Partially ordered set

In mathematics, especially order theory, a partially ordered set (also poset) formalizes and generalizes the intuitive concept of an ordering, sequencing, or arrangement of the elements of a set. A poset consists of a set together with a binary relation indicating that, for certain pairs of elements in the set, one of the elements precedes the other in the ordering. The relation itself is called a "partial order."

| Transitive binary relations | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The word partial in the names "partial order" and "partially ordered set" is used as an indication that not every pair of elements needs to be comparable. That is, there may be pairs of elements for which neither element precedes the other in the poset. Partial orders thus generalize total orders, in which every pair is comparable.

Informal definition

A partial order defines a notion of comparison. Two elements x and y may stand in any of four mutually exclusive relationships to each other: either x < y, or x = y, or x > y, or x and y are incomparable.[1][2]

A set with a partial order is called a partially ordered set (also called a poset). The term ordered set is sometimes also used, as long as it is clear from the context that no other kind of order is meant. In particular, totally ordered sets can also be referred to as "ordered sets", especially in areas where these structures are more common than posets.

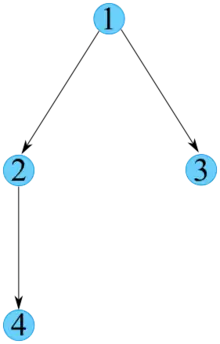

A poset can be visualized through its Hasse diagram, which depicts the ordering relation.[3]

Partial order relation

A partial order relation is a homogeneous relation that is transitive and antisymmetric.[4] There are two common sub-definitions for a partial order relation, for reflexive and irreflexive partial order relations, also called "non-strict" and "strict" respectively. The two definitions can be put into a one-to-one correspondence, so for every strict partial order there is a unique corresponding non-strict partial order, and vice versa. The term partial order typically refers to a non-strict partial order relation.

Non-strict partial order

A reflexive, weak,[4] or non-strict partial order[5] is a homogeneous relation ≤ on a set that is reflexive, antisymmetric, and transitive. That is, for all it must satisfy:

- Reflexivity: , i.e. every element is related to itself.

- Antisymmetry: if and then , i.e. no two distinct elements precede each other.

- Transitivity: if and then .

A non-strict partial order is also known as an antisymmetric preorder.

Strict partial order

An irreflexive, strong,[4] or strict partial order is a homogeneous relation < on a set that is irreflexive, asymmetric, and transitive; that is, it satisfies the following conditions for all

- Irreflexivity: not , i.e. no element is related to itself (also called anti-reflexive).

- Asymmetry: if then not .

- Transitivity: if and then .

Irreflexivity and transitivity together imply asymmetry. Also, asymmetry implies irreflexivity. In other words, a transitive relation is asymmetric if and only if it is irreflexive.[6] So the definition is the same if it omits either irreflexivity or asymmetry (but not both).

A strict partial order is also known as a strict preorder.

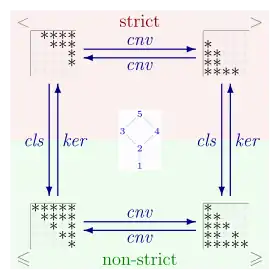

Correspondence of strict and non-strict partial order relations

Strict and non-strict partial orders on a set are closely related. A non-strict partial order may be converted to a strict partial order by removing all relationships of the form that is, the strict partial order is the set where is the identity relation on and denotes set subtraction. Conversely, a strict partial order < on may be converted to a non-strict partial order by adjoining all relationships of that form; that is, is a non-strict partial order. Thus, if is a non-strict partial order, then the corresponding strict partial order < is the irreflexive kernel given by

Conversely, if < is a strict partial order, then the corresponding non-strict partial order is the reflexive closure given by:

Dual orders

The dual (or opposite) of a partial order relation is defined by letting be the converse relation of , i.e. if and only if . The dual of a non-strict partial order is a non-strict partial order,[7] and the dual of a strict partial order is a strict partial order. The dual of a dual of a relation is the original relation.

Notation

We can consider a poset as a 3-tuple ,[8] where is a non-strict partial order relation on , is the associated strict partial order relation on (the irreflexive kernel of ), is the dual of , and is the dual of .

Any one of the four partial order relations on a given set uniquely determines the other three. Hence, as a matter of notation, one may write or , and assume that the other relations are defined appropriately. Defining via a non-strict partial order is most common. Some authors use different symbols than such as [9] or [10] to distinguish partial orders from total orders.

When referring to partial orders, should not be taken as the complement of . The relation is the converse of the irreflexive kernel of , which is always a subset of the complement of , but is equal to the complement of if, and only if, is a total order.[lower-alpha 1]

Examples

Standard examples of posets arising in mathematics include:

- The real numbers, or in general any totally ordered set, ordered by the standard less-than-or-equal relation ≤, is a non-strict partial order.

- On the real numbers , the usual less than relation < is a strict partial order. The same is also true of the usual greater than relation > on .

- By definition, every strict weak order is a strict partial order.

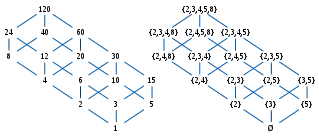

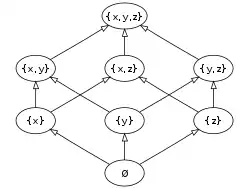

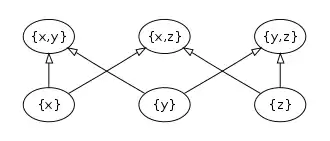

- The set of subsets of a given set (its power set) ordered by inclusion (see Fig.1). Similarly, the set of sequences ordered by subsequence, and the set of strings ordered by substring.

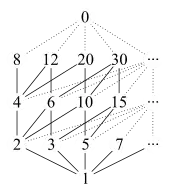

- The set of natural numbers equipped with the relation of divisibility. (see Fig.3 and Fig.6)

- The vertex set of a directed acyclic graph ordered by reachability.

- The set of subspaces of a vector space ordered by inclusion.

- For a partially ordered set P, the sequence space containing all sequences of elements from P, where sequence a precedes sequence b if every item in a precedes the corresponding item in b. Formally, if and only if for all ; that is, a componentwise order.

- For a set X and a partially ordered set P, the function space containing all functions from X to P, where f ≤ g if and only if f(x) ≤ g(x) for all

- A fence, a partially ordered set defined by an alternating sequence of order relations a < b > c < d ...

- The set of events in special relativity and, in most cases,[lower-alpha 2] general relativity, where for two events X and Y, X ≤ Y if and only if Y is in the future light cone of X. An event Y can only be causally affected by X if X ≤ Y.

One familiar example of a partially ordered set is a collection of people ordered by genealogical descendancy. Some pairs of people bear the descendant-ancestor relationship, but other pairs of people are incomparable, with neither being a descendant of the other.

Orders on the Cartesian product of partially ordered sets

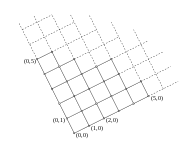

In order of increasing strength, i.e., decreasing sets of pairs, three of the possible partial orders on the Cartesian product of two partially ordered sets are (see Fig.4):

- the lexicographical order: (a, b) ≤ (c, d) if a < c or (a = c and b ≤ d);

- the product order: (a, b) ≤ (c, d) if a ≤ c and b ≤ d;

- the reflexive closure of the direct product of the corresponding strict orders: (a, b) ≤ (c, d) if (a < c and b < d) or (a = c and b = d).

All three can similarly be defined for the Cartesian product of more than two sets.

Applied to ordered vector spaces over the same field, the result is in each case also an ordered vector space.

See also orders on the Cartesian product of totally ordered sets.

Sums of partially ordered sets

Another way to combine two (disjoint) posets is the ordinal sum[11] (or linear sum),[12] Z = X ⊕ Y, defined on the union of the underlying sets X and Y by the order a ≤Z b if and only if:

- a, b ∈ X with a ≤X b, or

- a, b ∈ Y with a ≤Y b, or

- a ∈ X and b ∈ Y.

If two posets are well-ordered, then so is their ordinal sum.[13]

Series-parallel partial orders are formed from the ordinal sum operation (in this context called series composition) and another operation called parallel composition. Parallel composition is the disjoint union of two partially ordered sets, with no order relation between elements of one set and elements of the other set.

Derived notions

The examples use the poset consisting of the set of all subsets of a three-element set ordered by set inclusion (see Fig.1).

- a is related to b when a ≤ b. This does not imply that b is also related to a, because the relation need not be symmetric. For example, is related to but not the reverse.

- a and b are comparable if a ≤ b or b ≤ a. Otherwise they are incomparable. For example, and are comparable, while and are not.

- A total order or linear order is a partial order under which every pair of elements is comparable, i.e. trichotomy holds. For example, the natural numbers with their standard order.

- A chain is a subset of a poset that is a totally ordered set. For example, is a chain.

- An antichain is a subset of a poset in which no two distinct elements are comparable. For example, the set of singletons

- An element a is said to be strictly less than an element b, if a ≤ b and For example, is strictly less than

- An element a is said to be covered by another element b, written a ⋖ b (or a <: b), if a is strictly less than b and no third element c fits between them; formally: if both a ≤ b and are true, and a ≤ c ≤ b is false for each c with Using the strict order <, the relation a ⋖ b can be equivalently rephrased as "a < b but not a < c < b for any c". For example, is covered by but is not covered by

Extrema

There are several notions of "greatest" and "least" element in a poset notably:

- Greatest element and least element: An element is a greatest element if for every element An element is a least element if for every element A poset can only have one greatest or least element. In our running example, the set is the greatest element, and is the least.

- Maximal elements and minimal elements: An element is a maximal element if there is no element such that Similarly, an element is a minimal element if there is no element such that If a poset has a greatest element, it must be the unique maximal element, but otherwise there can be more than one maximal element, and similarly for least elements and minimal elements. In our running example, and are the maximal and minimal elements. Removing these, there are 3 maximal elements and 3 minimal elements (see Fig.5).

- Upper and lower bounds: For a subset A of P, an element x in P is an upper bound of A if a ≤ x, for each element a in A. In particular, x need not be in A to be an upper bound of A. Similarly, an element x in P is a lower bound of A if a ≥ x, for each element a in A. A greatest element of P is an upper bound of P itself, and a least element is a lower bound of P. In our example, the set is an upper bound for the collection of elements

As another example, consider the positive integers, ordered by divisibility: 1 is a least element, as it divides all other elements; on the other hand this poset does not have a greatest element (although if one would include 0 in the poset, which is a multiple of any integer, that would be a greatest element; see Fig.6). This partially ordered set does not even have any maximal elements, since any g divides for instance 2g, which is distinct from it, so g is not maximal. If the number 1 is excluded, while keeping divisibility as ordering on the elements greater than 1, then the resulting poset does not have a least element, but any prime number is a minimal element for it. In this poset, 60 is an upper bound (though not a least upper bound) of the subset which does not have any lower bound (since 1 is not in the poset); on the other hand 2 is a lower bound of the subset of powers of 2, which does not have any upper bound.

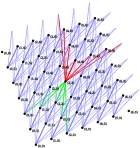

Mappings between partially ordered sets

Given two partially ordered sets (S, ≤) and (T, ≼),[lower-alpha 3] a function is called order-preserving, or monotone, or isotone, if for all implies f(x) ≼ f(y). If (U, ≲) is also a partially ordered set, and both and are order-preserving, their composition is order-preserving, too. A function is called order-reflecting if for all f(x) ≼ f(y) implies If is both order-preserving and order-reflecting, then it is called an order-embedding of (S, ≤) into (T, ≼). In the latter case, is necessarily injective, since implies and in turn according to the antisymmetry of If an order-embedding between two posets S and T exists, one says that S can be embedded into T. If an order-embedding is bijective, it is called an order isomorphism, and the partial orders (S, ≤) and (T, ≼) are said to be isomorphic. Isomorphic orders have structurally similar Hasse diagrams (see Fig.7a). It can be shown that if order-preserving maps and exist such that and yields the identity function on S and T, respectively, then S and T are order-isomorphic.[14]

For example, a mapping from the set of natural numbers (ordered by divisibility) to the power set of natural numbers (ordered by set inclusion) can be defined by taking each number to the set of its prime divisors. It is order-preserving: if divides then each prime divisor of is also a prime divisor of However, it is neither injective (since it maps both 12 and 6 to ) nor order-reflecting (since 12 does not divide 6). Taking instead each number to the set of its prime power divisors defines a map that is order-preserving, order-reflecting, and hence an order-embedding. It is not an order-isomorphism (since it, for instance, does not map any number to the set ), but it can be made one by restricting its codomain to Fig.7b shows a subset of and its isomorphic image under The construction of such an order-isomorphism into a power set can be generalized to a wide class of partial orders, called distributive lattices, see "Birkhoff's representation theorem".

Number of partial orders

Sequence A001035 in OEIS gives the number of partial orders on a set of n labeled elements:

| Elements | Any | Transitive | Reflexive | Symmetric | Preorder | Partial order | Total preorder | Total order | Equivalence relation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 16 | 13 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 512 | 171 | 64 | 64 | 29 | 19 | 13 | 6 | 5 |

| 4 | 65,536 | 3,994 | 4,096 | 1,024 | 355 | 219 | 75 | 24 | 15 |

| n | 2n2 | 2n2−n | 2n(n+1)/2 | n! | |||||

| OEIS | A002416 | A006905 | A053763 | A006125 | A000798 | A001035 | A000670 | A000142 | A000110 |

Note that S(n, k) refers to Stirling numbers of the second kind.

The number of strict partial orders is the same as that of partial orders.

If the count is made only up to isomorphism, the sequence 1, 1, 2, 5, 16, 63, 318, ... (sequence A000112 in the OEIS) is obtained.

Linear extension

A partial order on a set is an extension of another partial order on provided that for all elements whenever it is also the case that A linear extension is an extension that is also a linear (that is, total) order. As a classic example, the lexicographic order of totally ordered sets is a linear extension of their product order. Every partial order can be extended to a total order (order-extension principle).[15]

In computer science, algorithms for finding linear extensions of partial orders (represented as the reachability orders of directed acyclic graphs) are called topological sorting.

Directed acyclic graphs

Strict partial orders correspond directly to directed acyclic graphs (DAGs). If a graph is constructed by taking each element of to be a node and each element of to be an edge, then every strict partial order is a DAG, and the transitive closure of a DAG is both a strict partial order and also a DAG itself. In contrast a non-strict partial order would have self loops at every node and therefore not be a DAG.

In category theory

Every poset (and every preordered set) may be considered as a category where, for objects and there is at most one morphism from to More explicitly, let hom(x, y) = {(x, y)} if x ≤ y (and otherwise the empty set) and Such categories are sometimes called posetal.

Posets are equivalent to one another if and only if they are isomorphic. In a poset, the smallest element, if it exists, is an initial object, and the largest element, if it exists, is a terminal object. Also, every preordered set is equivalent to a poset. Finally, every subcategory of a poset is isomorphism-closed.

Partial orders in topological spaces

If is a partially ordered set that has also been given the structure of a topological space, then it is customary to assume that is a closed subset of the topological product space Under this assumption partial order relations are well behaved at limits in the sense that if and and for all then [16]

Intervals

An interval in a poset P is a subset I of P with the property that, for any x and y in I and any z in P, if x ≤ z ≤ y, then z is also in I. (This definition generalizes the interval definition for real numbers.)

For a ≤ b, the closed interval [a, b] is the set of elements x satisfying a ≤ x ≤ b (that is, a ≤ x and x ≤ b). It contains at least the elements a and b.

Using the corresponding strict relation "<", the open interval (a, b) is the set of elements x satisfying a < x < b (i.e. a < x and x < b). An open interval may be empty even if a < b. For example, the open interval (0, 1) on the integers is empty since there are no integers I such that 0 < I < 1.

The half-open intervals [a, b) and (a, b] are defined similarly.

Sometimes the definitions are extended to allow a > b, in which case the interval is empty.

An interval I is bounded if there exist elements such that I ⊆ [a, b]. Every interval that can be represented in interval notation is obviously bounded, but the converse is not true. For example, let P = (0, 1) ∪ (1, 2) ∪ (2, 3) as a subposet of the real numbers. The subset (1, 2) is a bounded interval, but it has no infimum or supremum in P, so it cannot be written in interval notation using elements of P.

A poset is called locally finite if every bounded interval is finite. For example, the integers are locally finite under their natural ordering. The lexicographical order on the cartesian product is not locally finite, since (1, 2) ≤ (1, 3) ≤ (1, 4) ≤ (1, 5) ≤ ... ≤ (2, 1). Using the interval notation, the property "a is covered by b" can be rephrased equivalently as

This concept of an interval in a partial order should not be confused with the particular class of partial orders known as the interval orders.

See also

- Antimatroid, a formalization of orderings on a set that allows more general families of orderings than posets

- Causal set, a poset-based approach to quantum gravity

- Comparability graph – Graph linking pairs of comparable elements in a partial order

- Complete partial order

- Directed set – Mathematical ordering with upper bounds

- Graded poset

- Incidence algebra

- Lattice – Set whose pairs have minima and maxima

- Locally finite poset

- Möbius function on posets

- Nested Set Collection

- Order polytope

- Ordered field – Algebraic object with an ordered structure

- Ordered group

- Ordered vector space – Vector space with a partial order

- Poset topology, a kind of topological space that can be defined from any poset

- Scott continuity – continuity of a function between two partial orders.

- Semilattice – Partial order with joins

- Semiorder – Numerical ordering with a margin of error

- Stochastic dominance

- Strict weak ordering – strict partial order "<" in which the relation "neither a < b nor b < a" is transitive.

- Total order – Order whose elements are all comparable

- Tree – Data structure of set inclusion

- Zorn's lemma – Mathematical proposition equivalent to the axiom of choice

Notes

- A proof can be found here.

- See General relativity#Time travel.

- The partial orders and ≼ can be different, but need not.

Citations

- "Finite posets". Sage 9.2.beta2 Reference Manual: Combinatorics. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

compare_elements(x, y): Compare x and y in the poset. If x<y, return -1. If x=y, return 0. If x>y, return 1. If x and y are not comparable, return None.

- Chen, Peter; Ding, Guoli; Seiden, Steve. "On Poset Merging" (PDF): 2. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

A comparison between two elements s, t in S returns one of three distinct values, namely s≤t, s>t or s|t.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Merrifield, Richard E.; Simmons, Howard E. (1989). Topological Methods in Chemistry. New York: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 28. ISBN 0-471-83817-9. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

A partially ordered set is conveniently represented by a Hasse diagram...

- Wallis, W. D. (14 March 2013). A Beginner's Guide to Discrete Mathematics. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-4757-3826-1.

- Simovici, Dan A. & Djeraba, Chabane (2008). "Partially Ordered Sets". Mathematical Tools for Data Mining: Set Theory, Partial Orders, Combinatorics. Springer. ISBN 9781848002012.

- Flaška, V.; Ježek, J.; Kepka, T.; Kortelainen, J. (2007). "Transitive Closures of Binary Relations I". Acta Universitatis Carolinae. Mathematica et Physica. Prague: School of Mathematics - Physics Charles University. 48 (1): 55–69. Lemma 1.1 (iv). This source refers to asymmetric relations as "strictly antisymmetric".

- Davey & Priestley (2002), pp. 14-15.

- Avigad, Jeremy; Lewis, Robert Y.; van Doorn, Floris (29 March 2021). "13.2. More on Orderings". Logic and Proof (Release 3.18.4 ed.). Retrieved 24 July 2021.

So we can think of every partial order as really being a pair, consisting of a weak partial order and an associated strict one.

- Rounds, William C. (7 March 2002). "Lectures slides" (PDF). EECS 203: DISCRETE MATHEMATICS. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- Kwong, Harris (25 April 2018). "7.4: Partial and Total Ordering". A Spiral Workbook for Discrete Mathematics. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- Neggers, J.; Kim, Hee Sik (1998), "4.2 Product Order and Lexicographic Order", Basic Posets, World Scientific, pp. 62–63, ISBN 9789810235895

- Davey & Priestley (2002), pp. 17–18.

- P. R. Halmos (1974). Naive Set Theory. Springer. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-4757-1645-0.

- Davey & Priestley (2002), pp. 23–24.

- Jech, Thomas (2008) [1973]. The Axiom of Choice. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-46624-8.

- Ward, L. E. Jr (1954). "Partially Ordered Topological Spaces". Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society. 5 (1): 144–161. doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-1954-0063016-5. hdl:10338.dmlcz/101379.

References

- Davey, B. A.; Priestley, H. A. (2002). Introduction to Lattices and Order (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78451-1.

- Deshpande, Jayant V. (1968). "On Continuity of a Partial Order". Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society. 19 (2): 383–386. doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-1968-0236071-7.

- Schmidt, Gunther (2010). Relational Mathematics. Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications. Vol. 132. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76268-7.

- Bernd Schröder (11 May 2016). Ordered Sets: An Introduction with Connections from Combinatorics to Topology. Birkhäuser. ISBN 978-3-319-29788-0.

- Stanley, Richard P. (1997). Enumerative Combinatorics 1. Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics. Vol. 49. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-66351-2.