 28, 2004). "9/11 victim calmly describes hijack on haunting tape". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- LA Times Archives, Tracking the Flights Hijacked on 9/11, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2004-jun-18-na-introflight18-story.html, June 18, 2004

- Karkavy, Jerry (October 5, 2001). "FBI affidavit: Flight attendant made call to report hijacking". Cape Cod Times. GateHouse Media, LLC. Archived from the original on January 6, 2017. Retrieved October 25, 2010.

- Rapoport, David C. (2006). Terrorism: The fourth or religious wave. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-31654-5.

- Fouda, Yosri (October 1, 2006). "Chilling Message of the 9/11 Pilots". The Sunday Times. London. Archived from the original on July 6, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- "A Case of Mistaken Identity: Mohammad Atta Not Linked to Bus Bombing". Anti-Defamation League. Archived from the original on September 17, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- O'Sullivan, Arieh (November 8, 2001). "Internet rumors aside, WTC attacker not held by Israel". Jerusalem Post.

- Gugliotta, Guy and David S. Fallis (September 15, 2001). "2nd Witness Arrested; 25 Held for Questioning". The Washington Post. p. A29. Archived from the original on March 31, 2009. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- Edward Jay Epstein (November 22, 2005). "Atta in Prague". OpinionJournal. Archived from the original on September 30, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- Kenety, Brian (September 3, 2004). "A Tale of Two 'Attas': How spurious Czech intelligence muddied the 9/11 probe". Radio Praha. Archived from the original on February 3, 2009. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- Crewdson, John (August 29, 2004). "In Prague, a tale of 2 Attas; Mistaken identity muddied 9/11 probe". Chicago Tribune.

- Burke (2005), p. 17.

- Jehl, Douglas (August 9, 2005). "Four in 9/11 Plot Are Called Tied to Qaeda in '00". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 6, 2008. Retrieved September 29, 2008.

- Eggen, Dan (August 19, 2005). "Officer Says 2 Others Are Source of His Atta Claims". The Washington Post. p. A11. Archived from the original on July 24, 2008. Retrieved September 29, 2008.

- White, Josh (September 22, 2006). "Hijackers Were Not Identified Before 9/11, Investigation Says". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved September 29, 2008.

- "Office Inspector General's Report" (PDF). Department of Defense. September 18, 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 16, 2012. Retrieved September 29, 2008.

- Herridge, Catherine (October 4, 2010). "Exclusive: Witnesses in Defense Dept. Report Suggest Cover-Up of 9/11 Findings". Fox News. Archived from the original on May 16, 2015. Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- Shaffer, Anthony (2010). Operation Dark Heart. St Martin's Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-312-60369-4.

- MacFarquhar, Neil (September 19, 2001). "Father Denies 'Gentle Son' Could Hijack Any Jetliner". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- Connolly, Kate (September 2, 2002). "Father insists alleged leader of attack on WTC is still alive". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- Alan Zarembo. "He Never Even Had a Kite" Mohamed Atta's father talks about his son, the alleged hijacker Archived September 12, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- "والدة مصري دشن هجمات 11 سبتمبر تشعر أنه حي وسيظهر". العربية (in Arabic). September 11, 2021.

- Weaver, Carolyn. (October 6, 2004). “New video shows 9/11 hijackers Mohammed Atta, Ziad Jarrah at Al-Qaida meeting.” Archived September 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Voice of America News.

- Pape, Robert. (2005). Dying to Win: The Strategic Logic of Suicide Terrorism, New York: Random House, p. 220

- Lankford, Adam. (2013). The Myth of Martyrdom: What Really Drives Suicide Bombers, Rampage Shooters, and Other Self-Destructive Killers. ISBN 978-0-23-034213-2

- Bianchi, Dominic; Shin, Peter (November 13, 2011), Back to the Pilot, Family Guy, retrieved February 16, 2022

References

- Burke, Jason (2003). Al-Qaeda: The True Story of Radical Islam (2006 revised ed.). New York: IB Tauris. ISBN 978-1-85043-666-9.

- Corbin, Jane (2003). Al-Qaeda: In Search of the Terror Network that Threatens the World. Nation Books. ISBN 1-56025-523-4.

- Der Spiegel (2002). Inside 9-11: What Really Happened. Diane Pub Co. ISBN 0-312-98748-X.

- Fouda, Yosri and Nick Fielding (2004). Masterminds of Terror. Arcade Publishing. ISBN 1-55970-717-8.

- Four Corners, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, broadcast November 12, 2001

- McDermott, Terry (2005). Perfect Soldiers: The 9/11 Hijackers: Who They Were, Why They Did It. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-058469-6.

- The 9/11 Commission Report, (W.W. Norton & Company) ISBN 0-393-32671-3

- Ruth Stein (2010). For Love of the Father: A Psychoanalytic Study of Religious Terrorism. Stanford Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0804763059.

External links

- Interviews with those who interacted with Atta prior to 9/11 from Australian ABC TV's "A Mission To Die For" TV programme

- October 2001 interview with Dittmar Machule – Machule was Atta's thesis supervisor at the University of Hamburg-Harburg

- Atta's will, written in 1996

- Atta's Odyssey – October 2001 biography of Atta printed in Time Magazine

- The Last Days of Muhammed Atta – a short story printed in The New Yorker

- Documentary series from Court TV (now TruTV) "MUGSHOTS: Mohammed Atta - Soldier of Terror" episode (2002) at FilmRise