Republic P-47 Thunderbolt

The Republic P-47 Thunderbolt is a World War II-era fighter aircraft produced by the American aerospace company Republic Aviation from 1941 through 1945. Its primary armament was eight .50-caliber machine guns, and in the fighter-bomber ground-attack role it could carry 5-inch rockets or a bomb load of 2,500 lb (1,100 kg). When fully loaded, the P-47 weighed up to 8 tons, making it one of the heaviest fighters of the war.

| P-47 Thunderbolt | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| XP-47N flying over the Pacific during World War II | |

| Role | Fighter-bomber |

| Manufacturer | Republic Aviation |

| First flight | 6 May 1941 |

| Introduction | November 1942[1] |

| Retired | 1966 (Peruvian Air Force) |

| Primary users | United States Army Air Forces (historical) Royal Air Force (historical) French Air Force (historical) Peruvian Air Force (historical) |

| Produced | 1941–1945 |

| Number built | 15,636 |

| Variants | Republic XP-72 |

The Thunderbolt was effective as a short-to medium-range escort fighter in high-altitude air-to-air combat and ground attack in both the European and Pacific theaters. The P-47 was designed around the powerful Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp 18-cylinder radial engine, which also powered two U.S. Navy/U.S. Marine Corps fighters, the Grumman F6F Hellcat and the Vought F4U Corsair. An advanced turbosupercharger system ensured the aircraft's eventual dominance at high altitude, while also influencing its size and design.

The P-47 was one of the main United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) fighters of World War II, and also served with other Allied air forces, including those of France, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union. Mexican and Brazilian squadrons fighting alongside the USAAF also flew the P-47.

The armored cockpit was relatively roomy and comfortable and the bubble canopy introduced on the P-47D offered good visibility. Nicknamed the "Jug" owing to its appearance if stood on its nose, the P-47 was noted for its firepower, as well as its ability to resist battle damage and remain airworthy. A present-day U.S. ground-attack aircraft, the Fairchild Republic A-10 Thunderbolt II, takes its name from the P-47.[Note 1]

Development

The P-47 Thunderbolt was designed by Alexander Kartveli, a man of Georgian descent. It was to replace the Seversky P-35 developed earlier by a Russian immigrant named Alexander P. de Seversky.[Note 2] Both had fled from their homeland, Tbilisi, Georgia, to escape the Bolsheviks.[4][Note 3] In 1939, Republic Aviation designed the AP-4 demonstrator powered by a Pratt & Whitney R-1830 radial engine with a belly-mounted turbocharger. A small number of Republic P-43 Lancers was built, but Republic had been working on an improved P-44 Rocket with a more powerful engine, as well as on the AP-10 fighter design. The latter was a lightweight aircraft powered by the Allison V-1710 liquid-cooled V-12 engine and armed with two .50 in (12.7 mm) M2 Browning machine guns mounted in the nose and four .30 in (7.62 mm) M1919 Browning machine guns mounted in the wings.[6] The United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) backed the project and gave it the designation XP-47.

In the spring of 1940, Republic and the USAAC concluded that the XP-44 and the XP-47 were inferior to Luftwaffe fighters. Republic tried to improve the design, proposing the XP-47A, but this failed. Kartveli then designed a much larger fighter, which was offered to the USAAC in June 1940. The Air Corps ordered a prototype in September as the XP-47B. The XP-47A, which had little in common with the new design, was abandoned. The XP-47B was of all-metal construction (except for the fabric-covered tail control surfaces) with elliptical wings, with a straight leading edge that was slightly swept back. The air-conditioned cockpit was roomy, and the pilot's seat was comfortable—"like a lounge chair", as one pilot later put it. The canopy doors hinged upward. Main and auxiliary self-sealing fuel tanks were placed under the cockpit, giving a total fuel capacity of 305 US gal (254 imp gal; 1,155 l).

Power came from a Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp two-row, 18-cylinder radial engine producing 2,000 hp (1,500 kW) — the same engine that powered the prototype Vought XF4U-1 fighter to just over 400 mph (640 km/h) in October 1940—with the Double Wasp on the XP-47B turning a four-bladed Curtiss Electric constant-speed propeller of 146 in (3.7 m) in diameter. The loss of the AP-4 prototype to an engine fire ended Kartveli's experiments with tight-fitting cowlings, so the engine was placed in a broad cowling that opened at the front in a "horse collar"-shaped ellipse. The cowling admitted cooling air for the engine, left and right oil coolers, and the turbosupercharger intercooler system. The engine exhaust gases were routed into a pair of wastegate-equipped pipes that ran along each side of the cockpit to drive the turbosupercharger turbine at the bottom of the fuselage, about halfway between cockpit and tail. At full power, the pipes glowed red at their forward ends and the turbine spun at 21,300 rpm.[7] The complicated turbosupercharger system with its ductwork gave the XP-47B a deep fuselage, and the wings had to be mounted in a relatively high position. This was difficult, since long-legged main landing gear struts were needed to provide ground clearance for the enormous propeller. To reduce the size and weight of the undercarriage struts, and so wing-mounted machine guns could be fitted, each strut was fitted with a mechanism by which it telescoped out 9 in (23 cm) while it extended.

The XP-47B was very heavy compared with contemporary single-engined fighters, with an empty weight of 9,900 lb (4,500 kg), or 65% more than the YP-43. Kartveli said, "It will be a dinosaur, but it will be a dinosaur with good proportions".[8] The armament was eight .50-caliber (12.7 mm) "light-barrel" Browning AN/M2 machine guns, four in each wing. The guns were staggered to allow feeding from side-by-side ammunition boxes, each with 350 rounds. All eight guns gave the fighter a combined rate of fire around 100 rounds per second.[9]

The XP-47B first flew on 6 May 1941 with Lowry P. Brabham at the controls. Although minor problems arose, such as some cockpit smoke that turned out to be due to an oil drip, the aircraft proved impressive in its early trials. It was lost in an accident on 8 August 1942, but before that mishap, the prototype had achieved a level speed of 412 mph (663 km/h) at 25,800 ft (7,900 m) altitude and had demonstrated a climb from sea level to 15,000 ft (4,600 m) in five minutes.[10]

Though the XP-47B had its share of teething troubles, the newly reorganized United States Army Air Forces placed an order for 171 production aircraft, the first being delivered in December 1941.

Operational history

US service

By the end of 1942, P-47Cs were sent to England for combat operations. The initial Thunderbolt flyers, 56th Fighter Group, was sent overseas to join the 8th Air Force. As the P-47 Thunderbolt worked up to operational status, it gained a nickname: "Jug" (because its profile was similar to that of a common milk jug of the time).[Note 4] Two fighter groups (FGs) already stationed in England began introducing the Jugs in January 1943 - the Spitfire-flying 4th Fighter Group, a unit built around a core of experienced American pilots who had flown in the RAF Eagle Squadrons prior to the US entry in the war; and the 78th Fighter Group, formerly flying P-38 Lightnings.

Beginning in January 1943, Thunderbolt fighters were sent to the joint Army Air Forces – civilian Millville Airport in Millville, New Jersey, to train civilian and military pilots.

The first P-47 combat mission took place 10 March 1943 when the 4th FG took their aircraft on a fighter sweep over France. The mission was a failure due to radio malfunctions. All P-47s were refitted with British radios, and missions resumed 8 April. The first P-47 air combat took place 15 April with Major Don Blakeslee of the 4th FG scoring the Thunderbolt's first air victory (against a Focke-Wulf Fw 190).

By mid-1943, the Jug was also in service with the 12th Air Force in Italy[13] and against the Japanese in the Pacific, with the 348th Fighter Group flying missions out of Port Moresby, New Guinea. By 1944, the Thunderbolt was in combat with the USAAF in all its operational theaters except Alaska.

Luftwaffe ace Heinz Bär said that the P-47 "could absorb an astounding amount of lead [from shooting at it] and had to be handled very carefully".[14] Although the North American P-51 Mustang replaced the P-47 in the long-range escort role in Europe, the Thunderbolt still ended the war with 3,752 air-to-air kills claimed in over 746,000 sorties of all types, at the cost of 3,499 P-47s to all causes in combat.[15] By the end of the war, the 56th FG was the only 8th Air Force unit still flying the P-47, by preference, instead of the P-51. The unit claimed 677-1/2 air victories and 311 ground kills, at the cost of 128 aircraft.[16] Lieutenant Colonel Francis S. Gabreski scored 28 victories,[17] Captain Robert S. Johnson scored 27 (with one unconfirmed probable kill leading to some giving his tally as 28),[18] and 56th FG Commanding Officer Colonel Hubert Zemke scored 17.75 kills.[Note 5] Despite being the sole remaining P-47 group in the 8th Air Force, the 56th FG remained its top-scoring group in aerial victories throughout the war.

With increases in fuel capacity as the type was refined, the range of escort missions over Europe steadily increased until the P-47 was able to accompany bombers in raids all the way into Germany. On the way back from the raids, pilots shot up ground targets of opportunity, and also used belly shackles to carry bombs on short-range missions, which led to the realization that the P-47 could perform a dual-function on escort missions as a fighter-bomber. Even with its complicated turbosupercharger system, its sturdy airframe and tough radial engine could absorb significant damage and still return home.

The P-47 gradually became the USAAF's primary fighter-bomber; by late 1943, early versions of the P-47D carried 500 lb (230 kg) bombs underneath their bellies, midproduction versions of the P-47D could carry 1,000 lb (450 kg) bombs and M8 4.5 in (115 mm) rockets under their wings or from the last version of the P-47D in 1944, 5 in (130 mm) High velocity aircraft rockets (HVARs, also known as "Holy Moses"). From D-Day until VE day, Thunderbolt pilots claimed to have destroyed 86,000 railroad cars, 9,000 locomotives, 6,000 armored fighting vehicles, and 68,000 trucks.[20] During Operation Cobra, in the vicinity of Roncey, P-47 Thunderbolts of the 405th Fighter group destroyed a German column of 122 tanks, 259 other vehicles, and 11 artillery pieces.[21][22]

Postwar service

With the end of World War II, orders for 5,934 were cancelled.[23] The P-47 continued serving with the USAAF through 1947, the USAAF Strategic Air Command from 1946 through 1947, the active-duty United States Air Force (USAF) until 1949, and with the Air National Guard (ANG) until 1953, receiving the designation F-47 in 1948. F-47s served as spotters for rescue aircraft such as the OA-10 Catalina and Boeing B-17H. In 1950, F-47 Thunderbolts were used to suppress the declaration of independence in Puerto Rico by nationalists during the Jayuya Uprising.

The F-47 was not deployed to Korea for the Korean War. The North American F-51 Mustang was used by the USAF, mainly in the close air-support role. Since the Mustang was more vulnerable to being shot down, (and many were lost to antiaircraft fire), some World War II P-47 pilots suggested the more durable Thunderbolt should have been sent to Korea in the Mustang's place. The F-51D was available in greater numbers, though, in the USAF and ANG inventories.[24] Due to continued postwar service with U.S. military and foreign operators, a number of Thunderbolts have survived to the present day, and a few are still flying. The Cuban Air Force took delivery of 29 ex-USAF airframes and spares. By the late 1950s, the F-47 was considered obsolete, but was well suited for counter-insurgency tasks.

P-47 in Allied service

P-47s were operated by several Allied air arms during World War II. The RAF received 240 razorback P-47Ds, which they designated Thunderbolt Mark I, and 590 bubbletop P-47D-25s, designated Thunderbolt Mark IIs. With no need for another high-altitude fighter, the RAF adapted their Thunderbolts for ground attack, a task for which the type was well suited. Once the Thunderbolts were cleared for use in 1944, they were used against the Japanese in Burma by 16 RAF squadrons of the South East Asia Command from India. Operations with army support (operating as "cab ranks" to be called in when needed), attacks on enemy airfields and lines of communication, and escort sorties. They proved devastating in tandem with Spitfires during the Japanese breakout attempt at the Sittang Bend in the final months of the war. The Thunderbolts were armed with three 500 lb (230 kg) bombs or, in some cases, British "60 lb (27 kg)" RP-3 rocket projectiles. Long-range fuel tanks[25] gave five hours of endurance. Thunderbolts flew escort for RAF Liberators in the bombing of Rangoon. Thunderbolts remained in RAF service until October 1946. Postwar RAF Thunderbolts were used in support of the Dutch attempts to reassert control of Batavia. Those squadrons not disbanded outright after the war re-equipped with British-built aircraft such as the Hawker Tempest.[26]

During the Italian campaign, the "1º Grupo de Caça da Força Aérea Brasileira" (Brazilian Air Force 1st Fighter Squadron) flew a total of 48 P-47Ds in combat (of a total of 67 received, 19 of which were backup aircraft). This unit flew a total of 445 missions from November 1944 to May 1945 over northern Italy and Central Europe, with 15 P-47s lost to German flak and five pilots being killed in action.[27] In the early 1980s, this unit was awarded the "Presidential Unit Citation" by the American government in recognition for its achievements in World War II.[28]

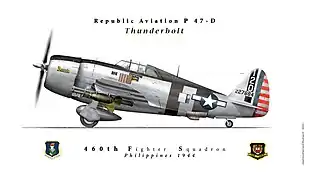

From March 1945 to the end of the war in the Pacific—as Mexico had declared war on the Axis on May 22, 1942—the Mexican Escuadrón Aéreo de Pelea 201 (201st Fighter Squadron) operated P-47Ds as part of the U.S. 5th Air Force in the Philippines. In 791 sorties against Japanese forces, the 201st lost no pilots or aircraft to enemy action.[29]

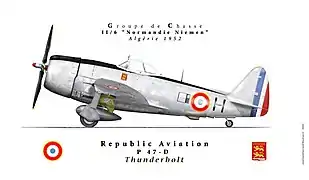

The Free French Air Forces received 446 P-47Ds from 1943. These aircraft saw extensive action in France and Germany and again in the 1950s during the Algerian War of Independence.

After World War II, the Italian Air Force (AMI) received 75 P-47D-25s sent to 5˚ Stormo, and 99 to the 51˚. These machines were delivered between 1947 and 1950. However, they were not well liked, as the Italian pilots were used to much lighter aircraft and found the controls too heavy. Nevertheless, the stability, payload, and high speed were appreciated. Most importantly, the P-47 served as an excellent transition platform to heavier jet fighters, including the F-84 Thunderjet, starting in 1953.[30]

The type was provided to many Latin American air forces, some of which operated it into the 1960s. Small numbers of P-47s were also provided to China, Iran, Turkey, and Yugoslavia.

In Soviet service

The U.S. sent 203 P-47Ds to the Soviet Union.[31] In mid-1943, the Soviet high command showed an interest in the P-47B. Three P-47D-10-REs were ferried to the Soviet Air Forces (VVS) via Alaska in March 1944. Two of them were tested in April–May 1944. Test pilot Aleksey N. Grinchik noted the spacious cockpit with good ventilation and a good all-around view. He found it easy to fly and stable upon take-off and landing, but it showed excessive rolling stability and poor directional stability. Soviet engineers disassembled the third aircraft to examine its construction. They appreciated the high production standards and rational design well-suited to mass production, and the high reliability of the hard-hitting Browning machine guns. With its high service ceiling, the P-47 was superior to fighters operating on the Eastern front, yielding a higher speed above 30,000 feet (9,100 m). The Yakovlev Yak-9, Lavochkin La-5FN, Messerschmitt Bf 109G, and Focke-Wulf Fw 190A outperformed the early model P-47 at low and medium altitude, where the P-47 had poor acceleration and performed aerobatics rather reluctantly. In mid-1944, 200 P-47D-22-REs and P-47D-27-REs were ferried to the USSR via Iraq and Iran. Many were sent to training units. Less than half reached operational units, and they were rarely used in combat.[32] The fighters were assigned to high-altitude air defense over major cities in rear areas. Unlike their Western counterparts, the VVS made little use of the P-47 as a ground-attack aircraft, depending, instead, on their own widely produced—with 36,183 examples built during the war—special-purpose, armored ground-attack aircraft, the Ilyushin Il-2. At the end of the war, Soviet units held 188 P-47s.[32]

In German service

The Luftwaffe operated at least one captured P-47. In poor weather on 7 November 1943, while flying a P-47D-2-RA on a bomber escort mission, 2nd Lt. William E. Roach of 358th Fighter Squadron, 355th Fighter Group made an emergency landing on a German airfield. Roach was imprisoned at Stalag Luft I. The Thunderbolt was given German markings.[33]

In Chinese/Taiwanese service

After World War II, the Chinese Nationalist Air Force received 102 P-47Ds used during the Chinese Civil War. The Chinese Communists captured five P-47Ds from the Chinese Nationalist forces. In 1948, the Chinese Nationalists employed 70 P-47Ds and 42 P-47Ns brought to Taiwan in 1952. P-47s were used extensively in aerial clashes over the Taiwan Strait between Nationalist and Communist aircraft.[34]

Flying the Thunderbolt

Aerial warfare

Initial response to the P-47 praised its dive speed and high-altitude performance, while criticizing its turning performance and rate of climb (particularly at low to medium altitudes). The turbosupercharger in the P-47 gave the powerplant its maximum power at 27,000 ft (8,200 m), and in the thin air above 30,000 ft (9,100 m), the Thunderbolt remained fast and nimble compared to other aircraft.[35]

The P-47 first saw action with the 4th Fighter Group, whose pilots were mainly drawn from the three British Eagle Squadrons, who had previously flown the British Spitfire Mark V, a much smaller and much more slender aircraft. At first, they viewed their new fighter with misgivings. It was huge; the British pilots joked that a Thunderbolt pilot could defend himself from a Luftwaffe fighter by running around and hiding in the fuselage. Optimized for high-altitude work, the Thunderbolt had 5 feet (1.5 m) more wingspan, a quarter more wing area, about four times the fuselage volume, and nearly twice the weight of a Spitfire V.[36][37] One Thunderbolt pilot compared it to flying a bathtub around the sky. When his unit (4th Fighter Group) was equipped with Thunderbolts, ace Don Blakeslee said, referring to the P-47's vaunted ability to dive on its prey, "It ought to be able to dive. It certainly can't climb."[38] (Blakeslee's early-model P-47C had not been fitted with the new paddle blade propeller). The 4th Fighter Group's commander hated the P-47, and his prejudices filtered down to the group's pilots; the 4th had the fewest kills of any of the first three P-47 squadrons in Europe.[37]

U.S. ace Jim Goodson, who had flown Spitfires with the RAF and flew a P-47 in 1943, at first shared the skepticism of other pilots for their "seven-ton milk bottles", but Goodson learned to appreciate the P-47's potential:

There were many U.S. pilots who preferred the P-47 to anything else; they do not agree that the (Fw) 190 held an overall edge against it.[39]

The P-47's initial success in combat was primarily due to tactics, using rolls (the P-47 had an excellent roll rate) and energy-saving dive and zoom climbs from high altitude to outmaneuver German fighters. Both the Bf 109 and Fw 190 could, like the Spitfire, out-turn and out-climb the early model P-47s at low to medium altitudes, since these early P-47s had mediocre climb performance due to the lack of paddle-blade propellers.[40] The arrival of the new Curtiss paddle-blade propeller in early 1944 significantly increased climb rate at lower altitudes and came as a surprise to German pilots, who had resorted to steep climbs to evade pursuit by the P-47.[37] Some P-47 pilots claimed to have broken the sound barrier in steep dives, but later research revealed that because of the pressure buildup inside the pitot tube at high speeds, airspeed readings became unpredictably exaggerated. As P-47s were able to out-dive enemy fighter planes attempting to escape by such a maneuver, German pilots gradually learned to avoid diving away from a P-47. Kurt Bühligen, a high-scoring German fighter ace with 112 victories, recalled:

The P-47 was very heavy, too heavy for some maneuvers. We would see it coming from behind, and pull up fast, and the P-47 couldn't follow and we came around and got on its tail in this way.[41]

Other positive attributes included the P-47's ruggedness; its radial piston engine had a high tolerance for damage compared to liquid-cooled engines, while its large size meant it could sustain a large amount of damage and still be able to get its pilot back to base.[Note 6] [42] With eight .50 in (12.7 mm) machine guns, the P-47 carried more firepower than other single-engined American fighters. P-47 pilots claimed 20 Luftwaffe Messerschmitt Me 262 jet fighters and four Arado Ar 234 jet bombers in aerial combat.

In the Pacific, Colonel Neel E. Kearby of the Fifth Air Force claimed 22 Japanese aircraft and was awarded the Medal of Honor for an action in which he downed six enemy fighters on a single mission. He was shot down and killed over Wewak in March 1944.[43]

Ground attack role

The P-47 proved to be a formidable fighter-bomber due to its good armament, heavy bomb load, and ability to survive enemy fire. The P-47's survivability was due in part to its radial piston engine, which unlike comparable liquid-cooled engines, had a high tolerance for damage.[44] The Thunderbolt's eight .50 in (12.7 mm) machine guns were capable against lightly armored targets, although less so than cannon-armed aircraft of the day. In a ground-attack role, the armor-piercing, armor-piercing incendiary, and armor-piercing incendiary tracer ammunition proved useful in penetrating thin-skinned and lightly armored German vehicles and causing their fuel tanks to explode, as well as occasionally damaging some types of enemy armored fighting vehicles (AFVs).[45]

P-47 pilots frequently carried two 500 lb (230 kg) bombs, using skip bombing techniques for difficult targets (skipping bombs into railroad tunnels to destroy hidden enemy trains was a favorite tactic).[46] The adoption of the triple-tube M10 rocket launcher[47] with M8 high-explosive 4.5 in (110 mm) rockets (each with an explosive force similar to a 105 mm artillery shell)—much as the RAF's Hawker Typhoon gained when first fitted with its own two quartets of underwing RP-3 rockets for the same purposes—significantly increased the P-47's ground attack capability.[48] Late in the war, the P-47 was retrofitted with more powerful 5 in (130 mm) HVAR rockets.

Operators

- Bolivian Air Force - acquired a single P-47D in 1949, but the aircraft was never flown by the Bolivian Air Force and was used as an instructional airframe.[49]

- Brazilian Expeditionary Force, Brazilian Air Force[50][51][52][53][54]

- 85 units 1st Brazilian Fighter Group, 1944–1954

- Republic of China Air Force[57]

- Colombian Air Force (1947–1957)[57]

- Cuban Air Force (post-war)[57]

- Dominican Air Force (1952–1957)[58]

- Ecuadorian Air Force (1947–1959)[58]

- Free French Air Force[58]

- French Air Force[58]

- Imperial Iranian Air Force – 50 delivered 1948[58]

- Italian Air Force – 100 received 1950[59]

- Mexican Expeditionary Air Force

- Escuadrón 201[60]

- Fuerza Aerea de Nicaragua (provided by the CIA post 1954 action in Guatemala)[59]

- Peruvian Air Force (56 aircraft, July 1947 – 1963)[59]

- Portuguese Air Force (post-war)[61]

- Turkish Air Force – operated 180 P-47Ds from 1948 and 1954.[61]

- Venezuelan Air Force[61]

- Yugoslav Air Force (150 aircraft, 1952)[62]

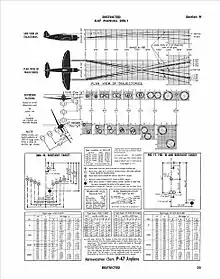

P47 D French Algeria 1952

P47 D French Algeria 1952 P47D 460th Fighter squadron Philippines 1944

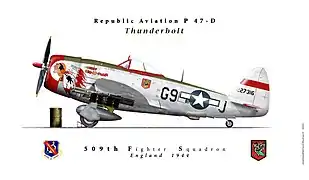

P47D 460th Fighter squadron Philippines 1944 P47D 509th Fighter squadron England 1944

P47D 509th Fighter squadron England 1944 P47D 334th Fighter Squadron England 1944

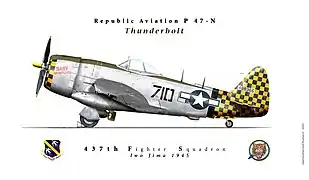

P47D 334th Fighter Squadron England 1944 P47N 437th fighter squadron Iwo Jima 1945

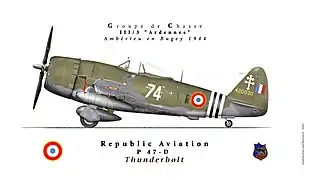

P47N 437th fighter squadron Iwo Jima 1945 P47D Groupe de chasse III/3 Ardennes 1944

P47D Groupe de chasse III/3 Ardennes 1944

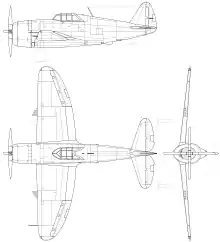

Specifications (P-47D-40 Thunderbolt)

Data from [63]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 36 ft 1.75 in (11.0173 m)

- Wingspan: 40 ft 9+5⁄16 in (12.429 m)

- Height: 14 ft 8+1⁄16 in (4.472 m)

- Airfoil: Seversky S-3[64]

- Empty weight: 10,000 lb (4,536 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 17,500 lb (7,938 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Pratt & Whitney R-2800-59 18-cylinder air-cooled radial piston engine, 2,000 hp (1,500 kW)

- Propellers: 4-bladed Curtiss Electric C542S constant-speed propeller, 13 ft 0 in (3.96 m) diameter

Performance

- Maximum speed: 426 mph (686 km/h, 370 kn) at 30,000 ft (9,100 m)

- Range: 1,030 mi (1,660 km, 900 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 42,000 ft (13,000 m)

Armament

- Eight .50 in (12.7 mm) M2 Browning machine guns (3400 rounds)

- Up to 2,500 lb (1,100 kg) of bombs

- Ten 5 in (127 mm) HVAR unguided rockets

In popular culture

.jpg.webp)

Broadcast radio interviews of several wartime P-47 pilots appear on the CD audiobook USAAF at War 1942–45, including an account by Lieutenant J.K. Dowling of ground support operations around Cherbourg in June 1944, and a group of four pilots from the 362nd Fighter Wing (Ninth Air Force) in conversation at their mess in Rouvres, France on 24 December 1944 during the Battle of the Bulge.[65]

Laughter and Tears,[66] by Captain George Rarey, a posthumous publication of letters and sketches from a pilot in the 379th Air group flying P-47s based in England.

In the post-war era one Air National Guard Thunderbolt plowed into the second story of a factory, shearing off its wings, with the crumpled fuselage eventually coming to rest inside the building; the pilot walked away alive.[67]

The Czech composer Bohuslav Martinů, while in residence in the US wrote an orchestral scherzo in 1945 entitled P-47 Thunderbolt (H 309) in tribute to the aircraft and its role in World War II.

Other media include Thunderbolt, a 1947 color documentary film directed by John Sturges and William Wyler, featuring James Stewart and Lloyd Bridges and narrated by Robert Lowery.[68] The film Fighter Squadron (1948) depicts a P-47 Thunderbolt unit.[69]

"Thunderbolts: The Conquest of the Reich", a 2001 television documentary presented by the History Channel. Director Lawrence Bond depicted the last months of World War II over Germany as told by four P-47 pilots of the 362nd Fighter Group using original, all color 1945 footage. The P-47 Thunderbolt was the subject of an episode of the World's Deadliest Aircraft series broadcast by the Military Channel.

Lieutenant Colonel Robert Samuel Johnson collaborated with aviation author Martin Caidin to write his autobiographical story of the 56th Fighter Group, Thunderbolt!, in 1958. Johnson scored 27 kills in the P-47 while flying with the 56th Fighter Group.

In 2015, it was named the state aircraft of Indiana due to its Evansville roots.[70]

See also

Related development

- Seversky SEV-3

- Seversky P-35

- Republic P-43

- Republic XP-72

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- Grumman F6F Hellcat

- Vought F4U Corsair

- Focke-Wulf Fw 190

- Hawker Typhoon

- Hawker Tempest

- Mitsubishi A7M

- North American P-51 Mustang

Related lists

- List of aircraft of World War II

- List of military aircraft of the United States

- List of fighter aircraft

References

Notes

- Fairchild Republic was the most recent incarnation of the original Republic aerospace company, now considered defunct.[2]

- The P-47 can trace its lineage back to earlier Seversky designs: P-35, XP-41, P-43, and the unbuilt P-44.[3]

- After a change in the board of directors, Alexander P. de Seversky was removed from the newly reorganized Republic Aviation company, with former Managing Director Wallace Kellett taking over as CEO.[5]

- Historians argue that the nickname "Jug" was short for "Juggernaut" when aviators began using the longer word as an alternate nickname.[11] Another nickname that was used for the Thunderbolt was "T-bolt".[12]

- Zemke flew a P-38 for three of his kills.[19]

- Quentin C. Aanenson documented his experiences flying the Thunderbolt on D-Day and subsequently in the European Theater in his documentary, A Fighter Pilot's Story (also released as Dogfight.).

Citations

- "Republic P-47 Thunderbolt". aviation-history. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- Rummerman, Judy. "Fairchild Republic." Archived 2011-10-14 at the Wayback Machine Centennial of Flight Commission, 2003. Retrieved: 7 August 2011.

- Dorr and Donald 1990, pp. 84–85, 88.

- Dwyer, Larry. "Republic P-47 Thunderbolt." Aviation History Online Museum, 11 November 2010.

- "Alexander de Seversky, Russian Ace of World War One, Aircraft Designer & Founder of Republic Aviation." acepilots.com, 2003. Retrieved: 16 May 2009.

- "Republic XP-47B Thunderbolt". www.joebaugher.com. Retrieved 2020-06-02.

- "The Turbosupercharger and the Airplane Power Plant." General Electric, January, 1943.

- "P-47 Thunderbolt". TopFighters.com. Retrieved: 12 July 2006.

- Masefield, Peter. "First Analysis of the Thunderbolt." Flying, August 1943, p. 190.

- Green 1961, p. 173.

- Graff 2007, p. 53.

- Air Force Association 1998, p. 110.

- Bernstein, Jonathan (2012). "1". P-47 Thunderbolt Units of the Twelfth Air Force. Botley, Oxfordshire: Osprey Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 9781849086721. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- Rymaszewski, Michael (July 1994). "Playing Your Aces". Computer Gaming World. pp. 101–105.

- "Republic P-47D Thunderbolt". Archived 2007-03-24 at the Wayback Machine Museum of Flight. Retrieved: 12 July 2006.

- "8th Air Force 56th FG." Archived 2006-06-12 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II, 18 June 2004. Retrieved: 14 July 2006.

- "Francis S. 'Gabby' Gabreski". Archived 2008-05-23 at the Wayback Machine USAF Air University, Maxwell-Gunter AFB, 17 April 2006. Retrieved: 14 July 2006.

- Rose, Scott. "Robert S. Johnson". Warbirds Resource Group, 11 June 2006. Retrieved: 14 July 2006.

- "Col. Hubert 'Hub' Zemke." Acepilots.com, 29 July 2003. Retrieved: 14 July 2006.

- "Republic P-47D-30-RA Thunderbolt (Long Description)." Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved: 19 February 2017.

- "405th Fighter Group (USAAF)". www.historyofwar.org. Retrieved 2022-02-07.

- Zaloga p.65

- Berliner 2011, p. 20.

- "Air Power History". goliath.ecnext.com. Retrieved: 06 January 2010, via Internet Archive.

- "RAF Thunderbolts", Flight: 600 (photo caption), 7 December 1944

- Republic P-47D Thunderbolt II, RAF Museum

- Dias de Cunha, Rudnei. "Republic P-47 Thunderbolt". www.rudnei.cunha.nom.br. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- "Sinopse e Créditos". 10 December 2004. Archived from the original on 10 December 2004. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- Velasco, E. Alfonso, Jr. "Aztec Eagle – P-47D of the Mexican Expeditionary Air Force". IPMS Stockholm, 9 January 2006. Retrieved: 14 July 2006.

- Sgarlato 2005.

- Hardesty 1991, p. 253.

- Gordon 2008, p. 449.

- "1/72 Revell P-47 Thunderbolt by Robert R. Heeps".

- Merriam, Ray (2017). World War 2 in Review: Republic P-47 Thunderbolt. New York: Merriam Press. ISBN 9781365884856. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Bergerud 2000, pp. 269–70.

- Spick 1983, p. 96.

- Caldwell 2007, p. 89.

- Sims, Edward H. American Aces of World War II, London: Macdonald, 1958.

- Sims 1980, pp. 160–61.

- Jordan, C. C. "Pushing The Envelope With Test Pilot Herb Fisher". Planes and Pilots of WW2, 2000. Retrieved: 22 July 2011.

- Sims 1980, pp. 134–35.

- Hallion, Richard (August 15, 2014). D-Day 1944 – Air Power Over The Normandy Beaches And Beyond. Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78289887-0. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- "Colonel Neel Earnest Kearby". Archived 2004-10-17 at the Wayback Machine Air Force History, Air Force Historical Studies Office, 20 January 2004. Retrieved: 14 July 2006.

- Hallion, Richard (August 15, 2014). D-Day 1944 – Air Power Over The Normandy Beaches And Beyond. Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78289887-0. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- Barnes 1989, p. 432.

- "Achtung! Jabos! The Story of the IX TAC." Stars & Stripes, U.S. Army, 1944.

- Page 4 illustration of M10 triple-tube launcher, iBiblio.

- Dunn, Carle E. (LTC). "Army Aviation and Firepower". Archived 2008-12-23 at the Wayback Machine Army, May 2000. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- Hagedorn 1991, p. 37.

- "P-47 Thunderbolt/42-19663." Warbirds Resource Group. Retrieved: 21 April 2011.

- "P-47 Thunderbolt/42-26450." Warbirds Resource Group. Retrieved: 21 April 2011.

- "P-47 Thunderbolt/42-26757." Warbirds Resource Group. Retrieved: 21 April 2011.

- "P-47 Thunderbolt/42-26762." Warbirds Resource Group. Retrieved: 21 April 2011.

- "P-47 Thunderbolt/45-49151." Warbirds Resource Group. Retrieved: 21 April 2011.

- "P-47 Thunderbolt/45-49219." Warbirds Resource Group. Retrieved: 21 April 2011.

- "P-47 Thunderbolt/45-49509." Warbirds Resource Group. Retrieved: 21 April 2011.

- Lake 2002, p. 162.

- Lake 2002, p. 163.

- Lake 2002, p. 164.

- Klemen, L. "201st Mexican Fighter Squadron." Archived 2011-07-26 at the Wayback Machine The Netherlands East Indies 1941–1942. Retrieved: 26 April 2015.

- Lake 2002, p. 165.

- "Republic F-47D-40-RE Thunderbolt". Aeronautical Museum-Belgrade. Retrieved: 23 February 2014.

- Davis, Larry (1984). P-47 Thunderbolt in Action. Squadron/Signal Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-89747-161-X.

- Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- Hayward, James. "USAAF at War (1942-45): Audiobook CD on CD41 label." ltmrecordings.com. Retrieved: 6 March 2012.

- Rarey, George (June 1996). Laughter and Tears: A Combat Pilot's Sketchbook of World War II Squadron Life. ISBN 1-56550-057-1.

- Unbreakable World War II aircraft that were shot to hell—and came back. By Cory Graff Air & Space Magazine

- "Thunderbolt (1947)". imdb.com. Retrieved: 21 November 2009.

- "Fighter Squadron (1948)". imdb.com. Retrieved: 21 November 2009.

- "P-47 Thunderbolt Named Official State Aircraft of Indiana". WFIE-TV. June 24, 2015. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

Bibliography

- Air Force Fifty. Nashville, Tennessee: Turner Publishing (Air Force Association), 1998 (limited edition). ISBN 1-56311-409-7.

- Barnes, Frank C. Cartridges of the World. Fairfield, Ohio: DBI Books, 1989. ISBN 978-0-87349-605-6.

- Berliner, Don. Surviving Fighter Aircraft of World War Two: Fighters. London: Pen & Sword Aviation, 2011. ISBN 978-1-8488-4265-6.

- Bergerud, Eric M. Fire in the Sky. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 2000. ISBN 0-8133-3869-7.

- Bodie, Warren M. Republic's P-47 Thunderbolt: From Seversky to Victory. Hiawassee, Georgia: Widewing Publications, 1994. ISBN 0-9629359-1-3.

- Bull, Steven. Encyclopedia of Military Technology and Innovation. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood, 2004. ISBN 978-1-57356-557-8.

- Cain, Charles W. and Mike Gerram.Fighters of World War II. London: Profile Publications, 1979.

- Caldwell, Donald L.; Muller, Richard R. (2007). The Luftwaffe over Germany: Defense of the Reich. London, UK: Greenhill Books. ISBN 978-1-85367-712-0.

- Davis, Larry. P-47 Thunderbolt in Action, Squadron/Signal Publications (#67). Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications, 1984. ISBN 0-89747-161-X.

- Donald, David, ed. American Warplanes of the Second World War. London: Airtime Publications, 1995. ISBN 1-84013-392-9.

- Dorr, Robert F. and David Donald. Fighters of the United States Air Force. London: Temple, 1990. ISBN 0-600-55094-X.

- Freeman, Roger A. 56th Fighter Group. Oxford, UK: Osprey, 2000. ISBN 1-84176-047-1.

- Freeman, Roger A. Camouflage and Markings 15: Republic P-47 Thunderbolt U.S.A.A.F., E.T.O. And M.T.O. 1942–1945 (Ducimus Classic). London: Ducimus Books, 1971.

- Freeman, Roger A. Thunderbolt: A Documentary History of the Republic P-47. London: Macdonald and Jane's, 1978. ISBN 0-354-01166-9.

- Goebel, Greg. "The Republic P-47 Thunderbolt." Air Vectors, April 2009.

- Gordon, Yefim. Soviet Air Power in World War 2. Hinkley, UK: Midland/Ian Allan Publishing, 2008. ISBN 978-1-85780-304-4.

- Graff, Cory. P-47 Thunderbolt at War (The At War Series). St. Paul, Minnesota: Zenith Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-7603-2948-1.

- Green, William. Fighters Vol. 2 (Warplanes of the Second World War). New York: Doubleday and Company Inc., 1961.

- Guillemin, Sébastien. Republic P-47 Thunderbolt (Les Materiels de l'Armée de L'Air 4) (in French). Paris: Histoire et Collections, 2007. ISBN 978-2-915239-90-4.

- Gunston, Bill. Aircraft of World War 2. London: Octopus Books Limited, 1980. ISBN 0-7064-1287-7.

- Hagedorn, Dan. Republic P-47 Thunderbolt: The Final Chapter: Latin American Air Forces Service. St. Paul, Minnesota: Phalanx Publishing Co. Ltd., 1991. ISBN 0-9625860-1-3.

- Hardesty, Von. Red Phoenix: The Rise of Soviet Air Power 1941–1945. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1991 (first edition 1982). ISBN 0-87474-510-1.

- Hess, William N. P-47 Thunderbolt (Warbird History). St. Paul, Minnesota: Motorbooks International Publishers, 1994. ISBN 0-87938-899-4.

- Lake, Jon. "P-47 Thunderbolt Part 1: Early development and combat in the ETO". International Air Power Review, Volume 1, Summer 2001. Westport, Connecticut: AIRtime Publishing. pp. 138–69. ISSN 1473-9917.

- Lake, Jon. "P-47 Thunderbolt Part 2: Final developments and combat in the Mediterranean, Far East and Pacific". International Air Power Review, Volume 7, Winter 2002. Westport, Connecticut: AIRtime Publishing. pp. 128–65. ISSN 1473-9917. ISBN 1-880588-48-X.

- Mondey, David. The Concise Guide to American Aircraft of World War II. London: Chartwell Books, 1994. ISBN 0-7858-0147-2.

- O'Leary, Michael. USAAF fighters of World War Two in action. London: Blandford Press, 1986. ISBN 0-7137-1839-0.

- Ryan, Cornelius. A Bridge Too Far. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1974. ISBN 978-0-445-08373-8.

- Scutts, Jerry. Republic P-47 Thunderbolt (Combat Legend). Ramsbury, Wiltshire, UK: Airlife Publishing, 2003. ISBN 1-84037-402-0.

- Sims, Edward H. Fighter Tactics and Strategy 1914–1970. Fallbroock, California: Aero publisher, 1980. ISBN 0-8168-8795-0.

- Sgarlato, Nico and Giorgio Gibertini. "P-47" (in Italian). I Grandi Aerei Storici n.14, January 2005. Parma, Italy: Delta Editrice. ISSN 1720-0636.

- Spick, Mike. Fighter Pilot Tactics. The Techniques of Daylight Air Combat. Cambridge, UK: Patrick Stephens, 1983. ISBN 0-85059-617-3.

- Panzer IV vs Sherman: France 1944 by Steven Zaloga

- Stoff, Joshua. The Thunder Factory: An Illustrated History of the Republic Aviation Corporation. London: Arms & Armour Press, 1990. ISBN 1-85409-040-2.

The initial version of this article was based on a public domain article from Greg Goebel's Vectorsite.

External links

- "Design Analysis of the P-47 Thunderbolt" by Nicholas Mastrangelo, Chief Technical Publications, Republic Aviation Corporation

- WWII P-47 pilots' Encounter Reports (4th, 56th, 78th, 352nd, 353rd, 355th, 361st FGs)

- "It's The Thunderbolt", December 1942 article in Popular Science.

- The short film How to Fly the P-47: Pilot Familiarization is available for free download at the Internet Archive.

- P-47 Pilot's Flight Operation Instructions, April 10, 1942.

- USAAF At War 1942–45 audiobook with wartime P-47 pilot interviews.

- "Thunderbolt's Own Back Yard!" a 1943 Republic advertisement for the Thunderbolt in Flight