Kingdom of Israel (Samaria)

The Kingdom of Israel (Hebrew: מַמְלֶכֶת יִשְׂרָאֵל, Modern: Mamleḵet Yīsra'ēl, Tiberian: Mamleḵeṯ Yīśrāʼēl), or the Kingdom of Samaria, was an Israelite kingdom of the Southern Levant during the Iron Age. The kingdom controlled the regions of Samaria, Galilee and parts of the Transjordan. Its capital, for the most part, was Samaria. The other Israelite polity, the Kingdom of Judah, lay to the south.

Kingdom of Israel 𐤉𐤔𐤓𐤀𐤋[1] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 930 BCE–c. 720 BCE | |||||||||

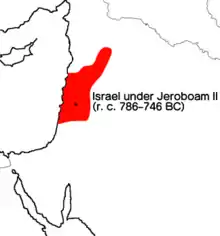

Map of Israel and Judah in the 9th century BCE, with Israel in blue and Judah in yellow. | |||||||||

| Status | Kingdom | ||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||

| Common languages | Biblical Hebrew, Israelian Hebrew | ||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

• c. 931–910 BCE | Jeroboam I (first) | ||||||||

• 732–c. 720 BCE | Hoshea (last) | ||||||||

| Historical era | Iron Age | ||||||||

• Jeroboam's Revolt | c. 930 BCE | ||||||||

• Assyrian exile | c. 720 BCE | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | IL | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

The Hebrew Bible depicts the Kingdom of Israel as one of two successor states to the former United Kingdom of Israel ruled by King David and his son Solomon, the other being the Kingdom of Judah. However, historicity of the United Monarchy as described in the Bible is debated.[Notes 1] It can be said with certainty that the northern regions underwent a period of re-urbanization during the 10th century BCE, paving the way to the establishment of a kingdom ruled by the Omride dynasty in the 9th century BCE, and that the political center of this kingdom shifted from Shechem to Samaria, where a lavish palace was built.[2]

The Kingdom of Israel was destroyed by the Neo-Assyrian Empire around 720 BCE.[3] The records of Sargon II of Assyria indicate that he deported 27,290 inhabitants of the former kingdom to Mesopotamia.[4] This deportation became the basis for the Jewish idea of the Ten Lost Tribes. Many Israelites migrated to the southern kingdom of Judah.[5] Foreign groups were settled by the Assyrians in the territories of the fallen kingdom.[6]

After the destruction of Israel, the Samaritans emerged as an ethnic and religious community in the region of Samaria, whose traditions state that they descend from the Israelites. With their temple on Mount Gerizim, they continued to thrive for centuries.[6] Today, most scholars believe the Samaritans were a blend of Israelites with other nationalities whom the Assyrians had resettled in the area.[7]

History

The existence of an Israelite state in the north is documented in 9th century inscriptions.[8] The earliest mention is from the Kurkh stela of c.853 BCE, when Shalmaneser III mentions "Ahab the Israelite", plus the denominative for "land", and his ten thousand troops.[9] This kingdom will have included parts of the lowlands (the Shephelah), the Jezreel plain, lower Galilee and parts of the Transjordan.[9] Ahab's forces were part of an anti-Assyrian coalition, implying that the kingdom was ruled by an urban elite, possessed a royal and state cult with large urban temples, and had scribes, mercenaries, and an administrative apparatus.[9] In all this it was similar to other recently-founded kingdoms of the time, such as Ammon and Moab.[9]

In later Assyrian inscriptions the kingdom becomes the "House of Omri".[9] Shalmanesser III's "Black Obelisk" mentions Jehu son of Omri, and Adad-Nirari III, who mounted an expedition into the Levant in 803, mentions the Hatti-land and Amurru-land, the cities of Tyre and Sidon, Philistia, Edom, Aram, and the mat (land) of Hu-um-ri, or Omri.[9] Another inscription from the same king introduces a third way of talking about the kingdom, as Samaria, in the phrase "Joash of Samaria".[10] The use of Omri's name to refer to the kingdom still survived, and was used by Sargon II in the phrase "the whole house of Omri" in describing his conquest of the city of Samaria in 722 BCE.[11] It is significant that the Assyrians never mention the kingdom of Judah until the end of the 8th century, when it was an Assyrian vassal: possibly they never had contact with it, or possibly they regarded it as a vassal of Israel/Samaria or Aram, or possibly the southern kingdom did not exist during this period.[12]

Today, among archaeologists, Samaria is one of the most universally accepted archaeological sites from the biblical period.[13] At around 850 BCE, the Mesha Stele, written in Old Hebrew alphabet, records a victory of King Mesha of Moab against king Omri of Israel and his son Ahab.[14]

Archaeological finds, ancient Near Eastern texts, and the biblical record testify that in the time of the Omride dynasty, the Kingdom of Israel ruled in the mountainous Galilee, at Hazor in the upper Jordan Valley, in large parts of Transjordan between the Arnon and the Yarmouk Rivers, and in the coastal plain of the Sharon.[15]

In the Bible

The main source for the history of the Kingdom of Israel is the Hebrew Bible, written by authors in Jerusalem, the capital of the Kingdom of Judah. As such, it is inspired by ideological and theological viewpoints that influence the narrative.[15] Later anachronisms, legends and literary forms also affect the story. Some of the events are believed to have been recorded long after the destruction of the kingdom. Biblical archaeology has both confirmed and challenged the biblical account.[15] According to the Bible, David and his son Solomon ruled over a united monarchy, but on the death of Solomon, after a short interval during which the kingdom was ruled by Solomon's son Rehoboam, the northern tribes revolted and established their own kingdom under Jeroboam, who was not of the Davidic line. This northern kingdom became the Kingdom of Israel. The first mention of the name "Israel" is from an Egyptian inscription, the Merneptah Stele, dating from the Late Bronze Age (c. 1208 BCE); this gives little solid information, but does at least indicate that the name of the later kingdom was borrowed rather than originating with the kingdom itself.[16]

Relations between the kingdoms of Israel and Judah

According to the Bible, for the first sixty years, the kings of Judah tried to re-establish their authority over the northern kingdom, and there was perpetual war between them. For the following eighty years, there was no open war between them, and, for the most part, they were in friendly alliance, co-operating against their common enemies, especially against Damascus.

The conflict between Israel and Judah was resolved when Jehoshaphat, King of Judah, allied himself with the house of Ahab through marriage. Later, Jehosophat's son and successor, Jehoram of Judah, married Ahab's daughter Athaliah, cementing the alliance. However, the sons of Ahab were slaughtered by Jehu following his coup d'état around 840 BCE.

Destruction of the Kingdom, 732–720 BC

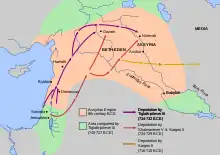

In c. 732 BCE, Pekah of Israel, while allied with Rezin, king of Aram, threatened Jerusalem. Ahaz, king of Judah, appealed to Tiglath-Pileser III, the king of Assyria, for help. After Ahaz paid tribute to Tiglath-Pileser[20] Tiglath-Pileser sacked Damascus and Israel, annexing Aram[21] and territory of the tribes of Reuben, Gad and Manasseh in Gilead including the desert outposts of Jetur, Naphish and Nodab. People from these tribes including the Reubenite leader, were taken captive and resettled in the region of the Khabur River system, in Halah, Habor, Hara and Gozan (1 Chronicles 5:26). Tiglath-Pilesar also captured the territory of Naphtali and the city of Janoah in Ephraim and an Assyrian governor was placed over the region of Naphtali. According to 2 Kings 16:9 and 2 Kings 15:29, the population of Aram and the annexed part of Israel was deported to Assyria.[22]

The remainder of the northern kingdom of Israel continued to exist within the reduced territory as an independent kingdom until around 720 BCE, when it was again invaded by Assyria and the rest of the population deported. During the three-year siege of Samaria in the territory of Ephraim by the Assyrians, Shalmaneser V died and was succeeded by Sargon II, who himself records the capture of that city thus: "Samaria I looked at, I captured; 27,280 men who dwelt in it I carried away" into Assyria. Thus, around 720 BCE, after two centuries, the kingdom of the ten tribes came to an end. Some of the Israelite captives were resettled in the Khabur region, and the rest in the land of the Medes, thus establishing Hebrew communities in Ecbatana and Rages. The Book of Tobit additionally records that Sargon had taken other captives from the northern kingdom to the Assyrian capital of Nineveh, in particular Tobit from the town of Thisbe in Naphtali.

The Hebrew Bible relates that the population of the Kingdom of Israel was exiled, becoming known as the Ten Lost Tribes. To the south, the Tribe of Judah, the Tribe of Simeon (that was "absorbed" into Judah), the Tribe of Benjamin and the people of the Tribe of Levi, who lived among them of the original Israelite nation, remained in the southern Kingdom of Judah. The Kingdom of Judah continued to exist as an independent state until 586 BCE, when it was conquered by the Neo-Babylonian Empire.

Samaritan version

Samaritan tradition states that much of the population of the Northern Kingdom of Israel remained in place after the Exile, including the Tribes of Naphtali, Menasseh, Benjamin and Levi - being the progenitors of the Samaritans. In their book The Bible Unearthed, authors Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman estimate that only a fifth of the population (about 40,000) were actually resettled out of the area during the two deportation periods under Tiglath-Pileser III and Sargon II.[23]: 221 Many of the Northern Tribes also fled south to Jerusalem, which appears to have expanded in size five-fold during this period, requiring a new wall to be built, and a new source of water Siloam to be provided by King Hezekiah.[5]

Medieval Rabbinic fable

In medieval Rabbinic fable, the concept of the ten tribes who were taken away from the House of David (who continued the rule of the southern kingdom of Judah), becomes confounded with accounts of the Assyrian deportations leading to the myth of the "Ten Lost Tribes".

Recorded history

No known non-Biblical record exists of the Assyrians having exiled people from Dan, Asher, Issachar, Zebulun or western Manasseh. Descriptions of the deportation of people from Reuben, Gad, Manasseh in Gilead, Ephraim and Naphtali indicate that only a portion of these tribes were deported and the places to which they were deported are known locations given in the accounts. The deported communities are mentioned as still existing at the time of the composition of the Books of Kings and Chronicles and did not disappear by assimilation. 2 Chronicles 30:1-18 explicitly mentions northern Israelites who had been spared by the Assyrians, in particular people of Ephraim, Manasseh, Asher, Issachar and Zebulun, and how members of the latter three returned to worship at the Temple in Jerusalem during the reign of Hezekiah.[24]

Religion

The religious climate of the Kingdom of Israel appears to have followed two major trends. The first, that of worship of Yahweh, and the second that of worship of Baal as detailed in the Hebrew Bible (1 Kings 16:31) and in the Baal cycle discovered at Ugarit.[25] This religion is sometimes referred to by modern scholars as Yahwism.[26]

According to the Hebrew Bible (1 Kings 12:29), Jeroboam built two places of worship, one at Bethel and one at far northern Dan, as alternatives to the Temple in Jerusalem.[27] He did not want the people of his kingdom to have religious ties to Jerusalem, the capital city of the rival Kingdom of Judah. He erected golden bulls at the entrance to the temples to represent the national god.[28] The Hebrew Bible, written from the perspective of scribes in Jerusalem, referred to these acts as the way of Jeroboam or the errors of Jeroboam (1 Kings 12:26–29).[28]

The Bible states that Ahab allowed the cult worship of Baal to become an acceptable religion of the kingdom. His wife Jezebel was the daughter of the Phoenician king of Tyre and a devotee to Baal worship (1 Kings 16:31).

Royal houses

According to the Bible, the Northern Kingdom had 19 kings across 9 different dynasties throughout its 208 years of existence.

| History of Israel |

|---|

|

|

|

List of proposed Assyrian references to Kingdom of Israel (Samaria)

The table below lists all the historical references to the Kingdom of Israel (Samaria) in Assyrian records.[29] King Omri's name takes the Assyrian shape of "Humri", his kingdom or dynasty that of Bit Humri or alike - the "House of Humri/Omri".

| Assyrian King | Inscription | Year | Transliteration | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shalmaneser III | Kurkh Monoliths | 853 BCE | KUR sir-'i-la-a-a | "Israel" |

| Shalmaneser III | Black Obelisk, Calah Fragment, Kurba'il Stone, Ashur Stone | 841 BCE | mar Hu-um-ri-i | "of Omri" |

| Adad-nirari III | Tell al-Rimah Stela | 803 BCE | KUR Sa-me-ri-na-a-a | "land of Samaria" |

| Adad-nirari III | Nimrud Slab | 803 BCE | KUR <Bit>-Hu-um-ri-i | "the 'land of [the House of] Omri" |

| Tiglath-Pileser III | Layard 45b+ III R 9,1 | 740 BCE | [KUR sa-me-ri-i-na-a-a] | ["land of Samaria"] |

| Tiglath-Pileser III | Iran Stela | 739–738 BCE | KUR sa-m[e]-ri-i-na-a-[a] | "land of Samaria" |

| Tiglath-Pileser III | Layard 50a + 50b + 67a | 738–737 BCE | URU sa-me-ri-na-a-a | "city of Samaria" |

| Tiglath-Pileser III | Layard 66 | 732–731 BCE | URU Sa-me-ri-na | "city of Samaria" |

| Tiglath-Pileser III | III R 10,2 | 731 BCE | KUR E Hu-um-ri-a | "land of the House of Omri" |

| Tiglath-Pileser III | ND 4301 + 4305 | 730 BCE | KUR E Hu-um-ri-a | "land of the House of Omri" |

| Shalmaneser V | Babylonian Chronicle ABC1 | 725 BCE | URU Sa-ma/ba-ra-'-in | "city of Samaria" |

| Sargon II | Nimrud Prism, Great Summary Inscription | 720 BCE | URU Sa-me-ri-na | "city of Samaria" |

| Sargon II | Palace Door, Small Summary Inscription, Cylinder Inscription, Bull Inscription | 720 BCE | KUR Bit-Hu-um-ri-a | "land of Omri" |

See also

- Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy) (the unified kingdom before the split)

- Kingdom of Judah (the southern kingdom)

- Israel (the modern country)

- List of Jewish states and dynasties

References

Notes

- The debate is described in Amihai Mazar, "Archaeology and the Biblical Narrative: The Case of the United Monarchy" (see bibliography), p.29 fn.2: "For conservative approaches defining the United Monarchy as a state “from Dan to Beer Sheba” including “conquered kingdoms” (Ammon, Moab, Edom) and “spheres of influence” in Geshur and Hamath cf. e.g. Ahlström (1993), 455–542; Meyers (1998); Lemaire (1999); Masters (2001); Stager (2003); Rainey (2006), 159–168; Kitchen (1997); Millard (1997; 2008). For a total denial of the historicity of the United Monarchy cf. e.g. Davies (1992), 67–68; others suggested a ‘chiefdom’ comprising a small region around Jerusalem, cf. Knauf (1997), 81–85; Niemann (1997), 252–299 and Finkelstein (1999). For a ‘middle of the road’ approach suggesting a United Monarchy of larger territorial scope though smaller than the biblical description cf.e.g. Miller (1997); Halpern (2001), 229–262; Liverani (2005), 92–101. The latter recently suggested a state comprising the territories of Judah and Ephraim during the time of David, that was subsequently enlarged to include areas of northern Samaria and influence areas in the Galilee and Transjordan. Na’aman (1992; 1996) once accepted the basic biography of David as authentic and later rejected the United Monarchy as a state, cf. id. (2007), 401–402".

Citations

-

- Rollston, Chris A. (2010). Writing and Literacy in the World of Ancient Israel: Epigraphic Evidence from the Iron Age. Society of Biblical Literature. pp. 52–54. ISBN 978-1589831070.

- Compston, Herbert F. B. (1919). The Inscription on the Stele of Méšaʿ.

- Schipper 2020, p. unpaginated.

- Schipper, Bernd U. (25 May 2021). Chapter 3 Israel and Judah from 926/925 to the Conquest of Samaria in 722/720 BCE. Penn State University Press. doi:10.1515/9781646020294-007. ISBN 978-1-64602-029-4.

- Younger, K. Lawson (1998). "The Deportations of the Israelites". Journal of Biblical Literature. 117 (2): 201–227. doi:10.2307/3266980. ISSN 0021-9231.

- Finkelstein, Israel (28 June 2015). "Migration of Israelites into Judah after 720 BCE: An Answer and an Update". Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft. 127 (2): 188–206. doi:10.1515/zaw-2015-0011. ISSN 1613-0103.

- Israel, Finkelstein (2013). The forgotten kingdom : the archaeology and history of Northern Israel. Society of Biblical Literature. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-58983-910-6. OCLC 949151323.

- Shen, Peidong; Lavi, Tal; Kivisild, Toomas; Chou, Vivian; Sengun, Deniz; Gefel, Dov; Shpirer, Issac; Woolf, Eilon; Hillel, Jossi; Feldman, Marcus W.; Oefner, Peter J. (2004). "Reconstruction of patrilineages and matrilineages of Samaritans and other Israeli populations from Y-Chromosome and mitochondrial DNA sequence Variation". Human Mutation. 24 (3): 248–260. doi:10.1002/humu.20077. ISSN 1059-7794.

- Dever 2017, p. 338.

- Davies 2015, p. 72.

- Davies 2015, p. 72-73.

- Davies 2015, p. 73.

- Davies 2015, p. 3.

- See Yohanan Aharoni, et al. (1993) The Macmillan Bible Atlas, p. 94, Macmillan Publishing: New York; and Amihai Mazar (1992) The Archaeology of the Land of the Bible: 10,000 – 586 B.C.E, p. 404, New York: Doubleday, see pp. 406-410 for discussion of archaeological significance of Shomron (Samaria) under Omride Dynasty.

- 2 Kings 3

- Israel., Finkelstein. The forgotten kingdom : the archaeology and history of Northern Israel. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-58983-910-6. OCLC 949151323.

- Davies 2015, p. 71-72.

- Kuan, Jeffrey Kah-Jin (2016). Neo-Assyrian Historical Inscriptions and Syria-Palestine: Israelite/Judean-Tyrian-Damascene Political and Commercial Relations in the Ninth-Eighth Centuries BCE. Wipf and Stock Publishers. pp. 64–66. ISBN 978-1-4982-8143-0.

- Cohen, Ada; Kangas, Steven E. (2010). Assyrian Reliefs from the Palace of Ashurnasirpal II: A Cultural Biography. UPNE. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-58465-817-7.

- Delitzsch, Friedrich; McCormack, Joseph; Carruth, William Herbert; Robinson, Lydia Gillingham (1906). Babel and Bible;. Chicago, The Open court publishing company. p. 78.

- 2 Kings 16:7–9

- Lester L. Grabbe (2007). Ancient Israel: What Do We Know and How Do We Know It?. New York: T&T Clark. p. 134. ISBN 978-05-67-11012-1.

- 2 Kings 16:9 and 15:29

- Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2002) The Bible Unearthed : Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-684-86912-8

- 2 Chronicles 30:1–18

- Miller, Patrick D. (2000). The religion of ancient Israel. London: SPCK. ISBN 0-664-22145-9. OCLC 44174114.

- Miller, Patrick D. (2000). The religion of ancient Israel. London: SPCK. ISBN 0-664-22145-9. OCLC 44174114.

- Jonathan S. Greer (2015) "The Sanctuaries at Dan and Bethel"

- "Israelite Temple", Tel Dan Excavations

- Kelle, Brad (2002), "What's in a Name? Neo-Assyrian Designations for the Northern Kingdom and Their Implications for Israelite History and Biblical Interpretation", Journal of Biblical Literature, 121 (4): 639–666, doi:10.2307/3268575, JSTOR 3268575

Sources

- Davies, Philip (2015). The History of Ancient Israel. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Dever, William (2017). Beyond the Texts: An Archaeological Portrait of Ancient Israel and Judah. SBL Press.

- Mazar, Amihai (2010). "Archaeology and the Biblical Narrative: The Case of the United Monarchy". In Kratz, Reinhard G.; Spieckermann, Hermann (eds.). One God – One Cult – One Nation: Archaeological and Biblical Perspectives. Walter de Gruyter.

- Schipper, Berndt U. (2020). A Concise History of Ancient Israel. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0495391050.

External links

- About Israel - The Information Center About Israel

- Biblical History. The Jewish History Resource Center - Project of the Dinur Center for Research in Jewish History, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Complete Bible Genealogy A synchronized chart of the kings of Israel and Judah