Political party

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific ideological or policy goals.

| Part of the Politics series |

| Politics |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of the Politics series |

| Party politics |

|---|

|

|

Political parties have become a major part of the politics of almost every country, as modern party organizations developed and spread around the world over the last few centuries. It is extremely rare for a country to have no political parties. Some countries have only one political party while others have several. Parties are important in the politics of autocracies as well as democracies, though usually democracies have more political parties than autocracies. Autocracies often have a single party that governs the country, and some political scientists consider competition between two or more parties to be an essential part of democracy.

Parties can develop from existing divisions in society, like the divisions between lower and upper classes, and they streamline the process of making political decisions by encouraging their members to cooperate. Political parties usually include a party leader, who has primary responsibility for the activities of the party; party executives, who may select the leader and who perform administrative and organizational tasks; and party members, who may volunteer to help the party, donate money to it, and vote for its candidates. There are many different ways in which political parties can be structured and interact with the electorate. The contributions that citizens give to political parties are often regulated by law, and parties will sometimes govern in a way that favours the people who donate time and money to them.

Many political parties are motivated by ideological goals. It is common for democratic elections to feature competitions between liberal, conservative, and socialist parties; other common ideologies of very large political parties include communism, populism, nationalism, and Islamism. Political parties in different countries will often adopt similar colours and symbols to identify themselves with a particular ideology. However, many political parties have no ideological affiliation, and may instead be primarily engaged in patronage, clientelism, or the advancement of a specific political entrepreneur.

Definition

Political parties are collective entities that organize competitions for political offices.[1]: 3 The members of a political party contest elections under a shared label. In a narrow definition, a political party can be thought of as just the group of candidates who run for office under a party label.[2]: 3 In a broader definition, political parties are the entire apparatus that supports the election of a group of candidates, including voters and volunteers who identify with a particular political party, the official party organizations that support the election of that party's candidates, and legislators in the government who are affiliated with the party.[3] In many countries, the notion of a political party is defined in law, and governments may specify requirements for an organization to legally qualify as a political party.[4]

According to Anson D. Morse, a political party is a durable organization united by common principles which "has for its immediate end the advancement of the interests and the realization of the ideals... of the particular group or groups which it represents."[5]

Political parties are distinguished from other political groups and clubs, such as political factions or interest groups, mostly by the fact that parties are focused on electing candidates, whereas interest groups are focused on advancing a policy agenda.[6] This is related to other features that sometimes distinguish parties from other political organizations, including a larger membership, greater stability over time, and a deeper connection to the electorate.[7]

History

The idea of people forming large groups or factions to advocate for their shared interests is ancient. Plato mentions the political factions of Classical Athens in the Republic,[8] and Aristotle discusses the tendency of different types of government to produce factions in the Politics.[9] Certain ancient disputes were also factional, like the Nika riots between two chariot racing factions at the Hippodrome of Constantinople. A few instances of recorded political groups or factions in history included the late Roman Republic's Populares and Optimates factions as well as the Dutch Republic's Orangists and the Staatsgezinde. However, modern political parties are considered to have emerged around the end of the 18th century; they are usually considered to have first appeared in Europe and the United States of America, with the United Kingdom's Conservative Party and the Democratic Party of the United States both frequently called the world's "oldest continuous political party".[10][2][11][12]

Before the development of mass political parties, elections typically featured a much lower level of competition, had small enough polities that direct decision-making was feasible, and held elections that were dominated by individual networks or cliques that could independently propel a candidate to victory in an election.[13]: 510

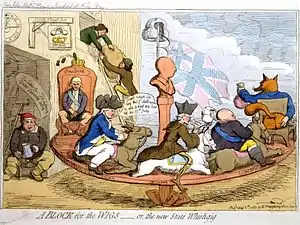

18th century

Some scholars argue that the first modern political parties developed in early modern Britain in the 18th century, after the Exclusion Crisis and the Glorious Revolution.[14]: 4 The Whig faction originally organized itself around support for Protestant constitutional monarchy as opposed to absolute rule, whereas the conservative Tory faction (originally the Royalist or Cavalier faction of the English Civil War) supported a strong monarchy, and these two groups structured disputes in the politics of the United Kingdom throughout the 18th century[14]: 4 [15] The Rockingham Whigs have been identified as the first modern political party, because they retained a coherent party label and motivating principles even while out of power.[16]

At the end of the century, the United States also developed a party system, called the First Party System. Although the framers of the 1787 United States Constitution did not all anticipate that American political disputes would be primarily organized around political parties, political controversies in the early 1790s over the extent of federal government powers saw the emergence of two proto-political parties: the Federalist Party and the Democratic-Republican Party.[17][18]

19th century

By the early 19th century, a number of countries had developed stable modern party systems. The party system that developed in Sweden has been called the world's first party system, on the basis that previous party systems were not fully stable or institutionalized.[10] In many European countries, including Belgium, Switzerland, Germany, and France, political parties organized around a liberal-conservative divide, or around religious disputes.[13]: 510 The spread of the party model of politics was accelerated by the 1848 Revolutions around Europe.[19]

The strength of political parties in the United States waned during the Era of Good Feelings, but shifted and strengthened again by the second half of the 19th century.[20][21] This was not the only country in which the strength of political parties had substantially increased by the end of the century; for example, around this time the Irish political leader Charles Stewart Parnell implemented several methods and structures like party discipline that would come to be associated with strong grassroots political parties.[22]

20th century

At the beginning of the 20th century in Europe, the liberal–conservative divide that characterized most party systems was disrupted by the emergence of socialist parties, which attracted the support of organized trade unions.[13]: 511

During the wave of decolonization in the mid-20th century, many newly sovereign countries outside of Europe and North America developed party systems that often emerged from their movements for independence.[23][24] For example, a system of political parties arose out of factions in the Indian independence movement, and was strengthened and stabilized by the policies of Indira Gandhi in the 1970s.[2]: 165 The formation of the Indian National Congress, which developed in the early 20th century as a pro-independence faction in British India and immediately became a major political party after Indian independence, foreshadowed the dynamic in many newly independent countries; for example, the Uganda National Congress was a pro-independence party and the first political party in Uganda, and its name was chosen as an homage to the Indian National Congress.[25]

As broader suffrage rights and eventually universal suffrage slowly spread throughout democracies, political parties expanded dramatically, and only then did a vision develop of political parties as intermediaries between the full public and the government.[26]

Causes of political parties

Political parties are a nearly ubiquitous feature of modern countries.[27] Nearly all democratic countries have strong political parties, and many political scientists consider countries with fewer than two parties to necessarily be autocratic.[28][29][30] However, these sources allow that a country with multiple competitive parties is not necessarily democratic, and the politics of many autocratic countries are organized around one dominant political party.[30][31] The ubiquity and strength of political parties in nearly every modern country has led researchers to remark that the existence of political parties is almost a law of politics, and to ask why parties appear to be such an essential part of modern states.[13]: 510 [1] Political scientists have therefore come up with several explanations for why political parties are a nearly universal political phenomenon.[2]: 11

Social cleavages

One of the core explanations for the existence of political parties is that they arise from pre-existing divisions among people: society is divided in a certain way, and a party is formed to organize that division into the electoral competition. By the 1950s, economists and political scientists had shown that party organizations could take advantage of the distribution of voters' preferences over political issues, adjusting themselves in response to what voters believe in order to become more competitive.[32][33] Beginning in the 1960s, academics began identifying the social cleavages in different countries that might have given rise to specific parties, such as religious cleavages in specific countries that may have produced religious parties there.[34][35]

The theory that parties are produced by social cleavages has drawn several criticisms. Some authors have challenged it on empirical grounds, either finding no evidence for the claim that parties emerge from existing cleavages, or arguing that the claim is not empirically testable.[36] Others note that while social cleavages might cause political parties to exist, this obscures the opposite effect: that political parties also cause changes in the underlying social cleavages.[2]: 13 A further objection is that, if the explanation for where parties come from is that they emerge from existing social cleavages, then the theory is an incomplete story of where political parties come from unless it also explains the origins of these social cleavages.[37]

Individual and group incentives

.jpg.webp)

An alternative explanation for why parties are ubiquitous across the world is that the formation of parties provides compatible incentives for candidates and legislators. For example, the existence of political parties might coordinate candidates across geographic districts, so that a candidate in one electoral district has an incentive to assist a similar candidate in a different district.[1] Thus, political parties can be mechanisms for preventing candidates with similar goals from acting to each other's detriment when campaigning or governing.[38] This might help explain the ubiquity of parties: if a group of candidates form a party and are harming each other less, they may perform better over the long run than unaffiliated politicians, so politicians with party affiliations will out-compete politicians without parties.[1]

Parties can also align their member's incentives when those members are in a legislature.[39] The existence of a party apparatus can help coalitions of electors to agree on ideal policy choices,[40] whereas a legislature of unaffiliated members might never be able to agree on a single best policy choice without some institution constraining their options.[41][42]

Parties as heuristics

Another prominent explanation for why political parties exist is psychological: parties may be necessary for many individuals to participate in politics because they provide a massively simplifying heuristic, which allows people to make informed choices with much less mental effort than if voters had to consciously evaluate the merits of every candidate individually.[43] Without political parties, electors would have to individually evaluate every candidate in every election. But political parties enable electors to make judgments about just a few groups, and then apply their judgment of the party to all the candidates affiliated with that group. Because it is much easier to become informed about a few parties' platforms than about many candidates' personal positions, parties reduce the cognitive burden for people to cast informed votes. However, evidence suggests that over the last several decades, the strength of party identification has been weakening, so this may be a less important function for parties to provide than it was in the past.[44]

Structure of political parties

Political parties are often structured in similar ways across countries. They typically feature a single party leader, a group of party executives, and a community of party members.[45] Parties in democracies usually select their party leadership in ways that are more open and competitive than parties in autocracies, where the selection of a new party leader is likely to be tightly controlled.[46] In countries with large sub-national regions, particularly federalist countries, there may be regional party leaders and regional party members in addition to the national membership and leadership.[2]: 75

Party leaders

Parties are typically led by a party leader, who serves as the main representative of the party and often has primary responsibility for overseeing the party's policies and strategies. The leader of the party that controls the government usually becomes the head of government, such as the president or prime minister, and the leaders of other parties explicitly compete to become the head of government.[45] In both presidential democracies and parliamentary democracies, the members of a party frequently have substantial input into the selection of party leaders, for example by voting on party leadership at a party conference.[47][48] Because the leader of a major party is a powerful and visible person, many party leaders are well-known career politicians.[49] Party leaders can be sufficiently prominent that they affect voters' perceptions of the entire party,[50] and some voters decide how to vote in elections partly based on how much they like the leaders of the different parties.[51]

The number of people involved in choosing party leaders varies widely across parties and across countries. On one extreme, party leaders might be selected from the entire electorate; on the opposite extreme, they might be selected by just one individual.[52] Selection by a smaller group can be a feature of party leadership transitions in more autocratic countries, where the existence of political parties may be severely constrained to only one legal political party, or only one competitive party. Some of these parties, like the Chinese Communist Party, have rigid methods for selecting the next party leader, which involves selection by other party members.[53] A small number of single-party states have hereditary succession, where party leadership is inherited by the child of an outgoing party leader.[54] Autocratic parties use more restrictive selection methods to avoid having major shifts in the regime as a result of successions.[46]

Party executives

In both democratic and non-democratic countries, the party leader is often the foremost member of a larger party leadership. A party executive will commonly include administrative positions, like a party secretary and a party chair, who may be different people from the party leader.[55][56] These executive organizations may serve to constrain the party leader, especially if that leader is an autocrat.[57][58] It is common for political parties to conduct major leadership decisions, like selecting a party executive and setting their policy goals, during regular party conferences.[59]

Much as party leaders who are not in power are usually at least nominally competing to become the head of government, the entire party executive may be competing for various positions in the government. For example, in Westminster systems, the largest party that is out of power will form the Official Opposition in parliament, and select a shadow cabinet which (among other functions) provides a signal about which members of the party would hold which positions in the government if the party were to win an election.[60]

Party membership

Citizens in a democracy will often affiliate with a specific political party. Party membership may include paying dues, an agreement not to affiliate with multiple parties at the same time, and sometimes a statement of agreement with the party's policies and platform.[61] In democratic countries, members of political parties often are allowed to participate in elections to choose the party leadership.[52] Party members may form the base of the volunteer activists and donors who support political parties during campaigns.[62] The extent of participation in party organizations can be affected by a country's political institutions, with certain electoral systems and party systems encouraging higher party membership.[63] Since at least the 1980s, membership in large traditional party organizations has been steadily declining across a number of countries, particularly longstanding European democracies.[64]

Types of party organizations

Political scientists have distinguished between different types of political parties that have evolved throughout history. These include cadre parties, mass parties, catch-all parties and cartel parties.[65]: 163–178 Cadre parties were political elites that were concerned with contesting elections and restricted the influence of outsiders, who were only required to assist in election campaigns. Mass parties tried to recruit new members who were a source of party income and were often expected to spread party ideology as well as assist in elections. In the United States, where both major parties were cadre parties, the introduction of primaries and other reforms has transformed them so that power is held by activists who compete over influence and nomination of candidates.[66]

Cadre parties

A cadre party, or elite party, is a type of political party that was dominant in the nineteenth century before the introduction of universal suffrage. The French political scientist Maurice Duverger first distinguished between "cadre" and "mass" parties, founding his distinction on the differences within the organisational structures of these two types.[67]: 60–71 Cadre parties are characterized by minimal and loose organisation, and are financed by fewer larger monetary contributions typically originating from outside the party. Cadre parties give little priority to expanding the party's membership base, and its leaders are its only members.[68][65]: 165 The earliest political parties, such as the Democratic-Republicans and the Federalists, are classified as cadre parties.[69]

Mass parties

A mass party is a type of political party that developed around cleavages in society and mobilized the ordinary citizens or 'masses' in the political process.[69] In Europe, the introduction of universal suffrage resulted in the creation of worker's parties that later evolved into mass parties; an example is the German Social Democratic Party.[65]: 165 These parties represented large groups of citizens who had not previously been represented in political processes, articulating the interests of different groups in society. In contrast to cadre parties, mass parties are funded by their members, and rely on and maintain a large membership base. Further, mass parties prioritize the mobilization of voters and are more centralized than cadre parties.[69][70]

Catch-all parties

The term "catch-all party" was developed by German-American political scientist Otto Kirchheimer to describe the parties that developed in the 1950s and 1960s as a result of changes within the mass parties.[71][65]: 165 The term "big tent party" may be used interchangeably. Kirchheimer characterized the shift from the traditional mass parties to catch-all parties as a set of developments including the "drastic reduction of the party's ideological baggage" and the "downgrading of the role of the individual party member".[72] By broadening their central ideologies into more open-ended ones, catch-all parties seek to secure the support of a wider section of the population. Further, the role of members is reduced as catch-all parties are financed in part by the state or by donations.[65]: 163–178 In Europe, the shift of Christian Democratic parties that were organized around religion into broader centre-right parties epitomizes this type.[73]

Cartel parties

Cartel parties are a type of political party that emerged post-1970s and are characterized by heavy state financing and the diminished role of ideology as an organizing principle. The cartel party thesis was developed by Richard Katz and Peter Mair, who wrote that political parties have turned into "semi-state agencies",[74] acting on behalf of the state rather than groups in society. The term 'cartel' refers to the way in which prominent parties in government make it difficult for new parties to enter, as such forming a cartel of established parties. As with catch-all parties, the role of members in cartel parties is largely insignificant as parties use the resources of the state to maintain their position within the political system.[65]: 163–178

Niche parties

Niche parties are a type of political party that developed on the basis of the emergence of new cleavages and issues in politics, such as immigration and the environment.[75] In contrast to mainstream or catch-all parties, niche parties articulate an often limited set of interests in a way that does not conform to the dominant economic left-right divide in politics, in turn emphasising issues that do not attain prominence within the other parties.[76] Further, niche parties do not respond to changes in public opinion to the extent that mainstream parties do. Examples of niche parties include Green parties and extreme nationalist parties, such as the National Rally in France.[77] However, over time these parties may grow in size and shed some of their niche qualities as they become larger, a phenonmenon observable among European Green parties during their transformation from radical environmentalist movements to mainstream centre-left parties.[76]

Entrepreneurial parties

An Entrepreneurial party is a political party that is centered on a political entrepreneur, and dedicated to the advancement of that person or their policies.[78] While some definitions of political parties state that a party is an organization that advances a specific set of ideological or policy goals,[79] many political parties are not primarily motivated by ideology or policy, and instead exist to advance the career of a specific political entrepreneur.[80][81]

Party positions and ideologies

Ideological roles and types

Political ideologies are one of the major organizing features of political parties, and parties often officially align themselves with specific ideologies. Parties adopt ideologies for a number of reasons. Ideological affiliations for political parties send signals about the types of policies they might pursue if they were in power.[82] Ideologies also differentiate parties from one another, so that voters can select the party that advances the policies that they most prefer.[83] A party may also seek to advance an ideology by convincing voters to adopt its belief system.[84]

Common ideologies that can form a central part of the identity of a political party include liberalism, conservatism, socialism, communism, anarchism, fascism, feminism, environmentalism, nationalism, fundamentalism,[85] Islamism, and multiculturalism.[86] Liberalism is the ideology that is most closely connected to the history of democracies and is often considered to be the dominant or default ideology of governing parties in much of the contemporary world.[87] Many of the traditional competitors to liberal parties are conservative parties.[87] Socialist, communist, anarchist, fascist, and nationalist parties are more recent developments, largely entering political competitions only in the 19th and 20th centuries.[87] Feminism, environmentalism, multiculturalism, and certain types of fundamentalism became prominent towards the end of the 20th century.[87]

Parties can sometimes be organized according to their ideology using an economic left–right political spectrum. However, a simple left-right economic axis does not fully capture the variation in party ideologies.[88] Other common axes that are used to compare the ideologies of political parties include ranges from liberal to authoritarian,[89] from pro-establishment to anti-establishment, and from tolerant and pluralistic (in their behavior while participating in the political arena) to anti-system.[88]

Non-ideological parties

Though ideologies are central to a large number of political parties around the world, not all political parties have an organizing ideology, or exist to promote ideological policies. For example, some political parties may be clientelistic or patronage-based organizations, which are largely concerned with distributing goods.[90] Other political parties may be created as tools for the advancement of an individual politician.[81][91] It is also common, in countries with important social cleavages along ethnic or racial lines, to represent the interests of one ethnic group or another.[92] This may involve a non-ideological attachment to the interests of that group, or may be a commitment based on an ideology like identity politics. While any of these types of parties may be ideological, there are political parties that do not have any organizing ideology.[80]

Party systems

Political parties are ubiquitous across both democratic and autocratic countries, and there is often very little change in which political parties have a chance of holding power in a country from one election to the next. This makes it possible to think about the political parties in a country as collectively forming one of the country's central political institutions, called a party system.[93] Some basic features of a party system are the number of parties and what sorts of parties are the most successful.[94] These properties are closely connected to other major features of the country's politics, such as how democratic it is, what sorts of restrictions its laws impose on political parties, and what type of electoral systems it uses.[93] Even in countries where the number of political parties is not officially constrained by law, political institutions affect how many parties are viable. For example, democracies that use a single-member district electoral system tend to have very few parties, whereas countries that use proportional representation tend to have more.[95]: ch. 7 The number of parties in a country can also be accurately estimated based on the magnitude of a country's electoral districts and the number of seats in its legislature.[95]: 255

An informative way to classify the party systems of the world is by how many parties they include.[94] Because some party systems include a large number of parties that have a very low probability of winning elections, it is often useful to think about the effective number of parties (the number of parties weighted by the strength of those parties) rather than the literal number of registered parties.[96]

Non-partisan systems

In a non-partisan system, no political parties exist, or political parties are not a major part of the political system. There are very few countries without political parties.[97]

In some non-partisan countries, the formation of parties is explicitly banned by law.[98] The existence of political parties may be banned in autocratic countries in order to prevent a turnover in power.[99] For example, in Saudi Arabia, a ban on political parties has been used as a tool for protecting the monarchy.[99] However, parties are also banned in some polities that have long democratic histories, usually in local or regional elections of countries that have strong national party systems.[100][101][102]

Political parties may also temporarily cease to exist in countries that have either only been established recently, or that have experienced a major upheaval in their politics and have not yet returned to a stable system of political parties. For example, the United States began as a non-partisan democracy, and it evolved a stable system of political parties over the course of many decades.[1]: ch.4 A country's party system may also dissolve and take time to re-form, leaving a period of minimal or no party system, such as in Peru following the regime of Alberto Fujimori.[103] However, it is also possible – albeit rare – for countries with no bans on political parties, and which have not experienced a major disruption, to nevertheless have no political parties: there are a small number of pacific island democracies, such as Palau, where political parties are permitted to exist and yet parties are not an important part of national politics.[98]

One-party systems

In a one-party system, power is held entirely by one political party. When only one political party exists, it may be the result of a ban on the formation of any competing political parties, which is a common feature in authoritarian states. For example, the Communist Party of Cuba is the only permitted political party in Cuba, and is the only party that can hold seats in the legislature.[104] When only one powerful party is legally permitted to exist, its membership can grow to contain a very large portion of society and it can play substantial roles in civil society that are not necessarily directly related to political governance; one example of this is the Chinese Communist Party.[105] Bans on competing parties can also ensure that only one party can ever realistically hold power, even without completely outlawing all other political parties. For example, in North Korea, more than one party is officially permitted to exist and even to seat members in the legislature,[106] but laws ensure that the Workers' Party of Korea retains control.[107]

It is also possible for countries with free elections to have only one party that holds power. These cases are sometimes called dominant-party systems or particracies. Scholars have debated whether or not a country that has never experienced a transfer of power from one party to another can nevertheless be considered a democracy.[28]: 23 There have been periods of government exclusively or entirely by one party in some countries that are often considered to have been democratic, and which had no official legal barriers to the inclusion of other parties in the government; this includes recent periods in Botswana, Japan, Mexico, Senegal, and South Africa.[28]: 24–27 It can also occur that one political party dominates a sub-national region of a democratic country that has a competitive national party system; one example is the southern United States during much of the 19th and 20th centuries, where the Democratic Party had almost complete control, with the Southern states being functionally one-party regimes, though opposition parties were never prohibited.[108]

Two-party systems

In several countries, there are only two parties that have a realistic chance of competing to form government.[109] One canonical two-party democracy is the United States, where the national government has for much of the country's history exclusively controlled by either the Democratic Party and the Republican Party.[110] Other examples of countries which have had long periods of two-party dominance include Colombia, Uruguay,[111] Malta,[112] and Ghana.[113] Two-party systems are not limited to democracies; they may be present in authoritarian regimes as well. Competition between two parties has occurred in historical autocratic regimes in countries including Brazil[114] and Venezuela.[115]

A democracy's political institutions can shape the number of parties that it has. In the 1950s Maurice Duverger observed that single-member district single-vote plurality-rule elections tend to produce two-party systems,[67]: 217 and this phenomenon came to be known as Duverger's law. Whether or not this pattern is true has been heavily debated over the last several decades.[116] Some political scientists have broadened this idea to argue that more restrictive political institutions (of which first past the post is one example) tend to produce a smaller number of political parties, so that extremely small parties systems – like those with only two parties – tend to form in countries with very restrictive rules.[117]

Two-party systems have attracted heavy criticism for limiting the choices that electors have, and much of this criticism has centered around their association with restrictive political institutions. For example, some commentators argue that political institutions in prominent two-party systems like the United States have been specifically designed to ensure that no third party can become competitive.[118] Criticisms also center around these systems' tendencies to encourage insincere voting and to facilitate the spoiler effect.[119]: ch. 1

Multi-party systems

Multi-party systems are systems in which more than two parties have a realistic chance of holding power and influencing policy.[111] A very large number of systems around the world have had periods of multi-party competition,[120] and two-party democracies may be considered unusual or uncommon compared to multi-party systems.[121] Many of the largest democracies in the world have had long periods of multi-party competition, including India,[122] Indonesia,[123] Pakistan,[124] and Brazil.[125] Multi-party systems encourage characteristically different types of governance than smaller party systems, for example by often encouraging the formation of coalition governments.[126]

The presence of many competing political parties is usually associated with a greater level of democracy, and a country transitioning from having a one-party system to having a many-party system is often considered to be democratizing.[127] Authoritarian countries can include multi-party competition, but typically this occurs when the elections are not fair.[128] For this reason, in two-party democracies like the United States, proponents of forming new competitive political parties often argue that developing a multi-party system would make the country more democratic.[129] However, the question of whether multi-party systems are more democratic than two-party systems, or if they enjoy better policy outcomes, is a subject of substantial disagreement among scholars[130][131] as well as among the public.[132][133] In the opposite extreme, a country with a very large number of parties can experience governing coalitions that include highly ideologically diverse parties that are unable to make much policy progress, which may cause the country to be unstable and experience a very large number of elections; examples of systems that have been described as having these problems include periods in the recent history of Israel,[134] Italy, and Finland.[135] Multi-party systems are often viewed as fairer or more representative than one- or two-party systems,[136] but they also have downsides, like the likelihood that in a system with plurality voting the winner of a race with many options will only have minority support.[92]

Some multi-party systems may have two parties that are noticeably more competitive than the other parties.[137] Such party systems have been called "two-party-plus" systems, which refers to the two dominant parties, plus other parties that exist but rarely or never hold power in the government.[138] Such parties may serve a crucial factor in election outcomes.[139] It is also possible for very large multi-party systems, like India's, to nevertheless be characterized largely by a series of regional contests that realistically have only two competitive parties, but in the aggregate can produce many more than two parties that have major roles in the country's national politics.[122]

Funding

Many of the activities of political parties involve the acquisition and allocation of funds in order to achieve political goals. The funding involved can be very substantial, with contemporary elections in the largest democracies typically costing billions or even tens of billions of dollars.[140][141] Much of this expense is paid by candidates and political parties, which often develop sophisticated fundraising organizations.[142] Because paying for participation in electoral contests is such a central democratic activity, the funding of political parties is an important feature of a country's politics.[142]

Sources of party funds

Common sources of party funding across countries include dues-paying party members, advocacy groups and lobbying organizations, corporations, trade unions, and candidates who may self-fund activities.[143] In most countries, the government also provides some level of funding for political parties.[142][144] Nearly all of the 180 countries examined by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance have some form of public funding for political parties, and about a third have regular payments of government funds that goes beyond campaign reimbursements.[145] In some countries, public funding for parties depends on the size of that party: for example, a country may only provide funding to parties which have more than a certain number of candidates or supporters.[145] A common argument for public funding of political parties is that it creates fairer and more democratic elections by enabling more groups to compete, whereas many advocates for private funding of parties argue that donations to parties are a form of political expression that should be protected in a democracy.[146] Public financing of political parties may decrease parties' pursuit of funds through corrupt methods, by decreasing their incentive to find alternate sources of funding.[147]

One way of categorizing the sources of party funding is between public funding and private funding. Another dichotomy is between plutocratic and grassroots sources; parties which get much of their funding from large corporations may tend to pursue different policies and use different strategies than parties which are mostly funded through small donations by individual supporters.[148] Private funding for political parties can also be thought of as coming from internal or external sources: this distinguishes between dues from party members or contributions by candidates, and donations from entities outside of the party like non-members, corporations, or trade unions.[148] Internal funding may be preferred because external sources might make the party beholden to an outside entity.[148]

Uses for party funds

There are many ways in which political parties may deploy money in order to secure better electoral outcomes. Parties often spend money to train activists, recruit volunteers, create and deploy advertisements, conduct research and support for their leadership in between elections, and promote their policy agenda.[142] Many political parties and candidates engage in a practice called clientelism, in which they distribute material rewards to people in exchange for political support; in many countries this is illegal, though even where it is illegal it may nevertheless be widespread in practice.[149] Some parties engage directly in vote buying, in which a party gives money to a person in exchange for their vote.[150]

Though it may be crucial for a party to spend more than some threshold to win a given election, there are typically diminishing returns for expenses during a campaign.[151] Once a party has crossed a particular spending threshold, additional expenditures might not increase their chance of success.[152]

Restrictions

Fundraising and expenditures by political parties are typically regulated by governments, with many countries' regulations focusing on who can contribute money to parties, how parties' money can be spent, and how much of it can pass through the hands of a political party.[153] Two main ways in which regulations affect parties are by intervening in their sources of income and by mandating that they maintain some level of transparency about their funding.[154] One common type of restriction on how parties acquire money is to limit who can donate money to political parties; for example, people who are not citizens of a country may not be allowed to make contributions to that country's political parties, in order to prevent foreign interference.[153] It is also common to limit how much money an individual can give to a political party each election.[155] Similarly, many governments cap the total amount of money that can be spent by each party in an election.[144] Transparency regulations may require parties to disclose detailed financial information to the government, and in many countries transparency laws require those disclosures to be available to the public, as a safeguard against potential corruption.[142] Creating, implementing, and amending laws regarding party expenses can be extremely difficult, since governments may be controlled by the very parties that these regulations restrict.[142]

Party colours and symbols

Nearly all political parties associate themselves with specific colours and symbols, primarily to aid voters in identifying, recognizing, and remembering the party. This branding is particularly important in polities where much of the population may be illiterate, so that someone who cannot read a party's name on a ballot can instead identify that party by colour or logo.[156] Parties of similar ideologies will often use the same colours across different countries.[157][158] Colour associations are useful as a short-hand for referring to and representing parties in graphical media.[159] They can also be used to refer to coalitions and alliances between political parties and other organizations;[160] examples include purple alliances, red–green alliances, traffic light coalitions, pan-green coalitions, and pan-blue coalitions.

However, associations between colour and ideology can also be inconsistent: parties of the same ideology in different countries often use different colours, and sometimes competing parties in a country may even adopt the same colours.[161] These associations also have major exceptions. For example, in the United States, red is associated with the more conservative Republican Party while blue is associated with the more left-leaning Democratic Party.[157][162]

| Ideology | Colours | Symbols | Examples | References |

| Agrarianism |

|

|

.svg.png.webp)  |

[158]: 58 [163][164][165] |

| Anarchism |

|

|

|

[166][167][168][169] |

| Centrism |

|

.svg.png.webp)   |

[170][171] | |

| Christian Democracy |

|

Christian cross |  |

[172] |

| Communism |

|

|

|

[173][174][175] |

| Conservatism |

|

_Emblem.svg.png.webp) |

[176][177] | |

| Democratic socialism |

|

|

|

[178][179] |

| Fascism |

|

|

[158]: 56 [180][181] | |

| Feminism |

|

|

|

[182][183] |

| Green politics |

|

|

|

[184][185] |

| Islamism |

|

Star and crescent | .svg.png.webp) |

[157][186] |

| Liberalism |

|

Bird in flight |  |

[159][187][188] |

| Libertarianism |

|

|

|

[157][189][190][191] |

| Monarchism |

|

Crown |   |

[158][192][193] |

| Pacifism |

|

|

|

[158][194] |

| Social democracy |

|

|

.svg.png.webp)   |

[195][196][197][178] |

| Socialism |

|

Red rose |  |

[173][198][199][200][178] |

See also

- List of largest political parties

- List of ruling political parties by country

- Lists of political parties by country

References

- Aldrich, John (1995). "1". Why Parties?: The Origin and Transformation of Political Parties in America. University of Chicago Press.

- Chhibber, Pradeep K.; Kollman, Ken (2004). The formation of national party systems: Federalism and party competition in Canada, Great Britain, India, and the United States. Princeton University Press.

- Sarah F. Anzia; Olivia M. Meeks (May 2016). "Political Parties and Policy Demanders in Local Elections" (PDF). University of Maryland-Hewlett Foundation Conference on Parties, Polarization and Policy Demanders. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- Avnon, Dan (16 November 2007). "Parties laws in democratic systems of government". The Journal of Legislative Studies. 1 (2): 283–300. doi:10.1080/13572339508420429.

- Morse, Anson D. (1896). "What is a Party?". Political Science Quarterly. 11 (1): 68–81. doi:10.2307/2139602. ISSN 0032-3195. JSTOR 2139602.

- John Anthony Maltese; Joseph A. Pika; W. Phillips Shively (2020). American democracy in context. Sage. p. 182. ISBN 978-1544345222.

- Belloni, Frank P.; Beller, Dennis C. (1976). "The Study of Party Factions as Competitive Political Organizations". The Western Political Quarterly. 29 (4): 531–549. doi:10.1177/106591297602900405. S2CID 144697443.

- Plato (1935). The Republic. Macmillan and Co, Ltd. p. 462.

- Aristotle (1984). The Politics. The University of Chicago Press. p. 135.

- Metcalf, Michael F. (1977). "The first "modern" party system? Political parties, Sweden's Age of liberty and the historians". Scandinavian Journal of History. 2 (1–4): 265–287. doi:10.1080/03468757708578923.

- Dirr, Alison (24 October 2016). "Is the Democratic Party the oldest continuous political party in the world?". Politifact Wisconsin. Archived from the original on 30 September 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Stanek, Wojciech (1996). Konfederacje a ewolucja mechanizmów walki politycznej w Rzeczypospolitej XVIII wieku. Olsztyn: Interpress. pp. 135–136.

- Carles Boix (2009). "The Emergence of Parties and Party Systems". In Carles Boix; Susan C. Stokes (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Politics. Oxford University Press. pp. 499–521. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199566020.003.0021. ISBN 978-0199566020.

- Jones, J. R. (1961). The First Whigs. The Politics of the Exclusion Crisis. 1678–1683. Oxford University Press.

- Hamowy, Ronald (2008). "Whiggism". The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; Cato Institute. pp. 542–543. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n328. ISBN 978-1-4129-6580-4. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024. Archived from the original on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- "ConHome op-ed: the USA, Radical Conservatism and Edmund Burke". Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- Hofstadter, Richard (1970). The Idea of a Party System: The Rise of Legitimate Opposition in the United States, 1780–1840. University of California Press. p. ix.

- William Nisbet Chambers, ed. (1972). The first party system. New York: Wiley. p. 1. ISBN 978-0471143406.

- Busky, Donald F. (2000), Democratic Socialism: A Global Survey, Westport, Connecticut, USA: Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc., p. 8,

The Frankfurt Declaration of the Socialist International, which almost all social democratic parties are members of, declares the goal of the development of democratic socialism

- Minicucci, Stephen (2004). "Internal Improvements and the Union, 1790–1860". Studies in American Political Development. Cambridge University Press. 18 (2): 160–185. doi:10.1017/S0898588X04000094. S2CID 144902648.

- Kollman, Ken (2012). The American political system. W. W. Norton and Company. p. 465.

- Jordan, Donald (1986). "John O'Connor Power, Charles Stewart Parnell and the Centralization of Popular Politics in Ireland". Irish Historical Studies. 25 (97): 46–66. doi:10.1017/S0021121400025335. S2CID 156076896.

- Liddiard, Patrick. "What Can Be Done About the Problem of Political Parties?". Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Archived from the original on 15 February 2021. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- Angrist, Michele Penner (2006). "1". Party Building in the Modern Middle East. University of Washington Press. pp. 31–54. ISBN 978-0295986463.

- Byamukama, Nathan (October 2003). "Formation and Impact of Political Parties in 1950s up to Independence (1962): Lessons for Democracy" (PDF). Conference on Constitutalism and Multiparty Governance in Uganda: 7. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- Corder, J. Kevin; Wolbrecht, Christina (2006). "Political Context and the Turnout of New Women Voters after Suffrage". The Journal of Politics. 68 (1): 34–49. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00367.x. S2CID 54176570.

- Muirhead, Russell; Rosenblum, Nancy L. (2020). "The Political Theory of Parties and Partisanship: Catching up". Annual Review of Political Science. 23: 95–110. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-041916-020727.

- Przeworski, Adam; Alvarez, Michael E.; Cheibub, Jose Antonio; Limongi, Fernando (2000). Democracy and development: Political institutions and well-being in the world, 1950–1990. Cambridge University Press. p. 20.

- Boix, Carles; Miller, Michael; Rosato, Sebastian (2013). "A complete data set of political regimes, 1800–2007". Comparative Political Studies. 46 (12): 1523–1554. doi:10.1177/0010414012463905. S2CID 45833659.

- Svolik, Milan (2008). "Authoritarian reversals and democratic consolidation". American Political Science Review. 102 (2): 153–168. doi:10.1017/S0003055408080143. S2CID 34430604.

- Knutsen, Carl Henrik; Nygård, Håvard Mokleiv; Wig, Tore (2017). "Autocratic elections: Stabilizing tool or force for change?". World Politics. 69 (1): 98–143. doi:10.1017/S0043887116000149.

- Downs, Anthony (1957). An economic theory of democracy. Harper Collins. pp. 114–142.

- Adams, James (December 2010). "Review of Voting for Policy, Not Parties: How Voters Compensate for Power Sharing, by Orit Kedar". Perspectives on Politics. 8 (4): 1257–1258. doi:10.1017/S153759271000280X. S2CID 147390789.

- Lipset, Seymour Martin; Rokkan, Stein (1967). Cleavage structures, party systems, and voter alignments: Cross-national perspectives. New York Free Press. p. 50.

- Ware, Alan (1995). Political parties and party systems. Oxford University Press. p. 22.

- Lybeck, Johan A. (2017). "Is the Lipset-Rokkan Hypothesis Testable?". Scandinavian Political Studies. 8 (1–2): 105–113. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9477.1985.tb00314.x.

- Tilly, Charles (1990). Coercion, capital, and European states. Blackwell. p. 74.

- Hicken, Allen (2009). Building party systems in developing democracies. Cambridge University Press. p. 5.

- Cox, Gary; Nubbins, Mathew (1999). Legislative leviathan. University of California Press. p. 10.

- Tsebelis, George (2000). "Veto players and institutional analysis". Governance. 13 (4): 441–474. doi:10.1111/0952-1895.00141.

- McKelvey, Richard D. (1976). "Intransitivities in multidimensional voting bodies". Journal of Economic Theory. 12: 472–482. doi:10.1016/0022-0531(76)90040-5.

- Schofield, Norman (1983). "Generic instability of majority rule". Review of Economic Studies. 50 (4): 695–705. doi:10.2307/2297770. JSTOR 2297770.

- Campbell, Angus; Converse, Philip; Miller, Warren; Stokes, Donald (1960). The American Voter. University of Chicago Press. pp. 120–146.

- Dalton, Russell J.; Wattenberg, Martin P. (2002). Parties without partisans: Political change in advanced industrial democracies. Oxford University Press. p. 3.

- Ludger Helms, ed. (2012). Comparative Political Leadership. Springer. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-349-33368-4.

- Helms, Ludger (11 March 2020). "Leadership succession in politics: The democracy/autocracy divide revisited". The British Journal of Politics and International Relations. 22 (2): 328–346. doi:10.1177/1369148120908528.

- Marsh, Michael (October 1993). "Introduction: Selecting the party leader". European Journal of Political Research. 24 (3): 229–231. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.1993.tb00378.x.

- William Cross; André Blais (26 January 2011). "Who selects the party leader?". Party Politics. 18 (2): 127–150. doi:10.1177/1354068810382935. S2CID 144582117.

- Barber, Stephen (17 September 2013). "Arise, Careerless Politician: The Rise of the Professional Party Leader". Politics. 34 (1): 23–31. doi:10.1111/1467-9256.12030. S2CID 143270021.

- Garzia, Diego (3 September 2012). "Party and Leader Effects in Parliamentary Elections: Towards a Reassessment". Politics. 32 (3): 175–185. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9256.2012.01443.x. hdl:1814/23834. S2CID 55189815.

- Jean-François Daoust; André Blais; Gabrielle Péloquin-Skulski (29 April 2019). "What do voters do when they prefer a leader from another party?". Party Politics. 50 (2): 1103–1109. doi:10.1177/1354068819845100. S2CID 155675264.

- Kenig, Ofer (30 October 2009). "Classifying Party Leaders' Selection Methods in Parliamentary Democracies". Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties. 19 (4): 433–447. doi:10.1080/17457280903275261. S2CID 146321598.

- Li Cheng; Lynn White (1998). "The Fifteenth Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party: Full-Fledged Technocratic Leadership with Partial Control by Jiang Zemin". Asian Survey. 38 (3): 231–264. doi:10.2307/2645427. JSTOR 2645427.

- Brownlee, Jason (July 2007). "Hereditary Succession in Modern Autocracies". World Politics. 59 (4): 595–628. doi:10.1353/wp.2008.0002. S2CID 154483430.

- Lewis, Paul Geoffrey (1989). Political Authority and Party Secretaries in Poland, 1975–1986. Cambridge University Press. pp. 29–51. ISBN 978-0521363693.

- Martz, John D. (1966). "The Party Organization: Structural Framework". Accion Democratica: Evolution of a Modern Political Party in Venezuela. Princeton University Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-1400875870.

- Trevaskes, Susan (16 April 2018). "A Law Unto Itself: Chinese Communist Party Leadership and Yifa zhiguo in the Xi Era". Modern China. 44 (4): 347–373. doi:10.1177/0097700418770176. S2CID 149719307.

- Kroeger, Alex M. (9 March 2018). "Dominant Party Rule, Elections, and Cabinet Instability in African Autocracies". British Journal of Political Science. 50 (1): 79–101. doi:10.1017/S0007123417000497. S2CID 158190033.

- Jean-Benoit Pilet; William Cross, eds. (2014). The Selection of Political Party Leaders in Contemporary Parliamentary Democracies: A Comparative Study. Routledge. p. 13. ISBN 978-1317929451.

- Andrew C. Eggers; Arthur Spirling (11 April 2016). "The Shadow Cabinet in Westminster Systems: Modeling Opposition Agenda Setting in the House of Commons, 1832–1915". British Journal of Political Science. 48 (2): 343–367. doi:10.1017/S0007123416000016. S2CID 155635327.

- Gauja, Anika (4 December 2014). "The construction of party membership". European Journal of Political Research. 54 (2): 232–248. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12078.

- Weldon, Steven (1 July 2006). "Downsize My Polity? The Impact of Size on Party Membership and Member Activism". Party Politics. 12 (4): 467–481. doi:10.1177/1354068806064729. S2CID 145573225.

- Smith, Alison F. (2020). Political Party Membership in New Democracies. Springer. p. 2. ISBN 978-3030417956.

- Peter Mair; Ingrid van Biezen (1 January 2001). "Party Membership in Twenty European Democracies, 1980–2000". Party Politics. 7 (1): 5–21. doi:10.1177/1354068801007001001. S2CID 143913812.

- Schumacher, Gijs (2017). "The Transformation of Political Parties". In van Praag, Philip (ed.). Political Science and Changing Politics. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Ware, Alan. Political parties. pp. 65–67.

- Duverger, Maurice (1964). Political Parties: Their Organisation and Activity in the Modern State (3 ed.). London: Methuen.

- Katz, Richard S.; Mair, Peter (1995). "Changing Models of Party Organisation and Party Democracy: The Emergence of the Cartel Party". Party Politics. 1 (1): 20. doi:10.1177/1354068895001001001. S2CID 143611762.

- Hague, Rod; McCormick, John; Harrop, Martin (2019). Comparative Government and Politics, An Introduction (11 ed.). Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 271.

- Angell, Harold M. (June 1987). "Duverger, Epstein and the Problem of the Mass Party: The Case of the Parti Québécois". Canadian Journal of Political Science. 20 (2): 364. doi:10.1017/S0008423900049489. S2CID 154446570.

- Krouwel, Andre (2003). "Otto Kirchheimer and the Catch-All Party". West European Politics. 26 (2): 24. doi:10.1080/01402380512331341091. S2CID 145308222.

- Kirchheimer, Otto (1966). 'The Transformation of Western European Party Systems', in J. LaPalombara and M. Weiner (eds.), Political Parties and Political Development. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, pp. 177–200 [190]

- Hague, Rod; McCormick, John; Harrop, Martin (2019). Comparative Government and Politics, An Introduction (11 ed.). Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 272.

- Katz, Richard S.; Mair, Peter (1995). "Changing Models of Party Organisation and Party Democracy: The Emergence of the Cartel Party". Party Politics. 1 (1): 16. doi:10.1177/1354068895001001001. S2CID 143611762.

- Meguid, Bonnie M. (2005). "Competition Between Unequals: The Role of Mainstream Party Strategy in Niche Party Success". American Political Science Review. 99 (3): 347–348. doi:10.1017/S0003055405051701. S2CID 145304603.

- Meyer, Thomas; Miller, Bernhard (2015). "The niche party concept and its measurement". Party Politics. 21 (2): 259–271. doi:10.1177/1354068812472582. PMC 5180693. PMID 28066152.

- Adams, James; Clark, Michael; Ezrow, Lawrence; Glasgow, Garrett (2006). "Are Niche Parties Fundamentally Different from Mainstream Parties? The Causes and the Electoral Consequences of Western European Parties' Policy Shifts, 1976–1998" (PDF). American Journal of Political Science. 50 (3): 513–529. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00199.x. S2CID 30867881. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Kosowska-Gąstoł, Beata; Sobolewska-Myślik, Katarzyna (2017). "New Political Entrepreneurs in Poland" (PDF). Politologický časopis - Czech Journal of Political Science. 24 (2): 137–157. doi:10.5817/PC2017-2-137. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- "The purpose of political parties". Government of the Netherlands. 3 September 2014. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- Olanrewaju, John S. (28 June 2017). "Political Parties and Poverty of Ideology in Nigeria". Afro Asian Journal of Social Sciences. VI (3): 1–16.

- Catherine E. De Vries; Sara B. Hobolt (2019). Political Entrepreneurs: The Rise of Challenger Parties in Europe. Princeton University Press. pp. 1–38. ISBN 978-0691194752.

- Hooghe, Liesbet (2007). "What Drives Euroskepticism? Party–Public Cueing, Ideology and Strategic Opportunity". European Union Politics. 8 (1): 5–12. doi:10.1177/1465116507073283. S2CID 154281437. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- Lachat, Romain (December 2008). "The impact of party polarization on ideological voting". Electoral Studies. 27 (4): 687–698. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2008.06.002.

- Roemer, John E. (June 1994). "The Strategic Role of Party Ideology When Voters are Uncertain About How the Economy Works". The American Political Science Review. 88 (2): 327–335. doi:10.2307/2944707. JSTOR 2944707. S2CID 145184235.

- Vincent, Andrew (2009). Modern Political Ideologies. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-1444311051.

- Heywood, Andrew (2017). Political Ideologies: An Introduction. Macmillan International Higher Education. pp. 1–23. ISBN 978-1137606044.

- Freeden, Michael (1996). Ideologies and Political Theory: A Conceptual Approach. Clarendon Press. pp. vii–x. ISBN 978-0198275329.

- Richard Gunther; Larry Diamond (1 March 2003). "Species of Political Parties: A New Typology". Party Politics. 9 (2): 167–199. doi:10.1177/13540688030092003. S2CID 16407503.

- Anna Lührmann; Juraj Medzihorsky; Garry Hindle; Staffan I. Lindberg (26 October 2020). "New Global Data on Political Parties: V-Party". V-Dem Briefing Paper (9): 1–4.

- Hicken, Allen (17 March 2011). "Clientelism". Annual Review of Political Science. 14: 289–310. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.031908.220508.

- Mark Schneider; Paul Teske (September 1992). "Toward A Theory of the Political Entrepreneur: Evidence from Local Government". The American Political Science Review. 86 (3): 737–747. doi:10.2307/1964135. JSTOR 1964135. S2CID 155041917.

- Ganawari, Bharatu G. (2017). "The stability of multi-party system in Indian democracy: A critique". International Journal of Arts and Science Research. 4 (2): 97–102.

- Scott Mainwaring; Mariano Torcal (2005). "Party System Institutionalization and Party System Theory After the Third Wave of Democratization". In Richard S. Katz; William Crotty (eds.). Handbook of Party Politics. Sage Publications. pp. 204–227. doi:10.4135/9781848608047.n19. ISBN 978-0761943143.

- Birch, Sarah (2003). Electoral Systems and Political Transformation in Post-Communist Europe. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 99–118. doi:10.1057/9781403938763. ISBN 978-1-349-43138-0.

- Shugart, Matthew S.; Taagepera, Rein (2017). Votes from Seats: Logical models of electoral systems. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1108404266.

- Laakso, Markku; Taagepera, Rein (1979). ""Effective" Number of Parties: A Measure with Application to West Europe". Comparative Political Studies. 12 (1): 3–27. doi:10.1177/001041407901200101. ISSN 0010-4140. S2CID 143250203. Archived from the original on 17 March 2021. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- Schattschneider, E. E. (1942). Party Government. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. p. 1. ISBN 978-1412830508.

- Veenendaal, Wouter P. (2013). "How democracy functions without parties: The Republic of Palau". Party Politics. 22 (1): 27–36. doi:10.1177/1354068813509524. S2CID 144651495.

- "Saudi Arabia: Political Party Formed". The New York Times. 10 February 2011. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- Brian F. Schaffner; Matthew Streb; Gerald Wright (1 March 2001). "Tearns Without Uniforms: The Nonpartisan Ballot in State and Local Elections". Political Research Quarterly. 54 (1): 7–30. doi:10.1177/106591290105400101. S2CID 17440529.

- Dickerson, M. O. (1992). Whose North?: Political Change, Political Development, and Self-government in the Northwest Territories. University of British Columbia Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0774804189.

- Northup, Nancy (December 1987). "Local Nonpartisan Elections, Political Parties and the First Amendment". Columbia Law Review. 87 (7): 1677–1701. doi:10.2307/1122744. JSTOR 1122744.

- Steven Levitsky; Maxwell A. Cameron (19 December 2008). "Democracy Without Parties? Political Parties and Regime Change in Fujimori's Peru". Latin American Politics and Society. 45 (3): 1–33. doi:10.1111/j.1548-2456.2003.tb00248.x. S2CID 153626617.

- "Freedom in the World 2020: Cuba". Freedom House. 2020. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- Staff writer (30 June 2015). "China's Communist Party membership tops entire population of Germany". South China Morning Post. SCMP Group. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- Cha, Victor; Hwang, Balbina (2009). "Government and Politics". In Worden, Robert (ed.). North Korea: a Country Study (5th ed.). Federal Research Division. Library of Congress. p. 214. ISBN 978-1598044683.

- Clemens, Walter C. Jr. (2016). North Korea and the World. University Press of Kentucky. p. 5. ISBN 978-0813167466.

- Mickey, Robert (2015). Paths Out of Dixie: The Democratization of Authoritarian Enclaves in America's Deep South, 1944–1972. Princeton University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0691149639.

- Arend Lijphart; Don Aitkin (1994). Electoral Systems and Party Systems: A Study of Twenty-seven Democracies, 1945–1990. Oxford University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0198280545.

- Cohen, Alexander (2 March 2020). "The two-party system is here to stay". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 14 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- Coppedge, Michael (1 October 1998). "The Dynamic Diversity of Latin American Party Systems". Party Politics. 4 (4): 547–568. doi:10.1177/1354068898004004007. S2CID 3276149.

- Cini, Michelle (2 December 2009). "A Divided Nation: Polarization and the Two-Party System in Malta". South European Society and Politics. 7 (1): 6–23. doi:10.1080/714004966. S2CID 154269904.

- Minion K. C. Morrison; Jae Woo Hong (December 2006). "Ghana's political parties: How ethno/regional variations sustain the national two-party system". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 44 (4): 623–647. doi:10.1017/S0022278X06002114. S2CID 154384854.

- James Loxton; Timothy Power (2 June 2020). "Introducing authoritarian diasporas: causes and consequences of authoritarian elite dispersion". Democratization. 28 (3): 465–483. doi:10.1080/13510347.2020.1866553. S2CID 232245480.

- Kornblith, Miriam (July 2013). "Latin America's Authoritarian Drift: Chavismo After Chávez?". Journal of Democracy. 24 (3): 47–61. doi:10.1353/jod.2013.0050. S2CID 36800728.

- William Roberts Clark; Matt Golder (August 2006). "Rehabilitating Duverger's Theory: Testing the Mechanical and Strategic Modifying Effects of Electoral Laws". Comparative Political Studies. 39 (6): 679–708. doi:10.1177/0010414005278420. S2CID 154525800.

- Ferree, Karen E.; Powell, G. Bingham; Scheiner, Ethan (May 2014). "Context, Electoral Rules, and Party Systems". Annual Review of Political Science. 17: 421–439. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-102512-195419.

- Blake, Aaron (27 April 2016). "Why are there only two parties in American politics?". The Washington Post. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- Disch, Lisa Jane; Shapiro, Robert Y. (2002). The Tyranny of the Two-Party System. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231110358.

- Sartori, Giovanni (2005). "The overall framework". Parties and Party Systems: A Framework for Analysis. European Consortium for Political Research Press. pp. 243–2281. ISBN 0954796616.

- Stephen P. Nicholson; Christopher J. Carman; Chelsea M. Coe; Aidan Feeney; Balázs Fehér; Brett K. Hayes; Christopher Kam; Jeffrey A. Karp; Gergo Vaczi; Evan Heit (13 February 2018). "The Nature of Party Categories in Two‐Party and Multiparty Systems". Advances in Political Psychology. 39 (S1): 279–304. doi:10.1111/pops.12486.

- Anthony Heath; Siana Glouharova; Oliver Heath (2005). "India: Two‐Party Contests within a Multiparty System". In Michael Gallagher; Paul Mitchell (eds.). The Politics of Electoral Systems. Oxford University Press. pp. 137–156. doi:10.1093/0199257566.003.0007. ISBN 978-0199257560.

- A. Farid Wadjdi; Mistiani; Nebula F. Hasani (2020). "The Multi-Party System in Indonesia: Reviewing the Number of Electoral Parties from the Aspects of the National Defense and Security". Journal of Social and Political Sciences. 3 (3): 711–724. doi:10.31014/aior.1991.03.03.204. S2CID 224991370.

- Xiang Wu; Salman Ali (25 July 2020). "The Novel Changes in Pakistan's Party Politics: Analysis of Causes and Impacts". Chinese Political Science Review. 5 (4): 513–533. doi:10.1007/s41111-020-00156-z. S2CID 220833554.

- Marcondes de Freitas, Andréa. "Governmental Coalitions in Multiparty Presidentialism: The Brazilian Case (1988–2011)" (PDF). Universidade de São Paulo. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- Dodd, Lawrence C. (September 1974). "Party Coalitions in Multiparty Parliaments: A Game-Theoretic Analysis". The American Political Science Review. 68 (3): 1093–1117. doi:10.2307/1959150. JSTOR 1959150. S2CID 147014497.

- Carbone, Giovanni M. (November 2003). "Developing Multi-Party Politics: Stability and Change in Ghana and Mozambique" (PDF). Crisis States Programme Working Paper Series. 1 (36). Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- Michalik, Susanne (2015). Multiparty Elections in Authoritarian Regimes. p. 1. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-09511-6_1. ISBN 978-3-658-09510-9.

- Drutman, Lee (19 October 2019). "Let a Thousand Parties Bloom". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 13 February 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- Rosenfeld, Sam (14 April 2020). "It Takes Three (or More)". Boston Review. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- Malachova, Anastasija (21 November 2012). "Does a Multi-party System Lead to "More" Democracy?". E-International Relations. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- "Africans increasingly support multiparty democracy, but trust in political parties remains low". Afrobarometer. 18 June 2018. Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- Donovan, Todd; Parry, Janine A.; Bowler, Shaun (March 2005). "O Other, Where Art Thou? Support for Multiparty Politics in the United States". Social Science Quarterly. 86 (1): 147–159. doi:10.1111/j.0038-4941.2005.00295.x.

- Gideon Rahat; Reuven Y. Hazan (2005). "Israel: The Politics of an Extreme Electoral System". In Michael Gallagher; Paul Mitchell (eds.). The Politics of Electoral Systems. Oxford University Press. pp. 333–351. doi:10.1093/0199257566.001.0001. ISBN 978-0199257560.

- Raunio, Tapio (2005). "Finland: One Hundred Years of Quietude". In Michael Gallagher; Paul Mitchell (eds.). The Politics of Electoral Systems. Oxford University Press. p. 486. doi:10.1093/0199257566.001.0001. ISBN 978-0199257560.

- Drutman, Lee (19 October 2019). "Let a thousand parties bloom". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- Francis, Darrell (13 July 2016). "Why the Two-Party System Isn't as Broken as You May Think". Observer. Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- Epstein, Leon D. (March 1964). "A Comparative Study of Canadian Parties". The American Political Science Review. 58 (1): 46–59. doi:10.2307/1952754. JSTOR 1952754. S2CID 145086350.

- Basham, Patrick (2008). "Political Parties". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; Cato Institute. pp. 379–380. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n233. ISBN 978-1412965804. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- Archana Chaudhary; Jeanette Rodrigues (11 March 2019). "Why India's Election Is Among the World's Most Expensive". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- "2020 election to cost $14 billion, blowing away spending records". OpenSecrets. 28 October 2020. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- Justin Fisher; Todd A. Eisenstadt (1 November 2004). "Introduction: Comparative Party Finance: What is to be Done?". Party Politics. 10 (6): 619–626. doi:10.1177/1354068804046910. S2CID 144721738.

- Alexander, Brad (June 2005). "Good Money and Bad Money: Do Funding Sources Affect Electoral Outcomes?". Political Research Quarterly. 58 (2): 353–358. doi:10.2307/3595635. JSTOR 3595635.

- Levush, Ruth (March 2016). "Regulation of Campaign Finance and Free Advertising". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- "Are there provisions for direct public funding to political parties?". International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- "Report of the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters". Parliament of Australia. 9 December 2011. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- Meitzner, Marcus (August 2007). "Party Financing in Post-Soeharto Indonesia: Between State Subsidies and Political Corruption". Contemporary Southeast Asia. 29 (2): 238–263. doi:10.1355/cs29-2b. JSTOR 25798830. S2CID 154173938.

- Scarrow, Susan E. (15 June 2007). "Political Finance in Comparative Perspective". Annual Review of Political Science. 10: 193–210. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.080505.100115.

- Corstange, Daniel (2016). The Price of a Vote in the Middle East: Clientelism and Communal Politics in Lebanon and Yemen. Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-1107106673.

- Cruz, Cesi (7 August 2018). "Social Networks and the Targeting of Vote Buying". Comparative Political Studies. 52 (3): 382–411. doi:10.1177/0010414018784062. S2CID 158712487.

- Chris W. Bonneau; Damon M. Cann (October 2011). "Campaign Spending, Diminishing Marginal Returns, and Campaign Finance Restrictions in Judicial Elections". The Journal of Politics. 73 (4): 1267–1280. doi:10.1017/S0022381611000934.

- Horncastle, William (27 November 2020). "The 2020 election was the most expensive in history, but campaign spending does not always lead to success". London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- Hamada, Yukihiko (11 December 2018). "Let's talk about money: comparative perspectives on political finance regulations". International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- David L. Wiltse; Raymond J. La Raja; Dorie E. Apollonio (11 September 2019). "Typologies of Party Finance Systems: A Comparative Study of How Countries Regulate Party Finance and Their Institutional Foundations". Election Law Journal: Rules, Politics, and Policy. 18 (3): 243–261. doi:10.1089/elj.2018.0493. PMC 8189065. PMID 34113217.

- Atwill, Nicole (May 2009). "Campaign Finance: Comparative Summary". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- Manveena Suri; Oscar Holland (19 April 2019). "Ceiling fans, brooms and mangoes: The election symbols of India's political parties". CNN. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- "Understanding Political Color Designations". Gremillion Consulting. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- Enninful, Ebenezer Kofi (November 2012). "The Symbolism of Ghanaian Political Parties and their Impact on the Electorates" (PDF). Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- Malasig, Jeline (16 May 2018). "Can you paint with all the colors of politics?". InterAksyon. Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- Johnson, Ian P. (20 November 2017). "Germany's colorful coalition shorthand". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- Rost, Lisa Charlotte (28 August 2018). "Election reporting: Which color for which party?". Datawrapper. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- Farhi, Paul (2 November 2004), "Elephants Are Red, Donkeys Are Blue", The Washington Post, archived from the original on 9 May 2008, retrieved 24 January 2021

- George, Jane (11 March 2013). "Greenland vote likely headed for a squeaker this March 12". Nunatsiaq News. Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- Finnis, Alex (10 September 2020). "Why Boris Johnson and MPs are wearing a wheat sheaf badge on their lapel: The campaign to support British farmers explained". i. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- "Agrarian Party of Russia". Flags of the World. 27 February 2014. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- "The Classical Symbol of Anarchism". Anarchism.net. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- "Disciplina: mando único: Partido Sindicalista". University of California, San Diego. 9 December 2014. Archived from the original on 16 February 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- Baillargeon, Normand (2013) [2008]. "Introduction". Order Without Power: An Introduction to Anarchism: History and Current Challenges. Translated by Mary Foster. New York: Seven Stories Press. ISBN 978-1-60980-472-5. Archived from the original on 1 June 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- "A quick history of the Circle-A". Rival LA. 10 June 2020. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- Ansolabehere, Stephen; Rodden, Jonathan; Snyder, James M. Jr. (2006). "Purple America". The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 20 (2): 97–118. doi:10.1257/jep.20.2.97.

- McLarty, Scott (2019). "Forget Red vs. Blue: The Paradigm for the 21st Century is Orange, Purple, and Green". United States Green Party. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- Witte, John (1993). Christianity and Democracy in Global Context. Westview Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0813318431.

- Klein, Sarah (April 2018). "Interview with Gerd Koenen: The Fading of a Political Colour". Goethe-Institut. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.