Overseas Filipinos

An overseas Filipino (Filipino: Pilipino sa ibayong-dagat) is a person of full or partial Filipino origin—i.e., people who trace back their ancestry to the Philippines but living or residing outside the country. This term generally applies to both people of Filipino ancestry and citizens abroad. As of 2019, there were over 12 million Filipinos overseas.[2]

Mga Pilipino sa Ibayong-dagat | |

|---|---|

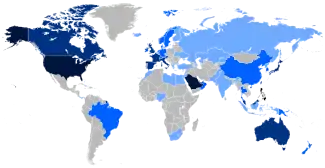

Map of the Filipino diaspora in the world | |

| Total population | |

| 11–12 million (2019)[1][2] figures below are for various years, per individual supporting sources cited. | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 4,037,564 (2018)[3] | |

| 780,100 (2021)[4] | |

| 938,490 (2015)[5] | |

| 919,819 (2013)[6] | |

| 825,000 (2020) (2017)[7][8] | |

| 408,836 (2021)[9] | |

| 276,000 (2018)[10] | |

| 245,000 (2009)[11] | |

| 240,000 (2017)[12] | |

| 203,243 (2013)[13] | |

| 150,000-200,000 (2020)[14][15] | |

| 200,000 (2018)[16] | |

| 200,000 (2017)[17] | |

| 186,869 (2016)[18] | |

| 165,783 (2014)[19] | |

| 29,578 (2020)[20] | |

Population

Since the liberalization of the United States immigration laws in 1965, the number of people in the United States having Filipino ancestry has grown substantially. In 2007, there were an estimated 12 million Filipinos living overseas.[21][22][23]

In 2013, the Commission on Filipinos Overseas (CFO) estimated that approximately 10.2 million people of Filipino descent lived or worked abroad.[13] This number constitutes about 11 percent of the total population of the Philippines.[24] It is one of the largest diaspora populations, spanning over 100 countries.[25]

The Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) tend to be young and gender-balanced. Based on a survey conducted in 2011, the demographics indicate how the 24-29 age group constitutes 24 percent of the total and is followed by the 30-34 age group (23 percent) working abroad.[26] Male OFWs account for 52 percent of the total OFW population. The slightly smaller percentage of the female overseas workers tend to be younger than their male counterparts.[26] Production workers and service workers account for more than 80 percent of the labor outflows by 2010 and this number is steadily increasing, along with the trend for professional workers, who are mainly nurses and engineers.[26] Filipino seamen, overseas Filipino workers in the maritime industry, make an oversize impact on the global economy, making up a fifth to a quarter of the merchant marine crews, who are responsible for the movement of the majority of goods in the global economy.[27][28]

The OFW population is consistently increasing through the years and this is partly attributed to the government's encouragement of the outflow of contractual workers as evidenced in policy pronouncements, media campaigns, and other initiatives.[29] For instance, it describes the OFWs as the heroes of the nation, encouraging citizens to take pride in these workers.

Economic impact

In 2012, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP), the central bank of the Philippines, expects official remittances coursed through banks and agents to grow 5% over 2011 to US$21 billion, but official remittances are only a fraction of all remittances.[30] In 2018, remittance had increased to $31 billion, which was nearly 10% of the GDP of the Philippines.[27] Remittances by unofficial, including illegal, channels are estimated by the Asian Bankers Association to be 30 to 40% higher than the official BSP figure.[30] In 2011, remittances were US$20.117 billion.[31] In 2012, approximately 80% of the remittances came from only 7 countries—United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, UAE, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, and Japan.[31]

In 2019, Overseas Filipinos sent back $32.2 billion to the Philippines.[32]

Issues

Employment conditions

Employment conditions abroad are relevant to the individual worker and their families as well as for the sending country and its economic growth and well-being. Poor working conditions for Filipinos hired abroad include long hours, low wages and few chances to visit family.[33][34][35] Evidence suggests that these women cope with the emotional stress of familial separation in one of two ways: first, in domestic care situations, they substitute their host-family's children for their own in the love and affection they give, and second, they actively considered the benefit their earnings would have on their children's future.[35] Women often face disadvantages in their employment conditions as they tend to work in the elder/child care and domestic.[36] These occupations are considered low skilled and require little education and training, thereby regularly facing poor working conditions.[33] Women facing just working conditions are more likely to provide their children with adequate nutrition, better education and sufficient health. There is a strong correlation between women's rights and the overall well-being of children. It is therefore a central question to promote women's rights in order to promote children's capabilities.[37][38]

According to a statement made in 2009 by John Leonard Monterona, the Middle East coordinator of Migrante, a Manila-based OFW organization, every year, an unknown number of Filipinos in Saudi Arabia were then "victims of sexual abuses, maltreatment, unpaid salaries, and other labor malpractices".[39]

Government policy

Philippine Labor Migration Policy has historically focused on removing barriers for migrant workers to increase accessibility for employment abroad. Working conditions among Filipinos employed abroad varies depending on whether the host country acknowledges and enforces International labor standards. The standards are set by the ILO, which is an UN agency that 185 of the 193 UN members are part of. Labor standards vary greatly depending on host country regulations and enforcement. One of the main reasons for the large differences in labor standards is due to the fact that ILO only can register complaints and not impose sanctions on governments.

Emigration policies tend to differ within countries depending on if the occupation is mainly dominated by men or women. Occupations dominated by men tend to be driven by economic incentives whereas emigration policies aimed at women traditionally tend to be value driven, adhering to traditional family roles that favors men's wage work. As women are regularly seen as symbols of national pride and dignity, governments tend to have more protective policies in sectors dominated by women. These policies risk to increase gender inequality in the Philippines and thereby this public policy work against women joining the workforce.[40] Female OFWs most often occupy domestic positions.[41] However, some researchers[34] argue that the cultural trends of female migrancy have the potential to destabilize the gender inequality of the Filipino culture. Evidence suggests that in intact, heterosexual families wherein the wife-mother works overseas, Filipino fathers have the potential to take on greater roles in care-giving to their children, though seldom few actually do.[42] Other researchers report that these situations lead to abuse, particularly of older daughters, who face increased pressure and responsibility in the mother's absence.[36] Likewise, the “reversal of breadwinning and caregiving roles between migrant wives and left-behind husbands” more often results in tension regarding family finances and the role each spouse should play in decision making.[33]

The Philippine government has recently opened up their public policy to promote women working abroad since the world's demand for domestic workers and healthcare workers has increased.[36] This has led to the government reporting a recent increase in women emigrating from the Philippines. A healthcare problem arises as migrating women from the Philippines and other developing countries often create a nursing shortage in the home country. Nurse to patient ratio is down to 1 nurse to between 40 and 60 patients, in the 1990s the ratio was 1 nurse to between 15 and 20 patients. It seems inevitable that the healthcare sector loses experienced nurses as the emigration is increasing. The Japan-Philippines Economic Partnership Agreement is seen as a failure by most since only 7% of applicants or 200 nurses a year has been accepted on average – mainly due to resistance by domestic stakeholders and failed program implementation. The result is a "lose-lose" outcome where Philippine workers fail to leverage their skills and a worldwide shortage persists. Despite the fact that Japan has an aging population and many Filipinos want to work in Japan, a solution has not yet been found. The Japanese Nursing Association supports "equal or better" working conditions and salaries for Filipino nurses. In contrast, Yagi propose more flexible wages to make Filipinos more attractive on the Japanese job market.[43][44] [45]

Results from a focus group in the Philippines shows that the positive impacts from migration of nurses is attributed to the individual migrant and his/her family, while the negative impacts are attributed to the Filipino healthcare system and society in general. In order to fill the nursing shortage in the Philippines, suggestions have been made by several NGOs that nursing-specializing Filipino workers overseas, locally known as "overseas Filipino workers" (OFWs), return to the country to train local nurses, for which program training would be required in order for the Philippines to make up for all its nurses migrating abroad.[45]

Host country policies

Wealthier households derive a larger share of their income from abroad. This might suggest that government policies in host countries favor capital-intensive activities. Even though work migration is mainly a low and middle class activity, the high-income households are able to derive a larger share of their income from abroad due to favorable investment policies. These favorable investment policies causes an increase in income inequalities and do not promote domestic investments that can lead to increased standard of living. This inequality threatens to halt the economic development as investments are needed in the Philippines and not abroad in order to increase growth and well-being. A correlation between successful contribution to the home country's economy and amounted total savings upon the migrants return has been found, therefore it is important to decrease income inequalities while attracting capital from abroad to the Philippines.[43][46]

Many host governments of OFWs have protective policies and barriers making it difficult to enter the job market. Japan has been known for rigorous testing of Filipinos in a way that make them look reluctant to hold up their part of the Japan-Philippines Economic Partnership Agreement and solely enjoy the benefit of affordable manufacturing in the Philippines, not accepting and educating OFWs.[44]

Return migration

Returning migrant workers are often argued to have a positive effect on the home economy since they are assumed to gain skills and return with a new perspective. Deskilling has caused many Filipino workers to return less skilled after being assigned simple tasks abroad, this behavior creates discouragement for foreign workers to climb the occupational ladder. Deskilling of labor is especially prevalent among women who often have few and low skill employment options, such as domestic work and child or elder care. Other occupations that recently has seen an increase in deskilling are doctors, teachers and assembly line workers.[43]

To underline what a common problem this deskilling is: Returning migrant workers are calling for returnee integration programs, which suggests that they do not feel prepared to be re-integrated in the domestic workforce.[40]

As the Philippines among other countries who train and export labor repeatedly has faced failures in protecting labor rights, the deskilling of labor has increased on a global scale. A strong worldwide demand for healthcare workers causes many Filipinos to emigrate without ever getting hired or become deskilling while possibly raising their salary. The result is a no-win situation for the sending and receiving country. The receiving countries lose as skilled workers are not fully utilizing their skills while the home country simultaneously experience a shortage of workers in emigrating prone sectors.[44]

Countries and territories with Filipino populations

.svg.png.webp) Australia: In the 2016 Census, there were 232,386 Filipino Australians.[48]

Australia: In the 2016 Census, there were 232,386 Filipino Australians.[48] Austria: As of 2018, the Filipino community in Austria numbered roughly 30,000.[49] See Filipinos in Austria.

Austria: As of 2018, the Filipino community in Austria numbered roughly 30,000.[49] See Filipinos in Austria. The Bahamas: As of 2010, there were 2,000 Filipinos in The Bahamas.

The Bahamas: As of 2010, there were 2,000 Filipinos in The Bahamas. Bahrain: As of 2020, there were 55,790 Filipinos in Bahrain.[50]

Bahrain: As of 2020, there were 55,790 Filipinos in Bahrain.[50].svg.png.webp) Belgium: As of 2012, there were 12,224 Filipinos in Belgium.[51]

Belgium: As of 2012, there were 12,224 Filipinos in Belgium.[51] Brazil: As of 2020, there were about 29,578 Filipinos in the South American country.[52]

Brazil: As of 2020, there were about 29,578 Filipinos in the South American country.[52] Brunei: As of 2018, there were more than 20,000 Filipinos living in Brunei.

Brunei: As of 2018, there were more than 20,000 Filipinos living in Brunei..svg.png.webp) Canada: As of 2014, there were 676,775 Filipinos in Canada.[53] See Filipino Canadians.

Canada: As of 2014, there were 676,775 Filipinos in Canada.[53] See Filipino Canadians. Cayman Islands: As of 2010, there were 4,119 Filipinos in Cayman Islands.[54]

Cayman Islands: As of 2010, there were 4,119 Filipinos in Cayman Islands.[54] China: As of 2014, there were 229,638 Filipinos in China.[53]

China: As of 2014, there were 229,638 Filipinos in China.[53] Cuba: As of 2010, there were 9 Filipinos in Cuba.

Cuba: As of 2010, there were 9 Filipinos in Cuba. Denmark: As of 2016, there were at least 8,000 Filipinos in Denmark.[55]

Denmark: As of 2016, there were at least 8,000 Filipinos in Denmark.[55] Egypt: As of 2020, there were 5,717 Filipinos in Egypt.[50]

Egypt: As of 2020, there were 5,717 Filipinos in Egypt.[50] Faroe Islands: As of 2017, a total of about 300 Asian women (from the Philippines and Thailand) are living in the Faroe Islands, married to local men (no numbers given of how many women from each of the two Asian countries).[56]

Faroe Islands: As of 2017, a total of about 300 Asian women (from the Philippines and Thailand) are living in the Faroe Islands, married to local men (no numbers given of how many women from each of the two Asian countries).[56] France: As of 2014, there were 44,967 Filipinos in France.[53]

France: As of 2014, there were 44,967 Filipinos in France.[53] Finland: As of 2019, there are 5,594 people in Finland born in the Philippines.[57]

Finland: As of 2019, there are 5,594 people in Finland born in the Philippines.[57] Germany: As of 2008, there were 65,000 Filipinos in Germany.

Germany: As of 2008, there were 65,000 Filipinos in Germany. Greece: As of 2014, there were 61,681 Filipinos in Greece.[53] See Filipinos in Greece

Greece: As of 2014, there were 61,681 Filipinos in Greece.[53] See Filipinos in Greece Hong Kong: As of 2016 Census, there were 186,869 Filipinos in Hong Kong.[18]

Hong Kong: As of 2016 Census, there were 186,869 Filipinos in Hong Kong.[18] Iceland: As of 2012, there were 2,000 Filipinos in Iceland.

Iceland: As of 2012, there were 2,000 Filipinos in Iceland. India: As of 2021, there were about 2,000 Filipinos in India.[58]

India: As of 2021, there were about 2,000 Filipinos in India.[58] Indonesia: As of 2001, there were 4,800 Filipinos in Indonesia.[59]

Indonesia: As of 2001, there were 4,800 Filipinos in Indonesia.[59] Iraq: As of 2020, there were 1,640 Filipinos in Iraq.[50]

Iraq: As of 2020, there were 1,640 Filipinos in Iraq.[50] Iran: As of 2020, there were 903 Filipinos in Iran.[50]

Iran: As of 2020, there were 903 Filipinos in Iran.[50] Ireland: As of 2013, there were 13,973 Filipinos in Ireland.[13]

Ireland: As of 2013, there were 13,973 Filipinos in Ireland.[13] Israel: As of 2020, there were 29,473 Filipinos in Israel.[50]

Israel: As of 2020, there were 29,473 Filipinos in Israel.[50] Italy: As of 2015, there were 168,238 documented Filipinos living in Italy.[60] See Filipinos in Italy.

Italy: As of 2015, there were 168,238 documented Filipinos living in Italy.[60] See Filipinos in Italy. Jordan: As of 2020, there were 40,538 Filipinos in Jordan.[50]

Jordan: As of 2020, there were 40,538 Filipinos in Jordan.[50] Japan: As of 2020 the Philippine government confirmed there were 325,000 Filipinos in Japan.[8][61] See Filipinos in Japan.

Japan: As of 2020 the Philippine government confirmed there were 325,000 Filipinos in Japan.[8][61] See Filipinos in Japan. Kazakhstan: As of 2008, there were 7,000 Filipinos in Kazakhstan.

Kazakhstan: As of 2008, there were 7,000 Filipinos in Kazakhstan. Kuwait: As of 2020, there were 241,999 Filipinos in Kuwait.[50]

Kuwait: As of 2020, there were 241,999 Filipinos in Kuwait.[50] Lebanon: As of 2020, there were 33,424 Filipinos in Lebanon.[50]

Lebanon: As of 2020, there were 33,424 Filipinos in Lebanon.[50] Libya: As of 2020, there were 2,300 Filipinos in Libya.[50]

Libya: As of 2020, there were 2,300 Filipinos in Libya.[50]

Macau: As of 2012, there were 30,000 Filipinos in Macau.

Macau: As of 2012, there were 30,000 Filipinos in Macau. Morocco: As of 2014, there were 3,000 Filipinos in Morocco.[62]

Morocco: As of 2014, there were 3,000 Filipinos in Morocco.[62] Mexico: As of 2016, there were 1,200 Filipinos in Mexico.[63]

Mexico: As of 2016, there were 1,200 Filipinos in Mexico.[63] Malaysia: As of 2014, there were 620,043 Filipinos in Malaysia.[53] See Filipinos in Malaysia

Malaysia: As of 2014, there were 620,043 Filipinos in Malaysia.[53] See Filipinos in Malaysia Nepal: There are approximately 300 Filipinos in Nepal.

Nepal: There are approximately 300 Filipinos in Nepal. New Zealand: As of 2014, there were 41,146 Filipinos in New Zealand.[53]

New Zealand: As of 2014, there were 41,146 Filipinos in New Zealand.[53] Nigeria: See Filipinos in Nigeria

Nigeria: See Filipinos in Nigeria  Norway: As of 2013, there were about 18,000 Filipinos in Norway,[13] most of them living in the Oslo urban area. In addition to Filipinos who have intermarried with Norwegians, there are at least 900 licensed Filipino nurses, over a hundred oil engineers employed mostly in offshore projects in the western coast of Norway and Filipinos or Norwegians of Filipino descent working in the government sector, diplomatic missions and NGO's and commercial establishments.

Norway: As of 2013, there were about 18,000 Filipinos in Norway,[13] most of them living in the Oslo urban area. In addition to Filipinos who have intermarried with Norwegians, there are at least 900 licensed Filipino nurses, over a hundred oil engineers employed mostly in offshore projects in the western coast of Norway and Filipinos or Norwegians of Filipino descent working in the government sector, diplomatic missions and NGO's and commercial establishments. North Korea: As of 2019, there are 4 Filipinos in North Korea.[53]

North Korea: As of 2019, there are 4 Filipinos in North Korea.[53] Oman: As of 2020, there were 52,760 Filipinos in Oman.[50] See Filipinos in Oman

Oman: As of 2020, there were 52,760 Filipinos in Oman.[50] See Filipinos in Oman Palestine: As of 2020, there were 411 Filipinos in Palestine.[50]

Palestine: As of 2020, there were 411 Filipinos in Palestine.[50] Palau: As of 2006, there were 4,000–7,000 Filipinos in Palau.

Palau: As of 2006, there were 4,000–7,000 Filipinos in Palau. Pakistan: See Filipinos in Pakistan.

Pakistan: See Filipinos in Pakistan. Papua New Guinea: As of 2013, there were 25,000 Filipinos in Papua New Guinea.[64]

Papua New Guinea: As of 2013, there were 25,000 Filipinos in Papua New Guinea.[64] Puerto Rico: As of 2014, there were 91,620 Filipinos in Puerto Rico.[53]

Puerto Rico: As of 2014, there were 91,620 Filipinos in Puerto Rico.[53] Russia: As of 2017, the Philippine Embassy in Moscow counted "around 6,000" Filipinos in Russia.[65] The Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA)'s count rose to "close to 10,000" during the 2022 outbreak of the Russo-Ukrainian War.[66] Given a bilateral labor-agreement in the works (as of 2021),[67] that number is likely to increase, the effects of the war prove affect it enough.

Russia: As of 2017, the Philippine Embassy in Moscow counted "around 6,000" Filipinos in Russia.[65] The Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA)'s count rose to "close to 10,000" during the 2022 outbreak of the Russo-Ukrainian War.[66] Given a bilateral labor-agreement in the works (as of 2021),[67] that number is likely to increase, the effects of the war prove affect it enough. Qatar: As of 2020, there were 241,109 Filipinos in Qatar.[50]

Qatar: As of 2020, there were 241,109 Filipinos in Qatar.[50]

Serbia: As of 2018 there are 76 Filipinos living in Serbia.[68]

Serbia: As of 2018 there are 76 Filipinos living in Serbia.[68] Singapore: As of 2014, there were 200,000 Filipinos in Singapore.[53]

Singapore: As of 2014, there were 200,000 Filipinos in Singapore.[53] South Africa: As of 2008, there were 2,200 Filipinos in South Africa.[69]

South Africa: As of 2008, there were 2,200 Filipinos in South Africa.[69] South Korea: As of 2014, there were 52,379 Filipinos in South Korea.[53]

South Korea: As of 2014, there were 52,379 Filipinos in South Korea.[53] Spain: There are about 200,000 Filipino nationals in Spain.[16] In addition, thousands more hold dual citizenship. Being formerly ruled by Spain, Filipino citizens can apply for dual citizenship within two years residence.[70]

Spain: There are about 200,000 Filipino nationals in Spain.[16] In addition, thousands more hold dual citizenship. Being formerly ruled by Spain, Filipino citizens can apply for dual citizenship within two years residence.[70] Saudi Arabia: As of 2020, there were 865,121 Filipinos in Saudi Arabia.[50]

Saudi Arabia: As of 2020, there were 865,121 Filipinos in Saudi Arabia.[50] Sweden: As of 2018, there were 24,456 Filipinos in Sweden.[71]

Sweden: As of 2018, there were 24,456 Filipinos in Sweden.[71] Switzerland: See Filipinos in Switzerland.

Switzerland: See Filipinos in Switzerland. Thailand: See Filipinos in Thailand.

Thailand: See Filipinos in Thailand. Taiwan: As of 2021, there were 147,000 Filipinos in Taiwan.[53]

Taiwan: As of 2021, there were 147,000 Filipinos in Taiwan.[53] Turkey: As of 2008, there were 5,500 Filipinos in Turkey.[72]

Turkey: As of 2008, there were 5,500 Filipinos in Turkey.[72] Ukraine: As of 2019, there were 342 Filipinos in Ukraine.[73]

Ukraine: As of 2019, there were 342 Filipinos in Ukraine.[73] United Arab Emirates: As of 2020, there were 648,929 Filipinos in the United Arab Emirates.[50]

United Arab Emirates: As of 2020, there were 648,929 Filipinos in the United Arab Emirates.[50] United Kingdom: As of 2014, there were 200,000 Filipinos in the United Kingdom.[53] Nurses and caregivers have begun migrating to the United Kingdom in recent years. The island nation has welcomed thousands of nurses and various other occupations from the Philippines during the past 5 years. Many Filipino seamen settled in British port cities during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Liverpool even had an area nicknamed 'Little Manila'.[74] See Filipinos in the United Kingdom.

United Kingdom: As of 2014, there were 200,000 Filipinos in the United Kingdom.[53] Nurses and caregivers have begun migrating to the United Kingdom in recent years. The island nation has welcomed thousands of nurses and various other occupations from the Philippines during the past 5 years. Many Filipino seamen settled in British port cities during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Liverpool even had an area nicknamed 'Little Manila'.[74] See Filipinos in the United Kingdom. United States: As of 2010, there were 3.4 million Filipinos in the United States, including those of partial descent.[13] Despite race relation problems of the late 19th and early 20th centuries in the American Northwest, most Filipino Americans today find it easy to integrate into American society. Filipinos are the second-largest Asian American group in the country.[75] The United States hosts the largest population of Filipinos outside the Philippines, with a Historic Filipinotown in Los Angeles designated in August 2002, the first district established outside the Philippines to honor and recognize the area's Filipino community.[76][77] The largest population of Filipino Americans reside in California;[78] there are other large populations in the New York metropolitan area, and Hawaii.

United States: As of 2010, there were 3.4 million Filipinos in the United States, including those of partial descent.[13] Despite race relation problems of the late 19th and early 20th centuries in the American Northwest, most Filipino Americans today find it easy to integrate into American society. Filipinos are the second-largest Asian American group in the country.[75] The United States hosts the largest population of Filipinos outside the Philippines, with a Historic Filipinotown in Los Angeles designated in August 2002, the first district established outside the Philippines to honor and recognize the area's Filipino community.[76][77] The largest population of Filipino Americans reside in California;[78] there are other large populations in the New York metropolitan area, and Hawaii. Venezuela: As of 2013, there were about 200 Filipinos living in Venezuela.[13]

Venezuela: As of 2013, there were about 200 Filipinos living in Venezuela.[13] Yemen: As of 2020, there were 150 Filipinos in Yemen.[50]

Yemen: As of 2020, there were 150 Filipinos in Yemen.[50]

See also

- Balikbayan box

- Filipinos in the New York metropolitan area

- Human migration

- Overseas Filipino Worker

References

- "Duterte's 'golden age' comes into clearer view". Asia Times. September 2, 2019.

- "Remittances from Filipinos abroad reach 2.9 bln USD in August 2019 - Xinhua | English.news.cn". www.xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on October 15, 2019.

- Bureau, INQUIRER NET U. S. (September 17, 2018). "New Census data: More than 4 million Filipinos in the US". INQUIRER.net USA.

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census - Canada [Country] and Canada [Country]".

- Government source June 2015

- "Know Your Diaspora: United Arab Emirates". Positively Filipino | Online Magazine for Filipinos in the Diaspora.

- Osaki, Tomohiro; Masangkay, May (January 3, 2018). "Filipinos and Nepalese face challenges in Japan even as their communities grow" – via Japan Times Online.

- Aguilar, Krissy (April 1, 2020). "2 Filipinos in Japan may be COVID-19 positive, says PH Embassy". INQUIRER.net.

- "Australia General Community Profile". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- Michaelson, Ruth (23 July 2018). "Kuwaiti star faces backlash over Filipino worker comments". The Guardian. United Kingdom. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

The Philippine president, Rodrigo Duterte, asked the estimated 276,000 Filipino workers in Kuwait to return home, appealing to “their sense of patriotism” and offering free flights for the 10,000 estimated to have overstayed their visas.

- "No foreign workers' layoffs in Malaysia - INQUIRER.net, Philippine News for Filipinos". 9 February 2009.

- Rivera, Raynald C (17 October 2017). "Contribution of over 240,000 Filipinos in Qatar praised". The Peninsula. Qatar. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

Timbayan underlined the important contribution of more than 240,000 Filipinos in Qatar engaged in various sectors, being the fourth largest expatriate community in Qatar.

- "Stock Estimate of Filipinos Overseas As of December 2013" (PDF). Philippine Overseas Employment Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 23, 2019.

- "Filipinos in France". September 22, 2020. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- "Les nouveaux Misérables: the lives of Filipina workers in the playground of the rich". theguardian.com. October 12, 2020. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- Masigan, Andrew J. (June 24, 2018). "Economic diplomacy is as important as OFW diplomacy". BusinessWorld. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

- Gostoli, Ylenia. "Coronavirus: Filipino front-line workers pay ultimate price in UK". www.aljazeera.com.

- A122: Population by Nationality, Year and Duration of Residence in Hong Kong Hong Kong Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- "I cittadini non comunitari regolarmente soggiornanti". 31 December 2014. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014.

- Imigrantes internacionais registrados (Registro Nacional de Estrangeiro - RNE/ Registro Nacional Migratório - RNM

- Asis, Maruja M.B. (January 2006). "The Philippines' Culture of Migration". Migration Information Source. Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved December 14, 2009.

- "Selected Population Profile in the United States: Filipino alone or in any combination". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 10, 2020. Retrieved February 1, 2009. The U.S. Census Bureau 2007 American Community Survey counted 3,053,179 Filipinos; 2,445,126 native and naturalized citizens, 608,053 of whom were not U.S. citizens.

- Global Pinoys to rally at Chinese consulates – The Philippine Star » News » Headlines Archived June 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. The Philippine Star (April 27, 2012). Retrieved on July 4, 2012.

- McKenzie, Duncan Alexander (2012). The Unlucky Country: The Republic of the Philippines in the 21St Century. Bloomington, IN: Balboa Press. p. 138. ISBN 9781452503363.

- David K. Yoo; Eiichiro Azuma (4 January 2016). The Oxford Handbook of Asian American History. Oxford University Press. p. 402. ISBN 978-0-19-986047-0.

- IMF (2013). Philippines: Selected Issues. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund Publication Services. p. 17. ISBN 9781484374061.

- Almendral, Aurora; Reyes Morales, Hannah (December 2018). "Why 10 million Filipinos endure hardship abroad as overseas workers". National Geographic. United States. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- "Unsung Filipino seafarers power the global economy". The Economist. 16 February 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

Kale Bantigue Fajardo. Filipino Crosscurrents: Oceanographies of Seafaring, Masculinities, and Globalization. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-1-4529-3283-5.

Leon Fink (2011). Sweatshops at Sea: Merchant Seamen in the World's First Globalized Industry, from 1812 to the Present. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-8078-3450-3. - Rupert, Mark; Solomon, Scott (2006). Globalization and International Political Economy: The Politics of Alternative Futures. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 88. ISBN 978-0742529434.

- Remo, Michelle V. (14 November 2012). "Stop illegal remittance agents, BSP urged: Informal forex channels a problem in the region". Philippine Daily Inquirer.

- Magtulis, Prinz (15 November 2012). "Remittance growth poised to meet full-year forecast - BSP". The Philippine Star.

- Lucas, Daxim L. (16 February 2019). "2018 remittances hit all-time high". business.inquirer.net.

- Acedera, Kristel Anne; Yeoh, Brenda SA (2018-09-13). "'Making time': Long-distance marriages and the temporalities of the transnational family". Current Sociology. 67 (2): 250–272. doi:10.1177/0011392118792927. ISSN 0011-3921. PMC 6402049. PMID 30886440.

- Dalgas, Karina Märcher (2016-06-02). "The mealtimes that bind? Filipina au pairs in Danish families". Gender, Place & Culture. 23 (6): 834–849. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2015.1073696. ISSN 0966-369X. S2CID 143360798.

- Lindio-McGovern, Ligaya (June 2004). "Alienation and labor export in the context of globalization: Filipino migrant domestic workers in Taiwan and Hong Kong". Critical Asian Studies. 36 (2): 217–238. doi:10.1080/14672710410001676043. ISSN 1467-2715. S2CID 153291868.

- Basa, Charito; Harcourt, Wendy; Zarro, Angela (2011-03-01). "Remittances and transnational families in Italy and The Philippines: breaking the global care chain". Gender & Development. 19 (1): 11–22. doi:10.1080/13552074.2011.554196. ISSN 1355-2074. S2CID 144631953.

- UN (2007). " A call for equality.". The state of the worlds children. pp. 1–15. Retrieved 2014-05-18

- Oishi, Nana (March 2002). "Gender and Migration: An Integrative Approach eScholarship". Escholarship.org. Retrieved 2014-07-09.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Leonard, John (2008-07-03). "OFW rights violation worsens under the Arroyo administration". Filipino OFWs Qatar. Archived from the original on 2009-01-07. Retrieved 2009-01-25.

- Oishi, N. (March 2002). "Gender and migration: an integrated approach". Escolarship.org.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Tanyag, Maria (2017-01-02). "Invisible labor, invisible bodies: how the global political economy affects reproductive freedom in the Philippines". International Feminist Journal of Politics. 19 (1): 39–54. doi:10.1080/14616742.2017.1289034. ISSN 1461-6742. S2CID 157252223.

- Lindio-McGovern, Ligaya (June 2004). "Alienation and labor export in the context of globalization". Critical Asian Studies. 36 (2): 217–238. doi:10.1080/14672710410001676043. ISSN 1467-2715. S2CID 153291868.

- Beneria, L. Deere; Kabeer, C. (2012). "Gender and international migration: globalization, development and governance". Feminist Economics. 18 (2): 1–33. doi:10.1080/13545701.2012.688998. S2CID 144565818.

- Nozomi, Y. (February 2014). "Policy review: Japan-Philippines economic partnership agreement, analysis of a failed nurse migration policy". International Journal of Nursing Studies. 51 (2): 243–250. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.05.006. PMID 23787219.

- Lorenzo, E. (June 2007). "Nursing migration from a source country perspective: Philippine country case study". Health Serv Res. 42 (3p2): 1406–18. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00716.x. PMC 1955369. PMID 17489922.

- Haksar, Mr. V. (2005). "Migration and Foreign Remittances in the Philippines". IMF working paper: Asia and Pacific department. p. 3.

- "Global Migration Map: Origins and Destinations, 1990-2017". Pew Research Center's Global Attitudes Project. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- "2016 Census QuickStats: Australia". www.censusdata.abs.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2018-01-20. Retrieved 2017-08-12.

- "AMBASSADOR MARIA CLEOFE NATIVIDAD PRESENTS CREDENTIALS TO AUSTRIAN FEDERAL PRESIDENT ALEXANDER VAN DER BELLEN". Philippine Department of Foreign Affairs. 23 January 2018.

- "Population of Overseas Filipinos in the Middle East and North Africa". Department of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 27 June 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- "Imigrantes internacionais registrados no Brasil". www.nepo.unicamp.br. Retrieved 2021-08-20.

- "Distribution on Filipinos Overseas". Department of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 26 November 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- "Immigrants in Denmark, 2016 Census".

- "Wives wanted in the Faroe Islands" by Tim Ecott, BBC News, 27 April 2017

- "PX-Web - Valitse muuttuja ja arvot". Archived from the original on 2018-06-29. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- Moaje, Marita (April 30, 2021). "OFW in India sees each day as battle for survival". Philippine News Agency. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- "Notizie sulla presenza straniera in Italia". www.istat.it. October 30, 2011.

- Catolico, Gianna Francesca (29 September 2016). "Filipinos 3rd largest group in Japan—report". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- "Stronger PH Ties with Russia Seen as Cayetano Visits Moscow". Department of Foreign Affairs (Philippines). 16 May 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- "Gov't to help OFWs in Russia as economic sanctions bite". Philippine News Agency. 23 March 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- "Russia eyes bilateral labor agreement with PH". Philippine News Agency. 6 March 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- "PH Consulate in Belgrade Opens For Filipinos in Serbia". Philippine Department of Foreign Affairs. 18 July 2018.

- Gutierrez, Pia (March 27, 2014). "Spain clarifies legislation offering citizenship". ABS-CBN News and Current Affairs. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- Befolkningsstatistik

- "Filipinos in Liverpool, Part 1". Filipinohome.com. 1915-05-04. Retrieved 2014-07-09.

- Rueda, Nimfa U. (25 March 2012). "Filipinos 2nd largest Asian group in US, census shows". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

Kevin L. Nadal (23 March 2011). Filipino American Psychology: A Handbook of Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice. John Wiley & Sons. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-118-01977-1.

Min Zhou; Anthony C. Ocampo (19 April 2016). Contemporary Asian America (third Edition): A Multidisciplinary Reader. NYU Press. p. 292. ISBN 978-1-4798-2923-1. - "Historic Filipinotown - Things to Do". VisitAsianLA.org. Retrieved 2014-07-09.

- "Background Note: Philippines". U.S. Department of State: Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs. May 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-02.

There are an estimated four million Americans of Filipino ancestry in the United States, and more than 250,000 American citizens in the Philippines.

- Melendez, Lyanne (17 December 2018). "Bay Area Filipinos react to new Miss Universe 2018". KGO. San Francisco. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

California is home to the largest Filipino population in the U.S.

Maria P. P. Root (20 May 1997). Filipino Americans: Transformation and Identity. SAGE. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-7619-0579-0.

Kyle L. Kreider; Thomas J. Baldino; Joaquin Jay Gonzalez III (7 December 2015). "Filipino American Voting". Minority Voting in the United States [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. pp. 265–280. ISBN 978-1-4408-3024-2.

Further reading

- Terry, William (2014). "The perfect worker: discursive makings of Filipinos in the workplace hierarchy of the globalized cruise industry". Social & Cultural Geography. 15 (1): 73–79. doi:10.1080/14649365.2013.864781. S2CID 143393473. Retrieved 5 March 2007.

External links

General statistics from Philippine government

- POEA2004 a b c d e f g h i "Stock Estimate of Filipinos Overseas" (MS Excel). Philippine Overseas Employment Administration. 2004. Retrieved 2007-08-01. (overseas Filipinos working and/or living overseas):

- 3,187,586 stay permanently, 3,599,257 stay for work contracts, and 1,296,972 stay irregularly (without proper documents), which make a sum of 8,083,815.

- Press release on the 2004 Survey on Overseas Filipinos, Philippine Statistics Authority, on OFWs:

- 1.06 million Overseas Filipino Workers

- 33.4% are unskilled workers, 15.4% are Trades and related workers, 15.1% are plant and machine operators and assemblers.

- 49.3% are males, 50.7% are females.

- Remittances are 64.7 billion Philippine pesos (equaled US$1.2 billion then)

- Deployed Landbased Overseas Filipino Workers by Destination (New hires and Rehires) (MS Excel format), Philippine Overseas Employment Administration, 2005, on OFWs:

- 733,970 are landbased, 247,707 are seabased, which make a sum of 981,677. There is a 5.15% growth since 2004's 933,588.

- Remittances are US$9,727,138,000. There is a 26.6% growth since 2004.

- List of Additional Reports from the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration Statistics Page

From other sources

- a b AUS - "1301.0 - Year Book Australia, 2012 - Population - Country of Birth". Australia Bureau of Statistics. 2012. Retrieved 2013-08-30..

- a GWM - "Country Profile: Guam - People". CIA Factbook. Retrieved 2007-05-12..

- a LBN - Maila Ager (3 August 2006). "'Standby fund' for OFWs in Lebanon gets House committee nod". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-09..

- a NZL - "QuickStats About Culture and Identity". Statistics New Zealand Tatauranga Aotearoa. 3 August 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-08-29. Retrieved 2007-05-12..

- a SAU - "Table 29. Stock Estimate of Filipinos Overseas As of December 2006" (PDF). Philippine Overseas Employment Administration. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-08. Retrieved 2007-09-01..

- a b TWN - Alien Workers in Taiwan-Fukien Area by Industry and Nationality (JPG and PDF format), 2006 February, CLA, Taiwan.

- a MAL - "Table 29. Stock Estimate of Filipinos Overseas As of December 2006" (PDF). Philippine Overseas Employment Administration. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-08. Retrieved 2007-09-01..

- USA

- a1 "Selected Population Profile in the United States - Population Group: Filipino alone or in any combination". U.S. Census Bureau. 2005. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

Population Group: Filipino alone or in any combination - Total population: 288,378,137

. - b1 b2 United States Census Bureau (2007). "Background Note: Philippines". U.S. Department of State, Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs. Retrieved 2006-11-04.

There are an estimated four million Americans of Filipino ancestry in the United States, and more than 250,000 American citizens in the Philippines.

- a1 "Selected Population Profile in the United States - Population Group: Filipino alone or in any combination". U.S. Census Bureau. 2005. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- a ARE – Jose N. Franco Jr (28 April 2007). "Jan–Feb 2007 remittances by Filipinos in Dubai grow 96pc". Khaleej Times. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- a AUS – "Year Book Australia, 2007 Contents >> Population >> Country of birth". Australia Bureau of Statistics. 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-08.

- a CAN – "Population by Ethnic Origin". Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. Archived from the original on 2007-04-09. Retrieved 2007-05-08.

- a GWM – "Country Profile: Guam – People". CIA Factbook. Retrieved 2007-05-12.

- a IRL – Central Statistics Office Ireland. "Principal Statistics of Ireland by nationality". Archived from the original on 2007-04-06. Retrieved 2007-04-12.

- a ITA – Lawrence Casiraya. "Microsoft training centers cater to 200,000 OFWs in Italy". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 2007-08-14.

- a JPN – "Undocumented Filipinos cross the great divide in Japan". Philippines Today. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- a LBN – Maila Ager (3 August 2006). "'Standby fund' for OFWs in Lebanon gets House committee nod". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- a NZL – "QuickStats About Culture and Identity". Statistics New Zealand Tatauranga Aotearoa. 3 August 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-08-29. Retrieved 2007-05-12.

- a ROK – "Secretary Albert Assures Filipinos in Korea of Continued Government Protection for Their Interests". Philippine Department of Foreign Affairs. 3 August 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-08-05. Retrieved 2007-05-12.

- a SAU – "International Religious Freedom Report 2005 – Saudi Arabia". Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, U.S. Department of State. 2005. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- a TWN – Alien Workers in Taiwan-Fukien Area by Industry and Nationality (JPG and PDF format), 2006 February, CLA, Taiwan.

- USA

- a1 "Selected Population Profile in the United States – Population Group: Filipino alone or in any combination". U.S. Census Bureau. 2005. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

Population Group: Filipino alone or in any combination: 2,807,731

- b1 United States Census Bureau (May 2007). "Background Note: Philippines". U.S. Department of State, Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs. Retrieved 2007-09-02.

There are an estimated four million Americans of Filipino ancestry in the United States, and more than 250,000 American citizens in the Philippines.

- a1 "Selected Population Profile in the United States – Population Group: Filipino alone or in any combination". U.S. Census Bureau. 2005. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- Overseas Filipino