Human sacrifice

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease gods, a human ruler, an authoritative/priestly figure or spirits of dead ancestors, and/or as a retainer sacrifice, wherein a monarch's servants are killed in order for them to continue to serve their master in the next life. Closely related practices found in some tribal societies are cannibalism and headhunting.[1]

_-_Ciudad_de_M%C3%A9xico.jpg.webp)

| Part of a series on |

| Homicide |

|---|

| Murder |

|

Note: Varies by jurisdiction

|

| Manslaughter |

|

| Non-criminal homicide |

|

Note: Varies by jurisdiction

|

| By victim or victims |

| Family |

|

| Other |

|

Human sacrifice was practiced in many human societies beginning in prehistoric times. By the Iron Age (1st millennium BCE), with the associated developments in religion (the Axial Age), human sacrifice was becoming less common throughout Africa, Europe, and Asia, and came to be looked down upon as barbaric during classical antiquity. In the Americas, however, human sacrifice continued to be practiced, by some, to varying degrees until the European colonization of the Americas. Today, human sacrifice has become extremely rare.

Modern secular laws treat human sacrifices as tantamount to murder.[2][3] Most major religions in the modern day condemn the practice. For example, the Hebrew Bible prohibits murder and human sacrifice to Molech.[4]

Evolution and context

Human sacrifice (sometimes called ritual murder), has been practiced on a number of different occasions and in many different cultures. The various rationales behind human sacrifice are the same that motivate religious sacrifice in general. Human sacrifice is typically intended to bring good fortune and to pacify the gods, for example in the context of the dedication of a completed building like a temple or bridge. Fertility was another common theme in ancient religious sacrifices, such as sacrifices to the Aztec god of agriculture Xipe Totec.[5]

In ancient Japan, legends talk about hitobashira ("human pillar"), in which maidens were buried alive at the base of or near some constructions to protect the buildings against disasters or enemy attacks,[6] and almost identical accounts appear in the Balkans (The Building of Skadar and Bridge of Arta).

For the re-consecration of the Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan in 1487, the Aztecs reported that they killed about 80,400 prisoners over the course of four days. According to Ross Hassig, author of Aztec Warfare, "between 10,000 and 80,400 persons" were sacrificed in the ceremony.[7]

Human sacrifice can also have the intention of winning the gods' favor in warfare. In Homeric legend, Iphigeneia was to be sacrificed by her father Agamemnon to appease Artemis so she would allow the Greeks to wage the Trojan War.

In some notions of an afterlife, the deceased will benefit from victims killed at his funeral. Mongols, Scythians, early Egyptians and various Mesoamerican chiefs could take most of their household, including servants and concubines, with them to the next world. This is sometimes called a "retainer sacrifice", as the leader's retainers would be sacrificed along with their master, so that they could continue to serve him in the afterlife.

Another purpose is divination from the body parts of the victim. According to Strabo, Celts stabbed a victim with a sword and divined the future from his death spasms.[8]

Headhunting is the practice of taking the head of a killed adversary, for ceremonial or magical purposes, or for reasons of prestige. It was found in many pre-modern tribal societies.

Human sacrifice may be a ritual practiced in a stable society, and may even be conducive to enhance societal unity (see: Sociology of religion), both by creating a bond unifying the sacrificing community, and in combining human sacrifice and capital punishment, by removing individuals that have a negative effect on societal stability (criminals, religious heretics, foreign slaves or prisoners of war). However, outside of civil religion, human sacrifice may also result in outbursts of blood frenzy and mass killings that destabilize society.

Many cultures show traces of prehistoric human sacrifice in their mythologies and religious texts, but ceased the practice before the onset of historical records. Some see the story of Abraham and Isaac (Genesis 22) as an example of an etiological myth, explaining the abolition of human sacrifice. The Vedic Purushamedha (literally "human sacrifice") is already a purely symbolic act in its earliest attestation. According to Pliny the Elder, human sacrifice in ancient Rome was abolished by a senatorial decree in 97 BCE, although by this time the practice had already become so rare that the decree was mostly a symbolic act. Human sacrifice once abolished is typically replaced by either animal sacrifice, or by the mock-sacrifice of effigies, such as the Argei in ancient Rome.

History by region

Ancient Near East

Successful agricultural cities had already emerged in the Near East by the Neolithic, some protected behind stone walls. Jericho is the best known of these cities but other similar settlements existed along the coast of Levant extending north into Asia Minor and west to the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Most of the land was arid and the religious culture of the entire region centered on fertility and rain. Many of the religious rituals, including human sacrifice, had an agricultural focus. Blood was mixed with soil to improve its fertility.[9]

Ancient Egypt

There may be evidence of retainer sacrifice in the early dynastic period at Abydos, when on the death of a King he would be accompanied with servants, and possibly high officials, who would continue to serve him in eternal life. The skeletons that were found had no obvious signs of trauma, leading to speculation that the giving up of life to serve the King may have been a voluntary act, possibly carried out in a drug induced state. At about 2800 BCE, any possible evidence of such practices disappeared, though echoes are perhaps to be seen in the burial of statues of servants in Old Kingdom tombs.[10][11]

Levant

References in the Bible point to an awareness of and disdain of human sacrifice in the history of ancient Near Eastern practice. During a battle with the Israelites, the King of Moab gives his firstborn son and heir as a whole burnt offering (olah, as used of the Temple sacrifice) (2 Kings 3:27).[12] The Bible then recounts that, following the King's sacrifice, "There was great indignation [or wrath] against Israel" and that the Israelites had to raise their siege of the Moabite capital and go away. This verse had perplexed many later Jewish and Christian commentators, who tried to explain what the impact of the Moabite King's sacrifice was, to make those under siege emboldened while disheartening the Israelites, make God angry at the Israelites or the Israelites fear his anger, make Chemosh (the Moabite god) angry, or otherwise.[13] Whatever the explanation, evidently at the time of writing, such an act of sacrificing the firstborn son and heir, while prohibited by Israelites (Deuteronomy 12:31; 18:9-12), was considered as an emergency measure in the Ancient Near East, to be performed in exceptional cases where divine favor was desperately needed.

The binding of Isaac appears in the Book of Genesis (22); the story appears in the Quran, though Islamic tradition holds that Ismael was the one to be sacrificed. In both the Quranic and Biblical stories, God tests Abraham by asking him to present his son as a sacrifice on Moriah. Abraham agrees to this command without arguing. The story ends with an angel stopping Abraham at the last minute and providing a ram, caught in some nearby bushes, to be sacrificed instead. Many Bible scholars have suggested this story's origin was a remembrance of an era when human sacrifice was abolished in favour of animal sacrifice.[14][15]

Another probable instance of human sacrifice mentioned in the Bible is the sacrifice of Jephthah's daughter in Judges 11. Jephthah vows to sacrifice to God whatsoever comes to greet him at the door when he returns home if he is victorious. The vow is stated in the Book of Judges 11:31: "Then it shall be, that whatsoever cometh forth of the doors of my house to meet me, when I return in peace from the children of Ammon, shall surely be the Lord's, and I will offer Him a burnt offering." When he returns from battle, his virgin daughter runs out to greet him. She begs for, and is granted, "two months to roam the hills and weep with my friends", after which "he [Jephthah] did to her as he had vowed."

Two kings of Judah, Ahaz and Manassah, sacrificed their sons. Ahaz, in 2 Kings 16:3, sacrificed his son. "... He even burned his son as an offering, according to the despicable practices of the nations whom the Lord drove out before the people of Israel (ESV)." King Manasseh sacrificed his sons in 2 Chronicles 33:6. "And he burned his sons as an offering in the Valley of Hinnom ... He did much evil in the sight of the Lord, provoking him to anger (ESV)." The valley symbolized hell in later religions, such as Christianity, as a result.

Phoenicia

According to Roman and Greek sources, Phoenicians and Carthaginians sacrificed infants to their gods. The bones of numerous infants have been found in Carthaginian archaeological sites in modern times, but their cause of death remain controversial.[16] In a single child cemetery called the "Tophet" by archaeologists, an estimated 20,000 urns were deposited.[17]

Plutarch (c. 46 – c. 120 CE) mentions the practice, as do Tertullian, Orosius, Diodorus Siculus and Philo. Livy and Polybius do not. The Bible asserts that children were sacrificed at a place called the tophet ("roasting place") to the god Moloch. According to Diodorus Siculus's Bibliotheca historica, "There was in their city a bronze image of Cronus extending its hands, palms up and sloping toward the ground, so that each of the children when placed thereon rolled down and fell into a sort of gaping pit filled with fire."[18]

Plutarch, however, claims that the children were already dead at the time, having been killed by their parents, whose consent – as well as that of the children – was required. Tertullian explains the acquiescence of the children as a product of their youthful trustfulness.[18]

The accuracy of such stories is disputed by some modern historians and archaeologists.[19]

Neolithic Europe

There is archaeological evidence of human sacrifice in Neolithic to Eneolithic Europe.

Greco-Roman antiquity

.jpg.webp)

The ancient ritual of expelling certain slaves, cripples, or criminals from a community to ward off disaster (known as Pharmakos), would at times involve publicly executing the chosen prisoner by throwing them off of a cliff.

References to human sacrifice can be found in Greek historical accounts as well as mythology. The human sacrifice in mythology, the deus ex machina salvation in some versions of Iphigeneia (who was about to be sacrificed by her father Agamemnon) and her replacement with a deer by the goddess Artemis, may be a vestigial memory of the abandonment and discrediting of the practice of human sacrifice among the Greeks in favour of animal sacrifice.

In ancient Rome, human sacrifice was infrequent but documented. Roman authors often contrast their own behavior with that of people who would commit the heinous act of human sacrifice. These authors make it clear that such practices were from a much more uncivilized time in the past, far removed.[20] It is thought that many ritualistic celebrations and dedications to gods used to involve human sacrifice but have now been replaced with symbolic offerings. Dionysius of Halicarnassus[21] says that the ritual of the Argei, in which straw figures were tossed into the Tiber river, may have been a substitute for an original offering of elderly men. Cicero claimed that puppets thrown from the Pons Suplicius by the Vestal Virgins in a processional ceremony were substitutes for the past sacrifice of old men.[22]

After the Roman defeat at Cannae, two Gauls and two Greeks in male-female couples were buried under the Forum Boarium, in a stone chamber used for the purpose at least once before.[23] In Livy's description of these sacrifices, he distances the practice from Roman tradition and asserts that the past human sacrifices evident in the same location were "wholly alien to the Roman spirit."[24] The rite was apparently repeated in 113 BCE, preparatory to an invasion of Gaul.[25] They buried both the Greeks and the two Gauls alive as a plea to the gods to save Rome from destruction at the hands of Hannibal.

According to Pliny the Elder, human sacrifice was banned by law during the consulship of Publius Licinius Crassus and Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus in 97 BCE, although by this time it was so rare that the decree was largely symbolic.[26] The Romans also had traditions that centered around ritual murder, but which they did not consider to be sacrifice. Such practices included burying unchaste Vestal Virgins alive and drowning hermaphroditic children. These were seen as reactions to extraordinary circumstances as opposed to being part of Roman tradition. Vestal Virgins who were accused of being unchaste were put to death, and a special chamber was built to bury them alive. This aim was to please the gods and restore balance to Rome[20][lower-alpha 1] Human sacrifices, in the form of burying individuals alive, were not uncommon during times of panic in ancient Rome. However, the burial of unchaste Vestal Virgins was also practiced in times of peace. Their chasteness was thought to be a safeguard of the city, and even in punishment, the state of their bodies was preserved in order to maintain the peace.[27][28]

Captured enemy leaders were only occasionally executed at the conclusion of a Roman triumph, and the Romans themselves did not consider these deaths a sacrificial offering. Gladiator combat was thought by the Romans to have originated as fights to the death among war captives at the funerals of Roman generals, and Christian polemicists such as Tertullian considered deaths in the arena to be little more than human sacrifice.[29] Over time, participants became criminals and slaves, and their death was considered a sacrifice to the Manes on behalf of the dead.[30]

Political rumors sometimes centered around sacrifice and in doing so, aimed to liken individuals to barbarians and show that the individual had become uncivilized. Human sacrifice also became a marker and defining characteristic of magic and bad religion.[31]

Celtic peoples

.jpg.webp)

There is evidence that ancient Celtic peoples practiced human sacrifice.[32] Accounts of Celtic human sacrifice come from Roman and Greek sources. Julius Caesar[33] and Strabo wrote that the Gauls burnt animal and human sacrifices in a large wickerwork figure, known as a wicker man, and said the human victims were usually criminals; while Posidonius wrote that druids who oversaw human sacrifices foretold the future by watching the death throes of the victims.[34] Caesar also wrote that slaves of Gaulish chiefs would be burnt along with the body of their master as part of his funeral rites.[35] In the 1st century AD, Roman writer Lucan mentioned human sacrifices to the Gaulish gods Esus, Toutatis and Taranis. In a 4th century commentary on Lucan, an unnamed author added that sacrifices to Esus were hanged from a tree, those to Toutatis were drowned, and those to Taranis were burned.[36] According to the 2nd-century Roman writer Cassius Dio, Boudica's forces impaled Roman captives during her rebellion against the Roman occupation, to the accompaniment of revelry and sacrifices in the sacred groves of Andate.[37] It is important to note, however, that the Romans benefited from making the Celts sound barbaric, and scholars are more skeptical about these accounts now than in the past.[38]

Ritualized beheading was a major religious and cultural practice that has found copious support in the archaeological record, including the numerous skulls found in Londinium's River Walbrook and the twelve headless corpses at the Gaulish sanctuary of Gournay-sur-Aronde.[lower-alpha 2]

Several ancient Irish bog bodies have been interpreted as kings who were ritually killed, presumably after serious crop failures or other disasters. Some were deposited in bogs on territorial boundaries (which were seen as liminal places) or near royal inauguration sites, and some were found to have eaten a ceremonial last meal.[42][43] Some academics suggest there are allusions to kings being sacrificed in Irish mythology, particularly in tales of threefold deaths.[32]

The medieval Dindsenchas (Lore of Places) says that, in pagan Ireland, first-born children were sacrificed at an idol called Crom Cruach, whose worship was ended by Saint Patrick. However, this account was written by Christian scribes centuries after the supposed events and may be based on Bibical traditions about the god Moloch.[44]

In Britain, the medieval legends of Dinas Emrys and of Saint Oran of Iona mention foundation sacrifices, whereby people were ritually killed and buried under foundations to ensure the building's safety.[32] The Waldensians sect was later accused of child sacrifice by the Church.[45][46]

Germanic peoples

.jpg.webp)

Human sacrifice was not particularly common among the Germanic peoples, being resorted to in exceptional situations arising from environmental crises (crop failure, drought, famine) or social crises (war), often thought to derive at least in part from the failure of the king to establish and/or maintain prosperity and peace (árs ok friðar) in the lands entrusted to him.[47] In later Scandinavian practice, human sacrifice appears to have become more institutionalised and was repeated periodically as part of a larger sacrifice (according to Adam of Bremen, every nine years).[48]

Evidence of human sacrifice by Germanic pagans before the Viking Age depend on archaeology and on a few accounts in Greco-Roman ethnography. Roman writer Tacitus reported the Suebians making human sacrifices to gods he interpreted as Mercury and Isis. He also claimed that Germans sacrificed Roman commanders and officers as a thanksgiving for victory in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest.[49][50] Jordanes reported the Goths sacrificing prisoners of war to Mars, suspending the victims' severed arms from tree branches.[51]

By the 10th century, Germanic paganism had become restricted to the Norse people. One account by Ahmad ibn Fadlan in 922 claims Varangian warriors were sometimes buried with enslaved women, in the belief they would become their wives in Valhalla. He describes the funeral of a Varangian chieftain, in which a slave girl volunteered to be buried with him. After ten days of festivities, she was given an intoxicating drink, stabbed to death by a priestess, and burnt together with the dead chieftain in his boat (see ship burial). This practice is evidenced archaeologically, with many male warrior burials (such as the ship burial at Balladoole on the Isle of Man, or that at Oseberg in Norway[52]) also containing female remains with signs of trauma.

According to Adémar de Chabannes, just before his death in 932 or 933, Rollo (founder and first ruler of the Viking Duchy of Normandy) performed human sacrifices to appease the pagan gods while at the same time giving gifts to the churches in Normandy.[53]

In the 11th century, Adam of Bremen wrote that human and animal sacrifices were made at the Temple at Gamla Uppsala in Sweden. He wrote that every ninth year, nine men and nine of every animal were sacrificed and their bodies hung in a sacred grove.[54]

The Historia Norwegiæ and Ynglinga saga refer to the willing sacrifice of King Dómaldi after bad harvests.[55] The same saga also relates that Dómaldi's descendant king Aun sacrificed nine of his own sons to Odin in exchange for longer life, until the Swedes stopped him from sacrificing his last son, Egil.

In the Saga of Hervor and Heidrek, Heidrek agrees to the sacrifice of his son in exchange for command over half the army of Reidgotaland. With this, he seizes the whole kingdom and prevents the sacrifice of his son, dedicating those fallen in his rebellion to Odin instead.

Slavic peoples

In the 10th century, Persian explorer Ahmad ibn Rustah described funerary rites for the Rus' (Scandinavian Norsemen traders in northeastern Europe) including the sacrifice of a young female slave.[56] Leo the Deacon describes prisoner sacrifice by the Rus' led by Sviatoslav during the Russo-Byzantine War "in accordance with their ancestral custom."[57]

According to the 12th-century Russian Primary Chronicle, prisoners of war were sacrificed to the supreme Slavic deity Perun. Sacrifices to pagan gods, along with paganism itself, were banned after the Baptism of Rus' by Prince Vladimir I in the 980s.[58]

Archeological findings indicate that the practice may have been widespread, at least among slaves, judging from mass graves containing the cremated fragments of a number of different people.[56]

China

The history of human sacrifice in China may extend as early as 2300 BCE.[59] Excavations of the ancient fortress city of Shimao in the northern part of modern Shaanxi province revealed 80 skulls ritually buried underneath the city's eastern wall.[59] Forensic analysis indicates the victims were all teenage girls.[59]

The ancient Chinese are known to have made drowned sacrifices of men and women to the river god Hebo.[60] They also have buried slaves alive with their owners upon death as part of a funeral service. This was especially prevalent during the Shang and Zhou dynasties. During the Warring States period, Ximen Bao of Wei outlawed human sacrificial practices to the river god.[61] In Chinese lore, Ximen Bao is regarded as a folk hero who pointed out the absurdity of human sacrifice.

The sacrifice of a high-ranking male's slaves, concubines, or servants upon his death (called Xun Zang 殉葬 or Sheng Xun 生殉) was a more common form. The stated purpose was to provide companionship for the dead in the afterlife. In earlier times, the victims were either killed or buried alive, while later they were usually forced to commit suicide.

Funeral human sacrifice was widely practiced in the ancient Chinese state of Qin. According to the Records of the Grand Historian by Han dynasty historian Sima Qian, the practice was started by Duke Wu, the tenth ruler of Qin, who had 66 people buried with him in 678 BCE. The 14th ruler Duke Mu had 177 people buried with him in 621 BCE, including three senior government officials.[62][63] Afterwards, the people of Qin wrote the famous poem Yellow Bird to condemn this barbaric practice, later compiled in the Confucian Classic of Poetry.[64] The tomb of the 18th ruler Duke Jing of Qin, who died in 537 BCE, has been excavated. More than 180 coffins containing the remains of 186 victims were found in the tomb.[65][66] The practice would continue until Duke Xian of Qin (424–362 BCE) abolished it in 384 BCE. Modern historian Ma Feibai considers the significance of Duke Xian's abolition of human sacrifice in Chinese history comparable to that of Abraham Lincoln's abolition of slavery in American history.[63][67]

After the abolition by Duke Xian, funeral human sacrifice became relatively rare throughout the central parts of China. However, the Hongwu Emperor of the Ming dynasty revived it in 1395, following the Mongolian Yuan precedent, when his second son died and two of the prince's concubines were sacrificed. In 1464, the Tianshun Emperor, in his will, forbade the practice for Ming emperors and princes.

Human sacrifice was also practised by the Manchus. Following Nurhaci's death, his wife, Lady Abahai, and his two lesser consorts committed suicide. During the Qing dynasty, sacrifice of slaves was banned by the Kangxi Emperor in 1673.

Mesopotamia

Retainer sacrifice was practised within the royal tombs of ancient Mesopotamia. Courtiers, guards, musicians, handmaidens, and grooms were presumed to have committed ritual suicide by taking poison.[68][69] A 2009 examination of skulls from the royal cemetery at Ur, discovered in Iraq in the 1920s by a team led by C. Leonard Woolley, appears to support a more grisly interpretation of human sacrifices associated with elite burials in ancient Mesopotamia than had previously been recognized. Palace attendants, as part of royal mortuary ritual, were not dosed with poison to meet death serenely. Instead, they were put to death by having a sharp instrument, such as a pike, driven into their heads.[70][71]

Tibet

Human sacrifice was practiced in Tibet prior to the arrival of Buddhism in the 7th century.[lower-alpha 3] Historical practices such as burying bodies under the cornerstones of houses may have been practiced during the medieval era, but few concrete instances have been recorded or verified.[73]

The prevalence of human sacrifice in medieval Buddhist Tibet is less clear. The Lamas, as professing Buddhists, could not condone blood sacrifices, and they replaced the human victims with effigies made from dough which is still to this day dyed partially red to symbolize sacrifice.[73] This replacement of human victims with effigies is attributed to Padmasambhava, a Tibetan saint of the mid-8th century, in Tibetan tradition.[74]

Nevertheless, there is some evidence that outside of orthodox Buddhism, there were practices of tantric human sacrifice which survived throughout the medieval period, and possibly into modern times.[73] The 15th century Blue Annals reports that in the 13th century so-called "18 robber-monks" slaughtered men and women in their ceremonies.[75] Grunfeld (1996) concludes that it cannot be ruled out that isolated instances of human sacrifice did survive in remote areas of Tibet until the mid-20th century, but they must have been rare.[73] Grunfeld also notes that Tibetan practices unrelated to human sacrifice, such as the use of human bone in ritual instruments, have been depicted without evidence as products of human sacrifice.[73]

Indian subcontinent

In India, human sacrifice is mainly known as Narabali. Here "nara" means human and "bali" means sacrifice. It takes place in some parts of India mostly to find lost treasure. In Maharashtra, the Government made it illegal to practice with the Anti-Superstition and Black Magic Act. Currently human sacrifice is very rare in modern India.[76] There have been at least three cases through 2003–2013 where men have been murdered in the name of human sacrifice.[77][78][79] And two females were sacrificed and then eaten in the state of Kerala in 2022[80]

Regarding possible Vedic mention of human sacrifice, the prevailing 19th-century view, associated above all with Henry Colebrooke, was that human sacrifice did not actually take place. Those verses which referred to purushamedha were meant to be read symbolically,[81] or as a "priestly fantasy". However, Rajendralal Mitra published a defence of the thesis that human sacrifice, as had been practised in Bengal, was a continuation of traditions dating back to Vedic periods.[82] Hermann Oldenberg held to Colebrooke's view; but Jan Gonda underlined its disputed status.

Human and animal sacrifice became less common during the post-Vedic period, as ahimsa (non-violence) became part of mainstream religious thought. The Chandogya Upanishad (3.17.4) includes ahimsa in its list of virtues.[81] The impact of Sramanic religions such as Buddhism and Jainism also became known in the Indian subcontinent.

In the 7th century, Banabhatta, in a description of the dedication of a temple of Chandika, describes a series of human sacrifices; similarly, in the 9th century, Haribhadra describes the sacrifices to Chandika in Odisha.[83] The town of Kuknur in North Karnataka there exists an ancient Kali temple, built around the 8-9th century CE, which has a history of human sacrifices.[83] Human sacrifice is reputed to have been performed on the altars of the Hatimura Temple, a Shakti (Great Goddess) temple located at Silghat, in the Nagaon district of Assam. It was built during the reign of king Pramatta Singha in 1667 Sakabda (1745–1746 CE). It used to be an important center of Shaktism in ancient Assam. Its presiding goddess is Durga in her aspect of Mahisamardini, slayer of the demon Mahisasura. It was also performed in the Tamresari Temple which was located in Sadiya under the Chutia kings.

Human sacrifices were carried out in connection with the worship of Shakti until approximately the early modern period, and in Bengal perhaps as late as the early 19th century.[84] Although not accepted by larger section of Hindu culture, certain Tantric cults performed human sacrifice until around the same time, both actual and symbolic; it was a highly ritualised act, and on occasion took many months to complete.[84]

Pacific

_c._1773.jpg.webp)

In Ancient Hawaii, a luakini temple, or luakini heiau, was a Native Hawaiian sacred place where human and animal blood sacrifices were offered. Kauwa, the outcast or slave class, were often used as human sacrifices at the luakini heiau. They are believed to have been war captives, or the descendants of war captives. They were not the only sacrifices; law-breakers of all castes or defeated political opponents were also acceptable as victims.[85][86]

According to an 1817 account, in Tonga, a child was strangled to assist the recovery of a sick relation.[87]

The people of Fiji practised widow-strangling. When Fijians adopted Christianity, widow-strangling was abandoned.[88]

Pre-Columbian Americas

Some of the most famous forms of ancient human sacrifice were performed by various Pre-Columbian civilizations in the Americas[89] that included the sacrifice of prisoners as well as voluntary sacrifice. Friar Marcos de Niza (1539), writing of the Chichimecas, said that from time to time "they of this valley cast lots whose luck (honour) it shall be to be sacrificed, and they make him great cheer, on whom the lot falls, and with great joy they lund him with flowers upon a bed prepared in the said ditch all full of flowers and sweet herbs, on which they lay him along, and lay great store of dry wood on both sides of him, and set it on fire on either part, and so he dies" and "that the victim took great pleasure" in being sacrificed.[90]

North America

The Mixtec players of the Mesoamerican ballgame were sacrificed when the game was used to resolve a dispute between cities. The rulers would play a game instead of going to battle. The losing ruler would be sacrificed. The ruler "Eight Deer", who was considered a great ball player and who won several cities this way, was eventually sacrificed, because he attempted to go beyond lineage-governing practices, and to create an empire.[91]

Maya

The Maya held the belief that cenotes or limestone sinkholes were portals to the underworld and sacrificed human beings and tossed them down the cenote to please the water god Chaac. The most notable example of this is the "Sacred Cenote" at Chichén Itzá.[92] Extensive excavations have recovered the remains of 42 individuals, half of them under twenty years old.

Only in the Post-Classic era did this practice become as frequent as in central Mexico.[93] In the Post-Classic period, the victims and the altar are represented as daubed in a hue now known as Maya blue, obtained from the añil plant and the clay mineral palygorskite.[94]

Aztecs

.jpg.webp)

The Aztecs were particularly noted for practicing human sacrifice on a large scale; an offering to Huitzilopochtli would be made to restore the blood he lost, as the sun was engaged in a daily battle. Human sacrifices would prevent the end of the world that could happen on each cycle of 52 years. In the 1487 re-consecration of the Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan some estimate that 80,400 prisoners were sacrificed[95][96] though numbers are difficult to quantify, as all obtainable Aztec texts were destroyed by Christian missionaries during the period 1528–1548.[97] The Aztec, also known as Mexica, periodically sacrificed children as it was believed that the rain god, Tlāloc, required the tears of children.[92]

According to Ross Hassig, author of Aztec Warfare, "between 10,000 and 80,400 people" were sacrificed in the ceremony. The old reports of numbers sacrificed for special feasts have been described as "unbelievably high" by some authors[97] and that on cautious reckoning, based on reliable evidence, the numbers could not have exceeded at most several hundred per year in Tenochtitlan.[97] The real number of sacrificed victims during the 1487 consecration is unknown.

Michael Harner, in his 1997 article The Enigma of Aztec Sacrifice, estimates the number of persons sacrificed in central Mexico in the 15th century as high as 250,000 per year. Fernando de Alva Cortés Ixtlilxochitl, a Mexica descendant and the author of Codex Ixtlilxochitl, claimed that one in five children of the Mexica subjects was killed annually. Victor Davis Hanson argues that an estimate by Carlos Zumárraga of 20,000 per annum is more plausible. Other scholars believe that, since the Aztecs always tried to intimidate their enemies, it is far more likely that they inflated the official number as a propaganda tool.[98][99]

United States and Canada

The peoples of the Southeastern United States known as the Mississippian culture (800 to 1600 CE) have been suggested to have practiced human sacrifice, because some artifacts have been interpreted as depicting such acts.[100] Mound 72 at Cahokia (the largest Mississippian site), located near modern St. Louis, Missouri, was found to have numerous pits filled with mass burials thought to have been retainer sacrifices. One of several similar pit burials had the remains of 53 young women who had been strangled and neatly arranged in two layers. Another pit held 39 men, women, and children who showed signs of dying a violent death before being unceremoniously dumped into the pit. Several bodies showed signs of not having been fully dead when buried and of having tried to claw their way to the surface. On top of these people another group had been neatly arranged on litters made of cedar poles and cane matting. Another group of four individuals found in the mound were interred on a low platform, with their arms interlocked. They had had their heads and hands removed. The most spectacular burial at the mound is the "Birdman burial". This was the burial of a tall man in his 40s, now thought to have been an important early Cahokian ruler. He was buried on an elevated platform covered by a bed of more than 20,000 marine-shell disc beads arranged in the shape of a falcon,[101] with the bird's head appearing beneath and beside the man's head, and its wings and tail beneath his arms and legs. Below the birdman was another man, buried facing downward. Surrounding the birdman were several other retainers and groups of elaborate grave goods.[102][103]

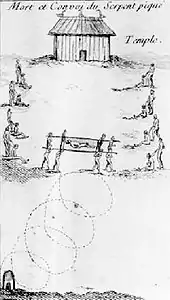

A ritual sacrifice of retainers and commoners upon the death of an elite personage is also attested in the historical record among the last remaining fully Mississippian culture, the Natchez. Upon the death of "Tattooed Serpent" in 1725, the war chief and younger brother of the "Great Sun" or Chief of the Natchez; two of his wives, one of his sisters (nicknamed La Glorieuse by the French), his first warrior, his doctor, his head servant and the servant's wife, his nurse, and a craftsman of war clubs all chose to die and be interred with him, as well as several old women and an infant who was strangled by his parents.[104] Great honor was associated with such a sacrifice, and their kin were held in high esteem.[105] After a funeral procession with the chief's body carried on a litter made of cane matting and cedar poles ended at the temple (which was located on top of a low platform mound), the retainers, with their faces painted red and drugged with large doses of nicotine, were ritually strangled. Tattooed Serpent was then buried in a trench inside the temple floor and the retainers were buried in other locations atop the mound surrounding the temple. After a few months' time the bodies were dis-interred and their defleshed bones were stored as bundle burials in the temple.[104]

The Pawnee practiced an annual Morning Star Ceremony, which included the sacrifice of a young girl. Though the ritual continued, the sacrifice was discontinued in the 19th century.[106]

South America

.jpg.webp)

The Incas practiced human sacrifice, especially at great festivals or royal funerals where retainers died to accompany the dead into the next life.[107] The Moche sacrificed teenagers en masse, as archaeologist Steve Bourget found when he uncovered the bones of 42 male adolescents in 1995.[108]

The study of the images seen in Moche art has enabled researchers to reconstruct the culture's most important ceremonial sequence, which began with ritual combat and culminated in the sacrifice of those defeated in battle. Dressed in fine clothes and adornments, armed warriors faced each other in ritual combat. In this hand-to-hand encounter the aim was to remove the opponent's headdress rather than kill him. The object of the combat was the provision of victims for sacrifice. The vanquished were stripped and bound, after which they were led in procession to the place of sacrifice. The captives are portrayed as strong and sexually potent. In the temple, the priests and priestesses would prepare the victims for sacrifice. The sacrificial methods employed varied, but at least one of the victims would be bled to death. His blood was offered to the principal deities in order to please and placate them.[109]

The Inca of Peru also made human sacrifices. As many as 4,000 servants, court officials, favorites, and concubines were killed upon the death of the Inca Huayna Capac in 1527, for example.[110] A number of mummies of sacrificed children have been recovered in the Inca regions of South America, an ancient practice known as qhapaq hucha. The Incas performed child sacrifices during or after important events, such as the death of the Sapa Inca (emperor) or during a famine.[108]

West Africa

Human sacrifice is still practiced in West Africa.[111][112][113][114][115][116][117] The Annual customs of Dahomey was the most notorious example, but sacrifices were carried out all along the West African coast and further inland. Sacrifices were particularly common after the death of a King or Queen, and there are many recorded cases of hundreds or even thousands of slaves being sacrificed at such events. Sacrifices were particularly common in Dahomey, in what is now Benin, and in the small independent states in what is now southern Nigeria . According to Rudolph Rummel, "Just consider the Grand Custom in Dahomey: When a ruler died, hundreds, sometimes even thousands, of prisoners would be slain. In one of these ceremonies in 1727, as many as 4,000 were reported killed. In addition, Dahomey had an Annual Custom during which 500 prisoners were sacrificed."[118]

In the Ashanti Region of modern-day Ghana, human sacrifice was often combined with capital punishment.[119]

The Leopard men were a West African secret society active into the mid-1900s that practised cannibalism. It was believed that the ritual cannibalism would strengthen both members of the society and their entire tribe.[120] In Tanganyika, the Lion men committed an estimated 200 murders in a single three-month period.[121]

Canary Islands

It has been reported from Spanish chronicles that the Guanches (ancient inhabitants of these islands) performed both animal and human sacrifices.[122]

During the summer solstice in Tenerife children were sacrificed by being thrown from a cliff into the sea.[122] These children were brought from various parts of the island for the purpose of sacrifice. Likewise, when an aboriginal king died his subjects should also assume the sea, along with the embalmers who embalmed the Guanche mummies.

In Gran Canaria, bones of children were found mixed with those of lambs and goat kids and on Tenerife, amphorae have been found with the remains of children inside. This suggests a different kind of ritual infanticide from those who were thrown off the cliffs.[122]

Greek polytheism

In Greek polytheism, Tantalus was condemned to Tartarus for eternity for the human sacrifice of his son Pelops.

Prohibition in major religions

Abrahamic religions

Many traditions of Abrahamic religions such as Judaism, Christianity and Islam consider that God commanded Abraham to sacrifice his son to examine obedience of Abraham to His commands. To prove his obedience, Abraham intended to sacrifice his son. However at the eleventh hour God commanded Abraham to sacrifice a ram instead of his son.

Judaism

Judaism explicitly forbids human sacrifice, regarding it as murder. Jews view the Akedah as central to the abolition of human sacrifice. Some Talmudic scholars assert that its replacement is the sacrificial offering of animals at the Temple – using Exodus 13:2–12ff; 22:28ff; 34:19ff; Numeri 3:1ff; 18:15; Deuteronomy 15:19 – others view that as being superseded by the symbolic pars-pro-toto sacrifice of the covenant of circumcision. Leviticus 20:2 and Deuteronomy 18:10 specifically outlaw the giving of children to Moloch, making it punishable by stoning; the Tanakh subsequently denounces human sacrifice as barbaric customs of Moloch worshippers (e.g. Psalms 106:37ff).

Judges chapter 11 features a Judge named Jephthah vowing that "whatsoever cometh forth from the doors of my house to meet me shall surely be the Lord's, and I will offer it up as a burnt-offering" in gratitude for God's help with a military battle against the Ammonites.[123] Much to Jephthah's dismay, his only daughter greeted him upon his triumphant return. Judges 11:39 states that Jephthah did as he had vowed, but "shies away from explicitly depicting her sacrifice, which leads some ancient and modern interpreters (e.g., Radak) to suggest that she was not actually killed."[124]

According to the Mishnah he was under no obligation to keep the ill-phrased, illegal vow. According to Rabbi Jochanan, in his commentary on the Mishnah, it was Jephthah's obligation to pay the vow in money.[123] According to some commentators of the rabbinic Jewish tradition during the Middle Ages, Jepthah's daughter was not sacrificed, but was forbidden to marry and remained a spinster her entire life.[125]

The 1st-century CE Jewish-Hellenistic historian Flavius Josephus, however, stated that Jephthah "sacrificed his child as a burnt-offering – a sacrifice neither sanctioned by the law nor well-pleasing to God; for he had not by reflection probed what might befall or in what aspect the deed would appear to them that heard of it".[126] Latin philosopher pseudo-Philo, late 1st century CE, wrote that Jephthah burnt his daughter because he could find no sage in Israel who would cancel his vow. In other words, in the opinion of the Latin philosopher, this story of an ill-phrased vow consolidates that human sacrifice is not an order or requirement by God, but the punishment for those who illegally vowed to sacrifice humans.[127][128]

Allegations accusing Jews of committing ritual murder – called the "blood libel" – were widespread during the Middle Ages, often leading to the slaughter of entire Jewish communities.[129][130] In the 20th century, blood libel accusations re-emerged as part of the satanic ritual abuse moral panic.[130]

Christianity

Christianity developed the belief that the story of Isaac's binding was a foreshadowing of the sacrifice of Christ, whose death and resurrection enabled the salvation and atonement for man from its sins, including original sin. There is a tradition that the site of Isaac's binding, Moriah, later became Jerusalem, the city of Jesus's future crucifixion.[131] The beliefs of most Christian denominations hinge upon the substitutionary atonement of the sacrifice of God the Son, which was necessary for salvation in the afterlife. According to Christian doctrine, each individual person on earth must participate in, and / or receive the benefits of, this divine human sacrifice for the atonement of their sins. Early Christian sources explicitly described this event as a sacrificial offering, with Christ in the role of both priest and human sacrifice, although starting with the Enlightenment, some writers, such as John Locke, have disputed the model of Jesus' death as a propitiatory sacrifice.[132]

Although early Christians in the Roman Empire were accused of being cannibals, theophages (Greek for "god eaters")[133] practices such as human sacrifice were abhorrent to them.[134] Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic Christians believe that this "pure sacrifice" as Christ's self-giving in love is made present in the sacrament of the Eucharist. In this tradition, bread and wine becomes the "real presence" (the literal carnal Body and Blood of the Risen Christ). Receiving the Eucharist is a central part of the religious life of Catholic and Orthodox Christians.[135][136] Most Protestant traditions apart from Anglicanism and Lutheranism do not share the belief in the real presence but otherwise are varied, for example, they may believe that in the bread and wine, Christ is present only spiritually, not in the sense of a change in substance (Methodism)[137] or that the bread and wine of communion are a merely symbolic reminder (Baptist).[138]

In medieval Irish Catholic texts, there is mention of the early church in Ireland supposedly containing the practice of burying sacrificial victims underneath churches in order to consecrate them. This may have a relation to pagan Celtic practices of foundation sacrifice. The most notable example of this is the case of Odran of Iona a companion of St Columba who (according to legend) volunteered to die and be buried under the church of the monastery of Iona. However, there is no evidence that such things ever happened in reality and contemporary records closer to the time period have no mention of a practice like this.[139]

Dharmic religions

Many traditions of Dharmic religions including Buddhism, Jainism and some sects of Hinduism embrace the doctrine of ahimsa (non-violence) which imposes vegetarianism and outlaws animal as well as human sacrifice.

Buddhism

In the case of Buddhism, both bhikkhus (monks) and bhikkhunis (nuns) were forbidden to take life in any form as part of the monastic code, while non-violence was promoted among laity through encouragement of the Five Precepts. Across the Buddhist world both meat and alcohol are strongly discouraged as offerings to a Buddhist altar, with the former being synonymous with sacrifice, and the latter a violation of the Five Precepts.

In their effort to discredit Tibetan Buddhism, the People's Republic of China as well as Chinese nationalists in the Republic of China make frequent and emphatic references to the historical practice of human sacrifice in Tibet, portraying the 1950 People's Liberation Army invasion of Tibet as an act of humanitarian intervention. According to Chinese sources, in the year 1948, 21 individuals were murdered by state sacrificial priests from Lhasa as part of a ritual of enemy destruction, because their organs were required as magical ingredients.[140] The Tibetan Revolutions Museum established by the Chinese in Lhasa has numerous morbid ritual objects on display to illustrate these claims.[141]

Hinduism

In some sects of Hinduism, based on the principle of ahimsa, any human or animal sacrifice is forbidden.[142][143][144] In the 19th and 20th centuries, prominent figures of Indian spirituality such as Swami Vivekananda,[145] Ramana Maharshi,[146] Swami Sivananda,[147] and A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami[148] emphasised the importance of ahimsa.

Modern cases

Brazil

In the city of Altamira, State of Pará, several children were raped, with their genitalia mutilated for what appear to be ritual purposes, and then stabbed to death, between 1989 and 1993.[149] It is believed that the boys' sexual organs were used in rites of black magic.[150]

Chile

In the coastal village Collileufu, native Lafkenches carried out a ritual human sacrifice in the days following the 1960 Valdivia earthquake. Collileufu, located in the Budi Lake area, south of Puerto Saavedra, was highly isolated in 1960. The Mapuche spoke primarily Mapudungun. The community had gathered in Cerro La Mesa, while the lowlands were struck by successive tsunamis. Juana Namuncura Añen,[151][152] a local machi, demanded the sacrifice of the grandson of Juan Painecur, a neighbor, in order to calm the earth and the ocean.[153][154] The victim was 5 year-old José Luis Painecur, called an "orphan" (huacho) because his mother had gone to Santiago, for employment as a domestic worker, and left her son under the care of her father.[153]

José Luis Painecur had his arms and legs removed by Juan Pañán and Juan José Painecur (the victim's grandfather), and was stuck into the sand of the beach like a stake. The waters of the Pacific Ocean then carried the body out to sea. The authorities only learned about the sacrifice after a boy in the commune of Nueva Imperial denounced to local leaders the theft of two horses; these were allegedly eaten during the sacrifice ritual.[153] The two men were charged with the crime and confessed, but later recanted. They were released after two years. A judge ruled that those involved in these events had "acted without free will, driven by an irresistible natural force of ancestral tradition."[151][152] The story was mentioned in a Time magazine article, although with meagre detail.[155]

Mexico

In 1963, a small cult in Nuevo Leon, Mexico, founded by two brothers, Santos and Cayetano Hernández, committed between 8 and 12 murders during bloody rituals that included drinking human blood. The cult was initially a scam to obtain money and sexual favors, but after a prostitute named Magdalena Solís entered in the organization, she inaugurated human sacrifices inspired by ancient Aztec rituals as a method to control disciples.[156][157][158]

During the 1980s, other case of serial murders that involved human sacrifices rituals occurred in Tamaulipas, Mexico. The drug dealer and cult leader Adolfo Constanzo orchestrated several executions during rituals that included the victims' dismemberment.[159]

Between 2009 and 2010, in Sonora, Mexico, a serial killer named Silvia Meraz committed three murders in sacrifice rituals. With the help of her family, she beheaded two boys (both relatives) and one woman in front of an altar dedicated to Santa Muerte.[160]

Panama

The "New Light Of God" sect in the town of El Terrón, Ngäbe-Buglé Comarca, Panama, believed they had a mandate from God to sacrifice members of their community who failed to repent to their satisfaction. In 2020, 5 children, their pregnant mother, and a neighbor were killed and decapitated at the sect's church building, with 14 other wounded victims being rescued. Victims were hacked with machetes, beaten with Bibles and cudgels, and burned with embers. A goat was ritually sacrificed at the scene as well. The cult's beliefs were a syncretic blend of Pentecostalism with indigenous beliefs and some New Age ideas including emphasis on the third eye. A leader of the Ngäbe-Buglé region labeled the sect "satanic" and demanded its eradication.[161]

India

Human sacrifice is illegal in India. According to the Hindustan Times, there was an incident of human sacrifice in western Uttar Pradesh in 2003.[lower-alpha 4] Similarly, police in Khurja reported "dozens of sacrifices" in the period of half a year in 2006, by followers of Kali, the goddess of death and time.[163][164][165][166][167]

In 2015 during the Granite scam investigations of Tamil Nadu there were reports of possible human sacrifices in the Madurai area to pacify goddess Shakthi for getting power to develop the illegal granite business. Bones and skulls were retrieved from the alleged sites in presence of the special judicial officer appointed by the high court of Madras.[168][169][170]

Japan

In the practice known as Hitobashira (人柱, "human pillar"), a person was buried alive at the base of large structures such as dams, castles, and bridges.

Africa

Human sacrifice is no longer legal in any country, and such cases are prosecuted. As of 2020 however, there is still black market demand for child abduction in countries such as Kenya for purposes which include human sacrifice.[171]

In January 2008, Milton Blahyi of Liberia confessed being part of human sacrifices which "included the killing of an innocent child and plucking out the heart, which was divided into pieces for us to eat." He fought against Charles Taylor's militia.[172]

In 2019, an Anti-balaka leader in Satema in Central African Republic killed a 14 year-old girl in ritualistic way to increase profit from mines.[173]

Ritual murder

Ritual killings perpetrated by individuals or small groups within a society that denounces them as simple murder are difficult to classify as either "human sacrifice" or mere pathological homicide because they lack the societal integration of sacrifice proper.

The instances closest to "ritual killing" in the criminal history of modern society would be pathological serial killers such as the Zodiac Killer, and mass suicides with a doomsday cult background, such as the Peoples Temple, the Movement for the Restoration of the Ten Commandments of God, the Order of the Solar Temple or the Heaven's Gate incidents. Other examples include the "Matamoros killings" attributed to American cult leader Adolfo Constanzo and the "Superior Universal Alignment" killings in 1990s Brazil.[176]

The Satanic groups Order of Nine Angles[177][178] and the Temple of the Black Light promote human sacrifice.

Non-lethal "sacrifice"

In India there is a festival where a person is chosen as a "sacrifice", and is believed by participants to die during the ritual, although they actually remain alive and are "raised" from the dead at the end after a period of lying still. Thus, this does not have the same legal implications as a true human sacrifice although participants consider it to be one.[179]

See also

- Animal sacrifice

- Blood atonement

- Capital punishment

- Immurement

- Child sacrifice

- Curse of Tippecanoe

- Gehenna

- The Golden Bough

- Homo Necans

- Honor killing

- Honor suicide

- Junshi

- Margaret Murray – The Divine King in England

- Order of Nine Angles

- Pharmakos

- List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll

Footnotes

- Burying the convicted unchaste vestal in a sealed underground chamber was also a way to impose capital punishment on her for criminally endangering the city by her religious violation, without violating her still-sacred status: Among other prohibitions, no-one could touch her person.

- French archaeologist Jean-Louis Brunaux has written extensively on human sacrifice and the sanctuaries of Belgic Gaul.[39][40][41]

- "Human sacrifice seems undoubtedly to have been regularly practised in Tibet up till the dawn there of Buddhism in the seventh century."[72]

- "After a rash of similar killings in the area – according to an unofficial tally in the English language-language Hindustan Times, there have been 25 human sacrifices in western Uttar Pradesh in the last 6 months alone – police have cracked down against tantriks, jailing four and forcing scores of others to close their businesses and pull their ads from newspapers and television stations. The killings and the stern official response have focused renewed attention on tantrism, an amalgam of mysticism practices that grew out of Hinduism.[162]

References

- Michael Rudolph (2008). Ritual Performances as Authenticating Practices. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 78. ISBN 978-3825809522.

- "Boys 'used for human sacrifice'". BBC News. 2005-06-16. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- "Kenyan arrests for 'witch' deaths". BBC News. 2008-05-22. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- Exodus 20:13, Deuteronomy 5:17, Leviticus 18:21

- Enríquez, Angélica María Medrano (2021). "Child Sacrifice in Tula: A Bioarcheological Study". Ancient Mesoamerica. 31 (1).

- "History of Japanese Castles". Japanfile.com. Archived from the original on 2010-07-27. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- Hassig, Ross (2003). "El sacrificio y las guerras floridas". Arqueología Mexicana (63): 46–51. ISSN 0188-8218.

- Strabo (1923). "Book IV, chapter 4:5". Geography. Loeb Classical Library. Vol. II. University of Chicago. Retrieved 2014-02-03 – via penelope.uchicago.edu.

- Glassman, Ronald M. (19 June 2017). The Origins of Democracy in Tribes, City-States and Nation-States. p. 421. ISBN 9783319516950.

- Kinnaer, Jacques. "Human sacrifice". Ancient-egypt.org. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- "Abydos – life and death at the dawning of Egyptian civilization". National Geographic. April 2005. Archived from the original on 2007-05-09. Retrieved May 12, 2007.

- Asthana, N.C.; Nirmal, Anjali (2009). Urban Terrorism: Myths and realities. Pointer Publishers. ISBN 978-8171325986.

- "Commentaries on 2 Kings 3:27". Bible Hub. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- Ackerman, Susan (June 1993). "Child Sacrifice: Returning God's Gift". Biblical Archaeology Review. 9 (3): 20–29, 56.

- Stager, Lawrence E.; Wolff, Samuel R. (Jan–Feb 1984). "Child sacrifice at Carthage – religious rite or population control?". Biblical Archaeology Review. 10 (1): 30–51.

- Higgins, Andrew (2005-05-26). "Carthage tries to live down image as site of infanticide". Post Gazette. Archived from the original on September 18, 2009. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- "Relics of Carthage show brutality amid the good life". The New York Times. 1 September 1987.

- Salisbury, Joyce E. (1997). Perpetua's Passion: The death and memory of a young Roman woman. Routledge. p. 228.

- Fantar, M'Hamed Hassine (Nov–Dec 2000). "Were living Children Sacrificed to the Gods? No". Archaeology Odyssey. pp. 28–31. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- Schultz, Celia E. (2010). "The Romans and ritual murder". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 78 (2): 516–541. doi:10.1093/jaarel/lfq002. PMID 20726130.

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus. "i.19, 38". Roman Antiquities. University of Chicago. Retrieved 2014-02-03 – via Penelope.uchicago.edu.

- Marcus Tullius Cicero. Pro Roscio Amerino. 35.100.

- Titus Livius. Ab Urbe Condita. 22.55–57.

- Titus Livius. Ab Urbe Condita. 22.57.

- Titus Livius. Ab Urbe Condita. 22.57.4; Plutarch. Roman Questions. 83; Plutarch. Marcellus. 3; Beard, M.; North, J.A.; Price, S.R.F. (1998). Religions of Rome: A history. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 81.

- Pliny. Natural History. 30.3.12.

- Frieze (Pentelic Marble; Ht. 29"; 1. 10 1/2"). Artstor (image).

- Reid, J. S. (1912). "Human Sacrifices at Rome and other notes on Roman Religion". The Journal of Roman Studies. 2: 40. doi:10.2307/295940. hdl:2027/mdp.39015017655666. ISSN 1753-528X. JSTOR 295940. S2CID 162464054.

- Edwards, Catharine (2007). Death in Ancient Rome. Yale University Press. pp. 59–60; Potter, David S. (1999). "Entertainers in the Roman Empire". Life, Death, and Entertainment in the Roman Empire. University of Michigan Press. p. 305; Tertullian. De Spectaculis. 12.

- Piscinus, M. Horatius. "Human sacrifice in Ancient Rome". Societas via Romana.

- Rives, J. (1995). "Asante: Human sacrifice among pagans and christians". The Journal of Roman Studies. 85: 65–85. doi:10.1017/S0075435800074761.

- Koch, John (2012). The Celts: History, Life, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. pp. 687–690. ISBN 978-1598849646.

- Gaius Julius Caesar (1869). "Book VI:16". Commentaries on the Gallic War. Translated by McDevitte, W.A.; Bohn, W.S. New York, NY: Harper & Brothers.

- Davidson, Hilda Ellis (1988). Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe: Early Scandinavian and Celtic Religions. Syracuse University Press. pp. 60–61.

- Gaius Julius Caesar (1869). "Book VI:19". Commentaries on the Gallic War. Translated by McDevitte, W.A.; Bohn, W.S. New York, NY: Harper & Brothers.

- Maier, Bernhard (1997). Dictionary of Celtic Religion and Culture. Boydell & Brewer. p. 36.

- Cassius Dio. "ch 62:7". Roman History. Loeb classical Library. Translated by Cary, Earnest. University of Chicago. p. 95. Retrieved May 24, 2007 – via penelope.uchicago.edu.

- Wells, Peter S. (2001-08-05). The Barbarians Speak: How the Conquered Peoples Shaped Roman Europe. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08978-2.

- Brunaux, Jean-Louis (March–April 2001). "Gallic blood rites". Archaeology. Vol. 54. pp. 54–57.

- Brunaux, Jean-Louis (8–11 November 1990). Written at St-Riquier, FR. Les sanctuaires celtiques et leurs rapports avec le monde mediterranéean. Actes de colloque de organisés par la Direction des Antiquités de Picardie et l'UMR 126 du CNRS. Paris, FR: Éditions Errance (published 1991).

- Brunaux, Jean-Louis (2000). "La mort du guerrier celte. Essai d'histoire des mentalités". Rites et espaces en pays celte et méditerranéen. Étude comparée à partir du sanctuaire d'Acy-Romance, Ardennes, France. École française de Rome.

- Kelly, Eamonn (2013). "An Archaeological Interpretation of Irish Iron Age Bog Bodies". In Ralph, Sarah (ed.). The Archaeology of Violence. SUNY Press. pp. 232–40. ISBN 978-1438444420.

- Bentley, Diana (March–April 2015). "The Dark Secrets of the Bog Bodies". Minerva: The International Review of Ancient Art & Archaeology. Nashville, Tennessee: Clear Media: 34–37.

- Davidson, Hilda Ellis (1988). Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe: Early Scandinavian and Celtic Religions. Syracuse University Press. p. 65.

- Tice, P.; Wickliffe, H.J.T.L. (2003). History of the Waldenses: From the Earliest Period to the Present Time. Book Tree. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-58509-099-0. Retrieved 2022-10-21.

- Holmes, C. (2015). Immigrants and Minorities in British Society. Routledge Library Editions: Racism and Fascism. Taylor & Francis. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-317-38440-3. Retrieved 2022-10-21.

- Buchholz, Peter (1993). "Pagan Scandinavian religion". In Pulsiano, P. (ed.). Medieval Scandinavia: An encyclopedia. New York, NY: Routledge. pp. 521–525.

- Simek, Rudolf (2003). Religion und Mythologie der Germanen. Darmstadt, DE: Wissenshaftliche Buchgesellschaft. pp. 58–64. ISBN 3-8062-1821-8.

- Davidson, Hilda Ellis (1988). Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe: Early Scandinavian and Celtic Religions. Syracuse University Press. p. 62.

- Tacitus, Annals, I.61

- "The Origin and Deeds of the Goths". people.ucalgary.ca. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- "[no title cited]". British Archaeology magazine. Vol. 59. Britarch.ac.uk. June 2001. Archived from the original on 2011-02-13. Retrieved 2014-02-03.

- Neveux, François (2008). A brief history of the Normans: the conquests that changed the face of Europe. Robinson.

- Davidson, Hilda Ellis (1988). Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe: Early Scandinavian and Celtic Religions. Syracuse University Press. p. 59.

- Turville-Petre, E. O. G. (1975) [First published 1964]. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. Greenwood Press. pp. 253–254.

- Barford, Paul M. (2001). The Early Slavs: Culture and society in early medieval Eastern Europe. p. 120. ISBN 0801439779. Retrieved 2014-02-03.

- Talbot, Alice-Mary; Sullivan, Denis F. (2005). The History of Leo the Deacon: Byzantine Military Expansion in the Tenth Century. ISBN 9780884023241. Retrieved 2014-02-03.

- "Lavrentevskaia Letopis, also called the Povest Vremennykh Let". Polnoe Sobranie Russkikh Letopisei (PSRL). Vol. 1. col. 102.

- Larmer, Brook (2020-08-06). "Mysterious carvings and evidence of human sacrifice uncovered in ancient city". National Geographic. History. Retrieved 2020-08-07.

- Strassberg, Richard E. (2002). A Chinese Bestiary: Strange creatures from the guideways through mountains and seas. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 202.

- "Ximen Bao". Chinaculture.org. 2003-09-24. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- Qian, Sima. 秦本纪 [Annals of Qin]. guoxue.com. Records of the Grand Historian (in Chinese). Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- Han, Zhaoqi (2010). "Annals of Qin". Annotated Shiji (in Chinese). Zhonghua Book Company. pp. 415–420. ISBN 978-7-101-07272-3.

- Yellow Bird, Classic of Poetry (in Chinese)

- Burns, John F. (4 May 1986). "China hails finds at ancient tomb". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- 秦公一号大墓 [First tomb of Qin dukes] (in Chinese). Baoji city government. 2011-06-07. Archived from the original on 2014-07-14. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- Zhu, Zhongxi (2004). "On Duke Xian of Qin". Long You Wen Bo (陇右文博) (in Chinese). Gansu Provincial Museum (2). Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- Parker-Pearson, Mike (2002-08-19). "The Practice of Human Sacrifice". British Broadcasting Corporation.

- Bowe, Bruce (July 8, 2008). "Acrobats Last Tumble". Science News. Vol. 174, no. 1. Archived from the original on 2011-06-29. Retrieved 2021-09-16.

- Wilford, John Noble (2009-10-26). "Ritual Deaths at Ur were anything but serene". The New York Times.

- "Iraq's ancient past: Rediscovering Ur's royal cemetery". Almanac. Vol. 56, no. 9. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. 2009-10-27. Retrieved 2020-07-17 – via almanac.upenn.edu.

- Waddell, L. Austine (1895). Tibetan Buddhism: With its mystic cults, symbolism, and mythology, and in its relation to Indian Buddhism. p. 516.

- Grunfeld, A.T. (1996). The Making of Modern Tibet. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-56324-714-9.

- Kohn, Richard J. (2001). Lord of the Dance: The Mani Rimdu festival in Tibet and Nepal. SUNY Press. p. 120. ISBN 0791448916.

- Blue Annals (1995 ed.). p. 697.

- "Indian cult kills children for goddess". The Guardian. 5 March 2006.

- Pandey, Mahesh (2003-03-27). "Priest 'makes human sacrifice'". BBC News.

- "Dalit burnt to death; it's human sacrifice, says family! | Top Stories".

- Bhaumik, Subir (2010-04-16). "India 'human sacrifice' suspected". BBC News.

- "Body parts chopped, cooked, eaten: Human sacrifice ritual stuns Kerala". indiatoday.in. 12 October 2022.

- van Kooij, K.R.; Houben, Jan E.M. (1999). Violence denied: Violence, non-violence and the rationalization of violence in South Asian cultural history. Leiden, NL: Brill. pp. 117, 123, 129, 164, 212, 269. ISBN 90-04-11344-4.

- Bremmer, J.N. (31 December 2007). The Strange World of Human Sacrifice. Leuven: Peeters Akademik. p. 159. ISBN 978-90-429-1843-6.

- Hastings, James, ed. (2003). Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics, vol 9. Kessenger Publishing. pp. 15, 119. ISBN 0-7661-3680-9.

- Lipner, Julius (1994). Hindus: their religious beliefs and practices. New York: Routledge. pp. 185, 236. ISBN 0-415-05181-9.

- Related Articles. "luakini heiau (ancient Hawaiian religious site)". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- "Pu'ukohala Heiau & Kamehameha I". Soulwork.net. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- Mariner, William; Martin, John (1817). An Account of the Natives of the Tonga Islands in the South Pacific Ocean, with an original grammar and vocabulary of their language. Vol. 2. London, UK. p. 220.

- "Odd Faiths in Fiji Isles". The New York Times. 8 February 1891. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- "Mexican tomb reveals gruesome human sacrifice". Newscientist.com. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- Grace E. Murray, Ancient Rites and Ceremonies, p. 19, ISBN 1-85958-158-7

- Palka, Joel W. (2010). The A to Z of Ancient Mesoamerica. Scarecrow Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-1461671732.

- Benjamin, Thomas (2009). The Atlantic World: Europeans, Africans, Indians and their shared history, 1400–1900. Cambridge University Press. p. 13.

- "pre-Columbian civilizations". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Arnold, Dean E.; Bohor, Bruce F. (1975). "Attapulgite and Maya blue: An ancient mine comes to light". Archaeology. 28 (1): 23–29. cited in Haude, Mary Elizabeth (1997). "Identification and classification of colorants used during Mexico's early colonial period". The Book and Paper Group Annual. 16. ISSN 0887-8978.

- "The enigma of Aztec sacrifice". Latinamerican Studies. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- "Science and Anthropology". Cdis.missouri.edu. Archived from the original on 2010-12-19. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- Holtker, George. The Religions of Mexico and Peru. Studies in Comparative Religion. Vol. 1. CTS.

- Duverger, op. cit., pp. 174–177 "Duverger, (op. cit) 174–77"

- "New chamber confirms culture entrenched in human sacrifice". Mtintouch.net. Archived from the original on 2008-12-06. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- "Mississippian Civilization". Texasbeyondhistory.net. 2003-08-06. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- "Cahokia and the excavation of Mound 72". Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- Pauketat, Timothy R. (2004). Ancient Cahokia and the Mississippians. Cambridge University Press. pp. 88–93. ISBN 0521520665.

- "Mound 72". Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site. Archived from the original on 2012-06-23. Retrieved 2012-03-31.

- La Vere, David (2007-04-01). Looting Spiro Mounds: An American King Tut's Tomb. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 119–22. ISBN 978-0806138138.

- Koziol, Kathryn M. Violence, symbols, and the archaeological record: A case study of Cahokia's Mound 72 (Thesis). Archived from the original on 2013-07-19. Retrieved 2012-03-29.

- Pawnee ritual

- Woods, Michael (2001). Conquistadors. BBC Worldwide. p. 114. ISBN 0-563-55116-X.

- Allingham, Winnie (2 June 2003). "The mystery of Inca child sacrifice". Science & Technology. Discovery. Exn.ca. Archived from the original on May 6, 2008. Retrieved 2014-02-03.

- Bourget, Steve (2006). Sex, Death, and Sacrifice in Moche Religion and Visual Culture. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71279-9.

- Davies, Nigel (1981). Human Sacrifice. pp. 261–262.

- "The Leopard Society — Africa in the mid 1900s". Archived from the original on November 23, 2010. Retrieved April 3, 2008.

- ""Chapter 5. Ritual Cannibalism: A Case Study of Socially-Sanctioned Group Violence" in "Toward a Theory of Peace: The Role of Moral Beliefs" on Cornell University Press Digital Platform".

- Aug 05 2021 (2021-08-03). "Uganda prepares for new law on 'human sacrifice': here's what a case of 'human sacrifice' looks like | African Legal Information Institute". Africanlii.org. Retrieved 2022-08-03.

- "Where child sacrifice is a business". BBC News. 11 October 2011.

- "Nigeria's huge market of blood and human sacrifice, by Festus Adedayo - Premium Times Nigeria". 26 September 2021.

- "The Cannibal Warlords of Liberia".

- "Liberia's elections, ritual killings and cannibalism".

- Rummel, R. (1997). Death by Government. Transaction Publishers. p. 63. ISBN 1-56000-927-6.

- Williams, Clifford (1988). "Asante: Human sacrifice or capital punishment? An assessment of the period 1807–1874". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 21 (3): 433–441. doi:10.2307/219449. JSTOR 219449. — Asante is also called the Ashanti Empire.

- "The Leopard Society – Africa in the mid 1900s". Liberia Past and Present. Archived from the original on November 23, 2010. Retrieved April 3, 2008.

- "Murder by lion". Time. Archived from the original on 2009-02-07.

- Martin, Alfredo Mederos. "Sacrificios entre los Aborígenes canarios". academia.edu. 6630296.

- Brenner, Athalya (1999). Judges: A feminist companion to the Bible. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-84127-024-1.

- Berlin, Adele; Brettler, Marc Zvi (2014). Jewish study bible (2nd ed.). [s.l.]: Oxford University Press. p. 524. ISBN 978-0199978465. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- Radak, Book of Judges 11:39; Metzudas Dovid ibid

- Brenner, Athalya (1999). Judges: a feminist companion to the Bible. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-84127-024-1.

- Newsom, Carol Ann; Ringe, Sharon H.; Lapsley, Jacqueline E. Women's Bible Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 133.

- "הפולמוס העקיף בנושא העלאת קורבן אדם : בת יפתח (שופטים יא 40-29)".

- Nathan, D.; Snedeker, M. (1995). Satan's Silence: Ritual abuse and the making of a modern American witch hunt. Basic Books. p. 31. ISBN 0-87975-809-0.

- Victor, J.S. (1993). Satanic Panic: The creation of a contemporary legend. Open Court Publishing Company. pp. 207–08. ISBN 0-8126-9192-X.

- "Voices from the children of Abraham". Newman Toronto. Archived from the original on 2008-07-24. Retrieved 2021-09-17.

- McGrath, Alister E. (1997). Christian Theology: An Introduction (Second ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 390–395. ISBN 0-631-19849-0. According to Alister McGrath, early sources describing a human sacrifice include the New Testament's Letter to the Hebrews and writings by Augustine of Hippo and Athanasius of Alexandria. Later sources, besides Locke, include Thomas Chubb and Horace Bushnell.

- Benko, Stephen (1986). Pagan Rome and the Early Christians. Indiana University Press. p. 70. ISBN 0-253-20385-6.

- Snyder, Christopher Allen (2003). The Britons. Blackwell Publishing. p. 52. ISBN 0-631-22260-X.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- "Sacrifice of the Mass". Oca.org. Orthodox Church of America. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- Wesley, John. . Article XVIII – Of the Lord's Supper – via Wikisource.

- Moore, Russell D. (2009). "Baptist view: Christ's presence as memorial". In Engle, Paul E. (series ed.); Armstrong, John H. (gen. ed.) (eds.). Understanding Four Views on the Lord's Supper. Counterpoints: Church Life. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-54275-9.

- Adomnan of Iona. (1995). Sharpe, Richard (ed.). Life of St Columba. Penguin Books.

- Grunfeld, A. Tom (2015-02-24). The Making of Modern Tibet. Routledge. p. 29. ISBN 978-131745583-7.

- Epstein, Israel (1983). Tibet Transformed. Beijing: New World Press. p. 138.

- Walli, Koshelya (1974). The Conception of Ahimsa in Indian Thought. Varanasi. pp. 113–145.

- Tähtinen. Ahiṃsā: Non-violence in Indian tradition. pp. 2–5.

- Howarth, Glennys; Leaman, Oliver. Encyclopedia of Death and Dying. p. 12.

- Swami Vivekananda (2001). Walters, K.S.; Portmess, Lisa (eds.). Religious Vegetarianism. Albany, NY. pp. 50–52.

- Maharishi, Ramana. "Be as you are". Beasyouare.info. Archived from the original on 2010-04-19. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- Swami Sivananda (2005-12-11). "Bliss Divine". Dlshq.org. pp. 3–8. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- Bhaktivedanta, A.C., Swami. Religious Vegetarianism. pp. 56–60.

- Carrasco Cara Chards, María Isabel (27 April 2017). The UFO cult that murdered 19 boys because they thought they were evil. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- Rocha, Jan (5 September 2003). "Brazil occult sex killer jailed". BBC News. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- Zúñiga, Arturo (August 15, 2001). "El Niño Inmolado". Mapuche (in Spanish). Retrieved 2017-09-18.

- Carrillo, Daniel; Obreque, Rodrigo (May 23, 2010). "El Cristo mapuche se perdió en el mar". Diario Austral (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2011-04-16. Retrieved 2017-09-18.

- "El cristo mapuche se perdió en el mar". El Diario Austral de Valdivia. 23 May 2010. Archived from the original on 2011-07-07.

- Tierney, Patrick (1989). "The highest altar: Unveiling the mystery of human sacrifice". ISBN 978-0-14-013974-7.

- "CHILE: Asking for Calm". Time. 4 July 1960. Archived from the original on 17 March 2010. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- Newton, Michael (2006). The Encyclopedia of Serial Killers. New York, NY: Facts On Files. p. 446. ISBN 0-8160-6195-5.

magdalena solis encyclopedia of serial killers

- Webb, William (2013). More Scary Bitches!: 15 more of the scariest women you'll ever meet!. Absolute Crime Press.

- "Magdalena Solís: Cult leader, blood drinker, and deadly serial killer". CrimeFeed.com. Investigation Discovery. March 13, 2015. Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- "Adolfo Constanzo". Biography.com. A&E Television Network. 2 April 2014. Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- "Children "sacrificed" to Mexico's cult of "Saint Death"". The Telegraph. London, UK. March 31, 2012. Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- "Panama man pulled 2 children from clutches of killer cult".

- Lancaster, John (29 November 2003). "In India, case links mysticism, murder". Washington Post.

- McDougall, Dan (5 March 2006). "Indian cult kills children for goddess". The Observer. Khurja, India.

- Banyan (2013-08-22). "Atheism in India: He's not the son of God". Economist.com (blog). Retrieved 2014-02-03.

- McDougall, Dan (2006-03-05). "Indian cult kills children for goddess: 'Holy men' blamed for inciting dozens of deaths". The Guardian. Khurja, India. Retrieved 2014-02-03.

- "Human sacrifice? Beheaded body found near Kali temple in Birbhum". Indian Express. 2010-04-16. Retrieved 2014-02-03.

- Perry, Alex (2002-07-22). "Killing for 'mother' Kali". Time. Archived from the original on November 14, 2007. Retrieved 2014-02-03.

- Janardhanan, Arun (17 September 2019). "After human sacrifice complaint, skeletal remains found in quarry, police call granite baron today". The Indian Express. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- "Tamil Nadu to probe Madurai 'human sacrifice'". The Times of India. 16 September 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- "Human sacrifice: Skeletal remains unearthed in Madurai". India Today. 14 September 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- Murimi, Peter (2020-11-14). "The baby stealers". BBC News. Retrieved 2020-11-22.

- Paye, Jonathan (2008-01-22). "I ate children's hearts, ex-rebel says". BBC News. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- The Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic extended pursuant to resolution 2454 (2019) (6 December 2019). "Addressed to the President of the Security Council" (Letter). p. 153. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Galli, Andrea (5 September 2019). "Figli, studi, nuovi nomi: cosa fanno ora le ragazze che nel 2000 uccisero la suora in Valchiavenna". Corriere della Sera (in Italian). Retrieved 10 November 2019.