Robert FitzRoy

Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy FRS (5 July 1805 – 30 April 1865) was an English officer of the Royal Navy and a scientist. He achieved lasting fame as the captain of HMS Beagle during Charles Darwin's famous voyage, FitzRoy's second expedition to Tierra del Fuego and the Southern Cone.

Robert FitzRoy FRS | |

|---|---|

Robert FitzRoy | |

| 2nd Governor of New Zealand | |

| In office 26 December 1843 – 18 November 1845 | |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Preceded by | William Hobson |

| Succeeded by | Sir George Grey |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 5 July 1805 Ampton Hall, Ampton, Suffolk, England |

| Died | 30 April 1865 (aged 59) Upper Norwood, England |

| Cause of death | Suicide |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 5 |

FitzRoy was a pioneering meteorologist who made accurate daily weather predictions, which he called by a new name of his own invention: "forecasts".[1] In 1854 he established what would later be called the Met Office, and created systems to get weather information to sailors and fishermen for their safety.[1] He was an able surveyor and hydrographer. As Governor of New Zealand, serving from 1843 to 1845, he tried to protect the Māori from illegal land sales claimed by British settlers.[2]

Early life and career

Robert FitzRoy was born at Ampton Hall, Ampton, Suffolk, England, into the upper echelons of the British aristocracy and a tradition of public service. Through his father, General Lord Charles FitzRoy, Robert was a fourth great-grandson of Charles II of England; his paternal grandfather was Augustus Henry FitzRoy, 3rd Duke of Grafton. His mother, Lady Frances Stewart, was the daughter of the first Marquess of Londonderry and the half-sister of Viscount Castlereagh, who became Foreign Secretary. From the age of four, Robert FitzRoy lived with his family at Wakefield Lodge, their Palladian mansion in Northamptonshire.

Robert's half-brother Sir Charles FitzRoy later served as Governor of New South Wales, Governor of Prince Edward Island and Governor of Antigua.

In February 1818 at the age of 12, FitzRoy entered the Royal Naval College, Portsmouth, and in the following year he entered the Royal Navy. At the age of 14, he embarked as a voluntary student aboard the frigate HMS Owen Glendower, which sailed to South America in the middle of 1820, and returned in January 1822. He was promoted to midshipman while on the vessel, then served as such on HMS Hind.

He completed his course with distinction and was promoted lieutenant on 7 September 1824, having passed the examination with 'full numbers' (100%), the first to achieve this result. After serving on HMS Thetis, in 1828 he was appointed flag lieutenant to Rear-Admiral Sir Robert Waller Otway, commander-in-chief of the South American station, aboard HMS Ganges.

At that time Beagle, under Captain Pringle Stokes, was carrying out a hydrographic survey of Tierra del Fuego, under the overall command of Captain Phillip Parker King in HMS Adventure. Pringle Stokes became severely depressed and fatally shot himself. Under Lieutenant Skyring, the ship sailed to Rio de Janeiro, where Otway appointed FitzRoy as (temporary) captain of the Beagle on 15 December 1828. By the ship's return to England on 14 October 1830, FitzRoy had established his reputation as a surveyor and commander.

During the survey, some of his men were camping onshore when a group of Fuegian natives made off with their boat. His ship gave chase and, after a scuffle, the culprits' families were brought on board as hostages. Eventually FitzRoy held two boys, a girl and two men (one man escaped.) As it was not possible to put them ashore conveniently, he decided to "civilise the savages", teaching them "English ... the plainer truths of Christianity ... and the use of common tools" before returning them as missionaries.[3]

The sailors gave them names: the girl was called Fuegia Basket (so named because the replacement for the stolen boat was an improvised coracle that resembled a basket), the younger boy Jemmy Button (FitzRoy allegedly 'purchased' him with a large pearl button), the man York Minster (after the large rock so-named near which he was captured). The second, elder, boy he named Boat Memory. FitzRoy brought the four back with the ship to England. Boat Memory died following a smallpox vaccination. The others were cared for and taught by the trainee missionary Richard Matthews; they were considered civilised enough to be presented at Court to King William IV and Queen Adelaide in the summer of 1831.

HMS Beagle's second voyage

In early May 1831 FitzRoy stood as Tory candidate for Ipswich in the General Election, but was defeated. His hopes of obtaining a new posting and organising a missionary project to Tierra del Fuego appeared to be failing. He was arranging for the charter of a ship at his own expense to return the Fuegians with Matthews when his friend Francis Beaufort, Hydrographer to the British Admiralty, and his "kind uncle", the Duke of Grafton, interceded on his behalf at the Admiralty. On 25 June 1831 FitzRoy was re-appointed commander of the Beagle. He spared no expense in fitting out the ship.

He was conscious of the stressful loneliness of command. He knew of the suicides both of Captain Stokes and of his uncle Viscount Castlereagh, who had cut his own throat in 1822 while in government office. FitzRoy talked to Beaufort in August 1831, asking him to find a suitable gentleman companion for the voyage. Such a companion should share his scientific tastes, make good use of the expedition's opportunities for researching natural history, dine with him as an equal, and provide a semblance of normal human friendship.[4] While those Beaufort first approached (including Professor J. S. Henslow of the University of Cambridge) turned the opportunity down, FitzRoy eventually approved Charles Darwin for the position. Before they left England, FitzRoy gave Darwin a copy of the first volume of Charles Lyell's Principles of Geology, a book the captain had read that explained terrestrial features as the outcome of a gradual process taking place over extremely long periods. FitzRoy took a request from Lyell to record observations on geological features, such as erratic boulders.[5]

FitzRoy and Darwin got on well together, but there were inevitable strains during the five-year survey voyage. The captain had a violent temper, his outbursts had gained him the nickname "Hot Coffee",[6] which resulted in quarrels sometimes "bordering on insanity", as Darwin later recalled. On a memorable occasion in March 1832 at Bahia, Brazil, Darwin was horrified at tales of the treatment of slaves. FitzRoy, while not endorsing brutality, recounted how an estancia owner once asked his slaves if they wished to be free and was told they did not. Darwin asked FitzRoy if he thought slaves could answer such a question honestly when it was posed by their master, at which the captain lost his temper and, before storming out, told Darwin that if he doubted his word they could no longer live together; effectively he banished Darwin from his table. Before nightfall FitzRoy's temper cooled and he sent an apology, with the request that Darwin "continue to live with him." They avoided the subject of slavery from that time on. None of their quarrels were over religious or doctrinal issues; such disagreements came after the voyage.[4]

At the island of "Buttons Land" in Tierra del Fuego they set up a mission post, but when they returned nine days later, the possessions had been looted. Matthews gave up, rejoining the ship. He left the three "westernised" Fuegians to continue the missionary work.

While in the Falkland Islands, FitzRoy bought a schooner out of his own funds to assist with the surveying tasks he had been asked to complete. He had it refitted and renamed Adventure, hoping that the cost would be reimbursed by the Admiralty. They returned to the mission post but found only Jemmy Button. He had returned to native ways and refused the offer to go with them back to England.

At Valparaiso in 1834, while Darwin was away from the ship exploring the Andes, the Admiralty reprimanded FitzRoy for buying the Adventure. He took the criticism badly, selling the schooner and announcing they would go back to recheck his survey, then resigning his command with doubts about his sanity. The ship's officers persuaded him to withdraw his resignation and continue as planned once Darwin returned to the ship.[6] FitzRoy continued his voyage, sailing on to the Galapagos, Tahiti, New Zealand, Australia and South Africa. He detoured to Bahia in Brazil on the return voyage so that he could carry out an additional check, to ensure the accuracy of his longitude measurements before returning to England.

Return from the voyage

Soon after the Beagle's return on 2 October 1836, FitzRoy married Mary Henrietta O'Brien, a young woman to whom he had long been engaged. Darwin was amazed, as not once during the entire five years of the trip had FitzRoy spoken about being engaged.

FitzRoy was awarded a gold medal by the Royal Geographical Society in 1837. Extracts from his diary read to the society on 8 May 1837 included the observation:

- Is it not extraordinary, that sea-worn, rolled, shingle-stones, and alluvial accumulations, compose the greater portion of these plains? How vast, and of what immense duration, must have been the actions of these waters which smoothed the shingle-stones now buried in the deserts of Patagonia!"[7]

FitzRoy wrote his account of the voyage, including editing the notes of the previous captain of the Beagle. It was published in May 1839 as the Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of H.M.S. Adventure and Beagle, in four volumes, including Darwin's Journal and Remarks, 1832–1836 as the third volume. FitzRoy's account includes a section of Remarks with reference to the Deluge in which he admits that, having read works "by geologists who contradict, by implication, if not in plain terms, the authenticity of the Scriptures" and "while led away by sceptical ideas," he had remarked to a friend that the vast plain of sedimentary material they were crossing "could never have been effected by a forty days' flood." He wrote that in his "turn of mind and ignorance of scripture," he was willing to disbelieve the Biblical account. Concerned that such ideas might "reach the eyes of young sailors," he explains in detail his renewed commitment to a literal reading of the Bible, with arguments that rock layers high in the mountains containing sea shells are proof of Noah's Flood and that the six days of creation could not have extended over aeons because the grass, herbs and trees would have died out during the long nights.[8][9]

R.D. Keynes, in his introduction to the 2001 edition of Darwin's diary, suggests that FitzRoy had undergone a religious conversion.[9] He was dissociating himself from the new ideas of Charles Lyell, which he had accepted during the voyage, and from Darwin's account which embraced these ideas. Under the influence of his very religious wife, he asserted a new commitment to the doctrine of the established Church of England.[6]

In 1841 FitzRoy was elected the Tory Member of Parliament for Durham. He was appointed Acting Conservator of the River Mersey in 1842.

Governor of New Zealand

The first Governor of New Zealand, Captain William Hobson, R.N., died in late 1842. The Church Missionary Society, which had a strong New Zealand presence, suggested FitzRoy as his successor and he was appointed by the government. He took up his new task in December 1843. On the journey to New Zealand, he met William John Warburton Hamilton and made him his private secretary.[10]

His instructions were to maintain order and protect the Māori, while satisfying the land hunger of the settlers pouring into the country. He was given very few military resources. Government revenue, mainly from customs duties, was woefully inadequate for his responsibilities.

One of his first tasks was to enquire into the circumstances surrounding the Wairau Affray, in which there had been violent conflict between settlers and the Maori. He found the actions of the colonists to have been illegal and declined to take any action against Te Rauparaha. He did not have the troops to meet him on anything like equal terms. But the New Zealand Company and the settlers felt betrayed and angry. He appointed a Government Superintendent for the area, to establish a ruling presence. Fitzroy also insisted that the New Zealand Company pay the Māori a realistic price for the land they claimed to have purchased. These moves made him very unpopular.

Land sales were a continuing vexatious issue. The settlers were eager to buy land and some Māori were willing to sell, but under the provisions of the Treaty of Waitangi, land sales required the Government as an intermediary, and were thus extremely slow. FitzRoy changed the rules to allow settlers to purchase Māori land directly, subject to a duty of ten shillings per acre. But land sales proved slower than expected.

To meet the financial shortfall, FitzRoy raised the customs duties, then replaced them with property and income taxes. All these expedients failed. Before long the Colony was faced with bankruptcy, and FitzRoy was forced to begin issuing promissory notes, paper money without backing.

Meanwhile, the Māori in the far North, around the Bay of Islands, who had been the first to sign the Treaty of Waitangi, were feeling increasingly sidelined and resentful of the changes that had taken place in New Zealand. To signal their resentment, Hone Heke cut down the flagpole at Kororareka. Rather than address the problems, FitzRoy had the flagpole re-erected. Hone Heke cut it down again, four times altogether; by the fourth occasion the First New Zealand War, sometimes called the Flagstaff War or the Northern War, was well under way.

FitzRoy quickly realized that he did not have the resources to bring about a quick end to the war. Meanwhile, the spokesmen for the New Zealand Company were active back in the United Kingdom, lobbying against FitzRoy's Governorship, which they presented to the House of Commons in a very poor light. As a result, he was shortly afterwards recalled and replaced by George Grey, then Governor of South Australia. Grey was given the backing and financial support that FitzRoy had needed but was denied.

Later life and impact on meteorology

FitzRoy returned to Britain in September 1848 and was made superintendent of the Royal Naval Dockyards at Woolwich. In March 1849 he was given his final sea command, the screw frigate HMS Arrogant.[11]

In 1850, FitzRoy retired from active service, partly due to ill health. The following year, in 1851, he was elected to the Royal Society with the support of 13 fellows, including Charles Darwin.[12]

In 1854, on the recommendation of the President of the Royal Society, FitzRoy was appointed as chief of a new department to deal with the collection of weather data at sea. His title was Meteorological Statist to the Board of Trade, and he had a staff of three. This was the forerunner of the modern Meteorological Office. He arranged for captains of ships to provide information, with tested instruments being loaned for this purpose, and for computation of the data collected.[13]

FitzRoy soon began to work on strategies to make weather information more widely available for the safety of shipping and fishermen. He directed the design and distribution of a type of barometer which, on his recommendation, was fixed at every port to be available to crews for consultation before setting out to sea. Stone housings for such barometers are still visible at many fishing harbours.[14] The invention of several different types of barometers was attributed to him. These became popular and continued in production into the 20th century, characteristically engraved with Admiral FitzRoy's special remarks on interpretation, such as: "When rising: In winter the rise of the barometer presages frost."[15]

A storm in 1859 that caused the loss of the Royal Charter inspired FitzRoy to develop charts to allow predictions to be made in which he coined the term "weather forecast".[13] Fifteen land stations were established to use the new telegraph to transmit to him daily reports of weather at set times. The first daily weather forecasts were published in The Times in 1861.[1] The 1859 storm resulted in the Crown distributing storm glasses, then known as "FitzRoy's storm barometers", to many small fishing communities around the British Isles.[16]

In 1860, FitzRoy introduced a system of hoisting storm warning cones at the principal ports when a gale was expected. He ordered fleets to stay in port under these conditions.[17] The Weather Book, which he published in 1863, was far in advance of the scientific opinion of the time.[18] Queen Victoria once sent messengers to FitzRoy's home requesting a weather forecast for a crossing she was about to make to the Isle of Wight.[1]

Many fishing fleet owners objected to the posting of gale warnings, which required that fleets not leave the ports. Under this pressure, FitzRoy's system was abandoned for a short time after his death. The fishing fleet owners reckoned without the pressure of the fishermen, for whom FitzRoy had been a hero responsible for saving many lives. The system was eventually reinstated in simplified form in 1874.[17]

When The Origin of Species was published FitzRoy was dismayed and apparently felt guilty for his part in the theory's development. He was in Oxford on 30 June 1860 to present a paper on storms and attended the meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science at which Samuel Wilberforce attacked Darwin's theory. During the debate FitzRoy, seen as "a grey haired Roman nosed elderly gentleman", stood in the centre of the audience and "lifting an immense Bible first with both and afterwards with one hand over his head, solemnly implored the audience to believe God rather than man". As he admitted that The Origin of Species had given him "acutest pain", the crowd shouted him down.[19]

FitzRoy debunked Lieutenant Stephen Martin Saxby's lunar weather forecasting method as pseudoscience. Saxby tried to counter FitzRoy's arguments in the second edition of his book Saxby Weather System (1864).[20]

Death and legacy

FitzRoy had been promoted to rear-admiral on the reserved list in 1857[21] and was advanced to vice-admiral in 1863.[22] In the coming years, internal and external troubles at the Meteorological Office, financial concerns as well as failing health, and his struggle with depression took their toll.[23] On 30 April 1865, Vice-Admiral FitzRoy died by suicide[24] by cutting his throat with a razor.[25] FitzRoy died having exhausted his entire fortune (£6,000, the equivalent of £400,000 today) on public expenditure.

When this came to light, in order to prevent his wife and daughter living in destitution, his friend and colleague Bartholomew Sulivan began an Admiral FitzRoy Testimonial Fund, which succeeded in getting the government to pay back £3,000 of this sum.[26] (Charles Darwin contributed £100).[27] Queen Victoria gave the special favour of allowing his widow and daughter the use of grace and favour apartments at Hampton Court Palace.[28]

FitzRoy is buried in the front churchyard of All Saints' Church in Upper Norwood, south London. His memorial was restored by the Meteorological Office in 1981.

FitzRoy's publications arising from the expedition were a major reference point for 19th-century Chilean explorers of western Patagonia. FitzRoy's book Sailing Directions for South America led Chilean Navy hydrographer Francisco Hudson to investigate in the 1850s the possible existence of a sailing route through internal waters from the Chiloé Archipelago to the Straits of Magellan.[29] Enrique Simpson found instead FitzRoy's mapping of little use, noting in 1870 that "Fitzroy's chart, that is quite exact until that point [Melinka 43° 53' S], is worthless further ahead...". Thus south of Melinka, Simpson relied more in the late 18th-century sketches of José de Moraleda y Montero.[30] Simpson's contemporary Francisco Vidal Gormaz was critical of the overall work of FitzRoy and Darwin, stating that they had failed to acknowledge the importance of the Patagonian islands.[31]

Personal life

Robert FitzRoy was married twice. In 1836 he married Mary Henrietta, daughter of Major-General Edward James O'Brien.[32] They had four children: Emily-Unah, Fanny, Katherine and Robert O'Brien. In 1854, after the death of his first wife, he married in London Maria Isabella, daughter of John Henry Smyth, of Heath Hall, Heath, West Yorkshire (son of the politician John Smyth), who had married his first cousin- both being grandchildren of the 3rd Duke of Grafton, as was Robert FitzRoy- Lady Elizabeth Anne FitzRoy. Lady Elizabeth was daughter of the 4th Duke of Grafton and was a first cousin of Robert FitzRoy; Robert's new wife was therefore his first cousin once removed. They had one daughter, Laura Maria Elizabeth (1858-1943).[33]

Memorials

A neighbourhood in the city of Punta Arenas Chile, was named in his honour in 1964.

A memorial to FitzRoy is erected atop a metamorphic outcrop beside the Bahia Wulaia dome middens on Isla Navarino, in the Chilean part of Tierra del Fuego archipelago, South America.[35][36] It was presented in his bicentenary (2005) and commemorates his 23 January 1833 landing on Wulaia Cove. Another memorial, presented also in FitzRoy's bicentenary, commemorates his Cape Horn landing on 19 April 1830.[35]

Mount Fitz Roy (Argentina–Chile, at the extreme south of the continent), was named after him by the Argentine scientist and explorer Francisco Moreno. It is 3,440 m (11,286 ft) high. The aboriginals had not named it, and used the word chaltén (meaning smoking mountain) for this and other peaks. Fitzroy River, in northern Western Australia, was named after him by Lieutenant John Lort Stokes who, at the time, commanded HMS Beagle (previously commanded by FitzRoy). The South American conifer Fitzroya cupressoides is named after him, as well as the Delphinus fitzroyi, a species of dolphin discovered by Darwin during his voyage aboard the Beagle.[37] Fitzroy, Falkland Islands and Port Fitzroy, New Zealand are also named after him.

The World War II Captain class frigate HMS Fitzroy (K553) was named after him, as was the weather ship Admiral Fitzroy (formerly HMS Amberley Castle). In 2010 New Zealand's National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) named its new IBM supercomputer "FitzRoy" in honour of him.[38]

On 4 February 2002, when the shipping forecast sea area Finisterre was renamed to avoid confusion with the (smaller) French and Spanish forecast area of the same name, the new name chosen by the UK's Meteorological Office was "FitzRoy", in honour of their founder.

FitzRoy has been commemorated by the Fitzroy Building at the University of Plymouth, used by the School of Earth, Ocean and Environmental Science.

There is blue plaque on FitzRoy's house at 38 Onslow Square, London.[39]

Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy was commemorated on two stamps issued by the Royal Mail for the Falkland Islands and St Helena.

Fitzroy Island in Queensland, Australia, is named after FitzRoy,[40] as are the Fitzroy River and subsequently Fitzroy Crossing in Western Australia.

In fiction

The BBC made a BAFTA award-winning television series in 1978 titled The Voyage of Charles Darwin where Captain Robert Fitzroy was played by actor Andrew Burt with Malcolm Stoddard as Darwin with a storyline that followed the historic interaction between Darwin and FitzRoy before and after their time together on HMS Beagle. [41]

In 1997, the play FitzRoy by Juliet Aykroyd was first performed at the University of Reading.[42] It has since been performed under the title The Ostrich and the Dolphin[43] – alluding to Darwin's rhea and the dusky dolphin, named Delphinus fitzroyi by Darwin – before being published as Darwin & FitzRoy in October 2013.[44]

A novel by Argentinian writer, Sylvia Iparraguirre, entitled Tierra del Fuego, was published in 2000.[45] It retells the story of Fitzroy's experiment with "civilizing" the Yamaná from the perspective of a fictional narrator, British-Argentinian Jack Guevarra. The novel received the Sor Juana de la Cruz prize and was translated into English by Hardie St. Martin.[46]

A novel entitled This Thing of Darkness by Harry Thompson was published in 2005 (it was published in the U.S. in 2006 under the title To the Edge of the World). The novel's plot followed the lives of FitzRoy, Darwin and others connected with the Beagle expeditions, following them between the years of 1828 and 1865. It was a nominee on the long list for the 2005 Man Booker Prize[47] (although Thompson died in November 2005).

The novel Darwin's Dreams by Sean Hoade was published in 2008 and republished in a new edition in 2016. The novel begins with the first meeting of Darwin and FitzRoy and ends with Darwin receiving notice of FitzRoy's suicide. The plot is interlaced with fictional "dreams" that imagine how the world would be if the ideas of evolutionary thinkers over the millennia had been literally true. The dreams also show how Darwin's subconscious dealt with major themes in his life such as the death of his beloved daughter Annie and his lifelong friendship and rivalry with FitzRoy.[48]

The play Darwins Kapten was published by Henning Mankell in 2009, and had its world premiere in 2010 at the Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm. It is about Darwin and his journey on the Beagle: many years after the five-year long voyage, Darwin receives a message that his captain on the ship, FitzRoy, has committed suicide. The play portrays the reception of Darwin's discoveries, as well as the consequences of taking a stand against existing ideas in a world that is built on belief in God as the only creator of life.[49]

See also

- European and American voyages of scientific exploration

- Second voyage of HMS Beagle

- HMS Beagle

- The Voyage of the Beagle

References

- Citations

- Moore, Peter (30 April 2015). "The birth of the weather forecast". BBC News. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- "Robert FitzRoy biography". New Zealand history (NZ Govt website).

- Adam Kuper (2017). The Reinvention of Primitive Society: Transformations of a Myth. London: Taylor & Francis. p. 26.

- Browne, Janet (7 August 2003). Charles Darwin: Voyaging. Pimlico. ISBN 1-84413-314-1.

- Introduction by Janet Browne and Michael Neve to – Darwin, Charles (1989). Voyage of the Beagle. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-043268-X.

- Desmond, Adrian; Moore, James (1991). Darwin. London: Michael Joseph, Penguin Group. ISBN 0-7181-3430-3.

- FitzRoy, R. (1837). "Extracts from the Diary of an Attempt to Ascend the River Santa Cruz, in Patagonia, with the boats of his Majesty's sloop Beagle". Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London. 7: 114–26. doi:10.2307/1797517. JSTOR 1797517.

- FitzRoy, Robert (1839). "Chapter XXVIII: A Very Few Remarks with Reference to the Deluge". Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of His Majesty's Ships Adventure and Beagle between the years 1826 and 1836, describing their examination of the southern shores of South America, and the Beagle's circumnavigation of the globe. Proceedings of the second expedition, 1831–36, under the command of Captain Robert Fitz-Roy, R.N. London: Henry Colburn.

- Keynes, R. D., ed. (2001). Charles Darwin's Beagle Diary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. xxi–xxii.

- Scholefield 1940, p. 349.

- Agnew, Duncan Carr (January 2004). "Robert Fitzroy and the Myth of the 'Marsden Square': Transatlantic Rivalries in Early Marine Meteorology". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. London, UK: The Royal Society. 58 (1): 26. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2003.0223. JSTOR 4142031. S2CID 145354564.

- "List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660–2007" (PDF). The Royal Society Library and Information Services. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- Mellersh, H. E. L. (1968). FitzRoy of the Beagle. Hart-Davis. ISBN 0-246-97452-4.

- "Scottish Harbour Barometers". Banffshire Maritime & Heritage Association. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- "Admiral FitzRoy's special remarks". Queenswood.com. Archived from the original on 5 July 2007.

- "Storm Glass". The Weather Notebook. Mount Washington Observatory. 7 May 2004. Archived from the original on 20 January 2015.

- Kington, John (1997). Hulme, Mike; Barrow, Elaine (eds.). Climates of the British Isles: Present, Past and Future. Routledge. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-41513-016-5.

- "The Royal Charter Gale and the world's first National Forecasting Service". Met Office website.

- Desmond, Adrian J.; Moore, James R. (1991). Darwin. London: Michael Joseph. p. 495. ISBN 0-7181-3430-3. OCLC 26502431.

- Saxby, S. M. (1864). Saxby Weather System.

- "No. 21968". The London Gazette. 17 February 1857. p. 539.

- "No. 22772". The London Gazette. 18 September 1863. p. 4561.

- Gribbin, John & Mary (2003). FitzRoy. Review. ISBN 0-7553-1181-7

- "Robert Fitzroy". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- Browne, E. Janet (2002). Charles Darwin: The Power of Place. Vol. 2. Princeton University Press. p. 264. ISBN 0-691-11439-0.

- Darwin, Charles (19 December 2002). The Correspondence of Charles Darwin:, Volume 13; Volume 1865, page 259. ISBN 9780521824132.

- "Letter no. 4908 – Charles Shaw to Charles Darwin". Darwin Correspondence Project. 3 October 1865. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- Taylor, James (17 May 2016). 'The Voyage of the Beagle' by James Taylor, page 182. ISBN 9781844863273.

- Sepúlveda Ortíz, Jorge (1998), "Francisco Hudson, un destacado marino poco conocido en nuestra historia" (PDF), Revista de Marina (in Spanish): 1–20

- Simpson, E. (1874). Esploraciones hechas por la Corbeta Chacabuco al mando del capitán de fragata don Enrique M. Simpson en los Archipiélagos de Guaitecas, Chonos i Taitao. Santiago. Imprenta Nacional.

- Núñez, Andrés G.; Molina O., Raúl; Aliste A., Enrique; Bello A., Álvaro (2016). "Silencios geográficos de Patagonia-Aysén: Territorio, nomadismo y perspectivas para re-pensar los margenes de la nación en el siglo XIX" [Geographical silences in Patagonia-Aysén: Territory, nomadism and perspectives for re-thinking the margins of Chile in the nineteenth century]. Magallania (in Spanish). 44 (2): 107–130. doi:10.4067/S0718-22442016000200006.

- Burke's Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage, 107th edition, vol. 2, ed. Charles Mosley, Burke's Peerage Ltd, 2003, p. 1617

- Burke's Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage, 107th edition, vol. 2, ed. Charles Mosley, Burke's Peerage Ltd, 2003, p. 1617

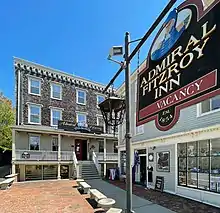

- "About the Inn". Admiral Fitzroy Inn. Admiral Fitzroy Inn. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- "Homenaje a un navegante singular" (in Spanish). Patrimonio Cultural De Chile. Archived from the original on 2 July 2007. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- Hogan, C. Michael (2008). "Bahia Wulaia Dome Middens". Megalithic Portal.

- Bryson, Bill (2005). A Short History of Nearly Everything. London: Transworld. p. 481.

- "NIWA Installs new IBM supercomputer". Geekzone. 21 July 2010.

- "FitzRoy, Admiral Robert (1805-1865)". English Heritage. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- "Robert Fitzroy takes his own life". HMS Beagle Project. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- "The Voyage of Charles Darwin". IMDb.com. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- Aykroyd, Juliet (8 October 2013). Darwin & FitzRoy. Sulivan & Stokes. Retrieved 23 March 2017 – via Amazon.

- "The Ostrich and the Dolphin (play)". UK Theatre Web. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- "Authors: Juliet Aykroyd". Stay Thirsty Media. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- "Tierra del Fuego". Northwestern University Press. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- "Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Literature Award - 1999 - Sylvia Iparraguirre". Guadalajara International Book Fair. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

Tierra del Fuego is the novel with which the Argentinean Sylvia Iparraguirre won the 1999 Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Prize for a novel written by women, awarded by the Guadalajara International Book Fair.

- "This Thing of Darkness". Man Booker Prize. 2005. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- Hoade, Sean. "Darwin's Dreams". Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- Mankell, Henning. "Darwin's Captain". henningmankell.com. Archived from the original on 22 February 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- Bibliography

- Narrative of the surveying voyages of His Majesty's Ships Adventure and Beagle between the years 1826 and 1836, describing their examination of the southern shores of South America, and the Beagle's circumnavigation of the globe.

- King, P. P. (1839). FitzRoy, Robert (ed.). Narrative of the surveying voyages of His Majesty's Ships Adventure and Beagle between the years 1826 and 1836, describing their examination of the southern shores of South America, and the Beagle's circumnavigation of the globe. Proceedings of the first expedition, 1826–30, under the command of Captain P. Parker King, R.N., F.R.S. Vol. I. London: Henry Colburn. Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- FitzRoy, Robert (1839). Narrative of the surveying voyages of His Majesty's Ships Adventure and Beagle between the years 1826 and 1836, describing their examination of the southern shores of South America, and the Beagle's circumnavigation of the globe. Proceedings of the second expedition, 1831–36, under the command of Captain Robert Fitz-Roy, R.N. Vol. II. London: Henry Colburn. Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- FitzRoy, Robert (1839). Narrative of the surveying voyages of His Majesty's Ships Adventure and Beagle between the years 1826 and 1836, describing their examination of the southern shores of South America, and the Beagle's circumnavigation of the globe. Vol. Appendix to Volume II. London: Henry Colburn. Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- FitzRoy, Robert (1846). Remarks on New Zealand. London: W. And H. White.

- FitzRoy, Robert (1859). Notes on Meteorology. Board of Trade.

- FitzRoy, Robert (1860). Barometer Manual. Board of Trade.

- FitzRoy, Robert (1863). The Weather Book: A Manual of Practical Meteorology. London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, & Green.

- Collins, Philip R. (2007). FitzRoy and his barometers. Baros Books. ISBN 978-0-948382-14-7.

- Gribbin, John & Gribbin, Mary (2003). FitzRoy: The Remarkable Story of Darwin's Captain and the Invention of the Weather Forecast. Review. ISBN 0-7553-1182-5.

- Marks, Richard Lee (1991). Three Men of The Beagle. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-394-58818-5.

- Mellersh, H. E. L. (1968). FitzRoy of the Beagle. Hart-Davis. ISBN 0-246-97452-4.

- Moon, Paul (2000). FitzRoy: Governor in Crisis 1843–1845. David Ling Publishing. ISBN 0-908990-70-7.

- Nichols, Peter (2003). Evolution's Captain: The Dark Fate of the Man Who Sailed Charles Darwin Around the World. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-008877-X.

- Scholefield, Guy Hardy, ed. (1940). A Dictionary of New Zealand Biography : A–L (PDF). Vol. I. Wellington: Department of Internal Affairs. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- Taylor, James (2008). The Voyage of the Beagle: Darwin's extraordinary adventure aboard FitzRoy's famous survey ship. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-920-0.

- Thompson, Harry (2005). This Thing of Darkness. Headline Review. ISBN 0-7553-0281-8.

External links

- O'Byrne, William Richard (1849). . . John Murray – via Wikisource.

Works by or about Robert Fitzroy at Wikisource

Works by or about Robert Fitzroy at Wikisource- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Robert FitzRoy

- Science Museum | Heavy Weather | Admiral FitzRoy and the FitzRoy barometer

- BBC – h2g2 – Robert FitzRoy

- Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

- Government House, Wellington biography

- Image of Robert FitzRoy's commemorative plaque in Horn Island (Chile)

- Image of Robert FitzRoy's memorial at Wulaia Bay (Chile)

- Works by Robert FitzRoy at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Robert FitzRoy at Internet Archive

- The Weather Book

- Robert FitzRoy FRS: sailing into the storm – an audio lecture by Dr John Gribbin at Royal Society website

- BBC News Magazine – The birth of the weather forecast