Sea Peoples

The Sea Peoples are a hypothesized seafaring confederation that attacked ancient Egypt and other regions in the East Mediterranean prior to and during the Late Bronze Age collapse (1200–900 BCE).[1][2] Following the creation of the concept in the 19th century, the Sea Peoples' incursions became one of the most famous chapters of Egyptian history, given its connection with, in the words of Wilhelm Max Müller, "the most important questions of ethnography and the primitive history of classic nations".[3][4]

The origins of the Sea Peoples are undocumented. It has been proposed that the Sea Peoples originated from a number of different locations, such as western Asia Minor, the Aegean, the Mediterranean islands, and Southern Europe.[5] Although the archaeological inscriptions do not include reference to a migration,[2] the Sea Peoples are conjectured to have sailed around the eastern Mediterranean and invaded Anatolia, Syria, Phoenicia, Canaan, Cyprus, and Egypt toward the end of the Bronze Age.[6]

French Egyptologist Emmanuel de Rougé first used the term peuples de la mer (literally "peoples of the sea") in 1855 in a description of reliefs on the Second Pylon at Medinet Habu, documenting Year 8 of Ramesses III.[7][8] In the late 19th century, Gaston Maspero, de Rougé's successor at the Collège de France, subsequently popularized the term "Sea Peoples" and an associated migration theory.[9] Since the early 1990s, his migration theory has been brought into question by a number of scholars.[1][2][10][11]

The Sea Peoples remain unidentified in the eyes of most modern scholars, and hypotheses regarding the origin of the various groups are the source of much speculation.[12] Existing theories variously propose that they were any of several Aegean tribes, raiders from Central Europe, scattered soldiers who turned to piracy or became refugees, or migrants linked to natural disasters such as earthquakes or climatic shifts.[2][13]

History of the concept

The concept of the Sea Peoples was first described by Emmanuel de Rougé in 1855, then curator of the Louvre, in his work Note on Some Hieroglyphic Texts Recently Published by Mr. Greene,[16] describing the battles of Ramesses III described on the Second Pylon at Medinet Habu, and based upon recent photographs of the temple by John Beasley Greene.[17][18][19] De Rougé noted that "in the crests of the conquered peoples the Sherden and the Teresh bear the designation of the peuples de la mer", in a reference to the prisoners depicted at the base of the Fortified East Gate.[8] In 1867, de Rougé published his Excerpts of a dissertation on the attacks directed against Egypt by the peoples of the Mediterranean in the 14th century BCE, which focused primarily on the battles of Ramesses II and Merneptah and which proposed translations for many of the geographic names included in the hieroglyphic inscriptions.[20][21] De Rougé later became chair of Egyptology at the Collège de France and was succeeded by Gaston Maspero. Maspero built upon de Rougé's work and published The Struggle of the Nations,[22] in which he described the theory of the seaborne migrations in detail in 1895–96 for a wider audience,[9] at a time when the idea of population migrations would have felt familiar to the general population.[23]

The migration theory was taken up by other scholars such as Eduard Meyer and became the generally accepted theory amongst Egyptologists and Orientalists.[9] Since the early 1990s, however, it has been brought into question by a number of scholars.[1][2][10][11]

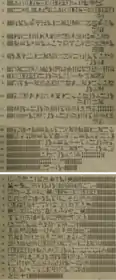

The historical narrative stems primarily from seven Ancient Egyptian sources[24] and although in these inscriptions the designation "of the sea" does not appear in relation to all of these peoples,[1][11] the term "Sea Peoples" is commonly used in modern publications to refer to the following nine peoples, in alphabetical order:[25][26]

| Egyptian name | Original identification | Other theories | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| People | Trans- literation |

Connection to the sea | Year | Author | Theory | |||

| Denyen | d3jnjw | "in their isles"[27] | 1872 | Chabas[28] | Greek (Danaoi)[29] | Israelite tribe of Dan,[29] Daunians,[30] Dorians,[31][32] Land of the Danuna near Ugarit[33] | ||

| Ekwesh | jḳ3w3š3 | "of the countries of the sea"[34] | 1867 | de Rougé[28] | Greeks (Achaeans)[35][29][36] | |||

| Lukka | rkw | 1867 | de Rougé[28] | Lycians[36][35] | ||||

| Peleset | prwsṯ | 1846

1872 |

William Osborn Jr. and Edward Hincks[37][38][39][40]

Chabas[41] |

Pelasgians | Parišta/Assuwa in Western Anatolia.[42]

Palistin in Southern Anatolia and Northern Syria.[42] | |||

| Shekelesh | š3krš3 | "of the countries of the sea"[43] (disputed)[34] | 1867 | de Rougé[28] | Sicels[36][35] | Cyclades[44]

Sagalassos[45] Saḫiriya (Sakariya)[42] | ||

| Sherden | š3rdn | "of the sea"[46] "of the countries of the sea"[43] (disputed)[34] |

1867 | de Rougé[28] | Sardinians (Nuragic)[35][36][47][48] | Sardis[45] | ||

| Teresh | twrš3 | "of the sea"[46] | 1867 | de Rougé[28] | Tyrrhenians[35][36][49] | Troy (Taruisa) [50] Tribe of Tiras[51] | ||

| Tjeker | ṯ3k3r | 1867, 1872 | Lauth, Chabas[28] | Teucrians[52] | Zakro, Crete[53] Eteocretans[54] Thrace[55] Sicals form Southern Phonecia[56] Sicels[57] | |||

| Weshesh | w3š3š3 | "of the sea"[27] | 1872 | Chabas[28] | Greeks (Achaeans)[35][29][36][28] | Assuwa/Waršiya in Western Anatolia.[42] Cretan Waksioi[58] Predecessor of the Osci[59] The Israelite tribe of Asher.[60][61] Wassos[62] Considered by others to remain unidentified.[41] | ||

Primary documentary records

The Medinet Habu inscriptions from which the Sea Peoples concept was first described remain the primary source and "the basis of virtually all significant discussions of them".[63]

Three separate narratives from Egyptian records refer to more than one of the nine peoples, found in a total of six sources. The seventh and most recent source referring to more than one of the nine peoples is a list (Onomasticon) of 610 entities, rather than a narrative.[24] These sources are summarized in the table below.

| Date | Narrative | Source(s) | Peoples named | Connection to the sea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1210 BCE | Ramesses II narrative | Kadesh Inscriptions | Karkisha, Lukka, Sherden | none |

| c. 1200 BCE | Merneptah narrative | Great Karnak Inscription | Eqwesh, Lukka, Shekelesh, Sherden, Teresh | Eqwesh (of the countries of the sea),[34] possibly also Sherden and Sheklesh[43] |

| Athribis Stele | Eqwesh, Shekelesh, Sherden, Teresh | Eqwesh (of the countries of the sea)[34][43] | ||

| c. 1150 BCE | Ramesses III narrative | Medinet Habu | Denyen, Peleset, Shekelesh, Sherden, Teresh, Tjekker, Weshesh | Denyen (in their isles), Teresh (of the sea), Sherden (of the sea)[46] |

| Papyrus Harris I | Denyen, Peleset, Sherden, Tjekker, Weshesh | Denyen (in their isles), Weshesh (of the sea)[27] | ||

| Rhetorical Stela | Peleset, Teresh | none | ||

| c. 1100 BCE | List (no narrative) | Onomasticon of Amenope | Denyen, Lukka, Peleset, Sherden, Tjekker | none |

Ramesses II narrative

Possible records of sea peoples generally or in particular date to two campaigns of Ramesses II, a pharaoh of the militant 19th Dynasty: operations in or near the delta in Year 2 of his reign and the major confrontation with the Hittite Empire and allies at the Battle of Kadesh in his Year 5. The years of this long-lived pharaoh's reign are not known exactly, but they must have comprised nearly all of the first half of the 13th century BCE.[64]

In his Second Year, an attack of the Sherden, or Shardana, on the Nile Delta was repulsed and defeated by Ramesses, who captured some of the pirates. The event is recorded on Tanis Stele II.[65] An inscription by Ramesses II on the stela from Tanis which recorded the Sherden raiders' raid and subsequent capture speaks of the continuous threat they posed to Egypt's Mediterranean coasts:

the unruly Sherden whom no one had ever known how to combat, they came boldly sailing in their warships from the midst of the sea, none being able to withstand them.[66]

The Sherden prisoners were subsequently incorporated into the Egyptian army for service on the Hittite frontier by Ramesses and fought as Egyptian soldiers in the Battle of Kadesh. Another stele usually cited in conjunction with this one is the "Aswan Stele" (there were other stelae at Aswan), which mentions the king's operations to defeat a number of peoples including those of the "Great Green (the Egyptian name for the Mediterranean)". It is plausible to assume that the Tanis and Aswan Stelae refer to the same event, in which case they reinforce each other.

The Battle of Kadesh was the outcome of a campaign against the Hittites and their allies in the Levant in the pharaoh's Year 5. The imminent collision of the Egyptian and Hittite empires became obvious to both, and they both prepared campaigns against the strategic midpoint of Kadesh for the next year. Ramesses divided his Egyptian forces, which were then ambushed piecemeal by the Hittite army and nearly defeated. Ramesses was separated from his forces and had to fight singlehandedly to get back to his troops. He then mustered several counterattacks while waiting for reinforcements. Once the reinforcements from the South and East arrived, the Egyptians managed to drive the Hittites back to Kadesh. While it was a strategic Egyptian victory, neither side managed to attain their operational objectives.[67]

At home, Ramesses had his scribes formulate an official description, which has been called "the Bulletin" because it was widely published by inscription. Ten copies survive today on the temples at Abydos, Karnak, Luxor and Abu Simbel, with reliefs depicting the battle. The "Poem of Pentaur", describing the battle survived also.[68]

The poem relates that the previously captured Sherden were not only working for the Pharaoh but were also formulating a plan of battle for him; i.e. it was their idea to divide Egyptian forces into four columns. There is no evidence of any collaboration with the Hittites or malicious intent on their part, and if Ramesses considered it, he never left any record of that consideration.

The poem lists the peoples who went to Kadesh as allies of the Hittites. Amongst them are some of the sea peoples spoken of in the Egyptian inscriptions previously mentioned, and many of the peoples who would later take part in the great migrations of the 12th century BCE (see Appendix A to the Battle of Kadesh).

Merneptah narrative

The major event of the reign of the Pharaoh Merneptah (1213 BCE – 1203 BCE),[69] 4th king of the 19th Dynasty, was his battle at Perire in the western delta in the 5th and 6th years of his reign, against a confederacy termed "the Nine Bows". Depredations of this confederacy had been so severe that the region was "forsaken as pasturage for cattle, it was left waste from the time of the ancestors".[70]

The pharaoh's action against them is attested in a single narrative found in three sources. The most detailed source describing the battle is the Great Karnak Inscription; two shorter versions of the same narrative are found in the "Athribis Stele" and the "Cairo Column".[71] The "Cairo column" is a section of a granite column now in the Cairo Museum, which was first published by Maspero in 1881 with just two readable sentences – the first confirming the date of Year 5 and the second stating: "The wretched [chief] of Libya has invaded with ——, being men and women, Shekelesh (S'-k-rw-s) ——".[72][73] The "Athribis stela" is a granite stela found in Athribis and inscribed on both sides, which like the Cairo column, was first published by Maspero two years later in 1883.[74] The Merneptah Stele from Thebes describes the reign of peace resulting from the victory but does not include any reference to the Sea Peoples.[75]

The Nine Bows were acting under the leadership of the king of Libya and an associated near-concurrent revolt in Canaan involving Gaza, Ashkelon, Yenoam and the people of Israel. Exactly which peoples were consistently in the Nine Bows is not clear, but present at the battle were the Libyans, some neighboring Meshwesh, and possibly a separate revolt in the following year involving peoples from the eastern Mediterranean, including the Kheta (or Hittites), or Syrians, and (in the Israel Stele) for the first time in history, the Israelites. In addition to them, the first lines of the Karnak inscription include some sea peoples,[76] which must have arrived in the Western Delta or from Cyrene by ship:

[Beginning of the victory that his majesty achieved in the land of Libya] -i, Ekwesh, Teresh, Lukka, Sherden, Shekelesh, Northerners coming from all lands.

Later in the inscription Merneptah receives news of the attack:

... the third season, saying: "The wretched, fallen chief of Libya, Meryey, son of Ded, has fallen upon the country of Tehenu with his bowmen – Sherden, Shekelesh, Ekwesh, Lukka, Teresh, Taking the best of every warrior and every man of war of his country. He has brought his wife and his children – leaders of the camp, and he has reached the western boundary in the fields of Perire"

"His majesty was enraged at their report, like a lion", assembled his court and gave a rousing speech. Later, he dreamed he saw Ptah handing him a sword and saying, "Take thou (it) and banish thou the fearful heart from thee." When the bowmen went forth, says the inscription, "Amun was with them as a shield." After six hours, the surviving Nine Bows threw down their weapons, abandoned their baggage and dependents, and ran for their lives. Merneptah states that he defeated the invasion, killing 6,000 soldiers and taking 9,000 prisoners. To be sure of the numbers, among other things, he took the penises of all uncircumcised enemy dead and the hands of all the circumcised, from which history learns that the Ekwesh were circumcised, a fact causing some to doubt they were Greek.[77]

Ramesses III narrative

"Now the northern countries, which were in their isles, were quivering in their bodies. They penetrated the channels of the Nile's mouths. Their nostrils have ceased (to function, so that) their desire is [to] breathe the breath. His majesty is gone forth like a whirlwind against them, fighting on the battlefield like a runner. The dread of him and the terror of him have entered in their bodies; (they are) capsized and overwhelmed in their places. Their hearts are taken away; their soul is flown away. Their weapons are scattered in the sea. His arrow pierces him whom he has wished among them, while the fugitive becomes one fallen into the water. His majesty is like an enraged lion, attacking his assailant with his pawns; plundering on his right hand and powerful on his left hand, like Set[h] destroying the serpent 'Evil of Character'. It is Amon-Re who has overthrown for him the lands and has crushed for him every land under his feet; King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Lord of the Two Lands: Usermare-Meriamon."[78]

Ramesses III, who reigned for most of the first half of the 12th century BCE as the second pharaoh of the 20th Dynasty, confronted a later wave of invasions of the Sea Peoples in his eighth year. The battles were later recorded in two long inscriptions from his Medinet Habu mortuary temple, which are physically separate and somewhat different from one another.[79] The Year 8 campaign is the best-recorded Sea Peoples invasion.

The fact that several civilizations collapsed around 1175 BCE has led to the suggestion that the Sea Peoples may have been involved at the end of the Hittite, Mycenaean and Mitanni kingdoms. The American Hittitologist Gary Beckman writes, on page 23 of Akkadica 120 (2000):[80]

A terminus ante quem for the destruction of the Hittite empire has been recognized in an inscription carved at Medinet Habu in Egypt in the eighth year of Ramesses III (1175 BCE). This text narrates a contemporary great movement of peoples in the eastern Mediterranean, as a result of which "the lands were removed and scattered to the fray. No land could stand before their arms, from Hatti, Kode, Carchemish, Arzawa, Alashiya on being cut off. [ie: cut down]"

Ramesses' comments about the scale of the Sea Peoples' onslaught in the eastern Mediterranean are confirmed by the destruction of the states of Hatti, Ugarit, Ashkelon and Hazor around this time. As the Hittitologist Trevor Bryce observes:[81]

It should be stressed that the invasions were not merely military operations, but involved the movements of large populations, by land and sea, seeking new lands to settle.

This situation is confirmed by the Medinet Habu temple reliefs of Ramesses III which show that:[81]

the Peleset and Tjekker warriors who fought in the land battle [against Ramesses III] are accompanied in the reliefs by women and children loaded in ox-carts.

_01.jpg.webp)

"Thou puttest great terror of me in the hearts of their chiefs; the fear and dread of me before them; that I may carry off their warriors (phrr), bound in my grasp, to lead them to thy ka, O my august father, – – – – –. Come, to [take] them, being: Peleset (Pw-r'-s'-t), Denyen (D'-y-n-yw-n'), Shekelesh (S'-k-rw-s). Thy strength it was which was before me, overthrowing their seed, – thy might, O lord of gods."[82]

On the right hand side of the Pylon is the "Great Inscription on the Second Pylon", which includes the following text:

"The foreign countries made a conspiracy in their islands, All at once the lands were removed and scattered in the fray. No land could stand before their arms: from Hatti, Qode, Carchemish, Arzawa and Alashiya on, being cut off [i.e. destroyed] at one time. A camp was set up in Amurru. They desolated its people, and its land was like that which has never come into being. They were coming forward toward Egypt, while the flame was prepared before them. Their confederation was the Peleset, Tjeker, Shekelesh, Denyen and Weshesh, lands united. They laid their hands upon the land as far as the circuit of the earth, their hearts confident and trusting: 'Our plans will succeed!'"[83]

The inscriptions of Ramesses III at his Medinet Habu mortuary temple in Thebes record three victorious campaigns against the Sea Peoples that are considered bona fide, in Years 5, 8 and 12, as well as three considered spurious, against the Nubians and Libyans in Year 5 and the Libyans with Asiatics in Year 11. During Year 8 some Hittites were operating with the Sea Peoples.[84]

The inner west wall of the second court describes the invasion of Year 5. Only the Peleset and Tjeker are mentioned, but the list is lost in a lacuna. The attack was two-pronged, one by sea and one by land. That is, the Sea Peoples divided their forces. Ramesses was waiting in the Nile mouths and trapped the enemy fleet there. The land forces were defeated separately.

The Sea Peoples did not learn any lessons from this defeat, as they repeated their mistake in Year 8 with a similar result. The campaign is recorded more extensively on the inner northwest panel of the first court. It is possible, but not generally believed, that the dates are only those of the inscriptions and both refer to the same campaign.

In Ramesses' Year 8, the Nine Bows appear again as a "conspiracy in their isles". This time, they are revealed unquestionably as Sea Peoples: the Peleset, Tjeker, Shekelesh, Denyen and Weshesh, which are classified as "foreign countries" in the inscription. They camped in Amor and sent a fleet to the Nile.

The pharaoh was once more waiting for them. He had built a fleet especially for the occasion, hid it in the Nile's mouths and posted coast watchers. The enemy fleet was ambushed there, their ships overturned, and the men dragged up on shore and executed ad hoc.

The land army was also routed within Egyptian controlled territory. Additional information is given in the relief on the outer side of the east wall. This land battle occurred in the vicinity of Djahy against "the northern countries". When it was over, several chiefs were captive: of Hatti, Amor and Shasu among the "land peoples" and the Tjeker, "Sherden of the sea", "Teresh of the sea" and Peleset or Philistines.

The campaign of Year 12 is attested by the Südstele found on the south side of the temple. It mentions the Tjeker, Peleset, Denyen, Weshesh and Shekelesh.

Papyrus Harris I of the period, found behind the temple, suggests a wider campaign against the Sea Peoples but does not mention the date. In it, the persona of Ramses III says, "I slew the Denyen (D'-yn-yw-n) in their isles" and "burned" the Tjeker and Peleset, implying a maritime raid of his own. He also captured some Sherden and Weshesh "of the sea" and settled them in Egypt.[85] As he is called the "Ruler of Nine Bows" in the relief of the east side, these events probably happened in Year 8; i.e. the Pharaoh would have used the victorious fleet for some punitive expeditions elsewhere in the Mediterranean.

The Rhetorical Stela to Ramesses III, Chapel C, Deir el-Medina records a similar narrative.[86]

Onomasticon of Amenope

The Onomasticon of Amenope, or Amenemipit (amen-em-apt), gives slight credence to the idea that the Ramesside kings settled the Sea Peoples in Canaan. Dated to about 1100 BCE (at the end of the 22nd dynasty) this document simply lists names. After six place names, four of which were in Philistia, the scribe lists the Sherden (Line 268), the Tjeker (Line 269) and the Peleset (Line 270), who might be presumed to occupy those cities.[87] The Story of Wenamun on a papyrus of the same cache also places the Tjeker in Dor at that time. The fact that the Biblical maritime Tribe of Dan was initially located between the Philistines and the Tjekker, has prompted some to suggest that they may have originally been Denyen. Sherden seem to have been settled around Megiddo and in the Jordan Valley, and Weshwesh (connected by some with the Biblical tribe of Asher) may have been settled further north.

Other documentary records

Egyptian single-name sources

Other Egyptian sources refer to one of the individual groups without reference to any of the other groups.[24]

The Amarna letters, around the mid-14th century BCE, including four relating to the Sea Peoples:

- EA 151 refers to the Denyen, in a passing reference to the death of their king;

- EA 38 refers to the Lukka, who are being accused of attacking the Egyptians in conjunction with the Alashiyans (Cypriotes), with the latter having stated that the Lukka were seizing their villages.

- EA 81, EA 122 and EA 133 refer to the Sherden. The letters at one point refer to a Sherden man as an apparent renegade mercenary,[88] and at another point to three Sherden who are slain by an Egyptian overseer.[89]

Padiiset's Statue refers to the Peleset, the Cairo Column[90] refers to the Shekelesh, the Story of Wenamun refers to the Tjekker, and 13 further Egyptian sources refer to the Sherden.[91]

Byblos

The earliest ethnic group[92] later considered among the Sea Peoples is believed to be attested in Egyptian hieroglyphs on the Abishemu obelisk found in the Temple of the Obelisks at Byblos by Maurice Dunand.[93][94] The inscription mentions kwkwn son of rwqq- (or kukun son of luqq), transliterated as Kukunnis, son of Lukka, "the Lycian".[95] The date is given variously as 2000 or 1700 BCE

Ugarit

Some Sea Peoples appear in four of the Ugaritic texts, the last three of which seem to foreshadow the destruction of the city around 1180 BCE. The letters are therefore dated to the early 12th century. The last king of Ugarit was Ammurapi (c. 1191–1182 BCE), who, throughout this correspondence, is quite a young man.

- RS 34.129, the earliest letter, found on the south side of the city, from "the Great King", presumably Suppiluliuma II of the Hittites, to the prefect of the city. He says that he ordered the king of Ugarit to send him Ibnadushu for questioning, but the king was too immature to respond. He, therefore, wants the prefect to send the man, whom he promises to return. What this language implies about the relationship of the Hittite empire to Ugarit is a matter of interpretation. Ibnadushu had been kidnapped by and had resided among a people of Shikala, probably the Shekelesh, "who lived on ships". The letter is generally interpreted as an interest in military intelligence by the king.[97]

- RS L 1, RS 20.238 and RS 20.18, are a set from the Rap'anu Archive between a slightly older Ammurapi, now handling his own affairs, and Eshuwara, the grand supervisor of Alasiya. Evidently, Ammurapi had informed Eshuwara, that an enemy fleet of 20 ships had been spotted at sea. Eshuwara wrote back and inquired about the location of Ammurapi's own forces. Eshuwara also noted that he would like to know where the enemy fleet of 20 ships are now located.[98] Unfortunately for both Ugarit and Alasiya, neither kingdom was able to fend off the Sea People's onslaught, and both were ultimately destroyed. A letter by Ammurapi (RS 18.147) to the king of Alasiya—which was in fact a response to an appeal for assistance by the latter—has been found by archaeologists. In it, Ammurapi describes the desperate plight facing Ugarit.[lower-alpha 1] Ammurapi, in turn, appealed for aid from the viceroy of Carchemish, which actually survived the Sea People's onslaught; King Kuzi-Teshub I, who was the son of Talmi-Teshub—a direct contemporary of the last ruling Hittite king, Suppiluliuma II—is attested in power there,[100] running a mini-empire which stretched from "Southeast Asia Minor, North Syria ... [to] the west bend of the Euphrates"[101] from c. 1175 BCE to 990 BCE Its viceroy could only offer some words of advice for Ammurapi.[lower-alpha 2]

Hypotheses about origins

A number of hypotheses concerning the origins, identities and motives of the Sea Peoples described in the records have been formulated. They are not necessarily alternative or contradictory hypotheses about the Sea Peoples; any or all might be mainly or partly true.

Regional migration historical context

The Late Bronze Age Mycenaean Greek Linear B tablets of Pylos in the Peloponnese along the Ionian Sea demonstrate increased slave raiding and the spread of mercenaries and migratory peoples and their subsequent resettlement. Despite this, the actual identity of the Sea Peoples has remained enigmatic and modern scholars have only the scattered records of ancient civilizations and archaeological analysis to inform them. Evidence shows that the identities and motives of these peoples were known to the Egyptians. In fact, many had sought employment with the Egyptians or were in a diplomatic relationship for a few centuries before the Late Bronze Age collapse. For example, select groups, or members of groups, of the Sea People, such as the Sherden or Shardana, were used as mercenaries by Egyptian Pharaohs such as Ramesses II.

Prior to the Third Intermediate Period of Egypt (from the 15th century BCE), names of Semitic-speaking, cattle-raising pastoral nomads of the Levant appear, replacing previous Egyptian concern with the Hurrianised 'prw ('Apiru or Habiru). These were called the š3sw (Shasu), meaning "those who move on foot". e.g. the Shasu of Yhw.[103] Nancy Sandars uses the analogous name "land peoples". Contemporary Assyrian records refer to them as Ahhlamu or Wanderers.[104] They were not part of the Egyptian list of Sea Peoples, and were later referred to as Aramaeans.

Some people, such as the Lukka, were included in both categories of land and sea people.

Philistine hypothesis

The archaeological evidence from the southern coastal plain of ancient Canaan, termed Philistia in the Hebrew Bible, indicates a disruption[105] of the Canaanite culture that existed during the Late Bronze Age and its replacement (with some integration) by a culture with a possibly foreign (mainly Aegean) origin. This includes distinct pottery, which at first belongs to the Mycenaean IIIC tradition (albeit of local manufacture) and gradually transforms into uniquely Philistine pottery. Mazar says:[106]

... in Philistia, the producers of Mycenaean IIIC pottery must be identified as the Philistines. The logical conclusion, therefore, is that the Philistines were a group of Mycenaean Greeks who immigrated to the east ... Within several decades ... a new bichrome style, known as the "Philistine", appeared in Philistia ...

Sandars, however, does not take this point of view but says:[107]

... it would be less misleading to call this "Philistine pottery" "Sea Peoples" pottery or "foreign" pottery, without commitment to any particular group.

Artifacts of the Philistine culture are found at numerous sites, in particular in the excavations of the five main cities of the Philistines: the Pentapolis of Ashkelon, Ashdod, Ekron, Gath, and Gaza. Some scholars (e.g. S. Sherratt, Drews, etc.) have challenged the theory that the Philistine culture is an immigrant culture, claiming instead that they are an in situ development of the Canaanite culture, but others argue for the immigrant hypothesis; for example, T. Dothan and Barako.

Trude and Moshe Dothan suggest that the later Philistine settlements in the Levant were unoccupied for nearly 30 years between their destruction and resettlement by the Philistines, whose Helladic IIICb pottery also shows Egyptian influences.[108]

With the advent of Archaeogenetics, the Aegean hypothesis regarding the origin of the Philistines has received a major boost. A study by Michal Feldman and colleagues that carried out genomic testing of 10 Bronze Age and Iron Age individuals from Ashkelon, reported that the early Iron Age population was genetically distinct from both late Bronze Age and late Iron Age tested individuals as a result of transient European-related admixture. The authors concluded that a migration event occurred during the Bronze to Iron Age transition in Ashkelon from an Aegean-related source, even though this migration did not leave a long-lasting genetic signature.[109]

Minoan hypothesis

Two of the peoples who settled in the Levant had traditions that may connect them to Crete: the Tjeker and the Peleset. The Tjeker may have left Crete to settle in Anatolia, and left there to settle Dor.[110] According to the Old Testament,[111] the Israelite God brought the Philistines out of Caphtor. The mainstream of Biblical and classical scholarship accepts Caphtor to refer to Crete, but there are alternative minority theories.[112] Crete at the time was populated by peoples speaking many languages, among which were Mycenaean Greek and Eteocretan, the descendant of the language of the Minoans. It is possible, but by no means certain, that these two peoples spoke Eteocretan.

Recent examinations of the eruption of the Santorini volcano estimate its occurrence at between 1660 and 1613 BCE, centuries before the first appearances of the Sea Peoples in Egypt. The eruption is thus unlikely to be connected to the Sea Peoples.[113]

Greek migrational hypothesis

The identifications of Denyen with the Greek Danaans and Ekwesh with the Greek Achaeans are long-standing issues in Bronze Age scholarship, whether Greek, Hittite or Biblical, especially as they lived "in the isles". The Greek identification of the Ekwesh is considered especially problematic as this group was clearly described as circumcised by the Egyptians, and according to Manuel Robbins: "Hardly anyone thinks that the Greeks of the Bronze Age were circumcised ..."[77] Michael Wood described the hypothetical role of the Greeks (who have already been proposed as the identity of the Philistines above):[114]

... were the sea peoples ... in part actually composed of Mycenaean Greeks – rootless migrants, warrior bands and condottieri on the move ...? Certainly, there seem to be suggestive parallels between the war gear and helmets of the Greeks ... and those of the Sea Peoples ...

Wood would also include the Sherden and Shekelesh, pointing out that "there were migrations of Greek-speaking peoples to the same place [Sardinia and Sicily] at this time." He is careful to point out that the Greeks would have been only one element among many that comprised the sea peoples. Furthermore, the proportion of Greeks must have been relatively small. His major hypothesis[114] is that the Trojan War was fought against Troy VI and Troy VIIa, the candidate of Carl Blegen, and that Troy was sacked by those now identified as Greek Sea Peoples. He suggests that Odysseus' assumed identity as a wandering Cretan coming home from the Trojan War, who fights in Egypt and serves there after being captured,[115] "remembers" the campaign of Year 8 of Ramses III, described above. He points out also that places destroyed on Cyprus at the time (such as Kition) were rebuilt by a new Greek-speaking population. Several scholars have proposed that the Sea People were certainly Mycenaean Greeks.[116]

.jpg.webp)

Trojan hypothesis

The possibility that the Teresh were connected on the one hand with the Tyrrhenians,[117] believed to be an Etruscan-related culture, or on the other with Taruisa, a Hittite name possibly referring to Troy, has been speculated.[118] The Roman poet Virgil depicts Aeneas as escaping the fall of Troy by coming to Latium to found a line descending to Romulus, first king of Rome. Considering that Anatolian connections have been identified for other Sea Peoples, such as the Tjeker and the Lukka, Eberhard Zangger puts together an Anatolian hypothesis, but it is not accepted for archaeological, linguistic, anthropological and genetic reasons.[119][120][121][122] Virgil's account refers to the foundation of Rome, not to the Etruscans, and is not believed to contain true events. Furthermore, there is no archaeological or linguistic evidence of a migration in the late Bronze Age from Anatolia to Etruria,[123] and the Etruscan language, as well as all the languages of the Tyrrhenian family, considered Pre-Indo-European and Paleo-European,[124] belongs to a completely different family from the Anatolian one which is Indo-European. Moreover, both recent studies of anthropology and genetics have argued in favor of the indigenous origin of the Etruscans and against the hypothesis of eastern origin.[125][126][127]

Mycenaean warfare hypothesis

This theory suggests that the Sea Peoples were populations from the city-states of the Greek Mycenaean civilization, who destroyed each other in a disastrous series of conflicts lasting several decades. There would have been few or no external invaders and just a few excursions outside the Greek-speaking part of the Aegean civilization.

Archaeological evidence indicates that many fortified sites of the Greek domain were destroyed in the late 13th and early 12th century BCE, which was understood in the mid-20th century to have been simultaneous or nearly so and was attributed to the Dorian invasion championed by Carl Blegen of the University of Cincinnati. He believed Mycenaean Pylos was burned during an amphibious raid by warriors from the north (Dorians).

Subsequent critical analysis focused on the fact that the destructions were not simultaneous and that all the evidence of Dorians comes from later times. John Chadwick championed a Sea Peoples hypothesis,[128] which asserted that, since the Pylians had retreated to the northeast, the attack must have come from the southwest, the Sea Peoples being, in his view, the most likely candidates. He suggests that they were based in Anatolia and, although doubting that the Mycenaeans would have called themselves "Achaeans", speculates that "it is very tempting to bring them into connexion." He does not assign a Greek identity to all of the Sea Peoples.

Considering the turbulence between and within the great families of the Mycenaean city-states in Greek mythology, the hypothesis that the Mycenaeans destroyed themselves is long-standing[129] and finds support by the ancient Greek historian Thucydides, who theorized:

For in early times the Hellenes and the barbarians of the coast and islands ... was tempted to turn to piracy, under the conduct of their most powerful men ... [T]hey would fall upon a town unprotected by walls ... and would plunder it ... no disgrace being yet attached to such an achievement, but even some glory.[130]

Although some advocates of the Philistine or Greek migration hypotheses identify all the Mycenaeans or Sea Peoples as ethnically Greek, John Chadwick (founder, with Michael Ventris, of Linear B studies) adopts instead the multiple ethnicity view.

Nuragic and Italian peoples hypotheses

Some archeologists believe that the Sherden are identifiable with the Sardinians from the Nuragic era.[48][131][132][133]

Theories of the possible connections between the Sherden to Sardinia, Shekelesh to Sicily, and Teresh to Tyrrhenians, even though long-standing, are based on onomastic similarities.[134] Nuragic pottery of domestic use has been found at Pyla Kokkinokremos, a fortified settlement in Cyprus, during the 2010 and 2017 excavations.[135][136][137][138][139] The site is dated to the period between the 13th and 12th centuries BCE, that of the Sea Peoples' invasions. This find has led archaeologist Vassos Karageorghis to identify the Nuragic Sardinians with the Sherden, one of the Sea Peoples. According to him, the Sherden went first to Crete and from there they joined the Cretans in an eastward expedition to Cyprus.[140][141]

The Nuragic bronze statuettes, a great collection of Nuragic sculptures, includes a great number of horned helmet warriors wearing a similar skirt to the Sherdens' and a round shield; although they had been dated for a long time to the 10th or 9th century BCE, recent discoveries suggest that their production started around the 13th century BCE. Swords identical to those of the Sherden have been found in Sardinia, dating back to 1650 BCE

The self-name of the Etruscans, Rasna, does not lend itself to the Tyrrhenian derivation, although it has been suggested that this was itself derived from an earlier form T'Rasna. The Etruscan civilization has been studied, and the language partly deciphered. It has variants and representatives in Aegean inscriptions, but these may well be from travelers or colonists of Etruscans during their seafaring period before Rome destroyed their power.[142]

There is no definitive archaeological evidence. About all that can be said for certain is that Mycenaean IIIC pottery was widespread around the Mediterranean in areas associated with Sea Peoples and its introduction at various places is often associated with cultural change, violent or gradual. An old theory is that the Sherden and Shekelesh brought those names with them to Sardinia and Sicily, "perhaps not operating from those great islands but moving toward them",[143] and this is still accepted by Eric Cline[144] and by Trevor Bryce,[145] who explains that some of the Sea Peoples sprang out of the collapsing Hittite empire. Giovanni Ugas believes that the Sherden originated in Sardinia,[131] and his studies have been echoed by Sebastiano Tusa, in his last book,[132] and by Carlos Roberto Zorea, from the Complutense University of Madrid.[133]

Anatolian famine hypothesis

A famous passage from Herodotus[146] portrays the wandering and migration of Lydians from Anatolia because of famine:[147]

In the days of Atys, the son of Manes, there was great scarcity through the whole land of Lydia ... So the king determined to divide the nation in half ... the one to stay, the other to leave the land. ... the emigrants should have his son Tyrrhenus for their leader ... they went down to Smyrna, and built themselves ships ... after sailing past many countries they came to Umbria ... and called themselves ... Tyrrhenians.

However, the 1st-century BC historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus, a Greek living in Rome, dismissed many of the ancient theories of other Greek historians and postulated that the Etruscans were indigenous people who had always lived in Etruria and were different from the Lydians.[148] Dionysius noted that the 5th-century historian Xanthus of Lydia, who was originally from Sardis and was regarded as an important source and authority for the history of Lydia, never suggested a Lydian origin of the Etruscans and never named Tyrrhenus as a ruler of the Lydians.[148]

For this reason, therefore, I am persuaded that the Pelasgians are a different people from the Tyrrhenians. And I do not believe, either, that the Tyrrhenians were a colony of the Lydians; for they do not use the same language as the latter, nor can it be alleged that, though they no longer speak a similar tongue, they still retain some other indications of their mother country. For they neither worship the same gods as the Lydians nor make use of similar laws or institutions, but in these very respects they differ more from the Lydians than from the Pelasgians. Indeed, those probably come nearest to the truth who declare that the nation migrated from nowhere else, but was native to the country, since it is found to be a very ancient nation and to agree with no other either in its language or in its manner of living.

Tablet RS 18.38 from Ugarit also mentions grain to the Hittites, suggesting a long period of famine, connected further, in the full theory, to drought.[149] Barry Weiss,[150] using the Palmer Drought Index for 35 Greek, Turkish, and Middle Eastern weather stations, showed that a drought of the kinds that persisted from January 1972 would have affected all of the sites associated with the Late Bronze Age collapse. Drought could have easily precipitated or hastened socio-economic problems and led to wars. More recently, Brian Fagan has shown how mid-winter storms from the Atlantic were diverted to travel north of the Pyrenees and the Alps, bringing wetter conditions to Central Europe, but drought to the Eastern Mediterranean.[151] More recent paleoclimatological research has also shown climatic disruption and increasing aridity in the Eastern Mediterranean, associated with the North Atlantic Oscillation at this time (See Bronze Age Collapse).

Invader hypothesis

The term "invasion" is used generally in the literature concerning the period to mean the documented attacks, implying that the aggressors were external to the eastern Mediterranean, though often hypothesized to be from the wider Aegean world. An origin outside the Aegean also has been proposed, as in this example by Michael Grant: "There was a gigantic series of migratory waves, extending all the way from the Danube valley to the plains of China."[152]

Such a comprehensive movement is associated with more than one people or culture; instead, it was a "disturbance", according to Finley:[153]

A large-scale movement of people is indicated ... the original center of disturbance was in the Carpatho-Danubian region of Europe. ... It appears ... to have been ... pushing in different directions at different times.

If different times are allowed on the Danube, they are not in the Aegean: "all this destruction must be dated to the same period about 1200 [BCE]."[153]

The movements of the hypothetical Dorian Invasion, the attacks of the Sea Peoples, the formation of Philistine kingdoms in the Levant and the fall of the Hittite Empire were associated and compressed by Finley into the 1200 BCE window.

Robert Drews presents a map showing the destruction sites of 47 fortified major settlements, which he terms "Major Sites Destroyed in the Catastrophe".[154] They are concentrated in the Levant, with some in Greece and Anatolia.

See also

- Beder (ancient ruler)

- Hyksos

- Meryey

- Thalassocracy

References

Citations

- Killebrew 2013, p. 2. Quote: "First coined in 1881 by the French Egyptologist G. Maspero (1896), the somewhat misleading term 'Sea Peoples' encompasses the ethnonyms Lukka, Sherden, Shekelesh, Teresh, Eqwesh, Denyen, Sikil / Tjekker, Weshesh, and Peleset (Philistines). [Footnote: The modern term 'Sea Peoples' refers to peoples that appear in several New Kingdom Egyptian texts as originating from 'islands' (tables 1–2; Adams and Cohen, this volume; see, e.g., Drews 1993, 57 for a summary). The use of quotation marks in association with the term 'Sea Peoples' in our title is intended to draw attention to the problematic nature of this commonly used term. It is noteworthy that the designation 'of the sea' appears only in relation to the Sherden, Shekelesh and Eqwesh. Subsequently, this term was applied somewhat indiscriminately to several additional ethnonyms, including the Philistines, who are portrayed in their earliest appearance as invaders from the north during the reigns of Merenptah and Ramesses Ill (see, e.g., Sandars 1978; Redford 1992, 243, n. 14; for a recent review of the primary and secondary literature, see Woudhuizen 2006). Henceforth the term Sea Peoples will appear without quotation marks.]"

- Drews 1995, pp. 48–61: "The thesis that a great 'migration of the Sea Peoples' occurred ca. 1200 B.C. is supposedly based on Egyptian inscriptions, one from the reign of Merneptah and another from the reign of Ramesses III. Yet in the inscriptions themselves, such a migration nowhere appears. After reviewing what the Egyptian texts have to say about 'the sea peoples', one Egyptologist (Wolfgang Helck) recently remarked that although some things are unclear, 'eins ist aber sicher: Nach den ägyptischen Texten haben wir es nicht mit einer "Völkerwanderung" zu tun' ['One thing is however certain: according to the Egyptian texts we are not dealing with a "migration"'] Thus the migration hypothesis is based not on the inscriptions themselves but on their interpretation".

- Müller 1888, p. 147: "In Egyptian history, there is hardly any incident of so great an interest as the invasion of Egypt by the Mediterranean peoples, the facts of which are connected with the most important questions of ethnography and the primitive history of classic nations."

- Hall 1922.

- "Syria: Early history". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- "Sea People". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- Silberman 1998, p. 269.

- de Rougé 1855, p. 14: [Translation from the French]: "For a long time Kefa has been identified, with verisimilitude, with Caphthorim of the Bible, to whom Gesenius, along with most interpreters, assigns as a residence the islands of Crete or Cyprus. The people of Cyprus had certainly to take sides in this war; perhaps they were then the allies of Egypt. In any case, our entry does not detail the names of these people, from the islands of the Mediterranean. Champollion noted that T'akkari [which he names Fekkaros; see appendix at the following entry] and Schartana, were recognizable, in enemy ships, with unique hairstyles. In addition, in the crests of the conquered peoples, the Schartana and the Touirasch bear the designation of the peoples of the sea. It is therefore likely that they belong to these nations from islands or coasts of the archipelago. The Rabou are still recognizable among the prisoners."

- Drews 1992: "In fact, this migration of the Sea Peoples is not to be found in Egyptian inscriptions, but was launched by Gaston Maspero in 1873 [footnote: In the Revue Critique d'Histoire et de Littérature 1873, pp. 85–86]. Although Maspero's proposal initially seemed unlikely, it gained credibility with the publication of the Lemnos stele. In 1895, in his popular Histoire ancienne des peuples de l'orient classique [footnote; Vol. II (Paris:1895), translated into English as The Struggle of the Nations (ed. A. H. Sayce, tr. M. L. McClure, New York: 1896)], Maspero fully elaborated his scenario of "the migration of the Sea Peoples". Adopted by Eduard Meyer for the second edition of his Geschichted es Altertums, the theory won general acceptance among Egyptologists and orientalists."

- Silberman 1998, p. 272: "As E. S. Sherratt has pointed out in an enlightening study of the interplay of ideology and literary strata in the formation of the Homeric epics (1990), phases of active narrative or descriptive invention closely correspond to periods of rapid social and political change. Sherratt notes that one of the characteristic manifestations of this process – in which emerging elites seek to legitimate their power – is 'the transformation of an existing oral epic tradition in order to dress it in more recognizably modern garb' (1990: 821). Can we not see in the history of the archaeology of the Sea Peoples a similar process of literary reformulation, in which old components are reinterpreted and reassembled to tell a new tale? Narrative presupposes that both storyteller and audience share a single perspective, and therein may lie the connection between the intellectual and ideological dimensions of archaeology. To generalize beyond specific, highly localized data, archaeologists must utilize familiar conceptual frameworks and it is from the political and social ideologies of every generation that larger speculations about the historical role of the Sea Peoples have always been drawn. As many papers in this conference have suggested, traditional interpretive structures are in the process of reconsideration and renovation. That is why I believe it essential that we reflect on our current Sea Peoples stories – and see if we cannot detect the subtle yet lingering impact upon them of some timeworn Victorian narratives."

- Vandersleyen 1985, p. 53: "However, of the nine peoples concerned by these wars, only four were actually defined as coming 'from w3d-wr' or 'from p3 ym'. Furthermore, these expressions seem to be linked more often to vegetation and sweet water than to seawater, and it seems clear that the term "Sea Peoples" has to be abandoned. Some will object to this, basing themselves on the expression iww hryw-ib w3d-wr, usually translated by 'islands situated in the middle of the sea', where some of the Sea Peoples are said to have come from. Indeed. it is this expression that supported the persistent idea that the 'Sea Peoples' came from the Aegean islands or at least from an East Mediterranean island. Now, these terms are misleading, not only because w3d-wr and p3 ym, quite likely, do not designate 'the sea' here, but also because the term in itself does not always mean 'island'; it can also be used to indicate other kinds of territories not necessarily maritime ones. The argument based on these alleged 'sea islands' is thus groundless ... To conclude, the Philistines came neither from Crete nor from the Aegean islands or coasts, but probably from the southern coast of Asia Minor or from Syria."

- Cline, Eric. "Ask a Near East Professional: Who are the Sea Peoples and what role did they play in the devastation of civilizations?". asorblog.org. American Schools of Oriental Research. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

The simple answer is that there is no simple answer. It remains an archaeological mystery that is the subject of much debate even today, more than 150 years after the discussions first began.

- "Who Were the Sea People?", Eberhard Zangger, pp. 20–31 of the May/June 1995 print edition of Saudi Aramco World: "very few—if any—archeologists would consider the Sea People to have been identified."

- See also the sketches provided later in Champollion, Monuments: from the left side of the Second Pylon: Plate CCVIII, and from the base of the right-hand side of the Fortified East Gate Plate CCIII.

- Compare with the hieroglyphs provided by Woudhuizen 2006, p. 36.

- de Rougé 1855.

- de Rougé 1855, p. 1.

- Greene 1855, p. 4: [Translation from the French]: "The notices and the 17th letter of Champollion provide a complete and faithful summary of the campaigns of Ramses III (his Ramses Ammon), especially that represented on the north wall, containing the famous bas-relief of a naval battle where the enemy ships are driven to shore by the Egyptian fleet, and simultaneously crushed by the army, which the press on the other side. Champollion recognized that among the enemies of Ramesses, there were a new people, belonging to the white race, and designated as the Tamhou. He copied the first line of the large inscription of the pylon, with a date he specified in the ninth year of the reign, and he noted the importance of this text, which contains several names of people. ... After receiving this just tribute of praise, the King finally begins his speech to the thirteenth line. It recommends to all his subjects to pay attention to his words, and shows their feelings that must lead them in life; then he boasts of his exploits, he brings glory to his father, the god Ammon, who gave him all the conquests. After a column header which unfortunately suffered a lot, is one of the most important parts of our text, in which the king lists the enemies he has overcome, beginning with the Cheta, the Ati, the Karkamasch the Aratou, the Arasa; then, after a short break: at their camp in the country of Amaour, I destroyed the people and their country as if they had never existed We see that these different peoples, common enemies of Egypt in their Asian campaigns before those of Ramses III, are gathered in one group. In the next column, we find a second group formed of people considered by Champollion to have played an important role in the campaign with the naval combat ships; it is the Poursata, the Takkara, the Shakarsha, the Taamou, and Ouaschascha. We see that the only missing Sharetana to this list."

- Greene's documentary photographs are held at the Musee d'Orsay, for example: Médinet-Habou, Temple funéraire de Ramsès III, muraille du nord (5); inventory number: PHO 1986 131 40.

- de Rougé 1867.

- Vandersleyen 1985, p. 41 n.10.

- Maspero 1896, p. 461–470.

- Silberman 1998, p. 270: "The English translation of Maspero's résumé of ethnic movement entitled The Struggle of the Nations (Maspero 1896) must surely have evoked meaningful associations at a time when competition for territory and economic advantage among European Powers was at a fever pitch (Hobsbawm 1987)."

- Killebrew 2013, pp. 2–5.

- Killebrew 2013, p. 2a.

- A convenient table of Sea Peoples in hieroglyphics, transliteration and English is given in Woudhuizen 2006, who developed it from works of Kitchen cited there

- Breasted (1906), Vol IV, §403 / p.201: "in their isles" and "of the sea"

- Woudhuizen 2006, p. 35

- Kelder 2010, p. 126.

- Heike Sternberg-el Hotabi (2012). "Flüchtlinge aus Nord, West oder Ost? Die Seevölker und ihre Heimat". Der Kampf der Seevölker gegen Pharao Ramses III (2 ed.). Rahden: Marie Leidorf. p. 37. ISBN 978-3-86757-532-4.

- Siemer, Eckhard (2019). "Der Friedensvertrag von 1258 v. Chr. und die Ehe der Naptera". Der hethitisch- mykenische Zinnhandel in Europa und der Untergang ihrer Reiche (1430 - 1130 BC) sowie : Vincent von Beauvais De plumbo. p. 228. ISBN 978-3-98 13693-3-5.

- Livingstone, David (2002). "The Dorian Invasion". The Dying God: The Hidden History of Western Civilization. p. 72. ISBN 9780595231997.

- Les nuits attiques. Aulus Gellius, René Marache. Les Belles lettres, 1991. p. 39

- Breasted (1906), Vol III, §588 / p.248 and §601 / p.255: "of the countries of the sea". Breasted wrote in a footnote regarding this designation "It is noticeable that this designation, both here and in the Athribis Stela (1. 13), is inserted only after the Ekwesh. In the Athribis Stela Ekwesh is cut off by a numeral from the preceding, showing that the designation there belongs only to them."

- Drews 1995, p. 54: "Already in the 1840s Egyptologists had debated the identity of the 'northerners, coming from all lands', who assisted the Libyan King Meryre in his attack upon Merneptah. Some scholars believed that Meryre's auxiliaries were merely his neighbors on the Libyan coast, while others identified them as Indo-Europeans from north of the Caucasus. It was one of Maspero's most illustrious predecessors, Emmanuel de Rougé, who proposed that the names reflected the lands of the northern Mediterranean: the Lukka, Ekwesh, Tursha, Shekelesh, and Shardana were men from Lydia, Achaea, Tyrsenia (western Italy), Sicily, and Sardinia." De Rougé and others regarded "Meryre's auxiliaries-these 'peoples de la mer Méditerranée' – as mercenary bands, since the Sardinians, at least, were known to have served as mercenaries already in the early years of Ramesses the Great. Thus the only 'migration' that the Karnak Inscription seemed to suggest was an attempted encroachment by Libyans upon neighboring territory."

- Drews 1995, p. 49.

- Hincks, Edward (1846). "An Attempt to Ascertain the Number, Names, and Powers, of the Letters of the Hieroglyphic, or Ancient Egyptian Alphabet; Grounded on the Establishment of a New Principle in the Use of Phonetic Characters". The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy. 21 (21): 176. JSTOR 30079013.

- Osburn, William (1846). Ancient Egypt, Her Testimony to the Truth of the Bible. Samuel Bagster and sons. p. 107.

- Vandersleyen 1985, pp. 40–41 n.9: [Original French]: "À ma connaissance, les plus anciens savants qui ont proposé explicitement l' identification des Pourousta avec les Philistins sont William Osburn Jr., Ancient Egypt, Her Testimony to the Truth of the Bible..., Londres 1846. p. 99. 107. 137. et Edward Hincks, An Attempt to Ascertain the Number, Names, and Powers, of the Letters of the Hieroglyphic or Ancient Egyptian Alphabet, Dublin, 1847, p.47"

[Translation]: "To my knowledge, the earliest scholars who explicitly proposed the identification of Pourousta with the Philistines are William Osburn Jr., Ancient Egypt, Her Testimony to the Truth of the Bible ..., London, 1846. p.99. 107. 137. and Edward Hincks, An Attempt to Ascertain the Number, Names, and Powers, of the Letters of the Alphabet Egyptian Hieroglyphic gold Ancient , Dublin, 1847, p.47" - Vandersleyen 1985, pp. 39–41: [original French]: "Quand Champollion visita Médinet Habou en juin 1829, il vit ces scénes, lut le nom des Pourosato, sans y reconnaître les Philistins; plus tard, dans son Dictionnaire égyptien et dans sa Grammaire égyptienne, il transcrivit le même nom Polosté ou Pholosté, mais contrairement à ce qu’affirmait Brugsch en 1858 et tous les auteurs postérieurs, Champollion n’a nulle part écrit que ces Pholosté étaient les Philistins de la Bible."

[Translation]: "When Champollion visited Medinet Habu in June 1829, he experienced these scenes, reading the name of Pourosato, without recognizing the Philistines; Later, in his Dictionnaire égyptien and its Grammaire égyptienne, he transcribed the same name Polosté or Pholosté, but contrary to the assertion by Brugsch in 1858 and subsequent authors, Champollion has nowhere written that these Pholosté were the Philistines of the Bible."

Dothan and Dothan wrote of the initial identification (Dothan 1992, pp. 22–23): "It was not, however, until the spring of 1829, almost a year after they had arrived in Egypt, that Champollion and his entourage were finally ready to tackle the antiquities of Thebes ... The chaotic tangle of ships and sailors, which Denon assumed was a panicked flight into the Indus, was actually a detailed portrayal of a battle at the mouth of the Nile. Because the events of the reign of Ramesses III were unknown from others, the context of this particular war remained a mystery. On his return to Paris, Champollion puzzled over the identity of the various enemies shown in the scene. Since each of them had been carefully labeled with a hieroglyphic inscription, he hoped to match the names with those of ancient tribes and peoples mentioned in Greek and Hebrew texts. Unfortunately, Champollion died in 1832 before he could complete the work, but he did have success with one of the names. ... proved to be none other than the biblical Philistines". Dothan and Dothan's description was incorrect in stating that the naval battle scene (Champollion, Monuments, Plate CCXXII) "carefully labeled with a hieroglyphic inscription" each of the combatants, and Champollion's posthumously published manuscript notes contained only one short paragraph on the naval scene with only the "Fekkaro" and "Schaïratana" identified (Champollion, Monuments, page 368). Dothan and Dothan's following paragraph "Dr. Greene's Unexpected Discovery" incorrectly confused John Beasley Greene with John Baker Stafford Greene. Champollion did not make a connection to the Philistines in his published work, and Greene did not refer to such a connection in his 1855 work which commented on Champollion (Greene 1855, p. 4). - O'Connor & Cline 2003, p. 116.

- Bryce, Trevor (15 March 2012). The World of The Neo-Hittite Kingdoms: A Political and Military History. p. 128. ISBN 9780199218721. OUP Oxford, 2012

- Gardiner 1947, p. 196 (Vol. 1), in his commentary on the Onomasticon of Amenope, No. 268, "Srdn", wrote:

"The records of Meneptah are much more explicit: the great Karnak inscription described how the Ekwesh, Tursha, Lukki, Sherden and Sheklesh (L.1) had been incited against Egypt by the prince of the Libu (Libyans); in L.52 the Sherden, Sheklesh and Ekwesh are collectively described as

(var.

![X1 [t]](../I/hiero_X1.png.webp)

)

'the foreign lands (var. 'foreigners') of the sea'"

Note: Gardiner's reference to the alternative ("var.") writing 'foreigners' referred to Gustave Lefebvre's "Stèle de l'an V de Méneptah", ASAE 27, 1927, p.23, line 13, describing the Athribis Stele. - "Chronology and Terminology", in "The Prehistoric Archaeology of the Aegean" accessed May 23, 2006

- Heike Sternberg-el Hotabi (2012). "Flüchtlinge aus Nord, West oder Ost? Die Seevölker und ihre Heimat". Der Kampf der Seevölker gegen Pharao Ramses III (2 ed.). Rahden: Marie Leidorf. p. 38. ISBN 978-3-86757-532-4.

- Breasted (1906), Vol IV, §129 / p.75: "of the sea"

- O'Connor & Cline 2003, p. 112-113.

- S. Bar; D. Kahn; J.J. Shirley (9 June 2011). Egypt, Canaan and Israel: History, Imperialism, Ideology and Literature: Proceedings of a Conference at the University of Haifa, 3–7 May 2009. Brill. pp. 350 ff. ISBN 978-90-04-19493-9.

- O'Connor & Cline 2003, p. 113.

- Korfmann, Manfred O. (2007). Winkler, Martin M (ed.). Troy: From Homer's Iliad to Hollywood Epic. Oxford, England: Blackwell Publishing Limited. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-4051-3183-4.

Troy or Ilios (or Wilios) is most probably identical with Wilusa or Truwisa ... mentioned in the Hittite sources

- Geoffrey W. Bromiley (1988). Lemma "Tiras", in The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. William B. Eerdmands Publishing Comoany. p. 859. ISBN 0-8028-3784-0. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- O'Connor & Cline 2003, p. 114.

- James Baikie mentioned it on pp. 166, 187 of his book The Sea-Kings of Crete, 2nd edition (Adam and Charles Black, London, 1913)

- Rainer Hannig (2006). Die Sprache der Pharaonen - Großes Handwörterbuch Ägyptisch-Deutsch: (2800 - 950 v. Chr.). Philipp von Zabern. p. 1039. ISBN 3-8053-1771-9.

- Heike Sternberg-el Hotabi (2012). "Flüchtlinge aus Nord, West oder Ost? Die Seevölker und ihre Heimat". Der Kampf der Seevölker gegen Pharao Ramses III (2 ed.). Rahden: Marie Leidorf. p. 49. ISBN 978-3-86757-532-4.

- Lipiński, Edward (2006). On the Skirts of Canaan in the Iron Age: Historical and Topographical Researches. Peeters Publishers. p. 96. ISBN 978-90-429-1798-9. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- Manfred Weippert (2010). Historisches Textbuch zum Alten Testament. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 202–209. ISBN 9783525516935. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- Heike Sternberg-el Hotabi (2012). "Flüchtlinge aus Nord, West oder Ost? Die Seevölker und ihre Heimat". Der Kampf der Seevölker gegen Pharao Ramses III (2 ed.). Rahden: Marie Leidorf. pp. 38, 41. ISBN 978-3-86757-532-4.

- Strobel, August (2015). Der spätbronzezeitliche Seevölkersturm: Ein Forschungsüberblick mit Folgerungen zur biblischen Exodusthematik. Walter de Gruyter. p. 208. ISBN 9783110855036.

Der Name Wešeš gilt allgemein als dunkel. (...) R. A. Macalister äußerte die Vermutung, es könnte sich um die Vorgänger der indogermanischen Osker handeln, (...)

- Yigael Yadin And Dan, Why Did He Remain in Ships

- N. K. Sandars, The Sea Peoples. Warriors of the ancient Mediterranean, 1250–1150 BC. Thames & Hudson, 1978

- Herda, Alexander (2009). Die Karer und die Anderen. Frank Rumscheid. p. 57. ISBN 9783774936324.

- Oren 2000, p. 85: "Thus far, rather meager documentation is available. What I shall do for the remainder of this essay is to focus on what is in fact our primary source on the Sea Peoples, the basis of virtually all significant discussions of them, including many efforts to identify the Sea Peoples with archaeologically known cultures or groups in the Mediterranean and beyond. This source is the corpus of scenes and texts relevant to the Sea Peoples displayed on the walls of the mortuary temple of Ramesses III at western Thebes. Although it has been much discussed, this corpus has often led scholars to different and contradictory conclusions, and will always probably be subject to debate because of certain ambiguities inherent in the material."

- Uncertainty of the dates is not a case of no evidence but of selecting among several possible dates. The articles in Wikipedia on related topics use one set of dates by convention but these and all dates based on them are not the only possible. A summary of the date question is given in Hasel, Ch. 2, p. 151, which is available as a summary at Google Books.

- Find this and other documents quoted in the Shardana Archived 13 March 2008 at archive.today article by Megaera Lorenz at the Penn State site. This is an earlier version of her article, which gives a quote from Kitchen not found in the External Links site below. Breasted Volume III, Article 491, p.210, which can be found on Google books, gives quite a different translation of the passage. Unfortunately, large parts of the text are missing and must be restored, but both versions agree on the Sherden and the warships.

- Kenneth Kitchen, Pharaoh Triumphant: The Life and Times of Ramesses II, King of Egypt, Aris & Phillips, 1982. pp.40–41

- Grimal, pp. 250–253

- The poem appears in inscriptional form but the scribe, pntAwr.t, was not the author, who remains unknown. The scribe copied the poem onto Papyrus in the time of Merneptah and copies of that found their way into Papyrus Sallier III currently located in the British Museum. The details are stated in "The Battle of Kadesh". Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) on the site of the American Research Center in Egypt of Northern California. Both the inscription and the poem are published in "Egyptian Accounts of the Battle of Kadesh". Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 3 May 2008.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) on the Pharaonic Egypt site. - J. von Beckerath, p.190. Like those of Ramses II, these dates are not certain. Von Beckerath's dates, adopted by Wikipedia, are relatively late; for example, Sanders, Ch. 5, p. 105, sets the Battle of Perire at April 15, 1220.

- The Great Karnak Inscription.

- All three inscriptions are stated in Breasted, Vol. 3, "Reign of Meneptah", pp. 238 ff., Articles 569 ff.

- Breasted, volume 3, §595, page 252

- Maspero 1881, p. 118.

- Breasted, volume 3, page 253.

- Breasted, Vol. 3, pg. 256–264.

- J. H. Breasted, p. 243, citing Lines 13–15 of the inscription

- Robbins, Manuel (2001). Collapse of the Bronze Age : the story of Greece, Troy, Israel, Egypt, and the peoples of the sea. San Jose Calif: Authors Choice Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-595-13664-3.

- Translation by Egerton and Wilson, 1936, plates 37–39, lines 8–23. Also found in Breasted, 1906, volume 4, p. 44, §75

- Oren 2000, p. 86: "One consists of a string of large scale scenes, complemented with relatively brief texts, extending in a narrative sequence along part of the north facade of the temple, which it shares with part of a similar narrative treatment of Ramesses III's Year 5 campaign against the Libyans. This latter sequence originates however on the west or rear wall of the temple. The other, physically quite separate composition relating to the Sea Peoples is displayed across the external (eastern) face of the great pylon which separates the first court of the temple from the second. On the pylon's southern wing is a large-scale scene – occupying most of the facade – showing Ramesses III leading three lines of captive Sea Peoples to Amun-Re, lord of Thebes (and of the empire), and his consort Mut. Displayed on the equivalent space of the north wing is a long text, without pictorial embellishment, which is a verbal statement by Ramesses III describing at length his victory over the Sea Peoples, and the extraordinary beneficence of Amun-Re thus displayed, to 'the entire land gathered together'. In fact, this apparent simplicity – two separate and somewhat different compositions relevant to the Sea Peoples-belies the actual complexity of the compositional relationship between the two Sea Peoples compositions on the one hand, and their joint relationship to the entire compositional scheme or 'program' of the entire temple on the other. Any effort to understand the historical significance of the Sea Peoples' records at Medinet Habu must take this compositional dimension into account, as well as the conceptual dimensional, the relationship of the general composition scheme or program to the functions and meanings of the temple, as understood by the Egyptians."

- Beckman cites the first few lines of the inscription located on the NW panel of the 1st court of the temple. This extensive inscription is stated in full in English in the Woudhuizen 2006, pp. 43–56, which also contains a diagram of the locations of the many inscriptions pertaining to the reign of Ramses III on the walls of the temple at Medinet Habu.

- Bryce, p.371

- Breasted, 1906, volume 4, p.48, §81

- Translation by John A. Wilson in Pritchard, J.B. (ed.) Ancient Near Eastern Texts relating to the Old Testament, 3rd edition, Princeton 1969, p. 262. Also found in Breasted, 1906, volume 4, p. 37, §64

- Woudhuizen 2006, pp. 43–56 quotes the inscriptions in English.

- This passage in the papyrus is often cited as evidence that the Egyptians settled the Philistines in Philistia. The passage however only mentions the Sherden and Weshesh; i.e. does not mention the Peleset and Tjeker, and nowhere implies that the scribe meant Egyptian possessions in the Levant.

- Bernard Bruyère, Mert Seger à Deir el Médineh, 1929, pages 32–37

- Redford, P. 292. A number of copies or partial copies exist, the best being the Golenischeff Papyrus, or Papyrus Moscow 169, located in the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow (refer to Onomasticon of Amenemipet at the Archaeowiki site). In it the author is stated to be Amenemope, son of Amenemope.

- Letter EA 81

- Lorenz, Megaera. "The Amarna Letters". Penn State site. Archived from the original on 6 June 2007. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- Breasted (1906), Vol III, §593 / p.252: "in their isles" and "of the sea"

- Per Killebrew 2013, pp 2–5, these are: Stele of Padjesef, Tanis Stele, Papyrus Anastasi I, Papyrus Anastasi II, Stele of Setemhebu, Papyrus Amiens, Papyrus Wilbour, Adoption Papyrus, Papyrus Moscow 169, Papyrus BM 10326, Papyrus Turin 2026, Papyrus BM 10375, Donation Stele

- See also Woudhuizen 2006, particularly his Concluding Remarks on pages 117–121, for a fuller consideration of the meaning of ethnicity.

- Maurice Dunand, Foilles de Byblos, volume 2, p. 878, no. 16980

- William F. Albright, "Dunand's New Byblos Volume: A Lycian at the Byblian Court," BASOR 155, 1959, pp. 31-34

- Bryce, T. R. (1974). "The Lukka Problem – And a Possible Solution". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 33 (4): 395–404. doi:10.1086/372378. JSTOR 544776. S2CID 161428632. The inscription is mentioned as well in Woudhuizen 2006, p. 31.

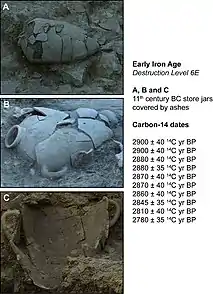

- Bretschneider, Joachim; Otto, Thierry (8 June 2011). "The Sea Peoples, from Cuneiform Tablets to Carbon Dating". PLOS ONE. 6 (6): e20232. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...620232K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020232. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3110627. PMID 21687714.

- The texts of the letters are transliterated and translated in Woudhuizen 2006, pp. 43–56 and also are mentioned and hypotheses are given about them in Sandars, p. 142 following.

- The sequence, only recently completed, appears in Woudhuizen 2006, pp. 43–56, along with the news that the famous oven, still reported at many sites and in many books, in which the second letter was hypothetically being baked at the destruction of the city, was not an oven, the city was not destroyed at that time, and a third letter existed.

- Jean Nougaryol et al. (1968) Ugaritica V: 87–90 no. 24

- Kitchen, pp. 99 & 140

- Kitchen, pp.99–100

- RSL I = Nougayril et al., (1968) 86–86, no.23

- Rainey, Anson (November 2008). "Shasu or Habiru. Who Were the Early Israelites?". Biblical Archaeology Review. 34 (6 (November/December)).

- Page 53

- Reford p. 292

- Ch. 8, a subsection entitled "The Initial Settlement of the Sea Peoples".

- Ch. 7

- Dothan 1992.

- Feldman, Michal; Master, Daniel M.; Bianco, Raffaela A.; Burri, Marta; Stockhammer, Philipp W.; Mittnik, Alissa; Aja, Adam J.; Jeong, Choongwon; Krause, Johannes (2019). "Ancient DNA sheds light on the genetic origins of early Iron Age Philistines". Science Advances. 5 (7): eaax0061. Bibcode:2019SciA....5...61F. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aax0061. PMC 6609216. PMID 31281897.

- See under Tjeker.

- Amos 9,7; argument reviewed by Sandars in Ch. 7.

- One is cited under Caphtor.

- "New Evidence Suggests The Need To Rewrite Bronze Age History". Sciencedaily.com. 29 April 2006. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- Ch. 7, "The Peoples of the Sea."

- Odyssey XIV 191–298.

- John Noble Wilford (29 September 1992). "Philistines Were Cultured After All, Say Archeologists". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

I am willing to state flatly that the Sea Peoples, including the Philistines, were Mycenaean Greeks

- Sandars Ch. 5.

- Wood Ch. 6.

- Barker, Graeme; Rasmussen, Tom (2000). The Etruscans. The Peoples of Europe. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-631-22038-1.

- Turfa, Jean MacIntosh (2017). "The Etruscans". In Farney, Gary D.; Bradley, Gary (eds.). The Peoples of Ancient Italy. Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 637–672. doi:10.1515/9781614513001. ISBN 978-1-61451-520-3.

- De Grummond, Nancy T. (2014). "Ethnicity and the Etruscans". In McInerney, Jeremy (ed.). A Companion to Ethnicity in the Ancient Mediterranean. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 405–422. doi:10.1002/9781118834312. ISBN 9781444337341.

- Shipley, Lucy (2017). "Where is home?". The Etruscans: Lost Civilizations. London: Reaktion Books. pp. 28–46. ISBN 9781780238623.

- Wallace, Rex E. (2010). "Italy, Languages of". In Gagarin, Michael (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 97–102. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195170726.001.0001. ISBN 9780195170726.

Etruscan origins lie in the distant past. Despite the claim by Herodotus, who wrote that Etruscans migrated to Italy from Lydia in the eastern Mediterranean, there is no material or linguistic evidence to support this. Etruscan material culture developed in an unbroken chain from Bronze Age antecedents. As for linguistic relationships, Lydian is an Indo-European language. Lemnian, which is attested by a few inscriptions discovered near Kamania on the island of Lemnos, was a dialect of Etruscan introduced to the island by commercial adventurers. Linguistic similarities connecting Etruscan with Raetic, a language spoken in the sub-Alpine regions of northeastern Italy, further militate against the idea of eastern origins.

- Haarmann, Harald (2014). "Ethnicity and Language in the Ancient Mediterranean". In McInerney, Jeremy (ed.). A Companion to Ethnicity in the Ancient Mediterranean. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 17–33. doi:10.1002/9781118834312.ch2. ISBN 9781444337341.

- Ghirotto, Silvia; Tassi, Francesca; Fumagalli, Erica; Colonna, Vincenza; Sandionigi, Anna; Lari, Martina; Vai, Stefania; Petiti, Emmanuele; Corti, Giorgio; Rizzi, Ermanno; De Bellis, Gianluca; Caramelli, David; Barbujani, Guido (6 February 2013). "Origins and evolution of the Etruscans' mtDNA". PLOS ONE. 8 (2): e55519. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...855519G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0055519. PMC 3566088. PMID 23405165.

- Tassi, Francesca; Ghirotto, Silvia; Caramelli, David; Barbujani, Guido; et al. (2013). "Genetic evidence does not support an Etruscan origin in Anatolia". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 152 (1): 11–18. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22319. PMID 23900768.

- Claassen, Horst; Wree, Andreas (2004). "The Etruscan skulls of the Rostock anatomical collection – How do they compare with the skeletal findings of the first thousand years B.C.?". Annals of Anatomy. Amsterdam: Elsevier. 186 (2): 157–163. doi:10.1016/S0940-9602(04)80032-3. PMID 15125046.